Abstract

Background

The lack of overall experience and reporting on angiographic findings in previously published studies of renal arterial embolization (RAE) compelled us to report our overall experience on a series of patients.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study was performed analyzing data of patients enrolled for RAE between 2010 and 2019. History, physical examination, and laboratory data were reviewed for all patients. Abdominal ultrasound was the initial imaging study, and all patients underwent subsequent computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The outcome of RAE was determined based on radiographic and clinical findings.

Results

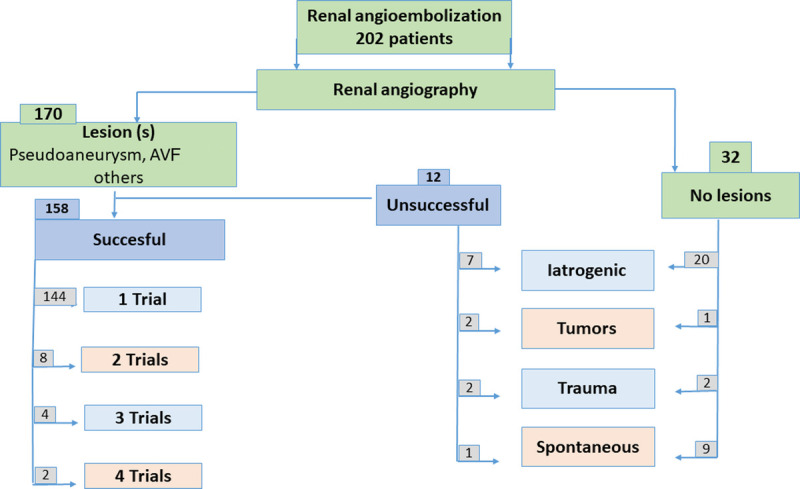

Data from 202 patients were analyzed, with a mean age of 45 ± 15 years, and 71.3% of patients were male. Iatrogenic injury was the most common indication for RAE (54%), followed by renal tumors, trauma, and spontaneous, in 27.7%, 10.4%, and 8.4% of patients, respectively. Renal angiography revealing pseudoaneurysm alone or with other pathology in the lower pole of the kidney was the most common finding (40.6%), whereas no lesions were identified on angiography in 32 patients (15.8%), after which RAE was subsequently aborted. Renal arterial embolization was successful in 158 of 170 patients (92.9%) after 1 or more trials (maximum of 4). Microcoil alone or with other embolic materials was the most commonly used material for embolization (85%).

Conclusions

Iatrogenic injury was the most common indication for RAE. Pseudoaneurysm alone or with other lesions was the most common lesion on renal angiography; however, angiography showed a negative result in 16% of patients, even those with symptoms. When lesions are present on angiography, the overall success of repeated trials of RAE reached 92.9%.

Keywords: Angiographic findings, Embolization, Renal angioembolization, Renal arterial embolization

1. Introduction

Renal arterial embolization (RAE) has been developed as a minimally invasive nonsurgical interventional procedure used to treat acute renal hemorrhage. With growing experience and technical advances in imaging, catheters, and embolic materials, the indications for RAE have been expanded to include a variety of renal pathology and injuries, both in elective and emergent settings.[1–3]

A number of reviews on RAE can be found in the literature; however, previously published series were limited to single indications: renal trauma,[4] post-percutanous nephrolithotomy (PCNL),[5] and renal angiomyolipoma (AML).[6] Moreover, published studies that have integrated different indications for RAE have reported small sample sizes: 15 patients,[7] 26 patients,[8] and 41 patients.[9] To date, no studies have reported details of angiographic findings.

In this study, we aimed to review data from patients who were treated by a highly specialized interventional uroradiology team at a large regional tertiary urology and nephrology institute. We report our overall experience in one comprehensive study, highlighting different indications for RAE, our technique, angiographic findings, overall outcomes, and complications.

2. Materials and methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective analysis of medical record data for all patients scheduled for RAE in the hospital's database between January 2010 and December 2019. Our data included both our own patients and those who were transferred from other hospitals for immediate intervention.

2.1. Laboratory and imaging investigations

A standard medical history was obtained, including details regarding the insult (trauma or surgery), and a routine physical examination was performed. Basic laboratory investigations included serial hemoglobin measurement and coagulation profile. Initial abdominal ultrasound, performed for all patients, reported kidney size and presence or absence of renal masses, renal hematoma, and perinephric collections. Any associated abdominal organ injury, collections, or free fluid was also reported. Doppler renal ultrasound was performed on selected patients. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography was performed using a 64-multidetector CT scanner (Brilliance; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). Noncontrast CT scan was done to measure the size of the intrarenal or perinephric hematoma and detect any other associated abdominal injuries. In those patients with a normal serum creatinine and no contrast allergy, CT angiography was performed after intravenous (IV) administration of 1–2 mL/kg of noniodinated contrast media. Computed tomography angiography reported the renal vascular arterial and venous anatomy, renal vascular variation, and the nature of renal vascular injury, which aided planning for the diagnostic angiography procedure. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography was performed (GE Signa Horizon LX 1.5T magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] system and Philips Ingenia 3T MRI system) after IV administration of 0.2 mmol/kg of DOTAREMR 0.5 mmol/mL in patients with compromised renal function or those with contraindications to CT contrast media.

2.2. Renal arterial embolization technique

Written consent was obtained after explaining the procedure to the patient. Digital subtraction angiography was carried out using the Toshiba Medical Angiography System (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Per protocol, a 1 g prophylactic dose of an IV third-generation cephalosporin was given to all patients.

Under local anesthesia, vascular access was obtained via femoral artery puncture. Using the Seldinger technique, a guide wire was inserted into the renal artery under fluoroscopic guidance. The renal artery was selectively catheterized via 5F cobra head catheter. Nonionic contrast media (Omnipaque 350 mg/mL; Schering, Berlin, Germany) was used for arteriography. Catheter tip position at the very proximal end of the catheterized renal artery was confirmed via fluoroscopy-guided injection of a test dose of contrast (2 mL of contrast diluted with saline in a 1:1 ratio), which enabled clear visualization of the vascular tree, including the capsular artery.

Manual injection was used in selected angiography cases (8–10 mL of contrast media per injection). The runs were finished after the renal vein was clearly visualized followed by saline of the same amount as the contrast media. Diagnostic images were carefully assessed for the presence of vascular pathology, including localizing the lesion and the branch of the renal artery supplying the area of the lesion. The catheter was further advanced subselectively into the segmental branch of the renal artery feeding the lesion (4–5 mL of contrast media per injection). Additional oblique and magnification views were used to help delineate the exact location of the lesion.

Microcoils (pushable platinum coils; Boston Scientific, Boston, MA) sized 3–5 mm in diameter and 4–9 mm in length were the most commonly used embolic material. Other materials, alcohol and gel foam, were used in select cases. After embolization, selective angiography for assessment of arterial occlusion was performed while the catheter was in the main renal artery using manual injection of contrast media (8–10 mL of contrast media per injection).

2.3. Indications for RAE and initial management

We classified indications for RAE into main 3 categories: iatrogenic, posttraumatic, and renal tumor. Iatrogenic referred to cases that developed complications after PCNL under fluoroscopic guidance, percutaneous nephrostomy, ultrasound-guided biopsy, and open renal surgery. Posttraumatic cases included blunt and penetrating renal trauma. Renal tumors included AML and renal cell carcinoma (RCC). When no cause for hematuria was identified, cases were classified as unknown (spontaneous). Conservative treatment, such as bed rest, serial hemoglobin, IV fluids, and blood transfusion if needed, was administered first for emergent cases with stable vital signs. Renal arterial embolization was indicated when conservative management failed and a drop in blood pressure and/or hemoglobin level occurred.

2.4. Postprocedure care

The puncture site was compressed with a tight, sterile bandage, and all patients were put on bed rest for 24 hours. The puncture site was observed hourly and vital signs were monitored closely for the first 4 hours, then every 4 hours thereafter on the first day after the procedure.

2.5. Outcome

The outcome of RAE was judged by radiographic and clinical findings, including immediate disappearance of renal pathology on postprocedure angiography and improvement of hematuria and vital signs. Failure to embolize a lesion or persistence of symptoms with continuous hemoglobin drop warranted repeated RAE trials. Delayed follow-up imaging (either ultrasonography, CT, or both) was conducted based on the initial cause during follow-up visits.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data were organized and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY). For univariate analysis, frequency and percentage were used to describe nominal and ordinal variable data. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe scale variable with normally distributed data. Median and range were used for nonnormally distributed data. For bivariate analysis, χ2 test was used for nominal variable data. Paired-sample t test was used for normally distributed continuous data.

3. Results

Of 213 patients, 202 patients with complete data were eligible for review. The mean age was 45 ± 15 years, and 144 patients (71.3%) were male; other demographic data are shown in Table 1. Three patients (1.5%) who presented with shock underwent urgent RAE. The median time from presentation to intervention was 3 days (range, 0–10 days), and median hospital stay was 4 days (range, 2–21 days). Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance angiography revealed pseudoaneurysm as the most frequent finding, followed by hematoma in nontumor cases. No cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis were recorded post-MRI in patients with impaired renal function.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 202 patients enrolled for renal arterial embolization.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 144 (71) |

| Female | 58 (29) |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Hematuria | 150 (75) |

| Pain | 47 (23) |

| Other | 5 (2) |

| ASA score, n (%) | |

| ASA I | 150 (75) |

| ASA II | 45 (22) |

| ASA III | 7 (3) |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 45 ± 15 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 21 ± 3 |

| Preprocedural Hb, mean ± SD, g/L | 9 ± 2.4 |

| Platelets, mean ± SD, platelets/mcL | 270 ± 80 |

| Prothrombin level, mean ± SD, % | 84 ± 15 |

| Preprocedural Cr, median (range), mg/dL | 1.3 (0.6–8.2) |

| Blood transfusion units, median (range) | 2 (0–10) |

| Total number of RA, median (range) | 1 (0–4) |

Decimals were deleted for simplification.

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; Hb = hemoglobin; Cr = creatinine; RA = renal artery.

Significant bleeding after PCNL was the most common indication (108 cases [53.5%]). During the study period, 5150 PCNL cases were performed in our institution; of these, 70 (1.3%) were enrolled for RAE. An additional 6 patients were referred for RAE because of renal hemorrhage after PCNL performed outside our institution. Embolization was accomplished in 65 cases (1.2%), with lesions identified on angiography (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Left renal arterial embolization in a 46-year-old male patient with recurrent attacks of hematuria after PCNL. (A) Selective left renal artery angiography by Cobra head catheter showing a large contrast-filled cavity representing pseudoaneurysm supplied by a middle segmental interlobar artery. (B) Postembolization angiography revealed complete occlusion of the feeding artery by metallic pushable coil. PCNL = percutanous nephrolithotomy.

Renal tumors, either RCC or AML, were the second most common indication for RAE (56 cases [27.7%]). Six AML patients were treated urgently for large retroperitoneal hematoma with AML; RAE was successful in 5. An additional 17 patients were treated electively; 2 had negative angiography results, whereas RAE was successful in the remaining 15 patients, 2 of whom required 3 repeated RAE procedures.

Renal penetrating or blunt trauma was the third most common indication. Of blunt renal trauma cases, 7 were classified as grade III, 5 as grade IV, and 2 as grade V. The remaining 17 patients (8.4%) were scheduled for RAE with no identifiable cause of bleeding and were categorized as spontaneous causes. Details of indications are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indications of renal arterial embolization in 202 patients.

| Indication | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Iatrogenic | 108 | 53 |

| PCNL | 76 | |

| Open surgery | 24 | |

| PCN | 7 | |

| Biopsy | 1 | |

| Renal tumors | 56 | 28 |

| AML/elective | 17 | |

| AML/emergency | 6 | |

| RCC/prenephrectomy | 22 | |

| RCC/palliative | 9 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Post-RF ablation | 1 | |

| ADPKD | 1 | |

| Trauma | 21 | 10 |

| Blunt | 15 | |

| Penetrating | 6 | |

| Others | 17 | 9 |

| Spontaneous (unknown) | 14 | |

| Bilateral subcapsular hematoma | 1 | |

| Hemangioma on the upper calyx | 1 | |

| Arteriovenous malformation | 1 |

Decimals were deleted for simplification.

ADPKD = autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; AML = angiomyolipoma; PCN = percutaneous nephrostomy; PCNL = percutaneous nephrolithotomy; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; RF = radiofrequency.

Diagnostic angiography was performed for all patients. The left side was affected more often (55.9%), and pseudoaneurysm alone or with other pathology was the most common finding (40.6%). Other diagnostic angiography findings are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diagnostic renal angiography findings.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Side, n (%) | |

| Left | 113 (56) |

| Right | 87 (43) |

| Bilateral | 2 (1) |

| Type of lesion, n (%) | |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 82 (41) |

| AVF | 24 (12) |

| Both pseudoaeurysm and AVF | 18 (9) |

| Tumor + pseudoaneurysm | 46 (23) |

| No lesion identified | 32 (15) |

| Renal artery anatomy, n (%) | |

| Normal | 180 (89) |

| Accessory | 22 (11) |

| Site of vascular lesion, n (%) | |

| Upper zone | 24 (12) |

| Mid zone | 57 (28) |

| Lower zone | 89 (44) |

| No lesion identified | 32 (16) |

| Size of lesion, median (range), cm | |

| Width | 2.5 (2–12) |

| Length | 2.7 (2–18) |

| Tumors | |

| Width | 10 (6–14) |

| Length | 7.5 (5–18) |

Decimals were deleted for simplification.

AVF = arteriovenous fistula.

Of 202 patients, 32 patients with negative angiography results did not undergo RAE, resulting in a total of 170 patients who underwent RAE. In 158 of 170 patients, the procedure was successful after 1 or more trials; 1 trial was successful in 144 patients (84.7%), whereas repeated trials were required for complete embolization in 14 patients (8.2%), with an overall success rate of 92.9%. Renal arterial embolization was unsuccessful in 12 patients after 1 or more trials (Fig. 2). Renal arterial embolization resulted in improvement of hematuria in 134 of 150 patients (89.3%), and short-term changes in renal function were observed in 8 patients (5.3%; p = 0.01), with 4 patients requiring hemodialysis. Bivariate analysis revealed that the presence of an accessory artery was the only predictor of a failed RAE trial; 4 of 16 patients (25%) in the failed group had accessory renal artery, as compared with only 8 of 134 (6.0%) in the successful group (p = 0.001).

Figure 2.

Renal angiographic findings and outcomes in 202 patients scheduled for renal angioembolization. AVF = arteriovenous fistula.

Microcoil alone or with other embolic materials was the most commonly used material for embolization (85% of cases). Other materials, such as alcohol and gel foam, were used in the remaining patients.

Minor complications were recorded in 13 patients; 4 cases had a puncture site hematoma that resolved, and 9 cases had postembolization syndrome. All were managed conservatively. The procedure affected short-term renal function in 8 patients (p = 0.01). In addition, nephrectomy was carried out for 17 patients because of failed RAE or persistent/recurrent symptoms. Three mortality cases (1.4%) were reported with RAE; 1 after blunt trauma and 2 after PCNL. The main renal arteries were not affected in those 3 patients; however, those patients had severe bleeding with chronic medical conditions.

4. Discussion

Renal arterial embolization aims to embolize bleeding vessels and stop bleeding while sparing the rest of the kidney.[9] Recently, with the modern shift to minimally invasive surgery and endourology, more patients are being enrolled for RAE, especially after PCNL. In our series, iatrogenic renal injuries contributed to 53% of all cases, and PCNL contributed to 70% of iatrogenic cases. These findings agree with data from most published series.[7,9,10]

Hematuria after PCNL is common, and a few cases may require blood transfusion; however, transcatheter RAE is rarely indicated. Among 1520 PCNL procedures, Xiong et al. reported 15 cases (0.09%) that were scheduled for RAE, of which 13 (0.08%) had embolization done.[5] In another study that included 1854 PCNL procedures, 27 cases (1.4%) were scheduled for RAE, of which 24 (1.2%) had embolization done.[11] As concluded by the authors, RAE controlled bleeding and saved the kidneys with marked declines in renal exploration and nephrectomy. In our series, 1.3% of cases were enrolled for RAE, and 1.2% ultimately underwent embolization. This finding could be explained by subjective criteria for enrolling patients to RAE that may include cases with mild renal injuries that cannot be treated by RAE. Cases found to have negative angiography results with no lesions supports this hypothesis.

Renal arterial embolization has been used also in treating renal tumors in a variety of clinical settings, in particular AML and RCC. In our study population, RAE was successful in 5 of 6 patients who were treated urgently for huge retroperitoneal hematoma with AML; 17 patients were treated electively, 2 were found to have negative angiography results, and the remaining cases were successful. Repeated procedures are commonly required for AML cases, repeated procedures were performed in 2 of 15 cases (13%) in this study. Even higher proportions requiring repeated procedures were reported by Chick et al. (5 of 17 cases)[1] and Bishay et al. (6 of 16 cases).[6]

Among patients with RCC tumors in our series, most of the cases that were scheduled for RAE were those who had large renal tumors. Renal arterial embolization was done before surgery with the aim of easy dissection and to minimize blood loss. We did not measure blood loss accurately in our cohort to judge the success of RAE, but Bakal et al.[12] reported that preoperative arterial embolization using ethanol significantly minimized the volume of blood transfusion in comparison to the control group (250 vs. 800 mL, p = 0.01). The trend in our institution was to perform total renal embolization on the morning of surgery, and it seems that there is no consensus in the literature regarding optimum timing. Schwartz et al.,[3] in a series of 121 patients, included 55% as prenephrectomy cases with median tumor size of 11 cm (in comparison to 10 cm in our series) and reported a wide range of time with a median of 2 days (range, 1–70 days). One day before nephrectomy could be the optimum time for embolization as reported by Eom et al.[13]

With increased understanding of the pathophysiology of blunt renal trauma, conservative management has become successful for the vast majority of blunt renal trauma cases. However, renal exploration may be required for unstable patients with grade IV to V trauma. In stable patients, RAE is a viable option as a minimally invasive modality.[8] We do not have a national trauma registry; however, Hotaling et al.,[4] in a large series of 9000 cases from a renal trauma national data set, reported that only 165 patients (0.01%) were scheduled for RAE and 77 (47%) were found to have lesions. As reported, there was an overuse of RAE that included many minor renal traumas (grades I–III). Vozianov et al.,[14] in another series that included 20 patients with blunt renal trauma, reported a 90% success rate with RAE on the first attempt and 10% after repeated procedures.

The cause of renal injuries is not always identifiable, and 17 patients (8.4%) in our series had no cause by history (no trauma or recent intervention). In addition, there were no tumors diagnosed on imaging; nevertheless, vascular lesions with arteriovenous malformation were detected in only 2 patients. Moreover, this group included the highest percentage of cases with negative angiography findings resulting in aborted procedures. Our data are limited for this subgroup of patients, and a paucity of literature is available, including a small case series with a lower success rate[13] and case reports.[15]

Ultrasonography and Doppler can be used as initial imaging studies in the evaluation of cases scheduled for RAE. They can detect renal masses, hematomas, and perinephric hematoma well but have low sensitivity for detecting vascular lesions. Therefore, CT or MRI is the criterion standard for diagnosis of such cases before RAE.

Our angiographic findings revealed that the most often affected areas were the left side (55.9%) and the lower zone of the kidney (87 of 165 cases [52.7%]). Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is more common on the left side, and the lower calyceal puncture is the most frequent puncture site in PCNL, which could explain these findings. More than half of our patients had pseudoaneurysm alone or with other lesions, in agreement with other published series,[7,14,16] where pseudoaneurysm was the most common lesion. A pseudoaneurysm occurs when a blood vessel wall is injured, and extravasating blood collects in the surrounding tissue. A vascular lesion may induce a perivascular hematoma, which dissolves, later leaving a pseudoaneurysm with no vascular wall except a wall of connective tissue. If this pseudoaneurysm connects to a part of the collecting system, hematuria occurs. Arteriovenous fistula was the second most common lesion identified during angiography.

Thirty-two patients in our cohort were found to have negative catheter angiography results “although symptomatic,” whose scheduled angioembolization was aborted. Patients with an unknown cause of hematuria had the highest percentage of negative catheter angiography (9 of 17 [53%]). Similar findings (although with smaller proportions) have been reported in the literature by Jain et al.[9] (6 of 41 [14%]) and Huber et al.[10] (2 of 21 [10%]). These findings could be explained by mild vascular lesions, such as a small aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula. Renal arteriovenous malformations, or arteriovenous fistulas, are abnormal communications between the intrarenal arterial and venous systems. Renal arteriovenous malformations can be idiopathic, congenital, or acquired. They are sometimes associated with genetic disorders, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[17]

There are many embolic materials available, including polyvinyl alcohol, gel foam, and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate[7]; however, microcoils were the most common embolic material used in our series, either alone or with other embolic materials (85%). Most published series[3,7] also used microcoils.

Radiologic and clinical success (in some cases after repeated trials) was recorded in 158 patients with an overall success rate of 92.9%, similar to results found in other published series.[4,10] Given that 14 cases (8.2%) required more than 1 trial for complete embolization, we recommend RAE to be repeated in cases with lesions present on angiography, similar to the recommendation by Huber et al.[10] that a second trial is worthwhile.

Despite being a minimally invasive procedure, RAE is not without a risk of complications. A transient elevation of serum creatinine was observed in our patients; however, many series have reported that such short-term renal function change does not affect glomerular filtration rate in the long term.[18] Postembolization syndrome is common and has been reported in many series, with most cases being self-limited.[2] We recorded only 9 patients (4.5%) in our series, who developed mild fever, flank pain, and leukocytosis; all improved with conservative management.

One of the limitations of our study was its retrospective design; however, it is difficult to conduct a prospective study of an infrequent procedure. In addition, the long-term effects of RAE have not been fully covered in this study. Despite these limitations, a strength of our study was that it included a large cohort treated at a single interventional radiology unit at a tertiary urology institute.

5. Conclusions

Significant bleeding after iatrogenic renal injury, especially after PCNL, is the most frequent indication for RAE. Pseudoaneurysm alone, or with other lesions, is the most common lesion identified on renal angiography. However, no lesion could be identified in 16% of cases, even in symptomatic patients.

Clinical and radiologic success can be achieved with microcoils embolization after 1 trial in the majority (90%) of cases. However, in the presence of lesions on angiography, repeated RAE is worthwhile, with an overall success rate reaching 92.9%.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge members of radiology department and Urology department members of Urology and Nephrology Center, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Mansoura University in Egypt. Written consent was obtained after explaining the procedure to the patient. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were done so in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Funding source

None.

Author contributions

ME: Intellectual idea, data analysis, and writing; HF, KAS, MAB, AE: Data collection; TM, TE-D, AA: Writing and reviewing.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Farg HM, Elawdy M, Soliman KA, Badawy MA, Elsorougy A, Mohsen T, El-Diasty T, Abdelhamid A. Renal arterial embolization: indications, angiographic findings, and outcomes in a series of 170 patients. Curr Urol 2023;17(3):213–218. doi: 10.1097/CU9.0000000000000161

Contributor Information

Hashim Mohamed Farg, Email: hashim2008_mf@yahoo.com.

Karim Ali Soliman, Email: Karimali2005@yahoo.com.

Mohamed Ali Badawy, Email: m7mdbdwy@gmail.com.

Ali Elsorougy, Email: alimm@yahoo.com.

Tarek Mohsen, Email: tarek.mohsen@yahoo.com.

Tarek El-Diasty, Email: teldiasty@hotmail.com.

Abdalla Abdelhamid, Email: Abdallahshady333@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Chick CM Tan BS Cheng C, et al. Long-term follow-up of the treatment of renal angiomyolipomas after selective arterial embolization with alcohol. BJU Int 2010;105(3):390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson AI Amukele SA Marcovich R, et al. Efficacy and morbidity of therapeutic renal embolization in the spectrum of urologic disease. J Endourol 2003;17(6):385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MJ, Smith EB, Trost DW, Vaughan ED, Jr. Renal artery embolization: Clinical indications and experience from over 100 cases. BJU Int 2007;99(4):881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotaling JM, Sorensen MD, Smith TG, 3rd, Rivara FP, Wessells H, Voelzke BB. Analysis of diagnostic angiography and angioembolization in the acute management of renal trauma using a national data set. J Urol 2011;185(4):1316–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong LL Huang XB Ye XJ, et al. Characteristics of renal hemorrhage after percutaneous nephrolithotomy and the timing of selective embolization: A report of 13 cases [in Chinese]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2010;42(4):465–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishay VL Crino PB Wein AJ, et al. Embolization of giant renal angiomyolipomas: Technique and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavili E, Dönmez H, Ozcan N, Sipahioğlu M, Demirtaş A. Transarterial embolization for renal arterial bleeding. Diagn Interv Radiol 2009;15(2):143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breyer BN, McAninch JW, Elliott SP, Master VA. Minimally invasive endovascular techniques to treat acute renal hemorrhage. J Urol 2008;179(6):2248–2252; discussion 2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain V Ganpule A Vyas J, et al. Management of non-neoplastic renal hemorrhage by transarterial embolization. Urology 2009;74(3):522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber J Pahernik S Hallscheidt P, et al. Selective transarterial embolization for posttraumatic renal hemorrhage: A second try is worthwhile. J Urol 2011;185(5):1751–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava A Singh KJ Suri A, et al. Vascular complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: Are there any predictive factors? Urology 2005;66(1):38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakal CW, Cynamon J, Lakritz PS, Sprayregen S. Value of preoperative renal artery embolization in reducing blood transfusion requirements during nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1993;4(6):727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eom HJ, Shin JH, Cho YJ, Nam DH, Ko GY, Yoon HK. Transarterial embolisation of renal arteriovenous malformation: Safety and efficacy in 24 patients with follow-up. Clin Radiol 2015;70(11):1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vozianov S, Sabadash M, Shulyak A. Experience of renal artery embolization in patients with blunt kidney trauma. Cent European J Urol 2015;68(4):471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitsogiannis IC, Chatzidarellis E, Skolarikos A, Papatsoris A, Anagnostopoulou G, Karagiotis E. Bilateral spontaneous retroperitoneal bleeding in a patient on nimesulide: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao D, Yu H, Zhu H, Yu K, Hu X, Xie L. Superselective transcatheter renal artery embolization for the treatment of hemorrhage from non-iatrogenic blunt renal trauma: Report of 16 clinical cases. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:455–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi SP, Patel K, Pandya V, Raval M. Renal arteriovenous malformation presenting with massive hematuria. Radiol Case Rep 2015;10(1):1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmerola R Patel V Hartman C, et al. Renal functional outcomes are not adversely 'affected by selective angioembolization following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Asian J Urol 2017;4(1):27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]