Abstract

A substantial body of evidence indicates that regular engagement in moderate-intensity physical activity on most days of the week is sufficient for older adults to achieve positive health outcomes. Although there is a growing body of literature that examines the affect of neighborhood environment on physical activity in older adults, the research tends to overlook social aspects that potentially shape the relationship between physical environment and physical activity. This article presents qualitative themes related to the role of the physical and social environments in influencing physical activity among older adults as identified through the photovoice method with sixty-six older adults in eight neighborhoods in metropolitan Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and Greater Portland, Oregon, USA. The photovoice data generated seven themes: being safe and feeling secure, getting there, comfort in movement, diversity of destinations, community-based programs, peer support and intergenerational/volunteer activities. Although the majority of these themes have explicit or implicit physical and social aspects, certain themes are primarily based on physical environmental aspects (e.g., safe and feeling secure, comfort in movement), while a few themes are more oriented to social context (e.g., peer support, intergenerational activity/volunteering). The themes are discussed with a focus on how the neighborhood physical and social environmental aspects interplay to foster or hinder older adults in staying active in both everyday activities and intentional physical activities. Policy implications of the findings are discussed.

Keywords: Neighborhood, Aging, Physical activity, Health behavior, Physical environment, Social factors, Photovoice, Canada, USA

Introduction

A substantial body of evidence indicates that regular engagement in moderate-intensity physical activity on most days of the week is sufficient for older adults to achieve positive health outcomes (Blumenthal & Gullette, 2002; Li et al., 2005). Regular participation in physical activity for leisure, transportation or household activities could prevent, delay, or significantly minimize negative effects associated with chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes) commonly experienced in later life (e.g., Colman & Walker, 2004; Seefeldt, Malina, & Clark, 2002). Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that older adults who engage in regular physical activity benefit from increased psychological wellbeing and various health-related quality of life domains including emotional, cognitive and social functioning (Acree et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2004; White, Wójcicki, & McAuley, 2009).

Physical functioning, mental health, physical activity, social participation, social networks, political and economic structures, and physical environmental factors are interrelated concepts that interface in these dynamics (Oswald et al., 2007; World Health Organization, 2001). The centrality of place or geographical context in the aging process is a key element in understanding issues of physical health and psychological well-being of older adults. The neighborhood environment becomes increasingly salient to older adults who face multiple personal and social changes that often limit daily activities to their immediate or nearby surroundings (Dobson & Gilron, 2009; Glass & Balfour, 2003). The relevance of the socio-physical context as related to health is well-established in the literature (Barrett, 2000; Cummins, Curtis, Diez-Roux, & Macintyre, 2007; Veenstra et al., 2005). Both subjective (perceived neighborhood quality) and objective neighborhood constructs (neighborhood disadvantages and affluence) are associated with residents’ health (Bowling & Stafford, 2007; Weden, Carpiano, & Robert, 2008). Research (see Frank, Engelke, & Schmid, 2003; Pickett & Pearl, 2001; Shaw, 2004) has demonstrated that people, especially older adults (Howden-Chapman, Signal, & Crane, 1999; Phillipson, 2007), living in impoverished neighborhoods with poor infrastructure and support services including lack of access to proper nutrition (e.g., grocery stores carrying nutritious food products) (Black, Carpiano, Fleming, & Lauster, 2011) have lower level of health-related quality of life compared to people who live in more affluent neighborhoods. Furthermore, there is evidence that older adults whose income had declined but who still lived in high status neighborhoods had poorer physical functioning and cognitive ability than those whose incomes had not declined (Deeg & Thomése, 2005). On the other hand, amenities in neighborhood can facilitate older adult residents’ mobility within the neighborhood, enabling them to access services, and provide opportunities to be active and use their neighborhood environments on a regular basis (Chaudhury, Mahmood, Michael, Campo, & Hay, 2012; Chaudhury, Sarte, Michael, Mahmood, McGregor, & Wister, 2011; Phillips, Siu, Yeh, & Cheng, 2005). Access to adequate and affordable public transportation and age-friendly urban design features helps to integrate them into the social fabric of the community and contribute to their physical functioning, mental health and well-being (Saelens, Sallis, & Frank, 2003).

Longstanding relationships with proximate family, friends and neighbors can be fundamental to the continuity of social support. Social support, in turn, serves as a protective health factor (Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert, & Berkman, 2001). This is especially true for those living in areas characterized by intense social deprivation (Scharf, Phillipson, Kingston, & Smith, 2001). Additionally, familiarity and comfort with the local area helps to foster autonomy and a psychological sense of control for older adults and contribute to their mental health (Oswald, Wahl, Martin, & Mollenkopf, 2003; Phillips et al., 2005). Furthermore, neighborhoods differentially affect mental health of residents from different socio-economic status and gender (Burke, O’Campo, Salmon, & Walker, 2009). However, despite this growing body of literature on neighborhood and health connection, there is still a need for a better understanding of attributes of neighborhoods salient to health (Frank et al., 2003; Schaefer-McDaniel, Dunn, Minian, & Katz, 2010).

Physical activity that is accomplished as part of daily life, such as walking for travel or recreation, usually occurs within one’s neighborhood (Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2002; Troped, Saunders, Pate, Reininger, Ureda, & Thompson, 2001) and these habitual forms of physical activities represent key sources of exercise for older adults (Li et al., 2005). In the last ten years, the concept of walkable neighborhoods or walkability has received growing attention in many disciplines, including public health, community planning, urban design, etc., that recognize the potential of modifying the built environment to foster walking behavior. For example, numerous municipalities and regional governments throughout Canada and the United States have engaged in projects, many involving environmental audits, which assess neighborhood design features that can foster increased physical activity in neighborhoods in an attempt to facilitate environmental and policy changes (e.g., City of New Westminster, 2010; Deehr & Shumann, 2009; Halton Region Health Department, 2009). Research evaluating the impact of the neighborhood physical and social environments on the physical activity of older adults is growing, but still limited in number compared to similar research with the general adult population (Yen, Michael, & Perdue, 2009). This emerging research on older adults investigates key features within the neighborhood built environment as it pertains to active living and increasingly, active aging (e.g., Brownson, Hoehner, Day, Forsyth, & Sallis, 2009; Grant, Edwards, Sveistrup, Andrew, & Egan, 2010; King, 2008). At the core of all such work is better understanding of older adults’ needs in terms of the neighborhood built environment and an effective way of understanding of these needs is through active participation of the older adult in the research process and data collection.

The participatory-action research strategy of “photovoice,” which engages study participants to take photographs as a method of documentation and communication of a physical-social phenomenon, is perceived to offer novel insights and convey the ‘feel’ of specific events or locations which is often lost with research methods relying on oral, aural or written data (Rose, 2007). In this study, Photovoice is defined as “a participatory action research (PAR) strategy by which people create and discuss photographs as means of catalyzing personal and community change” (Wang, Yi, Tao, & Carovano, 1998). Photovoice has emerged as a potential tool for collecting and disseminating knowledge in a way that enables local people to get involved in identifying and assessing the strengths and concerns in their community, create dialog, share knowledge and develop a presentation of their lived experiences and priorities (Hergenrather, Rhodes, & Bardhoshi, 2009). Photovoice method is consistent with core community-based participatory research principles with an emphasis “on individual and community strengths, co-learning, capacity building and balancing research and action” (Catalani & Minkler, 2010, p. 425). The process has three main goals: a) to enable people to record and reflect their communities strengths and concerns, b) to promote critical dialog and knowledge about important community issues through large and small group discussion of photographs, and c) to reach policymakers (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Participants are given cameras to record and reflect on the strengths and concerns regarding the topic of interest. Often this is followed by facilitated photo discussion(s) which allows the participants to share, discuss and contextualize the photographs they took and promote critical discussion. The data of photo discussions are analyzed like other qualitative data through coding data, and exploring, formulating and interpreting themes (Hergenrather et al., 2009). Often themes are developed in partnership with the participants, or they are validated by the participants, typically through interactive discussion in a community forum. Photovoice method has been employed by researchers in different disciplines to explore and address a variety of culturally diverse groups and community issues. In a review of literature on photovoice research, Hergenrather et al. (2009) identified 31 studies using photovoice methodology conducted in seven different countries. However, there are very few photovoice studies that focus directly on older adults’ health, neighborhoods or physical activity. LeClarc, Wells, Craig, and Wilson (2002) used photovoice to explore the everyday issues, challenges, struggles and needs of community-dwelling elderly women in the first weeks after hospital discharge. Baker and Wang (2006) employed photovoice to explore the experience of chronic pain in older adults. The experience of pain, a difficult dimension to capture, was explored through photovoice as an alternative method in understanding and describing the pain experience in older adults’ everyday lives. Photovoice method was also explored by Aubeeluck and Buchanan (2006), to capture and describe the experience of the spousal carer for people living with Huntington’s disease by photographing and describing elements of their life in which they felt their quality of life was being enhanced or compromised.

There is a paucity of research on neighborhood-characteristics and physical activity using the photovoice method with older adults. Nowell, Berkowitz, Deacon, and Foster-Fishman (2006) explore the meanings residents ascribe to characteristics of their neighborhoods using the photovoice method with 29 adult and youth residents in seven distressed urban neighborhoods in Battle Creek, Michigan. According to the participants in that study, both positive and negative characteristics of their proximal neighborhood (e.g., parks, walking trails, public spaces, landmarks, as well as, graffiti, boarded up buildings, ill maintained yards and public areas) conveyed cues to residents about their personal histories as members of that community. Additionally, these characteristics defined social norms and behaviors within the community and conveyed cues to residents about who they are and who they might become. Looking specifically at older adults, a study by Lockett, Willis, and Edwards (2005) used the photovoice approach to examine physical environmental factors that influence the walking choices of older adults in three distinct neighborhoods in Ottawa, Canada. The findings indicate that environmental hazards related to traffic, fall risks due to poor maintenance and access barriers are all significant barriers to walking for seniors. Walking was seen to be facilitated by aesthetically pleasing environments, accessible transit systems and convenient, barrier-free routes between destinations. The findings also revealed how simple amenities such as public washrooms and benches can facilitate walking for seniors. The use of photovoice as a method was well received by the participants, indicating a feeling of empowerment and a heightened awareness to avoiding fall hazards in the neighborhood (Lockett et al., 2005). These studies utilize a participatory research method to identify physical environmental features perceived as fostering or hindering walking behavior in adults. However, an understanding of the interrelated effect of neighborhood physical environment and social aspects on physical activity in older adults with a photovoice method remains largely unexplored.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a participatory research process with community-dwelling older adults using photovoice method to identify neighborhood physical environmental features and social aspects that influence physical activity in older adults. The study reported in this article is part of a three-year research project. The first year of the larger study focused on developing a comprehensive neighborhood environmental audit tool for physical activity in older adults by integrating two existing tools, the Irvine Minnesota (IMI) Tool (Day, Boarnet, & Alfonzo, 2005; Day, Boarnet, Alfonzo, & Forsyth, 2005) and the Senior Walking Environmental Audit Tool (SWEAT) (Cunningham, Michael, Farquhar, & Lapidus, 2005; Keast, Carlson, Chapman, & Michael, 2010). The Senior Walking Environmental Audit Tool – Revised (SWEAT-R) (Chaudhury et al, 2011; Michael et al., 2009) was developed and used for environmental audit in eight neighborhoods in Portland and Vancouver. In the second year, issues and concepts related to the role of the physical and social environments in influencing seniors’ physical activity were identified through the photovoice method. The final year involves a cross-sectional survey with a random sample of older adults in the Vancouver and Portland study neighborhoods. This article presents the findings from the photovoice portion of the larger study.

Methods

Thirty-four older adults in four neighborhoods in metropolitan Vancouver, British Columbia and 32 older adults in four neighborhoods in Greater Portland, Oregon participated in this study. The eight neighborhoods were selected earlier in the first year of the larger three-year study with varying levels of residential density in order to pilot test an environmental audit tool. We continued with those eight neighborhoods in the second year’s photovoice method as our research team had established links with community-based seniors’ organizations. Multiple strategies were used to recruit the photovoice study participants. Primary recruitment took place at the local community centers in the eight neighborhoods by posting flyers and by making brief presentations of the study to older adult groups. Other recruitment techniques included contacting churches, community planning tables, advertisements in community newspapers and word-of-mouth. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study were: 65 years of age or over, living in the community, able to communicate and understand basic English, functionally mobile and comfortable walking in neighborhood with or without assistive devices, able to self-report physical and social activity, have no hindrances that would impede the ability to operate a camera, and willing to attend a one half-day training session and one half-day discussion session. The nature of data collection required that the participants are able to move about in their neighborhoods to take photographs of physical and social aspects of the neighborhoods. English-speaking participants were recruited in order that they could follow the photovoice training session, understand and communicate with the research team.

Trained researchers screened potential participants to evaluate whether they met inclusion criteria. Those who met the criteria were invited to consent to take part, while those who did not meet the criteria were informed that they were not eligible for inclusion in the project. In Vancouver, there were two rounds of recruitment, one in fall of 2008 (14 participants) and one in winter/spring of 2009 (20 participants). In Portland, there was one round of recruitment in the winter/spring of 2009 (32 participants). All participants attended one training/information session before the data collection. A catered half-day training/information session was held in each metropolitan area. The half-day session is needed in order to achieve multiple goals. The first part of the session included presentation of an overview of the study, introduction and discussion of the photovoice process and discussion on the ethics and responsibilities of taking photographs in public spaces. A brief questionnaire on self-reported health and physical activity levels was administered. During this initial session, the participatory nature of the photovoice method was emphasized. The training identified three important reasons the method was selected for this project each related to the importance of engaging community members in the research: (a) the method values the knowledge put forth by people as a vital source of expertise; (b) what professionals, researchers, specialists, and outsiders think is important may completely fail to match what the community thinks is important, and (c) the photovoice process turns the camera lens toward the eyes and experiences of people that may not be heard otherwise. In the second part of the session, a professional photographer instructed the study participants on effective photo-taking techniques and allowed them time to practice with a disposable camera.

For the actual photovoice activity, the participants were asked to photograph physical and social aspects of their respective neighborhoods that they perceived as facilitators or barriers to their physical activity behaviors. For the purpose of this study, “physical activity” was defined as to any physical movement or mobility carried out for the purpose of leisure (e.g., walk in the park, dance class, workout at gym) or transportation (e.g., walking/cycling to a destination) in the participant’s neighborhood. Although physical activity also includes activities of daily living (ADLs) in the home, the current definition in this study was based on its focus on activities taking place in the neighborhood environment. A participant package was handed out that included: a 27-exposure disposable camera, a photo-journal to document where each picture was taken and the reason behind taking the picture, general information on the study and photography tips, picture taking consent forms, a postage-paid envelope and instructions. Participants had two weeks to take the pictures and were asked to mail the camera back to the research team when finished. The photographs were developed by the research team and a set of prints was mailed back to the participants with additional instructions. Each participant was asked to select 6–8 photographs from her/his respective set that best reflected the issues he/she was trying to capture and write additional comments or impressions about those selected pictures.

The study participants attended a second half-day catered group discussion session in each metropolitan area. In Vancouver, the discussion session was attended by all 34 participants, and in Portland, all 32 participants attended this session. In the first part of this session, the researchers randomly distributed the participants into multiple small groups, with each group having 4–5 participants. Each participant then discussed her/his 6–8 selected pictures within the small group with a facilitator (researcher/research assistant) who took notes and summarized the group’s findings. In the second half of the session, highlights from the multiple small group discussions were shared with the whole group (32 participants in Portland and 34 participants in Vancouver) and a facilitated discussion was recorded. These sessions were meant to foster critical discussion and reflection regarding issues identified in the photographs, emerging issues and to generate planning and design recommendations on how to overcome the barriers and enhance facilitators of physical activity in the study neighborhoods. Each participant who completed the study up to this point was given a stipend of $100 as honorarium for her/his time and travel expenses to attend the two face-to-face sessions (training and discussion) as required by the study process. We were pleased that all 64 initial participants completed the study by taking photographs in their respective neighborhoods and participating in the subsequent discussion session. Although the number of training and discussion sessions differed in the two regions (4 sessions in Vancouver, and 2 in Portland), all sessions and subsequent two week periods in which the participants took photographs, took place in fall and spring seasons in the Pacific Northwest. These two seasons in this part of North America have similar weather pattern minimizing any weather related variation in the nature of physical activities.

All photographs, photo journals and additional write-ups were then collected, organized and coded by two researchers in each region. The researchers started with a framework of concepts identified from the literature using a deductive analytic strategy called “Successive approximation” (Neuman, 2006). “Successive approximation” is a method of qualitative data analysis in which the researcher repeatedly moves back and forth between the empirical data and abstract concepts or theories (Neuman, p. 469). The concepts, i.e., safety, accessibility, etc, have been previously reported as important issues in the literature on physical environment for walkability. In this study, the concepts are explored and exemplified in a participatory method (photovoice) and potential social aspects of physical activity are identified. We explored areas of congruence and incongruence between cities. We characterized relatively large minorities as representing “most” of the participants. This photovoice data analysis generated several themes which are presented in the results section. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Simon Fraser University Research Ethics Board.

Demographics of participants

All participants filled out a questionnaire asking basic questions on their socio-demographics, general health and physical activity levels (see Table 1). In both cities, the majority of the participants were female. In Portland area, the age ranged from 65 to 92 years old and 62% were in the older age ranges from 75 to 80. In Vancouver area, the majority of the sample was younger with 61% belonging to the lower age ranges of 65–74. The education level in Portland was high, with 75% reported having completed college, university or some graduate school or more, compared to only 27% in Vancouver. In Vancouver, 88% of the participants owned their home, while in Portland there was a more even distribution between renting (47%) and owning (53%) their homes. In both cities, over 90% of the population reported their general health as good to excellent. The vast majority of participants engaged in five or more hours of physical activity per week. In Portland, the top three types of physical activity reported were walking, gardening and gym/strength training, while in Vancouver, these were walking, gardening and group exercises.

Table 1.

Socio-economic status (SES), neighborhoods, health and physical activities of study participants.

| General SES demographics | Portland (n = 32) | Vancouver (n = 34) | Neighborhood and health | Portland (n = 32) | Vancouver (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Neighborhoods | 16 Mount Tabor | 13 S. Surrey or | ||

| Male | 37% (12) | 26% (9) | 9 Lake Oswego | White Rock | |

| Female | 62% (20) | 73% (25) | 6 Milwaukie | 9 Maple Ridge | |

| 1 Clackamas | 7 Vancouver | ||||

| 5 Burnaby | |||||

| Age | Years lived in Neighborhood | ||||

| Age Range | 65–92 | 65–87 | Range | 6 m–80 yrs | 2–54 yrs |

| 65–69 | 25% (8) | 32% (11) | Average | 18 years | 23 yrs |

| 70–74 | 12% (4) | 29% (10) | |||

| 75–79 | 28% (9) | 15% (5) | Tenure | ||

| 80+ | 34% (11) | 12% (4) | Rent | 47% (15) | 9% (3) |

| Not stated | 12% (4) | Own | 53% (17) | 88% (30) | |

| Not stated | 3% (1) | ||||

| Marital Status | General Health | ||||

| Single (never married) | 0% (0) | 3% (1) | Excellent | 19% (6) | 26% (9) |

| Married/Common Law | 44% (14) | 47% (16) | Very Good | 41% (13) | 44% (15) |

| Separated/Divorced | 31% (10) | 12% (4) | Good | 34% (11) | 26% (9) |

| Widowed | 25% (8) | 38% (13) | Fair | 3% (1) | 3% (1) |

| Poor | 0%(0) | 0%(0) | |||

| Not stated | 3% (1) | ||||

| Education | Hours of Activity per week | ||||

| Not stated | 3% (1) | 3% (1) | Not stated | 3% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Grade school | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | None | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| (up to grade 8) | 9% (3) | 29% (10) | Less than 1 h | 0% (0) | 3% (1) |

| High school | 3% (1) | 9% (3) | 1–2 h | 0% (0) | 9% (3) |

| (up to grade 12) | 9% (3) | 32% (11) | 3–4 h | 22% (7) | 24% (8) |

| Technical training cert. | 28% (9) | 15% (5) | 75% (24) | 65% (22) | |

| Some college or univ. | 47% (15) | 12% (4) |

Findings

Seven major themes emerged based on a systematic analysis of the participants’ photographs and the corresponding descriptions of each photograph. The themes are: being safe and feeling secure, getting there, comfort in movement, diversity of destinations, community-based programs, peer support, intergenerational/volunteer activities. Most of the themes have explicit or implicit physical and social aspects. A few themes are primarily based on physical environmental aspects (e.g., being safe and feeling secure, comfort in movement), while others are more socially oriented (e.g., peer support, intergenerational activity/volunteering). The emergent themes and brief descriptions of their physical and social aspects are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Emergent qualitative themes from the photovoice data.

| Photovoice themes | Physical and social aspects |

|---|---|

| Being safe and feeling secure: maintenance, traffic hazards, atmosphere | Primarily related to physical environmental features such narrow sidewalks, obstacles on sidewalks, adequate lighting, etc.; also included perceived social aspects of safety such as poverty, lack of police presence, etc. |

| Getting there: transportation, amenities | Both physical features such as bus shelters, availability of bus routes, location of bus stop, social aspects, such as convenient bus schedule were noted |

| Comfort in movement: convenient features, available amenities | Based on primarily physical environmental features, such as flat, accessible sidewalks, ramps, handrails, presence of benches, etc. |

| Diversity of destinations: recreational, utilitarian | Physical presence of places like grocery, bank, mall, park, farmer’s market etc. were also noted for their value in making social connections |

| Community-based programs: formal programs | Presence of community centers, churches, etc. as settings, along with the availability of exercise classes or social activities that had a physical activity component such as water aerobics, Tai Chi, yoga class, etc. |

| Peer Support: formal and informal, gardening | Primarily related to social aspects, such informal and formal interaction and support through walking groups, community gardens, etc. |

| Intergenerational/Volunteer Activities | |

| reason/motivation to stay active | Primarily related to social aspects, such as volunteering or intergenerational activity at a school, 1library, multicultural events, etc. act as a motivating force to get out and walk or stay active. |

The following section discusses each theme, outlining any differences between the two regions and providing examples of related photographs and quotes.

Being safe and feeling secure

Safety and security was the most photographed and talked about theme in both Vancouver and Portland regions. This theme included both physical environmental features of the streetscape related to physical safety, as well as social perceptions of feeling secure. The importance of a psychological sense of safety and security was as relevant as the concern for physical safety. The constituting issues of this theme included physical environmental aspects, e.g., maintenance, upkeep, traffic hazards; on the other hand, they included psychological perception of the neighborhood atmosphere, e.g., perception of socially inappropriate behaviors. The most commonly photographed issues regarding safety and security were features of the physical environment that were seen as barriers to physical activity. A common barrier reported was uneven sidewalks or damage to the pavement, making it difficult to walk in the neighborhood streets (e.g., Fig. 1). A participant in Portland area referred to this issue as, “Uneven surface with barks from trees, planting encroaching on 10’ wide walkway easement. Gravel would provide more secure footing in the walkway. A sign designating this walkway would encourage more use. As it is now, many potential walkers think this walkway is private property and therefore do not want to use it or feel they are trespassing.” In Portland, a common complaint concerned sidewalks that would abruptly end or that there was no sidewalk at all – forcing people to walk in the street or on rough terrain, often an unsafe walking condition. Other physical features of the environment, such as lack of sidewalk curb cuts, narrow sidewalks or obstacles on sidewalks were described by the participants as unsafe environmental features impacting walking in their neighborhoods. One participant stated, “[The streets near my home have] no sidewalks, no shoulders on one side, poor visibility due to curve. This is my only access to church and a bus stop… I walk here but don’t enjoy it.” Another participant expressed her frustration as, “This street runs in front of the adult community center (senior center) with elderly people who live nearby having to walk in the street as there is sidewalk to nowhere [sidewalk ends abruptly].” On a positive note, the presence of adequate lighting in neighborhoods and recreational areas (e.g., parks and trails) was also found to be a facilitator of physical activity as lighting can increase visibility of the surrounding area, and of oneself by others.

Fig. 1.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Being Safe and Feeling Secure”.

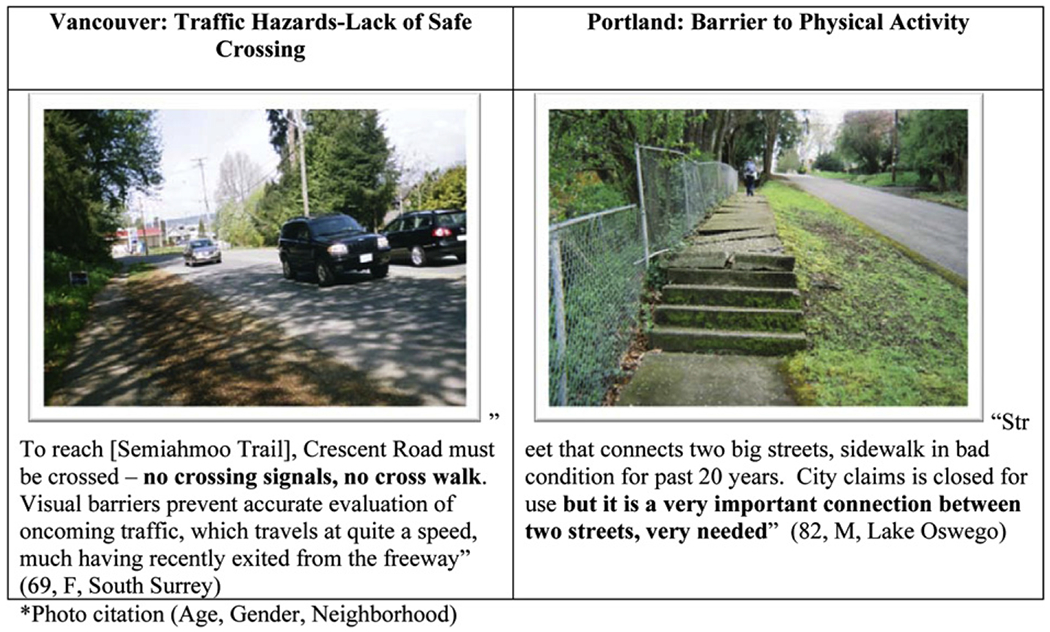

Traffic hazards were highlighted as barriers that deterred participants from walking in their communities. Speeding cars, heavy traffic and drivers not obeying traffic rules (e.g., pedestrian crossing signals) left participants feeling uneasy and unsafe (e.g., Fig. 1). Lack of visibility to oncoming traffic from sidewalks or street crossings was also a concern for many participants in both cities. According to one participant (referring to a highway crossing for pedestrians and bikes at an intersection), “This crossing is notorious in our neighborhood with people – seniors who walk downtown to the bakery or the drug store or whatever. Notorious for near misses of ‘becoming a hood ornament’ bicyclists have to carry their bikes upstairs and across the tracks or catch a bus.” Participants also identified areas in their neighborhood where they would like to see a crosswalk put in for better access to shops and bus stops across the street. While the presence of safe crossing areas was important in both cities, participants in Portland emphasized the need for more convenient crossing especially on busy streets.

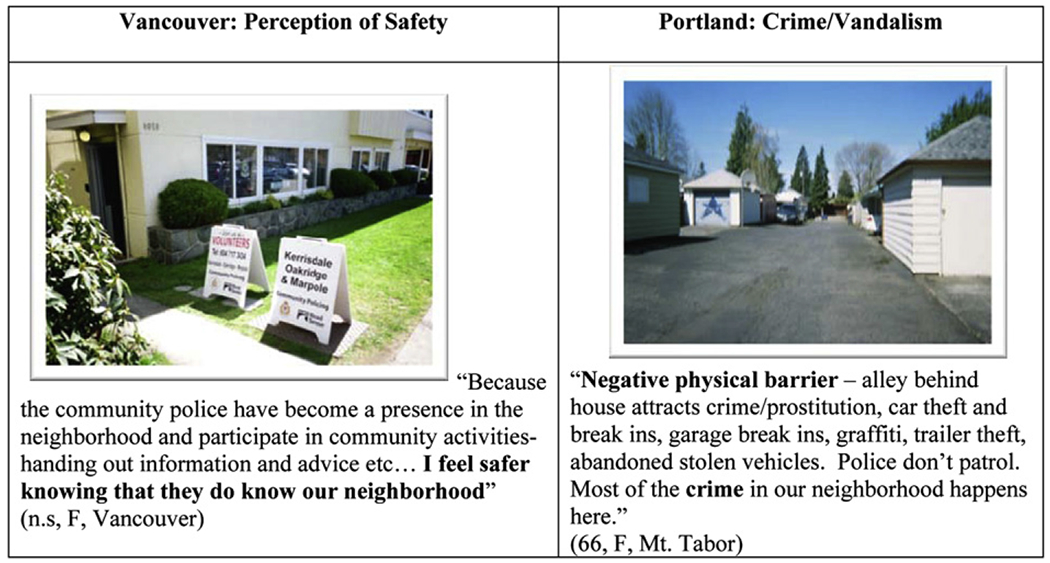

A few participants in both regions mentioned issues that made them feel unsafe in their neighborhoods, such as signs of poverty, drugs, criminal activity, vandalism, or poor housing (e.g., Fig. 2). The perception of an unsafe atmosphere or negative atmosphere in the neighborhood contributed to a sense of vulnerability, which deterred people from being physically active in spaces that they would otherwise enjoy using. One participant from Portland commented, “Neighborhood graffiti – negative social factor, gangs in neighborhood at night.” Another person wrote, “Across from the street where I live – tangents (homeless) live in this area and are seen wheeling the grocery carts loaded with their possessions. I do not feel comfortable walking when they are around. A Vancouver participant noted, “Some problems in area includes poverty, drug and criminal activities and poor housing, etc. Some people do not feel safe or willing to walk through area to get to river.” Participants highlighted the need for well-lit spaces for walking. “Comes to mind, Gertrude Stein’s quip on Los Angeles, ‘There’s no there there’… perhaps a block of ‘x’ street made into a mall with a fountain and benches would be a start… too dark and deserted at night, the city begs for more signs of safe, civil habitation, no place to stroll.” While these issues were common to both regions, participants in Vancouver mentioned that the embedded presence of police in their community made them feel safer. As “police stations” were integrated with retail, services, etc. within the community, the proximity of the police with street life seemed to have contributed to an enhanced sense of security (e.g., Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Being Safe and Feeling Secure”.

Getting there

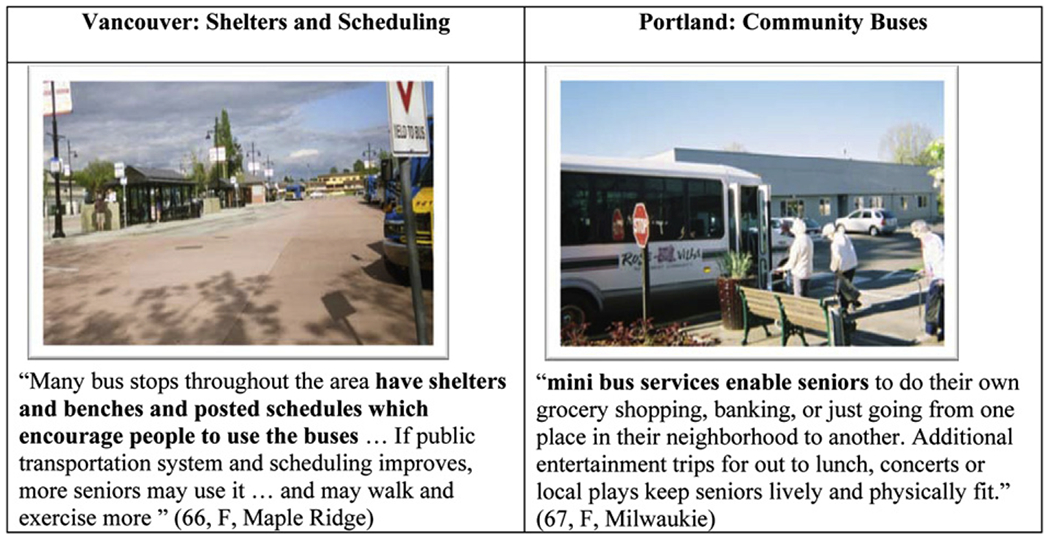

This theme is related to real and perceived barriers to accessing services and amenities in the neighborhoods. For example, the importance of accessible and convenient public transportation was noted in both cities. With regards to public transportation, scheduling and infrastructure emerged as two primary issues. As for scheduling, several participants identified the need for public transportation services outside the peak working hours (e.g., during the day, evenings and weekends) to better meet the needs of older adults who are not in the workforce. In Portland, community buses run by senior centers or senior housing were seen as a facilitator for community outings, shopping and socialization with friends (e.g., Fig. 3). One participant in Portland highlighted this aspect while also describing that the community bus drivers themselves were often older adults, “Mini bus service (for older adults) enable seniors to do their own grocery shopping, banking, or just going from one place in their neighborhood to another. Additional entertainment trips or outing for lunch, concerts or local plays keep seniors lively and physically fit. Some drivers of these vehicles have actually retired and are over the age of 65 years. They do driving for special events to make a little extra spending money.” This is an interesting example of an opportunity for peer interaction for both the older adult passengers of the bus and the bus driver. In a contrasting scenario, most of the participants in Vancouver pointed out the limitations of the city’s bus routes, especially to local parks or trails.

Fig. 3.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Getting There.

In terms of public transportation infrastructure, several environmental features were identified as important to facilitating mobility. The location of bus stops was one such feature; having a bus stop close to home and in close proximity to their destinations (e.g., community center, shopping center) facilitated ease of access to social and/or physical activity that might be happening at the destinations. One Vancouver participant’s comment on the lack of easy access to bus stop highlights this point, “Picture shows the large parking lot area and I attempted to give a view of the distance between stores and services. There is no shuttle and no benches for seniors to rest in-between shops and visits to stores, cafes and cinemas. Seniors who depend on public transport find it difficult to access. Some areas in [neighborhood] do not have any public transportation and some have very limited…. No weekend service and a several hour wait with no bench is not conducive to public usage or an incentive to be more active.” Another participant from Portland commented, “Busy street, fast traffic – no crosswalk to bus stop in either direction and quickest public transit to downtown. A person has to walk four blocks in one direction or three in the other direction to find a crosswalk to get to the bus stop.” Additionally, bus stops with seating areas, shelters and posted schedules were photographed as being influential in engaging in physical activity and accessing local amenities (e.g., Fig. 3). This theme’s illustration of the importance of getting to the service or amenity is an overlooked aspect in planning for programs and services for older adults. The existence of a program/service (e.g., seniors’ program at the community center, adult day center) does not necessarily mean that older adult residents are able to get there in a safe and convenient manner. Essentially, the meaningful success of a senior-oriented program or service is dependent on older adults’ independent access to the site on foot or by safe public transit.

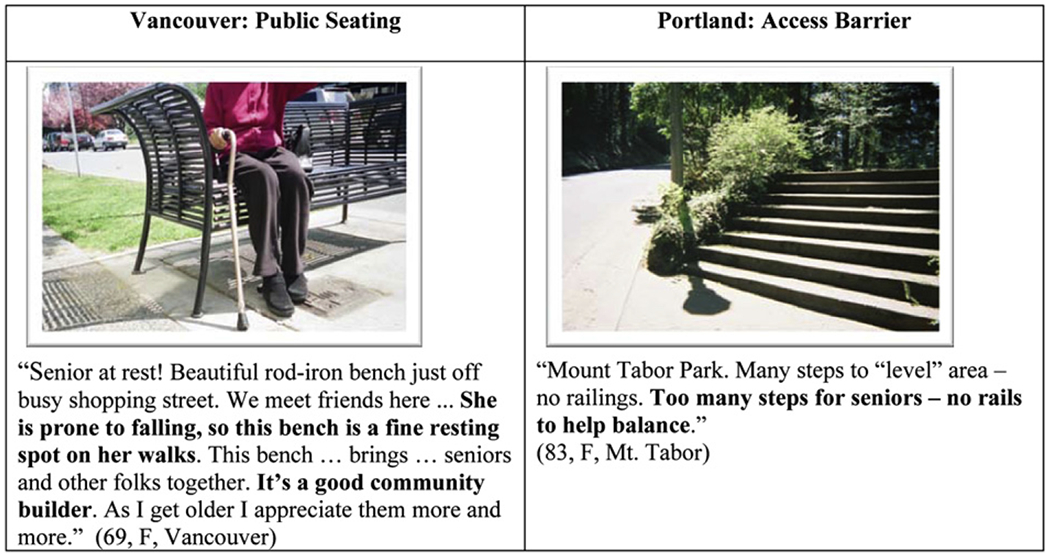

Comfort in movement

This theme encompasses physical environmental features that assist older adults’ needs and preferences when navigating in the neighborhood environment. Presence of convenient features, such as benches, and availability of amenities such as parking areas were subjects of several photographs and descriptions. For example, one participant in Vancouver noted, “Parking is limited especially at peak activity time and it is located at the bottom of the hill area. [Need to] add better public transportation and encourage more people to walk to location and leave their cars at home.” Paved, flat, accessible sidewalks or pathways facilitated walking in neighborhoods and recreational spaces. Additionally, the importance of sidewalks and pathways to be easily accessible and well-maintained for people using assistive devices in order to help them carry out daily activities was highlighted. For instance, one participant mentioned the following about the challenge in getting to the local grocery store, “No way to safely get from sidewalk to store if in wheelchair or disabled. Across the lot [there is] ramp to pharmacy drive-through, but no way to get to it safely.” Presence of benches in parks and walkways was also an important feature which made walking more feasible (e.g., Fig. 4). For areas with steep slopes or stairs, handrails or ramps were described as important features that made it safer for older adults to walk. Various environmental features that might not be generally associated with mobility were identified as helpful for the participants. In both cities, availability of drinking fountains in public spaces was found to be a facilitator of physical activity. In Vancouver, participants expressed the need for senior-friendly print on community signage and access to convenient and clean public bathrooms (e.g., Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Comfort in Movement”.

In Vancouver, specifically in the lower density neighborhoods, lack of parking near recreational and other spaces (e.g., restaurants) was described as a barrier to access and mobility, whereas having low or no cost parking options near community centers and recreational spaces was viewed as a facilitator to physical activity. Participants in both cities also mentioned disruption in access and movement due to ongoing construction in their communities, as these would often block walkways and force individuals to find alternative (often longer) routes or creating unsafe walking conditions.

Diversity of destinations

Many neighborhood destinations were photographed and described by the photovoice participants. Although, these can be broadly grouped into the two categories of recreational and utilitarian, several destinations were considered to have both components. Destinations where community-based programs occurred are discussed in the next theme. Utilitarian type destinations included the grocery store, bank, post office or mall. For many participants, these destinations kept them physically active while doing their errands. The important issue identified here relates to the close proximity of these amenities to their home as a determining factor in encouraging individuals to go out and walk to the particular destination. One participant in Portland noted, “Walking to local mailbox – keeps me active, 5 blocks from home, prefer using this to leaving mail out for postman.” Another in Vancouver stated, “Banks are about 4 blocks away from my neighborhood and it is pleasant to do banking with personnel instead of doing banking on-line from home. You see people there, and when walking to the bank – they are from your neighborhood.” These two quotes clearly reveal that individuals might appreciate taking a walk over 4–5 blocks (i.e., taking approximately 10–15 min) to access simple amenities as an opportunity to get out and be in their neighborhoods.

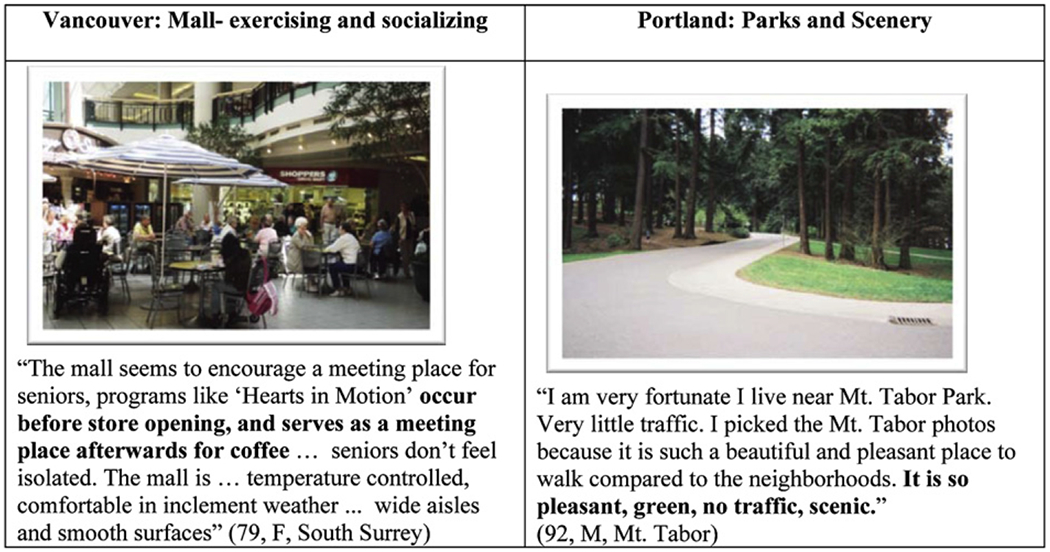

Beyond the utilitarian purposes of going out and walking to a service or amenity, frequenting neighborhood destinations often involved a social component, such as meeting friends for coffee or talking to people along the way. Shopping malls were photographed and described as a destination for both utilitarian and recreational activities, especially in Vancouver (e.g., Fig. 5). The malls were described as easily accessible places to walk as they have wide and smooth walking surfaces, resting places; also, they are temperature controlled and very good meeting places for socialization. Recreational destinations were also often photographed and discussed. In Portland, the most mentioned recreational destination was the community parks and walkways, which were considered as good places to go walking. Several people mentioned parks as destinations not only for the scenic beauty, but also as places for family interaction. One participant in Portland mentioned, “Picnics are for everyone with a chance to entertain the grandkids and walk around to top (sloped area of the park) to see the views.” Another participant, also from Portland observed, “A small beautiful children’s park. Grandma brings the little ones to play while she rests in the shade and watches them happily enjoy their play.”

Fig. 5.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Diversity of Destinations”.

In Vancouver, outdoor walking spaces such as hiking trails, the beach and walkways, were mentioned as recreational destinations. For dog owners, dog-friendly parks were viewed as a positive destination to encourage physical activity. Additionally, in both regions the beautiful scenery of these destinations was pointed out as attractions that get them out and walking. The natural environment, – rivers, trees, flowers, mountains and sculptures in the neighborhoods were also considered as attractive aspects of the environment that encouraged participants to spend time outdoors (e.g., Fig. 5). A Vancouver resident described a local park as “very busy once baseball begins and the pool opens, most enjoyable to watch the games and walk around park…. Plenty of seats placed with good view of duck ponds, very accessible for seniors.” Other recreational destinations included indoor recreational facilities such as gyms, swimming pools, and outdoor facilities including tennis courts and golf courses.

Community events were also described as destinations in the participants’ communities. Many participants talked about going to local farmers markets on the weekends, a place for socialization and community involvement. A Portland resident noted, “Saturday Market (May to October), a very popular location – a place to buy, to meet and to be part of – important to seniors.” In Vancouver, particularly in the lower density areas, participants mentioned many more community events that they enjoyed participating in such as festivals, summer concerts, multicultural events and community celebrations. These latter destinations underscore the salience of social programs and events in drawing older adults out of their home, get to a public destination, and move about as they enjoy the event or gathering.

Community-based programs

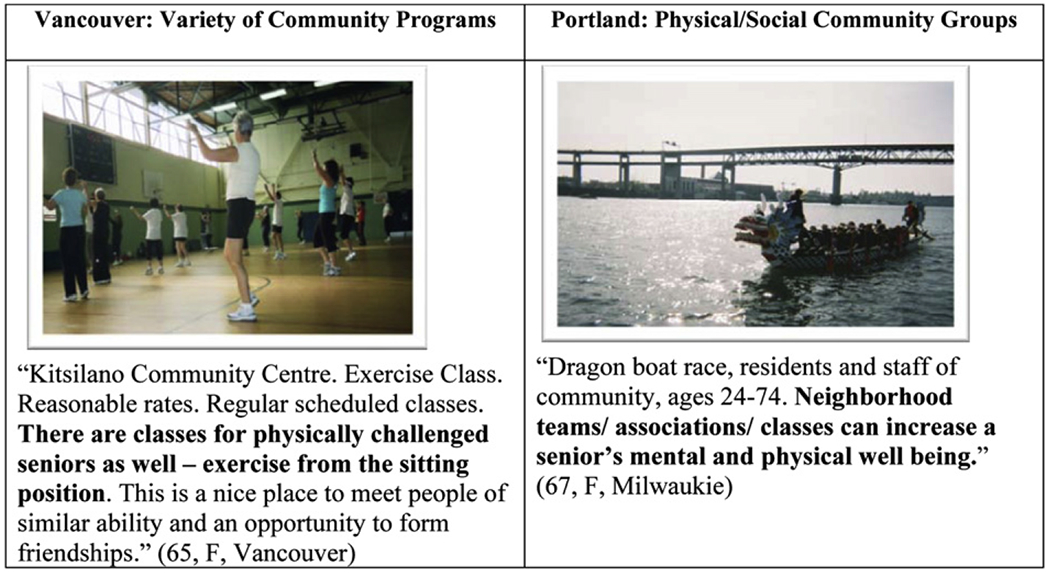

“Community-based programs” refers to formal programs in the community, such as social and exercise programs at community centers, planned community groups, events at city facilities or the local churches. A variety of community-based programs were mentioned in both regions. The most common programs were at local community or seniors’community center. One participant highlighted the programs in her neighborhood community center, “The center has many activities for seniors and their families from travel, exercise classes, painting, wood carving, computers to name a few… [there is] a nice walking area and a dog exercise area which is fenced, dogs do not have to be on leashes…. [there is] meals on wheels, lunch and transportation [for seniors].” One person in Vancouver documented a Senior’s Forum commenting, “Senior’s talk to seniors about ‘our’ issues. Issues and concerns shared and recorded on charts at each table [listen to guest speakers].” Another person in Portland mentioned the opportunity to volunteer, as well as access service at these types of centers, “The adult center is tucked way amid the trees. It is very organized and offers great opportunities for entertainment, education and socialization for seniors. It is also a good place to offer one’s services as a volunteer.”

Availability, regular scheduling and the variety of programs were highlighted as positive factors that encouraged participation. Participants mentioned attending physical activity classes such as water aerobics, exercise classes or Tai Chi. In addition to exercise classes, community groups outside of the community centers were also described. In Portland, such groups included a poetry or art class, tennis club, bird watching group, yoga center or belonging on a local dragon boat team (e.g., Fig. 6). In Vancouver, community groups included walking, hiking, peer counseling and exercise groups. The local library was also described as a place that offered volunteer opportunities and connections to the community. In Portland, the local colleges and churches were also photographed as being places that offered community-based programs. The colleges were a source of community activities, sports, concerts and plays, while the church was seen as a facilitator of community-based programs such as weekly lunches or local events. This was similar to Vancouver, where churches were used as spaces for senior-led recreational programs. The community-based programs in both Portland and Vancouver were seen as facilitators for both physical activity and social activity, often at the same time. Although, many of these programs primarily focused on physical activity, they facilitated positive socialization during or after the programs. This informal and natural opportunity for social interaction associated with a formal or “official” purpose emerged as positive overlay to a “planned activity.” It is possible that for many older adults, the informal social aspect of a planned event (physical or social) could serve as an attractive aspect of the whole experience.

Fig. 6.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Community-Based Programs”‘.

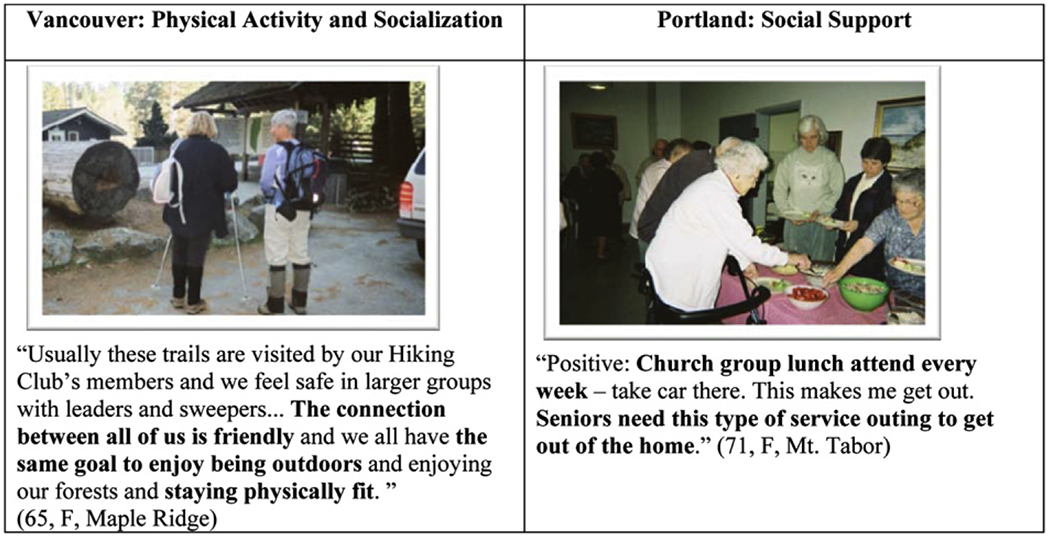

Peer support

Community-based peer support appeared as an important way of facilitating physical and social activities. In the formal and informal community-based programs outlined in the previous theme, the associated informal social interaction with other older adults was a source of meaningful peer support for the study participants. Socialization and peer support were often mentioned as occurring after or during physical activity, whether it be working out and socializing with a friend at the gym or exercise class or post-exercise socialization. The integrated nature of physical activity and social activity is captured well by a participant in her description of a walking group in Vancouver, “Tri Hard Walkers [walk in] town core shopping center. Group of up to 50 walkers meet and walk three times a week – group walks inside mall or outside mall near local area business and residential streets – some streets are with sidewalks, some without… walkers [have] coffee after walk [in Mall Food Court].” Many participants photographed walking with family or friends for exercise or walking to a meeting spot to have coffee and socialize (e.g., Fig. 7). Participants also referenced meeting and socializing with community members or neighbors while on a walk, at the shops or stopping to chat with people passing by. In Vancouver, several participants cited that these informal interactions often led to an increased sense of community in the neighborhood.

Fig. 7.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Peer Support”.

Gardening was often photographed as a facilitator of physical activity and social interaction in both regions. Many of the gardening photographs and descriptions were of community gardening plots where the land was shared with other members of the community. One Vancouver resident astutely noted the benefit of community garden plots while discussing local garden plots, “This is the only community garden in [the neighborhood]. Studies have shown that seniors living in multi-family housing such as condos and townhouse, get more involved in physical activity if they have a small plot land to cultivate.” While attending to plants and vegetables acted as the source of physical activity, several participants enjoyed the social aspect of this activity where a social gardening community was formed. However, the availability of these plots was quite limited in Vancouver, often resulting in long waitlists to obtain a gardening space. It was interesting to note that social aspects were mentioned when residential gardening was photographed and discussed as well. For instance, one Portland resident stated, “Keeps me active…practice social factors – can swap stories and vegetables with my neighbors,” while a Vancouver resident described, “Residential area yards change with the seasons and provide a reason for us to keep walking by to enjoy the gardens and to meet new dogs, cats and residents along the way and to get gardening tips.” In Portland, several participants also documented gardening at home in their private yard.

Intergenerational/volunteer activities

In Portland, many participants photographed and discussed activities, events or places that had a positive intergenerational aspect. Intergenerational activities included students coming to the retirement communities for a visit, events at the local church with all ages involved and watching a student game at the local gym or field. One participant documented an intergenerational gardening project where older adults taught younger people gardening techniques (e.g. Fig. 8). One participant in Portland succinctly noted the positive power of intergenerational gardening, “Both young and old can use these areas to plan gardens. It really doesn’t matter if the person wishes to plant sustainable fruits and vegetables or ornamental flowers and shrubs. The spaces can be as simple as an older vacant lot, a former building site or even some space along sidewalks and curbs. The senior citizens who may no longer be part of the workforce can work these garden plots at their leisure and can share their knowledge with younger generations of parents and children. It would not only be physical activity but would keep them mentally active too. Many community centers or neighborhood activities were available and enjoyed by all ages – an aspect that several participants mentioned in a positive light.

Fig. 8.

Sample photographs and quotes for “Intergenerational/Volunteer Activities”.

Volunteering in the community was also highlighted in the photographs as a facilitator for both physical and social activities. A few participants volunteered at the local schools, which were reported as a positive intergenerational activity that motivated them to get out of the house and walk to the school. One participant observed, “Elementary school is just a block away and I inquired about volunteering there next fall to help with the ESL classes and/or their READ program. They have a Spanish immersion program for kindergarten and it is a great opportunity to be around children and to review my Spanish.” Others reported volunteering at the library or community center or local churches. “I love this church, there is such a wonderful ethnic mix and it as so many projects that I can work on with teenagers, parents and other ‘oldie-goldies’ such as rolling meatballs for spaghetti dinner and cooking the International Festival. They always make me feel useful.” One participant delivered meals on wheels on a weekly basis, reporting it as a positive physical as well as social activity. Volunteering was a facilitator for many participants in the Portland area to be involved and active in their community. There were a few mentions of intergenerational activities in Vancouver. These included participating in activities such as at dances, celebrations, or multicultural events. In several instances, participants highlighted their enjoyment of visiting recreational spaces (e.g. parks) where children and families frequented. While they did not always engage with the children or younger adults, a level of enjoyment was derived from people watching.

Discussion

Although this study was done in eight neighborhoods across two metropolitan areas, significant similarities emerged from the participants’ photographs and descriptions. Themes such as being safe and feeling secure, getting there and comfort in movement reported common facilitators and barriers, regardless of the associated city or neighborhood. Common physical environmental features, such as flat, smooth walkways or sidewalks, aesthetically pleasing environments or presence of benches, handrails and ramps were identified as facilitators to physical activity. This finding corresponds with Lockett et al. (2005), and suggests that these facilitators may be common physical environmental issues among a broad spectrum of the older adult population. Another important universal factor which facilitated physical activity was accessibility of neighborhood amenities. Having walkable access to grocery, post office, bank or community center can support regular and sustainable physical activity in the community. Prior non-photovoice research that focused on older populations in various neighborhoods and cities found positive associations between the level of walking and the accessibility of facilities and the density of housing and population. (Forsyth, Michael, Lee, & Schmitz, 2009; King et al, 2005; Mujahid et al. 2008; Riva, Gauvin, Apparicio, & Brodeur, 2009; Rodríguez, Evenson, Diez & Brines, 2009; Sigematsu et al. 2009)

Another major thread across majority of the participants in both metropolitan areas was the importance of a social component associated with the physical activity. This finding is consistent with social-ecological theory that suggests interpersonal social support and partners for activity is associated with active living (Sallis, Cervero, Ascher, Henderson, Kraft & Kerr, 2006). Level of social cohesion is independently associated with health outcomes among older adults (Macintyre & Ellaway, 2000). In the themes diversity of destinations, community-based programs and peer support, there was a strong social dimension that was described often as facilitating or encouraging the participants to take part in the physical activity event. The purpose of these groups was two-fold – engaging physical activity and socialization with friends or family. Also, there were social groups or programs that primarily focused on the social aspect, such as luncheons or card games; however, many described a physical activity component, such having to walk to the community center to participate. Physical activity and socialization were often intertwined. The integrated nature of physical activity and social interaction, as evidenced through the participants’ photographs and descriptions, is an important contribution to our understanding of the meaning or role of physical activity in the lives of older adults. Given the general reality that many older adults are retired from formal labor force, and in many instances, socially restricted due to cessation or restriction of driving, the importance of positive social stimulation linked with health promoting behaviors cannot be underestimated. Group-based physical activities – either as a formal exercise program (e.g., seniors’ exercise class) or as an informal activity (e.g., neighborhood-based walking club) – have an inherent opportunity for informal social exchange. Our findings suggest that beyond the intention to become or to stay physically active, the potential of interacting with others may play an equally motivating (if not a stronger) factor for older adults to get out of their homes and participate in a physical activity oriented event.

The only notable difference between the two metropolitan areas seen in the findings was the greater relevance of intergenerational and volunteer activities in Portland neighborhoods. The difference in the importance of these activities between the two cities may be due to the chosen sample and/or neighborhoods. Nevertheless, it would be worthwhile in future studies to explore the prevalence of intergenerational activities and volunteering programs for older adults in the Vancouver area, and if there are any structural or programmatic difference between the two regions.

Photovoice was a valuable method for this area of inquiry on several levels: it allowed older adult participants to capture facilitators and barriers for physical activity in their social and physical environments through their own ‘lens’, and the process of taking photographs, writing and discussing their content provided an unique opportunity to reflect on the significance of neighborhood environment (physical and social) in fostering active aging. The photographs and photo journals elicited a wealth of information from the older adults’ individual perspectives and allowed the researchers, participants and community members to engage in a discussion on the physical activity issues as identified through concrete illustrations. This method captured details that might have been overlooked by solely conducting interviews that elicit only narrative stories, and in essence, generated rich data regarding the facilitators and barriers to physical activity in the participants’ daily lives. Also, we believe that the photovoice process increased the participants’ awareness of the role of physical environmental features in their neighborhoods that are related to walking and other physical activity behaviors. The high level of compliance and engagement of the participants indicated that they found the process enjoyable and meaningful.

Photovoice has the potential to empower and mobilize seniors to take action on these environmental issues; however, a sustainable mechanism or method needs be developed to get the relevant groups organized and stay engaged in a meaningful way. Several participants expressed the desire to form a seniors’ coalition to create change in their neighbors using their photographs and joining with others from the study. In order to successfully create these senior advocate groups, more resources are needed to continue the project on the local level. Focus on a small scale geographic area (e.g., neighborhood) has the potential of mobilization of community residents and local resources (Smock, 1997; Stone, 1994). Citizens’ participation in change processes in their own neighborhoods helps to foster sustainable change (Traynor, 2002), as well as contribute to capacity building in the community. Residents have the familiarity and insight about their neighborhood, which can provide a more grounded perspective on the pressing needs (Nowell et al., 2006).

Given the qualitative nature of this study, the objective was to gather older adults’ subjective evaluation of the neighborhood environment by means of a participatory method. The findings were not analyzed in relation to any information on the participants’ actual physical activity. However, the participants included individuals with variability in individual- and neighborhood-characteristics and the consistency of the findings from the two cities suggests that the barriers and facilitators were real and important. Data were collected in only eight neighborhoods in two cities in the Pacific Northwest of North America, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. The barriers and facilitators identified in this county might not be the same in other urban areas. Nevertheless, studies such as this one are essential as a first step in designing interventions for understudied groups, including older adults.

Conclusion

Findings from this study provide strong support for neighborhood physical and social environmental characteristics that have perceived or real influences on health promoting behaviors. The meanings associated with physical features have implications for older adults’ residents’ willingness, sense of security and motivation to participate in activities that can have positive effect on physical and mental health. The importance of neighborhood as a place as having a substantive impact on health and well-being is getting increasing attention from professionals and policy-makers in public health, city planning and urban design. An understanding of what really matters from older residents’ perspectives, as exemplified in this study, can be used as a leverage to identify physical environmental interventions that are grounded in people’s experiences. In order to make meaningful and effective environmental changes, it is important that various stake-holders, such as seniors’ advocacy organizations, city planners, urban designers, landscape architects, traffic engineers, and social planners engage in a collaborative effort. Drawing from ecological theories, one can argue that interventions/policy or practice or design change at a level (e.g., neighborhood) above the level (individual) where impact is desired may have more success in generating change (Bubloz & Sontag, 1993).

In considering the findings from this photovoice study, it is important to acknowledge that the physical environmental aspects supportive of active aging as identified in this study are also beneficial to people in younger age groups. Addressing the barriers and implementing facilitating environmental features would make the neighborhood more liveable for all. The political relevance of bringing about changes in the neighborhood physical environment should not narrowly view the issues as “seniors’ issues,” but rather acknowledge, appreciate and engage other constituent groups in the community. One significant substantive findings of this study related to the need to recognize the interrelationship between physical and social environmental aspects of neighborhood, and in turn, to address both aspects to increase the likelihood of maintaining and fostering physical activity in older adults. “Physical activity” for older adults needs to be conceptualized and approached as a broad spectrum of activities that vary in their levels of “physical activity” component, formality and informality, and the social interaction dimension. It would be important to be innovative in thinking about activities and programs that creatively incorporate a social aspect to a physical activity oriented event or program. Also, the significance of sustainable physical activities, i.e., those that are integrated as part of daily activities, cannot be overstated. Regular activity such as walking safely to the corner store, bus stop, pharmacy or a park can be an important form of physical for many older adults. The sustainability of these activities could be enriched by potential social contact, which in turn, feeds back into the desire of getting out and walking to the amenity.

In future studies, participants with different levels of mobility could be recruited to provide different perspectives on physical and social barriers and facilitators to walking in urban neighborhoods. A truly senior-friendly neighborhood environment needs to take into account challenges and preferences of older adults with differing mobility challenges, physical frailty and cognitive status. Also, cities on North America are increasingly becoming multicultural; therefore, it would be important to explore potential variations in physical activities and associated role of the neighborhood environment for older adults from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an operating research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The authors are grateful to the older adult research participants in Vancouver and Portland metropolitan areas for their enthusiasm, efforts and time. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

References

- Acree LS, Longfors J, Fjeldstad AS, Fjeldstad C, Schank B, Nickel KJ, et al. (2006). Physical activity is related to quality of life in older adults. Health Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubeeluck A, & Buchanan H (2006). Capturing the Huntington’s disease spousal carer experience: a preliminary investigation using the ‘photovoice’ method. Dementia, 5, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, & Wang C (2006). Photovoice: use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 16(10), 1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett F (2000). Finke’s 1792 map of human diseases: the first world disease map? Social Science & Medicine, 50(7—8), 915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J, Carpiano R, Fleming S, & Lauster N (2011). Exploring the distribution of food stores in British Columbia: associations with neighborhood socio-demographic factors and urban form. Health & Place, 17, 961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal JA, & Gullette ECD (2002). Exercise interventions and aging: psychological and physical health benefits in older adults. In Schaie KW, Leventhal H, & Willis SL (Eds.), Effective health behavior in older adults (pp. 157–177). New York: Springer, (Series Societal Impact on Aging). [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A, & Stafford M (2007). How do objective and subjective assessment of neighborhood influence social and physical functioning in older age? Findings from a British survey of ageing. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 2533–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, & Sallis JF (2009). Measuring the built environment for physical activity. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 36(4S), S99–S123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, O’Campo P, Salmon C, & Walker R (2009). Pathways connecting neighborhood influences and mental well-being: socioeconomic position and gender differences. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 1294–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, & Minkler M (2010). Photovoice: a review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education and Behavior, 37, 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury H, Mahmood A, Michael YL, Campo M, & Hay K (2012). The influence of neighborhood residential density, physical and social environments on older adults’ physical activity: An exploratory study in two metropolitan areas. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury H, Sarte A, Michael YL, Mahmood A, McGregor EM, & Wister A (2011). Use of a systematic observational measure to assess and compare walkability for older adults in Vancouver, British Columbia and Portland, Oregon neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Design, 16(4), 433–454. [Google Scholar]

- City of New Westminster. (2010). An update on the ‘Wheelability’ assessment project. Retrieved September 12, 2010 from. http://www.newwestcity.ca/database/rte/files/CNW_DOCS-%23141624-v1-Wheelability_Project_Update_%232.pdf.

- Colman R, & Walker S (2004). The cost of physical inactivity in British Columbia. Victoria, BC: GPI Atlantic. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Curtis S, Diez-Roux AV, & Macintyre S (2007). Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health researcher: a relational approach. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 1825–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham GO, Michael YL, Farquhar SA, & Lapidus J (2005). Developing a reliable senior walking environmental assessment tool. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(3), 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day K, Boarnet M, & Alfonzo M (2005). Irvine Minnesota inventory for observation of physical environment features linked to physical activity: Codebook. Retrieved November 1, 2005 from. https://webfiles.uci.edu/kday/public/index.html.

- Day K, Boarnet M, Alfonzo M, & Forsyth A (2005). Irvine Minnesota inventory (paper version). Retrieved November 1, 2005 from. https://webfiles.uci.edu/kday/public/index.html.

- Deeg D, & Thomése F (2005). Discrepancies between personal income and neighborhood status: effects on physical and mental health. European Journal of Ageing, 2(2), 98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deehr RC, & Shumann A (2009). Active Seattle: achieving walkability in diverse neighborhoods. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 37(6S2), S403–S411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson NG, & Gilron AR (2009). From partnership to policy: the evolution of active living by design in Portland, Oregon. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6), S436–S444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth A, Michael OJ, Lee B, & Schmitz KH (2009). The built environment, walking, and physical activity: is the environment more important to some people than others? Transportation Research: Part D, 14(1), 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Engelke P, & Schmid T (2003). Health and community design. Washington: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, & Donovan RJ (2002). The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 1793–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, & Balfour JL (2003). Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In Kawachi I, & Berkman LF (Eds.), Neighborhoods and health (pp. 303–334). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grant TL, Edwards N, Sveistrup H, Andrew C, & Egan M (2010). Neighborhood walkability: older people’s perspectives from four neighborhoods in Ottawa, Canada. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 18, 293–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather CK, Rhodes DS, & Bardhoshi G (2009). Photovoice as a community-based participatory research: a qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden-Chapman P, Signal L, & Crane J (1999). Housing and health in older people: ageing in place. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 13, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Keast EM, Carlson NE, Chapman NJ, & Michael YL (2010). Using built environmental observation tools: comparing two methods of creating a measure of the built environment. American Journal of Health Promotion, 24(5), 354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WC, Belle SH, Brach JS, Simkin-Silverman LR, Soska T, & Kriska AM (2005). Objective measures of neighborhood environment and physical activity in older women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5), 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D (2008). Neighborhood and individual factors in activity in older adults: results from the neighborhood and senior health study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 16, 144–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClarc CM, Wells DL, Craig D, & Wilson JL (2002). Falling short of the mark: tales of life after hospital discharge. Clinical Nursing Research, 11, 242–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fisher JK, Bauman A, Ory MG, Chodzko-Zajko W, Harmer P, et al. (2005). Neighborhood influences on physical activity in middle-aged and older adults: a multilevel perspective. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity, 13(1), 87–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockett D, Willis A, & Edwards N (2005). Through seniors’ eyes: an exploratory qualitative study to identify environmental barriers to and facilitators of walking. Journal of Nursing Research, 37(3), 48–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, & Ellaway A (2000). Neighborhood cohesion and health in socially contrasting neighborhoods: implications for the social exclusion and public health agendas. Health Bulletin, 58(6), 450–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael Y, McGregor E, Chaudhury H, Day K, Mahmood A, & Sarte FI (2009). Revising the senior walking environmental assessment tool. Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 247–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Shen M, Gowda D, Sánchez B, Shea S, et al. (2008). Relation between neighborhood environments and obesity in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(11), 1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman WL (2006). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell B, Berkowitz S, Deacon Z, & Foster-Fishman P (2006). Revealing the cues within community places: stories of identity, history and possibility. American Journal of Community Psychology, 37(1/2), 29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl HW, Martin M, & Mollenkopf. (2003). Toward measuring proactivity person-environment transactions in late adulthood: the housing related control belief questionnaire. In Scheidt R, & Windley P (Eds.), Physical environments and aging (pp. 135–152). NY: Hawarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl H-W, Shilling O, Nygren C, Fänge A, Sixsmith A, et al. (2007). Relationship between housing and healthy aging in very old age. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DR, Siu O, Yeh A, & Cheng K (2005). Ageing and the urban environment. In Andrews GR, & Phillips DR (Eds.), Ageing and place: Perspectives, policy, practice (pp. 147–163). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson C (2007). The ‘elected’ and the ‘excluded’: sociological perspectives on the experience of place and community in old age. Ageing and Society, 2,321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett K, & Pearl M (2001). Multilevel analysis of neighborhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva M, Gauvin L, Apparicio P, & Brodeur JM (2009). Disentangling the relative influence of built and socioeconomic environments on walking: the contribution of areas homogenous along exposures of interest. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 1296–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez DA, Evenson KR, Diez Roux AV, & Brines SJ (2009). Land use, residential density, and walking: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose L (2007). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, & Frank LD (2003). Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 25(2), 80–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, & Kerr J (2006). An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 297–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer-McDaniel N, Dunn J, Minian N, & Katz D (2010). Rethinking measurement of neighborhood in the context of health research. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf T, Phillipson C, Kingston P, & Smith A (2001). Social exclusion and older people: exploring the connections. Education and Ageing, 16(3), 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt V, Malina RM, & Clark MA (2002). Factors affecting levels of physical activity in adults. Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(3), 143–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T, Lusignolo T, Albert M, & Berkman L (2001). Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychology, 20(4), 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M (2004). Housing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 397–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu R, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Cain KL, et al. (2009). Age differences in the relation of perceived neighborhood environment to walking. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercis, 41(2), 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock K (1997). Comprehensive community initiatives: a new generation of urban revitalization strategies. In Paper presented COMM-ORG: The on-line conference on community organizing and development 1997. [Google Scholar]