Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer related deaths worldwide and its incidence is increasing due to endemic obesity and the growing burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) associated liver cancer. Although much is known about the clinical and histological pathology of NASH-driven HCC in humans, its etiology remains unclear and there is a lack of reliable biomarkers and limited effective therapies. Progress has been hampered by the scarcity of standardized animal models that recapitulate the gradual progression of NASH towards HCC observed in humans. Here we review existing mouse models and their suitability for studying NASH-driven HCC with special emphasis on a preclinical model that we recently developed that faithfully mimics all the clinical endpoints of progression of the human disease. Moreover, it is highly translatable, allows the use of gene-targeted mice, and is suitable for gaining knowledge of how NASH progresses to HCC and development of new targets for treatment.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver cancer

Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Progression to Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Liver cancer is the second and sixth leading causes of cancer related deaths worldwide in men and women, respectively (Sung et al., 2021). The major etiologies of liver cancer, including the primary form of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), each of which contributed to a significant 25% increase in liver cancer deaths from 2010 to 2019 (Huang et al., 2022). Importantly, while HBV and HCV remain the largest contributors to liver cancer etiology, during this period NASH was identified as the fastest growing etiology of liver cancer incidence as well as liver cancer deaths globally (Huang et al., 2022). This increase in NASH-related liver cancer deaths was particularly evident in the Americas and has been associated with a rapid rise in obesity (Ward et al., 2019). Moreover, NASH-driven liver cancer incidence is projected to increase in the next decade in the United States, Europe, and Asia (Estes et al., 2018).

NASH is a severe subtype of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). As a major cause of chronic liver disease, NAFLD is often associated with obesity, adipose dysfunction, inflammation, and insulin resistance. NAFLD represents a spectrum of liver disease states, histologically graded from simple steatosis to NASH and pericellular fibrosis, that can gradually advance to cirrhosis (Diehl and Day, 2017; Loomba and Sanyal, 2013; Nikolova-Karakashian, 2018). In addition to steatosis, hallmarks of NASH include hepatocellular injury and ballooning, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis (Farrell and Larter, 2006). Diagnosis of NASH occurs in 25% of NAFLD patients and can further progress to end-stage liver disease and HCC (Llovet et al., 2021; Sun and Karin, 2012). Nevertheless, even though both incidence and deaths from HCC have risen significantly (Huang et al., 2022), our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the progression from NASH to HCC, which in humans develops over the span of decades, remains limited and is dependent on reliable preclinical animal models.

NASH has been hypothesized to develop as the result of multiple “hits” to the liver including, insulin resistance, adipokines secreted from adipose tissue, overnutrition, microbiome, and genetic factors (Buzzetti et al., 2016). A sedentary lifestyle combined with excess consumption of high caloric diets, particularly enriched in fructose, and predisposed genetic factors are associated with hepatic steatosis and obesity (Cohen et al., 2011). High fructose diets drive liver lipid accumulation through increased de novo lipogenic gene expression and triglyceride accumulation (Softic et al., 2016). However, it is now well recognized that simple hepatic steatosis is not enough to drive the progression to NASH. Additional events are required, including liver oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and inflammation with the manifestation of hepatocellular injury/ballooning and fibrosis (Anstee et al., 2019; Llovet et al., 2021; Nikolova-Karakashian, 2018; Otani et al., 2020; Sun and Karin, 2012). The development of both NASH and HCC depend on elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. In chronic liver diseases, the autophagy receptor p62 is known to accumulate and form aggregates in NASH-associated Mallory bodies (Denk et al., 2006). More recently, hepatic accumulation of p62 was identified to accumulate in both mice and humans, and it is required for transition of premalignant hepatocytes to HCC (Umemura et al., 2016). Moreover, elevated p62 expression was found in non-tumor tissue from patients with early HCC that correlated with increased cancer recurrence and reduced disease-free survival (Umemura et al., 2016). In addition, NASH is associated with the accumulation of free non-esterified cholesterol (Farrell and van Rooyen, 2012; Ioannou, 2016), which along with oxidized cholesterol is cytotoxic to hepatocytes and, together with TNF-α, causes mitochondrial dysfunction and liver damage. Although the mechanism of NASH transition to HCC is unclear, it has been suggested to result from hepatocellular injury and inflammation that drives a compensatory proliferative response and the development of liver cancer (Font-Burgada et al., 2016). While much is known about the clinical pathology of this disease, there remains a lack of reliable biomarkers and importantly effective therapies for NASH-driven HCC is limited (Llovet et al., 2021). A hindrance to drug development has been the scarcity of standardized mouse models that mimic the gradual progression of NASH towards HCC observed in humans. We will focus the following discussion on existing mouse models and their suitability for studying NASH-driven HCC with special emphasis on a preclinical model that we recently developed that faithfully mimics the human pathology and shows robust progression to HCC.

Toxin-induced Models of NASH and HCC

Approaches to increase the incidence and shorten the time to develop HCC in a NASH-like context in mice have relied on the administration of toxins, such as diethylnitrosamine (DEN), streptozotocin (STZ), and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Initial studies utilized the widely used procarcinogen DEN combined with a high fat diet (HFD). This approach demonstrated that HFD-induced obesity efficiently promoted liver tumor formation, and mechanistically, this effect was dependent on elevated production of the tumor promoting cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (Park et al., 2010). Nevertheless, while these mice develop obesity, insulin resistance, steatosis, inflammation, and ER stress, this model lacks the presence of NASH or fibrosis. STZ administration has classically been used preclinically to model type 1 diabetes (T1D), as it is toxic to pancreatic β-cells responsible for production of insulin. In a newer model, neonatal mice were administered low dose STZ followed by feeding HFD starting at 4 weeks of age (Saito et al., 2015). After 1 week of HFD, these mice displayed hepatic steatosis, which was followed by a progressive increase in lobular inflammation, NASH pathology, and fibrosis. By 20 weeks on HFD, STZ treated mice showed indications of HCC. However, these mice progress to NASH and HCC in a lean state with T1D, whereas human NASH-related HCC most often occurs with obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. This combined with a mild fibrosis phenotype indicates STZ, a DNA damaging toxin, plus HFD may represent a model more similar to DEN with HFD feeding. More recently, another mouse model was developed to induce rapid steatohepatitis, significant fibrosis, as well as HCC (Tsuchida et al., 2018). In this model, mice were fed a Western high fat, high cholesterol (1.2%), and fructose diet (WD) combined with weekly low dose administration of CCl4 (WD/CCl4). After 12 weeks, livers of these mice showed classic histopathological signs of NASH and stage 3 fibrosis. After 24 weeks, 100% of mice on the WD/CCl4 regimen produced liver tumors, of which 30% were HCC. In addition, transcriptome profiling to compare WD/CCl4 with other models found a close correlation of pathways altered in WD/CCl4 livers with pathways affected in human NASH patients. Although this model develops clear NASH pathology with significant fibrosis and HCC, WD/CCl4 treatment does not promote obesity or insulin resistance (Tsuchida et al., 2018). Thus, while these models have provided advances in the understanding of NASH-driven HCC, these approaches are less physiologically relevant as they induce genotoxicity and the majority of NASH in humans does not involve exposure to toxins (Asgharpour and Sanyal, 2022).

Dietary Models of NASH and HCC

In humans, obesity and its related NAFLD/NASH complications have been associated with excessive consumption of calorie-rich diets high in saturated fat, cholesterol, and sugar, particularly enriched in fructose (Ioannou, 2016; Jensen et al., 2018; Softic et al., 2016). Originally, mouse models fed HFD regimens with excess saturated fat (e.g. 60% HFD) were useful for inducing obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis (Table I). However, HFD alone was later shown not to cause significant hepatocellular injury/ballooning and inflammation and, in turn, did not progress to NASH (Nakagawa et al., 2014). Diets deficient in methionine and/or choline promote steatosis, fibrosis, and a NASH-like phenotype. The disadvantage of methionine or choline-deficient diets is the promotion of rapid weight loss without inducing HCC, and these regimens do not mimic the etiology and metabolic features of human NASH (Machado et al., 2015). As such, models that progress to hepatocellular ballooning, a hallmark of NASH, and fibrosis and HCC require additional modifications to the dietary regimen. For example, a choline-deficient HFD caused a phenotype consistent with metabolic syndrome, NASH, and NASH-induced HCC; however, the penetrance of HCC was very low (Wolf et al., 2014). Another model based on a high trans-fat and sugar diet led to obesity, steatosis, and HCC, but it did not cause hepatocellular ballooning and it is unclear as to whether the metabolic and immune responses mimic those in humans (Dowman et al., 2014). A study using the Gubra-Amylin NASH diet (40% high-fat, 22% high-fructose, 2% high-cholesterol) found it reliably caused elevated histopathological and molecular markers consistent with NASH and induced HCC in C57BL/6J mice (Mollerhoj et al., 2022). However, this diet contains 2% cholesterol, a level considered to cause “toxic steatohepatitis” and to be less physiologically relevant (Farrell and van Rooyen, 2012). More recently, we and others, found that a combination of high fat, 0.2% cholesterol, and sugar diets led to the gradual progression of NASH as well as HCC (Asgharpour et al., 2016; Green et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Comparison of diet-induced NASH and HCC mouse models (Modified from Green et al 2022).

| Model | Obesity | Insulin resistance | Steatosis | Inflammation/ ER stress | Ballooning | Fibrosis | p62 Accumulation |

HCC | Human NASH Gene Signature |

Human Prognosis Gene Signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6J HFD | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | − | − | − | − | − | nd |

| C57BL/6J Methionine/Choline -deficient diet | − | − | + | + | − | ++ | nd | − | nd | nd |

| C57BL/6J Choline-deficient diet | − | − | + | + | − | ++ | nd | − | nd | nd |

| MCD + HFD | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | nd | − | − | nd |

| CD + HFD | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | nd | + | nd | nd |

| Trans-fat + high sugar diet | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | nd | ++ | nd | nd |

| C57BL/6J High fat/sugar diet +2% Chol | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | nd | ++ | ++ | nd |

| C57BL/6J MUP-uPA Tg HFD | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | nd |

| C57BL/6J:129S High fat/sugar diet +0.2% Chol +SW | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | nd | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| C57BL/6NJ High fat/sugar diet +0.2% Chol +SW | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

, highly present

, moderately present

, not present or negative

, not determined

HFD, high fat diet; MCD, methionine- and choline-deficient diet; CD, choline-deficient diet; Chol, cholesterol; SW, sugar water.

Genetic Manipulations to Model NASH and HCC

A number of genetic models have been developed that promote the onset of NASH and HCC (Febbraio et al., 2019). Nevertheless, a majority of these models fail to faithfully recapitulate all of the hallmarks of obesity-related metabolic disease and NASH-driven HCC. Mice with global knockouts of regulators of peroxisome proliferation and fatty acid oxidation, specifically peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and acetyl-coenzyme A oxidase (AOX), or methionine metabolism through methionine adenosyl transferase 1A (MAT1A) exhibit inflammation, ER stress, NASH, fibrosis, and HCC (Febbraio et al., 2019). However, as previously reviewed these genetic knockouts do not present with obesity, insulin resistance, or hepatic steatosis as found in obesity-related HCC in humans (Febbraio et al., 2019). In sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) overexpressing transgenic mice and phosphatase and tensin homolog 10 (PTEN) knockout mice, except for the absence of obesity, these display most of the key characteristics of NASH and the incidence of HCC (reviewed in (Febbraio et al., 2019)). Furthermore, the liver gene expression profile of PTEN knockout mice is very different from other mouse models of steatosis and NASH (Teufel et al., 2016).

More recently, a transgenic mouse line was developed in which high levels of urokinase plasminogen activator is transiently overexpressed (MUP-uPA Tg) in hepatocytes during the first 6 weeks of age (Nakagawa et al., 2014). This transient overexpression in MUP-uPA livers causes ER stress and liver damage. Upon feeding HFD, MUP-uPA mice gradually develop obesity and many of the histopathological indicators of NASH, including hepatic ballooning, inflammatory cell infiltration, and pericellular/bridging fibrosis, and other key molecular markers associated with NASH-driven HCC as found in human patients (Nakagawa et al., 2014). Interestingly, TNF-α production, ER stress, and hepatic p62 expression are all required for the onset of NASH and HCC in MUP-uPA mice (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Umemura et al., 2016). In addition, there was a concordance between the patterns of metabolic and signaling pathway activation at the transcriptomic level between MUP-uPA mice fed HFD and human NASH (Shalapour et al., 2017).

Another genetic model recently developed is the isogenic C57BL/6J:129S hybrid strain fed HFD with access to high-fructose-glucose sugar water (HFD/SW), nicknamed DIAMOND for a diet-induced animal model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Asgharpour et al., 2016). DIAMOND mice exhibit hepatic steatosis after 8 weeks on HFD/SW and key characteristics of NASH after 16–24 weeks, including hepatocellular injury/ballooning, inflammation, and fibrosis, which is further increased after 52 weeks (Asgharpour et al., 2016). Importantly, 90% of these livers develop HCC, and extensive gene expression profiling demonstrated significant overlap between changes found in DIAMOND livers and tumors as observed in human NASH liver and HCC samples from human patients (Asgharpour et al., 2016; Cazanave et al., 2017). Thus, both MUP-uPA and DIAMOND models represent transgenic/isogenic approaches that mimic the disease in humans and will be useful for further drug development studies. However, the unique genetic background of DIAMOND mice makes it problematic to cross them with other gene-targeted mice, most of which are on a pure C57BL/6 background. Thus, this prevents exploration of the genetic elucidation of factors and/or signaling pathways involved in NASH to HCC progression and hampers development of new targets.

Development of a Preclinical Model of Diet-Induced Progression of NASH to HCC that Faithfully Mimics the Human Disease

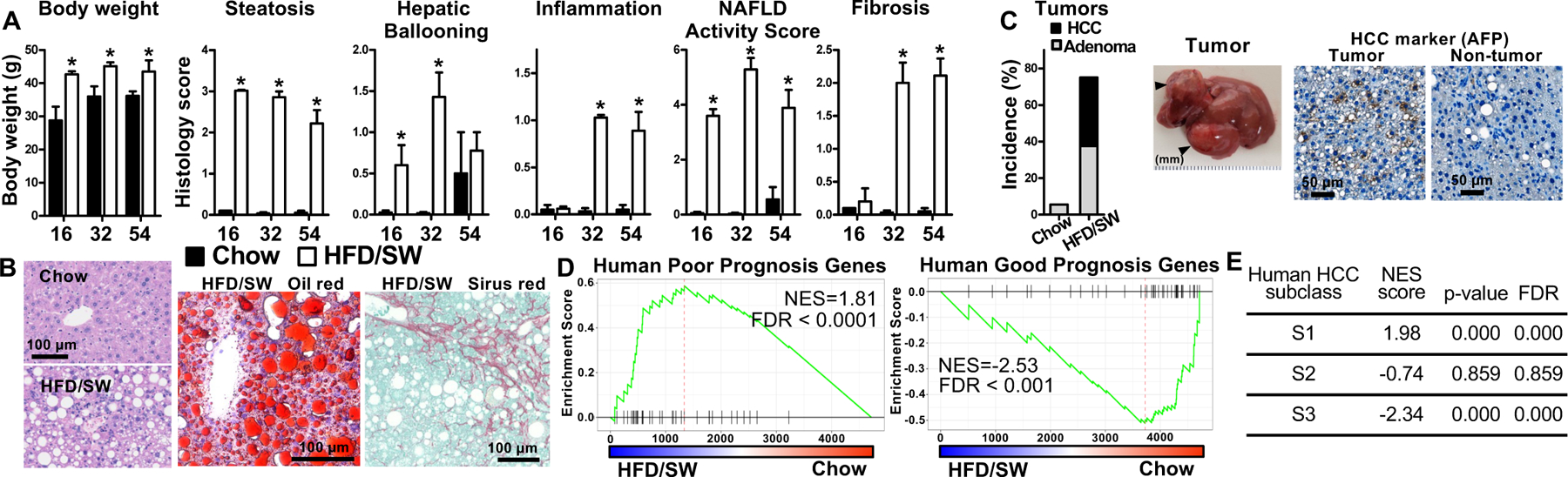

Guided by this diet-induced model in isogenic 129S1/C57Bl/6 hybrid mice (Asgharpour et al., 2016) and to overcome the problem of this complex genetic background, we recently developed a NASH-driven HCC model in pure C57BL/6NJ mice, a commonly used strain easily amenable to genetic manipulations. To this end, mice were fed a high fat, high carbohydrate with 0.2% cholesterol diet (HFD) and high fructose-glucose drinking water (sugar water, SW) for up to 54 weeks (Green et al., 2022) (Figure 1). Mice on HFD/SW developed weight gains and marked hepatic steatosis, confirmed by Oil-Red-O staining at 16 weeks (Figure 2A,B). These mice sequentially developed steatohepatitis characterized by steatosis, lobular inflammation and hepatocellular ballooning, and Mallory-Denk bodies at 32 weeks (Figure 2A,B). Mice also developed insulin resistance (Green et al., 2022). Liver fibrosis progressively increased from 16 weeks onward and remained sustained up to 54 weeks (Figure 2A,B). NASH is a major HCC catalyst in humans (Cohen et al., 2011; El-Serag, 2011). Intriguingly, at 54 weeks, more than 75% of the mice on HFD/SW diet spontaneously developed multiple foci of tumors, 50% HCC, confirmed by histologic examination with loss of hepatic architecture and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) expression (Figure 2C). There was strong similarity of cell signaling pathways including lipogenic, inflammatory, oxidative stress, and apoptotic pathways activated in human NASH (Green et al., 2022) and concordance of transcriptomic gene signatures with human HCC and a more invasive human subclass S1 (Figure 2D,E). In contrast, only 1/18 mice on chow diet developed an adenoma (Figure 2C). Similar to sex differences in humans (Buettner and Thimme, 2019; Li et al., 2019), wild-type female mice fed HFD/SW diet did not develop liver tumors (0/15 mice). Hence, in contrast to several widely used NASH mouse models with little to no overlap in gene expression with human NASH livers (Teufel et al., 2016) (Table I), our model of chronic HFD/SW feeding led to similar metabolic dysfunctions as observed in obesity-related NAFLD/NASH in humans. These mice also exhibited key clinical histopathological and many of the molecular markers, including increases in those for de novo lipogenesis, ER stress, p62, a proinflammatory response, and bridging fibrosis, that are associated with NASH and development of HCC in humans (Green et al., 2022). In addition, gene expression profiling identified changes consistent with known signatures of NASH and poor prognosis in humans (Green et al., 2022). Although similar to our findings, a recent study also found consistent NASH and HCC development in C57BL/6J mice fed high fat diet supplemented with 2% cholesterol and high sugar (Mollerhoj et al., 2022). However, p62 accumulation and association with poor prognosis of HCC in humans were not examined (Table I). While diets high in saturated fat, trans-fat, carbohydrates in the form of fructose, and cholesterol increase the risk of developing NAFLD/NASH (Clapper et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2010; Walenbergh and Shiri-Sverdlov, 2015), dietary regimens of a more physiologically relevant ‘Western’ diet in mice promote NASH pathology and exhibit similar clinical and histological features of human NASH and progression to HCC (Asgharpour et al., 2016; Clapper et al., 2013). Overall, our preclinical model is more physiologically relevant, faithfully mimics the sexual dimorphism and all the clinical endpoints of progression of the human disease. Moreover, it is highly translatable (Buettner and Thimme, 2019), allows the use of gene-targeted mice, and will provide the field with a foundation for further research as it is well suitable for gaining new knowledge of how NASH progresses to HCC and development of new targets for treatment. It enabled us to begin exploring the phenotypes of gene targeted mice, required for the genetic elucidation of factors and/or signaling pathways involved in NASH to HCC progression.

Figure 1. A new preclinical mouse model we developed that mimics the progression of human NASH to HCC.

Schematic representation of mice chronically fed chow or a diet high in fat, cholesterol, and sugar with ad libitum access to high fructose/glucose sugar water (HFD/SW), which mimics the gradual progression to NASH and HCC as in the human disease. The histopathologic and transcriptomic characteristics at the respective time points are described. For more details see text and (Green et al., 2022).

Figure 2. HFD/SW fed mice sequentially develop fatty liver, steatohepatitis, advanced fibrosis, and liver tumors that recapitulate human HCC.

Male C57Bl/6NJ mice were fed a chow diet (filled bars) or HFD/SW (open bars) for 16, 32, and 54 weeks. (A) Body weight and histology scores for steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, lobular inflammation, fibrosis and NAFLD Activity Score were quantified in a blinded manner by an expert pathologist as we described (17,48). (B) Representative liver sections from 54-week mice stained with H&E, Oil-Red or Picrosirus Red. (C) At 54 weeks, % tumor incidence includes adenoma (open) and HCC (black). Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to Chow. (n=6–18). Immunostaining of HCC marker AFP. (D) Concordance by Gene set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) between 73 poor prognosis- and 113 good prognosis-correlated genes in human HCC and the pattern of gene expression in mice at 54 weeks. (E) GSEA between human HCC subclasses and genes upregulated in HFD/SW mice. NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. Data in this figure was modified from (Green et al., 2022).

Conclusions

NASH associated HCC is a complex disease and is the fastest growing cause of cancer-related deaths (Huang et al., 2022). Due to its complex etiology, effective treatments, biomarkers, and surveillance programs are limited, particularly for monitoring those patients not presenting with cirrhosis. As such, understanding the mechanisms underlying the progression from NASH to HCC is critical for designing better treatments and is dependent on reliable preclinical animal models that mimic the course of disease in humans. Currently, while MUP-uPA Tg and DIAMOND mice are important advances in preclinical models and will be useful for examining potential therapeutic strategies, our new model with a more physiologically relevant diet, and without the use of genotoxic agents, both recapitulates the hallmarks of NASH-driven HCC as found in humans and is easily adaptable to gene targeted approaches. Future studies utilizing these models, which more faithfully represent the disease progression, will be important for elucidating the mechanisms of NASH associated HCC as well as examining new treatments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the NIH R01GM043880 (S.S) and 1R01CA266124 (C.D.G and S.S). We thank Dr. Cynthia Weigel for assisting with figure preparation. Liver graphics were created with BioRender.com (SM24HUZRC6).

Abbreviations:

- AOX

acetyl-coenzyme A oxidase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GTT

glucose tolerance test

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HFD

high fat diet

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog 10

- SREBP1

sterol regulatory element binding protein 1

- SW

sugar water

- STZ

streptozotocin

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, Govaere O, Heikenwalder M, 2019. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16(7), 411–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgharpour A, Cazanave SC, Pacana T, Seneshaw M, Vincent R, Banini BA, Kumar DP, Daita K, Min HK, Mirshahi F, Bedossa P, Sun X, Hoshida Y, Koduru SV, Contaifer D Jr., Warncke UO, Wijesinghe DS, Sanyal AJ, 2016. A diet-induced animal model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular cancer. J. Hepatol 65(3), 579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgharpour A, Sanyal AJ, 2022. Generation of a Diet-Induced Mouse Model of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Methods Mol Biol 2455, 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner N, Thimme R, 2019. Sexual dimorphism in hepatitis B and C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Immunopathol 41(2), 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA, 2016. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 65(8), 1038–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazanave S, Podtelezhnikov A, Jensen K, Seneshaw M, Kumar DP, Min HK, Santhekadur PK, Banini B, Mauro AG, A, M.O., Vincent R, Tanis KQ, Webber AL, Wang L, Bedossa P, Mirshahi F, Sanyal AJ, 2017. The Transcriptomic Signature Of Disease Development And Progression Of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci Rep 7(1), 17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapper JR, Hendricks MD, Gu G, Wittmer C, Dolman CS, Herich J, Athanacio J, Villescaz C, Ghosh SS, Heilig JS, Lowe C, Roth JD, 2013. Diet-induced mouse model of fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis reflecting clinical disease progression and methods of assessment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305(7), G483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH, 2011. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332(6037), 1519–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk H, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Muller T, Farr G, Muller W, Terracciano L, Zatloukal K, 2006. Are the Mallory bodies and intracellular hyaline bodies in neoplastic and non-neoplastic hepatocytes related? J Pathol 208(5), 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl AM, Day C, 2017. Cause, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 377(21), 2063–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowman JK, Hopkins LJ, Reynolds GM, Nikolaou N, Armstrong MJ, Shaw JC, Houlihan DD, Lalor PF, Tomlinson JW, Hubscher SG, Newsome PN, 2014. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma in a murine model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced by use of a high-fat/fructose diet and sedentary lifestyle. Am J Pathol 184(5), 1550–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, 2011. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 365(12), 1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, Bantel H, Bellentani S, Caballeria J, Colombo M, Craxi A, Crespo J, Day CP, Eguchi Y, Geier A, Kondili LA, Kroy DC, Lazarus JV, Loomba R, Manns MP, Marchesini G, Nakajima A, Negro F, Petta S, Ratziu V, Romero-Gomez M, Sanyal A, Schattenberg JM, Tacke F, Tanaka J, Trautwein C, Wei L, Zeuzem S, Razavi H, 2018. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016–2030. J Hepatol 69(4), 896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell GC, Larter CZ, 2006. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology 43(2 Suppl 1), S99–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell GC, van Rooyen D, 2012. Liver cholesterol: is it playing possum in NASH? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303(1), G9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Reibe S, Shalapour S, Ooi GJ, Watt MJ, Karin M, 2019. Preclinical Models for Studying NASH-Driven HCC: How Useful Are They? Cell Metab 29(1), 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font-Burgada J, Sun B, Karin M, 2016. Obesity and Cancer: The Oil that Feeds the Flame. Cell Metab 23(1), 48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CD, Weigel C, Brown RDR, Bedossa P, Dozmorov M, Sanyal AJ, Spiegel S, 2022. A new preclinical model of western diet-induced progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma. FASEB J 36(7), e22372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R, 2022. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab 34(7), 969–977 e962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou GN, 2016. The Role of Cholesterol in the Pathogenesis of NASH. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27(2), 84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, Nadeau KJ, Green M, Roncal C, Nakagawa T, Kuwabara M, Sato Y, Kang DH, Tolan DR, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Rosen HR, Lanaspa MA, Diehl AM, Johnson RJ, 2018. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 68(5), 1063–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xu A, Jia S, Huang J, 2019. Recent advances in the molecular mechanism of sex disparity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett 17(5), 4222–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH, 2010. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 7(5), 251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS, 2021. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7(1), 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, 2013. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 10(11), 686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado MV, Michelotti GA, Xie G, Almeida Pereira T, Boursier J, Bohnic B, Guy CD, Diehl AM, 2015. Mouse models of diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis reproduce the heterogeneity of the human disease. PLoS One 10(5), e0127991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollerhoj MB, Veidal SS, Thrane KT, Oro D, Overgaard A, Salinas CG, Madsen MR, Pfisterer L, Vyberg M, Simon E, Broermann A, Vrang N, Jelsing J, Feigh M, Hansen HH, 2022. Hepatoprotective effects of semaglutide, lanifibranor and dietary intervention in the GAN diet-induced obese and biopsy-confirmed mouse model of NASH. Clin Transl Sci 15(5), 1167–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Umemura A, Taniguchi K, Font-Burgada J, Dhar D, Ogata H, Zhong Z, Valasek MA, Seki E, Hidalgo J, Koike K, Kaufman RJ, Karin M, 2014. ER stress cooperates with hypernutrition to trigger TNF-dependent spontaneous HCC development. Cancer Cell 26(3), 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova-Karakashian M, 2018. Alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Focus on ceramide. Adv Biol Regul 70, 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani T, Mizokami A, Kawakubo-Yasukochi T, Takeuchi H, Inai T, Hirata M, 2020. The roles of osteocalcin in lipid metabolism in adipose tissue and liver. Adv Biol Regul 78, 100752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, Osterreicher CH, Takahashi H, Karin M, 2010. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 140(2), 197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Uebanso T, Maekawa K, Ishikawa M, Taguchi R, Nammo T, Nishimaki-Mogami T, Udagawa H, Fujii M, Shibazaki Y, Yoneyama H, Yasuda K, Saito Y, 2015. Characterization of hepatic lipid profiles in a mouse model with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and subsequent fibrosis. Sci Rep 5, 12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalapour S, Lin XJ, Bastian IN, Brain J, Burt AD, Aksenov AA, Vrbanac AF, Li W, Perkins A, Matsutani T, Zhong Z, Dhar D, Navas-Molina JA, Xu J, Loomba R, Downes M, Yu RT, Evans RM, Dorrestein PC, Knight R, Benner C, Anstee QM, Karin M, 2017. Inflammation-induced IgA+ cells dismantle anti-liver cancer immunity. Nature 551(7680), 340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S, Cohen DE, Kahn CR, 2016. Role of Dietary Fructose and Hepatic De Novo Lipogenesis in Fatty Liver Disease. Dig Dis Sci 61(5), 1282–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Karin M, 2012. Obesity, inflammation, and liver cancer. J Hepatol 56(3), 704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F, 2021. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3), 209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel A, Itzel T, Erhart W, Brosch M, Wang XY, Kim YO, von Schonfels W, Herrmann A, Bruckner S, Stickel F, Dufour JF, Chavakis T, Hellerbrand C, Spang R, Maass T, Becker T, Schreiber S, Schafmayer C, Schuppan D, Hampe J, 2016. Comparison of Gene Expression Patterns Between Mouse Models of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Liver Tissues From Patients. Gastroenterology 151(3), 513–525 e510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T, Lee YA, Fujiwara N, Ybanez M, Allen B, Martins S, Fiel MI, Goossens N, Chou HI, Hoshida Y, Friedman SL, 2018. A simple diet- and chemical-induced murine NASH model with rapid progression of steatohepatitis, fibrosis and liver cancer. J Hepatol 69(2), 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura A, He F, Taniguchi K, Nakagawa H, Yamachika S, Font-Burgada J, Zhong Z, Subramaniam S, Raghunandan S, Duran A, Linares JF, Reina-Campos M, Umemura S, Valasek MA, Seki E, Yamaguchi K, Koike K, Itoh Y, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J, Karin M, 2016. p62, Upregulated during Preneoplasia, Induces Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis by Maintaining Survival of Stressed HCC-Initiating Cells. Cancer Cell 29(6), 935–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walenbergh SM, Shiri-Sverdlov R, 2015. Cholesterol is a significant risk factor for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9(11), 1343–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Giles CM, Flax C, Long MW, Gortmaker SL, 2019. Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. N Engl J Med 381(25), 2440–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MJ, Adili A, Piotrowitz K, Abdullah Z, Boege Y, Stemmer K, Ringelhan M, Simonavicius N, Egger M, Wohlleber D, Lorentzen A, Einer C, Schulz S, Clavel T, Protzer U, Thiele C, Zischka H, Moch H, Tschop M, Tumanov AV, Haller D, Unger K, Karin M, Kopf M, Knolle P, Weber A, Heikenwalder M, 2014. Metabolic activation of intrahepatic CD8+ T cells and NKT cells causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cancer via cross-talk with hepatocytes. Cancer Cell 26(4), 549–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]