Abstract

Background:

Amount of opioid use correlates poorly with procedure-related pain; however, prescription limits raise concerns about inadequate pain control and impacts on patient-reported quality indicators. There remain no consistent guidelines for postoperative pain management after carpal tunnel release (CTR). We sought to understand how postoperative opioid use impacts patient-reported outcomes after CTR.

Methods:

This is a pragmatic cohort study using prospectively collected data from all adult patients undergoing uncomplicated primary CTR over 17 months at our center. Patients were categorized as having received or not received a postoperative opioid prescription, and then as remaining on a prescription opioid at 2-week follow-up or not. Questionnaires were completed before surgery and at 2-week follow-up. We collected brief Michigan Hand questionnaire (bMHQ) score, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health score, satisfaction, and pain score.

Results:

Of 505 included patients, 405 received a postoperative prescription and 67 continued use at 2-weeks. These 67 patients reported lower bMHQ, lower satisfaction, and higher postoperative pain compared to those that discontinued. Multivariable regressions showed that receiving postoperative prescriptions did not significantly influence outcomes or satisfaction. However, remaining on the prescription at 2 weeks was associated with significantly lower bMHQ scores, particularly in patients reporting less pain.

Conclusions:

Patients remaining on a prescription after CTR reported worse outcomes compared to those who discontinued. Unexpectedly, the widest bMHQ score gap was seen across patients reporting lowest pain scores. Further research into this high-risk subgroup is needed to guide policy around using pain and patient-reported outcomes as quality measures.

Level of Evidence: Level III.

Keywords: opioids, carpal tunnel release, patient-reported outcomes, satisfaction

Introduction

Up to 13% of patients who do not use opioids regularly and then undergo outpatient hand surgery develop long-term opioid use.1,2 With millions of patients undergoing these surgeries each year, the number of patients at risk is high. Surgeons are among the highest prescribers of opioids, with opioids routinely prescribed for postoperative pain management.3-5 Although surgeons are aware of the opioid crisis and have supported numerous efforts to limit or reduce opioid prescriptions and use alternative pain management, some are reluctant to reduce or completely discontinue prescribing since postoperative pain control is a focus of care improvement and quality efforts.6,7 Similarly, patient satisfaction and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are important components of quality measures, including in the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys, that can drive reimbursement. 8 With finances tied to outcomes and satisfaction, this system may inadvertently encourage overprescribing to avoid lower scores.8-11

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) surgery is one of the most common surgeries performed in the United States, with an estimated 500,000 procedures performed annually across many different surgical specialties, most commonly plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery, and neurosurgery. 12 Despite this, CTR does not have consistent guidelines for postoperative pain management. 10 Although studies support that many patients do well without opioid medication after CTR, they are often still prescribed.11,13 Individual patient-level factors, such as mental illness or diagnoses of chronic pain, contribute to patient satisfaction, patient-reported pain scores, and remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription, even outside of procedure-related pain.1,14,15 However, the impact of receiving and then remaining on a postoperative opioid on PROs, satisfaction scores, or postoperative pain scores after CTR remains inadequately understood. Studies have reported on these associations at the population level8,15,16 but without valuable individual-level patient-reported and prescription data.

Given the opioid crisis, the inclusion of PROs and patient satisfaction as measures for quality of care, 17 and the lack of standardized guidelines around postoperative opioid prescribing, 14 it is important to understand the effect of postoperative opioid use on: (1) PROs; and (2) patient satisfaction. We prospectively collected PROs, pain scores, and satisfaction scores for all patients undergoing CTR at our center. We hypothesized that receiving a postoperative pain prescription would be associated with significantly lower PROs and satisfaction scores, and that remaining on a postoperative pain prescription at 2-week follow-up would also be associated with significantly lower PROs and satisfaction scores.

Materials and Methods

This study analyzed data prospectively collected from patients seen at our center between January 1, 2018 and May 31, 2019. We obtained approval from our institutional review board. All patients provided consent for use of their reported data for research before any data collection; however, none were specifically enrolled in a study as these data were collected as part of standard of care in our center. Patients were identified using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for CTR: 29848, endoscopic carpal tunnel release and 64721, neuroplasty and/or transposition; median nerve at carpal tunnel. Procedure type was based on the surgeon, with 9 of our surgeons performing endoscopic release and 3 performing open as their standard practice. We excluded patients under 18 years of age, those who underwent bilateral CTR, those undergoing revision CTR, those with a surgical site infection diagnosed in the first 2 weeks, and those who underwent any other types of surgery, either on the same day or within 3 months before or after CTR. No specific prescribing guidelines are used at our center, and there were no specific prescribing interventions implemented during this study.

Outcome Measures

All questionnaires were completed through a web-based system (OBERD, Columbia, Misssouri) before surgery and at 2-week follow-up. This included obtaining a history of chronic pain diagnoses as well as any chronic painful conditions including fibromyalgia, neuropathy, gout, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. We also collected surgical history, current medications including current opioid prescriptions, and demographics, as well as all PRO measures, satisfaction questionnaires, pain scores, and prescription opioid use. Patients reported whether they had received a postoperative opioid prescription at discharge, and if they were still taking any prescription opioids at the time of follow-up. We used electronic medical record data to confirm initial and subsequent prescription reporting was accurate. All patients included in this study had complete questionnaire data for both preoperative and postoperative visits.

Patients completed the brief Michigan Hand Questionnaire (bMHQ) at each visit. The bMHQ has been validated for use in this population and has been shown to comprehensively evaluate patient-reported hand function, pain, satisfaction, and appearance. A higher score indicates better hand function and satisfaction with less pain. While there are no available minimal clinically important difference (MCID) data for the bMHQ in carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), previous studies have reported the MCID for the full-length MHQ for patients with CTS is 13 and 8 for function and work, respectively. 18 This provides some guidance when evaluating the clinical meaningfulness of changes in bMHQ score. We used the National Institutes of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Mental Health (PROMIS GMH) questionnaire to assess patient well-being and mental health; of note, GMH does include a question about pain.

Patients reported pain ranging from 0 indicating no pain at all to 10 indicating the greatest pain imaginable. Patient satisfaction was also evaluated and scored using 2 questions derived from the CAHPS survey, with 1 indicating dissatisfaction and 10 indicating satisfaction with care.

Statistical Analysis

We categorized patients based on receiving a postoperative pain prescription at discharge versus not receiving a prescription; patients were then further divided based on those who reported continuing to take prescribed opioids at 2-week follow-up visit versus those who reported discontinuing their postoperative prescription. Continuing to take prescriptions was defined as patients who were still using postoperative opioids regardless of if it was only one pill per day or if they were taking them every 4 or 6 hours as initially prescribed. We examined the distribution of patients by pain score to confirm that they were adequately balanced across each group of interest. We compared differences in patient age, sex, type of CTR, preoperative prescription pain medication use, medical history, and PRO scores between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher’s exact test, and χ2 analysis as appropriate (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Characteristics Based on Receiving a Postoperative Opioid Prescription.

| Patient characteristics | Patients who received a postoperative opioid prescription (N = 405) |

Patients who did not receive a postoperative opioid prescription (N = 100) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median (IQR) | N (%) | Median (IQR) | P value | |

| Patient age | 56.5 (48.9-65.0) | 62.3 (52.1-71.9) | <.05* | ||

| Female | 271 (66.9) | 64 (64.0) | .58 | ||

| Patients undergoing endoscopic CTR | 325 (80.2) | 87 (87.0) | .12 | ||

| Medical diagnosis related to chronic pain (eg, fibromyalgia) | 34 (8.4) | 11 (11.0) | .41 | ||

| Preoperative pain medication use | 81 (20) | 23 (23) |

.61 | ||

| Preoperative PROMIS GMH score | 50.8 (45.8-56.0) | 50.8 (45.8-56.0) | .92 | ||

| Postoperative PROMIS GMH score | 50.8 (45.8-56.0) | 53.3 (45.8-59.0) | .40 | ||

| Preoperative brief MHQ score | 47.9 (35.4-60.4) | 49.0 (35.4-60.4) | .22 | ||

| Postoperative brief MHQ score | 52.1 (41.7-66.7) | 58.3 (41.7-66.7) | .31 | ||

| Preoperative pain score | 7 (4.5-8) |

7 (4-8) |

.72 | ||

| Postoperative pain score | 4 (2.5-6) |

5 (3-7) |

.09 | ||

| Postoperative satisfaction score | 9.4 (7.5-10) | 9.9 (7.6-10) | .60 | ||

Note. IQR = interquartile range; CTR = carpal tunnel release; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GMH = Global Mental Health; MHQ = Michigan Hand Questionnaire.

Denotes significance at α = 0.05.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Characteristics Based on Remaining on a Postoperative Opioid Prescription at 2-Week Follow-Up.

| Patient characteristics | Patients who remained on a postoperative opioid prescription (N = 67) |

Patients who discontinued postoperative opioid prescription (N = 295) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median (IQR) | N (%) | Median (IQR) | P value | |

| Patient age | 57 (50-64) | 57 (49-66) | .67 | ||

| Female | 50 (74.6) | 194 (65.8) | .16 | ||

| Patients undergoing endoscopic CTR | 53 (79.1) | 240 (81.4) | .67 | ||

| Medical diagnosis related to chronic pain (eg, fibromyalgia) | 9 (13.4) | 23 (7.8) | .15 | ||

| Preoperative pain medication use | 16 (23.9) | 59 (20.0) | .51 | ||

| Preoperative PROMIS GMH score | 48 (44-53) | 51 (44-56) | .18 | ||

| Postoperative PROMIS GMH score | 46 (44-53) | 51 (46-56) | <.05* | ||

| Preoperative brief MHQ score | 48 (33-52) | 50 (35-63) | .16 | ||

| Postoperative brief MHQ score | 42 (29-54) | 54 (46-67) | <.05* | ||

| Preoperative pain score | 8 (6-9) |

6 (4-8) |

<.05* | ||

| Postoperative pain score | 5 (4-7) |

4 (2-6) |

<.05* | ||

| Postoperative satisfaction score | 8.4 (6.8-10) | 9.5 (7.8-10) | <.05* | ||

Note. IQR = interquartile range; CTR = carpal tunnel release; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GMH = Global Mental Health; MHQ = Michigan Hand Questionnaire.

denotes significance at α = 0.05.

Bivariate linear regressions were used to assess the relationship between independent variables, including receiving or remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription, and both bMHQ and satisfaction scores (Appendices 1 and 2, available in Supplemental Materials). Multivariable linear regressions were then constructed from bivariate results as well as conceptual frameworks based on current literature to study how independent variables, such as patient age, sex, medical history, and receiving or remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription, affected outcome scores. Additionally, an interaction term between postoperative pain score and remaining on postoperative pain prescription at follow-up was tested to check whether the association between the outcome and pain scores was modified by remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription.

Results

A total of 618 patients who underwent CTR were identified. We excluded 108 patients for having multiple CTR surgeries or having other surgeries. One patient was excluded for being under 18 years of age, and 4 patients were excluded due to postoperative infectious complication. The mean age of the 505 CTR patients included was 57 years (SD = 13; range, 22 – 92 years). Women constituted 66% of the study population (N = 335). Of the patients, 81% underwent endoscopic CTR. The 405 patients who did not receive a prescription tended to be older, 56.5 (48.9, 65.0) vs 62.3 (52.1, 71.9); P < .001; Table 1. The 67 patients who remained on a postoperative prescription had worse PROMIS GMH, bMHQ, and satisfaction scores (Table 2).

Table 3 shows results from our multivariable linear regression models for postoperative satisfaction scores. Results indicate that remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription at follow-up did not impact satisfaction scores (Table 3). Postoperative GMH score was associated with satisfaction scores (0.04; [95% CI: 0.00, 0.07]; P = .04; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Linear Regression for Postoperative Satisfaction Scores.

| Risk factor | Adjusted linear regression coefficient | 95% confidence intervals | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age | −0.03 | −0.05 to −0.01 | .01* |

| Female | −0.25 | −0.86 to 0.36 | .42 |

| Surgery type | |||

| Endoscopic | REF | ||

| Open | −0.57 | 0.00 to 0.07 | .10 |

| Postoperative GMH score | 0.04 | 0.00 to 0.07 | .04* |

| Postoperative pain score | −0.10 | −0.22 to 0.03 | .12 |

| Remained on a postoperative pain prescription at follow-up | 0.03 | −1.9 to 1.9 | .98 |

| Interaction between postoperative pain score and remaining on postoperative pain prescription at follow-up | −0.02 | −0.31 to 0.27 | .88 |

Note. GMH = Global Mental Health.

denotes significance at α = 0.05; R2 = .14.

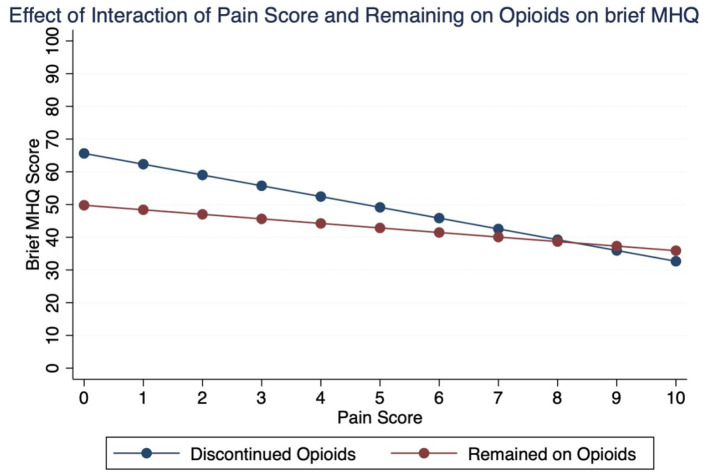

Multivariable regressions for postoperative bMHQ scores found that open CTR was associated with lower bMHQ scores (-4.9; [95% CI: -8.9, -0.85]; P = .02; Table 4). Postoperative GMH was associated with bMHQ score, though of unclear clinical meaningfulness (0.46; [95% CI: 0.25, 0.66]; P < .001; Table 4). Both postoperative pain score and remaining on an opioid prescription were associated with decreases in bMHQ score (Table 4). The interaction term between postoperative pain score and remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription was significant for bMHQ scores (1.8; [95% CI: 0.42, 3.0]; P = .01; Table 4). This indicates that for each unit increase in postoperative pain score, patients who remained on a postoperative prescription saw a 1.8-point increase in their bMHQ score compared to their counterparts who discontinued their postoperative prescription but reported the same pain score (Figure 1). This between-group difference was most notable for patients reporting the lowest pain scores while still using opioids, as they tended to report even lower bMHQ scores as compared to the patients that discontinued opioid use (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Multivariable Linear Regression for Postoperative Brief MHQ Scores.

| Risk factor | Adjusted linear regression coefficient | 95% confidence intervals | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age | 0.06 | −0.07 to 0.19 | .34 |

| Female | −0.47 | −4.1 to 3.2 | .80 |

| Surgery type | |||

| Endoscopic | REF | ||

| Open | −4.9 | −8.9 to −0.85 | .02* |

| Postoperative GMH score | 0.46 | 0.25 to 0.66 | <.001* |

| Postoperative pain score | −2.7 | −3.5 to −2.0 | <.001* |

| Remained on a postoperative pain prescription at follow-up | −13 | −24 to −1.2 | .03* |

| Interaction between postoperative pain score and remaining on postoperative pain prescription at follow-up | 1.8 | 0.42 to 3.0 | .01* |

Note. MHQ = Michigan Hand Questionnaire; GMH = Global Mental Health.

denotes significance at α = 0.05; R2 = .38.

Figure 1.

Plot showing the relationship between patient-reported pain score and patient-reported outcome (brief MHQ) as it varies by whether the patient was still using opioids or not. Note the distinct difference between patient-reported outcome especially in patients scoring < 3 pain but still using opioids compared to those who have stopped opioids.

Note. MHQ = Michigan Hand Questionnaire.

Discussion

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 58 opioid prescriptions were written for every 100 Americans. 19 A national survey found that 41% of patients with prescription opioid misuse obtained the prescription from a friend or family member, 20 emphasizing the importance of effective opioid stewardship, especially in the setting of postoperative pain management.1,16,21 With CAHPS including PROs and patient satisfaction as measures of care quality, there is concern that physicians may feel pressured to prescribe unnecessary opioids in order to influence PROs, patient satisfaction, and reimbursement.9-11 Although CAHPS removed questions about patient experience with pain, 22 understanding the complex relationships between these patient-reported data elements and opioids remains important.

We found that there were no significant differences in patient demographics, medical history, bMHQ scores, pain scores, or postoperative satisfaction scores between patients who received a postoperative opioid prescription and those who did not. However, of those who received opioids, patients who remained on a prescription at 2-weeks had similar preoperative PROs but significantly worse postoperative PROs and pain scores. Perhaps most notably, we found that the largest gap in bMHQ scores was seen in patients reporting the lowest pain scores. This supports the notion that factors aside from pain drive the decision to continue opioid use and similarly may impact patient reporting on questionnaires.

This study has several limitations. Patient-reported outcomes can have associated response bias; however, PROs have repeatedly been shown as reliable in measuring outcomes.23,24 Patient satisfaction was scored based on 2 questions—this may not be adequate in truly gauging patient satisfaction. The questions were both derived from the CAHPS, supporting their validity as representative of questions that may be used to indicated care quality. Because we did not control prescribing decision-making, and do not know whether the decision to prescribe was provider or patient driven, there is likely some self-selection between the group of patients who did not receive any prescription and those who received one. However, this does reflect standard daily care provided in a busy hand surgery center at the time of data collection.

There may be limits to transferability due to inherent differences in geographical location and patients of our center; however, this study provides insights into how patient characteristics can be related to patient behavior and postoperative outcomes and could provide clinical insight for pain management and PROs in CTR patients. Similarly, exclusion of patients with multiple surgeries, bilateral CTR, or adverse events could lead to selection bias. We chose to exclude these groups to minimize additional confounders to our analyses, and by excluding these patients we were able to focus on clinician prescribing habits and data from patients undergoing isolated primary CTR. And, considering the nature of these PRO data and the analyses used, we can only evaluate certain associations between these measures and prescription use, providing a likely incomplete picture of the complex relationships involved.

Of note, CTS severity does not directly drive opioid prescription decision-making for any of the surgeons at our center; however, the impact of CTS severity cannot be controlled for in our study and may impact the findings. Additionally, despite having a large cohort size, the subgroups are smaller and more susceptible to bias from outliers. The distribution of patients reporting different pain scores was well balanced, which we believe minimized this bias. Lastly, both endoscopic and open CTRs were included in this study, which could have affected outcomes. The distribution of endoscopic to open CTRs was consistent throughout the study between patient subgroups, but open CTR was associated with significantly lower bMHQ in the early postoperative period, consistent with previous literature.25,26

We used the validated bMHQ to gauge patient outcomes. We found that postoperative PROMIS GMH was significantly associated with bMHQ, supporting many other reports that patients’ mental health correlates with their perception of their postoperative outcome.27-29 Notably for our specific hypotheses regarding the impact of opioids on PRO reporting, we found that the effect of remaining on a prescription varied by pain score despite all patient subgroups having similar scores preoperatively and receiving similar care. Patients reporting less pain reported significantly worse bMHQ scores if they remained on a prescription compared to patients who reported the same level of pain but had discontinued their prescription. What other issues were driving the perceived need to continue on opioids, and the overall lower bMHQ reporting even when controlling for pain, GMH, and other factors, remains unclear. This emphasizes the need to further investigate these relationships. There is currently no literature that robustly evaluates this phenomenon, and future randomized controlled trials could elucidate the complex relationships between pain scores, remaining on an opioid prescription, and bMHQ (or other outcomes) scores.

Patient-level factors, such as depression, substance use disorders, or other psychiatric illnesses, are associated with remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription longer than anticipated.14,21,28 In this study, we used the PROMIS GMH as a broad proxy to assess these factors and incorporate them in the analyses to observe the effects of a patient’s mental health on postoperative PROs and satisfaction scores. We found patients who received a postoperative prescription had similar pre- and postoperative PROMIS GMH scores as patients who did not receive a prescription. Consistent with previous literature, patients who remained on a postoperative prescription had postoperative PROMIS GMH scores that were 5 points lower than their counterparts who discontinued their prescription, despite having similar preoperative scores14,15,21 Requesting and then receiving additional opioids after CTR may be driven by worse mental health or psychological distress and may not be related to surgical treatment or the quality of care received.30,31 Therefore, additional efforts to identify patients who would benefit from preoperative counseling regarding anxiety and management of postsurgical expectations might help in reducing postoperative opioid consumption. 31

Multiple studies have sought to elucidate whether patient satisfaction scores reflect patient outcomes or quality of care, with conflicting evidence.17,32-37 A recent study found no difference in patient satisfaction when surgeons decreased the amount of postoperative opioids prescribed. 38 In our study, we found that postoperative satisfaction scores were not significantly affected by receiving or remaining on a postoperative opioid prescription. However, patient-level factors, including mental health, are reportedly associated with patient satisfaction.39,40 Although in our analysis postoperative PROMIS GMH scores were statistically significantly associated with satisfaction, this result was likely not clinically meaningful. Additionally, though patient satisfaction is an important metric, it can also be difficult to gauge how it corresponds with care, particularly in surgery where patients are unable to directly observe substantial components of the work done by their providers. However, satisfaction scores were not significantly affected by receiving and then remaining on a postoperative prescription, confirming population-level data presented in other studies.38-40 Postoperative pain score was also not associated with satisfaction score, and there was no interaction between remaining on a postoperative prescription, postoperative pain score, and patient satisfaction.

In this study of 505 patients undergoing CTR, we found no differences in individual-level PROs between patients who received postoperative opioid prescriptions and those who did not, confirming prior studies that examined differences in group-level PROs.4,22,23 We found that receiving an opioid prescription, and then remaining on an opioid prescription, did not significantly affect postoperative satisfaction scores. However, patients who remained on postoperative prescriptions had lower postoperative bMHQ when compared with other patient subgroups, despite having similar preoperative measures and pain scores, and a similar course of treatment. This was most striking in the patients that reported lower pain scores even while remaining on opioids, as they surprisingly had the largest relative bMHQ decline. These findings suggests that factors other than quality of care or even active pain may be leading patients to report worse outcomes. How and why continuing on opioids beyond the expected postsurgical recovery period relates to these lower outcomes scores requires further study. For this group of patients, using PROs to extrapolate quality of care in order to influence hospital and provider reimbursement may not be appropriate. Confirmation through randomized, controlled trials would reduce bias from self-selection, and further elucidate the relationship between postoperative opioid prescriptions, pain reporting, and PROs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447211064365 for Prescription Opioids and Patient-Reported Outcomes and Satisfaction After Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery by Pragna N. Shetty, Kavya K. Sanghavi, Mihriye Mete and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447211064365 for Prescription Opioids and Patient-Reported Outcomes and Satisfaction After Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery by Pragna N. Shetty, Kavya K. Sanghavi, Mihriye Mete and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available in the online version of the article.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5).

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001409. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Aviram M. Giladi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

References

- 1.Johnson SP, Chung KC, Zhong L, et al. Risk of prolonged opioid use among opioid-naive patients following common hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(10):947-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley BP, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. Management of acute postoperative pain in hand surgery: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(8):1610-1619, 1619.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii MH, Hodges AC, Russell RL, et al. Post-discharge opioid prescribing and use after common surgical procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):1004-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar K, Gulotta LV, Dines JS, et al. Unused opioid pills after outpatient shoulder surgeries given current perioperative prescribing habits. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):636-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta SJ. Patient satisfaction reporting and its implications for patient care. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(7):616-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Hu HM, Brummett CM, et al. Postoperative opioid prescribing and the pain scores on hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems survey. JAMA. 2017;317(19):2013-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrico JA, Mahoney K, Raymond KM, et al. The association of patient satisfaction-based incentives with primary care physician opioid prescribing. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(6):941-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilyas AM, Miller AJ, Graham JG, et al. Pain management after carpal tunnel release surgery: a prospective randomized double-blinded trial comparing acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and oxycodone. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(10):913-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller A, Kim N, Zmistowski B, et al. Postoperative pain management following carpal tunnel release: a prospective cohort evaluation. Hand (N Y). 2017;12(6):541-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould D, Kulber D, Kuschner S, et al. Our surgical experience: open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(9):853-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandizio LC, Zhang H, Dwyer CL, et al. Opioid versus nonopioid analgesia after carpal tunnel release: a randomized, prospective study. Hand (N Y). 2021;16(1):38-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olds C, Spataro E, Li K, et al. Assessment of persistent and prolonged postoperative opioid use among patients undergoing plastic and reconstructive surgery. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21(4):286-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waljee JF, Zhong L, Hou H, et al. The use of opioid analgesics following common upper extremity surgical procedures: a national, population-based study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2):355e-364e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyu H, Wick EC, Housman M, et al. Patient satisfaction as a possible indicator of quality surgical care. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shauver MJ, Chung KC. The minimal clinically important difference of the Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(3):509-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescribing practices; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/prescribing/prescribing-practices.html. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- 18.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HCAHPS Fact Sheet; October2019. https://www.hcahpsonline.org/globalassets/hcahps/facts/hcahps_fact_sheet_october_2019.pdf.

- 21.Giladi AM, Chung KC. Measuring outcomes in hand surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40(2):313-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atroshi I, Larsson GU, Ornstein E, et al. Outcomes of endoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome among employed patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7556):1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohanzadeh S, Herrera FA, Dobke M. Outcomes of open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a meta-analysis. Hand (N Y). 2012;7(3):247-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cremers T, Zoulfi Khatiri M, van Maren K, et al. Moderators and mediators of activity intolerance related to pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(3):205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Özkan S, Zale EL, Ring D, et al. Associations between pain catastrophizing and cognitive fusion in relation to pain and upper extremity function among hand and upper extremity surgery patients. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verhiel S, Greenberg J, Zale EL, et al. What role does positive psychology play in understanding pain intensity and disability among patients with hand and upper extremity conditions? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(8):1769-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll I, Barelka P, Wang CK, et al. A pilot cohort study of the determinants of longitudinal opioid use after surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(3):694-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helmerhorst GT, Vranceanu AM, Vrahas M, et al. Risk factors for continued opioid use one to two months after surgery for musculoskeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(6):495-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, et al. Patients’ global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerant A, Fenton JJ, Kravitz RL, et al. Association of clinician denial of patient requests with patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):85-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, et al. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sequist TD, Schneider EC, Anastario M, et al. Quality monitoring of physicians: linking patients’ experiences of care to clinical quality and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1784-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rummans TA, Burton MC, Dawson NL. How good intentions contributed to bad outcomes: the opioid crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(3):344-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Louie CE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ., Jr.Association of decreased postsurgical opioid prescribing with patients’ satisfaction with surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:1049-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Q, Beal EW, Okunrintemi V, et al. The association between patient satisfaction and patient-reported health outcomes. J Patient Exp. 2019;6(3):201-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hung M, Zhang W, Chen W, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and total health care expenditure in prediction of patient satisfaction: results from a national study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(2):e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallway A, Vu J, Lee J, et al. Patient satisfaction and pain control using an opioid-sparing postoperative pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(3):316-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.North F, Crane SJ, Ebbert JO, et al. Do primary care providers who prescribe more opioids have higher patient panel satisfaction scores? SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118782547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vu JV, Howard RA, Gunaseelan V, et al. Statewide implementation of postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):680-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447211064365 for Prescription Opioids and Patient-Reported Outcomes and Satisfaction After Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery by Pragna N. Shetty, Kavya K. Sanghavi, Mihriye Mete and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447211064365 for Prescription Opioids and Patient-Reported Outcomes and Satisfaction After Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery by Pragna N. Shetty, Kavya K. Sanghavi, Mihriye Mete and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND