Abstract

Coordinated regulation of gene activity by transcriptional and translational mechanisms poise stem cells for a timely cell-state transition during differentiation. Although important for all stemness-to-differentiation transitions, mechanistic understanding of the fine-tuning of gene transcription is lacking due to the compensatory effect of translational control. We used intermediate neural progenitor (INP) identity commitment to define the mechanisms that fine-tune stemness gene transcription in fly neural stem cells (neuroblasts). We demonstrate that the transcription factor FruitlessC (FruC) binds cis-regulatory elements of most genes uniquely transcribed in neuroblasts. Loss of fruC function alone has no effect on INP commitment but drives INP dedifferentiation when translational control is reduced. FruC negatively regulates gene expression by promoting low-level enrichment of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 in gene cis-regulatory regions. Identical to fruC loss-of-function, reducing Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 activity increases stemness gene activity. We propose low-level H3K27me3 enrichment fine-tunes gene transcription in stem cells, a mechanism likely conserved from flies to humans.

Research organism: D. melanogaster

eLife digest

From neurons to sperm, our bodies are formed of a range of cells tailored to perform a unique role. However, organisms also host small reservoirs of unspecialized ‘stem cells’ that retain the ability to become different kinds of cells. When these stem cells divide, one daughter cell remains a stem cell while the other undergoes a series of changes that allows it to mature into a specific cell type.

This ‘differentiation’ process involves quickly switching off the stem cell programme, the set of genes that give a cell the ability to keep dividing while maintaining an unspecialized state. Failure to do so can result in the differentiating cell reverting towards its initial state and multiplying uncontrollably, which can lead to tumours and other health problems. While scientists have a good understanding of how the stem cell programme is turned off during differentiation, controlling these genes is a balancing act that starts even before division: if the program is over-active in the ‘mother’ stem cell, for instance, the systems that switch it off in its daughter can become overwhelmed. The mechanisms presiding over these steps are less well-understood.

To address this knowledge gap, Rajan, Anhezini et al. set out to determine how stem cells present in the brains of fruit flies could control the level of activity of their own stem cell programme. RNA sequencing and other genetic analyses revealed that a protein unique to these cells, called Fruitless, was responsible for decreasing the activity of the programme.

Biochemical experiments then showed that Fruitless performed this role by attaching a small amount of chemical modifications (called methyl groups) to the proteins that ‘package’ the DNA near genes involved in the stem cell programme. High levels of methyl groups present near a gene will switch off this sequence completely; however, the amount of methyl groups that Fruitless helped to deposit is multiple folds lower. Consequently, Fruitless ‘fine-tunes’ the activity of the stem cell programme instead, dampening it just enough to stop it from overpowering the ‘off’ mechanism that would take place later in the daughter cell.

These results shed new light on how stem cells behave – and how our bodies stop them from proliferating uncontrollably. In the future, Rajan, Anhezini et al. hope that this work will help to understand and treat diseases caused by defective stem cell differentiation.

Introduction

Expression of genes that promote stemness or differentiation must be properly controlled in stem cells to allow their progeny to transition through various intermediate stages of cell fate specification in a timely fashion (Pollen et al., 2015; Bhaduri et al., 2021; Michki et al., 2021; Ruan et al., 2021; Dillon et al., 2022). Exceedingly high levels of stemness gene transcripts that promote an undifferentiated state in stem cells can overwhelm translational control that downregulates their activity in stem cell progeny and perturb timely onset of differentiation (San-Juán and Baonza, 2011; Xiao et al., 2012; Zacharioudaki et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2012; Larson et al., 2021; Ohtsuka and Kageyama, 2021). Conversely, excessive transcription of differentiation genes that instill biases toward terminal cellular functions in stem cells can overcome the mechanisms that uncouple these transcripts from the translational machinery and prematurely deplete the stem cell pool (Lennox et al., 2018; Baser et al., 2019; de Rooij et al., 2019; Marques et al., 2023). Thus, fine-tuning stemness and differentiation gene transcription in stem cells minimizes inappropriate gene activity that could result in developmental anomalies. Coordinated regulation of stemness and differentiation gene activity in stem cells by transcriptional and translational control poise stem cell progeny for a timely cell-state transition during differentiation (Ables et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2013; Kobayashi and Kageyama, 2014; Bigas and Porcheri, 2018; Rajan et al., 2021). Mechanistic investigation of the fine-tuning of stemness and differentiation gene transcription in vivo is challenging due to the compensatory effect of translational control, a lack of sensitized functional readouts, and a lack of insight into relevant transcription factors.

Neuroblast lineages of the fly larval brain provide an excellent in vivo paradigm for mechanistic investigation of gene regulation during developmental transitions because the cell-type hierarchy is well-characterized at functional and molecular levels (Janssens and Lee, 2014; Homem et al., 2015; Doe, 2017). A larval brain lobe contains approximately 100 neuroblasts, and each neuroblast asymmetrically divides every 60–90 min, regenerating itself and producing a sibling progeny that commits to generating differentiated cell types. Most of these neuroblasts are type I, which generate a ganglion mother cell (GMC) in every division. A GMC undergoes terminal division to produce two neurons. Eight neuroblasts are type II, which invariably generate an immature intermediate neural progenitor (immature INP) in every division (Bello et al., 2008; Boone and Doe, 2008; Bowman et al., 2008). An immature INP initiates INP commitment 60 min after asymmetric neuroblast division (Janssens et al., 2017). An immature INP initially lacks Asense (Ase) protein expression and upregulates Ase as it progresses through INP commitment. Once INP commitment is complete, an Ase+ immature INP transitions into an INP and asymmetrically divides 5–6 times to generate more than a dozen differentiated cells, including neurons and glia (Viktorin et al., 2011; Bayraktar and Doe, 2013). All type II neuroblast lineage cell types in larval brains can be unambiguously identified based on functional characteristics and protein marker expression. Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of sorted, fluorescently labeled INPs and their differentiating progeny from wild-type brain tissue has led to the discovery of many new genes that contribute to the generation of diverse differentiated cell types during neurogenesis (Michki et al., 2021). This wealth of information on the type II neuroblast lineage allows for mechanistic investigations of precise spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression during developmental transitions.

A multilayered gene regulation system ensures timely onset of INP commitment in immature INPs by coordinately terminating Notch signaling activity (Komori et al., 2018). Activated Notch signaling drives the expression of downstream-effector genes deadpan (dpn) and Enhancer of (splitz)mγ (E(spl)mγ), which promote stemness in type II neuroblasts by poising activation of the master regulator of INP commitment earmuff (erm) (San-Juán and Baonza, 2011; Xiao et al., 2012; Zacharioudaki et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2012; Zacharioudaki et al., 2016). During asymmetric neuroblast division, the basal protein Numb and Brain tumor (Brat) exclusively segregate into immature INPs, where they terminate Notch signaling activity and promote the timely onset of Erm expression (Bello et al., 2006; Betschinger et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006a; Lee et al., 2006b; Wang et al., 2006). Numb is a conserved Notch inhibitor and prevents continual Notch activation in immature INPs (Frise et al., 1996; Zhong et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2006a; Wang et al., 2006; Wirtz-Peitz et al., 2008). Asymmetric segregation of the RNA-binding protein Brat is facilitated by its adapter protein Miranda, which releases Brat from the cortex of immature INPs, allowing Brat to promote decay of Notch downstream-effector gene transcripts and thus initiate differentiation (Loedige et al., 2014; Laver et al., 2015; Loedige et al., 2015; Komori et al., 2018; Reichardt et al., 2018). Complete loss of numb or brat function leads to unrestrained activation of Notch signaling in immature INPs driving them to revert into type II neuroblasts leading to a severe supernumerary neuroblast phenotype. Similarly, increased levels of activated Notch or Notch transcriptional target gene expression in immature INPs can drastically enhance the moderate supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in brat- or numb-hypomorphic brains (Xiao et al., 2012; Janssens et al., 2014; Komori et al., 2014b; Komori et al., 2018; Larson et al., 2021). Collectively, these findings suggest that precise transcriptional control of Notch and Notch target gene expression levels during asymmetric neuroblast division is essential, safeguarding the generation of neurons that are required for neuronal circuit formation in adult brains.

We defined the fine-tuning of stemness gene transcription as a function that is mild enough to not effect INP commitment when lost alone but enough to enhance immature INP reversion to supernumerary neuroblasts induced by decreased post-transcriptional control of stemness gene expression. We established three key criteria to identify regulators which fine-tune stemness gene transcription in neuroblasts, (1) an established role in transcriptional regulation, for example a DNA-binding transcription factor, (2) clear expression in neuroblasts with no protein expression in immature INPs, and (3) acts as a negative regulator of its targets. From a type II neuroblast lineage-specific single-cell gene transcriptomic atlas, we found that fruitless (fru) mRNAs are detected in type I & II neuroblasts but not in their differentiating progeny. One specific Zn-finger containing isoform of Fru (FruC) is exclusively expressed in all neuroblasts. FruC binds cis-regulatory elements of most genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts, including Notch and Notch downstream-effector genes that promote stemness in neuroblasts. A modest increase in Notch or Notch downstream gene expression induced by loss of fruC function alone has no effect on INP commitment, but enhances immature INP reversion to type II neuroblasts in numb- and brat-hypomorphic brains. To establish how FruC might fine-tune gene transcription in neuroblasts, we examined the distribution of established histone modifications in the presence or absence of fruC. We surprisingly found FruC-dependent low-level enrichment of the repressive histone marker H3K27me3 in most FruC-bound peaks in genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts including Notch and its downstream-effector genes. The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) subunits are enriched in FruC-bound peaks in genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts, and reduced PRC2 function enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numb-hypomorphic brains, identical to fruC loss-of-function. We conclude that the FruC-PRC2-H3K27me3 molecular pathway fine-tunes stemness gene expression in neuroblasts by promoting low-level H3K27me3 enrichment in their cis-regulatory elements. The mechanism by which PRC2-H3K27me3 fine-tune stem cell gene expression will likely be relevant throughout metazoans.

Results

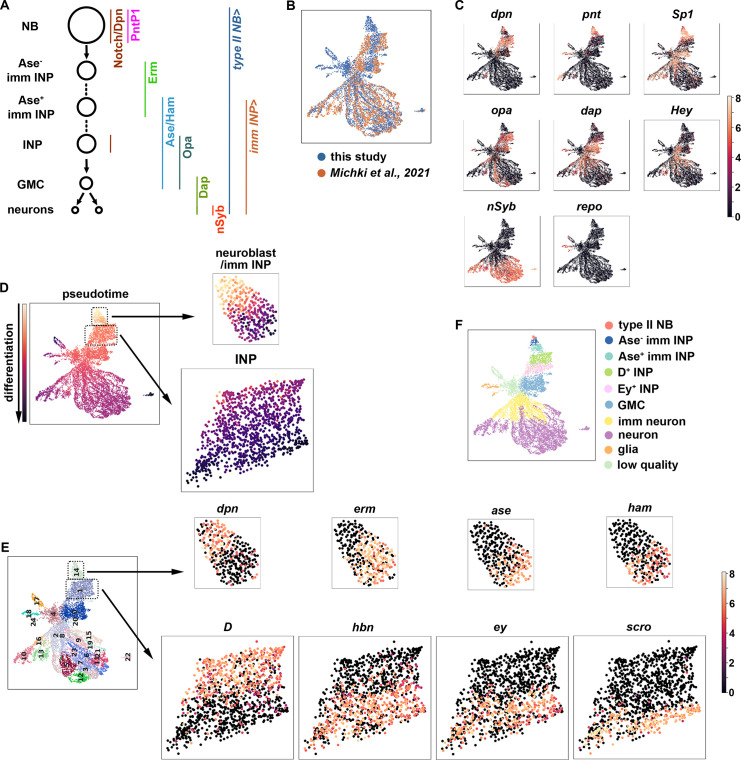

A gene expression atlas captures dynamic changes throughout type II neuroblast lineages

To identify regulators of gene transcription during asymmetric neuroblast division, we constructed a single-cell gene transcription atlas that encompasses all cell types in the type II neuroblast lineage in larval brains. We fluorescently labeled all cell types in the lineage in wild-type third-instar larval brains, sorted positively labeled cells by flow cytometry, and performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) using a 10x genomic platform (Figure 1A; Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). This new dataset displays high levels of correlation to our previously published scRNA-seq dataset which were limited to INPs and their progeny. The harmonization of these two datasets results in a gene transcription atlas of the type II neuroblast lineage consisting of over 11,000 cells (Figure 1B). Based on the expression of known cell identity genes, we were able to observe clusters consisting of type II neuroblasts (dpn+,pnt+), INPs (dpn+,opa+), GMCs (dap+,hey-), immature neurons (dap+,hey+), mature neurons (hey-,nSyb+), and glia (repo+) (Figure 1C). The UMAP positions of these clusters match well with the results of pseudo-time analyses from a starter cell that was positive for dpn, pnt, and RFP transcripts (Figure 1D). Leiden clustering of the data was able to capture these major cell types (Figure 1E), and quality control metrics showed most clusters captured on average 1.5 k genes and showed low mitochondrial gene expression (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). Thus, the harmonized scRNA-seq dataset captures molecularly and functionally defined stages of differentiation in the type II neuroblast lineage (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. A single-cell gene expression atlas of type II neuroblast lineages.

(A) Summary illustration of gene and Gal4 driver expression patterns in the type II neuroblast lineage. The type II NB Gal4 driver: Wor-Gal4,Ase-Gal80. imm INP driver: R9D11-Gal4. (B) Harmonization of the scRNA-seq dataset from the entire type II neuroblast (NB) lineage generated in this study (blue) and our previously published scRNA-seq dataset which were limited to INPs and their progeny (orange). The genotype of larval brains used for scRNA-seq in this study: UAS-dcr2; Wor-Gal4, Ase-Gal80; UAS-RFP::stinger. (C) UMAPs of known cell-type-specific marker genes. Color intensity indicated scaled (log1p) gene expression value. (D) Pseudotime analysis starting from cells enriched for dpn, pnt, and RFP transcripts. (E) Left: Leiden clustering of the scRNA-seq atlas. Right: Representative UMAPs of dynamically expressed transcription factors from clusters 14 (NBs and immature INPs) and 1 (INPs). Color intensity indicated scaled (log1p) gene expression value. (F) Annotated gene expression atlas of a wild-type type II neuroblast lineage.

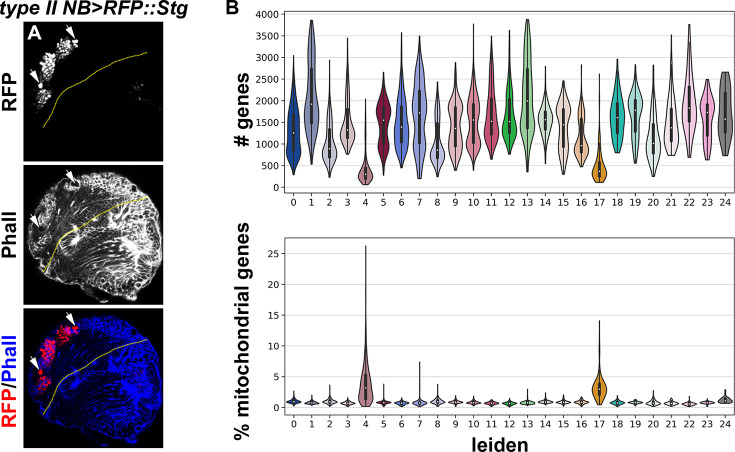

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Quality control data for the scRNA-seq atlas.

To determine whether the new scRNA-seq dataset encompasses neuroblast progeny undergoing dynamic changes in cell identity during differentiation, we examined transcripts that were transiently expressed in neuroblast progeny undergoing INP commitment or asymmetric INP division. We found that cluster 14 contains type II neuroblasts (dpn+,erm-,ase-,ham-), Ase- immature INPs (dpn-,erm+,ase-,ham-) and Ase+ immature INPs (dpn-,erm-,ase+,ham+) (Figure 1E), which are well-defined rapidly changing transcriptional states during INP commitment (Xiao et al., 2012; Janssens et al., 2014; Rives-Quinto et al., 2020). Furthermore, cluster 1 contains proliferating INPs that express known differential temporal transcription factors (Bayraktar and Doe, 2013; Tang et al., 2022), including young INPs (D+,hbn-,ey-,scro-) and old INPs (D-,hbn+,ey+,scro+) (Figure 1E). These data led us to conclude that the type II neuroblast lineage gene transcription atlas captures neuroblast progeny undergoing dynamic changes in cell identity during differentiation (Figure 1F).

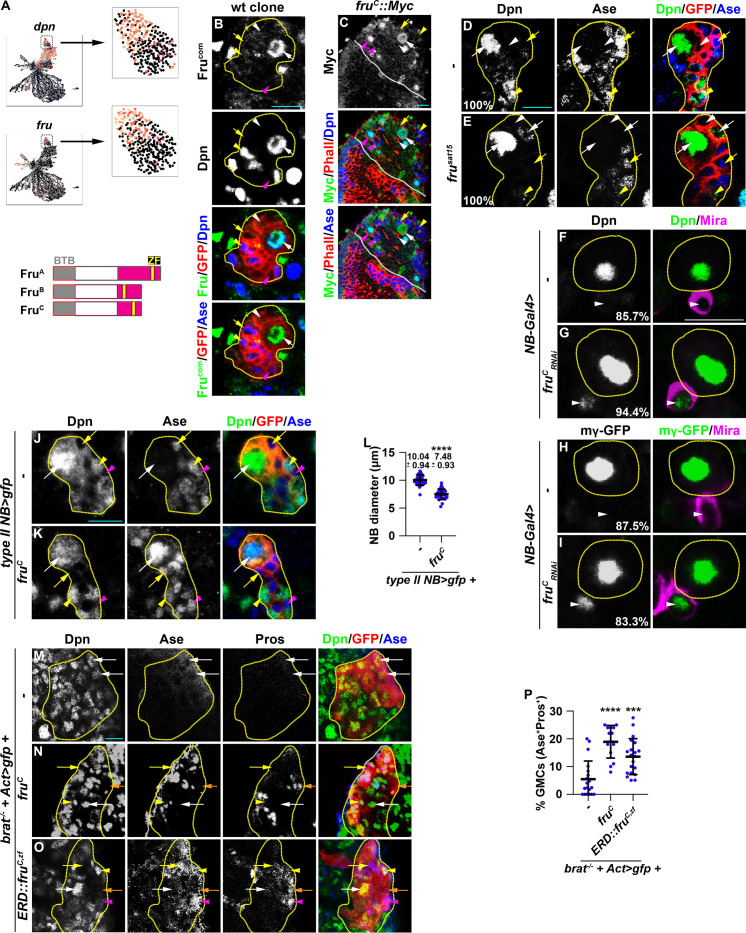

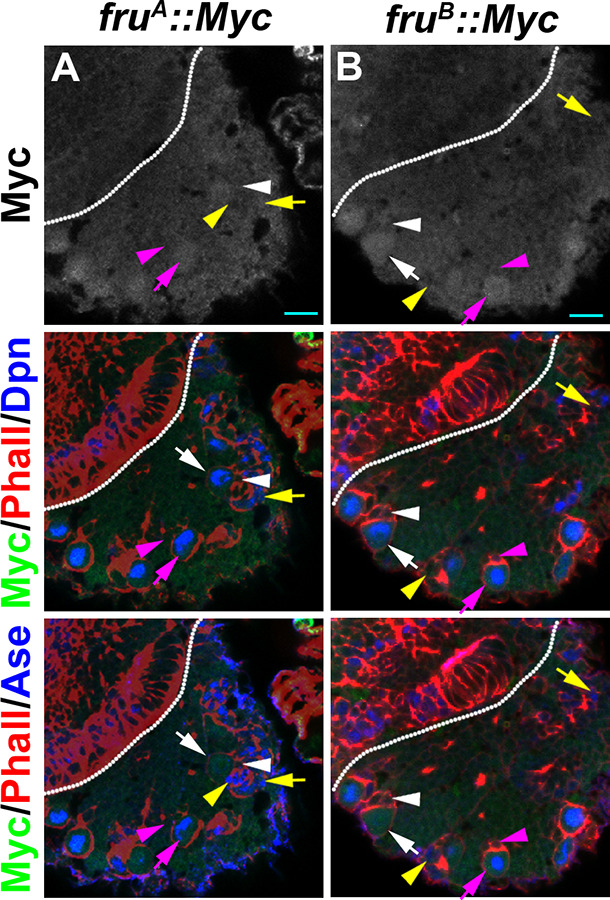

FruC negatively regulates stemness gene expression in neuroblasts

We hypothesized that regulators that fine-tune stemness gene expression in neuroblasts should (1) be transcription factors, (2) be exclusively expressed in type II neuroblasts, and (3) negatively regulate gene transcription. We searched for candidate genes that fulfill these criteria in the cluster 14 of the type II neuroblast lineage gene transcription atlas. dpn serves as a positive control because its transcripts are highly enriched in type II neuroblasts and rapidly degraded in Ase- immature INPs, allowing us to distinguish neuroblasts from immature INPs (Figure 2A–B). We found the expression of fru mirrors dpn expression, with transcript levels high in type II neuroblasts but lower in Ase- immature INPs (Figure 2A). fru is a pleiotropic gene with at least two major functions: one that controls male sexual behavior and another that is essential for viability in both sexes (Goodwin and Hobert, 2021). fru transcripts are alternatively spliced into multiple isoforms that encode putative transcription factors containing a common BTB (protein-protein interaction) N-terminal domain and one of four C-terminal zinc-finger DNA-binding domains (Dalton et al., 2013; Neville et al., 2014; von Philipsborn et al., 2014; Figure 2A). We used the Fru-common antibody that recognizes all isoforms to determine the spatial expression pattern of Fru protein in green fluorescent protein (GFP)-marked wild-type neuroblast clones. We detected Fru in neuroblasts but found that Fru is rapidly downregulated in their differentiating progeny in type I and II lineages (Figure 2B). To determine which Fru isoform is expressed in neuroblasts, we examined the expression of isoform-specific fru::Myc tagged allele where a Myc epitope is knocked into the C-terminus of the FruA, FruB, or FruC coding region (von Philipsborn et al., 2014). While FruA::Myc and FruB::Myc appear to be ubiquitously expressed at low levels, FruC::Myc is specifically expressed in both types of neuroblasts but not in their differentiating progeny, including immature INPs, INPs, and GMCs (Figure 2C, Figure 2—figure supplement 1A–B). These data indicate that FruC is the predominant Fru isoform expressed in neuroblasts.

Figure 2. Fruc functions through transcriptional repression to regulate stemness gene expression.

(A) Top: fru and dpn mRNAs are highly enriched in neuroblasts in cluster 14 of the scRNA-seq dataset, but only dpn mRNAs are detected in INPs in cluster 1. Bottom: Domains in Fru protein isoforms. ZF: zinc-finger DNA-binding domain. (B) Fru protein is detected in the neuroblast but not in INPs in a GFP-marked type II neuroblast lineage clone. The genotype used in this experiment is Elav-Gal4,UAS-mCD8::GFP,hs-flp; FRT82B,Tub-Gal80/FRT82B. (C) Endogenously expressed FruC tagged by a Myc epitope (fruC::Myc) is detected in type I and II neuroblasts but not in their differentiating progeny. (D–E) Immature INPs in GFP-marked wild-type type II neuroblast clones never show detectable Dpn expression (100%). 1–2 Ase- immature INP per fru-null (frusat15) type II neuroblast clone show detectable Dpn expression (100%). The genotype in this experiment is Elav-Gal4,UAS-mCD8::GFP,hs-flp; FRT82B,Tub-Gal80/FRT82B,fruSat15. (F–I) The newborn immature INP marked by cortical Miranda staining show undetectable Dpn and E(spl)mγ::GFP expression in the majority of wild-type clones (85.7%). Reducing fruC function leads to ectopic Dpn and E(spl)mγ::GFP expression in the newborn immature INP in most type II neuroblast lineages (94.4%). NB-Gal4: Wor-Gal4. (J–L) Type II neuroblasts overexpressing Fruc display characteristics of differentiation including a reduced cell diameter and aberrant Ase expression. Quantification of the cell diameter is shown in L. (type II NB>: Wor-Gal4, Ase-Gal80). (M–P) Overexpressing full-length Fruc or a constitutive transcriptional repressor form of FruC (Fruc,zf::ERD) is sufficient to partially restore differentiation in brat-null type II neuroblast clones (brat11/Df(2 L)Exel8040,hs-flp; Act5C-Gal4>FRT > FRT>UAS-GFP/UAS-fruC or ERD::fruC,zf). The percentage of GMCs per clone is shown in P. Yellow dashed line encircles a type II neuroblast lineage. White dotted line separates optic lobe from brain. white arrow: type II neuroblast; white arrowhead: Ase- immature INP; yellow arrow: Ase+ immature INP; yellow arrowhead: INP; magenta arrow: type I neuroblast; magenta arrowhead: GMC. Scale bars: 10 μm. p-values: ***<0.0005, and ****<0.00005.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. FruA and FruB are ubiquitously expressed in neuroblast lineages.

To define the function of Fru in neuroblasts, we assessed the identity of cells in the GFP-marked mosaic clones derived from single type II neuroblasts. The wild-type neuroblast clone always contains a single neuroblast that can be uniquely identified by cell size (10–12 μm in diameter) and marker expression (Dpn+Ase-) as well as 6–8 smaller, Dpn- immature INPs (Figure 2D). The neuroblast clone carrying deletion of the fru locus (fru-/-) contains a single identifiable neuroblast but frequently contains multiple Ase- immature INPs with detectable Dpn expression (Figure 2E). Over 80% of newborn immature INPs (marked by intense cortical Mira expression) generated by fruC-mutant type II neuroblasts ectopically express Dpn and E(spl)mγ while less than 15% of newborn immature INPs generated by wild-type neuroblasts expressed these genes (Figure 2F–I). These results support a model in which loss of fruC function increases the expression of Notch downstream-effector genes that promote stemness in neuroblasts. Consistently, type II neuroblasts overexpressing FruC prematurely initiate INP commitment, as indicated by a reduced cell diameter and precocious Ase expression (Figure 2J–L). Thus, loss of fruC function increases stemness gene expression whereas gain of fruC decreases stemness gene expression during asymmetric neuroblast division.

To determine whether FruC negatively regulates the transcription of stemness genes in type II neuroblasts, we overexpressed wild-type FruC in GFP-marked neuroblast lineage clones in brat-null brains. Ectopic translation of Notch downstream-effector gene transcripts that promote stemness in neuroblasts drives immature INP reversion to supernumerary type II neuroblasts at the expense of differentiating cell types in brat-null brains (Loedige et al., 2015; Komori et al., 2018; Reichardt et al., 2018). Control clones in brat-null brains contain mostly type II neuroblasts and few differentiating cells that include Ase+ immature INPs, INPs, and GMCs (Figure 2M and P). By contrast, overexpressing full-length FruC increases the number of INPs, GMCs, and differentiating neurons (Ase-Pros+) in brat-null neuroblast clones (Figure 2N and P). This result indicates that FruC overexpression is sufficient to partially restore differentiation in brat-null brains. To test if Fruc restores differentiation by promoting transcriptional repression, we generated fly lines carrying the UAS-fruC,zf::ERD transgene that encodes the zinc-finger DNA-binding motif of FruC fused in frame with the Engrail Repressor Domain. The ERD domain is well conserved in multiple classes of homeodomain proteins as well as many transcriptional repressors across the bilaterian divide and binds to the Groucho co-repressor protein to exert its repressor function (Smith and Jaynes, 1996; Jiménez et al., 1997; Bürglin and Affolter, 2016). Several previously published studies have used this strategy to demonstrate that neurogenetic transcription factors exert transcriptional repression function in neuroblasts (Xiao et al., 2012; Janssens et al., 2014; Bahrampour et al., 2017; Rives-Quinto et al., 2020). Similar to full-length FruC overexpression, overexpressing FruC,zf::ERD was also sufficient to partially restore differentiation in brat-null brains (Figure 2O–P). Thus, we conclude that FruC negatively regulates stemness gene expression in type II neuroblasts.

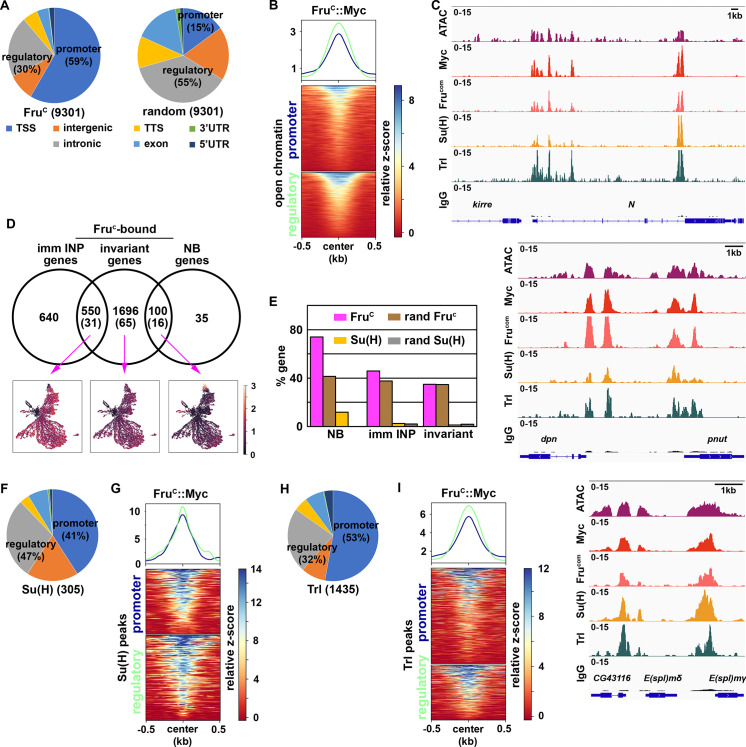

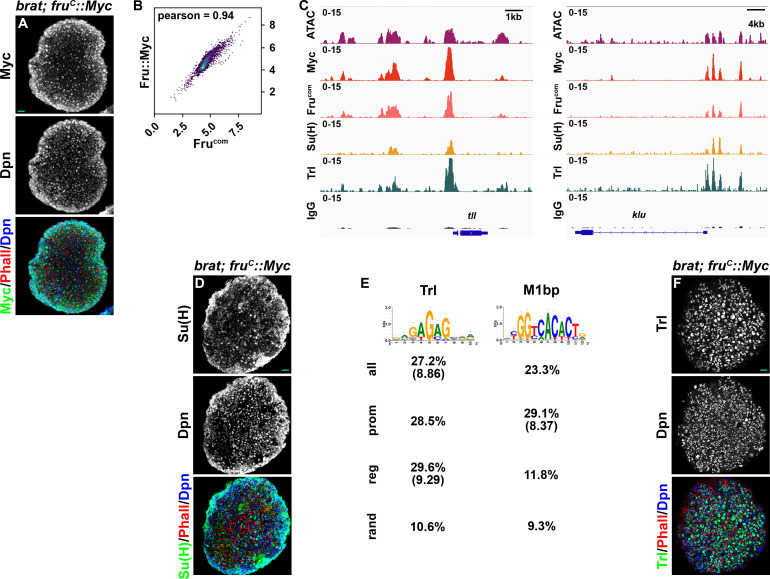

Fruc binds cis-regulatory elements of the majority of genes uniquely transcribed in neuroblasts

If FruC directly represses stemness gene expression, FruC should bind their cis-regulatory elements. To identify FruC-bound regions in neuroblasts, we applied a protocol of Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) to brain extracts from dissected third-instar brat-null larvae homozygous for the fruC::Myc knock-in allele. brat-null brains accumulate thousands of supernumerary type II neuroblasts at the expense of INPs and provide a biologically relevant source of type II neuroblast-specific chromatin (Komori et al., 2014a; Janssens et al., 2017; Komori et al., 2018; Rives-Quinto et al., 2020; Larson et al., 2021). We used a specific antibody against the Myc epitope or the Fru-common antibody to confirm that FruC::Myc is detected in all supernumerary type II neuroblasts in brat-null brains homozygous for fruC::Myc (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A). We determined the genome-wide occupancy of FruC::Myc in type II neuroblasts using the Myc antibody and Fru-common antibody, and found that FruC::Myc binding patterns revealed by these two antibodies are highly correlated (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B; Pearson correlation = 0.94). FruC binds 9301 regions in type II neuroblasts (Figure 3A). Overall, 59% of FruC-bound regions are promoters whereas 29% are enhancers in the intergenic and intronic regions (Figure 3A). By contrast, 15% of randomized control regions are promoters and 55% are enhancers (Figure 3A). 50.1% of FruC-bound regions in promoters and enhancers overlap with regions of accessible chromatin (Larson et al., 2021; Figure 3B). Consistent with the finding that FruC negatively regulates stemness gene expression, FruC binds promoters and neuroblast-specific enhancers of Notch, dpn, E(spl)mγ, klumpfuss (klu) and tailless (tll) that were previously shown to maintain type II neuroblasts in an undifferentiated state (Figure 3C; Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). Based on our scRNA-seq data, we classified genes as NB genes, imm INP genes, or invariant genes expressed throughout the lineage based on differential expression within cluster 14 (Figure 1E; Supplementary file 2). Seventy-four percent of genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts (NB genes) are bound by FruC whereas 41% of these genes are in randomized control (Figure 3D–E). By contrast, the percentage of FruC-bound genes transcribed in immature INPs or throughout the type II neuroblast lineage is similar to random control (Figure 3D–E). Because stemness gene transcripts are highly enriched in type II neuroblasts, these results suggest that FruC preferentially binds cis-regulatory elements of stemness genes.

Figure 3. Fruc preferentially binds regulatory elements of genes uniquely expressed in neuroblasts.

(A) Genomic binding distribution of FruC-bound peaks (total # of peaks shown in parentheses) from CUT&RUN or random (set of Fruc peaks shuffled to randomly determined places in the genome) in type II neuroblast-enriched chromatin from brat-null brains (brat11/Df(2L)Exel8040). Fruc preferentially binds promoters. (B) Heatmap is centered on promoters or regulatory regions showing accessible chromatin as defined by ATAC-seq with 500 bp flanking regions and ordered by signal intensity of Fruc::Myc binding. (C) Representative z score-normalized genome browser tracks showing regions with accessible chromatin (ATAC-seq) and bound by Fruc::Myc (detected by the Myc antibody or FruCOM antibody), Su(H), Trl, or IgG at Notch, dpn, and E(spl)mγ loci. (D) Genes in cluster 14 from the scRNA-seq dataset were separated into neuroblast-enriched genes (right), immature INP-enriched genes (left), and invariant genes. The middle circle is the set of genes bound by Fruc or Su(H) (shown in parentheses). UMAPs show gene enrichment score for Fruc-bound genes uniquely expressed in neuroblasts (right), uniquely expressed in immature INPs (left), and ubiquitously expressed (invariant genes) (middle). (E) Percentage of genes defined in D bound by either Fruc, Su(H), random Fruc peaks, or random Su(H) peaks (set of Su(H) peaks shuffled to randomly determined places in the genome). (F–G) Genomic binding distribution of identified Su(H)-bound peaks (total # of peaks shown in parentheses) from CUT&RUN in type II neuroblast-enriched chromatin. Heatmap is centered on promoters or regulatory regions and ordered by signal intensity of Su(H) binding. (H–I) Genomic binding distribution of identified Trl-bound peaks (total # of peaks shown in parentheses) from CUT&RUN in type II neuroblast-enriched chromatin. Heatmap is centered on promoters or regulatory regions and ordered by signal intensity of Trl binding.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Quality control for determining FruC-, Su(H)- and Trl-binding using CUT&RUN.

A mechanism by which FruC can negatively regulate stemness gene expression levels is to modulate the activity of the Notch transcriptional activator complex activity. Using Affymetrix GeneChip, a previous study demonstrated that the Notch transcriptional activator complex binds 595 regions in 185 transcribed genes in neuroblasts (log2 FC >0.5) including dpn, E(spl)mγ, klu, and tll (Zacharioudaki et al., 2016). To precisely identify Notch-bound peaks in type II neuroblasts, we used a specific antibody against the DNA-binding subunit of the Notch transcriptional activator complex, Suppressor of Hairless (Su(H)), to perform a CUT&RUN assay on brain lysate form third-instar brat-null larvae homozygous for fruC::Myc. Prior to the genomic study, we validated the specificity of the Su(H) antibody in vivo by performing immunofluorescent staining of brat-null larvae homozygous for fruC::Myc. We observed co-expression of Su(H) and Dpn in thousands of supernumerary type II neuroblasts in brat-null brains (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). Because dpn is directly activated by Notch in many cell types, including neuroblasts, this result confirms that the Su(H) antibody can detect activated Notch activity. We found that Su(H) binds 305 regions in 112 genes in type II neuroblasts, and that Su(H)-bound regions are predominantly in promoters and enhancers (Figure 3F). Twelve percent of NB genes are bound by Su(H) compared to 0% of these gene in a randomized control (Figure 3D–E). By contrast, the percentage of Su(H) bound genes transcribed in immature INPs or throughout the type II neuroblast lineage are similar to random control. Overall, 95.2% of Su(H)-bound promoters and 90.8% of Su(H)-bound enhancers overlap with FruC-bound peaks (Figure 3G). These peaks include the promoters of Notch, dpn, E(spl)mγ, klu and tll as well as the enhancers that drive their expression in neuroblasts (Figure 3C; Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). Our data support a model that FruC regulates Notch pathway gene expression by occupying functionally relevant regulatory elements bound by Notch in type II neuroblasts.

De novo motif discovery identified a sequence bound by the transcription factor Trithorax-like (Trl), also known as GAGA factor, is significantly enriched in both FruC-bound promoters and enhancers (Figure 3—figure supplement 1E). The Trl motif was previously found to be the most significantly enriched in FruC-associated genomic regions in the larval nervous system (Neville et al., 2014). Trl, like Fru, is a member of the BTB-Zn-finger transcription factor family which heterodimerize with other BTB-domain-containing factors to regulate gene transcription (Bonchuk et al., 2022). Trl is an evolutionarily conserved multifaceted transcription factor that regulates diverse biological processes by interacting with a wide variety of proteins including PRC2 complex components (Lomaev et al., 2017; Chetverina et al., 2021; Srivastava et al., 2018). Although the Trl motif is generally enriched at promoters, enrichment of this motif in FruC-bound promoters and enhancers suggest that FruC might function together with Trl to negatively regulate gene transcription in type II neuroblasts. We examined whether Trl indeed binds FruC-bound regions in type II neuroblasts using a specific antibody against Trl (Judd et al., 2021). We validated the specificity of the Trl antibody in vivo by performing immunofluorescent staining of brat-null larvae homozygous for fruC::Myc. We found that Trl is highly enriched in the nuclei of thousands of supernumerary type II neuroblasts marked by Dpn expression (Figure 3—figure supplement 1F). We used the Trl antibody to perform a CUT&RUN assay on brain lysate from third-instar brat-null larvae homozygous for fruC::Myc. We identified 1435 Trl-bound regions, including promoters and enhancers, in type II neuroblasts (Figure 3H). In total, 85.4% of Trl-bound promoters and 87.8% of Trl-bound enhancers overlapped with FruC-bound regions including Notch, dpn, E(spl)mγ, klu and tll loci (Figure 3C and I; Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). These data suggest that FruC may function together with Trl to regulate the transcription of stemness genes in neuroblasts.

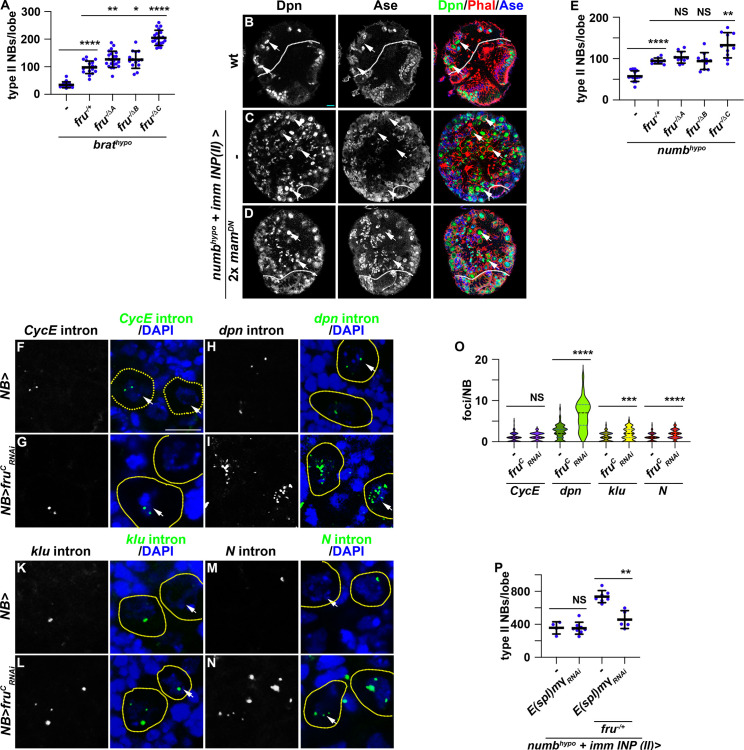

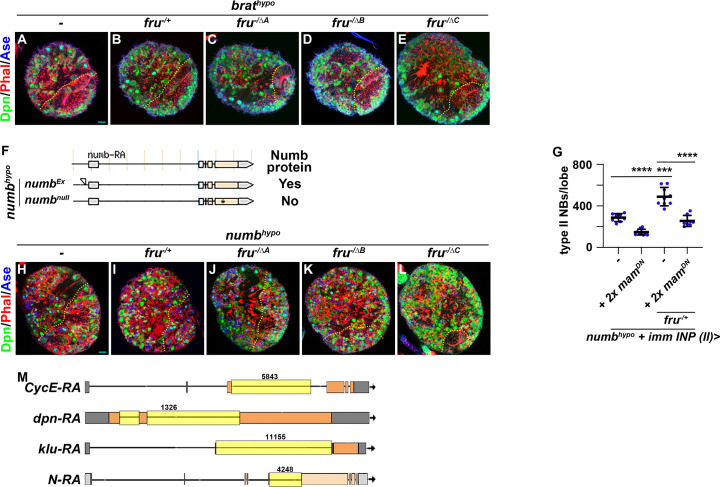

FruC fine-tunes the transcription of Notch pathway genes during asymmetric neuroblast division

Loss- and gain-of-function of fruC mildly alters the expression of Notch downstream-effector genes that promote stemness in neuroblasts (Figure 2). Thus, FruC likely fine-tunes Notch signaling activity levels that balance neuroblast maintenance and INP commitment during neuroblast asymmetric division. To functionally validate the role of FruC in fine-tuning Notch pathway activity expression, we tested whether loss of fruC function can enhance the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in brat-hypomorphic (brathypo) brains. Immature INPs revert to supernumerary type II neuroblasts at low frequency due to a modest increase in Notch downstream-effector gene expression in brathypo brains (Komori et al., 2018). Consistent with the finding that reduced fru function increases Notch downstream-effector protein levels in immature INPs, the heterozygosity of a fru deletion (fru-/+) enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in brathypo brains (Figure 4A; Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–B). Furthermore, brathypo brains lacking fruC function displayed greater than a twofold increase in supernumerary neuroblasts compared with brathypo brains heterozygous for a fru deletion (Figure 4A; Figure 4—figure supplement 1C–E). These data support our model that loss of fruC function increases Notch pathway activity levels during asymmetric neuroblast division.

Figure 4. Reduced fru function increases Notch pathway gene transcription.

(A) Loss of fruC function (fruΔC/Aj96u3) enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in brathypo (bratDG19310/11) brains heterozygous for a fru deletion (fruAj96u3/+), but loss of fruA (fruΔA/Aj96u3) or fruB (fruΔB/Aj96u3) function does not. (B–D) Overexpressing two copies of dominant-negative mam transgenes in immature INPs partially suppresses the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo (numbex112/15) brains. The genotype used in this experiment is numbEx112/R9D11-Gal4,numb15 or numbEx112/R9D11-Gal4,numb15; UAS-mamDN/UAS-mamDN. (E) Loss of fruC function (fruΔC/Aj96u3) enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains heterozygous for a fru deletion (fruAj96u3/+), but loss of fruA (fruΔA/Aj96u3) or fruB (fruΔB/Aj96u3) function does not. (F–N) sm-FISH using intron probes confirms increased Notch and Notch target gene (dpn and klu) transcription in fruC-mutant neuroblasts comparing with control neuroblasts. CycE nascent transcripts serve as a control because CycE is not a Notch target gene, and CycE transcription is unaffected by fruC knockdown. The genotype used in this experiments is Wor-Gal4 or Wor-Gal4/UAS-fruCRNAi (O) Quantification of Notch, dpn, klu and CycE nascent transcript foci in control versus fruC-mutant neuroblasts. sm-FISH signals were counted in 8 dorsal-most neuroblasts (>6 μm in diameter) per brain lobe. CycE: 1±0.97 (n=128 neuroblasts) in control; 1.16±0.91 (n=96 neuroblasts) in fruCRNAi. dpn: 2.33±1.65 (n=88 neuroblasts) in control; 6.52±3.55 (n=104 neuroblasts) in frucRNAi. klu: 1.12±1.01 (n=80 neuroblasts) in control; 1.79±1.43 (n=112 neuroblasts) in frucRNAi. Notch: 1.06±0.88 (n=112 neuroblasts) in control; 1.77±1.07 (n=104 neuroblasts) in frucRNAi. (P) Knocking down E(spl)mγ function by RNAi in immature INPs suppresses increased supernumerary formation in numbhypo brains heterozygous for fru while having no effect on numbhypo brains alone. The genotypes used in this experiment are numbEx112/R9D11-Gal4,numb15; UAS-E(spl)mγRNAi/+ or numbEx112/R9D11-Gal4,numb15; UAS-E(spl)mγRNAi/fruAj96u3/+. White dashed line separates brain from the optic lobe. Yellow dashed line encircles a neuroblast. white arrow: type II neuroblast. Scale bars: 10 μm. p-value: NS: non-significant, *<0.05, **<0.005, ***<0.0005, and ****<0.00005.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Loss of fruC function enhances supernumerary neuroblast formation in brathypo and numbhypo brains.

Because FruC occupies enhancers relevant to the cell-type-specific expression of Notch and Notch downstream-effector genes in type II neuroblasts (Figure 3), we assessed whether FruC fine-tunes the expression of Notch signaling pathway components during asymmetric neuroblast division. Proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular domain and the transmembrane fragment releases the Notch intracellular domain to form a transcriptional activator complex by binding Su(H) and Mastermind (Mam) (Bray and Gomez-Lamarca, 2018). Asymmetric segregation of Numb into immature INPs inhibits continual Notch activation and terminates Notch-activated transcription of its downstream-effector genes. numb-hypomorphic (numbhypo) animals carrying the numbEx allele in trans with a numb-null allele (numb15) contain more than 100 type II neuroblasts per brain lobe compared with 8 per lobe in wild-type animals (Figure 4B–C; Figure 4—figure supplement 1F–G). Antagonizing Notch-activated gene transcription by overexpressing a dominant negative form of Mam (MamDN) in immature INPs suppressed the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains (Figure 4C–D; Figure 4—figure supplement 1G). Thus, the supernumerary type II neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains provides a direct functional readout of activated Notch levels during asymmetric neuroblast division. The heterozygosity of a fru deletion alone did not affect INP commitment in immature INPs but led to a twofold increase in supernumerary neuroblasts in numbhypo brains (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 1H–I). Complete loss of fruC function (fru-/ΔC) led to increased supernumerary neuroblast formation in numbhypo brains compared with fru-/+ (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 1J–L). These results suggest that loss of fruC function increases Notch-activated gene expression in mitotic neuroblasts, and support a model that FruC fine-tunes the transcription of Notch downstream-effector genes in neuroblasts.

To quantitatively evaluate whether FruC fine-tunes Notch and Notch downstream-effector gene transcription in neuroblasts, we performed single-molecule fluorescent in-situ hybridization (sm-FISH) using intron probes to these transcripts in larval brains overexpressing a fruCRNAi transgene. Intron probes detect nascent transcripts allowing for quantitative measurement of gene transcription in the physiological context. Because Cyclin E (CycE) is not a Notch target, its nascent transcript levels should not be affected by alerted Notch signaling and serve as control in this experiment. Consistently, the number of CycE nascent transcript foci in neuroblasts appears statistically indistinguishable between control brains carrying only the Gal4 driver or brains overexpressing fruCRNAi (Figure 4F–G and O). By contrast, the number of Notch, dpn and klu nascent transcript foci is significantly higher in fruC knockdown brains than in control brains (Figure 4H–O). E(spl)mγ was exempted from this analysis because its open reading frame contains a single exon. These results strongly suggest that reduced fruC function increases Notch and Notch downstream-effector gene transcription levels in neuroblasts. Consistent with this interpretation, knocking down the function of E(spl)mγ by RNAi strongly suppressed increased supernumerary neuroblast formation in numbhypo brains heterozygous for fru while not effecting the baseline supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains (Figure 4P). The dpnRNAi transgene was exempted from this analysis because of off-target effect. This result provides functional support of our model that reducing fruC function increases Notch target gene transcription in neuroblasts. Thus, we conclude that FruC fine-tunes Notch and Notch downstream-effector gene expression during asymmetric neuroblast division.

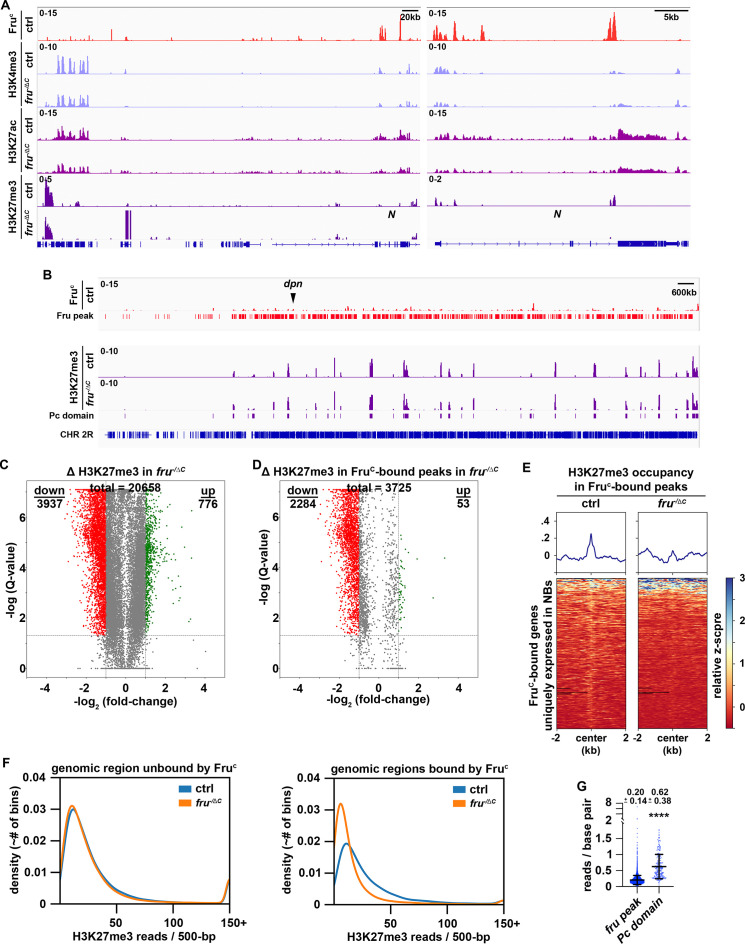

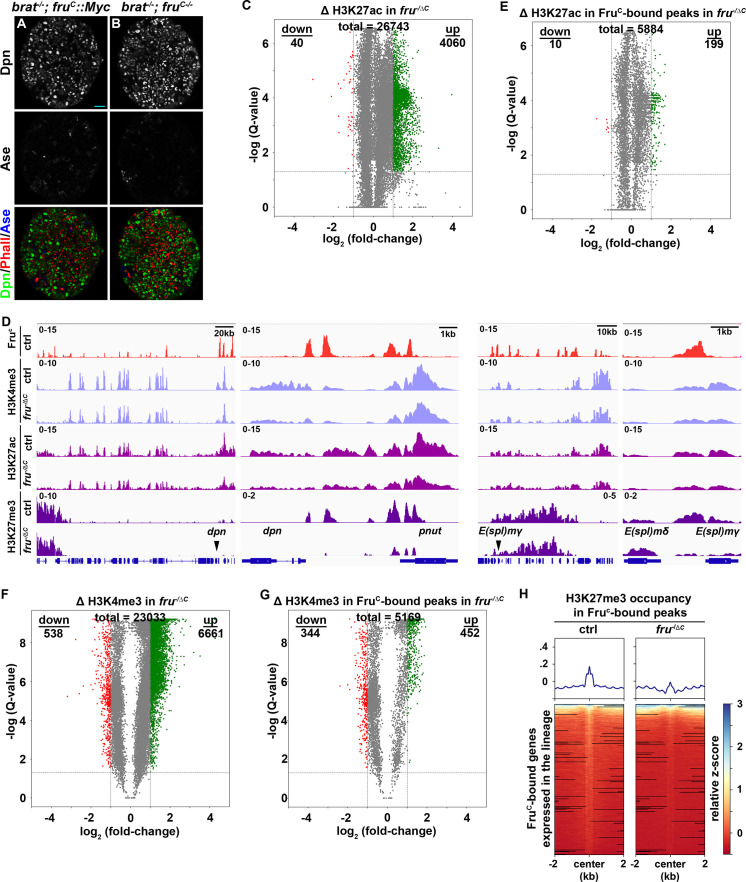

FruC fine-tunes gene expression by promoting low-level H3K27me3 enrichment

To define the mechanisms by which FruC fine-tunes Notch pathway gene transcription in mitotic neuroblasts, we compared genome-wide patterns of histone marks by CUT&RUN in brat-null brains carrying a fru-/ΔC allelic combination (fruC-null) with that of brat-null brains alone (control) (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A–B). We used a 500 bp sliding window to search for regions that show changes in histone mark levels with a Q-value <0.05 in fruC-null brains relative to control brains. We first focused on acetylated lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27ac) because a previous study suggested that FruC functions through Histone deacetylase 1 (Hdac1) to regulate gene transcription during specification of sexually dimorphic neurons (Ito et al., 2012). If FruC fine-tunes Notch, dpn and E(spl)mγ transcription in type II neuroblasts by promoting deacetylation of H3K27 at their promoters and neuroblast-specific enhancers, these loci should display higher H3K27ac levels in fruC-null brains than in control brains. 14.2% (4139 kB / 29,065 kB) of the regions with statistically significant changes in H3K27ac levels genome-wide displayed greater than twofold increase in this histone mark in fruC-null brains while 0.4% (130 kB / 29,065 kB) of these regions showed greater than twofold decrease (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C). 3.4% (306 kB / 8,870 kB) of FruC-bound regions showed greater than 2-fold increase in H3K27ac levels in fruC-null brains, and these regions did not include the cis-regulatory elements and the bodies of Notch, dpn and E(spl)mγ (Figure 5A; Figure 5—figure supplement 1D–E). Thus, loss of fruC function did not significantly increase the number of FruC-bound loci with greater than 2-fold increase in H3K27ac comparing with the genome overall. We conclude that H3K27 deacetylation likely plays a minor role in FruC-mediated fine-tuning of target gene transcription.

Figure 5. Low levels of H3K27me3 are enriched in FruC-bound regions.

(A) Representative z score-normalized genome browser tracks showing FruC-binding and the enrichment of H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 at the Notch locus in type II neuroblasts in control (brat11/Df(2L)Exel8040) or fruC-null (brat11/Df(2L)Exel8040; fruΔC/Aj96u3) brains. Left: Zoomed-out images showing nearest heterochromatin domains. Right: Zoomed-in images showing enrichment of histone marks in FruC-bound regions. (B) Representative z score-normalized genome browser track showing FruC-binding and the H3K27me3 throughout the chromosome arm 2 R in type II neuroblasts in control or fruC-null brains. Fru peaks are shown along with Pc domain regions called on data using similar strategy as previously used to call canonical Pc domains (Brown et al., 2018). (C) Volcano plot showing fold-change of H3K27me3 signal in overall genomic regions in fruC-null brains versus control brains. (D) Volcano plot showing fold-change of H3K27me3 signal in regions bound by Fruc in fruC-null brains versus control brains. (E) Heatmaps are centered on Fruc summits with 2 kb flanking regions in genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts in control or fruC-null brains and ordered by signal intensity of H3K27me3 enrichment calculated from TMM-normalized tracks. (F) Left: Density plots showing proportion of all 500 bp regions in the genome not bound by Fruc covered by different amounts of H3K27me3 reads in fruC-null brains vs control brains. Right: Density plots showing proportion of all 500 bp Fruc bound regions covered by different amounts of H3K27me3 reads in fruC-null brains vs control brains. (G) Dotplot representing coverage of each Fruc peak not in Pc domains vs coverage of each Pc domain. The horizontal line in the volcano plot represents -log10(0.05)=1.301. All genes above this line have a FDR <0.05.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Levels of active histone marks are unchanged FruC-bound regions.

H3K4me3 is a chromatin mark associated with the promoters of actively transcribed genes (Cenik and Shilatifard, 2021). If FruC fine-tunes Notch, dpn and E(spl)mγ transcription in type II neuroblasts by promoting demethylation of H3K4 at their promoters, these loci should display higher H3K4me3 levels in fruC-null brains than in control brains. 26.7% (8788 kB / 32,939 kB) of the regions with statistically significant changes in H3K4me3 levels genome-wide displayed greater than twofold increase in fruC-null brains while 4.2% (1391 kB / 32,939 kB) of these regions showed greater than 2-fold decrease (Figure 5—figure supplement 1F). 7.45% (831 kB / 11,149 kB) of FruC-bound regions showed greater than 2-fold increase in this histone mark in fruC-null brains, and these regions did not include the promoters and the bodies of Notch, dpn, and E(spl)mγ (Figure 5A; Figure 5—figure supplement 1D and G). Thus, loss of fruC function did not significantly increase the number of FruC-bound loci with greater than twofold increase in H3K4me3 comparing with the genome overall. We conclude that H3K4 demethylation unlikely plays a role in FruC-mediating fine-tuning of gene transcription.

High levels of H3K27me3 are associated with inactive enhancers and the body of repressed genes (Laugesen et al., 2019; Piunti and Shilatifard, 2021). Low H3K27me3 levels occur in active loci in human and mouse embryonic stem cells but are generally regarded as noise (Mikkelsen et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2007). If FruC fine-tunes Notch, dpn and E(spl)mγ transcription in type II neuroblasts by promoting trimethylation of H3K27 at their neuroblast-specific enhancers, these loci should display lower H3K27me3 levels in fruC-null brains than in control brains. High levels of H3K27me3 are deposited in broad domains that are frequently referred to as Polycomb domains (Pc domains) (Brown et al., 2018). Pc domains rarely overlapped with FruC-bound loci and did not appear to be disrupted in fruC-null brains (Figure 5B). 5.7% (1429 kB / 24,888 kB) of the regions with statistically significant changes in H3K27me3 levels displayed greater than twofold increase in fruC-null brains and 18.1% (4510 kB / 24,888 kB) of these regions showed greater than 2-fold decrease (Figure 5C). Importantly, 43.3% (2748 kB / 6,340 kB) of FruC-bound regions showed greater than twofold decrease in this histone mark in fruC-null brains (Figure 5D–E; Figure 5—figure supplement 1H). Thus, loss of fruC function significantly increases the number of FruC-bound loci with greater than twofold decrease in H3K27me3 comparing with the genome overall. We conclude that H3K27 trimethylation likely plays an important role in FruC-mediating fine-tuning of gene transcription.

H3K27me3 levels at FruC-bound peaks including Notch and Notch downstream-effector gene loci appear significantly lower than those in Pc domains in control brains suggesting that FruC fine-tunes gene transcription by promoting low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment (Figure 5A–B; Figure 5—figure supplement 1D). To unbiasedly assess H3K27me3 levels at FruC-bound peaks, we compared the distribution of H3K27me3 reads in 500 bp bins throughout the genome versus FruC-bound peaks. The distribution of reads throughout the genome does not appreciably change between fruC-null brains and control brains (Figure 5F). Consistent with FruC promoting H3K27me3 deposition at regions bound by FruC, there are many more bins that overlapped with FruC-bound peaks containing a reduced number of reads in fruC-null brains comparing with control brains (Figure 5F). We compared the coverage (reads/bp) of H3K27me3 in FruC-bound peaks to canonically defined Pc domains in neuroblasts, and found that Fruc peaks had 3-fold less coverage of H3K27me3 than canonical Pc domains (Figure 5G). These results indicate that FruC fine-tunes gene transcription by promoting low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment.

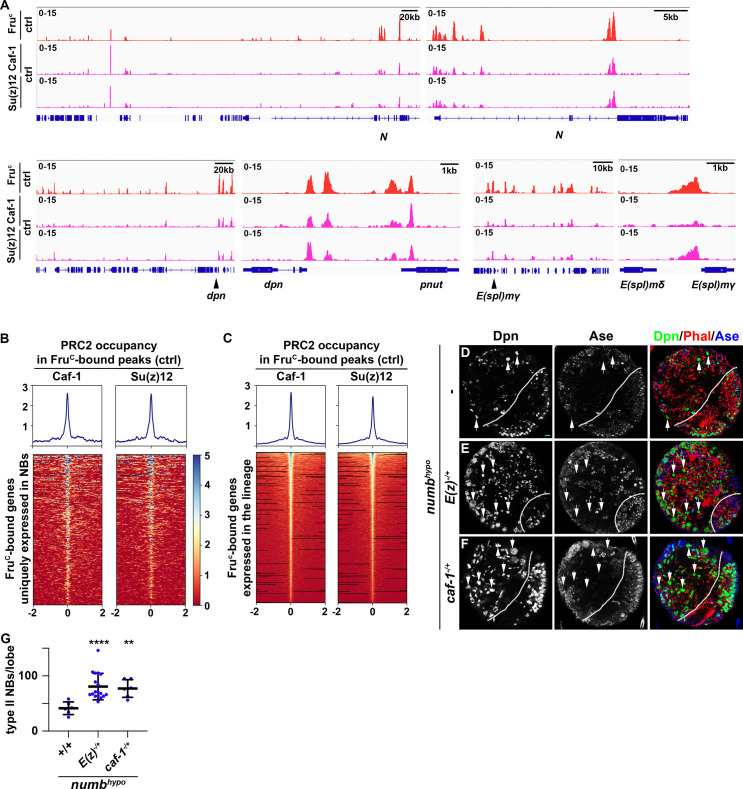

PRC2 fine-tunes gene expression during asymmetric neuroblast division

PRC2 is thought to be the only enzymatic complex that catalyzes H3K27me3 deposition (Laugesen et al., 2019; Piunti and Shilatifard, 2021). If FruC functions through low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment to finely tune Notch, dpn, and E(spl)mγ expression in mitotic neuroblasts, PRC2 core components should be enriched in FruC-bound peaks in type II neuroblasts and reducing PRC2 activity should enhance the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains, identical to the result obtained by reducing fru function. Suppressor of zeste 12 (Su(z)12) and Chromatin assembly factor 1, p55 subunit (abbreviated as Caf-1) are two of the PRC2 core components. We performed CUT&RUN in control brains to determine whether regions enriched with Su(z)12 and Caf-1 overlap with FruC-bound peaks. We found that FruC-bound cis-regulatory elements in Notch, dpn, and E(spl)mγ display enrichment of Su(z)12 and Caf-1 (Figure 6A). Furthermore, most FruC-bound peaks in genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts show Su(z)12 and Caf-1 enrichment (Figure 6B). Similarly, most FruC-bound peaks in genes transcribed throughout the type II neuroblast lineage also shows Su(z)12 and Caf-1 enrichment (Figure 6C). These data support our model that FruC functions through low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment to finely tune gene transcription in type II neuroblasts. Reducing PRC2 function alone does not lead to supernumerary neuroblast formation but strongly enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains, identical to the results obtained by reducing fru function (Figure 6D–G; Figure 4—figure supplement 1A). Thus, reducing PRC2 activity increases activated Notch during asymmetric neuroblast division. These data led us to propose that FruC functions together with PRC2 to finely tune gene expression in mitotic neuroblasts by promoting low-level enrichment of repressive histone marks in cis-regulatory elements.

Figure 6. PRC2 subunits bind a high percentage of neuroblast-specific genes.

(A) Representative z score-normalized genome browser tracks showing regions bound by FruC, Su(z)12, and Caf-1 in type II neuroblasts in control (brat11/Df(2L)Exel8040) brains. Left: Zoomed-out images of the loci. Right: Zoomed-in images showing enrichment of PRC2 subunits in FruC-bound regions. (B–C) Heatmaps are centered on Fruc summits with 2 kb flanking regions in genes uniquely transcribed in type II neuroblasts in control brains and ordered by average signal intensity of Caf-1 and Su(z)12. Heatmap intensity is calculated from z score-normalized tracks. (D–F) The heterozygosity of E(z) (E(z)731/+) or Caf-1 (Caf-1short/+) enhances the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo (numbex112/15) brains. (G) Quantification of total type II neuroblasts per brain lobe in numbhypo (numbex112/15) brain alone or heterozygous for E(z) (E(z)731/+) or Caf-1 (Caf-1short/+).Scale bars: 10 μm.

Discussion

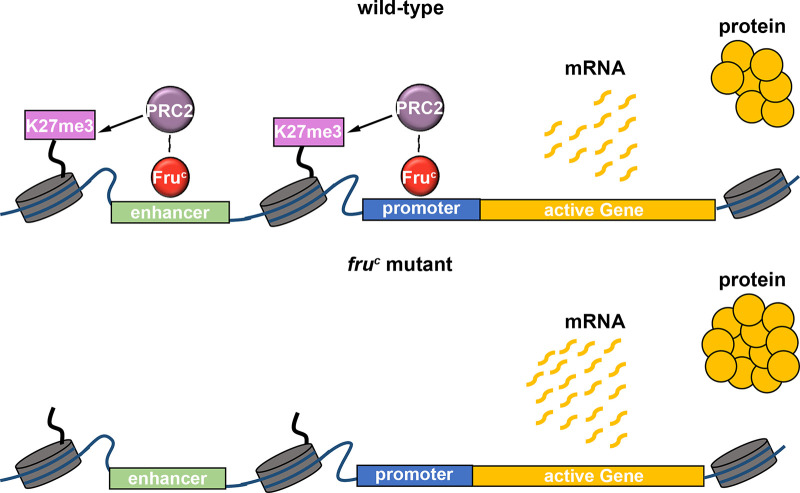

Regulation of gene expression requires transcription factors and their associated chromatin-modifying activity, and a lack of insights into relevant transcription factors has precluded mechanistic investigations of gene expression by fine-tuning. By taking advantage of the well-established cell type hierarchy and sensitized genetic backgrounds in the type II neuroblast lineage, we demonstrated FruC fine-tunes gene expression in neuroblasts. By focusing on the Notch signaling pathway in type II neuroblasts, we have been able to define generalizable mechanisms by which FruC finely tunes gene expression levels using loss- and gain-of-function analyses. Our data indicate that FruC likely functions together with PRC2 to dampen the expression of specific genes in mitotic neuroblasts by promoting low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment at their enhancers and promoters (Figure 7). We propose that local low-level enrichment of repressive histone marks can act to fine-tune gene expression.

Figure 7. FruC likely functions together with PRC2 to dampen the expression of stemness genes by promoting low levels of H3K27me3 at their cis-regulatory elements.

Loss of fruC functions leads to reduced repressive histone marks and increased stemness gene expression in neuroblasts.

Fru is a multifaceted transcriptional regulator of gene expression

Fru protein isoforms have been detected in many cell types in flies (Ito et al., 1996; Ryner et al., 1996; Djiane et al., 2013; Michki et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Dillon et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). The role of Fru in stem cell differentiation remained undefined. Studies linking Fru isoform-specific DNA-binding across the genome with Fru function have been confounded by multiple issues. These include the co-expression of multiple isoforms with different binding specificities within the same cell types, as well as the heterogeneity and scarcity of cell types which express Fru within the central brain, where male-specific Fru isoforms (FruM) have been most intensely studied (Goodwin and Hobert, 2021). In this study, the identification of FruC as the sole isoform expressed in type II neuroblasts along with the use of brat-null brains, which are highly enrich for these neuroblasts, has enabled the study of FruC genomic binding in a defined cell type where it is known to be expressed. By using gene activity in the Notch pathway as an in vivo functional readout, we have now been able to link genomic and genetic evidence to identify a clear role for FruC in negatively regulating the expression of FruC-target genes during asymmetric neuroblast division (Figures 3 and 4). Our data strongly correlate the downregulation of Notch and Notch downstream-effector gene activity by FruC to PRC2-mediated low-level enrichment of H3K27me3 (Figures 5 and 6). This mechanistic correlation appears to be broadly applicable to genes that promote stemness or prime differentiation in neuroblasts (Figure 3D and E). These data led us to propose a model in which FruC functions together with PRC2 to fine-tune the expression of genes by promoting low-level enrichment of H3K27me3 at their cis-regulatory elements. Transcriptomic analyses have revealed that fru transcripts are enriched in fly renal stem cells in which Notch signaling plays an important role in regulating their stemness (Xu et al., 2022). We speculate that the mechanisms we have described in this study might be applicable to the regulation of gene expression in the renal stem cell lineage. It will also be interesting to investigate whether the male-specific FruMC isoform, having the same DNA-binding specificity, utilizes a similar mechanism to regulate the multitude of developmental programs throughout the brain that contribute to a sexually dimorphic nervous system.

Mechanisms that fine-tune gene transcription

What mechanisms allow transcriptional factors to promote inactivation of gene transcription vs. the fine-tuning of their expression? In the type II neuroblast lineage, transcription factors Erm and Hamlet (Ham) function together with histone deacetylases to sequentially inactivate type II neuroblast functionality genes including tll and pointed during INP commitment (Weng et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2011; Eroglu et al., 2014; Janssens et al., 2014; Koe et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2016; Hakes and Brand, 2020; Rives-Quinto et al., 2020). In erm- or ham-null brains, Notch reactivation ectopically activates type II neuroblast functionality gene expression in INPs, driving their reversion into supernumerary neuroblasts. Importantly, mis-expressing either gene overrides activated Notch activity in neuroblasts, and drives them to prematurely differentiate into neurons. Thus, Erm- and Ham-associated histone deacetylation can robustly counteract activity of the Notch transcriptional activator complex and inactivate Notch downstream-effector gene transcription. In contrast to Erm and Ham, FruC appears to reduce activity of the Notch transcriptional activator complex instead. Loss of fruC function modestly increases Notch activity in mitotic type II neuroblasts leading to moderately higher levels of Notch activity and Notch downstream-effector gene expression in immature INPs (Figure 4A and E). Ectopic Notch activity in immature INPs due to loss of fruC function can be efficiently buffered by the multilayered gene control mechanism and does not perturb the onset of INP commitment (Figure 2F–I). Furthermore, neuroblasts continually overexpressing FruC for 72 hours maintained their identities, despite displaying a reduced cell diameter and expressing markers that are typically diagnostic of Ase+ immature INPs (Figure 2J–L). These results suggest that FruC dampens rather than overrides activated Notch activity and are consistent with the findings that FruC-bound regions displaying little changes in histone acetylation levels between fruC-null and control neuroblasts (Figure 4—figure supplement 1C–D). Thus, transcriptional repressors that inactivate gene transcription render the activity of transcriptional activators ineffective, whereas transcriptional repressors that fine-tune gene expression dampen their activity.

A key follow-up question on a proposed role for FruC in fine-tuning gene expression in neuroblasts is the mechanistic link between this transcriptional repressor and the dampening of gene transcription. A previous study suggested that Fru functions through Heterochromatin protein 1a (Hp1a) to promote gene repression during the specification of sexually dimorphic neurons (Ito et al., 2012). Hp1a catalyzes deposition of the H3K9me3 mark (Eissenberg and Elgin, 2014). FruC-bound genes in neuroblasts display undetectable levels of H3K9me3, and knocking down hp1a function did not enhance the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains (data not presented). Thus, it is unlikely that FruC finely tunes gene transcription by promoting H3K9me3 enrichment. A small subset of FruC-bound peaks showed increased enrichment of H3K27ac in neuroblasts in fruC-null brains compared with control brains (Figure 4—figure supplement 1D). However, FruC overexpression mildly reduces activity of the Notch transcriptional activator complex in neuroblasts (Figure 2J–L). Thus, histone deacetylation appears to play a minor role in FruC-mediated fine-tuning of gene expression in neuroblasts. Most peaks that displayed statistically significantly reduced H3K27me3 levels in fruC-null neuroblasts compared with control neuroblasts are bound by FruC (Figure 5E). Many FruC-bound peaks displayed the enrichment of PRC2 subunits, Su(z)12 and Caf-1, and reduced PRC2 function enhanced the supernumerary neuroblast phenotype in numbhypo brains (Figure 6D–G; Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). These results strongly suggest a model in which low-level enrichment of H3K27me3 in cis-regulatory elements of FruC-bound genes fine-tunes their expression in neuroblasts (Figure 7).

PRC2 fine-tunes gene transcription during developmental transitions

A counterintuitive finding from this study is the role for PRC2 and low levels of H3K27me3 enrichment in fine-tuning active gene transcription in type II neuroblasts. PRC2 is thought to be the only complex that deposits the H3K27me3 repressive histone mark and functions to repress gene transcription (Laugesen et al., 2019; Morgan and Shilatifard, 2020; Piunti and Shilatifard, 2021). PRC2 subunits and H3K27me3 are enriched in many active genes in various cell types, including embryonic stem cells and quiescent B cells in mice and human differentiating erythroid cells (Brookes et al., 2012; Frangini et al., 2013; Kaneko et al., 2013; Morey et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2015; Giner-Laguarda and Vidal, 2020; Ochiai et al., 2020). However, the functional significance of their occupancies in active gene loci in vertebrate cells remains unclear due to a lack of sensitized functional readouts and a lack of insight regarding transcription factors for their recruitment. Several similarities exist between these vertebrate cell types and fly type II neuroblasts. First, both vertebrate and fly cells are poised to undergo a cell-state transition. Second, the pattern of PRC2 subunit occupancy in cis-regulatory elements of active vertebrate and fly genes appears as discrete peaks that are also enriched with low levels of H3K27me3. Building on the functional evidence collected in vivo, we propose that FruC functions together with PRC2 to fine-tune the expression of genes that promote stemness or prime differentiation by promoting low-level enrichment of H3K27me3 in their cis-regulatory elements in type II neuroblasts (Figure 7). Thus, PRC2-mediated low-level enrichment of H3K27me3 we have described in this study should be broadly applicable to the fine-tuned gene activity attained by dampening transcription during binary cell fate specification and cell-state transitions in vertebrates.

An important question arising from our proposed model relates to how FruC functions together with PRC2 to dampen gene transcription in neuroblasts. Studies in vertebrates have shown that loss of PRC2 activity mildly increases gene transcription levels, suggesting that PRC2 likely dampens gene transcription (Morey et al., 2013; Pherson et al., 2017). A separate study suggested a possible link between PRC2 and transcriptional bursts (Ochiai et al., 2020). The transcriptional activator complex binding to promoters affects burst sizes, whereas their binding to enhancers control burst frequencies (Larsson et al., 2019). The dwell time of the transcriptional activator complex bound to cis-regulatory elements directly affects the frequency, duration, and amplitude of transcriptional bursts. For example, chromatin immunoprecipitation and live-cell imaging of fly embryos have suggested that the Su(H) occupancy time at cis-regulatory elements of Notch downstream-effector genes increases upon Notch activation (Gomez-Lamarca et al., 2018). Our genomic data indicate that Su(H)-bound regions in Notch and Notch downstream-effector genes that promote stemness in neuroblasts are bound by FruC and are enriched for low levels of H3K27me3 and PRC2 subunits (Figures 3F–G–5A, 6A). These observations suggest that FruC and PRC2 might fine-tune expression of Notch pathway components by modulating transcriptional bursts in these loci. Examining levels of Su(H) enrichment at FruC-bound peaks in Notch pathway component loci in fruC-null neuroblasts relative to control neuroblasts will enable the testing of this model.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | P{GawB}numbNP2301 | Kyoto Drosophila Stock Center | 104153 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | numbex115 | This study | see "Fly genetics and transgenes" in Material and Methods | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruA::Myc | von Philipsborn et al., 2014 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruB::Myc | von Philipsborn et al., 2014 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruC::Myc | von Philipsborn et al., 2014 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | brat11 | Arama et al., 2000 | stock #: 97265 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | bratDG19310 | Xiao et al., 2012 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | Df(2 L)Exel8040 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 7847 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | numb15 | Berdnik et al., 2002 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | frusat15 | Ito et al., 1996 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruAJ96u3 | Song et al., 2002 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruΔA | Neville et al., 2014 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruΔB | Neville et al., 2014 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | fruΔC | Billeter et al., 2006 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | E(z)731 | Anderson et al., 2011 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | Caf-1short | Anderson et al., 2011 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-fruC::Myc | This study | see "Fly genetics and transgenes" in Material and Methods | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-fruC::ERD::Myc | This study | see "Fly genetics and transgenes" in Material and Methods | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-dcr2; Wor-Gal4, Ase-Gal80; UAS-Stinger::RFP | Reichardt et al., 2018 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | P{GawB}elavC155, P{UAS-mCD8::GFP.L}Ptp4ELL4, P{hsFLP}1 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 5146 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | P{GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 4780 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | y[1] w[*]; P{ry[+t7.2]=neoFRT}82B P{w[+mC]=tubP-GAL80}LL3 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 5135 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | w[1118]; P{y[+t7.7] w[+mC]=GMR9D11-GAL4}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 40731 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-E(spl)mγRNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | stock #: 25978 | |

| Antibody | anti-GFP (chicken polyclonal) |

Aves Labs | Cat# GFP-1010 RRID:AB_2307313 |

IF (1:2000) |

| Antibody | anti-Ase (rabbit polyclonal) | Weng et al., 2010 | IF (1:400) | |

| Antibody | anti-FruCOM (rabbit polyclonal) | Ito et al., 2012 | IF (1:500) CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

|

| Antibody | anti-Trl (rabbit polyclonal) | Judd et al., 2021 | IF (1:500) CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

|

| Antibody | anti-cMyc (mouse polyclonal) |

Sigma | SKU: M4439 | IF (1:200) |

| Antibody | anti-Su(H) (mouse polyclonal) | Santa Cruz | SKU: 398453 | IF (1:100), |

| Antibody | anti-Pros (mouse monoclonal) | Lee et al., 2006a | IF (1:500) | |

| Antibody | anti-dpn (rat monoclonal, ascite) | Weng et al., 2010 | IF (1:1000) | |

| Antibody | anti-Mira (rat monoclonal) | Lee et al., 2006a | IF (1:100) | |

| Antibody | anti-cMyc (goat polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat#: ab9132 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-Caf-1 (rabbit polyclonal) | Tyler et al., 1996 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) | |

| Antibody | anti-Su(z)12 (rabbit polyclonal) | Loubière et al., 2016 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) | |

| Antibody | anti-IgG (rabbit polyclonal) | EpiCypher | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) | |

| Antibody | anti-H3K9me3 (rabbit polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat#: ab8898 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-H3K4me3 (rabbit polyclonal) | Active Motif | Cat#: 39159 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-H3K27me3 (rabbit polyclonal) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#: 07–449 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-H3K27ac (rabbit polyclonal) | Active Motif | Cat#: 39136 | CUT-&-RUN (1 μl) |

| Chemical compound | Rhodamine Phalloidin | Invitrogen | Cat#: R415 | IF (1:100) |

| Chemical compound | Alexa Fluor Plus 405 Phalloidin | Invitrogen | Cat#: A30104 | |

| Chemical compound | DRAQ5 | Abcam | Cat#: ab108410 | |

| Chemical compound | Papain | Millipore Sigma | Cat#: P4762-25MG | |

| Chemical compound | Collagenase type I | Millipore Sigma | Cat#: SCR103 | |

| Chemical compound | E-64 | Millipore Sigma | Cat#: E3132-1MG | |

| Chemical compound | Fetal Bovine Serum | Millipore Sigma | Cat#: F0926-50ML | |

| Chemical compound | Schneider’s Media | Millipore Sigma | Cat#: S0146-500ML | |

| Chemical compound | ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant | Invitrogen | Cat#: P36930 | |

| Chemical compound | ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DNA Stain DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#: P36935 | |

| Chemical compound | Agencourt AMPure XP - 5 mL | Beckman Coulter | Cat#: A63880 | |

| Chemical compound | Sodium butyrate | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#: B5887 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | 10x chromium v3 single-cell gene expression kit | 10x Genomics | Cat# 1000154 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | B1-labeled HCR RNA-FISH intron probe (Notch) | Molecular Instruments, Inc | dm6, chrX: 3159233–3163479 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | B1-labeled HCR RNA-FISH intron probe (dpn) | Molecular Instruments, Inc | dm6, chr2R: 8230502–8231599 & 8231694–8231923 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | B1-labeled HCR RNA-FISH intron probe (klu) | Molecular Instruments, Inc | dm6, chr3L: 10985072–10996227 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | B1-labeled HCR RNA-FISH intron probe (CycE) | Molecular Instruments, Inc | dm6, chr2L: 15731785–15737628 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | HCR RNA-FISH amplifiers | Molecular Instruments, Inc | ||

| Commercial assay or kit | CUTANA ChIC/CUT&RUN Kit | Epicypher | SKU: 14–1048 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | New England Biolabs | Cat#: E7645L | |

| Commercial assay or kit | NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (96 Unique Dual Index Primer Pairs) | New England Biolabs | Cat#: E6440L | |

| Software, algorithm | Script Files | This Study | GITHUB | |

| Software, algorithm | Cell Ranger (6.0.1) | 10x Genomics | RRID:SCR_017344 | |

| Software, algorithm | Fiji/ImageJ | Schindelin et al., 2012 | RRID:SCR_002285 https://fiji.sc/ | |

| Software, algorithm | scanpy scRNA-seq analysis software | Wolf et al., 2018 | RRID:SCR_018139 | |

| Software, algorithm | Harmony | Korsunsky et al., 2019 | ||

| Software, algorithm | Bioinfokit | Renesh Bedre, 2020, March 5 | ||

| Software, algorithm | Matplotlib |

https://zenodo.org/badge/

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.592536.svg |

RRID:SCR_008624 | |

| Software, algorithm | Seaborn | https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03021 | RRID:SCR_018132 | |

| Software, algorithm | FastQC | Wingett and Andrews, 2018 | RRID:SCR_014583 | |

| Software, algorithm | cutadapt | Martin, 2011 | RRID: SCR_011841 | |

| Software, algorithm | Samtools | Li et al., 2009 | RRID: SCR_002105 | |

| Software, algorithm | MACS2 | Zhang et al., 2008 | RRID: SCR_013291 | |

| Software, algorithm | CUT-RUNTools-2.0 | Yu et al., 2021 | ||

| Software, algorithm | bedtools | Quinlan and Hall, 2010 | RRID: SCR_008848 | |

| Software, algorithm | HOMER | Heinz et al., 2010 | RRID: SCR_010881 | |

| Software, algorithm | deeptools | Ramírez et al., 2016 | RRID: SCR_016366 | |

| Software, algorithm | Integrative Genomics Viewer | Robinson et al., 2011 | RRID: SCR_011793 | |

| Software, algorithm | GoPeaks | Yashar et al., 2022 | ||

| Software, algorithm | SICER | Zang et al., 2009 | RRID:SCR_010843 | |

| Software, algorithm | featureCounts | Liao et al., 2014 | RRID: SCR_012919 | |

| Software, algorithm | EdgeR | Robinson et al., 2010 | RRID: SCR_012802 | |

| Software, algorithm | diffReps | Shen et al., 2013 | RRID:SCR_010873 | |

| Software, algorithm | iCisTarget | Imrichová et al., 2015 | ||

| Software, algorithm | XSTREME | Grant and Bailey, 2021 | RRID:SCR_001783 | |

| Software, algorithm | LAS AF | Leica Microsystems | RRID:SCR_013673 |

Fly genetics and transgenes

Fly crosses were carried out in 6-oz plastic bottles at 25 °C, and eggs were collected in apple caps in 8 hr intervals (4 hr for scRNA-seq). Newly hatched larvae were genotyped by presence or absence of the balancer chromosome CyO,Act-GFP and/or TM6B,Tb and cultured on caps containing cornmeal Drosophila culturing media for 96 hr. For GAL4 based overexpression or knock down experiments, larvae were shifted to 33 °C after eclosion to induce transgene expression via suppression of tub-Gal80ts.

Larvae for MARCM analyses (Lee and Luo, 2001) were genotyped after eclosion and allowed to grow at 25 °C for 24 hr. Corn meal caps containing larvae were then placed in a 37 °C water bath for 90 min to induce clones. Heat-shocked larvae were allowed to recover and grow at 25 °C for 72 hr prior to dissection.

For CUT&RUN experiments, fly crosses were carried out in 30oz fly condos, and eggs were collected on 10 mm apple caps in 12 hr intervals. Newly hatched larvae were genotyped and cultured on corn meal caps for ~5–6 days.

The following transgenic lines were generated in this study: UAS-fruC::Myc and UAS-ERD::fruCzf::Myc. The DNA fragments were cloned into p{UAST}attB. The transgenic fly lines were generated via φC31 integrase-mediated transgenesis (Bischof and Basler, 2008). numbEX112 alleles were generated by imprecise excision of P{GawB}numbNP2301, which was inserted at a P-element juxtaposed to the transcription start site of the numb gene. The excised regions were determined by PCR followed by sequencing.

Immunofluorescent staining and antibodies

Larvae brains were dissected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.9), 1 mM EGTA, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1 mM MgSO4 containing 4% formaldehyde for 23 min. Fixed brain samples were washed with PBST containing PBS and 0.3% Triton X-100. After removing fixation solution, samples were incubated with primary antibodies for 3 hrs at room temperature. After 3 hr, samples were washed with PBST and then incubated with secondary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day, samples were washed with PBST and equilibrated in ProLong Gold antifade mount (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antibodies used in this study include chicken anti-GFP (1:2000; Aves Labs, SKU 1020), rabbit anti-Ase (1:400) (Weng et al., 2010), rabbit anti-FruCOM (1:500; D. Yamamoto), rabbit anti-Trl (1:500; J.T. Lis), mouse anti-cMyc (1:200; Sigma, SKU: M4439), mouse anti-Su(H) (1:100; Santa Cruz, SKU: 398453), mouse anti-Pros (1:500) (Lee et al., 2006c), rat anti-Dpn (1:1000) (Weng et al., 2010), and rat anti-Mira (1:100) (Lee et al., 2006c). Secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc and Thermo Fisher Scientific. We used rhodamine phalloidin or Alexa Fluor Plus 405 phallloidin (ThermoFisher Scientific) to visualize cortical actin. Confocal images were acquired on a Leica SP5 scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc) using a 63 x glycerol immersion objective, as z-stacks with 1.51 µm thickness. Images were taken at 1.5 x zoom for whole lobe, or 3/5 x zoom for single neuroblasts/single clonal lineages.

Hybridization chain reaction (HCR) and immunofluorescent staining

mRNA signals in the larval brain were developed by performing in situ HCR v3.087. We modified the protocol of in situ HCR v3.0 to combine immunofluorescent staining of the larval brain. Third instar larval brains were dissected in PBS and fixed in 100 mM PIPES (pH 6.9), 1 mM EGTA, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1 mM MgSO4 containing 4% formaldehyde for 23 min. Fixed brain samples were washed with PBST containing PBS and 0.3% Triton X-100. After removing fix solution, samples were pre-hybridized with hybridization buffer (10% formamide, 5×SSC, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 10% dextran sulfate) at 37 °C for 1 hr. Prehybridized samples were mixed with 5 nM Sp-1 mRNA HCR probe (Molecular Instruments, Los Angeles, CA) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After hybridization, samples were washed with washing buffer (10% formamide, 5×SSC, 0.3% Triton X-100) and then incubated with amplification buffer (5×SSC, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 10% dextran sulfate) at 25 °C for 30 min. During washing period, imager hairpins (Molecular Instruments, Los Angeles, CA) were denatured at 95 °C for 2 mins. Once samples were equilibrated in amplification buffer, samples were mixed with 3 µM of denatured imager hairpins and incubated at 25 °C for overnight. The next day, samples were washed with PBST and then re fixed in 100 mM PIPES (pH = 6.9), 1 mM EGTA, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1 mM MgSO4 containing 4% formaldehyde for 15 min to initiate immunofluorescent staining procedures.

Quantification and statistical analyses

All biological replicates were independently collected and processed. The observers were blind to the genotypes. All brain samples, except those damaged during processing, will be included in data analyses. Only one brain lobe per brain was imaged to ensure measurement biological variability. Cell types were counted by the imager taker based on the presence of expected markers and cell size (NB:>7 µm diameter; type II NB: Dpn+,Ase-; GMC: Pros+,Ase+) for cells that were outside of the optic lobe region (identified by morphology). All statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, and p-values <0.05, <0.005, <0.0005, and <0.00005 are indicated by (*), (**), (***) and (****), respectively in figures. GraphPad Prism was used to generate dot-plots.

For newborn immature INP identification, Dpn protein was used to identify the type II neuroblast and Mira was used to identify the newly born immature INP nucleus. Pixel intensities of the proteins of interest were measured in the nucleus of the type II neuroblast and corresponding newly born immature INP using ImageJ software. The relative pixel intensity of the protein of interest in the immature INP was taken in relation to the pixel intensity in the type II neuroblast. All biological replicates were independently collected and processed.

For smFISH data quantification, brain lobes were stained for DAPI using ProLong Gold antifade mount with DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific). The top 8 most dorsal neuroblasts were selected from individual brain lobes from distinct brains by cell size and morphology. Fluroescent smFISH foci which overlapped with the nuclear DAPI stain were counted if they were larger than 3 µm in diameter in the z-axis direction (persist for more than 2 slices).

scRNA-seq of the type II neuroblast lineage

UAS-dcr2; Wor-gal4, Ase-gal80; UAS-RFP::stinger larval brains (n=50) were dissected 96 hr after larval hatching in ice cold Rinaldini’s solution during a 45 min interval. Dissected brains were transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing 30 µL of Rinaldini’s solution. A total of 10 µL of 20 mg/mL papain, 10 µL of 20 mg/mL type-1 collagenase, and 1 µL of 15 µM ZnCl was added to the tube. Additional Rinaldini’s solution was added to adjust the final volume to be 100 µL. The tube was mixed gently by flicking, and them incubated on a heat block at 37 °C for 1 hr, while covered with aluminum foil. During this incubation, the tube was flicked for mixing every 10 min.