Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic placed the Philippines’ food and nutrition issues front and center. In this paper, we discuss the response of its government in addressing food and nutrition security at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and describe its implications on nutritional status. We also cite initiatives that address food accessibility and availability in the communities. Lastly, we explore the importance of nutrition security dimension in food security.

Methods: We analyze food and nutrition security issues in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic through online reports and news articles.

Results: The distribution of food and financial assistance in the country was extensive, albeit insufficient, considering the prolonged lockdown restrictions. Constantly changing community quarantine guidelines have affected the movement of food supply, delivery of health services, and household economic security. Nutrition programs, such as vitamin A supplementation, feeding for children, and micronutrient supplementation for pregnant women, had lower coverage rates, and by the latter half of 2020, the country had reached its highest recorded hunger rate. Cases of both undernutrition and overnutrition are predicted to rise because of dietary imbalances and a variety of factors. Conversely, community members and some local government units took it upon themselves to improve the food situation in their areas. The provision of food packs containing fresh fruits and vegetables was lauded, as it exemplified a conscious effort to deal with nutrition security.

Conclusion: Efforts to address food security have always focused on increasing accessibility, availability, and affordability, often neglecting the nutritional components of foods. Strategies that incorporate nutrition security into food security are much needed in the country, especially during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: food security, nutrition security, food assistance, Philippines, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Introduction

In 2020, the world was confronted with one of the most significant threats to food and nutrition security. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every aspect of the food chain from production, distribution, retail, to consumption. Movement and border restrictions have challenged the food supply chain globally. Governments scrambled to sustain food stock in the market while enforcing control measures that inevitably prolonged the replenishment of supplies. Owing to the looming food crisis, consumers felt the need to bulk purchase food items for personal sustenance. The dire condition only underscored the inequity already experienced by the vulnerable undernourished groups. The World Food Programme (WFP) has projected that 265 million people from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) will be affected by acute food insecurity due to the economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic1).

In this paper, we discuss the immediate response of the government of Philippines to addressing food and nutrition security at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and describe its implications on nutritional status. We also cite initiatives that address food accessibility and availability in the communities. Lastly, we explore further the importance of nutrition security dimension in food security.

Immediate Response

Following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11th, 20202), a Food Resiliency Task Force was urgently formed by the Department of Agriculture (DA)3). The unit’s function was to ensure the availability, affordability, accessibility, and safety of food supply in Metro Manila and other areas3). After a week, the landmark legislation Republic Act (RA) 11469, also known as the “Bayanihan to Heal as One Act”, was enacted to set forth COVID-19 response procedures, standards, and guiding principles4). This law authorizes the President of the Philippines to exercise temporary special powers to address the impact of the pandemic. Several stipulations have been included but the following are the ones pertaining to food. Among the special powers is the provision of financial assistance through the social amelioration package to 18 million low-income families for the purchase of food and basic commodities. Additionally, the law also necessitated the unhampered movement and operation of essential goods and services, especially in the food and agricultural sectors. Hoarding, profiteering, price manipulation, and product deception to food supply, distribution, and movement are penalized4).

With the law in place, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), together with local government units (LGUs), hastened assistance distribution to the most vulnerable populations5). Relief efforts were extensive, and most Filipinos reported receiving ayuda (Spanish for aid or assistance) either in the form of food or money, especially at the beginning of lockdown. A report by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) found that 96.6% of the households they surveyed received food assistance from their LGU or the private sector6). Of those households who received ayuda, half of them received it 2 to 3 times, while the other 42.6% received it more than 3 times6).

The usual food items provided were rice and cereals (93.2%), canned and other dry goods (82.6%), instant coffee (31.3%), and milk and other dairy products (14.0%)6). This food composition is expected from city or municipal social welfare units, which are the primary distributors of relief goods at the local level. It has been customary for food relief systems across the country to favor quantity over quality. The DSWD oversees donations and relief operations in the country. According to the department’s guidelines, their donation facilities prefer to accept non-perishable goods and foods that are not easily damaged. Conversely, donated food items with a shelf life of less than 30 days are subjected to additional paperwork before they can be allocated and utilized7). This practice makes it challenging to incorporate fresh foods, such as fruits and vegetables, in the DSWD relief packages.

In addition to food, most LGUs provide cash assistance to their residents. Of the households surveyed by the FNRI, 62.9% reported receiving cash assistance6). Although some households received both forms of ayuda, the cash assistance they received was still allotted to food. This was evidenced by the joint DSWD and World Food Program (WFP)’s Remote Household Monitoring Survey conducted between June and August 2020 to determine cash assistance expenditures8). Among the respondents, 92% reported using their cash assistance to buy food; furthermore, 67% opted to buy “less-preferred and less-expensive foods8)”.

The barter system has made an unexpected but timely comeback in the country. As livelihoods have been affected by the pandemic, cash flow has been slow in many households. In addition to borrowing money and buying food on credit, some Filipinos resorted to online bartering to obtain food6).

According to the iPrice Group, a meta-search website, Google searches for the terms “barter” and “barter trade” increased rapidly in April and May, immediately following the lockdown in March9). The group also recorded 85 barter groups on Facebook, 72% of which were outside of Metro Manila. Commonly bartered goods included food and grocery items, such as canned food, milk, fresh fruits, vegetables, and meat. By May, the more specific term “barter food” increased in searches by 300%9). Bartering experiences range from swapping shoes for chicken to trading baby clothes for six kilos of rice10). The ease of converting old items into food makes this a popular coping mechanism.

Apart from food and cash assistance, some LGUs also provided food production assistance to aid in farming costs. The FNRI survey revealed that only 12.5% of the respondents received food production assistance, most of whom belonged to areas with low COVID-19 infection rates6). Agriculture is one of the most vital sectors that must remain in operation. To further help local farmers, the Department of Agriculture (DA) appealed to the LGUs to buy local farmers’ produce11). This would be an advantageous deal for producers, consumers, and authorities. Farmers would be able to secure a market for their crops, while consumers are guaranteed the freshest produce. At the same time, movement and delivery logistics are minimized when produce is outsourced from the nearest farmers. The DA has established linkages between the LGU in metropolitan areas and local farmer producers to facilitate the operation11).

However, in some cases, the supply of crops eventually exceeded the demand from the LGUs. Some farmers struggled with the oversupply of certain crops, being consequently compelled to throw them away12). In other instances, changes in the enforcement of community quarantine to stricter measures jeopardized farming businesses. In Ifugao province, one farmer was forced to dump his tomato harvest because the supposed buyers were unable to pass through the “no vaccination, no entry” checkpoints along the way13).

Nutritional Status

Meanwhile, the effects of COVID-19 on the implementation of four nutrition-specific programs were also evident in the FNRI report. Generally, these programs had lower coverage rates in 2020 (during the COVID-19 pandemic) than in 2019, prior to the pandemic. The coverage rates were reduced by at least 16% for Vitamin A supplementation to as much as about 45% for supplementary feeding6). For Operation Timbang (OPT) Plus, an annual growth monitoring among children showed that the coverage rate decreased from 83.0% to 51.1%6). In other words, 48.9% of children aged 0–12 years were not weighed or measured for height6). The reason for non-participation in OPT Plus was mainly lockdown restrictions, and no health workers visited them6). Additionally, the report revealed that the majority of children (88.1%) across the different risk areas did not receive supplementary feeding6). Among those who received supplementary feeding (11.9%), the average duration of feeding was approximately 12 days, wherein the children mostly received family food packs and cooked food6). Furthermore, only 10.6% of children aged 6–60 months receive micronutrient powder6).

For micronutrient supplementation availed by pregnant women, the reports showed no data on the coverage rate before the pandemic, but it mentioned that 14.2% of them did not take supplements6). The top two reasons stated in the report were (1) they do not have money to buy vitamins (28.6%), and (2) they are waiting for the prescription of supplements (28.6%)6). Regarding the dietary supplementation, 92.6% of pregnant women did not receive it6).

For breastfeeding practices, the pandemic did not drastically affect mothers’ breastfeeding practices. The rate of breastfeeding increased from 2019 to 2020, although the difference was not statistically significant. The same trend was observed in the rate of complementary feeding6).

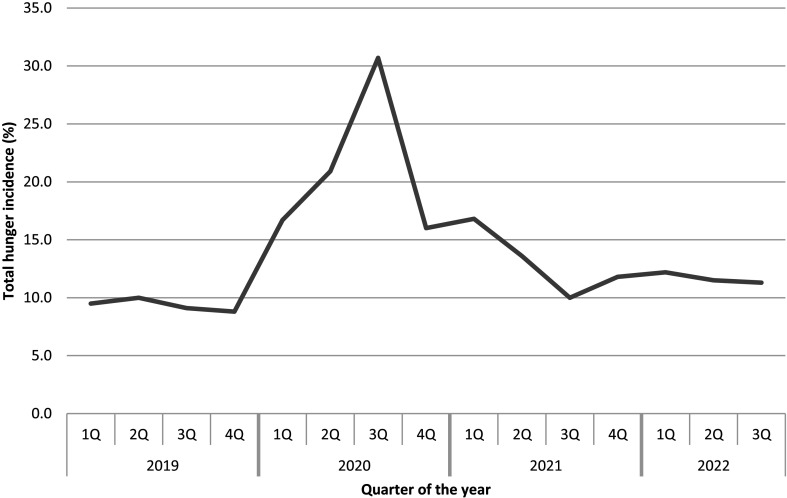

The pandemic intensified food insecurity in the country, leaving vulnerable groups more susceptible to hunger. According to the Social Weather Stations (SWS), the incidence of self-reported involuntary hunger rose to an all-time high rate of 30.7% in the middle of 202014). As shown in Figure 1, the subsequent hunger incidences fell considerably by 2021 and 2022 but remained above pre-pandemic levels15).

Figure 1.

National total hunger incidence per quarter (2019–2022)15).

Stunting is also expected to increase because of pandemic-related disruptions in healthcare delivery, food systems, and the economy. As previously mentioned, the lockdown made it difficult to implement essential maternal and child health services. Furthermore, not only movement restrictions but also the sudden loss of livelihood have reduced people’s access to nutritious foods. In the Philippines, 30% of children under 5 years of age are stunted; this places the country among the top 10 countries with a high stunting prevalence16). A study by Osendarp et al. estimated the stunting of 2.6 million additional children worldwide by 2022 owing to interruptions brought about by COVID-1917).

As the pandemic continues, people are accustomed to a lifestyle of increased technology dependency and reduced physical activity. According to a report, 85% of Filipino adolescents were not engaging enough in physical activities before the pandemic18). Therefore, it is not difficult to imagine that prolonged home confinement would result in heightened sedentariness. The prevalence of obesity had been steadily increasing, especially in Asia, even before the pandemic19). According to a bulletin by the Philippine News Agency, the number of overweight Filipino adolescents has tripled in the last 15 years, with most of them living in urban areas20).

However, being overweight and obese is not only confined to households with abundant food. Food-insecure families are also at risk of obesity21). In this population, people tend to stretch out their earnings to cover longer days, thus resorting to cheap, usually nutrient-poor foods to avoid being completely hungry in the following days. This situation has been described as nutritional insecurity in the presence of abundant calories22).

Community Initiatives

Healthy food packs, mobile markets, and community pantries were notable initiatives to address food and nutrition security in the communities. The common motivation behind such ventures is to make food accessible and available to as many households as possible.

As mentioned in the FNRI survey, pandemic food packs mainly consisted of non-perishable food items6). Even so, there have been several instances wherein fresh foods have been prioritized in the distribution of food packs in some LGUs. These efforts were recognized and lauded by the National Nutrition Council (NNC) on their Facebook page23).

Mandaluyong City was one of the earliest LGUs to supply fresh vegetables in food relief packs24). “NUTRI-Bags” containing a variety of fruits and vegetables, eggs, micronutrients, and iodized salt, were handed out to households with 6-to 59-month-old children and to pregnant or lactating mothers in the Municipality of Talacogon in Agusan Del Sur25). Similarly, Barangay Bagacay in Romblon supplemented the usual bag of rice and canned goods with fish, pumpkin, and tomatoes26). Some LGUs in Maguindanao and the Zamboanga Peninsula then distributed their local farmers’ harvests to their residents27). Meanwhile, some municipalities in the Cagayan Valley handed out vegetable seeds, seedlings, beans, and live chickens28).

Mobile markets or palengke (in Tagalog) is another local government initiative that emerged at the height of the lockdown. Pasig, Valenzuela, and Quezon were among the first LGUs to dispatch mobile markets to their barangays. The Pasig local government introduced mobile markets in the form of medium-sized trucks to limit foot traffic in their public markets, especially the Pasig Mega Market, which is one of the largest wet markets in Metro Manila29). Meat and produce offered in the mobile markets were also sourced from Pasig Mega Market vendors and sold at the same price29). Valenzuela City’s “Market on Wheels” made use of their electronic tricycles (e-trike) that were refashioned into mini roving stores30). This initiative was launched to reduce market congestion and maintain social distancing30). Meanwhile, the Quezon City government transformed a jeepney into a mobile market and partnered with farmers to sell fresh produce, meat, and dairy products directly to the public at much lower prices than markets or groceries31).

The concept of community pantries and food banks is not new. However, the sense of community and mutual aid brought about by the emergence of community pantries, especially during the pandemic, have been remarkable. Initially seen along the street of Maginhawa, Quezon City, in April 2021, what was once an idea to help pandemic-stricken families has now expanded to a national movement32). This initiative goes by a simple give and take principle—give according to your means and take according to your needs32). In a matter of weeks, individuals, companies, and even schools were forming community pantries in their own areas32). The goods were mostly vegetables, rice, and canned foods, while other pantries included COVID-19 essentials, such as masks32). Some organizers even coordinated with local farmers and bought their surplus crops32).

Nutrition Dimension

In principle, adequate nutrition should be a key element in attaining food security. Although this component seems to be implied in the definition of food security, the nutrition dimension is often overlooked in practice33), with food security being solely attributed to the availability and accessibility of food commodities34).

As similar notions were raised in other countries, a multi-stakeholder effort to address nutritional outcomes in national and sectoral food and nutrition security strategies was proposed in the Road Map for Scaling-Up Nutrition (SUN)35). Eventually, a definition for nutrition security was introduced by the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) of the United Nations (UN) in 2012, wherein nutrition security was described as a condition that “exists when all people at all times consume food of sufficient quantity and quality in terms of variety, diversity, nutrient content, and safety to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life, coupled with a sanitary environment, adequate health, education and care36)”.

In the Philippines, food security issues are separated from nutrition issues and are often viewed from an agricultural lens37). For the longest time, efforts have focused towards achieving available and accessible foods. Certainly, these are prerequisites to good nutrition. However, it is also important to know that food security will not be realized if there is no nutrition security. If foods (especially, nutrient-rich foods) are not properly allocated and utilized, such as in the overabundance or misutilization of some crops, an imbalance of the food system occurs. This, in turn, may lead to economic effects (stability of food prices) that have implications for food insecurity.

As nutrition security has become more widely discussed in the scientific community, it is imperative that its concepts are instilled and translated into real-life settings. Administrators, policymakers, and other stakeholders need to be more aware of the nutritional aspects of food security to effectively guide food and nutrition strategies.

Conclusion

Indeed, the government of Philippines was quick to respond to a potential food system disruption at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, certain mechanisms are still lacking in terms of sustaining a food system that is responsive to the nutritional needs of people, particularly of the vulnerable groups. In emergency situations, such as a pandemic, it is crucial that the food supply chain remains operational. Furthermore, it is equally important that nutritious foods be the preferred type of food for distribution. Community experiences show that integrating fresh food and nutrition in food relief efforts is possible. Linking local farmers to food banks is also a sustainable solution that needs to be reinforced. Lastly, changing the food security landscape to one that simultaneously tackles nutrition security would have more beneficial health and economic outcomes in the country.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.World Food Program. COVID-19 will double number of people facing food crises unless swift action is taken. 2020. Available from: https://www.wfp.org/news/covid-19-will-double-number-people-facing-food-crises-unless-swift-action-taken.

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

- 3.Department of Agriculture. Special Order No. 335 Series of 2020 Creation of the COVID-19 Food Resiliency Task Force. 2020. Available from: https://www.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/so335_s2020.pdf.

- 4.Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 11469: Bayanihan to Heal as One Act. 2020. Available from: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/03mar/20200324-RA-11469-RRD.pdf.

- 5.Philippine News Agency. Gov’t to provide food to families during quarantine period. March 2020. Available from: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1097188.

- 6.Food and Nutrition Research Institute. Rapid Nutrition Assessment Survey on Food Security, Coping Mechanisms, and Nutrition Services Availed during COVID-19 Pandemic in Selected Areas in the Philippines. Available from: http://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/site/uploads/RNAS%20Virtual%20Dissemination%20to%20Partners.pdf.

- 7.Department of Social Welfare and Development. Administrative Order No. 51 Series of 2003 Omnibus Guidelines and Procedures on the Maintenance and Operation of the National Resource Operations Center (NROC). 2003. Available from: https://www.dswd.gov.ph/issuances/AOs/AO_2003-051.pdf.

- 8.Cudis C. Survey says SAP recipients use aid to buy food, pay off debts. 2020. Available from: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1117665.

- 9.Mendoza M. “I-barter mo na!”—The resurgence of bartering in the Philippines. Available from: https://iprice.ph/trends/insights/the-resurgence-of-bartering-in-the-philippines.

- 10.Agence France-Presse. Will trade for food: online bartering soars in virus-hit Philippines. 2020. Available from: https://www.france24.com/en/20200902-will-trade-for-food-online-bartering-soars-in-virus-hit-philippines.

- 11.Department of Agriculture. DA appeals to LGUs: buy farmers’ produce. 2020. Available from: https://www.da.gov.ph/da-appeals-to-lgus-buy-farmers-produce/.

- 12.Palo ASM, Rosetes MA, Cariño DP. 7. COVID-19 and food systems in the Philippines in COVID-19 and food systems in the Indo-Pacific: An assessment of vulnerabilities, impacts and opportunities for action. Technical Report, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). 2020. Available from: https://www.aciar.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/ACIAR%20TR096%20COVID19%20impacts%20on%20food%20systems_0.pdf.

- 13.Department of Agriculture. DA-CAR looks into unsold tomatoes in Tinoc, Ifugao. 2021. Available from: https://www.da.gov.ph/da-car-looks-into-unsold-tomatoes-in-tinoc-ifugao/.

- 14.Social Weather Stations. Third Quarter 2021 Social Weather Survey: Hunger falls to 10.0% of families in September 2021. 2021. Available from: http://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/?artcsyscode=ART-20211206105401.

- 15.Social Weather Stations. Third Quarter 2022 Social Weather Survey: Hunger hardly moves from 11.6% to 11.3%. October 2022. Available from: https://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/?artcsyscode=ART-20221029123738.

- 16.World Bank Investing in Nutrition Can Eradicate the “Silent Pandemic” Affecting Millions of Poor Families in the Philippines. 2021. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/06/15/investing-in-nutrition-can-eradicate-the-silent-pandemic-affecting-millions-of-poor-families-in-the-philippines-world-ba.

- 17.Osendarp S, Akuoku JK, Black RE, et al. The COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate maternal and child undernutrition and child mortality in low-and middle-income countries. Nat Food 2021; 2: 476–484. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00319-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatum M. The impact of a year indoors for Filipino children. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021; 5: 393–394. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00141-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC)Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017; 390: 2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dela Cruz RC. DOH, int’l orgs call for action against childhood obesity. 2021. Available from: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1132562.

- 21.Littlejohn P, Finlay BB. When a pandemic and an epidemic collide: COVID-19, gut microbiota, and the double burden of malnutrition. BMC Med 2021; 19: 31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01910-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwalla N, El Labban S, Bahn RA. Nutrition security is an integral component of food security. Front Life Sci 2016; 9: 167–172. doi: 10.1080/21553769.2016.1209133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Nutrition Council (Official) (Facebook page). 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/nncofficial.

- 24.Mandaluyong City Public Information Office (Facebook page). “Sa layon ni Mayor Menchie Abalos na ang maihahatid na food supplies…”. 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=219899629376467&id=100527757980322#.

- 25.National Nutrition Council Caraga Region (Facebook page). “The Municipality of Talacogon Nutrition Committee chaired by Mayor Pauline Marie R. Masendo through the Nutrition Office distributed a ‘NUTRI-Bag’…”. 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=2726677514067466&id=275233879211854.

- 26.Romblon News Network (Facebook page). “LOOK: Namigay rin ng libreng isda sa Brgy. Bagacay, Romblon…”. 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/RomblonNews/posts/2903440156436346#.

- 27.National Nutrition Council (Official) (Facebook page). “Kahanga-hangang inisyatibong pang-nutrisyon ang ipinakita ng mga lokal na pamahalaan ng Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao o BARMM...”. 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/nncofficial/posts/pfbid036xSDec7meiEgc2Eep8tju919PzbWHmgHF2XUwFP2hqLKdyhAg65PtffoACdnauhXl?__cft__[0]=AZUPSqiEYugmxKd4y4_voySDKJgQxgmaQT1bIWcsFF13cu3ja2jMtRnktFg0cxUuDqQTLNevKdOVFzPMNo4MkMwN7YpL4bZCLBwHQl813R8JUx75jz0kq8N5EiJ9T2OtNAQ&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R.

- 28.National Nutrition Council (Official) (Facebook page). “Ilang lokal na pamahalaan ng Cagayan Valley Region ang namigay ng vegetable seeds at seedlings, live chicken at beans bilang parte ng relief packs…”. 2020. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/nncofficial/posts/pfbid025t3CwNzhPAwCjpvvfdtmNsnZDc1pBcvwKkDKaq76bcYQeGJGbTCtUFDKxXwbceHxl.

- 29.Kabagani LJ. Pasig City’s ‘mobile palengke’ boosts social distancing. 2020. Available from: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1097797#:~:text=MANILA%E2%80%94The%20Pasig%20City%20government,of%20the%20enhanced%20community%20quarantine.

- 30.Aguarino J. “Market on Wheels” brings fresh veggies and meat, basic goods closer to Valenzuelanos. 2020. Available from: https://www.valenzuela.gov.ph/article/news/13384.

- 31.Quieta R. QC Fresh Market on Wheels brings the market closer to the barangays. 2020. Available from: https://www.gmanetwork.com/entertainment/celebritylife/food/62294/qc-fresh-market-on-wheels-brings-the-market-closer-to-the-barangays/story.

- 32.Suazo J. What the community pantry movement means for Filipinos. 2021. Available from: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/2021/4/19/community-pantry-filipinos-pandemic.html.

- 33.Mozaffarian D, Fleischhacker S, Andrés JR. Prioritizing nutrition security in the US. JAMA 2021; 325: 1605–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philippine Statistics Authority. Philippine Food Security Information System (PhilFSIS). Available from: https://openstat.psa.gov.ph/Featured/philfsis.

- 35.Scaling Up Nutrition Road Map Task Team A Road Map for Scaling-Up Nutrition (SUN) First Edition. 2010. Available from https://scalingupnutrition.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/SUN_Road_Map.pdf.

- 36.Committee on World Food Security. Thirty-ninth Session COMING TO TERMS WITH TERMINOLOGY Food Security, Nutrition Security, Food Security and Nutrition, and Food and Nutrition Security. 2012. Available from: https://www.unscn.org/files/cfs/term_EN.pdf.

- 37.Briones R, Antonio E, Habito C, et al. Strategic review: Food Security and Nutrition in the Philippines. 2017. Available from: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000015508/download/?_ga=2.129489612.1710044684.1662017425-463897737.1661761691.