Abstract

Sea cucumber is a morphologically diverse and ecologically important clade of echinoderms. The sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus is the most economically valuable species of sea cucumber. The initial assembly of the A. japonicus genome was released in 2017. However, this genome assembly is fragmented and lacks relative position information of genes on chromosomes. In this study, we produced a high-quality chromosome-level genome of A. japonicus using Pacbio HiFi long-reads and Hi-C sequencing data. The assembled A. japonicus genome spanned 671.60 Mb with a contig N50 size of 17.20 Mb and scaffold N50 size of 29.65 Mb. A total of 99.9% of the assembly was anchored to 23 chromosomes. In total, 19,828 genes were annotated, and 97.2% of BUSCO genes were fully represented. This high-quality genome of A. japonicus will not only aid in the development of sustainable aquaculture practices, but also lay a foundation for a deeper understanding of their genetic makeup, evolutionary history, and ecological adaptation.

Subject terms: Genome, Genomics

Background & Summary

The sea cucumber belongs to Echinodermata, which occupy an important phylogenetic position together with their sister phylum, Hemichordata. Evolutionary studies of sea cucumber are crucial for understanding the origin of chordates1. Sea cucumbers have evolved special behaviors, including super regenerative capacity, aestivation, and anatomy, among others, to adapt to various oceanic environments. This adaptation has taken place over a long evolutionary history, which can be traced back to the early Cambrian era2. Sea cucumbers play crucial roles in maintaining the health of the ocean floor by consuming dead plant and animal matter, which helps to keep the sediment in a balanced state3. In addition, sea cucumbers are important economic aquaculture species and have been deemed as one of the most valuable functional foods in the sea due to their nutritional and pharmacological properties4,5. Among approximately 60 species with exploitation value, Apostichopus japonicus is the most economically important species6. In China alone, around 200,000 tons of adult A. japonicus are produced each year, with an estimated whole industrial chain value of about 15 billion dollars (Sea cucumber Industry Branch of China Fisheries Association, 2010–2022).

For the reasons listed above, A. japonicus is one of the most studied echinoderms, and a total of 1,358 research papers on A. japonicus were published between 2000 to 20217. Such research occurs in fisheries8,9, immunology10,11, food science and biological medicine4,5, ecological function3, as well as biochemistry and molecular biology12–14. With the deepening of research requirements and development of biological technologies, studies of the mechanisms on phenotype formation, physiological responses, and behavioral regulation is rapidly developing. Hence, the genetic resources of A. japonicus have been exploited, including the coding and noncoding RNA transcriptome15–17, proteome18, epigenome19, genetic linkage map20,21 and genome1,22. Among them, the genome is the most basic data that is essential for most multi-omics analyses.

In 2017, Zhang et al. constructed the A. japonicus genome with the assembly of 805 Mb (contig N50 of 190 Kb and scaffold N50 of 486 Kb)22 (Table 1). A total of 30,350 protein-coding genes were annotated in that genome version22 (Table 1). In 2018, Li et al. published 952 Mb (contig N50 of 45 Kb and scaffold N50 of 196 Kb) of the A. japonicus genome with 29,451 protein-coding genes1 (Table 1). In 2022, Wang et al. constructed a chromosome-level A. japonicus genome using Hi-C technology based on the 2017 genome assembly version23. However, the existing genome versions are far behind the growing demand of in-depth study on A. japonicus biology. Genomes with a low contig N50 are generally highly fragmented, resulting in the poor annotation of protein-coding genes and non-coding sequences24. For example, the sea cucumber breeding industry is currently primarily focused on traditional breeding methods, with molecular marker-assisted breeding playing a supporting role. A. japonicus breeding is in the transition from Breeding 2.0 (Statistical and experimental design to improve selection effort) to Breeding 3.0 (Integration of genetic and genomic data)25. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and genomic selection (GS) are required to identify genes related to economic traits and accurately evaluate them in A. japonicus breeding programs. Therefore, genomes with long contig N50s and long continuity are essential. Moreover, the annotation of functional genes and regulatory elements plays important roles in understanding evolutionary mechanisms and genetic regulation, which depend on the high quality of genome.

Table 1.

Comparison of A. japonicus genome assemblies in 2017, 2018 and 2023.

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing instrument | Illumina + PacBio (CLR) | Illumina + PacBio (CLR) | Illumina + Pacbio (CCS) |

| # Reads | 128,784,478 | — | 10,588,443 |

| # Bases (Gbp) | 260 (Illumina) + 64 (Pacbio) | 349 (Illumina) + 23 (Pacbio) | 56.54 (Illumina) + 43.22 (Pacbio) |

| Coverage | 295 × (Illumina) + 73 × (Pacbio) | 346 × (Illumina) + 24 × (Pacbio) | 84 × (Illumina) + 64 × (Pacbio) |

| Hi-C(Gbp) | — | — | 3.18 |

| # Chromosomes | — | 22 | 23 |

| Genome size (Mbp) | 804.9 | 952 | 671.6 |

| # Contigs | 4,741 | 21,303 | 198 |

| Contig N50 (Mbp) | 0.190 | 0.045 | 17.20 |

| # Scaffolds | 3,281 | 7,286 | 34 |

| Scaffold N50 (Mbp) | 0.486 | 0.196 | 29.65 |

| Repeat rate (%) | 27.2 | 26.6 | 47.33 |

| GC content (%) | 36.75 | 37.37 | 38.56 |

| # Genes | 30,350 | 29,451 | 19,828 |

| miRNAs | 137 | — | 1,066 |

| tRNAs | 1,127 | — | 4,963 |

| rRNAs | 75 | — | 3,379 |

| snRNAs | 223 | — | 1,088 |

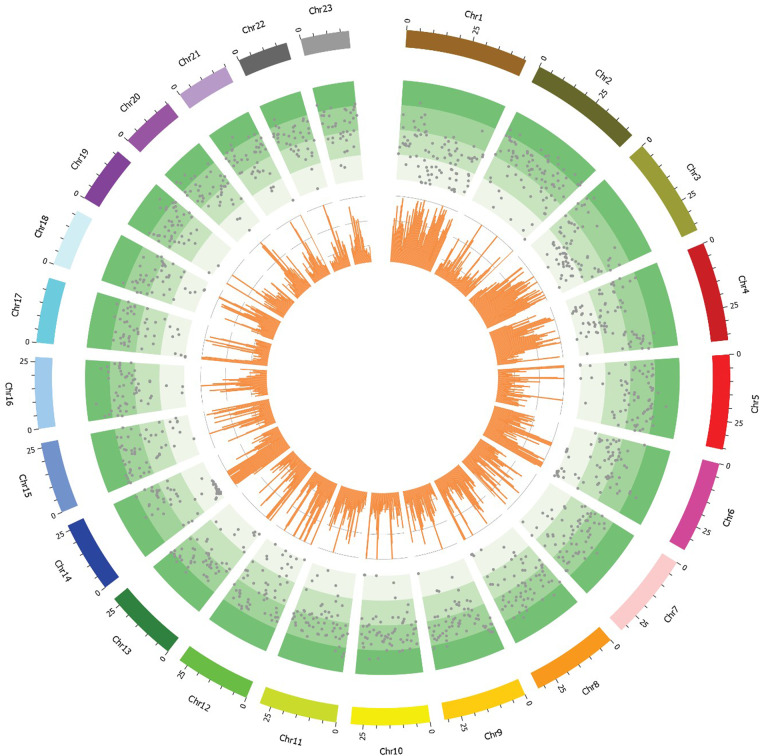

We applied multiple sequencing technologies, generating 56.54 Gb of Illumina data, 43.22 Gb of PacBio data, and 3.18 Gb of HiC data, to reconstruct the chromosome-level A. japonicus genome (Fig. 1), which is the first known chromosome-level genome of sea cucumber (Table 1). The final assembly was 671.60 Mb in total length with a contig N50 length of 17.20 Mb and scaffold N50 length of 29.65 Mb (Table 1). The assembly quality was much better than those of the previous genome versions. The genome developed herein will be an excellent tool to better investigate the mechanisms that drive evolution and biodiversity23. By analyzing their genetic basis, researchers can identify the compounds responsible for these benefits and develop new treatments for human diseases4. Moreover, scientists can better understand the genetic basis of their responses to environmental stressors by studying their genomes, and develop new tools for monitoring and conserving the ocean’s resources26. As an important aquaculture species, the accurate genetic analysis of economic traits can help to improve the genetic stability of target traits and the success rate of genetic improvement operations20. Overall, constructing a high-quality genome for sea cucumbers is a crucial step in advancing the understanding of these unique animals and their importance to the health of the ocean and to human well-being.

Fig. 1.

A circos plot of 23 chromosomes of A. japonicus genome. The tracks from inside to outside are: bar plot for gene density profile, the distributions of transposable element and 23 chromosomes.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

The longitudinal muscle of a female A. japonicus was collected in Rushan, Shandong Province, China, in 2021. The sample was washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. After DNA extraction, a short fragmented library was prepared with an insert size of 350 bp and sequenced using the Illumina Platform to generate 150-bp paired-end reads. For HiFi read generation, high-molecular-weight (HMW) gDNA was sheared to approximately 15 Kb before preparing a PacBio HiFi library. The genomic library was sequenced in CCS mode on the PacBio Sequel II system at Novogene (Beijing, China). After trimming the low-quality reads and adaptor sequences from the raw data, 56.54 Gb of Illumina data and 43.22 Gb of PacBio data with a mean read length of 14.7 Kb were obtained, resulting in 83.58-fold and 63.89-fold coverage of the A. japonicus genome respectively (Table 2). Such coverage was sufficient for haplotype-resolved assembly.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of sequencing reads from Illumina and PacBio.

| libraries | Total data (G) | Read length (bp) | Sequence coverage (X) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina reads | 56.54 | 150 | 83.58 |

| PacBio reads | 43.22 | 14,729 (mean) | 63.89 |

| Total | 99.76 | — | 147.47 |

Genome assembly

The genome was assembled using the default parameters of Hifiasm (v0.15.4-r343)27. Hifiasm calculates from the uncollapsed genome, allowing it to preserve haplotype information as much as possible. The HiFi long reads were provided to Hifiasm to generate the monoploid and a pair of haplotype-resolved assembly contig graphs. We assembled 178 contigs with a total length of 671.63 Mb. The maximum contig size and N50 were 38.08 and 17.20 Mb (Table 3), respectively.

Table 3.

Assembly statistics at the contig level.

| Type | Contig (bp) |

|---|---|

| Total Number | 178 |

| Total Length | 671,627,515 |

| Average Length | 3,773,188 |

| Max Length | 38,087,046 |

| Min Length | 18,165 |

| N50 Length | 17,200,168 |

| N50 Number | 14 |

| N90 Length | 9,296,432 |

| N90 Number | 35 |

Hi-C library preparation, sequencing, and chromosome anchoring

A Hi-C library was prepared following the Hi-C library protocol28. After grinding with liquid nitrogen, fresh muscle was cross-linked using 4% formaldehyde solution at room temperature in a vacuum for 30 min. The fixation was terminated using 2.5 M glycine. Following cell lysis, cross-linked DNA was digested using the four-cutter restriction enzyme MboI. The DNA ends were subsequently labeled with biotin-14-dCTP and subjected to blunt-end ligation of the cross-linked fragments. DNA was extracted and purified using the phenol-chloroform extraction method. Sonication was employed to generate fragments ranging from 200 to 600 base pairs, and the ends of these fragments were repaired using a combination of T4 DNA polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and Klenow DNA polymerase. Streptavidin C1 magnetic beads were utilized for the specific enrichment of biotin-labeled Hi-C samples29,30. Following the addition of A-tails to the fragment ends and ligation with Illumina paired-end (PE) sequencing adapters, Hi-C sequencing libraries were subjected to PCR amplification (12–14 cycles) and subsequently sequenced on an Illumina PE150 platform. The raw sequence data were filtered to obtain a total of 73.50 Gb of clean data, with Q20 = 96.28% and Q30 = 91.25% (Table 4), which was used to assist chromosome assembly.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of sequencing data from Hi-C.

| Type | Data |

|---|---|

| Raw paired reads | 244,997,475 |

| Raw Base(bp) | 73,499,242,500 |

| Clean Base(bp) | 73,002,860,400 |

| Effective Rate(%) | 99.28 |

| Q20(%) | 96.28 |

| Q30(%) | 91.25 |

| GC Content(%) | 38.56 |

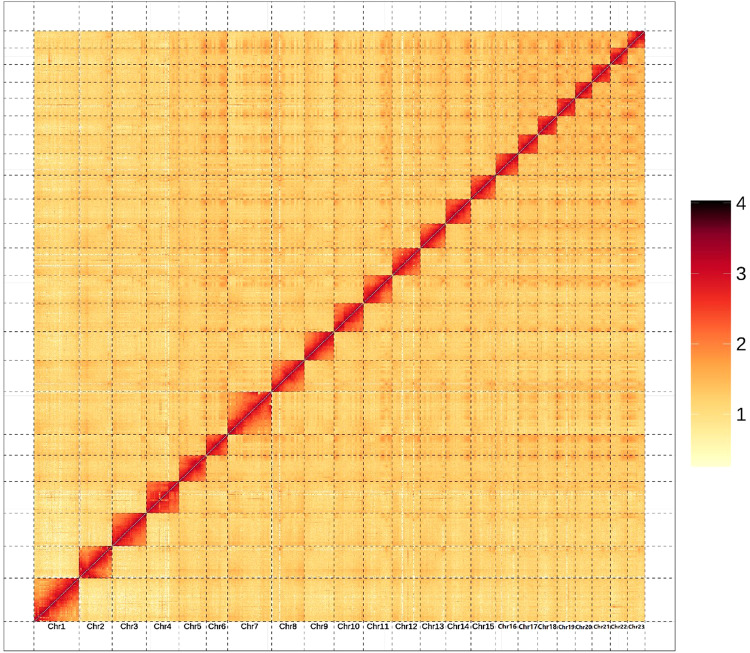

HiCUP (v0.8.1) was used to process the Hi-C data31. The clean Hi-C data was assembled using the ALLHiC pipeline, which contained a total of five steps: pruning, partitioning, rescuing, optimizing and building32,33. Finally, 99.94% of the initial assembled sequences were anchored to 23 pseudo-chromosomes (Fig. 2) with lengths ranging from 18.21 to 46.02 Mb. The total length of the genome assembly was 671.63 Mb, with 34 scaffolds and a scaffold N50 of 29.65 Mb (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Genome-wide Hi-C heatmap of Apostichopus japonicus.

Table 5.

Assembly statistics for Hi-C.

| Type | Contig length | Scaffold length | Contig number | Scaffold number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 671,627,515 | 671,643,915 | 198 | 34 |

| N50 | 15,848,779 | 29,647,521 | 15 | 10 |

| N90 | 8,359,816 | 20,397,903 | 38 | 20 |

| Place | — | 671,222,061 | — | 23 |

| Unplace | — | 421,854 | — | 11 |

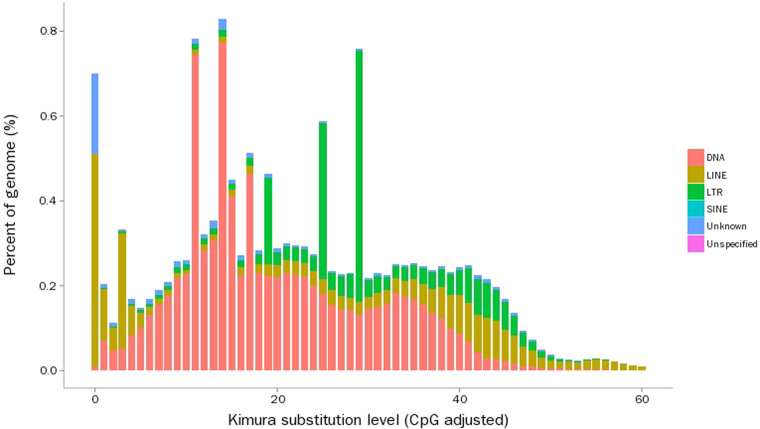

Genomic repeat annotation and ncRNA annotation

Repeat sequences of the A. japonicus genome were identified by homology-based and de novo strategies34. First, we integrated the repetitive sequence database predicted by Denovo with the homologous repetitive sequence database, Repbase35. Then, we used RepeatScout (v1.0.5)34, RepeatModeler (v2.0.1)36, Piler (v1.0)37 and LTR-FINDER (v1.0.6)38 to identify transposable element (TE) families. Repeatmasker (v4.1.0)36, RepeatProteinMask (v4.1.0) and TRF (v4.0.9)39 were used to identify and classify different repetitive elements by aligning the A. japonicus genome sequences against the integrated database. After removing the redundancy results obtained using the above three methods, the total length of the repeat sequences accounted for 47.33% of the A. japonicus genome. In addition, the Kimura divergence value of TE was calculated using calcDivergenceFromalign.pl40. TE landscapes were drawn using createRepeatLandscape.pl41 (Fig. 3). Among the repeat elements, short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) accounted for 0.02% of the genome and long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) accounted for 2.94% of the genome. Long terminal repeats (LTRs) and DNA elements accounted for 27.03% and 3.74% of the genome, respectively (Table 6).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of divergence rates for TEs in the A. japonicus genome.

Table 6.

Classification of repetitive sequences and ncRNAs in the A. japonicus genome.

| Type | Denovo + Repbase | TE Proteins | Combined TEs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length(bp) | % in Genome | Length(bp) | % in Genome | Length(bp) | % in Genome | ||

| DNA | 24,861,559 | 3.70 | 517,042 | 0.08 | 25,141,601 | 3.74 | |

| LINE | 16,671,289 | 2.48 | 5,258,345 | 0.78 | 19,744,382 | 2.94 | |

| SINE | 159,644 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 159,644 | 0.02 | |

| LTR | 181,153,677 | 26.97 | 4,991,945 | 0.74 | 181,560,277 | 27.03 | |

| Unknown | 78,711,126 | 11.72 | 0 | 0 | 78,711,126 | 11.72 | |

| Total | 287,263,851 | 42.77 | 10,766,642 | 1.60 | 288,599,322 | 42.97 | |

| Type | Copy number | Total length(bp) | % of genome | ||||

| miRNA | 1,066 | 117,207 | 0.017451 | ||||

| tRNA | 4,963 | 367,482 | 0.054714 | ||||

| rRNA | rRNA | 3,379 | 421,316 | 0.062729 | |||

| 18 S | 558 | 130,190 | 0.019384 | ||||

| 28 S | 703 | 168,303 | 0.025058 | ||||

| 5.8 S | 86 | 7,311 | 0.001089 | ||||

| 5 S | 2,032 | 115,512 | 0.017198 | ||||

| snRNA | snRNA | 1,088 | 142,445 | 0.021208 | |||

| CD-box | 70 | 10,703 | 0.001594 | ||||

| HACA-box | 12 | 2,126 | 0.000317 | ||||

| splicing | 996 | 127,438 | 0.018974 | ||||

| scaRNA | 4 | 661 | 0.000098 | ||||

| Unknown | 6 | 1,517 | 0.00022 | ||||

For the annotation of noncoding RNA (ncRNA), tRNAScan (v1.4)42 and blast (v2.2.26)43 were used for tRNA and rRNA prediction, respectively. Other noncoding RNAs, including miRNA and snRNA were detected by alignment to the Rfam database44 using INFERNAL (v1.0)45. Four types of noncoding RNAs, including 1,066 miRNAs, 4,963 tRNAs, 3,379 rRNAs, and 1,088 snRNAs, were identified from the A. japonicus genome (Table 6).

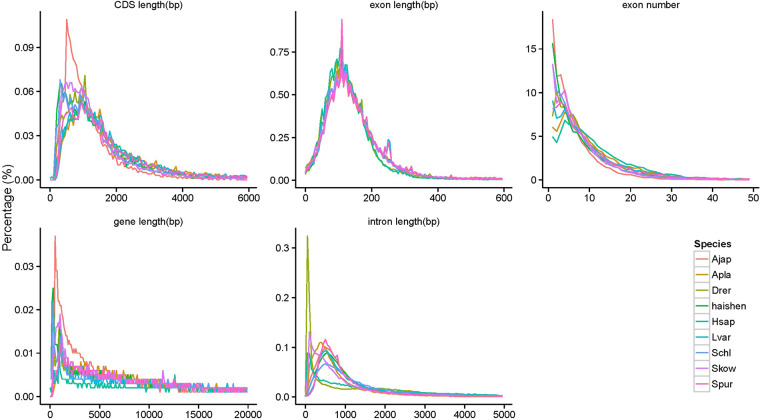

Protein-coding gene prediction and annotation

Gene structures were predicted using three basic strategies: de novo, homology-based, and transcriptome sequencing-based prediction. Based on the genome sequence, we used Augustus (v3.2.3)46, GlimmerHMM (v3.0.4)47, SNAP (v2013.11.29)48, Geneid (v1.4)49 and Genscan (v1.0)50 for ab initio gene prediction. For homology-based gene prediction, the protein sequences of L. variegatus51, S. purpuratus52, A. planci53, H. sapiens54, D. rerio55, S. chloronotus56 and S. kowalevskii57 were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Blast (v2.2.26)43 and Genewise (v2.4.1)58 were used to align the protein sequences of A. japonicus to the seven other species for homology-based gene prediction. A total of 10,707, 11,249, 9,982, 7,184, 7,374, 15,566 and 11,377 genes were identified for L. variegatus, S. purpuratus, A. planci, H. sapiens, D. rerio, S. chloronotus and S. kowalevskii, respectively (Table 7). We also compared the gene, CDS, and exon and intron lengths to those of the seven other species (Fig. 4). For A. japonicus, the average lengths of the transcript, exons, and introns were 7,736.67, 193.65, and 1,286.06 bp, respectively.

Table 7.

Statistical analyses of the gene structure annotation of the A. japonicus genome.

| Gene set | Number | Average transcript length(bp) | Average CDS length(bp) | Average exon length(bp) | Average intron length(bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo | Augustus | 19,684 | 12,358.41 | 1,546.20 | 7.79 | 1,593.00 |

| GlimmerHMM | 44,287 | 13,553.26 | 795.90 | 4.88 | 3,290.80 | |

| SNAP | 26,032 | 25,835.92 | 1,012.99 | 6.55 | 4,473.70 | |

| Geneid | 17,957 | 21,083.14 | 1,702.56 | 7.69 | 2,896.45 | |

| Genscan | 18,774 | 23,593.41 | 1,770.98 | 8.75 | 2,816.45 | |

| Homolog | Skow | 11,377 | 6,900.30 | 6,900.30 | 4.78 | 1,566.05 |

| Ajap | 19,702 | 7,316.82 | 7,316.82 | 5.86 | 1,277.02 | |

| Hsap | 7,184 | 8,555.73 | 8,555.73 | 5.82 | 1,549.13 | |

| Apla | 9,982 | 10,725.65 | 10,725.65 | 6.86 | 1,600.22 | |

| Spur | 11,249 | 9,002.69 | 9,002.69 | 6.22 | 1,486.67 | |

| Schl | 15,566 | 11,840.35 | 11,840.35 | 7.31 | 1,645.92 | |

| Lvar | 10,707 | 9,336.09 | 9,336.09 | 6.48 | 1,467.80 | |

| Drer | 7,374 | 8,030.81 | 8,030.81 | 5.49 | 1,547.84 | |

| RNAseq | PASA | 18,773 | 17,353.65 | 17,353.65 | 7.13 | 2,615.21 |

| Transcripts | 27,221 | 33,433.24 | 33,433.24 | 8.85 | 3,775.72 | |

| EVM | 19,961 | 14,204.95 | 14,204.95 | 7.96 | 1,817.50 | |

| Pasa-update* | 19,850 | 14,577.36 | 14,577.36 | 8.05 | 1,844.83 | |

| Final set* | 19,827 | 14,590.03 | 14,590.03 | 8.06 | 1,844.91 | |

| Final set update* | 19,828 | 14,589.57 | 14,589.57 | 8.06 | 1,844.92 | |

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of the genomic elements of closely related species.

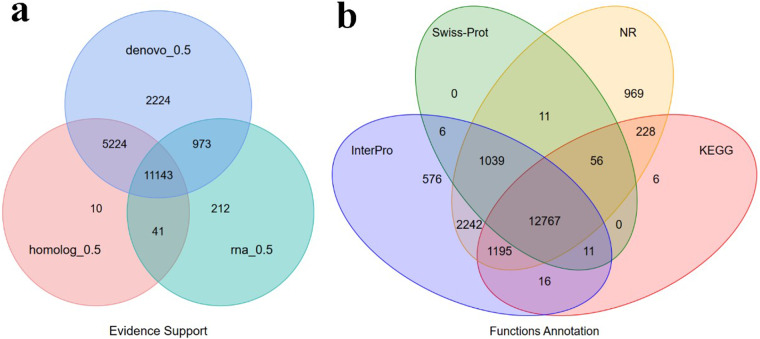

The clean RNA-seq data underwent two types of assembly methods. For transcript assembly, we relied on the reference genome, while de novo assembly was carried out using Trinity (v2.11.0)59. Open reading frames (ORFs) were detected using PASA (v2.1.0)60. Based on the predictions, we used EvidenceModeler(v1.1.1)61 to integrate the gene sets predicted using different strategies into a non-redundant and complete gene set of 19,828 protein-coding genes (Table 7 & Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Gene prediction and functional annotation of the A. japonicus genome. (a) Venn diagram of the gene set prediction. (b) Venn diagram of functional annotation based on different databases.

To perform functional annotation of protein-coding genes, Blastp (v2.2.26)62 and Diamond (v0.8.22)63 were used to align protein-coding genes to the SwissProt64, NCBI Non-redundant protein(NR) (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/nrdb/), KEGG65, InterPro66, GO Ontology (GO)67 and Pfam68 protein databases using an E-value threshold of 1E-5. The protein domains and motifs were annotated using InterProScan (v5.52-86.0)69. Finally, 19,122 (96.40%) of the 19828 predicted genes were annotated by at least one database (Table 8). Of the functional proteins, 12,767 (64.39%) were supported by all four databases (Fig. 5b).

Table 8.

Statistical analysis of the functional gene annotations of the A. japonicus genome.

| Database | Number | Percent(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 19,828 | — |

| Swissprot | 13,890 | 70.10 |

| Nr | 18,507 | 93.30 |

| KEGG | 14,279 | 72.00 |

| InterPro | 17,852 | 90.00 |

| GO | 10,781 | 54.40 |

| Pfam | 13,332 | 67.20 |

| Annotated | 19,122 | 96.40 |

| Unannotated | 706 | 3.60 |

Data Records

The genomic Illumina sequencing data were deposited in the SRA at NCBI SRR2252357870.

The genomic PacBio sequencing data were deposited in the SRA at NCBI SRR2279926171, SRR2364010672-SRR2364010773.

The transcriptomic sequencing data were deposited in the SRA at NCBI SRR1705608474.

The Hi-C sequencing data were deposited in the SRA at NCBI SRR23362389- SRR2336239275–78.

The final chromosome assembly and genome annotation files are available in Figshare79.

Technical Validation

Evaluation of the genome assembly and annotation

We evaluated the genome assembly quality through the following measures: (i) The BUSCO (V4.1.2)80 evaluation was performed using a single-copy orthologous gene library, combined with software tools such as tblastn, augustus, and hmmer, to assess the assembled genome. The result showed that 97.2% of gene orthologs were detected in A. japonicus. Among them, 96.7% achieved complete scores, while 0.5% obtained fragment scores. This indicates a relatively comprehensive assembly outcome (Supplementary fig. 1). (ii) Employing the Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach (CEGMA) (v2.5)81, we identified 458 core eukaryotic genes, including 248 highly-conserved core genes used to assess genome and annotation completeness (Supplementary table 1). By aligning A. japonicus genes to these 248 core genes, we observed homologous genes in the A. japonicus gene sets for 228 core genes, accounting for 91.94% of the total. These findings further support the relatively complete assembly results. (iii) By aligning Illumina sequencing reads to the nuclear genome using BWA (v0.7.8)82, we determined a read mapping rate of 96.86% and a coverage rate of 99.83%, indicating high mapping efficiency and comprehensive coverage. (iv) The consensus quality value (QV) of genomes representing per-base consensus accuracy was estimated by Merqury83, and the QV of the A. japonicus genome exceeded 45 (48.86), which indicated the high accuracy of the genome assembly. Thus, all of the above results indicated that we obtained the high-quality genome of A. japonicus.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers No. 42076093, 42276143), and Taishan Scholars Program.

Author contributions

L.S. and H.Y. conceived the research project. F.S. and W.C. collected the samples. L.S. and C.J. performed the analyses. L.S., C.J., F.S., W.C. and H.Y. wrote and revised the manuscript. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to L.S. or H.Y.

Code availability

No custom scripts or code were used.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lina Sun, Email: sunlina@qdio.ac.cn.

Hongsheng Yang, Email: hshyang@qdio.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-023-02368-9.

References

- 1.Li Y, et al. Sea cucumber genome provides insights into saponin biosynthesis and aestivation regulation. Cell Discovery. 2018;4:29. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topper TP, Guo J, Clausen S, Skovsted CB, Zhang Z. A stem group echinoderm from the basal Cambrian of China and the origins of Ambulacraria. Nature Communications. 2019;10:1366. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han Q, Keesing JK, Liu D. A review of sea cucumber aquaculture, ranching, and stock enhancement in China. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture. 2016;24:326–341. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2016.1193472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salindeho, N. et al. Anticancer and anticholesterol attributes of sea cucumbers: An opinion in terms of functional food applications. Frontiers in Nutrition. 9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bordbar S, Anwar F, Saari N. High-Value Components and Bioactives from Sea Cucumbers for Functional Foods-A Review. Marine Drugs. 2011;9:1761–1805. doi: 10.3390/md9101761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinch J, Purcell S, Uthicke S, Friedman K. Population status, fisheries and trade of sea cucumbers in the Western Central Pacific. Sea cucumbers. A global review of fisheries and trade. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. 2008;516:7–55. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, J., Lv, Z. & Guo, M. Research advancement of Apostichopus japonicus from 2000 to 2021. Frontiers in Marine Science. 9 (2022).

- 8.Dong Y, Dong S, Ji T. Effect of different thermal regimes on growth and physiological performance of the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus Selenka. Aquaculture. 2008;275:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, et al. Effects of body size and water temperature on food consumption and growth in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka) with special reference to aestivation. Aquaculture Research. 2005;36:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yali, L. et al. Two adaptor molecules of MyD88 and TRAF6 in Apostichopus japonicus Toll signaling cascade: molecular cloning and expression analysis. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhang P, et al. iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals Novel Members Involved in Pathogen Challenge in Sea Cucumber. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Tian M, Chang Y, Xue C, Li Z. Investigation of structural proteins in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) body wall. Scientific reports. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, et al. Identification and expression characterization of WntA during intestinal regeneration in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2017;210:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun L, et al. Metabolic responses to intestine regeneration in sea cucumbers Apostichopus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics. 2017;22:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun, L. et al. Large Scale Gene Expression Profiling during Intestine and Body Wall Regeneration in the Sea Cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics, 195–205 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Huo D, Su F, Yang H, Sun L. Exosomal microRNAs regulate the heat stress response in sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2023;249:114419. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mu, C. et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) of Sea Cucumber: Large-Scale Prediction, Expression Profiling, Non-Coding Network Construction, and lncRNA-microRNA-Gene Interaction Analysis of lncRNAs in Apostichopus japonicus and Holothuria glaberrima During LPS Challenge and Radial Organ Complex Regeneration. Marine Biotechnology. 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sun L, et al. iTRAQ reveals proteomic changes during intestine regeneration in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics. 2017;22:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Zheng Y, Sun L, Chen M. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Signatures of Sea Cucumber Apostichopus japonicus during Environmental Induced Aestivation. Genes. 2020;11:1020. doi: 10.3390/genes11091020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui W, et al. Construction of a High-Density Genetic Linkage Map for the Mapping of QTL Associated with Growth-Related Traits in Sea Cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) Biology. 2022;11:50. doi: 10.3390/biology11010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian, M. et al. Construction of a High-Density Genetic Map and Quantitative Trait Locus Mapping in the Sea Cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Scientific reports. 5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhang X, et al. The sea cucumber genome provides insights into morphological evolution and visceral regeneration. PLOS Biology. 2017;15:e2003790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, et al. Identification of sex determination locus in sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus using genome-wide association study. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:391. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08632-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan, J. et al. Recent advances in crustacean genomics and their potential application in aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture (2023).

- 25.Wallace, J., Rodgers-Melnick, E. & Buckler, E. On the Road to Breeding 4.0: Unraveling the Good, the Bad, and the Boring of Crop Quantitative Genomics. Annual Review of Genetics. 52 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Chen B, Feder ME, Kang L. Evolution of heat‐shock protein expression underlying adaptive responses to environmental stress. Molecular ecology. 2018;27:3040–3054. doi: 10.1111/mec.14769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng HY, Concepcion GT, Feng XW, Zhang HW, Li H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods. 2021;18:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belton, J.-M. et al. Hi-C: A comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods (San Diego, Calif.). 58 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.van Berkum, N. L. et al. Hi-C: a method to study the three-dimensional architecture of genomes. J Vis Exp. (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Rao SS, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wingett S, et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res. 2015;4:1310. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7334.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Zhang S, Zhao Q, Ming R, Tang H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nat Plants. 2019;5:833–845. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, et al. Allele-defined genome of the autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum L. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i351–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jurka J, et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;Chapter 4:4.10.11–14.10.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar RC, Myers EW. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i152–158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubley, R. GitHub repositoryhttps://github.com/rmhubley/RepeatMasker/blob/master/util/createRepeatLandscape.pl (2023).

- 41.Rosen, J. GitHub repositoryhttps://github.com/rmhubley/RepeatMasker/blob/master/util/calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl (2020).

- 42.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mount DW. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) CSH Protoc. 2007;2007:pdb.top17. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffiths-Jones S, et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanco E, Parra G, Guigó R. Using geneid to identify genes. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2007;Chapter 4:Unit 4.3. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0403s18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR1791184

- 52.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR10002625

- 53.2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. DRR248857

- 54.2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22815403

- 55.2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. ERR9709336

- 56.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR8499555

- 57.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR9408421

- 58.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D457–462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Finn RD, et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D190–d199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finn RD, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulder N, Apweiler R. InterPro and InterProScan: tools for protein sequence classification and comparison. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;396:59–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-515-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22523578

- 71.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22799261

- 72.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23640106

- 73.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23640107

- 74.2021. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR17056084

- 75.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362389

- 76.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362390

- 77.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362391

- 78.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362392

- 79.Sun L. 2023. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li H. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rhie A, Walenz BP, Koren S, Phillippy AM. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biology. 2020;21:245. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR1791184

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR10002625

- 2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. DRR248857

- 2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22815403

- 2022. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. ERR9709336

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR8499555

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR9408421

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22523578

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR22799261

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23640106

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23640107

- 2021. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR17056084

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362389

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362390

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362391

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR23362392

- Sun L. 2023. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No custom scripts or code were used.