Abstract

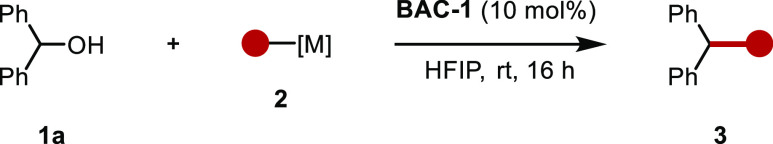

A boronic acid catalyzed carbon–carbon and carbon–nitrogen bond-forming reaction for the functionalization of various π-activated alcohols has been developed. Ferrocenium boronic acid hexafluoroantimonate salt was identified as an effective catalyst in the direct deoxygenative coupling of alcohols with a variety of potassium trifluoroborate and organosilane nucleophiles. In a comparison between these two classes of nucleophiles, the use of organosilanes leads to higher reaction yields, increased diversity of the alcohol substrate scope, and high E/Z selectivity. Furthermore, the reaction proceeds under mild conditions and yields up to 98%. Computational studies provide a rationalization for a mechanistic pathway for the retention of E/Z stereochemistry when E or Z alkenyl silanes are used as nucleophiles. This methodology is complementary to existing methodologies for deoxygenative coupling reactions involving organosilanes, and it is effective with a variety of organosilane nucleophile sub-types, including allylic, vinylic, and propargylic trimethylsilanes.

Introduction

Cross-coupling reactions are of great importance in organic synthesis due to their ability to rapidly introduce molecular complexity.1−4 However, conventional methods rely on exotic metal-based catalysts that are often costly, potentially toxic, and sensitive to air and moisture. Additionally, the use of organohalides as electrophilic coupling partners in these reactions results in the stoichiometric generation of halogenated byproducts. Therefore, the development of cross-coupling reactions involving widely available and inexpensive starting materials, while producing environmentally benign waste, is highly desirable.5−7

The hydroxy functional group is ubiquitous in nature, with approximately two-thirds of biologically active natural products containing at least one.8,9 Alcohols, the simplest class of hydroxy-containing molecules, are widely commercially available, and for this reason, they are a particularly appealing class of substrate for cross-coupling reactions. However, due to the challenging nature of C(sp3)–OH bond cleavage,5 most conventional synthetic strategies rely on pre-activation of the hydroxy group, followed by substitution, resulting in the generation of stoichiometric waste and reduced step-economy (Figure 1).10−12 Recent efforts by Dong and MacMillan have focused on eliminating the pre-activation step through the in situ formation of an NHC–alcohol intermediate, which can then participate in metallophotoredox coupling.13−15 Similar strategies for in situ alcohol activation that enable transition metal, electrochemical, and photocatalytic cross-coupling have also been reported.16−18 While these methodologies are accommodating to a diverse scope of alcohols and nucleophiles alike, the in situ activation step is still stoichiometric, leading to the generation of large amounts of waste.

Figure 1.

Hydroxy group activation.

Over the past two decades, a significant amount of attention has been directed at the development of deoxygenative coupling of alcohols with air-stable organometallic reagents. Several examples have been reported, which take advantage of the nucleophilicity of organoboron and organosilicon reagents. However, a general catalytic method that is amenable to a diverse scope of the substrate in terms of both the alcohol and the organometallic reagent is yet to be reported. The allylation of alcohols with allyltrimethylsilane (ATMS) has been the most well-studied, with reports of Lewis and Brønsted acids effectively catalyzing the reaction.19−29 The coupling of alkenyl silanes with alcohols was originally reported using InCl3 as a catalyst.30 Subsequently, Niggemann and Gandon reported that Ca(NTf2)2 catalyzes the reaction when alkenyl silane and alkenyl boronic acid nucleophiles are used.31,32 Fisher and Bolshan have reported on the HBF4-mediated coupling of alkenyl- and alkynyl-potassium trifluoroborate salts with benzhydrol alcohols.33 In a subsequent paper, allylation of similar alcohol substrates was achieved using allyl potassium trifluoroborates with sub-stoichiometric acid loading.34 This method is one of the few examples that is able to demonstrate the effective alkynylation of alcohols, along with those that employ InCl3 and I2 as catalysts.26,35

Due to their mild and “tunable” Lewis acid character, arylboronic acids display a wide range of functional group tolerance in comparison to harsher Lewis and Brønsted acids.36−38 We have previously reported on the catalytic activation of allylic alcohols for Friedel–Crafts reactions with electron-rich arenes using pentafluorophenylboronic acid.38 Subsequently, in collaboration with Hall, we demonstrated that ferrrocenium boronic acid hexafluoroantimonate salt was a superior catalyst for the activation of electron-poor benzylic alcohols in Friedel–Crafts reactions.39 We have since directed our efforts to exploit the ability of boronic acids to catalytically activate hydroxy groups in the development of other synthetically useful transformations. Herein, we report a general catalytic method for the deoxygenative coupling of allylic, propargylic, and benzylic alcohols with a variety of borate and silane nucleophiles.

Results and Discussion

Our previous work on boronic acid catalysis (BAC) revealed that ferrocenium boronic acid hexafluoroantimonate (BAC-1) in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) is capable of sufficiently activating benzylic alcohols for Friedel–Crafts arylation.39 We evaluated the same conditions for the deoxygenative allylation of benzhydrol alcohol (1a) with allyl boronic acid (2a), allyl potassium trifluoroborate (2b), and ATMS (2c) at 70 °C (Table 1).

Table 1. Reaction Optimizationa.

| entry | catalyst | solvent | [M] | temp (°C) | yield (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BAC-1 | HFIP | B(OH)2 | 70 | n.r |

| 2 | BAC-1 | HFIP | Bpin | 70 | n.r |

| 3 | BAC-1 | HFIP | BF3K | 70 | 55% |

| 4b | BAC-1 | HFIP | TMS | 70 | 93% |

| 5b | BAC-1 | CH3CN | TMS | 70 | n.r |

| 6b | BAC-1 | DCM | TMS | 70 | n.r |

| 7b | BAC-1 | DCE | TMS | 70 | n.r |

| 8b | BAC-1 | toluene | TMS | 70 | n.r |

| 9 | BAC-1 | HFIP | TMS | rt | 91% |

| 10 | BAC-2 | HFIP | TMS | rt | 36% |

| 11 | BAC-3 | HFIP | TMS | rt | 17% |

| 12 | HFIP | TMS | rt | 12% |

The use of the free boronic acid (2a) as a nucleophile was unsuccessful at producing the desired product (3a, entry 1). However, the use of the trifluoroborate analogue 2b resulted in the formation of the desired product in a 55% yield (entry 2), and the use of ATMS (2c) afforded the desired product in a 93% yield (entry 3). Evaluation of various solvents determined that HFIP was necessary to achieve sufficient reactivity (entries 5–8). Since no significant difference in yield was observed when the reaction was run at ambient temperature, we proceeded with this as the standard temperature for the reaction. Other boronic acids that have been shown to activate benzylic alcohols were evaluated and resulted in the formation of the desired product in diminished yield (entries 10 and 11). A control experiment run in the absence of a boronic acid catalyst was performed at ambient temperature, and 3a was obtained in a yield of only 12% (entry 12), presumably due to the ability of HFIP to stabilize carbocation intermediates.

We initiated our examination of the scope with respect to the nucleophilic organopotassium trifluoroborate and organosilane coupling partners under the optimized reaction conditions using benzhydryl alcohol 1a as a prototypical alcohol substrate (Table 2). By direct comparison (see, for example, results for 3a and 3e), organosilane nucleophiles were found to generally out-perform trifluoroborates, resulting in increased yields and a greater diversity of substrate scope. For this reason, we focused mainly on the use of organosilane nucleophiles. Products E-3b and Z-3b were obtained in good yields and with high diastereoselectivity using E- and Z-phenylvinyltrimethylsilane, respectively. The geometry of the double bond in each case is conserved with respect to the starting material. In order to demonstrate the practical utility of our method, E-3b was also prepared on a 1.0 g scale and isolated in comparable yield (74%) to that for the small-scale reaction. Unfortunately, the use of 1-phenylvinyl potassium trifluoroborate as a nucleophile did not result in the formation of product 3c.

Table 2. Scope of the Reaction with Various Borate and Silane Nucleophilesa,b,c.

Reactions performed with 1a (0.5 mmol), nucleophile 2 (0.6 mmol), HFIP (2.0 mL), and BAC-1 (0.05 mmol) at rt for 16 h.

Isolated yields.

Crude residue was purified by flash chromatography; see Supporting Information for details.

Reaction performed on a 1.0 g scale (benzhydryl alcohol); see Supporting Information for details.

A complex mixture of products was obtained as determined by the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude material.

Alkynyl silanes were also found to be effective nucleophiles in the reaction. Product 3e was obtained in excellent yield. However, when the non-silyl alkynyl substituent is less capable of stabilizing the presumed β-cation intermediate (vide infra), slightly diminished yields were obtained (3f), and no product was observed for the reaction with unsubstituted trimethylsilylacetylene (3g). Allene product 3d was isolated in very good yield when propargyl trimethylsilane was used. Interestingly, when a 2-trimethylsilyl-substituted indole was used as a substrate, substitution occurs exclusively at the 2-position via desilylation (3h). This is complementary to the substitution at the 3-position that is normally observed for analogous Friedel–Crafts reactions of unsubstituted N-methylindole.39 In contrast to this result, 2-trimethylsilyltetrahydropyran undergoes substitution at the 3-position (3i). In this case, the presumed β-silyl carbon undergoes addition with proton elimination, while the silyl functional group is retained in the product. This suggests that carbocation stabilization by the α-lone pair is superior to that of silicon.40

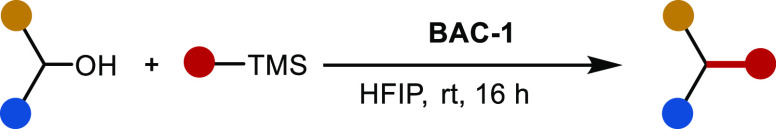

We next surveyed the scope of the reaction with respect to the alcohol coupling partner (Table 3). Beginning with bis-benzylic alcohols, we observe that species with electron-donating (E-4a, and E-4b) and mildly electron-withdrawing (E-4c and E-4d) substituents afford the desired products in high to near-quantitative yields. However, when a strong electron-withdrawing substituent is present, product E-4e is obtained in only trace quantities. Following a similar trend, electron-rich primary benzylic alcohols are well tolerated, affording the desired products in moderate yields with a variety of organosilane nucleophiles (4f–4h). Gratifyingly, in all cases where E- or Z-alkenylsilanes are used as nucleophiles, stereochemistry was completely conserved in the products. When electron-neutral or electron-poor primary benzylic alcohols are used, no product is obtained. Furthermore, secondary benzylic alcohols bearing an α-methyl substituent performed poorly in the reaction (4k and 4l), presumably due to the competitive E1 reaction of the alcohol substrates.

Table 3. Scope of the Reaction with Various Alcoholsa,b,c.

Reactions performed with 1 (0.5 mmol), nucleophile 2 (0.6 mmol), HFIP (2.0 mL), and BAC-1 (0.05 mmol) at rt for 16 h.

Isolated yields.

Crude residue was purified by flash chromatography; see Supporting Information Experimental section for details.

No reaction.

Allylic alcohols with an additional stabilizing α-phenyl substituent are competent substrates with alkenyl-, alkynyl-, and aryl-silane nucleophiles (4l, 4o, and 4r). Removing the additional α-stabilizing group results in diminished yields with alkenylsilanes (4m and 4n), and the unconjugated enyne products (4p and 4q) were not obtained. However, similar products were successfully prepared with the use of secondary and tertiary propargylic alcohols and alkenylsilanes41 (4s and 4t), albeit in modest yields. Secondary propargylic alcohols with electron-donating substituents afford undesired Meyer–Schuster rearrangement products.42

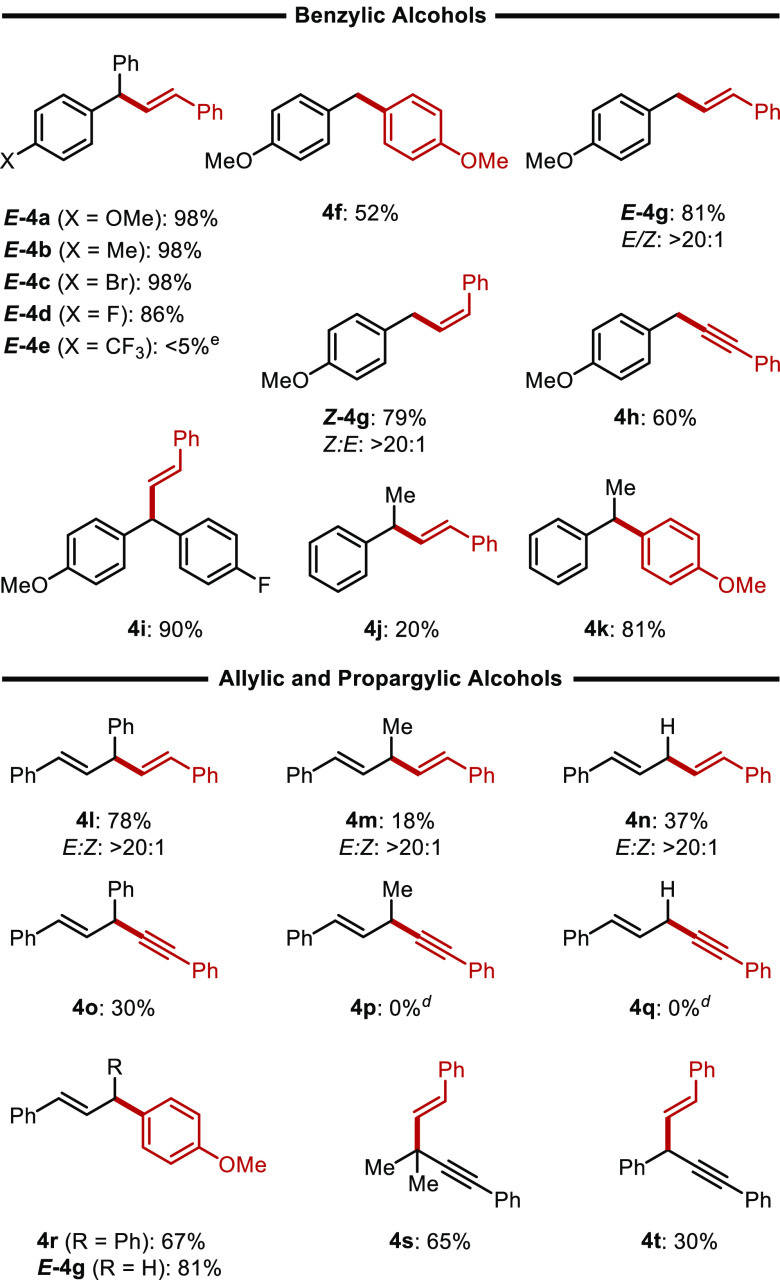

Given the commercial availability, the similarity of the reagents, and the potential utility of the expected products, we next applied our optimized conditions to the coupling of azidotrimethylsilane (ATS) and trimethylsilyl cyanide (TMSCN) with a variety of alcohol substrates. Gratifyingly, use of the azide reagent as a nucleophile generally produced organic azides efficiently and in good yields (Table 4). Triarylmethanols afforded the desired products 5a and 5b in excellent yields of 86 and 88%, respectively. A variety of substituted benzhydrol alcohols were prepared and subject to the boronic acid catalyzed reaction conditions. Those with electron-donating, as well as electron-withdrawing substituents are well tolerated, affording the desired products (5c–5i) in good to excellent yields. Conversely, and similarly to our results with carbon-based silane nucleophiles, only monosubstituted benzylic alcohols bearing electron-donating substituents afforded the expected products (e.g., 5j); unactivated and deactivated benzylic alcohols were found to be completely unreactive (5k and 5l). When 1-phenylethanol was used as a substrate, the reaction also failed to afford any of the desired product 5m. Various allylic alcohols that we tested produced the expected products, with only the Z-stereoisomers produced (where applicable), albeit in very modest yields (5n–5r).

Table 4. Scope of the Reaction with ATSa,b,c.

Reactions were performed in a sealed microwave tube with 1 (0.5 mmol), ATS (0.6 mmol), HFIP (2.0 mL), and BAC-1 (0.05 mmol) at 80 °C for 16 h.

Isolated yields.

Crude residue was purified by flash chromatography; see Supporting Information for details.

No reaction.

Unfortunately, TMSCN is a much less competent nucleophile, participating with only bis-benzylic alcohol coupling partners (Table 5). Attempts to prepare bis-benzylnitriles using unsubstituted (6a), electron-rich (6b and 6c), or moderately electron-poor (6d and 6e) benzhydrol alcohols resulted in only very modest yields of the desired products. Other secondary benzylic alcohols failed to react entirely (e.g., 6f).

Table 5. Scope of the Reaction of Benzyl Alcohols with TMSCNa,b,c.

Reactions were performed in a sealed microwave tube with 1 (0.5 mmol), TMSCN (0.6 mmol), HFIP (2.0 mL), and BAC-1 (0.05 mmol) in an ambient atmosphere at 80 °C for 16 h.

Isolated yields.

Crude residue was purified by flash chromatography; see Supporting Information for details.

No reaction.

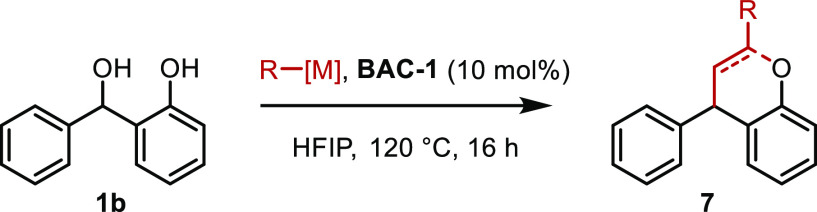

During our examination of the scope of the reactions of the various carbon-based nucleophiles, we observed some interesting divergent reactivities (Table 6). When treated with potassium allyltrifluoroborate, ortho-hydroxy-substituted benzhydrol alcohol 1b undergoes direct addition to afford the expected product 7a. However, when 1b is treated with an allylic silane, substituted benzopyran product 7b is obtained in 80% yield. This product could be the result of initial direct addition, followed by trapping of an intermediate carbocation or by a formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition of the alkene with an in situ generated ortho-quinone methide intermediate.43 These possible mechanistic pathways are currently being explored further in our laboratory.

Table 6. Divergent Reactivity of ortho-Hydroxy Benzhydrol Alcohola,d,e.

Reactions performed in a sealed microwave tube with 1b (0.5 mmol), HFIP (2.0 mL), and BAC-1 (0.05 mmol) under an ambient atmosphere at 120 °C for 16 h.

Allyl potassium trifluoroborate (0.6 mmol) was used.

ATMS (0.6 mmol) was used.

Isolated yields.

Crude residue was purified by flash chromatography; see Supporting Information for details.

We next sought to investigate the mechanism of the reaction with particular emphasis on the high stereochemical retention observed in the preparation of Z-3b and related examples. Given the similarity of the alcohol substrates, the conditions for this reaction, and our previously reported ferrocenium boronic acid catalyzed Friedel–Crafts reaction, we propose a similar mechanism for the formation of the solvated benzylic carbocation (in A) from 1a (Scheme 1).39 Based on a previously proposed but as yet unvalidated explanation for the observed retention of stereochemistry,30 the nucleophilic attack of Z-phenylvinyltrimethylsilane on the resulting carbocation in A results in the formation of a β-silyl-stabilized carbocation Int-1. Borate-assisted elimination of the trimethylsilyl group results in the formation of the Z-alkene and regeneration of the active catalyst species.

Scheme 1. Mechanistic Proposal for Stereochemical Retention in the Reaction of Z-Vinylsilanes.

In order to validate this mechanistic proposal for the stereochemical course of the reaction, we initiated computational studies on the nucleophilic addition process. The stereoselective formation of Z-3b is illustrative (for calculations on, and a discussion of the analogous formation of E-3b, see Supporting Information). It has previously been proposed that the addition of an alkenylsilane to in situ generated carbocations is favorable due to the formation of a stabilized β-silyl cation, which requires the carbocation-bearing carbon atom and the silicon atom to be coplanar, restricting rotation.30 Our preliminary calculations determined that this did not fully explain the retention of the carbon–carbon double bond geometry. Further computational studies to investigate the nucleophilic addition process employing the method B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) with an SMD solvation model were conducted (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Calculated Energies for the Stereoselective Formation of Z-3b.

The rotational barrier (TS2) has been estimated from a relaxed potential energy surface scan.

All energies are calculated relative to the initial state of the reactants (0 kJ/mol). It was found that after the addition of the Z-alkenylsilane nucleophile to a diphenylmethyl cation (A to INT1), desilylation is barrierless and happens instantaneously as the zwitterionic borate catalyst approaches the intermediate species to form Z-3b. On the other hand, 180° rotation of the relevant C–C bond from INT1 to INT2 requires 78.4 kJ/mol.

Conclusions

In summary, we have reported on a general strategy for the direct deoxygenative coupling of π-activated alcohols with a variety of carbon- and nitrogen-based borate and silane nucleophiles. The regioselectivity and stereoselectivity of this reaction are generally high, and the latter can be controlled by the structure of the silane nucleophile. This approach demonstrates high chemoselectivity, providing orthogonal reactivity to conventional cross-coupling. In conjunction, these attributes provide an attractive approach to the synthesis of a variety of structures including functionalized diarylmethanes, species commonly found in pharmaceutically relevant molecules.44−47 Computational results, which are in agreement with our experimental work, provide the first empirical evidence for the stereochemical retention observed when E- or Z-alkenylsilanes are used as nucleophiles.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (Discovery grants to J.A.M. and J.W.H.). J.J.B. thanks NSERC for a CGS-M scholarship. D.M.R. thanks NSERC for an Undergraduate Student Research Award.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c00463.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Corbet J.-P.; Mignani G. Selected patented cross-coupling reaction technologies. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 2651–2710. 10.1021/cr0505268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.; Fu G. C. Transition metal–catalyzed alkyl-alkyl bond formation: another dimension in cross-coupling chemistry. Science 2017, 356, eaaf7230 10.1126/science.aaf7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Castillo P.; Buchwald S. L. Applications of palladium-catalyzed C–N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12564–12649. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Bulger P. G.; Sarlah D. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction in Total Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4442–4489. 10.1002/anie.200500368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J. M.; König B. Reductive deoxygenation of alcohols: catalytic methods beyond Barton–McCombie deoxygenation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 7017–7027. 10.1002/ejoc.201300657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore D. C.; Castro L.; Churcher I.; Rees D. C.; Thomas A. W.; Wilson D. M.; Wood A. Organic synthesis provides opportunities to transform drug discovery. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 383–394. 10.1038/s41557-018-0021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable D. J. C.; Dunn P. J.; Hayler J. D.; Humphrey G. R.; Leazer Jr J. L.; Linderman R. J.; Lorenz K.; Manley J.; Pearlman B. A.; Wells A.; et al. Key Green Chemistry Research Areas - A Perspective from Pharmaceutical Manufacturers. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 411–420. 10.1039/b703488c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel T.; Brunne R. M.; Müller H.; Reichel F. Statistical Investigation into the Structural Complementarity of Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 643–647. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl P.; Schuhmann T. A systematic cheminformatics analysis of functional groups occurring in natural products. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1258–1263. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b01022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.-T.; Zhang Z.-Q.; Liang J.; Liu J.-H.; Lu X.-Y.; Chen H.-H.; Liu L. Copper-catalyzed cross-coupling of nonactivated secondary alkyl halides and tosylates with secondary alkyl grignard reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11124–11127. 10.1021/ja304848n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; MacMillan D. W. C. Alcohols as latent coupling fragments for metallaphotoredox catalysis: sp3–sp2 cross-coupling of oxalates with aryl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13862–13865. 10.1021/jacs.6b09533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y.; Chen H.; Sessler J. L.; Gong H. Zn-mediated fragmentation of tertiary alkyl oxalates enabling formation of alkylated and arylated quaternary carbon centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 820–824. 10.1021/jacs.8b12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative arylation of alcohols. Nature 2021, 598, 451–456. 10.1038/s41586-021-03920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intermaggio N. E.; Millet A.; Davis D. L.; MacMillan D. W. C. Deoxytrifluoromethylation of Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11961–11968. 10.1021/jacs.2c04807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Z.; Sakai H. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Alcohols as Alkylating Agents: Photoredox-Catalyzed Conjugate Alkylation via In Situ Deoxygenation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207150 10.1002/anie.202207150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Wang K.; Jin W.; Xie H.; Qi L.; Liu X.; Shu X. Dynamic Kinetic Cross-Electrophile Arylation of Benzyl Alcohols by Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 513–523. 10.1021/jacs.0c12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Sun W.; Wang X.; Li L.; Zhang Y.; Li C. Electrochemically Enabled, Nickel-Catalyzed Dehydroxylative Cross-Coupling of Alcohols with Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3536–3543. 10.1021/jacs.0c13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; MacMillan D. W. C. Alcohols as Latent Coupling Fragments for Metallaphotoredox Catalysis: Sp3-Sp2 Cross-Coupling of Oxalates with Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13862–13865. 10.1021/jacs.6b09533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trillo P.; Baeza A.; Nájera C. Fluorinated Alcohols as Promoters for the Metal-Free Direct Substitution Reaction of Allylic Alcohols with Nitrogenated, Silylated, and Carbon Nucleophiles. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7344–7354. 10.1021/jo301049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M.; Gevorgyan V. B. (C6F5)3-Catalyzed Allylation of Secondary Benzyl Acetates with Allylsilanes. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2705–2707. 10.1021/ol016300i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Z. P.; Yang W. Z.; Yang R. F.; Yu J. L.; Li J. P.; Liu H. J. BiCl3-Catalyzed Propargylic Substitution Reaction of Propargylic Alcohols with C-O-S- and N-Centered Nucleophiles. Chem. Commun. 2006, 37, 3352–3354. 10.1002/chin.200652039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana Kumar G. G. K. S.; Laali K. K. Facile Coupling of Propargylic, Allylic and Benzylic Alcohols with Allylsilane and Alkynylsilane, and Their Deoxygenation with Et3SiH, Catalyzed by Bi(OTf)3 in [BMIM] [BF4] Ionic Liquid (IL), with Recycling and Reuse of the IL. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 7347–7355. 10.1039/c2ob26046h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassner A.; Bandi C. R. High-Yielding and Rapid Carbon–Carbon Bond Formation from Alcohols: Allylation by Means of TiCl4. Synlett 2013, 24, 1275–1279. 10.1055/s-0033-1338746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Cui Z.; Wang J.; Liu Z. Efficient and Mild Iron-Catalyzed Direct Allylation of Benzyl Alcohols and Benzyl Halides with Allyltrimethylsilane. Synth. Commun. 2010, 40, 2042–2046. 10.1080/00397910903219393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M.; Saito T.; Ueba M.; Baba A. Direct Substitution of the Hydroxy Group in Alcohols with Silyl Nucleophiles Catalyzed by Indium Trichloride. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1414–1416. 10.1002/anie.200353121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T.; Nishimoto Y.; Yasuda M.; Baba A. Direct Coupling Reaction between Alcohols and Silyl Compounds: Enhancement of Lewis Acidity of Me3SiBr Using InCl3. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8516–8522. 10.1021/jo061512k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šolić I.; Seankongsuk P.; Loh J. K.; Vilaivan T.; Bates R. W. Scandium as a Pre-Catalyst for the Deoxygenative Allylation of Benzylic Alcohols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 119–123. 10.1039/c7ob02219k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Li X.; Zhu X.; Li M.; Zhou L.; Song X.; Liang Y. Lewis Acid Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Coupling of Tertiary Propargylic Alcohols with Quinoline N-Oxides. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1697–1704. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estopiñá-Durán S.; Mclean E. B.; Donnelly L. J.; Hockin B. M.; Taylor J. E. Arylboronic Acid Catalyzed C-Alkylation and Allylation Reactions Using Benzylic Alcohols. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7547–7551. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto Y.; Kajioka M.; Saito T.; Yasuda M.; Baba A. Direct Coupling of Alcohols with Alkenylsilanes Catalyzed by Indium Trichloride or Bismuth Tribromide. Chem. Commun. 2008, 47, 6396–6398. 10.1039/b816072d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer V. J.; Niggemann M. Calcium-Catalyzed Direct Coupling of Alcohols with Organosilanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3671–3674. 10.1002/ejoc.201100231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebœuf D.; Presset M.; Michelet B.; Bour C.; Bezzenine-Lafollée S.; Gandon V. CaII-Catalyzed Alkenylation of Alcohols with Vinylboronic Acids. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 11001–11005. 10.1002/chem.201501677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K. M.; Bolshan Y. Brønsted Acid-Catalyzed Reactions of Trifluoroborate Salts with Benzhydrol Alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 12676–12685. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orizu I.; Bolshan Y. A General Brønsted Acid-Catalyzed Allylation of Benzhydrol Alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5798–5800. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.11.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav J. S.; Reddy B. S.; Thrimurtulu N.; Reddy N. M.; Prasad A. R. The First Example of Alkynylation of Propargylic Alcohols with Alkynylsilanes Catalyzed by Molecular Iodine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 2031–2033. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. G.Structure, Properties, and Preparation of Boronic Acid Derivatives: Overview of Their Reactions and Applications. In Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis, Medicine, and Materials, Hall D. G., Ed. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; pp.1−133. 10.1002/9783527639328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. G. Boronic Acid Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3475–3496. 10.1039/c9cs00191c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin J. A.; Hosseini H.; Krokhin O. V. Boronic Acid Catalyzed Friedel-Crafts Reactions of Allylic Alcohols with Electron-Rich Arenes and Heteroarenes. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 959–962. 10.1021/jo9023073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo X.; Yakiwchuk J.; Dansereau J.; McCubbin J. A.; Hall D. G. Unsymmetrical Diarylmethanes by Ferroceniumboronic Acid Catalyzed Direct Friedel-Crafts Reactions with Deactivated Benzylic Alcohols: Enhanced Reactivity Due to Ion-Pairing Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9694–9703. 10.1021/jacs.5b05076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin J. A.; Nassar C.; Krokhin O. V. Waste-Free Catalytic Propargylation/Allenylation of Aryl and Heteroaryl Nucleophiles and Synthesis of Naphthopyrans. Synthesis 2011, 2011, 3152–3160. 10.1055/s-0030-1260146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook M. A.; Neuy A. The .beta.-effect: changing the ligands on silicon. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 3609–3616. 10.1021/jo00298a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H.; Lejkowski M.; Hall D. G. Mild and Selective Boronic Acid Catalyzed 1,3-Transposition of Allylic Alcohols and Meyer-Schuster Rearrangement of Propargylic Alcohols. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1305–1310. 10.1039/c1sc00140j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; He X.; Yang Q.; Boucherif A.; Xuan J. Recent Advances in Organocatalytic Asymmetric Cycloaddtion Reactions Through Ortho-Quinone Methide Scaffolds. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1233–1250. 10.1002/ajoc.202100141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S.; Panda G. Synthetic methodologies of achiral diarylmethanols, diaryl and triarylmethanes (TRAMs) and medicinal properties of diaryl and triarylmethanes-an overview. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 28317–28358. 10.1039/c4ra01341g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari L.; Merlotti D.; Martini G.; Nuti R. Lasofoxifene: a third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2006, 15, 1091–1103. 10.1517/13543784.15.9.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner E. S. Tolterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder: a review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005, 6, 653–666. 10.1517/14656566.6.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder R. M.; Brogden R.; Sawyer P. R.; Speight T.; Spencer R.; Avery G. Butorphanol: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 1976, 12, 1–40. 10.2165/00003495-197612010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.