Abstract

Normal and abnormal/pathological status of physiological processes in the human organism can be characterized through Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) emitted in breath. Recently, a wide range of volatile analytes has risen as biomarkers. These compounds have been addressed in the scientific and medical communities as an extremely valuable metabolic window. Once collected and analysed, VOCs can represent a tool for a rapid, accurate, non-invasive, and painless diagnosis of several diseases and health conditions. These biomarkers are released by exhaled breath, urine, faeces, skin, and several other ways, at trace concentration levels, usually in the ppbv (μg/L) range. For this reason, the analytical techniques applied for detecting and clinically exploiting the VOCs are extremely important. The present work reviews the most promising results in the field of breath biomarkers and the most common methods of detection of VOCs. A total of 16 pathologies and the respective database of compounds are addressed. An updated version of the VOCs biomarkers database can be consulted at: https://neomeditec.com/VOCdatabase/

Keywords: Volatile organic compounds, VOCs, Biomarkers, Exhaled breath, Breath sampling

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The role of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in the medical field has been extraordinarily growing in the last two decades. These compounds are produced by numerous biological processes of the human body and can be released to the exterior in several ways. The most well-known ways of VOCs emission from the organism are exhaled breath [1], perspiration [2], urine [3], faeces [4], and even lacrimal fluid [5]. Since they are formed or emitted as a direct result of normal and abnormal biological processes, their detection, identification, and quantification can be an open window to the interior of the organism. They can represent a valuable source of information about health conditions or pathologies under development, and even about eventual consequences of medical treatments [6,7].

As mentioned, the interest of the scientific community in the role of VOCs as biomarkers is considerably increasing. This evolution can be seen in Fig. 1 A) whose graph represents the rising of the number of scientific papers published simultaneously on the topics of volatile organic compounds and exhaled breath. It is possible to notice that, in just a matter of twenty years, the number of scientific articles has risen from around 1000 per year to more than 5000 per year. From this literature research, one can infer the potential of volatile organic compounds as exhaled breath biomarkers for the detection of a wide range of pathologies. Fig. 1 B) represents the percentual relevance of the 16 main diseases with an already developed scientific base regarding the usefulness of VOCs in their detection. These numbers were collected from the scientific database “web of science”.

Fig. 1.

(A) Number of scientific articles published per year during the last twenty years regarding the field of volatile organic compounds as breath biomarkers to the diagnosis of health conditions; (B) Treemap of the percentual value of the number of papers addressing specific pathologies in the field of volatile organic compounds as biomarkers in the exhaled breath. Data was collected from the scientific database “web of science”.

As promising results have been achieved with analyses of breath samples performed in independent studies and with different analytical techniques and procedures, the present work intends to review the most recent and relevant scientific research projects, from January 2010 to December 2021, where the exhaled breath VOCs are addressed and studied as potential biomarkers or identification tools for health conditions and pathologies of the human organism. Here, the main analytical techniques currently used for the detection of VOCs are briefly revised, the most recent works associated with the forwarded pathologies are addressed and, in addition, a database of VOCs is included at the end of the review and can be consulted at: https://neomeditec.com/VOCdatabase/.

Volatile organic compounds: what are they?

The European Union (EU) directive on the limitation of emissions of volatile organic compounds defines VOCs as “… any organic compound …, having at 293.15 a vapour pressure of 0.01 or more, or having a corresponding volatility …” [8]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in its turn, defines these compounds as “… any organic compound having an initial boiling point less than or equal to 250 measured at a standard atmospheric pressure of 101.3 .” [9]. Independently of the minor differences, the general definition of VOCs is practically standard: a volatile organic compound is an organic compound, meaning that its main structural atom is carbon, which is volatile at room temperature (20 ) and 1 of pressure [[10], [11], [12]].

The range of sources responsible for the emission of VOCs, despite being wide, is constituted of very common and ordinary elements. Ranging from natural products, foods and cooking, personal care and cleaning products, and furniture, to pharmaceutic drugs, plastics, fuels, or construction materials, VOCs can be effortlessly emitted by most of the daily-use objects and elements [[13], [14], [15]]. In this way, the emission of VOCs occurs not only in private (private houses, vehicles, or working locations) and public (schools, hospitals, shopping centres, or public transportation) indoor environments but also in outdoor environments like gardens and public parks [[16], [17], [18]]. The human body is no exception. Numerous VOCs have been scientifically proved to be produced and emitted by several human organs as a result of numerous biological processes [[19], [20], [21], [22]].

Varying from almost inert to extremely reactive, VOCs have the capacity of traversing most of the biological membranes, such as pulmonary, ocular, and cutaneous tissues [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. Due to this fact, the VOCs found in any kind of indoor or outdoor environment can enter or be absorbed by the human body causing health conditions and pathologies as consequences of the exposure [[27], [28], [29]]. Simpler reactions like skin pruritus and ocular allergies have been reported [[30], [31], [32]]. Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and other inflammatory respiratory pathologies have also been assessed as VOCs-provoked pathologies [[33], [34], [35]]. In more complex scenarios, several forms of cancer were identified as being caused by chronic exposure to VOCs; in fact, benzene and formaldehyde are among the most carcinogenic VOCs and are directly responsible for some severe forms of cancer like lung cancer, oral cancer, and even prostate cancer [[36], [37], [38]]. In the opposite direction, the endogenously-produced VOCs of the body can also traverse the human tissues and be detected in the exterior through exhaled breath [24], saliva [39], perspiration [40], faeces [41], and urine [42], among other ways [22,40]. Once collected and analysed, the VOCs emitted in these body excretions represent an ideal window for the interior of the body and are potential biomarkers to assess numerous biological processes and health conditions occurring in the human organism.

The current definition states that a biomarker is “… a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention …” [43]. A biomarker can, indeed, be a biological signal of several natures, that can be accurately measured, whose result is reproducible over time, and that is always associated with a specific normal or abnormal event of the human organism [44,45]. As mentioned, VOCs are among the main human-produced biomarkers and have enabled the study and diagnosis of a vast range of pathologies and health conditions, addressed in due time.

Volatile organic compounds: detection and analysis

It is relevant to briefly summarize the main analytical techniques that are currently being used for detecting and analysing these analytes.

A significant part of the scientific papers published in the field of VOCs as exhaled breath biomarkers claim to have used an electronic nose (E-nose) for the detection of the analytes. In fact, the concept of e-nose is quite vast because it does not correspond to a specific and independent analytical technique. E-nose is the nomenclature typically applied to define any electronic prototype or device that enables the analysis of VOCs so, any system based on arrays of gas sensors/detectors or that employ some type of separation technology can be referred to as E-nose. Chromatographic and spectrometric techniques, for example, are vulgarly called e-nose by some authors [46,47], while others use this terminology to talk exclusively about electronic devices based on arrays of gas sensors [48]. Independently of the terminology, there are a considerable number of interesting papers addressing the implementation of gas sensors arrays for the detection of VOCs in exhaled breath and, among the analytical techniques, the most utilized ones are gas chromatography (GC), mass spectrometry (MS), ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), and combinations between them [49,50].

Gas sensors array-based E-noses

The development of electronic prototypes and devices based on arrays of gas sensors is a common practice in the fields of VOCs detection and biomarkers identification. Gas sensor is a vulgar definition for a sensor specifically developed to detect one or a limited number of analytes. There are several types of sensors, namely quartz crystal microbalance sensors (QCMS), photoionization detector sensors (PIDS), surface acoustic wave sensors (SAWS), solid-state electrochemical sensors (SSES), and metal oxide sensors (MOS) however, independently of the used type, all of them are highly responsive, selective, stable, simple, and low-priced [48]. Since the sensors only enable the detection of a limited number of analytes, it is common to assemble arrays of sensors with distinct finalities, widening the range of detectable analytes with a single system [51,52].

The arrays are usually assembled in a microcontroller and once connected to a computer, they allow the collection of qualitative and quantitative data regarding the detected analytes [53]. To access that data, the sensors array is exposed to the volatile sample and, if the sample contains the analytes that the sensors are prepared to detect, they will respond to the presence of those compounds. This response is different for the several types of sensors. In the case of the MOS, for example, these sensors change the conductivity of their sensing element in response to being exposed to the gases [54]. The response of the sensors is, then, registered and converted to a spectrum or to numerical data by the computer to be posteriorly processed [55]. The described procedure was used by Binson et al. (2021) in their study. The authors assembled an e-nose based on an array of five distinct sensors to analyse exhaled breath samples of a cohort of 88 volunteers (39 healthy individuals, 22 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and 27 lung cancer patients). The gas sensors array-based system developed in the study enabled the authors to classify the lung cancer patients with accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity levels of 78.7, 72.5 and 82.4%, respectively. Similar values were achieved in the classification of COPD patients [56]. Fig. 2 describes a generic analysis through a sensor array-based system.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of a generic Gas Sensors Array-based system for breath analysis.

Gas chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC) is an analytical technique often applied as a pre-separation method prior to further analyses with other analytical devices like mass spectrometers or ion mobility spectrometers. These devices enable the separation of a sample into its constituting analytes and provide information about their molecular composition and concentration. The GC section, specifically, can separate volatile analytes based on their solubility, based on their capacity of adsorbing to the walls of the chromatographic column, and whose boiling point ranges from near 0 to over 700 K. The temperature is an important factor for the column performance and, as said, the GC works at a wide range of temperatures so, proper temperature control is crucial for a correct analysis [57,58].

During a GC measurement, the sample is introduced into the system and the analytes are distributed between two phases, the stationary phase, and the mobile phase. The mobile phase moves in a specific direction and is responsible for transporting the compounds through the entire column. This transportation can occur due to gravitational, capillary or pressure forces. In opposition, the stationary phase, usually a solid or an immobilized liquid, counteracts the transport rate of the mobile phase. Since the different analytes have different capacities to adsorb to the walls and different solubility, they will elute from the column at distinct moments. The detector, at the end of the system, registers the time that each compound requires to cross the entire circuit, called retention time. This time enables the identification of all the analytes present in the initial sample [59,60]. Fig. 3 schematizes a GC measurement. As mentioned, the sample is introduced into the chromatographic column where the analytes are separated considering their intrinsic capacity of adsorbing to the coating of the inner wall of the columns. Once the analytes elude from the column, they are detected, and a final spectrum is produced. This detection is achieved at exact times that are analyte-specific and correspond to the time required by each analyte to elude from the chromatographic column.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of Gas Chromatography (GC) measurements.

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is, perhaps, the most used detection technique among all the addressed ones. It enables to selectively identify and quantify a vast range of analytes, as well as, to study their molecular structure and composition. MS is the analytical technique that generates more data from the measurements of the analytes and even enables the analysis of any element that can be ionized, organic or not. To assess all this data, MS bases its working principle on the experimental measurement of the mass of gas-phase ions produced from the molecules of an analyte. Its detection limits can go, for some cases, as low as ppbv, without the necessity of employing any kind of pre-concentration steps, however, it has some limitations regarding VOCs analysis in clinical settings due to the elevated temperatures used during the analysis that can contribute to the degradation of the sample and consequent loss of some analytes [61,62].

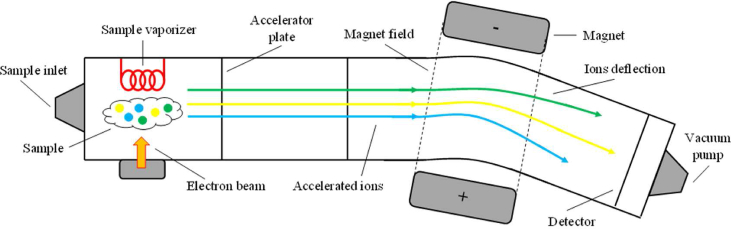

Very briefly, an MS measurement starts with the injection of the sample into the spectrometer. By bombarding it with a beam of energetic electrons, the molecules are ionized and disintegrate into multiple fragments. Some of these fragments are positive gas-phase ions. Once formed, the product ions are accelerated by an electric field and deflected by a magnetic field. Since the ions are separated according to their mass-to-charge ratio, only the desired ions are detected at the end of the process. The detection occurs, in this way, in proportion to their abundance. Finally, a mass spectrum of the molecule is produced. The spectrum provides the relation of ion abundance versus mass-to-charge ratio. Usually, the most intense peak is assigned with the relative abundance of 100% and the abundances of all the other peaks are given their proportional values, as percentages of the base peak. To avoid interferences from any other forms of matter, the ions must be analysed in a vacuum atmosphere [63,64]. Fig. 4 schematizes the working principle of a mass spectrometer. Here, a sample composed of three distinct analytes is injected and, once accelerated by an electric field, the analytes suffer different deflections when exposed to a magnetic field, allowing their detection and characterization, as addressed.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of a generic measurement with Mass Spectrometry (MS).

Ion mobility spectrometry

When compared with the MS, ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) is a more recent technology but with equally proven results in the fields of identification and quantification of VOCs. Its high levels of sensitivity and specificity added to its analytical flexibility, almost real-time monitoring and portability make IMS one of the most suitable analytical techniques to be applied in-situ, in clinical contexts and out-of-the-laboratory scenarios [65]. In addition, its detection limits can go as low as ppbv and even pptv, enabling IMS to detect even the analyte with the tiniest concentration of the entire sample [66,67].

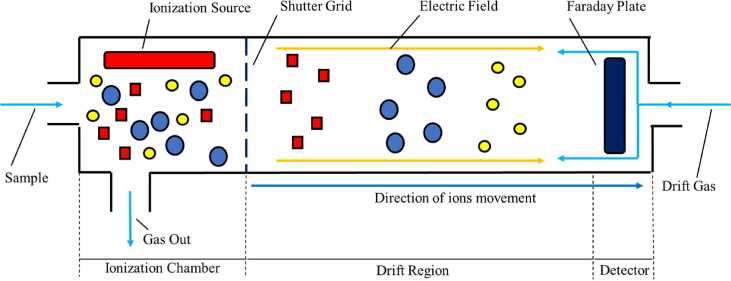

The working principle of an IMS device is rather simple. The spectrometer is equipped with an ionization source responsible for ionizing all the analytes existent in a sample. Once ionized, the ions are exposed to a weak but homogeneous electric field that makes them traverse the entire length of the drift tube at specific velocities. These velocities are ion-specific, which enables that each ion reaches the detector, usually a Faraday plate, at different and, also specific, times. After being detected, the different analytes can be identified accordingly with their characteristic ion mobility constant (calculated from their drift velocities). Fig. 5 illustrates a complete measurement occurring in the interior of an IMS tube. As mentioned, the sample is ionized inside the ionization chamber and then, the product ions are exposed to an electric field that drags them through the entire length of the tube. In the end, the ions are detected by a Faraday plate at their respective drift times [68,69].

Fig. 5.

Schematic of a generic measurement by Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS).

Besides their individual capacities and qualities, none of the mentioned techniques is used independently or, at least, is not ordinary. It is quite common to couple at least two different analytical techniques to obtain a hybrid technique that combines the advantages of both methods in a single device. Marriott et al. (2012), for example, described the utility of coupling GC with GC, creating a multidimensional gas chromatographer (MDGC) [70]. Das et al. (2014), in their turn, used a GC–GC system coupled with a mass spectrometer (GC-GC-MS) to analyse exhaled breath samples and prove the suitability of this technique in the study of the human volatome [71]. The combination between GC and MS is, perhaps, the analytical technique used for the highest number of different scientific subjects. Its vast array of applications ranges from drug detection, fire investigation and environmental analysis, to forensic and medical studies [72]. Several research groups have applied GC–MS for the study of the VOCs exhaled in the breath as is possible to confirm in this review paper.

Regarding the MS limitations on identifying some exact VOCs, IMS and, in specific, the coupling of IMS with GC, has gained relevance in several scientific fields but mainly in clinical contexts [73]. The coupling of these two techniques results in a device with improved selectivity, sensitivity, analytical flexibility, and high capacity for analysing complex matrices [17,67]. The GC-IMS has been largely applied in clinical scenarios and, specifically, in the exhaled breath assessment. Several scientific studies that used GC-IMS are addressed in this review. Besides being an extremely new technology, some research groups are working on coupling MS and IMS in a single device. The coupling of these two spectrometric techniques will result in a device with outstanding levels of sensibility and specificity, and with an enormous capacity for analysing a vast range of analytes in the most diverse and complex scenarios. These characteristics will also make IMS-MS, one of the analytical techniques most suitable for exhaled breath and metabolomics analyses [74,75].

Volatile organic compounds: the role as biomarkers

As addressed, VOCs have gained relevancy as breath biomarkers to diagnose a vast range of pathologies. Respiratory diseases are among the most VOCs-related health conditions. Their potentiality as biomarkers of pathologies like asthma [76], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [77], lung cancer [78], and even COVID-19 [79], have been frequently studied. Hepatic [80], renal [81] and colorectal [82] disorders are equally studied regarding the produced and emitted VOCs. Volatile metabolites related to gastric [83], laryngeal [84], oesophageal [85] and oral [39] cancers are already known as potential biomarkers. Numerous cancers have characteristic VOCs that can act like biomarkers, namely ovarian [86], prostate [42], pancreatic [87], bladder [88], and breast [89] cancer. Characteristic VOCs of pathologies known for their lower complexity or mortality have also been assessed; celiac disease [90], cystic fibrosis [91], muscle dystrophy [92], and diabetes [93] are examples of those health conditions. In addition, several scientific works have been studying the potential of a vast range of pathologies regarding their eventual diagnosis through exhale breath. This recently studied pathologies are Alzheimer's disease [94], Chron's disease [95], epilepsy [96], multiple sclerosis [97], obesity [98], sepsis [99], and thyroid cancer [100], among others. As proved, the applicability of VOCs as biomarkers is wide, contemporary, and promising.

In accordance with the main goals of the present work, one intended to review the main research works developed in the field of potential exhaled breath biomarkers in the form of volatile organic compounds. From this research, a total of 16 pathologies are alphabetically addressed regarding their respective breath biomarkers. In addition, a summary table, Table 1, with all the reviewed VOCs related to the addressed pathologies is included in the appendix of the document. The respective bibliographic sources addressed in this table can be consulted elsewhere (https://neomeditec.com/VOCdatabase/).

Conclusions

The characterization of the volatile organic compounds existing in the human exhaled breath has gained relevance for the identification and diagnosis of a vast range of pathologies and health conditions. This work aimed to assess the state of the art regarding the relevancy and current role of the VOCs as breath biomarkers. A total of 16 pathologies and health conditions were considered of special interest for the bibliographic search. All the VOCs identified as potential biomarkers in breath for the diagnosis of a specific pathology were gathered in an overall database that matches these analytes with the diseases and with the respective bibliographic source. An online database, which the authors intend to keep updated and can be accessed through the link https://neomeditec.com/VOCdatabase/, was exclusively developed to share with the academia an open source tool to consult all this gathered information and divulge new findings in the future.

Considering all the works reviewed in this work, it is important to notice that pretty much all the addressed studies were developed around biological samples collected from human cohorts. Most of the studies compared their findings considering healthy volunteers and patients suffering from the target disease. As addressed, for the detection and identification of the breath biomarkers, most of the authors employed sensor arrays-based electronic noses or spectrometric techniques. More than a couple of hundred biomarkers have been reported in the bibliography addressed here.

All the aforementioned facts and the hundreds of reviewed works unequivocally show that the field of VOCs as breath biomarkers has an auspicious future as a non-invasive, painless, rapid and accurate methodology to identify and diagnose a vast range of health conditions.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT - Portugal) for financing the grants UIDB/04559/2020(LIBPhys) and UIDP/04559/2020(LIBPhys), and Volkswagen Autoeuropa for co-financing the grant PD/BDE/150627/2020 from the Doctoral NOVA I4H Program.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Contributor Information

Maria Raposo, Email: mfr@fct.unl.pt.

Valentina Vassilenko, Email: vv@fct.unl.pt.

Appendix.

Table 1.

Summary of all the reviewed breath biomarkers/VOCs related to the addressed pathologies with high potentiality for further developments. An updated version of the VOCs biomarkers database with the respective bibliographic sources can be consulted at: https://neomeditec.com/VOCdatabase/.

| Volatile Organic Compounds as Exhaled Breath Biomarkers |

Pathologies |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | CAS No. | Asthma | Breast Cancer | CKD | CLD | COPD | Colorectal Cancer | Covid-19 | Cystic Fibrosis | Diabetes | Gastric Cancer | Lung Cancer | Malaria | Prostate Cancer | Sleep Apnoea | Squamous Cell Cancer | Tuberculosis |

| A | |||||||||||||||||

| Acetaldehyde | 75-07-0 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Acetic Acid | 64-19-7 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Aceticamide | 60-35-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Acetone | 67-64-1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Acetophenone | 98-86-2 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Acetyl acetate | 108-24-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Acetylpyridine | 1122-62-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Allylmethylsulphide | 10,152-76-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ammonia | 7664-41-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ammonium acetate | 631-61-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Aniline | 62-53-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| (+)-Aromadendrene | 489-39-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| B | |||||||||||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Benzene | 71-43-2 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Benzoic acid | 65-85-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Benzonitrile | 100-47-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Benzothiazole | 95-16-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Bicyclo [4.1.0]hepta-1,3,5-triene | 4646-69-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Biphenyl | 92-52-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,5-Bis-1,1-dimethylethylphenol | 5875-45-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Bis-(3,5,5-trimethylhexyl) phthalate | 14,103-61-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Butanal | 123-72-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Butane | 106-97-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Butanediol | 110-63-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,3-Butanediol | 513-85-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,3-Butanedione | 431-03-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Butanoic acid | 107-92-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Butanol | 71-36-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Butanone | 78-93-3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 2-Butenol | 504-61-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Butoxybutanol | 4161-24-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Butoxyethanol | 111-76-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Butyl Acetate | 123-86-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Butylatedhydroxytoluene | 128-37-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Butyloctanol | 3913-02-8 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 6-t-Butyl-2,2,9,9-tetramethyl-3,5-decadien-7-yne | – | X | |||||||||||||||

| Butyric Acid | 107-92-6 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| C | |||||||||||||||||

| Camphene | 79-92-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Carbon disulphide | 75-15-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Carene | 13,466-78-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| [E]-Cinnamaldehyde | 14,371-10-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Chloroethylester-carbonochloridic acid | 627-11-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Chloroform | 67-66-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Chloropropanoylchloride | 625-36-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cyclohexane | 110-82-7 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Cyclohexanol | 108-93-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cyclohexanone | 108-94-1 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Cyclooctylmethanol | 3637-63-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cyclopentane | 287-92-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cyclopentanone | 120-92-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| o-Cymene | 527-84-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cymol | 99-87-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| D | |||||||||||||||||

| Decanal | 112-31-2 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Decane | 124-18-5 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 1,2-Decanediol | 1119-86-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Decene | 872-05-9 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| E−3-Decen-2-ol | 18,402-84-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Dichlorobenzene | 106-46-7 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Dichloronitromethane | 7119-89-3 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Dihydro-2(3H)-furanone | 96-48-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,4-Dimethylbenzaldehyde | 15,764-16-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,3-Dimethylbenzene | 108-38-3 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Dimethylbenzene | 106-42-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,2-Dimethylbutane | 75-83-2 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2,3-Dimethylbutane | 79-29-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Dimethyl Carbonate | 616-38-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Dimethylcyclohexane | 589-90-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,2-Dimethyldecane | 17,302-37-3 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 3,6-Dimethyldecane | 17,312-53-7 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 3,7-Dimethyldecane | 17,312-54-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Dimethyl disulphide | 624-92-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4,6-Dimethyl-dodecane | 61,141-72-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,4-Dimethylheptane | 2213-23-2 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 2,6-Dimethylheptane | 1072-05-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,3-Dimethylhexane | 584-94-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3,3-Dimethylhexane | 563-16-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,7-Dimethylnaphtalene | 575-37-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4,5-Dimethylnonane | 17,302-23-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6-Dimethyloctane | 2051-30-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,3-Dimethylpentane | 565-59-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,4-Dimethylpentane | 108-08-7 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2,2-Dimethylpropanoic acid | 75-98-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Dimethyl Selenide | 593-79-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6-Dimethylstyrene | 2039-90-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Dimethyl sulphide | 75-18-3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| 3,7-Dimethylundecane | 17,301-29-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4,7-Dimethylundecane | 17,301-32-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 6,10-Dimethyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one | 689-67-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Dioxane | 123-91-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,3-Dioxolan-2-one | 96-49-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,3-Di-ter-butylbenzene | 1014-60-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,5-Ditert-butylcyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | 2460-77-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6-Ditert-butylcyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | 719-22-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Δ-Dodecalactone | 713-95-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Dodecane | 112-40-3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Dodecanoic acid | 143-07-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Dodecanone | 6175-49-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| E | |||||||||||||||||

| Ethanal | 75-07-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethanol | 64-17-5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Ethenesulfonyl chloride | 6608-47-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethenylnaphtalene | 939-27-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethoxyethyl acetate | 111-15-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 141-78-6 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl acrylate | 140-88-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylaniline | 103-69-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylbenzene | 100-41-4 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ethyl butyrate | 105-54-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Ethylcyclohexane | 1678-91-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-Ethyl-3,5-dimethylbenzene | 934-74-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylene | 74-85-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylene Carbonate | 96-49-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylidenecyclopropane | 18,631-83-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethylhexanol | 104-76-7 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| M-Ethylmethylbenzene | 620-14-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 6,2-Ethylmethyldecane | 62,108-21-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 5-Ethyl-2-methylheptane | 13,475-78-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3,4-Ethylmethylhexane | 3074-77-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethyl-4-methylpentanol | 106-67-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Ethyl-1-octyn-3-ol | 5877-42-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethylpentane | 589-34-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Ethylpentane | 617-78-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethylphenol | 90-00-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethyl propanoate | 105-37-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Ethyltoluene | 611-14-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Ethyltoluene | 620-14-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Ethyltoluene | 622-96-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethyl-Tris (Trimethylsilyl)-Silicate | 18,030-67-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ethyl vinyl ketone | 1629-58-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| F | |||||||||||||||||

| Formic acid propylester | 110-74-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Furan | 110-00-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Furfural | 98-01-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| H | |||||||||||||||||

| Heptanal | 111-71-7 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Heptane | 142-82-5 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Heptanoic Acid | 111-14-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Heptanone | 110-43-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Heptanone | 123-19-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Heptene | 592-76-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexadecane | 544-76-3 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Hexamethyldisilane | 1450-14-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexanal | 66-25-1 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Hexane | 110-54-3 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Hexanoic Acid | 142-62-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexanol | 111-27-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Hexanone | 591-78-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Hexanone | 589-38-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexene | 592-41-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexylcyclohexane | 4292-75-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hexylethylphos-phonofluoridate | 135,445-19-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Hexyloctanol | 19,780-79-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hydrogen cyanide | 74-90-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Hydroxy acetaldehyde | 141-46-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone | 513-86-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 4-Hydroxyhexenal | 17,427-21-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Hydroxy-4-methylpentan-2-one | 123-42-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Hydroxy-2,4,4-trimethylpentyl 2-methylpropanoate | 74,367-34-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| I | |||||||||||||||||

| Indole | 120-72-9 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Iodide cycloheptatrienylium | 142,182-71-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| β-Ionone | 14,901-07-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Isobutyl acetate | 110-19-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Isobutyric acid | 79-31-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Isoprene | 78-79-5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Isopropanol | 67-63-0 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Isopropylacetate | 108-21-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Isopropylmyristate | 110-27-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Isopropoxylbutanol | 42,042-71-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-Isopropyl-3-methylbenzene | 535-77-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Isopropyl myristate | 110-27-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| L | |||||||||||||||||

| Limonene | 138-86-3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| (+)-Longifolene | 475-20-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| M | |||||||||||||||||

| Menthol | 89-78-1 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Methane | 74-82-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methane sulfonyl chloride | 124-63-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methanethiol | 74-93-1 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Methanol | 67-56-1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 3-Methoxy-1,2-propanediol | 623-39-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-(3-Methoxypropoxy)propanol | 1589-49-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methyl Acetate | 79-20-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 9-Methylacridine | 611-64-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylacrylic acid | 79-41-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylamine | 74-89-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylbenzene | 108-88-3 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1,2-bis(trimethylsiloxy)-propane | 6651-34-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutanal | 96-17-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methylbutanal | 590-86-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutane | 78-78-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutanoic acid | 116-53-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 3-Methyl-2-butanone | 563-80-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methylbutanonitrile | 625-28-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methyl-3-butenol | 763-32-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methyl butyrate | 623-42-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylcyclohexane | 108-87-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylcyclopentane | 96-37-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methylcyclopentanone | 1757-42-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Methyldodecane | 6117-97-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-(1-Methylethyl)oxetane | 10,317-17-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylene Chloride | 75-09-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Methyl-2-heptanone | 6137-06-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 110-93-0 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methylhexane | 591-76-4 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 3-Methylhexane | 589-34-4 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 5-Methyl-3-hexanone | 623-56-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Methylhexene-1,4-diol | 40,646-08-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylisobutylketone | 108-10-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylisobutyrate | 547-63-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-Methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)cyclohexene | 5989-54-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| (R)-1-Methyl-5-(1-methyl)cyclohexene | 1461-27-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| N-Methyl-2-methylpropylamine | 39,190-66-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | 91-57-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methylnonane | 5911-04-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Methyloctane | 2216-34-4 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylpentane | 107-83-5 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 3-Methylpentane | 96-14-0 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| 4-methyl-2-pentanone | 108-10-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylphenol | 620-17-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropene | 115-11-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylpropylsulphide | 3877-15-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Methylpyridine | 108-99-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| α-Methylstyrene | 98-83-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-(Methylsulphonyl)propane | 1977-37-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran | 96-47-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylthiocyanate | 556-64-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1-(Methylthio)propane | 3877-15-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Methylthiopropene | 10,152-77-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Methylundecane | 1632-70-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-Methylundecane | 2980-69-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| N | |||||||||||||||||

| Naphthalene | 91-20-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 6-Nitro-2-picoline | 18,368-61-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Nonadecane | 629-92-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4,6,9-Nonadecatriene | 874,302-34-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Nonanal | 124-19-6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Nonane | 111-84-2 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Nonanoic Acid | 112-05-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Nonanol | 28,473-21-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Nonanone | 821-55-6 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| (E)-2-Nonene | 6434-78-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| O | |||||||||||||||||

| Octadecane | 593-45-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Octadecyne | 629-89-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Octamethylcyclo-tetrasiloxane | 556-67-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Octanal | 124-13-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Octane | 111-65-9 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Octanoic acid | 124-07-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Octanone | 106-68-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Octenal | 2363-89-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Octene | 111-66-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Octene | 13,389-42-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Octene | 14,919-01-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| P | |||||||||||||||||

| Pentadecane | 629-62-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,2-Pentadiene | 591-95-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,4-Pentadiene | 591-93-5 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2,2,4,6,6-Pentamethylheptane | 13,475-82-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Pentanal | 110-62-3 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Pentane | 109-66-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Pentanoic acid | 109-52-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Pentanol | 71-41-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 3-Pentanol | 584-02-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentanone | 107-87-9 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| 3-Pentanone | 96-22-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentylfuran | 3777-69-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Phenyl acetate | 122-79-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Phenylacetic acid | 103-82-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Phenylbutene | 935-00-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Phenyl-2-propanol | 617-94-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4-(1-Phenyl-2-propenyloxy)-benzaldehyde | 447,428-96-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Phenol | 108-95-2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| α-Pinene | 80-56-8 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| β-Pinene | 127-91-3 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Pivalic acid | 75-98-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propanal | 123-38-6 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Propane | 74-98-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,2-Propanediol | 57-55-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,3-Propanediol | 504-63-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propanoic Acid | 79-09-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propanol | 71-23-8 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 2-Propenal | 107-02-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propene | 115-07-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Propenenitrile | 107-13-1 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2-Propenoic acid | 79-10-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propylcyclohexane | 1678-92-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Propyl propionate | 106-36-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1H-Pyrazole-4-carbonitrile | 31,108-57-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2-Pyridinecarbonitrile | 100-70-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1H-Pyrrole-3-carbonitrile | 7126-38-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Pyrrolidine | 123-75-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| S | |||||||||||||||||

| Silicon tetrafluoride | 7783-61-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Styrene | 100-42-5 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| T | |||||||||||||||||

| α-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| γ-Terpinene | 99-85-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Terpineol | 8006-39-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tetrachloroethene | 127-18-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tetradecane | 629-59-4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 9-Tetradecenol | 52,957-16-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,2,3,5-Tetramethylbenzene | 527-53-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,2,4,5-Tetramethylbenzene | 95-93-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tetramethylsilicane | 75-76-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,1,3,3-Tetramethylurea | 632-22-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tolualdehyde | 1334-78-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Toluene | 108-88-3 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Trans-2-dodecenol | 69,064-37-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 4H-1,2,4-Triazol-4-amine | 584-13-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Trichlorethylene | 79-01-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Trichloromethane | 67-66-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tridecane | 629-50-5 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Trifluoroacetic acid | 76-05-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Triglyceride | 32,765-69-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Trimethylamine | 75-50-3 | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 1,2,3-Trimethylbenzene | 526-73-8 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | 95-63-6 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene | 108-67-8 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Trimethyldecane | 98,060-54-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,4,6-Trimethyldecane | 62,108-27-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6,10-Trimethyldodecane | 3891-98-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6,11-Trimethyldodecane | 31,295-56-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2,7,10-Trimethyldodecane | 74,645-98-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,2,4-Trimethylheptane | 14,720-74-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,2,3-Trimethylhexane | 16,747-25-4 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 2,3,5-Trimethylhexane | 1069-53-0 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 4,6,8-Trimethylnonene | 54,410-98-9 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,2,6-Trimethyloctane | 62,016-28-8 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,6,6-Trimethyloctane | 54,166-32-4 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,3,6-Trimethyloctane | 62,016-33-5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 2,4,4-Trimethylpentene | 107-39-1 | X | |||||||||||||||

| 1,3,5-Tri-tert-butylbenzene | 1460-02-2 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tolualdehyde | 1334-78-7 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Toluene | 108-88-3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| U | |||||||||||||||||

| 2-Undecanal | 53,448-07-0 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Undecane | 1120-21-4 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| V | |||||||||||||||||

| Vinylpyrazine | 4177-16-6 | X | |||||||||||||||

| X | |||||||||||||||||

| m-Xylene | 108-38-3 | X | |||||||||||||||

| o-Xylene | 95-47-6 | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| p-Xylene | 106-42-3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

References

- 1.Zhou J., Huang Z.A., Kumar U., Chen D.D.Y. Review of recent developments in determining volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath as biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis. Anal Chim Acta. 2017;996:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher M., Wysocki C.J., Leyden J.J., Spielman A.I., Sun X., Preti G. Analyses of volatile organic compounds from human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(4):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bax C., Lotesoriere B.J., Sironi S., Capelli L. Review and comparison of cancer biomarker trends in urine as a basis for new diagnostic pathways. Cancers. 2019;11(9):1244. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez-Calvo E., Wicaksono A.N., Canet E., Daulton E., Ens W., Hoeller U., et al. The measurement of volatile organic compounds in faeces of piglets as a tool to assess gastrointestinal functionality. Biosyst Eng. 2013;184:122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassilenko V., Silva M., Alves R., O’Neill J. Proceedings of the international conference on biomedical electronics and devices - BIODEVICES, Barcelona, Spain. 2013. Instrumental tools for express analysis of lacrimal fluids. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W., Zou X., Ding Y., Zhang J., Zheng L., Zuo H., et al. Rapid screen for ventilator associated pneumonia using exhaled volatile organic compounds. Talanta. 2023;253 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge D., Zou X., Chu Y., Zhou J., Xu W., Liu Y., et al. Analysis of volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath after radiotherapy. J Zhejiang Univ - Sci B. 2022;23(2):153–157. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2100447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EU Directive 2004/42/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on the limitation of emissions of volatile organic compounds due to the use of organic solvents in certain paints and varnishes and vehicle refinishing products. Off J Eur Union. 2004;L143:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.EPA . United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2021. https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/technical-overview-volatile-organic-compounds; (Indoor air quality (IAQ) - technical overview of volatile organic compounds). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruice P.Y. 8th ed. United States of America: Pearson Education; New York: 2016. Organic chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey F.A., Giuliano R.M. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; New York, United States of America: 2017. Organic chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomons T.W.G., Fryhle C.B. 12th ed. United States of America: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 2009. Organic chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolkoff P. Volatile organic compounds - sources, measurements, emissions and the impact on indoor air quality. Int J Indoor Air Qual Clim. 1995;5(3):5–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koppmann R. 1st ed. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2007. Volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montero-Montoya R., López-Vargas R., Arellano-Aguilar O. Volatile organic compounds in air: sources, distribution, exposure and associated illness in children. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(2):225–238. doi: 10.29024/aogh.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Śmiełowska M., Marć M., Zabiegala B. Indoor air quality in public utility environments - a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(12):11166–11176. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8567-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moura P.C., Vassilenko V., Fernandes J.M., Santos P.H. IFIP advances in information and communication technology. Caparica; Portugal: 2020. Indoor and outdoor air profiling with GC-IMS. Advanced doctoral conference on computing, electrical and industrial systems - DoCEIS 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moura P.C., Vassilenko V. Gas Chromatography - ion Mobility Spectrometry as a tool for quick detection of hazardous volatile organic compounds in indoor and ambient air: a university campus case study. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 2022;28(5-6):113–126. doi: 10.1177/14690667221130170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filipiak W., Mochalski P., Filipiak A., Ager C., Cumeras R., Davis C.E., et al. A compendium of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by human cell lines. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23(20):2112–2131. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160510122913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costello B.L., Amann A., Al-Kateb H., Flynn C., Filipiak W., Khalid T., et al. A review of the volatiles from the healthy human body. J Breath Res. 2014;8(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/8/1/014001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim K.H., Jahan S.A., Kabir E. A review of breath analysis for diagnostic of human health. Trends Anal Chem. 2012;33:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mochalski P., King J., Klieber M., Unterkofler K., Hinterhuber H., Baumann M., et al. Blood and breath levels of selected volatile organic compounds in healthy volunteers. Analyst. 2013;138(7):2134–2145. doi: 10.1039/c3an36756h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amann A., Costello B.L., Miekisch W., Schubert J., Buszewski B., Pleil J., et al. The human volatilome: volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath, skin emanations, urine, feces and saliva. J Breath Res. 2014;8(3) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/8/3/034001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pleil J.D., Stiegel M.A., Risby T.H. Clinical breath analysis: discriminating between human endogenous compounds and exogenous (environmental) chemical confounders. J Breath Res. 2013;7(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/017107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarbach C., Stevens P., Whiting J., Puget P., Humbert M., Cohen-Kaminsky S., et al. Evidence of endogenous volatile organic compounds as biomarkers of diseases in alveolar breath. Ann Pharm Fr. 2013;71(4):203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt F.M., Vaittinen O., Metsälä M., Lehto M., Forsblom C., Groop P.H., et al. Ammonia in breath and emitted from skin. J Breath Res. 2013;7(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/017109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bessonneau V., Mosqueron L., Berrubé A., Mukensturm G., Buffet-Bataillon S., Gangneux J.P., et al. VOC contamination in hospital, from stationary sampling of a large panel of compounds, in view of healthcare workers and patients exposure assessment. PLoS One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnanthigo Y., Anttalainen O., Safaei Z., Sillanpää M. Sniff-testing for indoor air contaminants from new buildings environment detecting by aspiration-type ion mobility spectrometry. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2016;19:15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallart-Mateu D., Armenta S., Guardia M. Indoor and outdoor determination of pesticides in air by ion mobility spectrometry. Talanta. 2016;161:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts W. Air pollution and skin disorders. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2021;7(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim E.H., Kim S., Lee J.H., Kim J., Han Y., Kim Y.M., et al. Indoor air pollution aggravates symptoms of atopic dermatitis in children. PLoS One. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Idagarra M.A., Guerrero J.S., Mosle S.G., Miralles F., Galor A., Kumar N. Relationships between short-term exposure to an indoor environment and dry eye (DE) symptoms. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1316. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Berkel J.J.B.N., Dallinga J.W., Möller G.M., Godschalk R.W.L., Moonen E.J., Wouters E.F.M., et al. A profile of volatile organic compounds in breath discriminates COPD patients from controls. Respir Med. 2010;104(4):557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasasti C.I., Haryanto B., Latif M.T. Association of VOCs, PM2.5 and household environmental exposure with children’s respiratory allergies. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2021;14:1279–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rufo J.C., Madureira J., Fernandes E.O., Moreira A. Volatile organic compounds in asthma diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy: Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;71(2):175–188. doi: 10.1111/all.12793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wickliffe J.K., Stock T.H., Howard J.L., Frahm E., Simon-Friedt B.R., Montgomery K., et al. Increased long-term health risks attributable to select volatile organic compounds in residential indoor air in southeast Louisiana. Sci Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78756-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warden H., Richardson H., Richardson L., Siemiatycki J., Ho V. Associations between occupational exposure to benzene, toluene and xylene and risk of lung cancer in Montréal. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(10):696–702. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanc-Lapierre A., Sauvé J.F., Parent M.E. Occupational exposure to benzene, toluene, xylene and styrene and risk of prostate cancer in a population-based study. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(8):562–572. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira J.A., Porto-Figueira P., Taware R., Sukul P., Rapole S., Câmara J.S. Unravelling the potential of salivary volatile metabolites in oral diseases. A Review. Molecules. 2020;25(13):3098. doi: 10.3390/molecules25133098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mochalski P., Wiesenhofer H., Allers M., Zimmermann S., Guntner A.T., Pineau N.J., et al. Monitoring of selected skin- and breath-borne volatile organic compounds emitted from the human body using gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) J Chromatogr. 2018;1076:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boer N.K.H., Meij T.G.J., Oort F.A., Larbi I.B., Mulder C.J.J., Bodegraven A.A., et al. The scent of colorectal cancer: detection by volatile organic compound analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1085–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa B.R.B. Martinis BS Analysis of urinary VOCs using mass spectrometric methods to diagnose cancer: a review. Clin Mass Spectrom. 2020;18:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.clinms.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strimbu K., Tavel J.A. What are Biomarkers? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(6):463–466. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833ed177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lock E.A., Bonventre J.V. Biomarkers in translation; pas, present and future. Toxicology. 2008;245(3):163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Gutiérrez M.S., Navarrete F., Sala F., Gasparyan A., Austrich-Olivares A., Manzanares J. Biomarkers in phychiatry: concept, definition, types and relevance to the clinical reality. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:432. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cervellieri S., Lippolis V., Mancini E., Pascale M., Logrieco A.F., Girolamo A. Mass spectrometry-based electronic nose to authenticate 100% Italian durum wheat pasta and characterization of volatile compounds. Food Chem. 2022;383 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strani L., D’Alessandro A., Ballestrieri D., Durante C., Cocchi M. Fast GC E-nose and chemometrics for the rapid assessment of basil aroma. Chemosensors. 2022;10(3):105. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Binson V.A., Subramoniam M., Mathew L. Discriminationof COPD and lung cancer from controls through breath analysis using a self-developed e-nose. J Breath Res. 2021;15(4) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ac1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boeker P. On ‘electronic nose’ methodology. Sens Actuators, B. 2014;204:2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dragonieri S., Pennazza G., Carratu P., Resta O. Electronic nose technology in respiratory diseases. Lung. 2017;195(2):157–165. doi: 10.1007/s00408-017-9987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Binson V.A., Subramoniam M., Sunny Y., Mathew L. Prediction of pulmonary diseases with electronic nose using SVM and XGBoost. IEEE Sensor J. 2021;21(18):20886–20895. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Machado R.F., Laskowski D., Deffenderfer O., Burch T., Zheng S., Mazzone P.J., et al. Detection of lung cancer by sensor array analyses of exhaled breath. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(11):1286–1291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1184OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moura P.C., Pivetta T.P., Vassilenko V., Ribeiro P.A., Raposo M. Graphene oxide thin films for detection and quantification of industrially relevant alcohols and acetic acid. Sensors. 2023;23(1):462. doi: 10.3390/s23010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdullah A.H., Adom A.H., Shakaff A.Y., Ahmad M.N., Saad M.A., Tan E.S., et al. Electronic nose system for ganoderma detection. Sens Lett. 2011;9(1):353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binson V.A., Subramoniam M., Mathew L. Detection of COPD and Lung Cancer with electronic nose using ensemble learning methods. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;523:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Binson V.A., Subramoniam M. Design and development of an e-nose system for the diagnosis of pulmonary diseases. Acta Bioeng Biomech. 2021;23(1):35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNair H.M., Miller J.M. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 2009. Basic gas chromatography. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poole C. Elsevier, Inc.; Waltham, MA, USA: 2012. Gas chromatography. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartle K.D., Myers P. History of gas chromatography. Trends Anal Chem. 2002;21(9-10):547–557. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dettmer-Wilde K., Engewald W. 1st ed. Springer; London, United Kingdom: 2014. Pratical gas chromatography: a comprehensive reference. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glish G.L., Wachet R.W. The basics of mass spectrometry in the twenty-first century. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(2):140–150. doi: 10.1038/nrd1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gross J.H. 3rd ed. Springer Nature; Cham, Switzerland: 2017. Mass spectrometry. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watson J.T., Sparkman O.D. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Sussex, United Kingdom: 2007. Introduction to mass spectrometry. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmann E., Stroobant V. 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Sussex, United Kingdom: 2007. Mass spectrometry. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moura P.C., Vassilenko V., Ribeiro P.A. Ion mobility spectrometry towards environmental volatile organic compounds identification and quantification: a comparative overview over infrared spectroscopy. Emiss Control Sci Technol. 2023;9:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hill H.H., Siems W.F., Louis R.H.S., McMinn D.G. Ion mobility spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1990;62(23):1201A. doi: 10.1021/ac00222a001. 9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanu A.B., Hill H.H. Ion mobility spectrometry detection for gas chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1177(1):12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eiceman G.A., Karpas Z., Hill H.H. 3rd ed. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton, United States of America: 2014. Ion mobility spectrometry. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borsdorf H., Eiceman G.C. Ion mobility spectrometry: principles and applications. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2006;41(4):323–375. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marriott P.J., Chin S.T., Maikhunthod B., Schmarr H.G., Bieri S. Multidimensional gas chromatography. Trends Anal Chem. 2012;34:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Das M.K., Bishwal S.C., Das A., Dabral D., Varshney A., Badireddy V.K., et al. Investigation of gender-specific exhaled breath volatome in human by GCxGC-TOF-MS. Anal Chem. 2014;86(2):1229–1237. doi: 10.1021/ac403541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hübschmann H.J. 3rd ed. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.; Weinheim, Germany: 2015. Handbook of GC-MS: fundamentals and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moura P.C., Vassilenko V. Contemporary ion mobility spectrometry applications and future trends towards environmental, health and food research: a review. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2023;486 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss F., Schaefer C., Ruzsanyi V., Märk T., Eiceman G., Mayhew C.A., et al. High Kinetic Energy Ion Mobility Spectrometry - mass Spectrometry investigations of four inhalation anaesthetics: isoflurane, enflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2022;475 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Allers M., Kirk A.T., Roßbitzky N., Erdogdu D., Hillen R., Wissdorf W., et al. Analyzing positive reactant ions in high kinetic energy ion mobility spectrometry (KiKE-IMS) by HiKE-IMS-MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2020;31(4):812–821. doi: 10.1021/jasms.9b00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Narendra D., Blixt J., Hanania N.A. Immunological biomarkers in severe asthma. Semin Immunol. 2019;46 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaw J.G., Vaughan A., Dent A.G., O’Hare P., Goh F., Bowman R.V., et al. Biomarkers of progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(11):1532–1547. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.11.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gasparri R., Romano R., Sedda G., Borri A., Petrella F., Galetta D., et al. Diagnostic biomarkers for lung cancer prevention. J Breath Res. 2018;12(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa9386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruszkiewicz D.M., Sanders D., O’Brien R., Hempel F., Reed M.J., Riepe A.C., et al. Diagnosis of COVID-19 by analysis of breath with gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry - a feasibility study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stavropoulos G., Munster K., Ferrandino G., Sauca M., Ponsioen C., Schooten F.J., et al. Liver impairment - the potential application of volatile organic compounds in hepatology. Metabolites. 2021;11(9):618. doi: 10.3390/metabo11090618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gao Q., Lee W.Y. Urinary metabolites for urological cancer detection: a review on the application of volatile organic compounds for cancers. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2019;7(4):232–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oakley-Girvan I., Davis S.W. Breath based volatile organic compounds in the detection of breast, lung, and colorectal cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Biomarkers. 2017;21(1):29–39. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Catalin D.A., Vasile B.D., Alina D. Diagnostic application of volatile organic compounds as potential biomarkers for detecting digestive neoplasia: a systematic review. Diagnostics. 2021;11(12):2317. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11122317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.García R.A., Morales V., Martín S., Vilches E., Toledano A. Volatile organic compounds analysis in breath air in healthy volunteers and patients suffering epidermoid laryngeal carcinomas. Chromatographia. 2014;77:501–509. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yazbeck R., Jaenisch S.E., Watson D.I. From blood to breath: new horizons for esophageal cancer biomarkers. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(46):10077–10083. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amal H., Shi D.Y., Ionescu R., Zhang W., Hua Q.L., Pan Y.Y., et al. Assessment of ovarian cancer conditions from exhaled breath. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(6):E614–E622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Daulton E., Wicaksono A.N., Tiele A., Kocher H.M., Debernardi S., Crnogorac-Jurcevic T., et al. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for the non-invasive detection of pancreatic cancer from urine. Talanta. 2021;221 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cauchi M., Weber C.M., Bolt B.J., Spratt P.B., Bessant C., Turner D.C., et al. Evaluation of gas chromatography mass spectrometry and pattern recognition for the identification of bladder cancer from urine headspace. Anal Methods. 2016;8(20):4037. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li J., Peng Y., Duan Y. Diagnosis of breast cancer based on breath analysis: an emerging method. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;87(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hryniuk A., Ross B.M. A preliminary investigation of exhaled breath from patients with celiac disease using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016;19(1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Buszewski B., Grzywinski D., Ligor T., Stacewicz T., Bielecki Z., Wojtas J. Detection of volatile organic compounds as biomarkers in breath analysis by different analytical techniques. Bioanalysis. 2013;5(18):2287–2306. doi: 10.4155/bio.13.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.King J., Mochalski P., Unterkofler K., Teschl G., Klieber M., Stein M., et al. Breath isoprene: muscle dystrophy patients support the concept of a pool of isoprene in the periphery of the human body. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423(3):526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Daneshkhah A., Siegel A.P., Agarwal M. In: Wound healing, tissue repair, and regeneration diabetes. Bagchi D., Das A., Roy S., editors. Academic Press; New York, United States of America: 2020. Volatile organic compounds: potential biomarkers for improved diagnosis and monitoring of diabetic wounds; pp. 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazzatenta A., Pokorski M., Sartucci F., Domenici L., Giulio C.D. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) fingerprint of Alzheimer’s disease. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;209:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dryahina K., Smith D., Bortlík M., Machková N., Lukás M., Spanel P. Pentane and other volatile organic compounds, including carboxylic acids, in the exhaled breath of patients with Chron’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Breath Res. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa8468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dartel D., Schelhaas H.J., Colon A.J., Kho K.H., Vos C.C. Breath analysis in detecting epilepsy. J Breath Res. 2020;14(3) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ab6f14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Broza Y.Y., Har-Shai L., Jeries R., Cancilla J.C., Glass-Marmor L., Lejbkowicz I., et al. Exhaled breath markers for nonimaging and noninvasive measures for detection of multiple sclerosis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8(11):2402–2413. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raman M., Ahmed I., Gillevet P.M., Probert C.S., Ractliffe N.M., Smith S., et al. Fecal microbiome and volatile organic compound metabolome in obese humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Berkhout D.L.C., Keulen B.J., Niemarkt H.J., Bessem J.R., Boode W.P., Cossey V., et al. Late-onset sepsis in preterm infants can Be detected preclinically by fecal volatile organic compound analysis: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(1):70–77. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bartolazzi A., Santonico M., Pennazza G., Martinelli E., Paolesse R., D’Amico A., et al. A sensor array and GC study about VOCs and cancer cells. Sensor Actuator B Chem. 2010;146(2):483–488. [Google Scholar]