Graphical abstract

Sonophotocatalytic reaction mechanism of SP/ZnO nanocomposite for degradation of various organic contaminants

Keywords: Sonophotocatalytic process, Nanocatalyst, Organic pollutants, Zinc oxide, Sporopollenin

Highlights

-

•

An SP/ZnO composite was developed for the sonophotocatalysis of organic pollutants.

-

•

The composite exhibited good reusability after four consecutive cycles.

-

•

A plausible mechanism for pollutant degradation was identified.

Abstract

Water resource pollution by organic contaminants is an environmental issue of increasing concern. Here, sporopollenin/zinc oxide (SP/ZnO) was used as an environmentally friendly and durable catalyst for sonophotocatalytic treatment of three organic compounds: direct blue 25 (DB 25), levofloxacin (LEV), and dimethylphtalate (DMPh). The resulting catalyst had a 2.65 eV bandgap value and 9.81 m2/g surface area. The crystalline structure and functional groups of SP/ZnO were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses. After 120 min of the sonophotocatalysis, the degradation efficiencies of DB 25, LEV, and DMPh by SP/ZnO were 86.41, 75.88, and 62.54%, respectively, which were higher than that of the other investigated processes. The role of reactive oxygen species were investigated using various scavengers, enhancers, photoluminescence, and o-phenylenediamine. Owing to its stability, the catalyst exhibited good reusability after four consecutive cycles. In addition, the high integrity of the catalyst was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), XRD, and FTIR analyses. After four consecutive examinations, the leaching of zinc in the aqueous phase was < 3 mg/L. Moreover, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analyses indicated that the contaminants were initially converted into cyclic compounds and then into aliphatic compounds, including carboxylic acids and animated products. Thus, this study synthesized an environmentally friendly and reusable SP/ZnO composite for the degradation of various organic pollutants using a sonophotocatalytic process.

1. Introduction

Pharmaceuticals, plasticizers, and dyes constitute a significant class of water contaminants, which can be discharged into various environmental water sources, and rapid increases in these pollutants in recent decades have threatened the health of ecosystems [1], [2]. Most of these contaminants are stable, non-biodegradable, and noxious, and they present serious concerns regarding their potential risk to humans, aquatic flora, and fauna [3], [4]. One of the main reasons for these toxic properties is the presence of aromatic rings in synthetic organic compounds [5], [6]. Fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin (LEV), which has antibiotic activity, high tissue penetration, and intravenous and oral formulations, are metabolized during therapeutic use and thus have been identified in hospital and municipal wastewater [7], [8]. Dyes used in the textile industry represent another contaminant of concern because considerable amounts are lost during the dyeing procedure, thus generating contaminated effluents that need to be treated [1]. Azo dyes, such as direct blue 25 (DB 25), have nitrogen-nitrogen bonds (-N = N-) that generate color with other chromophores in their structures and are extensively used in textile industry [1], [9]. Dimethyl phthalate (DMPh) is a plasticizer widely used in the production of decorative materials, toys, household necessities, and plastic packaging, and it is an endocrine disruptor with carcinogenic activity and has been found in biological samples [10], [11].

Among water treatment methods, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have been developed based on the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which can nonselectively and efficiently degrade persistent organic contaminants [12], [13]. Sonophotocatalysis is an eco-friendly hybrid AOP in which sonocatalysis and photocatalysis are simultaneously applied for the treatment of polluted wastewater [14], [15], [16]. In both processes, electrons in the valence band (VB) of a semiconductor can be excited by sono and/or photo energy to the conduction band (CB), which subsequently generates electron-hole (e−/h+) pairs. These pairs react with H2O or O2 to form ROS for the degradation of contaminants [17], [18]. Ultrasonic (US) radiation results in cavitation-generating microbubbles that grow and eventually collapse to produce remarkable temperatures and pressures. The released energy can also separate H2O molecules and catalyze ROS generation, particularly •OH radicals, to degrade contaminants and their degradation intermediates [19]. The synergistic effect of light and US irradiation in the sonophotocatalytic process leads to a cleaner and easier operation with higher mass transfer and faster degradation kinetics [20].

Recently, various oxide nanoparticles with semiconducting properties, including zinc oxide (ZnO) [21], ZrO2 [22], and TiO2 [23], have been identified as sonophotocatalysts and their composites have been used to remove diverse contaminants from water. ZnO has a wide variety of morphological characteristics, such as stability, biodegradability, biocompatibility and low toxicity, thus indicating its suitability for pollutant removal [24].

In addition, nanocatalyst immobilization onto carbonaceous templates, such as solvent-resistant sporopollenin (SP), which consists of oxygenated aromatic and long-chain fatty acids, can be considered an operating strategy to overcome practical constraints [25]. Pollens are available in nature and have been used as a template for synthesizing inorganic materials because of their porous structure and high surface area [26]. Moreover, pollen is beneficial in terms of its eco-friendliness, low cost, and stability [27]. For this purpose, pollen with a uniform particle size, chemical resistance, and an exine outer wall, which is primarily composed of SP, can be utilized in combination with nanostructured sonophotocatalysts [28], [29], [30]. Hierarchically structured metal oxides generated using pollen as the hard template display enhanced sonophotocatalytic performance owing to their suitable mass transfer and facile pathways for chemicals and electrons [26]. This study aimed to prepare the SP-ZnO nanocomposite as an appropriate sonophotocatalyst for the treatment of different types of pollutants. The samples were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) dot mapping, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS), and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Various scavengers and enhancers were applied to realize ROS functions in the sonophotocatalytic process. Moreover, a plausible mechanism for pollutant degradation was identified based on the intermediates identified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Sporopollenin (Lycopodium clavatum spores, 20 μm) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 38%) was obtained from Royalex (India). Diethyl ether (C4H10O, 99%), sodium percarbonate (Na2CO3, 99%), 1, 4-benzoquinone (99%), chromium trioxide (CrO3, 99%), potassium persulfate (K2S2O8, 98%), 2-propanol (99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide were obtained by Merck (Germany). Ethanol (C2H5OH, 96%), ZnO2 (99%), and O-phenylenediamine (OPD, 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (USA). LEV, DB 25, and DMPh were obtained from Rouz Darou Laboratories (Iran), Shimi Boyakhsaz (Iran), and Merck, respectively. The characteristics of all the contaminants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the contaminants.

|

Name |

Chemical structure | Molecular formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

λmax (nm) | Initial pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levofloxacin |  |

C18H20FN3O4 | 361.4 | 293 | 6.1 |

| Dimethyl phthalate |  |

C10H10O4 | 194.2 | 282 | 6.50 |

| Direct blue 25 |  |

C34H22N4Na4O16S4 | 962.8 | 610 | 7.3 |

2.2. Synthesis of sporopollenin-zinc oxide

Following simple and accessible method was used for the synthesis of the sporopollenin-zinc oxide composite (SP-ZnO). The SP-ZnO composite was prepared by mixing 0.4 g of ZnO with 0.2 g of SP in an aqueous solution. The obtained suspension was stirred for 3 h at 60 °C with a magnetic stirrer, and then the resulting suspension was centrifuged. Finally, SP-ZnO was washed and dried at 60 °C for 4 h [31]. The preparation procedure is schematically illustrated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Schematic diagram of the SP-ZnO composite preparation.

2.3. Sonophotocatalytic degradation procedure

Sonophotocatalytic degradation of the contaminants was performed using an ultrasound bath (40 kHz, 300 W EP S3, Sonica, Italy) and a visible light source (50-W LED lamp). Different dosages of the catalyst were added to the pollutant solution (10 mg/L, 100 mL). Three milliliters of the solution was collected at 10 min intervals during the sonophotocatalytic treatment, and its absorbance was measured using an ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer (SU-6100, Philler Scientific, USA) at the maximum absorbance wavelength of the contaminants (λmax) to calculate the degradation efficiency (DE%) [16].

2.4. Characterization instruments

XRD (Tongda-TD-3700, China, Cu Kα radiation: λ = 1.5406 A0; 30 kV, 20 mA) was performed to analyze the crystallographic characteristics of the samples. SEM images were obtained using a Tescan Mira3 microscope (Czech Republic). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Leo 906 Zeiss, Germany) was performed at 100 kV. Functional groups of the samples were investigated using an FTIR spectrometer (400–4000 cm−1, Tensor 27, Bruker, Germany) using a KBr disk. DRS spectra were obtained using an Analytik Jena spectrophotometer (S 250, Germany) to determine the band gap. The surface area of the samples was tested by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller Surface Area & Porosity Analyzer (Belsorp Mini II, Japan). Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS; NovAA 400, Analytik Jena, Germany) was performed to evaluate the amount of Zn leached into the solution. GC–MS (6890 N/5973 N, Agilent, USA) was used to identify the intermediates generated during the degradation of pollutants. Mot-shotky test weas conducted by Origa Flex-OGF 01A Potentiostate/Galvanostate using a three-electrode setup in 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution (electrolyte).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization

The morphology and particle size of pure SP and the SP/ZnO composite were determined by SEM (Fig. 1). A channel-like microstructure with a bulky and rough surface was observed for SP, which was advantageous for ZnO attachment. Moreover, the formation and immobilization of ZnO on SP were confirmed, in which the nanoparticles developed individually and orderly, with no aggregation on the support [32]. Similar to our results, George et al. [29] reported a honeycomb-like structure of SP and revealed that ZnO nanoparticles were firmly anchored to the SP exine, thus forming a closed shell around the organic core. Furthermore, to identify any impurities, elemental composition measurements were performed. The elemental compositions of the samples obtained via EDX are shown in Fig. 2. The composite spectrum shows C, O, and Zn elements, and the C peak indicates the proper affinity between SP and ZnO. Thus, ZnO was successfully attached to the SP surface.

Fig. 1.

SEM images with various magnifications of (a–c) SP and (d–f) SP-ZnO.

Fig. 2.

Elemental mapping images of (a–c) SP and (d–g) SP-ZnO and EDX spectra of (h) SP and (i) SP-ZnO.

TEM was used to examine the morphological structures of SP/ZnO (Fig. 3). The images show the presence of SP as the support and ZnO nanoparticles on its surface. As observed from the TEM images, the synthesized ZnO was close to the SP support, demonstrating the appropriate immobilization of nanostructured sonophotocatalysts on the SP support.

Fig. 3.

TEM images of SP-ZnO with different magnifications.

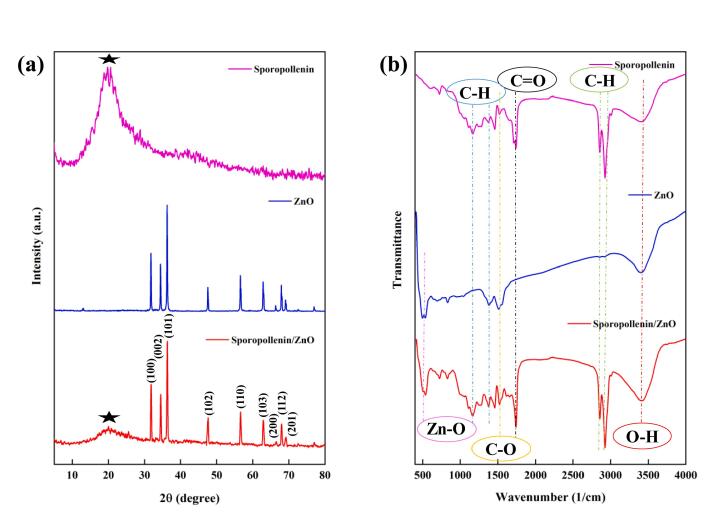

The crystalline components of the samples were investigated by XRD (Fig. 4a). The observed peaks at 31.78°, 34.44°, 36.26°, 47.54°, 56.58°, 62.86°, 66.34°, 67.94°, and 69.1° were related to the (1 0 0), (0 0 2), (1 0 1), (1 0 2), (1 1 0), (1 0 3), (2 0 0), (1 1 2), and (2 0 1) ZnO planes, respectively. Moreover, amorphous materials such as natural SP typically display broad diffraction peaks at approximately 20°. Hence, the XRD pattern, in which all peaks were consistent with the reported data, confirmed the coexistence of SP and ZnO and the composite synthesis [29], [33]. The immobilization of a catalyst on support is dependent on the surface functional groups of the catalyst. Therefore, FTIR analyses were performed, and the results are shown in Fig. 4b. The band at approximately 3400 1/cm indicated an O–H group [34]. Furthermore, peaks in the range of 1100–1400, 1500, 1700, and 2900–2800 1/cm were related to C-H, C-O, and C = O bending and C-H vibrations, respectively [33], [35]. The peak observed in the range of 400–500 1/cm was attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the Zn–O bonds. All peaks related to the composite were sharp and short, revealing their asymmetrical structures [36].

Fig. 4.

(a) XRD and (b) FTIR patterns of SP, ZnO, and SP-ZnO.

The optical characteristics of the as-prepared composites were evaluated using UV–Vis DRS (200–600 nm). The bandgap energy (Eg) values of ZnO and SP-ZnO were calculated using Tauc’s equation (Eq. (1) by depicting (αhν)2 against hν [37], [38].

| (1) |

where A, α, h, n, and ν represent a constant, the absorption coefficient, Planck’s constant, an index characterizing optical absorption, and light frequency, respectively. The Eg values of ZnO and SP/ZnO were 3.17 and 2.65 eV, respectively (Fig. 5). The narrow bandgap results associated with strong sonophoto-absorption in the visible region can be ascribed to ZnO immobilization onto the carbon-based material like SP. Immobilizing ZnO onto the SP channel-like structure significantly reduced the band gap, which is consistent with previously reported results [26]. The semiconductor composite remarkably generates e−/h+ pairs after e− excitation from the VB to CB. Then, the adsorbed H2O and/or OH− can be oxidized by h+ to produce •OH radicals. Moreover, other ROS, such as O2•− and HO2•, can be formed through the interaction of O2 with CB electrons for pollutant degradation [29], [38].

Fig. 5.

(αhʋ)2 versus hʋ plots of (a) ZnO, and (b) SP-ZnO samples.

The surface area of SP and SP/ZnO was determined by the N2 adsorption–desorption technique to study the pore structure and surface area of the samples. The typical samples of the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution plots (inset figures) are demonstrated in Fig. 6. The surface area directly affects the active sites and adsorption capacity and consequently the sonophotocatalytic degradation of pollutants. According to the obtained data, the average pore sizes of SP and SP/ZnO were 17.76, and 13.27 nm, respectively. They have relatively wide distribution, which shows that all the samples have mesoporous structures and type III profiles [39]. Moreover, the surface area of SP and SP/ZnO is 6.87, and 9.81 m2/g, respectively. The ZnO immobilization on SP enhanced the surface area; hence, the improved sonophotocatalytic efficiency of SP/ZnO can be attributed to the elevated structural properties of the as-synthesized composite [29].

Fig. 6.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of (a) SP, and (b) SP/ZnO. (adsorption (hollow circles) and desorption (full circles). Insets show their representative pore size distribution.

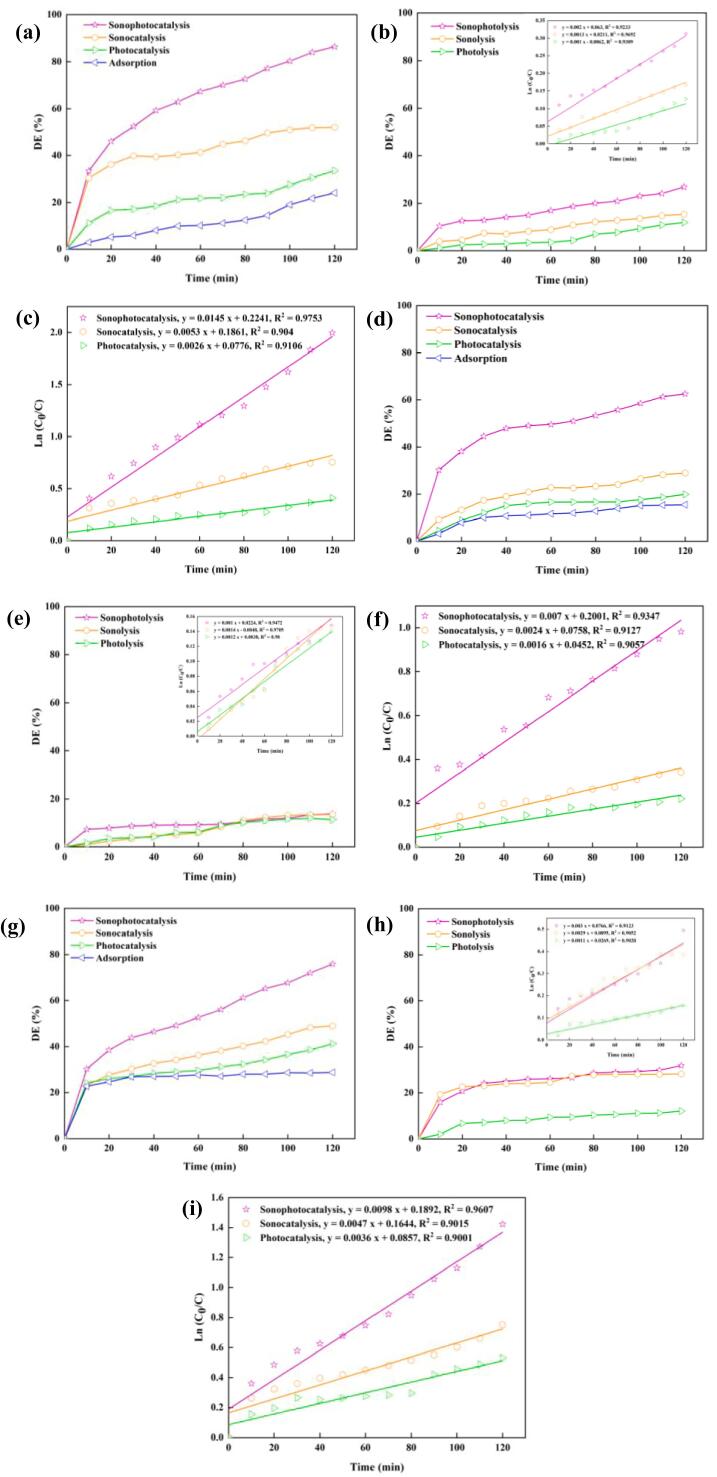

3.2. Comparing various processes for the contaminants degradation

The sonophotocatalytic process was carried out to excite the as-prepared composite to form the e−/h+ pairs and then ROS [40], [41]. Of note, adsorption of the DB 25, LEV, and DMPh pollutants onto SP/ZnO (24.12, 28.78, and 15.46%, respectively) was not remarkable under dark conditions. The roles of individual processes, including sonophotolysis, sonolysis, photolysis, photocatalysis, and sonocatalysis, in pollutant degradation were also studied. The DE% values of all the above-mentioned processes were compared with those of the sonophotocatalytic process using SP/ZnO in control experiments (Fig. 7). The results demonstrate that the hybrid sonophotocatalytic process exhibits the highest performance among the individual processes under identical operating conditions. Sonophotocatalysis of the pollutants (i.e., DB 25, LEV, and DMPh) using SP/ZnO was carried out, and the calculated DE% values were 86.41%, 75.88%, and 62.54%, respectively. These values were higher than that obtained for the other investigated processes because of the decrease of the e−/h+ recombination rate and generation of additional ROS, including •OH and O2•. The sonophotocatalytic rates in the abovementioned processes were determined kinetically [42]. Fig. 7. shows that the degradation of DB 25 by SP/ZnO has the highest pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (1.45 × 10−2 min−1) in the sonophotocatalytic system compared with that of LEV (9.8 × 10−3 min−1) and DMPh (7.00 × 10−3 min−1). The regression coefficients for each pollutant (R2 > 0.975, R2 > 0.960, and R2 > 0.934) indicate that the proposed model can determine the process kinetics. To clarify the major role of SP/ZnO in sonophotocatalytic degradation, the synergistic index was calculated using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

Fig. 7.

Function of the individual process involved in the degradation of DB 25 by SP-ZnO and the kinetic result (a–c). Function of the individual process involved in the degradation of DMPh by SP-ZnO and the kinetic result (d–f). Function of the individual process involved in the degradation of LEV by SP-ZnO and the kinetic result (g–i). Experimental conditions: [catalyst] = 0.1 g/L, [pollutant]0 = 10 mg/L, and initial pH of contaminats.

The estimated synergy factor values for the sonophotocatalytic degradation of DB 25, DMPh, and LEV were 1.83, 1.75, and 1.75, respectively. The detailed pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (kapp min−1) for each process was calculated from the slope of the plot of ln(C0/C) against the process time (t) (Fig. 7).

3.3. Identification of ROS roles in the sonophotocatalytic process

In general, ROS are significant contributors to pollutant degradation during sonophotocatalysis [43]. Enhancers, including H2O2 and K2S2O8, were added to the process, which led to an increase in the DE% of the pollutant. For the SP/ZnO composite, the DE% increased from 86.41 to 89.99% and 94.36% in the presence of H2O2 and K2S2O8, respectively (Fig. 8a). The addition of H2O2 addition promoted DB 25 degradation primarily because of the increased generation of •OH during the process as well as the reduction in the CB (Eqs. (3), (4):

| (3) |

| (4) |

Fig. 8.

Effect of (a) enhancers (5 mM), and (b) scavengers (scavenger to DB 25 M ratio of 1:1) (c) spectra of the OPD-trapped •OH, and (d) PL spectra changes during the photocatalytic degradation with terephthalic acid using the SP/ZnO sonophotocatalyst; experimental conditions: [catalyst] = 0.1 g/L, [DB 25]0 = 10 mg/L, and pH = 7.3.

Persulfate was a better enhancer than hydrogen peroxide, which may have been due to the efficiency of persulfate activation under sonication and irradiation, particularly in the presence of the catalyst, resulting in more active radicals for DB 25 degradation (Eqs. (5), (6) [44].

| (5) |

| (6) |

The addition of various scavengers was also studied to evaluate the role of oxidizing species in the sonophotocatalytic degradation of DB 25. The presence of BQ, CrO3, sodium percarbonate, and isopropanol decreased the DE% from 86.41% to 52.33%, 34.87%, 28.64%, and 21.54%, respectively, after 120 min (Fig. 8b). Consequently, isopropanol, as an •OH quencher, had the greatest quenching influence on DB 25 degradation. Moreover, when BQ was used as an O2•− radical scavenger, it was less effective. The addition of CrO3 and sodium percarbonate also resulted in a remarkable decline in DB 25 degradation. Both sodium percarbonate and CrO3 are electron scavengers, which represents the most important function of the electrons in the degradation process. Hence, •OH radicals and electrons are recognized as essential species in the degradation mechanism [45].

Moreover, the presence of •OH radicals was determined by an OPD probe using a visible spectrophotometer. Fig. 8 c, reveals a peak at approximately 420 nm, which is attributed to the OPD-trapped •OH in the sonophotocatalytic procedure [46]. These results indicated that the intensity of the spectra was altered by the sonophotocatalytic process using the SP/ZnO composite. Moreover, the generation of •OH radicals increased with reaction time.

To clarify the role of •OH radicals in the sonophotocatalytic process, photoluminescence (PL) analysis with terephthalic acid was performed to better understand of these radicals involvement as the main oxidizing species [47]. The PL analysis of SP/ZnO nannocomposite was performed under sonophotocatalytic reaction to illustrate the separation and recombination process of generated e−/h+ pairs. As displayed in Fig. 8 d, the intensity of PL spectra enhanced with time. Therefore, the formation of •OH radicals increased during the sonophotocatalysis.

3.4. Sonophotocatalytic degradation mechanism

The sonophotocatalytic reaction mechanism and the band positions over the SP/ZnO catalyst were investigated. In the sonophotocatalytic process, the electrons (e−) could be excited from VB to CB of the semiconductor under the irradiation energy, and the electron-hole (e−/h+) pairs are generated [48]. Fig. 9a depicts the anticipated pathway for the degradation of contaminants by the SP/ZnO sonophotocatalyst. Initially, the SP/ZnO is subjected to irradiation which leads to creat e−/h+ on the catalyst surface. The h+ reacts with the H2O molecules to form the •OH radicals while the e− reacts with the dissolved O2 to form the radicals. The produced radicals are the efficient species for the pollutants degradation into non-toxic compounds like CO2 and H2O. In conclusion, the following oxidation and reductions can be used to explain the mechanism of sonophotocatalytic degradation of pollutants:

Fig. 9.

(a) Illustration of sonophotocatalytic reaction mechanism and band positions over SP/ZnO, and (b) The Mott - Schottky plot of SP/ZnO.

As shown in Fig. 9b, the Mott-Schottky (M−S) curve has been used to define the band edge positions of sonophotocatalysts. Apparently, the flat band potentials (EFB) of SP/ZnO was −0.7 V vs. saturated calomel electrode (SCE). The positive slope of the M−S plot for SP/ZnO indicates the n-type nature. The EFB is estimated according to the extrapolation of the plot with an x-intercept in the curve. Using the Nernst equation, E(NHE) = E(SCE) + 0.24, the flat band potential value is adjusted with regard to the normal hydrogen electrode potential (-0.46 V vs NHE). According to Eg of SP/ZnO and the band gap equation (ECB = EVB – Eg), the EVB is calculated to be 2.19 V [49].

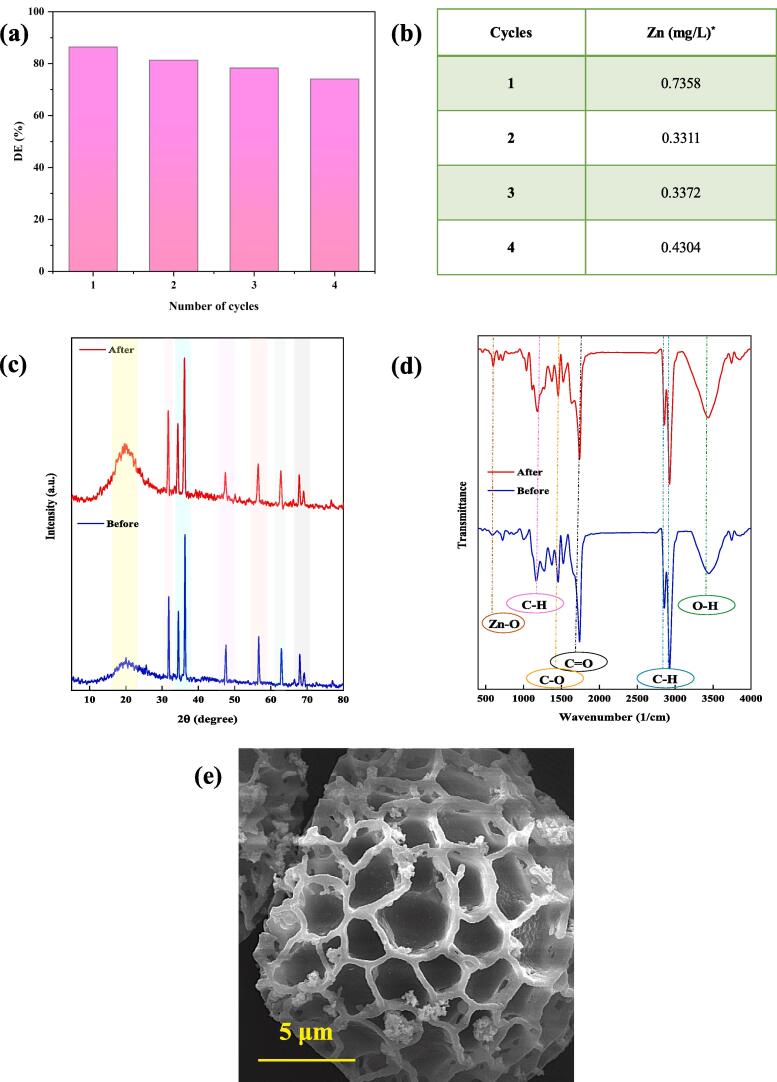

3.5. Reusability test results

Four consecutive experiments were performed to evaluate the potential of the as-prepared sonophotocatalyst for practical applications [50], and its stability was confirmed as shown in Fig. 10 a. The leached concentration of Zn after the four experiments was lower than 0.430 mg/L, which is lower than the legal limit of Zn in drinking water (3 mg/L) based on a World Health Organization report [51]. These findings confirmed the stability of the composite and the lack of secondary waste production in the aquatic solution (Fig. 10b) [52].

Fig. 10.

(a) Reusability of SP-ZnO for degradation of DB 25, (b) leaching concentrations of zinc from SP-ZnO into the solution, (c) XRD spectra, (d) FTIR pattern, and (c) SEM image of SP-ZnO after four consecutive runs.

Eventually, the XRD, FTIR, and SEM analyses were performed on the used SP/ZnO, (Fig. 10c–e). All XRD peaks in the applied catalyst were in agreement with the unused one. Also the composite morphology, and the surface functional groups were generally preserved. Thus, the suitable physicochemical stability of the sonophotocatalyst for consecutive applications was confirmed.

3.6. Degradation by-products identification

GC–MS was performed to identify the intermediates formed during the degradation of DB 25, DMPh, and LEV using the SP/ZnO sonophotocatalyst (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4). Briefly, after performing the sonophotocatalysis process for each pollutant (20 mg/L, 60 min), diethyl ether (25 mL) was added to the treated solution to extract organic byproducts. The remaining solids were dissolved in N, O-bis-(trimethylsilyl)acetamide under heating. Finally, a GC–MS analysis was carried out with a distinct temperature program (50 °C for 1 min, heating at 8 °C/min up to 120 °C, 4 min hold time, heating again at 8 °C/min up to 300 °C, and 3 min hold time).

Table 2.

Intermediates identified during degradation of DB 25 by the SP-ZnO sonophotocatalytic process.

| No. | Compound | tR (min) |

Main fragments (m/z)(%) | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.951 | 146.10 (100.00%), 130.10 (81.32%), 147.10 (61.76%), 73.10 (57.67%), 75.00 (36.02%) |

|

|

| 2 | Butylated hydroxy toluene | 17.598 | 205.10 (100.00%), 147.00 (90.06%), 75.10 (38.80%), 73.10 (33.39%), 220.20 (25.34%) |

|

| 3 | Propanedioic acid | 21.338 | 147.10 (100.00%), 75.00 (44.98%), 59.10 (16.70%), 73.10 (16.30%), 148.10 (14.52%) |

|

| 4 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid | 30.981 | 149.00 (100.00%), 167.00 (33.44%), 57.10 (26.28%), 147.10 (21.02%), 71.10 (20.27%) |

|

| 5 | Ethanimidic acid | 5.680 | 147.10 (100.00%), 75.10 (33.97%), 73.10 (33.30%), 116.10 (22.22%), 148.10 (19.98%) |

|

| 6 | 2,6-Octadiene, 3,7-dimethyl | 3.994 | 147.10 (100.00%), 75.00 (34.87%), 73.10 (19.39%), 148.00 (16.75%), 131.00 (9.53%) |

|

| 7 | Acetic acid | 4.560 | 75.10 (100.00%), 116.10 (87.12%), 73.10 (14.72%), 117.10 (11.05%), 76.10 (9.92%) |

|

Table 3.

Intermediates identified during degradation of DMPh by the SP-ZnO sonophotocatalytic process.

| No. | Compound | tR (min) |

Main fragments (m/z)(%) | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pentanamide | 3.073 | 59.00 (100.00%), 147.00 (37.88%), 55.00 (10.00%), 69.10 (9.42%), 83.10 (8.12%) |

|

| 2 | Acetic acid | 3.850 | 75.00 (100.00%), 116.10 (90.33%), 73.10 (13.96%), 117.00 (10.92%), 76.00 (9.52%) |

|

| 3 | Ethanol | 8.466 | 59.00 (100.00%), 147.00 (90.41%), 75.10 (38.24%), 73.00 (27.74%), 55.10 (25.52%) |

|

| 4 | Cyclohexanecarboxylic acid | 16.278 | 69.10 (100.00%), 82.00 (57.71%), 73.00 (52.64%), 75.00 (46.17%), 225.00 (34.05%) |

|

| 5 | Cyclohexanol | 26.542 | 135.10 (100.00%), 69.10 (90.34%), 136.10 (44.14%), 93.10 (41.13%), 81.10 (39.64%) |

|

Table 4.

Intermediates identified during degradation of LEV by the SP-ZnO sonophotocatalytic process.

| No | Compound | tR (min) |

Main fragments (m/z)(%) | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethanimidic acid | 3.450 | 59.00 (100.00%), 147.00 (55.00%), 148.00 (8.85%), 73.00 (6.35%), 149.00 (4.47%) |

|

| 2 | Acetic acid | 4.782 | 75.00 (100.00%), 116.10 (96.49%), 73.10 (15.04%), 117.00 (12.67%), 76.00 (10.51%) |

|

| 3 | 3-(Methylthio)-2-butanone | 5.625 | 75.00 (100.00%), 116.00 (72.61%),59.00 (16.34%), 73.00 (14.36%), 76.00 (8.06%) |

|

| 4 | 2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)pyridine | 22.337 | 215.10 (100.00%), 73.00 (48.95%), 93.00 (32.09%), 143.10 (30.43%), 117.10 (24.95%) |

|

| 5 | P-mentha-1,8-dien-4-hydroperoxide | 30.060 | 69.10 (100.00%), 151.10 (64.53%), 146.10 (64.47%), 55.00 (43.01%), 73.00 (41.76%) |

|

| 6 | 2-Butanol | 5.225 | 59.10 (100.00%), 207.00 (25.32%), 147.10 (25.12%), 75.00 (22.46%), 73.00 (17.01%) |

|

| 7 | 4-Pentenoic acid | 34.965 | 69.10 (100.00%), 83.10 (82.29%), 57.10 (74.59%), 82.10 (74.43%), 55.00 (63.96%) |

|

| 8 | 3-Hexanol | 5.525 | 59.10 (100.00%), 73.10 (41.99%), 174.10 (33.40%), 75.00 (32.68%), 147.00 (22.39%) |

|

| 9 | Butanoic acid | 5.836 | 59.10 (100.00%), 221.10 (41.46%), 147.00 (33.73%), 75.00 (26.58%), 73.10 (20.00%) |

|

| 10 | 3-Cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde | 26.176 | 69.10 (100.00%), 73.10 (71.70%), 75.00 (65.48%), 55.10 (61.79%), 81.00 (56.16%) |

|

| 11 | Triethylamine | 19.884 | 262.10 (100.00%), 73.00 (25.66%), 263.10 (22.99%), 59.00 (11.19%), 75.00 (9.85%) |

|

The short-chain intermediates revealed considerable mineralization of the pollutants, which progressed by the cleavage of the C–C, C–N, and C–O bonds. Furthermore, diverse acids and alcohols were generated from the destruction of aromatic rings. However, other intermediates could not be identified by GC–MS because of their short lifetimes and the limitations of this technique.

4. Conclusion

An environmentally friendly SP/ZnO composite was synthesized for the degradation of various organic pollutants using a sonophotocatalytic process. XRD analysis confirmed the coexistence of SP and ZnO peaks in the composite structure. The resulting SP/ZnO catalyst had a specific surface area of 9.81 m2/g and a bandgap value of 2.65 eV. The removal efficiencies of DB 25, LEV, and DMPh by SP/ZnO were 86.41%, 75.88%, and 62.54%, respectively, under operational conditions of 0.1 g/L catalyst, 10 mg/L pollutants, and natural pH values of the pollutants. The reusability results demonstrated that SP/ZnO was reusable and provided impressive wastewater treatment effects with the low Zn leaching. Moreover, the SEM, XRD and FTIR analyses of the applied catalyst after four consecutive experiments were close to that of the original catalyst after confirming its high stability. The addition of scavengers and enhancers affected the efficiency of the sonophotocatalytic degradation process, and •OH radicals represented the main ROS in this process. Using GC–MS, various intermediates of DB 25, DMPh, and LEV generated during sonophotocatalysis were identified.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Parisa Yekan Motlagh: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Behrouz Vahid: Data curation, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Sema Akay: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Berkant Kayan: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Alireza Khataee: Supervision, Project administration, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the University of Tabriz, and Yonsei University Mirae Campus for their support.

Contributor Information

Yeojoon Yoon, Email: yajoony@yonsei.ac.kr.

Alireza Khataee, Email: a_khataee@tabrizu.ac.ir.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Ismail G.A., Sakai H. Review on effect of different type of dyes on advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for textile color removal. Chemosphere. 2022;291:132906. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahdavi K., Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Yousif Q.A., Salavati-Niasari M. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of toxic contaminants using Dy2O3-SiO2 ceramic nanostructured materials fabricated by a new, simple and rapid sonochemical approach. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Morassaei M.S., Amiri O., Salavati-Niasari M. Green synthesis of dysprosium stannate nanoparticles using Ficus carica extract as photocatalyst for the degradation of organic pollutants under visible irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2020;46(5):6095–6107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Heidari-Asil S.A., Salavati-Niasari M. Simple and eco-friendly synthesis of recoverable zinc cobalt oxide-based ceramic nanostructure as high-performance photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic removal of organic contamination under solar light. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;267 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta V., Devasia J., Chauhan A., M J., L V.V., Jha A., Nizam A., Lin K.-Y., Ghotekar S. Photocatalytic nanomaterials: applications for remediation of toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and green management. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022;11 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Mortazavi-Derazkola S., Salavati-Niasari M. Sonochemical synthesis, characterization and photodegradation of organic pollutant over Nd2O3 nanostructures prepared via a new simple route. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017;178:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motlagh P.Y., Soltani R.D.C., Pesaran Z., Akay S., Kayan B., Yoon Y., Khataee A. Sonocatalytic degradation of fluoroquinolone compounds of levofloxacin using titanium and zirconium oxides nanostructures supported on paper sludge/wheat husk-derived biochar. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022;114:84–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabavathi S.L., Saravanakumar K., Park C.M., Muthuraj V. Photocatalytic degradation of levofloxacin by a novel Sm6WO12/g-C3N4 heterojunction: performance, mechanism and degradation pathways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;257 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Mortazavi-Derazkola S., Salavati-Niasari M. Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic degradation of methyl violet pollutant of holmium oxide nanostructures prepared through a facile precipitation method. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;231:306–313. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li S., Lai C., Li C., Zhong J., He Z., Peng Q., Liu X., Ke B. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of dimethyl phthalate by magnetic dual Z-scheme iron oxide/mpg-C3N4/BiOBr/polythiophene heterostructure photocatalyst under visible light. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;342 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao W., Zheng T., Wang P., Tu S., Pan W. Efficient microwave-assisted photocatalytic degradation of endocrine disruptor dimethyl phthalate over composite catalyst ZrOx/ZnO. J. Environ. Sci. 2010;22(11):1800–1806. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(09)60322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang T., Peng J., Zheng Y., He X., Hou Y., Wu L., Fu X. Enhanced photocatalytic ozonation degradation of organic pollutants by ZnO modified TiO2 nanocomposites. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;221:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boczkaj G., Fernandes A. Wastewater treatment by means of advanced oxidation processes at basic pH conditions: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;320:608–633. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paździor K., Bilińska L., Ledakowicz S. A review of the existing and emerging technologies in the combination of AOPs and biological processes in industrial textile wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;376 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karim A.V., Shriwastav A. Degradation of ciprofloxacin using photo, sono, and sonophotocatalytic oxidation with visible light and low-frequency ultrasound: degradation kinetics and pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;392 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babu S.G., Karthik P., John M.C., Lakhera S.K., Ashokkumar M., Khim J., Neppolian B. Synergistic effect of sono-photocatalytic process for the degradation of organic pollutants using CuO-TiO2/rGO. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;50:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu D., Zhou Q. Action and mechanism of semiconductor photocatalysis on degradation of organic pollutants in water treatment: a review. Environ. Nanotechnol., Monit. Manag. 2019;12 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Morassaei M.S., Salavati-Niasari M. Eco-friendly synthesis of Nd2Sn2O7–based nanostructure materials using grape juice as green fuel as photocatalyst for the degradation of erythrosine. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019;167:643–653. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu P., Park B., Choi J., Thokchom B., Pandit A.B., Khim J. A review on heterogeneous sonocatalyst for treatment of organic pollutants in aqueous phase based on catalytic mechanism. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;45:29–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan G., Cai C., Yang S., Du B., Luo J., Chen Y., Lin X., Li X., Wang Y. Sonophotocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin by Bi2MoO6/FeVO4 heterojunction: Insights into performance, mechanism and pathway. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022;303 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng C., Chen Z., Jing J., Hou J. The photocatalytic phenol degradation mechanism of Ag-modified ZnO nanorods. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2020;8(9):3000–3009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S., Salavati-Niasari M. Facile route to synthesize zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) nanostructures: structural, optical and photocatalytic studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;216:545–551. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paumo H.K., Dalhatou S., Katata-Seru L.M., Kamdem B.P., Tijani J.O., Vishwanathan V., Kane A., Bahadur I. TiO2 assisted photocatalysts for degradation of emerging organic pollutants in water and wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;331 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dihom H.R., Al-Shaibani M.M., Radin Mohamed R.M.S., Al-Gheethi A.A., Sharma A., Khamidun M.H.B. Photocatalytic degradation of disperse azo dyes in textile wastewater using green zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized in plant extract: a critical review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022;47 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yaacob S.F.F.S., Jamil R.Z.R., Suah F.B.M. Sporopollenin based materials as a versatile choice for the detoxification of environmental pollutants—a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;207:990–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin J., Hutomo C.A., Kim J., Jang J., Park C.B. Natural pollen exine-templated synthesis of photocatalytic metal oxides with high surface area and oxygen vacancies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022;599 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen S., Shi Q., Jang T., Bin Ibrahim M.S., Deng J., Ferracci G., Tan W.S., Cho N., Song J. Engineering natural pollen grains as multifunctional 3d printing materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31:2106276. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H., Gomez I., Meredith J.C. Pollenkitt wetting mechanism enables species-specific tunable pollen adhesion. Langmuir. 2013;29(9):3012–3023. doi: 10.1021/la305144z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzvetkov G., Kaneva N., Spassov T. Room-temperature fabrication of core-shell nano-ZnO/pollen grain biocomposite for adsorptive removal of organic dye from water. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;400:481–491. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamboh M.A., Arain S.S., Jatoi A.H., Sherino B., Algarni T.S., Al-Onazi W.A., Al-Mohaimeed A.M., Rezania S. Green sporopollenin supported cyanocalixarene based magnetic adsorbent for pesticides removal from water: kinetic and equilibrium studies. Environ. Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeidner M., Matthews G., Shemesh D.O. Cognitive-social sources of wellbeing: Differentiating the roles of coping style, social support and emotional intelligence. J. Happiness Stud. 2016;17:2481–2501. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becherini S., Mitmoen M., Tran C.D. Natural sporopollenin microcapsules facilitated encapsulation of phase change material into cellulose composites for smart and biocompatible materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(47):44708–44721. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b15530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyab A.K.F., Sadek K.U. Microwave assisted one-pot green synthesis of cinnoline derivatives inside natural sporopollenin microcapsules. RSC Adv. 2018;8(41):23241–23251. doi: 10.1039/c8ra04195d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad N.F., Kamboh M.A., Nodeh H.R., Halim S.N.B.A., Mohamad S. Synthesis of piperazine functionalized magnetic sporopollenin: a new organic-inorganic hybrid material for the removal of lead (II) and arsenic (III) from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24:21846–21858. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyab A.K.F., Abdallah E.M., Ahmed S.A., Rabee M.M. Fabrication and characterisation of novel natural Lycopodium clavatum sporopollenin microcapsules loaded in-situ with nano-magnetic humic acid-metal complexes. J. Encapsulation Adsorpt. Sci. 2016;6:109. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akhsassi B., Bouddouch A., Naciri Y., Bakiz B., Taoufyq A., Favotto C., Villain S., Guinneton F., Benlhachemi A. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Zn3(PO4)2/ZnO composite semiconductor prepared by different methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021;783 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Yu S., Li Z.-H., He L.-L., Liu Q.-L., Hu M.-Y., Xu L., Wang X.-F., Xiang Z. Fabrication Z-scheme heterojunction of Ag2O/ZnWO4 with enhanced sonocatalytic performances for meloxicam decomposition: Increasing adsorption and generation of reactive species. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;405 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi L., Li B., Sun Y., Li S., Qi Q., Qin J., Sun H., Fang D., Wang J. Construction of coated Z-scheme Er3+: Y3Al5O12/Pd-CdS@BaTiO3 sonocatalyst composite for intensifying degradation of chlortetracycline hydrochloride in aqueous solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020;250 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Picasso G., Kou M.R.S., Vargasmachuca O., Rojas J., Zavala C., Lopez A., Irusta S. Sensors based on porous Pd-doped hematite (α-Fe2O3) for LPG detection. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014;185:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bekkouche S., Bouhelassa M., Ben Aissa A., Baup S., Gondrexon N., Petrier C., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O. Synergy between solar photocatalysis and high frequency sonolysis toward the degradation of organic pollutants in aqueous phase-case of phenol. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017;62:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang N., Zhang G., Chong S., Zhao H., Huang T., Zhu J. Ultrasonic impregnation of MnO2/CeO2 and its application in catalytic sono-degradation of methyl orange. J. Environ. Manage. 2018;205:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nazim M., Khan A.A.P., Asiri A.M., Kim J.H. Exploring rapid photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants with porous CuO nanosheets: synthesis, dye removal, and kinetic studies at room temperature. ACS Omega. 2021;6:2601–2612. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c04747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rad T.S., Khataee A., Pouran S.R. Synergistic enhancement in photocatalytic performance of Ce (IV) and Cr (III) co-substituted magnetite nanoparticles loaded on reduced graphene oxide sheets. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;528:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdi J., Sisi A.J., Hadipoor M., Khataee A. State of the art on the ultrasonic-assisted removal of environmental pollutants using metal-organic frameworks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022;424 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khataee A., Rad T.S., Nikzat S., Hassani A., Aslan M.H., Kobya M., Demirbaş E. Fabrication of NiFe layered double hydroxide/reduced graphene oxide (NiFe-LDH/rGO) nanocomposite with enhanced sonophotocatalytic activity for the degradation of moxifloxacin. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;375 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C., Sun R., Huang R., Wang H. Superior fenton-like degradation of tetracycline by iron loaded graphitic carbon derived from microplastics: synthesis, catalytic performance, and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;270 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rada S., Culea E., Rada M. Novel ZrO2 based ceramics stabilized by Fe2O3, SiO2 and Y2O3. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018;696:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Velempini T., Prabakaran E., Pillay K. Recent developments in the use of metal oxides for photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants in water—a review. Mater. Today Chem. 2021;19 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai T., Zeng W., Liu Y., Wang L., Dong W., Chen H., Xia X. A promising inorganic-organic Z-scheme photocatalyst Ag3PO4/PDI supermolecule with enhanced photoactivity and photostability for environmental remediation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020;263 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babu S.G., Aparna P., Satishkumar G., Ashokkumar M., Neppolian B. Ultrasound-assisted mineralization of organic contaminants using a recyclable LaFeO3 and Fe3+/persulfate Fenton-like system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jagaba A.H., Kutty S.R.M., Khaw S.G., Lai C.L., Isa M.H., Baloo L., Lawal I.M., Abubakar S., Umaru I., Zango Z.U. Derived hybrid biosorbent for zinc (II) removal from aqueous solution by continuous-flow activated sludge system. J. Water Process Eng. 2020;34 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dehghan S., Kakavandi B., Kalantary R.R. Heterogeneous sonocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using ZnO@Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposite: influential factors, reusability and mechanisms. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;264:98–109. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.