Abstract

Class B1 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), collectively, respond to a diverse repertoire of extracellular polypeptide agonists and transmit the encoded messages to cytosolic partners. To fulfill these tasks, these highly mobile receptors must interconvert among conformational states in response to agonists. We recently showed that conformational mobility in polypeptide agonists themselves plays a role in activation of one class B1 GPCR, the receptor for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Exchange between helical and non-helical conformations near the N-termini of agonists bound to the GLP-1R was revealed to be critical for receptor activation. Here, we ask whether agonist conformational mobility plays a role in the activation of a related receptor, the GLP-2R. Using variants of the hormone GLP-2 and the designed clinical agonist glepaglutide (GLE), we find that the GLP-2R is quite tolerant of variations in α-helical propensity near the agonist N-terminus, which contrasts with signaling at the GLP-1R. A fully α-helical conformation of the bound agonist may be sufficient for GLP-2R signal transduction. GLE is a GLP-2R/GLP-1R dual agonist, and the GLE system therefore enables direct comparison of the responses of these two GPCRs to a single set of agonist variants. This comparison supports the conclusion that the GLP-1R and GLP-2R differ in their response to variations in helical propensity near the agonist N-terminus. The data offer a basis for development of new hormone analogues with distinctive and potentially useful activity profiles; for example, one of the GLE analogues is a potent agonist of the GLP-2R but also a potent antagonist of the GLP-1R, a novel form of polypharmacology.

Introduction

Signal transduction via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is a dynamic process. The agonist engages external receptor surfaces, and cellular responses are mediated by cytosolic proteins (including G proteins, β-arrestins and GPCR kinases) that contact internal receptor surfaces. Thus, the information encoded by the agonist is transmitted via changes induced in GPCR conformation that are sensed by cytosolic partners.1,2 Recent evidence suggests that dynamic motions within the agonist-bound state may be important for signaling through at least some GPCRs, although evidence for these dynamic features may be missing from crystal or cryo-EM structures.2-8 For example, multiple cryo-EM structures of the receptor for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1R) bound to the hormone GLP-1 or another peptide agonist show the bound peptide to be fully α-helical,9-12 but recent data suggest that a non-helical conformation near the peptide N-terminus contributes to agonist efficacy.3,5 The GLP-1R has received considerable attention because agonists thereof are used to treat type 2 diabetes.13 Peptides that activate other class B1 GPCRs are also subjects of clinical interest; agonists of the GLP-2R, for example, are used to treat short-bowel syndrome (SBS).14,15

We previously probed for deviations from α-helicity near the N-terminus of natural GLP-1R agonists by comparing receptor activation properties of analogues in which a conserved Gly was altered.5 The N-terminal region of these peptides engages the core of the receptor transmembrane domain (TMD), and this region of the agonist is thought to drive conformational changes that are sensed by cytosolic partners.2 When Gly10 of GLP-1(7-36) or the analogous Gly4 of exendin-4 (Ex-4; Figure 1) was replaced with a residue that enhances local helicity, such as L-Ala, potency declined.5 In contrast, analogues with Gly-→D-Ala replacement displayed native-like potency; this modification should promote a local deviation from α-helicity.16 Cryo-EM analysis of the Ex-4 Gly4-→D-Ala variant bound to a GLP-1R-Gs heterotrimer complex revealed two forms of the agonist peptide, one that was fully α-helical and the other featuring a deviation from helicity near the peptide N-terminus.5 Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that dynamic interconversion between helical and non-helical conformations near the N-terminus of the bound agonist is important for GLP-1R activation.

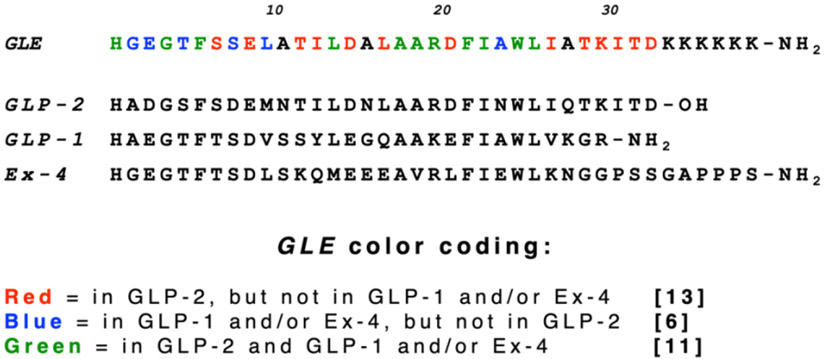

Figure 1.

Sequences of glepaglutide (GLE), GLP-2, GLP-1, and Ex-4. The residues of GLE are color-coded based on parallels to residues found in GLP-2, GLP-1 or Ex-4 at matched positions. Values in brackets indicate the number of shared residues.

Gly at the fourth position from the N-terminus is conserved among hormones in the glucagon family, including GLP-2.17,18 As a step toward understanding whether N-terminal deviations from helicity are relevant to the activation mechanisms of class B1 GPCRs beyond the GLP-1R, we have now examined analogues of two GLP-2R agonists, the hormone GLP-2 and the designed agonist glepaglutide (GLE; Figure 1), which is currently in clinical trials for SBS treatment.19 GLE activates both the GLP-2R and the GLP-1R, while GLP-2 is selective for the GLP-2R, and GLP-1 is selective for the GLP-1R.20 Therefore, GLE analogues containing replacements for Gly4 allowed us to compare responses of both the GLP-1R and the GLP-2R to the same agonist variants.

Results and Discussion

Experimental design.

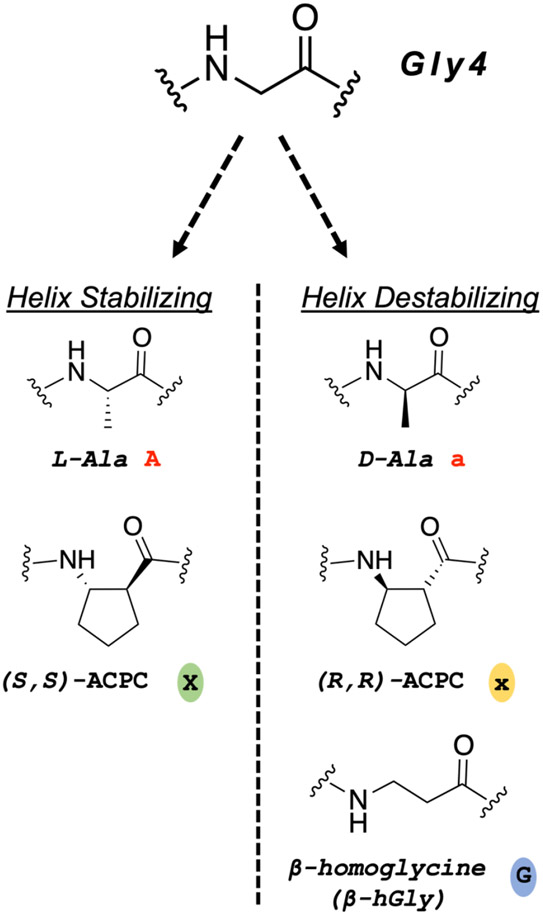

We examined five replacements for Gly4 that were intended to alter helical propensity near the N-terminus of GLP-2 or GLE (Figure 2). Replacing Gly with L-Ala leads to an increase in α-helical propensity of ~0.5 to 1.0 kcal/mol.16,21 The ring-constrained β-amino acid residue derived from (S,S)-trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid ((S,S)-ACPC) is quantitatively similar to L-Ala in favoring an α-helix-like conformation.22 In contrast, replacing Gly with D-Ala or (R,R)-ACPC leads to a decrease in helical propensity of ~0.5 or ~0.8 kcal/mol, respectively (for a right-handed α-helix-like conformation).16,22 The two Ala configurations and the two trans-ACPC configurations were evaluated in the previous study of Gly10 variants of GLP-1 and Gly4 variants of Ex-4.5 The present study included a fifth replacement for Gly4 of GLP-2 or GLE, β-homoglycine (β-hGly; also known as β-alanine). This modification matches the backbone extension resulting from an ACPC replacement but lacks the conformational constraint provided by the cyclopentyl ring. Replacing Gly with β-hGly destabilizes helical secondary structure by ~0.3 kcal/mol, which is smaller than the helix destabilization from Gly→D-Ala substitution.16 Given the small size of this energy increment, we expect that the Gly4-→β-hGly variant can access a fully helical conformation.

Figure 2.

Structures of amino acid residues used to replace Gly4 of GLP-2-NH2 or GLE in this study. Left: L-Alanine (L-Ala) and cyclic β-amino acid residue (S,S)-trans-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid ((S,S)-ACPC) are helix-stabilizing replacements. Right: D-Alanine (D-Ala), (R,R)-ACPC) and β-homoglycine (β-hGly; also called β-alanine) are helix-destabilizing replacements.

Examining Gly4-replacement analogues of GLP-2 allowed us to determine whether the pattern of GLP-2R activation responses parallels the GLP-1R activation response pattern previously observed among GLP-1 and Ex-4 analogues.5 For this comparison, both the parent hormone and the receptor are different. The GLE series enabled us to compare the responses of the GLP-1R and the GLP-2R to the same set of analogues. The original description of GLE focused entirely on activation of the GLP-2R, but it was subsequently reported that GLE activates the GLP-1R as well, albeit with reduced potency relative to GLP-1.20 As indicated in Figure 1, 24 of the 40 GLE residues match those in GLP-2; almost half of these residues are found also in GLP-1 and/or Ex-4. At six positions, however, GLE contains a residue that is not found in GLP-2 but has a match in GLP-1 and/or Ex-4. These sequence features presumably underlie the dual agonism manifested by GLE.

A new binding assay for the GLP-2R.

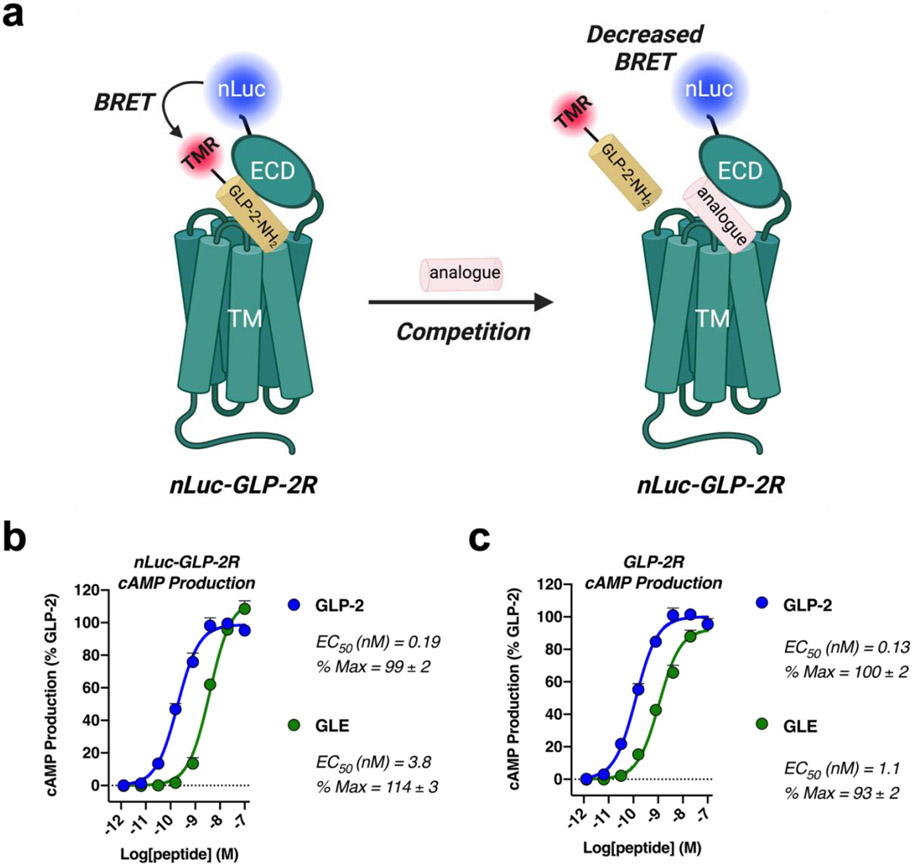

We wanted to measure the ability of each new analogue to activate the GLP-2R or the GLP-1R and to measure the ability of each new peptide to bind to the GLP-2R or the GLP-1R. For activation of each receptor, we used a standard cell-based assay format. HEK293 cells that stably express the GloSensor™ protein,23,24 an intracellular detector of cAMP, were transiently transfected with a gene for the GLP-1R or the GLP-2R. Both receptors signal predominantly through Gs, which leads to stimulation of intracellular cAMP production.25,26 Binding of GLP-1 and Ex-4 analogues to the GLP-1R was previously assessed with an assay involving bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET).5 This assay can be conducted with whole cells that have been metabolically poisoned to prevent receptor internalization after agonist engagement. We created a new BRET-based assay for GLP-2R binding to support the present study.

The BRET assay requires a version of the GLP-2R that has a nanoluciferase (nLuc)27 module fused to the N-terminus, preceding the extracellular domain (ECD) (Figure 3). When a peptide bearing a tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) unit binds to the nLuc-GLP-2R, the luminescence energy generated by the luciferase reaction is transferred to the TMR fluorophore, which emits light.28 We performed this assay in competition mode, monitoring the displacement by unlabeled peptides of a GLP-2(1-34)-NH2 variant containing a TMR unit on the side chain of Lys34.

Figure 3.

nLuc-GLP-2R competition binding assay for measuring the affinity of GLP-2, GLE and their derivatives. (a) Cartoon depiction of the nLuc-GLP-2R bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay. (b) The effect of nanoluciferase (nLuc) fusion to the GLP-2R was evaluated in HEK293 cells stably expressing the GloSensor™ protein. cAMP production was measured in response to GLP-2 or GLE. Data points represent the mean of ≥2 independent experiments. (c) Production of cAMP in response to GLP-2 or GLE was assessed in HEK293 cells expressing the native GLP-2R and GloSensor™ proteins. Data points represent the mean of ≥2 independent experiments. In both (b) and (c), data were normalized relative to GLP-2; errors bars represent S.E.M.

The nLuc-GLP-2R is competent for signal transduction upon stimulation by GLP-2 or GLE, as indicated via intracellular cAMP production (Figure 3). The GLP-2 vs. GLE potency ratio is slightly larger for the nLuc-GLP-2R relative to the native GLP-2R (Figure 3a,b); this difference may indicate an unfavorable but minor interaction between the hexa-Lys C-terminal extension in GLE and the fused nLuc module. Comparisons within the GLP-2 analogue series or within the GLE analogue series should not be affected by this factor.

GLP-2 variants with substitutions for Gly4.

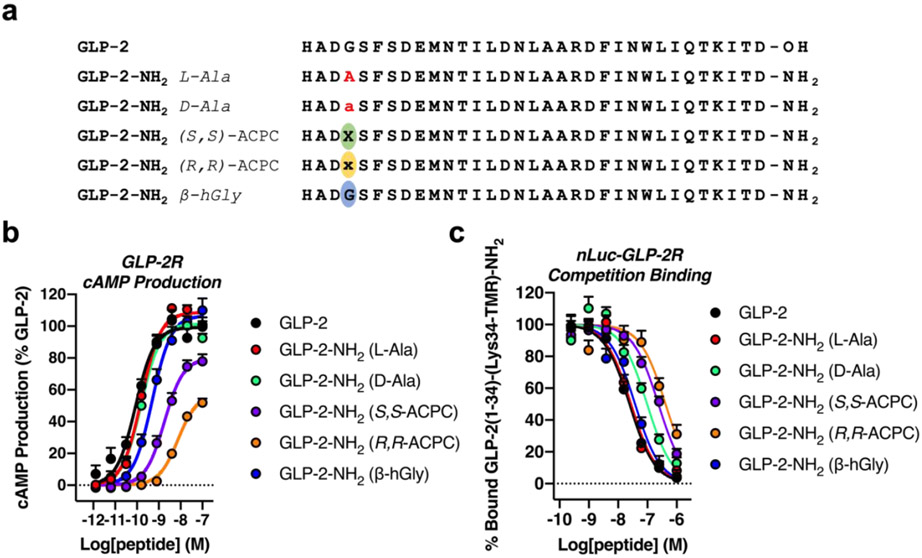

Five GLP-2 variants with replacements for Gly4 are shown in Figure 4a. All GLP-2 variants were prepared with a primary amide at the C-terminus. Natural GLP-2 is a C-terminal acid, and altering the C-terminus to a primary amide had no effect on GLP-2R activation in the context of the natural sequence (Figure S1). We use “GLP-2” to indicate the natural C-terminal acid form of the hormone, while “GLP-2-NH2” describes the C-terminal amide analogue of the hormone.

Figure 4.

The effects of Gly4 replacement on GLP-2R activation and nLuc-GLP-2R binding by GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 analogues. (a) Sequences of GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 analogues with substitutions at Gly4. (b) Activation of the GLP-2R by GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 analogues, as measured by cAMP production in GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the GLP-2R. Data points represent the average of ≥3 independent experiments. Data were normalized relative to GLP-2. (c) nLuc-GLP-2R competition binding, as measured by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, for unlabeled GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 analogues. Assays were performed in GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the nLuc-GLP-2R. 20 nM of tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-labeled GLP-2(1-34)-(Lys34-TMR)-NH2 tracer was used. Data points represent the mean of ≥4 independent experiments. All uncertainties in (b) and (c) are expressed as S.E.M.

Replacements at Gly4 resulted in varying potencies (EC50 values) and efficacies (% maxima) for GLP-2R activation, as indicated by stimulation of intracellular cAMP production (Figure 4b and Table 1). The GLP-2R activation pattern among these GLP-2-NH2 variants differed from the GLP-1R activation pattern previously observed for GLP-1(7-36) variants at Gly10 (the site analogous to Gly4 in GLP-2).5 In the GLP-2-NH2 series, agonist activity was not significantly changed when Gly4 was replaced by L-Ala or by D-Ala. In contrast, Gly10-→L-Ala in GLP-1(7-36) led to a substantial decline in potency, while Gly10-→D-Ala caused little change.5 The same trend was observed for Gly4 variants of Ex-4, another natural GLP-1R agonist. The similarity in activation profiles for Gly, L-Ala and D-Ala at position 4 of GLP-2-NH2 indicates that the GLP-2R is not sensitive to changes in α-helical propensity near the agonist N-terminus, in contrast to the GLP-1R.5

Table 1.

GLP-2R activation and nLuc-GLP-2R affinity for GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 analogues.

| GLP-2R cAMP Production | nLuc-GLP-2R Affinity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | EC50 (nM) | EC50 relative | % Max | IC50 (nM) | IC50 relative |

| GLP-2 | 0.086 | 1 | 99 ± 3 | 25 | 1 |

| GLP-2-NH2 L-Ala | 0.16 | 2 | 109 ± 2 | 28 | 1 |

| GLP-2-NH2 D-Ala | 0.15 | 2 | 101 ± 2 | 98 | 4 |

| GLP-2-NH2 (S,S)-ACPC | 1.8 | 21 | 80 ± 3 | 240 | 10 |

| GLP-2-NH2 (R,R)-ACPC | 7.5 | 87 | 57 ± 2 | 420 | 17 |

| GLP-2-NH2 β-hGly | 0.50 | 6 | 107 ± 3 | 38 | 2 |

EC50 and maximal response (% Max) values were derived from ≥3 independent experiments. EC50 relative indicates cAMP potency normalized to the potency of GLP-2 (GLP-2-NH2 analogue/GLP-2). For nLuc-GLP-2R competition binding experiments, IC50 values are the average of ≥4 independent experiments. IC50 relative indicates affinity normalized to GLP-2 (GLP-2-NH2 analogue/GLP-2).

Replacing Gly4 of GLP-2-NH2 with either ACPC enantiomer significantly diminished potency (Figure 4b and Table 1). In addition, the % maximum was moderately diminished for the (S,S)-ACPC variant, and more strongly diminished for the (R,R)-ACPC variant. Declines in potency were previously observed when Gly10 of GLP-1 or Gly4 of Ex-4 was replaced with an ACPC residue,5 but the trend in GLP-1R activation was the opposite of the GLP-2R trend. Among GLP-1 and Ex-4 derivatives, the one containing (R,R)-ACPC was more potent and showed a higher % maximum than the one containing (S,S)-ACPC. The GLP-2R trend suggests that a fully helical agonist conformation, as observed via cryo-EM for receptor-bound GLP-2,29 may be sufficient for activation, since (S,S)-ACPC is much more favorable in a right-handed α-helix-like conformation relative to (R,R)-ACPC (~1.3 kcal/mol).22

Gly4-→β-hGly replacement caused only a minor decline in potency and no change in % maximum relative to GLP-2 (Figure 4b and Table 1). Thus, the flexible β-hGly residue was much better tolerated than either of the ring-constrained β residues in terms of the GLP-2R activation. These observations suggest that the steric bulk of the cyclopentyl unit in ACPC may lead to unfavorable interactions with this receptor.

Binding of GLP-2 and the five GLP-2-NH2 variants to the nLuc-GLP-2R was evaluated via the competition BRET assay (Figure 4c and Table 1). The affinity trend differs from that previously observed for GLP-1(7-36) variants with the nLuc-GLP-1R.5 In the GLP-2-NH2 series, Gly4-→L-Ala had no effect on receptor affinity (consistent with findings of Gabe et al.30), and Gly4→D-Ala caused only a small decline in affinity. In contrast, substantial GLP-1R affinity declines were previously observed for the Gly10→L-Ala and Gly10-→D-Ala replacements in GLP-1(7-36).5 For both hormone/receptor pairs, the (S,S)-ACPC derivative bound more strongly than the (R,R)-ACPC derivative; however, the G1y10→(S,S)-ACPC derivative of GLP-1(7-36) had the highest affinity for the GLP-1R among the four variants of the native hormone, while the Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC derivative of GLP-2-NH2 had diminished affinity for the GLP-2R relative to the L-Ala or D-Ala derivatives. The affinity for the GLP-2R of the Gly10-→-hGly GLP-2-NH2 variant was comparable to that of the Gly10-→L-Ala GLP-2-NH2 variant (Figure 4c and Table 1). Collectively, these observations support the hypothesis that ACPC side chain atoms may have unfavorable steric interactions with the GLP-2R.

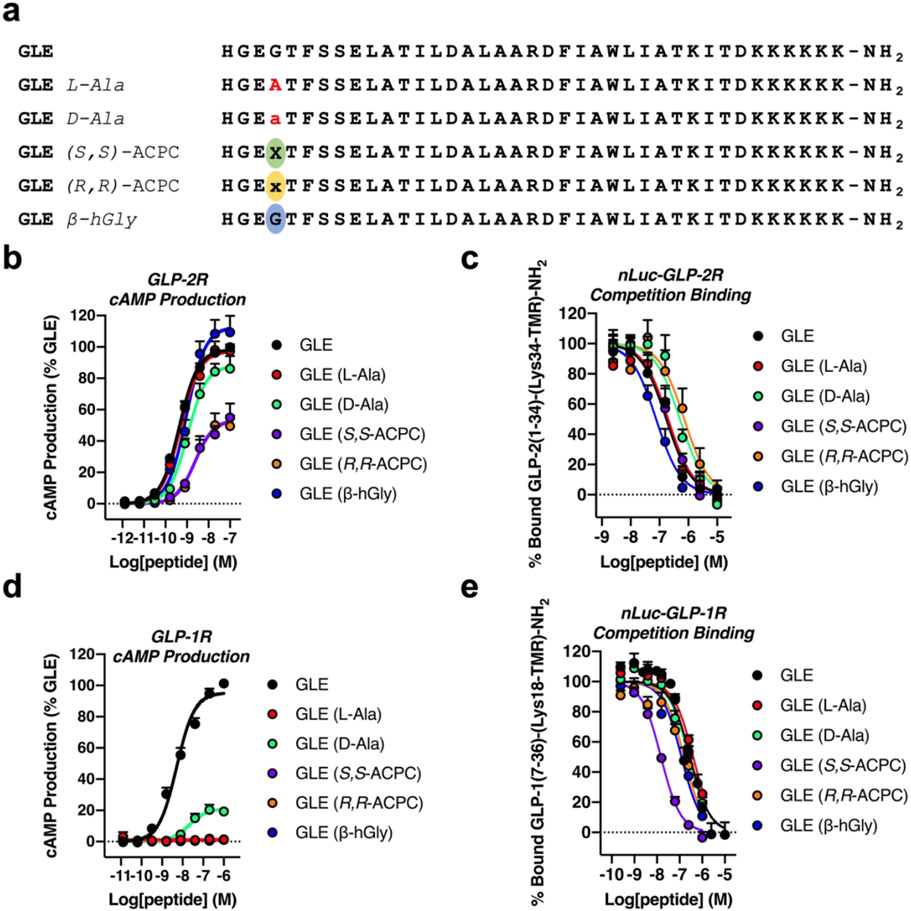

GLE variants with substitutions for Gly4.

The GLP-2R was very tolerant of GLE substitutions at position 4 (Figure 5b and Table 2). The variants containing L-Ala, D-Ala and β-hGly all displayed potencies within three-fold of the GLE potency. The potencies of the two ACPC-containing diastereomers were only modestly lower relative to GLE (~5-fold higher EC50 values), although the % maximum was reduced in both cases. A comparable tolerance was observed in the binding assay, with little variation in IC50 values among GLE and the five replacements for Gly4 (Figure 5c and Table 2). GLE bound to the nLuc-GLP-2R with ~10-fold lower affinity relative to GLP-2 (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

The effects of Gly4 replacement on GLP-2R activation, nLuc-GLP-2R binding, GLP-1R activation and nLuc-GLP-1R binding by GLE and analogues. (a) Sequences of GLE and analogues with substitutions at Gly4. (b) Activation of the GLP-2R by GLE and analogues as measured by cAMP production in HEK293 cells transiently expressing the GLP-2R and stably expressing the GloSensor™. Data points represent the average of ≥4 independent experiments. (c) nLuc-GLP-2R competition binding, as measured by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), for unlabeled GLE and analogues. Assays were performed in GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the nLuc-GLP-2R. 20 nM of tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-labeled GLP-2(1-34)-(Lys34-TMR)-NH2 tracer was used. Data points represent the mean of ≥5 independent experiments. (d) GLP-1R activation, as measured by cAMP production in GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the GLP-1R. Data points represent the average of ≥3 independent experiments. (e) nLuc-GLP-1R competition binding, as measured by BRET, for unlabeled GLE and analogues. Assays were performed in GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the nLuc-GLP-1R. 5 nM of tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-labeled GLP-1(7-36)-(Lys18-TMR)-NH2 tracer was used. Data points represent the mean of ≥3 independent experiments. Data in (b) and (d) were normalized relative to GLE. All uncertainties in (a-d) are expressed as S.E.M.

Table 2.

GLP-2R activation and nLuc-GLP-2R affinity for GLE and analogues.

| GLP-2R cAMP Production | nLuc-GLP-2R Affinity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | EC50 (nM) | EC50 relative | % Max | IC50 (nM) | IC50 relative |

| GLE | 0.44 | 1 | 98 ± 1 | 170 | 1 |

| GLE L-Ala | 0.50 | 1 | 97 ± 2 | 200 | 1 |

| GLE D-Ala | 1.1 | 3 | 88 ± 3 | 510 | 3 |

| GLE (S,S)-ACPC | 2.4 | 5 | 54 ± 4 | 200 | 1 |

| GLE (R,R)-ACPC | 2.4 | 5 | 53 ± 4 | 720 | 4 |

| GLE β-hGly | 0.95 | 2 | 113 ± 5 | 76 | 0.4 |

EC50 and maximal response (% Max) values were derived from ≥4 independent experiments. EC50 relative indicates potency normalized to GLE (GLE analogue/GLE). For nLuc-GLP-2R competition binding experiments, IC50 values represent the average of 4 independent experiments. IC50 relative indicates affinity normalized to GLE (GLE analogue/GLE).

Hargrove et al. reported that GLE activates the GLP-1R, although with significantly lower potency relative to GLP-1,20 and our observations are consistent with this report. We observed an EC50 value of 5.1 nM for GLE (Figure 5d and Table 3), and we previously observed EC50 = 0.031 nM for GLP-1(7-36) in this assay.5 Hargrove et al. reported 8.7 and 0.020 nM EC50 values for GLE and GLP-1, respectively, in a comparable assay.20 The status of GLE as a dual agonist of the GLP-1R and GLP-2R allowed us to compare directly the responses of these two receptors to variations at Gly4 within a single peptide series (Figure 5 and Table 3).

Table 3.

GLP-1R activation and nLuc-GLP-1R affinity for GLE and analogues.

| GLP-1R cAMP Production | nLuc-GLP-1R Affinity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | EC50 (nM) | EC50 relative | % Max | IC50 (nM) | IC50 relative |

| GLE | 5.1 | 1 | 95 ± 2 | 290 | 1 |

| GLE L-Ala | >1000 | >200 | NR | 390 | 1 |

| GLE D-Ala | 21 | 4 | 21 ± 2 | 250 | 0.9 |

| GLE (S,S)-ACPC | >1000 | >200 | NR | 15 | 0.05 |

| GLE (R,R)-ACPC | >1000 | >200 | NR | 160 | 0.6 |

| GLE β-hGly | >1000 | >200 | NR | 120 | 0.4 |

EC50 and maximal response (% Max) values were derived from ≥4 independent experiments. EC50 relative indicates potency normalized to GLE (GLE analogue/GLE). For nLuc-GLP-1R competition binding experiments, IC50 values represent the average of 4 independent experiments. IC50 relative indicates affinity normalized to GLE (GLE analogue/GLE). NR = No Response.

Activation of the GLP-1R was extremely sensitive to variations at Gly4 of GLE, which contrasted with the insensitivity of GLP-2R activation to these variations (Figure 5d and Table 3). Among the GLE variants, only Gly4-→D-Ala stimulated a detectable level of intracellular cAMP generation at the GLP-1R. EC50 for this variant was similar to that of GLE, but efficacy was much lower: maximum cAMP production for GLE Gly4-→D-Ala was only ~21% of the maximum for GLE (Table 3). The superiority of the Gly4-→D-Ala variant among the GLE derivatives as an agonist of the GLP-1R paralleled the superiority of the Gly10-→D-Ala variant among the GLP-1 derivatives, although the latter showed native-like efficacy, matching the % maximum cAMP production stimulated by GLP-1(7-36) itself.5

In contrast to the low or undetectable agonist activity of the GLE Gly4 variants at the GLP-1R, all of these peptides were comparable or superior to GLE in terms of binding to the GLP-1R (Table 3). GLE Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC displayed ~20-fold higher affinity for the nLuc-GLP-1R relative to GLE itself. The tolerance of GLE Gly4 variations in terms of binding to the GLP-1R represents a striking contrast to the impact of GLP-1(7-36) Gly10 variations, all of which were previously shown to weaken affinity substantially relative to GLP-1(7-36) itself.5

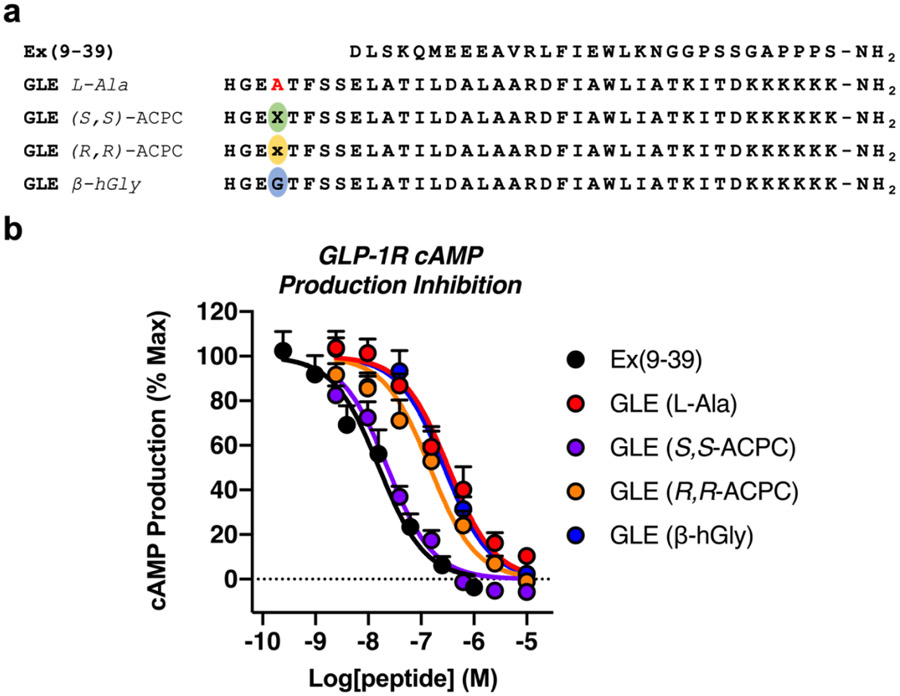

A novel activity profile from GLE variants: GLP-2R agonist/GLP-1R antagonist.

The combination of high affinity for the GLP-1R and inability to activate this receptor displayed by four of the GLE variants suggested that these peptides might function as antagonists of GLP-1R signaling. This hypothesis was tested by exposing cells expressing the GLP-1R to varying concentrations of GLE variants for 30 min, followed by addition of 0.25 nM GLP-1 to stimulate cAMP production (Figure 6). IC50 values for the GLE variants were calculated from the resulting cAMP production data (Table 4). Ex(9-39), a potent GLP-1R antagonist that is in clinical trials for treatment of postbariatric hypoglycemia,31 was used as a positive control. GLE Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC, which showed the highest affinity for the nLuc-GLP-1R (Table 3), was the most potent GLP-1R antagonist among the GLE derivatives (Table 4). GLE Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC was indistinguishable from Ex(9-39) as an antagonist of GLP-1-stimulated cAMP production (Figure 6b and Table 4). The nLuc-GLP-1R binding data were consistent with this conclusion: the IC50 of the GLE Gly4→(S,S)-ACPC for inhibiting fluorescent tracer binding was 15 nM, and the IC50 of Ex(9-39) was 10 nM (Figure S3).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of GLP-1(7-36)-stimulated cAMP production at the GLP-1R by GLE analogues. (a) Sequences of Ex(9-39), a previously reported GLP-1R antagonist,31 and GLE analogues modified at Gly4. (b) Inhibition of cAMP production after pretreating GloSensor™ HEK293 cells transiently expressing the GLP-1R with the indicated GLE analogues for 30 min followed by stimulation with 0.25 nM GLP-1. Data points represent the average of ≥4 independent experiments. All error bars represent S.E.M.

Table 4.

Inhibition of GLP-1-stimulated cAMP production by GLE analogues.

| GLP-1R cAMP Production Inhibition |

||

|---|---|---|

| Peptide | IC50 (nM) | IC50 relative |

| Ex(9-39) | 16 | 1 |

| GLE L-Ala | 330 | 21 |

| GLE (S,S)-ACPC | 23 | 1 |

| GLE (R,R)-ACPC | 150 | 9 |

| GLE β-hGly | 280 | 18 |

IC50 values are the average of 4 independent experiments. IC50 relative indicates the GLE analogue’s ability to inhibit GLP-1-stimulated cAMP production normalized to the inhibition by Ex(9-39): (GLE analogue/Ex(9-39)).

Conclusions

Recent cryo-EM analysis of the GLP-2+GLP-2R+Gs complex reveals a fully α-helical GLP-2 molecule with the N-terminal region embedded in the core of the receptor’s transmembrane domain.29 This structure is very similar to cryo-EM structures of the GLP-1(7-36)+GLP-1R+Gs complex,10 the glucagon+GCGR+Gs complex32 and complexes of these receptors with related peptide ligands.9,11,12,33,34 Despite these structural data, we recently provided evidence that the fully helical conformation of GLP-1(7-36) cannot completely explain the mechanism of GLP-1R activation, based on comparisons among GLP-1(7-36) variants modified at Gly10 or Ex-4 variants modified at Gly4,5 which corresponds to Gly4 in the related hormone GLP-2. Here we have extended this experimental strategy to GLP-2 and its cognate receptor. Our data suggest that GLP-2R activation is not strongly affected by variations in helix propensity at position 4 (Figure 4b and Table 1). In contrast to signal transduction mediated via the GLP-1R, signal transduction mediated via the GLP-2R may not require dynamic interconversion between helical and non-helical conformations near the agonist N-terminus. Some previous attempts to design pharmacologically useful GLP-2 analogues have focused on stabilizing the α-helical conformation.35,36 Our results suggest that alternative GLP-2-based design strategies can be effective even if they diminish α-helix propensity.

The clinical candidate GLE activates both the GLP-2R and the GLP-1R,20 and the Gly4 variant series derived from GLE was therefore used to interrogate both receptors. At the GLP-2R, there was even less sensitivity to variation at position 4 of GLE than was observed for variation at position 4 of GLP-2-NH2, in terms of both receptor activation and binding (Figure 5b,c and Table 2). In contrast, GLP-1R activation by GLE variants was profoundly sensitive to substitutions for Gly4 (Figure 5d and Table 3). Only the D-Ala variant could activate this receptor, albeit with low efficacy. Despite the inability of most GLE Gly4 variants to activate the GLP-1R, all variants displayed high affinity for the receptor, matching or exceeding the affinity of GLE itself (Figure 5d,e and Table 3). In contrast, trends in GLP-2R activation and binding were similar among the set of GLP-2-NH2 Gly4 variants and the set of GLE Gly4 variants (Figures 4,5 and Tables 1,2).

Our results show that modification of Gly4 in the dual agonist GLE can generate GLP-2R-selective variants. Several natural peptide hormones contain a glycine residue near the N-terminus,18 and some of these hormones have been shown to activate two or more class B1 GPCRs.37-40 It is possible that carefully selected modifications at this glycine residue could be used to promote receptor selectivity among known di- or tri-agonists.

The GLE variant containing the cyclic β-amino acid residue (S,S)-ACPC in place of Gly4 displayed an intriguing activity profile, serving as an agonist of the GLP-2R (only slightly less potent than GLE itself) and a potent antagonist of the GLP-1R (comparable to Ex(9-39)). GLE Gly4->(S,S)-ACPC may be useful as a research tool because of the interplay between the physiological effects mediated by these two receptors. Life-threatening hypoglycemia is the main feature of congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) in neonates and infants.41 Hypoglycemic episodes are also common among adults after bariatric surgery;42 some of these adults develop SBS as a postoperative complication.43 In each case, the GLP-1R antagonist Ex(9-39) (also called avexitide) displayed therapeutic potential in preventing hypoglycemia.44,45 Effects of concomitant GLP-2R activation and GLP-1R antagonism have not been previously explored. We speculate that concomitant GLP-2R activation and GLP-1R antagonism could simultaneously improve nutrient absorption46 and increase blood glucose levels in CHI patients.45 In addition, the GLP-2R agonist/GLP-1R antagonist combination might be useful for addressing hypoglycemic events in post-operative individuals with SBS.19,47

There is increasing interest in the development of peptide hormone analogues that activate two or even three among the closely related receptors for glucagon, GLP-1, GLP-2 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP).48-52 Tirzepatide, a dual agonist of the GLP-1R and the GIP receptor (GIPR), is approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes, and more recently Tirzepatide was shown to induce substantial weight reductions in obese patients.53-55 There is also clinical interest in a dual GLP-1R agonist/GIPR antagonist for this clinical application.56,57 Agents with other combinations of agonist and antagonist activities, such as GLE Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC, may display distinctive physiological effects, perhaps leading to clinical advances.

Gly4-→(S,S)-ACPC replacement in Ex-4 (previous work)5 and in GLE (this work) generated potent GLP-1R antagonists. Each of these variants rivaled the inhibitory activity of clinical candidate Ex(9-39), an N-terminally truncated derivative of Ex-4. The discovery of two full-length antagonists that contain a cyclic β-amino acid residue at position 4 but differ at many other sequence positions suggests that the interaction between the (S,S)-ACPC residue and the GLP-1R plays a key role in the mechanism of antagonism. The cyclic side chain of this β residue may, for example, cause the agonist surface to bulge outward relative to the surface of the native Gly residue. Future structural analysis of complexes containing (S,S)-ACPC variants bound to the GLP-1R may reveal how this single-site modification fosters high affinity but prevents activation of this receptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM056414, awarded to S.H.G.). B.P.C. was supported, in part, by a graduate fellowship from the National Science Foundation (DGE-1747503) and by a Biotechnology Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 GM008349). We are also grateful for partial support from the Vilas Trust.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

nLuc-GLP-2R plasmid DNA sequence, Comparison of GLP-2 and GLP-2-NH2 at stimulating cAMP production at GLP-2R, Comparison of GLE and GLP-2 binding at nLuc-GLP-2R, nLuc-GLP-1R binding dose-responses for GLE, GLE (S,S-ACPC) and Ex(9-39), Table of reagents and resources, Experimental procedures for peptide synthesis, cell culture, cAMP production assay, nLuc-GLP-2R or nLuc-GLP-1R competition binding, GLP-1R cAMP inhibition, MALDI and UPLC characterization of peptides

Competing Interests

S.H.G. is a cofounder of Longevity Biotech, Inc., which is pursuing biomedical applications for α/β-peptides.

References

- (1).Wootten D; Christopoulos A; Marti-Solano M; Babu MM; Sexton PM Mechanisms of Signalling and Biased Agonism in G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19 (10), 638–653. 10.1038/s41580-018-0049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cary BP; Zhang X; Cao J; Johnson RM; Piper SJ; Gerrard EJ; Wootten D; Sexton PM New Insights into the Structure and Function of Class B1 GPCRs. Endocr Rev 2023, 1–26. 10.1210/ENDREV/BNAC033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Deganutti G; Liang YL; Zhang X; Khoshouei M; Clydesdale L; Belousoff MJ; Venugopal H; Truong TT; Glukhova A; Keller AN; Gregory KJ; Leach K; Christopoulos A; Danev R; Reynolds CA; Zhao P; Sexton PM; Wootten D Dynamics of GLP-1R Peptide Agonist Engagement Are Correlated with Kinetics of G Protein Activation. Nature Communications 2022, 13 (1), 1–18. 10.1038/s41467-021-27760-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhao P; Truong TT; Merlin J; Sexton PM; Wootten D Implications of Ligand-Receptor Binding Kinetics on GLP-1R Signalling. Biochem Pharmacol 2022, 199, 114985. 10.1016/J.BCP.2022.114985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cary BP; Deganutti G; Zhao P; Truong TT; Piper SJ; Liu X; Belousoff MJ; Danev R; Sexton PM; Wootten D; Gellman SH Structural and Functional Diversity among Agonist-Bound States of the GLP-1 Receptor. Nat Chem Biol 2022, 18 (3), 256–263. 10.1038/s41589-021-00945-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hilger D; Hilger CD The Role of Structural Dynamics in GPCR-Mediated Signaling. FEBS J 2021, 288 (8), 2461–2489. 10.1111/FEBS.15841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hilger D; Masureel M; Kobilka BK Structure and Dynamics of GPCR Signaling Complexes. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2018, 25 (1), 4–12. 10.1038/s41594-017-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Latorraca NR; Venkatakrishnan AJ; Dror RO GPCR Dynamics: Structures in Motion. Chem Rev 2011, 117 (1), 139–155. 10.1021/ACS.CHEMREV.6B00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Liang YL; Khoshouei M; Glukhova A; Furness SGB; Zhao P; Clydesdale L; Koole C; Truong TT; Thai DM; Lei S; Radjainia M; Danev R; Baumeister W; Wang MW; Miller LJ; Christopoulos A; Sexton PM; Wootten D Phase-Plate Cryo-EM Structure of a Biased Agonist-Bound Human GLP-1 Receptor–Gs Complex. Nature 2018, 555 (7694), 121–125. 10.1038/NATURE25773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang X; Belousoff MJ; Zhao P; Kooistra AJ; Truong TT; Ang SY; Underwood CR; Egebjerg T; Šenel P; Stewart GD; Liang YL; Glukhova A; Venugopal H; Christopoulos A; Furness SGB; Miller LJ; Reedtz-Runge S; Langmead CJ; Gloriam DE; Danev R; Sexton PM; Wootten D Differential GLP-1R Binding and Activation by Peptide and Non-Peptide Agonists. Mol Cell 2020, 80 (3), 485–500.e7. 10.1016/J.MOLCEL.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhao F; Zhou Q; Cong Z; Hang K; Zou X; Zhang C; Chen Y; Dai A; Liang A; Ming Q; Wang M; Chen LN; Xu P; Chang R; Feng W; Xia T; Zhang Y; Wu B; Yang D; Zhao L; Xu HE; Wang MW Structural Insights into Multiplexed Pharmacological Actions of Tirzepatide and Peptide 20 at the GIP, GLP-1 or Glucagon Receptors. Nature Communications 2022, 13 (1), 1–16. 10.1038/s41467-022-28683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhang X; Belousoff MJ; Liang YL; Danev R; Sexton PM; Wootten D Structure and Dynamics of Semaglutide- and Taspoglutide-Bound GLP-1R-Gs Complexes. Cell Rep 2021, 36 (2), 109374. 10.1016/J.CELREP.2021.109374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Davenport AP; Scully CCG; de Graaf C; Brown AJH; Maguire, J. J. Advances in Therapeutic Peptides Targeting G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19 (6), 389–413. 10.1038/s41573-020-0062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Drucker DJ The Discovery of GLP-2 and Development of Teduglutide for Short Bowel Syndrome. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2019, 2 (2), 134–142. 10.1021/ACSPTSCI.9B00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Suzuki R; Brown GA; Christopher JA; Scully CCG; Congreve M Recent Developments in Therapeutic Peptides for the Glucagon-like Peptide 1 and 2 Receptors. J Med Chem 2020, 63 (3), 905–927. 10.1021/ACS.JMEDCHEM.9B00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fisher BF; Hong SH; Gellman SH Helix Propensities of Amino Acid Residues via Thioester Exchange. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139 (38), 13292–13295. 10.1021/JACS.7B07930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Moon MJ; Park S; Kim DK; Cho EB; Hwang JI; Vaudry H; Seong JY Structural and Molecular Conservation of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and Its Receptor Confers Selective Ligand-Receptor Interaction. Front. Endocrinol 2012, 3, 141. 10.3389/FENDO.2012.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Neumann JM; Couvineau A; Murail S; Lacapère JJ; Jamin N; Laburthe M Class-B GPCR Activation: Is Ligand Helix-Capping the Key? Trends Biochem Sci 2008, 33 (7), 314–319. 10.1016/J.TIBS.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Naimi RM; Hvistendahl M; Nerup N; Ambrus R; Achiam MP; Svendsen LB; Grønbæk H; Møller HJ; Vilstrup H; Steensberg A; Jeppesen PB Effects of Glepaglutide, a Novel Long-Acting Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Analogue, on Markers of Liver Status in Patients with Short Bowel Syndrome: Findings from a Randomised Phase 2 Trial. EBioMedicine 2019, 46, 444–451. 10.1016/J.EBIOM.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hargrove DM; Alagarsamy S; Croston G; Laporte R; Qi S; Srinivasan K; Sueiras-Diaz J; Wisniewski K; Hartwig J; Lu M; Posch AP; Wisniewska H; Schteingart CD; Rivière PJM; Dimitriadou V Pharmacological Characterization of Apraglutide, a Novel Long-Acting Peptidic Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Agonist, for the Treatment of Short Bowel Syndrome. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2020, 373 (2), 193–203. 10.1124/JPET.119.262238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pace CN; Scholtz JM A Helix Propensity Scale Based on Experimental Studies of Peptides and Proteins. Biophys J 1998, 75 (1), 422–427. 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fisher BF; Hong SH; Gellman SH Thermodynamic Scale of β-Amino Acid Residue Propensities for an α-Helix-like Conformation. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140 (30), 9396–9399. 10.1021/JACS.8B05162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Binkowski BF; Butler BL; Stecha PF; Eggers CT; Otto P; Zimmerman K; Vidugiris G; Wood MG; Encell LP; Fan F; Wood K. v. A Luminescent Biosensor with Increased Dynamic Range for Intracellular CAMP. ACS Chem Biol 2011, 6 (11), 1193–1197. 10.1021/CB200248H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fan F; Binkowski BF; Butler BL; Stecha PF; Lewis MK; Wood K. v. Novel Genetically Encoded Biosensors Using Firefly Luciferase. ACS Chem Biol 2008, 3 (6), 346–351. 10.1021/CB8000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gromada J; Holst JJ; Rorsman P Cellular Regulation of Islet Hormone Secretion by the Incretin Hormone Glucagon-like Peptide 1. Pflugers Arch 1998, 435 (5), 583–594. 10.1007/S004240050558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yusta B; Huang L; Munroe D; Wolff G; Fantaske R; Sharma S; Demchyshyn L; Asa SL; Drucker DJ Enteroendocrine Localization of GLP-2 Receptor Expression in Humans and Rodents. Gastroenterology 2000, 119 (3), 744–755. 10.1053/GAST.2000.16489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hall MP; Unch J; Binkowski BF; Valley MP; Butler BL; Wood MG; Otto P; Zimmerman K; Vidugiris G; MacHleidt T; Robers MB; Benink HA; Eggers CT; Slater MR; Meisenheimer PL; Klaubert DH; Fan F; Encell LP; Wood K. v. Engineered Luciferase Reporter from a Deep Sea Shrimp Utilizing a Novel Imidazopyrazinone Substrate. ACS Chem Biol 2012, 7 (11), 1848–1857. 10.1021/CB3002478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Stoddart LA; Johnstone EKM; Wheal AJ; Goulding J; Robers MB; MacHleidt T; Wood K. v.; Hill SJ; Pfleger KDG Application of BRET to Monitor Ligand Binding to GPCRs. Nature Methods 2015, 12 (7), 661–663. 10.1038/nmeth.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sun W; Chen LN; Zhou Q; Zhao LH; Yang D; Zhang H; Cong Z; Shen DD; Zhao F; Zhou F; Cai X; Chen Y; Zhou Y; Gadgaard S; van der Velden WJC; Zhao S; Jiang Y; Rosenkilde MM; Xu HE; Zhang Y; Wang MW A Unique Hormonal Recognition Feature of the Human Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Receptor. Cell Res 2020, 30 (12), 1098–1108. 10.1038/s41422-020-00442-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gabe MBN; von Voss L; Hunt JE; Gadgaard S; Gasbjerg LS; Holst JJ; Kissow H; Hartmann B; Rosenkilde MM Biased GLP-2 Agonist with Strong G Protein-Coupling but Impaired Arrestin Recruitment and Receptor Desensitization Enhances Intestinal Growth in Mice. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 1–16. 10.1111/BPH.16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tan M; Lamendola C; Luong R; McLaughlin T; Craig C Safety, Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of Repeat Subcutaneous Dosing of Avexitide (Exendin 9-39) for Treatment of Post-Bariatric Hypoglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020, 22 (8), 1406–1416. 10.1111/DOM.14048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Qiao A; Han S; Li X; Li Z; Zhao P; Dai A; Chang R; Tai L; Tan Q; Chu X; Ma L; Thorsen TS; Reedtz-Runge S; Yang D; Wang MW; Sexton PM; Wootten D; Sun F; Zhao Q; Wu B Structural Basis of Gs and Gi Recognition by the Human Glucagon Receptor. Science (1979) 2020, 367 (6484), 1346–1352. 10.1126/SCIENCE.AAZ5346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhang H; Qiao A; Yang L; van Eps N; Frederiksen KS; Yang D; Dai A; Cai X; Zhang H; Yi C; Cao C; He L; Yang H; Lau J; Ernst OP; Hanson MA; Stevens RC; Wang MW; Reedtz-Runge S; Jiang H; Zhao Q; Wu B Structure of the Glucagon Receptor in Complex with a Glucagon Analogue. Nature 2018, 553 (7686), 106–110. 10.1038/nature25153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Chang R; Zhang X; Qiao A; Dai A; Belousoff MJ; Tan Q; Shao L; Zhong L; Lin G; Liang YL; Ma L; Han S; Yang D; Danev R; Wang MW; Wootten D; Wu B; Sexton PM Cryo-Electron Microscopy Structure of the Glucagon Receptor with a Dual-Agonist Peptide. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295 (28), 9313–9325. 10.1074/JBC.RA120.013793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wisniewski K; Sueiras-Diaz J; Jiang G; Galyean R; Lu M; Thompson D; Wang YC; Croston G; Posch A; Hargrove DM; Wiśniewska H; Laporte R; Dwyer JJ; Qi S; Srinivasan K; Hartwig J; Ferdyan N; Mares M; Kraus J; Alagarsamy S; Rivière PJM; Schteingart CD Synthesis and Pharmacological Characterization of Novel Glucagon-like Peptide-2 (GLP-2) Analogues with Low Systemic Clearance. J Med Chem 2016, 59 (7), 3129–3139. 10.1021/ACS.JMEDCHEM.5B01909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yang PY; Zou H; Lee C; Muppidi A; Chao E; Fu Q; Luo X; Wang D; Schultz PG; Shen W Stapled, Long-Acting Glucagon-like Peptide 2 Analog with Efficacy in Dextran Sodium Sulfate Induced Mouse Colitis Models. J Med Chem 2018, 61 (7), 3218–3223. 10.1021/ACS.JMEDCHEM.7B00768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Juarranz MG; van Rampelbergh J; Gourlet P; de Neef P; Cnudde J; Robberecht P; Waelbroeck M Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide VPAC1 and VPAC2 Receptor Chimeras Identify Domains Responsible for the Specificity of Ligand Binding and Activation. Eur J Biochem 1999, 265 (1), 449–456. 10.1046/J.14321327.1999.00769.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bataille D; Tatemoto K; Gespach C; Jörnvall H; Rosselin G; Mutt V Isolation of Glucagon-37 (Bioactive Enteroglucagon/Oxyntomodulin) from Porcine Jejuno-Ileum. FEBS Lett 1982, 146 (1), 79–86. 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mroz PA; Perez-Tilve D; Mayer JP; DiMarchi RD Stereochemical Inversion as a Route to Improved Biophysical Properties of Therapeutic Peptides Exemplified by Glucagon. Commun Chem 2019, 2 (1), 1–8. 10.1038/s42004-018-0100-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Piper SJ; Deganutti G; Lu J; Zhao P; Liang YL; Lu Y; Fletcher MM; Hossain MA; Christopoulos A; Reynolds CA; Danev R; Sexton PM; Wootten D Understanding VPAC Receptor Family Peptide Binding and Selectivity. Nat Commun 2022, 13 (1), 1–20. 10.1038/s41467-022-34629-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Demirbilek H; Hussain K Congenital Hyperinsulinism: Diagnosis and Treatment Update. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2017, 9 (Suppl 2), 69. 10.4274/JCRPE.2017.S007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Salehi M; Vella A; McLaughlin T; Patti ME Hypoglycemia After Gastric Bypass Surgery: Current Concepts and Controversies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103 (8), 2815–2826. 10.1210/JC.2018-00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).McBride CL; Petersen A; Sudan D; Thompson J Short Bowel Syndrome Following Bariatric Surgical Procedures. The American Journal of Surgery 2006, 192 (6), 828–832. 10.1016/J.AMJSURG.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Tan M; Lamendola C; Luong R; McLaughlin T; Craig C Safety, Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of Repeat Subcutaneous Dosing of Avexitide (Exendin 9-39) for Treatment of Post-Bariatric Hypoglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020, 22 (8), 1406–1416. 10.1111/DOM.14048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Stefanovski D; Vajravelu ME; Givler S; de Leon DD Exendin-(9-39) Effects on Glucose and Insulin in Children With Congenital Hyperinsulinism During Fasting and During a Meal and a Protein Challenge. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (6), 1381–1390. 10.2337/DC21-2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Amato A; Baldassano S; Mulè F GLP2: An Underestimated Signal for Improving Glycaemic Control and Insulin Sensitivity. Journal of Endocrinology 2016, 229 (2), R57–R66. 10.1530/JOE-16-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Eliasson J; Hvistendahl MK; Freund N; Bolognani F; Meyer C; Jeppesen PB Apraglutide, a Novel Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Analog, Improves Fluid Absorption in Patients with Short Bowel Syndrome Intestinal Failure: Findings from a Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2022, 46 (4), 896–904. 10.1002/JPEN.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Reiner J; Berlin P; Held J; Thiery J; Skarbaliene J; Griffin J; Russell W; Eriksson PO; Berner-Hansen M; Ehlers L; Vollmar B; Jaster R; Witte M; Lamprecht G Dapiglutide, a Novel Dual GLP-1 and GLP-2 Receptor Agonist, Attenuates Intestinal Insufficiency in a Murine Model of Short Bowel. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2022, 46 (5), 1107–1118. 10.1002/JPEN.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Gabe MBN; Skov-Jeppesen K; Gasbjerg LS; Schiellerup SP; Martinussen C; Gadgaard S; Boer GA; Oeke J; Torz LJ; Veedfald S; Svane MS; Bojsen-Møller KN; Madsbad S; Holst JJ; Hartmann B; Rosenkilde MM GIP and GLP-2 Together Improve Bone Turnover in Humans Supporting GIPR-GLP-2R Co-Agonists as Future Osteoporosis Treatment. Pharmacol Res 2022, 176, 106058. 10.1016/J.PHRS.2022.106058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Sánchez-Garrido MA; Brandt SJ; Clemmensen C; Müller TD; DiMarchi RD; Tschöp MH GLP-1/Glucagon Receptor Co-Agonism for Treatment of Obesity. Diabetologia 2017, 60 (10), 1851–1861. 10.1007/S00125-017-4354-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Brandt SJ; Götz A; Tschöp MH; Müller TD Gut Hormone Polyagonists for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Peptides (N.Y.) 2018, 100, 190–201. 10.1016/J.PEPTIDES.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Yang D; Zhou Q; Labroska V; Qin S; Darbalaei S; Wu Y; Yuliantie E; Xie L; Tao H; Cheng J; Liu Q; Zhao S; Shui W; Jiang Y; Wang MW G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Structure- and Function-Based Drug Discovery. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6 (1), 1–27. 10.1038/s41392-020-00435-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Willard FS; Douros JD; Gabe MBN; Showalter AD; Wainscott DB; Suter TM; Capozzi ME; van der Velden WJC; Stutsman C; Cardona GR; Urva S; Emmerson PJ; Holst JJ; D’Alessio DA; Coghlan MP; Rosenkilde MM; Campbell JE; Sloop KW Tirzepatide Is an Imbalanced and Biased Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist. JCI Insight 2020, 5 (17), e140532. 10.1172/JCI.INSIGHT.140532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Rosenstock J; Wysham C; Frias JP; Kaneko S; Lee CJ; Fernández Landó L; Mao H; Cui X; Karanikas CA; Thieu VT Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-1): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet 2021, 398 (10295), 143–155. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jastreboff AM; Aronne LJ; Ahmad NN; Wharton S; Connery L; Alves B; Kiyosue A; Zhang S; Liu B; Bunck MC; Stefanski A Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387 (3), 205–216. 10.1056/NEJMOA2206038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lu SC; Chen M; Atangan L; Killion EA; Komorowski R; Cheng Y; Netirojjanakul C; Falsey JR; Stolina M; Dwyer D; Hale C; Stanislaus S; Hager T; Thomas VA; Harrold JM; Lloyd DJ; Vèniant MM GIPR Antagonist Antibodies Conjugated to GLP-1 Peptide Are Bispecific Molecules That Decrease Weight in Obese Mice and Monkeys. Cell Rep Med 2021, 2 (5), 100263. 10.1016/J.XCRM.2021.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Killion EA; Wang J; Yie J; Shi SDH; Bates D; Min X; Komorowski R; Hager T; Deng L; Atangan L; Lu SC; Kurzeja RJM; Sivits G; Lin J; Chen Q; Wang Z; Thibault SA; Abbott CM; Meng T; Clavette B; Murawsky CM; Foltz IN; Rottman JB; Hale C; Veniant MM; Lloyd DJ Anti-Obesity Effects of GIPR Antagonists Alone and in Combination with GLP-1R Agonists in Preclinical Models. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10 (472), 3392. 10.1126/SCITRANSLMED.AAT3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.