Abstract

Background

To date, single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has proven to be ineffective against biomarker-unselected extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (EP-PDNECs). The efficacy of CPI in combination with chemotherapy remains under investigation.

Methods

Patients with advanced, progressive EP-PDNECs were enrolled in a two-part study of pembrolizumab-based therapy. In Part A, patients received pembrolizumab alone. In Part B, patients received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. Primary endpoint: objective response rate (ORR). Secondary endpoints: safety, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Tumours were profiled for programmed death-ligand 1 expression, microsatellite-high/mismatch repair deficient status, mutational burden (TMB), genomic correlates. Tumour growth rate was evaluated.

Results

Part A (N = 14): ORR (pembrolizumab alone) 7% (95% CI, 0.2–33.9%), median PFS 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.7–21.4), median OS 7.8 months (95% CI, 3.1–not reached); 14% of patients (N = 2) had grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). Part B (N = 22): ORR (pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy) 5% (95% CI, 0–22.8%), median PFS 2.0 months (95% CI, 1.9–3.4), median OS 4.8 months (95% CI, 4.1–8.2); 45% of patients (N = 10) had grade 3/4 TRAEs. The two patients with objective response had high-TMB tumours.

Discussion

Treatment with pembrolizumab alone and pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was ineffective in advanced, progressive EP-PDNECs.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03136055.

Subject terms: Neuroendocrine cancer, Cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

Extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (EP-PDNECs) represent a subset of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) characterised by aggressive features and a uniformly poor prognosis. Most patients diagnosed with EP-PDNECs present with metastases, with a median survival of less than 1 year [1]. Histologic subtypes include small-cell and large-cell variants, although the clinical ramifications of these subtypes remain controversial [2, 3]. A non-neuroendocrine component is present in ~40% of cases, a finding of uncertain therapeutic significance, but potentially indicative of an underlying common cancer cell progenitor [4].

EP-PDNECs most commonly arise in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas; other primary sites include genitourinary and gynaecologic organs, and approximately one-third arise in an unknown site [1]. There is no standard therapy for advanced EP-PDNECs, with management generally based on expert opinion given a paucity of data and heterogeneity of the disease. In the first-line, EP-PDNECs are usually treated extrapolating from small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) guidelines with platinum (cisplatin/carboplatin) and etoposide chemotherapy, which can offer a marked, but transient response [3, 5–7]. After first-line therapy, there is no standard second-line option. SCLC salvage regimens or organ-specific chemotherapy regimens for non-NENs of the same site are considered (e.g., topoisomerase 1 inhibitor-, taxane- or other platinum-based therapy), recognising limited activity has been demonstrated regardless of the regimen [8].

Recent therapy advances for SCLC include the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) in the first-line setting with platinum and etoposide chemotherapy, as well as the demonstrated activity of CPIs alone in the salvage setting [9–15]. Given these results with use of CPIs in SCLC and the overlapping histopathological and molecular features between SCLC and EP-PDNECs, there has been great interest in assessing if CPIs have activity in EP-PDNECs.

To date, single-agent CPI therapy has proven ineffective in biomarker-unselected EP-PDNECs [16, 17]. Prior investigations across the spectrum of NENs suggest that dual CPI therapy may be more efficacious, but responses have been limited to a subset of patients [18–22]. A more recent single institution study in NENs of any grade or primary site treated with nivolumab plus temozolomide demonstrated promising efficacy data (ORR 36%), as did a study in high-grade NENs of nivolumab plus platinum-doublet chemotherapy (ORR 50%), suggesting a potential benefit for CPI plus chemotherapy in NENs [23, 24]. However, all of these prior prospective efforts have included a broad spectrum of pulmonary and EP well- and poorly differentiated NENs (many with a mixed high-grade cohort comprised of well-differentiated high-grade NETs and PDNECs), in varying treatment lines, and no studies have evaluated CPIs in combination with chemotherapy with an exclusive focus on EP-PDNECs [16–18, 20, 25–28]. In this open-label, multicenter, adaptive two-stage Phase II study, we investigated the efficacy and safety of (1) pembrolizumab alone and (2) pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (physician’s choice of weekly irinotecan or paclitaxel) in patients with biomarker-unselected, previously treated and progressive, advanced EP-PDNECs.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in patients with EP-PDNECs (ClinicalTrials.gov study NCT03136055). The study was reviewed by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) Institutional Review Boards and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent before study enrolment. Pembrolizumab was provided by Merck & Co.

Patients

The trial enrolled adult male and female patients (age ≥18 years) with histologically confirmed locally advanced or metastatic EP-PDNECs, including cases of unknown primary site. Patients with SCLC, pulmonary large-cell NEC, Merkel cell carcinoma, and well-differentiated high-grade neuroendocrine tumours were excluded. Mixed NENs were allowed if the high-grade NEC component was more than 50% of the biopsy specimen. In this multicenter study, histopathologic assessment was performed by dedicated pathologists at each subsite (UCSF, MSK and DFCI) experienced in the diagnosis and classification of NENs. All patients were required to have disease progression during or after completion of at least one line of any systemic chemotherapy. There was no limit to the number of prior systemic regimens. Patients were further required to have measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, adequate hepatic function (serum bilirubin ≤1.5 times upper limit of normal (ULN) and AST ≤2.5 times ULN (≤5 times if liver metastases were present), and adequate bone marrow function (absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/mm3; platelets ≥100,000/mm3). Patients were not eligible if they had a history of immunodeficiency or autoimmune disease requiring systemic treatment in the two years prior to enrolment, or were receiving systemic steroid therapy (≥10 mg prednisone/day or equivalent) or other immunosuppressive therapy. Patients who received prior therapy with an anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-L2 agent were excluded. Complete eligibility criteria are in the supplemental materials.

Study design

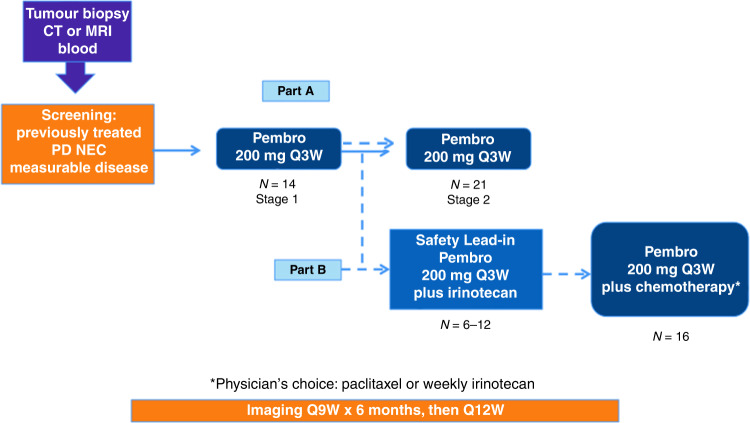

This was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, single arm, open-label, adaptive two-stage study (Fig. 1). There was no randomisation or blinding of patients enrolled in this study. In Part A, enrolled patients were to be treated with single-agent pembrolizumab (200 mg intravenously (IV) every 21 days for up to 35 treatments). If insufficient activity was observed in Part A according to the pre-determined statistical plan, the trial was to proceed to Part B with pembrolizumab (200 mg IV every 21 days for up to 35 treatments) plus chemotherapy (physician’s choice of weekly irinotecan or paclitaxel). Part B included a safety lead-in of 6–12 patients treated with irinotecan (125 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycle) plus pembrolizumab. Subsequent patients in Part B were treated with physician’s choice of either irinotecan or paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15 of 21-day cycle) plus pembrolizumab. Participants continued treatment until progressive disease, unacceptable adverse events (AEs), intercurrent illness preventing treatment administration, or consent withdrawal. Additional guidelines for treatment discontinuation and AE management are in the supplemental materials.

Fig. 1. Study schema.

Patients were enrolled to an open-label, adaptive, two-stage study (which included a safety lead-in for Part B). Pembro pembrolizumab, CT computed tomography scan, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PD NEC poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, Q every, W weeks, mg milligram, N number of patients.

Study assessments

The study primary endpoint was the objective response rate (ORR) according to RECIST v1.1 (investigator-assessed) [29]. The response was assessed by computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and every 9 weeks thereafter. Secondary endpoints were safety, duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). AEs were monitored throughout treatment and for 30 days after treatment ended and were graded in severity according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0.

Correlative sciences

Enrolled subjects underwent a pre-treatment tumour biopsy of the primary site or a metastatic lesion, unless the tumour was inaccessible and/or a biopsy was not felt to be in the patient’s best interest (determined by the treating physician). Tumour programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC; QualTek Molecular Laboratories, Newton, PA). Positive PD-L1 status was defined as a modified proportion score (MPS) of 1% or more in the tumour or at tumour stromal interface.

Results from next-generation sequencing (NGS), microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumour mutational burden (TMB) analyses (previously performed in the context of routine clinical care on archival tumour tissue samples) were compiled from the electronic medical record of enrolled patients. NGS, MSI, and TMB analyses were performed through Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified institutional platforms at UCSF (UCSF 500 Cancer Gene Panel), MSK (Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actional Cancer Targets; MSK-IMPACT), DFCI (OncoPanel), or other commercial platforms (detailed in Supplementary Table 1) [30–38]. For tumours without MSI testing, the tumour mismatch repair (MMR) status determined by IHC was reported if available; MMR-deficiency (dMMR) was defined as any loss of DNA MMR protein expression. High-TMB was defined as a TMB greater than or equal to 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb).

Tumour growth rate

Pre- and on-treatment tumour growth rates (TGRs) were determined in the enrolled patients [39–43]. TGRs before and after starting protocol therapy were determined to explore whether there was any slowing or acceleration of tumour growth related to treatment. The TGR was defined as the percent change per month in RECIST-measurable target lesion size on two contrast-enhanced scans acquired at least 2 weeks apart. TGR = 100*(eTG-1) where TG = 3*log(D2/D1)/t [39]. D1 and D2 represented the sums of longest diameters of target lesions on 1st and 2nd scan, respectively, and t represented the time in months between scans. The pre-treatment TGR (TGRpre) was calculated using the two most recent scans prior to therapy initiation. The on-treatment TGR (TGRon) was calculated using the scan immediately prior to therapy initiation, along with the first on-treatment scan at least 5 weeks later.

Statistical analysis

The Simon two-stage design for Part A pre-specified an enrolment of up to 14 patients in the first stage. If two or more patients responded by week 18, then 21 additional patients would enrol. This design tested a null hypothesis (H0) ORR of 10% versus an alternative hypothesis (H1) ORR of 26% with 80% power and type I error 5%. If there was insufficient activity in Part A, the study would proceed to Part B and enrol 22 to 28 patients, starting with a safety lead-in of 6–12 patients treated with irinotecan plus pembrolizumab to assess the safety of this combination. This design tested H0 ORR of 10% versus H1 ORR 31% with 80% power and type I error 5%. PFS and OS were measured from the date of treatment initiation until date of first progression or death, whichever occurred first (for PFS), or date of death (for OS). Patients who came off-study for reasons other than disease progression were censored at the date of off-study or the date of last imaging before switching therapy. PFS and OS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods. All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5. The data-lock date was September 15, 2021.

Results

Patients

Thirty-six patients were enrolled between July 24, 2017, and August 27, 2020, and received at least one dose of pembrolizumab (Part A) or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B). Sixty-six patients underwent eligibility assessment; 30 patients (45%) were deemed ineligible due to declining performance status (6/30, 20%) during the screening process, not meeting histopathologic criteria (6/30, 20%), laboratory abnormalities (5/30, 17%), presence of central nervous system metastases (3/30, 10%), lack of progressive disease (3/30, 10%), the patient decision to not enrol (3/30, 10%), other condition precluding enrolment (2/30, 7%), active pneumonitis (1/30, 3%) and no measurable disease (1/30, 3%).

All enrolled patients were previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range 1–8) in Part A, and 1 (range 1–4) in Part B. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Number of patients | Part A (N = 14) | Part B (N = 22) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 62 (44-79) | 56 (32-74) |

| Sex, male | 9 (64%) | 15 (68%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 9 (64%) | 19 (86%) |

| Black/Asian/other | 5 (36%) | 3 (14%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 4 (29%) | 10 (45%) |

| 1 | 10 (71%) | 12 (55%) |

| Current or former smoker | 3 (21%) | 11 (50%) |

| Locally advanced disease at initial presentation | 6 (43%) | 2 (9%) |

| Site of origin | ||

| Pancreas/Biliary | 2 (14%) | 5 (23%) |

| Other gastrointestinal | 2 (14%) | 11 (50%) |

| Genitourinary | 4 (29%) | 1 (5%) |

| Gynaecologic | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) |

| Head/neck | 3 (21%) | 0 |

| Unknown | 2 (14%) | 4 (18%) |

| Histology | ||

| Large cell | 2 (14%) | 6 (27%) |

| Small cell | 10 (71%) | 8 (36%) |

| Mixed tumours | 1 (7%) | 3 (14%) |

| Not otherwise specified | 1 (7%) | 5 (23%) |

| Median Ki-67 | 75%* (range 31–91%) | 75% (range 30–95%)** |

| Number of prior lines of systemic therapy, median (range) | 2 (1–8) | 1 (1–4) |

| Prior platinum-based therapy (%) | 14 (100%) | 22 (100%) |

*Available from the tumours of N = 10 patients (71%).

**Available from the tumours of N = 18 patients (82%).

Please refer to Fig. 1 for the study schema. In total, 14 patients were enrolled in Part A, 6 patients were enrolled in the Part B safety lead-in, and an additional 16 patients were enrolled in Part B (pembrolizumab plus physician’s choice of irinotecan or paclitaxel, with 11 patients receiving pembrolizumab plus irinotecan and 5 patients receiving pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel after the Part B safety lead-in); due to not meeting response criteria, we did not move forward with the second stage of part A. One patient remained on protocol-based therapy at the data-lock date.

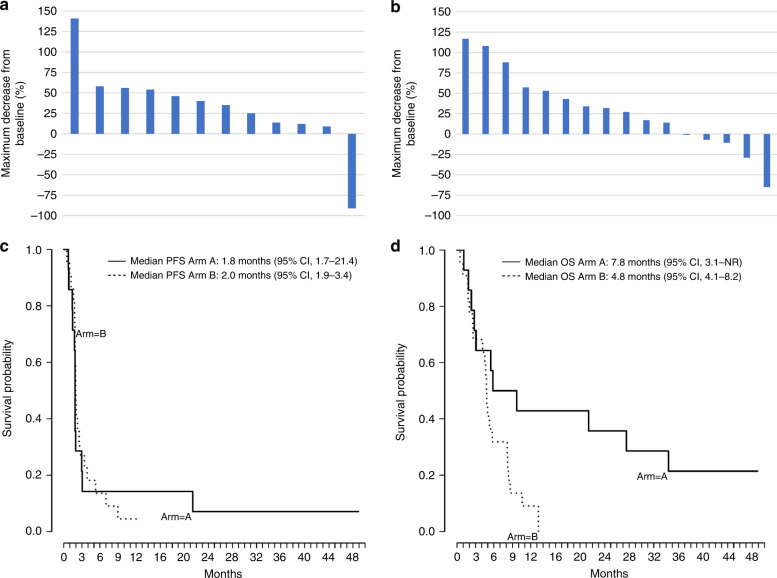

Response evaluation

In Part A (pembrolizumab alone), median treatment duration (interval from treatment start to end-of-study) was 1.9 months (range, 0.8–23 months). One of 14 treated patients demonstrated a complete response (CR), ORR 7% (95% CI, 0.2–33.9). One additional patient (7%) demonstrated SD. In Part B (pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy), median treatment duration (interval from treatment start to end-of-study) was 2.1 months (range, 0.5–9.3 months). One of 22 treated patients demonstrated a PR, ORR 5% (95% CI, 0– 22.8). Four additional patients (18%) demonstrated SD, with 1 of these four patients achieving a near-PR (−29% by RECIST). Please refer to Table 2 and Fig. 2 which detail the response characteristics to pembrolizumab alone and pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Objective response according to RECIST v1.1 criteria.

| Type of response | Part A, N = 14 | Part B, N = 22 |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response—no. (%)* | 1 (7%) | 0 |

| Partial response—no. (%)* | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Stable disease—no. (%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (18%) |

| Progressive disease—no. (%) | 10 (71%) | 11 (50%) |

| Could not be evaluated—no. (%)** | 2 (14%) | 6 (27%) |

| Objective response rate (95% CI)—% | 7% (0.2–33.9) | 5% (0–22.8) |

CI confidence interval.

*Objective responses in this study were classified as either complete responses or partial responses by RECIST v1.1

**Patients could not be evaluated if they experienced clinical progression before the first imaging timepoint and did not undergo blinded radiologic evaluation.

Fig. 2. Tumour responses and clinical outcomes.

a Maximum decrease from baseline in the size of tumours in patients treated with pembrolizumab alone (Part A, N = 12) who underwent blinded radiologic evaluation after initiation of treatment. b Maximum decrease from baseline in the size of tumours in patients treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B, N = 16) who underwent blinded radiologic evaluation after initiation of treatment. c Kaplan–Meier curve showing progression-free survival among the 36 patients with EP-PDNECs who received pembrolizumab alone (Part A, N = 14) or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B, N = 22). Progression-free survival was measured from the start of treatment with alone (Part A) or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B) until the progression of disease or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first. Median progression-free survival in Part A was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.7–21.4) and in Part B was 2 months (95% CI, 1.9–3.4). d Kaplan–Meier curve showing overall survival among the 36 patients with EP-PDNECs who received pembrolizumab alone (Part A, N = 14) or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B, N = 22). Overall survival was measured as the time from the start of treatment with pembrolizumab until death. Median overall survival in Part A was 7.8 months (95% CI, 3.1 to not reached) and in Part B was 4.8 months (95% CI, 4.1–8.2).

Survival analyses

The median follow-up at the time of the data lock was 7.8 months (range, 1.1–48.9) for patients enrolled in Part A and 4.8 months (range, 0.5–13.2) for patients enrolled in Part B. At the time of the data lock, 11 deaths (79%) were observed in Part A (with 2 patients lost to follow-up and 1 alive) and 21 deaths (95%) were observed in Part B (with 1 patient alive). Two patients remain in follow-up.

In Part A, median PFS was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.7–21.4; Fig. 2c). Median OS was 7.8 months (95% CI, 3.1 to not reached; Fig. 2d). In Part B, median PFS was 2 months (95% CI, 1.9–3.4; Fig. 2c). Median OS was 4.8 months (95% CI, 4.1–8.2; Fig. 2d).

Safety

No grade 5 treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were observed in this study. TRAEs of any grade occurred in ten patients (71%) in Part A and 19 patients (86%) in Part B (see Table 3). Grade 3/4 TRAEs occurred in two patients (14%) in Part A and 10 patients (45%) in Part B. In Part A, the most common TRAEs due to pembrolizumab were elevation of the liver function tests (AST/ALT), increase in the creatinine, fatigue, and rash (with each of these TRAEs noted in two patients, 14%). In Part B, the most common TRAEs were all chemotherapy-related. Chemotherapy-related diarrhoea of any grade was observed in 12 (55%) patients (grade 3/4 in 1 patient, 5%), and all patients experiencing chemotherapy-related diarrhoea received irinotecan. Other notable chemotherapy-related TRAEs included fatigue in 9 (41%) patients (grade 3/4 in 2 patients, 9%), and neutropenia in 9 (41%) patients (grade 3/4 in 4 patients, 18%). Please refer to Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events.

| Part A (N = 14) | Part B (N = 22) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades 1–4** (no. patients, %) | Grades 3–4** (no. patients, %) | All grades 1–4** (PEM-related; no. patients, %) | Grades 3–4** (PEM-related; no. patients, %) | All grades 1–4** (chemotherapy-related; no. patients, %) | Grades 3–4** (chemotherapy-related; no. patients, %) | |

| Total subjects with treatment-related adverse events* | ||||||

| Laboratory investigations | ||||||

| Increased AST/ALT | 2 (14%) | 4 (18%) | 1 (5%) | 5 (23%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Increased alkaline phosphatase | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| Hyponatremia | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Increased creatinine | 2 (14%) | |||||

| Decreased white blood cell count | 1 (5%) | 3 (14%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| Lymphopenia | 1 (7%) | 1 (7%) | ||||

| Neutropenia | 3 (14%) | 1 (5%) | 9 (41%) | 4 (18%) | ||

| Anaemia | 2 (9%) | 4 (18%) | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (9%) | |||||

| General disorders | ||||||

| Fatigue | 2 (14%) | 9 (41%) | 3 (14%) | 9 (41%) | 2 (9%) | |

| Chills | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Pain/arthralgias | 6 (27%) | 1 (5%) | 8 (36%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Fever | 2 (9%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| Hoarseness | 1 (7%) | |||||

| Weight loss | 2 (9%) | 2 (9%) | ||||

| Muscle weakness | 2 (9%) | 2 (9%) | ||||

| Dehydration | 2 (9%) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||||

| Nausea | 1 (7%) | 3 (14%) | 1 (5%) | 6 (27%) | 2 (9%) | |

| Anorexia | 2 (9%) | 3 (14%) | ||||

| Vomiting | 1 (7%) | 2(9%) | 3 (14%) | |||

| Constipation | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| Diarrhoea | 1 (7%) | 5 (23%) | 12 (55%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Abdominal bloating/gas | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (9%) | |||

| Reflux/heartburn | 2 (9%) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 (9%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Skin and eye disorders | ||||||

| Pruritus | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Rash | 2 (14%) | 2 (9%) | ||||

| Dry skin | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Nose bleeding | 1 (5%) | |||||

| Dry eyes | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Central nervous system disorders | ||||||

| Headache | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Memory impairment | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Sensory neuropathy | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Respiratory disorders | ||||||

| Pneumonitis | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| Infusion | ||||||

| Infusion reaction | 1 (5%) | 2 (9%) | ||||

no. number.

*Treatment-related adverse events were defined as any adverse event possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment with pembrolizumab (Part A) or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (Part B).

**A subject that experienced multiple occurrences of an adverse event was counted once at the maximum recorded grade.

Correlative sciences

Companion molecular studies were performed to evaluate tumour PD-L1 status, MSI/MMR status, TMB, as well as pathogenic or likely pathogenic genomic alterations. Results from these studies are summarised in Supplementary Table 1.

Twenty-four of 36 tumours were tested for PD-L1 expression; seven tested tumours (29%) were PD-L1 positive. Given the small sample size and low response rate, the relationship between response to therapy and PD-L1 status could not be determined. Neither tumour that demonstrated a radiographic response by RECIST was tested for PD-L1. Twenty-four other tumours were tested: 5 in patients with stable disease by RECIST (1 PD-L1 positive and 4 PD-L1 negative), 12 with progressive disease (4 PD-L1 positive and 8 PD-L1 negative), and 7 were not evaluable radiologically (2 PD-L1 positive and 5 PD-L1 negative).

Tumour MSI/MMR status was determined during molecular profiling or by IHC (available for 28/36, 78% of cases); TMB was determined during molecular profiling (available for 27/36, 75% of cases). No tumours (N = 28) were found to have microsatellite-high (MSI-H)/dMMR status. Three of 27 tumours (11%) were high-TMB.

Somatic NGS results were available in 31/36 patients (86%). RB1 alteration was noted in 11/31 (35%) tumours: RB1 deletion in 6/11 (55%) tumours and RB1 mutation in 5/11 (45%) tumours. Overall, 23/31 (74%) tumours harboured alterations in TP53; all identified RB1 alterations were co-mutated with TP53. Other genetic alterations identified in some of the tested tumours were site of origin-specific (e.g., KRAS/APC/PIK3CA in colorectal primary tumours, KRAS in pancreatic primary tumours).

Clinical and radiographic responders

One patient in Part A, who had an advanced small-cell carcinoma of salivary origin, achieved a CR by RECIST criteria to treatment with single-agent pembrolizumab. The patient experienced an objective response at the first restaging scan, with CR ongoing at the completion of 34 cycles (2 years) of protocol-based therapy; at last follow-up, the patient remains alive with an OS of greater than 4 years. Companion testing demonstrated the tumour to be microsatellite stable and containing alterations in TP53/RB1/PIK3CA, with a high-TMB (47 mut/Mb); PD-L1 results were not available.

One patient in Part B achieved a RECIST PR, and one patient achieved a near-PR to treatment with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (both patients receiving irinotecan). The patient experiencing a PR had a mixed large-cell NEC-adenocarcinoma of colon primary. A PR was observed at the first restaging scan with a response duration of 29 weeks prior to radiographic disease progression. Companion testing demonstrated the tumour to be microsatellite stable and high-TMB (17.5 mut/Mb), and with a TP53 alteration. NGS identified a mutational signature pattern similar to tobacco-related DNA damage (predominance of G > T/C > A transversions); PD-L1 results were not available. The patient who achieved a near-PR (−29%) in Part B had an EP-PDNEC of unknown primary (Ki-67 40%). Best response to therapy was achieved 19 weeks after initiating pembrolizumab plus irinotecan, and the patient remained on therapy at the time of the data lock, having received 23 cycles of protocol-based treatment. The tumour was microsatellite stable and PD-L1 negative; NGS revealed a low-TMB (3.8 mut/Mb) and a TP53 alteration.

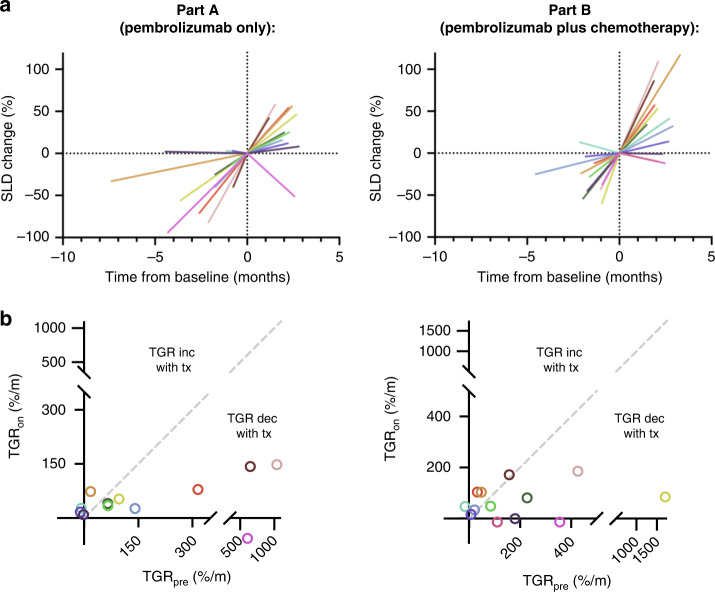

Tumour growth rate

Pre- and on-treatment tumour growth rate (TGRpre and TGRon) were also determined for enrolled patients to further assess for a treatment effect, including hyper-progression. TGRpre and TGRon were available for 12/14 (86%) patients in Part A, and 13/22 (59%) patients in Part B. The median TGRpre across these patients was 97%/month (range, −16 to 1707%/month), with median interval between scans of 1.7 months (range, 0.5–7.4 months). The median TGRon was 47%/month (range, −57 to 186%/month), with a median interval between scans of 2.2 months (range, 1.2–3.3 months). Treatment did not accelerate TGR, and no differences between TGRpre and TGRon were noted in patients that received pembrolizumab alone (P = 0.08), or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (P = 0.15; Fig. 3). In addition, TGRon between the treatment groups was not significantly different (P = 0.61).

Fig. 3. Pre- and on-treatment tumour growth rate.

a Percent (%) change in sum of longest diameters (SLD) of RECIST-defined target lesions over time, for patients treated with (left) pembrolizumab alone or (right) pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. b Pre-treatment tumour growth rate (TGRpre) compared to on-treatment tumour growth rate (TGRon) with (left) pembrolizumab alone, or (right) pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. For Part A and Part B separately, each colour corresponds to an individual patient. TGRpre and TGRon evaluation demonstrated no acceleration of tumour growth during treatment with pembrolizumab alone (P = 0.08), or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (P = 0.15).

Discussion

There is an urgent and unmet need for effective treatments for advanced EP-PDNECs. We conducted a multicenter study of pembrolizumab-based therapy in previously treated biomarker-unselected patients with EP-PDNECs to evaluate for a role of salvage CPI treatment with or without chemotherapy in this disease. We present the results from the first prospective study to investigate the combination of CPI plus chemotherapy in this disease. In this two-part study (initiated before the results of other single-agent CPI studies were available), both pembrolizumab alone and pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy were ineffective. Treatment was associated with a manageable safety profile, with few TRAEs observed in Part A (pembrolizumab alone), and largely expected chemotherapy-related AEs in Part B (pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy).

Tumour MSI-H/dMMR status as well as high-TMB (≥10 mut/Mb) are known predictive biomarkers of response to CPIs, leading to tissue agnostic FDA approvals of CPIs for progressing solid tumours [44–46]. In terms of PDNECs specifically, beyond our clinical trial, there are anecdotal reports of response to CPIs in high-TMB and/or MSI-H EP-PDNECs [47–52]. A subset of treated tumours (N = 28) in this study were tested for MSI and dMMR, and no tumours were MSI-H/dMMR. Three of 27 tested tumours showed high-TMB (47, 17.5 and 10.5 mut/Mb), and two of three patients with high-TMB tumours demonstrated a PR to treatment (one receiving pembrolizumab alone and the other receiving pembrolizumab plus irinotecan). High-TMB status has previously been reported in a portion (7%) of high-grade gastroenteropancreatic NENs, with 4–5% of tumours demonstrating MSI-H status, and in some studies of NENs, prior therapy with alkylating agents, a commonly used treatment for high-grade NENs, has also been associated with increasing TMB [53–56]. Nevertheless, the role of molecular profiling in EP-PDNECs has been controversial in this disease. Taken together, these findings underscore the potential value of assessing these biomarkers in this population given tumour-agnostic drug approvals of pembrolizumab (MSI-H/dMMR or TMB-H) and dostarlimab-gxly (dMMR tumours).

To further characterise the tumours treated in this study, NGS data was compiled and analysed (Supplementary Table 1). Recognising that NGS testing was performed by several CLIA-approved institutional and commercial platforms, our findings are consistent with previously investigation of EP-PDNECs, with many tumours harbouring alterations in either or both TP53/RB1, as well as other somatic genomic alterations that were site of origin-specific (i.e., KRAS/APC/PIK3CA in colorectal primary, KRAS in pancreatic primary) [57, 58]. It was additionally noted that the mutational signature identified from genetic testing of tumour tissue from the patient who achieved a PR to pembrolizumab plus irinotecan was consistent with tobacco-related DNA damage. It is well recognised that CPIs are an active therapy in SCLC, a disease developing due to heavy tobacco use, and response to CPIs in SCLC can be independent of predictive biomarkers [9–15].

Despite the lack of therapeutic activity observed, this multicenter effort has important takeaways for clinical trial conduct in EP-PDNECs. The screen failure rate of 45% (30/66 consented patients rendered ineligible) highlights the challenges associated with the development and execution of clinical trials in this disease. Even in the setting of concurrent chemotherapy, the median PFS for patients treated in Part B was only two months. Such rapid disease progression is potentially problematic in the setting of treatment with CPIs, which may have a delayed effect, sometimes taking several weeks or longer to show a benefit. Our results, as well as the high screen failure rate, in part related to rapidly declining performance status and end-organ function, demonstrate the importance of early referral for clinical trials in this population, including prior to or while on first-line therapy, in an effort to capture eligible patients. While this study was completed in a timely manner, inclusion of tumours arising in several areas of the body almost certainly contributed to significant heterogeneity within the study population (e.g., Ki-67, cell type, mixed tumours, site of origin, prior therapy). Although potentially ideal, there are significant challenges related to completing studies in EP-PDNECs limited to a single site of origin, given the disease rarity.

TGR analyses have previously been undertaken in well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours (NETs); however to our knowledge, they have not been performed in PDNECs [42, 59–62]. While the use of TGR in previously treated patients with EP-PDNECs has not been validated, we performed an exploratory analysis of both TGRpre and TGRon in the tumours treated in this study, to investigate if pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was associated with disease hyper-progression, which has been described previously in cancers treated with CPIs, including a subset of gastrointestinal PDNECs in one retrospective evaluation [63, 64]. Consistent with the clinical behaviour of EP-PDNECs, our analyses demonstrated a markedly higher TGRpre in this population compared to previous reports assessing well-differentiated, low to intermediate-grade, NETs [42, 59]. However, no obvious disease hyper-progression from baseline was observed in treated tumours, and no clear difference in TGRon in tumours treated with pembrolizumab alone compared to pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. As is depicted in Fig. 3, variability was noted in the TGRpre, again, illustrating the high heterogeneity in EP-PDNEC biology. Importantly, the TGR analyses were exploratory; an important caveat is that variability in the interval between pre-enrolment scans likely limited our ability to obtain precise estimates of TGRpre in all patients.

Our findings from this two-part, multicenter, prospective study of (1) pembrolizumab alone and (2) pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (physician’s choice irinotecan or paclitaxel) do not support a role for either of these therapies in the management of previously treated patients with advanced and progressive EP-PDNECs, independent of known predictive response biomarkers to CPIs. Recent prospective and retrospective efforts evaluating the spectrum of well- and poorly differentiated NENs have suggested variable activity with dual CPI therapy, which is most impressive in high-grade NENs, with ORR of up to 26% [18–21, 28, 65]. However, these results need validation, and broader efforts are needed to better define this activity for EP-PDNECs, with a particular focus on companion studies and identification of potential predictors of response (lacking in most previously reported studies). Current ongoing studies of CPIs in previously treated EP-PDNEC include those of dual CPI therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibition (NCT04079712, NCT03866382) and other novel combinations (i.e., CPI plus genetically engineered viruses—NCT03647163). We additionally await the results from the accruing clinical trial of atezolizumab in combination with platinum and etoposide chemotherapy in untreated and metastatic EP-PDNECs (NCT05058651), which evaluates for a role of CPI plus chemotherapy in the first-line setting.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all of the patients participating in this study and their caregivers, along with the investigators and research study teams at UCSF, MSK and DFCI. In addition, we would like to thank Merck for supporting this multicenter study through the Merck Investigator Studies Programme.

Author contributions

NR, JAC and EKB conceived/designed the work that led to this submission, acquired data, and interpreted the results. SJW acquired data and interpreted results. RRA, SC, LF, JG, TAH, KPK, CKM, PNM, KP, DR-L and LZ interpreted the results. AM, SP and SvF acquired the data. All authors of this manuscript participated in drafting and/or revising the manuscript and approved the final manuscript version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by Merck & Co.; additional support provided by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P30CA082103 (USCF), P30CA008748 (MSK), and P30CA006516 (DFCI).

Data availability

The data generated and analysed for this study are available within this manuscript, and the accompanying tables and figures, with the exception of identifiable information. Any additional inquiries should be referred to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

Dr. Nitya Raj: research funding (ITM, Corcept Therapeutics), consulting/advisory boards (Ipsen Pharma, HRA Pharma, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, AAA). Dr. Jennifer Chan: consulting/advisory boards (TerSera, AAA, Curium), honorarium (Ipsen), stock ownership (Merck). Dr. Rahul Aggarwal: research funding (Merck). Dr. Lawrence Fong: research funding (Roche/Genentech, Abbvie, Bavarian Nordic, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dendreon, Janssen, Merck, Partner Therapeutics), advisory boards (Actym, Allector, Astra Zeneca, Atreca, Bioalta, Bolt, Bristol Myer Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Immunogenesis, Innovent, Merck, Merck KGA, Nutcracker, RAPT, Scribe, Senti, Soteria, Sutro, Roche/Genentech). Dr. Thomas Hope: research funding (Clovis Oncology, GE Healthcare, Philips, AAA), consulting (Bayer, Curium, ITM, RayzeBio), advisory boards (Blue Earth Diagnostics, Ipsen), stock ownership (RayzeBio). Dr. Claire Mulvey: research funding (Genentech). Dr. Pamela Munster: research funding (Merck). Dr. Kimberly Perez: consulting/scientific advisory boards (Lantheus, Helsinn/QED). Dr. Diane Reidy-Lagunes: research funding (Merck, Ipsen, Novartis). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) Institutional Review Boards and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent before study enrolment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nitya Raj, Jennifer A. Chan.

Contributor Information

Nitya Raj, Email: rajn@mskcc.org.

Emily K. Bergsland, Email: emily.bergsland@ucsf.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-023-02298-8.

References

- 1.Dasari A, Mehta K, Byers LA, Sorbye H, Yao JC. Comparative study of lung and extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: a SEER database analysis of 162,983 cases. Cancer. 2018;124:807–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shia J, Tang LH, Weiser MR, Brenner B, Adsay NV, Stelow EB, et al. Is nonsmall cell type high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the tubular gastrointestinal tract a distinct disease entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:719–31. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318159371c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volante M, Birocco N, Gatti G, Duregon E, Lorizzo K, Fazio N, et al. Extrapulmonary neuroendocrine small and large cell carcinomas: a review of controversial diagnostic and therapeutic issues. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:665–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–12. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J, Reidy-Lagunes D. The management of extrapulmonary poorly differentiated (high-grade) neuroendocrine carcinomas. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:100–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basturk O, Tang L, Hruban RH, Adsay V, Yang Z, Krasinskas AM, et al. Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:437–47. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strosberg JR, Coppola D, Klimstra DS, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Wiseman GA, et al. The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated (high-grade) extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Pancreas. 2010;39:799–800. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb56f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGarrah PW, Leventakos K, Hobday TJ, Molina JR, Finnes HD, Westin GF, et al. Efficacy of second-line chemotherapy in extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma. Pancreas. 2020;49:529–33. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczesna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2220–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1929–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, Gottfried M, Peters S, Csoszi T, et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo plus etoposide and platinum as first-line therapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-604 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2369–79. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonia SJ, Lopez-Martin JA, Bendell J, Ott PA, Taylor M, Eder JP, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:883–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ready NE, Ott PA, Hellmann MD, Zugazagoitia J, Hann CL, de Braud F, et al. Nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small cell lung cancer: results from the CheckMate 032 randomized cohort. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:426–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung HC, Piha-Paul SA, Lopez-Martin J, Schellens JHM, Kao S, Miller WH, et al. Pembrolizumab after two or more lines of previous therapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic SCLC: results from the KEYNOTE-028 and KEYNOTE-158 studies. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:618–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ott PA, Elez E, Hiret S, Kim DW, Morosky A, Saraf S, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayvergia N, Dasari A, Deng MY, Litwin S, Al-Toubah T, Alpaugh RK, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: joint analysis of two prospective, non-randomised trials. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:1309–14. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao JC, Strosberg J, Fazio N, Pavel ME, Bergsland E, Ruszniewski P, et al. Spartalizumab in metastatic, well/poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28:161–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Patel SP, Othus M, Chae YK, Giles FJ, Hansel DE, Singh PP, et al. A phase II basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 blockade in rare tumors (DART SWOG 1609) in patients with nonpancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2290–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capdevila J, Landolfi S, Hernando J, Teule A, Garcia-Carbonero R, Custodio A, et al. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab in patients with grade 3 neuroendocrine neoplasms of gastroenteropancreatic origin: updated results from the multicenter phase II DUNE trial (GETNE 1601) Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S914–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein O, Kee D, Markman B, Michael M, Underhill C, Carlino MS, et al. Immunotherapy of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors: a subgroup analysis of the CA209-538 clinical trial for rare cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4454–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girard N, Mazieres J, Otto J, Lena H, Lepage C, Egenod T, et al. Nivolumab (nivo) +/- ipilimumab (ipi) in pre-treated patients with advanced, refractory pulmonary or gastroenteropancreatic poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NECs) (GCO-001 NIPINEC) Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S1318. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.2119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SP, Mayerson E, Chae YK, Strosberg J, Wang J, Konda B, et al. A phase II basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 blockade in rare tumors (DART) SWOG S1609: high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm cohort. Cancer Am Cancer Soc. 2021;127:3194–201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen DH, Benner B, Wei L, Sukrithan V, Goyal A, Zhou Y, et al. Efficacy of nivolumab and temozolomide in advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) in a phase 2 clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:4121.

- 24.Riesco-Martinez MC, Capdevila J, Alonso V, Jimenez-Fonseca P, Teule A, Grande E, et al. Nivolumab plus platinum-doublet chemotherapy as first-line therapy in unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic G3 neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NENs) of the gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) tract or unknown (UK) origin: Preliminary results from the phase II NICE-NEC trial (GETNE T1913) Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S908–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capdevila J, Teule A, Lopez C, Garcia-Carbonero R, Benavent M, Custodio A, et al. A multi-cohort phase II study of durvalumab plus tremelimumab for the treatment of patients (pts) with advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) of gastroenteropancreatic or lung origin: the DUNE trial (GETNE 1601) Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S770–S1. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fottner C, Apostolidis L, Ferrata M, Krug S, Michl P, Schad A, et al. A phase II, open label, multicenter trial of avelumab in patients with advanced, metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas NEC G3 (WHO 2010) progressive after first-line chemotherapy (AVENEC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:4103.

- 27.Zhang P, Lu M, Li J, Shen L. Efficacy and safety of PD-1 blockade with JS001 in patients with advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms: a non-randomized, open-label, phase Ib trial. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:468. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy293.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel SP, Mayerson E, Chae YK, Strosberg J, Wang J, Konda B, et al. SWOG S1609-A phase 2 basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 blockade in rare tumors: a high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm cohort. Cancer. 2021;127:3194–201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, et al. Memorial sloan kettering-integrated mutation profiling of actionable cancer targets (MSK-IMPACT) a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:251–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gnirke A, Melnikov A, Maguire J, Rogov P, LeProust EM, Brockman W, et al. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:182–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagle N, Emery C, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Sawyer A, Pochanard P, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3085–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Blumenstiel B, DeFelice M, Pochanard P, et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:82–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niu B, Ye K, Zhang Q, Lu C, Xie M, McLellan MD, et al. MSIsensor: microsatellite instability detection using paired tumor-normal sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1015–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afshar AR, Damato BE, Stewart JM, Zablotska LB, Roy R, Olshen AB, et al. Next-generation sequencing of uveal melanoma for detection of genetic alterations predicting metastasis. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2019;8:18. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.2.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natesan D, Zhang L, Martell HJ, Jindal T, Devine P, Stohr B, et al. APOBEC mutational signature and tumor mutational burden as predictors of clinical outcomes and treatment response in patients with advanced urothelial cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:816706. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.816706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacConaill LE, Garcia E, Shivdasani P, Ducar M, Adusumilli R, Breneiser M, et al. Prospective enterprise-level molecular genotyping of a cohort of cancer patients. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:660–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia EP, Minkovsky A, Jia Y, Ducar MD, Shivdasani P, Gong X, et al. Validation of OncoPanel: a targeted next-generation sequencing assay for the detection of somatic variants in cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:751–8. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0527-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferte C, Fernandez M, Hollebecque A, Koscielny S, Levy A, Massard C, et al. Tumor growth rate is an early indicator of antitumor drug activity in phase I clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:246–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferte C, Koscielny S, Albiges L, Rocher L, Soria JC, Iacovelli R, et al. Tumor growth rate provides useful information to evaluate sorafenib and everolimus treatment in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients: an integrated analysis of the TARGET and RECORD phase 3 trial data. Eur Urol. 2014;65:713–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dromain C, Pavel ME, Ruszniewski P, Langley A, Massien C, Baudin E, et al. Tumor growth rate as a metric of progression, response, and prognosis in pancreatic and intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:66. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamarca A, Crona J, Ronot M, Opalinska M, Lopez Lopez C, Pezzutti D, et al. Value of tumor growth rate (TGR) as an early biomarker predictor of patients’ outcome in neuroendocrine tumors (NET)—the GREPONET study. Oncologist. 2019;24:e1082–e90. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamarca A, Ronot M, Moalla S, Crona J, Opalinska M, Lopez CL, et al. Tumor growth rate as a validated early radiological biomarker able to reflect treatment-induced changes in neuroendocrine tumors: the GREPONET-2 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:6692–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcus L, Lemery SJ, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3753–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andre T, Berton D, Curigliano G, Jimenez-Rodriguez B, Ellard S, Gravina A, et al. Efficacy and safety of dostarlimab in patients (pts) with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) solid tumors: analysis of 2 cohorts in the GARNET study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.2587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su X, Zhou X, Xiao C, Peng W, Wang Q, Zheng Y. Complete response to immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in a patient with gynecological mixed cancer mainly composed of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with high tumor mutational burden: a case report. Front Oncol. 2022;12:750970. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.750970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang NW, Tan KT, Li CF, Kuo YH. Complete and durable response to nivolumab in recurrent poorly differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with high tumor mutational burden. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:4587–96. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28060388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stimes N, Stanbery L, Albrethsen M, Trivedi C, Hamouda D, Dworkin L, et al. Small-cell breast carcinoma with response to atezolizumab: a case report. Immunotherapy. 2022;14:669–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Ricco B, Salati M, Reggiani Bonetti L, Dominici M, Luppi G. PD-1 blockade in deficient mismatch repair mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the stomach: new hope for an orphan disease. Tumori. 2020;106:NP57–NP62. doi: 10.1177/0300891620952845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stueger A, Winder T, Tinguely M, Petrausch U, Helbling D. Metastatic mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon with response to immunotherapy with pembrolizumab: a case report. J Immunother. 2019;42:274–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitman J, Kardosh A, Diaz L, Jr, Fong L, Hope T, Onodera C, et al. Complete response and immune-mediated adverse effects with checkpoint blockade: treatment of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–7. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puccini A, Poorman K, Salem ME, Soldato D, Seeber A, Goldberg RM, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5943–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venizelos A, Elvebakken H, Perren A, Nikolaienko O, Deng W, Lothe IMB, et al. The molecular characteristics of high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;29:1–14. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raj N, Shah R, Stadler Z, Mukherjee S, Chou J, Untch B, et al. Real-time genomic characterization of metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors has prognostic implications and identifies potential germline actionability. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Sun F, Grenert JP, Tan L, Van Ziffle J, Joseph NM, Mulvey CK, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy to treat temozolomide-associated hypermutation in advanced atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2200009. doi: 10.1200/PO.22.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SM, Sung CO. Comprehensive analysis of mutational and clinicopathologic characteristics of poorly differentiated colorectal neuroendocrine carcinomas. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yachida S, Totoki Y, Noe M, Nakatani Y, Horie M, Kawasaki K, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal system. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:692–711. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dromain C, Loaiza-Bonilla A, Mirakhur B, Beveridge TJR, Fojo AT. Novel tumor growth rate analysis in the randomized CLARINET study establishes the efficacy of lanreotide depot/autogel 120 mg with prolonged administration in indolent neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2021;26:e632–e8. doi: 10.1002/onco.13669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weisbrod AB, Kitano M, Thomas F, Williams D, Gulati N, Gesuwan K, et al. Assessment of tumor growth in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in von Hippel Lindau syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dromain C, Sundin A, Najran P, Vidal Trueba H, Dioguardi Burgio M, Crona J, et al. Tumor growth rate to predict the outcome of patients with neuroendocrine tumors: performance and sources of variability. Neuroendocrinology. 2021;111:831–9. doi: 10.1159/000510445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pettersson OJ, Fross-Baron K, Crona J, Sundin A. Tumor growth rate in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor patients undergoing PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE. Endocr Connect. 2021;10:422–31. doi: 10.1530/EC-21-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ji Z, Peng Z, Gong J, Zhang X, Li J, Lu M, et al. Hyperprogression after immunotherapy in patients with malignant tumors of digestive system. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:705. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5921-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramon-Patino JL, Schmid S, Lau S, Seymour L, Gaudreau PO, Li JJN, et al. iRECIST and atypical patterns of response to immuno-oncology drugs. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e004849. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Al-Toubah T, Halfdanarson T, Gile J, Morse B, Sommerer K, Strosberg J. Efficacy of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100364. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed for this study are available within this manuscript, and the accompanying tables and figures, with the exception of identifiable information. Any additional inquiries should be referred to the corresponding author.