Abstract

Chronic wounds occur as a result of a disordered healing process. They can be associated with complications such as chronic pain and infection, but also rarely lead to malignant transformation. There have been few cases of squamous cell carcinomas arising in a surgical wound. We present the case of a 67-year-old patient who developed an advanced invasive squamous cell carcinoma seven years post laparostomy for abdominal compartment syndrome. Surgical resection was not possible due to the advanced stage of the malignancy. This case highlights the importance of good wound care, suspecting malignant development in a non-healing chronic surgical wound site, and the importance of using histological analysis to inform surgery when involving a chronic wound.

Keywords: Laparostomy, Abdominal compartment syndrome, Squamous cell carcinoma, Marjolin’s ulcer, Chronic wound

Introduction

Many complications can arise from chronic wounds, including the development of Marjolin’s ulcer. This is a malignancy which is most commonly squamous cell carcinoma, but can be basal cell carcinoma, melanoma or sarcoma.1 It is most associated with chronic wounds from burns, but has also been reported in association with osteomyelitis, neuropathy, pressure sores, vascular insufficiency, as well as surgical incisions.1 It is most frequently found in the lower limbs as well as the scalp, though other sites have also been implicated.1 The incidence of Marjolin’s ulcer varies depending on the wound and site, but a general incidence of 0.7% has been reported in patients with existing scars.2 Diagnosis is through incisional biopsy and histological analysis, and management is usually surgical through wide local excision.

Cases of Marjolin’s ulcer occurring in an abdominal surgical incision site are rare. Here, we present an unusual case of an advanced invasive squamous cell carcinoma in the context of chronic wound healing following a laparostomy for abdominal compartment syndrome.

Case report

The following case report demonstrates the sequence of events over seven years which led to the development of squamous cell carcinoma in the laparostomy wound (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Timeline of events

| 2002 | Paranoid schizophrenia. |

| 2011 | Myocardial infarction with 4× coronary artery bypass grafting and mitral valve repair. |

| 8th Oct 2013 3am | Collapse with 7cm abdominal aortic aneurysm, CPR with return of spontaneous circulation, open repair with intrarenal cross clamp. |

| 8th Oct 2013 8pm | Abdominal compartment syndrome, laparostomy performed with closure with bogota bag. |

| 10th Oct 2013 | Burst abdomen, refashioning of laparostomy. |

| 14th Oct 2013 | 2 vicryl meshes placed along wound. |

| Apr 2014 | Caecal colocutaneous fistula development at lower end of wound. |

| Nov 2016 | Defuncting loop ileostomy constructed in left iliac fossa. |

| Dec 2016 | Closure of colocutaneous caecum fistula. |

| Jan 2017 | Reversal of left iliac fossa ileostomy. |

| March 2019 | Regular follow-up, no evidence of superficial infection or recurrent fistula, ongoing orthotics for refitting support. |

| Sep 2019 | Reducible incisional hernia 28cm×20cm, planned botox injections (Feb 2020) and reconstructive surgery (March 2020). |

| March 2020 | Operation delayed due to pandemic. Wound dehiscence, increase in size of defect, discharging. |

| Early May 2020 | Presentation with hypercalcaemia. CT of the hernia showed soft tissue thickening with nodularity. Nuclear medicine scan showed no bone metastases. |

| 27th May 2020 | Abdominal wound debridement of necrotic and chronically infected tissue, and abdominal wall reconstruction. |

| June 2020 | Histology shows poorly differentiated sarcomatoid/spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, stage pT3tumour deemed to be unresectable as invading intraabdominal cavity and peritoneum, patient given best supportive management. |

| July 2020 | Patient died. |

A 60-year-old plasterer collapsed at home with abdominal pain. He had previous paranoid schizophrenia and a previous myocardial infarction with four coronary artery bypass grafts and a mitral valve repair. Computerised tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a large 7cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with retroperitoneal bleeding. This ruptured immediately prior to induction, and output was lost with pulseless electrical activity. He underwent successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation for 3 minutes with return of spontaneous circulation. Open AAA repair was conducted with an infrarenal cross-clamp.

Sixteen hours later, he had worsening renal function and hyperkalaemia. Examination revealed a tense abdomen suggestive of abdominal compartment syndrome. Laparostomy was performed showing extensive retroperitoneal haematoma and oedema, and 500ml haemoserous fluid was removed with bogota bag closure. On day 2, he had a burst abdomen with exposed bowel loops, and the laparotomy was refashioned. On day 6, two vicryl meshes (2×26cm×34cm) were placed along the upper and lower aspects of the wound sutured to the rectus sheath with number 1 vicryl to hold in abdominal contents. Wound edges were unable to be brought together, therefore Gamgee packs and aquacel melolin gauze were packed over on top of the mesh. Follow-up noted a large incision hernia and granulation over the abdominal wound defect which had not fully re-epithelialised.

Six months later, he was admitted with a colocutanous fistula at the lower end of the wound, which was discharging 200–300ml/day faecal material. This was unable to be managed with dressings and stoma bags. CT showed caecum at the fistula site, and sigmoidoscopy demonstrated no lesions up to the proximal transverse colon. Two years after this, he had an elective defunctioning loop ileostomy in the left iliac fossa separate from the main laparotomy wound for the persistent colocutaneous fistula. This was a long hospital admission with multiple complications of dehydration secondary to high stoma output, paralytic ileus, acute kidney injury, sepsis and a high output stoma with leakage. One month after, he had closure of the colocutaneous caecum fistula with minimal adhesions and scarring, the stoma was excised and the abdominal wall was closed with sublay surgimend 1.0 bovine collagen matrix 10cm×6cm. The following month he underwent reversal of left iliac fossa ileostomy.

During the next 2.5 years, he was regularly reviewed in clinic where his bowel habit had improved to 1–2 times a day, there was no evidence of superficial infection or recurrent fistula, and orthotic input was given for further abdominal support. There was an ongoing reducible 28cm×20cm surgical incisional hernia containing small and large bowel with good lateral abdominal wall complexes. CT showed no evidence of malignant change in the wound (Figure 1). Repair was scheduled in 6 months with bilateral endoscopic anterior component separation and open repair with biological matrix and closure of the defect and excision of the sac and overlying granulomatous skin, and botulinum toxin injections 4 weeks before the procedure.

Figure 1 .

Computerised tomography of the abdomen in axial view showing no evidence of malignant change in the wound

Due to the pandemic, the planned operation was delayed. During this time, the wound began to dehisce (Figure 2). This defect increased in size and was associated with putrid-smelling discharge. Seven years after the initial presentation, he presented to hospital with hypercalcaemia. Nuclear medicine bone scan of the whole body showed no evidence of osteoblastic bone metastases, and CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed an enlarged right axillary lymph node of 15mm, large dehiscence 16cm in length, a large ventral hernia measuring 25cm by 18cm, with the covering hernia showing soft tissue thickening with nodularity and interpreted as the appearance of the postsurgical mesh (Figure 3). Examination revealed irregular necrotic appearing skin, and later that month he underwent abdominal wound debridement of necrotic and chronically infected tissue and abdominal wall reconstruction with bridged intraperitoneal SurgiMend 3.0 22cm×15cm, fixed transfascially with interrupted 1 ethilon.

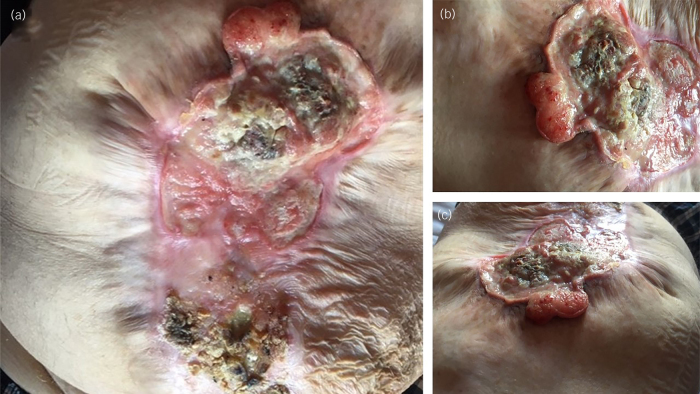

Figure 2 .

Photographs of the abdominal wound: (a) view of entire abdominal wall wound, (b) superior aspect of wound showing skin necrotic in appearance and (c) wound photographed from superior aspect to inferior

Figure 3 .

Computerised tomography of the abdomen in axial (a) and sagittal (b) views demonstrating large dehiscence and thickened superficial covering of the wound

A tissue sample was sent for histology. This was reported the following month with histological features of poorly differentiated sarcomatoid or spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, stage pT3. The likely source was skin in the absence of any identified primary. Lymphovascular space invasion was present with all margins involved. CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed enhancing mesh and reactive lymph nodes. Core biopsy of the right axillary lymph node showed no evidence of malignancy. As the tumour was found to be invading the intraabdominal cavity and peritoneum, it was deemed to be unresectable, and the patient was given best supportive treatment to manage his symptoms. Unfortunately, the patient died the following month.

Discussion

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when intra abdominal pressure rises to >20mmHg and is associated with resultant organ dysfunction.3 Varying rates have been reported post-laparotomy, with a low incidence following elective surgery, but a significant incidence post emergency procedure. For these patients, the definitive option is surgical decompression by laparotomy and an open abdomen in connection with a plastic membrane or Bogota bag. The wound is then closed at a later date, though for this patient the inability to oppose wound edges meant it was left to heal through secondary intention. This may have contributed to the development of the colocutaneous fistula in this patient. After surgical closure of the fistula, the patient had a three-year latency period where the wound was stable and there were no signs of infection or necrosis.

Marjolin’s ulcer often presents as a rapidly growing ulcerating lesion frequently associated with increased foul-smelling discharge in the site of a chronic wound.4 It is likely that the patient developed this while awaiting surgical revision of his hernia. There is considerable morbidity and mortality associated with a Marjolin’s ulcer, as they are more aggressive than primary skin malignancy, frequently metastasise early, and are associated with a high frequency of recurrence.2 Treatment should therefore be proactive, and guided through clinical, radiological, and pathological assessment.2 In this patient, histological analysis performed prior to surgery to inform treatment would have been beneficial and may have prevented unnecessary surgery. In a patient with changes in a previously stable chronic surgical wound site it is therefore important to have a high clinical suspicion of Marjolin’s ulcer and have a low threshold for biopsy and further evaluation.

The development of a Marjolin’s ulcer after abdominal surgery is rare, and literature search has revealed only four previous cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising from a laparostomy scar.4,5 This is the first case where the squamous cell carcinoma has been so advanced it was not surgically resectable.

Conclusion

Chronic wounds in abdominal laparotomy and laparostomy sites are potential areas for the development of Marjolin’s ulcer. Marjolin’s ulcer is associated with considerable mortality and morbidity, and prevention involves good wound care and treatment of infections. The gold standard diagnostic investigation of Marjolin’s ulcer is through biopsy and histological analysis. Changes in a previously stable non-healing chronic surgical wound site should have a low threshold for biopsy and further evaluation and histology results should inform surgery when involving a chronic non-healing wound.

References

- 1.Sadegh Fazeli M, Lebaschi AH, Hajirostam M, Keramati MR. Marjolin's ulcer: clinical and pathologic features of 83 cases and review of literature. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2013; 27: 215–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu N, Long X, Lujan-Hernandez JRet al. Marjolin's ulcer: a preventable malignancy arising from scars. World J Surg Oncol 2013; 11: 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick Aet al. Results from the international conference of experts on intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. I. Definitions. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32: 1722–1732. 10.1007/s00134-006-0349-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trindade EN, Pitrez FA, Souto M. Squamous cell carcinoma in a laparostomy scar. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2012; 25: 298–299. 10.1590/S0102-67202012000400017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birolini C, Minossi JG, Lima CFet al. Mesh cancer: long-term mesh infection leading to squamous-cell carcinoma of the abdominal wall. Hernia 2014; 18: 897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]