PURPOSE:

There has been limited study of the implementation of suicide risk screening for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) as a part of routine care. To address this gap, this study assessed oncology providers' and professionals' perspectives about barriers and facilitators of implementing a suicide risk screening among patients with HNC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

All patients with HNC with an in-person visit completed a suicide risk screening on an electronic tablet. Patients reporting passive death wish were then screened for active suicidal ideation and referred for appropriate intervention. Interviews were conducted with 25 oncology providers and professionals who played a key role in implementation including nurses, medical assistants, patient access representatives, advanced practice providers, physicians, social workers, and informatics staff. The interview guide was based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed for themes.

RESULTS:

Participants identified multilevel implementation barriers, such as intervention level (eg, patient difficulty with using a tablet), process level (eg, limited nursing engagement), organizational level (eg, limited clinic Wi-Fi connectivity), and individual level (eg, low clinician self-efficacy for interpreting and acting upon patient-reported outcome scores). Participants noted facilitators, such as effective care coordination across nursing and social work staff and the opportunity for patients to be screened multiple times. Participants recommended strengthening patient and clinician education and providing patients with other modalities for data entry (eg, desktop computer in the waiting room).

CONCLUSION:

Participants identified important intervention modifications that may be needed to optimize suicide risk screening in cancer care settings.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with cancer are at increased risk for suicide compared with the general population.1-5 A 2019 study estimated that suicide rates are up to four times higher among individuals with cancer compared with individuals without cancer.5 Suicide risk occurs along the cancer care continuum, from new diagnosis through survivorship.1,6-10 Demographics such as lower income and rural residence are associated with higher suicide risk.5,11,12 Clinical factors, such as depression, lower quality of life, thoughts of suicidal ideation, prior suicide attempt, and certain cancer types, are also associated with increased suicide risk.5,12-16 Compared with patients with other cancers, patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) are twice as likely to die from suicide.14 Several factors contribute to higher suicide risk among patients with HNC, including substance use history, chronic pain, mood disorders, and cancer treatment and type.17-20 Despite this elevated suicide risk, there has been limited study of interventions designed to prevent suicide among patients with HNC.

Routine suicide risk screening and follow-up among patients with cancer can reduce suicide rates and improve access to psychosocial care21; however, routine screening programs are underused in cancer care and for patients with HNC specifically.22 Most studies to date on routine suicide risk screening among patients with cancer have focused on estimating prevalence and evaluating the impact of screening on suicide rates.21,23 There have been limited studies examining implementation, information necessary for integrating suicide screening into routine cancer care delivery. Studies examining implementation of other patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) suggest there are multilevel implementation barriers, such as lack of leadership support, low clinician self-efficacy for score interpretation, and limited patient engagement with PROM completion.24-26 Studies on suicide risk screening in other clinical settings (eg, emergency departments) suggest there are additional barriers for assessing suicide risk, such as care coordination challenges, and clinician and patient hesitancy to discuss mental health concerns.21,27-31 Therefore, studies are needed to identify barriers and facilitators of suicide risk screening programs in cancer care delivery.

To address this gap, this study assessed oncology providers' and professionals' perspectives about barriers and facilitators of implementing a suicide risk assessment among patients with HNC at Moffitt Cancer Center (Moffitt), a National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Information from this study can support future programs and policies aimed at expanding suicide risk screening among patients with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Suicide Risk Screening Intervention

Starting in February 2021, all patients with HNC with an in-person visit completed a suicide risk screening on an electronic tablet. The screening assessed passive death wish through item 9 on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which asks, “How often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way over the past two weeks?”32 The PHQ-9 item 9 was selected, given its brevity and past research demonstrating the association between passive death wish and suicide risk.33-36 Patients reporting any response other than no thoughts at all about passive death wish were automatically referred to social work for active suicidal ideation (eg, thoughts and plans for self-harm) screening using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale,37,38 which has been validated in clinical settings (eg, Veterans Health Affairs).39,40 Patients who identified as having active suicidal ideation received additional intervention (eg, suicide safety plan). The screening assessed distress using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer41 and additional symptoms using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System.42 The PROMs were selected by Moffitt's Patient-Reported Information and Outcomes committee, an interdisciplinary group of clinicians, social workers, informatics staff, and researchers. The committee used three criteria for measure selection: ease of implementation in a clinical setting, prior implementation in a cancer center (eg, PHQ-9 item 9 is used by another cancer center),21 and measure reliability and validity in English and Spanish since the tool was made available in both languages.

Data Collection

The research team developed one semistructured interview guide on the basis of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) that identifies multilevel barriers and facilitators to intervention implementation (Data Supplement, online only).43 The guide assessed organizational-level (eg, staffing), process-level (eg, training), intervention-level (eg, usability), and individual-level (eg, self-efficacy for using scores) factors affecting implementation.

The research team e-mailed oncology providers and professionals who played a key role in implementation including patient access representatives (PARs) who provided patients with a tablet to complete the screening, medical assistants (MAs) who helped patients complete the screening (eg, use the tablet), nurses who reviewed the data and ensured appropriate clinical action was taken, social workers who screened for active suicidal ideation among patients reporting passive death wish, advanced practice providers (APPs) and physicians who were responsible for addressing concerning symptom scores that could not be managed by nursing staff, and informatics staff who were responsible for developing and overseeing implementation of the cloud-based application that allowed for in-clinic data collection on tablets and electronic health record (EHR) integration. The research team contacted all individuals involved with implementation and received a response from 25 out of 49 individuals (51% response rate). Common reasons for declining to participate were lack of time and competing priorities. Two individuals trained in qualitative methods (C.G. and A.M.) conducted the interviews via videoconference (mean time: 31.4 minutes; standard deviation: 12.3 minutes). Participants provided verbal informed consent before the interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were conducted during the first three months of implementation (February-April 2021) so that information gathered from the interviews could inform intervention refinement. Participants did not receive any incentives (eg, gift cards).

Qualitative Data Analysis

The research team used a hybrid approach to analyze the qualitative data44,45 by developing an initial codebook on the basis of CFIR constructs and additional codes on the basis of patterns that emerged from the data. The transcripts were coded by two independent coders (C.G. and A.M.) using NVivo 12 Plus (Burlington, MA) until a consensus in coding was achieved. Once agreement was established, the coders independently coded the remaining transcripts. The coders set a threshold for assessing data saturation as the point at which no new themes were generated from a given transcript.46 Saturation was reached at 25 interviews; therefore, we did not recruit additional participants. We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research for study description and reporting.47 This study was deemed exempt from oversight by Moffitt's Institutional Review Board of Record, Advarra. Human investigations were performed after exemption was obtained.

RESULTS

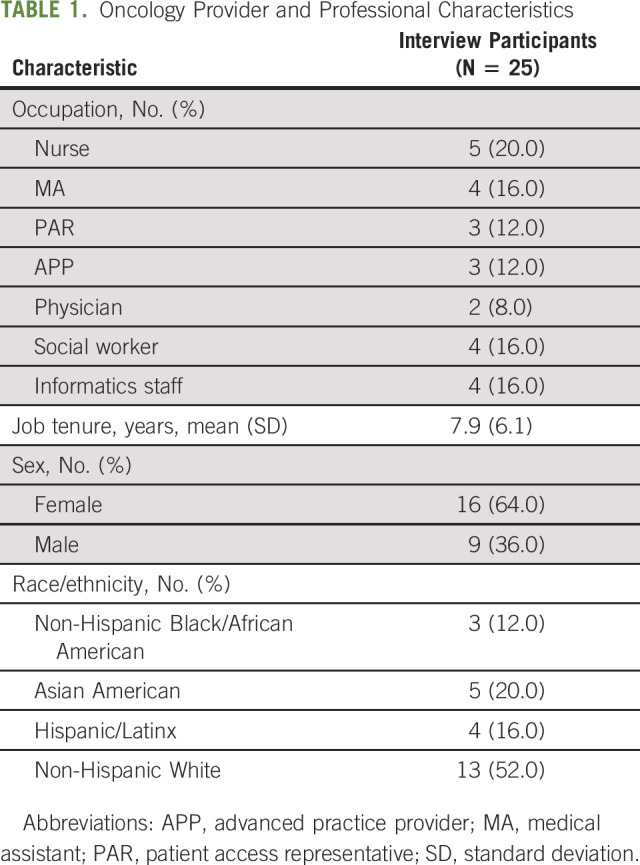

Interviews (N = 25) were conducted with nurses (20%), MAs (16%), PARs (12%), APPs (12%), physicians (8%), social workers (16%), and informatics staff (16%; Table 1). On average, participants had worked for Moffitt 7.9 years (standard deviation: 6.1). Participants described implementation barriers and facilitators that fell into four CFIR domains: (1) intervention characteristics; (2) process; (3) organizational characteristics; and (4) individual characteristics. Illustrative quotations are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Oncology Provider and Professional Characteristics

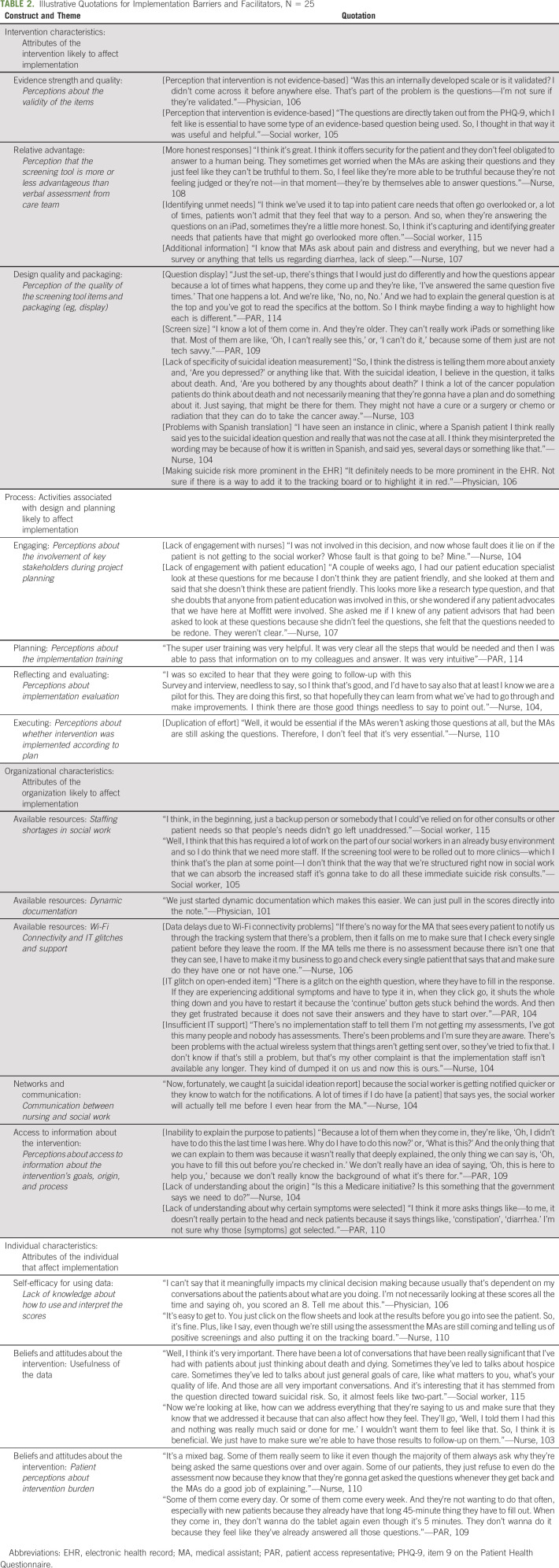

TABLE 2.

Illustrative Quotations for Implementation Barriers and Facilitators, N = 25

Intervention Characteristics

Participants indicated that patients may feel more comfortable sharing sensitive information electronically and may be more honest in their responses than if the information were assessed verbally. Second, the intervention provided care team members with additional information that was not available before implementation and identified unmet patient needs (eg, unmanaged pain) that may have otherwise gone unaddressed. Social work staff also appreciated the use of evidence-based measures, such as the PHQ-9. There was disagreement, however, about the evidence strength for the intervention; physician participants indicated lack of familiarity with the measures and questioned whether the measures were validated.

Oncology providers and professionals identified intervention characteristics that served as implementation barriers. Using a tablet to collect suicide risk information required patients to be able to read text with a small font size on a small screen and have sufficient dexterity to type on the tablet keypad. Participants explained that this was particularly challenging for some older adults and adults with arthritis. Participants indicated concerns about the PHQ-9 item 9 question that combines thoughts about death and thoughts of hurting yourself in the same item. Participants thought it may be beneficial to distinguish between these responses to prioritize patients for active suicidal ideation screening (eg, patients reporting thoughts of self-harm may need to be seen more quickly than patients reporting thoughts about death).

Implementation Process

Nurses, MAs, PARs, and social work staff described feeling well prepared for implementation and valued the train-the-trainer format that allowed team members to train their colleagues who were unable to attend the training on the suicide risk screening tool. There was a lack of consensus about the training, however; APPs and clinicians reported lack of familiarity with the suicide risk screening tool and expressed a desire for more training.

Participants identified areas where the implementation process encountered challenges, such as double documentation and lack of stakeholder engagement. Before suicide risk screening implementation, distress was verbally assessed by MAs. When the suicide risk tool was implemented, MAs were asked to discontinue verbally screening patients for distress; however, some MAs continued to verbally screen for distress. This led to double-documentation of distress and confusion among the clinic team when conflicting distress scores for the same patient were reported. Nursing staff also expressed concerns that most of the responsibility for implementation fell on nurses who were not included in the process for deciding how the intervention would be designed and implemented. Nurses also felt that patient education specialists did not have the opportunity to review the suicide risk screening tool, which may have improved intervention usability (eg, small font size).

Organizational Factors

Interviewees indicated that coordination across social work and nursing staff was a key facilitator of implementation. Furthermore, interviewees described that social work staff were proactive in communicating with nursing staff anytime a referral was received for a patient reporting passive death wish. APPs and physicians also indicated that the ability to automatically pull PHQ-9 and other PROM scores (eg, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System) into the provider note made documentation easier.

Although it was uncommon, there were a few instances where participants noted challenges with Wi-Fi connectivity in the clinic. When internet was unavailable due to poor Wi-Fi connectivity, several problems occurred, such as patient data being lost as they were entered into the tablet application, and failure of the data to upload into the EHR in real time. As a result, nurses described having to check the EHR multiple times to see whether the data were available or asking the patient to complete the screening a second time. Participants also described confusion about the intervention purpose. PARs and MAs described how their lack of understanding about the overall purpose made it difficult for them to answer patients' questions about why the information was being collected or how it was being used. APPs and physicians, who were less directly involved with implementation, described limited understanding of the process (eg, who was responsible for data collection, where to locate the data within the EHR, and what symptoms were collected).

Individual Characteristics

Participants believed the data were useful for starting conversations around mental health concerns and for eliciting additional information about patient concerns (eg, advanced care planning). Interviewees appreciated that there were multiple opportunities for patients to be screened (eg, available at each visit). There were some participants, however, who cited this as a barrier and indicated that patients found it burdensome to complete suicide risk screening at each visit. Participants shared that some patients refused to complete it because the purpose of the assessment was not clear. Social workers and nursing staff reported feeling confident in their ability to interpret the data and act upon the scores (eg, what to do when a patient reports a high pain score). Conversely, APPs and physicians tended to report feeling unsure about how to interpret the scores or use the data in their clinical practice, which served as a barrier to communicating with patients about their scores.

Recommendations

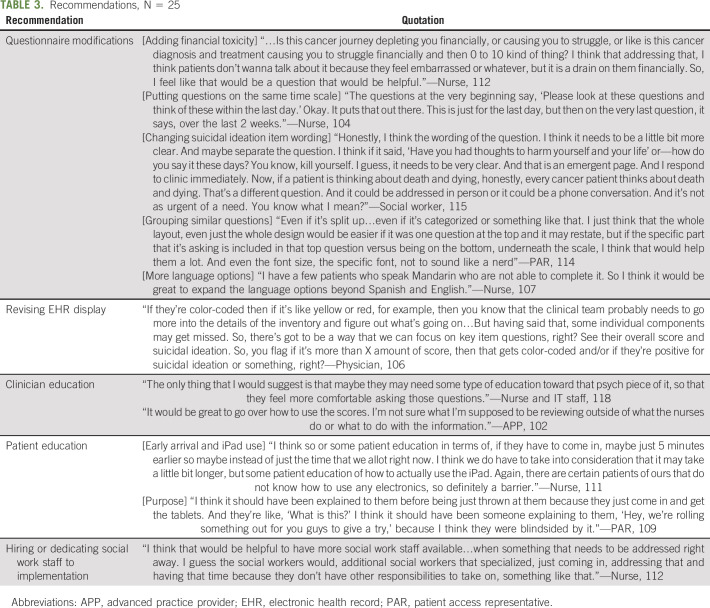

Participants recommended revising the screening tool, providing alternative options for data entry, changing the EHR display, strengthening patient and provider education, and hiring additional staff (Table 3). Participants suggested increasing the font size of the screening questions and bolding or underlining the symptom being assessed (eg, pain) to make it easier for patients to distinguish between each item. Participants recommended offering the tool in additional languages beyond Spanish and English (eg, Mandarin) and adding additional items specific to HNC (eg, swallowing difficulty) and common among patients with cancer (eg, financial toxicity). Interviewees recommended giving patients who had difficulty using the tablet other ways to submit data, such as setting up a desktop computer in the waiting room. Participants suggested changing the EHR display so that positive suicidal ideation results were more prominent (eg, placement on dashboard) and concerning scores were color-coded (eg, pain score > 7 shown in red text).

TABLE 3.

Recommendations, N = 25

Interviewees highlighted the need for additional clinician training on how to interpret and act upon the scores and how to have conversations about suicidal ideation and other mental health concerns (eg, depression). Participants recommended more patient education about the purpose of data collection (why is this information being collected and how will it be used) and how to use the tablet (eg, how to use the on-screen keypad). Nurses and social work staff also recommended hiring additional social work staff to oversee suicide risk screening. Staff cited concerns that social work staff were being overburdened with implementation and would not have enough capacity to support scaling up suicide risk screening to other clinics.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our study participants found the information collected by the suicide screening tool to be valuable for identifying patients with unmet needs and for starting conversations around mental health concerns and unmanaged symptoms. Participants identified factors that supported implementation (eg, care coordination among nursing and social work staff) and important intervention modifications that may be needed to optimize suicide risk screening in cancer care settings, such as provider and patient education, and capture of HNC-specific symptoms.

Study findings suggest that clinician education is needed to support suicide risk screening implementation. Participants noted two training gaps, namely facilitating conversations around mental health and use of PROMs in clinical practice. Research has shown that suicide prevention training can increase clinicians' knowledge and self-efficacy for identifying and treating patients at risk for suicide.48-54 However, clinician suicide prevention training has been understudied in oncology. Consistent with prior research, our study found that clinicians reported low self-efficacy for using PROMs in clinical practice.55,56 To increase clinician self-efficacy for PROM implementation, researchers have recommended strategies, such as developing scripts for care providers to discuss PROM benefits with patients57 and training on how to interpret PROMs using real patient cases.58,59 Further studies are needed to test such approaches in the context of suicide risk screening.

Participants highlighted the importance of patient education about suicide risk screening. Similar to other PROM implementation studies, our participants described that lack of patient understanding about how to use technology (eg, tablets) and lack of understanding about the purpose of PROM collection served as implementation barriers.60,61 Studies have pilot-tested approaches such as developing marketing materials to educate patients on PROMs, involving patients in the co-design of PROM interventions, and empowering patients by providing access to easy-to-interpret visualizations of PROM scores.62-64 However, a recent systematic review found that patient engagement in PROM initiatives was rare.65 Further studies are needed to develop and test strategies to support patient education and engagement around suicide risk assessment.

Although the suicide risk screening tool was piloted in the HNC clinic, the tool was designed to include common cancer-related rather than disease-specific symptoms to ensure scalability across clinics. Therefore, the tool needs further refinement for patients with HNC. Participants in our study mentioned financial toxicity, swallowing difficulty, and taste changes as key symptoms to consider for patients with HNC. Prior studies demonstrate that patients with HNC are at increased risk for financial toxicity66,67 and employment loss after treatment because of long-term side effects, such as persistent speaking impairment.67-69 Research shows that financial hardship and employment loss are associated with suicide risk among US adults70,71; therefore, it may be valuable to assess for financial toxicity as part of a suicide risk screening program for patients with HNC. Our participants also suggested inclusion of symptoms that capture the physiologic impairment caused by HNC treatment, such as swallowing difficulty and taste changes, which contribute to poor quality of life and distress, and should be considered in future suicide risk screening among patients with HNC.72

Our study was conducted in a National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, where it may be easier to coordinate care across behavioral health and oncology teams because of colocation of services. We conducted this study within the first three months of suicide risk screening implementation; therefore, the findings may not be representative of later-stage implementation (eg, some barriers may have improved or worsened over time). Our study does not include the patient perspective, as it was beyond the scope of the current study; however, we plan to assess patient perspectives in the future. We focused on the clinician perspective to capture information on organizational- and process-level barriers, key considerations for implementation. Furthermore, our study is unable to compare approaches across cancer centers.21 For example, another cancer center screens for passive death wish before screening for active suicidal ideation.21 In other medical settings, other suicidal screening tools have been used (eg, Ask-Suicide-Screening Questions) that assess passive death wish and active suicidal ideation simultaneously.73 Future studies should compare suicide risk screening implementation across oncology settings. Additionally, this study was implemented in a HNC clinic. Research is needed to scale up screening to additional settings (eg, radiation oncology clinic) where patients with HNC may receive care.

In conclusion, routine screening for suicide risk is a public health priority for cancer care delivery, especially among patients with cancer who are at increased risk, such as individuals with HNC.14 Our study outlines key implementation issues that should be considered when integrating suicide risk screening into routine care delivery for patients with cancer. Future studies are needed to develop and test implementation strategies that overcome barriers to suicide screening implementation, such as data display and visualization, patient and provider education, and integration with other PROMs.

Angela M. Stover

Honoraria: Pfizer, Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), Henry Ford Health System, Purchaser Business Group on Health

Consulting or Advisory Role: Navigating Cancer

Research Funding: Urogen pharma (Inst), SIVAN Innovation (Inst)

Carley Geiss

Employment: HCA Healthcare (I)

Sean Powell

Consulting or Advisory Role: Patient Advocacy Startegies, AllStripes, Rigel, Immunovent

Julie Hallanger-Johnson

Consulting or Advisory Role: HRA Pharma

Research Funding: Corcept Therapeutics

Kedar S. Kirtane

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Oncternal Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, Macrogenics, Immunomedics, Myovant Sciences, Veru, Agenus

Consulting or Advisory Role: MyCareGorithm

Neelima Jammigumpula

Employment: Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: United Health Group (I)

Randa Perkins

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Progyny

Other Relationship: Centene (I)

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/263299

Dana E. Rollison

Leadership: NanoString Technologies

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: NanoString Technologies

Research Funding: Flatiron Health

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: I am a coinventor on a provisional patent application filed in July of 2020. The patent pertains to the use of spectrophotometer-measured ultraviolet radiation exposure in combination with regulatory T-cells measured in circulation to predict risk of subsequent skin cancer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Caserta, NanoString Technologies

Heather S.L. Jim

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Medical Affairs, Merck

Research Funding: Kite, a Gilead Company (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Methods of Treating Cognitive Impairment, US Letters Patent No. 10806772, October 20, 2020

Brian D. Gonzalez

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Elly Health

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sure Med Compliance, KemPharm

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: US Trademark Serial Number 88480263 (virtual reality software)

Edmondo Robinson

Leadership: Ardent Health

Amir Alishahi Tabriz

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Surgalign, Cortexyme

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. K.T. attests that the authors had access to all the study data, take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489. Supported by the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurements Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kea Turner, Sean Powell, Kedar S. Kirtane, Neelima Jammigumpula, Colin Moore, Dana E. Rollison, Heather S.L. Jim, Brian D. Gonzalez, Scott M. Gilbert

Administrative support: Kea Turner, Dana E. Rollison, Brian D. Gonzalez, Scott M. Gilbert

Provision of study materials or patients: Kea Turner, Julie Hallanger-Johnson, Scott M. Gilbert

Collection and assembly of data: Kea Turner, Carley Geiss, Sean Powell, Julie Hallanger-Johnson, Kedar S. Kirtane, Neelima Jammigumpula, Randa Perkins, Dana E. Rollison, Brian D. Gonzalez, Scott M. Gilbert

Data analysis and interpretation: Angela M. Stover, Danielle B. Tometich, Carley Geiss, Arianna Mason, Oliver T. Nguyen, Emma Hume, Rachael McCormick, Sean Powell, Krupal B. Patel, Kedar S. Kirtane, Colin Moore, Randa Perkins, Dana E. Rollison, Heather S.L. Jim, Laura B. Oswald, Sylvia Crowder, Brian D. Gonzalez, Edmondo Robinson, Amir Alishahi Tabriz, Jessica Y. Islam

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Oncology Providers' and Professionals' Experiences With Suicide Risk Screening Among Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Angela M. Stover

Honoraria: Pfizer, Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), Henry Ford Health System, Purchaser Business Group on Health

Consulting or Advisory Role: Navigating Cancer

Research Funding: Urogen pharma (Inst), SIVAN Innovation (Inst)

Carley Geiss

Employment: HCA Healthcare (I)

Sean Powell

Consulting or Advisory Role: Patient Advocacy Startegies, AllStripes, Rigel, Immunovent

Julie Hallanger-Johnson

Consulting or Advisory Role: HRA Pharma

Research Funding: Corcept Therapeutics

Kedar S. Kirtane

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Oncternal Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, Macrogenics, Immunomedics, Myovant Sciences, Veru, Agenus

Consulting or Advisory Role: MyCareGorithm

Neelima Jammigumpula

Employment: Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: United Health Group (I)

Randa Perkins

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Progyny

Other Relationship: Centene (I)

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/263299

Dana E. Rollison

Leadership: NanoString Technologies

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: NanoString Technologies

Research Funding: Flatiron Health

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: I am a coinventor on a provisional patent application filed in July of 2020. The patent pertains to the use of spectrophotometer-measured ultraviolet radiation exposure in combination with regulatory T-cells measured in circulation to predict risk of subsequent skin cancer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Caserta, NanoString Technologies

Heather S.L. Jim

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Medical Affairs, Merck

Research Funding: Kite, a Gilead Company (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Methods of Treating Cognitive Impairment, US Letters Patent No. 10806772, October 20, 2020

Brian D. Gonzalez

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Elly Health

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sure Med Compliance, KemPharm

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: US Trademark Serial Number 88480263 (virtual reality software)

Edmondo Robinson

Leadership: Ardent Health

Amir Alishahi Tabriz

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Surgalign, Cortexyme

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, et al. : Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 366:1310-1318, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henson KE, Brock R, Charnock J, et al. : Risk of suicide after cancer diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry 76:51-60, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, et al. : Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:4731-4738, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravaioli A, Crocetti E, Mancini S, et al. : Suicide death among cancer patients: New data from northern Italy, systematic review of the last 22 years and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 125:104-113, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaorsky NG, Zhang Y, Tuanquin L, et al. : Suicide among cancer patients. Nat Commun 10:207, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun LM, Lin CL, Shen WC, et al. : Suicide attempts in patients with head and neck cancer in Taiwan. Psychooncology 29:1026-1035, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahouma M, Kamel M, Abouarab A, et al. : Lung cancer patients have the highest malignancy-associated suicide rate in USA: A population-based analysis. Ecancermedicalscience 12:859, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang SM, Chang JC, Weng SC, et al. : Risk of suicide within 1 year of cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer 142:1986-1993, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schairer C, Brown LM, Chen BE, et al. : Suicide after breast cancer: An international population-based study of 723,810 women. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1416-1419, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn SR, Stoltzfus KC, Mackley HB, et al. : Long-term causes of death among pediatric patients with cancer. Cancer 126:3102-3113, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du L, Shi HY, Yu HR, et al. : Incidence of suicide death in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 276:711-719, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson A, Scrutton F, Wilkinson L, et al. : The risk of suicide in cancer patients: A review of the literature. Psychooncology 19:1250-1258, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang DC, Chen AW, Lo YS, et al. : Factors associated with suicidal ideation risk in head and neck cancer: A longitudinal study. Laryngoscope 129:2491-2495, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osazuwa-Peters N, Simpson MC, Zhao L, et al. : Suicide risk among cancer survivors: Head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer 124:4072-4079, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aboumrad M, Shiner B, Riblet N, et al. : Factors contributing to cancer-related suicide: A study of root-cause analysis reports. Psychooncology 27:2237-2244, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole TB, Bowling JM, Patetta MJ, et al. : Risk factors for suicide among older adults with cancer. Aging Ment Health 18:854-860, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry M, Rosberger Z, Bertrand L, et al. : Prevalence and risk factors of suicidal ideation among patients with head and neck cancer: Longitudinal study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 159:843-852, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osazuwa-Peters N, Barnes JM, Okafor SI, et al. : Incidence and risk of suicide among patients with head and neck cancer in rural, urban, and metropolitan areas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 147:1045-1052, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, Handley R, et al. : Risk of suicidal self-directed violence among US veteran survivors of head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 147:981-989, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kam D, Salib A, Gorgy G, et al. : Incidence of suicide in patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141:1075-1081, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gascon B, Leung Y, Espin-Garcia O, et al. : Suicide risk screening and suicide prevention in patients with cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr 5:pkab057, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolva E, Hoffecker L, Cox-Martin E: Suicidal ideation in patients with cancer: A systematic review of prevalence, risk factors, intervention and assessment. Palliat Support Care 18:206-219, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung YW, Li M, Devins G, et al. : Routine screening for suicidal intention in patients with cancer. Psychooncology 22:2537-2545, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers H, et al. : Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res 30:3015-3033, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stover AM, Tompkins Stricker C, Hammelef K, et al. : Using stakeholder engagement to overcome barriers to implementing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in cancer care delivery: Approaches from 3 prospective studies. Med Care 57:S92-S99, 2019. (suppl 5 suppl 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen H, Butow P, Dhillon H, et al. : A review of the barriers to using Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in routine cancer care. J Med Radiat Sci 68:186-195, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker J, Hansen CH, Butcher I, et al. : Thoughts of death and suicide reported by cancer patients who endorsed the “suicidal thoughts” item of the PHQ-9 during routine screening for depression. Psychosomatics 52:424-427, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graney J, Hunt IM, Quinlivan L, et al. : Suicide risk assessment in UK mental health services: A national mixed-methods study. Lancet Psychiatry 7:1046-1053, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeCloux M, Aguinaldo LD, Lanzillo EC, et al. : PCP opinions of universal suicide risk screening in rural primary care: Current challenges and strategies for successful implementation. J Rural Health 37:554-564, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang M, Uttaro T, Caine E, et al. : Implementing routine suicide risk screening for psychiatric outpatients with serious mental disorders: I. Qualitative results. Arch Suicide Res 13:160-168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roaten K, Johnson C, Genzel R, et al. : Development and implementation of a universal suicide risk screening program in a safety-net hospital System. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 44:4-11, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606-613, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. : Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv 64:1195-1202, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louzon SA, Bossarte R, McCarthy JF, et al. : Does suicidal ideation as measured by the PHQ-9 predict suicide among VA patients? Psychiatr Serv 67:517-522, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossom RC, Coleman KJ, Ahmedani BK, et al. : Suicidal ideation reported on the PHQ9 and risk of suicidal behavior across age groups. J Affect Disord 215:77-84, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarborough BJH, Stumbo SP, Ahmedani B, et al. : Suicide behavior following PHQ-9 screening among individuals with substance use disorders. J Addict Med 15:55-60, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. : The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168:1266-1277, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Halabí S, Sáiz PA, Burón P, et al. : Validation of a Spanish version of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 9:134-142, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matarazzo BB, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. : Predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale among a cohort of at-risk veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav 49:1255-1265, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz I, Barry CN, Cooper SA, et al. : Use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) in a large sample of Veterans receiving mental health services in the Veterans Health Administration. Suicide Life Threat Behav 50:111-121, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman BM, Zevon MA, D'Arrigo MC, et al. : Screening for distress in cancer patients: The NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psychooncology 13:792-799, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui D, Bruera E: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage 53:630-643, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. : Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:50, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton AB, Finley EP: Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res 280:112516, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E: Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5:80-92, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guest G, Namey E, Chen M: A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One 15:e0232076, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349-357, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeHay T, Ross S, McFaul M: Training medical providers in evidence-based approaches to suicide prevention. Int J Psychiatry Med 50:73-80, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sale E, Hendricks M, Weil V, et al. : Counseling on access to lethal means (CALM): An evaluation of a suicide prevention means restriction training program for mental health providers. Community Ment Health J 54:293-301, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobson JM, Osteen P, Jones A, et al. : Evaluation of the recognizing and responding to suicide risk training. Suicide Life Threat Behav 42:471-485, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeCloux M: The development of a brief suicide screening and risk assessment training webinar for rural primary care practices. Rural Ment Health 42:60-66, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gask L, Lever-Green G, Hays R: Dissemination and implementation of suicide prevention training in one Scottish region. BMC Health Serv Res 8:246, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fenwick CD, Vassilas CA, Carter H, et al. : Training health professionals in the recognition, assessement and management of suicide risk. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 8:117-121, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Little V, James MC: Suicide safer care: A public health approach to training primary care providers in addressing suicide. J Health Care Poor Underserved 31:1050-1053, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foster A, Croot L, Brazier J, et al. : The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: A systematic review of reviews. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2:46, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang R, Burgess ER, Reddy MC, et al. : Provider perspectives on the integration of patient-reported outcomes in an electronic health record. JAMIA Open 2:73-80, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. : Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res 21:1305-1314, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santana MJ, Haverman L, Absolom K, et al. : Training clinicians in how to use patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice. Qual Life Res 24:1707-1718, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Edbrooke-Childs J, Wolpert M, Deighton J: Using patient reported outcome measures to improve service effectiveness (UPROMISE): Training clinicians to use outcome measures in child mental health. Adm Policy Ment Health 43:302-308, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harle CA, Listhaus A, Covarrubias CM, et al. : Overcoming barriers to implementing patient-reported outcomes in an electronic health record: A case report. J Am Med Inform Assoc 23:74-79, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sandhu S, King Z, Wong M, et al. : Implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer care at an academic center: Identifying opportunities and challenges. JCO Oncol Pract 16:e1255-e1263, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Absolom K, Holch P, Woroncow B, et al. : Beyond lip service and box ticking: How effective patient engagement is integral to the development and delivery of patient-reported outcomes. Qual Life Res 24:1077-1085, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stonbraker S, Porras T, Schnall R: Patient preferences for visualization of longitudinal patient-reported outcomes data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27:212-224, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snyder CF, Smith KC, Bantug ET, et al. : What do these scores mean? Presenting patient-reported outcomes data to patients and clinicians to improve interpretability. Cancer 123:1848-1859, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McNeill M, Noyek S, Engeda E, et al. : Assessing the engagement of children and families in selecting patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and developing their measures: A systematic review. Qual Life Res 30:983-995, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, et al. : Comparison of the financial burden of survivors of head and neck cancer with other cancer survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145:239-249, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Warinner CB, Bergmark RW, Sethi R, et al. : Cancer-related activity limitations among head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope 132:593-599, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giuliani M, Papadakos J, Broadhurst M, et al. : The prevalence and determinants of return to work in head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 27:539-546, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Broemer L, Friedrich M, Wichmann G, et al. : Exploratory study of functional and psychological factors associated with employment status in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 43:1229-1241, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hempstead KA, Phillips JA: Rising suicide among adults aged 40-64 years: The role of job and financial circumstances. Am J Prev Med 48:491-500, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pool LR, Burgard SA, Needham BL, et al. : Association of a negative wealth shock with all-cause mortality in middle-aged and older adults in the United States. JAMA 319:1341-1350, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chera BS, Eisbruch A, Murphy BA, et al. : Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in head and neck cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju127, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horowitz LM, Snyder D, Ludi E, et al. : Ask suicide-screening questions to everyone in medical settings: The asQ'em Quality Improvement Project. Psychosomatics 54:239-247, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]