Abstract

Objective

Bipolar disorder often co-occurs with post-traumatic stress disorder, yet few studies have investigated the impact of post-traumatic stress disorder in bipolar disorder on treatment outcomes. The aim of this sub-analysis was to explore symptoms and functioning outcomes between those with bipolar disorder alone and those with comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Methods

Participants (n = 148) with bipolar depression were randomised to (i) N-acetylcysteine alone; (ii) a combination of nutraceuticals; (iii) or placebo (in addition to treatment as usual) for 16 weeks (+4 weeks discontinuation). Differences between bipolar disorder and comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder on symptoms and functioning at five timepoints, as well as on the rate of change from baseline to week 16 and baseline to week 20, were examined.

Results

There were no baseline differences between bipolar disorder alone and comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder apart from the bipolar disorder alone group being significantly more likely to be married (p = 0.01). There were also no significant differences between bipolar disorder alone and comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder on symptoms and functioning.

Conclusion

There were no differences in clinical outcomes over time within the context of an adjunctive randomised controlled trial between those with bipolar disorder alone compared to those with comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. However, differences in psychosocial factors may provide targets for areas of specific support for people with comorbid bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder; Depression; Psychiatry; Comorbidity; Stress disorders, post-traumatic

INTRODUCTION

Comorbidities such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are highly prevalent in people with bipolar disorder (BD) [1,2]. People who experience psychiatric comorbidities may present with a more chronic and severe clinical course than those with a single psychiatric disorder [3,4]. Those with comorbid BD and PTSD (BD + PTSD) have been shown to experience a decreased quality of life compared to people with either disorder alone [5,6]. They also experience a greater frequency of rapid mood cycling, mood instability, suicide attempts [6,7], and poorer social and occupational functioning, compared to those with BD alone [4,8].

Additionally, rates of PTSD are higher in those with BD than in the general population, with estimates ranging between 7% to 55% [2,5,9-11]. Several hypotheses have been explored to explain the high rates of PTSD within BD. The increased risk of exposure to traumatic situations during a manic or psychotic episode is characteristic of BD [11,12]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that those with serious mental illness and PTSD may be more likely to develop psychotic symptoms when experiencing intrusive memories, nightmares, and flashbacks [12,13].

There is some symptomatic overlap between BD and PTSD, including; mood swings, hopelessness, inhibition, anhedonia, inner tension, sleep disturbance, irritability, difficulty concentrating, hyperarousal, and relationship difficulties [10,14]. This overlap may lead to both misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of either disorder. Further-more, PTSD symptoms such as avoidance may increase the risk of experiencing a BD mood episode via increased social isolation and decreased support seeking behaviours, negatively impacting BD maintenance [10]. Moreover, the environmental cues (or triggers) associated with PTSD can drive emotional lability and may evoke sudden panic, distress or avoidance; this may induce a hypomanic or manic BD mood episode [11].

Data from several cross-sectional studies suggest that people with BD + PTSD have poorer outcomes compared to those with BD alone. A large cross-sectional study investigating comorbid anxiety disorders in the first 500 participants from the Systematic Treatment Enhance-ment Program for Bipolar Disorder [15] study recorded an increased risk of suicide attempts in comorbid BD and PTSD compared to other comorbid anxiety disorders [15]. Quarantini and colleagues [6] similarly found that those with BD + PTSD have an increased suicide risk than those with BD alone. A cross-sectional study was conducted on the impact of PTSD in BD patients (n = 355) recruited from teaching hospitals. Participants were divided into three groups, BD + PTSD (n = 40), BD exposed to trauma without PTSD (n = 60) and BD with no trauma or PTSD (n = 254). The BD + PTSD group reported poorer quality of life, increased rapid cycling, a lower likelihood of staying recovered, and higher rates of suicide attempts, in contrast to the BD with trauma without PTSD and BD with no trauma or PTSD [6]. These results are similar to those reported in a cross-sectional study of primary care patients [16]. Ninety-six participants with BD and 30 participants with BD + PTSD were assessed on depression, mania, and functioning measures. Comorbid BD + PTSD led to significant impairments in social functioning including work loss, and worse physical and mental health-related quality of life, compared to those with BD alone [16].

To date, two studies have investigated pharmacological treatment outcomes in those with BD + PTSD. A recent study on childhood trauma including PTSD reported treatment outcomes in lithium response rates in 135 participants with BD type 1 (BD I) [17]. Those with comorbid BD and PTSD had significantly lower lithium response rates than those with BD alone [17]. Additionally, a pharmacogenetics study of lithium response of 184 participants with BD I, Bipolar disorder II or schizoaffective bipolar type, supports these results [18]. Participants with BD + PTSD had a lower lithium response rate compared to those with BD alone [18].

Taken together, the literature highlights the high prevalence rates of PTSD in BD and the more severe clinical course of those with BD + PTSD. This data provides a hinge point for future research to build on to better inform pharmacological treatments and outcomes for comorbid BD and PTSD. The aim of this paper was to compare BD alone and BD + PTSD treatment outcomes using data from an adjunctive nutraceutical trial (of mitochondrial enhancers including N-acetylcysteine [NAC] vs. NAC alone vs. placebo) [19]. The adjunctive nutraceutical trial [19] found no significant between-group differences on change scores from baseline to week 16 on any clinical or functional measures, one hypothesis that emerged was the mediating effects of a comorbid diagnosis, such as PTSD, on treatment outcomes. This paper aims to determine whe-ther comorbid PTSD impacted on outcomes (depression, mania, and functioning) of individuals with bipolar de-pression.

METHODS

Study Design

In this study we utilised data from a multi-site, three- arm double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating 16 weeks treatment (plus a week 20 visit, 4 weeks post-discontinuation) of mitochondrial enhancers including NAC vs. NAC alone vs. placebo in participants with bipolar depression [19]. The primary outcome of the RCT was change in depression score from baseline to week 16. The secondary outcomes were measures of mania and functioning. Results of the RCT showed no treatment group differences over time, however all participants showed improvement from baseline to follow-up and at post-discontinuation visit. Further details of the design and rationale have been published [19,20]. Participants provided written and verbal informed consent. Approval was received from Northern Sydney Local Health District HREC (Human Research Ethics Committee), The Melbourne Clinic Research Ethics Committee for the adjunctive nutraceutical trial. The trial was prospectively registered (ANZCTR: ACTRN12612000830897). This study received Deakin University ethics approval (reference number: 2012-138) and Barwon Health HREC approval (reference number 11/10).

Participants

One hundred and eighty-one participants were included in the original RCT, recruited from three Australian sites: Geelong and Melbourne, Victoria, and Sydney, New South Wales. Demographic information, inclusion and exclusion criteria for the overall sample can be found in Berk and colleagues [19]. In summary, participants were required to have a diagnosis of BD (MINI Plus Version 5.0.0) and a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of ≥ 20 representing moderate to severe bipolar depression [21]. To be included in this study participants needed to have attended at least one post-baseline visit. One hundred and forty-eight participants were included in this sub-analysis.

Measures

Pharmacotherapy data was collected for all partici-pants throughout the trial, including medications, doses, frequencies, indication, and any changes to the medications (stopped, started, or dosage adjustments). PTSD diagnosis was assessed using the MINI Plus Version 5.0.0 [21]. Reliability and inter-rater reliability assessments were completed and training modules were completed by all raters for administering the rating scales in the RCT.

To examine the treatment outcomes, validated and reliable mood and functioning measures were completed at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. These measures included the primary outcome of the parent study, the MADRS [22], as well as the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (BDRS) [23], Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [24] and the Social Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) [25] which were used in this sub-analysis to compare BD alone and BD + PTSD.

Analysis

Baseline differences between those with and without PTSD were examined using independent sample ttests for continuous measures and the chi-square (χ2) test for categorical variables. Independent samples ttests were used for individual timepoint analysis (at each study visit, five follow-up time points) for outcome measures including the MADRS, BDRS, YMRS, and SOFAS. To compare change in symptoms over time, change scores from baseline to week 16, and baseline to week 20 were calculated for each outcome measure. Analyses comparing treatment arms (mitochondrial enhancers including NAC vs. NAC alone vs. placebo) were not completed due to insufficient sample sizes within the comorbid BD and PTSD clinical group. To mitigate against multiple statistical comparisons, we used an alpha level of 0.025 for all statistical tests. To supplement findings, effect sizes measures were reported; Cohen’s d for group differences on continuous measures; Cramer’s V for group differences on categorical variables, and r for differences between groups based on non-parametric continuous variables. Cohen’s criteria [26] were used to interpret strength of the effect sizes. The study is powered to detect only a large mean differential change of five MADRS units or more (81% power).

RESULTS

Participants (n = 148) were divided into two groups, those with BD + PTSD (n = 23) and those with BD alone (n = 125). The baseline characteristics of these groups are shown in Table 1. Participants were aged between 21 and 72 years (mean = 46.5, standard deviation = 12.3) and were more likely to be female (64.86%, n = 96) the groups did not differ in terms of age or sex distributions. Those with BD alone were significantly more likely to be in a relationship than those with BD + PTSD (χ2 (1) = 6.08, p = 0.01). There were no significant differences between individuals with BD alone and those with BD + PTSD on any other demographic variables. The retention of participants in the MADRS group analysis in the BD alone group at week 20 (n = 95) was 76.0% and the retention of the BD + PTSD group at week 20 (n = 14) was 60.8%, at week 16 the retention of participants in the BD alone group was 78.4% (n = 98) and in the BD + PTSD group was 73.9% (n = 17). There was no significant difference between groups retention rates at either week 16 or week 20 (χ2 (1) = 0.50, p = 0.47).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for baseline demographic and illness features for BD alone and BD + PTSD

| Characteristics | BD alone (n = 125, 84.46%) | BD + PTSD (n = 23, 15.54%) | Test-statistic | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.4 ± 12.7 | 44.4 ± 9.5 | t(38.26) = −0.87, p = 0.38 | d = −0.16 |

| Female | 63.2 (79) | 73.9 (17) | χ2 = 0.97, p = 0.32 | V = 0.08 |

| Relationship status, married/defacto | 46.6 (62) | 21.7 (5) | χ2 = 6.08, p = 0.01 | V = 0.20 |

| Illness features | ||||

| Age of formal BD diagnosis | 35.4 ± 11.7 | 34.5 ± 9.3 | t(36.13) = −0.41, p = 0.68 | d = −0.08 |

| Self report duration of illness (in years) | 25.4 ± 12.2 | 25.5 ± 9.7 | t(36.54) = 0.05, p = 0.95 | d = 0.01 |

| Number of hospitalisations, median (IQR) | 1.0 (4) | 2.0 (5) | U = 1,164.50, Z = −0.78, p = 0.28 | r = 0.39 |

| Medication at baseline | ||||

| Antidepressant, yes | 54.4 (68) | 69.6 (16) | χ2 = 1.82, p = 0.17 | V = 0.11 |

| Mood stabiliser, yes | 72.0 (90) | 52.3 (12) | χ2 = 3.56, p = 0.05 | V = 0.15 |

| Antipsychotic, yes | 57.6 (72) | 65.2 (15) | χ2 = 0.46, p = 0.49 | V = 0.05 |

| Benzodiazepine, yes | 18.4 (23) | 26.1 (6) | χ2 = 0.72, p = 0.39 | V = 0.07 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; df, degrees of freedom.

t = ttest, χ2 = chi square, U = Mann−Whitney. Cramer’s V used to interpret chi-square effect size, Cohen’s dused to interpret ttest effect size and rwas used to interpret Mann−Whitney effect size. Adjusted df reported.

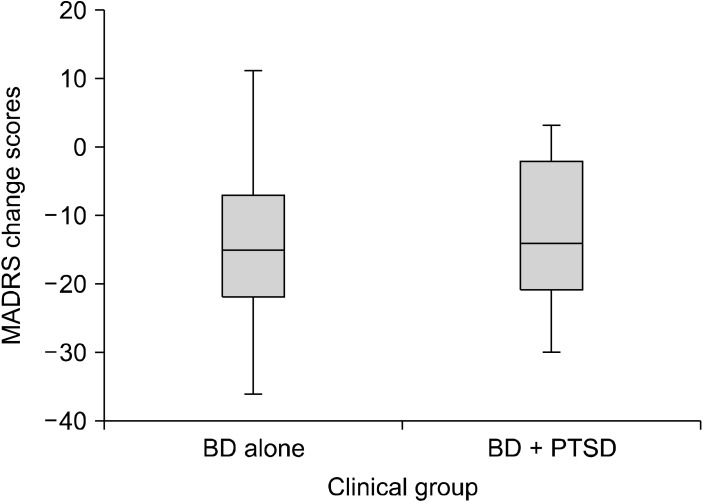

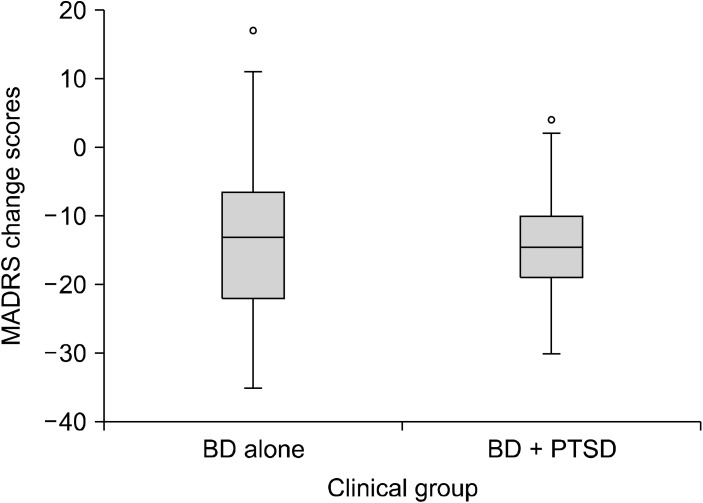

Using independent samples ttest there was no signifi-cant difference in scores for BD alone and BD + PTSD on any of the outcome measures at any time point (Table 2). Effect sizes measured by Cohen’s d ranged from small to medium (0.01−0.42) for all ttest comparisons. Multiple statistical analysis techniques were used to test the robustness of these results. However, the results remain unchanged with more sophisticated generalised estimation equation modelling (including symptom scores as the outcome, and the interaction of time at 6 levels and PTSD at 2 levels ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as fixed predictors) to simultaneously model all follow-up time points while accounting for within-individual autocorrelation. Change in MADRS total score from baseline to week 16 (end of trial) and baseline to week 20 (post treatment follow-up), in those with and without PTSD are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. The rate of change from baseline to the follow-up time points were similar for the two groups.

Table 2.

Comorbid BD + PTSD compared to bipolar disorder alone on mean change scores over time

| Outcome measure | Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 12 | Week 16 | Week 20 | Baseline change scores to week 16 | Baseline change scores to week 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder alone | n = 125, 28.76 ± 5.28 |

n = 124, 19.43 ± 9.1 |

n = 114, 17.13 ± 9.29 |

n = 100, 15.90 ± 10.15 |

n = 98, 15.34 ± 9.88 |

n = 95, 15.80 ± 10.10 |

n = 98, −13.78 ± 10.26 |

n = 95, 13.16 ± 10.46 |

| BD + PTSD | n = 23, 30.78 ± 6.56 |

n = 23, 21.03 ± 10.71 |

n = 20, 17.30 ± 10.21 |

n = 19, 16.42 ± 10.62 |

n = 17, 17.35 ± 11.43 |

n = 14, 16.14 ± 10.10 |

n = 17, −12.17 ± 11.17 |

n = 14, −13.50 ± 10.09 |

| Mean difference (95% CI), Cohen’s d, pvalue | 2.02 (−0.44, 4.4), d = 0.36 | 1.86 (−2.23, 6.08), d = 0.19 |

0.16 (−4.35, 4.69), d = 0.01 |

0.52 (−4.54, 5.59), d = 0.05 |

2.00 (−3.26, 7.27), d = 0.19 |

0.34 (−5.39, 6.44), d = 0.03 |

1.60 (−3.83, 7.05), d = 0.15, p = 0.55 | −0.33 (−6.24, 5.58), d = −0.03, p = 0.91 |

| BDRS | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder alone | n = 125, 24.49 ± 6.32 |

n = 124, 17.45 ± 8.42 |

n = 113, 15.46 ± 9.04 |

n = 100, 14.21 ± 9.27 |

n = 96, 13.53 ± 9.01 |

n = 90, 14.00 ± 8.67 |

n = 96, −11.35 ± 10.43 |

n = 90, −10.88 ± 10.13 |

| BD + PTSD | n = 23, 27.17 ± 7.06 |

n = 23, 19.30 ± 9.35 |

n = 19, 14.26 ± 9.18 |

n = 19, 14.31 ± 9.87 |

n = 15, 14.33 ± 12.66 |

n = 13, 13.84 ± 10.75 |

n = 15, −12.00 ± 11.15 |

n = 13, 12.61 ± 8.07 |

| Mean difference (95% CI), Cohen’s d, pvalue | 2.67 (−0.20, 5.56), d = 0.41 |

1.85 (−1.99, 5.59), d = 0.21 |

−1.19 (−5.64, 3.25), d = −0.13 |

0.10 (−4.53, 4.74), d = 0.01 |

0.80 (−4.46, 6.06), d = 0.08 |

−0.15 (−5.41, 5.10), d = −0.01 |

−0.64 (−6.44, 5.14), d = −0.06, p = 0.82 |

−1.72 (−7.56, 4.10), d = −0.17, p = 0.49 |

| YMRS | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder alone | n = 125, 3.32 ± 3.31 |

n = 124, 3.65 ± 3.34 |

n = 113, 4.44 ± 4.92 |

n = 101, 3.57 ± 4.02 |

n = 96, 3.34 ± 4.08 |

n = 90, 3.29 ± 3.91 |

n = 96, −0.16 ± 4.76 |

n = 90, −0.26 ± 4.27 |

| BD + PTSD | n = 23, 4.34 ± 3.63 |

n = 22, 4.68 ± 6.96 |

n = 19, 3.73 ± 5.94 |

n = 19, 5.00 ± 5.10 |

n = 15, 2.86 ± 3.35 |

n = 14, 5.00 ± 4.97 |

n = 15, −1.29 ± 4.26 |

n = 14, 1.42 ± 4.41 |

| Mean difference (95% CI), Cohen’s d, pvalue | 1.02 (−0.48, 2.53), d = 0.30 |

1.02 (−0.83, 2.88), d = 0.25 |

−0.70 (−3.19, 1.78), d = −0.13 |

1.42 (−0.66, 3.50), d = 0.33 |

−0.48 (−2.68, 1.71), d = −0.12 |

1.70 (−0.61, 4.02), d = 0.42 |

−1.10 (−3.68, 1.48), d = −0.23, p = 0.40 |

1.69 (−0.75, 4.14), d = 0.39, p = 0.17 |

| SOFAS | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder alone | n = 125, 57.27 ± 9.60 |

n = 124, 63.83 ± 12.41 |

n = 114, 66.29 ± 12.53 |

n = 100, 67.66 ± 12.89 |

n = 96, 69.46 ± 13.13 |

n = 92, 69.67 ± 12.93 |

n = 96, 13.21 ± 11.83 |

n = 92, 12.82 ± 12.71 |

| BD + PTSD | n = 23, 53.13 ± 11.32 |

n = 23, 60.60 ± 13.00 |

n = 19, 63.15 ± 10.14 |

n = 18, 64.05 ± 11.32 |

n = 15, 66.33 ± 12.41 |

n = 13, 68.07 ± 13.63 |

n = 15, 13.13 ± 9.73 |

n = 13, 17.07 ± 10.11 |

| Mean difference (95% CI), Cohen’s d, pvalue | −4.14 (−8.57, 0.29), d = −0.41 |

−3.23 (−8.84, 2.38), d = −0.25 |

−3.14 (−9.13, 2.85), d = −0.25 |

−3.60 (−10.03, 2.82), d = −0.28 |

−3.13 (−10.31, 4.02), d = −0.24 |

−1.59 (−9.24, 6.05), d = −0.12 |

−0.08 (−6.46, 6.29), d = −0.01, p = 0.97 |

4.25 (−3.05, 11.56), d = 0.34, p = 0.25 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; BDRS, Bipolar Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; SOFAS, Social Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Box plots of MADRS change scores from baseline to week 16. BD, bipolar disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Fig. 2.

Box plots of MADRS change scores from baseline to week 20. BD, bipolar disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

DISCUSSION

This study explored differences in treatment outcomes between individuals with BD + PTSD and those with BD alone, using data from an adjunctive nutraceutical RCT. Comorbid PTSD did not seem to have a significant impact on the domains of depression, mania, and functioning in this sample of BD participants. Furthermore, baseline medication regimens did not differ between groups, suggesting that regardless of pharmacotherapy treatment selection, the outcomes were similar in those with or without PTSD.

The findings regarding no differences in groups on domains of depression, mania, and functioning partially align with a cross-sectional study conducted by Assion and colleagues [5] on PTSD and trauma exposure in BD with euthymic BD participants (n = 74). Baseline clinical data was analysed showing no statistically significant difference in mania scores between BD alone, BD and those who were exposed to trauma and those with BD + PTSD. However, Assion and colleagues [5] found significantly higher levels of severity of depression within the BD + PTSD group, measured with the Post-Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale. Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Quarantini and colleagues [6] in participants with BDI (n = 355) found that those with BD + PTSD reported worse scores on quality of life, specifically in the psychological, social relationship, and environment domains, compared to those with BD alone.

There was a significant difference in relationship status in baseline demographics, where more people were married or in a de-facto relationship in the BD group, compared to the BD + PTSD group. In contrast, previous studies comparing these two groups did not report differences in relationship status [2,5,10,27]. The social impacts of BD + PTSD can be seen in a recent evaluation of suicidal risk in BD + PTSD, with one of the propensity factors, a perceived lack of social support, was found to be significantly higher in those with BD + PTSD compared to BD alone [27]. Katz and colleagues [27] highlight the importance of assessing specific factors in those with BD + PTSD, including the propensity factors (helplessness, pessimism, perceived lack of social support and despair) even in patients not presenting with suicidality, to ensure correct identification of suicide risk in this comorbidity. Additionally, the association between PTSD and difficulties in social relationships, including intimacy and relationship quality has been well established [28,29]. Considering this, it is possible that social support moderates the effect of PTSD in BD patients. These factors are important to identify when examining BD + PTSD and may help to inform clinical treatment decisions.

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of this study include the small number of participants with BD + PTSD (n = 23) in comparison to the BD alone population (n = 125), which may not have provided adequate statistical power to find differences between the disorder groups. Furthermore, the multiple statistical comparisons that were conducted required this analysis to have an alpha value of p < 0.025. The original RCT was not designed to look at differences in PTSD comorbidity in this cohort, therefore, the outcome measures are to primarily investigate the change of BD symptoms, which excludes any change in specific PTSD symptoms. The cohort was nevertheless followed longitudinally and there was tight characterisation of both baseline profiles and measures of clinical change. The parent study was negative on the primary outcome reducing the potential impact of treatment in this cohort. While PTSD increases the risk of a number of negative outcomes in BD, it does not seem to impact the participants capacity to benefit from treatment within the RCT. In particular all participants in the parent study showed symptom reductions over time; the instance of PTSD had no effect in the rate of change.

Discrepancy between previous literature and the current findings may be attributed to this study focussing on domains of depression, mania and functioning utilising three mood specific scales, and one functioning scale, but the outcome measures of PTSD symptoms were not included, limiting the study focus. Another possible explanation for the differing results could be that previous research focusing on the impact of PTSD in BD did not have similar strict inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria requiring participants to be experiencing a current depressive episode in this study may play a role in overall outcome measures. Previous research has shown that PTSD symptoms including hyperarousal, disrupted sleep and mood swings are more commonly associated with elevated BD mood states and mania [10,11]. Therefore, the inclusion criteria of the study limits the exploration of mania, as depressive severity was artificially truncated and variability of the sample reduced. Observational or cross-sectional studies where there is no mood state restriction in the inclusion criteria may have more scope to see differences in the disorder groups. Additionally, another possible reason for the negative results could be due to a short follow-up period in the parent study. The methodological differences between the current study and previous research could partly explain the variation in results.

Conclusion

We investigated clinical outcome differences between BD alone and BD + PTSD, including domains of depression, mania, and functioning. There were no statistically significant differences between BD alone and BD + PTSD, on these domains or in pharmacological treatments. Exploratory analysis found more people were married or in a de-facto relationship in the BD group, compared to the BD + PTSD group. Given the paucity of information and the limitations of this study analysing secondary outcomes, future studies should consider comorbid PTSD when evaluating outcomes in clinical trials of people with BD. It would also be useful to better understand the impact of subthreshold trauma symptoms and to understand the relationship between the timing of traumas (childhood, adult) and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the participants in this study and the following health services involved in this study: Barwon Health, The Geelong Clinic, The Melbourne Clinic, and the University of Sydney CADE Clinic based at Royal North Shore Hospital.

Funding Statement

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The original RCT was funded by the CRC for Mental Health and a NHMRC project grant (APP1026307), who had no role in study design, analysis, and reporting. The authors are grateful to the Stanley Medical Research Institute, The CRC for Mental Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council for funding the study. MB is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (APP1059660 and APP1156072). SMC is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1061998). Study medications and blinded placebos were supplied by Nutrition Care, Catalent and BioCeuticals, Australia.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

SER has received grant/research support from Deakin University. ALW has received grant/research support from Deakin University. and the Rotary Club of Geelong. OMD is a R.D. Wright Biomedical NHMRC Career Development Fellow (APP1145634) and has received grant support from the Brain and Behavior Foundation, Simons Autism Foundation, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Deakin University, Lilly, NHMRC and ASBDD/Servier. She has also received in kind support from BioMedica Nutracuticals, NutritionCare and Bioceuticals. MMA has received grant/ research support from Deakin University, Australasian Society for Bipolar Depressive Disorders, Lundbeck, Australian Rotary Health, Ian Parker Bipolar Research Fund and Cooperative Research Centre for Mental Health and PDG Geoff and Betty Betts Award from Rotary Club of Geelong. MB has received grant/research support from the NIH, Cooperative Research Centre, Simons Autism Foundation, Cancer Council of Victoria, Stanley Medical Research Foundation, Medical Benefits Fund, National Health and Medical Research Council, Medical Research Futures Fund, Beyond Blue, Rotary Health, A2 milk company, Meat and Livestock Board, Woolworths, Avant and the Harry Windsor Foundation, has been a speaker for Astra Zeneca, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, and served as a consultant to Allergan, Astra Zeneca, Bioadvantex, Bionomics, Collaborative Medicinal Development, Lundbeck Merck, Pfizer and Servier. SC is a NHMRC Senior Research Fellow (APP1136344) and has received money from NHRMC, Wellcome Trust, and HCF Research Foundation. AT has received travel or grant support from NHMRC, AMP Foundation, Stroke Foundation, Hunter Medical Research Institute, Helen Macpherson Smith Trust, Schizophrenia Fellowship NSW, SMHR, ISAD, the University of Newcastle and Deakin University. MM has received Grant/research support from NHMRC, Deakin University School of Medicine, Deakin Biostatistics Unit, Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation, and Medibank Health Research Fund. SD has received Grant/Research Support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute, NHMRC, Beyond Blue, ARHRF, Simons Foundation, Geelong Medical Research Foundation, Fondation FondaMental, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon, Mayne Pharma and Servier, speaker's fees from Eli Lilly, advisory board fees from Eli Lilly and Novartis and conference travel support from Servier. GM has received grant or research support from National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Rotary Health, NSW Health, Ramsay Health, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund, Elsevier, AstraZeneca and Servier; has been a speaker for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier; and has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier. CN had served in the Servier, Janssen-Cilag, Wyeth and Eli Lilly Advisory Boards, received research grant support from Wyeth and Lundbeck, and honoraria from Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Organon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen- Cilag, Astra-Zenaca, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Samantha E. Russell, Anna L. Wrobel, Olivia M. Dean, Alyna Turner, Melanie M. Ashton. Data acquisition: Michael Berk, Seetal Dodd, Chee H. Ng, Gin S. Malhi, Sue Cotton. Funding for the randomized controlled trial: Michael Berk, Seetal Dodd, Chee H. Ng, Gin S. Malhi, Sue Cotton. Statistical analysis: Samantha E. Russell, Alyna Turner, Olivia M. Dean, Mohammadreza Mohebbi. Supervision: Michael Berk, Seetal Dodd, Chee H. Ng, Gin S. Malhi, Sue Cotton. Writing−original draft: Samantha E. Russell, Anna L. Wrobel, Olivia M. Dean, Alyna Turner, Melanie M. Ashton. Writing−review & editing manuscript: Samantha E. Russell, Anna L. Wrobel, Olivia M. Dean, Alyna Turner, Melanie M. Ashton. Writing−review & editing original draft: Michael Berk, Seetal Dodd, Chee H. Ng, Gin S. Malhi, Sue Cotton.

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics, author. Catalogue No. 4236.0. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of results. Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy MK, Meyer TD, Wittlin NM, Miller IW, Weinstock LM. Bipolar I disorder with comorbid PTSD: Demographic and clinical correlates in a sample of hospitalized patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;72:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter JM, Arentsen TJ, Cordova MJ, Ruzek J, Reiser R, Suppes T, et al. Increased suicidal ideation in patients with co-occurring Bipolar Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21:621–632. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1199986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assion HJ, Brune N, Schmidt N, Aubel T, Edel MA, Basilowski M, et al. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in bipolar disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:1041–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quarantini LC, Miranda-Scippa A, Nery-Fernandes F, Andrade- Nascimento M, Galvão-de-Almeida A, Guimarães JL, et al. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on bipolar disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmassi C, Bertelloni CA, Dell'Oste V, Foghi C, Diadema E, Cordone A, et al. Post-traumatic stress burden in a sample of hospitalized patients with Bipolar Disorder: Which impact on clinical correlates and suicidal risk? J Affect Disord. 2020;262:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabavi B, Mitchell AJ, Nutt D. A lifetime prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar affective disorder and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of 52 interview-based studies of psychiatric population. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1405–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerimele JM, Bauer AM, Fortney JC, Bauer MS. Patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: A rapid review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e506–e514. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16r10897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez JM, Cordova MJ, Ruzek J, Reiser R, Gwizdowski IS, Suppes T, et al. Presentation and prevalence of PTSD in a bipolar disorder population: A STEP-BD examination. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otto MW, Perlman CA, Wernicke R, Reese HE, Bauer MS, Pollack MH. Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with bipolar disorder: A review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment strategies. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:470–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Álvarez MJ, Roura P, Foguet Q, Osés A, Solà J, Arrufat FX. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity and clinical implications in patients with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:549–552. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318257cdf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, Emsley RA, Stein DJ. Linking posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis: A look at epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:675–681. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000092177.97317.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association, author. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–2229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neria Y, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Wickramaratne P, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among primary care patients with bipolar spectrum disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:503–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cakir S, Tasdelen Durak R, Ozyildirim I, Ince E, Sar V. Childhood trauma and treatment outcome in bipolar disorder. J Trauma Dissociation. 2016;17:397–409. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.1132489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremer T, Diamond C, McKinney R, Shehktman T, Barrett TB, Herold C, et al. The pharmacogenetics of lithium response depends upon clinical co-morbidity. Mol Diagn Ther. 2007;11:161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF03256238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berk M, Turner A, Malhi GS, Ng CH, Cotton SM, Dodd S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a mitochondrial therapeutic target for bipolar depression: Mitochondrial agents, N-acetylcysteine, and placebo. BMC Med. 2019;17:18. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1257-1. Erratum in: BMC Med 2019;17:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean OM, Turner A, Malhi GS, Ng C, Cotton SM, Dodd S, et al. Design and rationale of a 16-week adjunctive randomized placebo-controlled trial of mitochondrial agents for the treatment of bipolar depression. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015;37:3–12. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) A short diagnostic structured interview: Reli-ability and validity according to the CIDI. 1997;12:224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berk M, Dodd S, Dean OM, Kohlmann K, Berk L, Malhi GS. The validity and internal structure of the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale: Data from a clinical trial of N-acetylcysteine as adjunctive therapy in bipolar disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2010;22:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2010.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. Young Mania Rating Scale. In: Rush AJ, editor. Handbook of psychiatric measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 540–542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2000.tb10933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz D, Petersen T, Amado S, Kuperberg M, Dufour S, Rakhilin M, et al. An evaluation of suicidal risk in bipolar patients with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedman SA, Gilad M, Ankri Y, Roziner I, Shalev AY. Social relationship satisfaction and PTSD: Which is the chicken and which is the egg? Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:28864. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.28864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenen KC, Stellman SD, Sommer JF, Jr, Stellman JM. Persisting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:49–57. doi: 10.1002/jts.20304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]