This cross-sectional study examined acute mental health care use (emergency department), boarding, and subsequent inpatient care during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Points

Question

How did utilization of acute mental health care change during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic for youth aged 5 to 17 years?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study comparing pandemic year 2 with a baseline year, the fraction of youth with mental health emergency department visits increased 7%, the percentage of emergency department visits that resulted in inpatient psychiatric admission increased 8%, and the mean length of inpatient psychiatric stay increased 4%. Prolonged boarding before inpatient stays increased 76%; all were statistically significant.

Meaning

Interventions are needed to increase inpatient child psychiatry capacity and reduce strain on emergency departments.

Abstract

Importance

Understanding how children’s utilization of acute mental health care changed during the COVID-19 pandemic is critical for directing resources.

Objective

To examine youth acute mental health care use (emergency department [ED], boarding, and subsequent inpatient care) during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional analysis of national, deidentified commercial health insurance claims of youth mental health ED and hospital care took place between March 2019 and February 2022. Among 4.1 million commercial insurance enrollees aged 5 to 17 years, 17 614 and 16 815 youth had at least 1 mental health ED visit in the baseline year (March 2019-February 2020) and pandemic year 2 (March 2021-February 2022), respectively.

Exposure

The COVID-19 pandemic.

Main outcomes and measures

The relative change from baseline to pandemic year 2 was determined in (1) fraction of youth with 1 or more mental health ED visits; (2) percentage of mental health ED visits resulting in inpatient psychiatry admission; (3) mean length of inpatient psychiatric stay following ED visit; and (4) frequency of prolonged boarding (≥2 midnights) in the ED or a medical unit before admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Results

Of 4.1 million enrollees, 51% were males and 41% were aged 13 to 17 years (vs 5-12 years) with 88 665 mental health ED visits. Comparing baseline to pandemic year 2, there was a 6.7% increase in youth with any mental health ED visits (95% CI, 4.7%-8.8%). Among adolescent females, there was a larger increase (22.1%; 95% CI, 19.2%-24.9%). The fraction of ED visits that resulted in a psychiatric admission increased by 8.4% (95% CI, 5.5%-11.2%). Mean length of inpatient psychiatric stay increased 3.8% (95% CI, 1.8%-5.7%). The fraction of episodes with prolonged boarding increased 76.4% (95% CI, 71.0%-81.0%).

Conclusions and relevance

Into the second year of the pandemic, mental health ED visits increased notably among adolescent females, and there was an increase in prolonged boarding of youth awaiting inpatient psychiatric care. Interventions are needed to increase inpatient child psychiatry capacity and reduce strain on the acute mental health care system.

Introduction

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, youth emergency department (ED) use for mental health problems was increasing, and boarding (waiting in an ED or medical inpatient unit) before inpatient psychiatric care was common.1,2,3 The pandemic exacerbated stressors among youth, including social isolation, school disruptions, and parental unemployment,4 and rates of depression and anxiety have doubled since the start of the pandemic.5 In 2021, 20% of high school students seriously considered suicide, and 9% attempted suicide.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association declared a national emergency in children’s mental health.7 The US Surgeon General has called for a “swift and coordinated response to this crisis.”8

EDs and inpatient psychiatric units provide care for youth in crisis. However, there are limited data on how ED and inpatient use for mental health has changed in the context of this children’s mental health emergency. Research from single hospital systems shows an initial drop in ED visits followed by a return to or increase above prepandemic levels.9,10,11,12,13 One tertiary children’s hospital reported that the median inpatient psychiatric length of stay increased by 3.4 days.11 Over three-quarters of pediatric hospitalists reported an increase in the frequency and duration of boarding.14

We extend this work to quantify national trends in mental health ED use, inpatient length of stay, and boarding among commercially insured youth into the second year of the pandemic.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional study used deidentified health insurance claims data from March 2019 to February 2022 for members of commercial health plans spanning all 50 states (OptumLabs Data Warehouse).15 In the US, 62% of youth 18 years and younger have commercial insurance16; those who do are more likely to be Asian or White and have higher family income than youth with public insurance.17 These data include all care paid for by the health plan, including ED, hospital, and outpatient visits, and have been used in many prior analyses to describe care patterns in the US.18,19,20,21 We included youth aged 5 to 17 years enrolled in both medical and behavioral health coverage in a given month. To maximize representativeness of our sample, we did not require continuous enrollment in the plan for the full study period. On average, our sample included 2.2 million youth per month. This study was deemed exempt by the Harvard Institutional Review Board and follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.22

Outcomes

First, we identified youth with an ED visit using the following codes: revenue codes (0450-0459), Current Procedural Terminology codes (90500, 90505, 90510, 90515, 90517, 90520, 90530, 90540, 90550, 90560, 90570, 90580, 99281-5, G0383-4), or place of service (23). Mental health–related ED visits were defined as ED visits with a primary diagnosis of a mental health condition on the first ED claim (diagnoses listed in eMethods in Supplement 1). We categorized diagnoses as (1) depression; (2) suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or intentional self-injury; (3) bipolar, schizophrenia, or related disorder; (4) anxiety disorder; (5) adjustment or trauma disorder; (6) conduct or impulse control disorder; (7) attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; (8) autism spectrum disorder (ASD); (9) eating disorder; or (10) other. ED visits with a primary diagnosis of substance use disorder (SUD) were not included.

Second, we identified mental health ED visits resulting in inpatient psychiatric stays: hospitalizations with inpatient psychiatry revenue codes (0114, 0116, 0124, 0126, 0134, 0136, 0144, 0146, 0154, 0156, 0204) and a primary mental health diagnosis. The ED visit and inpatient psychiatric stays were linked if they were on consecutive days or with a 1-day gap between the ED claim and the inpatient psychiatry stay claims. This allowed us to follow up youth transferred from an ED in one hospital to an inpatient psychiatric stay in another, which is common in psychiatry.23

Third, we captured length of inpatient psychiatric stay (reported as the number of midnights postadmission) for psychiatric unit admissions that started in the ED.

Fourth, when a mental health ED visit resulted in admission to inpatient psychiatry, we identified prolonged boarding where youth waited for 2 or more midnights before admission.24 Since claims data only include date, not time of arrival or discharge, boarding time was calculated as the date of psychiatric inpatient care minus the date for the ED visit. Boarding time included time in an ED or a nonpsychiatric medical inpatient unit.

Characteristics of Study Population

Individual-level age and biological sex were provided in enrollment data. We stratified by ages 5 to 12 years and 13 to 17 years, as inpatient beds are often divided by age group and the impact of the pandemic could vary by age group.12 Given the data do not include self-reported race, ethnicity, or family income, we stratified youth by county-level percentage of individuals who were Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity and median household income (divided into quartiles) using 2018 US census data.25 Rurality was defined at the county level using the rural-urban commuting area classifications of rural and small towns.26,27

Prior research suggests that youth with ASD28,29 or SUD30,31 may have longer boarding times. To test this, we identified youth with co-occurring ASD or SUD based on diagnosis codes in the ED or inpatient claims (see the eMethods in Supplement 1 for codes). We restricted to diagnoses given within the acute care episode to limit possible bias from less care access for diagnosing ASD32 or SUD during the pandemic.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate changes over the COVID-19 pandemic, we used 3 time periods: baseline (March 2019 to February 2020), pandemic year 1 (March 2020 to February 2021), and pandemic year 2 (March 2021 to February 2022). Because mental health ED use varies widely by season,33,34 we plotted our 4 outcomes by month for each year of the study period.

For each outcome, we measured relative change from baseline to pandemic year 1 and baseline to pandemic year 2, overall and stratified by sex, age group, rural vs nonrural, county not White (Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity) percentage, and county income. We also assessed changes across the 3 years in the fraction of youth with at least 1 ED visit for each diagnostic group, stratified by sex. To understand whether youth had received care prior to the ED visit, we captured what fraction of ED visits were preceded by an outpatient mental health visit in the 30 days prior.

Confidence intervals for differences between years were calculated using a linear regression with standard errors clustered at the individual level. All statistical tests were 2-sided with a P value less than .05 considered significant. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Our sample of 4.1 million youth was 51% male, and 41% were aged 13 to 17 years. The steps in creating our cohort and exclusion criteria are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1. Youth in our cohort lived in counties with higher income and more White residents compared with national averages (Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1).25 The fraction of our study sample insured for all 12 months in each of the 3 study years was stable (64.7%, 68.0%, and 64.8% at baseline, pandemic year 1, and pandemic year 2, respectively).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Populationa.

| Characteristic | No. (%)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All enrollees, millions | Enrollees with ≥1 mental health emergency department visit | |||||

| Baseline year | Pandemic year 1 | Pandemic year 2 | Baseline year | Pandemic year 1 | Pandemic year 2 | |

| Total, No. | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 17 614 | 13 608 | 16 815 |

| Documented sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.5 (51) | 1.4 (51) | 1.4 (51) | 7895 (45) | 5196 (38) | 6333 (38) |

| Female | 1.5 (49) | 1.4 (49) | 1.3 (49) | 9719 (55) | 8412 (62) | 10 482 (62) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 5-12 | 1.8 (60) | 1.7 (59) | 1.6 (59) | 4483 (25) | 3109 (23) | 3722 (22) |

| 13-17 | 1.2 (40) | 1.1 (41) | 1.1 (41) | 13 131 (75) | 10 499 (78) | 13 093 (78) |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Nonrural | 2.9 (96) | 2.7 (96) | 2.6 (96) | 16 813 (95) | 12 947 (95) | 16 111 (96) |

| Rural | 0.1 (4) | 0.1 (4) | 0.1 (4) | 801 (5) | 661 (5) | 704 (4) |

| County quartile: income | ||||||

| Highest | 1.0 (35) | 1.0 (34) | 0.9 (34) | 6024 (34) | 4613 (34) | 5831 (35) |

| 50th-75th Percentile | 0.8 (26) | 0.7 (26) | 0.7 (26) | 4543 (26) | 3452 (25) | 4299 (26) |

| 25th-50th Percentile | 0.7 (25) | 0.7 (25) | 0.7 (25) | 4372 (25) | 3519 (26) | 4298 (26) |

| Lowest | 0.5 (15) | 0.4 (15) | 0.4 (15) | 2675 (15) | 2024 (15) | 2387 (14) |

| County quartile: % not Whitec | ||||||

| Highest | 0.6 (20) | 0.5 (20) | 0.5 (19) | 2510 (14) | 1941 (14) | 2477 (15) |

| 50th-75th Percentile | 0.9 (30) | 0.8 (29) | 0.8 (29) | 4741 (27) | 3762 (28) | 4639 (28) |

| 25th-50th Percentile | 0.8 (27) | 0.8 (27) | 0.7 (27) | 5215 (30) | 3901 (29) | 4872 (29) |

| Lowest | 0.7 (24) | 0.7 (24) | 0.7 (24) | 5148 (29) | 4004 (29) | 4827 (29) |

Study population includes youth aged 5 to 17 years enrolled in medical and behavioral health coverage from a large national insurer. Rurality is defined by the rural-urban commuting area classification of rural or small town, assessed at the county level. Income quartile and percent non-White (Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity) quartile are based on 2018 US census estimates of median household income at the county level. Comparison between study sample and US population is available in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Approximately 5.4% of youth in the US live in rural areas.27

Baseline year indicates March 2019 to February 2020; pandemic year 1, March 2020 to February 2021; and pandemic year 2, March 2021 to February 2022.

Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity.

Mental Health ED Use

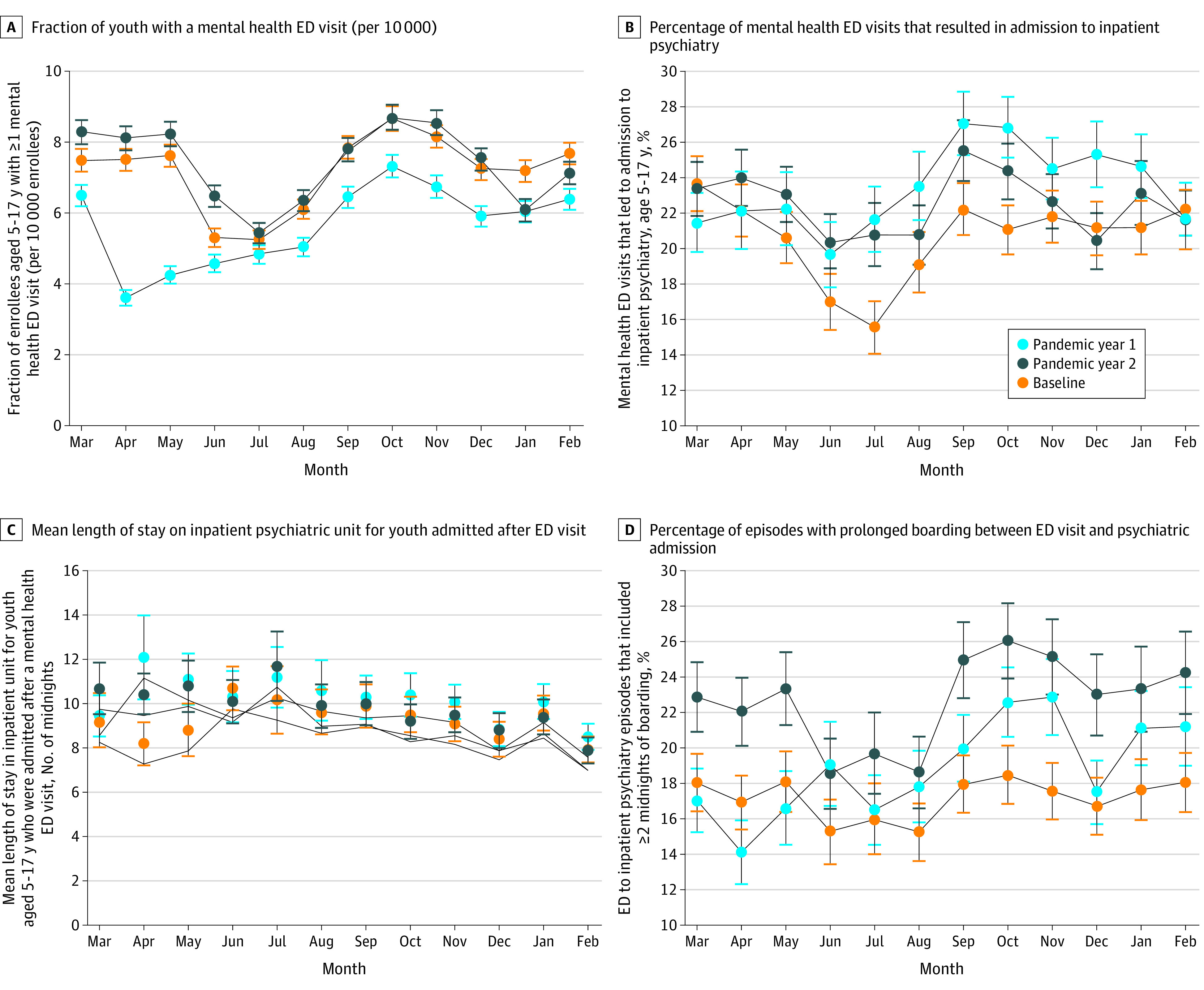

We identified 88 665 youth mental health ED visits. Compared with the baseline year, the fraction of youth with at least 1 mental health ED visit decreased 17.3% (95% CI, −19.6% to −15.1%; from 59 to 49 per 10 000) in pandemic year 1 but increased 6.7% (95% CI, 4.7%-8.8%; from 59 to 63 per 10 000) in year 2 (Figure 1A and Figure 2). The relative percentage of youth with 1 vs multiple ED visits in a year was similar over time (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Changes in Fraction of Commercially Insured Youth With Mental Health Emergency Department (ED) Visits, Likelihood of Admission, Psychiatric Length of Stay, and Likelihood of Prolonged Boarding, March 2019 to February 2022.

Prolonged boarding was defined as 2 or more midnights. Baseline year is March 2019 to February 2020; pandemic year 1, March 2020 to February 2021; and pandemic year 2, March 2021 to February 2022.

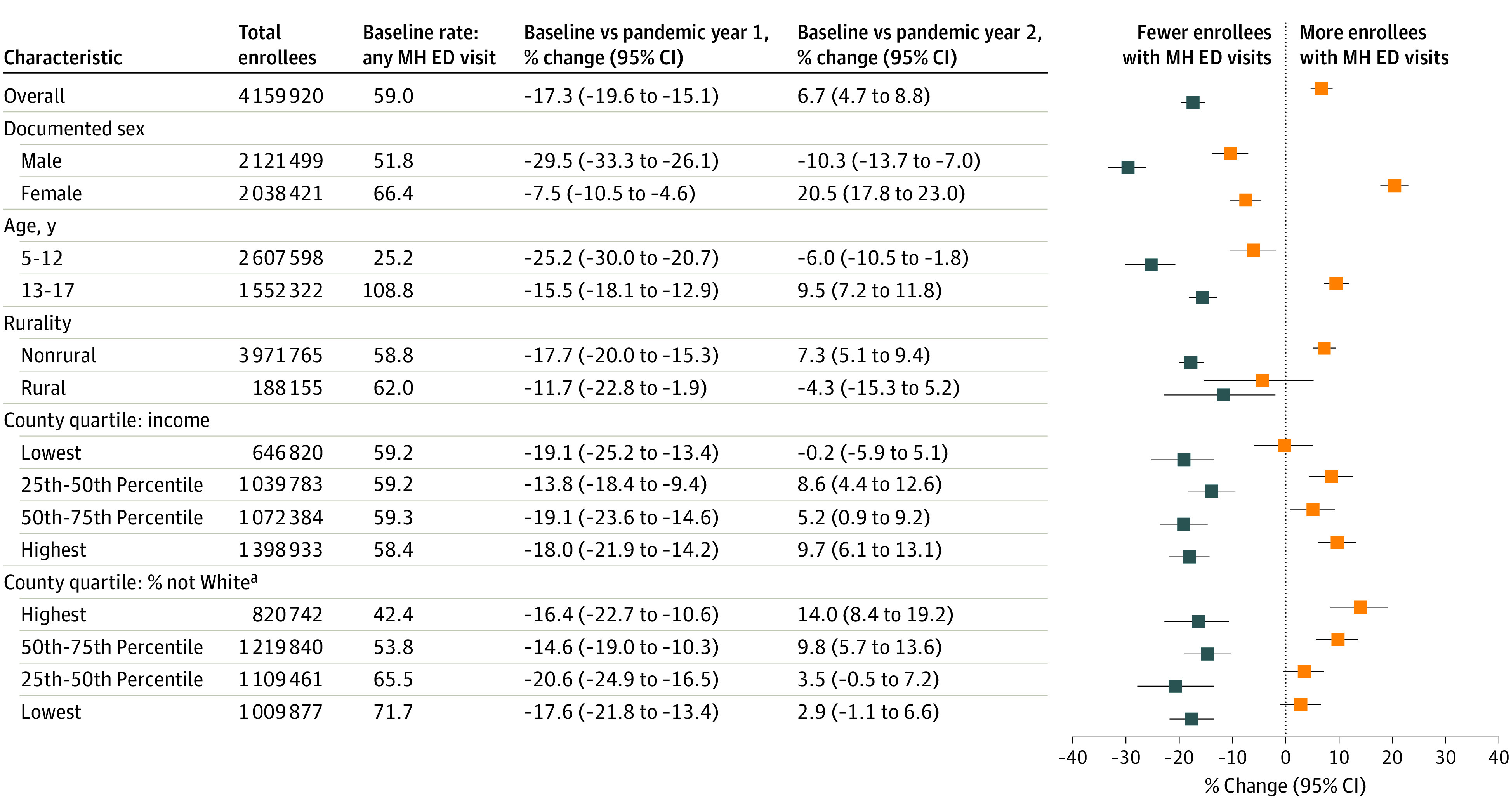

Figure 2. Changes in the Fraction of Youth With 1 or More Mental Health (MH) Emergency Department (ED) Visit (per 10 000 Youth), by Demographic Group.

Fraction of enrollees per 10 000 with 1 or more MH ED visit in the baseline year (March 2019 to February 2020) and change in that fraction from baseline to pandemic year 1 (March 2020 to February 2021) and pandemic year 2 (March 2021 to February 2022). This figure includes youth aged 5 to 17 years enrolled in health insurance through a large national commercial insurer. Confidence intervals were calculated using clustered standard errors at the individual level. MH ED visits were identified by a primary MH diagnosis on the first ED claim. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes are available in the eMethods in Supplement 1. Blue indicates change from baseline to pandemic year 1, and orange indicates change from baseline to pandemic year 2.

aAsian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity.

Changes in the fraction of youth having a mental health ED visit from baseline to pandemic year 2 varied by age and sex: the fraction of females aged 13 to 17 years with visits increased 22.1% (95% CI, 19.2%-24.9%), the fraction for males aged 5 to 12 decreased 15.0% (95% CI, −21.2% to −9.2%), and the fraction for males aged 13 to 17 years decreased 9.0% (95% CI, −13.2% to −5.1%).

Changes in fraction of youth having a mental health ED from baseline to pandemic year 2 also varied by diagnosis and sex (Table 2). Among females, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or self-injury increased 43.6% (95% CI, 39.4%-47.5%; 19 to 28 per 10 000), and eating disorder increased by 120.4% (95% CI, 116.1%-123.6%; 2 to 4 per 10 000). Among males, ED visits across all diagnostic groups decreased or stayed the same except for a statistically nonsignificant 15.7% increase for eating disorder (95% CI, −31.0% to 42.8%). The fraction of youth with an ED visit for conduct or impulse control disorders decreased 30.0% (95% CI, −42.4% to −19.2%) for males and 19.9% (95% CI, −38.1% to −5.1%) for females.

Table 2. Changes in the Fraction of Youth With 1 or More Mental Health (MH) Emergency Department (ED) Visit (per 10 000 Youth), by Diagnostic Group and Sexa,b.

| Characteristic | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth with MH ED visit per 10 000: baseline year | % Change (95% CI) | Youth with MH ED visit per 10 000: baseline year | % Change (95% CI) | |||

| Baseline to pandemic year 1 | Baseline to pandemic year 2 | Baseline to pandemic year 1 | Baseline to pandemic year 2 | |||

| Depressive disorder | 12.7 | −31 (−39 to −25)c | −20 (−27 to −13)c | 22.7 | −8 (−13 to −3)c | 16 (11 to 20)c |

| Suicidal ideation/attempt, self-injury | 11.5 | −28 (−35 to −20)c | 3 (−4 to 10) | 19.4 | −6 (−12 to −1)c | 44 (39 to 48)c |

| Bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder | 1.6 | −22 (−45 to −5)c | −20 (−42 to −2)c | 1.6 | −11 (−33 to 6) | −4 (−26 to 12) |

| Anxiety disorder | 6.6 | −24 (−35 to −15)c | −8 (−18 to 1) | 12.1 | −17 (−24 to −10)c | 6 (−1 to 12) |

| Adjustment disorder, trauma-related disorder | 4.3 | −43 (−56 to −31)c | −19 (−32 to −8)c | 5.7 | −20 (−32 to −10)c | 1 (−9 to 11) |

| Conduct disorder, impulse control disorder | 5.0 | −41 (−53 to −30)c | −30 (−42 to −19)c | 2.4 | −29 (−47 to −14)c | −20 (−38 to −5)c |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 6.1 | −31 (−42 to −21)c | 0 (−10 to 9) | 2.5 | −7 (−24 to 7) | 7 (−9 to 20) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 3.9 | −20 (−33 to −8)c | −6 (−19 to 5) | 1.0 | −9 (−38 to 11) | 10 (−16 to 29) |

| Eating disorder | 0.4 | −8 (−58 to 23) | 16 (−31 to 43) | 1.9 | 72 (61 to 81)c | 120 (116 to 124)c |

| Other | 5.7 | −32 (−43 to −22)c | −19 (−30 to −9)c | 5.2 | −8 (−19 to 2) | 12 (1 to 21)c |

| Total enrollees, million | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

Fraction of youth aged 5 to 17 years with at least 1 ED visit with a primary mental health International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis on the first claim for the ED visit. Percent change and 95% CIs were calculated using linear regression. Enrollees may count for multiple categories if they have ED visits with different categories of primary diagnoses in 1 year. Diagnostic category other includes personality disorders, gender dysphoria, sexual disorders, tic and movement disorders, and unspecified mental disorders. The code list is available in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Baseline year indicates March 2019 to February 2020; pandemic year 1, March 2020 to February 2021; and pandemic year 2, March 2021 to February 2022.

Indicates change in rate from baseline is significant with P < .05.

In the baseline year, the fraction of youth with a mental health ED visit was lower in counties with more residents who were Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity and similar across county income quartiles (Figure 2). From baseline to pandemic year 2, this fraction increased more among enrollees from counties with more residents who were Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity.

In the baseline year, 78.1% of mental health ED visits were preceded by an outpatient visit with a primary mental health diagnosis within the prior 30 days. This decreased to 76.3% in pandemic year 1 and 72.2% in pandemic year 2 (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Likelihood of Admission After an ED Visit

The percent of mental health ED visits that resulted in an inpatient psychiatry admission was 20.9% in the baseline year and increased 13.1% (95% CI, 10.1%-16.1%) from baseline to pandemic year 1 and 8.4% (95% CI, 5.5%-11.2%) from baseline to pandemic year 2 (Figure 1B and eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Depression was the only diagnostic group with a statistically significant increase in likelihood of admission in pandemic year 2 relative to baseline (14.0% [95% CI, 9.4%-18.2%]). In the baseline year, females were more likely than males to be admitted (26.1% vs 15.9%), and this difference grew during the pandemic (change baseline to year 2, female percentage increased 6.8% [95% CI, 3.3%-10.2%]; male percentage decreased 0.3% [95% CI, −5.8 to 4.6%]) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

Length of Inpatient Psychiatric Stay

The mean (SD) length of inpatient psychiatric stay following mental health ED visits was 9.2 (10.3) midnights in the baseline year (Figure 1C). Mean length of stay was 10.6% longer (95% CI, 6.6%-14.3%) from baseline to pandemic year 1 and 3.8% longer (95% CI, 1.8%-5.7%) from baseline to pandemic year 2. The only diagnostic group with a statistically significant change in inpatient length of stay from the baseline year to pandemic year 2 was suicidal ideation/suicide attempt/self-harm, with a 5.4% increase (95% CI, 2.6%-8.1%). Females had a longer mean (SD) length of stay in the baseline year (9.4 [10.5] vs 8.8 [9.8] midnight); changes in mean length of stay were similar for males and females (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

Boarding

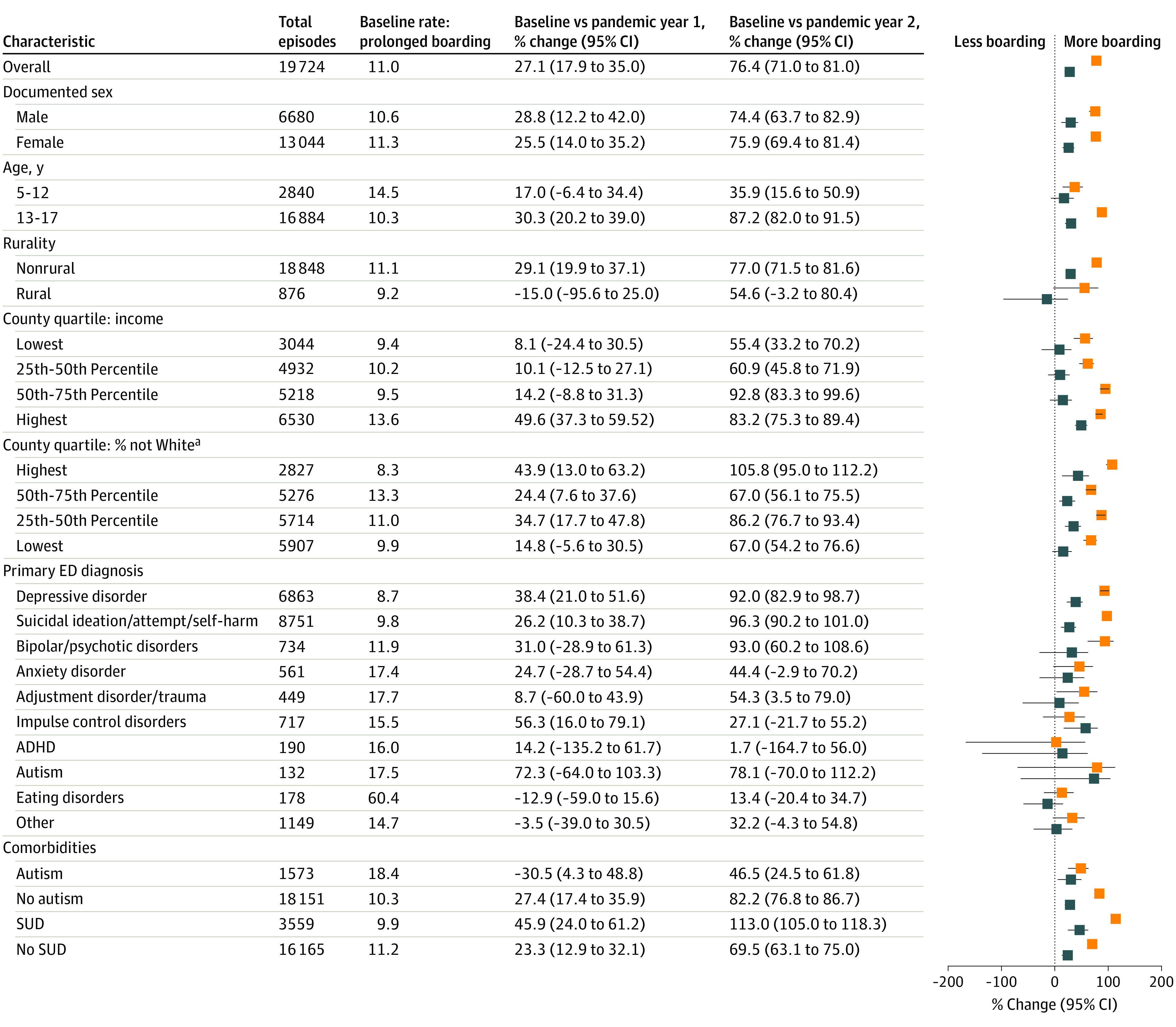

In the baseline year, 11.0% of ED visits that resulted in admission to inpatient psychiatry included prolonged boarding (≥2 midnights). Boarding increased consistently over the pandemic (Figure 1D). Compared with baseline, prolonged boarding increased by 27.1% (95% CI, 17.9%-35.0%) from baseline to pandemic year 1 and 76.4% (95% CI, 71.0%-81.0%) from baseline to pandemic year 2. In pandemic year 2, prolonged boarding increased more for age 13 to 17 years (87.2% [95% CI, 82.0%-91.5%]) than for age 5 to 12 years (35.9% [95% CI, 15.6%-50.9%]). Changes in prolonged boarding were not significantly different between males and females. The increase in prolonged boarding was most pronounced for those in counties above the median income and in counties with more residents who were Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Changes in Percentage of Episodes With Prolonged Boarding (≥2 Midnights) Before Admission to Inpatient Psychiatry.

Percentage of youth aged 5 to 17 years who waited greater than or equal to 2 midnights between an emergency department (ED) visit and admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit – baseline year rate (March 2019-February 2020) is shown, with percent change from baseline year to pandemic year 1 and baseline to pandemic year 2. Co-occurring conditions are defined by the presence of any claim with that International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis anywhere in the acute care episode, including individuals with a primary ED diagnosis of autism. Blue indicates change from baseline to pandemic year 1, and orange indicates change from baseline to pandemic year 2. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SUD, substance use disorder.

aAsian, Black/African American, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other race and ethnicity.

At baseline, youth with ASD had higher rates of prolonged boarding (18.4% vs 10.3% for youth without ASD), and this difference widened by pandemic year 2 (27.0% boarding rate for youth with ASD; 18.8% for those without).

Discussion

In the context of a national emergency in children’s mental health, we observe a 7% increase in the fraction of youth with any mental health ED visits from baseline to pandemic year 2. Among adolescent females, there was a notable 22% increase. Into pandemic year 2, the percentage of mental health ED visits that resulted in a psychiatric admission increased by 8%, and there was a striking 76% increase in prolonged boarding.

The fraction of youth with a mental health ED visit was lower during the entire pandemic year 1. This is consistent with the larger decline in all ED visits due to fear of going to the hospital in the early phase of the pandemic35 but contrasts with the experience in single hospital systems and tertiary children’s hospitals where visits returned to baseline and even increased.10,11,13 This difference may be due to our national sample and inclusion of community hospitals. Community hospitals account for the majority of pediatric ED visits36,37 and may have experienced different trends than tertiary hospitals due to a shift from community hospital to tertiary hospital EDs. The percentage of youth who had an outpatient visit with a mental health diagnosis in the 30 days preceding a mental health ED visit decreased from 78.7% in the baseline year to 72.7% in pandemic year 2, suggesting that in pandemic year 2 fewer youth were connected with the health care system prior to an ED visit.

We observed very different trends in ED visits among adolescent females vs males. By pandemic year 2, the fraction of adolescent females who had a mental health ED visit increased 22% while decreasing substantially among adolescent males. This contrast is consistent with prior literature showing adolescent females have been more negatively impacted by the pandemic than males.38,39 Multiple factors likely contribute to females’ increase in mental distress40 including higher pandemic-related stress,4,39,41 more pandemic-related disruptions to school, and emotional abuse in the home.40 This may explain why the increase in ED visits for females was primarily driven by suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and self-harm. There was also a doubling in the fraction of adolescent females with an ED visit for an eating disorder. This may be a continuation of a prepandemic trend of worsening eating disorder symptoms.42,43 Some have hypothesized that the worsening of symptoms during the pandemic was due to more screen time and seeing oneself on camera.44,45 However, if this was the mechanism, then we would have expected a reduction in ED visits with a return to in-person learning, which we do not observe.46

Concerns around pediatric inpatient psychiatric bed capacity and ED boarding existed before the pandemic.1,28,47 We found that boarding dramatically worsened in the pandemic with a striking 76% increase by pandemic year 2. During time spent boarding, youth receive little care to facilitate recovery: only 14% of pediatric hospitalists reported that youth boarding at their institutions received medication management and 18% that they received psychotherapy.14 Parents of boarding youth frequently likened the environment to incarceration and experienced significant distress during boarding.48 Clinicians often find it morally distressing to care for boarding youth.48

What is driving the increase in boarding is less clear. An increase in need is one factor as we observed an increase in the likelihood of admission among ED visits. The modest increase in inpatient length of stay also decreases the number of available beds. However, the increase in boarding was disproportionately larger than both of these changes. We believe another key factor is restricted inpatient child psychiatry capacity. The number of inpatient child psychiatry beds may be decreased due to staffing challenges,49 pandemic precautions that restricted use of double occupancy rooms,50 and closure or repurposing of inpatient child psychiatry units.51

Several policy interventions could address the changes we observe. Addressing a shortage of clinicians and clinician burnout would allow more inpatient units to run at capacity. Supporting primary care professionals in providing mental health care52,53 and triage of outpatient care for youth who need it most54 could reduce mental health ED visits. Given more children are boarding, a shift in practice may be needed where treatment begins in the ED instead of waiting to admission to the inpatient unit. Brief therapeutic interventions in the ED, possibly via telemedicine, may even reduce the need for admission. Long-term, increased reimbursement rates for mental health care could help incentivize hospitals to prioritize psychiatric inpatient care. In the meantime, it is critical to continue monitoring trends in boarding and to improve the experiences of boarding youth by prioritizing active, collaborative treatment in a healing environment.55,56

Limitations

Our study was limited to commercially insured youth. While we expect our findings are representative of the 62% of youth with commercial insurance,16 they may not generalize to those who are publicly insured or uninsured. Claims data only include date, not time of arrival or discharge. Midnights boarded is a crude measure of time spent boarding. We could not differentiate time spent boarding from time being medically stabilized though we excluded ED visits primarily focused on SUD to minimize the risk that medical stabilization is biasing our findings. As with most commercial claims data sets, we had information on biological sex but did not have individual-level information on gender identity, race, ethnicity, or income. We did not assess boarders who were ultimately discharged without an inpatient psychiatric stay, as we were unable to reliably identify this group in the data. Lastly, while concerns about the youth mental health crisis are international, we do not know if our findings generalize to other countries.

Conclusions

In this study of acute mental health care utilization among commercially insured youth over the first 2 years of the pandemic, mental health ED visits notably increased among adolescent females, and we observed a 76% increase in prolonged boarding of youth awaiting inpatient care. These data can help inform the continuing debate about how to best address the mental health crisis and reduce ED boarding.

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Flow chart of acute mental health care utilization over 2 years of COVID

eFigure 2. Changes in the percentage of mental health ED visits that result in an inpatient psychiatric stay

eFigure 3. Change in mean length of inpatient psychiatric stay following emergency department visit

eTable 1. Characteristics of youth in analyzed commercial claims dataset compared to United States population of youth age 5-17 years

eTable 2. Number of mental health ED visits per youth among youth with at least one mental health ED visit per year

eTable 3. Enrollment and outpatient mental health diagnoses 30 days prior to mental health ED visits

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-030692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalb LG, Stapp EK, Ballard ED, Holingue C, Keefer A, Riley A. Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth and young adults in the US. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20182192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo CB, Bridge JA, Shi J, Ludwig L, Stanley RM. Children’s mental health emergency department visits: 2007-2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20191536. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao Y, Yip PSF, Pathak J, Mann JJ. Association of social determinants of health and vaccinations with child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(6):610-621. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142-1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, et al. Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January-June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71(3):16-21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics . AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

- 8.Murthy VH. Protecting youth mental health. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

- 9.Cloutier RL, Marshaall R. A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:776-777. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibeziako P, Kaufman K, Scheer KN, Sideridis G. Pediatric mental health presentations and boarding: first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(9):751-760. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridout KK, Alavi M, Ridout SJ, et al. Emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(12):1319-1328. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankar LG, Habich M, Rosenman M, Arzu J, Lales G, Hoffmann JA. Mental health emergency department visits by children before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(7):1127-1132. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leyenaar JK, Freyleue SD, Bordogna A, Wong C, Penwill N, Bode R. Frequency and duration of boarding for pediatric mental health conditions at acute care hospitals in the US. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2326-2328. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, Bleicher PA, Crown WH. Optum Labs: building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1187-1194. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch LN. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2021. United States Census Bureau. Published September 2022. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-278.pdf

- 17.Artiga S, Latoya H. Health Coverage by race and ethnicity, 2010-2021. Kaiser Family Foundation/Racial Equity and Health Policy. Published December 20, 2022. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/

- 18.Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Uscher-Pines L, Barnett ML, Riedel L, Mehrotra A. Treatment of opioid use disorder among commercially insured patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2440-2442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):388-391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel SY, McCoy RG, Barnett ML, Shah ND, Mehrotra A. Diabetes care and glycemic control during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(10):1412-1414. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray KN, Wittman SR, Yabes JG, Sabik LM, Hoberman A, Mehrotra A. Telemedicine visits to children during the pandemic: practice-based telemedicine versus telemedicine-only providers. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(2):265-270. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Neil AM, Sadosty AT, Pasupathy KS, Russi C, Lohse CM, Campbell RL. Hours and miles: patient and health system implications of transfer for psychiatric bed capacity. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(6):783-790. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.9.30443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel SY, Huskamp HA, Barnett ML, et al. Association between telepsychiatry capability and treatment of patients with mental illness in the emergency department. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(4):403-410. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Census Bureau . Explore Census Data. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://data.census.gov/

- 26.WWAMI Rural Health Research Center . Rural-urban commuting area code definitions: version 2.0. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-codes.php

- 27.America’s children in brief: key national indicators of well-being, 2020. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac2020/ac_20.pdf

- 28.Brathwaite D, Strain A, Waller AE, Weinberger M, Stearns SC. The effect of increased emergency department demand on throughput times and disposition status for pediatric psychiatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;64:174-183. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wharff EA, Ginnis KB, Ross AM, Blood EA. Predictors of psychiatric boarding in the pediatric emergency department: implications for emergency care. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(6):483-489. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31821d8571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slade EP, Dixon LB, Semmel S. Trends in the duration of emergency department visits, 2001–2006. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(6):483-489. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.9.878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon J, Luck J, Cahn M, Bui L, Govier D. ED boarding of psychiatric patients in Oregon: a report to Oregon Health Authority. College of Public Health and Human Sciences, Oregon State University. Published October 28, 2016. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.mentalhealthportland.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/OHA-Psychiatric-ED-Boarding-Full-Report-Final.pdf

- 32.Miller A, Gold J. Delays for autism diagnosis and treatment grew even longer during the pandemic. Kaiser Health News. Published March 30, 2022. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/delays-for-autism-diagnosis-and-treatment-grew-even-longer-during-the-pandemic/

- 33.Marshall R, Ribbers A, Sheridan D, Johnson KP. Mental health diagnoses and seasonal trends at a pediatric emergency department and hospital, 2015-2019. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(3):199-206. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cushing AM, Liberman DB, Pham PK, et al. Mental health revisits at US pediatric emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(2):168-176. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smulowitz PB, O’Malley AJ, Khidir H, Zaborski L, McWilliams JM, Landon BE. National trends in ED visits, hospital admissions, and mortality for Medicare patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(9):1457-1464. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American College of Emergency Physicians; Pediatric Committee; Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee . Joint policy statement–guidelines for care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1233-1243. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitfill T, Auerbach M, Scherzer DJ, Shi J, Xiang H, Stanley RM. Emergency care for children in the United States: epidemiology and trends over time. J Emerg Med. 2018;55(3):423-434. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zima BT, Edgcomb JB, Rodean J, et al. Use of acute mental health care in U.S. children’s hospitals before and after statewide COVID-19 school closure orders. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(11):1202-1209. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendolia S, Suziedelyte A, Zhu A. Have girls been left behind during the COVID-19 pandemic? Gender differences in pandemic effects on children’s mental wellbeing. Econ Lett. 2022;214:110458. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2022.110458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause KH, Verlenden JV, Szucs LE, et al. Disruptions to school and home life among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January-June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71(3):28-34. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cutler GJ, Bergmann KR, Doupnik SK, et al. Pediatric mental health emergency department visits and access to inpatient care: a crisis worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(6):889-891. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu J, Liu J, Li S, Ma H, Wang Y. Trends in the prevalence and disability-adjusted life years of eating disorders from 1990 to 2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e191. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020001055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1402-1413. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damour L. Eating disorders in teens have ‘exploded’ in the pandemic. The New York Times. Published April 28, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/28/well/family/teens-eating-disorders.html

- 45.Nagata JM, Iyer P, Chu J, et al. Contemporary screen time modalities among children 9-10 years old and binge-eating disorder at one-year follow-up: a prospective cohort study. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(5):887-892. doi: 10.1002/eat.23489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.School pulse panel. Institute of Education Sciences. Accessed January 1, 2023. https://ies.ed.gov/schoolsurvey/spp/

- 47.Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, Shah SB, Schmelzer NA, Worley LLM. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association resource document. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(5):690-695. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.6.42422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarty EJ, Nagarajan MK, Halloran SR, Brady RE, House SA, Leyenaar JK. Healthcare quality during pediatric mental health boarding: a qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2022;17(10):783-792. doi: 10.1002/jhm.12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An acute crisis: how workforce shortages are affecting access & costs. Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://mhalink.informz.net/mhalink/data/images/An%20Acute%20Crisis%20-%20MHA%20Workforce%20Report.pdf

- 50.Bebinger M. No vacancy: how a shortage of mental health beds keeps kids trapped inside ERs. Kaiser Health News. Published June 25, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://khn.org/news/article/children-teens-emergency-room-boarding-mental-health/

- 51.Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, Garfield R, Chidambaram P. Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published May 26, 2021. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/mental-health-and-substance-use-considerations-among-children-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- 52.Hilt RJ, Romaire MA, McDonell MG, et al. The Partnership Access Line: evaluating a child psychiatry consult program in Washington State. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):162-168. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarvet B, Gold J, Bostic JQ, et al. Improving access to mental health care for children: the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1191-1200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Community behavioral health centers. Mass.gov. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.mass.gov/community-behavioral-health-centers#about-

- 55.Kim AK, Vakkalanka JP, Van Heukelom P, Tate J, Lee S. Emergency psychiatric assessment, treatment, and healing (EmPATH) unit decreases hospital admission for patients presenting with suicidal ideation in rural America. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(2):142-149. doi: 10.1111/acem.14374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff JC, Maron M, Chou T, et al. Experiences of child and adolescent psychiatric patients boarding in the emergency department from staff perspectives: patient journey mapping. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2023;50(3):417-426. doi: 10.1007/s10488-022-01249-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Flow chart of acute mental health care utilization over 2 years of COVID

eFigure 2. Changes in the percentage of mental health ED visits that result in an inpatient psychiatric stay

eFigure 3. Change in mean length of inpatient psychiatric stay following emergency department visit

eTable 1. Characteristics of youth in analyzed commercial claims dataset compared to United States population of youth age 5-17 years

eTable 2. Number of mental health ED visits per youth among youth with at least one mental health ED visit per year

eTable 3. Enrollment and outpatient mental health diagnoses 30 days prior to mental health ED visits

Data sharing statement