Abstract

Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) are essential for membrane receptor regulation but often remain unresolved in structural studies. TRPV4, a member of the TRP vanilloid channel family involved in thermo- and osmosensation, has a large N-terminal IDR of approximately 150 amino acids. With an integrated structural biology approach, we analyze the structural ensemble of the TRPV4 IDR and the network of antagonistic regulatory elements it encodes. These modulate channel activity in a hierarchical lipid-dependent manner through transient long-range interactions. A highly conserved autoinhibitory patch acts as a master regulator by competing with PIP2 binding to attenuate channel activity. Molecular dynamics simulations show that loss of the interaction between the PIP2-binding site and the membrane reduces the force exerted by the IDR on the structured core of TRPV4. This work demonstrates that IDR structural dynamics are coupled to TRPV4 activity and highlights the importance of IDRs for TRP channel function and regulation.

Subject terms: Biophysics, Transient receptor potential channels

An integrated structural biology approach uncovers the structural complexity of the intrinsically disordered region (IDR) within the TRPV4 ion channel. Multiple stimulatory and inhibitory elements were identified within the IDR that modulate channel activity in a lipid-dependent manner.

Introduction

The majority of eukaryotic ion channels contain intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which play important roles in protein localization, channel function and the recruitment of regulatory interaction partners1–3. In some transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, IDRs make up more than half of the entire protein sequence4. Among the mammalian TRP vanilloid (TRPV) subfamily, TRPV4 has the largest N-terminal IDR, ranging from ~130 to ~150 amino acids in length depending on the species4–6. TRPV4 is a Ca2+-permeable plasma membrane channel that is widely expressed in human tissues. It is remarkably promiscuous, and stimuli include pH, moderate heat, osmotic and mechanical stress, and various chemical compounds7,8. TRPV4 also garnered attention due to the large number of disease-causing mutations with distinct tissue-specific phenotypes primarily affecting the nervous and skeletal systems9–13. Among others, roles in cancer as well as viral and bacterial infections have also been described14–16.

Crystal structures of the isolated TRPV4 ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) were among the first regions of a TRP channel to be resolved, showing a compact, globular protein domain with six ankyrin repeats10,17,18. Together with the IDR, the ARD forms the channel’s cytoplasmic N-terminal domain (NTD). Furthermore, near full-length frog and human TRPV4 cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography structures are available, but lack the IDR, which was partially or fully deleted to facilitate structure determination or not visible in the final structure19–22. Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, we have previously shown that the TRPV4 IDR lacks appreciable secondary structure content5. Short stretches of N- and C-terminal IDRs were seen to interact with the ARD in TRPV channel cryo-EM structures23–25, but no structural ensemble of a complete TRP(V) channel IDR has been visualized to date.

The TRPV4 NTD is responsible for channel sensitivity to changes in cell volume26, its reaction to osmotic and mechanical stimuli27,28 and the interaction with regulatory binding partners29–32. Therefore, a structural characterization of the TRPV4 NTD including its large IDR is critical to understanding TRPV4 regulation in detail.

To date, two regulatory elements in the N-terminal TRPV4 IDR have been described: (i) a proline-rich region directly preceding the ARD that enables protein-dependent channel desensitization;29,30,32 and (ii) a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)-binding site composed of a stretch of basic and aromatic residues directly N-terminal to the proline-rich region33. PIP2 is a plasma membrane lipid and an important ion channel regulator34,35. In TRPV4, mutation of the PIP2-binding site abrogates PIP2-dependent channel sensitization in response to osmotic and thermal stimuli33. The lack of information on the role of additional IDR regions for channel regulation prompted us to investigate the TRPV4 IDR in more detail. In analogy to the integrative structural biology approach, which aims to build a consistent structure of a biological macromolecule or complex36, the central aim of our study was to derive a cohesive functional model for TRPV4 regulation by its IDR through the integration of diverse experimental and computational methods on a range of TRPV4 deletion constructs and mutants.

In this work, we map hierarchically coupled regulatory elements linking the NTD’s structural dynamics to channel activity along the entire length of the IDR and find them to modulate channel activity through lipid-dependent transient crosstalk. A highly conserved patch in the N-terminal half acts as an autoinhibitory element by modulating PIP2 binding to the PIP2-bindig site in the C-terminal half of the IDR. Using coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we propose a force-dependent mechanism for how the conductive properties of the channel may be modulated via the ARD through a membrane-bound IDR. Furthermore, combining small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), NMR and tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy with cross-linking and H/D exchange mass spectrometry (XL-MS, HDX-MS) as well as atomistic MD simulations, we analyze the structural ensemble of the TRPV4 N-terminal domain and derive a structural model of a TRP channel with its extensive IDR. Our results highlight important regulatory functions of the IDR and underscore that the IDRs cannot be neglected when trying to understand TRP channel structure and function.

Results

Structural ensemble of the TRPV4 N-terminal intrinsically disordered region

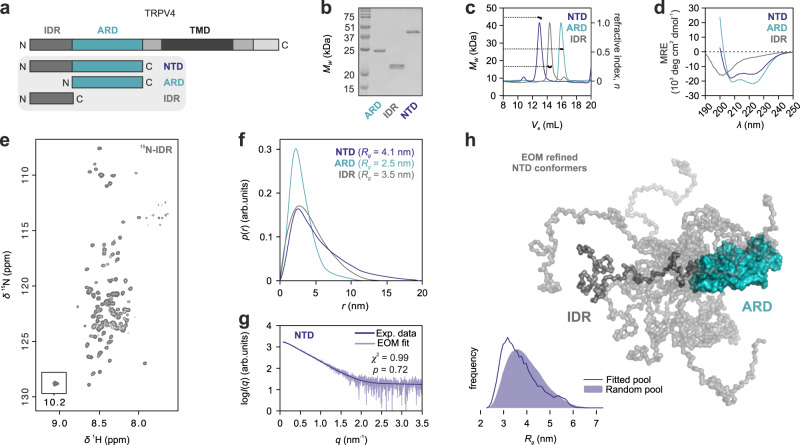

To address the current lack of structural and dynamic information for the TRPV4 NTD, we purified the 382 amino acid Gallus gallus domain (residues 2–382, with 83/90% sequence identity/similarity to human TRPV4) as well as its isolated IDR (residues 2–134), and ARD (residues 135–382) (Fig. 1a–c, Supplementary Fig. 1). The avian proteins were chosen due to their increased stability compared to their human counterparts29. Analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and SEC-MALS (SEC multi-angle light scattering) showed that these constructs are monomeric, while circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and the narrow chemical shift dispersion of the [1H, 15N]-TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra of the 15N-labeled TRPV4 IDR in isolation or in the context of the NTD confirmed its high amount of disorder5 (Fig. 1c–e; Supplementary Fig. 2). Chemical shift based secondary structure predictions showed that the TRPV4 IDR contains no appreciable secondary structure5.

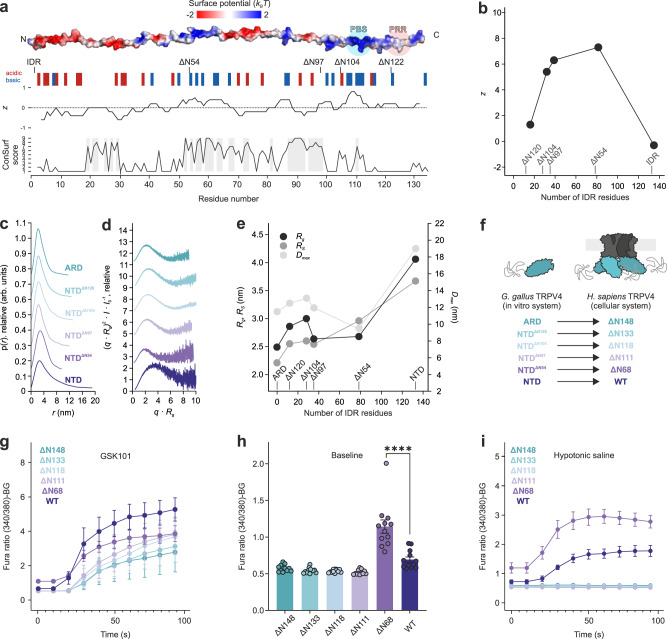

Fig. 1. Structural ensemble of the TRPV4 N-terminal domain.

a TRPV4 N-terminal constructs used for structural analyses. b–d Purified TRPV4 N-terminal constructs analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE b, SEC-MALS c, and CD spectroscopy d. SDS-PAGE in b comparing all constructs side by side was carried out once to evaluate sample purity and respective molecular weight. e [1H, 15N]-TROSY-HSQC NMR spectrum of 15N-labeled TRPV4-IDR (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for backbone assignments). f, g SAXS pair-distance-distribution f and SAXS EOM (Ensemble Optimization Method) g, both in arbitrary units (arb. units), of TRPV4 N-terminal constructs (Supplementary Fig. 3). The real-space distance distribution yields a radius of gyration of Rg = 3.4 nm with a maximal particle dimension of Dmax = 14.0 nm for the IDR, Rg = 4.1 nm and Dmax = 19 nm for the NTD as well as Rg = 2.5 nm and a Dmax = 11.5 nm for the ARD. Every protein exhibits levels of conformational heterogeneity and the p(r) profiles should be interpreted as the summed volume-fraction weighted contribution within the sample population, and not as single-particle distributions. The statistical analyses of the fit in g was carried out using the reduced χ2 method93 (one-tailed distribution) and CorMap64 (one-tail Schilling distribution) test methods. The determined χ2 and CorMap p values are indicated in the corresponding graph. h NTD ensemble refined by EOM (Ensemble Optimization Method)37,38. Using a chain of dummy residues for the IDR and the X-ray structure of the TRPV4 ARD (PDB: 3W9G) as templates, a library of 10,000 NTD structures was generated and refined against the experimental data, allowing the comparison of the fitted versus the random pool and selecting a sub-set of ensemble-states representing the experimental data. Ten IDR conformers best representing the experimental scattering profile are depicted. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) probes the molecular shape of a molecule in solution. An IDR-containing protein is best described as a structural ensemble, rather than as a single structure, which can be analyzed by SEC-coupled small-angle X-ray scattering (SEC-SAXS) and subsequent Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) analysis37,38. The isolated TRPV4 IDR is highly flexible and fluctuates between numerous conformations that, as a population, produce a skewed real-space scattering pair-distance distribution function, or p(r) profile that extends to ~12.5–15 nm (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 3). Compared to a randomly generated pool of solvated, self-avoiding walk structures, the TRPV4 IDR preferentially sampled more compact states both in isolation and attached to the ARD, suggesting the presence of transient intradomain contacts (Fig. 1f–h, Supplementary Fig. 3). Interdomain contacts between the IDR and ARD were also apparent from the loss of signal intensities in the 1H, 15N-NMR spectra of the 15N-labeled IDR compared to the NTD (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c), e.g., for residues ~20–35 and ~55–115. The ARD itself was not resolved in the spectra of the NTD likely due to unfavorable dynamics.

Structural dynamics of the TRPV4 ARD

The SAXS data, the dimensionless Kratky plot and the resulting p(r) profile of the isolated ARD are typical of a more compact particle, especially in comparison to the IDR (Supplementary Fig. 3). Accordingly, the 28 kDa ARD has a significantly smaller radius of gyration (Rg ~ 2.5 nm) and maximum particle dimension (Dmax ~ 11.5 nm) than the 15 kDa IDR (Rg ~ 3.5 nm; Dmax ~ 12.5–15 nm). However, the SAXS data do not allow a straight-forward analysis of possible intradomain dynamics of the ARD.

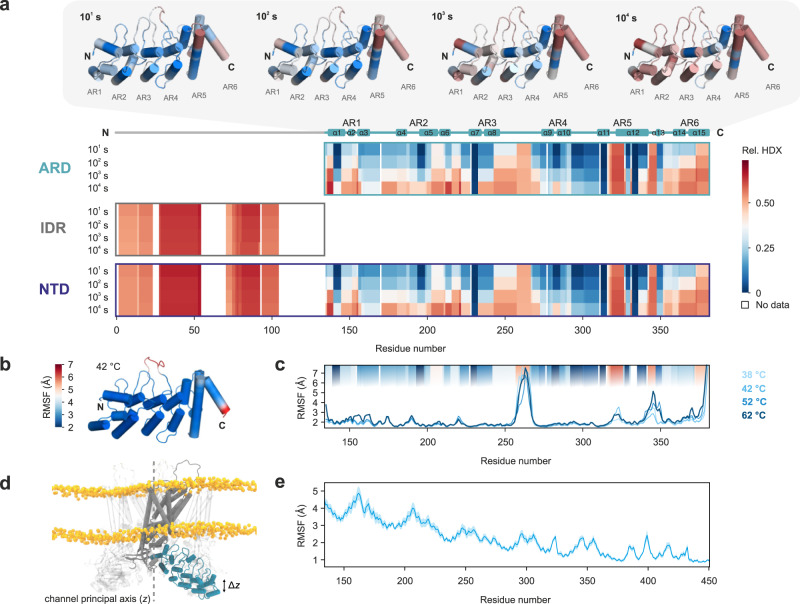

To evaluate the structural flexibility of the ARD in solution, we used hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Data 1 and 2). HDX-MS probes the peptide bonds’ amide proton exchange kinetics with the solvent and thus provides insights into the higher order structure of proteins and their conformational dynamics39. Both the isolated ARD and IDR domains and the entire TRPV4 NTD were subjected to HDX for different periods of time, and subsequently digested with porcine pepsin to assess where HDX occurred. The obtained peptides covered the entire ARD domain, but only a limited peptide coverage of the IDR could be achieved (i.e., 64.7%, see Supplementary Data 1 and 2) possibly owing to insufficient proteolytic digestion of the IDR or/and poor chromatographic properties or ionization of the generated peptides. For the IDR, rapid high HDX was apparent in the resolved parts (residues 3–24, 29–55, and 72–105) substantiating its unstructured character. The transient nature of interdomain contacts between ARD and IDR was underscored by the absence of a significant difference in the HDX of the individual domains in isolation or in the context of the full-length NTD.

Fig. 2. Structural dynamics of the TRPV4 ARD.

a HDX of TRPV4 NTD and its isolated subdomains. Low (blue) to high (red) HDX shown for four time points. Areas without HDX assignment are colored white. For the ARD, HDX was visualized on the available X-ray structure of the G. gallus TRPV4 ARD (PDB: 3W9G). The six ankyrin repeats (AR) are indicated on top of the heat map diagram. b, c Root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) obtained from atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the isolated G. gallus TRPV4 ARD in solution. RMSF at 42 °C mapped onto the ARD X-ray structure (PDB: 3W9G) b and RMSF per residue in simulations at increasing temperatures c. For comparison, HDX profiles after 102 s from a are displayed in the plot background. d, e RMSF of the ARD with respect to the central TRPV4 axis obtained from 1 µs long MD simulations of the complete TRPV4 core (see also Supplementary Movie 1). d Schematic depiction of the MD simulation setup. The channel principal axis (defined as z) is indicated as a dashed vertical line. The RMSF was calculated as the square root of the variance of the motion along this axis (∆z). e RMSF of TRPV4 residues 134–450 comprising the ARD. The solid line represents the average RMSF from all four protomers, the light area indicates the standard error of the mean. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Immediate high HDX was apparent for ARD loop 3 (residues 259–267), ankyrin repeat 5 (residues 319-327) and the linker between ankyrin repeats 5 and 6 (residues 344–348). Most ɑ-helices showed progression in HDX over time except for ɑ7 (repeat 3), ɑ9/ɑ10 (repeat 4), and ɑ11/ɑ12 (repeat 5) suggesting that these constitute the structural core of the ARD with the least flexibility. The peripheral ankyrin repeats 1, 2, and 6 underwent faster exchange (HDX at 103 s). Complex conformational dynamics, i.e., slower motions in the ARD core and faster dynamics within the ARD loops and peripheral ankyrin repeats, are also in agreement with the extensive line broadening observed in the NTD’s [1H, 15N]-TROSY-HSQC NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Importantly, the HDX data for the ARD matches the dynamic pattern observed in our MD simulations (Fig. 2b, c) and indicate that the domain is stable in the sub-µs timescale, possibly an important prerequisite to transduce signals between IDR and transmembrane core. To investigate this further, we conducted atomistic MD simulations on the core G. gallus TRPV4 channel embedded in a lipid bilayer membrane (Fig. 2d, e, Supplementary Movie 1). Similar to its behavior in isolation, the ARD shows only subtle conformational fluctuations in the context of a TRPV4 homotetramer. Notably, protein dynamics in loop 3 and the C-terminal ankyrin repeat were reduced in the TRPV4 tetramer compared to the isolated ARD owing to their involvement in extensive intra- and inter-subunit contacts. Overall, our data suggest that the ARD is stable on the relevant time scales required to act as a putative signal transducer between IDR and transmembrane domain (see below).

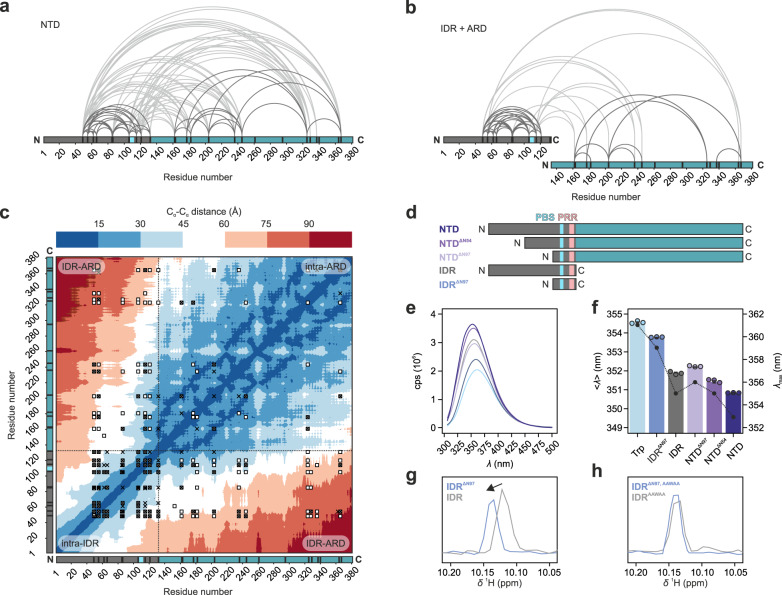

Long-range TRPV4 NTD interactions center on the PIP2-binding site

Long-range interactions between IDR and ARD were investigated using crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS). Except for the first 49 amino acids, 25 lysine residues are almost evenly distributed throughout the G. gallus TRPV4 NTD sequence. The lysine side chain amino groups can be crosslinked by disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS), probing Cα-Cα distances up to 30 Å40. Both intradomain (within IDR or ARD) and interdomain (between IDR and ARD) crosslinks were observed for the NTD (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 3). Many intra- and interdomain contacts were observed for the most N-terminal IDR lysine residues (K50, K56) and those within or close to the PIP2-binding site on the C-terminal end of the IDR (K107, K116, K122). Importantly, these crosslinks were replicated in an equimolar mix of isolated IDR and ARD, supporting the involvement of these IDR regions in specific long-range interactions (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Data 3).

Fig. 3. Long-range intra- and interdomain interactions of the TRPV4 NTD.

a, b Cross-linking mass spectrometry was used to probe interactions within and between IDR and ARD using either a the entire NTD or b isolated IDR (gray) and ARD (cyan) in a 1:1 ratio. Lysine residues are indicated by black tick marks, the PIP2-binding site is marked light blue. Intradomain crosslinks are shown by curved lines in dark gray, interdomain crosslinks in light gray. c Heat map of Cɑ-Cɑ distances for an NTD conformational ensemble consisting of 15 EOM-refined conformers based on SAXS data of the NTD (Fig. 1h). Crosslinks are highlighted by white squares (NTD), black crosses (equimolar ARD:IDR mixture) or white squares filled with black crosses (both experimental set-ups). d TRPV4 N-terminal constructs used for tryptophan fluorescence (PBS: PIP2-binding site, PRR: proline rich region). e, f Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy of TRPV4 N-terminal constructs (IDR, NTD, NTDΔN54 and NTDΔN97 lacking the first 54 or 97 amino acids, respectively, and IDRΔN97 (comprising PIP2 binding site, surrounding basic residues and proline rich region) or isolated amino acid in buffer (Trp). Residue W109 in the PIP2 binding site is the sole tryptophan residue in the entire NTD. Fluorescence intensity is presented in counts per second (cps). Bars represent the intensity weighted fluorescence emission wavelength <λ > (left axis). Data are presented as the mean value ± SEM from n = 3 individual experiments. The fluorescence emission maximum λmax is shown by black circles connected through dotted lines (right axis). g, h 1H chemical shift differences of W109 sidechain amide between IDR and IDRΔN97 as well as their respective counterparts harboring the PIP2 binding site (107KRWRR111) mutation to 107AAWAA111. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Conveniently, the TRPV4 PIP2-binding site (consensus sequence KRWRR) important for TRPV4 sensitization33 contains the sole tryptophan residue within the ~43 kDa NTD (W109 in our constructs).

Changes in the chemical environment of the PIP2-binding site, e.g., through altered protein contacts, can thus be probed directly by differences in the tryptophan fluorescence spectra of deletion constructs generated around the PIP2-binding site (Fig. 3d).

The fluorescence emission of a minimal construct (IDRΔN97, residues 97–134), which included the PIP2-binding site and the proline-rich region, was suggestive of high solvent accessibility of the tryptophan residue and resembled that of free tryptophan in buffer (Fig. 3e, f). In longer constructs containing the ARD, additional parts of the IDR, or both, the fluorescence emission was blue shifted, indicating that W109 was in a more buried, hydrophobic environment. This effect was most pronounced for the full-length NTD, while deletion of the N-terminal half of the IDR (NTDΔN54) yielded an intermediate emission wavelength between full-length NTD and NTDΔN97, a construct comprising only the ARD, proline-rich region, and PIP2-binding site. This indicates that the local PIP2-binding site environment is influenced by both the ARD and the distal IDR N-terminus.

The PIP2-binding site promotes compact NTD conformations

To probe the PIP2-binding site’s role for the NTD conformational ensemble, we replaced its basic residues by alanine (KRWRR → AAWAA) across TRPV4 N-terminal constructs (Supplementary Fig. 4a–d). CD spectroscopy and SEC showed that the structural integrity of the mutants was maintained (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). However, we noticed consistently higher Stokes radii for the mutants compared to their native counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 4e), suggesting that the charge neutralization of the PIP2-binding site affects the IDR structural ensemble. Interestingly, the 1H chemical shift of the W109 sidechain amide is different between the native IDR and IDRΔN97. In contrast, this chemical shift is the same when comparing the respective PIP2-binding site mutants (Fig. 3g, h). Thus, transient long-range interactions between the N-terminus and the PIP2-binding site seem to be disrupted upon mutation of the PIP2-binding site. Likewise, the tryptophan emission wavelength of the AAWAA mutants was also increased compared to the native constructs, indicative of a more solvent-exposed central tryptophan residue (Supplementary Fig. 4f, g).

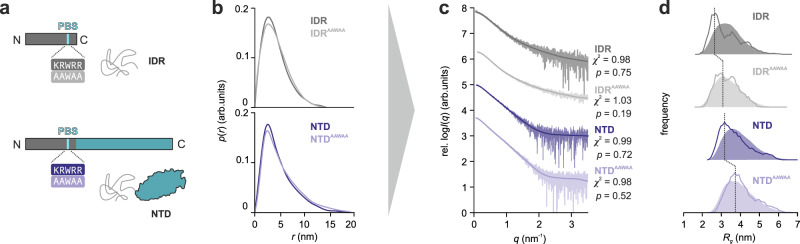

NTDAAWAA and IDRAAWAA were also analyzed by SEC-SAXS and EOM (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 4h–o). The scattering profile and real-space distribution of IDRAAWAA resembled the native IDR, indicating a random chain-like protein. However, the mutant’s Rg and Dmax values (3.5 nm and 14.5 nm, respectively) were slightly increased compared to the native IDR (Rg = 3.4 nm and Dmax = 14.0 nm). This effect was even more pronounced in the context of the NTD, with Rg and Dmax values of 4.5 nm and 19.5 nm, respectively, compared to Rg = 4.1 nm and Dmax = 19.0 nm for the native IDR. Unlike the native IDR and NTD, the Rg distributions of the mutant constructs obtained from EOM analysis agreed well with the randomly generated pools of solvated, self-avoiding walk structures (Fig. 4d). This suggests that constructs with a mutated PIP2-binding site populate expanded conformations more frequently and show more random chain-like characteristics, thereby substantiating the role of the PIP2-binding side as a central mediator of long-range contacts within the TRPV4 NTD.

Fig. 4. The PIP2-binding site promotes compact IDR conformations.

a Constructs used in SEC-SAXS experiments. b Real-space pair-distance distribution functions, or p(r) profiles, in arbitrary units (arb. units), calculated for IDR and IDRAAWAA (gray curves) as well as NTD and NTDAAWAA (blue curves). p(r) functions were scaled to an area under the curve of 1. The real-space distance distribution of IDRAAWAA yields a radius of gyration of Rg = 3.5 nm with a maximal particle dimension of Dmax = 14.5 nm (native IDR: Rg = 3.4 nm, Dmax = 14.0 nm). NTDAAWAA has a Rg = 4.5 nm and a Dmax = 19.5 nm (native NTD: Rg = 4.1 nm, Dmax = 19.0 nm). c Fit between EOM-refined IDR and NTD models and experimental scattering data, in arbitrary units (arb. units). The statistical analyses of the fits were carried out using the reduced χ2 method93 (one-tailed distribution) and CorMap64 (one-tail Schilling distribution) test methods. The determined χ2 and CorMap p values are indicated in the corresponding graphs. d Comparison between Rg values of IDR and NTD variants between random pool structure library (solid area) and EOM refined models (dotted line). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Competing attractive and repulsive interactions between distinct IDR regions govern the NTD structural ensemble

The TRPV4 IDR consists of alternating highly conserved and non-conserved regions arranged along a charge gradient. An N-terminus rich in acidic residues segues into a C-terminus with an accumulation of basic residues followed by the proline-rich region connecting to the ARD (Fig. 5a, b). To probe the effects of differently charged and conserved IDR regions on the NTD structural ensemble, consecutive N-terminal deletion constructs were investigated by CD spectroscopy, SEC, and SEC-SAXS (Fig. 5c–e, Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). The respective RS, Rg and Dmax values for consecutive N-terminal deletions do not change linearly, rather, depending on their charge (z), individual IDR regions mold the structural ensemble of the NTD differently (Fig. 5e). Addition of only the proline-rich region to the ARD (NTDΔN120) notably increased the RS, Rg and Dmax values. This expansion is likely due to the formation of a polyproline helix29. A construct containing both the PIP2-binding site and the basic residues preceding it (NTDΔN97) showed an increase in compaction over the construct with the PIP2-binding site alone (NTDΔN104) suggesting cumulative effects of the regions surrounding the PIP2-binding site for NTD structure compaction. Adding another ~40 residues yields NTDΔN54, which includes the entire basic and highly conserved central stretch of the IDR, did not significantly increase the protein dimensions further underscoring the importance of the central IDR region for intra- and interdomain crosstalk. This is supported by NMR spectroscopy, where the region between residues 55 and 115 showed notable peak broadening in the context of the entire NTD compared to the isolated IDR (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Finally, the full-length NTD including the more acidic N-terminal IDR had significantly increased protein dimensions compared to NTDΔN54, indicating that the overall structural ensemble of the TRPV4 NTD is modulated by competing attractive and repulsive influences exerted by distinct IDR regions.

Fig. 5. The distal N-terminus affects the structural NTD ensemble and TRPV4 channel activity.

a Topology of NTD truncations showing the charge distribution z (www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/charge) and sequence conservation (ConSurf50) along the IDR. b Overall charge (z) in the IDR at physiological pH (7.4) depending on the IDR length (values determined with ProtPi, www.protpi.ch). c Normalized real-space distance distribution p(r), in arbitrary units (arb. units), of NTD and NTD deletion constructs. d Dimensionless Kratky plot of NTD and NTD deletion mutants. e Radius of gyration (Rg) and Stokes radius (RS) determined from the real-space distance distribution in a and the SEC analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5c), respectively, plotted versus the number of IDR residues the NTD constructs. The maximum particle dimension (Dmax) is plotted on the right y-axis. f N-terminal deletion mutants in the in vitro (G. gallus) and in cellulo (H. sapiens) systems. g Activation of TRPV4 constructs with the synthetic agonist GSK101 shows plasma membrane targeting and structural integrity of all constructs. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 6 biologically independent experiments, each with 10–30 cells per field of view. h Basal Ca2+ levels in MN-1 cells expressing different TRPV4 constructs. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 12 biologically independent experiments, each with 10–30 cells per field of view. The **** indicates a p value of p < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). i Stimulation of Ca2+ flux by hypotonic saline at t = 20 s in MN-1 cells expressing different TRPV4 constructs. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 6 biologically independent experiments, each with 10–30 cells per field of view. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A conserved patch in the N-terminal half of the IDR autoinhibits channel activity and acts on the PIP2-binding site

To investigate the role of individual IDR regions on channel function, Ca2+ imaging of human TRPV4 N-terminal deletion constructs expressed in the mouse motor neuron cell line MN-1 was performed as described previously31 (Fig. 5f–i). All constructs were successfully targeted to the plasma membrane and structurally intact, as seen by the ability of the synthetic agonist ‘GSK101’41 to reliably activate the proteins (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 7a). All mutants had basal Ca2+ levels similar to the full-length channel. Only H. sapiens TRPV4ΔN68 (corresponding to G. gallus TRPV4ΔN54) had strongly increased basal Ca2+ levels (Fig. 5h). Deletion of the entire IDR (hsTRPV4ΔN148), as well as constructs retaining additional IDR regions, i.e., the proline-rich region (hsTRPV4ΔN133/ggTRPV4ΔN120), the PIP2-binding site (hsTRPV4ΔN118/ggTRPV4ΔN104) and the preceding basic residues (hsTRPV4ΔN111/ggTRPV4ΔN97) yielded a channel non-excitable for osmotic stimuli (Fig. 5i). In contrast, hsTRPV4ΔN68 was hypersensitive to osmotic stimuli and its Ca2+ influx far exceeded that of the native channel, indicating that the IDR N-terminus acts as a dominant autoinhibitory element. Furthermore, the data show that the PIP2-binding site is not sufficient for osmotic channel activation but additionally requires the presence of the central IDR around residues ~68–111 ( ~ 54–97 in ggTRV4).

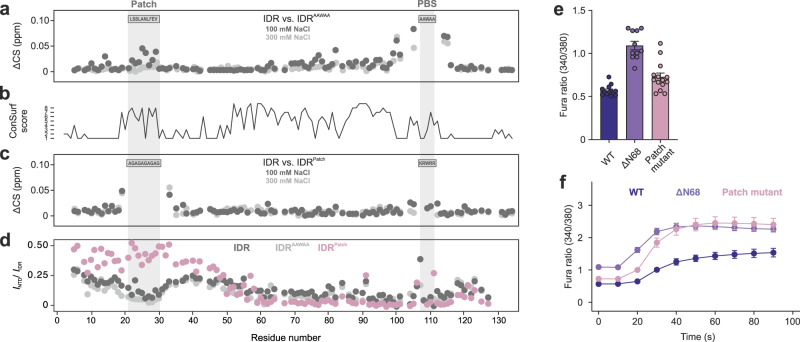

Nonetheless, we hypothesized that the site(s) in the N-terminal half of the IDR responsible for the observed channel autoinhibition and lipid binding attenuation may act via the channel’s PIP2-binding site. Thus, we compared the native IDR and IDRAAWAA NMR backbone amide chemical shifts to reveal interactions between the N- and C-terminal ends of the IDR (Fig. 6a). The largest chemical shift differences were naturally found in and around the mutated PIP2-binding site itself and to a lower degree in the central IDR. Additionally, a region encompassing residues ~20–30 in the IDR N-terminus also showed notable chemical shift differences. This patch is the only conserved stretch in the N-terminal half of the IDR (consensus sequence FPLS-S/E-L-A/S-NLFE (19/31FPLSSLANLFE29/41 in gg/hsTRPV4)) (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 6. A highly conserved patch in the N-terminal TRPV4 IDR transiently interacts with the C-terminal PIP2 binding site and autoinhibits TRPV4 function.

a Chemical shift differences at high and low salt between 15N-labeled native IDR and IDRAAWAA with a mutated PIP2 binding site (PBS) shows that mutagenesis of the PBS leads to chemical shift changes in the conserved N-terminal patch. At the higher salt concentration (light gray), these chemical shift perturbations are significantly reduced. b Degree of conservation in TRPV4 IDR determined with ConSurf50 (Supplementary Fig. 11). c Chemical shift differences at high and low salt between 15N-labeled IDR and IDRPatch with a mutation in the conserved N-terminal patch shows that mutagenesis leads to chemical shift changes in the PBS. At the higher salt concentration (light gray), these chemical shift perturbations are significantly reduced. d Relative peak intensity of IDR, IDRAAWAA and IDRPatch residues in the isolated IDR or in context of the ARD (i.e., NTD, NTDAAWAA or NTDPatch). All protein concentrations used were 100 µM. A value of 0.5 indicates that peak intensities for a respective IDR residue are halved when the ARD is present, a value of zero represents complete line broadening in the context of the NTD. Accordingly, lower values are indicative of IDR/ARD interactions. e, f Ca2+ imaging of hsTRPV4 variants expressed in MN-1 cells. e Basal Ca2+ and f hypotonic treatment at t = 20 s show increased activity of the patch mutant. For better comparison, data for TRPV4ΔN68 are replotted from Fig. 5h, i. Data in e are presented as mean values ± SEM from n = 13 (TRPV4), 11 (TRPV4ΔN68), 14 (TRPV4Patch) and in f from n = 12 (TRPV4, TRPV4ΔN68, and TRPV4Patch) biologically independent experiments, each with 10–30 cells per field of view. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Since our NMR data showed that the patch region is unstructured5 (Supplementary Fig. 2), we replaced it with an (AG)5 repeat to avoid ɑ-helix formation (Supplementary Fig. 8). NMR relaxation data confirmed the absence of transient structure formation in the IDRPatch mutant (Supplementary Fig. 9). Importantly, the PIP2-binding site residues’ resonances in the IDRPatch mutant showed chemical shift changes compared to the native IDR (Fig. 6c), confirming that patch and PIP2-binding site on opposite ends of the IDR are in transient contact. The patch apparently also undergoes additional transient interactions with the ARD since the NMR signal intensities of residues in and around the patch region in the native IDR and IDRAAWAA constructs showed significant line broadening within the context of the NTD but not in the isolated IDR. This effect was abrogated in the IDRPatch mutant (Fig. 6d).

To elucidate the role of the patch for channel function, the full-length human TRPV4 channel harboring the patch mutant was expressed in MN-1 cells (Fig. 6e, f, Supplementary Figs. 7b and 8). Compared to the native channel, TRPV4Patch displayed significantly increased basal Ca2+ levels and osmotic hyperexcitability, as previously seen for TRPV4ΔN68. This shows that the conserved patch in the N-terminal IDR is the dominant module responsible for autoinhibiting channel activity.

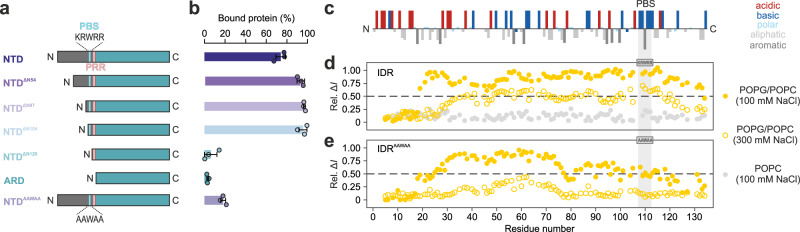

The N-terminal half of the TRPV4 IDR modulates IDR lipid binding

Lipids and lipid-like molecules are important TRPV4 functional regulators33,42–44, but beyond the PIP2-binding site, lipid interactions with the TRPV4 NTD have not been probed in detail. A previously proposed lipid binding site in the ARD42 seems implausible because it does not face the membrane in the context of the full-length channel19,20. Using the complementary N-terminal deletion mutants from our cell-based activity assay, we probed their interaction with liposomes (Fig. 7). Indeed, neither the isolated ARD, nor NTDΔN120, also containing the proline-rich region, interacted with POPC/POPG liposomes in a sedimentation assay (Fig. 7a, b, Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). In contrast, ~75% of the native NTD was found bound to liposomes. For NTDAAWAA, lipid binding was reduced to ~20%, indicating that the PIP2-binding site is a major, but not the only lipid interaction site in the TRPV4 IDR. Deletion of the IDR N-terminal half slightly increased the fraction of lipid-bound protein. Incidentally, “protection” of the PIP2-binding site from lipid binding by the N-terminal IDR was also observed with tryptophan fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 10c–g) and may indicate that in the native IDR long-range intra-domain contacts compete with lipid binding.

Fig. 7. Extensive lipid binding in the IDR is negatively affected by the distal N-terminus.

a Topology of N-terminal deletion mutants used for liposome sedimentation assay. b Protein distribution between pellet (“bound protein”) or supernatant fraction after centrifugation, quantified via densitometry of SDS-PAGE protein bands using imageJ51. Data are presented as the mean value ± SEM from n = 3 individual experiments. c Distribution of charged and hydrophobic residues in the TRPV4-IDR shows a gradient of a consecutively more basic and hydrophobic protein from N- to C-terminus. Plotted with the PepCalc tool (https://pepcalc.com/). d, e NMR signal intensity differences for 15N-labeled IDR variants (100 µM) in the absence and presence of POPC (light gray circles) or POPC-POPG containing liposomes at low (filled yellow circles) or high salt concentration (open yellow circles). Higher values are indicative of lipid binding. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

NMR chemical shift perturbation assays allowed identification of the lipid-interacting IDR residues (Fig. 7c–e, see Supplementary Fig. 11 for 13C, 15N-labeled IDRAAWAA backbone assignments). In the native IDR, ~75% of all residues showed line-broadening in the presence of POPG-containing liposomes. Coarse-grained MD simulations of the IDR on a plasma membrane mimetic corroborated the NMR experiments (Supplementary Fig. 12). Lipid interactions were seen to be dominated by the PIP2 binding site, the central IDR and a conserved N-terminal patch (see below). In MD simulations with IDRAAWAA, lipid interactions were severely reduced in the PIP2-binding site, again agreeing with the NMR data (Fig. 7e, Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Fig. 12).

Indicating an electrostatic contribution, an increase in salt concentration or the use of net-neutral POPC liposomes in NMR experiments reduced the observed line broadening for both native IDR and IDRAAWAA (Fig. 7d, e, Supplementary Fig. 12c). Interestingly, the MD simulations also suggested a general preference for negatively charged PIP2 over other membrane constituents for both the PIP2-binding site and the central IDR (Supplementary Fig. 12).

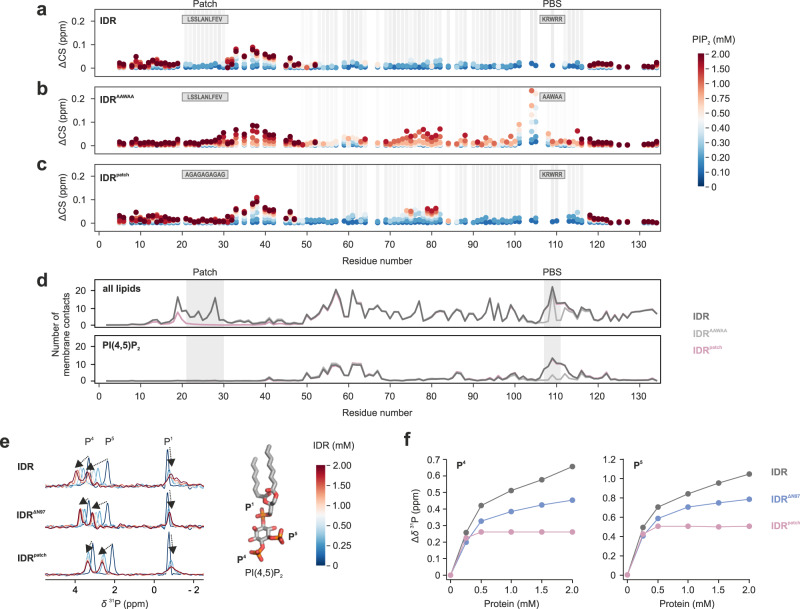

The conserved patch competes with PIP2 for binding to the PIP2-binding site

To explore the extent of PIP2 binding to the IDR, and the possible role of the autoinhibitory patch, we carried out NMR chemical shift perturbation assays with 15N-labeled IDR variants (Fig. 8a–c). In the native IDR, residues within and around the PIP2-binding site (residues ~100–115), the central IDR (residues ~55–100) and the autoinhibitory patch (residues ~20–30) show the strongest responses to diC8-PIP2 addition (Fig. 8a). The effect of PIP2 on the autoinhibitory patch (Supplementary Fig. 8a) can be explained by the interactions of the patch with the PIP2-binding site detected in the NMR experiments (Fig. 6a) and the coarse-grained MD simulations of the membrane-bound IDR (Fig. 8d, S12a–c). In the simulations, a substantial local increase in PIP2 was observed around the PIP2-binding site and the central IDR, but not in the patch region. This indicates that the observed NMR chemical shifts within the N-terminal patch are secondary effects, presumably based on altered protein-protein interactions upon PIP2 addition. Notably, in the native IDR, both PIP2-binding site and patch showed a similar dose response to PIP2 as gauged by the similar degree of line broadening for these regions (Fig. 8a, gray bars). This suggests that PIP2-binding site and patch act in concert and that lipid interactions in the PIP2-binding site are also sensed by the autoinhibitory patch.

Fig. 8. The conserved N-terminal patch modulates lipid binding to the IDR.

a, b, c Chemical shift perturbation of 15N-labeled a IDR, b IDRAAWAA, and c IDRPatch titrated with short-chain PIP2. Mutated regions are indicated in gray boxes, chemical shift changes are depicted by colored spheres, residues showing line broadening are highlighted by gray bars. d Average number of membrane contacts for each residue of the native IDR (dark gray), the IDRAAWAA mutant (light gray) and the IDRPatch mutant (mauve) on a lipid bilayer composed of POPC (69%), CHOL (20%), DOPS (10%), PIP2 (1%) (Supplementary Table 4). The location of the N-terminal patch and the PIP2-binding site (PBS) are highlighted by gray boxes. In the upper panel, contacts for all lipids, in lower panel, only contacts with PIP2 are shown. Four replicate simulations per IDR sequence were carried out for 38 µs and contact averages were calculated from the last ~28 µs of each simulation. e 31P NMR spectra of diC8-PIP2 (light blue) with increasing amounts of IDR, IDRΔN97 or IDRPatch. Chemical shift changes are indicated by arrows. f Chemical shift perturbations of P4 and P5 lipid headgroup resonances upon addition of IDR (gray), IDRΔN97 (blue), or IDRPatch (mauve). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For IDRAAWAA, dampened spectral responses to PIP2 were observed in the mutated PIP2-binding site, large parts of the central IDR and, to a much lesser degree, in the patch region (Fig. 8b) suggesting reduced coupling between these regions when the PIP2-binding site is mutated. Likewise, in MD simulations of IDRAAWAA, PIP2 binding was largely abrogated in the mutated PIP2-binding site (Fig. 8d, Supplementary Fig. 12c). Consequently, the mutated PIP2-binding site frequently lost and regained contact with the lipid bilayer, although other IDR regions remained attached to the membrane throughout the simulations.

Mutation of the patch did not alter the lipid interaction pattern with the central IDR and PIP2-binding site per se as gauged by NMR spectroscopy and MD simulations (Fig. 8c, d, Supplementary Figs. 8b, c, 9e, and 12c). Since the severe line broadening in the 1H, 15N-NMR IDR spectra precluded a more detailed analysis, we also took advantage of the PIP2 headgroup phosphate groups as a 31P NMR reporter (Fig. 8e). In agreement with the liposome sedimentation assay (Fig. 7), both the deletion (IDRΔN97) or mutation of the patch (IDRPatch) mutation increased PIP2 binding compared to the native IDR as gauged by the extent of the respective 31P chemical shifts (Fig. 8f). Thus, the N-terminal patch seems to compete with PIP2 lipids for the PIP2- binding site via transient protein-protein interactions, thereby suppressing channel activity.

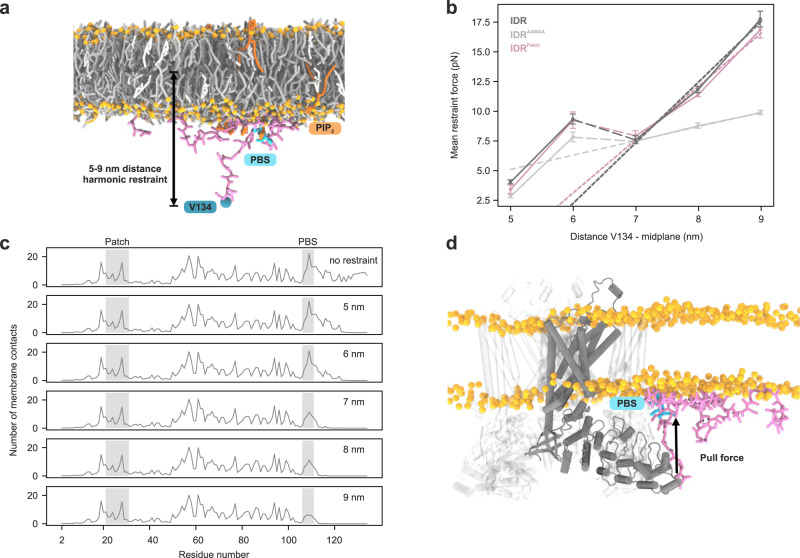

Membrane-bound PIP2-binding site exerts a pull force on the ARD

It remains unclear how lipid binding to the IDR is transduced to the structured core of TRPV4 to modulate the conductive properties of the channel. We speculated that IDR-lipid interactions could alter the channel gating properties by exerting a pull-force on the ARD. To probe this, we carried out coarse-grained MD simulations, in which the IDR’s C-terminal residue (V134) was kept at distances of 5-9 nm below the membrane to emulate the distance constraints enforced on an ARD-anchored IDR in a full-length channel (Fig. 9a). From the mean restraint forces for native IDR, IDRAAWAA and IDRPatch, we determined force-displacement curves as function of the height of V134 over the membrane center (Fig. 9b).

Fig. 9. PIP2 binding to the TRPV4 IDR’s PIP2-binding site exerts a pulling force on the ARD.

a Coarse-grained MD simulation system setup using a lipid bilayer membrane consisting of PIP2 (1%, dark orange) as well as POPC (69%, dark gray), DOPS (10%, light gray) and cholesterol (20%, white). Headgroup phosphates are shown as orange spheres), the IDR (pink liquorice) was kept at defined distances from the membrane midplane by its most C-terminal residue V134 (blue sphere) to emulate anchoring by the ARD. The PIP2-binding site (PBS) is highlighted in cyan. b Force displacement curves from restrained simulations of TRPV4 IDR, IDRAAWAA and IDRPatch. Four 38 µs replicate simulations were carried out for each condition. The mean restraint force is plotted against the mean distance between residue V134 and the membrane midplane. Dotted lines show linear fits of the force contribution of the PIP2-binding site. Averages were calculated from the last ~28 µs of each of the 4 replicate simulations per IDR genotype and per height restraint. Error bars show the standard errors of the mean (SEM) of the replicate simulations. c Number of membrane lipid contacts for each residue of the native IDR at a given height restraint (for results with IDRAAWAA and IDRPatch, see Supplementary Fig. 10c). Averages are calculated from the last 28 µs of each of the four replicate simulations. d Composite figure of a structure of the native IDR (from an MD simulation at a restraint distance of 7 nm) and an AlphaFold94 model of the transmembrane core of the G. gallus TRPV4 tetramer. The force displacement curves in b indicate that the interaction of the PIP2-binding site with the membrane exerts a pull force on the ARD N-terminus (solid arrow). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

At heights <6.5 nm, the force on the C-terminal end of the IDR probes the membrane interaction of basic residues C-terminal of the PIP2-binding site. Consequently, all constructs experienced similar forces. At a height of ~6.5 nm, the residues C-terminal of the PIP2-binding site detached from the membrane in all IDR constructs. Thus, forces at heights ≥7 nm are generated by the PIP2-binding site pulling at the membrane. Importantly, the PIP2-binding site remained membrane-bound over the entire height regime in the simulations with native IDR and IDRPatch. In contrast, these interactions were lost in the IDRAAWAA mutant, resulting in greatly reduced pull forces ( ~ 10 versus ~17.5 pN at 9 nm) (Fig. 9b, c). Furthermore, the reduced slope of the near-linear force-height curve beyond 6.5 nm implies a four-fold higher effective force constant acting on the IDR C-terminus with an intact PIP2-binding site compared to IDRAAWAA. We also noticed a slightly lower slope and weaker forces for IDRPatch compared to the native IDR.

The forces observed here for an IDR C-terminus linked to a membrane-bound PIP2-binding site are in the regime reported for other biochemical processes45,46. However, the smoothened energy landscape in our coarse-grained simulations may underestimate the actual force exerted on the ARD by its membrane-bound IDR “anchor”. The strength of the PIP2-binding site interaction with the membrane also became apparent when constraining the IDR C-terminus at heights >8 nm. Here, rather than detaching, the pull of the PIP2-binding site led to noticeable membrane deformations (Supplementary Fig. 12a). TRPV4 may thus not only be able to sense, but under certain conditions also directly affect its membrane microenvironment via its IDR.

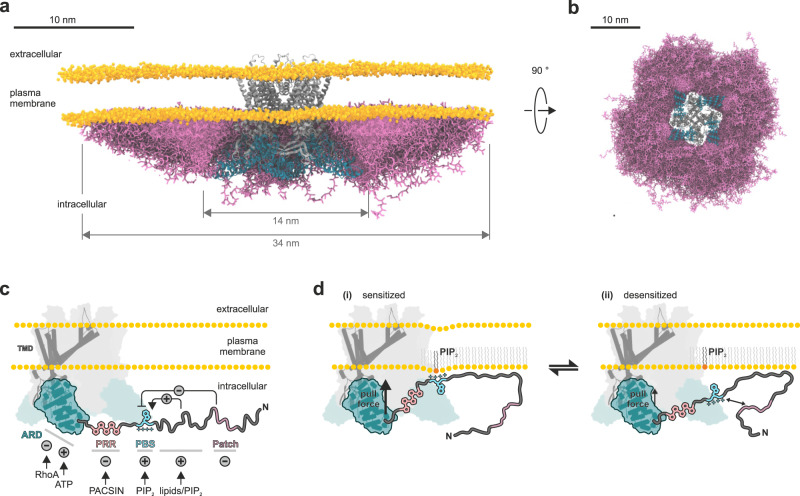

The cytosolic TRPV4 N-terminal ‘belt’ more than doubles channel dimensions beyond the structured ion channel core

Structural information for TRP channel IDRs is incomplete at best since they are not amenable to X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy studies due to their inherent spatiotemporal flexibility4. We previously calculated the dimensions theoretically sampled by TRPV channel IDRs assuming they behaved as unrestrained worm-like chains and found that fully expanded IDRs may contribute an additional 5–7 nm end-to-end distance to the structured cytosolic domains4. Here, we combined the results from SAXS, NMR and MD simulations to derive an experimentally-informed structural model of the TRPV4 ion channel. We found that the cytosolic “belt” formed by the TRPV4 N-terminal IDRs is smaller than previously anticipated due to the extensive lipid and intradomain interactions of the IDR. Nonetheless, the N-terminal IDRs more than double the TRPV4 diameter along the membrane plane from approximately 140 Å to a maximum of ~340 Å (Fig. 10a, b, Fig S13, Supplementary Movies 2 and 3). With their IDRs, these proteins thus dramatically extend their reach and may act as multivalent cellular recruitments hubs.

Fig. 10. The TRPV4 IDR forms an extensive ‘belt’ along the membrane plane and encodes a hierarchy of antagonistic regulatory modules.

a, b Superimposed IDR conformations from coarse-grained MD simulations (pink licorice) integrated into a full-length TRPV4 tetramer (AlphaFold94 prediction of G. gallus TRPV4 transmembrane core (gray) and ARDs (cyan)) viewed from the side a and from the intracellular side b. For better visualization of the extent of the IDR ‘belt’, the IDR conformations of the front facing TRPV4 monomer have been deleted. For a view of the IDR conformations on a single TRPV4 subunit, see Supplementary Fig. 13 as well as Supplementary Movies 2 and 3. c The TRPV4 N-terminus encodes multiple antagonistic regulatory elements that regulate TRPV4 function through ligand, protein, lipid or intra-domain contacts. d PIP2-binding site interactions with the membrane exert a pull force on the IDR C-terminus. Likewise, pulling on the IDR can lead to membrane deformation. Crosstalk between the PIP2-binding site and the autoinhibitory patch modulates PIP2 binding and thus IDR membrane interactions, thereby influencing channel activity.

Discussion

In this study, we show that the TRPV4 N-terminal IDR encodes a network of transiently coupled regulatory elements that engage in hierarchical long-range crosstalk and can enhance or suppress TRPV4 activity (Fig. 10c). Such contacts may affect lipid binding as seen here, but presumably can also be modulated by other ligands47, regulatory proteins29–32,47 or post-translational modifications48 within the ARD and IDR to enable a fine-tuned integration of multi-parameter inputs by TRPV4.

While the PIP2-binding site is crucial for channel activity33,44, we observed that N-terminal IDR deletion mutants retaining the PIP2-binding are still inactive if they do not also include the central IDR (Fig. 5i). Accordingly, this region may function in two ways: by enriching PIP2 in the channel vicinity and by increasing the IDR’s residency time at the plasma membrane. Furthermore, we discovered an autoinhibitory patch that suppresses channel activity by acting on the PIP2-binding site.

Structural studies on TRPV channels have found that the ARDs can undergo concerted motions in response to ligand binding that may be connected to channel activity24, with an unclear role of the IDR. Lipid interactions in the IDR are important regulators of TRPV4 activity33,44, and here we find them to depend on intradomain interactions within the TRPV4 N-terminus (Figs. 7 and 8). Our MD simulations suggest that lipid-binding of the IDR at the PIP2-binding site exerts a pull-force on the ARD, which itself is sufficiently rigid to further transduce mechanical forces to the TRPV4 core. The ARD is connected to the PIP2-binding site via a proline-rich region which forms a poly-proline helix29. The proline-rich region may thus be a relatively stiff connector to efficiently transduce pull forces between ARD and membrane-bound PIP2-binding site as suggested by our MD simulations (Fig. 9). Our NMR experiments show that the proline-rich region is not affected by lipids itself (Figs. 7d and 8a). However, it binds the channel desensitizer PACSIN329,30,32, which may affect the interaction between membrane-bound IDR and the structured channel core. Likewise, the N-terminal autoinhibitory patch may reduce the pull force exerted by the PIP2-binding site by competing with its ability to bind lipids and thus effectively dampen channel activity. Our data thus provide a mechanistic explanation for prior observations that TRPV4 variants lacking part of the distal N-terminus display osmotic hypersensitivity28,49. Furthermore, a conformational equilibrium between PIP2-binding site interaction between membrane and autoinhibitory patch may allow TRPV4 to fine-tune channel responses depending on cell state and regulatory partners (Fig. 10d).

In summary, to understand TRP channel function, their often extensive IDRs cannot be ignored. Our work shows that “IDR cartography”, i.e., mapping structural and functional properties onto distinct IDR regions through an integrated structural biology approach, can shed light on the complex regulation of a membrane receptor through its hitherto mostly neglected regions.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Roth and VWR unless otherwise stated. Reagents used include HC067047 (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0143), GSK1016790A (Sigma-Aldrich, G0798), AlexaFluor 555 Phalloidin (ThermoFisher Scientific), 15N NH4Cl and 13C6-glucose (Eurisotop). DSS-H12/D12 for crosslinking was obtained from Creative Molecules Inc. Lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids and Cayman Chemicals. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-GFP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11122), rabbit anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, 4967) and HRP-conjugated monoclonal mouse anti-rabbit IgG, light chain specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 211-032-171). Both antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000.

Computational tools

Freely available computational tools were used to investigate the properties of N-terminal TRPV4 constructs. Sequence conservation was determined with ConSurf50 (Figs. 5, 6 and S11). Overall charge (z) of IDR deletion constructs was determined with ProtPi (www.protpi.ch) (Fig. 5). Charge distribution z for N-terminal deletion constructs was determined with www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/charge (Fig. 5). Gel densitometry analysis was carried out with ImageJ51 (Fig. 7b). The IDR charge gradient in Fig. 7c was plotted with the PepCalc tool (https://pepcalc.com/).

Cloning, expression and purification of recombinant proteins

The DNA sequences encoding for the G. gallus TRPV4 N-terminal domain was cloned into a pET11a vector with an N-terminal His6SUMO-tag, as described previously29. Human TRPV4 constructs in a pcDNA3.1 vector were commercially obtained from GenScript. Expression plasmids encoding for the isolated intrinsically disordered region (IDR), the isolated ankyrin repeat domain (ARD), N-terminal truncations (NTDΔN54, NTDΔN97, NTDΔN104, and NTDΔN120) and a peptide comprising residues 97–134 of the IDR (IDRD97) were obtained from the NTD encoding vectors using a Gibson Deletion protocol52. Site-directed mutagenesis of the PIP2-binding site (107KRWRR111 to 107AAWAA111, forward primer GTGAAAACGCAGCCTGGGCCGCGCGTGTGGTTGAAAAACCAGTGG; reverse primer CACACGCGCGGCCCAGGCTGCGTTTTCACCACCAATCTGT) and regulatory patch (19FPLSSLANLFE29 to 19FP(AG)5E29, forward primer GATGACTCCTTCCCGGCCGGCGCGGGCGCCGGCGCGGGTGCGGGTGAGGACACCCCGTCT; reverse primer CGGGAAGGAGTCATCCCCCAGCACGTCCCC) were introduced in the abovementioned constructs by site-directed mutagenesis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

TRPV4 N-terminal constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21-Gold(DE3) (Agilent Technologies) grown in terrific broth (TB) medium (or LB medium for IDRΔN97) supplemented with 0.04% (w/v) glucose and 0.1 mg/mL ampicillin. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 for induction with 0.5 mM IPTG (final concentration) and then further grown at 37 °C for 3 h. 15N, 13C-labeled proteins were prepared by growing cells in M9 minimal medium53 with 15N-HN4Cl and 13C-glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources. Cells were grown at 37 °C under vigorous shaking to an OD600 of 0.4, moved to RT, grown to OD600 of 0.8 for induction of protein expression with 0.15 mM IPTG (final concentration) and then grown overnight at 20 °C. After harvest by centrifugation, cells were stored at −80 °C until further use.

All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C. Cell pellets were dissolved in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8, 20 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM PMSF, lysozyme, DNAse, RNAse and protease inhibitor (Sigmafast)) and lysed (Branson Sonifier 250). Debris was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant applied to a Ni-NTA gravity flow column (Qiagen). After washing (20 mM Tris pH 8, 20 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl), proteins were eluted with 500 mM imidazole. Protein containing fractions were dialyzed overnight (20 mM Tris pH 7 (pH 8 for IDRΔN97), 300 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF) in the presence of Ulp-1 protease in a molar ratio of 20:1 to yield the native TRPV4 N-terminal constructs. After dialysis, cleaved proteins were separated by a reverse Ni-NTA affinity chromatography step and subsequently purified via a HiLoad prep grade 16/60 Superdex200 or 16/60 Superdex75 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. Pure sample fractions were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20 °C until further use.

Purified IDRΔN97 was extensively dialyzed against double distilled water, lyophilized, and stored in solid form at −20 °C. Peptides could be dissolved in desired amounts of buffer to concentrations up to 10 mM.

Western blot

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 6% CO2. For Western blots, HEK293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX with Plus Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), lysed 24 h after transfection in RIPA Buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, Millipore Sigma) supplemented with Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were then removed and Laemmli sample buffer with β-mercaptoethanol was added. Protein lysates were heated for 10 min at 70 °C and resolved on 4–15% TGX gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and then transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were developed using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 system (GE Healthcare).

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

Analytical SEC experiments were carried out at 4 °C using an NGC Quest (BioRad) chromatography system. A total of 250 μL protein at a concentration of 2–3 mg/mL was injected on a Superdex200 10/300 increase column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT via a 1 mL loop. Protein was detected by absorbance measurement at wavelengths of 230 and 280 nm.

For Stokes radius (RS) determination, SEC columns were calibrated with a protein standard kit (GE Healthcare) containing ferritin (MW = 440 kDa, RS = 61.0 nm), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa, 45.0 nm), conalbumin (75 kDa, 36.4 nm), ovalbumin (43 kDa, 30.5 nm), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa, 23.0 nm), ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa, 16.4 nm), and aprotinin (6.5 kDa, 13.5 nm) whose Stokes radii were obtained from La Verde et al.54 The SEC elution volume, Ve (in mL), of the protein standards was plotted versus the logRS, with RS in nm, and fitted with a linear regression (Eq. 1):

| 1 |

where m is the slope of the linear regression and b the y-axis section. Equation 1 was then used to calculate the Stokes radii of the TRPV4 constructs from their respective SEC elution volumes.

Size-exclusion chromatography multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS)

Multi-angle light scattering coupled with size-exclusion chromatography (SEC-MALS) of the G. gallus TRPV4 NTD, ARD, and IDR was performed with a GE Superdex200 Increase 10/300 column run at 0.5 mL/min on a Jasco HPLC unit (Jasco Labor und Datentechnik) connected to a light scattering detector measuring at three angles (miniDAWN TREOS, Wyatt Technology). The column was equilibrated for at least 16 hrs with 20 mM Tris pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT (filtered through 0.1 μm pore size VVLP filters (Millipore)) before 200 μL of protein samples at a concentration of 2 mg/mL were loaded. The ASTRA 7 software package (Wyatt Technology) was used for data analysis, assuming a Zimm model55. The molecular weight, MW, can be determined from the reduced Rayleigh ratio extrapolated to zero, R(0), which is the light intensity scattered from the analyte relative to the intensity of the incident beam (Eq. 2):

| 2 |

Here, c is the concentration of the analyte and (dn/dc) is the refractive index increment, which was set to 0.185 mL/g, a standard value for proteins56. K is an optical constant depending on wavelength and the solvent refractive index. The protein extinction coefficients at 280 nm were calculated from the respective amino acid sequences using the ProtParam tool57.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CD measurements were carried out on a Jasco-815 CD spectrometer (JascoTM) with 1 mm quartz cuvettes (Hellma Macro Cell). Proteins were used at concentrations in the range of 0.03–0.05 mg/mL in 5 mM Tris pH7, 10 mM NaCl. Spectra were recorded at 20 °C between 190 and 260 nm with 1 nm scanning intervals, 5 nm bandwidth and 50 nm/min scanning speed. All spectra were obtained from the automatic averaging of three measurements with automatic baseline correction. The measured ellipticity θ in degrees (deg) was converted to the mean residue ellipticity (MRE) via Eq. 358.

| 3 |

Here, MREλ is the mean residue ellipticity, and θλ is the measured ellipticity at wavelength λ, d is the pathlength (in cm), and c is the protein concentration (g/mL). MRW is the mean residue weight, , where MW is the molecular weight of the protein (in Da), and N is the number of residues. For titration experiments, TRPV4 N-terminal peptides were used in a concentration of 30 μM in double distilled water in the presence of TFE (2,2,2-trifluoroethanol, 0–90% (v/v)), SDS (0.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 and 8.0 mM) and liposomes (0.5 and 1.0 mM). Liposomes were prepared from POPG and POPC at a molar ratio of 1:1 as described below.

Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

SAXS experiments were carried out at the EMBL-P12 bioSAXS beam line, DESY59. SEC-SAXS data collection60, I(q) vs q, where ; 2q is the scattering angle and λ the X-ray wavelength (0.124 nm; 10 keV) was performed at 20 °C using S75 (IDR constructs) and S200 Increase 5/150 (NTD and ARD constructs) analytical SEC columns (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in the appropriate buffers (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) at flow rates of 0.3 mL/min. Automated sample injection and data collection were controlled using the BECQUEREL beam line control software61. The SAXS intensities were measured as a continuous series of 0.25 s individual X-ray exposures, from the continuously-flowing column eluent, using a Pilatus 6 M 2D-area detector for a total of one column volume (ca. 600–3000 frames in total). The 2D-to-1D data reduction, i.e., radial averaging of the data to produce 1D I(q) vs q profiles, were performed using the SASFLOW pipeline incorporating RADAVER from the ATSAS 2.8 suite of software tools62. The individual frames obtained for each SEC-SAXS run were processed using CHROMIXS63. Briefly, individual SAXS data frames were selected across the respective sample SEC-elution peaks and an appropriate region of the elution profile, corresponding to SAXS data measured from the solute-free buffer, were identified, averaged, and then subtracted to generate individual background-subtracted sample data frames. These data frames underwent further CHROMIXS analysis, including the assessment of the radius of gyration (Rg) of each individual sample frame, scaling of frames with equivalent Rg, and subsequent averaging to produce the final 1D-reduced and background-corrected scattering profiles. Only those scaled individual SAXS data frames with a consistent Rg through the SEC-elution peak that were also evaluated as statistically similar through the measured q-range were used to generate the final SAXS profiles. Corresponding UV traces were not measured; the column eluate was flowed directly to the P12 sample exposure unit after the small column, forging UV absorption measurements, to minimize unwanted band-broadening of the sample. All SAXS data-data comparisons and data-model fits were assessed using the reduced χ2 test and the Correlation Map, or CorMap, p value64. Fits within the χ2 range of 0.9–1.1 or having a CORMAP p values higher than the significance threshold cutoff of a = 0.01 are considered excellent, i.e., no systematic differences are present between the data-data or data-model fits at the significance threshold.

Primary SAXS data analysis was performed using PRIMUS within ATSAS 3.0.165. The Guinier approximation66 (lnI(q) vs. q2 for qRg < 1.3) and the real-space pair distance distribution function, or p(r) profile (calculated from the indirect inverse Fourier transformation of the data, thus also yielding estimates of the maximum particle dimension, Dmax, Porod volume, Vp, shape classification, and concentration-independent molecular weight67–69 were used to estimate the Rg and the forward scattering at zero angle, I(0). Dimensionless Kratky plot representations of the SAXS data (qRg2(I(q)/I(0)) vs. qRg) followed an approach previously described70. All collected SAXS data are reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Ensemble modeling

The ensemble analysis of IDR, NTD, the systematic NTD IDR-deletions and/or respective IDR/NTD-PIP2-binding site mutants was performed using Ensemble Optimization Method, EOM37,38. Briefly, 10,000 protein structures were generated for each of the respective protein constructs, where the IDR section(s) were modeled as random chains (self-avoiding walks with the confines of Ramachandran-constraints). The scattering profiles were calculated for each model within the initially generated 10,000 member ensembles. The selection of sub-ensembles describing the SAXS data, and the assessment of the Rg distribution of the refined ensemble pools, was performed using a genetic algorithm based on fitting the SAXS data with a combinatorial volume-fraction weighted sum contribution of individual model scattering profiles drawn from the initial pool of structures.

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS)

HDX-MS was conducted on three independent preparations of G. gallus TRPV4 IDR, ARD or NTD protein each, and for each of those three technical replicates (individual HDX reactions) per deuteration timepoint were measured. Preparation of samples for HDX-MS was aided by a two-arm robotic autosampler (LEAP Technologies). HDX reactions were initiated by 10-fold dilution of pre-dispensed protein sample (25 µM) with buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7, 300 mM NaCl) prepared in D2O and incubated for 10, 30, 100, 1000 or 10,000 s at 25 °C. The exchange was stopped by mixing with an equal volume of pre-dispensed quench buffer (400 mM KH2PO4/H3PO4, 2 M guanidine-HCl; pH 2.2) kept at 1 °C, and 100 μL of the resulting mixture injected into an ACQUITY UPLC M-Class System with HDX Technology71. Non-deuterated samples were generated by a similar procedure through 10-fold dilution in buffer prepared with H2O. The injected HDX samples were washed out of the injection loop (50 μL) with water + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid at a flow rate of 100 μL/min and guided over a column containing immobilized porcine pepsin kept at 12 °C. The resulting peptic peptides were collected on a trap column (2 mm × 2 cm), that was filled with POROS 20 R2 material (Thermo Scientific) and kept at 0.5 °C. After three minutes, the trap column was placed in line with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 1.7 μm 1.0 × 100 mm column (Waters) and the peptides eluted with a gradient of water + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (eluent A) and acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (eluent B) at 60 μL/min flow rate as follows: 0–7 min/95–65% A, 7-8 min/65-15% A, 8-10 min/15% A. Eluting peptides were guided to a Synapt G2-Si mass spectrometer (Waters) and ionized by electrospray ionization (capillary temperature and spray voltage of 250 °C and 3.0 kV, respectively). Mass spectra were acquired with the software MassLynx MS version 4.1 (Waters) over a range of 50 to 2000 m/z in enhanced high definition MS (HDMSE)72,73 or high definition MS (HDMS) mode for non-deuterated and deuterated samples, respectively. Lock mass correction was conducted with [Glu1]-Fibrinopeptide B standard (Waters). During separation of the peptides on the ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column, the pepsin column was washed three times by injecting 80 μL of 0.5 M guanidine hydrochloride in 4% (v/v) acetonitrile. Blank runs (injection of double-distilled water instead of the sample) were performed between each sample. All measurements were carried out in triplicates. Peptides were identified and evaluated for their deuterium incorporation with the software ProteinLynx Global SERVER 3.0.1 (PLGS) and DynamX 3.0 (both Waters). Peptides were identified with PLGS from the non-deuterated samples acquired with HDMSE employing low energy, elevated energy and intensity thresholds of 300, 100, and 1000 counts, respectively and matched using a database containing the amino acid sequences of IDR, ARD, NTD, porcine pepsin and their reversed sequences with search parameters as follows: Peptide tolerance = automatic; fragment tolerance = automatic; min fragment ion matches per peptide = 1; min fragment ion matches per protein = 7; min peptide matches per protein = 3; maximum hits to return = 20; maximum protein mass = 250,000; primary digest reagent = non-specific; missed cleavages = 0; false discovery rate = 100. For quantification of deuterium incorporation with DynamX, peptides had to fulfill the following criteria: Identification in at least 2 of the 3 non-deuterated samples; the minimum intensity of 10,000 counts; maximum length of 30 amino acids; minimum number of products of two; maximum mass error of 25 ppm; retention time tolerance of 0.5 min. All spectra were manually inspected and omitted, if necessary, e.g., in case of low signal-to-noise ratio or the presence of overlapping peptides disallowing the correct assignment of the isotopic clusters.

Residue-specific deuterium uptake from peptides identified in the HDX-MS experiments was calculated with the software DynamX 3.0 (Waters). In the case that any residue is covered by a single peptide, the residue-specific deuterium uptake is equal to that of the whole peptide. In the case of overlapping peptides for any given residue, the residue-specific deuterium uptake is determined by the shortest peptide covering that residue. Where multiple peptides are of the shortest length, the peptide with the residue closest to the peptide C-terminus is utilized. Assignment of residues being intrinsically disordered was based on two criteria, i.e., a residue-specific deuterium uptake of >50% after 10 s of HDX and no further increment in HDX > 5% in between consecutive HDX times. Raw data of deuterium uptake by the identified peptides and residue-specific HDX are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS)

For structural analysis, 100 μg of purified protein were crosslinked by addition of DSS-H12/D12 (Creative Molecules) at a ratio of 1.5 nmol/1 µg protein and gentle shaking for 2 h at 4 °C. The reaction was performed at a protein concentration of 1 mg/mL in 20 mM HEPES pH 7, 300 mM NaCl. After quenching by addition of ammonium bicarbonate (AB) to a final concentration of 50 mM, samples were dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Then, proteins were denatured by resuspension in 8 M urea, reduced with 2.5 mM Tris(2-carboxylethyl)-phosphine (TCEP) at 37 °C for 30 min and alkylated with 5 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. After dilution to 1 M urea using 50 mM AB, 2 µg trypsin (protein:enzyme ratio 50:1; Promega) were added and proteins were digested at 37 °C for 18 h. The resulting peptides were desalted by C18 Sep-Pak cartridges (Waters), then crosslinked peptides were enriched by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 20 Increase 3.2/300, cytiva) prior to liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS analysis on an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific)74. MS measurement was performed in data-dependent mode with a cycle time of 3 s. The full scan was acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 120,000, a scan range of 400–1500 m/z, AGC Target 2.0e5 and an injection time of 50 ms. Monoisotopic precursor selection and dynamic exclusion for 30 s were enabled. Precursor ions with charge states of 3-8 and minimum intensity of 5e3 were selected for fragmentation by CID using 35% activation energy. MS2 was done in the Ion Trap in rapid scan range mode, AGC target 1.0e4 and a dynamic injection time. All experiments were performed in biological triplicates and samples were measured in technical duplicates. Crosslink analysis was done with the xQuest/xProphet pipeline75 in ion-tag mode with a precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm. For matching of fragment ions, tolerances of 0.2 Da for common ions and 0.3 Da for crosslinked ions were applied. Crosslinks were only considered for further analyses if they were identified in at least 2 of 3 biological replicates with deltaS <0.95 and at least one Id score ≥ 25.

Lipid preparation

Liposomes were prepared from 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG) mixed in a 1:1 (n/n) ratio in chloroform. The organic solvent was removed via nitrogen flux and under vacuum via desiccation overnight. The lipid cake was suspended in 1 mL buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl or 300 mM NaCl) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C and briefly spun down before being subjected to five freeze and thaw cycles. The resulting large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were incubated for 20 min at 21 °C under mild shaking. To obtain a homogeneous solution of small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs), the mixture was extruded 15 times through a 100 nm membrane using the Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). This yielded a liposome stock solution of 100 nm liposomes with 4.0 mM lipid in 10 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl that was used immediately for measurements. POPC-only liposomes were prepared similarly.

Commercial stocks containing 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (diC8-PC) and 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (diC8-PG) were prepared by first removing the organic solvent via nitrogen flux and under vacuum via desiccation overnight. Afterwards, the lipids were dissolved in the appropriate amount of buffer to yield 10 mM lipid stocks. 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-myo-inositol-4′,5′-bisphosphate) (diC8-PI(4,5)P2) was purchased as a powder and directly dissolved in the appropriate amount of buffer.

Liposome sedimentation assay

Liposomes were prepared as described above. Proteins and liposomes in 20 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl were mixed to a final concentration of 2.5 μM protein and 2 mg/mL lipid. After incubation at 4 °C for 1 h under mild shaking, an SDS-PAGE sample of the input was taken. The mixture was then centrifuged at 70,000 g for 1 h at 4 °C. SDS-PAGE samples (15 μL) were taken from both the supernatant and the pellet resuspended in assay buffer. Control samples without liposomes were run in parallel to verify the protein stability under the experimental conditions. The protein distribution between the pellet and supernatant fractions was determined by running an SDS-PAGE and densitometrically analyzing the bands using imageJ51. Sedimentation assays were carried out three times for each protein liposome mixture and protein only control sample. Error bars were calculated as the standard deviation from the mean value of three replicates.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

Backbone assignments of native 13C, 15N-labeled G. gallus IDR have been reported by us previously5. For complete backbone assignments of IDRAAWAA and IDRPatch, 15N, 13C-labeled proteins were prepared. Backbone and side chain chemical shift resonances were assigned with a set of band-selective excitation short-transient (BEST) transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)-based assignment experiments: HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB. Additional side chain chemical shift information was obtained from H(CCCO)NH and (H)CC(CO)NH experiments.

For titrations with lipids, or comparison of chemical shifts between constructs, 15N-labeled IDR and NTD variants were prepared. All NMR spectra were recorded at 10 °C on 600 MHz to 950 MHz Bruker AvanceIII HD NMR spectrometer systems equipped with cryogenic triple resonance probes. For peptide and lipid titration experiments, a standard [1H,15N]-BEST-TROSY pulse sequence implemented in the Bruker Topspin pulse program library was used. Solutions with 100 μM of 15N-labeled IDR constructs in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7, 100 mM (or 300 mM) NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) D2O were titrated with lipid from a concentrated stock solution. The chemical shifts were determined using TopSpin 3.6 (Bruker) The 1H and 15N weighted chemical shift differences observed in [1H, 15N]-HSQC spectra were calculated according to Eq. 476:

| 4 |

Here, ΔδH is the 1H chemical shift difference, ΔδN is the 15N chemical shift difference, and Δδ is the 1H and 15N weighted chemical shift difference in ppm.

For NMR titrations of 15N-labeled TRPV4 IDR with liposomes (SUVs) where line broadening instead of peak shifts was observed, the interaction of the reporter with liposomes was quantified using the peak signal loss in response to liposome titration. The signal loss at a lipid concentration ci was calculated as the relative peak signal decrease rel. ΔI according to Eq. 5.

| 5 |

Here, I0 is the peak integral in the absence of SUVs, and Ii is the peak integral in the presence of a lipid concentration ci.

31P{1H} NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a 600 MHz Bruker AvanceIII HD NMR spectrometer. DiC8-PI(4,5)P2 was used at 500 μM in 10 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) D2O and titrated with protein from a concentrated stock solution.

Standard NMR pulse sequences implemented in Bruker Topspin library were employed to obtain R1, R2 and 15N,{1H}-NOE values. Longitudinal and transverse 15 N relaxation rates (R1 and R2) of the 15N-1H bond vectors of backbone amide groups were extracted from signal intensities (I) by a single exponential fit according to Eq. 6:

| 6 |

In R1 relaxation experiments, the variable relaxation delay t was set to 1000 ms, 20 ms, 1500 ms, 60 ms, 3000 ms, 100 ms, 800 ms, 200 ms, 40 ms, 400 ms, 80 ms, and 600 ms. In all R2 relaxation experiments, the variable loop count was set to 36, 15, 2, 12, 4, 22, 8, 28, 6, 10, 1, and 18. The length of one loop count was 16.96 ms. The variable relaxation delay t in R2 experiments is calculated by length of one loop count times the number of loop counts. The inter-scan delay for the R1 and R2 experiments was set to 3 s. The {1H}−15N steady-state nuclear Overhauser effect measurements ({1H},15N-NOE) were obtained from separate 2D 1H-15N spectra acquired with and without continuous 1H saturation, respectively. The {1H},15N-NOE values were determined by taking the ratio of peak volumes from the two spectra, {1H},15N-NOE = Isat/I0, where Isat and I0 are the peak intensities with and without 1H saturation. The saturation period was approximately 5/R1 of the amide protons.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

All tryptophan fluorescence measurements were carried out in 10 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl buffer on a Fluro Max-4 fluorimeter with an excitation wavelength of 280 nm and a detection range between 300 nm and 550 nm. The fluorescence wavelength was determined as the intensity-weighted fluorescence wavelength between 320 and 380 nm (hereafter referred to as the average fluorescence wavelength) according to Eq. 6:

| 6 |

Here, <λ> is the average fluorescence wavelength and Ii is the fluorescence intensity at wavelength λi.

To monitor liposome binding by tryptophan fluorescence, fluorescence emission spectra were recorded in the presence of increasing lipid concentrations. Lipids were prepared as SUVs with 100 nm diameters as described above. The protein concentrations were kept constant at 5 μM. The protein-liposome mixtures were incubated for 10 min prior to recording the emission spectra. For each sample, at least three technical replicates were measured. The tryptophan fluorescence wavelength at each lipid concentration was quantified by determining the average fluorescence wavelength using Eq. (6). The dissociation constants, Kd, of the protein liposome complexes were determined by plotting the changes in against the lipid concentration c and fitting the data with a Langmuir binding isotherm (Eq. (7)):

| 7 |

Here, Δ<λ> describes the wavelength shift between the spectrum in the absence of lipids and a given titration step at a lipid concentration c. Δ<λ>max indicates the maximum wavelength shift in the saturation regime of the binding curve. Under the assumption that proteins cannot diffuse through liposome membranes and therefore can only bind to the outer leaflet, the lipid concentration c was set to half of the titrated lipid concentration.

Calcium imaging

MN-1 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged TRPV4 plasmids using Lipofectamine LTX with Plus Reagent. Calcium imaging was performed 24 h after transfection on a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 inverted microscope equipped with a Lambda DG-4 (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA) wavelength switcher. Cells were bath-loaded with Fura-2 AM (8 μM, Life Technologies) for 45–60 min at 37 °C in calcium-imaging buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). For hypotonic saline treatment, one volume of NaCl-free calcium-imaging buffer was added to one volume of standard calcium-imaging buffer for a final NaCl concentration of 70 mM. For GSK101 treatment, GSK101 was added directly to the calcium imaging buffer to achieve 50 nM final concentration. Cells were imaged every 10 s for 20 s prior to stimulation with hypotonic saline or GSK101, and then imaged every 10 s for an additional 2 min. Calcium levels at each time point were computed by determining the ratio of Fura-2 AM emission at 340 nm divided by the emission at 380 nm. Data were expressed as raw Fura ratio minus background Fura ratio.