Abstract

COVID-19 propelled anti-Asian racism around the world; although empirical research has yet to examine the phenomenology of racial trauma affecting Asian communities. In our mixed-methods study of 215 Asian participants of 15 ethnicities, we examined experiences of racism during COVID and resulting psychological sequelae. Through qualitative content analysis, themes emerged of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes resulting from these racialized perpetrations, including internalizing emotions of fear, sadness, and shame; negative alterations in cognitions, such as reduced trust and self-worth; and behavioral isolation, avoidance, and hypervigilance, in addition to positive coping actions of commitment to racial equity initiatives. We engaged in data triangulation with quantitative Mann-Whitney U tests and found that individuals who experienced COVID discrimination had significantly higher racial trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder scores compared with individuals who did not. Our convergent findings provide clinicians with novel ways to assess the ongoing impact of racial trauma and implement appropriate interventions for clients.

Keywords: discrimination, Asian Americans, COVID-19, race-based traumatic stress, mixed-methods design

The arc of the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in late December 2019 and persisting more than 2.5 to 3 years later, propelled a wave of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia around the world. Anti-Asian rhetoric, including from powerful leaders such as former U.S. President Trump, who repeatedly called the coronavirus “Kung Flu” and “Chinese virus” (Trump, 2020), fueled anti-Asian sentiment, leading to a rise in harrassment and discrimination against Asians in the United States (Gover et al., 2020). Significant increases in rates of Asian-targeted hate crimes have been well documented, with a 149% surge in 2020 and a 339% surge from 2020 to 2021 despite overall crimes dropping by 7% during this time period (California State University, San Bernardino, 2021). Reported hate crimes include online and in-person verbal harassment (Croucher et al., 2020; Lu & Wang, 2022), vandalization of Asian-owned businesses, physical assaults by strangers in public, and racially motivated killings of Asian Americans (Brito, 2021; Hwang & Parreñas, 2021; Peng, 2020; “Teens Arrested,” 2020). Physical assaults of Asian elders walking in their neighborhoods have gained increasing national public attention (Burke & Romero, 2021; Chung & Li, 2021), as have several racially motivated attempted and completed murders (Hwang & Parreñas, 2021; Lenthang, 2022; Margolin, 2020; Taylor, 2022; U.S. Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, 2022; Yam, 2022).

Although the increasing frequency and ubiquity of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate has been well documented (AP3CON, 2020; Asian Americans Advancing Justice, 2020) and the need and calls for research have been ringing (Cheng, 2020; Misra et al., 2020), empirical research that examines the psychological impact of the sharp increase in anti-AAPI racism is only recently emerging (Yang et al., 2021). Such research showed that COVID-19-related discrimination is associated with higher endorsement of depression and anxiety symptoms (Chae et al., 2021; Cheah et al., 2021; Inman et al., 2021; Lu & Wang, 2022; Pan et al., 2021; Woo & Jun, 2022; Wu et al., 2020), social isolation (Ahn et al., 2022), and physical symptoms and sleep problems (Lee & Waters, 2021). One study looked at COVID-19-related discrimination in the first few months of the pandemic and found that these events were associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Hahm et al., 2021) as measured by the PTSD Symptom Checklist 5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., 2015). Although emerging research has examined the association between anti-AAPI racism and a range of mental- and physical-health symptoms, no literature to date has examined the incidence of race-based stress and trauma, a phenomenon distinct from the previously reported-on mental-health outcomes, among AAPI populations during COVID.

Race-based stress and trauma, defined as psychological distress resulting from repeated exposures to negative race-based encounters, includes symptoms of reexperiencing the events, avoidance of trauma reminders, worsening cognitions and mood, and hypervigilance and hyperarousal (Carlson et al., 2018; Nadal, 2018; M. T. Williams et al., 2021). Negative race-based experiences can include interpersonal and institutional/systemic encounters and span a spectrum of physicality, ranging from microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007) to physical assaults. Existing literature posits that race-based stress and trauma symptoms (also known as race-based “traumatic stress” and “racial trauma,” among other names) share phenomenology with PTSD, although it is not entirely synonymous with PTSD (R. T. Carter, 2007). For example, PTSD is currently defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychological Association, 2013) as requiring a single-incident “Criterion A” trauma. But some scholars have argued for racism to “count” as Criterion A (e.g., Holmes et al., 2016), citing evidence that many instances of racialized traumas may not meet the current Criterion A threshold but lead to symptoms commonly seen in PTSD (Nadal, 2018). Others have highlighted the unique chronicity and ongoing perpetrations of racism as distinct from single-incident traumas upon which current conceptualizations of PTSD are predicated (e.g., Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005). Thus, these traditionally Eurocentric conceptualizations are the basis for empirically supported PTSD treatments such as prolonged exposure (Foa & Rothbaum, 2001) and cognitive-processing therapy (Resick et al., 2016), which both involve repeated reference and exposure to singular traumatic event and are typically appropriate only once the trauma survivor has exited the traumatic situation. However, because people of color continue to live in a world in which racist institutions, culture, and encounters are ubiquitous, it is unknown whether these “gold-standard” PTSD treatments are well suited for treating racial trauma. Concurrently, it is also possible that diagnostic suggestions such as complex PTSD (Herman, 1992) and persisting or continuous traumatic stress disorder (Eagle & Kaminer, 2013), which both describe living in contexts of prolonged, repeated trauma and realistic current and ongoing danger, may contribute to ongoing research and discourse on racial-trauma-related diagnoses.

Although phenomenological understanding of race-based stress and trauma continues to evolve, its presence has been well documented as an experience in many non-White racial groups and non-Christian religious groups (Ford & Sharif, 2020) in response to ongoing racism and discrimination. For instance, a study in Black Americans found that higher frequencies of racial discrimination were associated with more PTSD and depressive symptoms (Mekawi et al., 2022). Researchers looking at the trauma within indigenous communities have found that experiencing historical loss led to negative affective responses such as anxiety, depression, anger, and avoidance (Whitbeck et al., 2004). After the 9/11 attacks, a majority of Muslim men and women from New York reported various forms of race-based stress, from experiences of vicarious racism to verbal/physical attacks, leading to participants “feeling unsafe” and subsequent experiencing of traumatic symptoms (Abu-Ras & Suarez, 2009). Race-based stress in Asian-identified individuals in response to COVID-related experiences of racism, however, has yet to be empirically examined.

We set out to fill this gap in the literature by exploring the experiences of racism and race-based stress in Asian-identified individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic using a mixed-methods approach. To thoroughly describe the complexity and nuances of such emerging phenomenon, it is imperative to allow participants to share their lived experiences and subsequent impact in their own words, qualitatively (Davidsen, 2013; Neubauer et al., 2019). Qualitative research can provide rich descriptions of phenomena that add context and meaning to validated measures. Concurrently, we used psychometrically validated measures to assess participants’ reports of PTSD, racial-trauma symptoms, racial microaggressions experienced, and other mental-health symptoms related to COVID discrimination to measure race-based stress and related symptoms in a such a way that may be comparable across other studies. Importantly, no study to our knowledge has assessed racial trauma among Asian samples using a psychometrically validated measure. In summary, we used a convergent, parallel, mixed-methods design, collecting qualitative and quantitative data concurrently, analyzing independently, and integrating the results during interpretation (Creswell & Clark, 2017), which allows for data triangulation and a richer understanding of the problem than either approach alone (N. Carter et al., 2014).

Transparency and Openness

We report how we determined our measures and data exclusions. All study procedures received University of San Francisco institutional review board approval (Protocol 1445). All quantitative data, materials, and code are available at https://osf.io/f7bcp/?view_only=299a9bfeaa5242f1a45b950bf133f635.

Method

Participants and data collection

Participant inclusion criteria were (a) age 18 or older, (b) identifying as Asian (including multiracial and multiethnic Asian), and (c) living in the United States. A total of 215 participants (age: M = 24.99 years, SD = 10.41) who identified as Asian and living in the United States were recruited in two waves. The first wave of participants comprised 70 college students recruited through advertisements in a West Coast university subject pool who completed the study between September and December 2020 for course credit. The second wave was a convenience sample (n = 145) recruited through online advertisements in Asian interest groups in January 2021; and these participants were compensated with a $15 Amazon gift card. Study procedures involved completing an online consent form outlining the overview, voluntary nature, purpose, risks, benefits, and confidentiality of the study, followed by a 1-hr online Qualtrics survey of quantitative scales and qualitative open-ended free-response questions. Qualitative-survey data collection has been shown to provide value accounts of people’s experiences and perspectives and is capable of generating data that are “more focused and ‘on target’” (Braun et al., 2021). In addition, this method of data collection allows for more flexibility in geographical reach and may increase participant willingness to disclose information on sensitive topics (Braun et al., 2021), both of which apply to our study.

Participants identified as Asian/Asian American (90.7%) and mixed-race Asian (9.3%). About a third of participants self-identified as Chinese (33.0%), followed by multiethnic (13.5%), Filipino/a/x (12.1%), Korean (9.3%), Taiwanese (7.9%), Vietnamese (7.4%), Japanese (4.7%), and Asian American (3.7%). Seven other ethnic identifications comprised the remaining 8.5% (details in Table 1). More than half identified as female (68.3%), 27.9% identified as male, and 3.8% identified as nonbinary, genderqueer, or another self-reported gender identification. Most participants were U.S. nationals (89.5%), and 10.5% self-described as international students or non-U.S. individuals living in America. The majority of participants were in college (34.3% first year, 9.7% second year, 7.2% third year, 5.8% fourth year, and 30.9% fifth year), 11.1% were in graduate/professional school, and 1% were not in school. Participants also reported where they resided for the majority of 2020: 56.9% were located on the West Coast, 15.3% were located on the East Coast, 12.9% were located in the Midwest, 6.2% were located in the Southern states, 4.3% in United States nonmainland, and 4.3% were located outside the United States.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Sample

| Demographic Factor | N | Valid % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 215 | 24.99 | 10.41 | |

| Gender Female Male Nonbinary, genderqueer, other |

208 |

68.3 27.9 3.8 |

||

| Monoracial/multiracial Asian Mixed-Asian |

215 |

90.7 9.3 |

||

| Nationality U.S. Non-U.S. |

209 |

89.5 10.5 |

||

| International student Yes No |

209 |

8.6 91.4 |

||

| Educational level Not in college First year Second year Third year Fourth year Fifth year or graduate student Graduate or professional school Other |

207 |

0.5 34.3 9.7 7.2 5.8 30.9 11.1 0.5 |

||

| Geographic location (in past 6 months) U.S. West Coast U.S. Midwest U.S. Southern states U.S. East Coast U.S. nonmainland (e.g., islands, Hawaii, Alaska) Outside U.S. |

209 |

56.9 12.9 6.2 15.3 4.3 4.3 |

||

| Self-described ethnicity Asian American Cantonese Chinese Filipino/a Hmong Indian Japanese Korean Punjabi Singaporean Sri Lankan Taiwanese Vietnamese Multiethnic Other |

215 |

3.7 0.5 33 12.1 0.9 2.3 4.7 9.3 0.5 0.5 0.5 7.9 7.4 13.5 3.3 |

Note: % = adjusted percentage of sample who endorsed the answer.

Mixed methods

Qualitative measures

Participants were asked to provide a yes/no response to, “After the coronavirus pandemic, which started in December of 2019, did you experience discrimination due to your race/ethnicity?” Participants who endorsed yes were then asked the following questions, each presented on a separate page: “Please describe your experiences”; “How frequently did these experiences happen?”; and “Please describe how these experiences impacted you in the short and long term.” The qualitative responses were aggregated into a 155-page document of all 215 transcripts; the mean number of words in each response was 143.6 (SD = 95.8).

Quantitative measures

Demographics

A demographic questionnaire was used to assess participants’ age, racial/ethnic identities, education, gender, international-student status, nationality, and geographic location in 2020.

Racial microaggressions

The 45-item Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS; Nadal, 2011) was used to assess the frequency that participants experienced racial microaggressions in the past 6 months. Sample items include, “Someone told me that all people in my racial group look alike” and “Someone assumed that I spoke a language other than English.” Items were ranked on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (I did not experience this event) to 5 (five or more times in the past 6 months). Scores were averaged to obtain the global REMS score. The scale has shown excellent reliability in previous research (Nadal et al., 2015). In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = .93).

Asian American racial microaggressions

Thirty-six items from the 41-item Asian American Racial Microaggressions Scale (AARMS; Lin, 2011) were used to assess the frequency participants experienced racial microaggressions that specifically targeted their Asian American identity. Sample items include, “You were given the message that you were not American enough” and “You were given the message that Asians are poor with using words.” Items were ranked on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (this has never happened to you) to 6 (this has happened to you almost all of the time). Scores were averaged to obtain the global AARMS score. The scale has shown high reliability and validity in previous research (Lin, 2011). In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = .96).

Racial trauma

The 21-item Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale (TSDS; M. T. Williams et al., 2018) was used to assess the frequency that participants experienced posttraumatic symptoms as a result of faced discrimination. Sample items include, “Due to past experiences of discrimination, I often feel nervous, anxious, or on edge, especially around certain people” and “Due to past experiences of discrimination, I feel isolated and set apart from others.” Items were ranked on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Item scores were summed to obtain the global TSDS score and subscales (uncontrollable distress and hyperarousal, alienation from others, worry about safety and the future, and being keyed up and on guard). The scale has shown excellent reliability in previous research (M. T. Williams et al., 2018), although this measure has not yet been used with an Asian sample. In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = .96).

Posttraumatic symptoms

The 20-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., 2015) was used to assess the severity of posttraumatic symptoms participants experienced in the past month. A sample item is, “In the past month, how much were you bothered by repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience?” Items were ranked on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). All scores of 20 items were summed to obtain the global PCL-5 score, where a score of 31 to 33 indicates probable PTSD. The scale has shown excellent reliability and validity in previous research (Blevins et al., 2015). In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = .97).

Qualitative-data analysis

We used conventional qualitative content analysis (QCA; Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) to examine participants’ described experiences of discrimination during COVID. QCA prescribes a systematic method to allow researchers to subjectively interpret the content of text data, deriving coding categories directly from participants’ narratives. We were also informed by consensual qualitative research (Hill & Knox, 2021) to engage in further “checks and balances” in which coders reflexively discussed biases throughout the research process and consensually agreed on the analytic procedures (Subramani, 2019). The qualitative-research team consisted of three female-identified researchers who were Asian and Asian American of Taiwanese, Chinese, and Vietnamese backgrounds. One member is an assistant professor of psychology on the U.S. West Coast, another is an international doctoral student in the southcentral region of the United States, and the third member is a researcher at a nonprofit health-care-research organization on the U.S. East Coast. Our external auditor identified as Asian American and is a clinical psychologist and an assistant professor of psychiatry at a U.S. West Coast university.

For the preparation stage, each coding-team member began by immersing into the raw data through reading and rereading the entirety of the text transcript. Then, each team member independently engaged in open coding to develop preliminary codes. Using Microsoft Word and the commenting function, each team member worked on “condensation” (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017), the process of shortening text while preserving core meaning, by highlighting every instance of distinct phenomena or meaning unit present in the transcript and annotating each meaning unit “in the margins” using the comments function. In addition to condensation, each annotation also included a “code,” which is a label or name usually one or two words long that describes almost exactly what the condensed meaning unit is about.

The team convened to discuss all the codes observed by each member and created a preliminary codebook that aggregated all the codes. As an exercise to increase familiarity with the codebook, we set out to establish initial reliability whereby all three coders coded six random transcripts and reviewed coding together until an interrater reliability (McAlister et al., 2017) of 80% between coders on 95% of the codes was achieved (as recommended by Miles & Huberman, 1994; calculated by the following formula: reliability = number of agreements / [number of agreements + disagreements]) before moving forward with actual coding. However, because the research team is aware of the controversy in qualitative research regarding “reliability” and its association with quantitative and positivist paradigms (Guba & Lincoln, 1994; O’Connor & Joffe, 2020), we chose to pursue “trustworthiness” (Clark & Braun, 2013) during our formal qualitative coding, using extensive dialogue to reflexively improve coding choices and interpretations and examine data triangulation.

Upon initiating the qualitative-coding stage, the research team worked both independently and collaboratively to code raw data; every participant’s text data were coded by at least two researchers independently (double coding) before group discussion. Coding pairs met weekly to review each week’s coded transcripts, discrepancies were highlighted using comments in a different color in Microsoft Word, team members each explained independent rationale for code assignment, and extensive discussion ensued to understand and resolve differences, as standard in QCA (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). Note that fewer than 10% of codes were discrepant, and decisions on a handful of code assignments were deferred for discussion with the full team when resolution was not achieved within the double-coding pair. There were no discrepancies that could not be resolved by discussion with the full team.

When all final codes were assigned to the transcripts, they were organized into categories that grouped together codes related to each other in content or context. On occasion, when codes were describing different aspects that belonged together about a text’s content (e.g., similarities or differences), we used subcategories as well.

After this process, we worked on extracting themes of underlying meaning found in two or more categories by asking questions such as “Why?”; “How?”; “In what way?”; and “By what means?” We explored latent ideas under the manifest categories to capture the underlying meaning of the categories.

We also engaged an external auditor to review our codebook (Nadal et al., 2015), code several transcripts for additional trustworthiness, and offer an outside perspective to counter possible groupthink. This auditor is an experienced qualitative researcher with subject matter expertise in discrimination, trauma, and Asian American health. She provided feedback to the team, confirming that the condensation, coding, and thematic analyses were appropriate. This additional step increased credibility and contributed to minimizing bias in the investigation.

Quantitative analysis

For quantitative analyses, data from participants were first divided into two groups on the basis of their experience of discrimination during COVID. Participants were asked to indicate whether they experienced discrimination because of their race/ethnicity during the coronavirus pandemic that started in December 2019. Sixty participants (33.71%) answered yes to this question, and 118 (66.29%) answered no. For simplicity, in this article, these groups are referred to as the “discrimination” and the “no-discrimination” groups, respectively. Differences in REMS, AARMS, TSDS, and PCL-5 global scores between these two groups were examined in the study. Relevant mental-health-subscale scores (e.g., distress and hyperarousal on the TSDS and Criterion B: intrusion symptoms on the PCL-5) were also examined to further reflect the differences in specific trauma symptoms between the two groups. Statistically, we hypothesized that participants in the discrimination group would score significantly higher on both global scales and subscales across measures of racial trauma and probable PTSD symptoms than participants in the no-discrimination group.

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (Version 25.0). Data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances. Results from the Levene’s and Shapiro-Wilk tests revealed inequality of variances and nonnormal distributions for all dependent variables of interest. Thus, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests of significance were used in the main analyses to compare discriminatory experiences and trauma symptoms of the two groups.

Results

Qualitative results

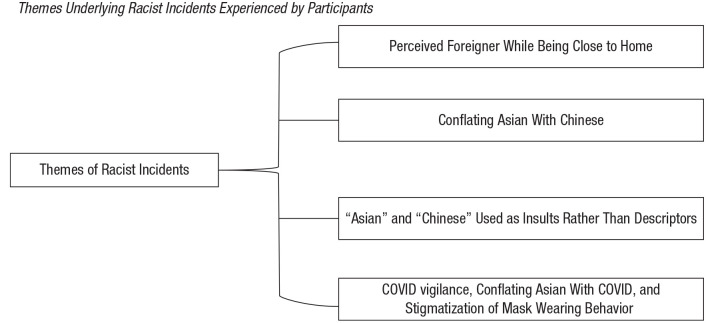

Through phenomenological analysis, several themes (see Fig. 1) emerged on the types of incidents participants experienced; the cognitions, emotions, and behaviors experienced during the incidents; and ensuing impact that participants observed. We have included information on participants’ gender and ethnic self-identification, where they were living during 2020 (and where the perpetrations were experienced), and age grouped in categories (e.g., 18–19 year old; early-mid-late 20s, 30s, 40s, etc.) to balance between preserving anonymity while also contextualizing and describing our participants’ voices (Corden & Sainsbury, 2006).

Fig. 1.

Themes underlying racist incidents experienced by participants.

Themes underlying racist incidents experienced by participants

Perceived foreigner while being close to home

Our respondents highlighted the indignation of perpetrations happening near their homes, where they had lived and been rooted for a long time. Participants repeatedly heard phrases such as “go back to your country” or “go back to China” despite being home, resulting in experiences such as, “I felt like a terrorist in my own hometown. . . . I felt like I wasn’t safe in my hometown because of [my] ethnicity” (18/19-year-old Filipinx American nonbinary person; San Francisco, [SF] CA).

Some participants reported feeling threatened while on their own property: “A neighbor came up to my dad in front of our house asking him to stop grilling food and proceeded to ask if he was Chinese” (early 20s Chinese American woman; SF and Los Angeles [LA], CA).

Conflating Asian with Chinese

Participants felt a resurgence of their Asian identity being conflated with being Chinese from China. Examples include, “A man in NYC told his friends not to get ‘too close’ to my friends (who were all Asian American) and me because ‘who knows if [we’d] been to China recently’” (early 20s Chinese American woman; SF and LA, CA) and “One person just came straight up to me and said, are you Chinese? No hi, no nothing” (late-30s Japanese American woman; Ames, IA). An 18/19-year-old Filipina American woman living in Sacramento, CA, concluded, “The racism and xenophobia also became unruly and terrifying because they didn’t care who you were or what [Asian] ethnicity you were.”

The words “Asian” and “Chinese” being used as insults rather than descriptors

Participants observed a novel phenomenon that emerged during COVID in which “Asian” and “Chinese” were used to imply insults against them; for example, an 18/19-year-old Filipinx-Chinese American nonbinary person living in Modesto, CA, heard, “Move, stupid Asian” while walking in their neighborhood. Likewise, an early 20s Chinese American woman (Kansas City and St. Louis, MO) reported, “I was walking at a local park and a jogger ran by and shouted, ‘f*ing Chinese b*’ before sprinting away.”

COVID vigilance, conflating Asian with COVID, and stigmatization of mask wearing

Participants noticed that others had more COVID vigilance when around them and other Asians in public. An early 30s Taiwanese American woman living in Seattle, WA, described, “People would cover their mouths as I walked by (this was before masks were recommended and cases were reported in the US).”

Participants noticed the associations “Asians equal COVID spreaders” or “Asians equal COVID virus” that seemed to be levied on them ubiquitously. One participant (late-40s Asian American woman; Philadelphia, PA, and Atlantic City, NJ) recounted, “My poor kids were teased in school. [Other kids] would walk by them and cover their mouths acting like my kids are the virus walking by them.” Participants also reported worrying about coughing, sneezing, and blowing their noses in public. For example, an 18/19-year old Filipinx-American nonbinary person living in SF, CA, reported, “I was so self-conscious with my body language, making sure not to touch my face or even cough in the slightest so as to not start something in a public area.”

Many participants described anxiety about wearing masks because of receiving unsolicited commentary or judgment, for example, “People have come up to me in Sam’s Club telling me that masks won’t help me” (late-30s Japanese American woman; Ames, IA) and “In March [2020], I was at an emergency care conference in Boston for a week and wore a mask, people there weren’t yet doing that and were rude about my mask and assumed I had COVID if wearing it” (early 20s Japanese-Brazilian American woman; SF, CA). Likewise, an 18/19-year-old Hong Kong Taiwanese American nonbinary person living in Chicago, IL, reported, “Every time I go outside with a mask to simply take a walk, everyone stares at me and stands in front of their children like I’m a monster.”

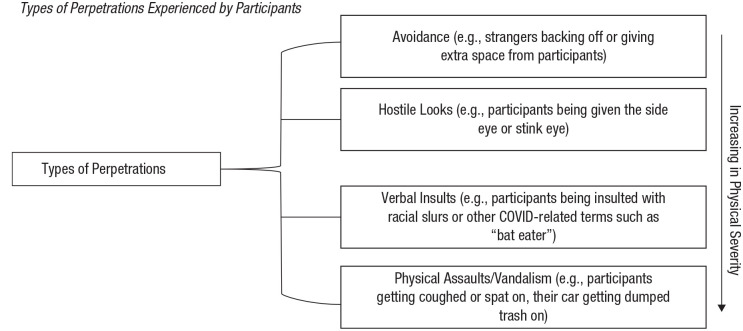

Types of perpetrations

Participants described perpetrations ranging in physicality from avoidance, looks, and verbal comments to explicit physical actions such as getting coughed on or property being vandalized (see Fig. 2). Examples of avoidance by others include when more than 6 ft of clearance were given to participants or when strangers appeared to go out of their way to put extra space between them and participants, for example, “Workers in stores ringing me up first to get me out of the store faster” (late-20s Korean American woman; Sterling Heights, Troy, and Madison Heights, MI). Likewise, “In early 2020, I was flying back to my home state and a couple in the airport made the comment that they hoped they didn’t have to sit by me because they didn’t want to get the ‘Chinese virus’” (mid-40s Korean American woman; Phoenix, AZ).

Fig. 2.

Types of perpetrations experienced by participants.

Following avoidance, participants also routinely described being targets of “side eye,” staring, and other looks. For example, “I noticed the people around me giving me the stink eye or looking at me very weird” (early 20s Filipina American woman; SF, CA, and Honolulu, HI); “I came into a store and all the workers all stared at me. I was the only Asian in the store and there had been other people around but they all kept glancing at me. It was very unusual” (late-30s Japanese American woman; Ames, IA); and

I got stared down A LOT in public spaces. I am used to the hypersexualized gaze, but these looks were of contempt and anger. In one instance a white woman followed me around Target just staring me down (she wasn’t shopping or putting anything in her cart) until I stared HER down and asked if she had a f*ing problem or if I needed to call security. (mid-30s Chinese-Thai American woman; Arlington, VA)

Perpetrations that extended beyond avoidance and looks included being given commands to back up or keep distance, unsolicited commentary from strangers using the terms “Kung Flu” and “Chinese virus,” being connected to bats, verbal insults with attributions of blame, and verbal assaults of racial slurs such as “ch*nk” and “chingchong.” For example, “On about 3 separate occasions either walking around different neighborhoods in SF or in grocery stores, I was asked by someone to move aside despite being masked and well over 6-feet away from folks. They asked in disgust and fear” (early 20s Japanese-American woman; SF and LA, CA), and a Chinese-Mexican American man in his early 20s living in Naperville, IL, and St. Louis, MO, said, “I’ve been called a bat eater on social media.” Likewise, another participant described, “There were many, many times when people would say things like ‘go back to China and take the virus with you’ or ‘you are the cause of this virus’ or ‘ching chong-ding dong go home’” (mid-40s Korean American woman; Phoenix, AZ).

Participants also reported getting spit on or coughed on in public, with perpetrators explicitly evoking wanting to transmit COVID to them. An early 20s Indonesian American woman living in San Ramon and Oakland, CA, reported that a man spit on her and said, “I hope you have it now.” Some participants also reported on their property being destroyed; for example, an early 30s Chinese American woman living in Hartford, CT, and Charlottesville, VA, found “a white female stranger dumping garbage on my car windshield.”

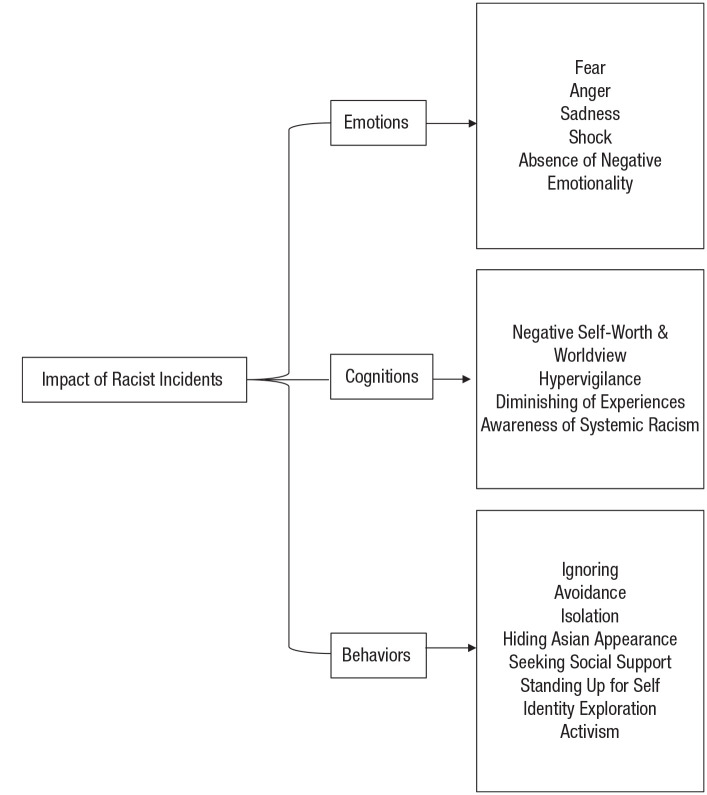

Cognitive-behavioral impact of racist incidents

Emotions experienced by participants

Participants reported a range of negative internalizing emotions related to experiencing the incidents (see Fig. 3). For example, participants extensively described feeling fear-related emotions, including anxiety, stress, worry, and fear for their safety: “I started to fear going outside as I was getting discriminated against for just standing outside” (18/19-year-old Filipinx American nonbinary person; SF, CA) and “For many months after quarantine began, I was scared to go outside” (mid-20s Chinese American nonbinary person; New Orleans, LA).

Fig. 3.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) model of impact of racist incidents on participants.

They also reported ensuing anger, including irritation, frustration, and annoyance:

I was very frustrated and irritated and angry because people were ignorant and didn’t do their research at all and just took it out on my community. It was very irritating that people made fun of what we ate and how it’s a part of our culture and our norm. It was also very disrespectful and it angered me. (18/19-year-old Chinese American woman living in Elk Grove, CA)

Participants reported feeling sadness and hurt (including depressed and defeated). Some also reported observing guilt, shame, regret, and self-blame. For example, “It was upsetting because I do my job to help people but now I was seen as a walking public health threat” (early 20s Japanese-Brazilian American woman; SF, CA) and “[I] regret not saying anything” (mid 30s Vietnamese American woman living in Garden Grove, Brea, and Laguna Hills, CA).

Others reported surprise or shock. A late-20s Korean-Filipina American woman living in Seattle, WA, described, “I was only hearing/seeing racism during the pandemic on social media, and have not really experienced discrimination in Seattle, so I was surprised that it happened to me . . . it was very unsettling being vulnerable on that empty street.”

Some participants noticed the absence of negative emotionality, for example, feeling glad that others gave them extra space and distanced themselves, which they experienced as additionally protective against COVID, and several others reported noticing no impact or not caring. For example, a Korean American woman in her late 20s living in Sterling Heights, Troy, and Madison Heights, MI, described “due to the pandemic and the nature of the virus, I was kind of grateful for people steering clear of me.”

Cognitions experienced by participants

Participants reported a range of thoughts in response to experiencing racist perpetrations. Negative alterations in cognitions about themselves and the world were common; for example, they described negative self-worth, “I think on a subconscious level it’s made me more self-conscious/ashamed of my identity” (early 20s Chinese-American woman; SF and LA, CA), and negative worldview: “I think in the long term it has made me more distrustful of people outside my ethnic group” (early 20s Chinese-Mexican American man; Naperville, IL, and St. Louis, MO).

Some participants described these incidents as confirming their existing negative worldview, such as, “Because I for the most part knew that these experiences would happen I wasn’t as much shocked, but it was still sad” (18/19-year-old Chinese-Indonesian woman; SF, CA).

Others, particularly women, reported awareness of increasing hypervigilance as they found themselves more on edge. For example, “I felt unsafe, targeted, and unwelcome in social groups. Felt like an outcast especially in a big city such as SF. Very careful and uneasy taking public transit such as BART or bus” (18/19-year-old Chinese American woman; Alameda and SF, CA), and, “It’s made me more cautious and made me to feel like I have to be more aware of my surroundings, mistrusting of strangers” (late-20s Korean-American woman; New York, NY). An 18/19-year-old Filipina American woman living in Sacramento, CA, reported, “Simply going out living my day to day made me feel like I was in a great danger because of all the violence I’ve seen towards Asians on media.”

Other participants described having the intention to de-escalate while they were experiencing perpetrations. A Japanese American woman in her early 20s living in LA and SF, CA, said, “I also never retaliated or responded to these events as they occurred. I simply walked away. I left all of these situations, however, feeling extremely angry and disgusted by these people.”

Some also diminished their experiences, for example, “I did not care much for it because I assumed that I experienced these things due to the coronavirus. I always justified experiences like this with the virus because of extra precaution” (early 20s Filipina-American woman; SF and San Diego, CA), or, “My friends make jokes about it, but none of them are actually being racist” (18/19-year-old Chinese man; Kansas).

Some reported being aware that things could have been worse, for example, “[The racist incidents] were annoying but in the moment, I mostly felt grateful there was no physical harm because I know it’s been a lot worse for many others” (late-20s Chinese American woman; Houston, TX). Some participants also described increasing in awareness of systemic racism and observing more empathy toward the oppression of other people of color through these incidents, for example, “They have definitely grown more tense and the discrimination I experience now is more frequent and makes me more anxious to go outside period. It will never be on the same level of other BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] but it has definitely increased” (18/19-year-old Hong Kong-Taiwanese American nonbinary person; Chicago, IL). Likewise, a Japanese American woman in her early 20s living in LA and SF, CA, explained, “I am grateful that nothing further transpired during these interactions and definitely feel much greater sympathy for Black and Brown folks who undergo such acts of racism frequently in this country.”

Actions taken by participants

Participants responded to the racist incidents with a range of behaviors, including ignoring: “In these experiences we just ignored it. We just chose not to go back to those stores again” (18/19-year-old Chinese American man; SF and Vallejo, CA). Some also noted avoiding engaging in many daily life activities that were previously common, for example, “I had just started going on more jogs in the park, and I noticed that those jogs have significantly decreased since the incident [of racism]” (mid-30s Chinese-American woman; Seattle, WA); “I stopped walking my dog alone in my own neighborhood” (early 30s Taiwanese-American woman; Seattle, WA); and, “My family and I switched entirely to grocery delivery so that we wouldn’t have to go grocery shop in public. I live in an area with Trump signs everywhere. I didn’t want to get harassed because of how I look” (mid-20s Chinese-American nonbinary person; New Orleans, LA).

Participants also extended the ignoring and avoiding to isolating at home often, reporting, “I feel scared for my family going outside due to violence against Asians” (18/19-year-old Chinese American woman; St. Louis, MO, and Lexington, KY).

Some participants attempted to reduce the visual salience of being Asian by codeswitching language, putting on a “disguise,” or going out with non-Asian individuals as an ally for safety. For example, “When I go out in public, I try to minimize my appearance (wearing a hat, mask, sunglasses) so that it’s not as easy to identify that I am Asian” (mid-40s Korean American woman; Phoenix, AZ) and, “This just left me a bad impression on this country as a whole and makes me afraid to go out without my boyfriend (he’s white)” (early 20s Indonesian-Chinese American; San Ramon and Oakland, CA).

Importantly, many participants observed engaging in positive active-coping actions such as standing up for themselves, relying on their social-support networks, embarking on Asian-identity exploration to feel more connected to community, and participating in anti-racism activism and other social-justice initiatives. For example, “I was more prone to correct people if they said negative things about Asian people and became more interested in speaking Chinese and watching Chinese television” (early 30s Taiwanese-American woman; Seattle, WA) and, “[I] have committed to spending time to create a POC startup (with two other Asian women), while taking a leadership role in my Korean American organizing work in the Bay” (mid-30s Korean American man; SF, CA).

Quantitative results

Descriptive statistics of microaggressions and trauma symptoms are presented in Table 2. In addition, results from the Mann-Whitney tests (see Tables 3 and 4) confirmed participants’ experiences of discrimination. Specifically, the discrimination group scored significantly higher on the REMS than did the no-discrimination group (U = 1,758.5, p < .001). Likewise, the discrimination group also scored significantly higher on the AARMS than did the no-discrimination group (U = 1,773.0, p < .001). These results showed that participants who indicated experiencing discrimination during COVID-19 faced both general and Asian-specific racial microaggressions more frequently than participants who did not.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Microaggressions and Trauma Symptoms

| Measures and subscales | Participants who experienced discrimination (n = 60) |

Participants who did not (n = 118) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Racial/Ethnic Microaggressions Scale | 1.56 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.41 |

| Assumptions of inferiority | 0.52 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.46 |

| Second-class citizen and assumptions of criminality | 1.15 | 1.01 | 0.24 | 0.53 |

| Microinvalidations | 1.52 | 1.44 | 0.57 | 0.78 |

| Exoticization/assumptions of similarity | 1.60 | 1.36 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Workplace and school microaggressions | 0.90 | 1.25 | 0.18 | 0.47 |

| Asian American Racial Microaggression Scale | 3.16 | 1.02 | 2.27 | 0.76 |

| Asian inferior status | 2.82 | 1.00 | 1.95 | 0.68 |

| Assumption of model minority | 4.09 | 1.41 | 3.16 | 1.33 |

| Alien in own land | 3.33 | 1.21 | 2.46 | 0.96 |

| Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale a | 51.19 | 15.08 | 38.31 | 12.59 |

| Uncontrollable distress and hyperarousal | 19.53 | 7.55 | 14.42 | 5.07 |

| Alienation from others | 13.44 | 3.63 | 9.87 | 3.78 |

| Worry about safety and the future | 12.76 | 3.60 | 10.31 | 3.28 |

| Being keyed up and on guard | 5.47 | 1.71 | 3.74 | 1.51 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (PCL-5) a | 29.78 | 22.56 | 17.21 | 15.61 |

| Criterion B: intrusion symptoms | 6.93 | 5.88 | 3.39 | 4.00 |

| Criterion C: avoidance | 3.12 | 2.66 | 1.92 | 2.02 |

| Criterion D: negative alterations in cognitions and mood | 9.37 | 7.49 | 5.72 | 5.04 |

| Criterion E: alterations in arousal and reactivity | 8.83 | 6.79 | 5.25 | 4.85 |

Note: PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

Scale is scored by summing all item scores (instead of taking an average).

Table 3.

Comparison of Discriminatory Experiences and Trauma Symptom Global Scores Between Participants Who Did and Did Not Experience Discrimination During COVID-19

| Variable | COVID discrimination group | Mean rank | Mann-Whitney U | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial/ethnic microaggressions | Yes | 119.19 | 1,758.5 | −5.483 | < .001 |

| No | 74.40 | ||||

| Asian American racial microaggression | Yes | 118.95 | 1,773.0 | −5.438 | < .001 |

| No | 74.53 | ||||

| Racial trauma | Yes | 119.09 | 1,885.5 | −5.338 | < .001 |

| No | 75.48 | ||||

| Probable posttraumatic stress disorder | Yes | 108.42 | 2,405.0 | −3.494 | < .001 |

| No | 79.88 |

Table 4.

Comparison of Discriminatory Experiences and Trauma Symptom Subscale Scores Between Participants Who Did and Did Not Experience Discrimination During COVID-19

| Subscale | COVID discrimination group | Mean rank | Mann-Whitney U | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian American racial microaggression (AARMS) | |||||

| Asian inferior status | Yes | 120.63 | 1,672.50 | −5.749 | < .001 |

| No | 73.67 | ||||

| Assumption of model minority | Yes | 111.67 | 2,210.00 | −4.097 | < .001 |

| No | 78.23 | ||||

| Alien in own land | Yes | 114.73 | 2,026.00 | −4.661 | < .001 |

| No | 76.67 | ||||

| Racial trauma (TSDS) | |||||

| Uncontrollable distress and hyperarousal | Yes | 114.86 | 2,147.50 | −4.559 | < .001 |

| No | 77.70 | ||||

| Alienation from others | Yes | 120.05 | 1,826.00 | −5.533 | < .001 |

| No | 74.97 | ||||

| Worry about safety and the future | Yes | 113.17 | 2,252.50 | −4.251 | < .001 |

| No | 78.59 | ||||

| Being keyed up and on guard | Yes | 121.55 | 1,671.00 | −6.037 | < .001 |

| No | 73.28 | ||||

| Probable PTSD (PCL-5) | |||||

| Criterion B: intrusion symptoms | Yes | 110.57 | 2,276.00 | −3.937 | < .001 |

| No | 78.79 | ||||

| Criterion C: avoidance | Yes | 103.41 | 2,645.50 | −2.755 | .006 |

| No | 81.61 | ||||

| Criterion D: negative | Yes | 105.28 | 2,593.50 | −2.917 | .004 |

| alterations in cognitions and mood | No | 81.48 | |||

| Criterion E: alterations | Yes | 107.27 | 2,474.00 | −3.292 | .001 |

| in arousal and reactivity | No | 80.47 | |||

Note: AARMS = Asian American Racial Microaggressions Scale; TSDS = Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

In terms of psychological impact, experiences of discrimination during the pandemic were linked to racial-trauma symptoms. Specifically, participants in the discrimination group scored significantly higher on the TSDS global scale than did participants in the no-discrimination group (U = 1,885.5, p < .001). This significant difference was reflected across all TSDS subscales, including symptoms of uncontrollable distress and hyperarousal (U = 2,147.5, p < .001), alienation from others (U = 1,826.0, p < .001), worry about safety about to the future (U = 2,252.5, p < .001), and being keyed up and on guard (U = 1,671.0, p < .001). Results indicated that participants who faced discrimination during COVID-19 experienced race-based stress symptoms as a result. Because research on TSDS is just emerging, there are no clinical norms or cutoffs for comparison available yet.

Furthermore, participants in the discrimination group also scored significantly higher on the PCL-5 global score than did the no-discrimination group (U = 2,405.0, p < .001). In terms of symptom criteria, participants in the discrimination group also scored significantly higher on intrusion symptoms (Criterion B; U = 2,276.0, p < .001), avoidance (Criterion C; U = 2,405.0, p = .006), negative alterations in cognitions and mood (Criterion D; U = −2.917, p = .004), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (Criterion E; U = 2,474.0, p = .001). Note that the mean PCL-5 score of the discrimination group is 29.78 (SD = 22.56). This is very high for a nonclinical sample and above the suggested clinical cutoff score of 28 (Blevins et al., 2015) for a probable PTSD diagnosis, meaning that our participants who experienced COVID discrimination are well within the range of being at risk of developing clinically significant PTSD compared with participants who did not.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first mixed-methods study of the phenomenology of anti-Asian racism during COVID and resulting race-based stress. Our qualitative and quantitative data on 215 Asian-identified individuals of 15 ethnicities, geographically spread across the United States, triangulate to demonstrate the range and severity of racialized perpetrations and the ensuing symptoms of race-based stress and trauma. Our qualitative themes demonstrate a spectrum of perpetrations that our participants were subjected to, ranging in physical severity from avoidance and dirty looks to verbal insults and physical assault. Participants also shared powerful stories about the racial-trauma sequaelae resulting from these perpetrations, such as negative changes in cognitions of reduced self-worth and distrust of the world and increased internalizing emotions including fear, sadness, and shame. Participants’ behavioral changes spanned avoidance of trauma triggers and situations, isolation, attempts to reduce visual salience of looking Asian, and strength-based coping behaviors such as exploration of their ethnic identity and community and (re)commitment to social-justice awareness and initiatives.

Our quantitative analyses demonstrated data triangulation with our qualitative findings, converging to show that as hypothesized, participants who reported experiencing discrimination during COVID scored significantly higher on global scores and all relevant subscale scores of validated measures of microaggressions, PTSD symptoms, and racial-trauma symptoms of discrimination. Note that participants demonstrated higher endorsement of distress, hypervigilance, alienation/isolation from others, and fear and worry for their safety as assessed by the TSDS.

Negative physical-health consequences of racism and discrimination have been extensively researched, for example, in the literatures on allostatic load (Duru et al., 2012; Geronimus et al., 2006), health disparities (D. R. Williams, 1999), and social determinants of health (World Health Organization, 2008), among others. Furthermore, rich scholarship exists on race-based stress and trauma that describes the mental-health symptoms that can follow from chronic stress and retraumatization due to racism experienced by people of color (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Carlson et al., 2018; R. T. Carter, 2007; M. T. Williams et al., 2018, 2021). Despite clear reports of above-threshold PTSD Criterion B through D symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, alterations in mood and cognitions, and increased arousal and reactivity in addition, often, to above-threshold major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, mental-health symptoms resulting from chronic experiences of racism remain unacknowledged in psychiatric diagnostic criteria such as the DSM-5 (American Psychological Association, 2013) and ICD 11 (Poussaint, 2002). Indeed, racism is not listed as an example of a PTSD Criterion A stressor in a long list that includes physical assault, natural disasters, and severe motor-vehicle accidents, among others (American Psychological Association, 2013). Some scholars have contended that the lack of diagnostic acknowledgment of the possible negative psychological consequences of racialized experiences of people of color can be interpreted as symptoms being “dismissed or trivialized” or that stressors of racial discrimination are “not catastrophic enough” to warrant inclusion (Butts, 2002; Holmes et al., 2016). Indeed, diagnoses can have significant impact on access to mental-health care, insurance reimbursement, and possible other functional/tangible outcomes (e.g., service connection payments in the VA health-care system) in addition to increasing validation, externalization of symptoms, improved societal understanding and social support, and stigma reduction.

Some researchers have also advocated for PTSD-alternative psychiatric diagnostic inclusion of race-based traumatic stress or racial trauma (among other terminologies; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; R. T. Carter, 2007) for various reasons, including the distinct chronicity of racism as a stressor, which diverges from traditional Western conceptualizations of single-incident-based traumas. In some ways, this movement parallels the advocacy for complex PTSD (Giourou et al., 2018; Herman, 1992) as a new diagnosis in the ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2019), which emphasizes prolonged or repetitive events in which escape is difficult and includes all PTSD symptom criteria and additional problem in affect regulation, diminished beliefs in oneself, and difficulty in sustaining relationship with others. Furthermore, existing standards of care for PTSD, such as prolonged exposure and cognitive-processing therapy, are predicated on treating the unrealistic expectations of threat when there is no realistic threat. This tenet motivates therapeutic interventions of exposing clients to trauma triggers without engaging in safety behaviors (e.g., avoidance) to allow formation of new learning that their previous coping responses are not necessary and feared outcomes do not occur. As a result, clients’ distortions and stuck points about their safety in the world and trust in other people are cognitively restructured. These treatment strategies are warranted in single-incident-based trauma scenarios in which reperpetration is extremely unlikely to occur in the exact same way (e.g., a veteran is unlikely to experience combat situations when separated from the military and living a civilian life). In contrast, a person of color living in America is guaranteed to continue to experience racism by the simple act of living and the required encounters with every system and institution that is inherently racially inequitable.

Still other scholars have expressed hesitation with inclusion of racial trauma in diagnostic taxonomies altogether, with concerns about pathologizing symptom bearers who are perhaps exhibiting natural responses to racist institutions and systems. For example, Greene (2004) as cited in Bryant-Davis (2007) expressed that “post-racism distress is a normal response to an abnormal experience or a sane response to an insane stressor.” R. T. Carter et al. (2005) also highlighted, “It is important to note that we are not categorizing normal responses to racism as disordered.”

In the context of these diverse perspectives, we observed in our findings that participants who experienced COVID-related discrimination, compared with participants who did not, scored significantly higher on the “gold-standard” PTSD screener, the PCL-5, and over the clinical cutoff threshold, indicating probable PTSD. Note that these scores are very high for a nonclinical sample. Concurrently, participants in the discrimination group also reported significantly higher TSDS racial-trauma symptoms. Taken together, we interpret the presence of both PTSD and race-based stress symptoms to suggest a Venn diagram with circles that involve phenomenological overlap but are not entirely eclipsed.

In addition, in our study, the TSDS and PCL global scores are strongly positively correlated (r = .522, p < .001). In the initial TSDS psychometric-validation articles, M. T. Williams and colleagues (2018) used a different screener, the Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale as their PTSD measure and found a correlation of r = .488 (p < .05). Given that the TSDS is a newer measure without established clinical cutoffs, whereas the PCL is the “gold-standard” PTSD screener, the strong correlation (Cohen, 1988) between the two also sheds light on the severity of the racial-trauma symptoms present in our participants who experienced discrimination.

Our findings contribute to theoretical literature by being the one of the first (Yang et al., 2021) to describe race-based stress and trauma terminology in Asian-identified populations, given that the growing racial-trauma literature has historically been described among other populations of color. In addition, we have organized our thematic findings for direct application by clinical providers encountering clients with racial-trauma symptoms. Our observed themes underlying perpetrations such as perceived foreigner, conflating Asian with Chinese from China, and COVID vigilance can assist providers in considering examples of commonly reported racial incidents to offer high-level and hidden-meaning validation. This can also equip clients with language to label, name, and externalize their experiences, which has been demonstrated to improve well-being in clinical literature on the impact of receiving diagnoses (e.g., Young et al., 2008).

Our taxonomy of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms can also assist providers to directly assess for their presence, contextualized in a familiar Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) model (Beck, 1967), to facilitate understanding of the bidirectional relationships between these dimensions. Furthermore, identifying these symptoms may point to assisting clients with appropriate emotion-regulation skills in response to distressing emotions, behavioral activation to address isolation, exposure-based strategies to overcome avoidance, and taking committed action toward their values for further identity evolution and social-justice initiatives.

Limitations

We used a convenience sample of college students enrolled in a psychology subject pool and online participants who are engaged in Asian-interest groups that are often academically affiliated. Therefore, our age range skewed young, and participants were mostly enrolled in college or graduate and professional school. This limits generalizability in terms of age and socioeconomic status.

Qualitative limitations

As is inherent in qualitative-research methods, limitations around neutrality, objectivity, and researcher bias in analyses exist (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), thus motivating our engagement of an external auditor with an audit trail and our inclusion of qualitative codebook as an appendix (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Quantitative limitations

While the use of Mann-Whitney U tests allowed for powerful analysis of our nonnormal data distribution, these nonparametric tests typically have less statistical power than their equivalent parametric tests (i.e., t tests), which increases the possibility of a Type I error (Nachar, 2008). The cross-sectional nature of our survey precludes any ability to make causal interpretations about the relationship between experience discrimination and symptoms of PTSD and race-based stress.

In terms of future directions, because 10.5% of our sample described themselves as international students or non-U.S. individuals living in America, immigration status, international versus noninternational identification, and acculturation may be useful constructs to examine in subsequent studies to better understand additional nuances in these phenomena.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings provide several important contributions to literature on understanding the psychological impact of racialized perpetrations. Our study is the first to examine race-based stress and ensuing emotional, behavioral, and cognitive impact in an Asian-identified sample. In addition, our findings document the collective Asian experience of racial discrimination during COVID, an unprecedented period of harm experienced across the globe that warrants in-depth understanding in order to respond to the needs of people affected and protect against history repeating itself in the future.

These findings provide clear pathways of action for mental-health providers. The findings aid providers to better understand the phenomena that many of their Asian-identified clients may have experienced, known others who experienced it, or found themselves in a climate of terror in this experience (Ang, 2020; Bor et al., 2018; Heard-Garris et al., 2018). Understanding the type of perpetrations that clients have experienced and the associated changes in cognitions, emotions, and behaviors provides clinicians with concrete ways to assess for impact and implement appropriate interventions for clients.

Our findings also contribute to increasing awareness of the significant impact on the 19 million Asian Americans living in the United States, who make up about 6% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021), who have been living in a new wave of uncertainty and distress.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participants who trusted us with their stories. J. P. Yang is also thankful for University of San Francisco’s Faculty of Color Writing Retreat for providing safe and brave space for academic creativity and productivity for colorful scholars.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Joyce P. Yang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6387-0594

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6387-0594

Quyen A. Do  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7558-0247

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7558-0247

Transparency

Action Editor: Tamika C. Zapolski

Editor: Jennifer L. Tackett

Author Contributions

Joyce P. Yang: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Quyen A. Do: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Emily R. Nhan: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Jessica A. Chen: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the University of San Francisco Faculty Development Fund. J. A. Chen is supported by a VA Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award (IK2HX002866).

References

- Abu-Ras W. M., Suarez Z. E. (2009). Muslim men and women’s perception of discrimination, hate crimes, and PTSD symptoms post 9/11. Traumatology, 15(3), 48–63. 10.1177/1534765609342281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn L. H., Yang N., An M. (2022). COVID-19 racism, internalized racism, and psychological outcomes among East Asians/East Asian Americans. The Counseling Psychologist, 50(3), 359–383. 10.1177/00110000211070597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- Ang D. (2020, June24). Wider effects of police killings in minority neighborhoods. Econofact. https://econofact.org/wider-effects-of-police-killings-in-minority-neighborhoods

- AP3CON. (2020). Stop AAPI Hate. A3PCON—Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/stop-aapi-hate/

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice. (2020). Stand Against Hatred. https://www.standagainsthatred.org

- Beck A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Hoeber Medical Division, Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins C. A., Weathers F. W., Davis M. T., Witte T. K., Domino J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J., Venkataramani A. S., Williams D. R., Tsai A. C. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet, 392(10144), 302–310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Boulton E., Davey L., McEvoy C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. 10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brito C. (2021, March15). Asian restaurant vandalized with racist graffiti after owner speaks out about Texas ending mask mandate. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/mike-nguyen-texas-mask-mandate-racism/

- Bryant-Davis T., Ocampo C. (2005). Racist incident–based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33(4), 479–500. 10.1177/0011000005276465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T. (2007). Healing requires recognition: the case for race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 135–143. 10.1177/0011000006295152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Romero D. (2021, March12). Arrest in attack on elderly Asian American woman who blacked out. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/man-arrested-attack-elderly-asian-american-woman-who-blacked-out-n1261019

- Butts H. F. (2002). The Black mask of humanity: Racial/ethnic discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 30(3), 336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California State University, San Bernardino. (2021). FACT SHEET: Anti-Asian prejudice March 2020. CSUSB Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/FACT%20SHEET-%20Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%203.2.21.pdf

- Carlson M., Endlsey M., Motley D., Shawahin L. N., Williams M. T. (2018). Addressing the impact of racism on veterans of color: A race-based stress and trauma intervention. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 748–762. 10.1037/vio0000221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter N., Bryant-Lukosius D., DiCenso A., Blythe J., Neville A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Forsyth J. M., Mazzula S. L., Williams B. (2005). Racial discrimination and race-based traumatic stress: An explanatory investigation. In Carter R. T. (Ed.), Handbook of racial-cultural psychology and counseling, Vol. 2: Training and practice (pp. 447–476). https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Handbook+of+Racial+Cultural+Psychology+and+Counseling%2C+Volume+2%3A+Training+and+Practice-p-9780471386292

- Chae D. H., Yip T., Martz C. D., Chung K., Richeson J. A., Hajat A., Curtis D. S., Rogers L. O., LaVeist T. A. (2021). Vicarious racism and vigilance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health implications among Asian and Black Americans. Public Health Reports, 136(4), 508–517. 10.1177/00333549211018675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah C. S. L., Zong X., Cho H. S., Ren H., Wang S., Xue X., Wang C. (2021). Chinese American adolescents’ experiences of COVID-19 racial discrimination: Risk and protective factors for internalizing difficulties. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(4), 559–568. 10.1037/cdp0000498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.-L. (2020). Xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health implications. Journal of Interdisciplinary Perspectives and Scholarship, 3, Article 3. https://repository.usfca.edu/jips/vol3/iss1/3 [Google Scholar]

- Chung C., Li W. (2021, April20). Older Asians face ‘A Whole Wave’ of hate hidden in official NYPD stats. The City. https://www.thecity.nyc/2021/4/20/22392871/older-asians-face-a-hate-hidden-nypd

- Clarke V., Braun V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Corden A., Sainsbury R. (2006). Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: Researchers’ views. University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Clark V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher S. M., Nguyen T., Rahmani D. (2020). Prejudice toward Asian Americans in the Covid-19 pandemic: The effects of social media use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 9, Article 764681. 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen A. S. (2013). Phenomenological approaches in psychology and health sciences. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 10(3), 318–339. 10.1080/14780887.2011.608466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duru O. K., Harawa N. T., Kermah D., Norris K. C. (2012). Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality. Journal of the National Medical Association, 104(1–2), 89–95. 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30120-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle G., Kaminer D. (2013). Continuous traumatic stress: Expanding the lexicon of traumatic stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 85–99. 10.1037/a0032485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson C., Brysiewicz P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 93–99. 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Rothbaum B. O. (2001). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Sharif M. Z. (2020). Arabs, Whiteness, and health disparities: The need for critical race theory and data. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), e2–e3. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A. T., Hicken M., Keene D., Bound J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giourou E., Skokou M., Andrew S. P., Alexopoulou K., Gourzis P., Jelastopulu E. (2018). Complex posttraumatic stress disorder: The need to consolidate a distinct clinical syndrome or to reevaluate features of psychiatric disorders following interpersonal trauma? World Journal of Psychiatry, 8(1), 12–19. 10.5498/wjp.v8.i1.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover A. R., Harper S. B., Langton L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. 10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene B. (2004, August1). Treating the trauma of racism. Annual American Psychological Association Meeting, Honolulu, HI, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Guba E. G., Lincoln Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm H. C., Ha Y., Scott J. C., Wongchai V., Chen J. A., Liu C. H. (2021). Perceived COVID-19-related anti-Asian discrimination predicts post traumatic stress disorder symptoms among Asian and Asian American young adults. Psychiatry Research, 303, Article 114084. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Garris N. J., Cale M., Camaj L., Hamati M. C., Dominguez T. P. (2018). Transmitting trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 230–240. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. 10.1002/jts.2490050305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Knox S. (2021). Essentials of consensual qualitative research. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/essentials-consensual-qualitative-research [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S. C., Facemire V. C., DaFonseca A. M. (2016). Expanding Criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder: Considering the deleterious impact of oppression. Traumatology, 22(4), 314–321. 10.1037/trm0000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang M. C., Parreñas R. S. (2021). The gendered racialization of Asian women as villainous temptresses. Gender & Society, 35(4), 567–576. 10.1177/08912432211029395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inman E. M., Bermejo R. M., McDanal R., Nelson B., Richmond L. L., Schleider J. L., London B. (2021). Discrimination and psychosocial engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma and Health, 6(4), 380–383. 10.1037/sah0000349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Waters S. F. (2021). Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma and Health, 6(1), 70–78. 10.1037/sah0000275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenthang. (2022, February15). Woman stabbed over 40 times after she was followed into her NYC apartment, official says. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/woman-stabbed-40-was-followed-nyc-apartment-official-says-rcna16295

- Lin A. I.-C. (2011). Development and initial validation of the Asian American Racial Microaggressions Scale (AARMS): Exploring Asian American experience with racial microaggressions [Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University]. Columbia Academic Commons. 10.7916/D8PV6SB4 [DOI]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wang C. (2022). Asian Americans’ racial discrimination experiences during COVID-19: Social support and locus of control as moderators. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 13(3), 283–294. 10.1037/aap0000247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin J. (2020, March27). FBI warns of potential surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans amid coronavirus. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/fbi-warns-potential-surge-hate-crimes-asian-americans/story?id=69831920

- McAlister A., Lee D., Ehlert K., Kajfez R., Faber C., Kennedy M. (2017, June24). Qualitative coding: An approach to assess inter-rater reliability [Paper presentation]. 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio. 10.18260/1-2-28777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mekawi Y., Carter S., Packard G., Wallace S., Michopoulos V., Powers A. (2022). When (passive) acceptance hurts: Race-based coping moderates the association between racial discrimination and mental health outcomes among Black Americans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(1), 38–46. 10.1037/tra0001077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Misra S., Le P. D., Goldmann E., Yang L. H. (2020). Psychological impact of anti-Asian stigma due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for research, practice, and policy responses. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 461–464. 10.1037/tra0000821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachar N. (2008). The Mann-Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 4(1), 13–20. 10.20982/tqmp.04.1.p013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal K. (2011). The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal K. (2018). Microaggressions and traumatic stress: Theory, research, and clinical treatment. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal K., Wong Y., Sriken J., Griffin K., Fujii-Doe W. (2015). Racial microaggressions and Asian Americans: An exploratory study on within-group differences and mental health. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 136–144. 10.1037/a0038058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer B. E., Witkop C. T., Varpio L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97. 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C., Joffe H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. 10.1177/1609406919899220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S., Yang C., Tsai J.-Y., Dong C. (2021). Experience of and worry about discrimination, social media use, and depression among Asians in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(9), Article e29024. 10.2196/29024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. (2020, April10). Smashed windows and racist graffiti: Vandals target Asian Americans amid coronavirus. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/smashed-windows-racist-graffiti-vandals-target-asian-americans-amid-coronavirus-n1180556

- Poussaint A. F. (2002). Is extreme racism a mental illness? Yes. Western Journal of Medicine, 176(1), Article 4. 10.1136/ewjm.176.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resick P. A., Monson C. M., Chard K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S. (2019). Practising reflexivity: Ethics, methodology and theory construction. Methodological Innovations, 12(2). 10.1177/2059799119863276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue D. W., Capodilupo C. M., Torino G. C., Bucceri J. M., Holder A. M. B., Nadal K. L., Esquilin M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. B. (2022, March1). Woman of Asian descent is latest to die after an attack in New York City. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/01/nyregion/guiying-ma-queens-new-york-attack.html

- Teens arrested over racist coronavirus attack. (2020, March6). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-51771355

- Trump D. [@realDonaldTrump]. (2020, March16). Donald J. Trump on Twitter: “The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like Airlines and others, that are particularly affected by the Chinese Virus. We will be stronger than ever before!” [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1239685852093169664