Abstract

Introduction

To determine the current (pre-COVID-19) provision of supervised exercise training (SET) for patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in UK Vascular Centres.

Methods

Hospital Trusts delivering vascular care to patients with PAD were identified from the National Vascular Registry and asked to complete an online questionnaire on their provisions for SET. If a centre offered SET, they were asked questions to determine whether the programme was compliant with NICE guidelines and the difficulties they faced delivering the service. If centres did not offer SET, they were asked what obstacles prevented them implement SET.

Results

Of the 78 UK vascular centres, 59 (76%) responded and were included in the audit. Of these, 27 (46%) were able to offer SET but only 21 (36%) could offer it to all their patients with PAD. Only four (6.8%) offered SET that was fully compliant with current NICE guidelines. Reasons identified included insufficient funding, lack of resource and poor patient compliance.

Conclusions

The benefits of SET are well established yet the availability of the service in the UK is poor. The reasons for this are readily identified but have not yet been overcome. Research on novel methods of delivering supervised exercise that mitigates existing barriers, such as home exercise with remote monitoring, should be prioritised to facilitate optimal management for our patients with PAD.

Keywords: Peripheral arterial disease, Intermittent claudication, Exercise therapy, Quality of health care, Health resources

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) affects one-quarter of those aged over 55 years, with varying symptomology.1 Many suffer intermittent claudication, which impairs quality of life and can progress to rest pain, critical limb ischaemia, gangrene, amputation and death.2 Patients with PAD are also at increased risk of cardiovascular events, impairing quality of life and survival compared with the normal population.3,4

Exercise is known to be an effective treatment for PAD. It promotes collateral circulation and encourages metabolic adaptations at a mitochondrial level, which are most effective when the patient walks up to the point of maximal pain.5 The ideal, minimum exercise requirements are two 30min sessions per week for 12 weeks, although improvements have been shown to be dose-dependent.6–9 If adhered to, SET results in improved functional ability, muscle strength, endurance, cardiovascular fitness and quality of life in the majority of patients and is comparable with, if not better than, results achieved by often complex revascularisation procedures.10–15 It has also been shown to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, be cost-effective, produce long-lasting effects and be essentially complication-free.16–19 However, adherence is a problem and therefore exercise training has only convincingly been shown to be effective when supervised.20,21

In the UK, the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE) recommends 2h of supervised exercise per week for 12 weeks, with exercises designed to work people to the point of maximal pain, as a first-line treatment for patients presenting with intermittent claudication.22

Previous research suggesting that the availability of SET is deficient suffered from poor response rates; though sufficient enough to indicate there is a significant problem.23,24 Without SET, patients may progress unnecessarily to endovascular or open surgical procedures, achieving no better results than SET but with the attendant morbidity, mortality and cost to our NHS.14,15 They are also denied the additional benefits of exercise training, such as improved wellbeing, quality of life and mental health and reduced cardiovascular risk.25–28

The limited availability of SET is a major obstacle to delivering optimum care for patients with PAD. Quantifying the extent of the problem, if any, and understanding the barriers to successful implementation should allow the development of well-considered, effective solutions for PAD patients.

Methods

This was a questionnaire-based UK-wide audit.

An online questionnaire was designed by the Academic Surgery Unit at the University of Manchester. The questionnaire first identified whether SET was offered or not. If it was, questions were posed to delineate the setup of the respective exercise class and determine whether it was NICE-compliant (Appendix A). If SET was not offered, questions were posed to determine why this was the case (Appendix B).

The National Vascular Registry (NVR) annual report was used to identify Hospital Trusts that provided lower limb vascular services (n=86).29 This list was then cross-checked with the respective hospital websites to remove Trusts that had stopped offering lower limb vascular services and/or merged with another Trust since the publication of the report (n=8). The remaining 78 trusts were included in the audit.

The Vascular Training Programme Directors (TPDs) from each of the training regions were then contacted to identify the Clinical Leads in each trust. The Clinical Leads were then e-mailed a link to the questionnaire asking either themselves or a nominated deputy to complete the questionnaire. If there had been no response after 4 weeks, the Vascular Secretaries of these Trusts were contacted to provide a suitable secondary contact, who was then e-mailed the questionnaire. Reminder e-mails were then sent out to those contacts who were yet to fill the questionnaire after 2 and 4 weeks.

Questionnaires were sent out between July and December 2019 with the last response received in January 2020.

All responses from the questionnaire were automatically stored in a master database in Microsoft Excel. Where there was more than one response for a Trust, these responses were merged when in agreement. If there was disagreement, the Trust was contacted to provide clarification before recording the final response.

Results were reported as simple summary statistics (total sum and percentages).

Results

A total of 75 responses were received, representing 59 of the 78 trusts (75.6%); 13 Trusts gave more than one response but were identical for 11 of these, and so could be merged. In the remaining Trusts (n=2), clarification was sought and the final response amended.

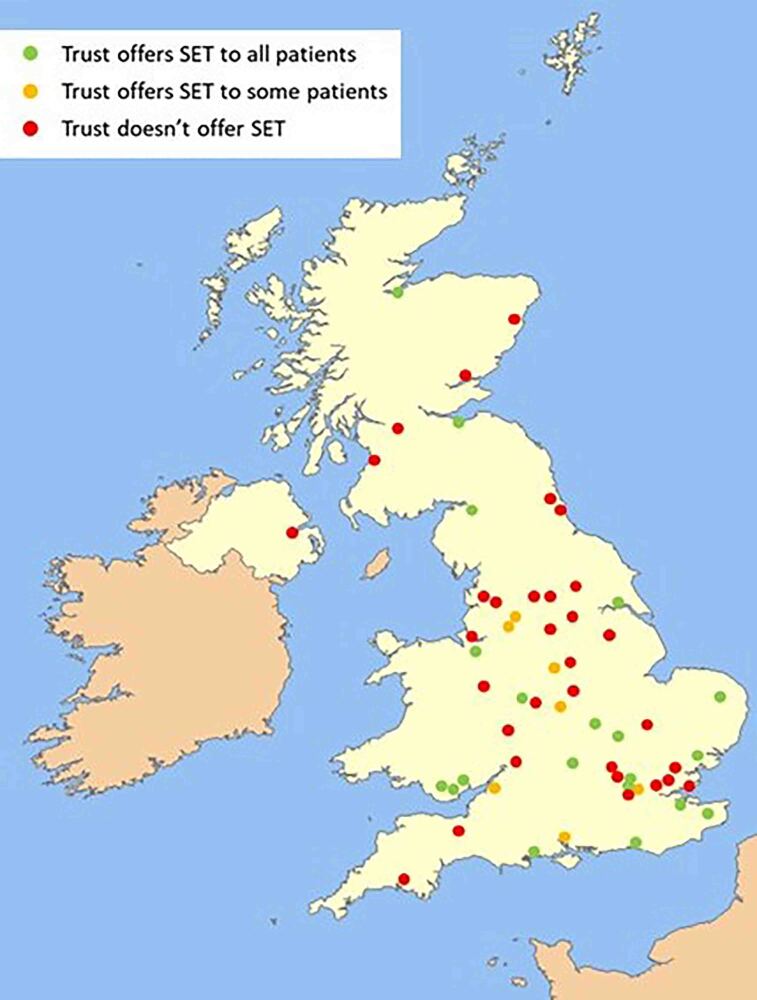

The majority of respondents were Vascular Surgery Consultants (n=37, 49.3%), followed by Vascular Nurse Specialists (n=27, 36.0%), Higher Specialty Trainees (n=5, 6.7%), Physiotherapists (n=1, 1.3%) and other responders (n=5, 6.7%). The respondent Trusts were well spread out geographically across the UK (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Trusts with a questionnaire response included in the final analysis showing good geographic spread across the UK

Trusts that offer SET

Of the 59 trusts who responded, only 27 (45.8%) offered any kind of SET service, with only 21 (35.6%) able to offer a service to all their patient population (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

SET provisions across trusts demonstrating only 45.8% are able to offer SET to some or all of their patients and only 35.6% to all. SET = supervised exercise training.

Seven trusts had a service available but only for some of their patients; the reasons cited for this were:

-

(i)

Lack of funding at certain sites (n=4, 57.1%)

-

(ii)

Location of spoke hospital meant SET was not feasible at distant locations (n=2, 28.6%)

-

(iii)

Lack of facilities at certain sites (n=1, 14.3%)

Of all Trusts offering any kind of SET service, two (7.4%) recorded >80% of those eligible actually started a programme (Figure 3).

Figure 3 .

Proportion of patients eligible who actually start a programme demonstrating that there is a problem with recruitment on to SET programmes even in centres where they exist. SET = supervised exercise training.

Specialist Nurses were the Health Professional who ran most of the classes (n=11, 40.7%), followed by physiotherapists (n=9, 33.3%), other health professionals (n=6, 22.2%) and doctors (n=1, 3.7%). Most classes were hospital based (n=18, 66.7%) with the remainder in community centres or gyms (n=8, 29.6%) with the exception of one Trust that was running a combined home/hospital programme where patients were given a home exercise programme but also had the option of attending an in-hospital class.

Most classes offered were between 45min and 60min duration (n=19, 70.1%) with the majority of centres (n=17, 62.3%) able to offer one class per week. This meant that only eight (29.6%) Trusts offered the minimum of 2h of SET per week, as recommended by NICE (Figure 4). Most trusts do offer a programme at the overall duration of 12 weeks recommended by NICE (n=15, 55.6%) (Figure 5), with 23 (85.2%) working patients to the point of maximal pain.

Figure 4 .

Minutes of SET offered per week. Most programmes do not adhere to the NICE recommendation of 2h of SET per week. SET = supervised exercise training.

Figure 5 .

Overall duration of SET. Most centres do adhere to the NICE recommendation of an overall duration of at least 12 weeks.

Overall, 6 (22.2%) of the 27 (22.2%) Trusts that offered SET fully adhered to the NICE recommendation. Of these, 2 could not offer their service to their entire patient population, leaving a total of 4 (6.8%) of the 59 respondent Trusts offering a fully NICE-compliant service to all of their patients (Figure 6).

Figure 6 .

Trusts that offer NICE-compliant SET services demonstrating 6.8% of Vascular Centres offer a NICE-compliant service to all of their patients. NICE = National Institute for Health Care and Excellence; SET = supervised exercise training.

There were 13 Trusts (48.1%) who felt they had a problem with patient adherence, citing the following reasons:

-

(i)

Patients unable or unwilling to exercise (n=6, 38.5%);

-

(ii)

Patients unable or unwilling to travel (n=12, 84.6%);

-

(iii)

Cost of attending SET (travel and/or parking) (n=7, 53.8%);

-

(iv)

Patient’s do not see the value (n=6, 46.2%).

Overall, just over half (n=19, 52.8%) of the 36 responders who had a SET programme were satisfied with their organisation’s current provisions.

Trusts that do not offer SET

There were 32 (54.2%) Trusts that reported not currently offering a SET service. Of these 32, 12 (37.5%) had plans to introduce a service in the future and 10 (31.3%) had previously had a service that had since stopped. The reasons given for this were:

-

(i)

Centralisation of services (n=2, 20%);

-

(ii)

Lack of funding from commissioners (n=3, 30%);

-

(iii)

Poor patient adherence (n=3, 30%);

-

(iv)

Lack of resource (n=1, 10%);

-

(v)

Service only ever offered as part of a research programme that had now ceased (n=1, 10%).

These Trusts reported the following barriers to setting up and delivering a SET programme for their patients:

-

(i)

Financial constraints (n=28, 87.5%);

-

(ii)

Management/commissioners do not see the value (n=12, 37.5%);

-

(iii)

Patient adherence (n=4, 12.5%);

-

(iv)

Clinicians do not see the value (n=3, 9.4%);

-

(v)

Logistical challenges (n=2, 6.3%);

-

(vi)

Lack of resources (n=2, 6.3%).

Discussion

Most UK Vascular Centres do not currently offer a SET service and, even in those that do, it is often not available to all of their patient population and very few (6.8% overall) have a service that complies with NICE guidance. Centralisation of services and the extra logistical challenges this poses was identified as a previously described reason for this, with a hub hospital having to deliver a service to a spoke that can be over 20 miles away. There was also a problem in getting patients to start a SET programme, with most Trusts reporting that only a proportion of their eligible patients began a class. Adherence to the programme was also a problem and combining this with the already poor availability of SET means that the proportion of PAD patients in the UK who are correctly treated with SET as a first line is very low indeed.

When trying to understand why offering SET services is so problematic, it is important to analyse what the common pitfalls are. Trusts do not seem to have a problem providing classes at the ideal length of 45–60min, nor do they struggle with overall durations of 12 weeks. Where they do fail is in offering SET sessions more than once a week, and it was mainly this that meant that most programmes are not NICE compliant. This perhaps suggests that lack of time and resource are significant barriers. Providing 2h per week of classes for every patient with PAD is likely to be a full-time commitment for at least two physiotherapists or vascular nurse specialists – a quota that is almost impossible to fill in a system where there are already major staff shortages.30 SET also requires a dedicated gymspace, which may not be accessible.

Financial constraint was the most commonly reported barrier which is difficult to understand when considering SET has already been proven to be highly cost-effective and is a NICE recommended treatment, meaning commissioning of such a service should be a priority.31 Perhaps this is not the case due to another frequently reported barrier – patient adherence – with commissioners unlikely to be motivated to fund a service that is poorly attended.

One of the reasons identified for this poor adherence is the inability and unwillingness of patients to travel and pay its associated expense, a problem that is potentially going to get worse with further centralisation of vascular services. It is interesting that, despite this, most services currently set up are hospital-based. This means that patients, who may well be working, need to attend hospital during its normal working hours, which may be inconvenient. In addition to this, it is known that older patients are more likely to prefer community-based training over that in a hospital.32,33 This suggests that exercise services should be offered either in the community or in the patient’s own home, but so far these types of programmes have proven to be less effective than traditional in-hospital SET, with the lack of supervision a key reason for this.34–37

It is interesting to note one Trust employing a service that allows the patient to choose whether they exercise at home or in the hospital – this is potentially a solution that may be employed, especially as patient choice is known to improve compliance with exercise training.38,39

Overall, the most commonly reported barriers are analogous to those cited in a similar study in 2009, and suggest that little progress has been made in the interim. Finding ways to reduce the cost of SET, in terms of finance, time and resource while providing the behaviour change techniques that supervision affords is clearly important to increase provision for PAD patients across the UK.

Remotely supervised exercise training (RESPECT) is a potential solution currently in the feasibility stage. RESPECT is a home-based exercise programme that employs the use of an activity tracker linked to an online platform. This allows patient exercise to be supervised remotely by a vascular specialist nurse and/or physiotherapist. This should encourage similar behaviour changes seen in traditional supervision, while not requiring the latter’s time and resource and allowing the patient to exercise at their own convenience.

This study is the largest audit of SET provisions in the UK, with a spread of respondents across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, although a clear limitation is that not all Trusts provided a response. However, the overall response rate was over 75%, which should be a good representation of current practice. Furthermore, even if those Trusts that did not respond did have a fully NICE-compliant SET service ,the overall provisions of such a service would still be less than 30%. Another limitation that must also be acknowledged is the questionnaire methodology, which can be prone to bias and inaccuracies. The anonymous nature of the questionnaires should reduce response bias, and with over 85% of respondents vascular surgery consultants or specialist nurses, responses should be accurate and a fair representation of current practice.

This data was collected pre-COVID-19, and it is expected that during the pandemic the ability of Vascular Centres to deliver SET will have been impaired even further. However, this may present an opportunity to redesign provision in a way that removes the need for the patient to visit a hospital – something that seems to affect adherence to programmes and thus commissioning.

A 6.8% compliance rate to first-line NICE guidance is clearly concerning. It is hard to imagine any other disease process that has such poor availability of first-line management. To provide an optimum service for patients with PAD, efforts need to be made to address the current pitfalls of SET concentrating on:

-

(i)

Reducing the financial cost;

-

(ii)

Reducing the time and resource burden;

-

(iii)

Allowing patients to access programmes in their own community;

-

(iv)

Producing a programme which is scalable and deliverable across long distances.

Conclusion

Very few (6.8%) UK Vascular Centres currently offer a NICE-compliant SET service for all of their patients. The main barriers to SET are financial constraints and patient adherence. Efforts should be made to produce new SET programmes that overcome these barriers, which would enable optimum care for patients with PAD in the UK.

Acknowledgements

P. Schofield, IT Services Manager (University of Manchester), Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester, M23 9LT.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Quality and Outcomes Framework Programme NICE cost impact statement July 2011. 2011;1–6.

- 2.Surgeon V, Street P. Critical limb ischaemia: management and outcome. Report of a national survey. The vascular surgical society of great Britain and Ireland. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1995; 10: 108–113. 10.1016/S1078-5884(05)80206-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagle KA, Rihal CS, Foster EDet al. Long-term survival in patients with coronary artery disease: importance of peripheral vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994; 23: 1091–1095. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90596-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gent M. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348: 1329–1339. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09457-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCombs PR, Subramanian S. The benefit of exercise in intermittent claudication: effects on collateral development, circulatory dynamics and metabolic adaptations. Ann Vasc Surg 2002; 16: 791–796. 10.1007/s10016-001-0222-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolaï SPA, Hendriks EJM, Prins MH, Teijink JAW. Optimizing supervised exercise therapy for patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 1226–1233. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.06.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney CL, Miller MD, Chataway TK, Spark JI. A randomised controlled trial of supervised exercise regimens and their impact on walking performance, skeletal muscle mass and Calpain activity in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 47: 304–310. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner AW. Exercise rehabilitation for peripheral artery disease: an exercise physiology perspective with special emphasis on the emerging trend of home-based exercise. Vasa 2015; 44: 405–417. 10.1024/0301-1526/a000464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlon R, Morlino T, Maiolino P. Beneficial effects of exercise beyond the pain threshold in intermittent claudication. Ital Hear J 2003; 4: 113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harwood A-E, Cayton T, Sarvannandan Ret al. A review of the potential local mechanisms by which exercise improves functional outcomes in intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 2015; 30: 312–320. 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazari FAK, Carradice D, Rahman MNAAet al. An analysis of relationship between quality of life indices and clinical improvement following intervention in patients with intermittent claudication due to femoropopliteal disease. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 77–84. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franz RW, Garwick T, Haldeman K. Initial results of a 12-week, institution-based, supervised exercise rehabilitation program for the management of peripheral arterial disease. Vascular 2010; 18: 325–335. 10.2310/6670.2010.00053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mockford KA, Gohil RA, Mazari Fet al. Effect of supervised exercise on physical function and balance in patients with intermittent claudication. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 356–362. 10.1002/bjs.9402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frans FA, Bipat S, Reekers JAet al. Systematic review of exercise training or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for intermittent claudication. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 16–28. 10.1002/bjs.7656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahimastos AA, Pappas EP, Buttner PGet al. A meta-analysis of the outcome of endovascular and noninvasive therapies in the treatment of intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54: 1511–1521. 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolaï SPA, Teijink JAW, Prins MH. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of supervised exercise therapy with or without feedback versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 348–355. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratliff DA, Puttick M, Libertiny Get al. Supervised exercise training for intermittent claudication: lasting benefit at three years. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 34: 322–326. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aherne T, Mchugh S, Kheirelseid EAet al. Comparing supervised exercise therapy to invasive measures in the management of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Surg Res Pract 2015; 2015: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakamoto S, Yokoyama N, Tamori Yet al. Patients with peripheral artery disease who complete 12-week supervised exercise training program show reduced cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. Circ J 2009; 73: 167–173. 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savage P, Ricci MA, Lynn Met al. Effects of home versus supervised exercise for patients with intermittent claudication. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001; 21: 152–157. 10.1097/00008483-200105000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fokkenrood HJP, Bendermacher BLW, Willigendael EMet al. Supervised exercise therapy versus non-supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication. In: Fokkenrood HJ. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. pp. CD005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National institute for Health and care Excellence. Peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management | 1-Guidance | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harwood A, Smith G, Broadbent Eet al. Access to supervised exercise services for peripheral vascular disease patients. Bull R Coll Surg Engl 2017; 99: 207–211. 10.1308/rcsbull.2017.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shalhoub J, Hamish M, Davies AH. Supervised exercise for intermittent claudication - An under-utilised tool. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2009; 91: 473–476. 10.1308/003588409X432149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical Activity Level and Health-Related Quality of Life in the General Adult Population: A Systematic Review. Vol. 45, Preventive Medicine. New York: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JMet al. Home-Based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease A randomized clinical trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 2013; 310: 57–65. 10.1001/jama.2013.7231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pattyn N, Cornelissen VA, Eshghi SRT, Vanhees L. The Effect of Exercise on the Cardiovascular Risk Factors Constituting the Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Vol. 43, Sports Medicine. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Polenakovic Met al. Exercise and Mental Health. Vol. 106, Maturitas. Shannon: Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2017. pp. 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Programme VSQI. 2018. Annual Report | VSQIP [Internet]. https://www.vsqip.org.uk/reports/2018-annual-report/ (cited February 2020).

- 30.Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B, Seccombe I. A critical moment: NHS staffing trends, retention and attrition. 2019.

- 31.Bermingham SL, Sparrow K, Mullis Ret al. The cost-effectiveness of supervised exercise for the treatment of intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013; 46: 707–714. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraal JJ, Peek N, van den Akker-Van Marle ME, Kemps HMC. Effects and costs of home-based training with telemonitoring guidance in low to moderate risk patients entering cardiac rehabilitation: The FIT@Home study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2013; 13: 82. 10.1186/1471-2261-13-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunasekera RC, Moss J, Crank Het al. Patient recruitment and experiences in a randomised trial of supervised exercise training for individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Nurs 2014; 32: 4–9. 10.1016/j.jvn.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makris GC, Lattimer CR, Lavida A, Geroulakos G. Availability of supervised exercise programs and the role of structured home-based exercise in peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 44: 569–575. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mays RJ, Rogers RK, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG. Community walking programs for treatment of peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 1678–1687. 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vemulapalli S, Dolor RJ, Hasselblad Vet al. Supervised vs unsupervised exercise for intermittent claudication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J 2015; 169: 924–937. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galea MN, Weinman JA, White C, Bearne LM. Do behaviour-change techniques contribute to the effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with intermittent claudication? A systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013; 46: 132–141. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.03.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chmelo E, Crotts C, Newman Jet al. Heterogeneity of physical function responses to exercise training in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 462–469. 10.1111/jgs.13322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garber C, Blissmer B. American college of sports medicine position stand. quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2011; 43: 1334–1359. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]