Abstract

Federal funding cuts to enrollment outreach and marketing of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace options in 2017 has raised questions about the adequacy of the information the public has received, especially among populations vulnerable to uninsurance. Using health insurance ads aired from January 1, 2018, through December 21, 2018, we conducted a content analysis focused on (a) the messaging differences by ad language (English vs. Spanish) and (b) the messaging appeals used by nonfederally sponsored health insurance ads in 2018. The results reveal that privately sponsored ads focused on benefit appeals (e.g., prescription drugs), while publicly sponsored ads emphasized financial assistance subsidies. Few ads, regardless of language, referenced the ACA explicitly and privately sponsored Spanish-language ads emphasized benefits (e.g., choice of doctor) over enrollment-relevant details. This study emphasizes that private-sponsored television marketing may not provide specific and actionable health insurance information to the public, especially for the Spanish-speaking populations.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, health insurance, advertising, language, health insurers

Introduction

In 2019, approximately 33.2 million people were uninsured in the United States (Cohen et al., 2021). Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended health insurance to 20 million Americans by 2016, actions of the Trump administration—including reducing federal investment in health plan marketing and enrollment outreach and expanding regulatory approvals of non-ACA compliant plans—have contributed toward a reduction in the overall rates of health insurance starting in 2017 (Griffith et al., 2020). These losses have been greater in communities of color and immigrant communities because of challenges with access to employer-based coverage, eligibility issues (e.g., living in states without Medicaid expansion, lawfully-present immigrants who have been in the United States for less than 5 years), and complicated enrollment procedures (Tolbert et al., 2020). Increases in uninsurance have been particularly pronounced in the Latinx population, which represented more than half (57%) of the increase in the 2019 uninsured rate among the nonelderly population (Tolbert et al., 2020).

Previous research has demonstrated relationships between televised media and insurance-related outcomes. Specifically, research examining the first open-enrollment period of the ACA (2013–2014) identified aggregate associations between the volume of insurance ads aired on TV to county-level insurance gains generally and Medicaid enrollment gains in particular (Karaca-Mandic et al., 2017); at the individual level, higher volumes of advertising exposure were also associated with insurance-related outcomes in 2014 (Gollust, Wilcock, et al., 2018). Subsequent research examining county-level Marketplace enrollment data for the 2015 through 2018 open enrollment periods showed a statistically significant relationship between insurance enrollment and airings of advertisements by state sponsors in particular (Shafer et al., 2020). Another study examining discontinuities in advertising between media markets also found relationships between advertising and enrollment, but these relationships differed based on sponsor type (state or federal government vs. private companies; Aizawa & Kim, 2020). Collectively, these studies support the importance of television ads on outreach to insurance consumers and suggest that the sponsor of the ad (as public or private) is an important distinction.

The Trump administration implemented various policies that contributed to increases in uninsurance rates (i.e., elimination of the health insurance mandate, discussion of Medicaid work requirements, and ending cost-sharing subsidies for health insurers; Simmons-Duffin, 2019). Yet, the change most relevant to this study is that the administration reduced funding for advertising as well as for navigators, who play a vital role in providing important information to communities with high uninsurance rates (Hoppe, 2018). They cut federal navigator funding from US$63 million (2016) to US$36 million (2017) to US$10 million (2018 & 2019) by declaring navigators’ enrollment numbers as ineffective (Galewitz, 2018; Pollitz & Tolbert, 2020). They also reduced funding for federal Marketplace advertising plans from 100 million to 10 million, completely eliminating the television advertising budget, and instead focused its limited outreach efforts on email, digital media, and text messages (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2017)—all within a shorter Marketplace open enrollment period (Shafer et al., 2020).

These federal advertisements and navigator-led outreach funding cuts led to questions about the adequacy of information the public was receiving about insurance options during this time period, especially with the increasing role of private sponsors in advertising, which tended not to communicate much detail about the federal marketplaces (Gollust, Baum, et al., 2018). Furthermore, federal disinvestment in outreach was not the only event occurring during this time that has implications for the public’s exposure to health insurance-related messaging. While not directly examined in this study, there was also a high volume of health care messaging in political ads airing during the 2018 midterm election cycle containing conflicting messages about the future of the health care system between the political parties (Gollust et al., 2020). Understanding what information people received about health insurance during this period of political contestation and federal disinvestment in outreach and enrollment is an important research priority, with clear health equity implications, as we detail below.

New Contribution

Broadcast media, encompassing local television and national cable, is an important source of health information for the public, especially for the Latinx population (Cheong et al., 2007; Kelley et al., 2016), but only a handful of studies have examined the content of health insurance advertisements aired on broadcast TV. Existing research—all examining the content of ads aired before the Trump administration—showed, for instance, that among ads aired between 2013 and 2016, Spanish-language ads were more likely to mention financial and enrollment assistance and less likely to mention the simplicity of enrollment and preventive services (Barry et al., 2018). Another study found that Spanish-language ads were more likely to mention telephone/in-person enrollment assistance resources over online resources (e.g., website) compared with English-language ads; this pattern increased over time (Pintor et al., 2020). Across both languages, ads also featured declining references to the ACA from 2013 to 2016 (Barry et al., 2018). In addition, Spanish-language ads were more likely to be sponsored by state marketplaces over private sponsors (Pintor et al., 2020).

With the elimination of federal advertising, the open enrollment period in 2018 saw a shift toward more reliance on privately sponsored ads for health insurance information. This adjustment may have negatively impacted access to information about enrollment, especially for the Spanish-speaking population. Indeed, health insurance navigators at the time expressed concern that the progress made under the Obama administration for the Latinx population would be set back, given the combination of a shorter enrollment period, cuts to navigator funding, and limited marketing (Andalo, 2017). This study contributes to knowledge on this topic as it is the first to examine and compare the content of English-language and Spanish-language televised health insurance advertisements during a time of reduced federal investment.

Background

The ACA significantly reduced the number of uninsured people in the United States from 2010 (46.5 million uninsured) to 2016 (26.7 million uninsured). This trajectory changed in 2017 when the uninsurance rate increased, likely driven by Trump administration changes to health insurance outreach, insurance availability, and insurance affordability (Artiga, Orgera, & Damico, 2020; Garfield et al., 2019). Many groups, including Latinx children and Black individuals, saw increases in uninsurance during this time (Artiga, Orgera, & Damico, 2020).

The largest increases in uninsurance from 2018 to 2019 were among Latinx and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander populations (Tolbert et al., 2020). Overall, the ACA’s progress among the Latinx population, characterized as approximately 32% of the 19.2 million Latinx individuals obtaining insurance between 2010 and 2015 (Garrett & Gangopadhyaya, 2016), has nearly been reversed since 2017 (Tolbert et al., 2020). Various factors contributed to uninsurance disparities among this population, including community factors (i.e., immigration status, immigration-related fears toward changing policies) and policy environment-related factors (e.g., Medicaid renewal process changes, elimination of the individual mandate penalty; Artiga, Tolbert, & Orgera, 2020). Since 2020, COVID-19 has likely augmented uninsurance rates among this population through a higher unemployment rate combined with immigration-related fears toward ACA marketplace coverage options (Artiga, Tolbert, & Orgera, 2020).

Sources of Health Insurance Information

To understand the significance of decreased investment in outreach and enrollment, it is important to contextualize information from health insurance advertising within the broader health information ecosystem. A 2016 study found that while health professionals were the primary information source for older people, the Black population, women, and populations with lower levels of income and education, the internet was the most common source for higher income earners, the uninsured, younger people, college-educated people, men, and individuals without a health care provider (Kelley et al., 2016). Among Hispanic-identifying participants and non-U.S.-born individuals, broadcast media was the main way they got health information (Kelley et al., 2016), reinforcing the important role of health insurance information conveyed through television. Another study found that for the Latinx population, the level of exposure to mass media-based health information was positively associated with health-related decisions and health information-seeking behavior and was more important to both behaviors than health literacy or language proficiency (De Jesus, 2013).

Previous research also provides context about health information-seeking among the uninsured population. A 2016 study found that people who are uninsured receive health insurance information through their social networks, health care professionals, and media but mainly rely on relationships with health care providers over television and the internet (Furtado et al., 2016). In addition, the uninsured population is less likely to indicate having a typical source of health information (Kelley et al., 2016). Therefore, this population needs to access user-friendly information from media, especially mass media sources besides the internet (Cheong et al., 2007). In addition, compared with Hispanic people with insurance, Hispanic people without insurance are more likely to choose Spanish-language media such as television, radio, and newspapers over English-language media and the internet (Cheong, 2007).

The research earlier highlights where the public generally gets their health and health care information, but there is limited research describing where the public receives their health insurance enrollment information, specifically. Previous research suggests that the public trusts their health care providers, their family and friends, their employer’s benefits manager (among respondents who are employed) for health insurance information over health insurance companies, mass media, and government (Furtado et al., 2016; Isaacs, 1996). In addition, recent studies found that more focused outreach efforts can be particularly effective for enrollment, such as mail-based outreach (Hom et al., 2017) and telephone outreach efforts, especially for non-English-speaking communities (Myerson et al., 2022).

Health Insurance Messaging and Health Equity

Although there is a policy-relevant rationale to examine the health information available to Spanish-language viewers as noted above (i.e., the changing health policy landscape, the Latinx population’s uninsurance rate and previously identified differences across English-language and Spanish-language health insurance ads), there are also rationales for this research based on health communication theory. The knowledge gap hypothesis suggests that the availability of information in mass media will lead to highly educated populations accessing important information (such as health insurance enrollment details) more quickly than populations with less education, therefore widening knowledge-related inequities (such as knowledge of health insurance options; Tichenor et al., 1970). However, advertisements aired on local television could partially contribute to equalizing knowledge levels, as television is viewed widely and is a more common source of local information (such as health insurance) for those with lower education than online or print sources (Barthel et al., 2019). Furthermore, one study found that the Latinx population was more likely to respond to health messages on television compared with the White population (Viswanath & Ackerson, 2011). To prevent information disparities, the knowledge gap hypothesis proposes that health messages be aired consistently and prominently and tailored to the population in need of the information (Viswanath & Finnegan, 1996).

The concept of “communication inequality” advances the knowledge gap theory further, describing how information may not be equally distributed, acquired, or used based on structural determinants including social position, educational and occupational structure, and capability to use said information (Viswanath, 2006). A communication inequality conceptual framework reinforces both the importance of examining what types of information were available to underserved populations (i.e., those speaking Spanish) and the availability of resources the underserved population has to act upon said information. Previous research suggests that cuts to navigator funding may have disproportionately impacted the Latinx population who relied on navigators for health insurance enrollment (Andalo, 2017; Pollitz et al., 2020). In fact, Spanish-language advertisements aired before 2017 mentioned enrollment assistance resources (like navigators) more than English-language ads (Pintor et al., 2020). With limited funding for health insurance navigators starting in 2017, combined with a shorter Marketplace open enrollment period in 2018, the Spanish-speaking population would likely have needed to rely more heavily on limited media for health insurance information, potentially worsening equitable access to health insurance.

Research Gap

As described earlier, the Trump administration implemented various changes to outreach for health insurance, including reduced federal investment, and no previous research has systematically examined the information received by the public amid these changes via advertisements aired on TV—a significant source of information for Americans in general and the Latinx population in particular (Flores & Lopez, 2018). Most importantly, it is unclear what outreach strategies, main messaging objectives, and specific enrollment-related information were highlighted in English-language and Spanish-language ads by private insurers in 2018 to “fill the gap” left by the elimination of federal outreach. This study thus responds to two distinct research questions:

Research Question 1: What marketing appeals were used in health insurance ads aired in 2018, and how do they vary by target population of ads (i.e., English-speaking vs. Spanish-speaking populations)?

Research Question 2: Were there differences in marketing appeals across target population of ads (i.e., English-speaking vs. Spanish-speaking populations) and by sponsor type (i.e., private health insurers versus public sponsors)?

Data and Method

Data

Our data on health insurance product advertising originated from Kantar/Campaign Media Analysis Group (CMAG). Kantar/CMAG tracks 936 predominantly English-language television stations across all 210 designated market areas (DMAs) in the United States and 108 Spanish-language TV stations across 38 DMAs (Pintor et al., 2020). Kantar/CMAG identified a total of 1,723 advertisements (“creatives”) for health insurance-related products that aired 877,318 times on broadcast television or national cable across all DMAs between January 1 and December 21, 2018. After filtering out Medicare-focused creatives, 960 advertisements remained that aired 489,489 times during this time, which encompasses the 2019 Healthcare.gov open enrollment period, November 1 to December 15, 2018.

We constructed a sample that allowed for the comparison of Spanish-language and English-language ads and had maximum content variability. First, we included all Spanish-language creatives (N = 189), excluding one ad mislabeled as a Spanish-language ad. To maximize our sample variability and limit ad redundancy in English-language ads, we conducted a random 46% sample of ads by the top three most common private sponsors, rather than coding each creative. The top three English-language sponsors (Blue Cross/Blue Shield, United Healthcare, and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) contributed 37% (N = 358 creatives) of the total unique creatives available in the dataset. Next, we included all ads sponsored by less common entities (those ranked as the fourth-most-prevalent or less in the total data set; N = 560 creatives). After accounting for these sampling decisions, in total, we included 78% of all possible creatives in our analytic sample (N = 749 total creatives), which encompassed 81% of all available health insurance ad airings (non-Medicare) during this timeframe.

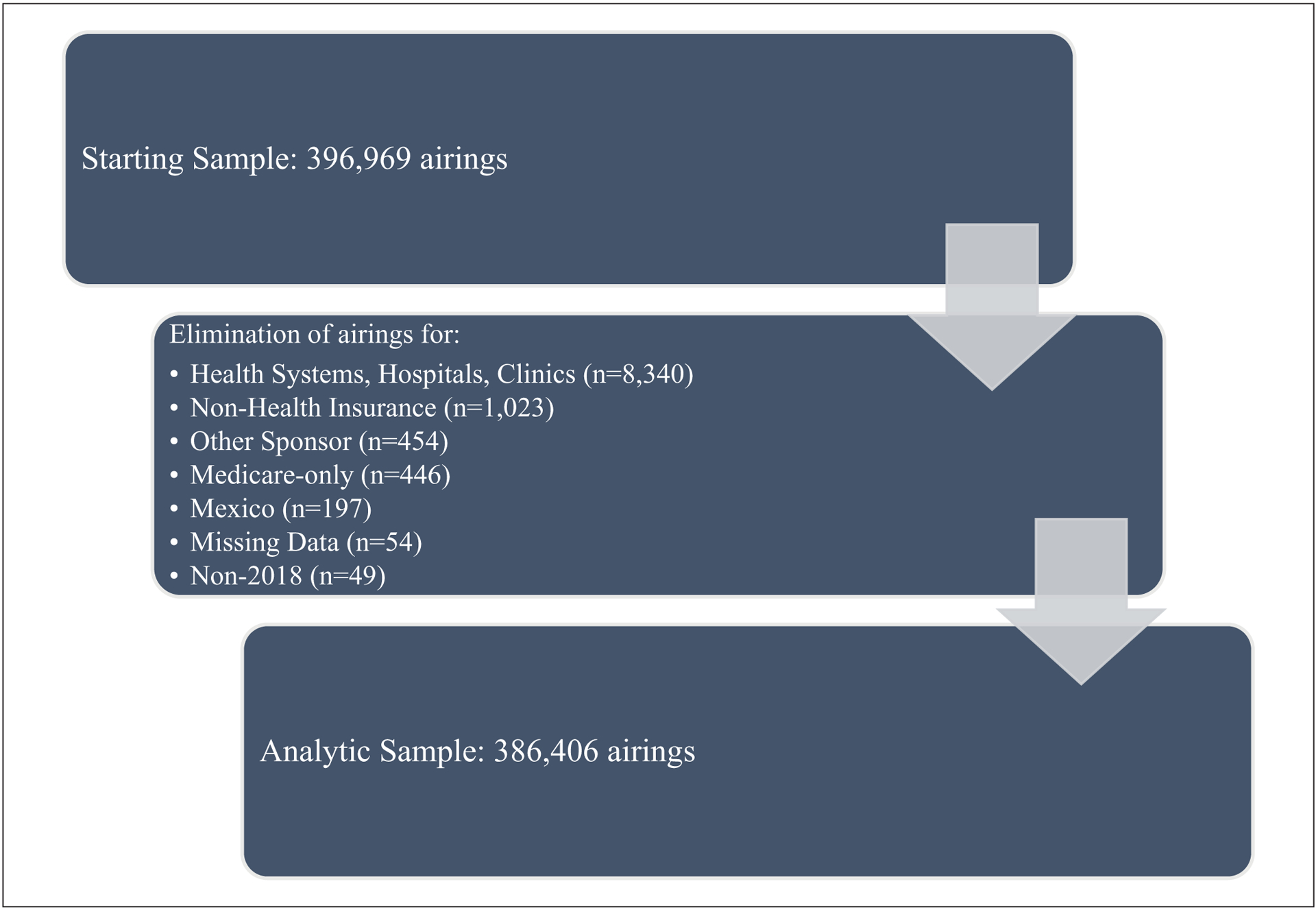

After constructing our analytic sample of 749 creatives (n = 396,969 airings), we applied additional exclusion criteria focused on ads for health insurance products (see Figure 1). We removed ads that featured health systems, hospitals, and clinics that did not offer a health insurance product; ads for non-health insurance products (e.g., dental, home, and life insurance); ads about Medicare products (ones missed in the primary exclusion); ads for Mexico-based health products (aired in overlapping U.S. and Mexico markets); and ads not aired in 2018 that were mistakenly included in the data. In addition, we excluded two ads (54 ad airings) where more than half of the ad information was missing because of a technical error (e.g., incomplete audio or visual media). Last, we excluded ads (454 airings, or 0.11% of total airings) from nonpublic and nonprivate sponsors (typically stations or nonprofit organizations) that did not market a particular health insurance plan. After applying the exclusion criteria, we were left with a final analytic sample of 499 English- and 168 Spanish-language creatives that aired 386,406 times on local television or national cable in 2018. Our sampling decisions are congruent with the methods of similar research (Barry et al., 2018; Pintor et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Analytic Sample Flowchart.

Codebook Development

Four authors reviewed previous codebooks from studies examining ad content (Barry et al., 2018; Gollust, Baum, et al., 2018) and adapted and added variables to the codebook to reflect the 2018 context using an inductive process. The team met regularly to watch ads from the sample, discuss themes that emerged, and operationalize these details into variables relevant to the research questions. New variables that intended to capture appeals encouraging enrollment—such as references to prescription drug benefits or access to specialists—or were reflective of the social determinants of health particularly for the Latinx population—such as plans advertising non-medical benefits like transportation or job assistance—were added, among other variables. The team coded each ad for the following elements: ad language (Spanish vs. English); ad objective; ad sponsor; marketing appeals (including product appeals and benefit appeals); and ACA policy-related references. Finally, Kantar provided information about ad length, ranging from 10 to 120 seconds, which was used in statistical tests. Detailed descriptions of each measure are found in the appendix.

Three authors double-coded a random sample (18.3%) of English-language ads to assess interrater reliability. One author coded all the Spanish-language ads and a sample of English-language ads and was part of the instrument training along with the other three coders. To ensure coding reliability, all four coders met regularly to compare and discuss ad coding differences. All variables presented in this study exceeded conventionally accepted levels of interrater reliability (κ > 0.65). Kappas for each variable are listed in the appendix.

Key Variables

Ad objective distinguishes ads that provide information to a viewer about how to enroll in a plan—what was coded as an enrollment objective—and those that focus more broadly on an insurer’s reputation—what was coded as a branding objective. Ads focused on raising awareness about a health condition or non-health-insurance service (e.g., breast cancer screenings) were coded as branding/public service announcement (PSA).

Ad sponsor included classifications for the private sector (e.g., private health insurance, integrated insurance and health delivery systems, or insurance brokers), states, and the federal government. Federal government-sponsored ads during this period did not include any marketing of Healthcare. gov (as expected given the budget was eliminated) but did include two ads (aired 141 times) that advertised the NIHSeniorHealth.gov website and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Beyond Table 1, we combined federally and state-sponsored ads, which we called public sponsors.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Analytic Sample of Television Ads Aired January 1–December 31, 2018.

| Overall sample (n = 386,406) | English sample (n = 318,070) | Spanish sample (n = 68,336) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of ads | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Language spoken in ad | |||

| English | 318,070 (82.3) | ||

| Spanish | 68,336 (17.7) | ||

| Ad objective | |||

| Enrollment | 266,584 (69.0) | 216,815 (68.2) | 49,769 (72.8) |

| Branding | 106,122 (27.5) | 91,527 (28.8) | 14,595 (21.4) |

| Branding/public service announcement | 13,700 (3.6) | 9,728 (3.1) | 3,972 (5.8) |

| Sponsor type | |||

| Federal | 141 (0.0) | 86 (0.0) | 55 (0.1) |

| State | 67,742 (17.5) | 51,310 (16.1) | 16,432 (24.1) |

| Private | 318,523 (82.4) | 266,674 (83.8) | 51,849 (75.9) |

| Private ad sponsor (n = 318,523) | |||

| Insurance Company | 283,760 (89.1) | 244,126 (91.5) | 39,634 (76.4) |

| Insurance Company & Health System | 31,536 (9.9) | 20,768 (7.8) | 10,768 (20.8) |

| Insurance Broker | 3,227 (1.0) | 1,780 (0.7) | 1,447 (2.8) |

| Ad length | |||

| Less than 30 s | 30,039 (7.8) | 26,957 (8.5) | 3,082 (4.5) |

| 30 to 60 s | 336,943 (87.2) | 274,437 (86.3) | 62,596 (91.6) |

| 90 to 120 s | 19,424 (5.0) | 16,766 (5.3) | 2,658 (3.9) |

Note. Chi-square statistical tests between English and Spanish samples were conducted with English-sample ads as the reference group. All differences were statistically significant at 0.001.

Marketing appeals are the detail provided in an ad that could entice a viewer to consider enrolling, and as such, were used most often in ads with an enrollment objective. We identified three types of messaging under this category. The first category included product appeals, which were (a) explicit references to “insurance,” signaling to the viewer the advertised product was health insurance and (b) product marketing (e.g., branding/loyalty). The second category was benefit appeals, which included (a) access to prescription drug benefits, nonmedical benefits (e.g., employment-related assistance or child care), specialists, and wellness programs (e.g., gym memberships), and (b) emphasis on consumer choice (choice of doctor). The third category was ACA-policy related references, which included reference to (a) cost and financial incentives (e.g., financial assistance/subsidies or low-cost plans), (b) financial penalties, and (c) explicit ACA policy terms (e.g., mentions of the marketplace, government, ACA or Obamacare).

Data Analysis

We analyzed data at the airing level (vs. the creative level) to account for the number of times a particular message in a particular ad was aired on TV, as each creative was aired a variable number of times over the study period, both within and across study markets. In essence, estimating the frequency of content features at the airing level weights messages by how often they were available to the public, so messages featured in frequently aired ads have higher volumes than messages featured in less-frequently-aired ads. Previous research analyzing advertisement content has used a similar approach (see, e.g., Barry et al., 2018).

We first quantified ad airings by language (Table 1) and then used chi-square tests to assess differences by ad objective, language, sponsor type, and ad length. We also examined differences in marketing appeals by ad language (Table 2) and subsequently across ad language stratified by sponsor type (Table 3). We ran multivariate logistic regression models controlling for ad length, an ordinal measure, to estimate statistically significant differences in ad messages by language and sponsor. We included ad length in our analyses because we observed systematic differences in length of ads by sponsor type and longer ads could include more marketing appeals.

Table 2.

Proportion of Marketing Appeals by Ad Language in Enrollment Television Ads Aired January 1 to December 31, 2018.

| Overall sample (n = 266,584) | English sample (n = 216,815) | Spanish sample (n = 49,769) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing appeal and policy references | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Product appeals | |||

| Explicit reference to insurance | 81,065 (30.4) | 72,541 (33.5) | 8,524 (17.1) |

| Brand/Loyalty | 50,336 (18.9) | 42,195 (19.5) | 8,141 (16.4) |

| Benefit appeals | |||

| Prescription drugs | 96,943 (36.4) | 76,946 (35.5) | 19,997 (40.2) |

| Nonmedical benefits | 70,432 (26.4) | 64,233 (29.6) | 6,199 (12.5) |

| Choice of doctor available | 68,815 (25.8) | 48,206 (22.2) | 20,609 (41.4) |

| Access to specialists | 44,513 (16.7) | 38,832 (17.9) | 5,681 (11.4) |

| Wellness programs | 27,487 (10.3) | 27,487 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| ACA-policy-related references | |||

| Financial assistance/subsidies/tax credits available | 51,195 (19.2) | 40,503 (18.7) | 10,692 (21.5) |

| Mention of “Marketplace” | 27,730 (10.4) | 25,172 (11.6) | 2,558 (5.1) |

| Mention of “government” | 4,648 (1.7) | 4,553 (2.1) | 95 (0.2) |

| Mention of “ACA” or “Obamacare” | 3,236 (1.2) | 2,151 (1.0) | 1,085 (2.2) |

| Avoiding penalties | 886 (0.3) | 122 (0.1) | 764 (1.5) |

| Lower cost plans cheaper/better than ACA | 318 (0.1) | 318 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

Note. Statistical tests between English and Spanish samples were calculated using logistic regression with English-sample ads as the reference group controlling for ad length. All differences were statistically significant for non-zero cells at 0.001. ACA = Affordable Care Act.

Table 3.

Marketing Appeals by Sponsor Type and Language in Enrollment Television Ads Aired January 1—December 31, 2018.

| Overall sample (N = 266,584) | English sample (n = 216,815) | Spanish sample (n = 49,769) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public (n = 65,713) | Private (n = 200,871) | Public (n = 49,822) | Private (n = 166,993) | Public (n = 15,891) | Private (n = 33,878) | |

| Marketing appeal and policy references | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Product appeals | ||||||

| Explicit reference to insurance | 40,835 (62.1) | 40,230 (20.0) | 37,077 (74.7) | 35,464 (21.2) | 3,758 (23.7) | 4,766 (14.1) |

| Brand/loyalty | 6,081 (9.3) | 44,255 (22.0) | 5,973 (12.0) | 36,222 (21.7) | 108 (0.7) | 8,033 (23.7) |

| Benefit appeals | ||||||

| Prescription drugs | 2,698 (4.1) | 94,245 (46.9) | 2,462 (4.9) | 74,484 (44.6) | 236 (1.5) | 19,761 (58.3) |

| Nonmedical benefits | 0 (0.0) | 70,432 (35.1) | 0 (0.0) | 64,233 (38.5) | 0 (0.00) | 6,199 (18.3) |

| Choice of doctor available | 184 (0.3) | 68,631 (34.2) | 0 (0.0) | 48,206 (28.9) | 184 (1.2) | 20,425 (60.3) |

| Access to specialists | 0 (0.0) | 44,513 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 38,832 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5,681 (16.8) |

| Wellness programs | 96 (0.2) | 27,391 (13.6) | 96 (0.2) | 27,391 (16.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ACA-policy-related references | ||||||

| Financial assistance/subsidies/tax credits available | 40,185 (61.2) | 11,010 (5.5) | 31,469 (63.2) | 9,034 (5.4) | 8,716 (54.9) | 1,976 (5.8) |

| Mention of “Marketplace” | 9,344 (14.2) | 18,386 (9.2) | 9,146 (18.4) | 16,026 (9.6) | 198 (1.3) | 2,360 (7.0) |

| Mention of “government” | 1,799 (2.7) | 2,849 (1.4) | 1,704 (3.4) | 2,849 (1.7) | 95 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mention of “ACA” or “Obamacare” | 0 (0.0) | 3,236 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2,151 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1,085 (3.2) |

| Avoiding penalties | 0 (0.0) | 886 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 122 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 764 (2.3) |

| Lower cost plans cheaper/better than ACA | 0 (0.0) | 318 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 318 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Note. Statistical tests between English and Spanish samples were calculated using logistic regression with English-sample ads as the reference group controlling for ad length. All differences were statistically significant for non-zero cells at 0.001 except for branding/loyalty in the overall sample (p = .69) and mention of marketplace in the overall sample (p = .003). ACA = Affordable Care Act.

Results

Sample Description

Table 1 displays a description of the analytic sample and a comparison across ad language. All differences by ad language were statistically significant at p < .001. More ads aired in English (82.3%) than Spanish (17.7%). Across all ads, the majority (69.0%) had an enrollment objective; less than a third included a branding objective (27.5%), and less than 5% (3.6%) were PSAs informing the public about a public health issue. Most of the aired ads were sponsored by a private insurance company, agency, broker, or health plan (82.4%), as compared with ads sponsored by the state government (17.5%) or the federal government (0.04%). Among privately sponsored ads (n = 318,523), most were affiliated with an insurance company (89.1%) as compared with an insurance company partnered with a health system (9.9%; e.g., an integrated delivery system, e.g., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center health plan) or an insurance broker (1.0%). Most ad airings (87.2%) were 30 to 60 s long. A quarter of enrollment ad sponsors had ad airings in both English and Spanish, while the majority (64%) of sponsors aired ads only in English (not shown). Less than 2% (4,567 ad airings) were ads for non-health insurance products (not shown), specifically discount plan organizations (DPOs). They collect monthly fees from members in exchange for discounts on services or products from participating providers but are not health insurance (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2012).

Table 2 presents the overall prevalence of product and benefit appeals and ACA policy-related references among ad airings with an enrollment objective (n = 266,584) across English-language and Spanish-language ads. All differences (adjusting for the length of the ad) were statistically significant for non-zero cells at p < .001. Less than a third of ad airings in the overall sample explicitly used the term “insurance” (30.4%). The most frequently used benefit appeals were for prescription drugs (36.4%), non-medical benefits (26.4%), and the choice of doctor available (25.8%). These same benefit appeals were observed in similar proportions among the sample of English-language ad airings. Appeals related to nonmedical benefits, which included references to transportation or employment-related support, were less frequently observed in Spanish-language ad airings (12.5%) compared with English-language airings (29.6%). In addition, appeals focused on the choice of doctor were observed more among Spanish-language ad airings (41.4%) than those for English-language ads (22.2%). No Spanish-language ads mentioned wellness programs and less than 20% explicitly mentioned “insurance.”

References to ACA-related policy—financial assistance availabilities, subsidies, or tax credits—were more common in Spanish ads, appearing in 21.5% of Spanish-language airings compared with 18.7% of English-language airings. Despite federal action eliminating the financial penalty associated with the ACA individual mandate that went into effect in 2019, a small percentage of Spanish (1.5%) and English-language ad airings (0.1%) included an appeal to purchase insurance to avoid a penalty. Only 10.4% of ad airings overall referenced a “marketplace,” referring to the health insurance marketplaces created through the ACA. Yet, more English-language airings referred to the marketplace (11.6%) as compared with Spanish-language (5.1%). Very few ad airings ever referenced the government (1.7%) and even fewer (1.2%) referred to the ACA or “Obamacare”; references to the government were even lower in Spanish-language airings than in English (0.2% compared with 2.1%), although references to ACA/Obamacare were higher (2.2% compared with 1.0%).

Table 3 presents the differences in marketing appeals by language type and sponsor type for the sample of ad airings with an enrollment objective (N = 266,584). All differences were statistically significant for non-zero cells at p < .001 except for the mention of the marketplace (p = .003) and branding/loyalty in the overall sample (p = .69). Nearly two-thirds of public-sponsored ad airings (62.1%) explicitly mentioned “insurance.” Among public sponsored ads, the majority of these mentions were in English-language ads (74.7%), while “insurance” mentions were observed in fewer than a quarter of Spanish-language ads (23.7%). Privately sponsored ad airings contained a higher proportion of most of the benefit appeals, including prescription drugs (46.9%), non-medical benefits (35.1%), the choice of doctor available (34.2%), and access to specialists (22.2%). Yet, the majority of the prescription drug and choice of doctor available benefit appeals were found among the private sponsored Spanish-language ad airings (58.3% and 60.3%, respectively) compared with the private sponsored English-language airings (44.6% and 28.9%, respectively). The English-language private ads featured a higher proportion of references to non-medical benefits (38.5%) and access to specialists (23.3%) compared with Spanish-language ads (18.3% and 16.8%).

Publicly sponsored ad airings were much more likely to mention financial assistance or subsidies (61.2%) than were privately sponsored ads (5.5%). Similarly, publicly sponsored airings mentioned the marketplace (14.2%) more than privately sponsored ads did (9.2%). Among public sponsored ads, English-language ads had more ad airings referencing the marketplace than did Spanish-language ads (18.4% vs. 1.3%). In addition, while public sponsored ads did not mention the ACA or Obamacare, these terms were included in a small proportion of privately sponsored ad airings (1.6%), mostly in private sponsored Spanish-language ads (3.2%). Finally, the avoiding penalties message was infrequently aired in privately sponsored ads (0.4%) but again mostly in private sponsored Spanish-language airings (2.3%).

Discussion

Most health insurance ads aired on TV in 2018 were from private sponsors, as expected given the elimination of federal advertising under the Trump administration, and most were aired in English. Similar to Kemmick Pintor and colleagues (2020), our study also found that Spanish-language ads had a larger proportion of state-sponsored ads (24%) compared with English-language ads (16%). Our study also found differences in messaging by advertisement language and sponsor type. Overall, our analysis suggests that (a) the Spanish-speaking population was exposed to different information about health insurance than was the English-speaking population, given content differences between Spanish-language ads and English-language ads; (b) privately sponsored ads were not “filling in” for the messaging lost by decreases in federally sponsored ads, in either language; and (c) declining references to the ACA may indicate a lesser awareness from the public about the considerable governmental role in health insurance provision. This latter point signifies an example of the “submerged state,” when the government’s role in facilitating benefits to the public is unclear because of private sector delivery of services (Mettler, 2011).

Our analysis revealed that Spanish-language ads conveyed some health information at different rates than did English-language ads. First, although still very uncommon, significantly more Spanish-language private ads mentioned “ACA” and “Obamacare” than did English-language ads, signifying that Spanish-language audiences may have been exposed to more ACA-policy related cues. Second, references to penalties were aired in more Spanish-language ads; although quite infrequent, this information would have been misinformation in the context of the fall 2018 open enrollment period as there were no penalties for lacking insurance in 2019. Third, Spanish-language public sponsored ad airings contained significantly fewer “insurance” and “marketplace” mentions than did English-language ads, indicating that Spanish-speaking consumers were not given direct information about the product being advertised—a gap that has important equity implications because of differences in exposure to health insurance enrollment-relevant information.

Compared with previous research on Spanish-language ads aired in earlier periods, 2018 Spanish-language ads featured some markedly different content. References to financial assistance mentions of “ACA” or “Obamacare,” and mentions of “marketplace” were higher in previous years. For example, Barry et al. (2018) found that almost 61% of Spanish ads across the first three enrollment periods (2013–2016) had a financial assistance appeal, yet only 22% of all Spanish ads in 2018 had the same appeal, although considerably more did so among the public ads (54.9%). In addition, the most prevalent marketing appeals among 2018 Spanish-language ads were doctor choice availability and prescription drugs, likely driven by the increasing prevalence of private sponsored ad airings in 2018. Also, in the earlier years, public sponsors comprised a higher portion of Spanish-language ads (Pintor et al., 2020). These results suggest an information gap about marketplace health insurance eligibility in Spanish-language ads, which could have contributed to information inequities for the Spanish-speaking population.

Private sponsors of advertisements did not provide important policy-relevant information to consumers; instead, they communicated benefit appeals such as prescription drugs, non-medical benefits, and physician choice. Only 20% of private sponsored airings mentioned “insurance” (a critical cue to the consumer of the product being marketed) compared with 62% of public sponsored airings. Furthermore, less than 10% of private sponsored airings mentioned “marketplace” (9.2%) and financial assistance (5.5%) compared with 14.2% and 61.2% of public sponsored airings, respectively. Research demonstrates that information about affordability is important to enrollees on the Marketplace, much more so than information about plan reputation or coverage of specific medications (Hero et al., 2019). Our findings indicate that information relevant to enrolling in ACA-compliant plans is less available in the televised information ecosystem where private-sponsored ads dominate. Private and public sponsors highlighted different information that consumers could use for their health insurance-related decision-making, but an average TV viewer would have been mainly exposed to private ads with very little health policy informational content.

Our study also found declining explicit references to the ACA, evidence of the “submerged state,” as noted above (Mettler, 2011). In our study, explicit references to the ACA were extremely uncommon; they appeared in no public ads and just 1.6% of airings in private ads (which sometimes referenced that their plans were “cheaper than the ACA”). The decline in explicit ACA references—which was already apparent between 2013 and 2016 (Barry et al., 2018)—was complete by 2018, with virtually no ads making any explicit reference to the law, and rarely to government. The state was essentially “submerged” by 2018, with the public role in regulating health insurance marketplaces invisible in TV marketing (Mettler, 2011).

These findings must be interpreted with some limitations in mind. First, people who identify as Hispanic or Latinx do not necessarily acquire information solely from Spanish-speaking media (Pardo & Dreas, 2011); approximately 73% of Latinos speak Spanish at home (Krogstad & Lopez, 2017). The impact of media on information access among people who identify as Hispanic or Latinx may vary depending on their comfort speaking English, which is associated with differences in trust in media and types of media consumption (Clayman et al., 2010). In addition, other characteristics such as education, age, health insurance status, and immigrant status also contribute to language media preferences (Cheong, 2007). Second, the study sample included ad airings from DPOs, which were solely found in Spanish-speaking ads. Those discount plans are neither ACA-compliant nor have adequate coverage. We could not document these ads systematically because of lower interrater reliability of these variables, but our study sample also included some airings for short-term limited duration insurance and health care sharing ministries (Perez-Sanz & Tait, 2020). The existence of marketing for such products raises concerns that uninsured or underinsured consumers could enroll in an inadequate plan that could negatively impact their financial situation (Palanker & Volk, 2021). Third, our data feature ad airings on broadcast television and national cable, but do not include ad airings on local cable, nor advertisements that would have appeared during this time period on non-TV media, such as digital ads, billboards, radio spots, or print ads. Fourth and finally, while we can make hypotheses about potential exposure to information based on the content and volume of ad airings, we are not actually measuring the effects of ad exposure on consumers. Future research should examine the effects of ad exposure on enrollment and assess how messaging may differ across geographic regions.

Acknowledging the current context, COVID-19 has impacted the health of many individuals living in the United States and their access to health insurance. In response, the Biden administration created a special enrollment period for eligible individuals and families from February 15 to May 15, 2021, and CMS committed to spending 50 million on outreach and advertising efforts in 2021, including broadcast, digital, and earned media (Keith, 2021). This is particularly important because the cuts in advertisement funding have led to a dependency on privately sponsored ads, but our study demonstrates those ads in 2018 were not providing adequate information to consumers about their health insurance options. CMS is also providing an additional 2.3 million for 30 health insurance navigator organizations that work across 28 states with a federal marketplace; these organizations provide the public with guidance on financial assistance for health plans and aid in application completion and enrollment in Marketplace plans, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (Keith, 2021). As previously noted, health insurance navigator organizations serve as a key health insurance-related resource for the Spanish-speaking population and the highly uninsured population (Pollitz et al., 2020). CMS is also partnering with community stakeholders and media outlets to support outreach efforts and increase awareness of available health insurance options, especially for communities of color and groups who have less access to coverage (CMS, 2021). This combination of robust advertising featuring relevant Marketplace information with community-oriented resources like health insurance navigators can help reduce the potential for the further perpetuation of communication inequality (Viswanath, 2006).

Conclusion

With a renewed focus on health insurance enrollment and outreach at the federal level, this study offers implications for policy and research. First, this study demonstrates some drawbacks of relying heavily on private-sponsored messaging. With little reference to financial assistance, practically no reference to the government, and a focus on health plan benefits, audiences may be unlikely to learn important enrollment details or have the information necessary for political judgments of responsibility and accountability, thus influencing their perspectives on both health decisions and politics (Mettler, 2011). Second, future government-sponsored marketing and outreach should be attentive to providing enrollment-relevant details in Spanish-language broadcast ads, which are likely an influential source of information for the Latinx population. Third and finally, health communication research should evaluate not only public strategic communications (i.e., public service announcements and campaigns) but also examine the high volume of health-relevant content in advertisements created by the private sector, as these messages are an important part of the health messaging ecosystem but do not always support or reinforce the health-promoting messages from other sponsors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Paul Shafer, Jeff Niederdeppe, and Colleen Barry for their contributions to an early version of the coding instrument. We previously presented this paper at the 2021 APPAM conference in Austin, TX in March 2022.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation, grant number 1808-08181. Cynthia Pando is supported by grant (T32HD095134) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Appendix. Intercoder Reliability Values for Study Measures.

| Variable | Kappa | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Language spoken | ||

| English | 1.00 | Content is primarily delivered in English. |

| Spanish | 1.00 | Content is primarily delivered in Spanish. |

| Ad objective | ||

| Enrollment | 0.70 | Ads explicitly mention, audibly or visually, enrolling in a health insurance plan and may provide details about the plan(s). |

| Branding | 0.70 | Ads provide the insurer name and potentially their market (e.g., BlueCross Blue Shield of Illinois) but do not provide any appeal to enroll or any explicit information about plans. |

| Branding/public service announcement | 0.70 | Ads provide information to the viewer about issues or resources broader than the health plan. Examples include information presented in celebration of or to raise awareness about a particular cause (e.g., heart health). Message of a Branding/PSA ad will primarily focus on an issue or resource rather than on the insurer or the plan(s) they offer. |

| Sponsor type | ||

| Federal | 0.84 | Ad is either Medicare or CHIP. |

| State | 0.84 | Ads focus on enrollment in individual health insurance plans from a State based Marketplace or traditional Medicaid or CHIP. There may be also be mention of small business insurance run by the state. |

| Private | 0.84 | Any ad for an insurance company (can be for-profit or non-profit), insurance agency, broker, health care system, or managed care organization. |

| Private ad sponsor | ||

| Insurance company | 0.75 | Any seller of an insurance plan including for-profit companies and nonprofit organizations. |

| Insurance company & health system | 0.75 | Includes organizations like Kaiser Permanente, UPMC, etc. that offer insurance and operate health care facilities. |

| Insurance broker | 0.75 | Includes ads for a service that will connect a consumer to insurance. The company does not actually offer insurance. These may be individual brokers or agents, or they may be a company that matches consumers to a variety of plans from other companies. |

| Product appeals | ||

| Explicit reference to insurance | 0.79 | Ad explicitly mentions ‘insurance’ either audibly or visually. Note: visual mentions in the fine print or small text at the conclusion of the ad does not count as a mention. |

| Brand/loyalty | 0.62 | Ad makes a point to talk about a company’s reputation through mention of experience (example: more than 75 years), ranking (#1 trauma center), or public opinion (more people in your community trust us). Note: mention of “they [insurer/health system] know what to do” would not be coded as relevant. |

| Benefit appeals | ||

| Prescription drugs | 0.84 | Ad mentions access to prescription drugs benefit or a pharmacy benefit. |

| Nonmedical benefits | 0.77 | Ad mentions benefits to enrollees beyond medical care such as job assistance, childcare, and transportation. |

| Choice of doctor available | 0.83 | Ad mentions the opportunity to choose one’s doctor or presents visually or audibly a message that leaves the viewer with the impression that the plan includes the choice of doctor. |

| Access to specialists | 0.65 | Ad mentions or visualizes that the plan offers access to specialists without going through a primary care doctor or administrative approval. An ad that labels a health care provider as a specialist and talks about the plan or services would be coded as yes because this implies to the viewer that the plan offers access to specialists. |

| Wellness programs | 0.56 | Ad mentions a wellness program or coaching available to enrollees. Note: mention of non-specific supports to help you lead a healthy lifestyle would not be coded as a wellness program as these supports could take on various forms. General health insurance advocacy or help navigating benefits would also not count here. |

| ACA-policy related references | ||

| Financial assistance available/subsidies/tax credits available | 0.84 | Ad explicitly mentions financial assistance by way of a subsidy or tax credit. Note: plans that mention cash back to consumers or an enrollment bonus of sorts would not be coded as a mention. |

| Mention of “marketplace” | 0.74 | Ad explicitly, either audibly or visually, mentions a “Marketplace” for health insurance enrollment. Note: we are looking for references related to health insurance, and not marketplace for other consumer goods. |

| Mention of “government” | 0.65 | Ad explicitly, either audibly or visually, mentions government. Examples include “government-run health care” or “government requirements,” “government website,” or a government seal. |

| Mention of “ACA” or “Obamacare” | 1.00 | Ad explicitly, either audibly or visually, mentions the terms “Affordable Care Act,” “ACA,” or “Obamacare.” |

| Avoiding penalties | 0.66 | Ad explicitly mentions that enrollment in the plan will help the consumer to avoid a penalty. aNote: The individual mandate was repealed and took effect in 2019, so should not be part of health insurance advertising during this open enrollment period. |

| Lower cost plans cheaper/better than the ACA | 1.00 | Ad explicitly mentions a comparison between the plan advertised being cheaper than an ACA or Obamacare plan. |

Note. ACA = Affordable Care Act; CHIP = Children’s Health Insurance Program; UPMC = University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aizawa N, & Kim YS (2020). Government advertising in market-based public programs: Evidence from health insurance marketplace. National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.2139/ssrn.3434450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andalo P (2017, October 30). Big gains in Latino health coverage poised to slip during chaotic enrollment season. https://khn.org/Nzg0MDQ0

- Artiga S, Orgera K, & Damico A (2020). Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010–2018. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Changes-in-Health-Coverage-by-Race-and-Ethnicity-since-the-ACA-2010-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S, Tolbert J, & Orgera K (2020, November 6). Hispanic people are facing widening gaps in health coverage. https://www.kff.org/?p=494079

- Barry CL, Bandara SN, Arnold KT, Pintor JK, Baum LM, Niederdeppe J, Karaca-Mandic P, Fowler EF, & Gollust SE (2018). Assessing the content of television health insurance advertising during three open enrollment periods of the ACA. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 43(6), 961–989. 10.1215/03616878-7104392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel M, Grieco E, & Shearer E (2019, August 14). Older Americans, Black adults and Americans with less education more interested in local news. https://pewrsr.ch/31pGIZ2

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2017, August 31). CMS announcement on ACA navigator program and promotion for upcoming open enrollment. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announcement-aca-navigator-program-and-promotion-upcoming-open-enrollment

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021, February 12). 2021 special enrollment period for marketplace coverage starts on HealthCare.gov Monday, February 15. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021-special-enrollment-period-marketplace-coverage-starts-healthcarego-monday-february-15

- Cheong PH (2007). Health communication resources for uninsured and insured Hispanics. Health Communication, 21(2), 153–163. 10.1080/10410230701307188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong PH, Feeley TH, & Servoss T (2007). Understanding health inequalities for uninsured Americans: A population-wide survey. Journal of Health Communication, 12(3), 285– 300. 10.1080/10810730701266430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayman ML, Manganello JA, Viswanath K, Hesse BW, & Arora NK (2010). Providing health messages to Hispanics/Latinos: Understanding the importance of language, trust in health information sources, and media use. Journal of Health Communication, 15(Suppl. 3), 252–263. 10.1080/10810730.2010.522697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Terlizzi EP, Cha AE, & Martinez ME (2021). Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the national health interview survey, January–June 2020 (pp. 1–20). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur202102-508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus M (2013). The impact of mass media health communication on health decision-making and medical advice-seeking behavior of U.S. Hispanic population. Health Communication, 28(5), 525–529. 10.1080/10410236.2012.701584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores A, & Lopez MH (2018, January 11). Among U.S. Latinos, the Internet now rivals television as a source for news. https://pewrsr.ch/2ExyCCj

- Furtado KS, Kaphingst KA, Perkins H, & Politi MC (2016). Health insurance information-seeking behaviors among the uninsured. Journal of Health Communication, 21(2), 148–158. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1039678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galewitz P (2018, July 12). Outrageous or overblown? HHS announces another round of ACA navigator funding cuts. https://khn.org/ODU1MDYw

- Garfield R, Orgera K, & Damico A (2019). The uninsured and the ACA: A primer—Key facts about health insurance and the uninsured amidst changes to the Affordable Care Act (pp. 1–28). Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/6d1f02a/ [Google Scholar]

- Garrett B, & Gangopadhyaya A (2016). Who gained health insurance coverage under the ACA, and where do they live? (pp. 1–19). Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/86761/2001041-who-gained-health-insurance-coverage-under-the-aca-and-where-do-they-live.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Baum L, Barry CL, & Fowler EF (2018, November 8). Health insurance television advertising content and the fifth open enrollment period of the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. 10.1377/hblog20181107.968519 [DOI]

- Gollust SE, Fowler EF, & Niederdeppe J (2020). Ten years of messaging about the affordable care Act in advertising and news media: Lessons for policy and politics. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(5), 711–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Wilcock A, Fowler EF, Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Baum L, & Karaca-Mandic P (2018). TV advertising volumes were associated with insurance marketplace shopping and enrollment in 2014. Health Affairs, 37(6), 956–963. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith KN, Jones DK, Bor JH, & Sommers BD (2020). Changes in health insurance coverage, access to care, and income-based disparities among US adults, 2011–17. Health Affairs, 39(2), 319–326. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hero JO, Sinaiko AD, Kingsdale J, Gruver RS, & Galbraith AA (2019). Decision-making experiences of consumers choosing individual-market health insurance plans. Health Affairs, 38(3), 464–472. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom JK, Stillson C, Rosin R, Cahill R, Kruger E, & Grande D (2017). Effect of outreach messages on Medicaid enrollment. American Journal of Public Health, 107(Suppl. 1), S71– S73. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe O (2018, July 31). Bracing for an ACA enrollment season without navigators: Risks for consumers and the market [Center for Children & Families (CCF) of the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute]. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2018/07/31/bracing-for-an-aca-enrollment-season-without-navigators-risks-for-consumers-and-the-market/

- Isaacs SL (1996). Consumers’ information needs: Results of a national survey: A road map for providing consumers with better health plan information. Health Affairs, 15(4), 31–41. 10.1377/hlthaff.15.4.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca-Mandic P, Wilcock A, Baum L, Barry CL, Fowler EF, Niederdeppe J, & Gollust SE (2017). The volume of TV advertisements during the ACA’s first enrollment period was associated with increased insurance coverage. Health Affairs, 36(4), 747–754. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith K (2021, March 2). Latest on enrollment: Navigator funding, special enrollment period, and employer guidance. 10.1377/hblog20210302.229245 [DOI]

- Kelley MS, Su D, & Britigan DH (2016). Disparities in health information access: Results of a county-wide survey and implications for health communication. Health Communication, 31(5), 575–582. 10.1080/10410236.2014.979976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, & Lopez MH (2017, October 31). Use of Spanish declines among Latinos in major U.S. metros. https://pewrsr.ch/2yhit5k

- Mettler S (2011). The submerged state: How invisible government policies undermine American democracy. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson R, Tilipman N, Feher A, Li H, Yin W, & Menashe I (2022). Personalized telephone outreach increased health insurance take-up for hard-to-reach populations, but challenges remain: Study examines personalized telephone out-reach to increase take up of ACA marketplace enrollment. Health Affairs, 41(1), 129–137. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2012, January). Health care discount plans: State roles and regulation. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/health-care-discount-plans-state-roles.aspx

- Palanker D, & Volk J (2021). Misleading marketing of non-ACA health plans continued during COVID-19 special enrollment period. Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/mn7kgnhibn4kapb46tqmv6i7putry9gt [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C, & Dreas C (2011). Three things you thought you knew about U.S. Hispanic’s engagement with media … and why you may have been wrong (p. 4). Nielsen Media. https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/Nielsen-Hispanic-Media-US.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sanz S, & Tait M (2020, November 1). Buyer Beware: Non-ACA-compliant health plans may be marketed on TV to the newly uninsured as comprehensive insurance. https://perez767.medium.com/buyer-beware-non-aca-compliant-health-plans-may-be-marketed-on-tv-to-the-newly-uninsured-as-7d209e20e4fe

- Pintor JK, Alberto CK, Arnold KT, Bandara S, Baum LM, Fowler EF, Gollust SE, Niederdeppe J, & Barry CL (2020). Targeting of enrollment assistance resources in health insurance television advertising: A comparison of Spanish- Vs. English-language ads. Journal of Health Communication, 25(8), 605–612. 10.1080/10810730.2020.1818150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitz K, & Tolbert J (2020, October 13). Data note: Limited navigator funding for federal marketplace states. https://www.kff.org/9146a0c/

- Pollitz K, Tolbert J, Hamel L, & Kearney A (2020, August 7). Consumer assistance in health insurance: Evidence of impact and unmet need—Issue brief. https://www.kff.org/61104dd/

- Shafer PR, Anderson DM, Aquino SM, Baum LM, Fowler EF, & Gollust SE (2020). Competing public and private television advertising campaigns and marketplace enrollment for 2015 to 2018. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 6(2), 85–112. 10.7758/rsf.2020.6.2.04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons-Duffin S (2019, October 14). Trump is trying hard to thwart Obamacare. How’s that going? https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/10/14/768731628/trump-is-trying-hard-to-thwart-obamacare-hows-that-going [Google Scholar]

- Tichenor PJ, Donohue GA, & Olien CN (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 159–170. 10.1086/267786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert J, Orgera K, & Damico A (2020, November 6). Key facts about the uninsured population. https://www.kff.org/855449e/

- Viswanath K (2006). Public communications and its role in reducing and eliminating health disparities. In Examining the health disparities research plan of the national institutes of health: Unfinished business (1st ed.). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK57046/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, & Ackerson LK (2011). Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: A nationally-representative cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 6(1), Article e14550. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, & Finnegan JR Jr. (1996). The knowledge gap hypothesis: Twenty-five years later. Annals of the International Communication Association, 19(1), 187–228. 10.1080/23808985.1996.11678931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]