Abstract

Hypocretins/Orexins (Hcrt/Ox) are hypothalamic neuropeptides implicated in diverse functions, including body temperature regulation through modulation of sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone. In the current study, we measured subcutaneous (Tsc) and core (Tb) body temperature as well as activity in a conditional transgenic mouse strain that allows the inducible ablation of Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons by removal of doxycycline (DOX) from their diet (orexin-DTA mice). Measurements were made during a baseline, when mice were being maintained on food containing DOX, and over 42 days while the mice were fed normal chow which resulted in Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration. The home cages of the orexin-DTA mice were equipped with running wheels that were either locked or unlocked. In the presence of a locked running wheel, Tsc progressively decreased on days 28 and 42 in the DOX(−) condition, primarily during the dark phase (the major active period for rodents). This nocturnal reduction in Tsc was mitigated when mice had access to unlocked running wheels. In contrast to Tsc, Tb was largely maintained until day 42 in the DOX(−) condition even when the running wheel was locked. Acute changes in both Tsc and Tb were observed preceding, during, and following cataplexy. Our results suggest that ablation of Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons results in elevated heat loss, likely through reduced sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone, and that exercise may have some therapeutic benefit to patients with narcolepsy, a disorder caused by Hcrt/Ox deficiency. Acute changes in body temperature may facilitate prediction of cataplexy onset and lead to interventions to mitigate its occurrence.

Keywords: Hypocretin, Orexin, narcolepsy, body temperature, activity, thermogenesis, sympathetic vasoconstriction

1. Introduction

Hypocretins/Orexins (Hcrt/Ox) are hypothalamic neuropeptides implicated in diverse processes including sleep/wake control, addiction, the stress response through modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, as well as autonomic and body temperature regulation [1]. The two neuropeptides, hypocretin 1/orexin-A (Hcrt 1/Ox-A) and hypocretin 2/orexin-B (Hcrt 2/Ox-B), are both cleaved from the prepro-hypocretin/prepro-orexin protein, and have differential affinities for the Hypocretin 1/Orexin 1 (HcrtR1/OxR1) and Hypocretin 2/Orexin 2 receptors (HcrtR2/OxR2) [1, 2]. Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons project broadly and HcrtR/OxRs are distributed widely in the brain, thereby enabling this diverse functionality [3–7].

1.1. The role of Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons in body temperature and autonomic regulation

The link between the Hcrt/Ox system and metabolism was unequivocally established by the description of the orexin/ataxin-3 mouse. In this strain in which Hcrt/Ox neurons are ablated through selective expression of the Ataxin-3 protein in Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons, mice become obese as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate [8]. However, this seminal paper did not describe effects of Hcrt/Ox neuron loss on body temperature regulation. Nonetheless, several lines of evidence have suggested a role for the Hcrt/Ox system in thermoregulation. For example, intracerebroventricular (ICV) administration of Hcrt1/Ox-A increased thermogenesis, leading to an elevation in body temperature in Sprague-Dawley rats [9]. Oral administration of a dual orexin receptor antagonist resulted in reduced spontaneous locomotion for 8 hours and reduced core body temperature (Tb) for 4 hours in Wistar rats [10]. Cold exposure increased Hcrt/Ox mRNA expression in the hypothalamus in Wistar rats [11]. Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons innervate neurons in the caudal raphe that project to medullary sympathetic premotor neurons that control brown adipose tissue (BAT) sympathetic outflow and thermogenesis [12–14]. In rats, intrathecal administration of Hcrt1/Ox-A increases sympathetic outflow [15]. Furthermore, local Hcrt1/Ox-A injection into the rostral raphe pallidus in rats induced prolonged and pronounced increases in BAT sympathetic outflow and thermogenesis [16]. Together, these studies are suggestive of a role for Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission in maintenance of body temperature through modulation of BAT sympathetic tone.

Because of the impact of the Hcrt/Ox system on a broad range of physiological functions including arousal state control, the precise role of this system in other autonomic processes has been difficult to elucidate [17]. Transgenic mice in which Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission (Hcrt/Ox-KO mice) is eliminated exhibit more frequent occurrence of central apneas during sleep and a reduction in CO2 response during wakefulness [18–20]. Furthermore, the ventilatory long term facilitation response is absent during both sleep and wake in Hcrt/Ox-KO mice [21]. Hcrt/Ox-KO mice and orexin/ataxin-3 mice exhibit a basal blood pressure that is 20 mm Hg lower than their wildtype (WT) littermates [22–25]. Pharmacological blockade of sympathetic outflow lowered blood pressure in WT littermates and reduced basal blood pressure to levels similar to that found in Hcrt/Ox-KO mice [24]. The same pharmacological intervention had no effect in Hcrt/OX-KO mice, again suggesting reduced sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone as a result of the absence of the Hcrt/Ox neuropeptides, thus suggesting a causal role for impaired sympathetic tone in the reduction in basal blood pressure in the Hcrt/Ox-KO mice [24]. This role for the Hcrt/Ox system in maintenance of sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone thus has impacts on other autonomic processes such as modulation of cardiorespiratory function in addition to body temperature regulation.

1.2. Narcolepsy, a disorder caused by reduced or absent Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission: Metabolic dysfunction and body temperature changes

Narcolepsy is a sleep disorder resulting from loss of Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons [26, 27], likely through an immune-mediated mechanism [28, 29]. The most prominent symptoms in Narcolepsy are related to sleep/wake and are a result of the loss of Hcrt/Ox input to wake-promoting regions such as the cholinergic basal forebrain and brainstem monoaminergic neurons, resulting in reduced arousal state boundary control [29–31]. Patients with narcolepsy exhibit various sleep abnormalities including disrupted nocturnal sleep, sleep onset rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness and cataplexy in Narcolepsy Type 1 (NT1) patients. People with NT1 also exhibit metabolic symptoms: they are more likely to be obese, are often hypophagic, and have a lower basal metabolic rate than body mass index-matched controls [32, 33]. Patients with NT1 also display elevated plasma levels of GLP-1, suggestive of autonomic dysfunction [34].

Alterations in body temperature have also been described in patients with narcolepsy [35–37]. Increased skin temperature is associated with higher sleep propensity in NT1 [35]. An elevated dorsal-proximal skin temperature gradient (DPG) caused by elevated distal and reduced proximal skin temperatures during wakefulness is correlated positively with shorter sleep latency during the Multiple Sleep Latency Test. During normal sleep, distal temperature remained elevated, while proximal skin temperature was similar to healthy individuals [35]. Altered DPG in patients with narcolepsy is suggestive of a decreased sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone. Hcrt/Ox-deficient patients with narcolepsy also exhibit a reduced heart rate response to arousal compared to healthy controls, lending further support to the concept of reduced BAT outflow occurring as a result of Hcrt/Ox deficiency [38]. This concept is further supported by the animal studies discussed in section 1.1 which demonstrate that HcrtR1/OxR1 agonism increases sympathetic outflow, suggesting that loss of Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission as occurs in narcolepsy would therefore result in decreased sympathetic output [15, 16].

In the current study, we utilized bigenic orexin-tTA; TetO-DTA mice, a strain in which ablation of Hcrt/Ox neurons can be induced through dietary manipulation [39]. Subcutaneous (Tsc) and core (Tb) body temperature were recorded in intact mice and over the course of a 42 days period as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerated. Since access to a running wheel has been reported to exacerbate cataplexy in orexin ligand knockout mice [40], we also investigated how running wheel availability and the consequent opportunity for exercise affected activity and body temperature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Male “orexin-DTA mice” used for electroencephalogram (EEG)/electromyogram (EMG) experiments were the double transgenic offspring of orexin/tTA mice (C57BL/6-Tg(hOX-tTA)1Ahky), which express the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) exclusively in Hcrt/Ox neurons [39], and B6.Cg-Tg(tetO-DTA)1Gfi/J mice (JAX #008468), which express a diphtheria toxin A (DTA) fragment in the absence of dietary doxycycline. Both parental strains were from a C57BL/6J genetic background. Parental strains and offspring used for EEG/EMG recordings were maintained on a diet (Envigo T-7012, 200 Doxycycline) containing doxycycline (DOX(+) condition) to repress transgene expression until neurodegeneration was desired. To initiate neurodegeneration, orexin-DTA mice were switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) at 15±1 weeks of age to induce expression of the DTA transgene specifically in the Hcrt/Ox neurons [39]. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at SRI International and were conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Surgical Procedures

Male orexin-DTA mice (n = 31) were 11±1 weeks (23 ± 2 g) at the time of surgery. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction: 3–5% isoflurane in oxygen delivered at 1 L/min; maintenance: 1–2 % isoflurane in oxygen delivered at 1 L/min) and sterile telemetry transmitters (HD-X02, DSI, St Paul, MN) were placed in a blunt-dissected subcutaneous pocket located on the left dorsum (n = 26) for measurement of subcutaneous body temperature (Tsc), or inserted intraperitoneally at the midline (n = 5) for measurement of core body temperature (Tb). Biopotential leads were routed subcutaneously to the head, and both EMG leads were positioned through the right nuchal muscles. Cranial holes were drilled through the skull at −2.0 mm AP from bregma and 2.0 mm ML and on the midline at −1 mm AP from lambda. The two biopotential leads used as EEG electrodes were inserted into these holes and affixed to the skull with dental acrylic. The incision was closed with absorbable suture. Analgesia was managed with meloxicam (5 mg/kg, s.c.) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, s.c.) upon emergence from anesthesia and for the first day post-surgery. Meloxicam (5 mg/kg, s.c., q.d.) was continued for 2 d post-surgery. Mice were monitored daily for 14 days post-surgery; any remaining suture material was removed at that time.

2.3. EEG, EMG, Tsc, Tb and gross motor activity recording

Prior to data collection, orexin-DTA mice were allowed at least 2 weeks post-surgical recovery and at least 2 weeks adaptation to running wheels and handling procedures. Mice were housed individually in home cages equipped with running wheels and had ad libitum access to food, water and nestlets. Room temperature (22 ± 2°C), humidity (50 ± 20% relative humidity), and lighting conditions (LD12:12; Lights on at 7 am and off at 7 pm) were monitored continuously. Animals were inspected and room temperature and humidity measured and documented daily in accordance with AAALAC and SRI guidelines. EEG, EMG, Tsc, Tb and gross motor activity (GMA) were recorded via telemetry using Ponemah (DSI, St Paul, MN). EEG and EMG were sampled at 500 Hz. Digital videos were recorded with cameras placed lateral to each cage at 10 frames per second, 4CIF de-interlacing resolution.

2.3.1. Cataplexy Scoring

For all recordings, infrared video cameras were placed lateral to the cage and optimized to enable characterization of cataplexy (e.g., posture, position in cage relative to the nest, and eye state). EEG and EMG data were assessed by expert scorers to classify recording epochs of 10-s duration as cataplexy using NeuroScore (DSI, St. Paul, MN). Criteria for cataplexy were >40 s of EMG atonia, theta-dominated EEG, and behavioral immobility confirmed through video preceded by ≥ 40 s of wakefulness, following consensus criteria of the International Working Group on Rodent Models of Narcolepsy [41].

2.4. Experimental Design

Two weeks after adaptation to running wheels, DTA mice were divided into 5 experimental groups (Table 1):

Table 1.

Description of experimental groups

Group 1:

Orexin-DTA mice implanted with telemetry transmitters subcutaneously to measure Tsc and maintained on DOX(+) diet for 42 days in cages with running wheels locked (n = 5);

Group 2:

Orexin-DTA mice implanted with telemetry transmitters subcutaneously to measure Tsc and maintained on normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days in cages with running wheels locked (n = 5);

Group 3:

Orexin-DTA mice implanted with telemetry transmitters subcutaneously to measure Tsc and maintained on normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days in cages with running wheels unlocked (n = 7);

Group 4:

Orexin-DTA mice implanted with telemetry transmitters abdominally to measure Tb and maintained on normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days in cages with running wheels unlocked (n = 5). Due to poor quality EEG signals that precluded accurate determination of cataplexy in two mice, data from these mice were excluded from analysis of acute Tb changes in conjunction with cataplexy.

Group 5:

Orexin-DTA mice implanted with telemetry transmitters subcutaneously to measure Tsc and maintained on DOX(−) chow for 42 days. Following this DOX(−) period, initially mice were provided a locked running wheel cage, then after a 24 hour baseline recording beginning at ZT12 on day 0, the running wheels were unlocked at ZT12 on the following day and 24 h recordings were made on days 1, 2, 7, and 14 after unlocking the running wheels (n = 9).

For Groups 2–5, DOX(+) chow was reintroduced after 42 days to minimize further Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration. For EEG, EMG, Tsc, Tb and GMA recordings, individuals in each experimental group were recorded simultaneously, while the different experimental groups were recorded serially. Cataplexy bouts with a minimum duration of 50 sec were included in the analysis of acute changes in Tsc and Tb in relation to cataplexy occurrence.

3. Results

3.1. Subcutaneous body temperature (Tsc) and gross motor activity decline as the Hypocretin/Orexin neurons degenerate

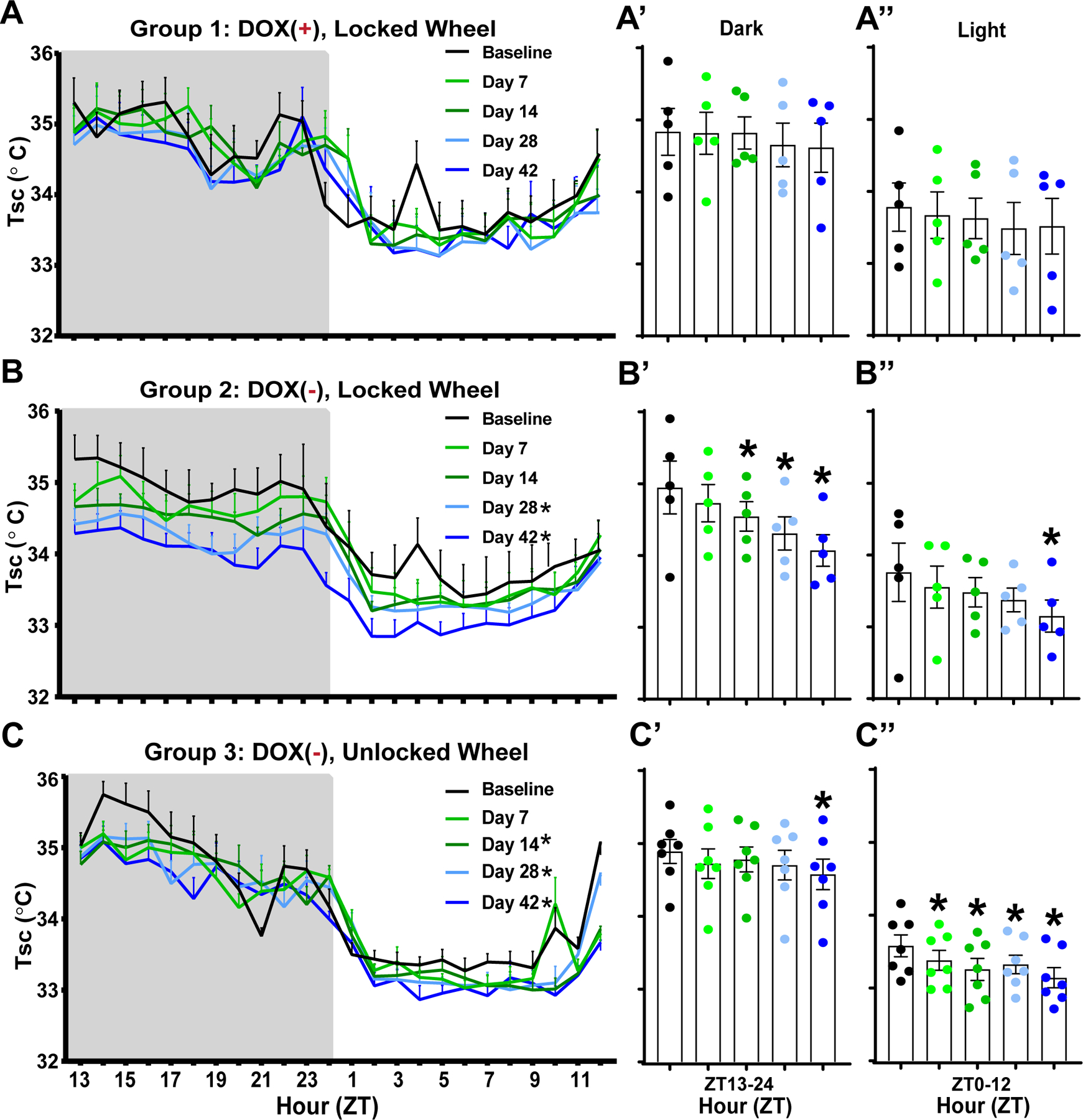

Group 1 mice were maintained on the DOX(+) diet, resulting in suppression of transgene expression and, consequently, the Hcrt/Ox neurons should have remained intact. Thus, this group served as experimental controls and neither subcutaneous body temperature (Tsc; Figs. 1A, A’, and A’’) nor GMA (Figs. 2A, A’, and A’’) varied significantly from baseline over the 42 d observation period.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Hypocretin/Orexin neuron degeneration and access to a running wheel on subcutaneous body temperature (Tsc) in male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice. (A) Hourly Tsc across the 24-h period in Group 1 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 5) maintained on doxycycline (DOX(+)) with a locked running wheel in their home cage. Recordings were made during a baseline and 7, 14, 28, and 42 days later. (A’, A”) Mean Tsc over the 42 days period for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, for the mice recorded in A. (B) Hourly Tsc across the 24-h period in Group 2 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 5) that were maintained with a locked running wheel in their home cage. Mice were on DOX chow during baseline but then switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days, during which time the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate. (B’, B”) Mean Tsc for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, during the 42-day degeneration period. (C) Hourly Tsc across the 24-h period in Group 3 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 7) that were maintained with an unlocked running wheel in their home cage. Mice were on DOX chow during baseline but then switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days, during which time the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate. (C’, C’’) Mean Tsc for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, during the 42-day degeneration period. Values are mean ± SEM. * in the legend and above the vertical bars indicates a significant difference during that day relative to baseline as determined by ANOVA. * p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Hypocretin/Orexin neuron degeneration and access to a running wheel on GMA in male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice. (A) Hourly GMA across the 24-h period in Group 1 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 5) maintained on doxycycline (DOX(+)) with a locked running wheel in their home cage. Recordings were made during a baseline and 7, 14, 28, and 42 days later. (A’, A”) Mean GMA over the 42-day period for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, for the mice recorded in A. (B) Hourly GMA across the 24-h period in Group 2 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 5) that were maintained with a locked running wheel in their home cage. Mice were on DOX chow during baseline and then switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days, during which time the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate. (B’, B”) Mean GMA for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, during the 42-day degeneration period. (C) Hourly GMA across the 24-h period in Group 3 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice (n = 7) that were maintained with an unlocked running wheel in their home cage. Mice were on DOX chow during baseline and then switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) for 42 days, during which time the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate. (C’, C’’) Mean GMA for the 12-h dark and light phases, respectively, during the 42-day degeneration period. Values are mean ± SEM. * in the legend and above the vertical bars indicates a significant difference during that day relative to baseline as determined by ANOVA. * p < 0.05.

In contrast, when Group 2 mice were switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) after a baseline recording, Tsc decreased progressively over the course of Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration during both the dark and light phases (Figs. 1B, B’, B’’). In comparison to the pre-degeneration baseline, RM-ANOVA revealed a significant condition effect for Tsc (F(4, 16) = 6.467, p = 0.0027). Dunnett’s post hoc tests indicate that Tsc was significantly reduced at days 28 (p = 0.0171) and 42 (p = 0.0009) after DOX removal. Fig. 1B’ shows that this reduction was most pronounced in the dark period on days 14 (p = 0.0235), 28 (p = 0.0006), and 42 (p < 0.0001), as well as during the light period on day 42 (p = 0.0196) (Fig. 1B’’). A condition effect was also significant for GMA (F(4, 16) = 5.998, p = 0.0038). GMA (Fig. 2B) progressively decreased at days 14 (p = 0.0378), 28 (p = 0.0026), and 42 (p = 0.0029). Figure 2B’ shows that this effect was primarily mediated by a reduction in GMA during the dark period on days 14 (p = 0.01), 28 (p = 0.0012), and 42 (p = 0.0005); activity didn’t vary significantly from baseline during the light period (Fig. 2B’’).

3.2. Access to a running wheel mitigates the decline in Tsc in the dark phase as Hypocretin/Orexin (Hcrt/Ox) neurons degenerate

In contrast to Groups 1 and 2, Group 3 mice had free access to a running wheel and their Hcrt/Ox neurons were degenerated by removal of dietary DOX as in Group 2 (Table 1). There was a significant condition effect on Tsc in Group 3 (F(4, 24) = 7.128, p = 0.0006). Similar to Group 2, Tsc was progressively reduced at days 14 (p = 0.0192), 28 (p = 0.0165), and 42 (p < 0.0001) post-DOX removal (Fig. 1C). In contrast to Group 2, this reduction was only significant during the dark period at day 42 (p = 0.0147; Fig. 1C’) but Tsc was significantly reduced during the light period at all post-DOX removal weeks in comparison to baseline (Day 7: p = 0.0226, Day 14: p = 0.0003, Day 28: p = 0.0031, Day 42: p < 0.0001; Fig. 1C’’).

In contrast to Group 2 which experienced a reduction in GMA as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate (Figs. 2B, 2B’ and 2B”), Group 3 mice had similar activity levels across all recording conditions (Fig. 2C), during both the dark (Fig. 2C’) and the light (Fig. 2C”) phases.

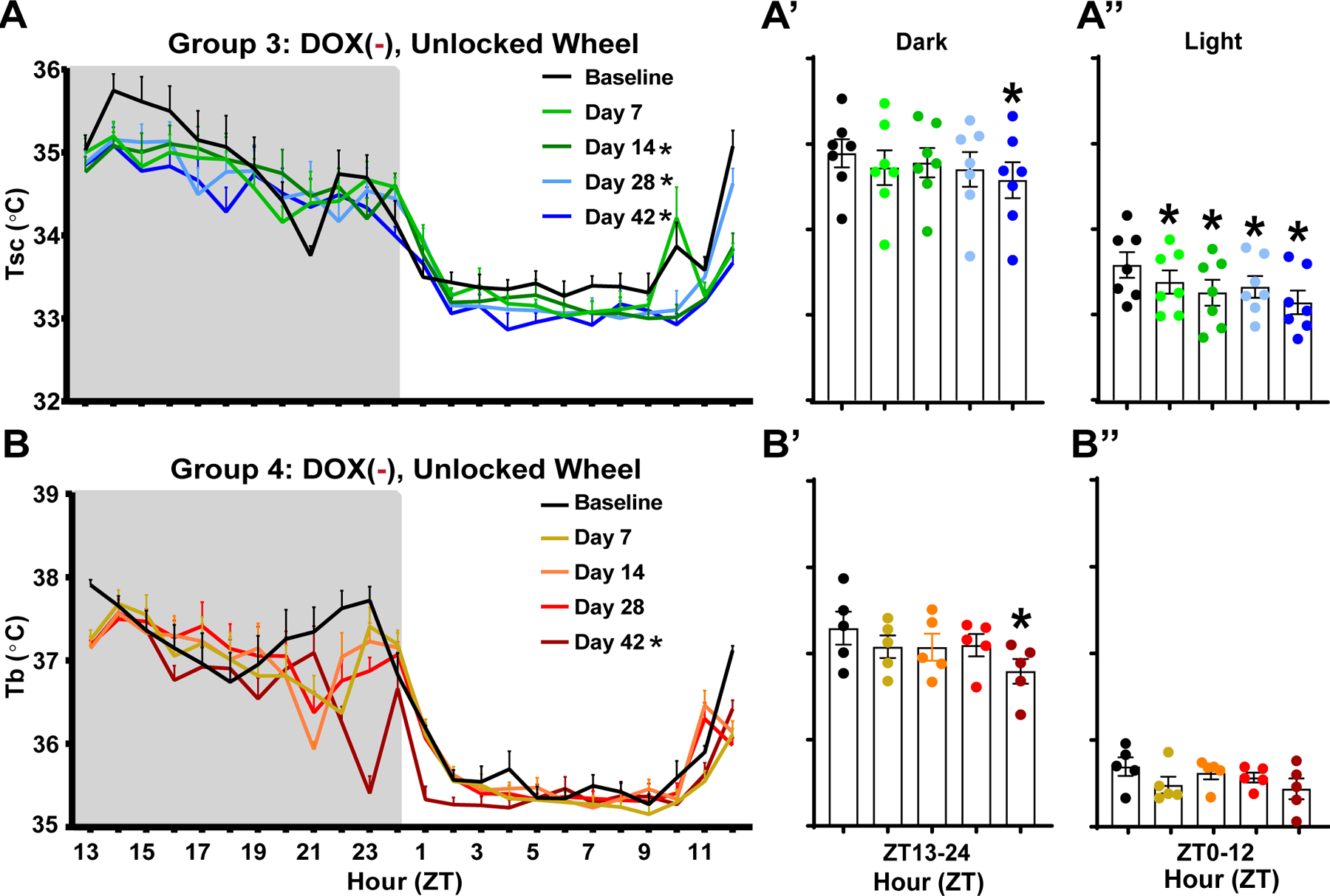

3.3. Tsc declines as Hypocretin/Orexin (Hcrt/Ox) neurons degenerate even when a running wheel is available but core body temperature (Tb) is maintained

Fig. 3 compares Groups 3 and 4 in which both groups of mice had free access to a running wheel while the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerated due to removal of dietary DOX. However, in contrast to Group 3 in which Tsc was measured from a subcutaneously placed telemeter (Figs. 3A, 3A’ and 3A”; same data as Figs. 1C, 1C’ and 1C”), Group 4 mice had an intraperitoneally-placed telemeter which provided a measure of Tb (Figs. 3B, 3B’ and 3B”). While ANOVA indicated a condition effect for Tb in group 4 (F(4, 16) = 3.575, p = 0.0289), in distinction from Group 3 mice in which Tsc progressively declined from baseline on days 14 (p = 0.0192), 28 (p = 0.0165), and 42 (p < 0.0001) post-DOX removal (Fig. 3A), Tb was unchanged in Group 4 mice until Day 42 (p = 0.0066; Fig. 3B). Tb was most significantly altered during the dark phase on day 42 post-DOX removal (p = 0.0198) in comparison to baseline (Fig. 3B’); no significant change in Tb was observed during the light phase (Fig. 3B’’).

Fig. 3.

Peripheral vs. core body temperature as Hypocretin/Orexin neurons degenerate. (A, A’, A’’) Mean subcutaneous (Tsc; n = 7) and (B, B’, B’’) core (Tb; n = 5) body temperature in Group 3 vs. Group 4 male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice initially maintained on DOX with an unlocked running wheel in their home cage. After a baseline recording, mice were switched to normal chow (DOX(−) condition) and recorded at 7, 14, 28, and 42 days after DOX removal during which time the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate. Values are mean ± SEM. * in the legend and above the bars indicates a significant difference during that day relative to baseline as determined by ANOVA. * p < 0.05.

GMA did not vary significantly over the course of Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration in either Group 3 (Figs. 2C, 2C’ and 2C”), or Group 4 (data not shown).

3.4. Running wheel use in Hcrt/Ox neuron-degenerated mice elevates Tsc, particularly during the dark phase

In Group 5, subcutaneously-implanted orexin-DTA mice were housed with a locked running wheel while Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration proceeded in the DOX(−) condition for 42 days. After 42 days in the DOX(−) condition, a 24-hour recording of Tsc and GMA was collected while the running wheel was still locked (Day 0). The wheel was then unlocked and recordings were collected on Days 1, 2, 7, and 14. Results from a two-way ANOVA indicated condition effects for both Tsc (F(4, 32) = 4.046, p = 0.0091) and GMA (F(4, 32) = 8.425, p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests indicated that after unlocking the wheel, Tsc and GMA were indistinguishable on Days 1 and 2 from the locked condition. However, on Day 7 and Day 14, both Tsc (Day 7: p = 0.0024; Day 14: p = 0.0412) and GMA (p = 0.0003; Day 14: p = 0.0002) were increased compared to the locked condition (Day 0). This effect was most evident in the dark phase (Tsc Day 7: p = 0.0020; Tsc Day 14: p = 0.0138; GMA Day 7: p = 0.0003; GMA Day 14: p = 0.0002; Figs. 4A’ and 4B’). In the light period, Tsc (Fig. 4A’’) and GMA (Fig. 4B’’) were only significantly increased on Day 7 (Tsc: p = 0.0179 and GMA: p < 0.0001) compared to the locked condition (Day 0).

Fig. 4.

Peripheral body temperature and GMA changes as Hcrt/Ox neuron-degenerated narcoleptic male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice learn to use a running wheel. Mean subcutaneous (Tsc; A, A’, A’’) body temperature and GMA (B, B’, B’’) in Hcrt/Ox neuron-degenerated male orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice in Group 5 (n = 9) that were housed with a locked running wheel in their home cage. At the end of Day 0, the running wheel was unlocked just prior to light offset at ZT12 and recordings were conducted on days 1, 2, 7, and 14 after the wheel was unlocked. Values are mean ± SEM. * in the legend and above the bars indicates a significant difference during that day relative to the locked condition (Day 0) as determined by ANOVA. * p < 0.05.

3.5. Acute changes in Tsc and Tb during cataplexy bouts in Orexin-tTA;TetO-DTA mice

Removal of DOX from the diet of orexin-DTA mice produces Hcrt/Ox neurodegeneration and cataplexy occurs within 2 weeks in the DOX(−) condition [39, 42]. To the best of our knowledge, neither Tb nor Tsc had been systematically assessed during the period prior and subsequent to the onset of cataplexy. Figure 5 demonstrates that both Tsc and Tb changed acutely before and during a bout of cataplexy. At 3 min before onset of a bout of cataplexy, Tsc was 35.39 ± 0.05°C based on Tsc determinations from 33 cataplexy events from n = 7 mice from experimental group 3 (Fig. 5A) and Tb was 36.27 ± 0.1°C based on Tb measurements from 36 cataplexy events from n = 3 mice from experimental group 4 (Fig. 5B). Mean Tsc and Tb both increased prior to, and peak at, cataplexy onset. Tsc increased to 35.48 ± 0.06°C (p = 0.0229) and Tb to 36.36 ± 0.17°C (p < 0.0001) at cataplexy onset. During cataplexy, Tsc and Tb both decreased (Figs. 5A and B). Average cataplexy bout duration in this analysis was 118.62 ± 6.36 sec. At 3 min after cataplexy onset, which is after termination of all cataplexy bouts included in this analysis, Tsc decreased to 35.30 ± 0.06°C (p = 0.0001) and Tb to 36.28 ± 0.16°C (p = 0.0021).

Fig. 5.

Acute effects of cataplexy occurrence on peripheral and core body temperature in male narcoleptic orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice. Subcutaneous (Tsc) and core (Tb) temperature change (mean ± SEM) from 9 min prior to cataplexy onset to 5 min after cataplexy onset. (A) Tsc determined from 33 cataplexy events from n = 7 mice from experimental group 3. (B) Tb determined from 36 cataplexy events from n = 3 mice from experimental group 4. EEG, EMG, and video were all used to determine cataplexy occurrence following the consensus criteria of the International Working Group on Rodent Models of Narcolepsy: >40 s of EMG atonia, theta-dominated EEG, and behavioral immobility confirmed through video preceded by ≥ 40 s of wakefulness [41]. All cataplexy bouts meeting these criteria were included in this analysis. Horizontal arrows indicate the Tsc and Tb change 3 min before and after cataplexy onset; vertical arrow (Red) indicates time of cataplexy onset. All mice were from the unlocked running wheel condition. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs Cataplexy onset Tsc and Tb.

4. Discussion

4.1. Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons modulate heat loss and thereby affect core body temperature

From the perspective of temperature, the body can be divided into two broad regions, the internal “core” consisting of the central nervous system and viscera, and the external “shell” consisting of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and limbs [43]. While core temperature is actively maintained, varying little from a set range, shell tissue is sensitive to environmental conditions. In the present study, ambient temperature was controlled, so environmental influences are unlikely to have a major effect. Shell temperature can also reflect autonomic thermoregulatory responses [44, 45]. In our narcoleptic mouse model, Tsc follows a similar trend to that of proximal skin temperature in humans with narcolepsy [35]. During the dark period, the major active period for rodents, Tsc is reduced as is proximal skin temperature during wakefulness in people with narcolepsy (Figs. 1B, B’ and B’’). This observation lends further support to notion that loss of Hcrt/Ox neurons results in reduced sympathetic tone, leading to elevated heat loss.

Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration occurs progressively but rapidly in orexin-DTA mice, with 80% cell loss occurring within 7 days, 94.8% within 2 weeks, and 97.2% within 4 weeks [39]. While Tb was maintained during the early stages of Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration, it was significantly reduced by Day 42, primarily during the rodent’s major active phase (Figs. 3B, B’ and B’’). While these results are dissimilar to those obtained in patients with narcolepsy, who exhibited normal Tb during the day but increased Tb early in the night, in the current study, body temperature was measured in orexin-DTA mice over a period of acute degeneration [37]. Diagnosis in humans with narcolepsy often occurs years or decades after Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration occurs [31]. Patients with narcolepsy also often present with comorbid obesity-related, metabolic conditions like diabetes myelitis, which is associated with altered body temperature, or hypertension, which occurs in conjunction with altered sympathetic tone [33, 46, 47]. Once Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration is initiated, orexin-DTA mice exhibit some metabolic alterations that mirror metabolic changes observed in humans with NT1, including weight gain even though cumulative food consumption is unchanged and water consumption reduced [39]. However, discrepancies between the human condition and the narcoleptic phenotype observed in degenerated orexin-DTA mice may be due to longer term network reorganization that inevitably occurs in the interim between development of the condition and diagnosis, or by comorbid metabolic disorders. As such, our results provide insight into the acute effects of loss of Hcrt/Ox neurons, something that is rarely observed clinically in patients with narcolepsy due to the difficulty in diagnosing narcolepsy in its prodromal phase. The acute reduction in Tb observed in this study (Fig. 3B’) may be due to the progressive reduction in sympathetic tone/increase in heat loss occurring as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate, with heat loss exceeding thermogenic capability by Day 42 of degeneration, an idea that should be explored in future studies by measuring BAT function and sympathetic tone.

Alternatively, REM sleep duration has recently been shown to correlate with basal body temperature [48]. The cumulative amount of REM sleep is largely unaltered in orexin-DTA mice [42]. However, the expression of cataplexy which, like REM sleep, is characterized by a sharp decrease in body temperature, develops progressively as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate reaching 8.2 ± 1.4% time over 24-h after 6 Dox(−) weeks in DTA mice [42]. From a thermoregulatory perspective, cataplexy could therefore be equated with REM sleep and the reduced Tsc on Days 14, 28, and 42 of Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration (Fig. 1B’) as well as reduced Tb on Day 42 of degeneration (Fig. 3B’) observed in the present study may be due to increased cataplexy expression; however, this notion requires further study.

4.2. Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration alters activity levels

Body temperature is elevated by sustained exercise and correlates positively with activity and changes in vigilance states [49–52]. In the current study, access to an unlocked running wheel mitigated the reduction in Tsc (Figs. 1C, 1C’, 1C’’, 4A, 4A’ and 4A’’) that occurred over the 42-day Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration period in comparison to mice provided a running wheel that was locked (Figs. 1B, 1B’ and 1B’’), thus preventing the wheel to be used for running. In the locked condition, this Tsc deficit was most prominent during the dark period (Fig. 1B’). In Group 3 mice who had access to an unlocked running wheel, on the other hand, the Tsc deficits were mostly restricted to the light period (Fig.1C’’). While Group 2 mice (locked running wheel) also exhibited a reduction in GMA (Figs. 2B, 2B’ and 2B’’), the Groups 3 and 4 mice (unlocked running wheels) retained activity levels that were nearly identical to baseline (Figs. 2C, 2C’ and 2C’’; data not shown for Group 4). Despite similar activity levels in the unlocked condition, Tsc and Tb is still ultimately reduced in both groups.

Together, these results suggest impacts of Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration on at least two separate processes: those associated with activity and processes that are independent of that effect. While the progressive decrease in activity over the DOX(−) period in the mice provided locked running wheels contributed to the reduction in Tsc that occurred as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerated, the reduction in activity itself may reflect alterations to other processes, rather than changes in thermoregulation per se. Orexin-DTA mice exhibit alterations to sleep/wake when Hcrt/Ox neurons are degenerated, including a reduced ability to sustain wakefulness during the dark period, reflective of the excessive daytime sleepiness that is characteristic of narcolepsy in humans [42]. Excessive sleepiness likely also causes the mice to be less active. The Hcrt/Ox system is also implicated in regulating food intake, the arterial baroceptive reflex, and cardiorespiratory function [53, 54]. Responses of the Hcrt/Ox system immediately precedes autonomic responses [55]. Orexin-DTA mice also gain weight as Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate [39]. In addition to body weight correlating positively with body temperature [56, 57], body weight and physical activity have a bidirectional relationship in humans [58, 59]. Thus, the reduction in activity occurring as a result of loss of Hcrt/Ox input in orexin-DTA mice may be a secondary consequence of a metabolic phenotype resulting from alterations in any of these processes in which Hcrt/Ox signaling are involved. Ultimately, both Tsc and Tb are reduced by Day 42 of the DOX(−) period even when activity is maintained in the unlocked running wheel condition, suggesting that elevated heat loss is occurring, likely through reduced sympathetic tone, or reduced thermogenic capability in these mice after Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration.

It is also of interest to consider why activity was progressively reduced in the presence of a locked running wheel (Figs. 2B, 2B’ and 2B’’), but is maintained when the mice are provided an unlocked running wheel (Figs. 2C, C’ and C’’). Running wheel access increases cataplexy expression in narcoleptic mice, suggesting that the ability to exercise in a running wheel provides a positive emotional stimulus, which is known to promote cataplexy occurrence [40]. It is thus tempting to speculate about a motivational or emotional component driving reduced activity in the absence of positive emotional stimulation since Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission has been implicated in various motivated behaviors [60–65]. Narcolepsy carries a high risk for psychiatric symptoms; however, it is unclear if this comorbidity is due to shared pathophysiology [66]. The acute reduction in activity observed in the current study in the absence of a positive emotional stimulus as Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate in orexin-DTA mice could provide a context in which to study emotional and motivational aspects of narcolepsy.

4.3. Exercise reduces heat loss occurring during Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration: Therapeutic implications in Narcolepsy?

In addition to pharmacological interventions currently approved to treat symptoms in patients with narcolepsy, lifestyle changes are often suggested to aid in symptom management. A low carbohydrate, ketogenic diet has been shown to improve narcoleptic symptomology as indicated by a decrease in patient score on the Narcolepsy Symptom Status Questionnaire and reduction in daytime sleepiness [67]. Cardiopulmonary fitness has an inverse relationship with sleepiness and cataplexy occurrence, lending support to exercise as an effective non-pharmacological intervention [68]. Thermoneutral core warming attenuated the normal decline in psychomotor vigilance test response speed in patients with narcolepsy, while distal skin cooling increased the patient’s ability to maintain wakefulness [36]. These results support non-pharmacological intervention through exercise as well as manipulation of body temperature as effective methods to mitigate narcolepsy symptoms. Figs. 3 and 4 suggest a relationship between exercise and rescue of the reduction in subcutaneously-measured body temperature occurring during Hcrt/Ox neuron degeneration, and thus support the use of exercise for symptom management in narcolepsy. The reduction in heat loss provided through exercise could reduce sleepiness and improve other narcoleptic symptoms. Indeed, running wheel availability was previously shown to reduce sleep fragmentation in another narcoleptic mouse model [40]. Nevertheless, further research thoroughly assessing sleepiness in orexin-DTA mice in the presence and absence of a running wheel is necessary to fully explore this notion.

The acute increases in body temperature preceding cataplexy onset observed in this study (Figs. 5A and B) suggest that body temperature could be a useful predictor for symptom onset. While body temperature changes before and during cataplexy have not been described clinically, a pronounced increase in body temperature has been previously noted to precede sleep attacks in humans with narcolepsy [35, 37]. Future research should focus on fully characterizing body temperature changes occurring across narcoleptic symptomatology in NT1 animal models and patients. Rapid changes in body temperature preceding symptom onset could be exploited to apply an acute intervention to mitigate cataplexy attacks, as well as other symptoms.

4.4. Roles of Hcrt/Ox and colocalized neurotransmitters

In the conditional mouse strain used in this study, Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons are degenerated. While this is reflective of the narcoleptic condition in humans, Hcrt/Ox neurons co-express other neuropeptides also implicated in body temperature regulation. In particular, glutamate and dynorphin have previously been implicated in body temperature regulation and are co-expressed in Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons [69–71]. Intriguingly, while Hcrt/Ox neuron-ablated mice [14, 20] and rats [72] have an attenuated thermogenesis response to stress, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-induced fever, and cold stress, Hcrt/Ox-KO mice exhibit normal stress-induced hyperthermia, PGE2-induced fever, and mount a normal defense against cold stress [14, 20, 72]. These observations suggest a role for Hcrt/Ox neurons but not the Hcrt/Ox neuropeptides in BAT thermogenesis and highlights the importance of an intact Hcrt/Ox system in normal thermoregulation, but also underscores the importance of other molecules co-expressed in Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons in thermogenesis. The activity of putative Hcrt/Ox neurons lacking the Hcrt/Ox peptides increased immediately before the onset of cataplexy attack but decreased during attacks [73]. Local administration of a glutamate receptor antagonist to the dorsomedial hypothalamus inhibits BAT activation by PGE2, suggesting glutamate may be the critical modulator of sympathetic BAT stimulation by neurons in this region including Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons [74]. While the above data suggests colocalized neurotransmitters, most notably glutamate, may play a more critical role in thermoregulation, the studies cited in the Introduction that describe the effects of systemic Hcrt/Ox agonism and antagonism, as well as locally in the rostral raphe pallidus, support the involvement of Hcrt/Ox neurotransmission specifically in maintenance of sympathetic tone and BAT thermogenesis [10, 12–14, 16, 75].

4.5. Study Limitations

All experiments in the current study were conducted in male mice; consequently, impacts of biological sex on this phenotype can’t be addressed. Recent studies have described gender differences in the sleep/wake phenotype and cataplexy occurrence in mouse models of narcolepsy [42, 76, 77]. Impacts of gender and the estrous cycle on body temperature in narcolepsy should be assessed in future studies. In the current study, Tsc and Tb were measured in different individuals. While housing conditions and experimental parameters were rigorously controlled, cohort differences between the Tsc and Tb groups cannot be excluded in the current study.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that Hcrt/Ox-containing neurons are critical regulators of body temperature and autonomic functions related to activity and exercise. More research is needed to differentiate the contribution of the Hcrt/Ox peptides from other colocalized neurotransmitters in these processes. Acute changes in body temperature may predict cataplexy onset in narcolepsy, which could be exploited for the application of an acute intervention to prevent cataplexy/sleep attacks. Finally, exercise partially rescues the increase in heat loss that occurs as Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate, supporting the use of exercise and other metabolic interventions for the treatment of narcolepsy.

Highlights:

Hypocretin/Orexin (Hcrt/Ox) neuron degeneration results in the sleep disorder Narcolepsy and reduced subcutaneous body temperature (Tsc) during the dark phase of the 24-h light/dark cycle.

This reduction in dark phase Tsc is mitigated by access to an exercise opportunity.

In contrast to Tsc, core body temperature (Tb) is largely maintained as the Hcrt/Ox neurons degenerate.

Reduced Tsc while Tb is maintained suggests increased heat loss, possibly through modulation of sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone.

Hcrt/Ox neuron loss in Narcolepsy results in cataplexy, whose occurrence is associated with acute changes in both Tsc and Tb.

Exercise may represent an effective intervention for mitigating heat loss resulting from Hcrt/Ox neuron loss in Narcolepsy.

Acknowledgements

Research supported by NIH R01 NS098813 and R01 NS103529 to T.S.K. and Uehara Memorial Foundation 202040082 to A.Y.

Abbreviations:

- BAT

Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis

- DOX

Doxycycline

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- EMG

Electromyogram

- GMA

Gross Motor Activity

- Hcrt/Ox

Hypocretin/Orexin

- Hcrt 1/Ox-A

Hypocretin 1/Orexin-A

- Hcrt 2/Ox-B

Hypocretin 2/Orexin-B

- HcrtR/OxR

Hypocretin/Orexin Receptor

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- REM sleep

rapid-eye movement sleep

- Tb

Core body temperature

- Tsc

Subcutaneous body temperature

- DTA

Diphtheria toxin A

- Hcrt/Ox-KO mice

Prepro-hypocretin/prepro-orexin protein knockout mice

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests: None

References

- [1].de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG, The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (1998) 322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M, Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior, Cell 92 (1998) 573–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS, Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems, J Neurosci 18 (1998) 9996–10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Date Y, Ueta Y, Yamashita H, Yamaguchi H, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakazato M, Orexins, orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, interact with autonomic, neuroendocrine and neuroregulatory systems, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (1999) 748–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van den Pol AN, Hypothalamic hypocretin (orexin): robust innervation of the spinal cord, J Neurosci 19 (1999) 3171–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK, Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain, J Comp Neurol 435 (2001) 6–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Guan XM, Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain, FEBS Lett 438 (1998) 71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T, Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity, Neuron 30 (2001) 345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Monda M, Viggiano A, Viggiano A, Mondola R, Viggiano E, Messina G, Tafuri D, De Luca V, Olanzapine blocks the sympathetic and hyperthermic reactions due to cerebral injection of orexin A, Peptides 29 (2008) 120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Martin T, Dauvilliers Y, Koumar OC, Bouet V, Freret T, Besnard S, Dauphin F, Bessot N, Dual orexin receptor antagonist induces changes in core body temperature in rats after exercise, Sci Rep 9 (2019) 18432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ida T, Nakahara K, Murakami T, Hanada R, Nakazato M, Murakami N, Possible involvement of orexin in the stress reaction in rats, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 270 (2000) 318–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Oldfield BJ, Giles ME, Watson A, Anderson C, Colvill LM, McKinley MJ, The neurochemical characterisation of hypothalamic pathways projecting polysynaptically to brown adipose tissue in the rat, Neuroscience 110 (2002) 515–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Berthoud HR, Patterson LM, Sutton GM, Morrison C, Zheng H, Orexin inputs to caudal raphe neurons involved in thermal, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal regulation, Histochem Cell Biol 123 (2005) 147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Takahashi Y, Zhang W, Sameshima K, Kuroki C, Matsumoto A, Sunanaga J, Kono Y, Sakurai T, Kanmura Y, Kuwaki T, Orexin neurons are indispensable for prostaglandin E2-induced fever and defence against environmental cooling in mice, J Physiol 591 (2013) 5623–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shahid IZ, Rahman AA, Pilowsky PM, Intrathecal orexin A increases sympathetic outflow and respiratory drive, enhances baroreflex sensitivity and blocks the somato-sympathetic reflex, Br J Pharmacol 162 (2011) 961–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tupone D, Madden CJ, Cano G, Morrison SF, An orexinergic projection from perifornical hypothalamus to raphe pallidus increases rat brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, J Neurosci 31 (2011) 15944–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Plazzi G, Moghadam KK, Maggi LS, Donadio V, Vetrugno R, Liguori R, Zoccoli G, Poli F, Pizza F, Pagotto U, Ferri R, Autonomic disturbances in narcolepsy, Sleep Med Rev 15 (2011) 187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nakamura A, Zhang W, Yanagisawa M, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T, Vigilance state-dependent attenuation of hypercapnic chemoreflex and exaggerated sleep apnea in orexin knockout mice, J Appl Physiol (1985) 102 (2007) 241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuwaki T, Orexinergic modulation of breathing across vigilance states, Respir Physiol Neurobiol 164 (2008) 204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang W, Sunanaga J, Takahashi Y, Mori T, Sakurai T, Kanmura Y, Kuwaki T, Orexin neurons are indispensable for stress-induced thermogenesis in mice, J Physiol 588 (2010) 4117–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Terada J, Nakamura A, Zhang W, Yanagisawa M, Kuriyama T, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T, Ventilatory long-term facilitation in mice can be observed during both sleep and wake periods and depends on orexin, J Appl Physiol (1985) 104 (2008) 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kuwaki T, Orexin links emotional stress to autonomic functions, Auton Neurosci 161 (2011) 20–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kuwaki T, Zhang W, Orexin neurons and emotional stress, Vitam Horm 89 (2012) 135–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kayaba Y, Nakamura A, Kasuya Y, Ohuchi T, Yanagisawa M, Komuro I, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T, Attenuated defense response and low basal blood pressure in orexin knockout mice, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285 (2003) R581–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang W, Sakurai T, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T, Orexin neuron-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation and shift of baroreflex during defense response in mice, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290 (2006) R1654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM, Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy, Neuron 27 (2000) 469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E, A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains, Nat Med 6 (2000) 991–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kornum BR, Narcolepsy Type I as an autoimmune disorder, Handb Clin Neurol 181 (2021) 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Szabo ST, Thorpy MJ, Mayer G, Peever JH, Kilduff TS, Neurobiological and immunogenetic aspects of narcolepsy: Implications for pharmacotherapy, Sleep Med Rev 43 (2019) 23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mahoney CE, Cogswell A, Koralnik IJ, Scammell TE, The neurobiological basis of narcolepsy, Nat Rev Neurosci 20 (2019) 83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bassetti CLA, Adamantidis A, Burdakov D, Han F, Gay S, Kallweit U, Khatami R, Koning F, Kornum BR, Lammers GJ, Liblau RS, Luppi PH, Mayer G, Pollmacher T, Sakurai T, Sallusto F, Scammell TE, Tafti M, Dauvilliers Y, Narcolepsy - clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment, Nat Rev Neurol 15 (2019) 519–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dahmen N, Tonn P, Messroghli L, Ghezel-Ahmadi D, Engel A, Basal metabolic rate in narcoleptic patients, Sleep 32 (2009) 962–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chabas D, Foulon C, Gonzalez J, Nasr M, Lyon-Caen O, Willer JC, Derenne JP, Arnulf I, Eating disorder and metabolism in narcoleptic patients, Sleep 30 (2007) 1267–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Enevoldsen LH, Tindborg M, Hovmand NL, Christoffersen C, Ellingsgaard H, Suetta C, Stallknecht BM, Jennum PJ, Kjaer A, Gammeltoft S, Functional brown adipose tissue and sympathetic activity after cold exposure in humans with type 1 narcolepsy, Sleep 41 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fronczek R, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, van Dijk JG, Van Someren EJ, Altered skin-temperature regulation in narcolepsy relates to sleep propensity, Sleep 29 (2006) 1444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fronczek R, Raymann RJ, Romeijn N, Overeem S, Fischer M, van Dijk JG, Lammers GJ, Van Someren EJ, Manipulation of core body and skin temperature improves vigilance and maintenance of wakefulness in narcolepsy, Sleep 31 (2008) 233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].van der Heide A, Werth E, Donjacour CE, Reijntjes RH, Lammers GJ, Van Someren EJ, Baumann CR, Fronczek R, Core Body and Skin Temperature in Type 1 Narcolepsy in Daily Life; Effects of Sodium Oxybate and Prediction of Sleep Attacks, Sleep 39 (2016) 1941–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sorensen GL, Knudsen S, Petersen ER, Kempfner J, Gammeltoft S, Sorensen HB, Jennum P, Attenuated heart rate response is associated with hypocretin deficiency in patients with narcolepsy, Sleep 36 (2013) 91–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tabuchi S, Tsunematsu T, Black SW, Tominaga M, Maruyama M, Takagi K, Minokoshi Y, Sakurai T, Kilduff TS, Yamanaka A, Conditional ablation of orexin/hypocretin neurons: a new mouse model for the study of narcolepsy and orexin system function, J Neurosci 34 (2014) 6495–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Espana RA, McCormack SL, Mochizuki T, Scammell TE, Running promotes wakefulness and increases cataplexy in orexin knockout mice, Sleep 30 (2007) 1417–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Scammell TE, Willie JT, Guilleminault C, Siegel JM, A consensus definition of cataplexy in mouse models of narcolepsy, Sleep 32 (2009) 111–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sun Y, Tisdale R, Park S, Ma SC, Heu J, Haire M, Allocca G, Yamanaka A, Morairty SR, Kilduff TS, The development of sleep/wake disruption and cataplexy as hypocretin/orexin neurons degenerate in male vs. female Orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA Mice, Sleep 45 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cooper KE, Basic Thermoregulation, in: Greger R, Windhorst U (Eds.), Comprehensive Human Physiology: From Cellular Mechanisms to Integration, Springer Berlin; Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996, pp. 2199–2206. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Low DA, Keller DM, Wingo JE, Brothers RM, Crandall CG, Sympathetic nerve activity and whole body heat stress in humans, J Appl Physiol (1985) 111 (2011) 1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Greaney JL, Kenney WL, Alexander LM, Sympathetic regulation during thermal stress in human aging and disease, Auton Neurosci 196 (2016) 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Esler M, The sympathetic system and hypertension, Am J Hypertens 13 (2000) 99S–105S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kenny GP, Sigal RJ, McGinn R, Body temperature regulation in diabetes, Temperature (Austin) 3 (2016) 119–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Siegel JM, Sleep function: an evolutionary perspective, Lancet Neurol 21 (2022) 937–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fuller A, Carter RN, Mitchell D, Brain and abdominal temperatures at fatigue in rats exercising in the heat, J Appl Physiol (1985) 84 (1998) 877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gleeson M, Temperature regulation during exercise, Int J Sports Med 19 Suppl 2 (1998) S96–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Walters TJ, Ryan KL, Tate LM, Mason PA, Exercise in the heat is limited by a critical internal temperature, J Appl Physiol (1985) 89 (2000) 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Webb P, Daily activity and body temperature, Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 66 (1993) 174–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nattie E, Li A, Respiration and autonomic regulation and orexin, Prog Brain Res 198 (2012) 25–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kuwaki T, Thermoregulation under pressure: a role for orexin neurons, Temperature (Austin) 2 (2015) 379–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yamashita A, Moriya S, Nishi R, Kaminosono J, Yamanaka A, Kuwaki T, Aversive emotion rapidly activates orexin neurons and increases heart rate in freely moving mice, Mol Brain 14 (2021) 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Eriksson H, Svardsudd K, Larsson B, Welin L, Ohlson LO, Wilhelmsen L, Body temperature in general population samples. The study of men born in 1913 and 1923, Acta Med Scand 217 (1985) 347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hoffmann ME, Rodriguez SM, Zeiss DM, Wachsberg KN, Kushner RF, Landsberg L, Linsenmeier RA, 24-h core temperature in obese and lean men and women, Obesity (Silver Spring) 20 (2012) 1585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ekelund U, Brage S, Besson H, Sharp S, Wareham NJ, Time spent being sedentary and weight gain in healthy adults: reverse or bidirectional causality?, Am J Clin Nutr 88 (2008) 612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Preiss D, Thomas LE, Wojdyla DM, Haffner SM, Gill JM, Yates T, Davies MJ, Holman RR, McMurray JJ, Califf RM, Kraus WE, Investigators N, Prospective relationships between body weight and physical activity: an observational analysis from the NAVIGATOR study, BMJ Open 5 (2015) e007901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gulia KK, Mallick HN, Kumar VM, Orexin A (hypocretin-1) application at the medial preoptic area potentiates male sexual behavior in rats, Neuroscience 116 (2003) 921–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Thorpe AJ, Cleary JP, Levine AS, Kotz CM, Centrally administered orexin A increases motivation for sweet pellets in rats, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182 (2005) 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Nair SG, Golden SA, Shaham Y, Differential effects of the hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist SB 334867 on high-fat food self-administration and reinstatement of food seeking in rats, Br J Pharmacol 154 (2008) 406–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Smith RJ, James MH, Aston-Jones G, Motivational activation: a unifying hypothesis of orexin/hypocretin function, Nat Neurosci 17 (2014) 1298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tyree SM, Borniger JC, de Lecea L, Hypocretin as a Hub for Arousal and Motivation, Front Neurol 9 (2018) 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].McGregor R, Thannickal TC, Siegel JM, Pleasure, addiction, and hypocretin (orexin), Handb Clin Neurol 180 (2021) 359–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Morse AM, Sanjeev K, Narcolepsy and Psychiatric Disorders: Comorbidities or Shared Pathophysiology?, Med Sci (Basel) 6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Husain AM, Yancy WS Jr., Carwile ST, Miller PP, Westman EC, Diet therapy for narcolepsy, Neurology 62 (2004) 2300–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Matoulek M, Tuka V, Fialova M, Nevsimalova S, Sonka K, Cardiovascular fitness in narcolepsy is inversely related to sleepiness and the number of cataplexy episodes, Sleep Med 34 (2017) 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Machado NLS, Saper CB, Genetic identification of preoptic neurons that regulate body temperature in mice, Temperature (Austin) 9 (2022) 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Xin L, Geller EB, Adler MW, Body temperature and analgesic effects of selective mu and kappa opioid receptor agonists microdialyzed into rat brain, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 281 (1997) 499–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Yoshimichi G, Yoshimatsu H, Masaki T, Sakata T, Orexin-A regulates body temperature in coordination with arousal status, Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 226 (2001) 468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Mohammed M, Ootsuka Y, Yanagisawa M, Blessing W, Reduced brown adipose tissue thermogenesis during environmental interactions in transgenic rats with ataxin-3-mediated ablation of hypothalamic orexin neurons, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307 (2014) R978–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zhou S, Yamashita A, Su J, Zhang Y, Wang W, Hao L, Yamanaka A, Kuwaki T, Activity of putative orexin neurons during cataplexy, Mol Brain 15 (2022) 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Madden CJ, Morrison SF, Excitatory amino acid receptors in the dorsomedial hypothalamus mediate prostaglandin-evoked thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286 (2004) R320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Monda M, Viggiano A, Viggiano A, Fuccio F, De Luca V, Clozapine blocks sympathetic and thermogenic reactions induced by orexin A in rat, Physiol Res 53 (2004) 507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Arthaud S, Villalba M, Blondet C, Morel AL, Peyron C, Effects of sex and estrous cycle on sleep and cataplexy in narcoleptic mice, Sleep 45 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Piilgaard L, Rose L, Gylling Hviid C, Kohlmeier KA, Kornum BR, Sex-related differences within sleep-wake dynamics, cataplexy, and EEG fast-delta power in a narcolepsy mouse model, Sleep 45 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]