Abstract

Prevention programs are a key method to reduce the prevalence and impact of mental health disorders in childhood and adolescence. Caregiver participation engagement (CPE), which includes caregiver participation in sessions as well as follow-through with homework plans, is theorized to be an important component in the effectiveness of these programs. This systematic review aims to (1) describe the terms used to operationalize CPE and the measurement of CPE in prevention programs, (2) identify factors associated with CPE, (3) examine associations between CPE and outcomes, and (4) explore the effects of strategies used to enhance CPE. Thirty-nine articles representing 27 unique projects were reviewed. Articles were included if they examined CPE in a program that focused to some extent on preventing child mental health disorders. There was heterogeneity in both the terms used to describe CPE and the measurement of CPE. The majority of projects focused on assessment of caregiver home practice. There were no clear findings regarding determinants of CPE. With regard to the impact of CPE on program outcomes, higher levels of CPE predicted greater improvements in child and caregiver outcomes, as well as caregiver-child relationship quality. Finally, a small number of studies found that motivational and behavioral strategies (e.g., reinforcement, appointment reminders) were successful in promoting CPE. This review highlights the importance of considering CPE when developing, testing, and implementing prevention programs for child mental health disorders. Increased uniformity is needed in the measurement of CPE to facilitate a better understanding of determinants of CPE. In addition, the field would benefit from further evaluating strategies to increase CPE as a method of increasing the potency of prevention programs.

Keywords: Caregiver, Participation, Engagement, Mental health, Children, Prevention

Introduction

The occurrence of mental health (MH) disorders in childhood is associated with poor educational, vocational, and health outcomes, and can place children and adolescents (hereafter referred to as children) at a higher risk of experiencing additional MH issues throughout their lifetime (Currie et al., 2010; Fryers & Brugha, 2013; Jaycox et al., 2009). Compounding these risks, a large number of children with MH disorders do not receive the appropriate treatment, increasing the likelihood of long-term negative outcomes (Whitney & Peterson, 2019). Child MH prevention programs have been developed to interrupt the long-term and cascading negative individual and societal outcomes associated with child MH disorders such as poor school performance, later mental health and substance use disorders, and high treatment costs (Caldwell, 2019; Sawyer et al., 2015; Skeen et al., 2019; Wilson & Lipsey, 2007).

In general, MH prevention programs fall into three levels of care: (1) universal (or primary) interventions, which target the general population; (2) selective (or secondary) interventions, targeting those at higher than average risk of developing MH disorders; and (3) indicated (or tertiary) interventions, which target those identified at high risk with already detectable symptoms (Institute of Medicine, 1994). Meta-analytic reviews of child MH prevention programs have demonstrated their positive impact on a range of target problems (e.g., disruptive behaviors, depression) in multiple service settings (e.g., community-based and school-based programs) (e.g., Beelmann & Lösel, 2006; Gillham et al., 2006; Horowitz & Garber 2006; Wilson & Lipsey, 2007). These programs are designed to prevent child MH disorders by modifying children’s risk exposure and strengthening their coping mechanisms.

Caregiver involvement has been shown to be a critical component in treatments for child MH concerns, with meta-analyses showing that treatments that involve caregivers have larger effect sizes than treatments focused only on the individual child (Dowell & Ogles, 2010; Sun et al., 2018). Therefore, it is important to understand the role of caregiver engagement in programs designed to prevent child MH disorders.

Caregiver engagement is a broad construct, and has been conceptualized numerous ways in the child MH treatment literature (e.g., Becker et al., 2015; Piotrowska et al., 2017). Most simply, engagement can be organized into attitudinal and behavioral engagement (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Staudt, 2007). The attitudinal component of engagement is the perception that the benefits of a program or treatment outweigh its costs (e.g., “buy-in;” Becker et al., 2015; Staudt, 2007). The behavioral component of engagement consists of three elements: (1) seeking or initiating help by enrolling in a program or service; (2) attending the program or service; and (3) participating actively and meaningfully in the program or service, both in interactions with providers and by following through with recommendations (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Staudt, 2007). This third component, referred to as caregiver participation engagement (CPE; Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015), includes participating in sessions by sharing opinions, asking questions, and providing a point of view on a problem or solution, as well as through active involvement in therapeutic activities such as role plays and games. CPE also includes caregiver follow-through with homework plans such as changing one’s own parenting behavior, serving as a co-provider to continue the delivery of program strategies at home, and/or supporting the child’s behavior change efforts.

Prevention scientists have emphasized the significance of CPE given the importance of caregivers interacting dynamically with program material and other participants (e.g., Berkel et al., 2011; Coatsworth et al., 2017). However, overall there is variability in the terms used both within the child MH prevention literature as well in the broader MH field. The numerous terms used to describe CPE make it difficult to characterize the landscape of CPE within child MH. There is also variability in how CPE is measured, which limits our understanding of CPE in MH prevention efforts. Although behavioral engagement is conceptualized as a complex array of components, program enrollment and attendance are most frequently utilized as a proxy for the entire construct of behavioral engagement. However, the active participation component of behavioral engagement is also important and does not conceptually overlap entirely with attendance. Some caregivers may attend frequently but fail to engage with or apply the curriculum. Alternatively, some caregivers may attend infrequently but learn the curriculum content because they actively engaged in the sessions they attended and implemented practice skills at home. Indeed, researchers have found that participation in program activities have effects above and beyond that of attendance alone (Berkel et al., 2018). Little is known about the role CPE may play in child MH prevention programs. Though preventive parent training programs for caregivers have become increasingly available, many studies note difficulties engaging caregivers (Morawska & Sanders, 2006), underscoring the need to further characterize the knowledge base regarding CPE within this service type.

Several factors spanning multiple levels (e.g., family, service context) can make it more difficult to garner CPE in prevention programs. For example, caregivers from distressed and disadvantaged families, the primary target of many prevention programs, are also often populations that can be the most difficult to engage and to have participate in intervention activities (Gardner et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2014). Related family level factors that may affect CPE include the availability of transportation, childcare, and financial resources (Garvey et al., 2006; Nix et al., 2009), as well as the perceived relevance of the program and concerns about stigma (Finan et al., 2020). More broadly, a high degree of existing stressors (e.g., limited resources, high crime rate neighborhood, interparental conflict, acculturative differences) may reduce caregivers’ capacity to enroll in, attend, and/or participate in prevention programs (Dadds & McHugh, 1992; Mauricio et al., 2018; McKay et al., 1996; Prinz & Miller, 1994; Winslow et al., 2016). Thus, the very factors that can make a prevention program important for a child may also inhibit a caregiver’s ability to engage with the program.

In terms of service context, the very nature of prevention programs can impact caregivers’ engagement and participation in such services. In contrast to MH treatment services, in which help-seeking is often a result of an obvious problem or concern and thus can be conceptualized as the foundation of caregivers’ overall behavioral engagement (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015), prevention programs aim to address disorders before they manifest. Therefore, help-seeking may be a different process in prevention programs, which in turn may influence CPE. In addition, the format of such programs may also detract from CPE. For example, prevention programs are often more didactic in nature than treatment and are often delivered in a group format, with other group members’ participation impacting CPE (Nix et al., 2009).

Given the complexities of the populations served by prevention programs and the challenges associated with perceived need and program characteristics, the prevention science field has pointed to various aspects of CPE as important factors to address when implementing prevention programs in community settings. For example, Berkel et al. (2011) identify participant responsiveness, which includes participant attendance and program satisfaction with CPE, as an important dimension of prevention program implementation. Dane and Schneider (1998) conceptualize implementation fidelity, or the degree to which a prevention program is delivered as intended, as including CPE. The Translation Science to Population Impact Framework (TSci Impact; Spoth et al., 2013) highlights the need to understand factors that influence engagement in prevention programs, and emphasizes the importance of developing implementation strategies to facilitate caregiver engagement overall, including CPE. Further understanding of the existing knowledge, including the collection of terms and forms of CPE examined and associations with other key factors, represents a key first step to such efforts.

The current study systematically reviews the literature on CPE in MH prevention programs for children (see Online Resource 1: PRISMA Checklist). Specific aims are to (1) describe the terms used to operationalize CPE and the measurement of CPE in child MH prevention programs, (2) identify factors associated with CPE, (3) examine associations between CPE and program outcomes, and (4) explore the effects of strategies used to enhance CPE. In the present review, we chose to focus only on studies where the authors explicitly state that the target of the intervention was to prevent youth mental health problems. Although other important child-focused prevention or early intervention areas such as child abuse, alcohol/drug use, and autism-specific intervention can have secondary effects on mental health, the nature of the circumstances affecting these populations are different, the consumers are different, and the providers are often different. In order to be able to appropriately synthesize findings specific to mental health prevention studies, we excluded studies in which the program/intervention’s stated target was to reduce general “risk” for poor outcomes with no mention of mental health outcomes as a focus (whether proximal or distal). The current review represents an important extension of prior work examining CPE in child MH treatment services (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015) to support comprehensive understanding of the role of CPE in the implementation and effectiveness of child MH programs overall.

Method

Search Strategy

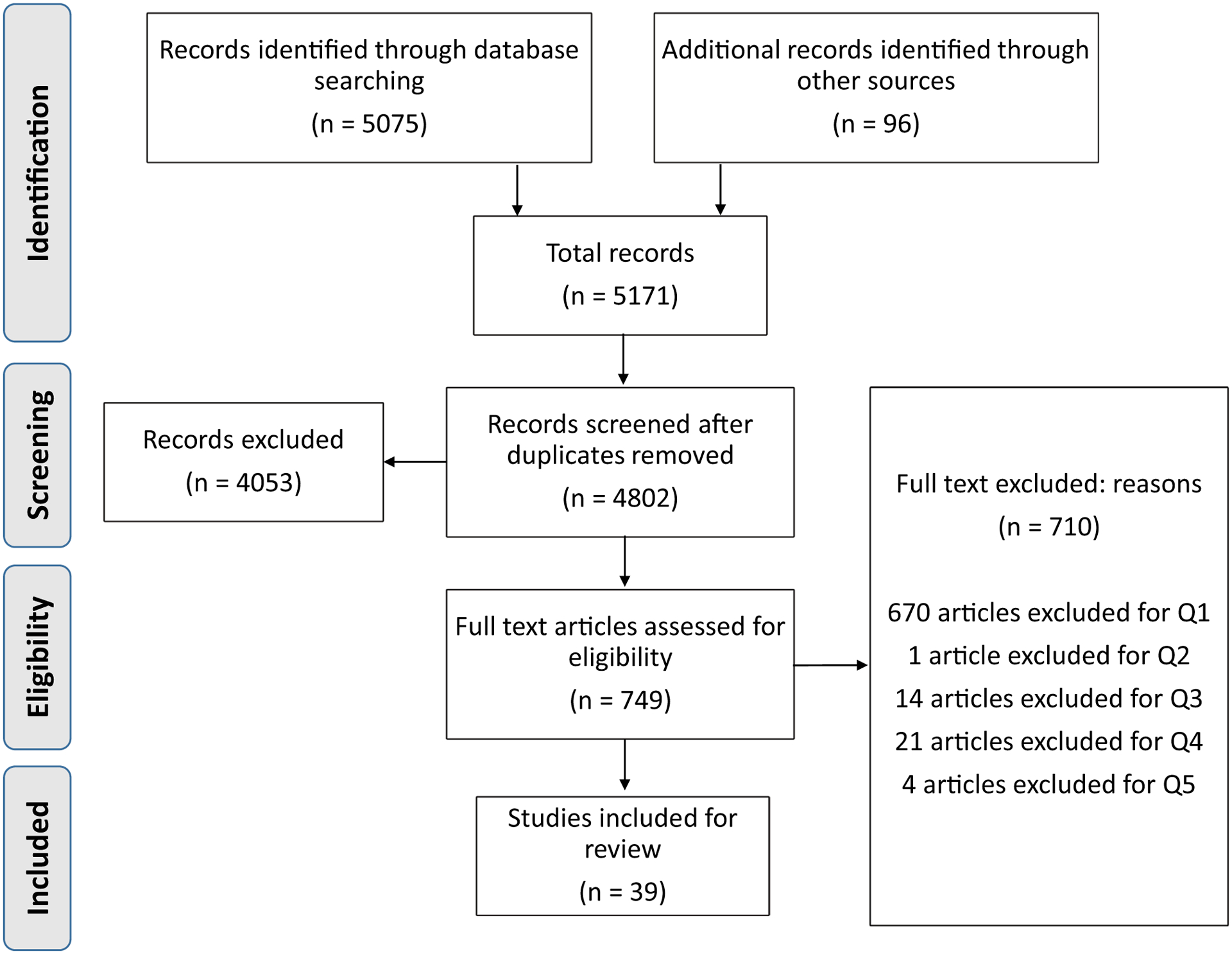

Please contact the first author for access to the systematic review protocol. The literature search was first conducted using the electronic databases PubMed and PsycINFO (see Table 1 for search terms). No limitations were placed on publication date given the goal of characterizing the entire literature examining CPE in MH prevention programs; the last date searched was April 6, 2020. In addition, we contacted seven content experts in the field of caregiver engagement and/or prevention science to elicit additional articles to review. Four responded and sent articles that were included in the article selection process. The first author, with expertise in caregiver engagement, also submitted articles to be reviewed as part of the article selection process. A small number of articles were identified through the examination of the reference lists of articles that were screened for inclusion in this review. Duplicate articles identified through the search process were removed prior to article selection procedures. See Fig. 1 for the number of articles screened from each source.

Table 1.

Search terms and inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Search terms |

|---|

| [parent* or mother* or father* or famil* or caregiver*] AND [engage* or involve* or participat* or “homework compliance” or “homework completion” or adhere*] AND [prevent* or intervention* or service* or program*] AND [mental health” or “behavioral health” or “parent training”] NOT [schizophrenia or pregnancy or cancer or diabetes or oncology or dementia or HIV or AIDS or obesity or inpatient or “residential treatment” or “older adult*” or “adult caregiver*” or “chronic pain” or “multiple sclerosis” or “weight management” or bulimia or anorexia or “chronic illness” or “developmental delay*” or “developmental disabilit*” or “emotional eating” or “autism” or “drug abuse*” or “alcohol abuse*” or “substance abuse*”] |

| Abstract screening eligibility criteria |

| Include |

| About a program that has been implemented. |

| Exclude |

| About a drug or vitamin treatment only. |

| About adults 18 and over, not in their role as caregivers. |

| About pregnant women. |

| If the target population is limited to families with a child with a specified physical health problems like obesity, diabetes, cancer, or traumatic brain injury. |

| Focuses only on autism, speech/language treatment, physical therapy, or occupational therapy. |

| Exclude if the article focuses on children under 18 that have a diagnosed mental health disorder. |

| Exclude if the article is a review article, case study, or study protocol that describes a study that has not been completed yet. |

| Exclude if the article is clearly not about child mental health. |

| Article screening inclusion criteria |

| The article examined caregiver participation engagement in a program, defined as specific caregiver participation behaviors in clinical interactions, homework completion or adherence to intervention strategies at home, and/or any type of ratings of how much the caregiver participated in the service beyond attendance. |

| The article examined single or multiple program(s). |

| The program examined in the article is focused at least in part on addressing child (18 and younger) mental health disorders. |

| The program was focused at least in part on preventing child mental health disorders (versus treatment for an already diagnosed disorder). |

| The article included original quantitative data analyses that asked an inferential research question that identified factors associated with CPE, examined associations between CPE and outcomes, and/or explored the effects of strategies used to enhance CPE. |

Fig. 1.

PRISMA figure. Q1 caregiver participation measured, Q2 study examined a single or group of program(s), Q3 program focused at least in part on addressing child mental health disorders, Q4 pro gram was preventive in nature for child mental health disorders (versus treatment for an already diagnosed disorder), Q5 original quantitative data analyses that ask an inferential research question

Article Selection Procedures

We applied a two-step process to screen and identify included articles, applying distinct but related criteria (see Table 1). The first step in the article selection process was abstract screening. One inclusion criterion and eight exclusion criteria were developed by the authors. The first author trained research assistants to screen abstracts and 24% (n = 1125) of abstracts were double-screened to assess interrater reliability (92.8% agreement). The second step was full-text article screening. Each article was independently screened by two doctoral-level authors, and discrepancies were brought to the full group of article screeners to reach consensus. See Fig. 1 for additional information about the article screening process and reasons for exclusion.

Data Extraction

The initial coding scheme was developed a priori based on the research questions, with additional codes being generated deductively. Coder training consisted of coding one article for practice, refining the coding manual based on group discussion of coding decisions for that article, assigning home-based practice with a second article, and reviewing coding decisions for the second article as a group. Similar to the article screening process, each included article was independently coded and subsequently consensus coded by two doctoral-level authors and discrepancies were brought to the full group of coders to resolve. Data were extracted using coding manuals, which were then entered into SPSS. Double data entry and verification were completed for all data collected. A copy of the coding manuals is available from the first author. Separate coding manuals were created for the article and the CPE indicator(s); in the event that an article included more than one indicator of CPE, separate coding manuals for each indicator were completed.

The extracted data for the article-level coding included 39 data points focused on (1) publication date, (2) program context, (3) sample characteristics, (4) operational definition of CPE, and (5) empirical findings that include CPE as a variable. For our coding of empirical findings, and specifically results pertaining to the impact of CPE on program outcomes, we applied the Hoagwood et al. (2012) categorization of child and family MH treatment outcome domains, including child symptoms (emotions or behaviors often leading to a formal psychiatric diagnosis), caregiver symptoms (similar to previous but assigned to the caregiver), child functioning or impairments (capacity to adapt to home, school, and community demands), consumer-oriented perspectives (child or caregiver perceptions about, for example, satisfaction with care, family strain, beliefs about treatment), interpersonal/environmental contexts (e.g., parenting, parent/child relationship, family functioning, peer-related outcomes), and services/systems (e.g., level, type, duration, or change in use of services). The extracted data for the indicator-level coding included 13 data points focused on (1) the content of the CPE indicator, (2) psychometrics of the CPE indicator, (3) the type of indicator (e.g., survey, observational coding, post-session rating), (4) who reported on the indicator, and (5) how frequently the indicator was assessed.

Reduction of Bias

To reduce the risk of reporting bias, multiple articles from the same dataset were grouped together as a project, with the project subsequently being used as the unit of analysis. For example, when two articles from the same dataset examined the association of CPE with other factors (e.g., impact of maternal depression on CPE), the finding was only counted once to prevent inflating our understanding of the association between constructs. To reduce the risk of bias in interpretation of the results, specifically for the 22 articles examining outcomes associated with CPE and/or strategies to enhance CPE, each article was independently coded by two authors to first assess the purpose of the program (i.e., was CPE mentioned in the article as a goal of the actual program or not). For those that had CPE as an explicit goal of the program (45.5%; n = 10), measurement of CPE was coded to assess whether the measure(s) had a low risk of bias (e.g., caregiver ratings or objective measures like homework completion) or high risk of bias (e.g., provider or researcher ratings). Only five articles from three projects were determined to be at high risk of bias, indicating low levels of potential bias across articles that might impact interpretation of findings.

Analysis Plan

Analyses consisted of running descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26 (IBM, 2019) to characterize the projects and articles included in the current review. Analyses involved an overview of included projects and associated articles, and specific representation across projects and/or articles regarding the study context and service delivery, child and family characteristics, provider characteristics, terms used to represent CPE, measurement of CPE, determinants and outcomes associated with CPE, and strategies used to improve CPE. Descriptives regarding the scientific rigor of each project were also analyzed (e.g., examination of reliability and validity of CPE indicators, examination of whether power analyses were conducted).

Results

Overview of Articles

Overall, 39 articles representing 27 unique projects were included in the current review. See Online Resource 2: Article Descriptions for more details about the included articles and projects (in terms of included article references, those cited in this article can be found marked with an asterisk in the “References” section; those not cited in this article can be found in Online Resource 3: Articles in Review Not Cited in Manuscript). The publication dates ranged from 1995 to 2020, with 59% of articles published after 2010. Project focus (Institute of Medicine, 1994) was as follows: 6 universal (22%), 8 selective (30%), 10 indicated (37%), 2 targeted (both selective and indicated; 7%), and 1 not able to determine (4%). See Table 2 for details regarding the child, caregiver/family, and provider characteristics in the included projects. Most projects included both female and male caregivers, and about half of participants were Caucasian. Few projects included details regarding child or provider characteristics such as child gender or race/ethnicity or provider education or discipline.

Table 2.

Child, caregiver/family, and provider characteristics in included projects

| Variable | Projects | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Child age | Early childhood (0–5 years) | 20 | 74 |

| Elementary school age (5–12 years) | 24 | 89 | |

| Adolescence (13–17 years) | 7 | 26 | |

| Child gender | Female and male | 3 | 11 |

| Male only | 2 | 7 | |

| Not specified | 22 | 81 | |

| Child race/ethnicity | Caucasian | 3 | 11 |

| African American | 2 | 7 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | 7 | |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 2 | 7 | |

| Native American | 1 | 4 | |

| Other | 2 | 7 | |

| Not specified | 24 | 89 | |

| Caregiver gender | Female and male | 21 | 78 |

| Female only | 1 | 4 | |

| Not specified | 5 | 19 | |

| Caregiver race/ethnicity | Caucasian or White | 16 | 59 |

| Average % Caucasian or White (SD) | -- | 46 | |

| African American | 11 | 41 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 | 22 | |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 13 | 48 | |

| Native American | 3 | 11 | |

| Multiethnic/multiracial | 4 | 15 | |

| Other | 11 | 41 | |

| Not specified | 8 | 30 | |

| Provider education level | High school | 2 | 7 |

| Bachelor’s | 3 | 11 | |

| Current graduate student/trainee | 5 | 19 | |

| Master’s | 2 | 7 | |

| PhD/MD | 1 | 4 | |

| Graduate degree not specified | 9 | 33 | |

| Not specified | 18 | 67 | |

| Provider discipline | Psychology | 5 | 19 |

| Social work | 3 | 11 | |

| Counseling | 1 | 4 | |

| Education | 3 | 11 | |

| Paraprofessionals | 1 | 4 | |

| Other discipline | 5 | 19 | |

| Not specified | 18 | 67 | |

n = 27

Aim 1: Terms and Measurement of CPE

Numerous terms were used to describe CPE across projects, with some projects using multiple terms. Seven projects utilized the term “engagement” or some variant (e.g., parent engagement, program engagement), five used the term “participation” or a variant (e.g., quality of participation), and five used the term “homework” or a variation (e.g., homework completion, home practice success, skill generalization). Fifteen projects included an operational definition of CPE. Many projects examined how well the caregiver participated in interactions with providers, which could include behaviors as well as expressed attitudes such as openness and cooperation. Other projects focused on behaviors outside of the provider’s presence, such as completion of homework or number of clicks for online programs. Six projects used definitions informed by prior literature (Bamberger et al., 2014, Berkel et al., 2018; Giannotta et al., 2019; Nix et al., 2009; Nye et al., 1999; Schoenfelder et al., 2013). A total of 36 unique measures of CPE were used across the 27 projects. A total of five projects included two measures and two projects included three measures. See Table 3 for a full description of the types and targets of measurement tools used. The psychometric performance of most of these measures was not previously evaluated, with only five projects (19%) using a CPE measure informed by and/or associated with prior published work.

Table 3.

Measurement of caregiver participation engagement

| Projects | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Specific construct measured | ||

| Global | 10 | 37 |

| Specific behaviors: home practice | 19 | 70.3 |

| Specific behaviors: in session | 12 | 44.4 |

| Measurement method | ||

| Survey | 10 | 37 |

| Caregiver-report survey | 4 | 14.8 |

| Provider-report survey | 6 | 22.2 |

| Objective indicator | 11 | 40.7 |

| Post-session observational rating | 10 | 37 |

| Measurement frequency | ||

| Each session | 17 | 63 |

| At regular intervals | 1 | 3.7 |

| One or more specific sessions | 2 | 7.4 |

| Randomly selected points in time | 1 | 3.7 |

| At end of program | 3 | 11.1 |

| Other | 2 | 7.4 |

| Measurement psychometrics | ||

| Internal consistency | 10 | 37 |

| Interrater reliability | 4 | 14.8 |

| Validity | 1 | 3.7 |

| Not reported | 16 | 59.3 |

n = 27

Aim 2: Factors Associated with CPE

A total of 22 projects (81.5%) examined determinants of CPE. Table 4 includes information about specific findings, with factors organized into categories based on an ecological multi-level services research framework (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015; Rodriguez et al., 2014).

Table 4.

Summary of factors associated with CPE

| P# | Article authors and years | Child factors | Caregiver/family factors | Provider factors | Service factors | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal programs | ||||||

| 6 | Bamberger et al. (2014) |

Chronic family tension* (−) Genderns Family tension during sessionsns |

Intervention condition (Strengthening Families Program or SFP v. Mindfulness Based SFP)a | Lb | ||

| 6 | Coatsworth et al. (2017) | Internalizing symptomsns Externalizing symptomsns |

College degree obtained* (+) Partnered marital status* (+) Parenting avoidance* (−) Caregiver-child negative affective relationship quality* (+) Parenting competencens Parenting hasslesns Positive parenting supportns Positive parenting involvementns Caregiver-child positive affective relationship qualityns Baseline depressive symptomsns Caregiver first session engagementns |

Intervention condition* (+; MSFP greater than SFP) Attendance* (+) |

Lb | |

| 12 | Dumas et al. (2007) | Genderns Agens Baseline externalizing symptomsns |

Partnered marital status* (+) Lower maternal education level* (+) Agens Identified race/ethnicityns Family incomens Baseline stressful life eventsns Time/scheduling demandsns Caregiver perceived relevance or trust in parenting programsns |

Attendance* (+) Geographic location of study site* (+; Indianapolis greater than Harrisburg) Intervention demandsns |

Lb | |

| 12 | Dumas et al. (2008) | Agens Identified race/ethnicityns Marital statusns Lower maternal education level (years)ns Family incomens |

Provider SES match with caregiver* (+) Overall provider match with caregiver* (+) Provider ethnic match with caregiverns Provider attitude match with caregiverns Provider values match with caregiverns |

Geographic location* (+; Indianapolis greater than Harrisburg) | Lb | |

| 12 | Dumas et al. (2010) | Agens Identified race/ethnicityns Marital statusns Family incomens |

Intervention condition* (+; monetary incentive greater than no monetary incentive) | Lb | ||

| 12 | Begle and Dumas (2011) | Attendance* (+) | Lb | |||

| 12 | Hernandez Rodriguez et al. (2020) |

Partnered marital status* (+) Agens Identified race/ethnicity |

Attendance* (direction not reported) | Lb | ||

| 13 | Lucia and Dumas (2013) | Attendancens | L | |||

| 14 | Dumas et al. (2011) | Attendancens | L | |||

| Selective programs | ||||||

| 2 | Baydar et al. (2003) |

Harsh, inconsistent, and supportive parenting-caregiver and observer reports* (+) Parenting-observational* (+) Depressive symptoms* (−) History of substance abuse* (+) Trait anger/aggressionns Experience of harsh or abusive parentinga |

Lb | |||

| 2 | Reid et al. (2004) |

Baseline externalizing symptoms* (+) Baseline prosocial behaviorns |

Lb | |||

| 4 | Garvey et al. (2006) | Attendance* (+) | Lb | |||

| 5 | Breitenstein et al. (2010) |

Adherence to protocol* (+) Competencens |

Lb | |||

| 5 | Gross et al. (2011) |

Attendance* (+) Child care discountns |

L | |||

| 9 | Lopez et al. (2018) | Attendance* (+) | L | |||

| 15 | Schoenfelder et al. (2013) |

Baseline externalizing symptoms* (−) Baseline internalizing symptoms (a) |

Baseline depression* (−) Baseline positive parenting* (+) Baseline griefns |

Attendance* (+) Intervention group* (significant percent of variance in CPE associated with which specific program group the caregiver was assigned to within the intervention condition) |

Lb | |

| 16 | Martinez and Eddy (2005) | Genderns Agens Birthplace (U.S. vs. other)ns |

L | |||

| 17 | Doty et al. (2016) |

Female gender* (+) College degree education* (+) No history of deployment* (+) Number of months deployed* (+) |

Lb | |||

| 17 | Pinna et al. (2017) |

Age* (−) European American identified race/ethnicity* (+) Genderns Educationns Number of childrenns Family incomens Deployment statusns |

Shared military-connected backgroundns |

Home practice satisfaction* (+) Participant satisfaction across intervention sessionsns Positive group experiencens |

L | |

| 17 | Zhang et al. (2017) |

Female gender* (+) Baseline dispositional mindfulnessns |

In-person attendance* (+) | Lb | ||

| 23 | Nicholson et al. (2002) | Time/intervention phase* (+) | Lb | |||

| 24 | Berkel et al. (2018) |

Baseline relationship quality-caregiver report* (+) Baseline relationship quality-child reportns Baseline consistent discipline-caregiver report* (+) Baseline consistent discipline-child report* (+) Baseline conflict-caregiver reportns Baseline conflict-child reportns |

Attendance* (+) | Lb | ||

| 25 | Day and Sanders (2018) | Intervention condition* (+; practitioner support enhanced program greater than self-directed program) | ||||

| Indicated programs | ||||||

| 7 | Ogg et al. (2014) | Agens Current diagnostic statusns Baseline externalizing symptomsns |

Agens Educationns |

Intervention versionns (English or Spanish) | Lb | |

| 8 | Davidson et al. (2017) | Baseline psychological distressa | L | |||

| 11 | Cunningham et al. (1995) | Intervention conditionns (Community/Group parent training v. Clinic/Individual parent training) | L | |||

| 18 | Orrell-Valente et al. (1999) | Baseline externalizing symptomsns |

European American identified race/ethnicity* (+) Agens SESns Male in householdns Baseline stressful life eventsns Baseline parenting efficacyns Baseline satisfaction with parenthoodns |

Therapeutic engagement with caregiverns Provider race match with caregiverns Provider SES match with caregiverns Relevant life events shared with caregiverns |

Lb | |

| 18 | Nix et al. (2009) | Identified race/ethnicityns Baseline externalizing symptomsns |

Higher education level* (+) Agens Single parentns Higher occupational prestige* (+) Baseline stressful life eventsns Baseline depressive symptomsns Baseline social supportns Baseline home environmentns Neighborhood qualityns |

Intervention group* (significant percent of variance in CPE associated with which specific program group the caregiver was assigned to within the intervention condition) Other group members’ quality of participation* (+) |

Lbc | |

| 21 | Eisenhower et al. (2016) | Baseline sociodemographic riskd ns | L | |||

| 22 | Morgan et al. (2018) |

Female gender* (+) Agens Baseline internalizing symptomsns Baseline impairmentns Baseline child inhibitionns |

Access to printer* (+) Agens Marital statusns Educationns Lives in major cityns Only childns English as primary household languagens Family financial hardshipns Weekly internet usens Baseline family strainns Baseline psychological distressns Baseline overinvolved/overprotective parentingns |

Lb | ||

| 26 | Ristkari et al. (2019) | Implementation type* (community trial had higher CPE than research trial) | ||||

| Not specified programs | ||||||

| 27 | Giannotta et al. (2019) |

Understanding caregivers’ problems-caregiver report* (+) Agens Genderns Educationns Group management skills-caregiver reportns Supportive of caregivers-caregiver reportns |

Intervention condition* (Comet intervention program higher CPE than Cope program, Incredible Years program, and Connect program) | L | ||

Results may be different across articles from the same project because the samples and/or analyses may have been different for each article. The value in parentheses indicates the direction of significant effects, with (+) indicating a positive association and (−) indicating a negative association. Any indication of the baseline time point is included in this table when it is clearly articulated in the article

P# project number, L longitudinal design

Significant association with CPE

ns No significant association with CPE

No inferential statistical test reported

Multivariate analyses

Power analyses conducted

High school or less, low income, teen parenthood, unemployment, racial minority status, and single-caregiver status

Child Factors Associated with CPE

A total of nine articles from eight projects examined child-level factors, including child demographic factors and child MH symptoms.

Child Demographics

In general, no significant associations were found between CPE and child gender, race, or birth location (U.S. versus other). Only one of the four projects examining CPE and child gender observed a significant association, with caregivers of female children completing homework more frequently than caregivers of male children.

Child Baseline MH Symptoms

The most commonly examined child factor was child baseline MH symptoms, with seven projects exploring how baseline symptoms may contribute to CPE. Most found no significant association. Two projects identified significant links between baseline externalizing symptoms and CPE, with mixed results.

Caregiver/Family Factors Associated with CPE

Nineteen articles across 12 projects examined how caregiver/family-level factors may predict CPE. These factors included caregiver/family demographics, caregiver baseline MH symptoms, parenting behaviors, and family environment.

Caregiver/Family Demographics

Significant associations between caregiver education level, marital status, race/ethnicity, and CPE were found in at least half of the projects that examined these factors. Of six projects, three observed a significant, positive association between caregiver education and CPE. Four projects examined marital/partner status and CPE, with two noting a significant association between having a partner and higher levels of CPE. Caregiver race/ethnicity was a significant predictor of CPE in two out of the three projects that examined it, with caregivers from European American backgrounds exhibiting more CPE. The majority of projects found no significant relationship between CPE and income/socioeconomic status (examined in five projects), caregiver age (five projects), and primary household language (one project).

Caregiver Baseline MH Symptoms

Of the six projects examining caregiver MH, three observed significant associations; for example, caregiver depressive symptoms were related to less CPE and caregiver history of substance use was related to more CPE.

Parenting Behaviors

The majority of projects examining parenting behaviors and CPE (four out of five) found that greater levels of negative and positive parenting behaviors were associated with lower and higher CPE, respectively.

Family Environment

Five projects examined how different types of family environment factors, such as family tension and strain, family risk, time and scheduling demands, marital discord, number of children in the home, and military deployment status, influenced CPE. Only two projects found a significant association, such that greater family tension was associated with lower CPE, and caregivers with a history of deployment showed lower CPE than caregivers who had not been deployed. No significant associations between CPE and stressful life events (e.g., death in the family) were found.

Provider Factors Associated with CPE

Four projects examined provider-level factors, including demographics, provider-caregiver match, fidelity, and engagement skills.

Provider Demographics

One project examined the association between provider demographics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity) and found no significant association with CPE.

Provider-Caregiver Match

Of the three projects examined the match between provider and caregiver on one or more of several variables (ethnicity, SES, attitudes, values, shared background/life events), one project observed a significant and positive association between CPE and the extent of caregiver-provider match for the variable(s) studied.

Provider Fidelity

One project explored the relationship with fidelity, noting a significant, positive association between provider adherence to protocol, but not competence, and CPE.

Provider Engagement Skills

Two projects examined links between provider therapeutic engagement skills and CPE, with only one finding a significant, positive association between better provider understanding of caregiver problems and higher CPE.

Service Factors Associated with CPE

Seventeen projects across 24 articles examined service-level factors, including caregiver attendance and program characteristics.

Attendance

The majority of projects examining attendance (seven out of ten) found that higher caregiver attendance was associated with greater CPE.

Program Characteristics

Fifteen projects examined program factors such as greater group member engagement, which intervention group a caregiver/family was a member of within the intervention condition, amount of time in the program, and number of phone consultations received. All of these factors were significantly linked to greater CPE. In contrast, the intervention condition the caregiver/family was assigned to and provision of incentives were not consistently significantly linked to CPE.

Aim 3: Associations Between CPE and Program Outcomes

CPE Predicting Program Outcomes

A total of 13 projects (33.3%) examined whether CPE was associated with improved outcomes, all employing a longitudinal design to do so (see Table 5). We applied Hoagwood et al. (2012) categorization of program outcomes to organize results. The most common outcome domains examined were child symptoms and interpersonal/environmental contexts. As child functioning, caregiver/family symptoms, consumer-oriented perspectives, and services/systems were only examined in one or two projects each, our summary will focus on the outcome domains more frequently examined.

Table 5.

Summary of associations between CPE and program outcomes based on Hoagwood et al. (2012) domains

| P# | Authors and years | CPE categories measured | Child symptoms | Caregiver/family symptoms | Child functioning/impairment | Consumer-oriented perspectives | Interpersonal/environmental contexts | Services/systems | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal programs | |||||||||

| 12 | Begle and Dumas (2011) | Global | ns | + | + | ns | L # | ||

| 12 | Jobe-Shields et al. (2015) | Global | ns | L # | |||||

| Selective programs | |||||||||

| 2 | Baydar et al. (2003) | Specific At home |

+ | L# | |||||

| 2 | Reid et al. (2004) | Specific At home |

+ | + | L # | ||||

| 4 | Garvey et al. (2006) | Specific | + | + | L # | ||||

| 15 | Schoenfelder et al. (2013) | Global At home |

ns | + | + | L # | |||

| 17 | Zhang et al. (2017) | At home | + | L # | |||||

| 4 | Berkel et al. (2018) | At home | + | L # | |||||

| Indicated programs | |||||||||

| 3 | Tucker et al. (1998) | At home | ns | + | L ^ | ||||

| 8 | Davidson et al. (2017) | At home | @ | L | |||||

| 10 | Hooven et al. (2013) | Global Specific |

+ | L # | |||||

| 18 | Nix et al. (2009) | Global | + | L # | |||||

| 20 | Nye et al. (1995) | Global Specific At home |

+ | L # | |||||

| 20 | Nye et al. (1999) | Global Specific At home |

+ | L # | |||||

| 22 | Morgan et al. (2018) | At home | + | L # ^ | |||||

| Not specified programs | |||||||||

| 27 | Giannotta et al. (2019) | At home | ns | + | + | # | |||

P# project number, + significant positive association with CPE found such that increased CPE was associated with more positive outcomes, ns no significant associations with CPE demonstrated, @ no inferential statistical test reported, L longitudinal design,

multivariate analyses,

power analyses conducted,

Global overall ratings of CPE beyond attendance, Specific specific CPE behaviors in clinical interactions, At home homework completion or adherence to program strategies at home

Child Symptoms

Nine projects explored the influence of CPE on child MH symptom outcomes, with five noting a significant change in symptoms. Overall, higher levels of CPE prospectively predicted greater improvements in child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and were associated with greater improvement in child coping and prosocial competence following the program.

Interpersonal/Environmental Contexts

Seven of the eight projects that examined interpersonal/environmental contexts found that higher CPE predicted more positive outcomes related to parenting behaviors such as caregiver-child relationship quality and parenting skills, as well as caregivers’ dispositional mindfulness.

CPE Mediating or Moderating Program Outcomes

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, CPE was examined as a moderator or mediator of program outcomes in three and two projects, respectively. Results suggested that CPE moderated the effect of key child (e.g., prior foster care placements; DeGarmo et al., 2009) and family (e.g., caregiver ethnicity, family resources; Nye et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2017) determinants on program outcomes. In terms of mediation, results suggested that CPE mediated the impact of caregiver-level predictors (e.g., positive parenting, caregiver depression, caregiver education, and occupation) on program outcomes (Nix et al., 2009; Schoenfelder et al., 2013).

Table 6.

Summary of CPE as a moderator of baseline determinants of program outcomes

| Article | P# | Determinant domain | Study quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Family | Provider | |||

| DeGarmo et al. (2009) | 1 | Genderns Agens Prior number of placements* (for high level of prior placements, CPE associated with better outcomes) |

Ethnicity* (for Hispanic caregivers, CPE associated with better outcomes) Agens Caregiver-child ethnic matchns Moodns Kinship caregiverns |

Provider ethnic match with caregiverns | L # |

| Nye et al. (1995) | 20 |

Family resources* (higher CPE suppressed negative association between family resources and program outcomes) Agens Psychopathologyns |

L # | ||

| Zhang et al. (2017) | 17 | Gender* (for mothers, CPE associated with better outcomes) | L # | ||

P# project number,

significant association with CPE,

ns no significant association with CPE, L longitudinal design,

multivariate analyses

Table 7.

Summary of CPE as a mediator of determinants of program outcomes

| Article | P# | Determinanta (all in family domain) | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nix et al. (2009) | 18 |

Education*

(+) Occupation* (+) |

L # ^ |

| Schoenfelder et al. (2013) | 15 |

Depression*

(−) Positive parenting* (+) |

L # |

All determinants were from the caregiver/family domain

P# project number,

significant association with CPE,

L longitudinal design,

multivariate analyses,

power analyses conducted

Aim 4: Strategies to Improve CPE

Four projects examined strategies to improve CPE in a child MH prevention program, all noting significant associations between CPE improvement strategies (e.g., motivational strategies, reinforcement strategies) and program outcomes (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Summary of associations between CPE improvement strategies and outcomes

| Article | Project # | CPE improvement strategya | CPE categories measured | Significant results? | Fidelity measured? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal | |||||

| Dumas et al. (2010) | 12 | Motivational, not otherwise specified (NOS) | Global Specific |

+ | No |

| Hernandez Rodriguez et al. (2020) | 12 | Provider reinforcement Motivational, NOS |

Global | + | Yes |

| Selective | |||||

| Day and Sanders (2018) | 25 | Appointment reminders Motivational, not otherwise specified |

At home | + | No |

| Doty et al. (2016) | 17 | Provider reinforcement | At home | + | No |

| Indicated | |||||

| Jones et al. (2014) | 19 | Provider reinforcement Appt reminders Modeling Crisis management Accessibility promotion |

At home | + | Yes |

Coded post hoc based on Lindsey et al. (2014)

+ significant results, Global broad measures of caregiver participation in the program, Specific specific caregiver in-session participation behaviors, At home behaviors pertaining to caregiver home practice

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of the literature on CPE in child MH prevention programs. The review aimed to (1) describe the terms used to operationalize CPE and measurement of CPE in prevention programs, (2) identify factors associated with CPE, (3) examine associations between CPE and program outcomes, and (4) explore the effects of strategies used to enhance CPE. From an initial pool of 5171 articles, we found a total of 39 published articles generated from 27 projects that examined CPE in child MH prevention programs.

Overall, results underlined heterogeneity in both the operationalization and the measurement of CPE. Numerous terms were used to describe CPE across projects. Projects used a variety of CPE measures; the psychometric performance of the majority of these tools was not previously evaluated or was unreported. The most frequent metric was caregiver home practice, followed by global measures of CPE and specific in-session participatory behaviors.

The most frequently examined determinants of CPE were those at the service (e.g., intra-group engagement, caregiver attendance) and caregiver/family levels (e.g., caregiver education level, marital status). However, given the variability in measurement and methodology across studies, we did not find clear determinants of CPE.

With regard to the impact of CPE on program outcomes, higher levels of CPE predicted greater improvements in child symptoms (e.g., internalizing and externalizing symptoms, coping, and prosocial behavior) and interpersonal/environmental contexts (e.g., caregiver-child relationship, parenting skills). This is consistent with the literature examining the impact of CPE on MH treatment (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015). Finally, in terms of strategies to improve CPE, the small collection of existing projects highlight the utility of motivational and behavioral strategies (e.g., reinforcement, appointment reminders) in promoting CPE. Again, these results mirror those in the treatment literature (Becker et al., 2015; Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015).

Our results indicate that researchers are increasingly interested in CPE and are seeking to conduct objective, concrete measurement of the construct. Of the 39 published articles, more than half were published in 2010 or later, suggesting that understanding and improving CPE in child MH prevention is of growing importance to the field. Although few projects used measures of CPE with strong psychometric properties, the majority of studies represented in the review aimed to use objective and survey-based measurement methods to quantify CPE. Studies’ operational definitions of CPE variables were typically specific and represented distinct caregiver behaviors both within and outside interactions with providers. Many projects examined how well the caregiver participated in interactions with providers, which could include behaviors as well as expressed attitudes such as openness and cooperation. Other projects focused on behaviors outside of the provider’s presence, such as completion of homework or number of clicks for online programs.

In addition, multiple projects elected to use more than one measure of CPE. For example, Nye et al. (1995) measured both mothers’ investment in the program through participatory behaviors (both within-session participation and between-session home practice) and overall completion of the program protocol. Even within the projects that only examined at-home CPE behaviors, researchers measured home practice engagement in multiple ways, capturing a combination of home practice frequency, fidelity to the assigned home practice, and efficacy or competence of home practice of program skills (e.g., Berkel et al., 2018; Schoenfelder et al., 2013).

The variety of ways in which researchers have operationalized and measured CPE speak to the complexity of the construct and the importance of its many components in child prevention services. Broadly, we found that numerous CPE behaviors were associated with significant changes in child symptoms and/or effective parenting. As studies continue to examine the role of CPE in the future, unified definitions and measurement will allow for specificity in associations and expansion of evidence-based strategies for increasing CPE.

Our review highlighted gaps in the literature regarding CPE. For one, existing studies do not provide enough information to inform community implementation of programs. Indeed, one of the great challenges facing prevention science is large-scale dissemination and scaling up of appropriate preventative and promotive interventions (Botvin, 2004; Gottfredson et al., 2015). However, few studies included in the review provided details regarding child or provider characteristics such as child gender, child race/ethnicity, or provider education. Such details are important for understanding the context of CPE and its correlates within a given study, which in turn inform community implementation efforts (Spoth et al., 2013). Further, there was limited examination of prevention programs within the context of community service settings such as educational settings, where the majority of children receive services. Given that schools are often at the frontline of providing MH prevention services to children and families (Bosworth, 2015; U.S. Public Health Service, 1999), the landscape of CPE within school settings and strategies to increase caregiver engagement needs further investigation. It is also important for future research to focus on identifying patterns of contextual factors associated with CPE, in particular for disadvantaged families who may need increased and/or tailored supports for CPE (Hackworth et al., 2018). It is also important to note a limitation of this review, namely, that incomplete retrieval of identified research may have occurred.

Despite the recent increase in attention to CPE in child prevention services, it is disappointing to see overall limited efforts to study and improve CPE. We believe that greater attention to CPE is warranted, both in identifying determinants of and strategies for increasing CPE. In addition, there are unanswered questions about the role of CPE in program outcomes and its link to maintenance or long-term preventative effects. Insights from the science of behavior change would suggest that at-home practice of program skills is more likely to translate into sustained changes in parenting and caregiver-child interactions, which in turn translate to longer-term maintenance effects. For example, Schoenfelder et al. (2013) found that CPE during the program mediated the durability of positive parenting post-intervention, but more research is needed to replicate these findings. Further, it is not unusual to find sleeper effects in prevention research wherein the effects of the prevention program do not appear or appear stronger later in time (e.g., Prado et al., 2007; Rapee, 2013). Long-term follow-up of CPE and its associations to outcomes is necessary to understand the potential role of CPE in prevention services. Similarly, CPE is routinely examined as a static variable measured at one point in time or averaged across the program period. One exception is Bamberger et al. (2014), who used growth curve modeling to examine CPE over the course of a 7-week intervention. Future examinations that focus on trajectories of CPE (similar to attendance trajectories) and variability in CPE over time may provide valuable information on how to increase CPE to levels that are both attainable (from the program side) and sustainable (from the caregiver side).

Among the 27 projects identified, four explicitly tested motivational and behavioral strategies for increasing CPE, including motivational interviewing, accessibility promotion, and appointment reminders. These strategies strongly mirror strategies to increase CPE found in the treatment literature (Haine-Schlagel & Walsh, 2015). In addition, researchers have identified several barriers to caregiver engagement more broadly and potential solutions for increasing caregiver engagement in prevention services through qualitative studies (Cunningham et al., 2019; Finan et al., 2020). Though their inquiry often focused on attendance, insights may be applicable to engagement and participatory behaviors broadly. For example, Finan et al. (2020) found that the term “prevention” was not easily understood or compelling to lay caregivers, thus restricting caregiver interest and eventual participation. Researchers also found that balance needed to be achieved between program duration that is not burdensome and yet simultaneously long enough such that caregivers perceive benefits to participation.

Increasingly, novel modalities are being utilized for prevention program delivery and dissemination, which may help maintain the balance of providing high quality and sufficient dosage of prevention services while simultaneously keeping caregiver burden low. Technology-assisted delivery with asynchronous scheduling is increasingly popular for its potential to allow caregivers to fit prevention services into their already-demanding lives (Clarke et al., 2015). In fact, numerous studies show that computerized delivery is effective, acceptable to caregivers, and feasible to implement (e.g., Dadds et al., 2019; Irvine et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2019). One of the main benefits of computerized delivery may be the potential to increase dosage of program content on demand (Dadds et al., 2019). Infusion of a computerized or social media component alone is not sufficient (Epstein et al., 2019). Rather, digital assistance that increases dosage and provides numerous exemplars to increase exposure and facilitates generalization of skills for caregivers appear particularly effective (Dadds et al., 2019; Irvine et al., 2015; Palmer et al., 2019). As more and more prevention programs move to online or computer-assisted platforms, explicit links between digital components and CPE need to be examined. These may inform the development of evidence-based digitally delivered strategies for increasing CPE.

Although the current review represents one of the first systematically characterizing CPE in MH prevention, several limitations should be noted. Almost all projects in the review were conducted within the context of a research study, limiting the generalizability of findings to broader populations and settings without academic research infrastructure or partnership. Further, this review is limited by focus and extraction on factors included in projects as they were reported or specified; it is possible that further characteristics, strategies, and associations exist but were not reported or specified in the original studies. This review was limited to studies published in English. Finally, it is also possible that further projects that qualitatively examined CPE in preventative MH programs exist but were not captured during data extraction in the current review.

In sum, the current systematic review highlights increasing focus on CPE within child MH prevention in recent years, and the important role that CPE plays in both the immediate and lasting effects of prevention programs. And yet, questions remain regarding strategies to increase CPE within prevention efforts. With the increasing adoption of digital/computerized programs and technology-assisted programs, the importance of CPE in child MH prevention is simultaneously magnified and tenuous.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Toni Araya, Naomi Cheuk, Katie Dennison, Jillian L. Garrison, and Susanne Tolciu for their contributions to this project.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIMH K23 MH115100 (K. Dickson, PI).

Footnotes

Competing Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants This work did not involve research with human participants and/or animals.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01303-x.

References

- Bamberger KT, Coatsworth JD, Fosco GM, & Ram N (2014). Change in participant engagement during a family-based preventive intervention: Ups and downs with time and tension. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 811–820. 10.1037/fam0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Baydar N, Reid MJ, & Webster-Stratton C (2003). The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for head start mothers. Child Development, 74(5), 1433–1453. 10.1111/1467-8624.00616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, & Chorpita BF (2015). The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 30–43. 10.1080/15374416.2013.814543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beelmann A, & Lösel F (2006). Child social skills training in developmental crime prevention: Effects on antisocial behavior and social competence. Psicothema, 18, 603–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Begle AM, & Dumas JE (2011). Child and parental outcomes following involvement in a preventive intervention: Efficacy of the PACE program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(2), 67–81. 10.1007/s10935-010-0232-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, & Sandler IN (2011). Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12, 23–33. 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, et al. (2018). “Home practice is the program”: Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the new beginnings program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 19(5), 663–673. 10.1007/s11121-016-0738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K (Ed.). (2015). Prevention science in school settings: Complex relationships and processes. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ (2004). Advancing prevention science and practice: Challenges, critical issues, and future directions. Prevention Science, 5, 69–72. 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013984.83251.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Breitenstein SM, Fogg L, Garvey C, Hill C, Resnick B, & Gross D (2010). Measuring implementation fidelity in a community-based parenting intervention. Nursing Research, 59(3), 158–165. 10.1097/nnr.0b013e3181dbb2e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell D (2019). Effectiveness of school-based interventions to prevent anxiety & depression in young people. European Journal of Public Health, 29, 1011–1020. 10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.02130932155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AM, Kuosmanen T, & Barry MM (2015). A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 90–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Hemady KT, & George MW (2017). Predictors of group leaders’ perceptions of parents’ initial and dynamic engagement in a family preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 19, 609–619. 10.1007/s11121-017-0781-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Bremner R, & Boyle M (1995). Large group community-based parenting programs for families of preschoolers at risk for disruptive behavior disorders: Utilization, cost effectiveness, and outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 1141–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PB, Foster SL, Kawahara DM, Robbins MS, Bryan S, Burleson G, Day C, Yu S, & Smith K (2019). Midtreatment Problems Implementing Evidence-based Interventions in Community Settings. Family Process, 58(2), 287–304. 10.1111/famp.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Stabile M, Manivong P, & Roos LL (2010). Child health and young adult outcomes. Journal of Human Resources, 45, 517–548. 10.3368/jhr.45.3.517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, & Mchugh TA (1992). Social support and treatment outcome in behavioral family therapy for child conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 252–259. 10.1037/0022-006x.60.2.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Thai C, Diaz AM, Broderick J, Moul C, Tully LA, Hawes DJ, Davies S, Burchfield K, & Cane L (2019). Therapist-assisted online treatment for child conduct problems in rural and urban families: Two randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(8), 706–719. 10.1037/ccp0000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, & Schneider BH (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18, 23–45. 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson TM, Bunnell BE, & Ruggiero KJ (2017). An automated text-messaging system to monitor emotional recovery after pediatric injury: Pilot feasibility study. Psychiatric Services, 68(8), 859–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Day JJ, & Sanders MR (2018). Do parents benefit from help when completing aself-guided parenting program online? A randomized controlled trial comparing Triple P online with and without telephone suCPEort. Behavior Therapy, 49(6), 1020–1038. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Chamberlain P, Leve LD, & Price J (2009). Foster parent intervention engagement moderating child behavior problems and placement disruption. Research on Social Work Practice, 19, 423–433. 10.1177/1049731508329407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Doty JL, Rudi JH, Pinna KLM, Hanson SK, & Gewirtz AH (2016). If you build it, will they come? Patterns of internet-based and face-to-face participation in a parenting program for military families. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6). 10.2196/jmir.4445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell KA, & Ogles BM (2010). The effects of parent participation on child psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 151–162. 10.1080/15374410903532585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Arriaga X, & Begle AM (2011). Child and parental outcomes of a group parenting intervention for Latino families: A pilot study of the CANNE program. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(1), 107–115. 10.1037/a0021972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Begle AM, French B, & Pearl A (2010). Effects of monetary incentives on engagement in the PACE parenting program. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 302–313. 10.1080/15374411003691792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Moreland AD, Gitter AH, Pearl AM, & Nordstrom AH (2008). Engaging parents in preventive parenting groups: Do ethnic, socioeconomic, and belief match between parents and group leaders matter? Health Education & Behavior, 35(5), 619–633. 10.1177/1090198106291374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, & Moreland AD (2007). From intent to enrollment, attendance, and participation in preventive parenting groups. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), 1–26. 10.1007/s10826-006-9042-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Eisenhower A, Taylor H, & Baker BL (2016). Starting strong: A school-based indicated prevention program during the transition to kindergarten. School Psychology Review, 45(2), 141–170. 10.17105/SPR45-2.141-170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Oesterle S, & Haggerty KP (2019). Effectiveness of Facebook groups to boost participation in a parenting intervention. Prevention Science, 20, 894–903. 10.1007/s11121-019-01018-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan SJ, Warren N, Priest N, Mak JS, & Yap MBH (2020). Parent non-engagement in preventive parenting programs for adolescent mental health: Stakeholder views. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 711–724. 10.1007/s10826-019-01627-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fryers T, & Brugha T (2013). Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 9, 1–50. 10.2174/1745017901309010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Connell A, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, & Wilson MN (2009). Moderators of outcome in a brief family-centered intervention for preventing early problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 543–553. 10.1037/a0015622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey C, Julion W, Fogg L, Kratovil A, & Gross D (2006). Measuring participation in a prevention trial with parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health, 29, 212–222. 10.1002/nur.20127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Giannotta F, Özdemir M, & Stattin H (2019). The implementation integrity of parenting programs: Which aspects are most important? Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(6), 917–933. 10.1007/s10566-019-09514-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Hamilton J, Freres DR, Patton K, & Gallop R (2006). Preventing depression among early adolescents in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled study of the Penn Resiliency Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 203–219. 10.1007/s10802-005-9014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FEM, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, & Zafft KM (2015). Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science, 16, 893–926. 10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gross D, Johnson T, Ridge A, Garvey C, Julion W, Treysman AB, et al. (2011). Cost-effectiveness of childcare discounts on caregiver participation engagement in preventive parent training in low-income communities. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(5–6), 283–298. 10.1007/s10935-011-0255-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth NJ, Matthews J, Westrupe EM, Nguyen C, Phan T, Scicluna A, Cann W, Bethelsen D, Bennetts S, & Nicholson JM (2018). What influences parental engagement in early intervention? Parent, program and community predictors of enrolment, retention and involvement. Prevention Science, 19, 880–893. 10.1007/s11121-018-0897-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, & Walsh NE (2015). A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18, 133–150. 10.1007/s10567-015-0182-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hernandez Rodriguez J, López C, & Moreland A (2020). Evaluating incentive strategies on parental engagement of the PACE parenting program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1957–1969. 10.1007/s10826-020-01730-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Jensen PS, Acri MC, Serene Olin S, Eric Lewandowski R, & Herman RJ (2012). Outcome domains in child mental health research since 1996: Have they changed and why does it matter? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1241–1260.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hooven C, Pike K, & Walsh E (2013). Parents of older at-risk youth: A retention challenge for preventive intervention. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(6), 423–438. 10.1007/s10935-013-0322-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, & Garber J (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 401–415. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine AB, Gelatt VA, Hammond M, & Seeley JR (2015). A randomized study of internet parent training accessed from community technology centers. Prevention Science, 16, 597–608. 10.1007/s11121-014-0521-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Langley AK, Stein BD, Wong M, Sharma P, Scott M, & Schonlau M (2009). Support for students exposed to trauma: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 1, 49–60. 10.1007/s12310-009-9007-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jobe-Shields L, Moreland AD, Hanson RF, & Dumas J (2015). Parent-child automaticity: Links to child coping and behavior and engagement in parent training. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 2060–2060. 10.1007/s10826-014-0007-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Cuellar J, Parent J, Honeycutt A, Khavjou O, Gonzalez M, Anton M, & Newey GA (2014). Technology-enhanced program for child disruptive behavior disorders: Development and pilot randomized control trial. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 88–101. 10.1080/15374416.2013.822308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey JA, Brandt ME, Becker KD, Lee BR, Barth RP, Daleiden EL, & Chorpita BF (2014). Identifying the common elements of treatment engagement interventions in children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(3), 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lopez CM, Davidson TM, & Moreland AD (2018). Reaching Latino families through pediatric primary care: Outcomes of the CANNE parent training program. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 40(1). 10.1080/07317107.2018.1428054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lucia S, & Dumas JE (2013). Entre-parents: Initial outcome evaluation of apreventive-parenting program for French-speaking parents. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(3), 135–146. 10.1007/s10935-013-0304-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Martinez CR Jr., & Eddy JM (2005). Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 841–851. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Mazza GL, Berkel C, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, & Winslow E (2018). Attendance trajectory classes among divorced and separated mothers and fathers in the New Beginnings Program. Prevention Science, 19, 620–629. 10.1007/s11121-017-0783-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Mccadam K, & Gonzales JJ (1996). Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner city children and their caretakers. Community Mental Health Journal, 32, 353–361. 10.1007/bf02249453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska A, & Sanders M (2006). A review of parental engagement in parenting interventions and strategies to promote it. Journal of Children’s Services, 1, 29–40. 10.1108/17466660200600004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Morgan AJ, Rapee RM, Salim A, & Bayer JK (2018). Predicting response to aninternet-delivered parenting program for anxiety in early childhood. Behavioral Therapy, 49(2), 237–248. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nicholson B, Anderson M, Fox R, & Brenner V (2002). One family at a time: A prevention program for at-risk parents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(3), 362–371. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00201.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nix RL, Bierman KL, & Mcmahon RJ (2009). How attendance and quality of participation affect treatment response to parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 429–438. 10.1037/a0015028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye CL, Zucker RA, & Fitzgerald HE (1995). Early intervention in the path to alcohol problems through conduct problems: Treatment involvement and child behavior change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 831–840. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nye CL, Zucker RA, & Fitzgerald HE (1999). Early family-based intervention in the path to alcohol problems: Rationale and relationship between treatment process characteristics and child and parenting outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 13, 10–21. 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ogg J, Shaffer-Hudkins E, Childres J, Feldman M, Agazzi H, & Armstrong K (2014). Attendance and implementation of strategies in a behavioral parent-training program: Comparisons between english and español programs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 555–564. 10.1002/imhj.21470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Orrell-Valente JK, Pinderhughes EE, Valente E Jr., & Laird RD (1999). If it’s offered, will they come? Influences on parents’ participation in a community-based conduct problems prevention program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 753–783. 10.1023/a:1022258525075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer ML, Keown LJ, Sanders MR, & Henderson M (2019). Enhancing outcomes of low-intensity parenting groups through sufficient exemplar training: A randomized control trial. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 50, 384–399. 10.1007/s10578-018-0847-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pinna KLM, Hanson S, Zhang N, & Gewirtz AH (2017). Fostering resilience innational guard and reserve families: A contextual adaptation of an evidence-based parenting program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(2), 185–193. 10.1037/ort0000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska PJ, Tully LA, Lenroot R, Kimonis E, Hawes D, Moul C, et al. (2017). Mothers, fathers, and parental systems: A conceptual model of parental engagement in programmes for child mental health—Connect, Attend, Participate, Enact (CAPE). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20, 146–161. 10.1007/s10567-016-0219-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Sullivan S, Tapia MI, Sabillon E, Lopez B, & Szapocznik J (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 914–926. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, & Miller GE (1994). Family-based treatment for childhood antisocial behavior: Experimental influences on dropout and engagement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 645–650. 10.1037/0022-006x.62.3.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]