Abstract

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in children and adolescents, with an average worldwide prevalence of 5%. Up to 40% of young people continue to experience symptoms into adulthood. Young people with ADHD experience poorer outcomes than their peers across multiple domains, with treatment shown to reduce these risks. Primary care practitioners play an important role in healthcare provision for this group in the UK. However, many feel unsure about how best to provide support, reporting prescribing concerns and need for more evidence-based guidance. A lack of national data on primary care provision hinders efforts to improve access to care and optimise outcomes. This mixed-methods study aims to provide evidence that may be used to improve primary care services for young people aged 16–25 years with ADHD.

Methods and analysis

There are three interlinked work packages: (a) a mapping study including a survey of stakeholders (healthcare professionals, people with ADHD and commissioners) will map ADHD prescribing practice, shared-care arrangements, available support and practitioner roles by geographic locations across England for different respondent groups; (b) a qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews with stakeholders (10–15 healthcare professionals and 10–15 people with ADHD) will explore experiences of ‘what works’ and ‘what is needed’ in terms of service provision and synthesise findings; (c) workshops will integrate findings from (a) and (b) and work with stakeholders to use this evidence to codevelop key messages and guidance to improve care.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by Yorkshire and the Humber—Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee. Recruitment commenced in September 2022. Findings will be disseminated via research articles in peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations, public involvement events, patient groups and media releases. A summary of study findings will be shared with participants at the end of the study.

Trial registration number

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, Organisation of health services, MENTAL HEALTH, Child & adolescent psychiatry, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An English study, incorporating data from a broad range of stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, people with lived experience of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (eg, young people with ADHD and their supporters) and commissioners.

Addresses the evidence gap on current primary care provision for young people with ADHD in England, including identifying geographic variations in care, and understanding what works, and what is needed.

Comprehensive patient and public involvement, with study design inspired by patients who said that referrals, prescribing and other support from primary care staff (such as general practitioners) are key to young people managing living with ADHD.

Coproduction of guidance for primary care providers, informed by healthcare professionals and people with lived experience of ADHD.

A limitation is the use of convenience (non-probabilistic) sampling methods for surveying some stakeholder groups, meaning it will not be possible to say how well responses represent the target population.

Introduction

Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in children and adolescents, with an average worldwide prevalence of 5%.1 Up to 40% of young people with ADHD will continue to experience symptoms into adulthood,2 which can affect physical and mental health, further education, work, relationships, involvement with criminal justice and mortality, with ensuing economic impacts on the individual and society.1 3 A recent UK surveillance study estimated that the annual number of people aged 17–19 years with an ongoing need for ADHD medication lies between 270 and 599 per 100 000, with an even higher number requiring non-pharmacological support for their ADHD.4 Higher ADHD prevalence is associated with financial difficulties and economic disadvantage, resulting in higher service needs in some areas.5 The social and financial challenges of COVID-19 are likely to have intensified support needs, while also introducing new barriers to accessing health services. Treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of experiencing poorer outcomes in young people with ADHD.1 3 Withdrawal of treatment in young people can have particularly profound effects, as this is a vulnerable life stage, when multiple simultaneous transitions are occurring.6

ADHD service provision

For young people with ADHD who require ongoing support into adulthood, UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends a smooth transition into adult services, with the prescribing and monitoring of ADHD medication carried out under shared care protocol arrangements between primary and secondary care services.7 However, the Children and Adolescents with ADHD in Transition between Children’s and Adult Services study estimated that less than a quarter of young people who needed ADHD medication made the transition to adult mental health services.4 This is likely to be due to a combination of factors, including the availability and accessibility of adult ADHD services, which vary widely, and a lack of information on, and preparation for, transition.4 8–12 Even where medication is continued, management of ADHD may be suboptimal without access to specialist assessment of ADHD, advice on titration, or non-pharmacological support.13

The variation in services and support for young people (aged 16–25 years) with ADHD creates inequities in access and increases pressure on primary care.8–10 As a result, general practitioners (GPs) may end up providing care for young people with ADHD ‘by default’ due to long waiting times, a lack of adult services, or because a person does not meet service eligibility criteria,10–12; with some GPs reporting concerns about safety, risk and responsibility and workload.10 Variations in prescribing protocols and classification of ADHD drugs in local formularies,10 means some young people may also have difficulties registering with a GP willing to prescribe. Young people with ADHD have expressed a lack of confidence in primary care to help them manage their condition, and report frustration with the information provided by GPs and the support available.11 12 14 15

Primary care

Debates over how to tackle a ‘failure of healthcare’ for ADHD, especially at transition, often include an expanded role for primary care through recently established primary care networks (PCNs) of GP practices.6 16 NICE recommend further studies about the role of primary care in supporting young people discharged from children’s services.17 Challenges around shared care and guidance implementation have been recognised by working groups established by the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN), and National Health Service (NHS) England.6 There is currently no overview or map of the different models of care and roles that exist in primary care to support people with ADHD, though our own and others’ qualitative research has highlighted variations in prescribing practice and shared care models.16 NHS England’s mandate to strengthen primary care and reduce inequalities, needs to be met through consulting with patients and the public, and using the patient pathway approach.18 However, the current lack of national level data mapping pathways in primary care for young people with ADHD, is hindering efforts to optimise outcomes for this underserved group.

Coproduction

Coproduction which can be defined as ways of working that involve people using health services, carers, practitioners and the wider community, is increasingly seen as critical for research aiming to strengthen health and care systems.19 20 This rapidly evolving methodology within health and social care research, which is advocated and supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR19), is characterised by key principles of:

The sharing of power (so that research is jointly owned by those involved).

Including all perspectives and skills (so that all those who can contribute are included).

Respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working together (with equal importance).

The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health,21 called for development of evidence-based approaches to co-production in commissioning. The NHS Long Term Plan,22 also emphasises the importance of working collaboratively to find solutions to address unmet health and social care needs. Therefore, research aiming to provide evidence to tackle identified ‘failures’ in NHS healthcare provision for young people with ADHD needs to involve stakeholders who can contribute varied knowledge and experience throughout the research process.

Rationale

This research has been developed in response to identified gaps in the literature and existing services (as outlined above), and priorities highlighted by people with ADHD. The research team includes young people with ADHD whose input will help ensure the research is sensitive and relevant, an academic GP to ensure identified solutions are deliverable within primary care settings. Also, our research advisory groups (RAGs), made up of healthcare practitioners and young people with ADHD and their supporters.

Under the NHS Long Term plan,22 and NHS Mental Health Implementation plan,23 the recent formation of PCNs in combination with the establishment of NHS integrated care systems (ICSs) (partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up health and care services), represents an opportunity to establish new and effective working practices to enable consistent and accessible healthcare for all young people with ADHD. The NHS Community Mental Health Framework,24 also sets out a vision for how community services should modernise to offer joined-up-care for those with mental health needs, within ICSs. Recent guidance, stemming from professionals across primary, secondary, and tertiary care in the UK, has recommended the development of an ADHD specialism within primary care, as part of a roadmap for improving access to treatment.25 The evidence base outlined above, and current guidelines,7 highlight the key role primary care services have to play in the provision of healthcare for young people with ADHD, and the potential for supporting an expansion of this role. Not only are primary care practitioners, such as GPs, often the gatekeepers through the referral system to secondary care services, such as adult mental health and specialist ADHD services, but NICE guidelines recommend that they also provide healthcare support such as routine monitoring, and prescribing of medication under shared care agreements with secondary care services.7

Furthermore, primary care services have an increasing role to play in terms of providing mental health and well-being support to young people with ADHD, with additional roles such as mental health workers and social prescribing link workers funded through PCNs.26 However, the challenges for primary care in delivering co-ordinated and accessible healthcare for young people with ADHD, need to be better understood.

Currently, little is known about whether or how services are provided for young people aged 16–25 with ADHD in primary care in England, or about areas of good practice, and optimal models and pathways for improving access to healthcare for this underserved group. While the NHS Long Term Plan,22 aims to dissolve the historic divide between primary and secondary/specialist care, delivering healthcare across systems remains challenging. For example, existing evidence indicates that GPs can feel unsupported and uncertain about providing medication under shared care agreements.10 27

In line with current need, the aim of this research is therefore to map current services and provide an evidence-base to inform coproduced guidance to improve primary care for young people aged 16–25 years with ADHD. The objectives are to:

Develop a map and overview of current primary care pathways and prescribing practice in the management of young people with ADHD in England

-

Explore:

Primary care providers and related organisations’ needs for prescribing support in their roles managing care for young people with ADHD

The expectations and needs of young people regarding ADHD support, information and management in primary care

Coproduce evidence informed guidance to better co-ordinate primary care and improve accessibility for young people with ADHD, based on discussions around integrated findings from objectives 1 and 2.

Methods and analysis

Overview

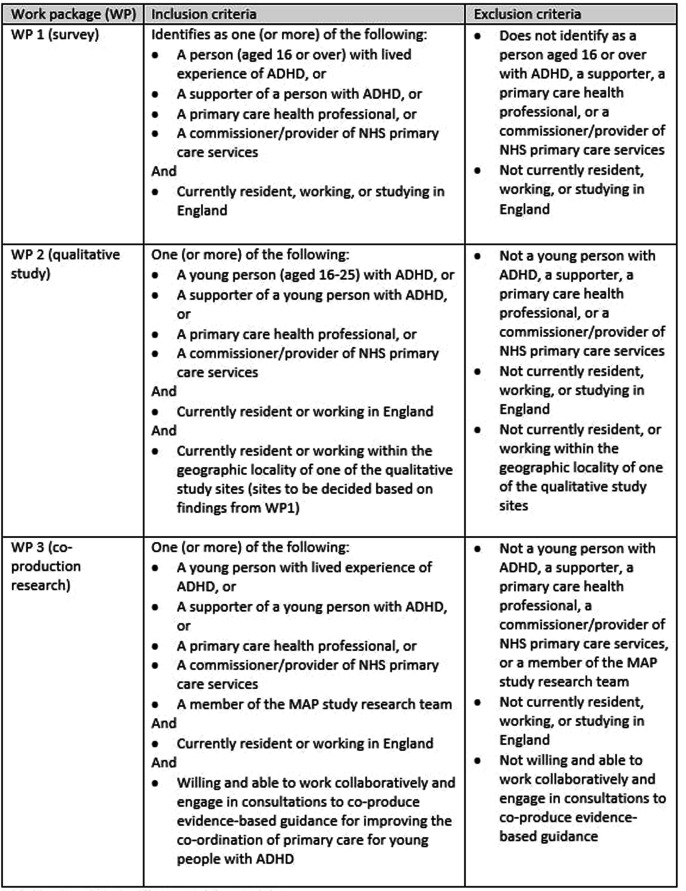

This mixed-methods study consists of three work packages to address the three objectives outlined above: a survey, qualitative interviews, and integration of findings to support coproduction of guidance. Participants in each will include people aged 16 or over with lived experience of ADHD (and their supporters), health professionals with a focus on primary care (such as GPs, nurses, mental health practitioners, and clinical pharmacists), and primary care commissioners/providers. Sampling, recruitment strategies, and eligibility criteria, vary slightly between work packages. For details of eligibility criteria by work package (WP), see figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant eligibility criteria, by work package. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; MAP study, Managing young people with ADHD in Primary care (MAP) study.

The research will be guided and informed throughout by 6 monthly meetings with two RAGs made up of a diverse mix of primary healthcare practitioners, and young people with ADHD and their parents/carers. These will be a practice and policy research advisory group (P-RAG), and a young person and parent/carer research advisory group (Y-RAG).

Named research partners will support delivery of the research, including advising on delivery of the research and dissemination of results. These include the ADHD Foundation, the UKAAN, NIHR Clinical Research Network South West Peninsula and Devon Partnership NHS Trust (DPT).

Work package 1 (WP1) survey

Design

A mapping study will involve an online survey of primary care provision for young people and adults with ADHD in England. Informants will be sampled from three key stakeholder groups—service users, healthcare professionals and commissioners/providers—via a mixture of convenience and purposive techniques. Due to the sampling methods, self-selection bias is likely, which is acknowledged within the study design and will be clearly discussed as a limitation in the write up of findings. Despite this limitation this sample is still expected to provide valuable data. The target sample size will be a minimum of 252 participants in total (providing a minimum of six responses for each ICS in England). The survey will be open for up to 16 weeks. Responses will be reviewed part-way through this period, with subsequent survey promotion and reminders targeted to achieve a balanced mix of responses by geographic location and stakeholder group. The survey will use the seven-step pragmatic health service mapping method, developed through extensive patient and public involvement28 and previously used to map adult mental health service availability for adults with ADHD in England in 2018.9

Participants

Participants located across England will be invited to participate via direct email, social media, partner organisation mailing lists, and organisation newsletters and websites. For eligibility criteria, see figure 1.

Data collection

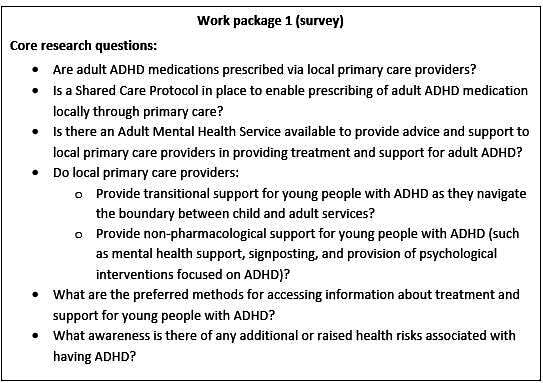

Data will be collected online via a certified GDPR compliant online survey tool; Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA. https://www.qualtrics.com). The survey will include demographic questions about the respondent’s role, location and any practice/organisation they are linked to, and core research questions (see figure 2) exploring current primary care practice in relation to NICE7 guidelines for diagnosis and management of ADHD. The survey will be designed (and programmed) so that respondents will be taken to different questions, depending on the stakeholder group that they primarily identify with. Final survey wording will be piloted and agreed in consultation with study RAGs.

Figure 2.

Work package 1 (survey), core research questions. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Analysis

Data will be analysed using Stata SE15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise respondent characteristics by geographic location and stakeholder group. A full data analysis and presentation plan will be developed and informed by discussions with study RAGs. Variation by stakeholder group and local area characteristics (eg, rural/urban, ethnic mix, socioeconomic status) will be summarised and tabulated by geographic unit. The unit size (eg, PCN, ICS, NHS region) used in each analysis will be dependent on the volume of available data, and whether an analysis at the stated level will provide meaningful information, following consultation with stakeholder groups. Where appropriate, data will be presented on a map of England using a geographic information system (QGIS 3.24), illustrating variation by region or other geographic unit on prescribing practice, shared care, specialist support, etc. Accessible visual tools, such as Google My Map, will be used to communicate findings with stakeholders.

Work package 2 (WP2) qualitative

Design

A qualitative study consisting of semi-structured interviews (or focus-groups) with a sample of 10–15 young people with ADHD and their supporters, and 10–15 primary care professionals/commissioners from a range of geographic locations in England. Interviews with professionals/commissioners are combined, due to resource limitations. Decisions on final sample makeup, and the structure of interviews vs focus groups will be made following WP1, and in consultation with the study RAGs. The number of locations (between three and six) and boundaries (eg, GP surgery, PCN or ICS) will be decided based on findings from WP1. Locations will be purposively chosen (informed by findings from WP1) to reflect a variety of local approaches to primary care practice for treatment and support of ADHD. These might for example include a GP surgery serving university students, or an urban surgery with a GP who has a special interest in mental health.

Participants

Participants will be purposely sampled to include of a diverse mix of young people with ADHD and their parent/carers, health professionals and commissioners/providers of NHS services for ADHD. For eligibility criteria, see figure 1.

Data collection

Data will be collected using semi-structured interviews/focus-groups that follow topic guides developed and refined in consultation with the RAGs (see online supplemental files 1 and 2). Topic guides will be iteratively adjusted and will contain similar prompts for interviews and focus groups. For health professionals, these will cover perspectives on their role in managing young people with ADHD, needs for support with prescribing and other aspects of management, the information they need in terms of format, content and timing, their awareness of existing information resources and their preferences regarding access to and use of information in their role. For young people, these will cover perspectives on their experiences of support from primary care, their expectations from primary care consultations and the information and signposting needed to access care. Topic guides will also cover the following content:

bmjopen-2022-068184supp001.pdf (61KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068184supp002.pdf (62.2KB, pdf)

Background on participant’s current ADHD/healthcare context.

-

Experiences of

Care and support for ADHD through primary care.

Support for wider mental and physical health need of people with ADHD through primary care.

Adjustments to help people with ADHD access primary care.

Experiences of primary care consultations.

Information and resources that might improve provision and accessibility of healthcare for young people with ADHD through primary care.

Interviews/focus-groups will be conducted using a variety of mediums (eg, online meetings, by telephone or face-to-face), depending on the needs and preferences of participants. This flexible approach draws on evidence that respondents’ experience of control and choice affects take up of studies.29 It is also designed to accommodate the communication preferences and needs of young people with ADHD and their supporters and takes account of the limited availability of healthcare professionals, thus maximising the inclusivity of the research. Where individual interviews are not feasible due to resource or time constraints (eg, from a busy primary care team), focus-groups will be conducted to collect data. Focus groups may also generate richer data in some circumstances, for example, when discussing care pathways potentially involving multiple roles.

Analysis

Data from WP2 will be managed in NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK), and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.30 31 A codebook approach will be used to structure findings and provide insights suitable for applied policy research.30 32 33 The research process will be informed by an acknowledgement of the researcher’s active role in knowledge production, and a recognition of the interpretive nature of data coding.30 The framework method,33–35 will be used to generate themes reflexively through a process of inductive and deductive analyses, and a combination of semantic and latent coding.36 The analysis will be underpinned by a critical realist perspective. This reflexive theoretical stance will highlight the context of the data, and the influence of researcher and stakeholder perspectives, providing a nuanced interpretation of meaning suitable to inform the coproduction of guidance (in WP3).

An understanding of the need for information resources and prescribing and healthcare support will be developed within a range of different geographical and socio-economic contexts, and different models of care.

Work package 3 (WP3) coproduction

Design

Coproduction methods consisting of a series of consultations, will be conducted in line with national standards for public involvement,37 and following national guidance on coproducing a research project.19 The outline design for WP3 will be refined through consultation with the RAGs, research partners, and shaped following integration of findings from WP1 and WP2 into emerging themes and priority areas. A flexible research design, informed by previously documented coproduction methods,38 will enable participants to coproduce guidance using available evidence, to improve primary care for young people with ADHD.

Participants

There will be between 6 and 16 participants, reflecting a diversity of roles and experience including young people with ADHD (and their parents/carers), health professionals and members of the research team. The number of participants will be kept small to enable flexible and interactive debate between participants. Participants will be recruited from study RAGs, WP1 and WP2, with the final recruitment strategy designed and agreed in consultation with study RAGs. For eligibility criteria, see figure 1.

Data collection

Data will be collected by means of between two and four workshops that build iteratively on each other; with additional discussion facilitated through meetings and emails. Workshops and meetings will be conducted using variety of mediums (eg, online meetings or face-to-face), depending on the needs and preferences of participants. WP3 will bring stakeholders together, providing space and time to consider and integrate evidence from WP1 and WP2, and to engage in discussions, refinement of ideas and prioritisation setting exercises. The aim will be to produce accessible outputs designed for communication with a variety of audiences (eg, health professionals, service users and service commissioners/providers). Possible outputs include:

A map of patient pathways for young people accessing ADHD treatment and support through primary care.

A geographic overview of primary care provision, including areas of good practice and gaps in accessible care.

Templates for information resources for primary care practitioners and young people, including a plan for further implementation.

Key messages for primary care practitioners and young people (eg, what information do practitioners need to prescribe and titrate, what questions do young people want answers to?).

Suggestions for innovative technology-supported solutions to assist healthcare providers and young people with addressing the challenges encountered when care spans primary and secondary care systems.

Throughout WP3, the research team will maintain written records that chronicle and record information about the research process. Researchers will keep reflective diaries, recording tensions, sticking points and what is working well.

Analysis

WP3 will involve design followed by trialling and iterative refinement of integrated findings and coproduced outputs. A record will be kept of participant feedback on outputs. Coproduced guidance will be checked by research team members who have not been directly involved in the analysis, and with members of the RAGs, who will be asked to provide feedback on the output to verify its validity and consult on suitable methods of dissemination. Participant approved final versions of guidance and information will be disseminated as part of Managing young people with ADHD in Primary care study findings, using a variety of formats.

Outcomes

The outcomes of this research will be shaped by close work with professionals and members of the community to ensure their relevance and utility. Anticipated outcomes include:

-

Overview of primary care provision for young people with ADHD across England, including:

Geographic map, showing variation in provision by NHS region or appropriate organisational boundaries.

-

Qualitative findings reflecting the perspectives of people involved in providing and in need of care, on the management of ADHD in primary care including:

Health professionals’ needs for prescribing support.

Young people with ADHD and their parent/carers’ needs for healthcare and support with self-management.

Coproduced guidance on how to better design and co-ordinate primary care for young people aged 16–25 years with ADHD.

Research outcomes will be communicated to a range of academic, clinical, and lay audiences via a range of mediums including peer reviewed academic publications, lay summaries, presentations at academic and organisational conferences, and via the study website.

Patient and public involvement

This proposal stemmed from requests made by participants in previous research39 for information about GPs who prescribe for ADHD. Meetings between members of the research team and young people with ADHD, including AS who is an expert by experience and part of the research team, helped shaped the study design.

Patient and public involvement in this research will be conducted in accordance with the NIHR National Standards for Public Involvement.20 It will follow a framework for involvement to include respect, support, transparency, responsiveness, fairness of opportunity and accountability. People and the community will be involved in all stages of this research.

Involvement and engagement of all stakeholders will be built into the culture of this research study and embedded in research processes through the following study structures:

Core research group: inclusion of a young person with ADHD and an academic GP

-

RAGs meeting regularly to shape research progress:

Y-RAG, made up of young people with ADHD and their parent/carers.

P-RAG made up of practitioners and service commissioners/providers.

Research partnerships: with service user and practitioners’ organisations such the UK ADHD Foundation and DPT.

Research design: use of coproduction methodology in WP3 to jointly generate guidance and outputs.

Data statement

A technical appendix and dataset will be available from the lead author on request. Data will be stored in accordance with Exeter University’s data storage policies. If agreed with the research team, qualitative data (from WP2 and WP3) will be deposited with the UK Data Service, for long-term preservation.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by the Yorkshire and the Humber—Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference: IRAS 313424). The study will be carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013), the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research (2020) and the general principles of Good Clinical Practice E6 (R2). The study has been adopted by the NIHR Clinical Research Network and has relevant local NHS research approvals. The trial is sponsored by the University of Exeter.

This research aims to answer a research question that is relevant and of importance to young people with ADHD, a currently underserved population in the UK. It is supported and informed by research advisors and partner organisations who represent the views and experiences of people with lived experience of ADHD, health professionals, and commissioners/providers. The collaborative research design will help to ensure that the research is conducted in a sensitive manner and will result in outputs that are appropriately communicated and useful.

Amendments

Sponsor SOPs are being followed for amendments. Please note, it is anticipated that versions of study documents (eg, consent forms) may be updated following planned stakeholder engagement activities. Where documents are amended, HRA guidance on amending an approval will be followed, and advice and approval of the study sponsor will be sought on whether changes quality as non-substantial or substantial amendments. In all cases, HRA processes will be followed, with documents updated in IRAS (using version control) and communicated to the REC (as appropriate).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who have contributed to this study, including the healthcare professionals, and people with ADHD and their supporters who have been involved in the conception and planning of this research. Also, the colleagues, collaborators and research partners that have supported every aspect of this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Anna_M_Price, @DrJaneRSmith, @farazhmughal

Contributors: The research idea was inspired by and developed with people with ADHD and their supporters. The original research design stemmed from development work conducted by AP and TN-D. All authors actively contributed to the research design. AP, TN-D and JS developed the protocol. AP leads the study, drafted the protocol ready for publication and wrote the ethics submission. TN-D, JS and GJM-T provide research oversight and academic mentorship. FM is an academic GP and leads on healthcare professional representation and provides primary care expertise. AS leads on patient and public involvement (PPI) representation. All authors commented on the protocol and the manuscript, provided final approval for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This project is funded by an NIHR Three School’s Mental Health Research Fellowship (MHF008). AP and research project activities are funded by this fellowship. The grant is administered by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research. The study sponsor has seen, approved, and signed off the protocol. This project is supported by the NIHR Clinical Research Network South West Peninsula. AP holds a Fellowship (award number MH008) funded by the Three NIHR Research Schools Mental Health Programme. FM is funded by a NIHR Doctoral Fellowship (NIHR300957) and is an affiliate of the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. This work was supported by the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (award number: PSTRC-2016-003). TN-D is funded by an NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR300056). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: AP, JS, FM, AS, GJM-T and TN-D have nothing to disclose.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Sayal K, Taylor E, Beecham J, et al. Pathways to care in children at risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:43–8. 10.1192/bjp.181.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 2006;36:159–65. 10.1017/S003329170500471X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med 2012;10:99. 10.1186/1741-7015-10-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T, et al. Transition between child and adult services for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): findings from a British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 2020;217:616–22. 10.1192/bjp.2019.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad V, West J, Kendrick D, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: variation by socioeconomic deprivation. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:802–5. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young S, Adamou M, Asherson P, et al. Recommendations for the transition of patients with ADHD from child to adult healthcare services: a consensus statement from the UK adult ADHD network. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:301. 10.1186/s12888-016-1013-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NICE . Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management (NG87). 2018. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/chapter/Recommendations [Accessed 29 Mar 2019].

- 8.Hall CL, Newell K, Taylor J, et al. Services for young people with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder transitioning from child to adult mental health services: a national survey of mental health trusts in England. J Psychopharmacol 2015;29:39–42. 10.1177/0269881114550353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price A, Janssens A, Newlove-Delgado T, et al. Mapping UK mental health services for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national survey with comparison of reporting between three Stakeholder groups. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e76. 10.1192/bjo.2020.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newlove-Delgado T, Blake S, Ford T, et al. Young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in transition from child to adult services: a qualitative study of the experiences of general practitioners in the UK. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:159. 10.1186/s12875-019-1046-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheson L, Asherson P, Wong ICK, et al. Adult ADHD patient experiences of impairment, service provision and clinical management in England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:184. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newlove-Delgado T, Ford TJ, Stein K, et al. You’re 18 now, goodbye’: the experiences of young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder of the transition from child to adult services. Emot Behav Diffic 2018;23:296–309. 10.1080/13632752.2018.1461476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coghill DR. Organisation of services for managing ADHD. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2017;26:453–8. 10.1017/S2045796016000937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French B, Sayal K, Daley D. Barriers and facilitators to understanding of ADHD in primary care: a mixed-method systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;28:1037–64. 10.1007/s00787-018-1256-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price A, Newlove-Delgado T, Eke H, et al. In transition with ADHD: the role of information, in facilitating or impeding young people's transition into adult services. BMC Psychiatry 2019;19:404. 10.1186/s12888-019-2284-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young S, Asherson P, Lloyd T, et al. Failure of healthcare provision for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United kingdom: a consensus statement. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:649399. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.649399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NICE . Transition from children’s to adults' services for young people using health or social care services (NG43). 2016. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43 [Accessed 03 Apr 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.NHS England . General practice forward view. 2016. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/general-practice-forward-view-gpfv [Accessed 03 Oct 2021].

- 19.NIHR . Guidance on co-producing a research project. 2021. Available: https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/?opportunity=nihr-guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project [Accessed 08 Mar 2022].

- 20.NIHR England . UK standards for public involvement. 2019. Available: https://sites.google.com/nihr.ac.uk/pi-standards/standards [Accessed 08 Mar 2022].

- 21.NHS England . Five year forward view. 2014. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-five-year-forward-view [Accessed 29 Mar 2019].

- 22.NHS England . The NHS long term plan. 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan [Accessed 26 Feb 2022].

- 23.NHS England . NHS mental health implementation plan. 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-mental-health-implementation-plan-2019-20-2023-24 [Accessed 26 Feb 2022].

- 24.NHS England . The community mental health framework for adults and older adults. 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/cmhs [Accessed 26 Feb 2022].

- 25.Asherson P, Leaver L, Adamou M, et al. Mainstreaming adult ADHD into primary care in the UK: guidance, practice, and best practice recommendations. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:640. 10.1186/s12888-022-04290-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naylor C, et al. Mental health and primary care networks: understanding the opportunities. The King’s Fund, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrington IM, McAloon J. Why shared-care arrangements for prescribing in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may not be accepted. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2018;25:222–4. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price A, Janssens A, Dunn-Morua S, et al. Seven steps to mapping health service provision: lessons learned from mapping services for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:468. 10.1186/s12913-019-4287-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catania JA, Binson D, Canchola J, et al. Effects of interviewer gender, interviewer choice, and item wording on responses to questions concerning sexual behavior. Public Opin Q 1996;60:345. 10.1086/297758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc 2019;11:589–97. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith J, Firth J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse Res 2011;18:52–62. 10.7748/nr2011.01.18.2.52.c8284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G. Designing and selecting samples. London: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritchie J, Spencer L. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, eds. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research, in Analyzing Qualitative Data. New York: Routledge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byrne D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant 2021;56:1391–412. 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.HRA . HRA approval in primary care settings – principles of study set-up. 2017. Available: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/nhs-site-set-up-in-england [Accessed 08 Mar 2022].

- 38.Evans BA, Porter A, Snooks H, et al. A co-produced method to involve service users in research: the SUCCESS model. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:34. 10.1186/s12874-019-0671-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janssens A, Eke H, Price A, et al. The transition from children’s services to adult services for young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the CATCh-uS mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2020;8:1–154. 10.3310/hsdr08420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-068184supp001.pdf (61KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068184supp002.pdf (62.2KB, pdf)