Abstract

Background:

The treatment of psychiatric patients has suffered a major change over the last decades, with long-term hospitalizations being replaced by short-term stays and appropriate aftercare in outpatient services. Some chronically ill patients exhibit a pattern of multiple hospitalizations, designated as the Revolving Door (RD) phenomenon.

Aims:

This review aims to analyse the existing literature regarding sociodemographic, clinical and other factors associated with multiple hospitalizations in psychiatric facilities.

Method:

The search performed in the PubMed database for the terms revolving[Title] AND (psyc*[Title] OR schizo*[Title] OR mental[Title]) presented 30 citations, 8 of which met the eligibility criteria. Four other studies found in references of these articles were also included in the review.

Results:

Albeit the use of different criteria to define the RD phenomenon, it is more likely to be associated with patients who are younger, single, with low educational level, unemployed, diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, particularly schizophrenia, and with alcohol and/or substance use. It is also associated with a younger age on disease onset, suicidality, noncompliance and voluntary type of admission.

Conclusion:

Recognizing patients with a RD pattern of admissions and prediction of rehospitalization can help the development of preventive intervention strategies and identify potential limitations in existing health care delivery systems.

Keywords: Revolving door, admission, homeless, psychiatry, hospital, inpatient

Introduction

The treatment of psychiatric disorders has suffered a drastic change in the second half of the last century. Psychiatric patients were normally treated with long-stay hospitalizations (Wing, 1981). However, the introduction of new psychiatric drugs and the development of better outpatient resources has allowed for a community-based care (Gastal et al., 2000).

Long-term hospitalizations have been replaced with short-term admissions followed by appropriate aftercare (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b). During the last decades the number of beds in psychiatric hospitals has notably decreased (Neto & da Silva, 2008).

Some chronically ill patients exhibit a pattern of multiple hospitalizations and discharges from psychiatric wards, designated as the ‘Revolving Door’ (RD) phenomenon (Marsh et al., 1981). Psychiatric hospitalizations occurs for many reasons but will often reflect the inability of the individual’s environment and support system to meet specific needs (Lichtenberg et al., 2008).

Several studies have tried to analyse the RD pattern of hospitalizations and identify possible associated factors, but different definitions have been used to describe it (Gastal et al., 2000).

Albeit different criteria have been used to define the RD patient, the term generally refers to patients who require a large amount of mental health service resources (20%–30%) due to repeated hospitalizations, though they only represent less than 10% of the total number of patients (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). The emphasis on deinstitutionalization has increased the risk of frequent readmissions in many patients, now treated in the community (Oyffe et al., 2009).

There has been considerable research aiming to identify factors associated with multiple hospitalizations. However, the leading factors associated with the RD phenomenon are still controversial (Koparal et al., 2021).

This systematic review aims to analyse the existing literature regarding the factors associated with the RD phenomenon. Comprehension of this phenomenon allows for a better understanding of the type of patients who are more likely to be readmitted, predict the risk of rehospitalization and identify potential limitations in existing health care delivery systems or specific deficits in available treatment resources (Neto & da Silva, 2008).

Methods

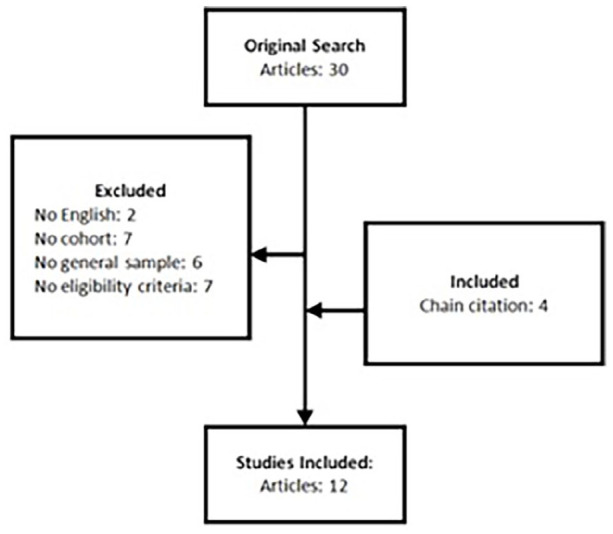

The search was performed in the PubMed database on April 2021 for the terms revolving[Title] AND (psyc*[Title] OR schizo*[Title] OR mental[Title]), following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The eligibility criteria included studies that aimed to identify patients’ variables associated with multiple hospitalizations in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Criteria for exclusion included non-English publications, non-cohort studies, namely review articles, descriptive papers, letters to the editor or qualitative thematic analyses, and studies of a specific population, namely specific age groups or diagnosis. Out of 30 articles found, 8 met the eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review. Based on the references of these studies, four other articles were found to be eligible, and therefore also included in this review. A summary of the study Methods (PRISMA) is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Articles selection for the systematic review about the revolving door phenomenon in severe psychiatric disorders.

Results

All the articles included in this review were cohort studies, whether longitudinal, cross-sectional or chart review studies. Most of them analysed patient’s variables by comparing RD patients with non-RD patients, whether they were matched control groups, or the remaining patients admitted during the same follow-up period that didn’t meet the RD criteria. Using chi-square test for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables, the authors identified the factors associated with multiple hospitalizations, if the difference between groups was statistically significant. Some authors also used logistic regression analysis to evaluate prognostic factors predicting multiple hospitalizations.

One author employed a different approach: using four different statistical models, they analysed the impact of patients’ factors in the number of hospitalizations and length of time to readmission (TIC = Time In Community), calculated as the difference between a discharge date and a subsequent readmission (Frick et al., 2013). Tables 1 and 2 resume the main findings of the present review.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the systematic review regarding revolving door phenomenon in severe psychiatric disorders.

| Author (year) | Name | Country | Type | Aim of study | Size of cohort | Nr. of females | Nr. of males | Length of follow-up | Collected data | Definition of revolving door | Admission/year | % of cohort considered RD patients | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woogh et al. (1977) | Psychiatric hospitalization in Ontario: the revolving door in perspective | Canada | Longitudinal cohort study | Trace the pattern of readmission and the characteristics of patients at risk of readmission in a cohort of patients with their first episode of mental illness treated in an inpatient unit in 1969 | 1,436 | Not specified | Not specified | 4 years | Type of admission, sex, age, marital status, whether born in Canada or year of arrival, education level, occupation, principal psychiatric diagnosis (ICDA), type of separation and final psychiatric diagnosis | Readmission: ⩾2 admissions; Multiple admissions: ⩾3 admissions (in 4 years) | 3/4 = 0.75 | 8% | Greater proportion of multiple readmissions in young patients, aged between 16 and 24 years. Functional psychoses, especially schizophrenia, is associated with readmission. |

| Kastrup (1987a, 1987b) | Who became revolving door patients? | Denmark | Longitudinal cohort study | Delineate the revolving door population, analyse the possibility of an early identification of patients needing multiple admissions and to identify variables associated with the outcome ‘revolving door’ | 12,737 | 6,856 | 5,881 | 10 years | Marital status, place of residence and birth, date of admission and discharge, referral from, admission from, manner of admission, discharge to and referral to, previous admission and main and sub diagnosis (ICD-8) | Revolving door population defined as: (1) ⩾4 admissions in 10 years + no admission or discharge period lasting for more than 2.5 year; (2) ⩾4 admissions during the first 2.5 year after first admission | (1) 4/10 = 0.40; (2) 4/2.5 = 1.60 | 11% | RD phenomenon associated with: male gender; young age (particularly between 15 and 24 years); being single or divorced (as opposed to married or widow); living in a large city; having schizophrenia, personality disorder, alcohol or substance abuse; being discharged from and to an outpatient clinic or their own home. |

| Haywood et al. (1995) | Predicting the ‘Revolving Door’ Phenomenon among patients with Schizophrenic, Schizoaffective and Affective Disorders | USA | Cross sectional study | Examine the relationships among demographic features, diagnostic characteristics and frequency of hospitalization of State Hospital inpatients with Schizophrenic, Schizoaffective and Affective disorders | 135 | 49 | 86 | – | Age, race, gender, years of education, marital status, RDC diagnosis, housing problems, money problems, family problems, criminal and/or violent behaviour, noncompliance to treatment, alcohol/drug problems, life events and substance use | 4 level categorical variable: 1 hospitalization, 2–4, 5–10 and >10 hospitalizations (in their lifetime) | Cannot be calculated | 56% of cohort with ⩾5 hospitalizations | Higher number of hospitalizations associated with: male gender; alcohol/drug problems; medication noncompliance. |

| Gastal et al. (2000) | Predicting the revolving door phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, affective disorders and non-organic psychosis | Brazil | Cross sectional study | Identify the variables that predict the revolving door phenomenon in a psychiatric hospital at the moment of a second admission in patients with schizophrenic, affective disorders and non-organic psychosis (ICD-9) | 3,091 | 1,925 | 1,166 | 5–24 years after first admission | Gender, race, age group, marital status, occupation, place of origin, diagnosis, mean period of stay on the first admission, length of time between the first and second admissions | Recidivist patients: ⩾4 admissions during follow-up (5–24 years). Non-recidivists: 2 or 3 admissions during follow-up | Cannot be calculated | 38.6% | Recidivism associated with: male gender; younger age (particularly between 13 and 35 years); being single (as opposed to married); having schizophrenia (as opposed to affective disorders and other forms of psychosis); having a longer length of stay at first admission (> 41 days); being readmitted before 2 years (730 days) after first admission. Predictor variables: age between 13 and 35 years; schizophrenia; being readmitted before 360 days after first admission; length of stay at first admission >60 days. |

| Bobo et al. (2004) | Characteristics of repeat users of an inpatient psychiatry service at a large military tertiary care hospital | USA | Longitudinal cohort study | Identify clinical and demographic variables that correlated with readmission to a psychiatric inpatient service | 814 | 319 | 495 | 13 months | Age, military status, military rank, highest level of education, marital status, number of children, employment status, legal problems, DSM-IV diagnosis, substance abuse history, history of physical and/or sexual abuse, age at onset of psychiatric problems, legal status on admission (type of admission), length of hospital stay, total number of admissions during the study time and lifetime admissions | Repeat users: ⩾2 inpatient admissions during 13 months | 2/1.08 = 1.85 | 14% | Rehospitalization was associated with: unemployment; less than high school education; having no children; history of childhood psychiatric problems; present or past involvement with the legal system; history of alcohol/substance use problems; psychotic disorders and mood disorders other than bipolar disorder; longer length of stay at first admission. Predictor variables: history of past psychiatric hospitalization; age of disease onset before age 18. |

| Neto and da Silva (2008) | Characterization of readmissions at a Portuguese psychiatric hospital: An analysis over a 21-month period | Portugal | Longitudinal cohort study | Characterize the population with repeated admissions, in comparison to patients with single admissions | 2,440 | Not specified | Not specified | 21 months | Sex, age, nationality, marital status, scholar, professional status, psychiatric diagnosis, previous treatments | Readmission: ⩾2 admissions during 21 months | 2/1.75 = 1.14 | 19.9% | Readmission associated with: younger age; being single; unemployment; having schizophrenic psychosis and personality disorders (as opposed to other psychosis, neurosis and adjustment disorders and dementias and organic conditions) |

| Oyffe et al. (2009) | Revolving-door patients in a public psychiatric hospital in Israel: Cross sectional study | Israel | Cross sectional study | Study social, demographic, clinical and forensic profiles of frequently re-hospitalized (revolving door) psychiatric patients, and compared them with two control groups of non-revolving door patients | 1,239 | 536 | 703 | 2 years | Sex, age, marital status, place of residence, religious affiliation, diagnosis, number of previous admissions, duration of first hospitalization, duration of time between first and second hospitalization, number of admissions during the study period, mean length of lifetime hospitalizations, department at the time of discharge, place and type of discharge, type of ambulatory treatment, type of medication, frequency of outpatient visits, history of aggression, suicidal behaviour, use of illegal drugs and alcohol | Revolving Door (RD): ⩾3 admissions during a 2 years period | 3/2 = 1.5 | 14.7% | RD phenomenon associated with: lower history of physical violence; less involuntary hospitalizations; being discharged against medical advice; less mean days of lifetime hospitalizations; shorter mean intervals between first and second admission. Predictor variables: history of physical violence; discharge against medical advice; the interval between the first and second hospitalization |

| Schmutte et al. (2009) | Characteristics of inpatients with a history of recurrent psychiatric hospitalizations: A matched-control study | USA | Chart review study | Examine the association between patient characteristics and inpatient hospitalization among patients with a history of recurrent psychiatric hospitalizations (two or more hospitalizations in the 18 months before the index hospitalization) and patients without such a history | 150 | 80 | 70 | 18 months | Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, housing status, family history of mental illness or substance abuse, principal diagnosis, substance abuse, GAF score, length of index hospitalization, no. hospitalizations in previous 18 months | Recurrent admissions: ⩾3 within 18 months | 3/1.5 = 2 | 50% | Recurrent admissions associated with: psychotic disorders; substance abuse; lack of education. Predictor variables: unemployment; psychosis (as opposed to affective or other disorders); number of hospitalizations in the 24 months prior to admission |

| Morlino et al. (2011) | Use of psychiatric inpatient services by heavy users: findings from a national survey in Italy | Italy | Longitudinal cohort study | Analyse factors associated with a patient’s probability of being a Heavy User (HU) of inpatient psychiatric services and to compare the HU inpatient population with Non-Heavy Users (NHUs) | 1,075 | 530 | 545 | 12 months | Sex, age, nationality, marital status, occupational status, educational status, living situation, diagnostic group, number of lifetime admissions, age at first-ever admission, any compulsory admission, previous admission to a mental hospital, previous admission to a forensic mental hospital, place of treatment in month prior to admission, symptom pattern in week prior to admission, reasons contributing for admission, other characteristics of last admission, BPRS-score and PSP-score | Heavy Users (HU): ⩾3 admissions in 12 months | 3/1 = 3 | 40.5% | Heavy use of psychiatric service associated with: younger age (particularly between 16 and 45 years); being unmarried; unemployed; receiving disability pension; being homeless or living in a residential facility; having organic mental disorders or personality disorders, particularly borderline/instable personality disorder (as opposed to affective disorder (manic/bipolar and depressive disorder)); younger age of disease onset (<30 years); lower PSP score; in treatment for psychiatric problems in the month prior to admission; episodes of alcohol-abuse, lack of self-care and having been a victim of violence in the week prior to admission (as opposed to having symptoms of depression and inhibition); having conflicts with partners and/or family in the week prior to admission; >11 admissions in their lifetime. Predictor variables: age; age of disease onset; number of lifetime admissions; having been victim of violence in the week prior to admission. |

| Frick et al. (2013) | The revolving door phenomenon revisited: Time to readmission in 17,415 patients with 37,697 hospitalizations at a German psychiatric hospital | Germany | Longitudinal cohort study | Analyse impact factors on the process of rehospitalization after discharge from inpatient psychiatric treatment, namely the number of hospitalizations and the time to readmission; and compare four statistical models specifically designed for recurrent event history analysis | 17,415 | Not specified | Not specified | 12 years | Sex, higher educational level, early onset, number of psychiatric hospitalizations, main diagnosis per hospitalization (ICD-10), current age at discharge, status of living in a stable partnership, social integration (employment status, living arrangement), involuntary admission, length of preceding hospital stay, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) at discharge, referral to a general practitioner or to outpatient clinic, historical year | Not defined. The study aimed to analyse the impact of patients’ characteristics on the number of hospitalizations and time to readmission (TIC = Time in Community) | Cannot be calculated | Cannot be calculated | Risk factors for rehospitalization: affective disorders with longer course of illness; living in urban surroundings; referral to the hospital’s own outpatient clinic. Protective variables: older age; employment; higher education level; living in an institutionalized or precarious setting (‘no private housing’); diagnosis of neurotic and somatoform disorders and behavioural syndromes; high GAF score; involuntary hospitalization; outpatient care a general practitioner; longer lengths of stay. Accelerated rehospitalization associated with: higher total number of admissions and co-diagnosis with substance abuse disorder. |

| di Lorenzo et al. (2016) | The revolving door phenomenon in an Italian acute psychiatric ward: A 5-year retrospective analysis of the potential risk factors | Italia | Longitudinal cohort study | Describe the variables and potential risk factors related to Revolving Door (RD) phenomenon; highlight the potential RD risk factors related to more frequent readmissions | 105 | 47 | 58 | 5 years | Demographic (gender, age, nationality); environmental (family and home environment, work activity, social and economic condition); clinical curse (reasons for admission, psychiatric diagnosis ICD-9-CM, substance abuse or dependence and organic comorbidity, aggressive behaviour); modalities of care (oral and long-acting drugs, therapeutic compliance, voluntary and involuntary hospitalization, duration of hospitalization, period to readmission, reasons for ending follow-up, destination at discharge) | RD patients: ⩾3 ‘RD Hospitalizations’ (RDH) in 1 year. Divided in two groups: high (⩽5 admissions in 5 years) and extremely high (>5 admissions in 5 year) utilizers | 3/1 = 3 | 5.7% of all patients admitted | RD phenomenon associated with: violence/suicidality; long acting therapy (suggesting less compliance); less involuntary hospitalizations; longer admissions. Risk factors: receiving disability pension; manic episode in bipolar disorder, personality disorders; substance abuse/dependence; aggressive behaviour during hospitalization; outpatient care in both the medical health service and a substance use service or in a rehabilitative program; short time to readmission Protective factors: marital family; sufficient social and economic condition; presence of organic comorbidity; involuntary hospitalization. |

| Koparal et al. (2021) | Revolving door phenomenon and related factors in Schizophrenia, Bipolar Affective Disorder and other psychotic disorders | Turkey | Longitudinal cohort study | Retrospectively evaluate the risk factors of frequent hospitalizations and compare the clinical, sociodemographic, and treatment-related characteristics of RDP (revolving door phenomenon) patients to SH (single hospitalization) patients | 132 | 55 | 77 | 5 years | Sociodemographic (age, marital status, employment status, education level, place of residence); clinical data (substance use, psychiatric comorbidity, other medical diseases, family history of the psychiatric disease, age of onset, total number of hospitalizations, average length of stay, type of admission, compliance, reason for hospitalization, suicidal attempts, tendency to violence, forensic events, disability pension, ICD-10 diagnoses); treatment-related data (drugs used, ECT, depot drug use, side effects of drugs, chemical restraint) | RDP defined as (1): ⩾3 hospitalizations in 18 months; or (2): ⩾2 hospitalizations in 12 months and treated with clozapine; or (3): ⩾2 hospitalizations in 12 months and a hospitalization period longer >120 days | 3/1.5 = 2 | 55% | RD phenomenon associated with: male gender; earlier onset of disease; higher rates of forensic events; higher rates of suicidal attempts; higher rates of ECT history, multiple drug treatment regimens, history of clozapine use and use of atypical antipsychotic use; less regular follow-up; and follow-up in centres other than the University outpatient clinic. Predictor variables: history of ECT, suicide attempts, multiple drug use in the treatment regimen, clozapine use and compliance to follow up after discharge. |

Table 2.

Studies results regarding the association between the revolving door phenomenon and severe psychiatric patients’ factors.

| Woogh et al. (1977) | Kastrup (1987a, 1987b) | Haywood et al. (1995) | Gastal et al. (2000) | Bobo et al. (2004) | Neto and da Silva (2008) | Oyffe et al. (2009) | Schmutte et al. (2009) | Morlino et al. (2011) | Frick et al. (2013) | di Lorenzo et al. (2016) | Koparal et al. (2021) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | Analysed | Results | |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | ✓ | Younger, 16–24 | ✓ | Younger, 15–24 | ✓ | Younger, 13–35 | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Younger | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Younger, 16–45 | ✓ | Higher age is protective | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ||

| Gender | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Males | ✓ | Males | ✓ | Males | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Males |

| Ethnicity/Nationality | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ||||||||||

| Place of residence/living arrangement | ✓ | Large cities | ✓ | NS associated with housing problems | ✓ | NS for place of residence | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Homeless or residential facility | ✓ | Urban surrounding; less risk if no private housing | ✓ | NS for home environment | ✓ | NS for place of residence | ||||||||

| Marital status | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Single or divorced | ✓ | No linear association | ✓ | Single | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Single | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Unmarried | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Marital status is protective | ✓ | NS | ||

| Having children | ✓ | No children | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education level | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Less than high school | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Lack of education | ✓ | Lower education (middle-school only) | ✓ | Higher education status is protective | ✓ | NS | ||||||||

| Employment status | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Unemployed | ✓ | Unemployed | ✓ | Unemployed | ✓ | Unemployed; receiving disability pension | ✓ | Employment is protective | ✓ | Disability pension is risk factor | ✓ | NS | ||||||

| Social/economic status | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Sufficient social and economic status is protective | ||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis | ✓ | Functional psychosis (ICD-8) | ✓ | ✓ (ICD-8) | ✓ | NS (RDC) | ✓ | Schizophrenia (ICD-9) | ✓ | Psychotic disorders; mood disorders other than bipolar disorder (DSM-4) | ✓ | Schizophrenic psychosis; personality disorders (ICD-9) | ✓ | NS (ICD-10) | ✓ | Psychotic disorders | ✓ | Organic mental disorders; personality disorders (ICD-10) | ✓ | Affective disorders with longer course of illness (ICD-10) | ✓ | Manic episode in bipolar disorder; personality disorders (ICD-9-CM) | ✓ | NS (ICD-10) |

| Alcohol and/or substance use | ✓ | NS | ✓ | ✓ (ICD-8) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NS (ICD-9) | ✓ | NS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NS | ||

| Age of onset/first hospitalization | ✓ | History of childhood psychiatric problems | ✓ | Younger age at first admission | ✓ | First admission before age of 21: NS | ✓ | Younger age of onset | ||||||||||||||||

| BPRS-score | ✓ | NS | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PSP-score | ✓ | Lower score | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| GAF score | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Higher score is protective | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Criminal and/or violent behaviour | ✓ | Criminal record - NS | ✓ | Involvement with legal system | ✓ | Physically violent behaviour lower in the RD group | ✓ | Violence/suicidality; aggressiveness during hospitalization | ✓ | Forensic events: ✓ Violent tendencies: NS |

||||||||||||||

| Suicidal behaviour | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Violence/suicidality | ✓ | History of suicide attempts | ||||||||||||||||||

| Organic comorbidity | ✓ | Protective | ✓ | NS | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Family history of mental illness | ✓ | NS | ✓ | NS | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Treatment related factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of treatment | ✓ | Long-acting therapy in ‘extremely high users’ | ✓ | Higher rates of ECT history, multiple drug treatment regimens, history of clozapine use | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Compliance to treatment | ✓ | Noncompliance to medication | ✓ | Less regular follow-up | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Factors related with service utilization | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outpatient care | ✓ | Outpatient clinic or their own home; less likely in a somatic ward | ✓ | More likely to be treated in the month prior to admission; emergency services were more frequently involved | ✓ | Referral to hospital’s outpatient clinic is risk factor; referral to a general practitioner is protective | ✓ | Outpatient care: mental health services + substance use service or rehabilitative programs. | Follow-up in centres other than the University outpatient clinic | |||||||||||||||

| Type of admission | ✓ | NS | ✓ | Voluntary | ✓ | Involuntary is protective | ✓ | Voluntary (involuntary admission is protective) | ✓ | NS | ||||||||||||||

| Discharge | ✓ | Against medical advice | ✓ | Transfer to another psychiatric ward and no post-discharge destination due to ‘self-discharge’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Length of hospitalization | ✓ | Significantly longer time hospitalized (cumulative) | ✓ | Longer length of first admission (>41 days) | ✓ | Longer length of stay in first admission | ✓ | Shorter lifetime hospitalizations; length of first admission NS | ✓ | Longer index hospitalization | ✓ | Longer lengths of stay as a protective effect | ✓ | Longer admissions | ✓ | NS | ||||||||

| Length of time between first and second admissions | ✓ | Less than 2 years (730 days) | ✓ | Shorter | ✓ | Shorter initial TIC durations | ✓ | Time to readmission NS | ||||||||||||||||

Definition of revolving door (RD)

Some authors defined RD patients, patients with multiple admissions, recidivists, heavy users or a similar term for those who had a minimum number of hospitalizations in a particular period of follow-up (Bobo et al., 2004; di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Gastal et al., 2000; Morlino et al., 2011; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Schmutte et al., 2009; Woogh et al., 1977). One study divided their cohort in four category levels, according to the number of lifetime hospitalizations (Haywood et al, 1995).

Kastrup (1987a, 1987b) defined the RD population as (Type 1): at least four admissions in a 10-year period, with no admission or discharge period lasting more than 2.5 years; or (Type 2): at least four admissions during the first 2.5 years after first admission.

In Koparal et al., the RD phenomenon was defined as (1): at least three hospitalizations in an 18-month period; or (2): at least two hospitalizations in a 12-month period and receiving treatment with clozapine; or (3): at least two hospitalizations in a 12-month period and a hospitalization with duration longer than 120 days (Koparal et al., 2021).

There is no definition of the RD phenomenon in the work by Frick et al. (2013), as they used a different approach for cohort analysis.

Despite the different definitions for the RD phenomenon, in order to draw conclusions from the articles included in this review, the number of admission/year was calculated for each study based on the number of admissions in a particular follow-up period. The mean number of admission/year was 1.72 (SD 0.85). This number could not be calculated in two of the studies because they lacked a fixed period of follow-up (Haywood et al., 1995; Gastal et al., 2000), and in one other study in which a minimum number of hospitalizations wasn’t defined to characterize the RD patient (Frick et al., 2013).

Analysing the factors associated with the RD phenomenon

Patients’ variables analysed in these articles can be divided classified in sociodemographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity/nationality, place of residence/living arrangement, marital status, having children, educational level, employment status and social/economic status), clinical factors (diagnosis, alcohol and/or substance use, severity of symptoms, level of functioning, criminal and/or violent behaviour, suicidality, organic comorbidity and family history of mental illness), treatment related factors (type of treatment and compliance) and factors related with healthcare service use (place of outpatient care, type of admission, type of discharge, length of admission and length of time between hospitalizations).

Sociodemographic factors

All studies included in this review analysed the relation between patients’ age and rehospitalization. Five of those studies revealed that the RD phenomenon is greater among younger age groups (Gastal et al., 2000; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b; Morlino et al., 2011; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Woogh et al., 1977), particularly those aged between 15 and 24 years (Kastrup, 1987a, Kastrup 1987b; Woogh et al., 1977), 15 and 35 years (Gastal et al., 2000) or 16 and 45 years (Morlino et al., 2011), and one study suggests that older age is a protective variable, associated with lower readmission risk (Frick et al., 2013). Five studies concluded that there was no significant difference regarding age between RD patients and non-RD patients (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Bobo et al., 2004; Koparal et al., 2021; Oyffe et al., 2009; Schmutte et al., 2009).

Males were more likely to have multiple hospitalizations, according to some authors (Gastal et al., 2000; Haywood et al., 1995; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b,Koparal et al., 2021) but the majority of the studies concluded that neither gender was significantly associated with the RD phenomenon (Bobo et al., 2004; di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Frick et al., 2013; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Schmutte et al., 2009; Woogh et al., 1977).

None of the seven studies analysing ethnicity or nationality identified an association between these factors and rehospitalization (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Gastal et al., 2000; Haywood et al., 1995; Morlino et al., 2011; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Schmutte et al., 2009; Woogh et al., 1977).

RD seems to be an urban phenomenon (Frick et al., 2013; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b). Regarding living arrangement, there is a divergence in the literature. One study associated being homeless or living in a residential facility with high utilization of inpatient psychiatric services (Morlino et al., 2011), whereas another associated living in an institutionalized or precarious setting (‘no private housing’) with a diminished risk for rehospitalization (Frick et al, 2013). However, place of residence was not statistically significant in five other studies (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Haywood et al., 1995; Koparal et al., 2021; Oyffe et al., 2009; Schmutte et al., 2009).

Six studies found the association between marital status and rehospitalization not statistically significant (Frick et al., 2013; Haywood et al., 1995; Koparal et al., 2021; Oyffe et al., 2009; Woogh et al., 1977). Nonetheless, rehospitalization occurs more frequently in single or unmarried patients according to five other authors (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Gastal et al., 2000; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b; Morlino et al., 2011) and in patients with no children (Bobo et al., 2004).

These results concerning family environment are consistent with other findings by one of these studies, pointing that non-heavy users of psychiatric services were more frequently accompanied to the hospital by family members, and that admission was made more frequently upon request by a family member (Morlino et al., 2011). In one study, familial relational conflicts were one of the conditions most frequently associated with readmissions (di Lorenzo et al., 2016) particularly if they were present during the week prior to admission (Morlino et al., 2011). Being a victim of violence (mostly verbal threat) was also associated with the RD phenomenon (Morlino et al., 2011).

Patients with recurrent admissions were more likely to have lower educational level, namely having less than high school degree (Bobo et al., 2004; Morlino et al., 2011; Schmutte et al., 2009). Higher educational level was considered a protective variable against readmission (Frick et al., 2013). Some studies found this variable not statistically significant (Haywood et al., 1995; Koparal et al., 2021; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Woogh et al., 1977).

Rehospitalization is associated with unemployment (Bobo et al., 2004; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Schmutte et al., 2009), and receiving a disability pension (Morlino et al., 2011), a risk factor for the RD phenomenon (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). Being employed and having a sufficient social and economic status display a protective effect against rehospitalization (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Frick et al., 2013). No statistical significance was found regarding employment status in three of the studies (Gastal et al., 2000; Koparal et al., 2021; Woogh et al., 1977), as well as for money problems in another study (Haywood et al., 1995).

Psychiatric diagnosis

The authors used different manuals for classification of mental disorders, namely the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), the 8th, 9th and 10th revision of the International Criteria of Diseases (ICD) and the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which imposes a limitation to the conclusions drawn regarding patients’ diagnosis. However, psychiatric diagnosis composed an important factor associated with the RD phenomenon.

RD patients were significantly more likely to have the diagnoses of schizophrenia, personality disorder, alcohol or substance abuse and were less likely diagnosed with organic psychosis or neurosis (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b). Based on a multiple contingency analysis with the outcome RD as the dependent variable and patients’ characteristics as independent variables, Kastrup sorted a list including all possible combinations of the determining variables of the RD phenomenon and identified the most probable RD patient profiles. These include: all young patients with schizophrenia, regardless of gender or place of residence; 25- to 44-year-old male patients with senile/cerebrovascular psychoses; 15- to 24-year-old females with personality disorders; all young patients with alcohol and substance abuse, particularly those living in large cities; 15- to 24-year-old patients with manic-depressive psychosis; and 45- to 64-year-old females with manic-depressive psychosis living in large cities (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b).

Psychotic disorders were found to be associated with multiple hospitalizations in six of these studies (Bobo et al., 2004; Gastal et al., 2000; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Schmutte et al., 2009; Woogh et al., 1977) particularly schizophrenia (Gastal et al., 2000; Neto & da Silva, 2008; Woogh et al., 1977).

Three studies found an association between personality disorders and the RD phenomenon (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Morlino et al., 2011; Neto & da Silva, 2008), particularly borderline personality disorder (Morlino et al., 2011).

Regarding affective disorders, the results are contradictory. As already mentioned, Kastrup identified 15- to 24-year-old patients with manic-depressive psychosis (according to ICD-8) as one of the profiles most at risk of becoming RD patients (Kastrup 1987a, 1987b). Another author pointed that manic episode in bipolar disorder was one of the most relevant risk factors for ‘extremely high utilizers’ of inpatient facilities (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). According to Bobo et al. (2004), affective disorders other than bipolar disorder are associated with rehospitalization, and that patients with bipolar disorder had a significantly lower risk of readmission for reasons the authors suspect associated with overall characteristics of the selected sample.

Conversely, the results from Morlino et al. (2011) associate affective disorder (bipolar and depressive disorder) with non-heavy users of psychiatric services, and these patients were more likely to experience symptoms of depression and inhibition during the week prior to admission, compared to heavy users.

According to Frick et al. (2013), affective disorders correlated with longer periods of time to readmission. However, this protective effect is lost in later stages of the illness, meaning that the time to readmission gets shortened, thus suggesting an increased risk of rehospitalization over the course of affective disorders.

Organic mental disorders were associated with multiple hospitalizations (Morlino et al., 2011), and 25- to 44-year-old male patients with senile/cerebrovascular psychoses constituted one of Kastrup’s RD patient profiles, even though RD patients were less likely diagnosed with organic psychosis or neurosis (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b).

Diagnostic characteristics were not significantly associated with frequency of hospitalization in three of these studies (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Haywood et al., 1995; Koparal et al., 2021). However, the cohort of Haywood et al. comprised only patients with RDC diagnosis of schizophrenic, schizoaffective and affective disorders, and Koparal et al. analysed only patients with psychotic disorders, so comparison with other groups of diagnoses is not possible.

Substance use

Seven studies identified alcohol and/or substance use as an important risk factor associated with the RD phenomenon (Bobo et al., 2004; di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Frick et al., 2013; Haywood et al., 1995; Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b; Morlino et al., 2011). According to Haywood et al. (1995), it is one of the most important factors associated with increasingly more frequent readmissions.

For Kastrup, RD patients were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with alcohol or substance abuse, and those aged 25 to 44 years were particularly at risk. It was worth noticing that males with abuse became revolving door patients at a later age than females with the same diagnosis (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b).

Frick et al. found a highly increased risk of readmission in patients with comorbid substance use disorders. A (transient or incident) co-diagnosis of any substance abuse disorder was consistently associated with an accelerating effect on rehospitalization (Frick et al., 2013).

Cannabinoid use was more frequently associated with RD ‘high utilizers’ of inpatient facilities, whereas alcohol abuse represented a clinical risk factor for the readmissions of ‘extremely high utilizers’ (di Lorenzo et al., 2016).

Episodes of alcohol abuse during the week prior to admission (with no other symptom pattern association observed during the same period) were associated with the RD phenomenon in the study conducted by Morlino et al. (2011), suggesting that alcohol abuse does not directly lead to higher admission rates, but may rather cause a ‘fracture’ in a patients’ environment, thereby resulting in hospital admission. However, this study didn’t find a statistically significant association between the RD phenomenon and substance abuse, whether as the patients’ primary diagnosis or as their symptom pattern during the week prior to admission.

In three of the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between the RD patients and non-RD patients regarding alcohol and/or substance use ( di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Koparal et al., 2021; Neto & da Silva, 2008) or the diagnosis of addictive disorder (Woogh et al., 1977).

Other clinical factors

Regarding the age of disease onset, two studies showed that psychiatric illness manifests earlier in RD patients, more likely in their twenties (Koparal et al., 2021; Morlino et al., 2011), and one study considered a history of childhood psychiatric problems as one of the strongest predictors of rehospitalization (Bobo et al., 2004). Conversely, the characteristic ‘first psychiatric hospitalization before age of 21’, did not reach statistical significance in the work by Frick et al. (2013). Age of onset was not analysed by any other study presented in this review.

In order to assess the severity of symptoms, one study compared patients’ mean scores in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) but found no significant difference between RD and non-RD groups (Morlino et al., 2011).

Regarding patients’ level of functioning, significantly lower Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale scores were associated with RD patients in one study (Morlino et al., 2011), and higher mean scores in the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale displayed a protective effect for rehospitalization in another study (Frick et al., 2013). However, another study found the GAF score not statistically significant (Schmutte et al., 2009). Lack of self-care in the week prior to hospitalizations was associated with the RD phenomenon (Morlino et al., 2011).

According to di Lorenzo et al., aggressiveness during hospitalization represented a risk factor for frequent rehospitalizations. Violence and/or suicidality was one the conditions most frequently associated with readmissions as well as ‘aggressiveness during hospitalization’, both mild and severe, with a need for physical restraint and/or police force intervention (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). In other studies, the RD patients had significantly higher rates of forensic events (as for judicial prosecution for committing a crime) (Koparal et al., 2021) and involvement with the legal system (Bobo et al., 2004), and were more likely to have been previously admitted to a forensic mental hospital (Morlino et al., 2011). However, one other study pointed out that lifetime physically violent behaviour was lower in the RD patient group (di Lorenzo et al., 2016) and another one found differences in criminal record not statistically significant (Haywood et al., 1995).

As for suicidality, two studies found its association with the RD phenomenon (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Koparal et al., 2021), with a history of suicide attempts having prognostic value in predicting frequent hospitalizations (Koparal et al., 2021).

Organic comorbidity was related to the RD phenomenon as an apparent protective factor in one study (di Lorenzo et al., 2016) and not statistically significant in another (Koparal et al., 2021).

Having a family history of mental illness was not significantly associated with the RD phenomenon (Koparal et al., 2021; Schmutte et al., 2009).

Treatment related factors

Only two studies examined treatment related variables. In the analysis by Koparal et al., RD patients had higher rates of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) history, multiple drug treatment regimens and history of clozapine use, and these factors had prognostic value in predicting frequent hospitalizations. Also, in patients with combined antipsychotic use, the prevalence of atypical antipsychotic use was significantly higher in the RDP group (Koparal et al., 2021). According to another study, long-acting therapy with or without oral drugs were associated with extremely high use of the psychiatric service, indicating that these patients presented low therapeutic compliance (di Lorenzo et al., 2016).

Noncompliance, whether to medication regimens (Haywood et al., 1995) or to follow-up after discharge (Koparal et al., 2021) are associated with the RD phenomenon and seem to have prognostic value in predicting frequent hospitalizations, according to these two authors.

Factors related with healthcare service use

Place of outpatient care was examined in four studies. According to Kastrup, the RD population were relatively more often treated in an outpatient clinic, admitted from or discharged to their own home; and less likely to be transferred from or to a somatic ward or another kind of institution (Kastrup, 1987a, 1987b). Referral to the hospital’s outpatient clinic composed a risk factor for multiple hospitalizations, as opposed to referral to a general practitioner, in another study (Frick et al., 2013). Patients treated both in a mental health service and in a substance use service or rehabilitative program showed a higher risk for RD pattern, with extremely short time to recurrent admissions (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). This study also showed that extremely high users of the psychiatric services were more likely transferred to another psychiatric ward or had no post-discharge destination due to ‘self-discharge’ (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). In another study, the RD phenomenon was associated with having follow-up in centres other than the University outpatient clinic (Koparal et al., 2021).

According to Morlino et al. (2011), RD patients had more frequently been under treatment for psychiatric problems in the month prior to admission.

Three studies found an association between involuntary (compulsory) admission and less frequent hospitalizations (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Frick et al., 2013) serving as a protective factor against the RD phenomenon (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). In another study, emergency services were more frequently involved in the admission of RD patients (Morlino et al., 2011). Conversely, type of admission was not statistically significant in two other studies ((Bobo et al., 2004; Koparal et al., 2021).

RD phenomenon was associated with being discharged against medical advice in two of these studies (di Lorenzo et al., 2016).

Longer admissions compose a protective factor against the RD phenomenon (Frick et al., 2013), and RD patients tend to have shorter lengths of admission (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). One other study found the exact opposite (di Lorenzo et al., 2016) and for Koparal et al. (2021) this was not statistically significant.

According to two authors, the RD phenomenon was associated with a longer duration of patients’ first hospitalization (Bobo et al., 2004; Gastal et al., 2000), while two other found this variable not statistically significant (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Frick et al., 2013).

The Revolving Door phenomenon was associated with a shorter length of time between patients’ first and second hospitalization (di Lorenzo et al., 2016; Gastal et al., 2000), or at least between their initial hospitalizations, existing a positive association between number of admissions and accelerated rehospitalization (Frick et al., 2013).

Discussion

The concept of a revolving door implies an ongoing turnover of the same patients – that is, those who previously would have been hospitalized for a long time (B. A. Martin et al., 1976). It is relevant to highlight some historical issues regarding the treatment of psychiatric patients.

For example, in the 1930s, someone diagnosed with schizophrenia had a one-in-three chance of being discharged within 2 years after admission and, thereafter, very little chance of being discharged at all except by death (Wing, 1981). During the next decades, it became evident that a closer collaboration between psychiatry and somatic medicine was desirable, and from the mid-1950s, with the introduction of new antipsychotics and antidepressants, many patients started having a shorter stay during admission, through a combination of psychological, occupational and drug interventions (Bolwig, 2012).

Proponents of outpatient care in local communities argued that state asylums were inherently dehumanizing and anti-therapeutic, and that the community setting offered an opportunity for socialization and rehabilitation (Williams et al., 1980). Treatment in the community is also the preference for the vast majority of patients (Mechanic, 1987). The aim of maintaining subjects in their local environment is to assure better rehabilitation and reintegration in society (Munk-Jørgensen, 2000).

By the 1960s, the introduction of widespread community mental health services reduced the number of occupied hospital beds by about 50% in a 10-year period (Klerman, 1977). This decrease of hospital beds may have compromised the quality and length of acute inpatient care because of high bed occupancy rates (Jeppesen et al., 2016).

Effective community care for the most seriously disabled patients involves performance of many of the same functions as the mental hospital, ranging from assuring appropriate shelter to managing serious medical and psychiatric problems, as it also requires influence over areas of responsibility involving different sectors (housing, medical care, social services, welfare) (Mechanic, 1987).

By the 1980s, the proclaimed benefits of community living had not materialized for most discharged patients; many were still disabled, on welfare, and remain isolated in urban, sometimes rural, ghettos without connections to adequate treatment and rehabilitative services (Williams et al., 1980). Some of the most stressing problems associated with the community care of seriously mentally ill patients have been pointed out, namely: homelessness and problems of residence, service provisions, lack of financial support for services, rehabilitation efforts and employment, case management difficulties and the burden on the families (Aviram, 1990).

In fact, homelessness and problems of residence remain a challenge for many patients with severe mental illness, and community mental health services are still far away from providing adequate treatment to these super difficult patients (Gama Marques, 2021). People living homeless bear a great burden of psychiatric disorders have higher mental health needs and worse determinants of general health (Monteiro Fernandes et al., 2021). In the light of the management of difficult and super difficult patients that take part of our daily clinical practice – that is, patients who are, in theory, at the end-of-the-line of psychiatry care, with whom clinical contact is harder to establish, and, for example, present poor adherence or even resistance to treatment (Carnot & Gama Marques, 2018), many patients who exhibit a revolving door pattern of multiple hospitalizations are people living homeless. Just to mention an example of one patient who was living as a homeless person in Lisbon for three decades and presented an extensive clinical record of 85 psychiatric admissions over the last 25 years, and whose full recovery was never achieved because of an insufficient gain in insight and poor treatment adherence to all proposed clinical treatments and social support. Indeed, we hope that some of our most overwhelming recent case reports (Gama Marques, 2019, 2022; Gama Marques & Bento, 2020b) may pave the way for more and better studies in our city regarding psychiatric patients, living homeless, in revolving door (Bravo et al., 2022). These difficult patients, super difficult patients, sometimes anonymous (John Doe syndrome) (Gama Marques & Bento, 2020b) but many times unwanted, in what is starting to shape as a new subspecialty in the field of psychiatry: marontology (Gama Marques & Bento, 2020a).

The scarcity of mental health outpatient resources might also be a crucial factor for recurrent hospitalization in psychiatric patients. The number of resources required must be identified in order for the RD subject to become something the health-care system not only recognizes but acts upon (Barron, 2016).

However, few studies have explored society’s preparation and examined the needs of patients with long-term mental disorders. Instead, considerable research has focused on readmission issues in terms of its rate, risk and preventive factors (Ko & Park, 2021).

So, the way many authors have analysed the risk of the RD phenomenon over the last decades has been criticised for situating the problem of repeated transitions between hospital and community care within the individual rather than within the systems around the individual (Tyler et al., 2019). But analysing the efficiency of community care by looking at these complex systems that integrate multiple cultural, social and economic aspects is a much more challenging approach than to analyse contributing factors on an individual level.

This review aimed to analyse the existing literature regarding patients’ factors associated with the RD phenomenon, providing more insight on aspects that may contribute to multiple psychiatric admissions and help predict rehospitalization.

Readmissions have been taken as a sign of failure of outpatient care both to the patients and to the medical staff, and comparisons of readmission rates of different institutions are often taken as one of the criteria of their relative successful treatment (Marks, 1977)

Even though the term ‘Revolving Door’ has been generally used to define patients with chronic psychiatric disorders that require multiple hospitalizations, many authors have used different RD criteria. These inconsistencies pose practical problems for the development of policies that require a specific, constant and operational definition, allowing the identification of patients at risk and their needs and planning effective programs for them (Bachrach, 1988).

Concerning sociodemographic data, the factors with more evidence indicating their association with the RD phenomenon were patient’s age, marital status, educational level and employment status. Patients who are younger, especially between 15 and 35 years of age, single, with low educational level or unemployed are more likely to have a RD pattern of hospitalizations. These factors suggest a lower social integration of these patients, as they are less likely to be in a significant relationship, achieve a higher education level and are more likely unemployed. Even though psychiatric disorders may contribute to lower social integration, it is also true that lack of social integration may contribute to relapse (Neto & da Silva, 2008). Other authors had previously outlined that sufficient social adaptation capacities, attested by a higher GAF score, can be a protective factor for readmissions (Frick et al., 2013; Montgomery et al., 2002).

Thus, psychosocial interventions may have an important role in diminishing readmissions (Neto & da Silva, 2008) and there is strong evidence of its effectiveness in the treatment of psychiatric patients (Gühne et al., 2015; G. W. Martin & Rehm, 2012). Offering patients concurrent means of receiving care and help in finding employment at the same time, which is designated as Supported Employment, provides greater competitive employment and may also contribute to a higher level of quality of life (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2019). Most studies found there was no statistically significant association between patients’ gender, ethnicity or nationality, place of residence and social/economic status.

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders were the diagnoses most associated with the RD phenomenon in the studies included in this review. Overall, the readmission rates in people with schizophrenia are high considering the 3-month and 1-year readmission rates of 33.3% and 15.2%, respectively, as well as the 10-year readmission rate of 70.5% (Ko & Park, 2021). According to the literature, factors associated with multiple hospitalizations in schizophrenia patients are male gender, unmarried status, early age of onset, shorter length of hospitalizations, hebephrenic clinical subtype, higher severity of symptoms and lifetime substance use (Botha et al., 2010; Eaton et al., 1992; Hung et al., 2017; Mortensen & Eaton, 1994; Oiesvold et al., 2000).

The majority of the studies in this review identified alcohol and/or substance use, whether as a current diagnosis or in patients’ history, as an important risk factor associated with the RD phenomenon. Alcohol and/or substance problems may require short stays to clear a patient’s intoxications state (Haywood et al., 1995), to avoid the development of serious withdrawal symptoms, or to help patients unable to stop an episode of hard drinking (Kastrup, 1987a). These subjects are likely to get discharged as soon as the acute episode is over but are also likely to get readmitted the next time they are faced with the same problem (Kastrup, 1987b).

Schizophrenia is a well-known risk factor for hospital readmissions in patients with substance use (di Giovanni et al., 2020) and vice-versa (Botha et al., 2010; Olfson et al., 1999).

Several studies have shown that substance use negatively affect adherence to prescribed medications in patients with mental disorders (Okpataku et al., 2015). This might be a contributing factor to multiple hospitalizations. Creative strategies for engaging patients with substance use disorder in treatment and establishing a therapeutic alliance, such as motivational interviewing and assertive community treatment have demonstrated success (Herbeck et al, 2005).

Younger age of onset or age at first admission and suicidality were associated with the RD phenomenon in two out of three studies that analysed these factors. We believe more evidence will be needed to draw a conclusion.

Noncompliance to medication or to follow-up was associated with the RD phenomenon and seems to have prognostic value in predicting frequent hospitalizations. Treatment compliance problems are associated with lower GAF scores, which translate severe clinical and functional impairments, as these patients may have more difficulties complying with treatment (Herbeck et al, 2005).

There appears to be an association between involuntary type of admission and a smaller number of hospitalizations; and RD patients are more likely to be discharged against medical advice. These patients seem to have greater self-management of the hospitalization process, and voluntary hospitalization and self-discharge could represent a form of relief from difficult life situations or an answer to maladjustment (di Lorenzo et al., 2016). Compulsory treatment can be effective in improving the condition of severe and noncompliant patients (di Lorenzo et al., 2016), or could, otherwise, be regarded as coercive and favour the distancing of patients from the institution (Frick et al., 2013). According to one author, the repeated use of inpatient care, which can serve for some patients as a shelter from adverse life conditions, could lead to a sort of dependence on the service itself and create a vicious cycle of repetitive admissions, potentially inducing severe behavioural regression in patients (di Lorenzo et al., 2016).

We found inconsistent results regarding violent and/or criminal behaviour, organic comorbidity, and place of outpatient care and length of admission.

Some limitations of this review can be acknowledged. The terms used for the article search could have left behind articles that could have met the eligibility criteria but were not identified because of the absence of the term ‘revolving’. This was the case of the four studies that were later added in this review. Some of the studies admitted that cohort was not representative of the psychiatric patient population by certain characteristics. Various definitions of the RD phenomenon were used, with different criteria for the RD patient group applied in each study. This composes an important limitation, although we tried to reduce it by calculating the mean number of admissions/year. Differences in the methods used for data analysis also make it more difficult to draw conclusions. The diagnostic criteria also changed throughout the studies, as different manuals for classification of mental disorders were used.

Conclusion

The Revolving Door phenomenon has become an emerging problem with the shift of paradigm in the treatment of chronic psychiatric patients. Many studies tried to analyse the association of the RD phenomenon with patients’ characteristics, and determine which factors predict rehospitalization. This analysis, despite situating the problem within the individual rather than on the system that surrounds him, is a possible way of understanding better this phenomenon.

Based on this review, there is an association between the RD phenomenon and patients’ age, marital status, educational level, employment status, diagnosis, alcohol and/or substance use, age of disease onset, suicidality, noncompliance and type of admission.

Patients who are younger, single, with low educational level or unemployed are more likely to have a RD pattern. Psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia, and alcohol and/or substance use is also associated with this phenomenon, suicidal behaviour, noncompliance to treatment or voluntary type of admission.

The identification of patients at risk for multiple hospitalizations will allow the development of preventive intervention strategies that can significantly diminish the risk of homelessness and improve patients’ quality of care, safety and well-being.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Joana Fonseca Barbosa  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5007-2561

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5007-2561

João Gama Marques  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0662-5178

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0662-5178

References

- Aviram U. (1990). Community care of the seriously mentally Ill: Continuing problems and current issues. Community Mental Health Journal, 26(1), 69–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach L. L. (1988). Defining chronic mental illness: A concept paper. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 39(4), 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron G. R. S. (2016). The Alberta Mental Health Act 2010 and revolving door syndrome: Control, care, and identity in making up people. Canadian Review of Sociology, 53(3), 290–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo W. V., Hoge C. W., Messina M. A., Pavlovcic F., Levandowski D., Grieger T. (2004). Characteristics of repeat users of an inpatient psychiatry service at a large military tertiary care hospital. Military Medicine, 169(8), 648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwig T. G. (2012). Historical aspects of Danish psychiatry. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry,66(Suppl. 1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha U. A., Koen L., Joska J. A., Parker J. S., Horn N., Hering L. M., Oosthuizen P. P. (2010). The revolving door phenomenon in psychiatry: Comparing low-frequency and high-frequency users of psychiatric inpatient services in a developing country. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo J., Buta F. L., Talina M., Silva-Dos-Santos A. (2022). Avoiding revolving door and homelessness: The need to improve care transition interventions in psychiatry and mental health. Front Psychiatry, 13, 1021926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnot M. J., Gama Marques J. (2018). ‘Difficult patients’: A perspective from the tertiary mental health services. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 31(7–8), 370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Giovanni P., di Martino G., Zecca I. A. L., Porfilio I., Romano F., Staniscia T. (2020). The revolving door phenomenon: Psychiatric hospitalization and risk of readmission among drug-addicted patients. Clinica Terapeutica, 171(5), e421–e424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Lorenzo R., Sagona M., Landi G., Martire L., Piemonte C., del Giovane C. (2016). The revolving door phenomenon in an Italian acute psychiatric ward. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(9), 686–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W. W., Mortensen B., Hen-Man H., Freeman H., Bilker W., Burgess P., Wooff K. (1992). Long-term course of hospitalization for schizophrenia: Part I. Risk for rehospitalization. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 18(2), 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick D. E., VanderWeele T. J. (2019). Supported employment: Meta-analysis and review of randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support. PLoS ONE, 14(2, e0212208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick U., Frick H., Langguth B., Landgrebe M., Hübner-Liebermann B., Hajak G. (2013). The revolving door phenomenon revisited: Time to readmission in 17’415 patients with 37’697 hospitalisations at a German psychiatric hospital. PLoS ONE,8(10), e75612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Marques J. (2019). Pharmacogenetic testing for the guidance of psychiatric treatment of a schizoaffective patient with haltlose personality disorder. CNS Spectrums, 24(2), 227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Marques J. (2021). Super difficult patients with mental illness: Homelessness, marontology and John Doe Syndrome. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 34(4), 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Marques J. (2022). Pellagra with casal necklace causing secondary schizophrenia with capgras syndrome in a homeless man. The Primary Care Companion For CNS Disorders. 24(2), 40040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Marques J., Bento A. (2020. a). Homeless, nameless and helpless: John Doe syndrome in treatment resistant schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 224, 183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama Marques J., Bento A. (2020. b). Marontology: Comorbidities of homeless people living with schizophrenia. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 33(4), 292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastal F. L., Andreoli S. B., Quintana M. I. S., Gameiro M. A., Leite S. O., McGrath J. (2000). Predicting the revolving door phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, affective disorders and non-organic psychoses. Revista de Saúde Pública, 34(3), 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühne U., Weinmann S., Arnold K., Becker T., Riedel-Heller S. G. (2015). S3 guideline on psychosocial therapies in severe mental illness: Evidence and recommendations. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 265(3), 173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood T. W., Kravitz H. M., Grossman L. S., Cavanaugh J. L., Davis J. M., Lewis D. A. (1995). Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(6), 856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck D. M., Fitek D. J., Svikis D. S., Montoya I. D., Marcus S. C., West J. C. (2005). Treatment compliance in patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal on Addictions, 14(3), 195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung Y. Y., Chan H. Y., Pan Y. J. (2017). Risk factors for readmission in schizophrenia patients following involuntary admission. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0186768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen R. M., Christensen T., Vestergaard C. H. (2016). Changes in the utilization of psychiatric hospital facilities in Denmark by patients diagnosed with schizophrenia from 1970 through 2012: The advent of “revolving door” patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 133(5), 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup M. (1987. a). The use of a psychiatric register in predicting the outcome “revolving door patient” A nation-wide cohort of first time admitted psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 76, 552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup M. (1987. b). Who became revolving door patients? Findings from a nation-wide cohort of first time admitted psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 76, 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman G. L. (1977). Better but not well: Social and ethical issues in the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 3(4), 617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y., Park S. (2021). Life after hospital discharge for people with long-term mental disorders in South Korea: Focusing on the “revolving door phenomenon.” Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koparal B., Ünler M., Utku H. Ç., Candansayar S. (2021). Revolving door phenomenon and related factors in schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and other psychotic disorders. Psychiatrica Danubina, 33(1), 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg P., Levinson D., Sharshevsky Y., Feldman D., Lachman M. (2008). Clinical case management of revolving door patients – A semi-randomized study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(6), 449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks F. M. (1977). The characteristics of psychiatric patients readmitted within a month of discharge. Psychological Medicine, 7, 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh A., Glick M., Zigler E. (1981). Premorbid social competence and the revolving door phenomenon in psychiatric hospitalization. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 169(5), 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. A., Kedward H. B., Eastwood M. R. (1976). Hospitalization for mental illness: Evaluation of admission trends from 1941 to 1971. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 115, 322–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. W., Rehm J. (2012). The effectiveness of psychosocial modalities in the treatment of alcohol problems in adults: A review of the evidence. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(6), 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. (1987). Correcting misconceptions in mental health policy: Strategies for improved care of the seriously mentally ill. The Milbank Quarterly, 65(2), 203–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro Fernandes A., Gama Marques J., Bento A., Telles-Correia D. (2021). Mental illness among 500 people living homeless and referred for psychiatric evaluation in Lisbon, Portugal. CNS Spectrums. Advance online publication. 10.1017/S1092852921000547 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Montgomery P., Kirkpatrick H. (2002). Understanding those who seek frequent psychiatric hospitalizations. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 16(1), 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlino M., Calento A., Schiavone V., Santone G., Picardi A., de Girolamo G. (2011). Use of psychiatric inpatient services by heavy users: Findings from a national survey in Italy. European Psychiatry,26, 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen P. B., Eaton W. W. (1994). Predictors for readmission risk in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 24, 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Jørgensen P. (2000). From psychiatric hospital to rehabilitation: The Nordic experience. Encephale, 26(1), 3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto D. D., da Silva A. C. (2008). Characterization of readmissions at a Portuguese psychiatric hospital: An analysis over a 21 month period. The European Journal of psychiatry, 22(2), 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Oiesvold T., Saarento O., Sytema S., Vinding H., Göstas G., Lönnerberg O., Muus S., Sandlund M., Hansson L. (2000). Predictors for readmission risk of new patients: the Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101, 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okpataku C. I., Kwanashie H. O., Ejiofor J. I., Olisah V. O. (2015). Medication compliance behavior in psychiatric out-patients with psychoactive substance use comorbidity in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(3), 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M., Mechanic D., Boyer C. A., Hansell S., Walkup J., Weiden P. J. (1999). Assessing clinical predictions of early rehospitalization in schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(12), 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyffe I., Kurs R., Gelkopf M., Melamed Y., Bleich A. (2009). Revolving-door patients in a public psychiatric hospital in Israel: Cross sectional study. Croatian Medical Journal, 50(6), 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutte T., Dunn C., Sledge W. (2009). Characteristics of inpatients with a history of recurrent psychiatric hospitalizations: A matched-control study. Psychiatric Services, 60(12), 1683–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler N., Wright N., Waring J. (2019). Interventions to improve discharge from acute adult mental health inpatient care to the community: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. H., Bellis E. C., Wellington S. W. (1980). Deinstitutionalization and social policy: Historical perspectives and present dilemmas. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 50(1), 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing J. (1981). From institutional to community care. Psychiatric Quarterly, 53(2), 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woogh C. M., Meier H. M. R., Eastwood M. R. (1977). Psychiatric hospitalization in Ontario: the revolving door in perspective. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 116(8), 876–881. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]