Abstract

Background:

Short or long interpregnancy interval (IPI) may adversely impact conditions for foetal development. Whether attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is related to IPI has been largely unexplored.

Objectives:

To examine the association between IPI and ADHD in a large, population-based Finnish study.

Methods:

All children born in Finland between 1991 and 2005 and diagnosed with ADHD (ICD-9 314x or ICD-10 F90.x) from 1995 to 2011 were identified using data from linked national registers. Each subject with ADHD was matched to 4 controls based on sex, date of birth, and place of birth. A total of 9564 subjects with ADHD and 34,479 matched controls were included in analyses. IPI was calculated as time interval between sibling birth dates minus the gestational age of the second sibling. The association between IPI and ADHD was determined using conditional logistic regression and adjusted for potential confounders.

Results:

Relative to births with an IPI of 24 to 59 months, those with the shortest IPI (<6 months) had an increased risk of ADHD (odds ratio [OR] 1.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12, 1.51) and the ORs for the longer IPI births (60–119 months and ≥120 months) were 1.12 (95% CI 1.02, 1.24) and 1.25 (95% CI 1.08, 1.45), respectively. The association of longer IPI with ADHD was attenuated by adjustment for maternal age at the preceding birth, and comorbid autism spectrum disorders did not explain the associations with ADHD.

Conclusions:

The risk of ADHD is higher among children born following short or long IPIs although further studies are needed to explain this association.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, birth spacing, foetal development, interpregnancy interval, pregnancy

1 |. BACKGROUND

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by developmentally inappropriate and impaired inattention, motor hyperactivity, and impulsivity.1 ADHD is associated with deficits in academic, social, and occupational functioning2 and is a risk factor for subsequent outcomes such as substance abuse3 and injuries,4 and results in substantial economic costs to society including those for health care, education, and lost productivity.5

While the high heritability6 of ADHD and its association with genomic factors such as copy number variants7 indicate an important role for genetics, the prenatal environment also appears to influence risk.8 Prenatal factors that have been previously associated with increased risk for ADHD diagnosis or symptoms include earlier gestational age and impaired foetal growth,9 lower maternal levels of thyroid hormone,10 higher maternal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone,11 and maternal smoking during pregnancy.12

Interpregnancy interval (IPI) is a potentially modifiable factor influencing the prenatal environment. Both short13–18 and long14,18 IPI have previously been associated with an increased risk for autism spectrum disorders (ASD), including within the Finnish population.14 Although the specific mediators responsible for this association are not certain, the consistency of these associations provides strong evidence supporting a role for the prenatal environment in the developmental aetiology of ASD.

According to two recent population-based register studies, 12% of patients with ADHD are also diagnosed with an ASD.19,20 Siblings of persons with ASD have an increased risk of diagnosis with ADHD independent of their own ASD diagnosis,21 and shared genetic risk loci for the disorders have been identified in genome-wide analyses.22 The comorbidity between the disorders, their shared genetic susceptibility, as well as overlap between risk factors such as male sex/gender and poor foetal growth9,23 suggest that these conditions may share other risk factors. One previous study reported modestly increased risk of ADHD associated with IPI <6 months with cousin-comparison and post-birth IPI analyses suggesting the presence of confounding by familial factors,24 but to our knowledge this relationship has not been examined in other populations. Therefore, we investigated the association between IPI and diagnosis with ADHD using a large case-control study nested within a national birth cohort in Finland.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data sources

Data used for the current study came from three linked national registries. The Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR)25 includes all inpatient diagnoses since 1967 and outpatient diagnoses in specialised public hospital units since 1998. The Finnish Medical Birth Register (FMBR) includes information on the pre-, peri-, and neonatal periods up to age 7 days for all births in Finland since 1987. The Finnish Central Population Register (CPR) contains basic information about Finnish citizens and foreign permanent residents.

2.2 |. Case-control selection

The study used case-control data obtained for prior analyses.9,19 Selection of ADHD cases and controls is illustrated in Figure S1. Cases were born between 1991 and 2005 in Finland and had ADHD diagnoses (International Classification of Disease [ICD]-9: 314x and ICD-10: F90.x) occurring after the age of 2 years listed in the FHDR between 1995 and 2011, and no diagnoses of severe or profound intellectual disability, which would result in uncertain reliability of the ADHD diagnosis. Each case was individually matched with up to four controls, if available, on biological sex, date of birth (±30 days) and place of birth, as identified from the Finnish CPR. Controls were excluded if they died or emigrated from Finland before the case was diagnosed; or if they had a diagnosis of ADHD, profound/severe intellectual disability, or conduct/oppositional disorder, the last of which may have indicated misdiagnosed ADHD. This resulted in 10,409 subjects with ADHD and 39,125 controls initially identified from the birth register who met our criteria for case and control definitions.

We further excluded participants whose mother could not be identified (n = 1), or who shared a mother with another participant (n = 2342). Remaining members of matched sets were excluded if the case or all matched controls had previously been excluded (total n = 2525). An additional 623 subjects were excluded because IPI could not be calculated due to missing data on gestational age or on the birth date of the preceding sibling; or due to conflicting information on maternal parity from different data sources. This resulted in a total of 9564 matched sets, each including one case with ADHD and up to 4 controls. Of these, 4354 matched sets had a first-born and 5210 matched sets had a case with defined IPI (see below).

2.3 |. Exposure

The exposure, IPI, was calculated using data from the FMBR and CPR. Sibships were identified for patients and matched controls, based on a shared biological mother, by linkage to the CPR. IPI was calculated in days as the difference between each participant’s birth date and the birth date of their preceding sibling, minus the gestational age of the participant at birth. IPI in months was categorised into 6 levels (<6, 6–11, 12–23, 24–59 [reference], 60–119, and ≥120) for consistency with prior work in this cohort14 and to capture intervals typically considered both short and long. First-born (no IPI) constituted a seventh category. Inclusion of the first-born category avoids the loss of subjects from strata where the case or all controls are first-born. Supplemental analyses categorised IPI by 6-month intervals to further examine the exposure-response relationship, and using categories recommended by Hutcheon et al26 to facilitate comparison across studies.

2.4 |. Covariates

Data on covariates were obtained from the FMBR and the FHDR. Covariates were selected as potential confounders based on previous evidence for an association with ADHD and/or IPI9,14 and on their theoretical roles as shared common causes or proxies for common causes of ADHD and variation in IPI.27 These included maternal and paternal age, education, and history of psychiatric diagnoses; and maternal parity, marital status, immigration status, and history of alcohol or substance use disorders. Parental psychiatric history and maternal alcohol/substance use disorders were defined as shown in Table 1. Maternal smoking during pregnancy, and infant low birthweight and preterm birth were examined as potential explanatory factors for the IPI-ADHD association. Information on maternal history of spontaneous/induced abortion was obtained from the FMBR and comorbid ASD diagnosis in the subjects was determined based on ICD-10 (F84.0; F84.5; F84.8/F84.9) in the FHDR. All covariates pertained to the subject pregnancy, except for the psychiatric diagnoses, which included any lifetime diagnosis.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of characteristics of cases with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and matched controls from Finnish Births, 1991–2005

| Covariate | Cases No. (%) |

Controls No. (%) |

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject sex | |||

| Female | 1538 (15.9) | 5628 (16.1) | -- |

| Male | 8152 (84.1) | 29 348 (83.9) | |

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| ≤19 | 626 (6.5) | 833 (2.4) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 20–29 | 5365 (55.4) | 17 517 (50.1) | 0.40 (0.36, 0.45) |

| 30–39 | 3438 (35.5) | 15 621 (44.7) | 0.29 (0.26, 0.32) |

| ≥40 | 261 (2.7) | 1005 (2.9) | 0.34 (0.29, 0.41) |

| Paternal age (years)b | |||

| ≤19 | 203 (2.2) | 199 (0.6) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 20–29 | 4037 (43.1) | 12 865 (37.2) | 0.31 (0.25, 0.38) |

| 30–39 | 4227 (45.1) | 18 131 (52.4) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.28) |

| ≥40 | 900 (9.6) | 3398 (9.8) | 0.26 (0.21, 0.32) |

| Maternal parityb | |||

| 0 | 4377 (45.4) | 13 793 (39.8) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 | 3043 (31.5) | 12 163 (35.1) | 0.78 (0.74, 0.82) |

| 2 | 1459 (15.1) | 5835 (16.8) | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) |

| ≥3 | 772 (8.0) | 2888 (8.3) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.92) |

| Parental psychiatric diagnosisc | |||

| Both parents affected | 832 (8.6) | 899 (2.6) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Only mother affected | 1488 (15.4) | 3136 (9.0) | 0.52 (0.47, 0.59) |

| Only father affected | 1445 (14.9) | 3410 (9.8) | 0.46 (0.41, 0.51) |

| Neither affected | 5925 (61.2) | 27 531 (78.7) | 0.23 (0.21, 0.26) |

| Maternal history of substance use disorderd | |||

| No | 7242 (74.7) | 30 886 (88.3) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 2448 (25.3) | 4090 (11.7) | 3.41 (3.06, 3.81) |

| Maternal marital statusb | |||

| Married/in relationship | 7916 (92.6) | 31 041 (96.8) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Single | 629 (7.4) | 1029 (3.2) | 2.53 (2.26, 2.82) |

| Maternal immigrant status | |||

| Immigrated | 231 (2.4) | 553 (1.6) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Did not immigrate | 9459 (97.6) | 34 423 (98.4) | 0.66 (0.56, 0.77) |

| Maternal education | |||

| College/bachelor univ degree | 1423 (14.7) | 7778 (22.2) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Master/licentiate/doctorate | 437 (4.5) | 3534 (10.1) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.76) |

| None after elementary | 2889 (29.8) | 5575 (15.9) | 2.94 (2.72, 3.16) |

| Vocational/secondary graduate | 4941 (51.0) | 18 089 (51.7) | 1.54 (1.44, 1.64) |

| Paternal educationb | |||

| College/bachelor univ degree | 902 (9.6) | 5467 (15.8) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Masters/licentiate/doctorate | 443 (4.7) | 3594 (10.4) | 0.74 (0.66, 0.84) |

| None after elementary | 3106 (33.2) | 6860 (19.8) | 2.79 (2.57, 3.04) |

| Vocational/secondary graduate | 4916 (52.5) | 18 672 (54.0) | 1.62 (1.50, 1.75) |

| Birthweight (g) | |||

| <2500 | 607 (6.3) | 894 (2.6) | 2.53 (2.28, 2.82) |

| ≥2500 | 9038 (93.7) | 33 778 (97.4) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||

| <37 | 759 (7.9) | 1582 (4.6) | 1.79 (1.64, 1.96) |

| ≥37 | 8854 (92.1) | 33 002 (95.4) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Based on unadjusted conditional logistic regression to account for matching.

Observations were missing data for the following covariates: paternal age, n = 706; maternal parity, n = 336; maternal marital status, n = 4051; paternal education, n = 706; birthweight, n = 349; gestational age, n = 469.

Lifetime ICD-10 diagnoses of F10-F99, excluding F70-F79; or the corresponding diagnoses based on the ICD-9 [291–316; excluding 293–294] and the ICD-8 [291–309; 292–294]. Substance abuse disorders (see below) were also excluded.

ICD-10: F10–19; ICD-9:291–292, 303–305; and ICD-8:291, 303, and 304).

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

To assess the association between IPI and ADHD, conditional logistic regression models were fit. The first model was unadjusted. A second model adjusted for the following potential confounders: parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education. Additional models addressed the role of parental age. To address confounding by maternal age at the birth preceding the IPI,26 a model was fit adjusted for this variable. First-born subjects were excluded because there is no preceding birth. To examine the association between IPI and ADHD not attributable to the parental ages at the subject birth, which may be clinically relevant to the assessment of offspring risk, maternal and paternal age at the subject birth were added to the initial adjusted model.

Effect modification of the associations between IPI and ADHD by comorbid diagnosis of ASD in the case was examined on the multiplicative scale by including terms for comorbid ASD and for comorbid ASD by IPI interactions in an adjusted model. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

2.6 |. Sensitivity analysis

A series of sensitivity analyses were performed as follows: (a) maternal marital status was added to a model including the subset of observations for which this information was available, in order to additionally test for potential confounding; (b) a model was fit excluding subjects who were first-born, to assess the impact of including this group; (c) to test for confounding by maternal parity, a model was fit including this variable; (d) because the IPI is measured between two livebirth pregnancies, women experiencing a miscarriage or abortion during this interval will have spent some of the time pregnant and may have different exposures or physiologic parameters than women who are non-pregnant during the interval. To address the possibility that this influenced our results, we fit a model restricted to the observations with no prior reported miscarriage or abortion; and (e) to test whether the association between IPI and ADHD was attributable to low birthweight, preterm birth, or maternal smoking during pregnancy, dichotomous terms for these variables were added to the model.

2.7 |. Missing data

Missing data for the potential confounders were addressed with complete case analysis; data were missing on one or more of these variables for 1.5% of observations.

2.8 |. Ethics approval

The study received approval from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland and from the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

3 |. RESULTS

Characteristics of the cases and controls are shown in Table 1. Subjects were 84.1% male. Cases with ADHD were more likely to have younger mothers and fathers; to be first-born; to have a history of parental psychiatric diagnoses in one or both parents; to have mothers with a history of substance use, who were single, or had immigrated to Finland; to have lower levels of parental education; and to be born low birthweight or preterm.

Among all non-first-born controls, the median (interquartile range) IPI was 25 (14–47) months. IPI was positively correlated with the ages of both parents, but inversely related to the level of parental education. Maternal smoking, history of substance use, single marital status, and having immigrated to Finland were each associated with longer mean IPI. Median IPI was longer for third-born (maternal parity 2) controls than for those born second or fourth and later in the sibship. Among strata defined by parental history of psychiatric diagnosis, both parents having a diagnosis were associated with the longest median IPI (Table S1).

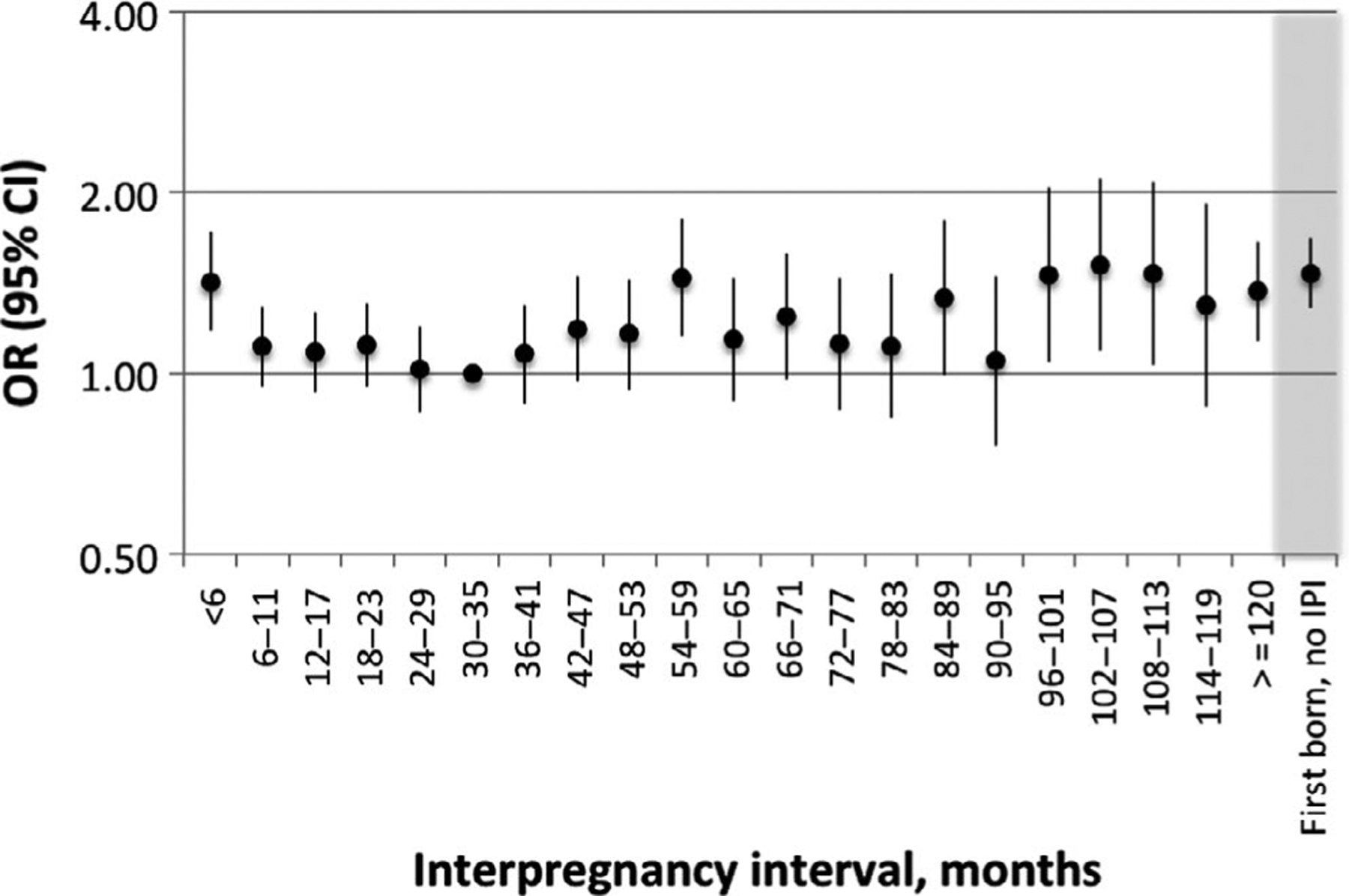

Table 2 shows odds ratios (OR) for the association between IPI and ADHD. Relative to births with an IPI of 24–59 months, those with the shortest IPI (<6 months) had an increased risk of ADHD (OR 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.12, 1.51) in covariate-adjusted models, while the adjusted ORs for longer IPI births (60–119 months and ≥120 months) were 1.12 (95% CI 1.02, 1.24), and 1.25 (95% CI 1.08, 1.45), respectively. First-born subjects also had increased odds of ADHD diagnosis relative to those born following an IPI of 24–59 months (adjusted OR 1.34, (95% CI 1.25, 1.44). When IPI was categorised in 6-month intervals throughout the full range of values, the lowest risk of ADHD was seen among those with IPI 30–35 months and dose-response patterns were evident with both decreasing and increasing IPI (Figure 1). Results from the models applying additional adjustments or restrictions and those using alternative categories for IPI were consistent with those presented in Table 2 and Tables S2 and S3.

TABLE 2.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between interpregnancy interval (IPI) and ADHD in Finnish births, 1991–2005

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpregnancy interval (mo) | ADHD cases N (%) |

Controls N (%) |

Unadjusted (n = 44 043) |

Adjusteda (n = 43 401) |

| <6 | 305 (3.2) | 859 (2.5) | 1.54 (1.33, 1.77) | 1.30 (1.12, 1.51) |

| 6–11 | 744 (7.8) | 3131 (9.1) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) |

| 12–23 | 1320 (13.8) | 5947 (17.2) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) |

| 24–59 | 1646 (17.2) | 7052 (20.5) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 60–119 | 872 (9.1) | 2862 (8.3) | 1.30 (1.18, 1.43) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) |

| ≥120 | 323 (3.4) | 899 (2.6) | 1.54 (1.34, 1.77) | 1.25 (1.08, 1.45) |

| First-born, no IPI | 4354 (45.5) | 13 729 (39.8) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.45) | 1.34 (1.25, 1.44) |

Adjusted for: parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education.

FIGURE 1.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between interpregnancy interval (IPI) and ADHD in Finnish births, 1991–2005. Estimated using a conditional logistic regression model adjusted for parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education

Table 3 shows ORs for the association between IPI and ADHD adjusted for parental ages. When the model is adjusted for the maternal age at the birth preceding the IPI, the association with short IPI (<6 months) was strengthened (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.12, 1.60) while that with long IPI (≥120 months) was attenuated (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.97, 1.36). Adjustment for maternal and paternal ages at the subject birth, conversely, moderately reduced the magnitude of association for IPI <6 months (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.07, 1.45) and strengthened that for IPI ≥120 months (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.18, 16.0).

TABLE 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between interpregnancy interval (IPI) and ADHD in Finnish births, 1991–2005, adjusted for parental ages

| Age at prior birtha(n = 16 096) | Age at current birthb(n = 43 401) | |

|---|---|---|

| IPI | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| <6 mo | 1.34 (1.12, 1.60) | 1.25 (1.07, 1.45) |

| 6–11 mo | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.08) |

| 12–23 mo | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) |

| 24–59 mo | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 60–119 mo | 1.08 (0.97, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.30) |

| ≥120 mo | 1.15 (0.97, 1.36) | 1.37 (1.18, 1.60) |

| First born, no IPI | Excluded | 1.23 (1.15, 1.32) |

Adjusted for maternal age at previous birth. Also adjusted for parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education.

Adjusted for maternal age and paternal age at the current birth. Also adjusted for parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education.

Table 4 provides estimates for the association between IPI and ADHD by the presence or absence of a comorbid ASD diagnosis in the case. Twelve per cent of cases with ADHD (1171 of 9690) also had a comorbid diagnosis of ASD. The odds of ADHD with ASD were decreased among subjects with IPI <6 months (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14, 0.83) and not associated with other IPI categories. Similar to the overall results, the odds of ADHD without ASD were increased for IPIs <6 months (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.13, 1.55) and ≥120 months (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.00, 1.38). Tests of heterogeneity indicated that the association between IPI <6 months and ADHD differed for cases with versus without ASD (Pinteraction = 0.003).

Table 4.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between interpregnancy interval (IPI) and ADHD, stratified by the comorbid diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the case

| Interpregnancy interval (mo) | Comorbid ASD diagnosis in the case (N = 5238) | No ASD diagnosis in the case (N = 38 163) | P interaction b |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ||

| <6 | 0.34 (0.14, 0.83) | 1.32 (1.13, 1.55) | <.01 |

| 6–11 | 0.80 (0.42, 1.50) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.11) | .49 |

| 12–23 | 0.62 (0.37, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | .07 |

| 24–59 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | -- |

| 60–119 | 0.76 (0.41, 1.39) | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | .23 |

| ≥120 | 1.24 (0.51, 3.01) | 1.18 (1.00, 1.38) | .91 |

| First-born, no IPI | 1.06 (0.69, 1.64) | 1.29 (1.20, 1.39) | .38 |

Adjusted for parental psychiatric diagnosis, maternal history of substance abuse, maternal immigration, maternal education, and paternal education.

Pinteraction, P-value for interaction.

4 |. COMMENT

4.1 |. Principal findings

This population-based study, drawn from all births in Finland between 1991 and 2005, provides evidence that IPI of <6 or ≥60 months is associated with an increased risk of ADHD among second- and later-born children. The highest risk of ADHD was found among children born following IPI < 6 months, and the association with IPI ≥ 120 months was attenuated by adjustment for maternal age at the preceding birth. This association was not accounted for by comorbid diagnosis with ASD, a condition that has previously been associated with short and long IPI. First-born children were also at increased risk of ADHD relative to those born following an IPI of 24–59 months.

4.2 |. Strengths of the study

A strength of this study was the use of national registry data with a large sample size and an unselected population. While this method does not allow for individual diagnostic confirmation, a validation study showed that 88% of subjects with a registry-based ADHD diagnosis met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD based on a parental interview.20 Another important strength of the study was the use of registry data linked by personal identification numbers to accurately match siblings. This should have resulted in low misclassification with respect to IPI. Misclassification of IPI may occur due to incorrect estimation of gestational age; this would particularly impact shorter IPI pregnancies, where the relative impact on the estimation of IPI would be greater. However, this is expected to be non-differential with respect to the outcome and would have biased estimates of association for shorter IPI pregnancies towards the null.

4.3 |. Limitations of the data

Our study relied on the FHDR to identify ADHD cases. While the diagnosis of ADHD in Finland is typically based on assessment by a specialist in psychiatry or neurology in public outpatient services, we likely missed less severe cases who did not utilise specialised services. The cumulative incidence of ADHD identified through the FHDR by age 21 for children born 1991–1993 was 2.3%,19 somewhat lower than the estimated prevalence of 3.4% based on recent metaanalyses.8 Therefore, our findings may not be representative of less severe cases of ADHD.

As with any observational study, we cannot rule out the possibility of bias due to unmeasured confounding. For example, we did not have the data on history of stillbirth or paternal age at the prior pregnancy as confounders. Based on the E-value,28 an unmeasured confounder would have to be associated with both IPI and ADHD with a risk ratio of at least 1.92 each to fully explain the observed OR of 1.30 for the association of IPI < 6 months with ADHD; or would have to be associated with IPI and ADHD by a risk ratio of at least 1.81 each to explain away the observed OR of 1.25 for the association of IPI ≥ 120 months with ADHD. For the lower limits of the confidence intervals, the corresponding values for the unmeasured confounders are 1.49 or 1.37, respectively. We could not compare multiple IPIs within the same woman. Finally, we were unable to examine subsets of ADHD or clinical characteristics for potential heterogeneity in the relationship with IPI. This may be a fruitful area for future research.

4.4 |. Interpretation

The mechanisms explaining the observed associations may differ for short versus long IPI. Short IPI has been linked to nutritional depletion including lower levels of maternal folate (reviewed by Conde-Agudelo et al29), and reduced levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids.30 Maternal intake of these nutrients has also been linked to symptoms of ADHD. Lower maternal red blood cell folate in early pregnancy has been associated with higher levels of child hyperactivity,31 while maternal consumption of oily fish (the major dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids) during early pregnancy was related to a reduced risk of hyperactivity among 9-year-old children.32 Decreased IPI has also been linked to immunologic alterations, including increased recurrence of group B streptococci colonisation,33 altered cervical cytokine concentrations,34 and unresolved inflammation from the prior pregnancy.35 Supporting a potential immune-related aetiology, maternal genitourinary infection has been associated with increased risk of ADHD diagnosis in a number of studies.36–38 Recent systematic reviews focused on high-resource settings suggest increased risks of preterm birth and small for gestational age following short IPI,39 as well as obstetric complications such as gestational diabetes.40 Though earlier gestational age and impaired foetal growth were previously associated with ADHD,9 adjustment for low birthweight and preterm birth did not appreciably alter these findings.

On the other hand, long IPI may be related to underlying infertility or associated with fertility treatment. Increased risks of ADHD have been reported in the offspring of women with fertility problems41 and those using ovulation induction.42 Adjustment for maternal age at the preceding birth in the subjects with this information available resulted in the attenuation of the OR and a 95% CI including 1.0, suggesting that maternal age at the preceding birth is a common cause or proxy for a common cause of long IPI and ADHD. An association of younger maternal age at first birth with an increased risk for offspring ADHD was previously found to be primarily due to genetic confounding43; here maternal age at the preceding birth may similarly be a marker for genetic risk for ADHD.

Both short and long IPI have been associated with a higher prevalence of unintended (unwanted or mistimed) pregnancy.44 Women with an unintended pregnancy are more likely to smoke, to use alcohol or illicit drugs, to delay prenatal care, and are less likely to take prenatal vitamin supplements45,46 than are women with intended pregnancies. Multivitamin use during early pregnancy has been associated with a decreased risk of ADHD diagnosis and treatment47 while prenatal maternal alcohol48 and illicit drug use49 have been associated with increased levels of ADHDrelated behaviour. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is also associated with offspring ADHD; however, this may be largely explained through confounding by family-level factors.50,51 In the current study, adjustment for maternal smoking during pregnancy had little impact on the results, suggesting that it did not explain the observed association.

Associations of ASD with both short and long IPI have previously been observed in this population.14 Nonetheless, it is unlikely that ASD accounts for the relationship that we observed between IPI and ADHD given that the relationship between ADHD without comorbid ASD diagnosis was similar to that for an ADHD diagnosis overall. This suggests that the neurodevelopmental implications of IPI are not specific to autism and may potentially be broad, though this remains to be examined. Short IPI has previously been linked to increased risk of schizophrenia.52–55 Closely spaced births have been associated with poorer performance on math and reading achievement tests56; lower verbal intelligence test scores57; and poorer performance on academic skills tests.58 However, these studies are substantially limited by small sample sizes, selected populations, and limited adjustment for confounding. Therefore, further elucidating the specific developmental domains that may be impacted by IPI remains an important research goal.

The protective association between short IPI and ADHD with ASD should be interpreted with caution given the smaller sample size of this stratum and the exclusion of subjects with severe/profound intellectual disability, a comorbidity often present with ASD. Thus, our cases with ADHD and ASD are unlikely to be directly comparable to ASD cases identified in other studies. Nonetheless, this underscores the importance of considering heterogeneity within both of these disorders. In fact, when ASD was examined previously by sub-types, IPI < 12 months was associated with increased risk of childhood autism and of pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), but not of Asperger syndrome.14

Our findings differed from those of a prior report in which cousin-comparison and post-birth IPI analyses suggested that an observed increased risk of ADHD with IPI < 6 months was due primarily to confounding by familial factors.24 This may be related to methodological differences or may reflect true differences between populations.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that IPI < 6 months or ≥ 60 months are associated with an increased risk of ADHD in the offspring. This adds to the existing evidence that both short and long IPI are associated with neurodevelopmental risks and that these risks apply to outcomes more broadly than the previously well-documented associations with ASD. Additional investigation should be conducted to confirm this association and to elucidate the mechanisms behind it.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

Study question

Is the interpregnancy interval (IPI) preceding a birth related to the risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the offspring?

What’s already known

Short or long IPI may affect the conditions for foetal development and have consistently been associated with increased risk of autism spectrum disorders. Whether ADHD is also related to IPI has been largely unexplored.

What this study adds

Children born following interpregnancy intervals of <6 or ≥60 months were at increased risk for ADHD diagnosis relative to those born following an IPI of 24–59 months. Comorbid autism spectrum disorders do not explain these associations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Finnish Academy and from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES028125).

Funding information

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Grant/Award Number: R01ES028125; Finnish Academy

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigg JT. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adverse health outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(2):215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood Psychiatric Disorders as Risk Factor for Subsequent Substance Abuse: A MetaAnalysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming M, Fitton CA, Steiner MFC, et al. Educational and health outcomes of children treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(7):e170691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doshi JA, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, et al. Economic impact of childhood and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(10): 990–1002 e1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiat. 2005;57(11):1313–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams NM, Zaharieva I, Martin A, et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1401–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thapar A, Cooper M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1240–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sucksdorff M, Lehtonen L, Chudal R, et al. Preterm birth and poor fetal growth as risk factors of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):e599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modesto T, Tiemeier H, Peeters RP, et al. Maternal mild thyroid hormone insufficiency in early pregnancy and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakkila F, Mannisto T, Pouta A, et al. The impact of gestational thyroid hormone concentrations on ADHD symptoms of the child. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):E1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langley K, Rice F, van den Bree MB, Thapar A. Maternal smoking during pregnancy as an environmental risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder behaviour. A review. Minerva Pediatr. 2005;57(6):359–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheslack-Postava K, Liu K, Bearman PS. Closely spaced pregnancies are associated with increased odds of autism in California sibling births. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheslack-Postava K, Suominen A, Jokiranta E, et al. Increased risk of autism spectrum disorders at short and long interpregnancy intervals in Finland. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1074–1081 e1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coo H, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Lam YM, Brownell M, Flavin MP, Roos LL. The association between the interpregnancy interval and autism spectrum disorder in a Canadian cohort. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(2):e36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durkin MS, DuBois LA, Maenner MJ. Inter-Pregnancy Intervals and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a Population-Based Study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(7):2056–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunnes N, Suren P, Bresnahan M, et al. Interpregnancy interval and risk of autistic disorder. Epidemiology. 2013;24(6):906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zerbo O, Yoshida C, Gunderson EP, Dorward K, Croen LA. Interpregnancy interval and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joelsson P, Chudal R, Gyllenberg D, et al. Demographic characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity of children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD in specialized healthcare. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47(4):574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen CM, Steinhausen HC. Comorbid mental disorders in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a large nationwide study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2015;7(1):27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jokiranta-Olkoniemi E, Cheslack-Postava K, Sucksdorff D, et al. Risk of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders among sibings of probands with autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1371–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampi KM, Lehtonen L, Tran PL, et al. Risk of autism spectrum disorders in low birth weight and small for gestational age infants. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):830–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, et al. Outcome-dependent associations between short interpregnancy interval and offspring psychological and educational problems: a population-based quasi-experimental study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(4):1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sund R Quality of the finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutcheon JA, Moskosky S, Ananth CV, et al. Good practices for the design, analysis, and interpretation of observational studies on birth spacing and perinatal health outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):O15–O24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(2):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Castano F, Norton MH. Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health: a systematic review of causal mechanisms. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43(2):93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makrides M, Gibson RA. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1 Suppl):307S–311S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlotz W, Jones A, Phillips DI, Gale CR, Robinson SM, Godfrey KM. Lower maternal folate status in early pregnancy is associated with childhood hyperactivity and peer problems in offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(5):594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gale CR, Robinson SM, Godfrey KM, Law CM, Schlotz W, O’Callaghan FJ. Oily fish intake during pregnancy–association with lower hyperactivity but not with higher full-scale IQ in offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(10):1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng PJ, Chueh HY, Liu CM, Hsu JJ, Hsieh TT, Soong YK. Risk factors for recurrence of group B streptococcus colonization in a subsequent pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shree R, Simhan HN. Interpregnancy Interval and Anti-inflammatory Cervical Cytokines among Women with Previous Spontaneous Preterm Birth. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(7):689–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shachar BZ, Lyell DJ. Interpregnancy interval and obstetrical complications. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67(9):584–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mann JR, McDermott S. Are maternal genitourinary infection and pre-eclampsia associated with ADHD in school-aged children? J Atten Disord. 2011;15(8):667–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Werenberg Dreier J, Nybo Andersen AM, Hvolby A, Garne E, Kragh Andersen P, Berg-Beckhoff G. Fever and infections in pregnancy and risk of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(4):540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva D, Colvin L, Hagemann E, Bower C. Environmental risk factors by gender associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):e14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahrens KA, Nelson H, Stidd RL, Moskosky S, Hutcheon JA. Short interpregnancy intervals and adverse perinatal outcomes in high-resource settings: An updated systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):O25–O47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutcheon JA, Nelson HD, Stidd R, Moskosky S, Ahrens KA. Short interpregnancy intervals and adverse maternal outcomes in high-resource settings: An updated systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):O48–O59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svahn MF, Hargreave M, Nielsen TS, et al. Mental disorders in childhood and young adulthood among children born to women with fertility problems. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(9):2129–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bay B, Mortensen EL, Kesmodel US. Assisted reproduction and child neurodevelopmental outcomes: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):844–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Maternal age at childbirth and risk for ADHD in offspring: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(6):1815–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheslack Postava K, Winter AS. Short and long interpregnancy intervals: correlates and variations by pregnancy timing among U.S. women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han JY, Nava-Ocampo AA, Koren G. Unintended pregnancies and exposure to potential human teratogens. Birth Defects Res A. 2005;73(4):245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Virk J, Liew Z, Olsen J, Nohr EA, Catov JM, Ritz B. Pre-conceptual and prenatal supplementary folic acid and multivitamin intake, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders: A study based on the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC). Nutr Neurosci. 2017;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eilertsen EM, Gjerde LC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, et al. Maternal alcohol use during pregnancy and offspring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a prospective sibling control study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(5):1633–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sagiv SK, Epstein JN, Bellinger DC, Korrick SA. Pre- and postnatal risk factors for ADHD in a nonclinical pediatric population. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(1):47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skoglund C, Chen Q, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD in offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langley K, Heron J, Smith GD, Thapar A. Maternal and paternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of ADHD symptoms in offspring: testing for intrauterine effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(3):261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gunawardana L, Smith GD, Zammit S, et al. Pre-conception inter-pregnancy interval and risk of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):338–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haukka JK, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J. Family structure and risk factors for schizophrenia: case-sibling study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smits L, Pedersen C, Mortensen P, van Os J. Association between short birth intervals and schizophrenia in the offspring. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westergaard T, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Exposure to prenatal and childhood infections and the risk of schizophrenia: suggestions from a study of sibship characteristics and influenza prevalence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(11):993–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marjoribanks K Birth order, age spacing between siblings, and cognitive performance. Psychol Rep. 1978;42(1):115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lancer I, Rim Y. Intelligence, family size and sibling age spacing. Personality Individ Differ. 1984;5(2):151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chittenden EA, Foan MW, Zweil DM, Smith JR. School achievement of first-and second-born siblings. Child Dev. 1968;1223–1228. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.