Abstract

This study was designed to identify the sources of social support and the perceived psychosocial benefits people diagnosed with cancer experience at a community-based cancer wellness organization. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with 31 people diagnosed with cancer who regularly used services at a community-based cancer wellness organization. Two themes were identified related to the sources of social support that participants experienced at the community-based cancer wellness organization: i) participants reported that individuals at the center (e.g., staff and volunteers) provided support, and ii) participants perceived the organization as a source of support. Further, four themes emerged related to participants’ perceptions of the psychosocial benefits of social support experienced at the community-based cancer wellness organization including i) reduced feelings of social isolation; ii) acceptance at the center in contrast to stigmatizing experiences elsewhere; iii) validation of new identity; and iv) experiences of relaxation and stress relief. The study findings demonstrate that community-based cancer wellness organizations can be a source of connection, acceptance, validation, and stress relief to people diagnosed with cancer.

Key words: Social support, cancer, community-based cancer wellness organizations, psychosocial wellbeing

Introduction

Although cancer death rates have steadily declined for the past three decades, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the U.S.1 Receiving a cancer diagnosis is typically a frightening experience that often involves uncertainty, complex treatment, psychological challenges, and increased support needs from a variety of sources (e.g., family, friends, healthcare providers, and coworkers). 2 Despite their increased need for social support, people diagnosed with cancer often report challenges receiving the social support they need following their diagnosis. 3-5 For many people diagnosed with cancer, community- based cancer wellness organizations provide assorted supportive programming and resources designed to promote psychosocial wellbeing.6-9

Community-based cancer wellness organizations are uniquely positioned to meet the varied support needs of people diagnosed with cancer. These organizations offer therapeutic resources (e.g., integrative therapies and support groups) to meet cancer-related emotional, social, and informational needs. Much of the literature on cancer support programming has focused mainly on the psychosocial benefits received through participation in support groups, counseling, and other similar programs that may be offered through community-based cancer wellness organizations.10 However, few studies have examined clients’ social support experiences at community-based cancer wellness organizations more broadly6,8,9 and, specifically, how the environment in these organizations may facilitate psychosocial wellbeing. As such, scholars have not fully examined both the psychosocial benefits clients experience through utilization of community-based cancer wellness organizations and the role of these organizations in facilitating critical social support to people diagnosed with cancer. Further, examining clients’ experiences at community-based cancer wellness organizations will contribute to a better understanding of the distinctive value these organizations have to individuals diagnosed with cancer. This study is designed to examine attributions people diagnosed with cancer make regarding sources of social support at a community-based cancer wellness organization and what psychosocial benefits people diagnosed with cancer experience through their utilization of a community-based cancer wellness organization.

Supportive communication

Scholars interested in how individuals communicate help and caring have long examined supportive communication exchanges (i.e., social support).11 Albrecht and Adelman12 identify supportive exchanges as explicitly communicative phenomena. They defined social support as “verbal and nonverbal communication between recipients and providers that helps reduce uncertainty about the situation, the self, the other or the relationship and functions to enhance perception of personal control in one’s life experience” (p. 19). Albrecht and Goldsmith13 later revised this early definition by arguing that social support allows individuals to “manage” uncertainty. Other communication scholars have similarly identified the communicative nature of social support by defining it as communication provided to help another individual that is delivered via verbal and nonverbal behavior.11,14 Research examining social support has conceptualized it in a variety of ways. Social support has been examined through messages, interactions, and social networks.11 Further, researchers have noted that social support can be studied from a functional perspective, through network analysis, and/or through examinations of perceptions of available support.13As such, the sources of the social support individuals receive (e.g., from a family member or friend) are often examined by researchers interested in supportive communication to understand who provides social support.

Social support and health

Research continues to confirm the association between social support and both physiological and psychological health benefits.15,16 For instance, a review by Uchino et al.16 of 81 research studies examining the relationship between social support and physiological health concluded that social support influences physiological health by reducing stress and leading to better cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune function. Individuals benefit from social support both directly when supportive actions protect individuals from stress (i.e., the direct effects model) and indirectly when supportive communication helps individuals to cope with the adverse effects of stress (i.e., the stress-buffering model).17 Researchers have further noted that high-quality social support (e.g., person-centered and validating support) is a predictor of better psychological and physical wellbeing.18 Extant literature also demonstrates the markedly positive impact that social support has on psychological health.17,19,20 A systematic review by Santini et al.19 concluded that having large social networks and receiving emotional and instrumental support was associated with lower levels of depression. As such, the health benefits individuals experience through social support exchanges continue to be of critical importance to health communication scholars.

The benefits of social support for people diagnosed with cancer

Social support is an ongoing and critical need for people diagnosed with cancer. Research examining the associations between social support and health benefits in the context of cancer has found a clear relationship between social support and physical and psychosocial health for people diagnosed with cancer.3,21 For example, Donovan and Farris’21 systematic review found that interpersonal communication, especially exchanges of social support, was repeatedly associated with better coping and management of stress among people diagnosed with cancer. Despite the positive associations between social support and health for people diagnosed with cancer, family members and friends are often ill-equipped to meet the distinct needs of people diagnosed with cancer.3,5,22 Hegleson and Cohen’s5 review reported that while family and friends are an important source of emotional support for people diagnosed with cancer, family and friends may express support in ways that are unhelpful (e.g., minimizing one’s level of stress) and thus, negatively impact the psychological adjustment of people diagnosed with cancer. Consequently, people diagnosed with cancer may find support groups and counseling especially beneficial in terms of addressing psychosocial challenges associated with cancer and cancer treatment.10 In addition to programming designed to address psychosocial support needs (e.g., support groups), people diagnosed with cancer may also experience physical and psychosocial benefits from participation in exercise classes and other types of activities designed specifically for people diagnosed with cancer.23

People diagnosed with cancer often seek supportive programming and resources, such as cancer support groups, exercise classes, and counseling, through community- based cancer wellness organizations. Individuals can find community-based cancer organizations across the U.S. and are often referred to these organizations through their healthcare providers.7 Although these organizations often differ in terms of specific programming offered and their funding levels, they have been recognized for providing programming that fulfills various psychological, social, and physical needs for individuals diagnosed with cancer.8,9

Given the prevalence of these organizations and their apparent value to people diagnosed with cancer, it is surprising that limited scholarship has focused directly on the value of these organizations. In particular, understanding the sources of social support within these organizations and the types of psychosocial benefits that individuals receive through utilizing their services may further demonstrate the impact of these organizations for people diagnosed with cancer. This study, therefore, is designed to identify the sources of social support within community-based cancer wellness organizations and the psychosocial benefits people diagnosed with cancer experience through social support at a community-based cancer wellness organization. This study followed a grounded theory approach to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What attributions do clients make regarding the sources of social support (e.g., individuals, cancer support groups, organization) received at a community-based cancer wellness organization?

RQ2: What psychosocial benefits, if any, do clients associate with social support experienced at a communitybased cancer wellness organization?

Materials and Methods

Midwest Cancer Wellness Center overview

Participants for the present study were recruited at the Midwest Cancer Wellness Center (MCWC, pseudonym), a small non-profit organization located in a midwestern city in the United States. The MCWC was founded by a local family, following the cancer diagnosis of a family member, to provide cancer support resources and services to community members diagnosed with cancer and their families. All services are provided free of charge to people diagnosed with cancer and their family members who visit the center. The MCWC is supported by donations, an endowment from the founding family, annual fundraising events, and a variety of community volunteers. The MCWC offers a wide array of services to clients, including integrative care (e.g., massage therapy and foot reflexology), workshops (e.g., guided meditation), support groups (e.g., a prostate cancer education group and a breast cancer support group), counseling services, exercise classes (e.g., yoga and strength building), beauty consultations (e.g., makeup and wig consultations), and financial and legal services, among other types of programming. Clients often visit the MCWC for specific programming (e.g., to attend a cancer support group or to receive a massage) and then sometimes linger at the center talking to the staff, volunteers, and/or other participants.

At the time of the data collection, the MCWC had six full-time staff members, three part-time staff members, and many community volunteers. Community volunteers were responsible for facilitating much of the MCWC’s programming and services, including performing integrative services, instructing exercise classes, and staffing the MCWC’s front desk. The MCWC served 416 clients at the time of the data collection. Clients included people diagnosed with cancer and their family members/caregivers. Most MCWC clients were female (75.9%), white (60.6%), and over 55 years old (50.3%).

Participants

There were 31 participants total, including three men and 28 women who were diagnosed with various types and stages of cancer and who regularly used the services at the MCWC. Five participants volunteered as support group facilitators or front desk volunteers in addition to utilizing the services provided by the MCWC. The ages of participants ranged from 34 to 82 years (M= 61.19; SD = 10.11). The majority of participants (n = 30) self-identified as white. Experiences and diagnoses with cancer varied by participant, with the majority of participants having a breast cancer diagnosis (70.9%, see Table 1).

Data collection

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with MCWC clients who met study inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included clients who utilized MCWC services at least four times in the past four months. The inclusion criteria were developed with assistance from the MCWC program coordinator in an effort to identify clients who regularly utilized services offered by the organization. Based on the program coordinator’s experiences with clients, individuals who used the center four or more times seemed to have a clear understanding of the organization and its programming. At the time of the data collection, 100 clients at the center met the inclusion criteria for participation in the study.

The university institutional review board (IRB) approved all research protocols prior to the start of the interviews. After receiving IRB approval, the program coordinator mailed a recruitment letter to the home addresses of clients who met the inclusion criteria. The recruitment letter explained the purpose of the study and provided participants with my contact information to set up interviews. All interviews took place at the MCWC in a private room following the informed consent process. During the interviews, participants were asked about the programs that they used at the MCWC, their experiences at the MCWC, and their experiences as a person living with cancer. All participants were compensated with a $20 gift card to a local grocery store after the completion of the interview. Interviews ranged in length from 32 minutes to 118 minutes (M = 59 minutes; SD = 15.07). Interview recordings were professionally transcribed by the transcription service Rev.com and resulted in 821 singlespaced pages of transcripts. Transcripts were edited to deidentify all participants, and pseudonyms were added to further protect participants’ identities.

Data analysis

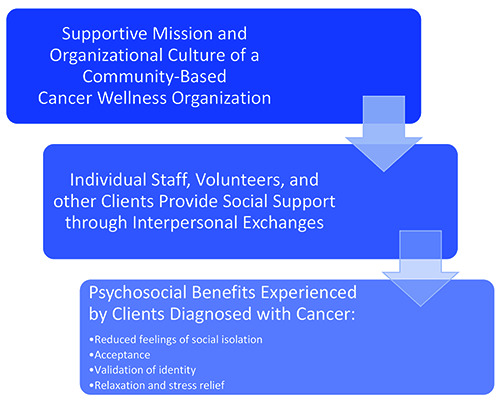

NVivo 1024 was used to facilitate analysis of all interview transcripts (e.g., assigning codes to transcript excerpts and organizing codes). I applied the principles of constructivist grounded theory and the constant comparison method throughout the coding process.25 Specifically, Charmaz’s26 steps for implementing constructivist grounded theory guided the data collection and analysis process. I developed initial codes through the use of lineby- line coding techniques where each line of data was given a short, descriptive code.27 Next, I employed focused coding to identify and categorize meaningful and/or frequently used initial codes.26 That is, I reviewed codes that aligned with reoccurring ideas and then compared them to other codes to arrive at the core categories that consistently emerged within the data. Finally, through the process of theoretical sampling, I refined categories identified and developed a list of themes associated with study research questions. By examining the connections across the themes identified in the findings, key study takeaways from the themes are integrated and presented in the form of a model (see Discussion – Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of participant demographics.

| Participant Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Race | Cancer Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alyssa | Female | 52 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Audrey | Female | 67 | White | Endometrial Cancer |

| Carmen | Female | 62 | Black | Endometrial Cancer |

| Carrie | Female | 34 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Connor | Male | 62 | White | Brain Tumor |

| Dale | Male | 59 | White | Prostate Cancer |

| Dolores | Female | 76 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Elaine | Female | 58 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Ginny | Female | 62 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Holly | Female | 53 | White | Colon Cancer |

| Howard | Male | 67 | White | Throat Cancer |

| Julia | Female | 50 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Lena | Female | 65 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Lily | Female | 49 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Lindsay | Female | 56 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Lucy | Female | 71 | White | Colon Cancer |

| Maggie | Female | 59 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Melanie | Female | 58 | White | Ovarian Cancer |

| Millie | Female | 56 | White | Brain Tumor |

| Nora | Female | 72 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Paige | Female | 51 | White | Ovarian Cancer |

| Ramona | Female | 56 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Sandra | Female | 55 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Stephanie | Female | 67 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Tabitha | Female | 59 | White | Endometrial Cancer |

| Tamra | Female | 50 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Tara | Female | 58 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Taylor | Female | 59 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Terri | Female | 82 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Vanessa | Female | 51 | White | Breast Cancer |

| Whitney | Female | 60 | White | Breast Cancer |

Results

Sources of social support at a community-based cancer wellness organization

The first research question asks what attributions clients make regarding the sources of social support (e.g., individuals, groups, and organizational support) that they receive at a community-based cancer wellness organization. Social support scholars have recognized the limitations of attributing social support to individuals alone and have argued that organizations can be perceived as sources of support in addition to individual organizational members.28 Two themes emerged related to attributions that participants made regarding sources of social support they received at the MCWC: i) individual sources of support and ii) the organization as a source of support.

Individual sources of support

Participants (n =18) repeatedly attributed the social support they received to specific individuals who were associated with the MCWC. For example, Lena said, “[The program coordinator] has just been as nice and as cooperative as can be.” Further, several participants explained that the program coordinator would often help them find useful programming or recommend specific MCWC resources. Paige referred to the Office Manager as a “savior” and further commented on the connection that they shared by explaining that she often comes to talk to the office manager when she is “totally stressed.” She went on to say that the office manager “will stop whatever she’s doing and talk to you” if you need her to. Ginny noted that in her interactions with staff members that they ensure that “you feel like you’re important, that you matter.” While participants often noted that members of the staff, center volunteers, and other clients (who they often interacted with during support groups and exercise classes) were supportive of them, more often than not, they grouped all individuals affiliated with the organization together and referenced the support as emanating from “the team” or “the staff” (see following section).

The organization as a source of support

All 31 participants identified the MCWC as a source of support. Participants regularly discussed their experiences receiving support by referencing the organization by name – explicitly or implicitly – (e.g., “this place [MCWC]” is supportive) and attributing the support they experienced at the center directly to the MCWC as an organizational entity. For example, Holly said, “The MCWC provides a lot of support.” Likewise, Lucy said, “[The MCWC] gives support... offers services that can help me.” Participants remarked that the MCWC was “a great organization” (Whitney) and a “huge support system” (Howard), indicating that the organization itself was facilitating greater access to social support. Sandra explained that she was “so grateful that the MCWC exists.” The majority of participants (n = 24) directly attributed their supportive experiences at the MCWC to the collective staff and volunteers working at the MCWC. For example, Lindsay said, “Everyone who works, who volunteers, here [at MCWC] is very kind and very caring or they wouldn’t be here.” Carmen elaborated:

[The staff is] always friendly, and they’re always nice, and they always ask how you’re doing, so they carry a positive energy.... It goes all the way from the top, the administrator, all the way down to the lady that cleans the place.

Participants also discussed the numerous ways in which the MCWC offered support to participants. For example, Millie said, “MCWC offers support not just for mental, but physical, emotional health, mental, everything. They offer it all and they do it well.” Similarly, Audrey said that the MCWC “offers so many levels of support, from therapeutic to just the psychological.” Connor noted that the MCWC was “helping” him emotionally and spiritually. Thus, participants consistently identified the many ways that they benefitted directly from the social support they saw as emanating on behalf of the MCWC as an organizational entity.

While participants may not be directly familiar with the mission of the organization, it is clear in the data through participants’ consistent recognition of the organization as being a valuable source of social support to meet their needs that they understand the purpose of the organization. That is, participants repeatedly expressed that they saw the MCWC as being there to meet the unique and challenging support needs of people diagnosed with cancer in the community. Thus, participants attributing support received to the organization suggests that they not only find the center supportive, but also understand the mission and culture of the organization in creating a supportive environment whereby organizational members deliver social support to people diagnosed with cancer.

Psychosocial benefits of social support at a community-based cancer wellness organization

The second research question examined the psychosocial benefits clients associated with social support experienced at the MCWC. Psychosocial benefits are often conceptualized as the positive mental, social, and/or emotional health outcomes associated with the perception of available and/or received social support.17 Four themes emerged related to clients’ perceptions of the psychosocial benefits of social support experienced at the MCWC: i) reduced feelings of social isolation; ii) acceptance at the center in contrast to stigmatizing experiences elsewhere; iii) validation of new identity; and iv) experiences of relaxation and stress relief.

Reduced feelings of social isolation

The first theme identified was that participants reported often feeling isolated living with cancer, but explained that through their interactions at the MCWC, they believed that those feelings of social isolation were reduced. People diagnosed with cancer often report experiencing social isolation. 29 Participants reported that the MCWC was an important way to reduce their feelings of social isolation by creating opportunities for interacting with both MCWC staff/volunteers who understand cancer and other people diagnosed with cancer who also use services offered at the center. For example, Howard and Tamra explained that they felt “isolated” following their cancer diagnosis because they were unable to interact with others. Howard said, “You’re in bed...most of the time. Maybe you’ll walk out to the kitchen or living room for a little bit. And then you’re back in bed again. You’re back into that isolation.” Likewise, Lena said, “I think there is an aloneness to [cancer].”

Through participating in center programming, participants repeatedly remarked that they did not feel the same isolation and saw improvement in their mental and emotional wellbeing.

Julia said, “This place [MCWC] was like a godsend. I wanted to do something, but I couldn’t work.” Thus, for Julia, coming to the MCWC gave her a reprieve from feeling isolated at home. Similarly, Alyssa said, “[Coming to the MCWC is] better than just sitting home and not doing anything. You get out and you see people. You just feel better.”

Feeling accepted at the center

The second theme was that participants felt that they were accepted and comfortable at the MCWC in contrast to feeling stigmatized elsewhere. People diagnosed with cancer often report feelings of otherness and being stigmatized. 30 Research indicates that people diagnosed with cancer may be labelled “cancer patient” and “cancer victim,” which is a stigmatizing identity.31 Some participants in the present study explained that people treated them differently after they were diagnosed with cancer. For example, Maggie said people would give her “pity eyes” and that she just “wanted to be treated normally.” Similarly, Howard said that a friend of his “looked at me like I was like some monster.”

Study participants discussed how other people are afraid of cancer and that they believe this fear affected their interactions with friends, family, and other people in their lives. Connor said, “People are afraid of the ‘C word’. They’re frightened by it.” Similarly, Tabitha said, “[Cancer is] difficult to talk about because people are terrified.” Elaine said, “[People are] afraid... They don’t know what to say so they don’t say anything.” Lindsay reported that at work, she “wasn’t even allowed to talk about my cancer, because it would upset my coworkers too much.” These repeated comments about participants finding that they could not be open about their experiences with cancer in many of their interactions indicate that they felt rejected and othered by others following their diagnosis.

In contrast to their interactions outside of the MCWC, participants reported that the MCWC is “open” (Taylor), “accepting” (Stephanie), and “comfortable” (Melanie, Dolores). For example, Melanie said, “I believe every cancer patient needs a place [like the MCWC] to feel comfortable.” Taylor said that at the MCWC clients can “just be open” about their cancer experiences. She also said that the staff, volunteers, and other clients let “you talk about anything you want to talk about” as opposed to people outside of the center, who may not be receptive to discussions about cancer. Topic avoidance and awkwardness is a common experience between people diagnosed with cancer and their family, friends, and coworkers, and these experiences can create distress. 3,22 However, having a place where they feel accepted can benefit people diagnosed with cancer by providing them with a place where they do not feel pitied, othered, or judged.

Validation of new identity

The third theme that emerged related to psychosocial benefits of social support experienced at the MCWC is that participants reported having their new identity postcancer diagnosis being validated at the center. Transformative experiences, such as cancer diagnoses, change individuals’ values and behaviors and have lasting effects on their lives.32 Participants in the present study often noted that they felt their identity had changed following their diagnosis. For example, Elaine said:

I think that’s a part of the cancer experience that people don’t expect or understand that might potentially come and I think that’s where [MCWC] helps out because there is that life beyond [cancer]. You just don’t turn it off and say, “Okay, I’m done with this [cancer] now.”... You have a different outlook. Your life is different.

Likewise, Lindsay said, “You do need [MCWC] because people forget [that you are different].” Nora explained that the center was helpful even after she completed treatment:

Once you get through your treatments and you get to a certain phase it’s like, “Okay. Now what? Where do I go, what do I do?” That’s where yoga has fulfilled that, that little void as to what’s the next step. When people say they’re cancer-free I have a hard time with that because I’m not quite sure we’re ever totally cancer-free.

Participants’ accounts suggest that the center validates their identity transformation and provides a safe space and encouraging interactions whereby participants’ experiences are welcomed, addressed, and valued. People diagnosed with cancer often report experiencing transformation.30,32 However, individuals’ new identities and experiences with cancer may not be validated or even acknowledged by others. Ellingson33 explains that even some non-profit cancer advocacy organizations (e.g., American Cancer Society and National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship) have advanced narratives (e.g., “waging a battle” and “return to normal”) that do not reflect individuals’ experiences following cancer treatment. As such, participants’ experiences of having their new identities validated at the MCWC demonstrates the positive impact that a cancer support organization can have for individuals struggling to have their experiences and feelings acknowledged following a cancer diagnosis.

Experiencing relaxation and stress relief

The final theme that emerged related to the psychosocial benefits participants experienced was that they were able to relax and experienced stress relief through their utilization of center services. Participants explicitly reported that they were able to “relax” (Maggie, Dolores, Alyssa, Taylor, Stephanie, Julia) and “release [stress]” (Sandra, Paige) after using integrative services (i.e., Reiki, facials, foot reflexology, and massage) and participating in MCWC activities (i.e., yoga, mindfulness workshop, and support groups). For example, Maggie said, “The Reiki helps me relax. I really needed the relaxation. [It] took away the anxiety.” Similarly, Vanessa explained that she “really enjoy[s]” yoga at the center because “it’s calming at the same it gives you a little bit of physical activity.”

People diagnosed with cancer commonly report increased stress.34 When individuals relax, their stress is reduced, and some of the physical manifestations of that stress may be ameliorated. As such, participants’ experiences with the services and programming explicitly designed to help them manage stress suggest that individuals directly benefit (i.e., direct effects model17) from their experiences at the center. Thus, experiences at the center that contribute to reducing participants’ stress can have potentially important health benefits (e.g., better pain management and psychological wellbeing).

Discussion

This study highlights the varied and valuable psychosocial health benefits that people diagnosed with cancer experienced through their utilization of services at a community-based cancer wellness organization. Specifically, the data revealed that the organization is a source of connection, acceptance, and validation in their lives that also provides them with services that leave them feeling relaxed and relieved of stress. Thus, the data from this study indicate that the organizational culture of the community- based cancer wellness organization shapes a supportive environment through which clients experience various psychosocial benefits. Specifically, Figure 1 illustrates the process through which the organizational culture at the MCWC shapes how organizational members, such as the staff and volunteers, interact with participants and, importantly, provide social support that results in various psychosocial benefits. Further, the process illustrated in the figure shows how the organizational culture can contribute to participants ascribing the psychosocial benefits they experience as occurring as a result of social support experienced through their collective experiences at the MCWC. That is, the participants attribute the support they receive and the associated psychosocial benefits to the organization itself rather than to interactions with supportive individuals alone. Thus, the study findings have both practical implications regarding the value of communitybased cancer wellness organizations to people diagnosed with cancer and theoretical implications regarding how alternative healthcare organizations can facilitate social support to people diagnosed with cancer.

Figure 1.

Supportive exchanges and psychosocial benefits experienced at a community-based cancer wellness organization.

Cancer treatment and survivorship present a variety of challenges for people living with cancer, and the findings of the present study indicate the benefits of communitybased cancer wellness organizations. Rosenbaum and Smallwood’s8,9 examinations of the experiences of people diagnosed with cancer at community-based cancer wellness organizations indicate that these organizations are often a place for people diagnosed with cancer to receive the emotional support needed to help them cope with their diagnosis. Similarly, the present study provides the precise psychological benefits of the social support and further recognizes the important role of the organization in creating an inviting space for people diagnosed with cancer to seek and receive this needed support. As such, the findings of this study have important implications in terms of the usefulness of these organizations to people diagnosed with cancer. These organizations may help fulfill support gaps that people diagnosed with cancer are experiencing and provide social support that meets their varied psychosocial needs in beneficial ways. Further, the present findings also demonstrate the value in the range of programming offered by this type of organization in contrast to literature that has examined the value of cancer support groups alone.10 That is, people diagnosed with cancer may need and/or desire an array of programming that cancer support groups single-handedly cannot offer.23 As such, community-based cancer wellness organizations may be able to provide an assortment of resources to meet the various social, emotional, and physical needs of people diagnosed with cancer.

Researchers have yet to fully consider the role of organizations and in particular, healthcare organizations in meeting the support needs of people diagnosed with cancer. Although social support is commonly examined through interpersonal exchanges (e.g., between spouses), social support is often communicated within organizations, especially in healthcare contexts (e.g., provider-patient). Zimmerman and Applegate28 noted that social support exchanged in organizational environments is subject to “the organizational and cultural environments in which the supportive talk is situated” (p. 59). Sass and Mattson35 similarly critiqued traditional definitions of social support and their application in organizational contexts, arguing that an organization’s culture can reify supportive norms. As such, social support provided within organizations does not occur in a vacuum and is likely influenced by organizational norms, structures, and practices. Norms and practices within organizations shape the culture of the organization and how organizational members behave. In the present study, participants noted how all staff members were “kind” and “caring” and how these supportive behaviors were thus demonstrated across their collective organizational interactions. As such, the findings of the present study are particularly applicable to the notion that organizations shape and even facilitate supportive communication processes through the sum of the interactions individuals experience across the organization. That is, the study participants repeatedly discussed how the center created an environment in which they felt connected to others, accepted, and validated. These accounts and the resulting thematic patterns from this study thus demonstrate the integral role of the community-based cancer wellness organization in not only providing supportive resources and services, but how the organization can function as a space that facilitates supportive communication resulting in specific psychosocial benefits to people diagnosed with cancer.

Study limitations and future directions

The present study examined the experiences of people diagnosed with cancer at a small community-based cancer wellness organization. Although the findings indicate the value of this particular organization to participants, more research is needed to understand the full extent of the value of social support experienced at community-based cancer wellness organizations. A limitation of the present study is that it only examined participants at one community- based cancer wellness organization. The MCWC may be unique in terms of its organizational culture and clients’ experiences with this organization. As such, clients’ experiences at multiple community-based cancer wellness organizations need to be observed to more fully capture the extent of psychosocial benefits that individuals receive through these centers.

A second limitation of this study is that it only examines client experiences. Further research may benefit from examining the experiences of employees, volunteers, and other organizational stakeholders (e.g., members of the board of directors) to identify the contributions of organizational members to a supportive culture. Additional attention to the mechanisms through which social support is communicated and, in particular, the role of organizational factors (e.g., norms, policies, and practices) would have practical significance from an organizational perspective by expanding scholars’ understanding of the relationship between macro-level organizational forces and micro-level interpersonal interactions.

Conclusions

The present study described the experiences of people diagnosed with cancer who regularly use a communitybased cancer wellness organization. The study findings suggest that people diagnosed with cancer who participate in programming at community-based cancer wellness organizations recognize the value that these organizations have in terms of supporting their cancer journey and recovery. Notably, the organization itself fosters an environment that is a source of connection, acceptance, validation, and stress relief to people diagnosed with cancer. The organization as a whole, in contrast to individuals encountered within the organization, holds the immense capacity of facilitating supportive interactions that result in various social, emotional, and physical health benefits.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: Cancer J Clin; 2020;70:7-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hair D, Kreps GL, Sparks L. Conceptualizing cancer care and communication. In: O’Hair D, Kreps GL, Sparks L, eds. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. 2007. pp 1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan-Kicken E, Caughlin JP. A multiple goals perspective on topic avoidance and relationship satisfaction in the context of breast cancer. Commun Monogr 2010;77:231–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunkel-Schetter C. Social support and cancer: Findings based on patient interviews and their implications. J Soc Issues 1984;40:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: Reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol 1996;15:135–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meluch AL. Spiritual support experienced at a cancer wellness center. South Commun J 2018;83:137-48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.About Us [Internet]. Cancersupportcommunity.org. Accessed 2021. Oct 18. Available from: https://www.cancersupportcommunity.org/about-us [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbaum MS, Smallwood JA. Cancer resource centres: Transformational services and restorative servicescapes. J Mark Manag 2011;27:1404–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum MS, Smallwood JA. Cancer resource centers as third places. J Serv Mark 2013;27:472–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb BH, Wachala ED. Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psychooncology 2007;16: 379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burleson BR, Albrecht TL, Goldsmith DJ, Sarason IG. Introduction: The communication of social support. In: Burleson BR, Albrecht TL, Goldsmith DJ, Sarason IG, eds. Communication of social support: Messages, interactions, relationships, and community. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp xi-xxx. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albrecht TL, Adelman MB. Communicating social support: A theoretical perspective. In: Albrecht TL, Adelman MB, eds. Communicating social support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1987. pp 18-39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albrecht TL, Goldsmith DJ. Social support, social networks, and health. In Thompson TL, Dorsey A, Miller KI, Parrott R, eds. Handbook of health communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp 263-84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGeorge EL, Feng B, Burleson BR. Supportive communication. In Knapp ML, Daly JA, eds. The SAGE handbook of interpersonal communication (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, Sage; 2011. pp 317-54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchino BN. Social support & physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull 1996;119:488–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985;98:310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodie GD, Burleson BR. Explaining variations in the effects of supportive messages: A dual-process framework. In: Beck C, ed. Communication yearbook 32 New York: Routledge; 2008. pp 354–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, et al. The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015;175:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav 2011;52:145–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan EE, LeBlanc Farris K. Interpersonal communication and coping with cancer: A multidisciplinary theoretical review of the literature. Commun Theory 2018;29:236–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caughlin JP, Mikucki-Enyart SL, Middleton AV, Stone AM, Brown LE. Being open without talking about it: A rhetorical/ normative approach to understanding topic avoidance in families after a lung cancer diagnosis. Commun Monogr 2011;78:409–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emslie C, Whyte F, Campbell A, et al. “I wouldn’t have been interested in just sitting round a table talking about cancer”; exploring the experiences of women with breast cancer in a group exercise trial. Health Educ Res 2007;22:827–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nvivo [Internet]. QSR International Pty Ltd. Accessed 2021. Oct 19. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman S, Applegate JL. Communicating social support in organizations. In Burleson BR, Albrecht TL, Sarason IG, eds. Communication of social support: Messages, interactions, relationships, and community. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp 50-69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 1983;5:168–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathieson CM, Stam HJ. Renegotiating identity: cancer narratives. Sociol Health Illn 1995;17:283–306. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park CL, Zlateva I, Blank TO. Self-identity after cancer: “survivor”, “victim”, “patient”, and “person with cancer.” J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:S430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thombre A, Rogers EM. The transformative experience of cancer survivors. In Wills M, ed. Communicating spirituality in health care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2009. pp 251-72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellingson LL. Realistically ever after: Disrupting dominant narratives of long-term cancer survivorship. Manage Commun Q 2017;31:321–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zabora JR, Blanchard CG, Smith ED, Roberts CS, Glajchcn M, Sharp JW, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. J Psychosoc Oncol 1997;15:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sass JS, Mattson M. When social support is uncomfortable: The communicative accomplishment of support as a cultural term in a youth intervention program. Manage Commun Q 1999;12:511–43. [Google Scholar]