Abstract

Introduction

Patients with sigmoid volvulus (SV) are at a high risk of recurrence with increased morbidity and mortality. This study aims to review whether patients with SV underwent definitive surgical treatment after initial endoscopic reduction according to the guidelines, and to compare mortality rate between surgical and conservative management.

Methods

Retrospective study conducted at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, included all patients with SV between 2016 and 2018. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality following the initial management of the acute attack. Secondary outcomes were recurrence rate and overall mortality. The median follow-up period was 3 years.

Results

A total of 40 patients were identified with a median age of 82 years; 27 (67%) were males. Of these 40 patients, 6 (15%) had emergency surgery, 26 (65%) received endoscopic decompression only, and 8 (20%) had planned definitive resection; 32 patients (80%) had recurrence and the median interval between any two episodes was 86 days. The mortality rate among patients with ASA grade 3 or 4 in the three groups, elective surgery, emergency surgery and decompression only, was 0%, 25% and 70% respectively, whereas it was 0%, 50% and 33% in those with ASA grade 2. The mortality rate among patients with similar ASA who had a planned surgery was significantly lower compared with those who did not undergo surgery (p=0.003).

Conclusions

In patients with sigmoid volvulus, regardless of ASA grade, performing early definitive surgery following initial endoscopic decompression resulted in a statistically significant lower mortality rate.

Keywords: Sigmoid volvulus, Interstinal obstruction, Large bowel obstruction

Introduction

Intestinal volvulus is one of the common causes of bowel obstruction. Sigmoid volvulus (SV) is the most common cause of strangulation of the colon and is the third most common cause of large bowel obstruction after cancer and diverticular disease.1 The incidence of SV varies among different regions. In the UK, it is responsible for approximately 2–3% of all cases of intestinal obstruction, and about 5–10% of colonic obstruction.1 SV has a high recurrence rate of about 80% and a significant mortality rate reaching up to 25–50% in some case series.2

The classical SV patient is an elderly institutionalised male patient, on psychotropic medications with a previous history of recurrent volvulus. The male-to-female ratio is 2:1, and median age of presentation is 80 years old.1 Other risk factors include chronic constipation, permissive use of laxatives and weak support of sigmoid colon either congenitally or acquired due to previous colon mobilisation. It is rare in children but can happen in patients with Hirschsprung’s or Chagas disease.1

According to the rapidity and degree of twisting of the sigmoid colon mesentery, SV can be classified into three categories: subacute, acute and fulminating. The most common type is the subacute volvulus, which occurs in elderly patients with a history of previous attacks of SV or chronic constipation. This type often runs a benign course. Ischaemic complications can still take place, but over a relatively longer time. The acute type is characterised by a sudden onset and rapidly progressive course. This type is more common in relatively younger patients on first occasion and they usually present with classical features of intestinal obstruction. It can quickly progress to the fulminating type when patients present with signs of peritonitis and shock secondary to mesenteric ischaemia and bowel wall perforation.3

The anatomical prerequisites for SV are long redundant sigmoid with a narrow mesentery that allow twisting of the sigmoid colon around its vascular access. Rotation of distended colon occurs usually in anticlockwise pattern leading to vascular impingement. Movement of the dilated bowel is hindered by the abdominal wall and retroperitoneum. Chronic adhesions and inflammation due to previous episodes of torsion and detorsion lead to shortening of the mesocolon. These factors will lead to entrapment of the twisted sigmoid colon, failure of decompression and progressive strangulation secondary to closed-loop obstruction.4

Plain x-ray is diagnostic in 57–90% of patients, with the classic coffee bean sign detected in about 60% of cases. Computed tomography (CT) scan has a very high accuracy for diagnosis of SV, approaching 100%. Other imaging modalities, such as barium enema, are less commonly used nowadays.5

According to the current practice guidelines, patients who present with uncomplicated SV are initially managed by endoscopic decompression either with rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy, with insertion of a rectal tube for 24–48h in order to maintain reduction and lessen the risk of early recurrence.1 Following initial conservative management, patients should be assessed for definitive surgery, ideally during the index admission after medical optimisation to avoid the high risk of recurrence and increased morbidity and mortality with each attack. Patients who present with peritonitis and sepsis should be managed surgically, usually with Hartmann’s procedure.1,6

Our study aims to assess the current practice at East Kent hospitals in relation to the published guidelines and to determine the outcome of surgical and nonsurgical management of SV, including rate of recurrence and mortality.

Methods

The records of all patients admitted with an acute presentation of SV to one of the two acute sites of East Kent University hospitals NHS Foundation Trust between April 2016 and October 2018 were reviewed retrospectively. Patients were identified through admissions office records, electronic discharge summaries, the operating theatre register, endoscopy reports and outpatient letters.

Data collection included age, gender, comorbidities, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, clinical presentation, nonoperative vs operative interventions, mortality and number of recurrences.

The diagnosis was confirmed by clinical, radiological (abdominal x-ray or CT), endoscopic or operative findings. Initial management in the emergency setting was decompression with either rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy unless emergency Hartmann’s procedure was indicated for either ischaemia or perforation. Following successful decompression, this was either the only treatment or was followed by a planned resection.

The index admission was defined as the first admission with SV in the period between April 2016 and October 2018, whereas recurrence was defined as any further readmission with SV afterwards.

The primary outcome of the study was 30-day mortality following the initial management of the acute attack. Secondary outcomes included recurrence rate and overall mortality until September 2020. The average follow-up period was 3 years.

Results

A total of 40 patients were treated for acute SV during the 2.5-year period between 2016 and 2018. Of these patients, 27 were male and 13 were female, with a median age of 82 years; 14 patients had ASA grade 2, whereas 26 had ASA grade 3 or 4 and 19 patients (47.5%) were known to have neurological or psychiatric disorders (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Patient demographics

| Total=40 patients | |

| Age | |

| Median 82 years (37–99) | |

| Gender | |

| Male:female=2:1.1 | |

| ASA grade | |

| ASA 2 | 14 |

| ASA 3/4 | 26 |

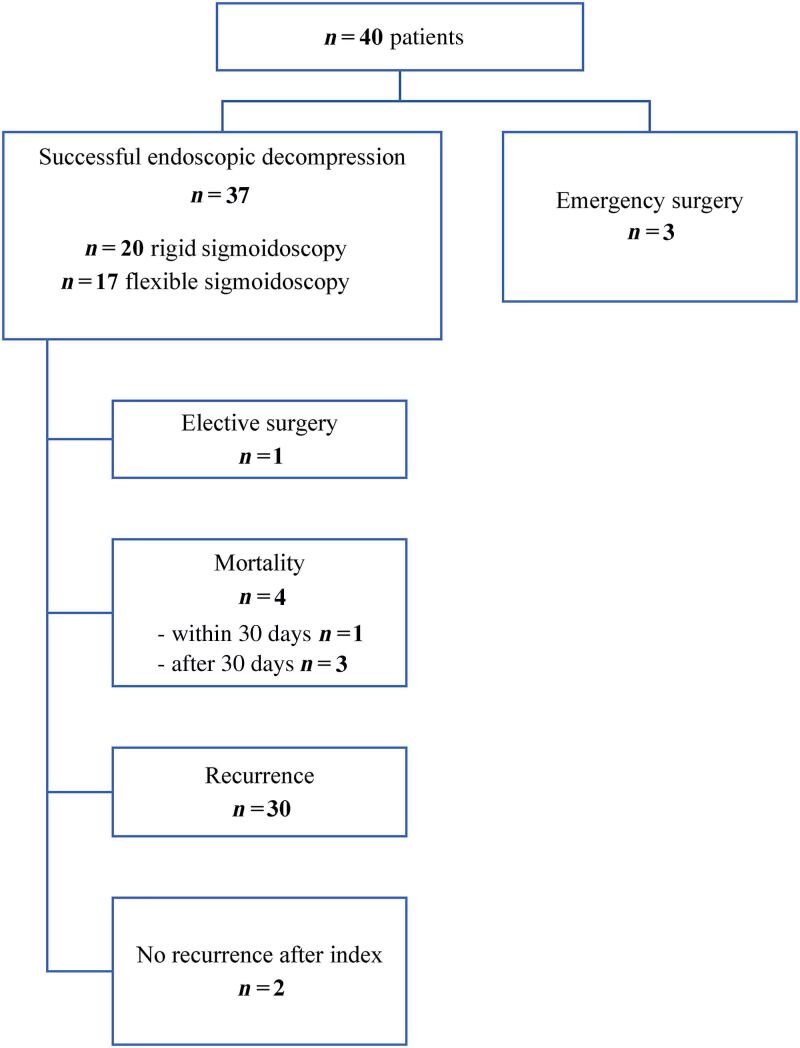

All 40 patients received successful initial management during the index admission; 37 (92.5%) were successfully decompressed by rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy. Three patients had peritonitis and required emergency Hartmann’s procedure. Only one patient was definitively treated by planned sigmoidectomy following the index admission. One (2.5%) conservatively treated patient died of SV within 30 days. A further three patients died within 4–12 weeks, without a recurrence, due to other medical illness (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Initial management of index admission and further progression following conservative management

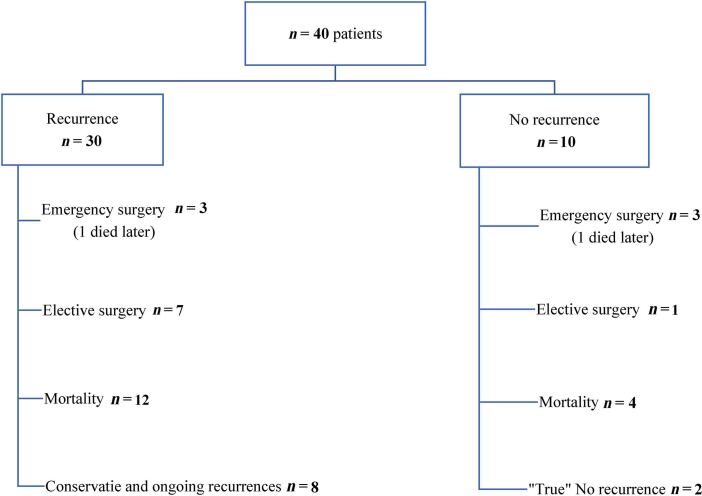

A total of 30 patients (75%) presented with recurrence after the index admission during the follow-up period. The number of recurrences ranged between one and five episodes. The average time until recurrence was 86 days. There was no recurrence following elective or emergency surgical resection. Out of the remaining 10 patients, only 2 (5%) are considered true nonrecurrences while the rest either underwent definitive surgery [n=4] or died [n=4] after the index admission (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Recurrence rate and further progress following recurrence

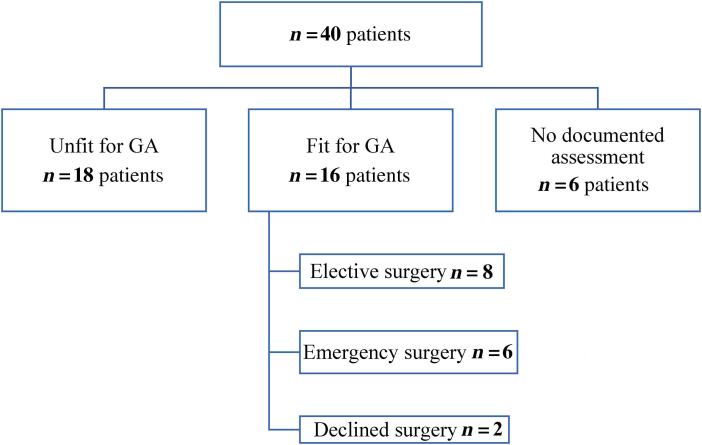

Overall, 34 patients (85%) were assessed for their fitness for general anaesthesia; 6 patients (15%) had no documented reason for not having surgery. Interestingly, all of them had two or fewer episodes of volvulus. This might reflect our surgeons’ tendency to consider surgery after multiple recurrences (Figure 3). A total of 18 patients (45%) were deemed unfit for elective or emergency surgery after assessment by a surgeon, an anaesthetist or both. Of the 16 (40%) who were deemed fit, 6 underwent emergency surgery and 10 were offered elective surgery; however, 2 declined. The elective surgery was performed after the index admission in one patient, the second episode in two patients, and after more than two episodes in five patients (Table 2).

Figure 3 .

Assessment of fitness and further management

Table 2 .

Timing of elective surgery

| n=8 patients | |

|---|---|

| Time of surgery | Number of patients |

| After 1 episode | 1 |

| After 2 episodes | 2 |

| After 3 episodes | 1 |

| After 4 episodes | 2 |

| After 5 episodes | 2 |

In total, 26 patients (65%) received endoscopic decompression only, 8 (20%) had planned definitive resection and 6 (15%) had emergency surgery. Of the 16 patients (62%) in the decompression group who died at the end of the follow-up, 7 deaths were related to SV. After elective surgery, regardless of the ASA grade, all patients survived until the end of the follow-up period. Two out of six (33%) mortalities were recorded among the emergency surgery group (Tables 3–5).

Table 3 .

Mortality rates for ASA grade 2 and management group (30 days after the index admission and total for the follow-up period)

| Mortality | ASA 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=14) | Conservative only (n=6) | Emergency surgery (n=2) | Elective surgery (n=6) | |

| 30-day | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 3 (23%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (50%) | 0 |

Table 4 .

Mortality rates for ASA grade 3/4 and management group (30 days after the index admission and total for the follow-up period)

| Mortality | ASA 3/4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=26) | Conservative only (n=20) | Emergency surgery (n=4) | Elective surgery (n=2) | |

| 30-day | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 15 (56%) | 14 (70%) | 1 (25%) | 0 |

Table 5 .

Mortality rates for all patients and management group (30 days after the index admission and total for the follow-up period)

| Mortality | All patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=40) | Conservative only (n=26) | Emergency surgery (n=6) | Elective surgery (n=8) | |

| 30-day | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 18 (45%) | 16 (61.5%) | 2 (33%) | 0 |

When we compared the overall mortality among patients with ASA grade 3 or 4 in the three groups, elective surgery, emergency surgery, and decompression only, mortality rate was 0%, 25% and 70% respectively, whereas it was 0%, 50% and 33% in those with ASA grade 2 in the same three groups (Tables 3–5).

Chi-squared analysis of the results showed that the overall mortality rate was statistically significantly lower in patients who underwent elective surgery than in those who were managed with decompression only (p=0.003).

Discussion

The two objectives of SV treatment are relieving the acute obstruction by decompressing the twisted colon and preventing recurrence to avoid undesirable consequences. SV has been known historically since ancient Egyptian times and its management has evolved through the years from using strong laxatives to endoscopic decompression, operative reduction or fixation and definitive surgical resection.2,7–10

Current practice in the management of SV includes rigid or flexible endoscopy to assess sigmoid colon viability and to allow initial decompression of the colon. Urgent sigmoid resection is generally indicated when endoscopic detorsion of the sigmoid colon is not possible and in cases of nonviable or perforated colon.6 The guidelines strongly recommend early sigmoid colectomy either open or laparoscopically after resolution of the acute phase of SV to prevent recurrent volvulus.1,6 Basato et al compared outcomes of surgical treatment of SV versus conservative management only in patients with similar ASA grade. They found better survival rates in the surgical group even in patients with ASA 4.11

In high-risk patients who are not fit enough for general anaesthesia, sigmoid resection under local anaesthesia has been reported as an alternative option.12 Tavassoli et al reported satisfactory results of minimally invasive sigmoid colectomy through a small transverse incision in 14 patients.13 Endoscopic fixation of the sigmoid colon known as percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC) using one or two tubes may be beneficial in patients for whom operative interventions present a prohibitive risk or those who have failed surgical treatment.12 In a recent systematic review, PEC insertion was associated with a mortality risk of 9.7% and a morbidity rate of 25%. The authors reported high risk of recurrence after removal of one or both PEC tubes.14

Our study showed that all patients who presented with uncomplicated SV were successfully decompressed by endoscopic measures. A minority presented with peritonitis and underwent emergency Hartmann’s procedure. Endoscopic fixation is not currently available in our trust. Most patients were assessed for definitive surgery after decompression. About 80% of patients had recurrent SV; however, we believe that the actual risk of recurrence is higher; as most of the patients who did not have recurrence either died or were operated on soon after the index attack. There was no recurrence after elective or emergency surgery. The mortality rate was lower in patients who underwent elective sigmoid colectomy regardless of ASA grade when compared with decompression only. Admittedly, the selection process of this cohort is a source of bias. However, it emphasises the importance of case selection to provide the best possible outcome for those patients.

A recent poll was conducted by the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (ASGBI) on Twitter asking surgeons about the preferred timing of elective surgery for SV. Most (75%) voted for surgery after recurrent admissions, 23% voted for early surgery on the index admission whereas 2% will never consider surgery at all.15 In a survey of the Members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons in 2018, 81.2% of surgeons would perform sigmoid colectomy on the index admission in 1–7 days postdetorsion and 49.7% would perform a laparoscopic colectomy.16 In our study, 87.5% of elective sigmoid resections were performed after recurrent attacks. Few patients with low ASA grade have not had elective surgery. Those patients had only one or two recurrences so far. It appears that our department is in agreement with the majority of ASGBI members. However, we propose that semi-elective surgery during or soon after the index admission is potentially preferable to the current approach of waiting for the inevitable recurrence. We recommend early assessment of fitness during the index admission with a clear plan for either definitive surgery or continuing conservative management.

Endoscopic decompression with either rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy is used as a temporary measure to simply convert the emergency condition to a semi-elective situation that facilitates medical optimisation of the patient’s comorbidities and preparation of the bowel prior to the definitive surgery. Operative intervention should be considered early during the index admission or soon after in appropriate patients in order to obviate later emergency surgery and curtail morbidity and mortality.

Early surgical treatment of SV offers multiple benefits; stopping the recurrence of a condition with high tendency to recur if treated only conservatively, reducing the economic burden on the already stretched health resources and decreasing the mortality risk. We admit that there might be a risk of selection bias; however, this disease is very difficult to subject to randomised controlled trials. Our study provides considerable evidence that this cohort of patients may be best treated by performing early definitive surgical resection after initial endoscopic decompression.

Conclusion

In patients with SV, regardless of ASA grade, performing early definitive surgery following initial endoscopic decompression resulted in statistically significant lower mortality rate.

Declaration

This study has been approved by the clinical audit office at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation trust with audit reference number SS/042/18.

References

- 1.Naveed M, Jamil LH, Fujii-Lau LLet al. American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in the management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction and colonic volvulus. Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 91: 228–235. 10.1016/j.gie.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gingold D, Murrell Z. Management of colonic volvulus. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2012; 25: 236–244. 10.1055/s-0032-1329535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinshaw DB, Carter R. Surgical management of acute volvulus of the sigmoid colon; a study of 55 cases. Ann Surg 1957; 146: 52–60. 10.1097/00000658-195707000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlberg M, Hallqvist Everhov Å. Entrapment is an essential feature of sigmoid volvulus. ANZ J Surg 2020; 90: 1540–1541. 10.1111/ans.15758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishibashi R, Niikura R, Obana Net al. Prediction of the clinical outcomes of sigmoid volvulus by abdominal x-ray: AXIS classification system. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2018; 2018: 1–5. 10.1155/2018/8493235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel JD, Feingold DL, Stewart DBet al. Clinical practice guidelines for colon volvulus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum 2016; 59: 589–600. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellinger MD, Steinhagen RM. Colonic volvulus. In: Wolf BG. The ASCRS Text-Book of Colon and Rectal Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 286–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treves F. Intestinal Obstruction, its Varieties with Their Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea's Son & Company; 1884. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall-Craggs EC. Sigmoid volvulus in an African population. Br Med J 1960; 1: 1015–1017. 10.1136/bmj.1.5178.1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepherd JJ. Treatment of volvulus of sigmoid colon: a review of 425 cases. Br Med J 1968; 1: 280–283. 10.1136/bmj.1.5587.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basato S, Lin Sun Fui S, Pautrat Ket al. Comparison of two surgical techniques for resection of uncomplicated sigmoid volvulus: laparoscopy or open surgical approach. J Visc Surg 2014; 151: 431–434. 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy, Interventional procedures guidance [internet]. London: NICE; 2006. (Clinical guidance [IPG161]). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg161. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tavassoli A, Maddah G, Noorshafiee Set al. A novel approach to minimally invasive management of sigmoid volvulus. Acta Med Iran 2016; 54: 640–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson S, Hamed MO, Shabbir J. Management of sigmoid volvulus using percutaneous endoscopic colostomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2020; 102: 654–662. 10.1308/rcsann.2020.0162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ASGBI. #ASGBIEGS virtual meeting 9th September: A sigmoid volvulus, successfully decompressed, in a low risk (<5% NELA predicted mortality) patient should have surgery? On the index admission (22.6%) Never (1.9%) After recurrent admission (75.5%) [Twitter]. https://twitter.com/asgbi/status/1293484091816529921 (cited November 2020).

- 16.Garfinkle R, Morin N, Ghitulescu Get al. From endoscopic detorsion to sigmoid colectomy-The Art of managing patients with sigmoid volvulus: A survey of the members of the American society of colon and rectal surgeons. Am Surg 2018; 84: 1518–1525. 10.1177/000313481808400961(cited October 2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]