Abstract

Background

Previous studies have demonstrated racial disparities in opioid prescribing in emergency departments and after surgical procedures. Orthopaedic surgeons account for a large proportion of dispensed opioid prescriptions, yet there are few data investigating whether racial or ethnic disparities exist in opioid dispensing after orthopaedic procedures.

Questions/purposes

(1) Are Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or Pacific Islander (PI) patients less likely than non-Hispanic White patients to receive an opioid prescription after an orthopaedic procedure in an academic United States health system? (2) Of the patients who do receive a postoperative opioid prescription, do Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or PI patients receive a lower analgesic dose than non-Hispanic White patients when analyzed by type of procedure performed?

Methods

Between January 2017 and March 2021, 60,782 patients underwent an orthopaedic surgical procedure at one of the six Penn Medicine healthcare system hospitals. Of these patients, we considered patients who had not been prescribed an opioid within 1 year eligible for the study, resulting in 61% (36,854) of patients. A total of 40% (24,106) of patients were excluded because they did not undergo one of the top eight most-common orthopaedic procedures studied or their procedure was not performed by a Penn Medicine faculty member. Missing data consisted of 382 patients who had no race or ethnicity listed in their record or declined to provide a race or ethnicity; these patients were excluded. This left 12,366 patients for analysis. Sixty-five percent (8076) of patients identified as non-Hispanic White, 27% (3289) identified as Black, 3% (372) identified as Hispanic or Latino, 3% (318) identified as Asian or PI, and 3% (311) identified as another race (“other”). Prescription dosages were converted to total morphine milligram equivalents for analysis. Statistical differences in receipt of a postoperative opioid prescription were assessed with multivariate logistic regression models within procedure, adjusted for age, gender, and type of healthcare insurance. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess for differences in the total morphine milligram equivalent dosage of the prescription, stratified by procedure.

Results

Almost all patients (95% [11,770 of 12,366]) received an opioid prescription. After risk adjustment, we found no differences in the odds of Black (odds ratio 0.94 [95% confidence interval 0.78 to 1.15]; p = 0.68), Hispanic or Latino (OR 0.75 [95% CI 0.47 to 1.20]; p = 0.18), Asian or PI (OR 1.00 [95% CI 0.58 to 1.74]; p = 0.96), or other-race patients (OR 1.33 [95% CI 0.72 to 2.47]; p = 0.26) receiving a postoperative opioid prescription compared with non-Hispanic White patients. There were no race or ethnicity differences in the median morphine milligram equivalent dose of postoperative opioid analgesics prescribed (p > 0.1 for all eight procedures) based on procedure.

Conclusion

In this academic health system, we did not find any differences in opioid prescribing after common orthopaedic procedures by patient race or ethnicity. A potential explanation is the use of surgical pathways in our orthopaedic department. Formal standardized opioid prescribing guidelines may reduce variability in opioid prescribing.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Racial disparities in opioid prescribing practices have been present in the United States for decades [12, 16-18]. A 2021 study of Medicare claims data from 310 individual health systems, consisting of more than 2 million person-years, found Black patients received lower opioid prescription doses than White patients did [9]. Most research has examined prescribing rates in the emergency department or in postoperative general surgery and obstetric and gynecologic procedures; little is known about orthopaedic surgery’s contribution to these disparities. A meta-analysis of 14 emergency department studies with more than 11,700 patients found Black and Hispanic patients were 35% and 23%, respectively, less likely to receive opioids for acute pain in the emergency department than non-Hispanic White patients were [7]. This disparity appears to have been stable from 1990 to 2018 [7]. Racial and ethnic inequities in opioid prescribing have also been observed postoperatively for patients who undergo abdominal procedures such as appendectomies, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and colorectal surgery [8, 14]. Ng et al. [10] found White patients were prescribed larger amounts of opioids for postoperative pain control, although there were no racial or ethnic differences in the amount of opioid analgesia that was self-administered by patients. Similarly, Black and Hispanic mothers are less likely to receive opioid epidural analgesia during labor than White mothers are [2, 13].

Orthopaedic surgeons account for a greater proportion of total dispensed opioid prescriptions than either emergency medicine physicians or general surgeons [3], yet there is a paucity of reports on whether racial and ethnic disparities exist in opioid prescription practices after orthopaedic procedures. One study analyzed patients who underwent open reduction and internal fixation to treat a limb fracture and found non-Hispanic White patients consistently received higher doses of opioid analgesics than Black or Hispanic patients during the postoperative inpatient period [11]. This disparity persisted after controlling for age, gender, healthcare insurance, and number of diagnoses. However, this study only examined 250 patients presenting to one medical center between 1990 and 1992 for a single fracture pattern; it is not clear whether this historical study represents current prescribing. Therefore, we sought to determine whether there are racial or ethnic differences in opioid prescribing practices after orthopaedic procedures in a large cohort of patients presenting for multiple conditions, using more contemporary data from across multiple hospitals in an academic health system.

In this study, we asked: (1) Are Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or Pacific Islander (PI) patients less likely than non-Hispanic White patients to receive an opioid prescription after an orthopaedic procedure in an academic United States health system? (2) Of the patients who do receive a postoperative opioid prescription, do Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or PI patients receive a lower analgesic dose than non-Hispanic White patients when analyzed by type of procedure performed?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We retrospectively analyzed prescription data from all orthopaedic procedures performed in the University of Pennsylvania Health System between January 2017 and March 2021. The University of Pennsylvania Health System is an academic health system that includes six hospitals (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Pennsylvania Hospital, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Hospital, and Princeton Medical Center) in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, at the time of this study. We sought to determine whether there were differences in opioid prescribing among patients of different races and ethnicities.

Study Patients

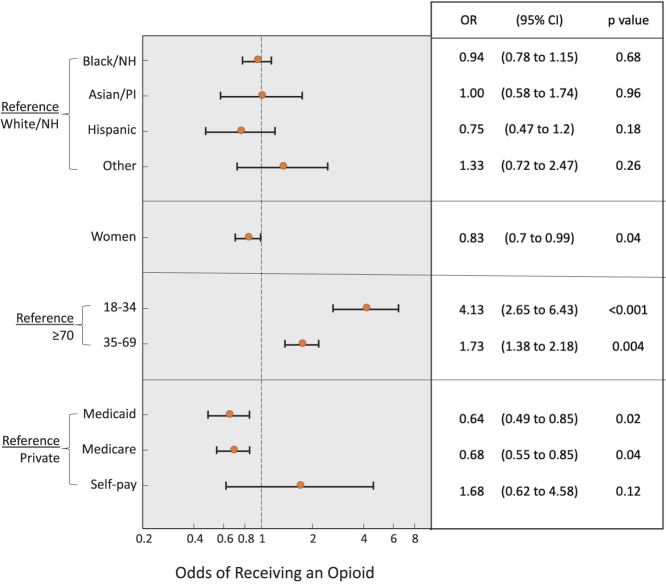

Patients 18 years or older who underwent an orthopaedic surgical procedure between January 2017 and March 2021 were eligible for inclusion. Patients who had an existing diagnosis of an opioid use disorder or patients who were prescribed an opioid within the past year (as evident in the electronic medical record) were excluded. We then restricted inclusion to patients who underwent one of the eight most-common orthopaedic procedures performed during this time period (rotator cuff repair, shoulder arthroscopy, knee arthroplasty, meniscus repair, knee articular cartilage repair, carpal tunnel repair, THA, or TKA) and patients whose surgery was performed by a Penn Medicine faculty member. These eight procedures were chosen because they were all above a cutoff value of 1000 procedures performed during this time period. Some patients underwent more than one orthopaedic procedure during the time period; when that was the case, only the patient’s first procedure was included in the analysis. Additionally, 382 patients did not have race or ethnicity listed in their record or declined to provide a race or ethnicity; these patients were excluded before analysis. This amounted to 12,366 patients and procedures analyzed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

This flowchart shows the patients who were included in and excluded from this study.

Patient race or ethnicity, gender, insurance type, and age were determined from the electronic medical record. Race, ethnicity, and gender identity were self-identified by the patient. Patients are given a dropdown menu for race (options include American Indian, Asian, Black, East Indian, Pacific Islander, White, or unknown) and ethnicity (options include Hispanic or Latino or non-Hispanic or Latino) during the Penn Medicine checkin process. We chose to study both race and ethnicity because of previous studies showing differences in opioid prescribing based on both race and ethnicity [7, 8, 12, 13, 16].

Description of Study Population

A total of 12,366 patients were included in the study (Table 1). Of these patients, 65% (8076) identified as non-Hispanic White, 27% (3289) identified as Black, 3% (372) identified as Hispanic or Latino, 3% (318) identified as Asian or PI, and 3% (311) identified as another race (“other”). Fifty-four percent (6508) of the cohort were women. Each racial group was approximately 50% women with the exception of Black patients, where 63% of the patients were women. Most patients were between 50 and 70 years old. Fifty-five percent (6836) of patients were privately insured, 32% (3907) had Medicare, 12% (1423) had Medicaid, and 2% (199) were self-insured.

Table 1.

Study population

| Parameter | All patients (n = 12,366) | Patients who received opioids (n = 11,770) | % difference | p value | |

| Gender | Women | 54 (6508) | 95 (6150) | 1.4 | < 0.001 |

| Men | 47 (5858) | 96 (5620) | |||

| Age group in years | 18 to 34 | 13 (1657) | 98 (1628) | 7.1 | < 0.001 |

| 35 to 49 | 17 (2146) | 96 (2060) | 4.9 | ||

| 50 to 59 | 25 (3109) | 96 (2975) | 4.6 | ||

| 60 to 69 | 27 (3368) | 95 (3207) | 4.1 | ||

| 70 + | 17 (2086) | 91 (1900) | |||

| Insurance | Private | 55 (6836) | 97 (6604) | < 0.001 | |

| Medicaid | 12 (1423) | 95 (1347) | -1.9 | ||

| Medicare | 32 (3907) | 93 (3623) | -3.9 | ||

| Self-pay | 2 (199) | 98 (195) | 1.4 | ||

| Race | Asian or Pacific Islander | 3 (318) | 96 (304) | 0.2 | 0.40 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 27 (3289) | 95 (3113) | -0.7 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (372) | 95 (352) | -0.7 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 65 (8076) | 95 (7701) | |||

| Other | 3 (311) | 97 (300) | 1.1 | ||

Data are presented as % (n). Race, ethnicity, and gender identity were self-identified by the patient.

Almost all patients (95% [11,770 of 12,366]) received a postoperative opioid prescription after their orthopaedic procedure.

Outcomes

Data on patient demographics (age, gender, and race or ethnicity), procedure performed, prescribing provider, and postoperative prescription data (including name of the medication, quantity, dose, route, and refills) were obtained from the electronic medical record. Because of the small number of patients in some race categories, some categories were combined, and patients were ultimately categorized into five groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or African American, Asian or PI (including East Indian), Hispanic or Latino, and other (American Indian, Native American, or multiracial).

Study Outcomes of Interest

There were two outcomes: whether an opioid was prescribed and the total dose of the opioid prescription. All prescription doses were converted to milligram morphine equivalents (MMEs) for analysis.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (protocol number: 848870).

Statistical Analysis

Standard summary statistics such as frequencies, percentages, and means with standard deviations are used to describe the data. Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to compare differences in opioid prescribing by race or ethnicity, gender, age, insurance, and type of procedure performed. A multivariate logistic regression model was developed to examine the relationship between race or ethnicity and receiving an opioid prescription, adjusting for patient age, gender, and insurance type. Insurance type was included as a confounder because some patients from racial minority groups (including Hispanic, Black, and American Indian) are more likely to be uninsured than their White counterparts [1]. For this analysis, data are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. As per Centers for Disease Control convention, one oxycodone 5-mg tablet was set as equal to 7.5 MMEs. To examine MME dose differences by race or ethnicity stratified by procedure, Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed because of non-normal distribution of MME dosing. For these analyses, data are presented as the median MME with interquartile range. Patients who did not receive a postoperative opioid prescription were not included in the MME analysis. All analyses were performed by a statistician (FSS) using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute). We considered p values < 0.05 to be significant.

Results

Are Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or PI Patients Less Likely to Receive a Postoperative Opioid Prescription Than Non-Hispanic White Patients?

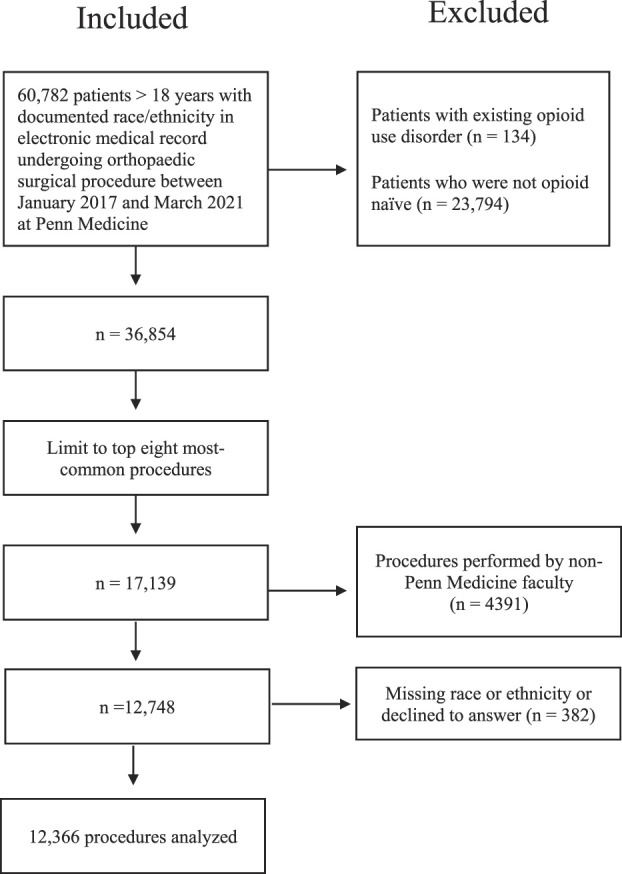

After adjusting for gender, age, and insurance type, we found no differences in the odds of Black (odds ratio 0.94 [95% CI 0.78 to 1.15]; p = 0.68), Hispanic or Latino (OR 0.75 [95% CI 0.47 to 1.2]; p = 0.18), Asian or PI (OR 1.00 [95% CI 0.58 to 1.74]; p = 0.96), or other-race patients (OR 1.33 [95% CI 0.72 to 2.47]; p = 0.26) receiving a postoperative opioid prescription compared with non-Hispanic White patients (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This figure represent the odds a patient will receive a postoperative opioid prescription. Non-Hispanic White race served as the referent for the odds ratio pertaining to race, men served as the referent pertaining to gender, age ≥ 70 years served as the referent pertaining to age, and private insurance served as the referent pertaining to insurance type. When assessing the odds ratio for receiving an opioid by race, we adjusted for the demographic variables of gender, age, and insurance type. NH = non-Hispanic; PI = Pacific Islander.

Women had lower odds of receiving an opioid prescription than men did (OR 0.83 [95% CI 0.70 to 0.99]; p = 0.04). Patients aged 18 to 34 years had higher odds of receiving an opioid prescription than those aged 70 years and older (OR 4.13 [95% CI 2.65 to 6.43]; p < 0.001), as did patients aged 35 to 69 years (OR 1.73 [95% CI 1.38 to 2.18]; p = 0.004). We found no differences in the odds of patients with private insurance receiving an opioid prescription compared with patients who self-paid (OR 1.68 [95% CI 0.62 to 4.58]; p = 0.12). Patients with Medicaid (OR 0.64 [95% CI 0.49 to 0.85]; p = 0.02) and Medicare insurance (OR 0.68 [95% CI 0.55 to 0.85]; p = 0.04) had lower odds of receiving an opioid than patients with private insurance did (Fig. 2).

Of the Patients Who Do Receive a Postoperative Opioid Prescription, Do Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian or PI Patients Receive a Lower Analgesic Dose Than Non-Hispanic White Patients?

When stratified by procedure performed, there were no racial or ethnic differences in the postoperative analgesic dose prescribed. The median MME dose for rotator cuff repair, shoulder arthroscopy, knee arthroplasty, THA, and TKA was 225 MMEs for each racial and ethnic group. The median MME for meniscus repair was 150 MMEs for each racial and ethnic group besides White, for which it was 142.5 MMEs (p = 0.47). The median MME for knee articular cartilage repair was 150 MMEs for White, Black, and other-race patients, and 225 MMEs for Asian and Hispanic patients (p = 0.28). The median MME for carpal tunnel repair was 67.5 MMEs for each racial and ethnic group besides other-race patients, for which it was 50 MMEs (p = 0.46) (Supplemental Table 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B34).

Discussion

Racial and ethnic disparities in opioid prescriptions have been reported in different American healthcare settings, including emergency medicine, general surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology [2, 7-14, 16-18]. Non-White patients are less likely to receive opioids for acute pain and receive lower doses of opioids for postoperative pain control. There are limited data exploring whether there are racial and ethnic differences in postoperative opioid prescriptions in orthopaedic surgery, despite the common and routine use of opioids after orthopaedic procedures [3]. We sought to fill this knowledge gap by examining the opioid prescribing practices of an orthopaedic surgery department in a large mid-Atlantic academic health system. In this study of 12,366 patients undergoing eight common elective orthopaedic procedures between 2017 and 2021, we did not find differences in postoperative opioid prescribing according to patient race or ethnicity. Specifically, neither the percentage of patients receiving a postoperative opioid prescription nor the total dose of the prescription differed by race or ethnicity.

Limitations

First, the study was conducted using data from a large mid-Atlantic urban and suburban academic health system and may not be generalizable to all practices. There is geographic variability in patients from a tristate area, and the patient population represents individuals from urban, suburban, and rural areas. Second, we only included patients who underwent one of the top eight most-commonly performed orthopaedic procedures at Penn Medicine, which often have standard postoperative pathways; as such, patients undergoing trauma surgery and more-complex surgical procedures were not analyzed. It is possible racial differences in opioid prescription exists in those cases but was not captured in this study. Third, a department-wide opioid prescribing guideline was introduced to the Penn Medicine orthopaedic faculty (including attendings, residents, and advanced practice providers) in November 2020. This document provides recommended quantities of postoperative opioid analgesics needed for multiple different orthopaedic procedures. The document is available to the orthopaedic department but not mandated for use. The distribution of standard opioid prescribing guidelines might have changed the prescribing habits of orthopaedic providers. However, 90% of our study period occurred before the document was introduced to the department, and the document only included recommendations for three of the eight procedures included in our analysis (hip arthroscopy, knee arthroplasty, and carpal tunnel repair), so it is unlikely the guidelines caused any substantive changes in our results.

Fourth, the race and ethnic categories of “Asian” and “Hispanic or Latino” may be considered overly broad when examining access to care in the United States. The United States Census Bureau lists more than 20 different groups that may be defined as Hispanic or Latino, including people originating from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, Spain, and other Central and South American countries [19]. Similarly, the United States Census Bureau also considers more than 20 different groups to fall under the umbrella of Asian [20]. It would be wrong to assume individuals from so many different groups experience access to care in the same way. However, our data were collected from the electronic medical record, which uses these broader categories.

Lastly, we were unable to study other factors that may be relevant. These include patient income or access to resources, the race of the prescribing provider, patient preference for opioid analgesia, and intraoperative or postoperative complications. The large population in this study also makes it unlikely that rare events would substantially impact the study findings. We would have liked to examine the relationship between Area Deprivation Index and postoperative opioid prescription based on the results of Joynt et al. [5], who found opioids were prescribed less frequently to patients residing in low-income areas than to patients residing in more-affluent areas. Unfortunately, our dataset did not contain location data. Nevertheless, Joynt et al. [5] also found Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive an opioid prescription than their White counterparts even after adjusting for Area Deprivation Index, implying that seeking differences by race alone is still valuable.

Discussion of Key Findings

When we compared patients of varied races and ethnicities, we found no differences in the odds that a patient would receive an opioid prescription after orthopaedic surgery in a large, urban healthcare system. We also found no differences in median opioid dosing across the population studied. These findings were surprising to us based on previous research showing racial differences in opioid prescribing patterns [2, 7, 8, 10-14, 16-18]. It may be that this particular academic orthopaedic group is an outlier. Yet, we suspect the use of surgical pathways and routinization of common orthopaedic procedures has a protective effect on differences in postoperative opioid prescribing. This study was conducted using data from an academic practice, where most surgeons provide standard surgical pathways to their resident and advanced-practice provider teams, which included recommended doses for postoperative opioids based on the procedure performed. These types of surgical pathways for common procedures existed before the implementation of the standardized opioid prescribing guidelines described in the Limitations subsection of this article. Our null finding—the absence of a difference in prescribing patterns—may be because of these types of algorithms. The use of formal standardized postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines has been shown to reduce racial discrepancies in opioid prescribing in a wide range of surgical specialties, as well as decrease the amount of opioids given [4, 6]. Clinicians or hospital administrators who wish to implement fairer healthcare policy to reduce differences in opioid prescription patterns may wish to explore interspecialty prescribing patterns and the existence of prescribing pathways, as well as consider the use of standardized opioid prescribing guidelines for all types of surgical subspecialties. Future matched-cohort studies observing racial and ethnic differences in opioid prescribing before and after implementation of a standardized opioid prescribing guideline could further expand our knowledge of their posited benefits.

The question remains as to why prescribing differences have been observed in other healthcare settings but not after orthopaedic surgeries at our academic healthcare center. Routine pathways might not exist in the emergency department because of the acute and variable nature of each patient’s presentation, and this may explain the different findings. However, other procedures that are considered common (for example, cholecystectomies, appendectomies, and hysterectomies) have also been shown to have racial differences in postoperative opioid prescribing. We have hypotheses but not answers for this difference. It may be that those procedures are performed on an urgent or emergent basis, and therefore less routinized in postoperative care than elective orthopaedic procedures are. The implementation of standard opioid prescribing guidelines for all types of specialties and surgeries would likely help in reducing racial differences in opioid prescribing in these areas, if still present. In spaces where standardized prescribing guidelines are more difficult, such as the emergency department, using the vast amount of data and computing power of the electronic medical record may be an alternative option. Because the electronic medical record contains data on patient demographics and prescription information, a program could be created to alert clinicians if opioid prescriptions differ substantially between racial and ethnic groups.

Of note, we found differences in the odds of receiving an opioid prescription based on gender, insurance type, and age. The differences found for gender and insurance type were small and likely not clinically valuable. Older patients were less likely to receive opioids than younger patients, which is on par with current guidelines of opioid stewardship [15].

Conclusion

In this study, we found no differences by patient race or ethnicity in the likelihood of receiving an opioid prescription after undergoing an orthopaedic procedure at a mid-Atlantic academic health system. Of the patients who received an opioid prescription, there were no differences in the median dose of opioids prescribed. The use of surgical pathways that include guidelines for postoperative opioid prescriptions might reduce the risk of racial and ethnic differences in opioid prescribing. Implementing formal standardized opioid prescribing guidelines in all medical and surgical specialties may be a mechanism to mitigate differences in opioid prescribing patterns.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aria Xiong MS and Erik Hossain BS for their assistance with data extraction.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (MKD) has received, during the study period, funding from a grant from the FDA (HHSF223201810209C) and from the Abramson Family Foundation.

Each author certifies that there are no funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article related to the author or any immediate family members.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol#: 848870).

This work was performed at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Contributor Information

Lucy R. O’Sullivan, Email: CRimnac@clinorthop.org, clare.rimnac@case.edu.

Frances S. Shofer, Email: shofer@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

M. Kit Delgado, Email: mucio.delgado@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Anish K. Agarwal, Email: anish.agarwal@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Artiga S, Hill L, Damico A. Health coverage by race and ethnicity, 2010-2021. Available at: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- 2.Glance LG, Wissler R., Glantz C, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Dick AW. Racial differences in the use of epidural analgesia for labor. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy GP, Zhang K. Opioid prescribing by specialty and volume in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:e153-e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herb JN, Williams BM, Chen KA, et al. The impact of standard postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines on racial differences in opioid prescribing: a retrospective review. Surgery. 2021;170:180-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joynt M, Train MK, Robbins BW, Halterman JS, Caiola E, Fortuna RJ. The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status and race on the prescribing of opioids in emergency departments throughout the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1604-1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaafarani HMA, Eid AI, Antonelli DM, et al. Description and impact of a comprehensive multispecialty multidisciplinary intervention to decrease opioid prescribing in surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;270:452-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:1770-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald DD. Gender and ethnic stereotyping and narcotic analgesic administration. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morden NE, Chyn D, Wood A, Meara E. Racial inequality in prescription opioid receipt—role of individual health systems. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:342-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng B, Dimsdale JE, Rollnik JD, Shapiro H. The effect of ethnicity on prescriptions for patient-controlled analgesia for post-operative pain. Pain. 1996;66:9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng B, Dimsdale JE, Shragg GP, Deutsch R. Ethnic differences in analgesic consumption for postoperative pain. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299:70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rust G, Nembhard WN, Nichols M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the provision of epidural analgesia to Georgia Medicaid beneficiaries during labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:456-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salamonson Y, Everett B. Demographic disparities in the prescription of patient-controlled analgesia for postoperative pain. Acute Pain. 2005;7:21-26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieber FE, Barnett SR. Preventing postoperative complications in the elderly. Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;29:83-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhal A, Tien Y-Y, Hsia RY. Racial-ethnic disparities in opioid prescriptions at emergency department visits for conditions commonly associated with prescription drug abuse. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department analgesic prescription. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:2067-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537-1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic or Latino origin. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/note/US/RHI725221. Accessed October 9, 2022.

- 20.U.S. Census Bureau. 20.6 million people in the U.S. identify as Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/05/aanhpi-population-diverse-geographically-dispersed.html. Accessed October 9, 2022.