Abstract

Introduction

Several low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) are preparing to introduce long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis (LAP). Amid multiple pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) options and constrained funding, decision‐makers could benefit from systematic implementation planning and aligned costs. We reviewed national costed implementation plans (CIPs) to describe relevant implementation inputs and activities (domains) for informing the costed rollout of LAP. We assessed how primary costing evidence aligned with those domains.

Methods

We conducted a rapid review of CIPs for oral PrEP and family planning (FP) to develop a consensus of implementation domains, and a scoping review across nine electronic databases for publications on PrEP costing in LMICs between January 2010 and June 2022. We extracted cost data and assessed alignment with the implementation domains and the Global Health Costing Consortium principles.

Results

We identified 15 implementation domains from four national PrEP plans and FP‐CIP template; only six were in all sources. We included 66 full‐text manuscripts, 10 reported LAP, 13 (20%) were primary cost studies‐representing seven countries, and none of the 13 included LAP. The 13 primary cost studies included PrEP commodities (n = 12), human resources (n = 11), indirect costs (n = 11), other commodities (n = 10), demand creation (n = 9) and counselling (n = 9). Few studies costed integration into non‐HIV services (n = 5), above site costs (n = 3), supply chains and logistics (n = 3) or policy and planning (n = 2), and none included the costs of target setting, health information system adaptations or implementation research. Cost units and outcomes were variable (e.g. average per person‐year).

Discussion

LAP planning will require updating HIV prevention policies, technical assistance for logistical and clinical support, expanding beyond HIV platforms, setting PrEP achievement targets overall and disaggregated by method, extensive supply chain and logistics planning and support, as well as updating health information systems to monitor multiple PrEP methods with different visit schedules. The 15 implementation domains were variable in reviewed studies. PrEP primary cost and budget data are necessary for new product introduction and should match implementation plans with financing.

Conclusions

As PrEP services expand to include LAP, decision‐makers need a framework, tools and a process to support countries in planning the systematic rollout and costing for LAP.

Keywords: economics, healthcare costs, implementation planning, LMICs, long‐acting HIV prevention, pre‐exposure prophylaxis

1. INTRODUCTION

Of the nearly 1.5 million annual new HIV acquisitions globally, most occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), and 70% of acquisitions occur in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) [1, 2, 3]. In 2020, most of the 14 countries that achieved UNAIDS “Fast‐Track” targets of 73% across the testing and treatment cascade were LMICs, and seven were in eastern and southern Africa (ESA) [4] In countries achieving UNAIDS Fast‐Track targets, new HIV acquisitions have declined from 39% in Uganda to 70% in Zimbabwe, but no country has achieved the projected elimination target [1, 2]. Fast‐track goals for comprehensive HIV prevention, including 3 million person‐years of pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) by 2020, were not achieved [5]. Additionally, more than two in five oral PrEP users globally discontinue within 6 months of initiation with higher rates in LMICs and women [6]. PrEP discontinuation rates may represent individual‐level changes in potential HIV exposure or it may signal a preference for products other than daily oral PrEP [7].

In July 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) added conditional recommendations for two long‐acting HIV prevention interventions: the monthly dapivirine vaginal ring (PrEP ring) and long‐acting cabotegravir (CAB LA; injectable PrEP), joining oral PrEP as part of combination HIV prevention [8, 9]. The 2022 WHO Guidelines mark an unprecedented moment in HIV prevention, when multiple PrEP methods are recommended as part of biomedical prevention for all at elevated risk of HIV (Appendix S1) [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. Notably, for the first time, cis‐gender women can utilize three HIV PrEP methods: daily oral PrEP, PrEP ring, and injectable PrEP [10, 11, 15]. By October 2022, the monthly PrEP ring had been approved in six countries in ESA and is currently undergoing regulatory review in six additional ESA countries [19]. Long‐acting cabotegravir received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration in December 2021 [20] and August 2022, respectively. In October 2022, Zimbabwe became the first LMIC to approve injectable PrEP for use [21, 22]. Injectable PrEP has also been approved by South African Health Products and Regulatory Authority (SAPHRA) and is currently undergoing regulatory review in several LMICs [19, 21].

Evidence review of “Fast‐Track” goals highlighted global challenges in implementation and widening funding gaps that reduced the impact of HIV prevention amid biomedical advancements [4]. The UNAIDS strategy 2021–2026 highlights the need to systematize HIV prevention implementation and address the widening funding gap for the HIV response, particularly financing for HIV prevention [3]. In an earlier review of daily oral PrEP costs and cost‐effectiveness modelling studies, Case et al. highlighted the poor quality of PrEP cost‐effectiveness and modelling studies and the lack of primary cost data collection, “real world costs,” or inclusion of service delivery strategies in modelling studies [23, 24]. The introduction long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis (LAP) marks an opportunity for choice in HIV prevention, accompanied by increased complexity in health service delivery. This opportunity should be met with plans to guide and assess implementation systematically. Further, improved cost analyses are critical to inform such plans [1, 3]. Without these, the recognized deficiencies threaten to deepen and jeopardize LAP's potential. With this scoping review, we sought to inform costed plans for LAP implementation by: (1) collating and synthesizing evidence from costed national plans of oral PrEP and family planning (FP) implementation; (2) developing a consensus on the range of key activities and inputs needed for systematic delivery of PrEP innovations, including LAP (hereafter referred to as implementation domains); (3) appraise the cost evidence that would typically inform national implementation plans using this implementation framework; and (4) provide recommendations on future considerations for improving systematic LAP delivery.

2. METHODS

2.1. Defining implementation domains

We reviewed publicly available national costed PrEP implementation plans to identify implementation domains that will help achieve national PrEP scale‐up or impact goals and objectives. Broad searches were conducted through Google, and focused searches were conducted through websites of national ministries of health, multilateral agencies and digital repositories, like PrEPwatch.com. Implementation details were extracted and mapped to describe the real‐world consensus of implementation domains. We also mapped domains from templates of FP costed implementation plans (CIPs) [25, 26, 27, 28].

2.2. Search strategy

We conducted a scoping review of PrEP costing and cost‐effectiveness studies adhering to the Cochrane Handbook 5.1 and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA) scoping review guidance [29] (Supporting Information S2). Between 1–30 June 2022, we searched nine databases for peer‐reviewed literature: PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, Embase, PsychInfo, Africa Wide Information, Global Index Medicus, Cochrane and Econlit—using terms regarding (1) PrEP methods, (2) costing and (3) LMICs to identify potential publications (Supporting Information S3). Lastly, we solicited the International AIDS Economics Network for unpublished reports and non‐peer‐reviewed literature.

2.3. Inclusion criteria

We included all studies reporting PrEP interventions currently or imminently available (e.g. daily oral, event‐driven PrEP, PrEP ring, and CAB LA), or likely to make a market debut within the next 10 years (see Supporting Information S3 for full list) [30]. Additional inclusion criteria were that the study: (1) measured cost or estimated cost through primary data collection or other methods, including epidemiologic and mathematical modelling; (2) was published between 1 January 2010 and 30 June 2022; (3) reported cost data (e.g. average or incremental) or economic evaluation outcomes, such as cost‐effectiveness, cost‐benefit, or cost‐utility; (4) was conducted in any LMIC (classified using World Bank categorizations [31]); and (5) was published in English. We compared our final study sample with other recent reviews on the modelling and cost‐effectiveness of biomedical HIV prevention by Bozzani et al. and Giddings et al. [32, 33]. We chose 2010 because clinical trials for daily oral PrEP were underway, and many countries were already considering ways to incorporate PrEP into national HIV plans, pending proven safety and efficacy. We excluded publications reporting only qualitative data; assessing treatment as prevention, microbicides, vaccines, or broadly neutralizing antibodies only; examining high‐income country settings only; missing full texts; and conveying aggregate (other reviews), subjective (letters to the editor, commentaries), formative (study protocols), or theoretical (not reporting cost or cost‐effectiveness) research information.

2.4. Data screening and extraction

Two reviewers (EG and NT) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility using Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia), followed by a review of full‐text articles. Three investigators (DC, SF and CJH) independently reviewed and resolved discrepant screenings and reviewed a sub‐sample of concordant studies to validate the agreement. When needed, the broader team discussed and resolved discrepancies. Co‐authors (DC, SF, CJH, NT, JW and KK) extracted relevant data from the included studies into REDCap [34]. Co‐authors (FB, FTP and STR) conducted an independent review to supplement this review's findings [32, 35].

The data collection instrument included: implementation domains previously identified, author, country, year of publication, study year, study purpose, study design, population(s), intervention(s), perspective, duration of observation, period type, sampling strategies, data collection, scope, cost type, estimation method of inputs, discount and inflation rates, analytic methods and findings, transparency regarding limitations, conflicts of interest, and data availability. Data abstraction was disaggregated by geographic area, priority population, PrEP method, and service delivery platform for each cost or economic result. For articles published before 2015, we classified reports of PrEP as daily oral PrEP if the authors did not explicitly state the type of PrEP method.

2.5. Assessment of financial and economic evidence

We utilized principles 1–17 from the Global Health Costing Consortium (GHCC) reference case, which presents principles of quality and completeness of costing studies of health interventions with qualitative and quantitative information [25, 26, 27, 28, 36].

2.6. Data analysis and synthesis

We assessed inter‐rater reliability using Cohen's Kappa (K), a statistic that accounts for agreement due to random chance, at each screening stage [37, 38]. We created a PRISMA diagram to present the number of included and excluded publications [39]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the study characteristics from quantitative variables (i.e. frequencies and percentages for categorical variables; maximums, medians and modes for continuous variables). We synthesized extracted texts on costs and assumptions. Given the diversity of study designs included in the review, we did not conduct assessments of quality or bias.

3. RESULTS

3.1. National costed PrEP implementation plans

Our search for available costed national PrEP operational plans from LMICs yielded four country plans from ESA: Kenya, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe [25, 26, 27, 28]. No publicly available plans included LAP.

3.2. Identified implementation domains

Also, we examined the GHCC and the template for developing CIPs for FP, as well as some resulting national CIPs, as source files for identifying implementation domains [36, 40, 41]. Reviewing these reports, we identified the following 15 key inputs and activities (implementation domains) in at least one document (Table 1) that represent our study team's consensus:

National coordination, policy and planning—Leadership, governance, and activities to increase ownership and coordination of the HIV PrEP response. Additional activities include implementation planning, adaptation and dissemination of guidelines and policies, community and stakeholders’ engagement, and coordination to start up, scale, or sustain PrEP programme.

Target setting—Activities to define priority populations, coverage levels, the pace of introduction and scale‐up, and other rollout scenarios to achieve impact.

Communication/awareness raising/demand creation—Activities to increase knowledge and awareness of PrEP services, create demand for PrEP among priority populations and PrEP advocacy at all levels.

Service delivery approaches—Includes service entry points for integrating PrEP, and feasibility of integrating PrEP into other services. We particularly focused on non‐HIV services integration, such as FP, sexual and reproductive health, antenatal care, and community‐based services. We also identified inclusion into HIV programmes, including self‐testing.

Counselling and adherence support—Includes counselling to initiate, sustain, discontinue, and adhere to PrEP.

Human resources—Includes in‐service and pre‐service education and training for physicians and allied health professionals.

PrEP intervention (commodities)—Includes cost of PrEP products.

Laboratory monitoring services and other commodities—Includes baseline tests for eligibility and safety monitoring.

Supply chain management and logistics—Includes commodity inventory management, reporting, tracking, and handling procedures for distributing PrEP to service delivery points. This includes warehousing and distribution of PrEP and other necessary commodities.

Health information systems—Developing and updating information systems and registers to document and report PrEP services for quality improvement or reporting purposes.

Monitoring and evaluation—Activities to define indicators, include PrEP monitoring as part of routine HIV services, and continuous quality control and improvement to ensure that the services are of the highest possible standard.

Implementation science and operations research—Includes planned research activities to facilitate and inform scale‐up.

Budgeting, costing and financing—Budget, cost, and economic evaluations to develop cost estimates of PrEP service delivery, impact, and financing shortfalls. This includes stakeholder engagement to blend finances through public–private partnerships to support PrEP delivery.

Indirect/overhead—Includes costs that cannot be directly traced to the provision of a service, such as administration, security personnel, buildings, and general equipment.

Above‐site activities—Includes various support services provided by the central administration, such as training, education and outreach, demand generation campaigns, central laboratory services, technical assistance, and capacity building.

Table 1.

Mapping of key implementation domains drawn from costed national implementation plans for daily oral PrEP.

| Kenya: Framework for implementation of pre‐exposure prophylaxis in Kenya—2017 | South Africa: NDoH PrEP implementation pack | Zambia—Implementation framework and guidance for pre‐exposure prophylaxis of HIV infection 2018 | Zimbabwe—Implementation plan for HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis in Zimbabwe 2018–2020 | Family planning CIP template | GHCC principles | Consolidated implementation domains/content areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Planning, leadership and governance * Leadership and governance to increase ownership and coordination. Adaptation and dissemination of guidelines and policies, capacity building and community engagements. |

Clinical guideline development |

Leadership and governance Sub‐committee National taskforce |

National coordination and advocacy for an enabling policy environment | Policy and advocacy to secure resources for plan development stewardship and governance | Start‐up period versus implementation or both | National coordination, policy and planning |

|

Prioritizing and implementing PrEP services ‐ Populations with high HIV incidence/prevalence by geography, population groups and risk behaviours |

Target settings | Target population, coverage, time period | Target setting | |||

| Communications, advocacy and community engagement | Communication and community‐based strategies |

Build awareness/create demand Mobilize communities |

Awareness raising, PrEP promotion | Demand, communication and outreach | Communication/awareness raising/demand creation | |

|

Service delivery operations * ‐delivered using community‐based and facility‐based delivery models, ‐prevention centres, pharmacies, stand‐alone DICEs, special clinics MCH/FP/ANCs, youth‐friendly centres, comprehensive care centres, outpatient departments |

Quality of care Effectiveness and efficiency Integration across various entry points |

Programming PrEP services Service delivery minimum standards where PrEP demand can be generated Integrated in existing services to reach populations Facilities with relevant services, (HIV and STI testing, ART, YFS, MNCH, VMMC, OPD, family planning), facility readiness |

Public and private‐sector facility mapping Provision of PrEP |

Service delivery | Delivery mechanism | Service delivery approaches |

| Adherences support | Quality of care: counselling, stigma reduction and adherence | Counselling and adherence support | ||||

|

Human resources In‐service training/pre‐service education Trainer of trainers (TOT) |

Human resources |

Human resources ‐ integrated HIV care training |

Provider sensitization and training | Salary/labour cost | Human resources | |

| PrEP (TDF/FTC) * | PrEP (TDF/FTC) | PrEP (TDF/FTC) | Commodities | Intervention | PrEP intervention (commodities) | |

|

Laboratory (baseline tests and monitoring) forecasting and quantifying Monitoring for supply security Warehousing and distribution |

Laboratory services | Laboratory monitoring services | Laboratory monitoring services and other commodities | |||

|

Commodity management procedures * (ordering/handling and reporting) Commodity security Logistic management information systems (LMIS): forecasting and quantifying Monitoring for supply security Warehousing and distribution |

Functioning supply chain, including drugs and commodities | Procurement and supply chain | Maintain a consistent supply of PrEP medicines | Commodity security | Supply chain management and logistics | |

|

Monitoring and evaluation systems (documentation and reporting) |

Developing system triggers for people who cannot adhere | Supporting change | Health information systems | |||

|

Monitoring and evaluation * Quality improvement Facilitate and inform scale up Improving PrEP programme efficiency Continuous quality control and improvement (CQI) |

Monitoring and evaluation |

Monitoring and evaluation Integrate PrEP monitoring within existing reporting services Assess adherence, retention and linkages Consider risk‐based reasons for stopping |

Integrated monitoring and evaluation system for PrEP | Monitoring and coordination | Monitoring and evaluation | |

| Research and impact evaluation | Conduct research and evaluation | Research and supporting change | Implementation science and operations research | |||

| Financing and resource mobilization * |

Costing and financing the PrEP and T&T policy ‐ establish the cost of implementation of these plans at national and provincial levels |

Mobilize and track resources | Financing | Budgeting, costing and financing | ||

| Capital | Overhead costs | Indirect/overhead | ||||

| Above‐service delivery | Above‐site activities |

Note: Asterisks (*) indicate that the cost was estimated or budgeted within the National plan. Abbreviations: ANCs, Antenatal care; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CIP, costed implementation plans; DICEs, drop‐in centres; FP, family planning; GHCC, Global Health Cost Consortium; MCH, maternal and child health; MNCH, maternal neonatal and child health; NDoH, National Department of Health; OPD, outpatient departments; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infections; TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil and emtricitabine; VMMC, voluntary medical male circumcision; YFS, youth‐friendly services.

Six of the 15 implementation domains were in five (plans and template): national coordination, policy, and planning; awareness raising and demand creation; service delivery approaches; human resources; supply chain and logistics; and monitoring and evaluation (Table 1). The other domains were included in two or three plans.

3.3. Study characteristics

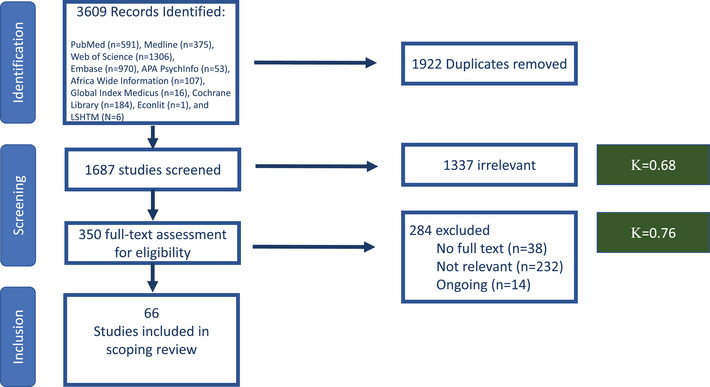

Searches of electronic databases for oral PrEP and LAP costing and cost‐effectiveness literature yielded 3609 publications; of which, 1922 were duplicates, 1687 underwent title‐abstract screening, 1337 were excluded and 350 underwent full‐text review. We excluded ongoing studies (n = 14) and studies lacking full‐text availability (n = 38) or relevancy (n = 232), such as only high‐income country settings, not reporting cost data, or reporting only qualitative findings. Ultimately, 66 studies were included (Figure 1). Reviewers exhibited moderate to good agreement during title‐abstract screening (K = 0.68) and better agreement in full‐text review (K = 0.75).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of identified, screened and included studies.

3.4. Populations

The 66 studies (Table 2) represented the following specific population groups: adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) (29%); men who have sex with men (MSM) (27%); sex workers (27%, majority female sex workers except for one reported male sex worker); general population (26%); women of any age (18%); men of any age (9%); and sero‐different couples (SDCs) (17%). The populations least represented (<7%) were adolescent boys and young men (ABYM), people who inject drugs, trans women, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and prisoners. Additional study details of each population group disaggregated cost and economic data are shown in S4A, and for all populations regardless of cost and economic data disaggregation in S4B.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (N=66).

| Author | Year of publication | Countries | Priority population represented | Priority population costed | Primary costing | PrEP methods | Long‐acting PrEP | Aims/objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ying | 2015 | Uganda | Sero‐different couples (SDC) | SDC | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the additional operational costs of PrEP delivery in an open‐label, prospective study and project long‐term health and economic outcomes and estimate cost‐effectiveness of PrEP implementation |

| Eakle | 2017 | South Africa | Sex worker | Sex worker | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Support integration of oral PrEP, as part of a combination prevention approach, and early antiretroviral therapy (ART) into existing HIV services in two urban settings, with specific aims to assess uptake, retention and adherence among female sex workers and to estimate the cost of this strategy |

| Suraratdecha | 2018 | Thailand | Men who have sex with men (MSM) | MSM | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Assess the cost of providing oral PrEP to MSM and estimate the epidemiological impact and cost‐effectiveness of oral PrEP for this target group |

| Wong | 2018 | China (Hong Kong) | MSM | MSM | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Examine the impact of PrEP in a setting with low HIV incidence with a low proportion of high‐risk MSM in Asia, through developed an epidemic model and conducted cost‐effectiveness analysis using empirical multicentre clinical and HIV sequence data from MSM living with HIV in Hong Kong, in conjunction with behavioural data of local MSM |

| Irungu | 2019 | Kenya | SDC | SDC | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the cost of delivering antiretroviral‐based HIV prevention to HIV SDC in public health facilities in Kenya and the incremental cost of providing PrEP as a component of this strategy |

| Roberts | 2019 | Kenya | Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) | AGYW | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the incremental cost of integrating PrEP delivery into routine MCH and FP services and explore the cost implications of service delivery modifications, such as timing of creatinine monitoring and prioritized delivery to women identified as having high risk for HIV acquisition |

| Hughes | 2020 | Zimbabwe | SDC | SDC | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the resources required to deliver various safer conception strategies and calculate the incremental cost per couple for “real world” scenarios for the delivery of the safer strategies in the public sector |

| Peebles | 2021 | Kenya | SDC | Other | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the incremental cost of public‐sector HIV‐1 care clinic‐based provision of PrEP in Kenya |

| Hendrickson | 2021 | Zambia | AGYW, general population, MSM, sex worker | AGYW, general population, other | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Present the results of a costing study of PrEP implementation in Zambia, aiming to provide cost estimates of PrEP provision disaggregated by programme type and showcase costs per PrEP‐month of effective use, using aggregate PrEP persistence data, and compare that to costs for perfect use |

| Wanga | 2021 | Kenya | AGYW | AGYW | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate the cost of delivering daily oral PrEP to AGYW in two family planning clinics in Kisumu and estimate the total annual cost and average cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed as implemented in the study setting and as would be incurred by the Kenyan Ministry of Health if it were to implement PrEP delivery to the same population in the same facilities |

| Mudimu | 2022 | South Africa | AGYW | AGYW | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate the cost of PrEP provision with effective use counselling offered to AGYW through community‐based HIV testing platforms |

| Mangenah | 2022 | Zimbabwe | AGYW, men, women | AGYW, men, women | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Provide input into cost‐effectiveness modelling and data for assessing resource needs associated with scaling up PrEP delivery |

| Okal | 2022 | Kenya | AGYW | AGYW | Yes | Daily oral PrEP | No | Compare unit costs of providing DREAMS interventions to AGYW across two sites, an urban (Nyalenda A Ward) and peri‐urban (Kolwa East Ward) setting, in Kisumu County, Kenya |

| Smith | 2016 | South Africa | Sex worker, ABYM, AGYW, men, women, adolescents | General population | No | bnAbs, PrEP ring, daily oral PrEP, injectable PrEP | Yes | Construct a strategic approach to HIV prevention using limited resources to achieve the greatest possible prevention impact through the use of interventions available today and in the coming years |

| Stover | 2016 | Asia and Pacific, East and Southern Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America, Middle East and North Africa, West and Central Africa, West and Central Europe and North America | AGYW, general population, MSM, people who inject drugs (PWID), prisoners, SDC, sex worker, trans women (TGW) | Other | No | Other PrEP (PrEP includes oral pills, vaginal gel, vaginal ring and injectable forms) | Yes | Describes the analysis that produced the 2020 and 2030 Fast‐Track targets and the estimated resources needed to achieve them in low‐ and middle‐income countries |

| Walensky | 2016 | South Africa | Women | Women | No | Daily oral PrEP, injectable PrEP | Yes | Anticipate the development of newer PrEP formulations, investigate the effectiveness thresholds that would justify the additional cost over existing PrEP alternatives in a population of high‐risk young women in South Africa, and identify the key drivers and uncertainties behind that assessment |

| Glaubius | 2016 | South Africa | General population | General population | No | Injectable PrEP | Yes | Analyse scenarios of RPV PrEP scale‐up for combination HIV prevention in comparison with a reference scenario without PrEP |

| Quaife | 2018 | South Africa | AGYW, sex worker, women | AGYW, sex worker, women | No | Daily oral PrEP, PrEP ring, other PrEP (includes multiple combinations of multi‐purpose oral, vaginal ring, injectable, gels and diaphragm technologies) | Yes | Examine the cost‐effectiveness of the incremental benefits and health system costs of single‐ and multi‐purpose prevention products, compared to current practice of condom use and male circumcision prevalence and model cost‐effectiveness across three female groups: younger women (aged 16–24), older women (aged 25–49) and female sex workers |

| van Vliet | 2019 | South Africa | Women | Women | No | Injectable PrEP | Yes | Model how many HIV infections could be averted if injectable contraceptive users started using long‐acting PrEP and determine the cost at which long‐acting PrEP drugs would be cost‐effective |

| Glaubius | 2019 | South Africa | Women | Women | No | PrEP ring | Yes | Evaluated the potential epidemiological impact and cost‐effectiveness of dapivirine vaginal ring PrEP among 22‐ to 45‐year‐old women in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa |

| Reidy | 2019 | Kenya, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe | AGYW, general population, sex worker | AGYW, general population, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP, PrEP ring | Yes | Explore the impact and cost‐effectiveness of the PrEP ring in different implementation scenarios alongside scale‐up of other HIV prevention interventions |

| Vogelzang | 2020 | South Africa | Adolescent boys and young men (ABYM), men | ABYM, men | No | Daily oral PrEP, injectable PrEP, other PrEP (oral PrEP + injectable PrEP) | Yes | Estimate the incremental cost‐effectiveness of providing oral PrEP, injectable PrEP or a combination of both to heterosexual South African men to assess whether providing PrEP would efficiently use resources |

| Adeoti | 2021 | Nigeria | General population | General population | No | Other PrEP (PrEP as a concept) | Yes | Evaluate the impact of PrEP/PEP using a novel artificial intelligence technology, assessing the impact on HIV burden (incidence) and service utilization in a Nigerian HIV treatment centre |

| Pretorius | 2010 | South Africa | AGYW | AGYW | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate PrEP alongside ART and condom‐use interventions by developing an age‐structured model, which is contextualized to the South African epidemic, paying attention to the distribution of relative infection risks between age categories |

| Hallett | 2011 | South Africa | SDC | SDC | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Examine impact and cost‐effectiveness of different TasP and oral PrEP strategies |

| Gomez | 2012 | Peru | MSM, sex worker, TGW | MSM, sex worker, TGW | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Investigate the impact of a feasible intervention, determine the most efficient strategies for rollout and examine the impact of coverage, adherence and prioritization on both health benefits and costs to the health system |

| Long | 2013 | South Africa | Men, women | Men, women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Assess the impact of simultaneously scaling up multiple biomedical HIV prevention programmes and calculate the benefits of reduced secondary transmission among partners of programme recipients |

| Cremin | 2013 | South Africa | ABYM, AGYW | Adolescents and young adults | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the potential impact and cost‐effectiveness of antiretroviral‐based HIV prevention strategies |

| Nichols | 2013 | Zambia | Other | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Explore the possibilities of daily oral PrEP optimization using realistic data collected in the rural HIV clinic at the Macha Mission Hospital in Zambia and evaluate the risk for resistance development |

| Verguet | 2013 | 42 Sub‐Saharan countries | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Study the potential impact and incremental cost‐effectiveness of providing PrEP over a 5‐year period (2013–2017) to a general adult population in sub‐Saharan Africa to provide insight into where and why a PrEP intervention could be best put to use for HIV prevention |

| Stover | 2014 | 25 Low‐ and middle‐income countries | Adolescents and young adults, general population, MSM, other, SDC, sex worker | Adolescents and young adults, general population, MSM, other, SDC, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP, HIV vaccine | No | Examine the impact of achieving high coverage of all existing HIV prevention interventions and three new approaches on the HIV epidemic in all low‐ and middle‐income countries |

| Nichols | 2014 | Zambia | Other | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Compare the cost‐effectiveness and economic affordability of antiretroviral‐based prevention strategies in rural Macha, Zambia |

| Anderson | 2014 | Kenya | Sex worker, MSM, men, women | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Examine how a fixed amount of resources for HIV prevention can be used to generate reductions in the rate of new HIV infections using two forms of resource allocation: (1) the rollout of particular interventions is uniform across the country; and (2) interventions can be focused on geographic or key affected populations that contribute to HIV strongholds |

| Alistar | 2014 | South Africa | General population | Other | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Study the population health outcomes and cost‐effectiveness of implementing expanded ART coverage and oral PrEP in a setting with a heavy HIV burden |

| Alistar | 2014 | Ukraine | PWID | PWID | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of PrEP for PWID alone or as part of a portfolio of interventions including methadone maintenance treatment for PWID and antiretroviral treatment for all individuals living with HIV and project the evolution of the epidemic under various combinations of strategies for HIV control: oral PrEP programmes for uninfected IDUs, MMT programmes for PWID and scale‐up of ART programmes for eligible people living with HIV (including PWID and non‐PWID) |

| Cremin | 2015 | Mozambique | Women | Women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the prevention impact and the cost‐effectiveness of providing time‐limited PrEP to partners of migrant miners in Gaza, Mozambique |

| Jewell | 2015 | South Africa | SDC | SDC | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the cost‐effectiveness of daily oral tenofovir‐based PrEP, with a protective effect against HSV‐2 as well as HIV‐1, among HIV‐1 SDC in South Africa |

| Cremin | 2015 | Kenya | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Investigate the influence of potential interactions between key aspects of a PrEP intervention on projections of epidemiological impact and cost‐effectiveness |

| Mitchell | 2015 | Nigeria | SDC | SDC | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the impact and cost‐effectiveness of PrEP, TasP and condom promotion for SDC in Nigeria |

| Price | 2016 | Sub‐Saharan Africa/Zambia | Pregnant and breastfeeding women | Pregnant and breastfeeding women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Develop a decision analytic model to evaluate a strategy of daily oral PrEP during pregnancy and breastfeeding in SSA |

| Moodley | 2016 | South Africa | Adolescents and young adults | Adolescents and young adults | No | Daily oral PrEP, HIV vaccine | No | Economically evaluate individual and combination HIV preventive strategies and compare their impact against both the current rollout of ART and a potential scaling‐up of the ART programme |

| Meyer‐Rath | 2017 | South Africa | AGYW, sex worker | AGYW, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Identify the optimal mix of HIV services under a constrained budget for the South African HIV Investment Case |

| Chiu | 2017 | South Africa | AGYW, sex worker | AGYW, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Describe optimization routines developed for the South African HIV Investment Case and compare its results with those generated using conventional cost‐effectiveness analysis methods to examine the incremental benefit of accounting for interaction effects between interventions and non‐linear effects across scale up |

| Cremin | 2017 | Kenya | MSM, sex worker | MSM, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Identify an optimal portfolio of interventions to reduce HIV incidence for a given budget and determine the circumstances in which PrEP could be used in Nairobi, Kenya |

| Akudibillah | 2017 | South Africa | General population, sex worker | Other | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Inform drug‐allocation policy in resource‐limited settings by using a compartmental mathematical model for heterosexual transmission of HIV with treatment targeted by infection status, sexual‐activity level and gender |

| Alsallaq | 2017 | Kenya | AGYW | AGYW | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Compared the impact and costs of HIV prevention strategies focusing on youth (15‐ to 24‐year‐old persons) versus on adults (15+ year‐old persons) in a high‐HIV burden context of a large, generalized epidemic |

| Anderson | 2018 | Kenya | Men, MSM, sex worker, women | Men, MSM, sex worker, women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Quantify the cost of short‐term funding arrangements on the success of future HIV prevention programmes |

| Li | 2018 | China | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Assess the benefits of full implementation of current policies and the timely introduction of novel policies and makes recommendations for future HIV policy responses in China |

| Luz | 2018 | Brazil | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Analyse daily tenofovir/emtricitabine PrEP use in MSM and TGW at high risk of HIV in Brazil using the best available epidemiological, clinical and economic data |

| Stopard | 2019 | South Africa, Tanzania | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Investigate how “real‐world” constraints on the allocative and technical efficiency of HIV prevention programmes affect resource allocation and number of infections averted |

| Zhang | 2019 | China | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluates the epidemiological impact and cost‐effectiveness of implementing PrEP in Chinese MSM over the next two decades |

| Bórquez | 2019 | Peru | TGW | TGW | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Investigate the status of HIV prevention and delivery of care in Peru in terms of infrastructure, staff capacity, budget allocation, activities, organization and outputs; explore perceptions of HIV risk and knowledge of, attitudes towards and intention to use diverse prevention methods among members of the MSM and transgender women communities, as well as adoption by health professionals and decision‐makers; and estimate the impact and cost‐effectiveness of the various interventions to identify cost‐effective and feasible combinations in the Peruvian setting |

| Selinger | 2019 | South Africa | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP, event‐driven PrEP | No | Inform ongoing vaccine access planning elements, including priority populations for whom the pox‐protein HIV vaccine would be expected to have the greatest and/or most efficient public health impact |

| Hu | 2019 | China | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate reductions in HIV transmission that may be achieved through early initiation of ART plus partners’ PrEP |

| Grant | 2020 | Kenya, South Africa, Zimbabwe | AGYW, sex worker, women | AGYW, sex worker, women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Highlight key considerations to feed into policymaking, as countries consider scaling up PrEP across a more broadly defined group of women at risk in sub‐Saharan Africa, and present decision‐makers with a range of important considerations, including PrEP cost‐effectiveness, cost and estimated number of HIV acquisitions averted on PrEP for different groups of women at population level |

| Kazemian | 2020 | India | MSM, PWID | MSM, PWID | No | Daily oral PrEP, event‐driven PrEP | No | Examine the cost‐effectiveness of both PrEP and HIV testing strategies for MSM and PWID in India |

| Pretorius | 2020 | Eswatini, Ethiopia, Haiti, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | AGYW, SDC, sex worker | Other | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimated the impact, cost and cost‐effectiveness of scaling up oral PrEP in 13 countries |

| Jamieson | 2020 | South Africa | ABYM, AGYW, MSM, pregnant and breastfeeding women, sex worker | ABYM, AGYW, MSM, pregnant and breastfeeding women, sex worker | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Analyse the epidemiological impact of PrEP provision to adolescents, young adults, pregnant women, female sex workers, and MSM and estimate the cost and cost‐effectiveness of PrEP |

| Kazemian | 2020 | India | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Develop, validate and demonstrate a novel, practical method to estimate the community benefit of HIV interventions that help prevent transmission of HIV without a dynamic transmission model |

| Wu | 2021 | China | SDC | SDC | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate health economics of antiretroviral‐based strategies for HIV SDC in China |

| Phillips | 2021 | South Africa | AGYW, general population, sex worker | General population, other | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Predict the impact and cost‐effectiveness of PrEP with use concentrated in periods of condomless sex, accounting for effects on drug resistance |

| Ten Brink | 2022 | Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand, Vietnam | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Estimate the impact and cost‐effectiveness of daily versus event‐driven dosing of PrEP for eight Asian countries and compare branded with generic PrEP in China |

| Kripke | 2022 | Lesotho, Mozambique, Uganda | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Examine the role and cost‐effectiveness of HIV prevention in the context of “universal test and treat” in three sub‐Saharan countries with generalized HIV epidemics |

| Jin | 2022 | China | MSM | MSM | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Evaluate the HIV epidemic under several PrEP coverages with or without expanded ART and calculate the cost‐effectiveness of various PrEP scenarios |

| Phillips | 2022 | Sub‐Saharan Africa/South Africa | General population | General population | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Explore the conditions under which widely accessible PrEP could be cost‐effective in sub‐Saharan Africa, assuming a concentration of PrEP use during periods of risk with high adherence to daily pill‐taking |

| Ghayoori | 2022 | Rwanda | Women | Women | No | Daily oral PrEP | No | Examine transmission of HIV among female sex workers, general population, sex clients and MSM to inform scaling up PrEP beyond the highest risk population is considered via an analysis of cost‐effectiveness |

Note: Adeoti (2021) did not refer to the route of administration or PrEP modality in their paper, only “pre‐exposure prophylaxis.” Given when the article was published, we assumed this conceptual mention of PrEP included long‐acting methods, along with daily oral PrEP.

Abbreviations: ABYM, adolescent boys and young men; AGYW, adolescent girls and young women; ART, antiretroviral therapy; DREAMS, Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS‐free, Mentored, Safe; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; PWID, people who inject drugs; TasP, treatment‐as‐prevention; TGW, trans women.

3.5. Geography

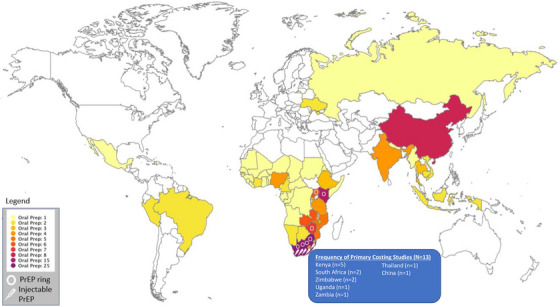

The 66 studies, representing 69 countries (Figure 2), and one study representing all of SSA without sufficient details to make a country assignment were included. Most studies represented a few countries: the top six countries were South Africa (44%, n = 29), Kenya (24%, n = 16), China (14%, n = 9), Zimbabwe (12%, n = 8) and Uganda & Zambia (11%, n = 7). Eleven studies were multicounty. Studies represented the following UNAIDS geographic regions: Southern and Eastern Africa (n = 47), West and Central Africa (n = 4), Asia and the Pacific (n = 12), Eastern Europe and Central Asia (n = 2), Latin America and the Caribbean (n = 5), and the Middle East and North Africa (n = 1). Additional details by region and country are shown in S5A for regions or countries with disaggregated cost and economic data and S5B for all countries cited regardless of disaggregation.

Figure 2.

Distribution of countries and PrEP methods represented in sample of costing studies (N = 66).

3.6. Long‐acting PrEP studies

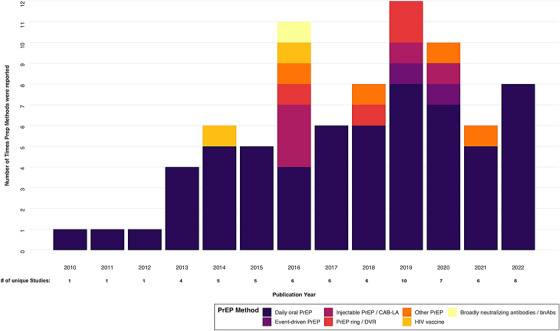

Figure 3 shows the frequency of studies by year and the PrEP method reported. Approximately 15% (n = 10) were specifically LAP studies (Table 2), with two reporting injectable PrEP, one reporting PrEP ring, and seven reporting multiple forms or combinations of LAP. In total, five reported injectable PrEP, four reported on the PrEP ring, and four reported combinations of methods, such as dual HIV and pregnancy prevention or without enough specificity to define the type of LAP. The LAP studies focused on general population women (5), AGYW (4) and female sex workers (3) primarily (Table 2). The 14 country results from 10 LAP studies were mainly conducted in South Africa (n = 8), with results from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda. One study reported LAP data for all global regions (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Frequency of reported PrEP methods, by number of unique costing studies and publication year.

3.7. Description of implementation domains reported in primary cost evaluations

Table 3 displays the distribution of implementation domains among the included studies and Table 4 for LAP studies specifically. Since purpose, scope, and methods can differ by study type, we stratified these findings to discern primary cost studies from secondary or modelled evaluations. Given their direct implications for implementation, we focus our findings on the primary costing studies below.

Table 3.

Frequency of key PrEP implementation domains for all studies, by biomedical HIV prevention method and costing approach

| Total | Daily oral PrEP | Event‐driven PrEP | Injectable PrEP | PrEP ring | Other PrEP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costed implementation domains | All N = 66) | Primary costing (n = 13) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 53) | Primary costing (n = 13) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 48) | Primary costing (n = 0) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 2) | Primary costing (n = 0) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 5) | Primary costing (n = 0) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 4) | Primary costing (n = 0) | Secondary costing or modelling (n = 4) | Primary costing references | Secondary costing or modelling references |

| National coordination, policy and planning | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 47, 52 | 84 | ||||||

| Target setting | |||||||||||||||

| Human resources | 30 | 11 | 19 | 11 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 47, 52, 46, 53 | 96, 95, 132, 98, 84, 89, 133, 135, 114, 125, 122, 88, 109, 87, 110, 127, 128, 93, 111 | |||||

| Communication/awareness raising/demand creation | 21 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 42, 44, 45, 50, 49, 43, 47, 46, 53 | 96, 84, 89, 133, 135, 113, 114, 122, 88, 109, 127, 128 | |||||

| Counselling and adherence support | 25 | 9 | 16 | 9 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 42, 44, 45, 50, 49, 43, 48, 47, 46 | 97, 96, 89, 134, 113, 88, 109, 110, 123, 124, 94, 127, 119, 128, 111, 105 | |||||

| PrEP intervention (commodities) | 38 | 12 | 26 | 12 | 32 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 42, 44, 45, 50, 49, 43, 83, 48, 47, 52, 46, 53 | 96, 95, 132, 98, 84, 108, 134, 135, 113, 114, 86, 125, 122, 88, 109, 123, 124, 116, 127, 91, 128 | ||||

| Supply chain management and logistics | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 47, 52, 53 | 84, 135, 125 | ||||||||

| Laboratory and other commodities | 28 | 10 | 18 | 10 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 48, 47, 46 | 96, 95, 132, 89, 108, 134, 135, 113, 114, 86, 122, 88, 123, 124, 116, 127, 91, 128 | ||||

| Health information systems | |||||||||||||||

| Service delivery approaches | 13 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 42, 44, 45, 83, 52 | 89, 125, 88, 87, 110, 128, 111, 105 | |||||

| Monitoring and evaluation | 11 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 42, 51, 45, 49, 83, 47, 53 | 96, 89, 92, 128 | ||||||

| Implementation science and operations research | |||||||||||||||

| Above‐site activities | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 47, 52, 46 | 113, 122 | ||||||||

| Indirect/overhead | 20 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 47, 52, 46, 53 | 98, 89, 114, 88, 87, 124, 127, 128, 93 | |||||

| Other costs | 14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 42, 51, 45, 50, 43, 47, 53 | 98, 135, 99, 116, 127, 93, 129 | |||||||

Note: The one PrEP‐bnAbs secondary costing or modelling study (Citation 84) costed policy & planning, awareness raising & demand generation, PrEP commodities and supply chain logistics & management. Of the two PrEP‐HIV vaccine secondary costing or modelling studies, one (Citation 111) costed human resources, counselling and PrEP integration into non‐HIV services.

Among primary costing studies reporting integration data (N = 5), studies costed the integration of PrEP into sexual and reproductive health services (n = 4), family planning services (n = 3), and maternal and child health services (n = 1). For secondary costing or modelling studies (N = 6), sexual and reproductive health services was the most common (n = 4), followed by family planning (n = 1), antenatal care (n = 1), and HIV treatment and methadone maintenance treatment (n = 1).

Abbreviation: PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis.

Table 4.

Frequency of key PrEP implementation domains for all LAP studies (N = 10)

| Costed implementation domains | Total N = 10 | Injectable PrEP n = 5 | PrEP ring n = 4 | Other PrEP n = 4 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National coordination, policy and planning | 1 | 1 | 1 | 84 | |

| Target setting | |||||

| Human resources | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 84, 87, 88, 89, 93 |

| Communication/awareness raising/demand creation | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 84, 88, 89 |

| Counselling and adherence support | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 88, 89 |

| PrEP intervention (commodities) | 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 84, 85, 86, 92, 88, 87, 90, 91, 93 |

| Supply chain management and logistics | 1 | ||||

| Laboratory and other commodities | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 86, 88, 89, 91 |

| Health information systems | |||||

| Service delivery approaches | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 87, 88, 89 |

| Monitoring and evaluation | 2 | 2 | 1 | 89, 92 | |

| Implementation science and operations research | |||||

| Above‐site activities | |||||

| Indirect/overhead | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 87, 88, 89, 93 |

| Other costs | 1 | 93 |

Abbreviations: LAP, long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis.

Among the 13 primary cost studies, the most reported implementation domains were: PrEP‐intervention‐commodities (n = 12), laboratory and other commodities (n = 10), human resources (n = 11), indirect/overhead costs (n = 11), communication/awareness raising/demand creation (n = 9), counselling and adherence support (n = 9), and monitoring and evaluation (n = 7). A few studies included the cost of integration into non‐HIV services (n = 5), above‐site activities (n = 3), supply chain management and logistics (n = 3), or national coordination policy and planning (n = 2). No primary cost study included target setting, health information systems, or research. None of the primary costed studies included LAP. Of the 13 primary cost studies, 53.8% (n = 7) were conducted in government or public facilities (Table 5). Most primary studies estimated average costs (n = 9) and incremental costs (n = 7). Three studies also modelled cost‐effectiveness. Most of the costing studies utilized the health system perspective (n = 11) and applied a discount rate (n = 11). Two studies did not report conflict of interest statements. Similar details for modelled studies are reported in S6.

Table 5.

Economic analysis features and analytic approaches of primary costing studies (N = 13).

| Total (N = 13) | Daily oral PrEP (n = 13) | Event‐driven PrEP (n = 0) | Injectable PrEP (n = 0) | PrEP ring (n = 0) | Other PrEP (n = 0) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility type | |||||||

| NGO & NGO facility | 5 | 5 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 52 | ||||

| Private‐for‐profit & private non‐profit & private facility | 2 | 2 | 52, 53 | ||||

| Government & public facility | 7 | 7 | 44, 49, 43, 48, 47, 52, 53 | ||||

| Type of economic analysis | |||||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | 8 | 8 | 42, 44, 45, 50, 43, 83, 48, 47 | ||||

| Cost‐benefit | |||||||

| Cost‐utility | 3 | 3 | 44, 83, 48 | ||||

| Average costing | 9 | 9 | 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 47, 52, 46, 53 | ||||

| Incremental costing | 7 | 7 | 42, 44, 45, 43, 83, 48, 47 | ||||

| Costing approach | |||||||

| Guideline/normative | 3 | 3 | 51, 50, 83 | ||||

| Real world/actual | 5 | 5 | 42, 44, 49, 48, 47 | ||||

| Both | 5 | 5 | 45, 43, 52, 46, 53 | ||||

| Economic v. financial costing | |||||||

| Economic costing | 9 | 9 | 44, 51, 45, 49, 43, 47, 52, 46, 53 | ||||

| Financial costing | 4 | 4 | 42, 50, 83, 48 | ||||

| Perspective | |||||||

| Health system | 11 | 11 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 48, 52, 46, 53 | ||||

| Societal | |||||||

| Both | 1 | 1 | 47 | ||||

| Not reported | 1 | 1 | 83 | ||||

| Discount rate reported | 11 | 11 | 42, 44, 51, 50, 49, 43, 83, 48, 47, 52, 53 | ||||

| Conflict of interest | |||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 46 | ||||

| No | 10 | 10 | 42, 44, 51, 45, 50, 49, 43, 83, 52, 53 | ||||

| Not reported | 2 | 2 | 48, 47 | ||||

| Approach | |||||||

| Observed | 9 | 9 | 42, 44, 51, 49, 43, 47, 52, 46, 53 | ||||

| Observed + modelled | 4 | 4 | 45, 50, 83, 48 |

Abbreviations: NGO, non‐governmental organization; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis.

3.8. Implementation assumptions in primary cost evaluations

All primary cost studies reported costs in USD; 11 studies included overhead costs. All studies reporting discount rates (N = 11) used 3%. Considerable heterogeneity persisted in the activities described in the primary cost studies, the costs estimated, and the units defined in all other implementation domains. For instance, within the commonly reported PrEP commodities domain, average drug costs were described as cost per implementation scenario [42, 43], costs across all sites and per site [44], cost per couple [43, 45], cost per client [46, 47, 48], costs per bottle [43, 49, 50], per person‐year [43, 50], and per month [45, 47]. The recurrent drug costs cited ranged from $24.43 to $382.00. PrEP commodities were only included if the input costs of the drug were explicitly reported, could be disaggregated or were cited as being included in the unit cost. The human resources domain included clinicians, social workers, and counsellors staff time based on time and motion studies [42]. Other studies included the site doctor, pharmacist, peer educators [44], and administrators [51]. Merely three studies described start‐up training [45, 46, 49]. For the more infrequently costed domains, policy and planning costs were estimated for stakeholder coordination required to start up and microplanning [47, 52], and supply chain costs were estimated for central storage and distribution fees and a one‐time PrEP importation fee [47, 52, 53].

3.9. Primary costing study outcomes

Table 7 summarizes average and incremental cost outcomes reported across the 13 primary cost studies and Tables 8 and 9 detail cost and cost‐effectiveness outcomes of studies by scenarios costed. The 13 studies reported 11 unique outcome indicators. Cost per person/client‐month (n = 6) was the most frequently reported outcome, followed by annual costs (n = 4), cost per visit (n = 4), and cost per person/client‐year (n = 3). Three primary costing studies also reported the results of cost‐effectiveness analyses: one study reported an incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) without clearly defining the time horizon; one reported an ICER (cost per acquisition averted) over a 10‐year horizon; and the third reported the incremental cost‐effectiveness per quality‐adjusted life year (QALY) gained in a 5‐year time horizon. No single cost or cost‐effectiveness outcome was measured by all studies utilizing the same analytic approach. The highest frequency of studies reported on oral PrEP among AGYW, followed by SDC.

Table 7.

Economic analysis features and analytic approaches of secondary costing or modelling studies

| Author | Year | Country | PrEP method | Population | Total costs | Annual costs | Total 5‐year | Total 10‐year | Cost per person/client | Cost per person/client‐month | Cost per person/client‐year | Cost per couple | Cost per couple‐year | Cost per visit (initiation, follow‐up, any visit) | Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year | Discounted incremental cost of PrEP strategies over 5‐year | Incremental cost of PrEP per couple | Annual incremental cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suraratdecha | 2018 | Thailand | Daily oral PrEP | MSM | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Wong | 2018 | China (Hong Kong) | Daily oral PrEP | MSM | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Ying | 2015 | Uganda | Daily oral PrEP | SDC | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Eakle | 2017 | South Africa | Daily oral PrEP | Sex worker | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Roberts | 2019 | Kenya | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Irungu | 2019 | Kenya | Daily oral PrEP | SDC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Hughes | 2020 | Zimbabwe | Daily oral PrEP | SDC | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Peebles | 2021 | Kenya | Daily oral PrEP | Other (see below) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Wanga | 2021 | Kenya | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Hendrickson | 2021 | Zambia | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW/GP/other (FSW & MSM together) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Okal | 2022 | Kenya | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mudimu | 2022 | South Africa | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mangenah | 2022 | Zimbabwe | Daily oral PrEP | AGYW/men/women | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Total | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Note: When studies listed costs as “Total annual,” we recorded them as Annual costs and only noted Total costs if they were framed exactly as such (i.e. “Total costs”).

Abbreviations: AGYW, adolescent girls and young women; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; SDC, sero‐different couples.

Table 8.

Cost outcomes of primary costing studies

| Author | Population(s) | Scenarios | Findings | Sensitivity analysis performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suraratdecha | MSM |

Cohort study (includes MOPH and project staff), which presented two implementation options: Option 1: one visit for initial PrEP counselling and recruitment, four additional HIV tests, two tests for creatinine, one HBs Ag test, 12 months TDF/FTC combination, six visits for maintenance support (counselling) Option 2: option 1 package plus two times upgraded STIs screening (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis rapid test, nucleic acid amplification test) |

Cohort study total annual costs associated with PrEP initiation and clinic visits Personnel: $1452, Lab supplies: $1406, PrEP drugs: $14,106, Other supplies: $242 Total: $17,206 Option 1: Unit cost of PrEP recommended package (per person per year) Personnel: $24.66, Supplies: $10.36, Tenofovir/Entricitabine (12 bottles: 1 pill/day): $186.33 Total unit cost: $221.34 Total unit cost with 0.7% overhead: $222.89 Total unit cost with 0.7% overhead and 22% demand generation activities: $271.59 Option 2: Unit cost of PrEP recommended package (per person per year) Personnel: $25.63, Supplies: $41.41, Tenofovir/Entricitabine (12 bottles: 1 pill/day): $186.33 Total unit cost: $253.37 Total unit cost with 0.7% overhead: $255.14 Total unit cost with 0.7% overhead and 22% demand generation activities: $310.88 |

No (Cost‐effectiveness only) |

| Providing PrEP to only high‐risk MSM (defined as having engaged in condomless sex with casual or known HIV‐positive partners) versus all MSM, regardless of risk |

TOTAL 5‐YEAR PROGRAMME COST: PrEP provided to High‐risk MSM $41.99 (M) PrEP provided to All MSM $147.14 (M) |

|||

| Wong | MSM |

Basecase with 10%, 30% and 90% coverage of PrEP involving low‐risk and high‐risk MSM (i.e. non‐targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage and high‐risk MSM only (i.e. targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage Plans (apply to both scenarios) Plan A: PrEP priced at the market rate: $7880/year Plan B: PrEP priced at the generic rate: $519/year Plan C: PrEP is free |

DISCOUNTED INCREMENTAL COST OF PrEP STRATEGIES OVER 5‐YEAR TIME HORIZON Plan A Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $123,458,936; $370,266,861; and $1,113,780,354 Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $52,571,166; $157,200,505; and $472,011,282 Plan B Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $17,294,670; $51,648,582; and $157,156,635 Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $7,459,389; $21,831,597; and $65,661,580 Plan C Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $9,806,914; $29,176,464; and $89,686,050. Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $4,277,659; $12,284,040; and $37,001,772 |

Yes |

| Test‐and‐Treat included a high rate of diagnosis and treatment initiation (minimum 90% from 2017) with 10%, 30% and 90% coverage of PrEP involving low‐risk and high‐risk MSM (i.e. non‐targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage and high‐risk MSM only (i.e. targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage |

DISCOUNTED INCREMENTAL COST OF PrEP STRATEGIES OVER 5‐YEAR TIME HORIZON Plan A Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $158,411,503; $398,568,822; and $1,127,434,311 Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $89,432,361; $190,572,365; and $496,573,340 Plan B Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $ 52,137,608; $79,665,459; and $170,226,003 Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $44,267,840; $55,056,540; and $89,865,774 Plan C Respective costs of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $44,642,119; $57,173,233; and $102,714,188 Respective costs of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $41,082,391; $45,498,622; and $ 61,180,726 |

|||

| Ying | SDC | As‐studied |

INCREMENTAL COSTS (PER COUPLE) As‐studied (total clinical HIV treatment + PrEP): $1058, As‐studied SoC (HIV treatment without PrEP): $650, As‐studied PrEP: $408 |

No (Cost‐effectiveness only) |

| MoH |

INCREMENTAL COSTS (PER COUPLE) MoH total clinical: (HIV treatment + PrEP) $453, MoH standard of care (i.e. HIV treatment without PrEP): $361, MoH PREP: $92 MoH Assumptions showcasing reduction in as‐studied to MoH PrEP price As‐studied with PrEP with public‐sector staff salaries: $370, and reduced medication costs: $254, and fewer lab tests: $101, and PrEP task‐shifting: $92 |

|||

| MoH adds PrEP programme for all high‐risk SDC (i.e. when the HIV‐negative partner is aged < = 25 years and both partners are in the top 15th percentile in number of casual sexual partners). Scenario also assumes 40% baseline ART coverage, 80% of high‐risk couples are without CD4/VL criteria and 80% PrEP coverage among high‐risk couples | $219 million over 10 years | |||

| Eakle | Sex worker | N/A |

PrEP PER PERSON‐YEAR, Y1 Average: $126.60 (Johannesburg: $146.60, Pretoria: $106.60) COST PER VISIT Outreach contact visit—Average: $2.80 (Johannesburg: $3.00, Pretoria: $2.60) VCT Session—Average: $18.10 (Johannesburg: $21.2, Pretoria: $15.10) PrEP Enrolment Visit —Average: $34.70 (Johannesburg: $40.40, Pretoria: $29.00) PrEP Monitoring Visit —Average: $35.20 (Johannesburg: $37.40, Pretoria: $33.00) PrEP Refill Visit —Average: $6.80 (Johannesburg: $7.40, Pretoria: $6.20) |

No |

| Roberts | AGYW | As‐implemented |

Total annual programme cost: $204,253 Average cost of per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $26.52 UNIT COST BY CLINICAL ACTIVITY PrEP screening —Total annual cost: $69,876; Total unit cost (variable + fixed): $2.91 PrEP initiation —Total annual cost: $80,525; Total unit cost (variable + fixed): $19.18 PrEP follow‐up ‐Total annual cost: $53,852; Total unit cost (variable + fixed): $12.16 |

Yes |

| Service delivery modification: Postponed creatine testing to first follow‐up visit |

Total annual cost: $188,932 Cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $24.53 |

|||

| Service delivery modification: Prioritized delivery to clients at high risk for HIV infection |

Total annual cost: $175,793 Cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $31.88 |

|||

| As‐implemented scenario with public‐sector clinical staff salaries |

Total annual cost: $199,613 Cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $25.92 |

|||

| As‐implemented scenario with MOH supervision and public‐sector clinical staff salaries |

Total annual cost: $138,609 Cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $18.00 |

|||

| As‐implemented scenario with facility creatinine testing, MOH supervision and public‐sector clinical staff salaries |

Total annual cost: $127,421 Cost per client‐month of PrEP dispensed: $16.54 |

|||

| Irungu | SDC | As‐studied |

ANNUAL COST OF DELIVERING INTEGRATED PrEP AND ART TO SDC Total cost: $757,483.58; Cost per couple: $1.454.87 ANNUAL INCREMENTAL COST OF ADDING PREP TO CURRENT ART PROGRAMME Total cost: $441,555.40; Cost per couple: $305.75 |

Yes |

| Current care and PrEP with MoH costs |

ANNUAL COST OF DELIVERING INTEGRATED PrEP AND ART TO SDC Total cost: $361,304.58; Cost per couple: $250.19 ANNUAL INCREMENTAL COST OF ADDING PREP TO CURRENT ART PROGRAMME Total cost: $125,338.15; Cost per couple: $86.79 per couple |

|||

| Current care & PrEP costs (removing research costs) |

ANNUAL COST OF DELIVERING INTEGRATED PrEP AND ART TO SDC Total cost: $962,032.84; Cost per couple: $66.16 |

|||

| Hughes | SDC | SAFER |

Individual strategy—PrEP: $1229 per couple Multiple strategies: ART‐VL + PrEP: $1709 per couple; PrEP + SW: $1659 per couple; PrEP + AVI: $1242 per couple |

Yes |

| High intensity (study‐level) with real‐world prices |

Individual strategy—PrEP: $403 per couple Multiple strategies: ART‐VL + PrEP: $517 per couple; PrEP + SW: $771 per couple; PrEP + AVI: $408 per couple |

|||

| Target intensity, incremental cost added to CP |

Individual strategy—PrEP: $266 per couple Multiple strategies: ART‐VL + PrEP: $483 per couple; PrEP + SW: $563 per couple; PrEP + AVI: $291 per couple |

|||

| Target intensity, incremental cost added to SOC |

Individual strategy—PrEP: $88 per couple Multiple strategies: ART‐VL + PrEP: $166 per couple; PrEP + SW: $387 per couple; PrEP + AVI: $114 per couple |

|||

| Peebles | Other (see below) | N/A |

FINANCIAL COSTS Total: $91,175; Cost per PrEP Client: $35.52; Cost per person‐month of PrEP: $10.31 ECONOMIC COSTS Total: $188,584; Cost per PrEP Client: $73.46; Cost per person‐month of PrEP: $21.32 |

No |

| Wanga | AGYW | POWER Study scenario |

Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs Annual cost: $44,933; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $28.92 Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs by visit type Initiation—Annual cost: $23,520; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $47.09 Follow‐up—Annual cost: $20,896; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $20.99 |

No |

| MoH scenario |

Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs Annual cost: $22,566; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $14.52 Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs by visit type Initiation—Annual cost: $10,156; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $20.33 Follow‐up—Annual cost: $11,997; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $12.05 |

|||

| Scaled‐MoH scenario |

Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs Annual cost: $83,196; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $10.88 Estimated Total (variable + fixed) economic costs by visit type Initiation—Annual cost: $38,352; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $11.84 Follow‐up—Annual cost: $43,213; Cost per client‐month of PrEP: $9.81 |

|||

| Hendrickson | AGYW | Integrated into DREAMS, including community sensitization and demand creation through short‐term mobilizers |

Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year: $320 Total average cost per PrEP‐client per year: $394 Total cost per person‐month: $33 |

No |

| GP | Integration Model 1: Outreach using trained CHW to sensitize community about PrEP and refer interested people to nearest clinic |

Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year: $530 Total average cost per PrEP‐client per year: $760 Total cost per person‐month: $63 |

||

| Integration Model 2: Site readiness through preliminary site assessments, trainings, community consultations and global technical assistance |

Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year: $381 Total average cost per PrEP‐client per year: $406 Total cost per person‐month: $34 |

|||

| Integration Model 3: Community HIV Epidemic Model of care, focused on community education, mobilization, PrEP sensitization, and training CHW on key population sensitivity and PrEP services |

Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year: $586 Total average cost per PrEP‐client per year: $659 Total cost per person‐month: $55 |

|||

| Other (FSW & MSM together) | Targeted community‐based demand creation with referrals to local facilities for PrEP initiation and follow‐up |

Total recurrent cost per PrEP‐client per year: $350 Total average cost per PrEP‐client per year: $425 Total cost per person‐month: $35 |

||

| Okal | AGYW | N/A |

Costs of delivering dreams interventions Urban Total: $215,440; Cost of providing DREAMS interventions to 1 AGYW: $67 Peri‐urban Total: $408,884; Cost of providing DREAMS interventions to 1 AGYW: $129 |

Yes |

| Mudimu | AGYW | As‐implemented |

Incremental cost of community‐based prep provision Standard of Care Annual cost: $135,314; Cost per person month of PrEP: $105.74 Club Annual cost: $135,143.42; Cost per person month of PrEP: $105.61 Individual Annual cost: $135,791.40; Cost per person month of PrEP: $106.09 |

No |

| DoH scenario |

Incremental cost of community‐based prep provision Standard of Care Annual cost: $70,944.44; Cost per person month of PrEP: $55.46 Club Annual cost: $70,811.93; Cost per person month of PrEP: $55.32 Individual Annual cost: $71,227.59; Cost per person month of PrEP: $55.65 |

|||

| Scaled‐DoH scenario |

Incremental cost of community‐based prep provision Standard of Care Annual cost: $142,342.77; Cost per person month of PrEP $13.99 Club Annual cost: $144,881.73; Cost per person month of PrEP: $15.48 Individual Annual cost: $133,822.61; Cost per person month of PrEP: $26.40 |

|||

| Mangenah | AGYW | N/A |

Cost per person‐year of receiving oral PrEP: $839 Average costs by visit type Initiation: $240 per client initiated, Month 3 follow‐up: $434 per client continued to 3 months, Month 6 follow‐up: $844 per client continued to 6 months |

Yes |

| Men | N/A |

Cost per person‐year of receiving oral PrEP: $1219 Average costs by visit type Initiation: $215 per client initiated, Month 3 follow‐up: $712 per client continued to 3 months, Month 6 follow‐up: $1363 per client continued to 6 months |

||

| Women | N/A |

Cost per person‐year of receiving oral PrEP: $857 Average costs by visit type Initiation: $243 per client initiated, Month 3 follow‐up: $480 per client continued to 3 months, Month 6 follow‐up: $828 per client continued to 6 months |

Abbreviations: AGYW, adolescent girls and young women; ART‐VL, antiretroviral therapy with frequent viral load testing; AVI, manual artificial vaginal insemination; CP, Current Practice; DoH, Department of Health; FSW, female sex workers; GP, general population; MoH, Ministry of Health; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; SDC, sero‐different couples; SOC, Standard of Care; SW, semen washing; TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil and emtricitabine.

Table 9.

Cost‐effectiveness outcomes of primary costing studies

| Author | Population(s) | Scenarios | Findings | Sensitivity analysis performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suraratdecha | MSM | Providing PrEP to only high‐risk MSM (defined as having engaged in condomless sex with casual or known HIV‐positive partners) versus all MSM, regardless of risk |

Cost‐Effectiveness: PrEP provided to High‐risk MSM: $3.99 (M) lifetime treatment costs averted PrEP provided to All MSM: $9.84 (M) lifetime treatment costs averted ICER OVER 5‐YEAR TIME HORIZON PrEP provided to High‐risk MSM: $4836 per DALY averted; $68,468 per HIV infection averted PrEP provided to All MSM: $7089 per DALY averted; $100,367 per HIV infection averted |

Yes |

| Wong | MSM |

Basecase with 10%, 30% and 90% coverage of PrEP involving low‐risk and high‐risk MSM (i.e. non‐targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage and high‐risk MSM only (i.e. targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage Plans (apply to both scenarios) Plan A: PrEP priced at the market rate: $7880/year Plan B: PrEP priced at the generic rate: $519/year Plan C: PrEP is free |

DISCOUNTED INCREMENTAL COST‐EFFECTIVENESS (INCREMENTAL $/QALY GAINED) OF PrEP STRATEGIES OVER 5‐YEAR TIME HORIZON Plan A Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $1,842,204; $1,745,524; and $2,115,619 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $2,162,072; $1,583,136; and $1,642,874 Plan B Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $258,064; $243,483; and $298,518 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $306,779; $219,862; and $228,540 Plan C Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $146,335; $137,545; and $170,358 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $175,926; $123,710; and $128,788 |

Yes |

| Test‐and‐Treat included a high rate of diagnosis and treatment initiation (minimum 90% from 2017) with 10%, 30% and 90% coverage of PrEP involving low‐risk and high‐risk MSM (i.e. non‐targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage and high‐risk MSM only (i.e. targeting approach) with low or high adherence usage |

DISCOUNTED INCREMENTAL COST‐EFFECTIVENESS (INCREMENTAL $/QALY GAINED) OF PrEP STRATEGIES OVER 5‐YEAR TIME HORIZON Plan A Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $929,125; $1,345,390; and $1,985,645 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $668,940; $956,132; and $1,366,821 Plan B Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $305,830; $268,915; and $299,803 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $331,116; $276,227; and $247,356 Plan C Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Non‐targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $261,863; $192,991; and $180,901 Respective incremental cost‐effectiveness of Targeting 10%; 30%; and 90% are $307,290; $228,274; and $168,400 |

|||

| Ying | SDC | MoH adds PrEP programme for all high‐risk SDC (i.e. when the HIV‐negative partner is aged < = 25 years and both partners are in the top 15th percentile in number of casual sexual partners). This scenario also assumes 40% baseline ART coverage, 80% of high‐risk couples are without CD4/VL criteria and 80% PrEP coverage among high‐risk couples |

ICER OVER 10‐YEAR HORIZON $1340 per HIV infection averted $5354 per DALYs averted |

Yes |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DALYs, disability‐adjusted life year; ICER, incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; QALY, quality‐adjusted life year; SDC, sero‐different couples; VL, viral load.

3.10. Implementation domains in secondary data or modelled studies

A lower percentage of modelled than primary costing studies included the costs of any implementation. Among the 53 modelled studies (Table 6), the cost of PrEP commodities was the most frequently included (40%, n = 21), followed by human resources (36%, n = 19). Table 6 summarizes all modelled studies. As shown in S6, most modelled studies were cost‐effectiveness (N = 41), followed by cost‐utility studies (N = 15). Evaluations mostly took a guidelines approach (N = 32), from the health system perspective (N = 42). About 69.8% reported discount rates (N = 37) (Tables 6).

Table 6.

Economic analysis features and analytic approaches of secondary costing or modelling studies (N = 53).

| Total (N = 53) | Daily oral PrEP (n = 48) | Event‐driven PrEP (n = 2) | Injectable PrEP (n = 5) | PrEP Ring (n = 4) | Other PrEP (n = 4) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility type | |||||||

| NGO & NGO facility | 4 | 4 | 125, 122, 99, 116 | ||||

| Private‐for‐profit & private non‐profit & private facility | 1 | 1 | 125 | ||||

| Government & public facility | 3 | 3 | 95, 113, 122 | ||||

| Type of economic analysis | |||||||