Graphical abstract

Keywords: Emulsion, Shrimp oil, Hepatopancreas, Fish myofibrillar protein, Ultrasonication, Stability

Highlights

-

•

Fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) was ultrasonicated at 40% amplitude for 15 min.

-

•

Ultrasonication (US) induced degradation of myosin heavy chain but not actin.

-

•

Ultrasonication altered the β-sheet and the random coil of FMP.

-

•

Ultrasonicated FMP (UFMP) was more adsorbed at the interface than FMP.

-

•

UFMP improved emulsifying properties and storage stability of emulsion.

Abstract

Effects of ultrasonication at different amplitudes (40% and 60%) and time (5, 10, and 15 min) on the physicochemical and emulsifying properties of the fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) were investigated. Solubility, surface hydrophobicity, and emulsifying properties were augmented when FMP was subjected to ultrasonication at 40% amplitude for 15 min (p < 0.05). Protein pattern study revealed that augmenting amplitude and duration of ultrasound treatment reduced band intensity of myosin heavy chain. Ultrasound treatment facilitated the adsorption of FMP on oil droplets as indicated by the increases in both adsorbed and interfacial protein contents (p < 0.05). Ultrasound-treated FMP (UFMP) sample showed the alteration in chemical bonds as depicted by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra. Ultrasound treatment altered the β-sheet and random coil of FMP. During storage for 30 days at 30 °C, UFMP stabilized shrimp oil (SO)-in-water emulsion had higher turbidity but lower d32, d43, and polydispersity index than emulsion stabilized by untreated FMP (p < 0.05). Furthermore, emulsion stabilized by UFMP had lower flocculation and coalescence indices (p < 0.05). Microstructure observation revealed smaller droplet sizes and higher stability of droplets in emulsion stabilized by UFMP. Confocal laser scanning microscopic images demonstrated a monodisperse emulsion stabilized by UFMP. This coincided with higher viscosity and modulus values (G' and G″ ). Emulsion stabilized by UFMP exhibited viscous, shear-thinning, and non-Newtonian behavior and no phase separation occurred during storage. Therefore, ultrasonication was proven to be a potential method for enhancing the emulsifying properties of FMP and improving the stability of SO-in-water emulsion during prolonged storage.

1. Introduction

Functional foods have become a major trend for promoting health and reducing the risk of diseases. Globally, nutraceutical and functional ingredients from seafood processing wastes have gained remarkable interest [1]. Shrimp oil extracted from hepatopancreas, the byproduct of shrimp processing industries, has gained increasing attention as it has high content of astaxanthin and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) [2]. PUFA lowers the risk of cardiovascular diseases and Alzheimer’s disease. It also possesses excellent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [3]. Astaxanthin, a pigment abundant in crustaceans, has superior antioxidant activity. However, due to rapid oxidative deterioration, the direct inclusion of shrimp oil into food products has been limited [4]. To overcome this drawback, several techniques have been employed including emulsion-based encapsulation, the addition of antioxidants, and the application of modified atmosphere packing (MAP), etc. Emulsion-based encapsulation is a promising technique to reduce oxidation and mask undesirable odor and flavor of marine oil [5].

Emulsion is widely used in several food products such as ice cream, salad dressing, mayonnaise, etc. Nevertheless, the shelf-life of emulsion-based food products was shortened owing to their susceptibility to phase separation [6]. Therefore, emulsifiers are employed for emulsion stabilization. In addition, natural emulsifier has additional advantages such as biodegradability, sustainability, and bio-functionality [7]. Myofibrillar protein has been used widely in foods, owing to its wide range of functionalities along with its high nutritive value. About 66–77% of the total protein in fish meat is composed of myofibrillar proteins [8]. Fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) can act as an emulsifier in emulsion-based meat products due to its amphiphilic characteristics and surface-active capabilities [9]. However, FMP has a high molecular weight and low solubility, thus limiting its diffusion from the aqueous phase and its adsorption at the interface of an oil-in-water emulsion [10]. Therefore, an effective modification of FMP is required to enhance the emulsifying property and ensure the long-term stability of FMP-stabilized SO-in-water emulsion.

Ultrasonication is a non-thermal processing technique using ultrasound. Ultrasonication was reported to enhance the functional properties of various proteins [11]. It has been known to partially unfold the tertiary structure of protein and expose hydrophobic domains. This might enhance protein migration to the interface of an oil-in-water emulsion. Furthermore, ultrasound improved emulsifying properties of a protein by reducing its size and increasing its solubility [12]. It is also eco-friendly, cost-effective, and easy to operate. Ultrasonication is more efficient than high-pressure homogenization and microfluidization [13]. Therefore, ultrasound has been widely adopted in large-scale food processing industries for various purposes such as extraction of bioactive compounds, reduction in particle size, especially in emulsion or liposomes, etc. [14].

In addition, FMP differs from other proteins found in milk, plant and land animal, as it exhibits lower thermal and chemical stability [15]. SO has red color due to high content of astaxanthin. Thus, SO is a suitable ingredient in emulsion-based food products e.g., mayonnaise. In such products, SO can mimic the color of egg yolk, while FMP can act as an emulsifier. Nevertheless, no investigations have been done on the application of ultrasound-treated FMP (UFMP) for stabilizing SO-in-water emulsion. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of ultrasound under diverse operating conditions on the physicochemical and emulsifying properties of FMP. Stability of the emulsion stabilized by FMP and UFMP prepared under the optimum condition was also monitored during the storage in oxygen-free package at 30 °C for 30 days.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from Sigma (St. Louis. MO, USA), except isopropanol and hexane, which were bought from ACI Lab-scan (Bangkok, Thailand). Soybean oil was purchased from a local supermarket in Hat Yai, Thailand.

2.2. Extraction of oil from the hepatopancreas of shrimp

Frozen hepatopancreas (-20 °C) from Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) was gifted from Seafresh Industry Public CO., Ltd. (Chumphon, Thailand). After thawing at 4 °C overnight, hepatopancreas was blended using a blender (Panasonic, Model MX-898 N, Berkshire, UK). As directed by Gulzar and Benjakul [5], shrimp oil (SO) was recovered from the hepatopancreas paste. Firstly, hepatopancreas paste (100 g) and hexane/isopropanol mixture (1:1, v/v) (500 mL) were homogenized for 2 min at 9500 rpm using an IKA Labortechnik homogenizer (Selangor, Malaysia). Secondly, the homogenate was centrifuged at 4 °C (3000 × g, 15 min) in a refrigerated centrifuge (Hitachi Koki Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and the supernatant was then passed through Whatman filter paper No.4. The resulting filtrate was poured into a separating funnel and mixed well with an equal volume of distilled water for three times. Anhydrous sodium sulphate (2–5 g) was added in the upper hexane fraction, which mainly contained SO. Finally, the evaporation of hexane was done at 40 °C with the aid of an EYELA rotary evaporator N-1000 (Tokyo Rikakikai, CO., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The acquired SO was transferred to an amber vial and flushed with nitrogen to remove any residual solvent. Finally, the vial was securely closed and stored at -40 °C.

2.3. Fish myofibrillar protein preparation

Deceased Asian sea bass (3–4 h after capture) were purchased from a vendor in Hat Yai. Myofibrillar protein from fish meat was extracted [16]. The acquired pellet was then dispersed in distilled water and homogenized (13,000 rpm; 1 min). The pH of the homogenate was gradually adjusted to 3.0 using 50% acetic acid with continuous stirring for 10 min. Then, the homogenate was stirred at a low speed (4 °C, overnight) for complete solubilization. Centrifugation of the mixture was done at 4 °C (10,000 × g; 20 min) to remove undissolved matters. The obtained supernatant was used as a fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) solution. FMP at 15 mg/mL was the optimal concentration to produce a stable SO-in-water emulsion [17]. Protein content of FMP was determined by the Biuret method using bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0–10 mg/mL) as standard [18].

2.4. Ultrasound treatment of fish myofibrillar protein

FMP solution was subjected to ultrasonication (Sonics, Model VC750, Sonic and Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) at a frequency of 20 kHz ± 50 Hz and high-intensity power of 750 W. Varying amplitudes (40% and 60%) for different time (5, 10, and 15 min) with a fixed pulse mode (2 s-on and 4 s-off) were used. To maintain the temperature below 10 °C, the FMP solution was placed in iced bath during ultrasound treatment. Then, ultrasound-treated FMP (UFMP) solution was kept at 4 °C for further analyses. FMP solution without ultrasound treatment was used as the control.

2.5. Preparation of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion

FMP and UFMP solutions were used as emulsifiers to prepare SO-in-water emulsions [19]. Firstly, SO was mixed with SBO (v/v) at a ratio of 30:70 to reduce the fishy odor of SO [20]. In brief, the SO/SBO mixture (10 mL) was homogenized using an overhead homogenizer (T25 Ultra Turrax, IKA Labortechnik, Selangor, Malaysia) with FMP or UFMP solution (30 mL) at 13,500 rpm for 5 min. The pause for 30 sec was employed after every 1 min of homogenization.

2.6. Characterization of ultrasound-treated fish myofibrillar protein

2.6.1. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-PAGE was used to analyze the protein patterns of FMP and UFMP [21]. The samples were diluted to have a protein content of 6 mg/mL with 5% SDS (w/v) and mixed with reducing buffer at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. The mixture was heated at 95 °C for 2 min using a temperature-controlled water bath (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany). The sample (15 µg protein) was loaded onto polyacrylamide gel (4% stacking gel and 10% separating gel). After electrophoresis at 15 mA, the gel was stained and destained. High molecular weight protein standard including myosin (206 KDa), β-galactosidase (116 KDa), phosphorylase B (97.4 KDA), serum albumin (66.2 KDA) and ovalbumin (45 KDa) was used to estimate the molecular weight of proteins (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Richmond, CA, USA).

2.6.2. Solubility

Solubility of FMP solutions was determined using the centrifugation method as guided by Sha et al. [22]. Protein content in the solution and in the supernatant was assessed using the Biuret method. Solubility was expressed in percentage (%).

2.6.3. Surface hydrophobicity

For surface hydrophobicity, samples (5 mg/mL) in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.6 mM NaCl were further diluted to 0.125–1 mg/mL using the same buffer. Subsequently, the samples were added with 20 µL of 8 mM 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The fluorescence intensity of ANS-protein conjugate was determined at the excitation and emission wavelength of 374 nm and 485 nm, respectively using a spectrofluorometer (RF-15001, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The initial slopes of relative fluorescence intensity and protein concentrations were used to calculate the protein surface hydrophobicity and expressed as SoANS [23].

2.6.4. Emulsifying properties

Emulsion activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) were determined [24]. The aliquots from the bottom of the tubes containing emulsion were drawn at 0 and 30 min. Subsequently, the aliquots were diluted 1000-fold using 1% (v/v) acetic acid containing 0.1% SDS (AA-SDS). The mixture was vortexed for 5sec to prevent flocculation. The absorbance at 500 nm was read with a spectrophotometer (UV-160, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). EAI and ESI were computed as follows:

where A0 and A30 are absorbances at 0 and 30 min, respectively; DF is the dilution factor; L denotes the path length of the cuvette (m); C is the initial protein concentration (g/mL); ∅ is the oil volume fraction (0.25); Δt is 30 min.

2.6.5. Adsorbed protein content (APC) and interfacial protein content (IPC)

Ultrasound treatment with optimum amplitude and time yielding FMP with the highest solubility, surface hydrophobicity, and emulsifying properties were selected for APC and IPC analyses. APC and IPC of freshly prepared emulsion stabilized by FMP and selected UFMP were determined according to Liang and Tang [25]. A 5 mL of the emulsion was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 h at 25 °C. Oil droplets in the top phase were removed and unabsorbed protein content in the bottom phase was analyzed (CS). Similarly, the same condition was employed to centrifuge the same volume of FMP and the selected UFMP solutions to determine soluble protein content in the supernatant (CA) using the Biuret method.

where CI stands for the initial concentration of FMP and UFMP before centrifugation; d32 is the surface-weighted mean diameter.

2.6.6. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra

Prior to analysis, FMP and the selected UFMP were freeze-dried. FTIR of FMP and selected UFMP powders were used for chemical bond or functional group characterization. FTIR spectrometer (Equinox 55, Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with an attenuated total reflection (ATR) diamond crystal cell was used [26]. Spectra were acquired (wavenumber: 400 – 4000 cm−1) with 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1 at 25 °C and analyzed using OPUS 3.0 (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany).

2.7. Characterization of SO-in-water emulsion stabilized by FMP and the selected UFMP stored at days 0 and 30

Firstly, FMP and UFMP solutions were prepared with the addition of 0.03% (w/w) Na-azide to prevent microbial deterioration during storage. Secondly, emulsions were prepared and stored in polypropylene containers, nitrogen flushed, and tightly capped. The samples were kept for 30 days at room temperature (28–30 °C). Measurements were done at day 0 and day 30 of the storage.

2.7.1. Turbidity

Emulsion stability was assessed via the turbidimetric method [27]. The sample was diluted 1000-fold with AA-SDS before analysis. The absorbance of the diluted emulsion was read at 500 nm. Using the following formula, turbidity was determined and presented as nephelometric turbidity units (NTU).

where A is the absorbance at 500 nm, L is the path length of the cuvette (m) and 2.303 is a constant of the natural logarithm (e).

2.7.2. Droplet size and polydispersity index (PDI)

Surface-weighted mean diameter (d32), volume-weighted mean diameter (d43), and PDI were assessed using a Zeta potential analyzer (ZetaPlus, Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, Holtsville, NY, USA) [28]. The emulsions were diluted 100-fold with 1% AA-SDS to dissociate the flocculated droplets. The refractive index (1.330) and absorption (0.001) were applied according to the recommendation of the manufacturer.

2.7.3. Flocculation index (Fi) and coalescence index (Ci)

The Fi and Ci indices were computed based on the d43, measured without and with 1% SDS (w/v) as described by Patil and Benjakul [29].

where, d43 - SDS and d43 + SDS is diameter of droplets in the absence and presence of 1% SDS, respectively and d43 + SDSi and d43 + SDSf is diameter of the droplet in the presence of 1% SDS at the initial (i) and final (f) day of storage, respectively.

2.7.4. Microstructure

An optical microscope with a camera (Olympus IX70 with DP50, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine the microstructure of emulsion. Emulsion (20 µL) was dropped on microscope slide and carefully covered with a cover slip to create a flat layer of uniform thickness. Observations were made at 40 × magnification.

2.7.5. Confocal laser scanning microscopic (CLSM) images

CLSM analysis was performed with confocal microscope (Model FV300; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) [30]. The emulsion sample was mixed with Nile blue A (1:10; v/v) before the analysis. Then, a 50 µL mixture was spread over a microscope slide and covered with a cover slip. The fluorescence mode with a Helium-Neon Red laser (HeNe-R) was used for lipid analysis at excitation and emission wavelength of 533 nm and 630 nm, respectively. Magnification of 400 × was used.

2.7.6. Viscoelastic properties

Emulsion was assessed for the viscoelastic property using a rheometer with parallel geometry (60 mm diameter, and 1 mm gap) (RheoStress RS 1, HAAKE, Karlsruhe, Germany) as directed by Rajasekaran et al. [24]. A strain sweep (0.1 to 100%) was performed in the linear viscoelastic range with a fixed frequency (1.0 Hz). The frequency sweep (0.1 to 10 Hz) was conducted with a constant strain (0.5%) across the linear region. As a function of frequency, the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus ( G″ ) were computed. Viscosity was measured with increasing shear rate (1–100 s−1) within 2 min.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments and analyses were carried out in triplicate. Completely randomized design (CRD) was adopted for the entire studies, including ultrasound treatment of FMP as well as storage stability. Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan's multiple range test was used to compare means. Data analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Science software (SPSS 23 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of ultrasonication on physicochemical properties of FMP

3.1.1. Protein patterns

Protein patterns of FMP and UFMP with different amplitudes for various durations are presented in Fig. 1.Overall, FMP had myosin heavy chain (MHC) and actin as dominant proteins with molecular weight (MW) around ∼ 205 kDa and ∼ 45 KDa, respectively. When comparing to untreated FMP, UFMP showed a drastic decrease in MHC band intensity after ultrasound treatment. Among UFMP samples, a decrease in MHC band intensity was apparent with increasing amplitude and duration of ultrasound treatment. This was attributed to the cavitation effect of ultrasound which plausibly destroyed some non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions of FMP molecules. Moreover, ultrasonication could dissociate MHC dimer to monomer. Furthermore, those dissociated monomers tended to break down into smaller fragments with the augmenting amplitude and duration of ultrasound treatment. Recently, Deng et al. [31] documented the reduction in MHC band intensity of Coregonus peled fish protein with increasing intensity and ultrasonication time. In contrast, the intensity of the actin band remained unchanged after ultrasound treatment. This observation was in line with the finding of Saleem and Ahmad [32] who found that actin was more resistant to hydrolysis induced by ultrasonication. Hence, the result suggested that ultrasound played a profound role in MHC degradation of FMP.

Fig. 1.

SDS-PAGE protein pattern of fish myofibrillar protein and those subjected to ultrasonication with different conditions. C: untreated-FMP (control). Numbers represent amplitude (%) and operation time (min), respectively. HW denoted high molecular weight protein standard.

3.1.2. Solubility

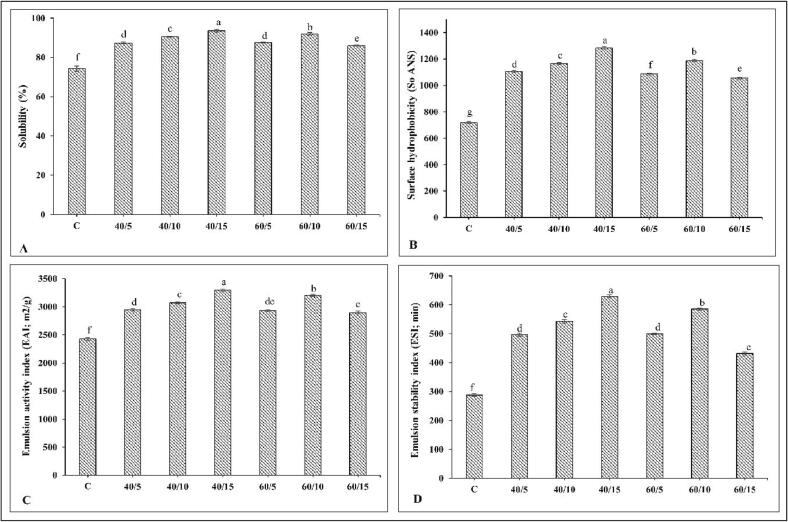

Solubility of FMP and UFMP prepared at varying amplitudes and duration of ultrasound treatment is presented in Fig. 2A. Solubility is the prerequisite in determining functional properties of food proteins and is governed by denaturation and oxidation of proteins [33]. In the present study, the pH shift process or acid solubilization process was implemented to dissolve FMP. At acidic pH, protein becomes positively charged, facilitating the repulsion and solubilization of FMP. Overall, ultrasound treatment increased the solubility of FMP (p < 0.05). The highest solubility was noticed in FMP treated with ultrasound at 40% amplitude for 15 min (p < 0.05), which exhibited 19.26% increase in solubility, compared to that of the control. For FMP treated with ultrasound at 40% amplitude, solubility gradually increased with augmenting ultrasonication time (5 to 15 min) (p < 0.05). Increased solubility was attributed to the exposure of internal hydrophilic groups with increasing treatment time. Moreover, the intense physical force included mechanical shear and shockwaves, along with cavitation generated during ultrasonication, might disrupt some bonds. This resulted in dissociation of protein and reduction in the size of FMP, thereby promoting protein-water interactions. Similarly, the increased solubility of beef proteins was noticed by Amiri et al. [9], when ultrasonication time was increased from 10 to 30 min at 300 W. On the other hand, ultrasound treatment at 60% amplitude resulted in decreased solubility of FMP when the treatment duration exceeded 10 min (p < 0.05). This might be probably due to the over-processing effect of ultrasound. Excessive turbulence generated by the ultrasound more likely caused the denaturation and more exposure of hydrophobic groups of FMP molecules, resulting in protein–protein interactions via hydrophobic interaction. This led to protein aggregation and weakened protein-water interactions as witnessed by the decreased solubility [34]. Generally, solubility of protein is the result of the balance between hydrophobic interactions and ionic interactions. Hydrophobic interactions favored protein–protein interactions and decreased the solubility, whereas the ionic interactions promoted protein-water interactions, thus improving solubility of protein [35]. The balance between these interactions was directly influenced by the operating conditions of ultrasound treatment. Zou et al. [36] also observed the decreased solubility of chicken protein when ultrasound power was increased from 100 to 150 W to 200 W. Therefore, the solubility of FMP was governed by the condition used for ultrasound treatment.

Fig. 2.

Solubility (A) and surface hydrophobicity (B), emulsion activity index (C) and emulsion stability index (D) of fish myofibrillar protein and those subjected to ultrasonication with different conditions. C: untreated-FMP (control). Numbers represent amplitude (%) and operation time (min), respectively. Different lowercase letters on the bar denotes significant difference (p < 0.05). Bars represents the standard deviations (n = 3).

3.1.3. Surface hydrophobicity

Surface hydrophobicity of FMP and UFMP prepared at varying amplitudes and durations of ultrasound treatment are given in Fig. 2B. Surface hydrophobicity directly influences the conformation and functional properties of proteins [23]. Ultrasound treatment significantly increased the surface hydrophobicity of FMP (p < 0.05). Overall, the highest increase (44%) in surface hydrophobicity was attained in UFMP prepared at 40% amplitude for 15 min as compared to the control (p < 0.05). The increased surface hydrophobicity was more likely due to the unfolding of FMP, leading to the exposure of buried hydrophobic residues. These favored the binding of proteins to the surface of oil droplets during emulsification, resulting in the improved alignment or aggregation of proteins to form thick and strong film surrounding the oil droplets. Similarly, Zhou et al. [37] reported that surface hydrophobicity increased remarkably in ultrasound-treated pork myofibrillar protein at 37% amplitude for 6 min, compared to the untreated control sample. On the other hand, when 60% amplitude was applied, surface hydrophobicity of FMP increased up to 10 min of treatment (p < 0.05). However, UFMP treated with 60% amplitude for 15 min showed a decrease in surface hydrophobicity (p < 0.05). This might be due to protein aggregation via hydrophobic interactions. More exposed hydrophobic residues subsequently undergo protein–protein interactions via hydrophobic interaction, leading to aggregation [38]. Generally, the formation of protein aggregates led to large particle sizes and potentially reduced solubility [9]. This result coincided with decreased solubility of UFMP at 60% amplitude for 15 min (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the exposed hydrophobic groups and re-aggregation via hydrophobic interaction of FMP was governed by ultrasound condition.

3.1.4. Emulsifying properties

EAI and ESI of SO-in-water emulsions stabilized by FMP and UFMP treated under different operating conditions of ultrasound treatment are given in Fig. 2C and D. EAI estimates the amount of interfacial area that can be stabilized per unit weight of protein (Fig. 2C) [19]. ESI refers to the ability of protein in maintaining small oil droplets in the emulsion (Fig. 2D) [39]. In general, UFMP had enhanced emulsifying properties than untreated FMP (p < 0.05). This was plausibly due to higher solubility and partial unfolding of UFMP. Consequently, there were higher interactions between flexible protein and oil droplets along with enhanced protein rearrangements at the oil–water interface. Overall, EAI and ESI were noticed to be higher in emulsion stabilized by UFMP (40% amplitude for 15 min) (p < 0.05). The higher emulsifying properties were consistent with greater solubility and surface hydrophobicity of UFMP (40% amplitude for 15 min) (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, flexibility of protein facilitated the formation of a thick interfacial film as a result of improved protein distribution, thus enhancing the emulsion stability. In addition, higher surface hydrophobicity of UFMP promoted the interactions of the protein with oil droplets via hydrophobic interactions. The compact interfacial layer was formed surrounding the oil droplets, leading to increased emulsion stability [40]. On the other hand, FMP subjected to ultrasound at 60% amplitude for 15 min had slight decrease in emulsifying properties, compared to UFMP (60% amplitude for 10 min). The result suggested that protein aggregation probably occurred, thus lowering the exposed hydrophobic domain. This could reduce the protein interaction with oil droplets. Moreover, protein aggregation might lower molecular flexibility and increase the protein size, resulting in lowered diffusion of protein from the aqueous phase to the interface [7]. Hence, the emulsifying properties of FMP depended on the operating conditions of ultrasound. Based on the above-mentioned results, the optimum conditions of ultrasound for FMP treatment were found at 40% amplitude for 15 min, which were selected for further study.

3.2. Interfacial properties of SO-in-water emulsion and FTIR spectra of FMP and the selected ultrasound-treated FMP

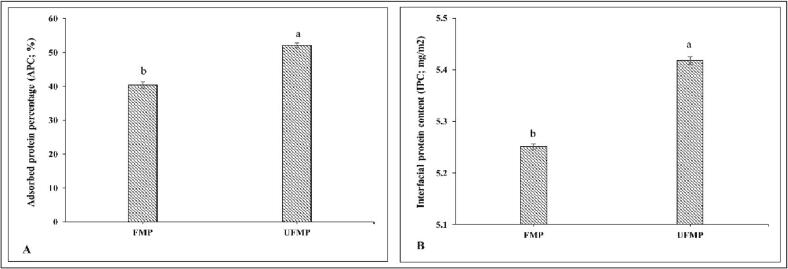

3.2.1. Adsorbed protein content (APC) and interfacial protein content (IPC)

APC and IPC of emulsion stabilized by FMP and UFMP (40% amplitude for 5 min) are depicted in Fig. 3A,B. The ability of the protein to reduce interfacial tension was closely related to APC and IPC [41]. Overall, the emulsion stabilized by UFMP had higher contents of both APC and IPC (p < 0.05), compared to that stabilized by FMP. Higher APC of UFMP stabilized emulsion was attributed to improved flexibility and surface hydrophobicity and reduced size of FMP by the cavitation effect of ultrasound. Moreover, higher adsorbed protein resulted in the formation of multilayered and densely packed interfacial film covering the oil droplets [42]. Rajasekaran et al. [24] postulated that the smaller size of the protein facilitated the enhanced diffusion from the aqueous phase to the interface during emulsification. Higher APC indicated that more proteins were adsorbed per unit interfacial area of the emulsion, leading to increased IPC (p < 0.05). This behavior was presumably due to the generation of the larger interfacial area associated with small oil droplets formed during emulsification. Additionally, higher IPC probably increased the thickness of the interfacial layer in UFMP stabilized emulsion. As a consequence, steric repulsion between oil droplets was augmented, thereby providing improved stability for emulsion stabilized by UFMP (Fig. 2D). Similarly, Soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by ultrasound-treated chicken myofibrillar protein (60% amplitude) and cod protein (200, 400, 600, 800, and 950 W) had higher protein adsorption at the interface than those stabilized by untreated protein [7], [8].

Fig. 3.

Adsorbed protein content (A) and interfacial protein content (B) in shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP treated with ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP). Different lowercase letters within the same parameter tested denoted significant difference (p < 0.05). Bars represents the standard deviation (n = 3).

3.2.2. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra

The effect of ultrasonication on the secondary structure of FMP was examined using FTIR (Fig. 4A). Overall, FTIR spectra had a broad and strong absorption band at 3275–3260 cm−1, 2915–2908 cm−1 and 2354–2369 cm−1, corresponding to the O-H stretching, C-H stretching, and O = C = O stretching vibration, respectively [43]. The changes in the peak position of amide I and amide II are commonly used to analyze the transformation of protein structure [15]. Spectra range between 1700 and 1600 cm−1 is assigned with the amide I band, representing the C = O stretching vibrations of protein linkages and is often used to monitor the changes in protein secondary structures than the amide II region (1480–1575 cm−1) [44]. Amide II band corresponds to C-N stretching vibration in combination with N-H bending. Amide I peak shifted from 1686 cm−1 (FMP) to 1689 cm−1 (UFMP). The shift to higher wavenumber suggested that some β-sheet turned into α-helix or random coil [45]. With respect to amide II, peak positions shifted from 1514 cm−1 (FMP) to 1512 cm−1 (UFMP) and from 1541 cm−1 (FMP) to 1539 cm−1 (UFMP) after ultrasound treatment. The shift to the lower wavenumber suggested the conversion of a portion of the random coil into β-sheet [46]. The peak at wavenumber of 1576 cm−1 (FMP) increased to 1585 cm−1 (UFMP). The increase in wavenumber was attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between protein molecules when subjected to ultrasonication [47]. Therefore, changes in the position of the amide I and II regions of FMP indicated the alterations in its secondary structure.

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra (A) and secondary structure analysis in amide I region (B) of fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP treated with ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP).

The quantification of secondary structure changes was performed through curve fitting of the deconvoluted FTIR spectra of the amide I band as shown in Fig. 4B. Notably, no α-helix was detected in both FMP and UFMP. This reflected that the repulsion of protein at acidic pH led to the complete loss of α-helix structure, especially in the tail of MHC. When compared with FMP, the β-sheet composition of UFMP decreased slightly from 41.75% to 41.54% due to the denaturation of FMP caused by ultrasound. Similarly, Hu et al. [48] also postulated that ultrasonication (600 W for 30 min) decreased the β-sheet in soy protein isolate. Moreover, the random coil of UFMP decreased from 18.42% to 17.69% after ultrasound treatment. This decrease was associated with partial unfolding and conformational changes of protein induced by ultrasonication, thereby facilitating the exposure of hydrophobic residues. Also, Gülseren et al. [49] found a reduction in random coil of BSA as induced by ultrasound treatment at 450 W for 90 min. However, no difference was found in β-turn between FMP (29.33%) and UFMP (29.34%) samples. Hence, ultrasonication induced the changes in secondary structure of FMP. Overall, these structural changes favored the flexibility of FMP, thereby enhancing its emulsifying properties.

3.3. Changes in physical properties and stability of SO-in-water emulsion stabilized by FMP and the selected ultrasound-treated FMP at days 0 and 30 of storage

3.3.1. Turbidity

Overall, both emulsions exhibited the decrease in turbidity at day 30 (p < 0.05). Compared with emulsion stabilized by FMP, UFMP stabilized emulsion possessed higher turbidity at day 0 and day 30 (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Higher turbidity denotes a more stable emulsion, suggesting more adsorbed protein at the interface and smaller oil droplet size, which was related to less coalescence. Moreover, ultrasound treatment could induce partial unfolding of FMP molecules, thus exposing the hydrophobic domain. This favored the adsorption of proteins over the oil droplets in the UFMP stabilized emulsion. In general, more protein adsorption at the interface enhances electrostatic repulsion between the droplets, thus providing more stable emulsion. The result was in line with the higher ESI of UFMP stabilized emulsion (Fig. 2D). Typically, when turbidity drops to half of its initial value, the emulsion becomes unstable [27]. On day 30 of storage, turbidity decreased by 41.4% and 38.1% of the initial value (day 0) for the FMP and UFMP stabilized emulsions, respectively. During storage, emulsion underwent physical changes such as coalescence and flocculation. Coalescence refers to the merging of oil droplets, while flocculation refers to the aggregation of oil droplets [17]. These processes led to a reduction in the number of dispersed oil droplets, leading to increased oil droplet size. As a result, light scattering of the emulsion decreased, thereby resulting in lower turbidity [50]. Nevertheless, no apparent phase separation was observed in both emulsions throughout the storage. Taha et al. [51] documented that ultrasound treatment at 40% amplitude for 2–18 min improved stability of soy protein isolate stabilized emulsion using different oils (palm, soybean, and rapeseed oils). Therefore, ultrasound treatment of FMP could enhance emulsion stability during prolonged storage.

Table 1.

Turbidity, droplet size, polydispersity index (PDI), flocculation (Fi), and coalescence index (Ci) of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP subjected to ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP) at day 0 and 30 of storage at 30 °C.

| Storage time (day) | Samples | Turbidity (NTU) | d32 (µm) | d43 (µm) | PDI | Fi | Ci |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | FMP | 128.09 ± 0.64Ba | 1.30 ± 0.05Ab | 1.44 ± 0.03Ab | 0.28 ± 0.01Ab | 2.36 ± 0.02Ab | ND |

| UFMP | 134.08 ± 0.38Aa | 1.04 ± 0.02Bb | 1.16 ± 0.07Bb | 0.22 ± 0.03Bb | 2.18 ± 0.03Bb | ND | |

| 30 | FMP | 75.34 ± 1.32Bb | 2.19 ± 0.03Aa | 2.31 ± 0.01Aa | 0.34 ± 0.02Aa | 2.65 ± 0.00Aa | 59.85 ± 2.36A |

| UFMP | 83.87 ± 1.62Ab | 1.63 ± 0.02Ba | 1.72 ± 0.04Ba | 0.28 ± 0.00Ba | 2.41 ± 0.03Ba | 48.56 ± 1.89B | |

Mean ± SD (n = 3). Different uppercase superscripts in the same column within the same storage time indicates significant differences (p < 0.05). Different lowercase superscripts in the same column within the same sample indicates significant differences (p < 0.05). FMP and UFMP: emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP subjected to ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min), respectively. ND: Not detected.

3.3.2. Droplet size

Droplet diameter (d43), an indicator of flocculation and coalescence, represents the association of individual droplets into larger flocs [52]. A low value of d32 indicates a higher amount of protein adsorbed at the interface [28]. Emulsion stabilized by UFMP generally had lower d32 and d43 compared to untreated FMP stabilized emulsion throughout the storage (p < 0.05) (Table 1). This was likely attributed to the reduction in the size of FMP molecules caused by the disruption of structural integrity, protein dissociation and degradation induced by the cavitation effect of ultrasound. Also, shear force of ultrasound was accompanied by microstreaming and turbulence. Zhang et al. [11] observed the reduction in size of chicken breast myofibrillar protein when treated with ultrasound at 200 W for 15 min. Tcholakova et al. [53] demonstrated a significant correlation between smaller droplet size and higher adsorbed protein in emulsion stabilized by β-lactoglobulin. The result was in line with higher APC (Fig. 3A) and greater stability (Table 1) of emulsion stabilized by UFMP. At day 0, the emulsions had lower d32 and d43, irrespective of ultrasound treatment than those stored for 30 days (p < 0.05). Droplet aggregation was indicated by the increase in droplet size, which ultimately resulted in coalescence. Overall, the increase in the size of droplets was more pronounced in emulsion stabilized by FMP than that found in the UFMP-stabilized emulsion.

Lower and higher PDI typically denote the homogeneity and heterogenicity of emulsion, respectively [54]. Overall, PDI was lower in emulsions stabilized by UFMP than those stabilized by FMP counterpart (p < 0.05) as shown in Table 1. After 30 days of storage, the PDI increased in both emulsions. The result showed that the oil droplets became more heterogeneous. Merging of oil droplets via coalescence occurred during storage. The result was consistent with Liu et al. [42], who demonstrated that PDI decreased in soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by ultrasound treated-pork myofibrillar protein (120–600 W) compared to emulsion stabilized by untreated protein. Therefore, UFMP had the potential to produce SO-in-water emulsions with smaller droplet sizes and lower PDI, which favored emulsion stability.

3.3.3. Flocculation and coalescence index

In general, the attraction between oil droplets in emulsion led to droplet flocculation. Lower Fi indicates higher steric repulsion compared to attractive force between oil droplets [55]. Overall, the emulsion stabilized by UFMP had lower Fi compared to that stabilized by FMP (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Protein size, flexibility, and surface hydrophobicity generally determine the potential of protein molecule to adsorb at the oil–water interface. Smaller FMP molecules resulting from ultrasound treatment could diffuse more rapidly and re-aligned over the oil droplets to lower interfacial tension. Additionally, higher surface hydrophobicity of UFMP encouraged more protein to adhere on droplets’ surface during emulsification. This led to the formation of multilayer and thicker film at the interface, thus preventing flocculation during storage. Ci denotes the flocculation-induced droplet collapse, particularly via the formation of larger droplets [29]. UFMP stabilized emulsion had lower Ci, which was associated with high protein adsorption at the interface (p < 0.05). More protein coverage rate of UFMP resulted in greater repulsion between oil droplets, which prevented oil droplet coalescence. Wang et al. [56] stated that viscoelastic characteristics and thickness of the interfacial film determined the prevention of coalescence. The result was in line with the increased APC and IPC in UFMP stabilized emulsion (Fig. 3A,B). At the end of storage, UFMP stabilized emulsion had lower Fi and Ci, indicating higher emulsion stability. Hence, the stability of emulsion was improved when oil droplets were surrounded by interfacial UFMP film.

3.3.4. Microstructure

Microstructure of the emulsion stabilized by FMP and UFMP was visualized using optical microscopy as given in Fig. 5. On day 0 and 30, the emulsion stabilized by UFMP had smaller oil droplets. On the other hand, larger droplets were observed in untreated FMP stabilized emulsion. The microstructure results reconfirmed that lesser oil droplets underwent flocculation or coalescence when UFMP was used to stabilize emulsion. Therefore, UFMP effectively inhibited the coalescence and maintained the small size of droplets throughout the storage as seen in Table 1. On day 0, the emulsion stabilized by FMP and UFMP had smaller droplet size compared to those observed on day 30, irrespective of ultrasound treatment. This suggested that the coalescence more likely occurred during prolonged storage. Xiong et al. [10] postulated that soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by ultrasound-treated threadfin bream protein and xanthan gum (150–600 W) had smaller droplet than those stabilized by untreated protein-polysaccharide counterpart. Hence, the ultrasound treatment of FMP prevented the increase in droplet size of emulsion during storage.

Fig. 5.

Microstructure of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP treated with ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP) at day 0 and 30 of storage at 30 °C. Magnification: 40x.

3.3.5. CLSM images

When UFMP was used as an emulsifier, a monodisperse emulsion with uniform droplet distribution, was obtained (Fig. 6). On the other hand, untreated FMP yielded polydisperse emulsion with larger droplet size and non-uniform dispersion. The result was consistent with droplet size, PDI (Table 1), and microstructure observations (Fig. 4). On day 30, several flocculated oil droplets were detected in emulsion stabilized by untreated FMP. However, small and uniformly dispersed oil droplets were still observed in UFMP stabilized emulsion at the end of storage. In general, myosin tends to undergo self-aggregation to form ordered myofilament structure via electrostatic attraction [42]. However, the partially unfolded UFMP formed a viscoelastic layer at the interface. This provided strong and thick interfacial layer that sustained the stability of dispersed oil droplets. Moreover, unfolded protein was able to surround the dispersed oil droplets to the higher extent, thereby enhancing emulsion stability [56].

Fig. 6.

Confocal laser scanning microscopic images of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP treated with ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP) at day 0 and 30 of storage at 30 °C. Magnification: 400x.

3.3.6. Rheological properties

Viscoelastic properties are crucial for the formulation of several food products including food emulsion. Overall, the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G″ ) of the emulsion upsurged with frequency as shown in Fig. 7A,B. G' and G″ have been considered as potential indicators of interfacial film thickness and the surface load of emulsifier, which influence emulsion stability [24]. Typically, G' denotes the magnitude of energy retained in emulsion, whereas G″ depicts the energy loss associated with viscous dissipation [57]. G″ was higher than G', indicating that the emulsion exhibited viscous behavior dominantly than elastic behavior. UFMP stabilized emulsion possessed higher G' and G″ than the untreated FMP stabilized emulsion. Higher modulus values (G' and G″ ) of emulsion were more likely associated with the formation of thicker films surrounding oil droplets through hydrophobic interactions [58]. G' and G″ of both emulsions were higher on day 0 compared to day 30. This might be because of strong interaction between proteins surrounding the oil droplets at day 0 as witnessed by high viscosity. As a result, more stress was required for the emulsions to flow. Nevertheless, at day 30, G' and G″ were reduced in both the emulsions, indicating weaker interactions of proteins located on the surface of oil droplets during prolonged storage.

Fig. 7.

Storage modulus, G' (A) and loss modulus, G″ (B) and viscosity (C) of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein (FMP) and FMP treated with ultrasound (40% amplitude for 15 min; UFMP) at day 0 and 30 of storage at 30 °C.

Viscosity of the emulsion stabilized by FMP and UFMP at days 0 and 30 is depicted in Fig. 7C. Viscosity has been used as a metric to evaluate the emulsion stability. Application of shear stress resulted in the separation of oil droplets from one another in the emulsified phase, leading to rearrangement of the droplet distribution in emulsion. Overall, the viscosity decreased with increasing shear rate. The result revealed that emulsions had shear thinning and pseudoplastic behavior, a typical characteristic of non-Newtonian fluids [42]. Moreover, shear-thinning behavior is a typical feature of many food emulsions including spreads, sauces, mayonnaise, etc. [59]. Viscosity was higher in emulsion stabilized by UFMP, whereas untreated FMP stabilized emulsion had lower viscosity. According to Stoke’s law, the viscosity of the emulsion is inversely related to the size of oil droplets [8]. This result was in line with the smaller droplet size of UFMP stabilized emulsion (Table 1 and Fig. 7C). Feng et al. [60] documented that greater stability was indicated by higher viscosity of emulsion via lowering droplets sedimentation or creaming. Both emulsions had higher viscosity at day 0 compared to day 30. This was related with the increased droplet size and decreased number of droplets per unit volume observed at day 30 (Table. 1). At day 30, viscosity decreased, indicating less flow resistance or increased mobility. Hence, ultrasound treatment of FMP could improve the rheological characteristics of FMP-based SO-in-water emulsion.

4. Conclusion

Ultrasonication at 40% amplitude for 15 min significantly improved solubility, surface hydrophobicity and emulsifying properties of fish myofibrillar protein (FMP). The reduction in molecular weight and changes in chemical bonds of FMP led to the improved emulsion properties. Emulsion stabilized by ultrasound-treated FMP (UFMP) had higher adsorbed and interfacial protein content. During storage of 30 days, UFMP stabilized emulsion had higher stability, smaller droplet size and lower flocculation and coalescence indices than that stabilized by untreated FMP. Higher modulus values (G' and G″ ) and the presence of monodisperse droplets were also found in the former. Overall, ultrasound treatment enhanced the emulsifying properties of FMP and improved the storage stability of shrimp oil (SO)-in-water emulsion during extended storage.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bharathipriya Rajasekaran: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Avtar Singh: Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Arunachalasivamani Ponnusamy: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Umesh Patil: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Bin Zhang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Hui Hong: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Soottawat Benjakul: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRIF) and Prince of Songkla University (PSU) (Grant No: AGR6505155M). PSU president scholarship for Bharathipriya Rajasekaran, Prachayacharn grant from PSU (Grant No: AGR6502111N) and chair professor grant (Grant No: P-20-52297) are gratefully acknowledged.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.Jamshidi A., Shabanpour B., Pourashouri P., Raeisi M. Using WPC-inulin-fucoidan complexes for encapsulation of fish protein hydrolysate and fish oil in W1/O/W2 emulsion: characterization and nutritional quality. Food Res. Int. 2018;114:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulzar S., Benjakul S., Hozzein W.N. Impact of β-glucan on debittering, bioaccessibility and storage stability of skim milk fortified with shrimp oil nanoliposomes. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;55:2092–2103. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagarajan M., Rajasekaran B., Benjakul S., Venkatachalam K. Influence of chitosan-gelatin edible coating incorporated with longkong pericarp extract on refrigerated black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021;4:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raju N., Benjakul S. Use of beta cyclodextrin to remove cholesterol and increase astaxanthin content in shrimp oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020;122:1900242. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201900242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulzar S., Benjakul S. Characteristics and storage stability of nanoliposomes loaded with shrimp oil as affected by ultrasonication and microfluidization. Food Chem. 2020;310 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiménez-Colmenero F. Potential applications of multiple emulsions in the development of healthy and functional foods. Food Res. Int. 2013;52:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma W., Wang J., Xu X., Qin L., Wu C., Du M. Ultrasound treatment improved the physicochemical characteristics of cod protein and enhanced the stability of oil-in-water emulsion. Food Res. Int. 2019;121:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li K., Fu L., Zhao Y.-Y., Xue S.-W., Wang P., Xu X.-L., Bai Y.-H. Use of high-intensity ultrasound to improve emulsifying properties of chicken myofibrillar protein and enhance the rheological properties and stability of the emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;98 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amiri A., Sharifian P., Soltanizadeh N. Application of ultrasound treatment for improving the physicochemical, functional and rheological properties of myofibrillar proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;111:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong Y., Li Q., Miao S., Zhang Y., Zheng B., Zhang L. Effect of ultrasound on physicochemical properties of emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein and xanthan gum. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019;54:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z., Regenstein J.M., Zhou P., Yang Y. Effects of high intensity ultrasound modification on physicochemical property and water in myofibrillar protein gel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jambrak A.R., Mason T.J., Lelas V., Paniwnyk L., Herceg Z. Effect of ultrasound treatment on particle size and molecular weight of whey proteins. J. Food Eng. 2014;121:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taha A., Ahmed E., Ismaiel A., Ashokkumar M., Xu X., Pan S., Hu H. Ultrasonic emulsification: an overview on the preparation of different emulsifiers-stabilized emulsions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;105:363–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koshani R., Jafari S.M. Ultrasound-assisted preparation of different nanocarriers loaded with food bioactive ingredients. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;270:123–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L., Cai R., Wang P., Xu X., Zhou G., Sun J. Manipulating interfacial behavior and emulsifying properties of myosin through alkali-heat treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;85:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.06.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chanarat S., Benjakul S., H-Kittikun A. Comparative study on protein cross-linking and gel enhancing effect of microbial transglutaminase on surimi from different fish. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;92:844–852. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajasekaran B., Singh A., Zhang B., Hong H., Benjakul S. Changes in emulsifying and physical properties of shrimp oil/soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein during the storage. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2022;124:2200068. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.202200068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson H.W., Hogden C.G. The biuret reaction in the determination of serum proteins. 1. a study of the conditions necessary for the production of a stable color which bears a quantitative relationship to the protein concentration. J. Biol. Chem. 1940;135:707–725. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiansilakul Y., Benjakul S., Shahidi F. Compositions, functional properties and antioxidative activity of protein hydrolysates prepared from round scad (Decapterus maruadsi) Food Chem. 2007;103:1385–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajasekaran B., Singh A., Nagarajan M., Benjakul S. Effect of chitooligosaccharide and α-tocopherol on physical properties and oxidative stability of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by bovine serum albumin-chitosan complex. Food Control. 2022;137 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sha L., Koosis A.O., Wang Q., True A.D., Xiong Y.L. Interfacial dilatational and emulsifying properties of ultrasound-treated pea protein. Food Chem. 2021;350 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh A., Benjakul S., Kijroongrojana K. Effect of ultrasonication on physicochemical and foaming properties of squid ovary powder. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;77:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajasekaran B., Singh A., Benjakul S. Combined effect of chitosan and bovine serum albumin/whey protein isolate on the characteristics and stability of shrimp oil-in-water emulsion. J. Food Sci. 2022;87:2879–2893. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang H.-N., C.-h. Tang, pH-dependent emulsifying properties of pea [Pisum sativum (L.)] proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;33:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsuwan K., Benjakul S., Prodpran T. Properties and antioxidative activity of fish gelatin-based film incorporated with epigallocatechin gallate. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;80:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X., Xia W. Effects of concentration, degree of deacetylation and molecular weight on emulsifying properties of chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011;48:768–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sae-leaw T., Benjakul S., O'Brien N.M., Kishimura H. Characteristics and functional properties of gelatin from seabass skin as influenced by defatting. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;51:1204–1211. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patil U., Benjakul S. Physical and textural properties of mayonnaise prepared using virgin coconut oil/fish oil blend. Food Biophys. 2019;14:260–268. doi: 10.1007/s11483-019-09579-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil U., Benjakul S. Characteristics of albumin and globulin from coconut meat and their role in emulsion stability without and with proteolysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;69:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng X., Ma Y., Lei Y., Zhu X., Zhang L., Hu L., Lu S., Guo X., Zhang J. Ultrasonic structural modification of myofibrillar proteins from Coregonus peled improves emulsification properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saleem R., Ahmad R. Effect of low frequency ultrasonication on biochemical and structural properties of chicken actomyosin. Food Chem. 2016;205:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arzeni C., Martínez K., Zema P., Arias A., Pérez O., Pilosof A. Comparative study of high intensity ultrasound effects on food proteins functionality. J. Food Eng. 2012;108:463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan S., Xu J., Zhang S., Li Y. Effects of flexibility and surface hydrophobicity on emulsifying properties: ultrasound-treated soybean protein isolate. Lwt. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wouters A.G., Rombouts I., Fierens E., Brijs K., Delcour J.A. Relevance of the functional properties of enzymatic plant protein hydrolysates in food systems. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016;15:786–800. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou Y., Xu P., Wu H., Zhang M., Sun Z., Sun C., Wang D., Cao J., Xu W. Effects of different ultrasound power on physicochemical property and functional performance of chicken actomyosin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;113:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou L., Zhang J., Lorenzo J.M., Zhang W. Effects of ultrasound emulsification on the properties of pork myofibrillar protein-fat mixed gel. Food Chem. 2021;345 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjakul S., Oungbho K., Visessanguan W., Thiansilakul Y., Roytrakul S. Characteristics of gelatin from the skins of bigeye snapper, Priacanthus tayenus and Priacanthus macracanthus. Food Chem. 2009;116:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'sullivan J., Murray B., Flynn C., Norton I. The effect of ultrasound treatment on the structural, physical and emulsifying properties of animal and vegetable proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;53:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sui X., Bi S., Qi B., Wang Z., Zhang M., Li Y., Jiang L. Impact of ultrasonic treatment on an emulsion system stabilized with soybean protein isolate and lecithin: its emulsifying property and emulsion stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;63:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng W., Kong X., Chen Y., Zhang C., Yang Y., Hua Y. Effects of heat treatment on the emulsifying properties of pea proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;52:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu C., Fan L., Yang Y., Jiang Q., Xu Y., Xia W. Characterization of surimi particles stabilized novel pickering emulsions: effect of particles concentration, pH and NaCl levels. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;117 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh A., Benjakul S., Prodpran T., Nuthong P. Effect of psyllium (Plantago ovata Forks) husk on characteristics, rheological and textural properties of threadfin bream surimi gel. Foods. 2021;10:1181. doi: 10.3390/foods10061181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zandomeneghi G., Krebs M.R., McCammon M.G., Fändrich M. FTIR reveals structural differences between native β-sheet proteins and amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 2004;13:3314–3321. doi: 10.1110/ps.041024904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S., Yang X., Zhang Y., Ma H., Qu W., Ye X., Muatasim R., Oladejo A.O. Enzymolysis kinetics and structural characteristics of rice protein with energy-gathered ultrasound and ultrasound assisted alkali pretreatments. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;31:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong J., Yu S. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic analysis of protein secondary structures. Acta Biochim. Biophy. Sin. 2007;39:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yong Y.H., Yamaguchi S., Matsumura Y. Effects of enzymatic deamidation by protein-glutaminase on structure and functional properties of wheat gluten. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:6034–6040. doi: 10.1021/jf060344u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu H., Li-Chan E.C., Wan L., Tian M., Pan S. The effect of high intensity ultrasonic pre-treatment on the properties of soybean protein isolate gel induced by calcium sulfate. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;32:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gülseren İ., Güzey D., Bruce B.D., Weiss J. Structural and functional changes in ultrasonicated bovine serum albumin solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirhosseini H., Tan C.P., Aghlara A., Hamid N.S., Yusof S., Chern B.H. Influence of pectin and CMC on physical stability, turbidity loss rate, cloudiness and flavor release of orange beverage emulsion during storage. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008;73:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taha A., Hu T., Zhang Z., Bakry A.M., Khalifa I., Pan S., Hu H. Effect of different oils and ultrasound emulsification conditions on the physicochemical properties of emulsions stabilized by soy protein isolate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;49:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McClements D.J. CRC Press; 2004. Food emulsions: principles, practices, and techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tcholakova S., Denkov N.D., Ivanov I.B., Campbell B. Coalescence in β-lactoglobulin-stabilized emulsions: effects of protein adsorption and drop size. Langmuir. 2002;18:8960–8971. doi: 10.1021/la0258188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tagrida M., Benjakul S., Zhang B. Use of betel leaf (Piper betle L.) ethanolic extract in combination with modified atmospheric packaging and nonthermal plasma for shelf-life extension of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fillets. J. Food Sci. 2021;86:5226–5239. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ettoumi Y.L., Chibane M., Romero A. Emulsifying properties of legume proteins at acidic conditions: Effect of protein concentration and ionic strength, LWT-Food. Sci. Technol. 2016;66:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.10.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J.-Y., Yang Y.-L., Tang X.-Z., Ni W.-X., Zhou L. Effects of pulsed ultrasound on rheological and structural properties of chicken myofibrillar protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei Y., Xie Y., Cai Z., Guo Y., Zhang H. Interfacial rheology, emulsifying property and emulsion stability of glyceryl monooleate-modified corn fiber gum. Food Chem. 2021;343 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu M., Xiong Y.L., Chen J. Role of disulphide linkages between protein-coated lipid droplets and the protein matrix in the rheological properties of porcine myofibrillar protein–peanut oil emulsion composite gels. Meat Sci. 2011;88:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wijayanti I., Benjakul S., Chantakun K., Prodpran T., Sookchoo P. Effect of Asian sea bass bio-calcium on textural, rheological, sensorial properties and nutritive value of Indian mackerel fish spread at different levels of potato starch. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022;57:3181–3195. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.15651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng X., Dai H., Ma L., Fu Y., Yu Y., Zhou H., Guo T., Zhu H., Wang H., Zhang Y. Properties of Pickering emulsion stabilized by food-grade gelatin nanoparticles: Influence of the nanoparticles concentration. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2020;196 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.