ABSTRACT

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Despite recent advances in tissue immunology, little is known about the spatial distribution of tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets in lung tumors. Using high-parameter flow cytometry, we identified an accumulation of tissue-resident lymphocytes including tissue-resident NK (trNK) cells and CD8+ tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells toward the center of human non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC). Chemokine receptor expression patterns indicated different modes of tumor-infiltration and/or residency between trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells. In contrast to CD8+ TRM cells, trNK cells and ILCs generally expressed low levels of immune checkpoint receptors independent of location in the tumor. Additionally, granzyme expression in trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells was highest in the tumor center, and intratumoral CD49a+CD16− NK cells were functional and responded stronger to target cell stimulation than their CD49a− counterparts, indicating functional relevance of trNK cells in lung tumors.

In summary, the present spatial mapping of lymphocyte subsets in human NSCLC provides novel insights into the composition and functionality of tissue-resident immune cells, suggesting a role for trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells in lung tumors and their potential relevance for future therapeutic approaches.

KEYWORDS: CD8+ T cells, ILC, lung cancer, NK cells, tissue-resident, tumor-infiltrating

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death. Current immunotherapeutic approaches mainly focus on circulating T cells which infiltrate the tumor. However, little is known about the distribution of tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets such as tissue-resident NK (trNK) cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), and tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells within lung tumors.

TrNK and TRM cells, defined by co-expression of CD69, CD49a, and CD103, are readily identified in human lung1,2. ILCs which express high levels of CD69 are considered tissue-resident irrespective of CD49a or CD103 expression2–4. TrNK cells are characterized by a CD16− phenotype but differ markedly from conventional circulating CD16− NK cells both at the protein and transcriptome levels2. Frequencies of CD16− NK cells are increased in lung tumors5–7, suggesting that tumor-infiltrating NK cells are, at least in part, comprised of trNK cells. Additionally, a fraction of NK cells in human lung tumors have been reported to express immune checkpoint receptors, including PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIM-38,9, potentially inhibiting cytotoxic function of intratumoral NK cells.

In addition to NK cells and TRM cells, ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 have been identified in human lung tumors in several studies10,11. While ILC2s are reduced in frequency in lung tumor tissue compared to tumor-free lung tissue, NKp44+ ILC3s have been suggested to aid the formation of intratumoral lymphoid structures, indicating a relevance for ILC subsets within lung tumors10.

Compared to trNK cells and ILCs, CD8+ TRM cells have been studied in more detail in lung cancer. CD8+ TRM cells are more frequent in lung tumors compared to peritumoral lung tissue12, and their frequencies are associated with greater overall survival13,14. Intratumoral CD8+ TRM cells express inhibitory receptors, including CTLA-4, TIM-3, TIGIT, and CD39, which are largely confined to CD8+ TRM cells12–14. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells, strongly indicating a functional relevance for CD8+ TRM cells in the control of lung tumors14. To date, it remains unknown whether tissue-resident lymphocytes other than CD8+ TRM cells accumulate in human lung tumors and whether these cells share common traits with respect to expression of inhibitory receptors, chemokine receptors, and effector functions.

Here, we dissected the landscape of tissue-resident lymphocytes in patients with lung cancer in order to map common and distinct features of tissue-resident lymphocytes in human lung tumors. We show that trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells accumulated toward the center of non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC), associated with slightly overlapping yet distinct chemokine receptor expression patterns on trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells. In line with low expression of immune checkpoint receptors, trNK cells from the tumor center were responsive to ex vivo target cell stimulation.

Material and methods

Lung tissue collection

Thirty-seven patients undergoing lobectomy for suspected lung cancer were included, with patient-matched tumor tissues (peritumoral, margin, center) from 17 patients, non-matched tumor-distal tissue from 19 patients, and matched tumor-distal tissue from one patient. All tumor tissues were derived from NSCLC, while two additional tumor-distal tissues were derived from carcinoid tumors. Definition of the distinct tumor areas was controlled by pathologists. Patients with records of preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, strong immunosuppressive medication and/or hematological malignancy were excluded. Clinical and demographic details of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study (permit 2018/1819–31/1), and all donors gave informed written consent prior to sample collection.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographical details of the patients included in the study.

| Distal (n = 20) | Tumor (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female/male | 11/9 | 10/7 |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 71.7 ± 9.4 | 71 ± 8.8 |

| Smoker | 80% (16) | 94% (17) |

| Pathology | % (n) | % (n) |

| Adenocarcinoma (ADC) | 75% (15) | 60% (10) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) | 10% (2) | 40% (7) |

| Carcinoid | 10% (2) | 0% (0) |

| Other | 5% (1) | 0% (0) |

|

Tumor stage IA IB IIA IIB IIIA |

% (n) 45% (9) 20% (4) 0% (0) 10% (2) 15% (3) |

% (n) 11.7% (2) 35.3% (6) 11.8% (2) 23.5% (4) 17.6% (3) |

Processing of tissue specimens

Lung tissue was processed as previously described15. Briefly, macroscopically tumor-free human lung tissue, taken either as distal as possible from the tumor site (defined as ‘distal’), or from a site in close proximity (within 2.5 cm) to the tumor (defined as ‘peritumoral’), together with a part taken from the tumor margin and tumor center, were transferred into ice-cold PBS or Krebs-Henseleit buffer15 and stored at 4°C for maximal 18 h until processing. Tissue was digested using collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich) and DNase (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C. After digestion, RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS (Thermo Scientific), 1 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) (R10 medium) was added, and the cell suspension was passed through a 40-μm cell strainer and washed twice in R10 medium. Mononuclear cells from lung cell suspensions were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep, Axis Shield).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with antibodies against extracellular and intracellular proteins (Supplementary Table S1). Secondary stainings were performed using streptavidin BB630 (BD Biosciences), or streptavidin BV650 (Biolegend) and Live/Dead Aqua (Molecular probes, Life Technologies). After surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using a FoxP3/Transcription Factor staining kit (eBioscience). Samples were analyzed on a BD Symphony equipped with five lasers (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.7.1 (BD Biosciences).

Degranulation assay

NK cell degranulation was analyzed as previously described15. In brief, fresh lung mononuclear cells were resuspended in R10 medium and rested for 15–18 h at 37°C. Cells were cocultured with or without K562 cells for 6 h with anti-human CD107a (BV421, H4A3; BD Biosciences). Brefeldin A and monensin (GolgiPlug and GolgiStop, BD Biosciences) were added for the last 5 h of incubation.

Statistics

Statistics were analyzed in GraphPad Prism 9. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or Mann–Whitney test were used for matched or unmatched pairs of data, respectively, unless otherwise stated.

Results

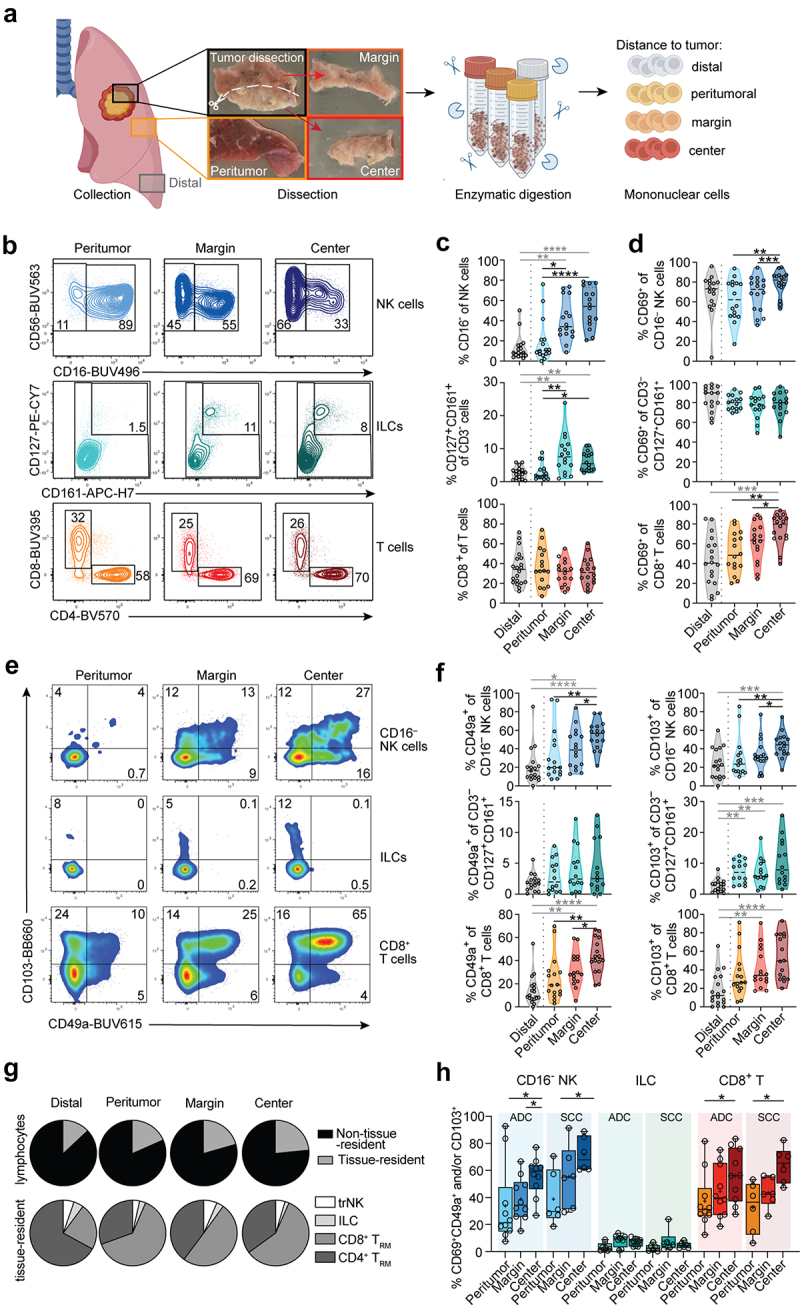

Tissue-resident NK cells and CD8+ TRM cells are enriched in human NSCLC tumors

First, we analyzed the landscape of CD16− NK cells, ILCs, and T cell subsets in tumor-free (distal), peritumoral, tumor margin, and tumor center tissues of human lung tumors (Figure 1a; gating strategies in Figure S1A-D). Frequencies of CD16− NK cells of total NK cells as well as of ILCs (defined as CD3−CD127+CD161+ cells) of total CD3− lymphocytes were higher toward the tumor center compared to peritumoral or distal tissue (Figure 1b, c). In contrast, frequencies of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells of total T cells were similar between the different tissue areas (Figure 1b, c, Figure S1B).

Figure 1.

Distribution of CD16− NK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ T cells in human lung tumors. (a) Graphical overview of workflow. Created with BioRender.com. (b) Representative contour plots and (c) summary of frequencies of CD16− NK cells, CD127+CD161+CD3− ILCs, and CD8+ T cells, respectively. (d) Frequencies of CD69+ cells among CD16− NK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ T cells in tumor-free and intratumoral tissues (n = 16–20) are shown. (e) Representative pseudocolor plots and (f) frequencies of CD49a and CD103 expression on CD16− NK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ T cells in tumor-free and tumor areas (n = 14–18). (g) Pie charts showing the composition of tissue-resident cells within the total lymphocyte (upper row) or tissue-resident (lower row) population (n = 15–17). (h) Frequencies of trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells co-expressing CD69, CD49a, and/or CD103 (n = 14–16). (c, d, f, h) Friedman test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (patient-matched, black); Kruskal–Wallis test (unmatched, gray). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Expression of CD69, a marker for tissue-resident lymphocytes, was more frequently expressed toward the tumor center on CD16− NK cells and CD8+ T cells and in a similar but non-significant trend on CD4+ T cells, while nearly all ILCs expressed CD69 at all locations studied (Figure 1d, Figure S1E, F). Next, we analyzed the distribution of cell subsets with additional features of tissue-residency, such as the expression of CD49a and CD103. Both CD16− NK cells and CD8+ T cells expressed CD49a and CD103 more frequently in the tumor center as compared to the tumor margin, peritumoral, and distal sites (Figure 1e, f). In contrast, CD4+ T cells expressed similar levels of CD49a and CD103 throughout all areas (Figure S1E, F). On ILCs, CD49a expression was generally low; however, CD103 expression was elevated in the tumor center as compared to tumor-free distal tissue (Figure 1e, f). In line with these results, tissue-resident lymphocytes were slightly more frequent in the tumor center (Figure 1g). Among the tissue-resident lymphocytes, CD8+ TRM cells comprised the predominant tissue-resident population in the tumor and peritumoral areas, while CD4+ TRM cells dominated in tumor-distal tissue (Figure 1g, Figure S1G), indicating proportional changes of the lymphocyte composition in tumor-free tissue in close proximity to the tumor. The stratification of data based on the NSCLC-tumor histotype, i.e. adenocarcinoma (ADC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), revealed comparable patterns of trNK cell and CD8+ TRM cell accumulation toward the tumor center, independent of tumor type specificity or cancer stage (Figure 1h, Figure S1H-J). Together, our results suggest an accumulation of tissue-resident lymphocytes, mainly constituted by CD8+ TRM cells, in the center of human NSCLC tumors.

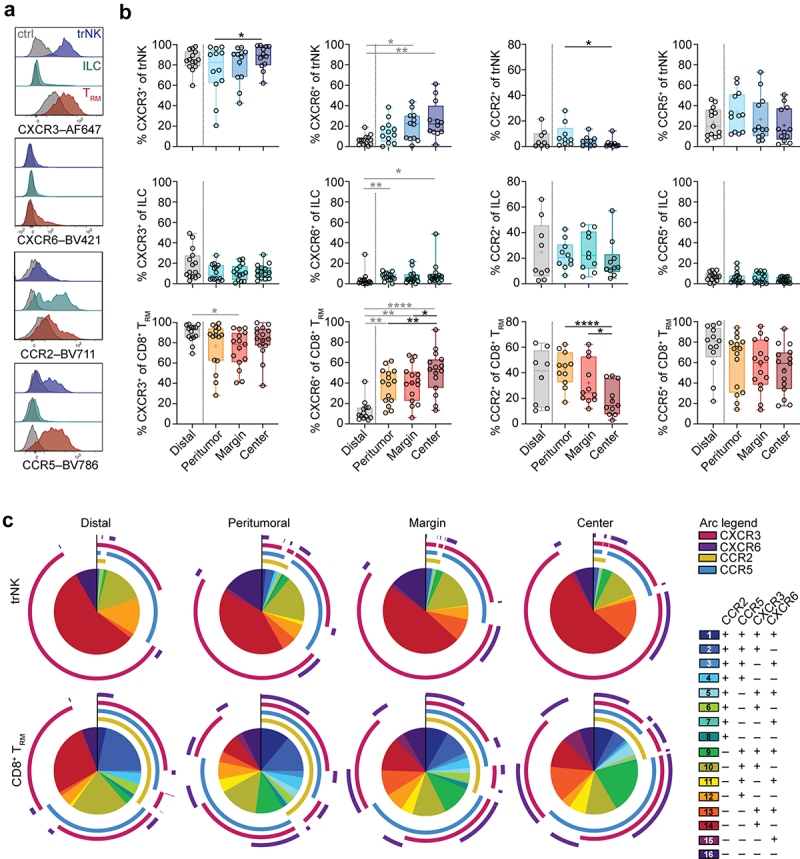

CXCR3+CXCR6+ trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells accumulate within the tumor center

The increase in trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells toward the tumor center suggested a selective recruitment or retention of these cells at this location. To identify whether tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets share common tumor-infiltration capacities, we analyzed the expression of chemokine receptors relevant for mediating recruitment of leukocytes to the tumor microenvironment16–18. Expression of CXCR3, CXCR6, CCR2, and CCR5 differed between trNK cells, ILCs, CD8+ TRM cells, and CD4+ TRM cells (Figure 2a, Figure S2A), as well as between locations within the tumor and tumor-distal lung tissue (Figure 2b). CXCR3 expression was high on trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells (Figure 2b, c) and did not differ between ADC and SCC (Figure S2B, C). Notably, the frequency of CXCR6+ trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells increased toward the tumor center (Figure 2b, c). However, this observation was specific to SCC and not observed in ADC (Figure S2B, C). Conversely, the proportion of trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells expressing CCR2 decreased (Figure 2b, c). This reduction was particularly noticeable on trNK cells derived from SCC, potentially attributable to their overall low expression. Nonetheless, it was evident in both cancer subtypes for CD8+ TRM cells (Figure S2B, C). CCR5 expression on trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells was similar at all locations (Figure 2b, c). Except for CCR2, chemokine receptor expression was low on ILCs, with no or only minor changes throughout all areas (Figure 2b, Figure S2B, C). Co-expression patterns of chemokine receptors were considerably more diverse on CD8+ TRM cells than on trNK cells (Figure 2c). Strong increases toward the tumor center were observed for CXCR3+CXCR6+ cells (population 13) and CCR5+CXCR3+CXCR6+ CD8+ TRM cells (population 9), concurrent with a decrease in CCR5 single-positive (population 12) as well as CCR2+CCR5+CXCR6+ (population 3) CD8+ TRM cells (Figure 2c). A large proportion of CXCR3+CXCR6+ CD8+ TRM cells but not trNK cells also co-expressed CCR5 (population 9), indicating a potential role for CCR5 specifically on CD8+ TRM cells. In contrast, CD8+ TRM cells expressing only CXCR3 (population 14) and co-expressing CXCR3, CCR2, and CCR5 (population 2) were largely confined to the distal non-tumor area (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Chemokine receptor expression on tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets in lung tumors. (a) Representative overlays of expression of CXCR3, CXCR6, CCR2, and CCR5 on trNK cells (blue), ILCs (green), and CD8+ TRM cells (red) from lung tumor center. Gray histograms represent FMO controls. (b) Frequencies of trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells expressing CXCR3, CXCR6, CCR2, or CCR5 in tumor-free tissue or tumor tissues (n = 8–16). Friedman test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (patient-matched, black); Kruskal–Wallis test (unmatched, gray). Mean indicated as ‘+’. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. (c) SPICE analysis of co-expression patterns of CXCR3, CXCR6, CCR2, and CCR5 on trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells in different tumor-free tissues and in tumor tissues (n = 6–8).

Altogether, although chemokine receptor co-expression patterns differed between trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells, increased CXCR6 expression on both cell types toward the tumor center indicate that CXCR6 constitutes a key-receptor for mediating the accumulation of trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells in lung tumors.

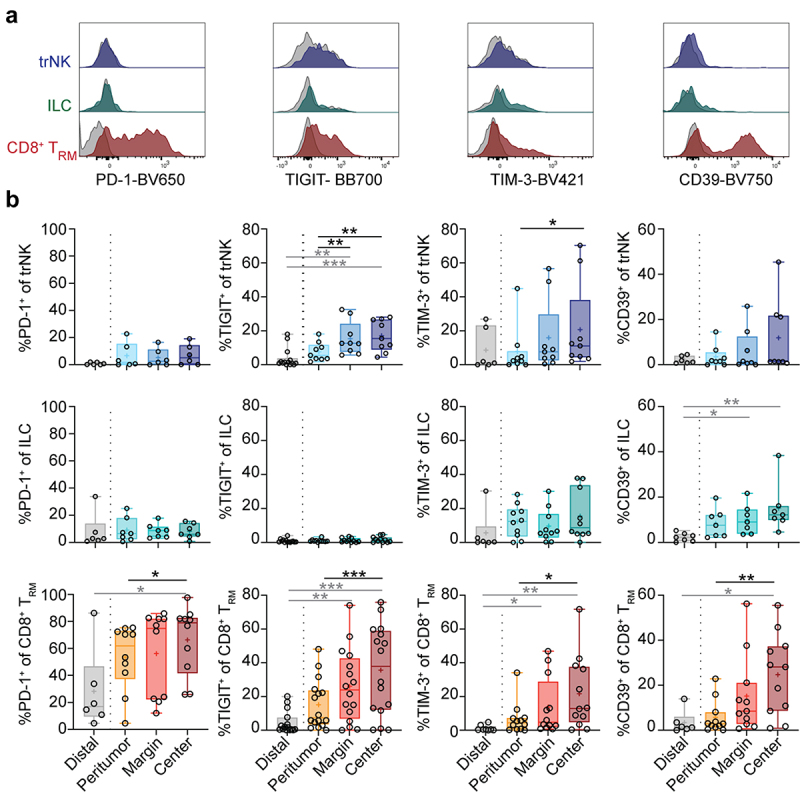

Immune checkpoint receptor expression increases on tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRM cells but not trNK cells or ILCs

Despite the capacity to infiltrate tumors, intratumoral NK cells and T cells have been suggested to be largely functionally inert19,20, in part resulting from upregulation of immune checkpoint receptors/exhaustion markers such as PD-121,22, TIM-323,24, TIGIT25, and CD3926,27. Since little is known about the expression of immune checkpoint receptors on tissue-resident innate lymphocytes, we assessed their expression on trNK cells, ILCs, CD8+ TRM, and CD4+ TRM cells in the distinct tumor locations (Figure 3a, b and Figure S3A). In most donors, immune checkpoint receptors were expressed by few trNK cells and ILCs at all locations, whereas CD8+ TRM cells displayed high immune checkpoint receptor expression in the tumor tissues (Figure 3a, b). Expression of TIGIT and TIM-3 on trNK cells, and all immune checkpoint receptors analyzed on CD8+ TRM and CD4+ TRM cells increased toward the tumor center (Figure 3b, Figure S3A). Although TIGIT was expressed by a higher frequency of trNK cells in the tumor center compared to peritumoral and distal tissue, expression remained considerably lower than that of CD8+ TRM cells at all locations (Figure 3b). In contrast to other immune checkpoint receptors, TIGIT was not expressed on ILCs (Figure 3b), which, however, more frequently expressed CD39 toward the tumor center (Figure 3b). Immune checkpoint receptor expression on trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells did not differ significantly between ADC and SCC (Figure S3B).

Figure 3.

Immune checkpoint receptor expression on tissue-resident lymphocytes in lung tumors. (a) Representative overlays of expression of PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3, and CD39 on trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells in the tumor center. Gray histograms represent FMO controls. (b) Frequencies of trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells expressing PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3, or CD39 in different tumor-free tissues or tumor tissues (n = 6–16). Friedman test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (patient-matched, black); Kruskal–Wallis test (unmatched, gray). Mean indicated as ‘+’. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Together, our data indicate that CD8+ TRM cells in lung tumors would be substantially more affected by common immune checkpoint therapies than trNK cells and ILCs.

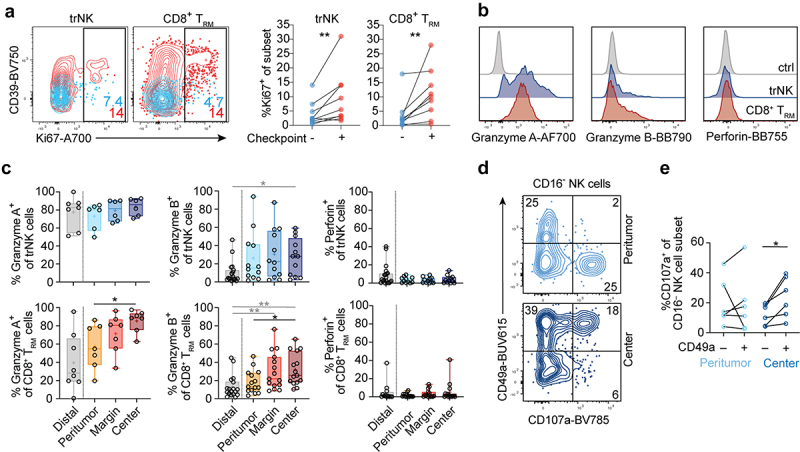

Different activation profiles of tumor-infiltrating tissue-resident lymphocytes

Low expression of immune checkpoint receptors on trNK cells led us to assess functional properties in comparison to CD8+ TRM cells (Figure 4). Immune checkpoint receptor-expressing trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells expressed more Ki67 compared to checkpoint receptor-negative cells (Figure 4a). Furthermore, the tumor center was enriched with trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells expressing granzymes (Figure 4b, c). While granzyme A expression did not differ between ADC and SCC, granzyme B expression was significantly higher on CD8+ TRM cells in SCC in the tumor center compared to the corresponding region in ADC (Figure S4A, B). However, both trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells lacked perforin expression (Figure 4b, c), which was consistent for both ADC and SCC (Figure S4A, B), despite it being readily detectable in CD16+ NK cells in all tumor areas (Figure S4C, D). As expected, ILCs and CD4+ TRM cells did not express any or very low levels of cytotoxic effector molecules (Figure S4A, B). In contrast to trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells, their non-tissue-resident counterparts (defined as CD49a−CD103−CD16− NK cells and CD49a−CD103−CD8+ T cells, respectively) expressed granzyme A and B less frequently in the tumor center (Figure S4C, D). These expression patterns suggest different cytotoxic capacities of tissue-resident and non-tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets toward the center of human lung tumors. Indeed, the analysis of target cell responsiveness revealed that CD49a+CD16− NK cells from the tumor center degranulated stronger than CD49a−CD16− NK cells (Figure 4d, e), suggesting the functional competence of trNK cells in the tumor center.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic profiles of trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells in lung tumors. (a) Representative contour plots (left) and summary data (right) of Ki67 expression on checkpoint receptor negative (blue) or positive (red) trNK and CD8+ TRM cells (n = 9). (b) Representative overlays (tumor center) and (c) summary of data showing frequencies of granzyme A, granzyme B, and perforin expression in trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells in different tumor and tumor-free tissue areas (n = 7–19). (d) Representative contour plots displaying degranulation in response to K562 target cells. CD16− NK cells from peritumoral tissue or tumor center were gated. (e) Frequencies of CD107a+CD49a−CD16− and CD107a+CD49a+CD16− NK cells following stimulation with K562 target cells. Data from unstimulated controls have been subtracted (n = 6). (c) Friedman test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (patient-matched, black); Kruskal–Wallis test (unmatched, gray). (a, e) Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Together, these results reveal different effector profiles of tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets depending on their location within lung tumors. While conventional intratumoral NK cell and T cell subsets are considered hypofunctional19,20, our results suggest that trNK cells are tumor target cell-responsive.

Discussion

Here, we studied the distribution and phenotypic traits of tissue-resident lymphocyte subsets across human lung tumors and in tumor-free lung tissue.

Human trNK cells have been described in tumor-free lung2, however, their distribution in lung tumors is largely unexplored. Our study revealed an accumulation of trNK cells, ILCs, and CD8+ TRM cells toward the center of human lung tumors, which may, in particular for trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells, be linked to chemokine receptors such as CXCR3 and CXCR6, which are relevant for NK cell and T cell infiltration into tumors28–30. Both CXCR3 and CXCR6 were expressed at highest frequencies on tumor center trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells, respectively. Additionally, our data suggest that the CCL5/CCR5 axis might play a role in tumor-infiltration of CD8+ TRM cells, in line with a strong correlation between the expression of CCL5 and CD8+ T cell infiltration across different types of cancer31. In addition to varying infiltration capacities, the observed phenotype could have been induced by the tumor-microenvironment or in response to other infiltrating leukocytes. For example, circulating NK cells co-cultured with a head and neck SCC cell line and IL-15 upregulated CD49a and CD103, indicating promotion of a tissue-residency phenotype via the tumor microenvironment32. Therefore, other mechanisms leading to the accumulation of specific cell subsets such as apoptosis, metabolic differences, and lineage-dependent development must be considered.

Despite functional exhaustion, upregulation of immune checkpoint receptors on CD8+ TRM cells and trNK cells, albeit at low frequencies, indicates an immune-activating environment33. Indeed, tumor-infiltrating CD103+ TRM cells are more functional and cytotoxic as compared to their CD103− counterparts (reviewed in34). Furthermore, the expression of both granzyme A and granzyme B was highest in trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells in the tumor center. Notably, granzyme B expression was significantly higher on CD8+ TRM cells in the tumor center in SCC compared to ADC.

Intratumoral CD49a+ NK cells were readily responsive to tumor target cells, in contrast to previous reports35. However, effector cell function in the tumor might be compromised due to lack of perforin expression in these cell subsets. It remains to be determined whether trNK cells can rapidly upregulate perforin upon stimulation as shown for CD8+ TRM cells in influenza infection1. Together with a low immune checkpoint receptor expression, this would make trNK cells a relevant alternative for future therapeutic applications in solid tumors. Manipulating the interaction of intratumoral chemokines with their cognate receptors on trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells might represent another suitable immunotherapeutic approach to modulate cell subset infiltration and retention (reviewed in36). Additionally, trNK and/or CD8+ TRM cells could be expanded and primed ex vivo and harnessed for targeted lysis of the tumor cells. Future analyses will determine whether trNK cells and CD8+ TRM cells can be directly or indirectly harnessed for optimization and development of novel treatment strategies for patients with solid tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the volunteers who participated in the study and S. Hylander as well as the Thoracic Surgery Unit at Karolinska University Hospital for administrative and clinical help. We would also like to acknowledge P. Clavero for his assistance in the laboratory.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (NM: #2021-03069, HGL: #2020-01365), the Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED, NM: #20200680, HGL: #2020-2022, JM: #20200725), the Swedish Cancer Society (NM: # 22 2319 Pj; HGL: #20 0975; JM: #20 1138, CAN 2017/663; FHdF: #19-0029), the Heart-Lung Foundation (JS: #20200659), the Magnus Bergvalls Foundation (NM: #2019-03168; JS: #2022), the Tornspiran Foundation (NM), the Åke Wibergs Foundation (JS), the Konsul Berghs Foundation (JS), Karolinska Institutet (NM), and Vinnova (HGL: #2020-2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study. All donors gave informed written consent prior to sample collection.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, NM, upon reasonable request.

Consent for publication

All authors are informed and consent to the publication of this data.

Authors- contributions

Conceptualization/study design: D.B., J.M., N.M.; Investigation: D.B., A.v.K., G.V., N.W., E.Y., J.M., N.M.; Resources: J.M., N.M., J.S., E.A., H.G.L., I.S., O.A., F.HdF.; Writing – original draft: D.B., G.V., N.W., J.M., N.M.; Writing – review and editing: D.B., N.W., E.A., O.A., H.G.L., J.M., N.M.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2023.2233402

References

- 1.Piet B, de BG, Smids-Dierdorp BS, van Dervan der LC, Remmerswaal EBM, von der TJ, van HJ, Eerenberg JP, ten BA, van Dervan der BW, et al. CD8+ T cells with an intraepithelial phenotype upregulate cytotoxic function upon influenza infection in human lung. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2254–9. doi: 10.1172/jci44675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marquardt N, Kekäläinen E, Chen P, Lourda M, Wilson JN, Scharenberg M, Bergman P, Al-Ameri M, Hård J, Mold JE, et al. Unique transcriptional and protein-expression signature in human lung tissue-resident NK cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3841. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11632-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasteiger G, Fan X, Dikiy S, Lee SY, Rudensky AY.. Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Science. 2015;350(6263):981–985. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meininger I, Carrasco A, Rao A, Soini T, Kokkinou E, Mjösberg J. Tissue-specific features of innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2020;41(10):902–917. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrega P, Morandi B, Costa R, Frumento G, Forte G, Altavilla G, Ratto GB, Mingari MC, Moretta L, Ferlazzo G. Natural killer cells infiltrating human nonsmall-cell lung cancer are enriched in CD56 bright CD16(-) cells and display an impaired capability to kill tumor cells. Cancer. 2008;112(4):863–875. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platonova S, Cherfils-Vicini J, Damotte D, Crozet L, Vieillard V, Validire P, André P, Dieu-Nosjean M-C, Alifano M, Régnard J-F, et al. Profound coordinated alterations of intratumoral NK cell phenotype and function in lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71(16):5412–5422. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-10-4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavin Y, Kobayashi S, Leader A, Amir ED, Elefant N, Bigenwald C, Remark R, Sweeney R, Becker CD, Levine JH, et al. Innate immune landscape in early lung adenocarcinoma by paired single-cell analyses. Cell. 2017;169(4):750–765.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russick J, Joubert P-E, Gillard-Bocquet M, Torset C, Meylan M, Petitprez F, Dragon-Durey M-A, Marmier S, Varthaman A, Josseaume N, et al. Natural killer cells in the human lung tumor microenvironment display immune inhibitory functions. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001054. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trefny MP, Kaiser M, Stanczak MA, Herzig P, Savic S, Wiese M, Lardinois D, Läubli H, Uhlenbrock F, Zippelius A. PD-1+ natural killer cells in human non-small cell lung cancer can be activated by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(8):1505–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02558-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrega P, Loiacono F, Carlo ED, Scaramuccia A, Mora M, Conte R, Benelli R, Spaggiari GM, Cantoni C, Campana S, et al. NCR+ILC3 concentrate in human lung cancer and associate with intratumoral lymphoid structures. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):8280. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh J, Kim HY, Lee Y, Park IK, Kang CH, Kim YT, Kim J-E, Choi M, Lee W-W, Jeon YK, et al. IL23-producing human lung cancer cells promote tumor growth via conversion of innate lymphoid cell 1 (ILC1) into ILC3. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(13):4026–4037. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floc’h AL, Jalil A, Vergnon I, Chansac BLM, Lazar V, Bismuth G, Chouaib S, Mami-Chouaib F. Alpha E beta 7 integrin interaction with E-cadherin promotes antitumor CTL activity by triggering lytic granule polarization and exocytosis. J Exp Medicine. 2007;204(3):559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganesan A-P, Clarke J, Wood O, Garrido-Martin EM, Chee SJ, Mellows T, Samaniego-Castruita D, Singh D, Seumois G, Alzetani A, et al. Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(8):940–950. doi: 10.1038/ni.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duhen T, Duhen R, Montler R, Moses J, Moudgil T, de MN, Goodall CP, Blair TC, Fox BA, McDermott JE, et al. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8 T cells in human solid tumors. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2724. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquardt N, Kekäläinen E, Chen P, Kvedaraite E, Wilson JN, Ivarsson MA, Mjösberg J, Berglin L, Säfholm J, Manson ML, et al. Human lung natural killer cells are predominantly comprised of highly differentiated hypofunctional CD69 − CD56 dim cells. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2017;139(4):1321–1330.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arenberg DA, Keane MP, DiGiovine B, Kunkel SL, Strom SRB, Burdick MD, Iannettoni MD, Strieter RM. Macrophage infiltration in human non-small-cell lung cancer: the role of CC chemokines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;49(2):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s002620050603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu W, Liu Y, Zhou W, Si L, Ren L, Kalinichenko VV. CXCL16 and CXCR6 are coexpressed in human lung cancer in vivo and mediate the invasion of lung cancer cell lines in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House IG, Savas P, Lai J, Chen AXY, Oliver AJ, Teo ZL, Todd KL, Henderson MA, Giuffrida L, Petley EV, et al. Macrophage-derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 are required for antitumor immune responses following immune checkpoint blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(2):487–504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melaiu O, Lucarini V, Cifaldi L, Fruci D. Influence of the tumor microenvironment on NK cell function in solid tumors. Front Immunol. 2020;10:3038. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Liu S, Zhang B, Qiao L, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. T cell dysfunction and exhaustion in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:17. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu C, Li M, Zhu S, Chen Y, Zhou L, Xu D, Xu J, Li Z, Li W, Cui J. PD-1-positive natural killer cells have a weaker antitumor function than that of PD-1-negative natural killer cells in lung cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(13):1964–1973. doi: 10.7150/ijms.47701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waldman AD, Fritz JM, Lenardo MJ. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(11):651–668. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao Y, Wang X, Jin T, Tian Y, Dai C, Widarma C, Song R, Xu F. Immune checkpoint molecules in natural killer cells as potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):250. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson AC, Joller N, Lag-3 KV. Tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity. 2016;44(5):989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauvin J-M, Zarour HM. TIGIT in cancer immunotherapy. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000957. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timperi E, Barnaba V. CD39 regulation and functions in T cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8068. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allard D, Allard B, Stagg J. On the mechanism of anti-CD39 immune checkpoint therapy. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000186. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendel M, Galani IE, Suri-Payer E, Cerwenka A. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN-γ and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8437–8445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillard-Bocquet M, Caer C, Cagnard N, Crozet L, Perez M, Fridman WH, Sautès-Fridman C, Cremer I. Lung tumor microenvironment induces specific gene expression signature in intratumoral NK cells. Front Immunol. 2013;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilato MD, Kfuri-Rubens R, Pruessmann JN, Ozga AJ, Messemaker M, Cadilha BL, Sivakumar R, Cianciaruso C, Warner RD, Marangoni F, et al. CXCR6 positions cytotoxic T cells to receive critical survival signals in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2021;184(17):4512–4530.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dangaj D, Bruand M, Grimm AJ, Ronet C, Barras D, Duttagupta PA, Lanitis E, Duraiswamy J, Tanyi JL, Benencia F, et al. Cooperation between constitutive and inducible chemokines enables T cell engraftment and immune attack in solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(6):885–900.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreno-Nieves UY, Tay JK, Saumyaa S, Horowitz NB, Shin JH, Mohammad IA, Luca B, Mundy DC, Gulati GS, Bedi N, et al. Landscape of innate lymphoid cells in human head and neck cancer reveals divergent NK cell states in the tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(28):e2101169118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101169118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Y, Li Y, Zhu B. T-cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Death Disease. 2015;6(6):e1792. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okła K, Farber DL, Zou W. Tissue-resident memory T cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2021;218(4):e20201605. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul S, Kulkarni N, Shilpi, Lal G. Intratumoral natural killer cells show reduced effector and cytolytic properties and control the differentiation of effector Th1 cells. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(12):e1235106. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2016.1235106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Märkl F, Huynh D, Endres S, Kobold S. Utilizing chemokines in cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(8):670–682. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, NM, upon reasonable request.