Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of simvastatin 80 mg/day versus placebo in patients with noninfectious nonanterior uveitis receiving prednisolone ≥ 10 mg/day.

Design

Randomized, double-masked, controlled trial.

Subjects

Adult patients with noninfectious nonanterior uveitis on oral prednisolone dose of ≥ 10 mg/day.

Methods

Patients were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to receive either simvastatin 80 mg/day or placebo. A total of 32 patients were enrolled (16 in each arm), all of whom completed the primary end point, and 21 reached the 2-year visit (secondary end points).

Main Outcome Measures

The primary end point was mean reduction in the daily prednisolone dose at 12 months follow-up. Secondary end points were mean reduction in prednisolone dose at 24 months, percent of patients with a reduction in second-line immunomodulatory agents, time to disease relapse, and adverse events.

Results

Our results show that simvastatin 80 mg/day did not have a significant corticosteroid-sparing effect at 12 months (estimate: 3.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −8.15 to 15.38; P = 0.54). There was no significant difference between the groups with regard to prednisolone dose or change in dose at 12 and 24 months. There was no difference between the 2 groups in percent of patients with reduction in second-line agent by 24 months. Among patients who achieved disease quiescence, the median time to first relapse was longer for those receiving simvastatin (38 weeks, 95% CI: 14–54) than placebo (14 weeks, 95% CI: 12–52), although this was not statistically significant. There was no significant difference in adverse events or serious adverse events between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

Simvastatin 80 mg/day did not have an effect on the dose reduction of corticosteroids or conventional immunomodulatory drugs at 1 and 2 years. The results suggest that it may extend the time to disease relapse among those who achieve disease quiescence.

Financial Disclosure(s)

The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, Immunomodulatory drugs, Prednisolone, Noninfectious uveitis, Simvastatin

Systemic corticosteroids represent the mainstay treatment for patients with uveitis, particularly those with systemic involvement or bilateral disease. Although treatment is very effective in controlling the intraocular inflammation, long-term systemic side effects limit their use, so ophthalmologists continually aim to reduce the dose to ≤ 10 mg/day.1 To achieve this, other immunomodulatory agents can be added to enhance and maintain inflammatory control. Although they are effective in the majority of cases,2, 3, 4, 5 they are not without their own risks of complications and can affect hepatic, renal, and gastrointestinal function, as well as increase the risk of opportunistic infections.

Statins are routinely prescribed to reduce serum cholesterol levels and improve clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). They are considered an effective treatment with a low risk of systemic side effects, primarily myalgia, and rhabdomyolysis. Studies have shown that they also have pleiotropic immunomodulatory effects, both in vitro and in vivo.6 In animal models of uveoretinitis, statins reduced the clinical and histologic scores of inflammation and inhibited T lymphocyte recruitment into the retina.7 Two large observational population-based studies also showed a protective effect of statins against the development of uveitis.8,9 Clinical studies in patients with multiple sclerosis showed a positive effect from simvastatin on brain atrophy, suggesting that these drugs cross the blood–brain barrier and can play a role in controlling disease activity.10 In rheumatoid arthritis, statins led to improvement in disease activity scores and reduced the numbers of tender and swollen joints.11 A study on the effect of statins among patients with sarcoidosis demonstrated an increased time to disease flare among patients with mild–moderate disease.12 Given the relatively safe side effect profile of statins, they would be a suitable treatment option for patients with uveitis, as well as reducing serum cholesterol levels and improving the cardiovascular outcomes in patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy.

The aim of this study was to prospectively examine in a randomized double-masked clinical trial the additional anti-inflammatory effect and safety of simvastatin in patients with uveitis and to determine if their addition could reduce the amount of corticosteroid or number/dose of additional immunomodulatory agents required to keep the uveitis controlled.

Methods

This study was a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical trial in patients with intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis who required systemic prednisolone at ≥ 10 mg/day to control their intraocular inflammation with or without the addition of a second-line immunomodulatory agent. The study was conducted at Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, United Kingdom, and subjects were selected from patients treated in the uveitis service. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (REC reference: 15/LO/0084) and adhered to the Tenants of the Declaration of Helsinki (protocol number: 14/0172; EudraCT number: 2014-003119-13; IRAS project ID: 156966). All participating patients were included after providing written informed consent. Patients were included if they were between the ages of 18 and 80 years; were diagnosed with noninfectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis; and were treated with a dose of prednisolone > 10 mg/day with or without a second-line immunosuppression agent. Patients of both genders were included, although premenopausal female patients were required to use 2 methods of contraception. For exclusion criteria see Table S1 (available at www.ophthalmologyscience.org).

The study was designed to compare the effect of simvastatin 80 mg once daily versus placebo on prednisolone dose at 12-month follow-up. The primary outcome measure was the change in prednisolone dose at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included mean change in prednisolone dose at 24 months; change in percent of patients requiring second-line immunosuppression at 24 months; rate of disease relapses at 24 months; blood cholesterol and lipid levels at 24 months; and safety of simvastatin.

Patients were assigned randomly using a blocked randomization method to ensure balanced sample sizes. Patients were randomly allocated using an online system to receive either simvastatin or placebo (1:1). A total of 32 patients (16 in each arm) were randomized (Fig S1, available at www.ophthalmologyscience.org). For all patients, prednisolone and second-line immunosuppression doses were decided based on clinical findings and disease activity at each study visit. When inflammation was found to be inactive, prednisolone dose was reduced using a weekly reduction regimen down to < 10 mg/day. Prednisolone reduction regimen followed accepted clinical practices, for doses between 60 and 30 mg/day a weekly reduction of 10 mg, between 30 and 15 mg/day a weekly reduction of 5 mg, and < 15 mg/day a weekly reduction of 2.5 mg.13 Once a prednisolone dose of < 10 mg/day was achieved, second-line immunosuppression was reduced in monthly decrements until stopped. All patients were followed up in the trial every 3 months for 12 months, although seen routinely as required, and 21 completed 24 months of follow-up.

At each study visit, patients had their vital signs checked, full ophthalmic assessment, including visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and slit-lamp examination with dilated biomicroscopic fundal examination. The level of inflammatory activity was assessed against the standardization of uveitis nomenclature (SUN) criteria,14 and a macular OCT scan (Heidelberg Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering Inc) was performed. Blood tests were taken, including full blood count, serum lipids, creatinine kinase enzyme, liver and kidney function tests, and pregnancy tests for women of childbearing potential. At each trial visit, a review of concomitant medications and compliance with trial drug administration was done, as well as recording any adverse reactions. Disease quiescence was defined as a follow-up visit in which no intraocular inflammation was noted. Disease relapse was defined as a subsequent recurrence of intraocular inflammation requiring any increase or addition of immunosuppression treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size of 32 patients (16 per arm) was calculated to detect a difference of 2.5 mg between arms in terms of the primary outcome, prednisolone reduction after 12 months, assuming a standard deviation of 2.5 mg, 5% statistical significance, and 80% power. To allow for a possible 10% dropout, the sample size was increased to 36 patients.

The full analysis population included all subjects who met the study eligibility criteria and were subsequently randomized to 1 of the 2 groups. Continuous variables were summarized using either mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Normality was assessed using normal probability plots. Categorical variables were summarized by number (percentage).

The primary analysis estimates the difference in mean prednisolone dose at 12 months between patients randomized to simvastatin and placebo using a linear regression model that adjusts for baseline prednisolone dose (analysis of covarience). Patients were analyzed according to the groups to which they had been randomized (intention to treat).

Use of second-line immunosuppression at 24 months was analyzed using a chi-square test, as was the number of disease relapses by 24 months. Time to first relapse was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier estimator, and differences between the groups were compared using the log-rank test. Blood cholesterol and lipid levels at 24 months were analyzed descriptively.

Results

The study included 35 patients who were assessed for eligibility, of which 32 were randomized to receive either simvastatin 80 mg daily or placebo (Fig S1). Two patients were found not to be eligible, and a third passed away (because of an unrelated cause). The first subject was recruited in September 2015, and the final trial visit was in July 2018. All patients completed the primary outcome at 12 months, and 21 patients completed the 24-month follow-up visit. The baseline demographic data were comparable between the 2 groups (Table 2). Average (± standard deviation) age at baseline was 44.4 ± 7.8 years for the simvastatin group and 48.3 ± 11.2 years for the placebo group. Average dose of prednisolone at baseline was 15.0 ± 8.7 mg for the simvastatin group and 16.7 ± 9.5 mg for the placebo group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics for Patients in Simvastatin and Placebo Groups

| Baseline Criteria | Simvastatin | Placebo | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 44.4 ± 7.8 | 48.3 ± 11.2 | 0.264 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 10 (62.5) | 10 (62.5) | 1.000 |

| Duration of uveitis, (yrs) | 6.8 ± 4.7 | 10.8 ± 9.3 | 0.135 |

| Bilateral disease, n (%) | 13 (81.3) | 15 (91.8) | 0.600 |

| Anatomic location, n (%) | |||

| Intermediate uveitis | 8 (50) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Posterior uveitis | 3 (18.8) | 3 (18.8) | 0.894 |

| Panuveitis | 5 (31.3) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Associated systemic disease, n (%) | 7 (43.8) | 3 (18.8) | 0.127 |

| Prednisolone dose (mg) | 15 ± 8.7 | 16.7 ± 9.5 | 0.505 |

Table 3.

Prednisolone Dose for Patients in Simvastatin and Placebo Groups from Baseline up to 12 Months

| Prednisolone Dose, mg, Mean ± SD | Patients with Prednisolone < 10 mg/day, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Simvastatin | Placebo | Simvastatin | Placebo |

| 0 | 15 ± 8.7 | 16.7 ± 9.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 12.7 ± 10.9 | 15.8 ± 11.4 | 7 (43.8) | 6 (37.5) |

| 26 | 16.1 ± 16.3 | 20.1 ± 23.6 | 6 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) |

| 38 | 8.8 ± 4.0 | 14.1 ± 17.9 | 6 (37.5) | 7 (43.8) |

| 52 | 16.2 ± 19.6 | 12.4 ± 11.2 | 8 (50) | 6 (37.5) |

SD = standard deviation.

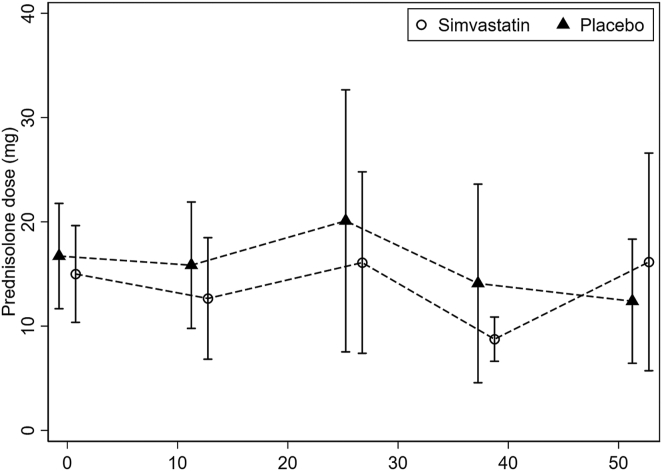

All patients were included in the primary analysis. The mean difference of oral prednisolone from baseline was calculated for the placebo and simvastatin groups (Table 3). There was a trend of reduction in daily oral prednisolone dose in the simvastatin group, but it was not significant. The mean prednisolone dose at 12 months was 16.2 ± 19.6 mg/day for patients in simvastatin group and 12.4 ± 11.2 mg/day for patients in placebo group (Table 3, Fig 2). At 12 months, there was no difference in the mean change in prednisolone dose between the 2 groups (delta change between simvastatin and placebo groups was 3.62 mg; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −8.15 to 15.38; P = 0.54). There was an increase in the percentage of patients requiring a prednisolone dose of < 10 mg/day with 50% (n = 8) of patients in the simvastatin group and 37.5% (n = 6) of those in the placebo group. By 24 months, there was no difference in the change in prednisolone dose with an average of 7.7 ± 6.2 mg/day and 7.8 ± 2.5 mg/day for the simvastatin and placebo groups, respectively (delta change between simvastatin and placebo groups was −0.34 mg; 95% CI: −4.71 to 4.03, P = 0.87). The percentage of patients using a prednisolone dose < 10 mg/day was 45.5% (n = 5) of patients in the simvastatin group and 50% (n = 5) of those in the placebo group. There was no difference in the time to reach a prednisolone dose of < 10 mg/day, and the median was 52 weeks (95% CI: 12–66) and 26 weeks (95% CI: 12-∞) for the simvastatin and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.62).

Figure 2.

Mean dose of prednisolone for simvastatin and placebo groups from baseline up to 12 months with 95% confidence intervals.

At baseline, 12 patients were receiving a second-line agent in addition to prednisolone, 6 in the simvastatin group and 6 in the placebo group. Of these, 10 were using mycophenolate mofetil and 2 methotrexate. By 24 months, there was no difference in the percent of patients able to reduce or stop their second-line agent treatment, with 33.3% in the simvastatin group and 50% in the placebo group (P = 0.56).

Disease Activity

Disease activity scores at each study visit were analyzed for all patients. At baseline, 6 (37.5%) patients in the placebo group and 8 patients (50%) in the simvastatin group had active disease (Fig 3). By 3 months, the number of patients with active disease increased to 9 patients (56.3%) in the placebo group and decreased to 7 patients (43.8%) in the simvastatin group. This remained steady throughout follow-up, and by 12 months, 10 patients (62.5%) in the placebo group and 9 patients (56.3%) in the simvastatin group had active disease. At 24 months, there were disease activity data regarding 21 patients (11 in the simvastatin group and 10 in the placebo group). The proportion of patients who had active disease was higher, but not significantly, in the simvastatin group (5/11, 45.5%) compared with the placebo group (1/10; 10%; P = 0.07).

Figure 3.

Portion of patients with active disease for simvastatin (A) and placebo (B) groups at baseline up to 12 months.

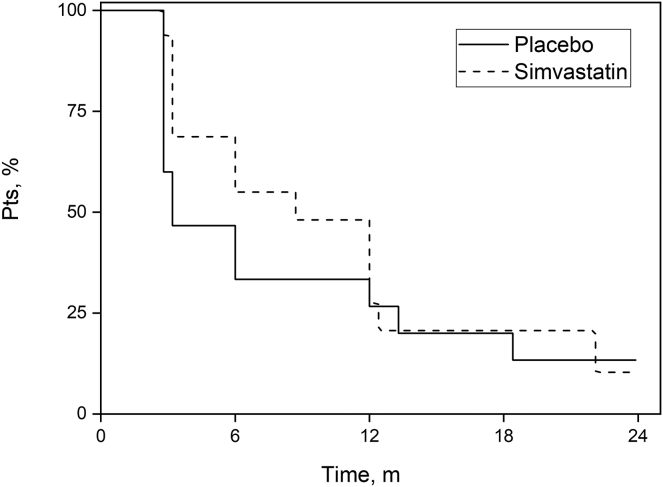

By 24 months, disease quiescence was noted in 31 patients, and relapse had occurred in 26 cases (13 patients in each group), with a median time to relapse of 6 months (95% CI: 2.11–9.89). Median time to relapse for the placebo group was 14 weeks (95% CI: 12–52) compared with 38 weeks (95% CI: 14–54) for the simvastatin group (Fig 4). Although the time to first relapse was longer in the simvastatin group, it was not significant.

Figure 4.

Survival to first relapse for simvastatin and placebo groups.

Safety of Simvastatin

Simvastatin was safe and well tolerated by most patients. Table 4 describes the change in blood cholesterol and lipid levels from baseline to 24 months. In the simvastatin group, there was a reduction in total cholesterol levels from 5.29 ± 1.01 mmol/L to 4.56 ± 1.48 mmol/L. In the placebo group, the cholesterol levels remained stable from 5.59 ± 1.08 mmol/L to 5.42 ± 0.77 mmol/L, although there was no significant difference between the groups in the average change in cholesterol levels.

Table 4.

Blood Tests for Patients in Simvastatin and Placebo Groups for Baseline and 24 Months

| Baseline, Mean ± SD |

24 Mos, Mean ± SD |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simvastatin | Placebo | Simvastatin | Placebo | ||

| RBG, mmol/L | 6.68 ± 3.39 | 5.25 ± 1.09 | 5.29 ± 1.12 | 5.71 ± 2.94 | 0.400 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mmol (%) | 6.21 ± 1.77 | 5;.76 ± 0.33 | 6.16 ± 1.06 | 5.63 ± 0.41 | 0.504 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.29 ± 1.01 | 5.59 ± 1.08 | 4.56 ± 1.48 | 5.42 ± 0.77 | 0.172 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.88 ± 0.68 | 3.07 ± 0.75 | 2.14 ± 1.31 | 2.63 ± 0.86 | 0.253 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.76 ± 0.62 | 1.89 ± 0.61 | 1.7 ± 0.67 | 1.84 ± 0.64 | 0.713 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.42 ± 0.53 | 1.4 ± 0.58 | 1.59 ± 1.01 | 2.15 ± 0.9 | 0.278 |

| Creatinine kinase, umol/L | 128.63 ± 78.88 | 136.38 ± 100.16 | 221.7 ± 198.21 | 130.43 ± 74.0 | 0.246 |

HbA1C = hemoglobin A1C; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; RBG = random blood glucose; SD = standard deviation.

There was no difference in the reduction in low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) between the groups (P = 0.25) or any significant difference in the change in high-density lipoprotein levels. Creatinine kinase levels were measured at each follow-up visit, and average levels at baseline were 128.632 ± 78.88 Umol/L for the simvastatin group and 136.38 ± 100.16 Umol/L for the placebo group. By 24 months, there was no significant difference in the change in average creatinine kinase level between the simvastatin (221.7 ± 198.21 Umol/L) and placebo groups (130.43 ± 74.0 Umol/L, P = 0.25). Similarly, there was no significant difference in liver enzyme levels between the 2 groups.

There were a total of 127 adverse events recorded throughout the trial, 51 in the placebo group and 76 in simvastatin group: among these, 5 were serious adverse events, and those were not related to the trial investigational medicinal product. In the placebo group, 2 sickle cell crises occurred, and the last attack ended in the death of that patient. In the simvastatin group, 2 serious adverse events were reported, and both were unrelated elective surgeries. During the trial, 1 patient reported she had become pregnant and was immediately removed from the trial. Her information was unmasked, and she was found to have received the placebo. She was continually followed and delivered a healthy child. Myalgia and arthralgia were reported 11 times in the placebo group and 22 times in the simvastatin group; these were mild and transient, and none of the patients had to stop their trial medication or withdraw from the trial.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the safety and efficacy of adding simvastatin 80 mg/day to the systemic immunosuppression treatment of patients with noninfectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. At 12-month follow-up, there was no significant corticosteroid-sparing effect compared with placebo. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the use of second-line immunosuppression drugs or the rate of disease quiescence, although there was a trend toward an extended time to disease relapse among patient in the simvastatin group. Simvastatin was well tolerated and resulted in a significant reduction in total cholesterol and LDL levels.

Studies using in vitro models and animal models suggest that statins modulate the immune system through alterations in cell surface molecules, cellular interactions, signaling proteins, and nuclear factor expression and function.15 The immunomodulatory effect of statins is exerted either directly on cells, such as interfering with T lymphocyte proliferation,16,17 inhibiting the expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on B cells,18 or through inhibition of cellular interactions and signaling molecules, such as tumor necrosis factor α,19 a potent proinflammatory cytokine that induces apoptosis of retinal cells.20 By influencing the cytokine balance from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory, statins modulate the immune response and achieve an immunomodulatory effect.18,21 Additionally, statins block the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 pathway, which is responsible for the interaction between the vascular endothelium and lymphocytes, therefore, statins interfere with transvascular migration of lymphocytes,22 thereby reducing the number of lymphocytes reaching the sites of inflammation.

Previous studies have reported on the immunomodulatory effect of statins in uveitis. In a retrospective population-based study, the use of statins was found to have a protective effect on uveitis development throughout 2 years.8 The study identified 108 incident cases of uveitis with an incidence of 19% among statin users, compared with 30% in patients not treated with statins. Shirinsky et al23 randomized 50 patients with noninfectious uveitis to receive conventional immunomodulatory treatment with or without the addition of simvastatin 40 mg for 2 months. Although the study was open-labeled, they found that the addition of simvastatin resulted in significantly lower anterior chamber inflammation and visual acuity, with no serious systemic adverse events. Another study also reported a twofold reduction in the risk of ocular inflammatory disease in male patients who used statins, compared with a control group, over 5 years.9 Although these findings did not reach statistical significance, the risk reduction was higher with longer duration of statin use. Although these were not randomized, masked, controlled trials and had a variably short follow-up, they were able to demonstrate at least a short-term effect on reducing the dose of concomitant systemic corticosteroids. In our study, we were also able to show that up to 9 months of follow-up, there was a trend toward a reduction in systemic corticosteroids, although it was not demonstrated at the 12-month primary end point. Furthermore, despite choosing a very small difference in treatment effect (a 2.5 mg difference in daily dose), the lack of a significant difference between the 2 treatment arms does not support a clear advantage for this treatment. It is possible that this result reflects a moderate immunomodulatory effect for simvastatin that does not result in a sustained impact compared with that of systemic corticosteroids. This study was limited by including active patients already receiving systemic corticosteroids and second-line immunosuppression. Their robust effect may have overshadowed that of simvastatin and the primary outcome. A larger sample size or a different primary outcome, such as a dichotomous outcome (percent of patients achieving a daily dose < 10 mg/day), may have demonstrated a clearer result. Alternatively, the isolated effect of simvastatin could be explored on time to relapse among quiescent patients receiving no treatment. Our results do offer some support for quiescence maintaining role, as seen in the extended time to relapse seen in our study.

Systemic immunosuppression with corticosteroids in uveitis is known to increase patient’s risk of CVD.24, 25, 26 Patients with chronic ocular inflammatory disease taking systemic immunosuppression are also at risk of developing CVDs. Given the long-term exposure to corticosteroids and second-line immunomodulatory agents required in patients with sight-threatening uveitis, this would warrant treatment to reduce high serum cholesterol levels, particularly LDL, and minimize the risk of CVD. In our study, the mean total cholesterol level was higher than normal, with 60% of patients having high serum cholesterol level at baseline. Simvastatin reduced total cholesterol and LDL levels, which supports the well-established action of simvastatin on serum lipid levels, adding an additional indication to treatment in such patients who are expected to continue using corticosteroids and immunosuppression drugs for many years.

Although the results of this study were unable to support the use of simvastatin 80 mg/day as a significant immunomodulatory agent, the results offer support for its role as an adjunctive treatment, potentiating the effect of other agents in prolonging the time to relapse and protecting patients for some of the systemic side effects linked to long-term corticosteroid use. This study supports the safety of simvastatin in patients with uveitis and its role in maintaining quiescent disease.

Manuscript no. XOPS-D-22-00269R1.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available atwww.ophthalmologyscience.org

Disclosures:

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The authors made the following disclosures: O.T.N.: Participation – Tarsier Inc, Bayer Inc.

The other authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article. Supported by a grant from the J P Moulton charitable foundation, London, UK (grant #516997).

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (REC reference: 15/LO/0084) and adhered to the Tenants of the Declaration of Helsinki (Protocol number: 14/0172; EudraCT number: 2014-003119-13; IRAS project ID: 156966). All participating patients were included after providing written informed consent.

No animal subjects were used in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Al-Janabi, Sharief, Ding, Ambler, Lightman, Tomkins-Netzer.

Data collection: Al-Janabi, Sharief, Qassimi, Chen, Ladas, Lightman, Tomkins-Netzer.

Analysis and interpretation: Al-Janabi, Sharief, Chen, Ding, Ambler, Lightman, Tomkins-Netzer.

Obtained funding: Lightman, Tomkins-Netzer

Overall responsibility: Al-Janabi, Sharief, Qassimi, Chen, Ding, Ambler, Ladas, Lightman, Tomkins-Netzer.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Suhler E.B., Thorne J.E., Mittal M., et al. Corticosteroid-related adverse events systematically increase with corticosteroid dose in noninfectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis: post hoc analyses from the VISUAL-1 and VISUAL-2 trials. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:1799–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rathinam S.R., Babu M., Thundikandy R., et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil for noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1863–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangaputra S., Newcomb C.W., Liesegang T.L., et al. Methotrexate for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2188–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kacmaz R.O., Kempen J.H., Newcomb C., et al. Cyclosporine for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorne J.E., Jabs D.A., Qazi F.A., et al. Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert R., Al-Janabi A., Tomkins-Netzer O., Lightman S. Statins as anti-inflammatory agents: a potential therapeutic role in sight-threatening non-infectious uveitis. Porto Biomed J. 2017;2:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pbj.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohno H., Sakai T., Saito S., et al. Treatment of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis with atorvastatin and lovastatin. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borkar D.S., Tham V.M., Shen E., et al. Association between statin use and uveitis: results from the Pacific ocular inflammation study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yunker J.J., McGwin G., Jr., Read R.W. Statin use and ocular inflammatory disease risk. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1869-5760-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chataway J., Schuerer N., Alsanousi A., et al. Effect of high-dose simvastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:2213–2221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarey D.W., McInnes I.B., Madhok R., et al. Trial of atorvastatin in rheumatoid arthritis (TARA): double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2015–2021. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontana J.R., Moss J., Stylianou M., et al. Atorvastatin treatment for pulmonary sarcoidosis, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A4755. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabs D.A. Immunosuppression for the uveitides. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabs D.A., Nussenblatt R.B., Rosenbaum J.T. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain M.K., Ridker P.M. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:977–987. doi: 10.1038/nrd1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakrabarti R., Engleman E.G. Interrelationships between mevalonate metabolism and the mitogenic signaling pathway in T lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12216–12222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuthbert J.A., Lipsky P.E. A product of mevalonate proximal to isoprenoids is the source of both a necessary growth factor and an inhibitor of cell proliferation. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1991;104:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Youssef S., Stuve O., Patarroyo J.C., et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes a Th2 bias and reverses paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;420:78–84. doi: 10.1038/nature01158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadeghi M.M., Tiglio A., Sadigh K., et al. Inhibition of interferon-gamma-mediated microvascular endothelial cell major histocompatibility complex class II gene activation by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Transplantation. 2001;71:1262–1268. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson R., Ho C.E., Tan Q.S., et al. Fluvastatin downregulates VEGF-A expression in TNF-alpha-induced retinal vessel tortuosity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52 doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwak B., Mulhaupt F., Myit S., Mach F. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat Med. 2000;6:1399–1402. doi: 10.1038/82219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida M., Sawada T., Ishii H., et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor modulates monocyte–endothelial cell interaction under physiological flow conditions in vitro: involvement of Rho GTPase-dependent mechanism. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1165–1171. doi: 10.1161/hq0701.092143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirinsky I.V., Biryukova A.A., Shirinsky V.S. Simvastatin as an adjunct to conventional therapy of non-infectious uveitis: a randomized, open-label pilot study. Curr Eye Res. 2017;42:1713–1718. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2017.1355468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirodkar A-l, Taylor S., Lightman S. Retinal vein occlusions in patients with uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2726. [Google Scholar]

- 25.del Rincón I., Battafarano D.F., Restrepo J.F., et al. Glucocorticoid dose thresholds associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:264–272. doi: 10.1002/art.38210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ocon A.J., Reed G., Pappas D.A., et al. Short-term dose and duration-dependent glucocorticoid risk for cardiovascular events in glucocorticoid-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1522–1529. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.