Abstract

Background

Primary healthcare (PHC) integration has been promoted globally as a tool for health sector reform and universal health coverage (UHC), especially in low‐resource settings. However, for a range of reasons, implementation and impact remain variable. PHC integration, at its simplest, can be considered a way of delivering PHC services together that sometimes have been delivered as a series of separate or 'vertical' health programmes. Healthcare workers are known to shape the success of implementing reform interventions. Understanding healthcare worker perceptions and experiences of PHC integration can therefore provide insights into the role healthcare workers play in shaping implementation efforts and the impact of PHC integration. However, the heterogeneity of the evidence base complicates our understanding of their role in shaping the implementation, delivery, and impact of PHC integration, and the role of contextual factors influencing their responses.

Objectives

To map the qualitative literature on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of PHC integration to characterise the evidence base, with a view to better inform future syntheses on the topic.

Search methods

We used standard, extensive Cochrane search methods. The latest search date was 28 July 2020. We did not search for grey literature due to the many published records identified.

Selection criteria

We included studies with qualitative and mixed methods designs that reported on healthcare worker perceptions and experiences of PHC integration from any country. We excluded settings other than PHC and community‐based health care, participants other than healthcare workers, and interventions broader than healthcare services. We used translation support from colleagues and Google Translate software to screen non‐English records. Where translation was not feasible we categorised these records as studies awaiting classification.

Data collection and analysis

For data extraction, we used a customised data extraction form containing items developed using inductive and deductive approaches. We performed independent extraction in duplicate for a sample on 10% of studies allowed for sufficient agreement to be reached between review authors. We analysed extracted data quantitatively by counting the number of studies per indicator and converting these into proportions with additional qualitative descriptive information. Indicators included descriptions of study methods, country setting, intervention type, scope and strategies, implementing healthcare workers, and client target population.

Main results

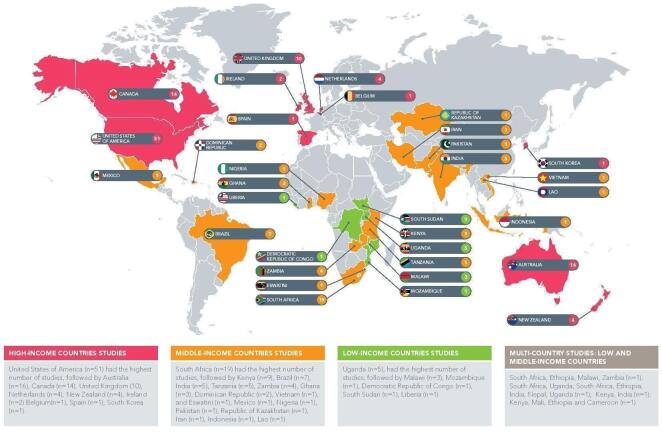

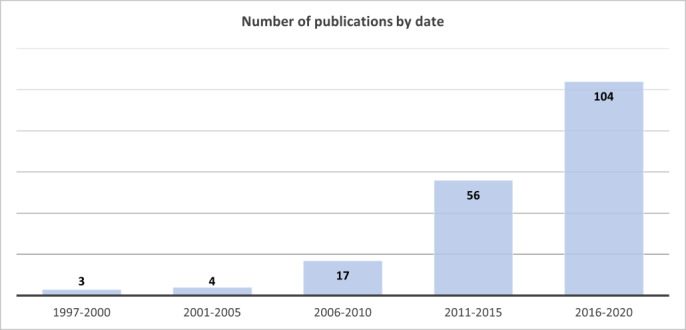

The review included 184 studies for analysis based on 191 included papers. Most studies were published in the last 12 years, with a sharp increase in the last five years. Studies mostly employed methods with cross‐sectional qualitative design (mainly interviews and focus group discussions), and few used longitudinal or ethnographic (or both) designs. Studies covered 37 countries, with close to an even split in the proportions of high‐income countries (HICs) and low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). There were gaps in the geographical spread for both HICs and LMICs and some countries were more dominant, such as the USA for HICs, South Africa for middle‐income countries, and Uganda for low‐income countries. Methods were mainly cross‐sectional observational studies with few longitudinal studies. A minority of studies used an analytical conceptual model to guide the design, implementation, and evaluation of the integration study.

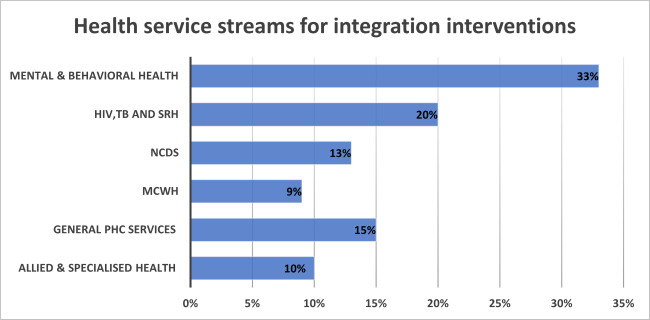

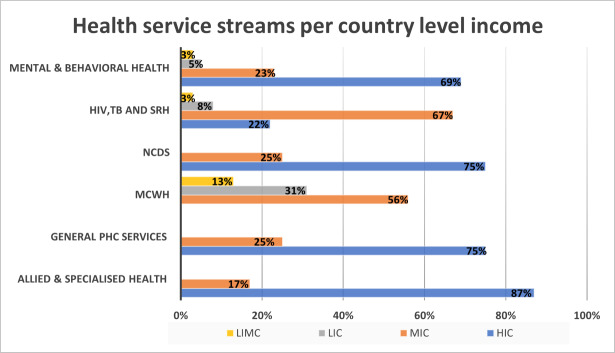

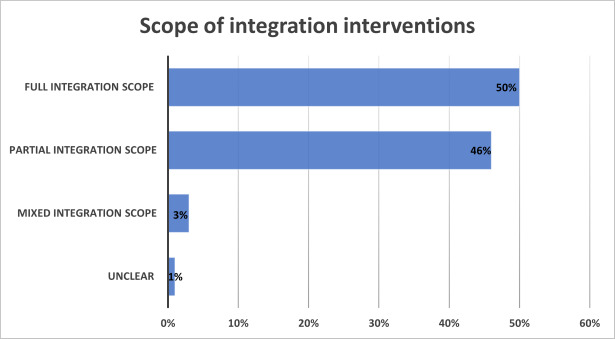

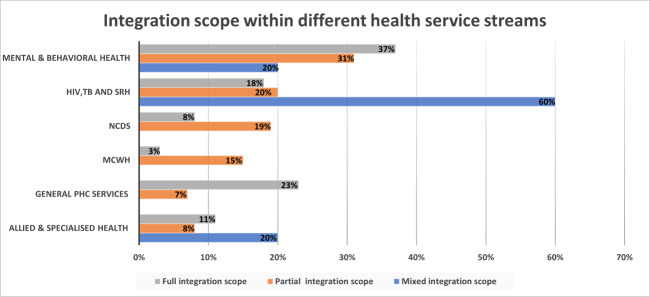

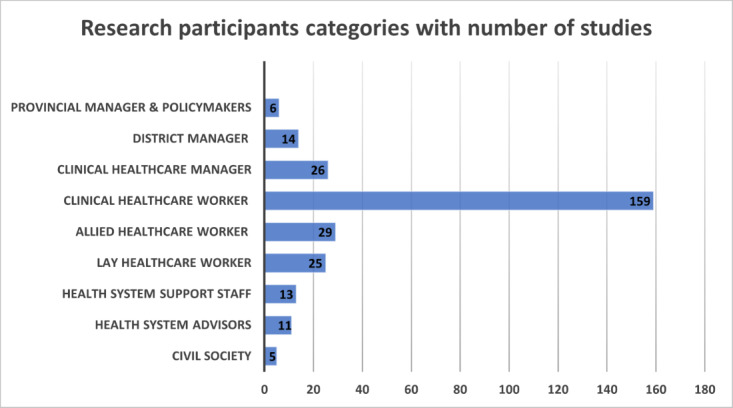

The main finding was the various levels of diversity found in the evidence base on PHC integration studies that examined healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences. The review identified six different configurations of health service streams that were being integrated and these were categorised as: mental and behavioural health; HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and sexual reproductive health; maternal, women, and child health; non‐communicable diseases; and two broader categories, namely general PHC services, and allied and specialised services. Within the health streams, the review mapped the scope of the interventions as full or partial integration. The review mapped the use of three different integration strategies and categorised these as horizontal integration, service expansion, and service linkage strategies. The wide range of healthcare workers who participated in the implementation of integration interventions was mapped and these included policymakers, senior managers, middle and frontline managers, clinicians, allied healthcare professionals, lay healthcare workers, and health system support staff. We mapped the range of client target populations.

Authors' conclusions

This scoping review provides a systematic, descriptive overview of the heterogeneity in qualitative literature on healthcare workers' perceptions and experience of PHC integration, pointing to diversity with regard to country settings; study types; client populations; healthcare worker populations; and intervention focus, scope, and strategies. It would be important for researchers and decision‐makers to understand how the diversity in PHC integration intervention design, implementation, and context may influence how healthcare workers shape PHC integration impact. The classification of studies on the various dimensions (e.g. integration focus, scope, strategy, and type of healthcare workers and client populations) can help researchers to navigate the way the literature varies and for specifying potential questions for future qualitative evidence syntheses.

Plain language summary

Healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of primary healthcare integration: a scoping review of qualitative evidence

What is primary healthcare integration?

Primary healthcare integration is a way of combining different primary healthcare services that have previously been delivered separately. The aim of this integration is usually to give people better access to healthcare and to make more efficient use of limited health resources.

Why is it important to know about healthcare workers' views and experiences?

Primary healthcare integration has been implemented in many different countries with varying success. Healthcare workers can influence the extent to which such changes in health services are implemented successfully. Learning about healthcare workers' views and experiences of primary healthcare integration can help us understand how healthcare workers might influence its implementation and its success or failure.

What was the purpose of this scoping review?

This scoping review searched for and mapped qualitative studies (studies with no numerical data) about healthcare workers' views and experiences of primary healthcare integration. We wanted to describe the available research to help inform future systematic reviews and research studies in this area.

How did we identify and map the evidence?

We searched for all published qualitative studies that reported on healthcare workers' views and experiences of primary healthcare integration up to 28 July 2020. We described the different study methods, countries, the scope and type of primary healthcare integration approaches, and the different types of healthcare workers and client groups involved. We then grouped the studies into categories.

What did we find?

We included 184 studies. The studies were from 37 countries. About half the studies took place in high‐income countries and half in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

The studies we found in our review covered a variety of settings, participants, and types of primary healthcare integration. There were different configurations for which healthcare service programmes were being combined for integrated service delivery. These were categorised into the following six configurations: mental health; HIV, tuberculosis, and sexual reproductive health; maternal, woman, and child health; non‐communicable diseases (for example, heart disease, diabetes); general primary health integration, and allied and specialised services. We also explored whether integrated service delivery was fully or partially integrated, and the different integration strategies used to link and co‐ordinate services.

The people participating in the implementation of integration interventions included policymakers, senior managers, middle and frontline managers, clinicians, allied healthcare professionals, lay health workers, and health system support staff. A wide range of clients were recipients of the integrated services.

Author's conclusions

This scoping review shows the variety of primary healthcare integration approaches that have been studied. Researchers and decision‐makers need to understand the relationship between different integration approaches and contexts, and the ways in which healthcare workers influence the impacts of this integration. The study categories we have developed can help researchers to understand these different types of integration approaches and to identify more focused questions for future systematic reviews.

Background

Efforts to promote delivery of integrated health services and systems at the primary healthcare (PHC) level have existed since the late 1970s. PHC was centrally embedded within the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 as a mechanism for achieving health for all by 2000 (WHO 1987). Integration of PHC services (or PHC integration), at its simplest, can be considered "a way of delivering a series of targeted technologies and interventions together that sometimes have been delivered as a series of 'vertical' programmes" (Dudley 2011). PHC integration is considered one way to provide efficient and high‐quality services that are potentially cost‐effective, and that can lead to accessible and equitable healthcare for people most in need (Foreit 2002; Oleribe 2015).

PHC integration has been promoted globally as a tool for health sector reform that can promote universal health coverage (UHC), especially in low‐resource settings (Walley 2008). There is a renewed focus on PHC integration; first, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and now the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) recognise that PHC integration is a vehicle for the delivery of comprehensive PHC services and UHC more broadly (Oleribe 2015). In its support to countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) has kept integration as a core mechanism for achieving UHC, through its approach of integrated People‐Centred Care (WHO 2013). More recently, this has been expressed in the Astana Declaration of 2018, emanating from the Global Conference on Primary Health Care (WHO 2018). However, despite the persistence of the concept of PHC integration as a mechanism, implementation has been slow and uneven, and the anticipated substantial, demonstrable, positive impact on universal access to quality healthcare has not been realised (Chuah 2017; Dudley 2011; Haldane 2017; Haldane 2018). Instead, research has shown variable and inconclusive impacts on service utilisation and disease outcomes (Baxter 2018a; Chuah 2017; Haldane 2017; Haldane 2018). Contributing factors have been shown to include political commitment, logistics, the burden of disease, health systems fragmentation, and financing arrangements (Hall 2003; Mounier‐Jack 2017; Schierhout 1999; Walley 2008).

The lack of a single, standard agreed‐upon definition and different approaches on how to achieve integration at a primary level may also be contributing to the variable impact of PHC integration implementation (Armitage 2009). Despite the tenaciousness of the thinking that integration is needed, there remains little coherence around what PHC integration is. This is evidenced in the plethora of definitions found across research studies and programme reports (Armitage 2009; Valentijn 2015). In practice, many governments, bilateral agencies, and non‐governmental organisations have attempted some form of PHC integration, but all using their own understanding, and even then, without necessarily having a shared understanding within their approaches. Yet, within this definitional morass, it is healthcare workers who are charged with the task of implementing integration and ensuring successful PHC coverage and UHC for all. Street‐level bureaucracy theory helps to show that healthcare workers determine interventions, arguing that what clients (or patients) and communities receive is based on healthcare workers' understanding of their task and shaped by their discretionary power in delivering the task (Erasmus 2011). To achieve the visions of the Alma Ata and Astana declarations, it would therefore be useful to better understand how integration is being operationalised by healthcare workers in PHC. To do so, it is essential that we first understand how healthcare workers perceive the meaning of PHC integration and how they experience the practice of integration in PHC.

We attempted to perform a qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) of healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of PHC integration (Moloi 2020). However, as with the plethora of definitions found, the available evidence was plentiful and widely heterogeneous. An adequate synthesis would have required a reduction of the material through sampling. Still, such sampling seemed too soon, as we had not fully been able to get a clear understanding of the diversity of the available evidence. Therefore, we changed our approach, beginning with a scoping of what studies have been conducted on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of PHC integration, in the hope that this, at a further date, may inform comprehensive and meaningful QES.

Description of the topic

Typically, within health systems, senior members of the system, such as policymakers and senior managers, will decide on what interventions to implement and will decide on the form of these interventions (Buse 2012; Hudson 2009). Yet, it is healthcare workers who are tasked with implementing these interventions, including primary care reform and integration. Healthcare workers are the face of health delivery throughout the world. As such, healthcare workers can and do shape how policy options are delivered, especially when working in challenging contexts in the public sector (e.g. chronic shortages, multiple demands, poor performance management) (Erasmus 2011). Healthcare workers may exercise their discretionary power as 'street‐level bureaucrats', to act in support of the policy or not, to decide which services are offered, how services are offered, and the benefits and sanctions allocated to citizens who are seeking the services (Erasmus 2008; Gilson 2015; Walker 2004). Therefore, a premise of this scoping review is that healthcare workers may shape how integration is delivered or implemented in PHC.

For the purpose of this review, we considered PHC integration as a set of interventions aimed at strengthening co‐ordination and linkages in the organisation, management and delivery of health services and systems, for improved access to comprehensive, effective, and efficient healthcare. Integration can allow clients access to comprehensive multidisciplinary services attuned to their needs; clients may receive multiple services during a single visit, either from a single healthcare worker or different healthcare workers and health services (Msuya 2004; Walley 2008).

In some settings, PHC services are sometimes delivered as separate, stand‐alone, or specialised services, often referred to as vertical health programmes. Vertical programmes are commonly implemented to ensure good access to priority health programmes, good coverage of these priority health services, and efficient monitoring and quality improvement systems (Atun 2008). Potential problems of vertical programmes include fragmentation and duplication of service delivery, inconvenience and inefficiencies for both clients and staff, and potentially a lack of effective coverage of comprehensive PHC needs of the population (Sundaram 2017). PHC integration attempts to address the access and efficiency problems associated with vertical services by reducing service fragmentation and promoting access to comprehensive care delivery options. This is sometimes referred to as horizontal integration to show the contrast with the siloed approach of vertical integration (Kumar 2016; Msuya 2004; Oleribe 2015; Walley 2008).

Approaches to integration lie on a continuum in terms of scope, from delivering more comprehensive clinical services at the point of care during a single visit to the integration of and across health system functions such as leadership and management functions, financial systems, human resource management, information systems, and equipment and drug supply systems. Integrated services may be delivered to different levels of integration of clinical and support services (full or partially integrated functions and levels), to enable the delivery of integrated clinical care and integrated health service systems. For example, the integration of preventive health screening services, together with the delivery of disease treatment services, may require not only the joint delivery of screening tests and medical treatment in one consultation, but may also require changes to human resources (who does what), drug supply systems (to provide the screening tests), and information systems (to allow for documentation of the integrated service) (WHO 2016). One example is the shift from vertical, stand‐alone delivery of priority disease programmes (such as HIV and tuberculosis (TB) services) to a more unified, integrated (horizontal) delivery of two or more disease programmes (such as integrating various elements of HIV and TB services for joint delivery at the point of care) (Kumar 2016; Oleribe 2015; Walley 2008).

Why is it important to do this scoping synthesis?

The evidence base on implementation and evaluation of PHC integration is large and diverse, including studies on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of different types of PHC integration. Healthcare workers may be involved with the implementation of PHC integration along the full continuum (from policy formulation to service delivery), and in different roles, as senior‐level decision‐makers, managers, and frontline implementers. Frontline healthcare managers and staff are also recipients of integration interventions that are planned higher up in management. Integration may have different meanings in different settings based on geographic, social, political, cultural, and historical contexts (Armitage 2009; Baxter 2018b). The role of context may also shape the design, delivery and implementation perceptions and experiences of PHC integration (Armitage 2009; Ryman 2012a).

Diverse understandings of what PHC integration is, and the diverse forms it can take, may influence healthcare workers' perceptions, and shape their responses and implementation experiences. Examining the perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers can help understand how they shape the implementation and delivery of PHC integration, and how contextual factors influence their responses. However, the heterogeneity of the evidence base complicates our efforts at understanding. Premature synthesis across the heterogeneous literature may lead to premature conclusions and missed opportunities to understand contextual influences.

This scoping review maps the qualitative literature on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences to characterise the evidence base, with a view to informing future evidence synthesis (Sutton 2019). The value of a scoping review prior to conducting further quantitative or QES is to identify and better understand heterogeneity in the evidence base. This can allow for more focussed research synthesis questions that take account of heterogeneity, as well as allow for more precise search terms or better sampling strategies.

Objectives

To map the qualitative literature on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of PHC integration to characterise the evidence base, with a view to better inform future syntheses on the topic.

To map the study characteristics in terms of the publication date and study design

To map the context of the studies in terms of geographical and service settings

-

To map the integration intervention characteristics in terms of the:

stakeholders (the client target population of the intervention and the healthcare workers who are the respondents in the study)

intervention components, including the health services that are being integrated, the scope of the integration intervention, and strategies used to deliver integrated services

To identify the conceptual models used in the studies

Review author reflexivity

Our review team have diverse backgrounds, which have likely shaped our contributions to the review. Our team consists of emerging and senior researchers in health policy and systems, public health, clinical research, and social sciences. As a team, we have skills in primary and secondary qualitative and quantitative research methods. Furthermore, four members of the review team have conducted and completed at least one full Cochrane QES study as lead or senior authors. All in our team have experience of research in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), and some team members have experience working for and with international health organisations, including the WHO. In the development of the QES protocol that preceded this scoping review (Moloi 2020), we included a public sector health policymaker and a mid‐level health service manager to help guide our thinking about information health authorities would find useful. This thinking also informed our approach to the scoping review.

This review team includes researchers based in South Africa and one review author from Kenya. The review question is of interest to the review team because both countries support different types of PHC integration. In South Africa, the National Department of Health has a record of health reforms that include PHC integration, especially for priority disease programmes such as HIV, TB, and mental health. In Kenya and South Africa, the delivery of PHC has often been characterised by successful priority health programmes that are delivered vertically (separately or in parallel to other PHC services), for example, immunisation, HIV prevention care and treatment, and most recently, the COVID‐19 response. However, to achieve UHC, Kenya and South Africa have embraced service integration within PHC to improve access to integrated PHC services.

Based on our collective and individual experiences and interests, both methodologically and in terms of content, we brought a richness of insights and a balance of views to conducting the review. The review authors are generally in agreement that PHC integration is potentially a useful tool for promoting UHC, while also being aware of the complexity of the intervention, and the importance of contextual influences. The team remained mindful of our presuppositions; we discussed these views, especially when faced with difficult judgements during the screening process. Through these discussions, we supported each other to minimise the risk of us skewing our analysis and interpretation of our findings. In the absence of standard definitions of PHC integration and related strategies, we often had to apply our judgement in categorising information for extraction. We consulted with each other and checked with a local policymaker (Tracey Naledi), to help us develop a common understanding of key areas.

Methods

Scoping reviews can be used to map a broad overview of the evidence on a topic, including identifying sources and types of evidence, clarifying key concepts and conceptual boundaries underpinning the topic area, and identifying gaps in evidence (Arksey 2005; Sutton 2019; Tricco 2016). The review objective is in line with that of scoping reviews, where the aim is 'to explore and define conceptual and logistic boundaries around a particular topic with a view to informing a future predetermined systematic review or primary research' (Sutton 2019). We used the 2020 JBI (formerly Joanna Briggs Institute) guide for scoping reviews (Peters 2015). Thus, for this scoping review, we include components such as the criteria for considering studies for this review, search methods for identification of studies, selection of studies, data extraction, management, and analysis. We describe these components in more detail below. There was no formal critical appraisal of the studies, as this is not required for scoping reviews (Tricco 2016). The review report is guided by the reporting format suggested in the PRISMA for Scoping Reviews extension (Page 2021; Tricco 2018).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Criteria for inclusion

Studies

We included primary studies that used qualitative study designs such as observational, cross‐sectional, case, and process evaluations study.

We included mixed methods studies (quantitative and qualitative methods) where it was possible to extract the data that were collected and analysed using qualitative methods.

Participants

-

We included studies that reported healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of PHC integration. We defined healthcare workers as:

clinical healthcare workers and lay healthcare workers (where the lay healthcare workers were classified as healthcare workers rather than volunteers), on both healthcare provision and management levels;

other individuals involved in supporting the provision and management of PHC integration interventions. These individuals could include administrative, managerial, supervisory staff, advisors, and policymakers.

Interventions

We included PHC integration interventions that had a focus on PHC‐level services, including community‐based services.

-

This could have included a range of integration‐type interventions such as:

horizontal integration of previously vertical programmes;

multidisciplinary teams working together to deliver more integrated care;

health systems functions combined (i.e. human resource and finance systems) to deliver more integrated management of disease programmes;

expansion of services towards more comprehensive care (e.g. adding a new service to an existing disease programme, such as screening for non‐communicable diseases (NCDs) in HIV/TB care). Or introducing a new PHC service that was previously delivered at a specialist level (e.g. such as PHC‐based follow‐up for cancer care clients that are now being delivered by general or specialised nurses in a PHC setting);

integration interventions that differ in scale and scope. These could be on a continuum from full to partial integration efforts. There are no standard definitions for full or partial integration. We made judgements based on the extent to which the intervention aimed to deliver integrated clinical services at the point of care, and the extent to which healthcare service support functions were integrated into support of that integrated clinical service. We also considered the extent to which the integrated service delivery was embedded in existing general PHC services, versus the need for additional, specialised staff to deliver integrated services at the PHC level. For full integration, for example, we considered the extent of integration of health service support functions, such as management, finances, human resources, information systems, and supply systems. Where a new service was devolved from the hospital for delivery at the PHC level, we considered the extent of efforts to embed the new service within existing generalised PHC staff skills and capacity, or whether a new or specialised cadre of healthcare workers was required to deliver the service at PHC level.

Settings

We defined PHC services as including all therapeutic, preventive, promotive, and rehabilitation services delivered at the first contact point of healthcare (Awofeso 2004), including at the level of PHC and community‐based healthcare (Muldoon 2006).

We included studies of PHC integration in public and private healthcare settings and public–private partnerships.

We included studies of PHC integration in any country and both rural and urban settings.

Criteria for exclusion

Studies

Hypothetical studies (planned, modelled, but not implemented and evaluated), for example, where there was a situational analysis or healthcare workers were asked about the feasibility of providing integrated services (planned, anticipated) in the absence of actual implementation of such integrated services.

We excluded studies that collected data using qualitative methods but did not analyse these data using qualitative analysis methods (e.g. open‐ended survey questions where the response data were analysed using descriptive statistics only).

Participants

We excluded studies that did not report on healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of being involved in PHC integration or if it was not possible to separate the data on the views and experiences of healthcare workers from the views and experiences of other stakeholders.

Interventions

Transitional care between PHC and levels above (hospital, secondary), for example, a referral from PHC to secondary care or discharge from secondary care to PHC. This includes services around emergency care services where linkages are required between PHC and hospital care. Improved referral services could be considered part of designing integrated services, but given the additional layer of complexity around interorganisational linkages, we consider this warrants a separate review.

Integration of non‐health programmes with PHC health programmes. We excluded all programmes addressing social determinants of health (e.g. social services, social protection, nutrition, safety, housing, and legal help). We recognised that certain conditions related to social dynamics and social determinants require a non‐medical intervention, such as housing and employment. This may warrant a separate review.

Digital tools being evaluated in PHC, where the digital tool intervention was not the key element of facilitating the PHC integration intervention.

Training of health workers for PHC integration. We excluded evaluation of training for PHC integration unless it was also linked to evaluating the health workers' experience of implementing PHC integration.

'Care co‐ordination' strategies, where the core intervention was one person co‐ordinating care for a group of clients for a specific area (e.g. elder care). We recognise that care co‐ordination is a specific and widespread intervention strategy with its own set of variations, and feel this may warrant a separate review.

We excluded alternative medicine interventions. Alternative medicine refers to a broad set of practices that a country may not consider mainstream biomedical/clinical medicine and this includes traditional, faith healing, and Chinese medicine. We excluded these as they are not central to the focus of our review and may warrant a separate review.

Settings

Inpatient community‐based services, for example, drug rehabilitation centres, step‐down physical rehabilitation, and hospice centre for inpatient palliative care.

Non‐health delivery site, that is, integration occurring in schools, jails, retirement complexes/nursing homes, workplace health services, and home‐based care.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Information Specialist developed the search strategies for different databases in consultation with our scoping review team. To develop the search strategy, we used the PI (Phenomenon of Interest) and the R (Research type) from the SPIDER framework to develop the MEDLINE search strategy (www.nccmt.ca/knowlege-repositories/search/191). We did not use the S (Sample), as the scoping review included health workers (professionals and non‐professionals).

We did not apply geographic location limits and language limits, and we searched all databases from 1948 to the date the search was conducted. This date range was used to include health workers' experiences and perceptions since the Alma Ata declaration on PHC (WHO 1987). The search was completed on 15 February 2020 and reran to update the results on 28 July 2020. Appendix 1 shows the MEDLINE search strategy, which we adapted for other databases.

Electronic searches

We searched PDQ‐Evidence, Epistemonikos Foundation, for related reviews to identify eligible studies for inclusion (www.PDQ-evidence.org/), and the following electronic databases on 28 July 2020.

MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions 1946 to 24 July 2020, Ovid

CINAHL from 1981, EBSCOhost

Scopus Elsevier

Global Index Medicus, WHO

Grey literature

We found an extensive peer‐reviewed dataset from our database search. Thus, we did not conduct a grey literature search to identify studies not indexed in the databases. Also given a large number of records included, we did not screen the reference list of included studies to identify more records.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified records to evaluate eligibility, and a third review author resolved conflicts. We retrieved the full text of the titles and abstracts identified as potentially eligible. Two review authors independently assessed the full‐text articles, and a third review author resolved conflicts. All review authors participated in at least one online training and practice session (led by HM or NL, or both), prior to abstract and full‐text screening, to ensure a standard approach to screening.

Where multiple publications reported on the same intervention study, we collated these publications (and treated them as one data source), so that each unique intervention (rather than each publication/study) was the unit of interest for analysis.

We included a PRISMA flow diagram to show our search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion. Additionally, we included a table of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion.

Translation of languages other than English

We considered all studies regardless of the language of publication. We found 17 non‐English studies: three in French, two in German, one in Japanese, one in Italian, eight in Portuguese, and two in Spanish.

We performed an initial translation through open‐source software (Google Translate) for all the titles and abstracts of studies not published in English. If Google translation was not sufficient to decide on inclusion or exclusion, we asked members of Cochrane networks, Social Science Approaches for Research and Engagement in Health Policy and Systems (SHAPES) networks, or other networks that are proficient in that language to assist us. We received translation assistance from six SHAPES network members.

From the translated studies, if this translation indicated inclusion, or if the translation was too limited to inform a decision, we retrieved the full text of the paper. We followed the same process for translating and screening the full text. For all studies included after the full‐text screening, we used Google Translate and also asked members of the SHAPES network proficient in that language to translate key information items needed for data extraction. If we could not do this for a study in a particular language, we listed the study as 'studies awaiting classification' to ensure transparency in the review process.

Data extraction

Two review authors (HM and NL) extracted data. We used a customised data extraction form with items for data extraction and sorting. We expanded the form with further subcategories based on emerging data. Table 1 shows items extracted and their subcategories. We used a combination of an inductive and deductive approach to data extraction and synthesis. We drew lightly on two frameworks to identify useful categories for data extraction. The SURE framework on implementation factors, guided us to identify data on key stakeholders, such as the providers and recipients of care, and the care setting (Sure Collaboration 2011). The Health Systems framework guided us to identify different health systems functions that were being integrated, such as human resources, information systems, and supply systems (van Olmen 2010). We also drew on various sources of taxonomies for integrated care to guide the categorisation of intervention type, scope, breadth, and strategies (Atun 2004; Kodner 2002; Valentijn 2015). Given the plethora of definitional sources, we adapted these a priori concepts on type, scope, and strategies as part of our deductive approach to data extraction. In places where there were no predefined definitional categories, we used an inductive approach based on emerging data, as in the case of identifying the health stream configurations.

1. Items extracted and their subcategories.

| 1. Study ID: author – publication, date, title, aim 2. Study methods: study design, data source 3. Setting: income level, country, urban/rural, healthcare level 4. Target client population to receive the intervention 5. Research participants 6. The intervention description: 6.1. Health service streams that were being integrated 6.2. The scope of the integration intervention (e.g. full or partial) 6.3. Intervention strategies used 7. Conceptual models used in the study |

For consistency between the review authors, HM and NL initially performed duplicate extraction on a sample of 10 studies (5%) and compared their data. The duplicate extraction process continued for another 10 studies (in total 10%) until there was sufficient agreement for single review author extraction. As an additional quality check, the senior author (NL) reviewed the data extraction of 40 studies (22% of the total sample) completed by HM.

Management and analysis

We imported and managed all the retrieved studies in Covidence (www.covidence.org). We screened and assessed the eligibility of all retrieved studies in Covidence.

After data extraction into our Excel template, we refined the extraction by providing drop‐down lists for subcategories for some of the indicators. For example, categorising country‐income levels, health stream interventions, and intervention scope and strategies. We then used the sorting function in Excel to present the information quantitatively by counting the number of studies per indicator and converting these into proportions. Where relevant, we provided additional qualitative descriptive information. Where appropriate, we disaggregated indicators per country income level. Below we provide details on how we analysed and categorised information for the indicators for research participants, intervention descriptions, and conceptual models.

Research participants

Studies listed a wide range of research participants who provided information on their perceptions and experiences of being involved in implementing integration interventions. We categorised these research participants as follows: policymakers and provincial managers, district managers, clinical managers, clinical healthcare workers, allied healthcare workers, lay healthcare workers, health systems support staff, civil society (i.e. community leaders and chiefs involved in clinic decisions) and health system advisors (researchers, programme managers, non‐governmental organisation (NGO) managers, technical advisors, and operational managers).

Intervention

Health service streams that were integrated

In the literature, we found no predefined, standardised PHC integration intervention categories to describe combinations of health programmes that were being integrated. We created categories based on emerging data. Six categories of health service stream configurations emerged from the analysis.

Mental and behavioural health services

HIV, TB, and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services

Maternal, child, and women's health (MCWH) services

NCD services

General PHC services

Allied and specialised health services

Some interventions overlapped across the health service streams listed above, and we placed them in the stream where we thought they would fit best. For example, where a mental and behavioural health service was being integrated into an NCD service, we placed it in either the 'Mental and behavioural health service' or the 'NCD service' stream, depending on our assessment of the primary aim and direction of integration for joint service delivery. We used the category of 'General PHC services' for interventions that went beyond the integration of clinical components of health programmes, to focus more explicitly on the integration of cross‐cutting health system functions (such as the functions of management and administration, human resources, or health information systems), as well as integrated interventions that did not easily fit under the other categories. In 'Allied and specialised health services', we highlighted the introduction at the PHC level, of previously specialised services (such as dental services) and services delivered by allied health professionals (e.g. occupational therapists).

Scope of the integration

When we analysed the interventions included in this scoping review, we found a continuum in terms of the scope of health services (e.g. the number and extent of clinical tasks being integrated for joint delivery). There was also a continuum regarding the extent to which cross‐cutting (transversal) health system functions were integrated to enable joint delivery of care (e.g. financial systems, human resource management, information systems, and supply systems). Based on the analysis of the included studies, and drawing on concepts in the literature, we categorised interventions as having a full or partial integration scope, as described below.

Full integration scope

We defined this as the integrated delivery of two or more PHC service programmes previously delivered vertically or in silos (e.g. joint delivery of HIV and TB services), or where there is a substantial expansion of a health service for integrated delivery at PHC level. One example is devolving mental health services from specialised care level to the PHC level in a way that mental health is more fully integrated with the delivery of other PHC services. Another example is where multiple PHC service organisations co‐ordinate and interlink their service delivery for general PHC clients or for a specified target group, such as maternal and child health. For instance, this could be done through the colocation of health services within one facility.

Partial integration scope

This is where only one or a small component of a health service or clinical task is integrated or a limited number of clinical (e.g. disease screening for TB) to a different (main) health service (e.g. HIV treatment services). We refer to this as 'partial integration' to indicate that only a part of the health service (and not all the health service/clinical tasks for that disease programme) were delivered jointly. Another element is when the service is devolved from specialised services to PHC level but is not fully embedded for integrated delivery by general PHC staff. For instance, when specialised staff are employed at the PHC level to deliver a previously specialised service, such as mental health care.

In some studies, the integration scope represented a mix of full and partial integration efforts. The intervention descriptions were not always sufficiently detailed to make well‐informed judgements about its scope. Also, there are no standard definitions of full and partial integration. Therefore, we considered these tentative classifications to provide an initial map of the scope of integration interventions.

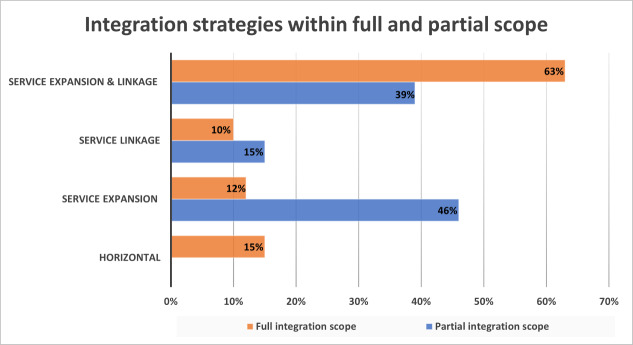

Intervention strategies used

Through an analysis of the included studies, we ascertained that within both full and partial integration, the interventions also differed in terms of the main strategies used for the delivery of integrated care. We did not find standardised categories of service strategies in the literature, so we categorised strategies based on data emerging from our analysis. Table 2 provides a list of the categories of integration strategies we identified.

2. Integration strategies within full and partial integration.

| Full integration |

| 1. Horizontal integration strategy |

| 2. Service expansion strategy |

| 3. Service linkage strategy |

| 4. Service expansion and linkage strategy |

| Partial integration |

| 1. Service expansion strategy |

| 2. Service linkage strategy |

| 3. Service expansion and linkage strategy |

We categorised integration interventions as 'service linkage' when the focus was on linkages between clinical staff in different health services. An example included liaison amongst healthcare workers, or amongst PHC service organisations, delivering different NCDs services, or between different PHC service platforms such as health facility‐based and community‐based service platforms. We categorised integration strategies as 'service expansion' when the focus was on expanding a component of one health service and adding it as standard care in another health programme (e.g. NCDs risk screening for HIV clients). Some integration interventions used a combination of service linkage and service expansion strategies. In full integration, we added a third strategy, named 'horizontal integration'. This is where two or more previously verticalised PHC health services were amalgamated for joint delivery into one health programme. For example, previously verticalised HIV and TB services were now being delivered jointly. The integration scope here is assumed to be wide and to include the integration of supportive health system functions (e.g. financing, human resources management, health information systems, and supply systems).

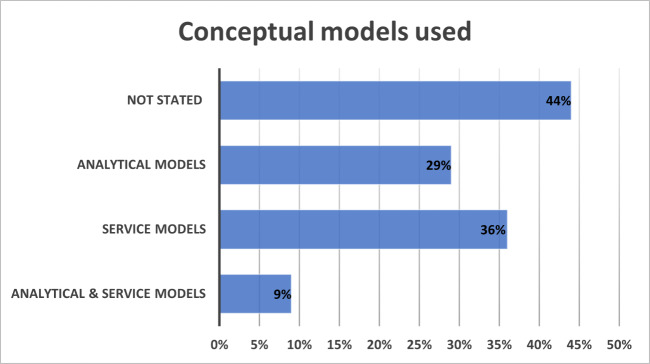

Conceptual frameworks used

We were interested in extracting data on whether an analytical, conceptual model was used to guide the study design, implementation, and evaluation. The assumption was that the use of analytical models in studies may potentially produce deeper conceptual or theoretical insights, as well as promote comparability between study findings. To extract data on analytical models, we used the 'Find' function in the PDF programme to search in the text of each study for the following keywords: 'conceptual', 'framework', 'model', and 'theoretical'. We found that these terms were sometimes used to describe not only analytical models but also for describing a particular model of the PHC integration intervention that was being implemented (e.g. the Chronic care model). We labelled the latter as 'service models' to indicate that it focused only on describing the integration intervention, and not on guiding the evaluation. Therefore, we reported on the use of both analytical and service models. Analytical models include named frameworks (e.g. integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i‐PARIHS) framework, and theories, such as Complexity theory).

On a different note, studies also sometimes used terms such as model, framework, or theory, to describe their methodological approach to qualitative data analysis (e.g. 'thematic framework' or grounded theory). We excluded these from our analysis as these are methodological approaches rather than models.

Summary of key characteristics of included studies

We presented a summary of the 'Key characteristics of included studies' in a table that combines study characteristics and key findings. We did not present our findings in the 'Summary of qualitative findings' table as these are scoping review findings that are presented as indicators, with supporting data tables. We did not conduct a critical appraisal of included studies. Scoping reviews do not typically analyse and appraise the data of included studies; rather they provide a map or detailed description of the scope of studies (Peters 2015).

The key items listed in our key characteristics table are author, publication date, study design, country income level, country name, target client population to receive the intervention, research participants, health service streams, scope of integration, and intervention strategies used.

Linking the synthesised qualitative findings to a Cochrane intervention review

The findings of this scoping review were not intended to be integrated with the Cochrane intervention review on PHC integration. Nevertheless, findings from the scoping review could inform future updates of the Cochrane integration effects review (Dudley 2011). Findings can also inform future quantitative and qualitative synthesis questions that take account of the heterogeneity of the evidence, and by informing more approaches to developing search terms and sampling strategies.

Results

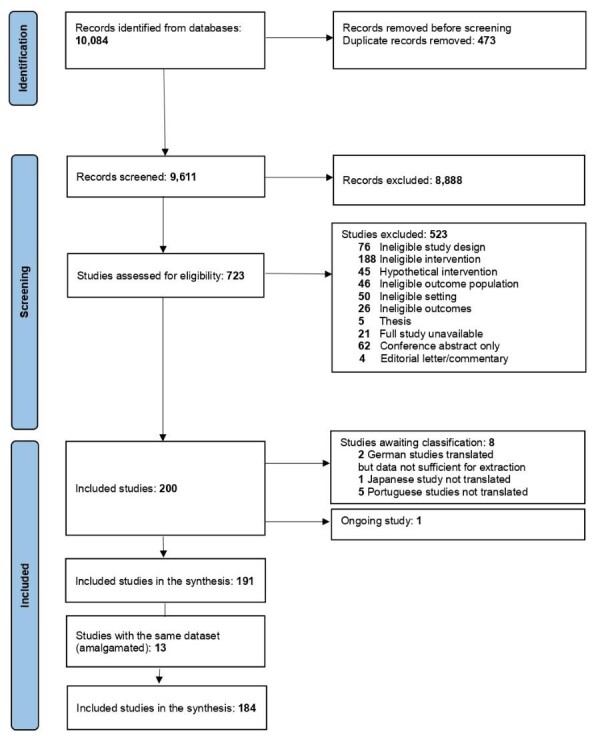

Results of the search

We detailed the literature search results according to the PRISMA Statement. Figure 1 shows that we retrieved 10,084 records from searching the electronic databases. After removing duplicates, we assessed 9611 records for eligibility based on title and abstract. We assess the full texts of 723 records, and removed 523 records with reasons for exclusion. Due to many excluded studies, we presented a sample of 63 (12%) excluded studies with reasons in Table 3. We selected these studies by categorising all excluded studies alphabetically and then picked a sample of studies, from the topic of the alphabetical list, under each of the different exclusion criteria categories. The exclusion categories for the sample we describe were: ineligible study design (nine studies), ineligible intervention (18), hypothetical intervention (nine), ineligible outcome population (nine), ineligible setting (nine), and ineligible outcomes (nine).

1.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

3. Characteristics of excluded studies.

Thirteen publications had the same intervention found in at least one other publication. Publications with the same intervention were amalgamated, which resulted in six publications with unique intervention studies. Thus, 184 studies with a unique intervention, based on 191 papers, were analysed in this scoping review.

Eight studies are awaiting classification, and one study is ongoing.

Key characteristics of included studies

Table 4 provides a summary of the key characteristics of included studies. The table contains the following details: author and publication date, study design, country‐income level, country name, client target group, research participants, health service streams integrated, integration type/scope and integration strategy.

4. Key characteristics of included studies and key indicators.

| Author, publication date | Study design | Country income level | Country | Patient target group | Research participants | Health service streams integrated |

Integration type and scope (FI or PI) |

| Aantjes 2014 | Mixed methods | LMIC | Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, Ethiopia | General PHC and HIV patients |

|

HIV, TB, SRH | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Acri 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Children 5–18 years old |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Aerts 2020 | Qualitative | HIC | Belgium | PHC patients with chronic disease |

|

NCDs | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Aitken 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Akatukwasa 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | Uganda | Youth with SRH service needs |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Aleluia 2017 | Qualitative | MIC | Brazil | PHC patients with diabetes and hypertension |

|

NCDs | FI: service linkage |

| Allen 1997 | Mixed methods | HIC | New Zealand | Community members and patients in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Allen 2007 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | Population who utilises acute and community health services |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service linkage |

| Allen 2015 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Community members with chronic disease needs community members with high care needs |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion |

| Ameh 2017 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with chronic diseases |

|

NCDs | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Amo‐Adjei 2014 | Qualitative | MIC | Ghana | People with TB |

|

HIV, TB, SRH | FI: horizontal |

| An 2015a; An 2015b | Mixed methods | MIC | Tanzania | Women attending antenatal care |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | Mixed: FI + PI |

| Anand 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | India | People with TB |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion |

| Anku 2020 | Qualitative | MIC | Ghana | People with TB or HIV, or both |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Athié 2016 | Mixed methods | MIC | Brazil | General PHC patients |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ayon 2019 | Mixed methods | MIC | Kenya | Women who inject drugs |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Baker 2007 | Mixed methods | MIC | Dominican Republic | Lymphatic filariasis patients |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion |

| Baker 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | Tanzania | Patients accessing maternal and newborn services at PHC and hospitals |

|

MCWH | PI: service linkage |

| Banfield 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | PHC patients, especially patients at risk for NCDs, seeking care via the public‐private partnership |

|

NCDs | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Beckingsale 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | New Zealand | People with chronic diseases |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Beehler 2017 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People with mental health problems |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Beere 2019 | Mixed methods | HIC | Australia | People with mental health problems |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Benjumea‐Bedoya 2019 | Mixed methods | HIC | Canada | Refugees in need of TB services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Benson 2018 | Mixed methods | HIC | Australia | People with complex medication regimens or multiple comorbidities, or both |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Bentham 2015 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People in need of anxiety and depression services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Bentley 2015 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Aged care patients in PHC or GP practices |

|

PHC and other services | PI: service linkage |

| Berkel 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | All PHC patients |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Bernard 2016 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People living with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Billings 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | PHC facility, community service and home care service users |

|

PHC and other services | FI: horizontal |

| Blasi 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | PHC patients with behavioural health needs, including support for managing of chronic disease |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Bradley 2008 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | All PHC patients – for medication review |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Brooks 2020 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with substance use disorder seeking care in outpatient PHC settings |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Burgess 2016 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with mental health needs |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Busch 2013 | Qualitative | HIC | Netherlands | New parents and their children |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Busetto 2015 | Qualitative | HIC | Netherlands | People with diabetes and geriatric chronic care patients |

|

NCDs | FI: service expansion + linkage |

| Butler 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with mental health needs receiving care at PHC level |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Carman 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | All PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Church 2015 | Mixed methods | MIC | Eswatini | People with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | Mixed: FI + PI |

| Cifuentes 2015 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People with behavioural health |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Clark 2017; Davis 2015; Gunn 2015 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Health users in PHC with behavioural and mental health needs |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Cole 2015 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Uninsured patients in PHC services |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Cooper 2020 | Mixed methods | LIC | Malawi | Mother bringing in their children for immunisation Mothers who were seeking family planning |

|

MCWH | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Dayton 2019 | Mixed methods | MIC | Dominican Republic | People using HIV services especially those vulnerable to gender‐based violence, e.g. men who had sex with men, commercial sex workers, transgender people |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| De Lusignan 2020 | Mixed methods | HIC | UK | People suspected to have influenza |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion |

| De Nóbrega 2014 | Qualitative | MIC | Brazil | Men |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Derrett 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Rural patients accessing PHC services |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Donnelly 2013 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | PHC patients |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Douglas 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | People using geriatric care at PHC level |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Duma 2019 | Qualitative | LIC | Malawi | Women in need of HIV or SRH (or both) services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Dunbar 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People using mental health services at PHC and community‐based centre level |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Edelman 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Fitzpatrick 2017; Fitzpatrick 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | People with mental health problems in rural areas |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion |

| Fleury 2016 | Mixed methods | HIC | Canada | People with mental health problems in primary care |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion |

| Fong 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | General paediatric population in need of behavioural health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion |

| Foster 2009 | Mixed methods | HIC | Australia | People receiving chronic care treatment by general practitioners |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion |

| Foster 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | People with complex diabetes |

|

NCDs | FI: service expansion |

| Gadomski 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Children and adolescents |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Gavin 2008 | Qualitative | HIC | Ireland | PHC patients with mental health needs – for detecting people with serious mental health disease (psychosis) |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Gear 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | New Zealand | People in need of family violence services at PHC level |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Geelhoed 2013 | Mixed methods | LIC | Mozambique | Mothers who accessing maternal and child healthcare services |

|

MCWH | FI: horizontal |

| Gerber 2018 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | People in need of mental healthcare care services in PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Gerrish 1999 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ghorbani 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | Iran | Mothers and children needing access to oral health care at PHC level |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion |

| Glasgow 2012 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People with diabetes in PHC |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion |

| Greene 2016 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Children in paediatric care services who need access to mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service linkage |

| Gucciardi 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | People with diabetes at PHC |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Haddow 2007 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | PHC patients requiring assistance with accessing unscheduled health care at PHC and hospital levels |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service linkage |

| Harnagea 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | Children in need of oral care |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Hepworth 2015 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in need of mental health and chronic disease services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Hlongwa 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Hunter 2018 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People in need of substance use disorder services in PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion |

| Ion 2017 | Mixed methods | HIC | Canada | People in need of mental health care at PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Jacobs 2012 | Qualitative | MIC | Lao | Mothers and children accessing immunisation and mother and child health services |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Jauregui 2016 | Mixed methods | HIC | Spain | People in chronic care with multimorbidity |

|

NCDs | PI: service Linkage |

| Jewett 2013 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People in need of hepatitis C virus services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Johnson 2020 | Qualitative | MIC | India | People with diabetes in need of mental health services for depression |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Jorgenson 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | People in need of medication review |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Kawonga 2016 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Khan 2018 | Mixed methods | MIC | Pakistan | PHC patients using hypertension care services |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Kirchner 2004 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health and substance use services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Lane 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | PHC patients in need of comprehensive clinical and allied medicine care |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Langer 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in PHC in need of psychosocial and mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Lawn 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | All PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Limbani 2019 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | People with chronic illnesses in rural PHC |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Lombard 2009 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People diagnosed with HIV, sexual abuse, and mental illness |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Lovero 2019 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | People with TB and people in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Lucas 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | Australia | People with chronic disease at PHC facilities and community‐based services |

|

NCDs | PI: service linkage |

| Ma 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Asian‐American immigrants attending PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Main 2007 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | People visiting general PHC and general practitioners |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion |

| Malachowski 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | People with mental health care needs |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Marais 2015 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with mental health care needs in PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion |

| Martin 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | Kenya | Pregnant women receiving antenatal care |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Mathibe 2015 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV receiving antiretroviral treatment |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | Mixed: FI + PI |

| Mayer 2016 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with diabetes and other chronic disease receiving care in PHC and community centres |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion |

| McGeehan 2007 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | General PHC patients |

|

NCDs | PI: service linkage |

| McNamara 2020 | Mixed methods | HIC | Australia | Adults in the community not diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, and not being treated for hypertension or lipid disorders |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Meyer‐Kalos 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with severe mental illness |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Miguel‐Esponda 2020 | Mixed methods | MIC | Mexico | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: horizontal |

| Mishra 2014 | Qualitative | MIC | India | Rural poor, women, and children |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Mugisha 2016 | Qualitative | LIC | Uganda | People with mental health problems in PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and Linkage |

| Mulenga 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | Democratic Republic of the Congo | People attending basic care services who might need Human African trypanosomiasis services |

|

PHC, allied or and specialised services | Mixed: FI and PI |

| Murphy 2018 | Mixed methods | MIC | Vietnam | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Mutabazi 2020 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | Maternal health service users in PHC |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Mutemwa 2013 | Qualitative | MIC | Kenya | People coming for family planning and postnatal care |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Mykhalovskiy 2009 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | People with HIV (for HIV prevention) |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ndwiga 2014 | Qualitative | MIC | Kenya | People with HIV and reproductive health |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Nelson 2019 | Qualitative | LIC | Liberia | Mothers using child vaccination services |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Newell 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | Ireland | People with diabetes in PHC |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Newmann 2013 | Mixed methods | MIC | Kenya | HIV positive men and women accessing family planning services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Newmann 2016 | Mixed methods | MIC | Kenya | People in need of family planning and HIV services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Nooteboom 2020 | Qualitative | HIC | Netherlands | Highly vulnerable families |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service linkage |

| Norfleet 2016 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Nxumalo 2013 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Oishi 2003 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ojikutu 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service linkage |

| Okot‐Chono 2009 | Qualitative | LIC | Uganda | People with HIV or TB |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Oliff 2003 | Qualitative | MIC | Tanzania | People in need of maternal and reproductive care |

|

MCWH | FI: horizontal |

| Patwa 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV and the general population using the PHC services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: service expansion |

| Payne 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion |

| Peer 2020 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | People with both HIV and hypertension |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Pereira 2011 | Qualitative | MIC | India | People in need of common mental health disorder treatment |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Petersen 2009 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Petersen 2011 | Qualitative | LMIC | Uganda, South Africa | People in need of mental health services Uganda – people in need of severe mental health services South Africa – people in need of depression services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Petersen 2019 | Qualitative | LMIC | Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | Mixed: FI + PI |

| Pfitzer 2019 | Mixed methods | LMIC | Kenya and India | Pregnant women and postpartum women |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Peer 2020; Pidano 2011 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Children in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service linkage |

| Piper 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | PHC and community‐based health users |

|

PHC and Other services | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Piper 2020 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People with HIV |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Porter 2002 | Qualitative | MIC | India | People in need of TB services and leprosy services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Ramanuj 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Reinschmidt 2017 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with both mental health and chronic care needs |

|

NCDs | PI: service expansion |

| Rissi 2015 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Community |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Robertson 2018 | Qualitative | LIC | Malawi | Children aged under 5 years in need of medical care |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Rodriguez 2006 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | Diabetes patients |

|

NCDs | PI: service linkage |

| Rodriguez 2019 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Latin children in need of mental healthcare |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service Linkage |

| Rojas 2015 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | Latino and African American adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes |

|

NCDs | PI: service linkage |

| Ross 2000 | Mixed methods | HIC | UK | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ryman 2012b | Qualitative | LMIC | Kenya, Mali, Cameroon, and Ethiopia | Mothers taking their children for vaccination in PHC |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Ryman 2012c | Mixed methods | MIC | Kenya | Children receiving immunisation at the clinic |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Sakeah 2014 | Qualitative | MIC | Ghana | Woman in labour |

|

MCWH | PI: service expansion |

| Sheth 2020 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Adolescent and adult women |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Savickas 2020 | Qualitative | HIC | UK | People with long‐term illnesses |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Shattell 2011 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with severe mental illness |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Shelley 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | Tanzania | Mothers with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Shin 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | South Korea | People with disabilities |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Shrivastava 2020a; Shrivastava 2020b | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | People in need of oral care |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Siantz 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People with mental health problems |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Sieverding 2016 | Qualitative | MIC | Nigeria | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | PI: service expansion |

| Sinai 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV with suspected latent TB |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Smit 2012 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Sobo 2008 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People at risk of HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Souza 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | Brazil | People with mental health problems in PHC |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Souza Gleriano 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | Brazil | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Ssebunnya 2010 | Qualitative | LIC | Uganda | People in need of PHC services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Stadnick 2020 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Children with autism |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion and linkage |

| Surjaningrum 2018 | Qualitative | MIC | Indonesia | Pregnant women and women who recently gave birth |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Terry 2018 | Qualitative | HIC | USA | People needing services for mental health, cognitive impairment, and substance abuse |

|

Mental and behavioural health | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Topp 2010 | Mixed methods | MIC | Zambia | People with HIV and people attending outpatients |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Topp 2013 | Mixed methods | MIC | Zambia | People with HIV and general patients attending outpatient |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: horizontal |

| Treloar 2014 | Qualitative | HIC | New Zealand | People with hepatitis C |

|

PHC and other services | PI: service linkage |

| Tsasis 2012 | Qualitative | HIC | Canada | General PHC patients |

|

PHC and other services | FI: service expansion and linkage |

| Tshililo 2019 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People needing HIV/AIDS services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | FI: service linkage |

| Tsui 2018 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | Long‐term cancer survivors |

|

PHC, allied and specialised services | PI: service linkage |

| Uebel 2013 | Qualitative | MIC | South Africa | People with HIV |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |

| Urada 2014 | Mixed methods | HIC | USA | People in need of mental health and substance use disorder services |

|

Mental and behavioural health | PI: service expansion |

| Uwimana 2013 | Mixed methods | MIC | South Africa | Pregnant woman attending prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission/antenatal services |

|

HIV, TB, and SRH | PI: service expansion |