Abstract

Objective

To describe the comorbidities in children with cerebral palsy (CP) and determine the characteristics associated with different impairments.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Tertiary care referral centre in India.

Patients

Between April 2018 and May 2022, all children aged 2–18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of CP were enrolled by systematic random sampling. Data on antenatal, birth and postnatal risk factors, clinical evaluation and investigations (neuroimaging and genetic/metabolic workup) were recorded.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of the co-occurring impairments was determined using clinical evaluation or investigations as indicated.

Results

Of the 436 children screened, 384 participated (spastic CP=214 (55.7%) (spastic hemiplegic=52 (13.5%); spastic diplegia=70 (18.2%); spastic quadriplegia=92 (24%)), dyskinetic CP=58 (15.1%) and mixed CP=110 (28.6%)). A primary antenatal/perinatal/neonatal and postneonatal risk factor was identified in 32 (8.3%), 320 (83.3%) and 26 (6.8%) patients, respectively. Prevalent comorbidities (the test used) included visual impairment (clinical assessment and visual evoked potential)=357/383(93.2%), hearing impairment (brainstem-evoked response audiometry)=113 (30%), no understanding of any communication (MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory)=137 (36%), cognitive impairment (Vineland scale of social maturity)=341 (88.8%), severe gastrointestinal dysfunction (clinical evaluation/interview)=90 (23%), significant pain (non-communicating children’s pain checklist)=230 (60%), epilepsy=245 (64%), drug-resistant epilepsy=163 (42.4%), sleep impairment (Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire)=176/290(60.7%) and behavioural abnormalities (Childhood behaviour checklist)=165 (43%). Overall, hemiparetic and diplegic CP and Gross Motor Function Classification System ≤3 were predictive of lesser co-occurring impairment.

Conclusion

CP children have a high burden of comorbidities, which increase with increasing functional impairment. This calls for urgent actions to prioritise opportunities to prevent risk factors associated with CP and organise existing resources to identify and manage co-occurring impairments.

Trial registration number

CTRI/2018/07/014819.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Chronic Pain, SLEEP MEDICINE

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

The main limitation is that this is a hospital-based, single-centre study.

Possibility of referral bias as children were enrolled at a tertiary care referral centre.

Biggest strength of the study is the comprehensive evaluation of multiple comorbidities which children with cerebral palsy can have.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a significant cause of childhood disability, currently estimated to affect approximately 2–4 per 1000 children.1–4 The disabilities in CP include not only motor dysfunction and associated functional limitations but also multiple additional disorders of cerebral functioning.5 These comorbidities reflect brain injury, which may vary based on the underlying aetiology and brain development.6

The aetiological spectrum of CP in low–middle-income countries (LMIC) is dominated by well-characterised and modifiable factors like hypoxia-ischaemia, prenatal infections, neonatal hypoglycaemia and hyperbilirubinemia.7 In contrast, several high-income countries (HIC) have reported transitioning from the causes mentioned above to prematurity, genetic factors and ‘unknown pathophysiologic processes’.7 8 Thus, the nature of the CP subtype, the comorbidities associated with them and the associated functional limitations are likely to be different in children with CP in LMICs compared with the HICs. According to Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe, the most common comorbidities are speech and language impairments (71%), intellectual impairment (62%), epilepsy (39%) and visual impairment (22%).9 However, studies exploring multiple CP-related comorbidities concurrently are scarce from the LMICs.

Definitive information about the extent of co-occurring impairments, diseases and functional limitations with CP is essential for healthcare providers to identify and allocate adequate resources for addressing them and for parents to choose services. Therefore, this study was undertaken to describe the comorbidities in children with CP and determine the CP characteristics associated with different comorbidities.

Methodology

Patients

This cross-sectional observational study was undertaken in the Pediatric department of Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, India, between April 2018 and May 2022. CP was defined as a group of disorders causing permanent impairment of voluntary movement or posture attributed to non-progressive disturbances occurring in the developing fetal or infant brain.10 All children aged 2–18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of CP, of either gender, attending the Pediatric outpatient clinics were eligible for inclusion in the study. Children were recruited after the age of 2 years when the diagnosis of CP can be firmly substantiated. Children with transient motor disabilities, motor disabilities due to meningomyelocele or other spinal cord lesions, isolated hypotonia, motor abnormalities solely due to mental deficiency and neurodegenerative disorders were excluded from the study.

Data collection

All children underwent a detailed review of their medical records, and data on the child’s age, demography, antenatal, birth and postnatal details were chronicled. Hospital obstetric notes were sought to confirm the birth data given by parents and to collect extra information on the birth and neonatal period. The results of genetic and metabolic investigations, when performed, were recorded. Every child underwent a physical assessment detailing the anthropometry and neurological examination, including tonal assessments. The clinical evaluation was performed by investigators (MV, RJ and AK) and validated by other lead clinicians (KMA, SB and VS). The discrepancies were resolved by a repeat independent clinical evaluation by any two clinicians uninvolved with the primary evaluation. MRI scans done after 18 months were studied, and details were recorded. If the clinical details and/or neuroimaging were suggestive of an underlying genetic aetiology, then the parents were offered chromosomal microarray/next-generation sequencing for identifying underlying genetic mutations based on the clinical phenotype.

Based on the assessment, the child was subclassified into spastic CP (hemiparetic, diplegic, quadriplegic), dyskinetic CP and mixed CP.11 12 After detailed clinical evaluation, the children who could not be classified into any of these subtypes were labelled ‘unclassifiable’.

The assessment of comorbidities has been summarised in table 1 and included assessment of functional status,13 vision, hearing, cognition, comprehension and communication,14 15 behaviour,16 epilepsy,17 sleep,18 19 pain15 and gastrointestinal dysfunction. The analysis of gastrointestinal dysfunction was modelled on the previous work by Erkin and colleagues.20 Gastrointestinal dysfunction, difficulty in biting off food, insufficient chewing, dental disorders, lack of appetite, sialorrhea, vomiting, regurgitation, abdominal pain, swallowing difficulty, coughing during feeding and nasal regurgitation were documented. Bowel frequency was recorded as defecation of greater than 3/week, 1–3/week and less than 1/week; a defecation frequency of <3 times/week was considered constipation. A history of recurrent pulmonary aspiration, bronchopneumonia or wheezing during the past year was also documented. The amount of time the caregiver allocated to mealtimes was recorded in minutes per day. A categorical scale was used to classify each child’s current level of feeding dysfunction as follows: ‘normal (no dysfunction detected)’, eats normal diet (age-appropriate table foods) with no apparent feeding problems; ‘mild dysfunction’, mild swallowing or feeding difficulty, requires chopped or mashed food; ‘moderate dysfunction’, moderate swallowing or feeding difficulty, some difficulty with liquids, requires well-moistened, mashed or chopped food; ‘severe dysfunction’, severe difficulties in consuming liquids and solids, requires well-moistened solid foods, thickened fluids or tube feeding.20 All parents were also interviewed about whether their child is undergoing physiotherapy or occupational therapy and the frequency of these therapy sessions.

Table 1.

Summary of instruments/mechanisms used for of assessment of children with cerebral palsy

| Impairment assessed | Mechanism/instrument applied | Interpretation |

| Functional status | Gross Motor Function Classification System- Expanded & Revised13 | Levels 1 to 5 |

| Visual assessment | Clinical evaluation (for strabismus, refractive errors, and fundus abnormalities) followed by a recording of visual evoked potentials | Presence or absence of visual impairment |

| Hearing assessment | Brainstem-evoked response audiometry | Presence or absence of hearing impairment |

| Cognitive assessment | Vineland Social Maturity Scale | SQ, thus obtained, was categorised into: |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Communication assessment | MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory14 15 | Comprehension component subdivided into: |

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Communication element subdivided into: | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Behavioural problems | Childhood Behavior Check List16 | Score ≥84th centile were defined as high for internalising, externalising and total problem scales |

| Epilepsy | Clinical evaluation17 | Presence or absence of epilepsy, drug resistant epilepsy, and epileptic encephalopathy |

| Sleep problems | Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire18 19 | Score >41 was used to define sleep disorder |

| Pain | Non-communicating children’s pain checklist15 | Score ≥7 was indicative of pain |

| Gastrointestinal dysfunction | Parental interview20 | Categorical scale was used to define degree of dysfunction |

Sample size

The prevalence of the comorbidities associated with CP varies from 20% to 75%.5 Based on these proportions, with a 95% CI and 10% absolute error margin, the maximum sample size was calculated as 96. The study was initiated in April 2018 with a sample size of 96. However, after that, the sample size was recalculated as 384, considering a 95% CI and 5% confidence limits and 50% prevalence of comorbidity.

Statistical methods

All data were analysed using R V.4.1.2. The baseline data were assessed for normality, and the continuous data were summarised using mean and SD or median and IQR as applicable. The categorical data have been presented as proportions. The data were stratified based on the type of CP into dyskinetic, hemiparetic, mixed, spastic diplegia, spastic quadriplegia and unknown. Proportion of children with CP with each of the aforementioned comorbidities was calculated and depicted as a percentage.

Role of funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient and public involvement

The research question and outcome measures were developed based on patients’ priorities, experience and preferences. Patients and the public were sensitised about the research via local meetings and were involved in the research’s design, conduct and reporting. The study results will be disseminated to study participants through social media.

Results

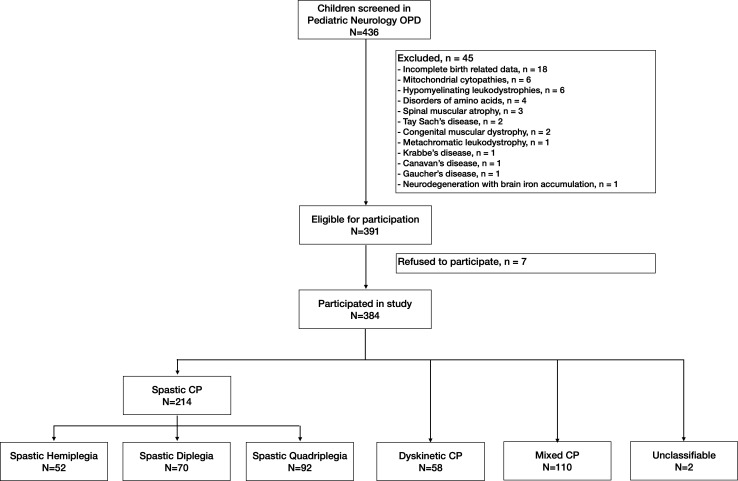

Of the 436 children screened, 384 were eligible children with CP participated in the study (figure 1). Among the 384 children with CP, 214 (55.7%) had spastic CP (hemiplegic=52 (13.5%), diplegic=70 (18.2%), quadriplegic=92 (23.9%)), 58 (15.1%) had dyskinetic CP, and 110 (28.6%) had mixed CP. Two patients were unclassifiable, and no child was diagnosed with ataxic CP.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients. CP, cerebral palsy.

The characteristics and background factors of the study group and each subtype of CP have been described in table 1. The mean (SD) age of the study group was 78 (38) months, with a mean (SD) gestational age at birth being 37 (4) weeks. Overall, 231 (60.2%) children were born term, while 97 (25.3%), 48 (12.5%) and 8 (2.1%) were born moderate to late preterm, very preterm and extremely preterm, respectively. The study group’s mean (SD) birth weight was 2343 (796) g.

The risk factors for the occurrence of CP were identified in 378 (98.4%) children. A primary antenatal risk factor was identified in 32 (8.3%) children and included an inherited genetic aetiology in 23 patients (polymicrogyria (n=9), lissencephaly (n=5), holoprosencephaly (n=3), schizencephaly (n=3), IQSEC2 variant (n=2), ASXL3 variant (n=1) and septo-optic dysplasia (n=1)), and an acquired intrauterine infection in nine patients (congenital cytomegalovirus infection (n=5), congenital rubella infection (n=3), congenital toxoplasmosis (n=1)). Of 320 of 384 (83.3%) patients had an identifiable risk factor in the perinatal or neonatal period. These included neonatal hypoglycaemia (n=102, 26.6%), perinatal asphyxia (n=90, 23.4%), prematurity (n=81, 21.1%), neonatal sepsis (n=74, 19.3%), neonatal jaundice (n=24, 6.3%), perinatal stroke (n=23, 6%) and birth trauma (17, 4.4%). Twenty-six of 384 (6.8%) children had a brain injury after the neonatal period. These included febrile encephalopathy including infective meningoencephalitis (n=13), surgery-related hypoxia (n=11), traumatic brain injury (n=2) and near drowning (n=1). No aetiological factor could be identified in six children (1.6%) with CP.

Functionally, 30/384 (7.8%) children were in Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level I. The GMFCS levels II, III, IV and V included 59 (15.4%), 56 (14.6%), 65 (16.9%) and 174 (45.3%) patients, respectively. There were 45 (86.5%) children in GMFCS level I or II among patients with hemiparetic CP as compared with 38 (54.3%), 2 (3.4%), 2 (2.2%) and 2 (1.8%) in children with spastic diplegia, dyskinetic CP, spastic quadriplegia and mixed CP (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and background factors

| Characteristic | Overall, N=384*† |

Spastic CP N=214 |

Dyskinetic CP, N=58* |

Mixed CP, N=110* |

||

| Spastic haemiplegia, N=52* |

Spastic diplegia, N=70* |

Spastic quadriplegia, N=92* |

||||

| Age, months | 78 (38) | 72 (41) | 66 (27) | 77 (41) | 93 (42) | 82 (37) |

| Male | 251 (65%) | 36 (69%) | 30 (43%) | 56 (61%) | 50 (86%) | 77 (70%) |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37 (4) | 37 (4) | 33 (3) | 38 (3) | 38 (3) | 38 (2) |

| Term | 231 (60%) | 32 (62%) | 7 (10%) | 66 (72%) | 43 (74%) | 81 (74%) |

| Moderate to late preterm | 97 (25%) | 11 (21%) | 29 (41%) | 19 (21%) | 13 (22%) | 25 (23%) |

| Very preterm | 48 (13%) | 7 (13%) | 31 (44%) | 5 (5.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Extremely preterm | 8 (2.1%) | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal | 241 (63%) | 39 (75%) | 49 (70%) | 58 (63%) | 36 (62%) | 58 (53%) |

| LSCS | 130 (34%) | 13 (25%) | 21 (30%) | 28 (30%) | 21 (36%) | 46 (42%) |

| Instrumental | 13 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 6 (5.5%) |

| Birth weight, grams | 2343 (796) | 2300 (880) | 1451 (439) | 2548 (752) | 2715 (709) | 2563 (582) |

| Aetiology/risk factors | ||||||

| Antenatal factors | 32 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 9‡ |

| Genetic | 23 (6.0%) | 10 (19%) | 1 (1.4%) | 7 (7.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Intrauterine infections | 9 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (5.5%) |

| Birth related factors | 320 | 40 | 66 | 74 | 58 | 82 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 102 (26.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (45%) | 0 (0%) | 61 (55%) |

| Perinatal asphyxia | 90 (23.4%) | 7 (13%) | 7 (10%) | 27 (29%) | 35 (60%) | 14 (13%) |

| Prematurity | 81 (21.1%) | 11 (21%) | 59 (84%) | 6 (6.5%) | 2 (3.4%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Neonatal sepsis | 74 (19.3%) | 0 | 10 | 22 | 7 | 35 |

| Neonatal jaundice | 24 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (36%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Perinatal stroke | 23 (6.0%) | 22 (42%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Birth trauma | 17 (4.4%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 9 (9.8%) | 4 (6.9%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Etiological factors after neonatal period | 26 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 17 |

| Febrile encephalopathy | 13 (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Surgery related hypoxia | 11 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (6.4%) |

| Traumatic brain injury/drowning | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 6 (1.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Functional status: GMFCS levels | ||||||

| 1 | 30 (7.8%) | 27 (51.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2 | 59 (15.4%) | 18 (34.6%) | 35 (50%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| 3 | 56 (14.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 29 (41.4%) | 5 (5.4%) | 11 (19%) | 9 (8.2%) |

| 4 | 65 (16.9%) | 5 (9.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | 13 (14.1%) | 19 (32.8%) | 24 (21.8%) |

| 5 | 174 (45.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 72 (78.3%) | 26 (44.8%) | 75 (68.2%) |

One patient with intrauterine infection also had neonatal sepsis and later developed mixed CP.

‡One patient with intrauterine infection also had neonatal sepsis and later developed mixed CP

*Mean (SD); n (%).

†Two patients from the cohort could not be classified into any of sub-categories.

CP, cerebral palsy; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; LSCS, lower segment caesarean section.

Primary outcome

The details of the proportion of children with each of the comorbidities have been described in figure 2 and online supplemental tables 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

The comorbidities of each patient are shown; each radial segment represents one patient, and each circumferential track represents one comorbidity. The patients with different comorbidities have an appropriately coloured cell, while the patients with absence of comorbidity have a blank cell in the track. The comorbidities have been depicted separately for each of the topographical sub-types of cerebral palsy patients.

bmjopen-2023-072365supp001.pdf (173.5KB, pdf)

Visual and hearing impairment

Visual impairment was identified in 357 of 383 (93.2%) patients, with 293 having abnormal fundus examination, 248 having abnormal waveforms on visual evoked potentials, 246 having impaired visual acuity, 150 having squint and 94 having a refractive error. Hearing impairment was noted in 113 (29.5%) children, with 62.1% of children with dyskinetic CP having a hearing impairment.

Cognitive impairment

Cognitive assessment revealed a mean (SD) social quotient (SQ) of 31.5 (29.2) for the study cohort. Overall, 43 (11.2%) children had normal SQ. The SQ was normal in 23 (44.2%), 15 (21.7%), 3 (5.2%), 1 (0.9%) and 1 (1.1%) children with spastic hemiplegia, spastic diplegia, dyskinetic CP, mixed CP and spastic quadriplegia, respectively.

Language impairment

In the language-related comorbidities, 137 (35.7%) children had no understanding of any communication, while 178 (46.4%) children could not do any gestural communication.

Behavioural impairment

Behavioural comorbidities were noted in 165/384 (43%) children, with 132 (34.4%) and 70 (18.2%) children demonstrating internalising and externalising behaviours.

Epilepsy

Of 245 (63.8%) patients had epilepsy, of which 163 had drug-resistant epilepsy. The prevalence of epilepsy in different CP subtypes included spastic quadriplegia=81 (88%), mixed CP=88 (80%), dyskinetic CP=27 (46.6%), hemiparetic CP=24 (46.2%) and spastic diplegia=24 (34.3%).

Sleep impairment

Sleep impairment was detected in 176/290 (60.7%) children, with predominant sleep-related impairments being sleep onset delay (126, 43.4%), daytime sleepiness (106, 36.6%), night waking (106, 36.6%), impaired sleep duration (102, 35.2%) and sleep-disordered breathing (80, 27.6%).

Pain

Eighty-eight (80%) patients with mixed CP and 72 (78.3%) patients with spastic quadriplegia had significant pain, while the same in dyskinetic CP, spastic quadriplegia and hemiplegic CP were present in 37 (63.8%), 22 (31.4%) and 9 (17.3%) patients.

Gastrointestinal dysfunction

The mean (SD) mealtime, per meal, for the study group, was 37.8 (18.1) min, with children with hemiparetic CP, spastic diplegia, dyskinetic CP, mixed CP and spastic quadriplegia having a mean (SD) mealtime of 25.5 (10.4), 34.9 (12), 39.5 (20.4), 39.2 (20.1) and 43.6 (17.4) minutes per meal, respectively. Overall, 296 (77.1%) children had gastrointestinal dysfunction. The gastrointestinal dysfunction was severe in 90 (23.4%) children, with 37 (33.6%), 31 (33.7%), 20 (34.5%) and 1 (1.9%) patient(s) of mixed CP, spastic quadriplegia, dyskinetic CP and hemiplegic CP having severe gastrointestinal dysfunction respectively.

Rehabilitation

Overall, 59/384 (15.4%) children were attending rehabilitative programme activities including center-based physiotherapy/occupational therapy (55/384, 14.3%), speech therapy (14/384, 3.6%) and behaviour therapy (8/384, 2.1%). The details have been illustrated in online supplemental table 2.

Discussion

This hospital-based study characterised multiple comorbidities among the 384 children with CP. This is among the few studies that have studied multiple CP-related coimpairments, and the salient observations are summarised below.

First, nearly two of every three children in the study had a severe type of CP (mixed=28.6%, spastic quadriplegia=24% and dyskinetic CP=15.1%). The findings of a higher proportion of these severe forms of CP is similar to other hospital-based studies from Africa, Vietnam, Nepal, a 10-year series from Canada and a population-based surveillance study from Bangladesh.3 21–27 However, our findings differ from another similar study from Turkey that reported larger numbers of milder forms, especially spastic diplegia.28 These discordances can be accounted by differences in the underlying aetiological factors. Sixty per cent of children in our study were born term, 25% were born moderate to late preterm and 15% were very or extremely premature. The profile of gestational age at birth is similar to some of the reports from LMICs and HICs. Despite a concordant gestational age at birth, the higher percentage of severe cases of CP in our research can be attributed to the birth and perinatal complications such as hypoglycaemia (102/384; 26.6%), hypoxia (90/384; 23.4%) and bilirubin encephalopathy (24/384; 6.3%), which were the leading causes of CP in our cohort. Another possible explanation is that there may be disparities in accessing healthcare. The parents of children who are less severely affected may not seek healthcare for their children, leading to their under-representation in our cohort.

Second, we demonstrate that 239 of 384 (62.2%) of all CP children had a GMFCS level of ≥4, indicating significant limitations in two of three children. Severe GMFCS levels were more frequent in children with spastic quadriplegia, mixed CP and dyskinetic CP. Our data demonstrate a correlation between the type of CP and the functional abilities of patients, and this finding is consistent with previous reports on this.26 29

Third, our data demonstrate that among children who have CP: 2 in 3 could not walk, 9 in 10 had some visual impairment (2 in 10 were blind), 1 in 3 had hearing impairment, 8 in 10 had an intellectual disability, 1 in 3 had no understanding of communication, 1 in 2 had no communication (gestural/verbal), 4 in 10 had behavioural abnormalities, 2 in 3 had epilepsy, 6 in 10 had sleep impairments, 6 in 10 were in pain, 6 in 10 had persistent drooling and 1 in 4 had severe gastrointestinal dysfunction. While there is a paucity of studies assessing multiple comorbidities in the same cohort, the rates of co-occurring impairments were higher in our study group than reported earlier.5 6 11 16 20 30–34 The same is possibly related to the selection bias in our patients and the underlying aetiology of CP and related brain damage.

Finally, only one in seven children were receiving physiotherapy, and the proportion for other rehabilitative measures was still lesser. Overall, the proportion of children receiving supportive management was less than desirable. The same can be due to multiple factors, including inadequate public awareness, socioeconomic factors or lack of adequate human resources to provide physiotherapy.

Our study has some limitations. First, we included children aged 2–18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of CP. The clinical characteristics in these children tend to change, with spastic and dyskinetic features becoming more apparent over time.35 Hence, many registering programmes have established an age of 5 years to firmly substantiate a diagnosis of CP.35 36 Second, this study used Vineland Scale of Social Maturity (VSMS) to evaluate SQ for the enrolled population. VSMS evaluates only adaptive functioning, while intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits should be present to diagnose intellectual disability. Hence, VSMS may not be a true measure of intellectual disability in this population. Third, though we attempted to cover multiple comorbidities, we missed some significant behavioural impairments, including autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Finally, this is a hospital-based, single-centre, study with an inherent referral bias. The study tends to over-represent more severe disabilities and under-represent people who did not seek care for various reasons (participation bias). These limitations make it difficult to generalise our results to a total population of children with CP. However, the common argument that hospital data may under-represent the mild forms is also possibly the fundamental strength of our study. The awareness of the proportion of children with more severe disabilities will aid clinicians in actively looking for these coexistent conditions and will contribute to the optimal utilisation of available healthcare resources. In addition, the identified aetiologies of CP will help bridge the gap(s) in neonatal care.

To conclude, children with CP can have multiple co-occurring impairments (neurological, psychological, behavioural and medical), which involve management strategies beyond tone management. While scientific advances continue to define the complexities underlying the aetiology of CP, reducing the burden of coexistent disabilities is imperative. The first step towards the same is by actively asking for the same in clinical evaluations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the healthcare staff who contributed to facilitation of the study at various levels. We are immensely grateful to the children and their caregivers who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @vishal_sondhi

Contributors: RJ, BMJ and VS were responsible for conceptualisation and design. MV, RJ, AK, ADG, SK, PP and UBK collected the data. KMA, SB and VS validated the data. RJ and VS were responsible for data analysis. RJ, AK, KMA, BMJ and VS were responsible for data interpretation. RJ wrote the initial draft. RJ, BMJ, KMA and VS were responsible for writing, review and editing. MV, RJ, ADG, AK, SB, SK, PP, BMJ, KMA, UBK, VS approved the final manuscript. VS is the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data generated in this study will be available as de-identified data on Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com). Requests for clinical data should be emailed to the corresponding author and should include a brief description of the proposed analysis. Requests for data access will be reviewed individually, and a decision will be communicated.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of Armed Forces medical College, Pune Approval number: IEC/2018/10. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Chauhan A, Singh M, Jaiswal N, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy in Indian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Pediatr 2019;86:1124–30. 10.1007/s12098-019-03024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre S, Goldsmith S, Webb A, et al. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2022;64:1494–506. 10.1111/dmcn.15346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khandaker G, Muhit M, Karim T, et al. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in Bangladesh: a population-based surveillance study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:601–9. 10.1111/dmcn.14013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahan I, Muhit M, Hardianto D, et al. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in low- and middle-income countries: preliminary findings from an international multi-centre cerebral palsy register. Dev Med Child Neurol 2021;63:1327–36. 10.1111/dmcn.14926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak I, Hines M, Goldsmith S, et al. Clinical prognostic messages from a systematic review on cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1285–312. 10.1542/peds.2012-0924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aisen ML, Kerkovich D, Mast J, et al. Cerebral palsy: clinical care and neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:844–52. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70176-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahey MC, Maclennan AH, Kretzschmar D, et al. The genetic basis of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:462–9. 10.1111/dmcn.13363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costeff H. Estimated frequency of genetic and nongenetic causes of congenital idiopathic cerebral palsy in West Sweden. Ann Hum Genet 2004;68:515–20. 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prevalence and characteristics of children with cerebral palsy in Europe. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;44:633–40. 10.1017/S0012162201001633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grether JK, Cummins SK, Nelson KB. The California cerebral palsy project. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1992;6:339–51. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1992.tb00774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulati S, Sondhi V. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Indian J Pediatr 2018;85:1006–16. 10.1007/s12098-017-2475-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, et al. Content validity of the expanded and revised gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:744–50. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heilmann J, Ellis Weismer S, Evans J, et al. Utility of the MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventory in identifying language abilities of late-talking and typically developing toddlers. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2005;14:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrath PJ, Rosmus C, Canfield C, et al. Behaviours caregivers use to determine pain in non-verbal, cognitively impaired individuals. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigurdardottir S, Indredavik MS, Eiriksdottir A, et al. Behavioural and emotional symptoms of preschool children with cerebral palsy: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010;52:1056–61. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Definition of refractory epilepsy: defining the indefinable Lancet Neurol 2010;9:27–9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70304-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markovich AN, Gendron MA, Corkum PV. Validating the children’s sleep habits questionnaire against polysomnography and actigraphy in school-aged children. Front Psychiatry 2014;5:188. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000;23:1043–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erkin G, Culha C, Ozel S, et al. Feeding and gastrointestinal problems in children with cerebral palsy. Int J Rehabil Res 2010;33:218–24. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283375e10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karumuna JM, Mgone CS. Cerebral palsy in Dar Es Salaam. Cent Afr J Med 1990;36:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belonwu RO, Gwarzo GD, Adeleke SI. Cerebral palsy in Kano, Nigeria--a review. Niger J Med 2009;18:186–9. 10.4314/njm.v18i2.45062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Toorn R, Laughton B, Van Zyl N, et al. Aetiology of cerebral palsy in children presenting at Tygerberg Hospital. S Afr J Child Health 2007;1:74–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singhi P, Saini AG. Changes in the clinical spectrum of cerebral palsy over two decades in North India--an analysis of 1212 cases. J Trop Pediatr 2013;59:434–40. 10.1093/tropej/fmt035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Morin I. Etiologic yield of cerebral palsy: a contemporary case series. Pediatr Neurol 2003;28:352–9. 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00006-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakooza-Mwesige A, Forssberg H, Eliasson AC, et al. Cerebral palsy in children in Kampala, Uganda: clinical subtypes, motor function and co-morbidities. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:166. 10.1186/s13104-015-1125-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karim T, Dossetor R, Huong Giang NT, et al. Data on cerebral palsy in Vietnam will inform clinical practice and policy in low and middle-income countries. Disabil Rehabil 2022;44:3081–8. 10.1080/09638288.2020.1854872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erkin G, Delialioglu SU, Ozel S, et al. Risk factors and clinical profiles in Turkish children with cerebral palsy: analysis of 625 cases. Int J Rehabil Res 2008;31:89–91. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3282f45225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shevell MI, Dagenais L, Hall N, et al. Comorbidities in cerebral palsy and their relationship to neurologic subtype and GMFCS level. Neurology 2009;72:2090–6. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aa537b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhary S, Bhatta NK, Poudel P, et al. Profile of children with cerebral palsy at a tertiary hospital in Eastern Nepal. BMC Pediatr 2022;22:415. 10.1186/s12887-022-03477-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabis LV, Tsubary NM, Leon O, et al. Assessment of abilities and comorbidities in children with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol 2015;30:1640–5. 10.1177/0883073815576792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadden KL, von Baeyer CL. Pain in children with cerebral palsy: common triggers and expressive behaviors. Pain 2002;99:281–8. 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00123-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pruitt DW, Tsai T. Common medical comorbidities associated with cerebral palsy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2009;20:453–67. 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollung SJ, Bakken IJ, Vik T, et al. Comorbidities in cerebral palsy: a patient registry study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020;62:97–103. 10.1111/dmcn.14307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smithers-Sheedy H, Badawi N, Blair E, et al. What constitutes cerebral palsy in the twenty-first century? Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:323–8. 10.1111/dmcn.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadowska M, Sarecka-Hujar B, Kopyta I. Cerebral palsy: current opinions on definition, epidemiology, risk factors, classification and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2020;16:1505–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-072365supp001.pdf (173.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data generated in this study will be available as de-identified data on Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com). Requests for clinical data should be emailed to the corresponding author and should include a brief description of the proposed analysis. Requests for data access will be reviewed individually, and a decision will be communicated.