Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic upended many aspects of daily life. For some individuals, this was an opportunity to re-evaluate their life and make better choices, while others were overwhelmed with stressors, leading to a deterioration in mental and physical health.

Aim

The aim of this narrative systematic review is to explore the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Mediterranean diet adherence.

Methods

A systematic literature search was carried out on PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases utilising the search terms ‘Mediterranean diet’ AND ‘COVID-19’. This yielded 73 articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Results

The data suggests that a substantial proportion of individuals adhered less to the Mediterranean diet during the COVID-19 lockdown period. However, individuals receiving some form of lifestyle intervention had better adherence to the Mediterranean diet than their unassisted counterparts.

Conclusion

This emphasises the importance of professional support during times of crisis to avoid deterioration of a population's health.

Keywords: COVID-19, lockdown, Mediterranean diet, nutrition, lifestyle

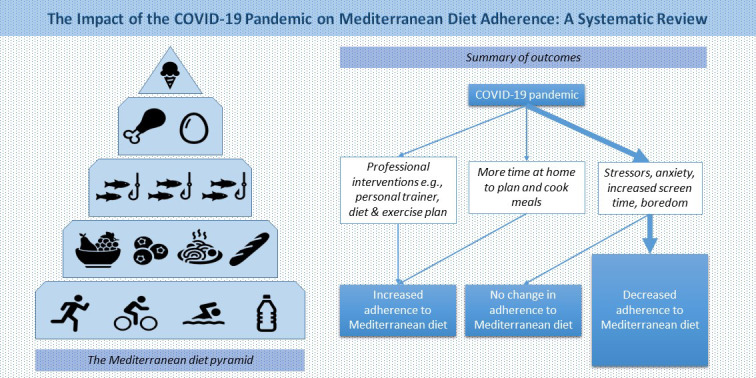

Graphical Abstract.

This is a visual representation of the abstract.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel beta-coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was discovered to be causing cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Wuhan, China (Zhu et al., 2020). During February 2020, the virus spread throughout the European continent, with Italy and Spain being mostly affected, and was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 by the World Health Organization (Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020; Alfonso Viguria and Casamitjana, 2021; Saglietto et al., 2020). This led governments and public health authorities to institute several restrictive measures to contain the viral spread and prevent the healthcare systems from being overwhelmed. However, this resulted in suspension of medical consultations at hospitals and clinics (Bonalumi et al., 2020). Additionally, the periods of confinement (‘lockdowns’) disrupted individuals’ personal and professional life, with many reports of declining mental and physical health (Hossain et al., 2020).

It is yet unsure whether the overall impact of the pandemic on dietary habits was a positive or negative one, as studies reported opposing findings (Di Santo et al., 2020; Zaragoza-Martí et al., 2021). Therefore, the effect of the pandemic on adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) is worth investigating. This is because the MD is recommended by several scientific organisations, including the American Heart Association (2020), as one of the best diets to follow. Associated health benefits include decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, improved insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles, as well as decreased inflammation and body mass index (BMI) (Martínez-González et al., 2015). Furthermore, the MD impacts the environment less than other diets as it encourages high plant consumption with low amounts of animal products, leading to smaller carbon and water footprints (Dernini and Berry, 2015). The MD is defined as the traditional nutritional regime of habitants in areas abundant with olive groves and more commonly, in areas close to the Mediterranean Sea (Kafatos et al., 2000). However, Western dietary practices have been replacing the MD in recent years. The traditional MD is compromised of the following food groups: seasonal fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, dairy, eggs and olive oil (main source of lipids). These food groups are typically arranged in a diet pyramid to show the appropriate servings of each group (Salas-Salvadó et al., 2016).

A recent systemic review, with data from 1980 to 2015, concluded that the countries having the highest adherence to the MD diet were (from highest to lowest): Spain, Greece, Italy, France, Canada, other EU countries, Japan and USA (Zaragoza-Martí et al., 2018). In general, Mediterranean countries have been drifting away from the MD in recent years (Bagues et al., 2021). Globalisation created a progressive cessation of the diet with a concurrent shift to the Western diet, which promotes weight gain, cancer and cardio-metabolic traits (Obeid et al., 2022). With more time at home during the COVID-19 lockdown periods, one would anticipate that individuals had more time to improve their health (Orr et al., 2022). However, impaired mental health and boredom may decrease the motivation for healthy lifestyle choices (Hossain et al., 2020). This narrative systematic review explores the effect of lockdown periods on adherence to the MD.

Methodology

This is a narrative systematic review with the aim of synthesis literature pertaining to the reported effects of lockdowns on the adherence to Mediterranean diet.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

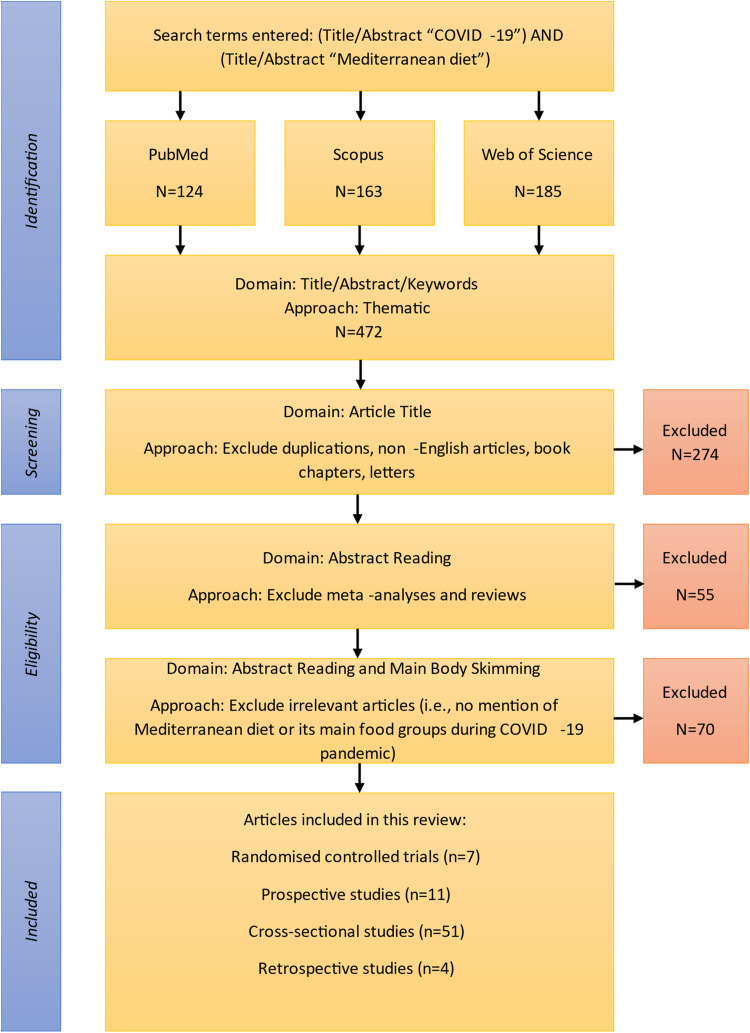

Article selection was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The article selection process is summarised using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Selected articles were written in the English language between June 2020 and November 2022. The search was conducted independently by three authors (D.B, D.R., F.F.) using the electronic databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science, using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms ‘Mediterranean diet’ AND ‘COVID-19’. The Boolean Operator ‘AND’ was included to combine search terms. Epidemiological studies that focused on changes in adherence to the Mediterranean diet during periods of lockdown in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic were included. Furthermore, handsearching was conducted to ensure that any articles missed by the electronic search were included in this review. The inclusion criteria for this review utilised the PICOS question structure (Eriksen and Frandsen, 2018) in this manner: In the general population (population), how did COVID-19 restrictions (intervention) compared to before their implementation (comparator) affect their diet and adherence to the Mediterranean diet (outcome) (Table 1)?

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram summarising the process of article selection.

Table 1.

PICOS table.

| Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Population | General population |

| Intervention | COVID-19 restrictions |

| Comparators | Before and after implementation of restrictions |

| Outcomes | Alterations in diet and adherence to Mediterranean diet |

| Study designs | Observational studies |

Exclusion criteria

Articles that were excluded from this review included: (1) articles that were not published in the English language; (2) articles that were not epidemiological studies (e.g., reviews, letters, opinion pieces, etc.); (3) articles that did not mention adherence to the Mediterranean diet or its main food groups during the COVID-19 pandemic; (4) articles exploring the effect of the Mediterranean diet on COVID-19 infection and death rates.

Data extraction

The following data was extracted from the articles included in this review: (1) Author; (2) Year of publication; (3) Ethnicity; (4) Total number of participants and percentage of females; (5) Mean age of participants; (6) Tool used to assess adherence to the Mediterranean diet; (7) Main findings. A quality risk assessment of all studies included in this review can be found in supplementary materials.

Results

Overview

This narrative systematic review yielded data from 73 epidemiological studies across 18 different countries to help answer the research question: ‘Did MD adherence change during the COVID-19 pandemic?’ Dietary habits depend largely on an individual's culture, socioeconomic status and various psychological factors (Nicolaidis, 2019). Therefore, it is not surprising that life-changing events, such as public health emergencies, have a significant impact on one's lifestyle, including dietary habits (Brown et al., 2012). The data analysed reveals a mixture of positive and negative dietary changes, as well as some unchanged dietary habits during the COVID-19 lockdown periods. The majority of studies described deviation away from the MD during lockdown. This was often accompanied by other negative habits, such as decreased physical activity and increased screen time. The articles included in this review and their corresponding main findings are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of reviewed literature.

| Author, Year | Ethnicity | Total participants (% female) | Mean age (years) | Tool used to assess MD adherence | Main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||

| Álvarez-Gómez (2021) | Spain | 510 (75) | N/A | Untitled questionnaire | Most participants maintained a healthy lifestyle during the lockdown, including increased levels of physical activity and adherence to the MD. | |

| Bagues et al. (2021) | Spain | 804 (73.13) | N/A | KIDMED | MD adherence improved with increasing age, however, the BMI worsened by increased age. Lower BMIs were seen amongst females, younger age groups and those in possession with higher degrees of studies. The latter was also related to higher MD adherence. | |

| Ben Hassen et al., 2022 | North Africa | 995 (51) | N/A | Untitled questionnaire | This study showed how the Covid-19 pandemic had a more negative effect on women than on men. When compared to men, women ate more unhealthy foods, stocked more amounts of food, changed their shopping habits more frequently and were prone to consume greater amounts of food when stressed, scared and bored. | |

| Biviá-Roig et al. (2020) | Spain | 90 (100) | 33.1 ± 4.6 | MEDAS | Results showed that 35.6% of participants (pregnant females) had high MD adherence, 57.8% had a moderate adherence, while the rest had low adherence. | |

| Biviá-Roig et al. (2021) | Spain | 85 (100) | 33.5 ± 3.7 | MEDAS | Adherence to the MD increased from the pre-confinement through to the post-confinement period. However, the overall health of participants suffered during confinement due to increased anxiety levels, increased smoking habits and reduced physical activity. | |

| Boaz et al. (2021) | Israel | 3271 (71) | 30 | I-MEDAS | Females consumed a higher volume of daily servings of vegetables, olive oil and weekly rations of baked sweets. Males displayed more consumption of carbonated drinks, alcohol. Legumes, red meat and tahini. Anxiety was associated with change in body weight, especially in females. | |

| Bonaccio et al. (2022a) | Italy | 2741 (59) | 58.1 ± 15.3 | Untitled questionnaire | Results showed that adherence to the MD decreased with a subsequent increase in ultra-processed foods (high in sugar, cholesterol, and saturated fats). Those who experienced depression from a traumatic event in their life were more likely to increase body weight during the lockdown because of a rise in number of daily meals and lowered water intake. | |

| Casas et al. (2022) | Spain | 945 (71) | 43.4 ± 13.4 | MEDAS | Most participants had a high MD adherence during confinement. Around one third of participants increased the amount of food intake and 40% reduced snacking between meals. With regards to weight change, 46% maintained the same weight, one third had weight gain and the rest experienced weight loss. | |

| Censi et al. (2022) | Italy | 1027 (47) | N/A | KIDMED | Only a third of the participants had a high adherence to the diet, with younger age groups (2–5 years) having better scores. Overall, eating habits resembled the Western diet during confinement. Around 78% of the children halted their physical activity, ages 6–11 showing the higher percentage. | |

| Cheikh Ismail et al. (2020) | United Arab Emirates | 1012 (76) | N/A | Short FFQ | Participants showed overall increased intake in homemade food and a decreased intake of fast-food. Participants ate breakfast and drank water more often during the pandemic and skipped less meals due to more time at home. However, the components of meals resembled the Western diet, rather than the traditional MD for most participants. | |

| Cirillo et al. (2021) | Italy | 140 (100) | 39.4 ± 5 | Untitled questionnaire | Adherence to the MD decreased during confinement. There was increased consumption of meat, cheese and sweets attributed to boredom, while consumption of fruits and vegetables decreased. | |

| Cobos-Palacios et al. (2021) | Spain | 158 (77) | 72.21 ± 5.04 | N/A | Results demonstrated that both Young-Old and Old-Old groups had an overall increased their adherence to the MD after intervention but reduced their physical activity and had worse mental health. Both groups consumed a higher intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, lean meats, nuts and olive oil with reduced consumption of red meat, sugary drinks, processed foods and butter. The Old-Old group, however, had a higher consumption of carbohydrates and fibre during the 12 months. | |

| Di Renzo et al. (2020) | Italy | 3533 (76) | 36.0 ± 9.0 | EHLC-COVID-19 questionnaire | There was increased intake of various components of the MD, in particular vegetables and legumes, accompanied by a decrease in non-Mediterranean foods. 17.7% and 34.4% of participants reported feeling decreased and increased satiety, respectively. | |

| Di Santo et al. (2020) | Spain | 126 (81) | 74.3 ± 6.5 | MEDAS | Around a third of participants showed decreased adherence to the MD and weight gain. | |

| Docimo et al. (2021) | Italy | 220 (51) | 9.1 ± 2.9 | KIDMED Index | High adherence to the MD was shown in only 18.6% of participants. During the pandemic, increases were seen in the number of meals and sweets consumed, leading to increased risk factors for dental caries. | |

| Dragun et al. (2020) | Croatia | 1857 (63) | 18 ± 6.0 | Untitled questionnaire | Participants (medical students) reported increased intake of fish, fruit and legumes and decreased intake of dairy, nuts and cereals. A third of participants also lost weight during the lockdown period. Adherence to the MD was associated with better quality of life and happiness, and with decreased mobile phone and TV usage. | |

| Franco et al. (2021) | Spain | 297 (50) | 42.76 ± 7.79 | PREDIMED | Overall, there was an increased adherence to the MD among Spanish office employees. Interestingly, there was an increase in both physical activity and sedentary habits during the pandemic. | |

| Galali (2021) | Iraq | 2137 (56) | N/A | EBLC-COVID19 | Most participants (56.2%) showed moderate adherence to the MD during lockdown, while only 3.5% showed high adherence. Overall, there was an increase in homemade food consumption, including both healthy and unhealthy foods. | |

| Galluccio et al. (2021) | Italy | 91 (46) | 16.60 ± 1.28 | DIMENU | There was no significant difference in pre- and post-pandemic dietary habits. Active adolescents had a higher adherence to the MD than sedentary ones. However, there is still a significant gap between the reported dietary habits and ideal habits. | |

| García-Esquinas et al. (2021) | Spain | 3041 (58) | 74.5 | MEDAS | The lockdown overall, did not cause a decline in lifestyle risk factors (diet, alcohol intake, weight or smoking) but showed an increase sedentary time and a reduced physical activity. These were reversed at the end of lockdown. People who adhered well to the MD and exercised were protected against developing unhealthier habits during lockdown. The same cannot be said for males, elderly, people with chronic morbidities and those with a high social isolation. | |

| Gerini et al. (2022) | Italy | 1228 (N/A) | N/A | Untitled questionnaire | During the pandemic, there was an overall increase in food consumption which was consistent with information found in other studies. However, a simultaneous increase of calorie dense food such as sweets and snacks was observed apart from increased vegetable and fruit intake. This illustrated progressive worsening in adherence to the MD among US and Italian participants and coupled with reduced physical activity, leads to weight gain. | |

| Grant et al. (2021) | Italy | 2678 (52) | N/A | PREDIMED PLUS | Most participants showed low adherence to the MD pre-confinement, which improved significantly during confinement. While the consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes and fish increased, there was also an increased consumption of sugary foods. | |

| Green (2021) | Israel | 212 (N/A) | 26.23 ± 6.36 | Untitled questionnaire | Novice nursing students had better dietary habits than advanced and senior ones. Furthermore, knowledge regarding the MD displayed a positive indirect effect on consumption patterns through subjective nutritional knowledge. | |

| Hanani et al. (2022) | Palestine | 329 (N/A) | 19.5 ± 1.4 | MEDAS | In terms of adherence to the MD; 24.5% of participants were highly adherent to the MD during confinement, 63.3% were moderately adherent, whilst only 11.2% were minimally adherent. | |

| Izzo et al. (2021) | Italy | 1519 (72) | 7.4 ± 1.8 | MEDAS | Most participants showed moderate adherence to the MD during lockdown (73.5%), followed by low adherence (14.7%) and high adherence (11.7%). Whilst there was increased consumption of nuts, legumes and vegetables, the consumption of fruit and vegetables was overall below the recommended amounts. | |

| Kendel Jovanović et al. (2021) | Croatia | 1370 (53) | 12.72 ± 1.17 | KIDMED | Overall, there was a significant decrease in MD adherence and physical activity, accompanied by weight gain. | |

| Karam et al. (2022) | Lebanon | 1030 (68) | N/A | MedDiet Score | Less than half of participants (39.2%) had higher-than-adequate MD adherence during the pandemic. Increased MD adherence was associated with exercising three or more times per week, living in Northern provinces, older age and tertiary educational level. | |

| Kaufman-Shriqui et al. (2021) | Israel | 3797 (76) | N/A | I-MEDAS | Over half of participants stated that their diet before the pandemic was overall healthier than what their diets consists of now. 30% of participants stated that they observed no change in their diet and the remainder stated that their diet had improved during the pandemic. Change in weight was reported in 37.2% of participants and of these, 67.8% stated that there was weight gain while the rest saw weight loss. | |

| Kolokotroni et al. (2021) | Cyprus | 745 (74) | 39 | MEDAS | There was moderate adherence to the MD during lockdown but around 30% of the participants had a higher score. There was increased consumption of both healthy (vegetables, fruits and legumes) and unhealthy (sweets and soft drinks) foods. | |

| Kyprianidou et al. (2021) | Cyprus | 1485 (N/A) | 36 ± 12 | MedDiet Score | This study included a total of 1485 participants from all areas of Cyprus. Adherence to the MD during lockdown was more likely in males and married people and was less likely in unmarried people and smokers. | |

| Lotti et al. (2022) | Italy | 653 (64) | N/A | Medi-Lite | Overall, adherence to the MD significantly increased during confinement, with a particular increase in the consumption of pasta, legumes and vegetables. | |

| Magnano San Lio et al. (2022) | Italy | 1198 (100) | N/A | FFQ | Overall, participants had reduced adherence to the MD during the pandemic, when compared to before the pandemic. Reduced amounts of fruits, vegetables, legumes, dairy and fish were consumed during the pandemic. | |

| Mariscal-Arcas et al. (2021) | Spain | 936 (45) | N/A | Untitled questionnaire | Throughout lockdown, the participants adhered very well to the MD because of the adequate consumption of legumes, vegetables, fruits, fish, meat, dairy foods and eggs. There seemed to be an increased interest in practising good health, so much so that having snacks between meals and consumption of processed foods like soft drinks and sweets was avoided. | |

| Mastorci et al. (2021) | Italy | 1289 (52) | 12.53 ± 1.25 | KIDMED | During the lockdown, participants showed a higher adherence to the MD. | |

| Mieziene et al. (2022) | Croatia, Lithunia | 1388 (64) | N/A | MEDAS | There was no statistically significant difference in eating habits between Croatian university students (Mediterranean country) and Lithuanian university students (non-Mediterranean country). Over half of participants exhibited low MD adherence. | |

| Mohajeri et al. (2021) | Iran | 2540 (N/A) | N/A | MEDAS | There was an overall increase in adherence to MD diet because of a higher consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts with the following percentages showing consumption of these food groups during lockdown: 71.85%, 60.70%, 24.72% and 14.33% respectively | |

| Molina-Montes et al. (2021) | Spain | 36,185 (77.6) | N/A | MEDAS | Results showed that adults from 16 European countries adopted a healthier diet during the pandemic as reflected by a rise in MD adherence. Most prominent adherence was observed in Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy. 52.1% of participants increased home cooking during lockdown and 57.8% decreased consumption of fast food. | |

| Morales Camacho et al. (2021) | Colombia | 266 (53.4) | 8.5 ± 2.04 | KIDMED | Children developed the habit of having breakfast every morning of the day, whilst also adding legumes in their meals more than once a week and eating pasta or rice every day. It was found that only 12% of children had high adherence to the MD. Being less than 9 years old is associated with high adherence and having female | |

| Papadaki et al. (2022) | Greece | 2088 (49) | 15.07 ± 1.46 | KIDMED | High MD adherence was observed in only 9.1% of participants. High MD adherence during lockdown was associated with higher health-related quality of life perception among participants. | |

| Pérez-Rodrigo et al. (2021) | Spain | 1155 (71) | N/A | Short FFQ | Change in food consumption during confinement was assessed according to traditional food groups. Firstly, participants showed increased consumption of unhealthy snack foods and beverages, as well as increased consumption of fresh and cooked fruit, legumes and vegetables. There was also a higher consumption of dairy products, meat and fish, but to a lesser extent, eggs. Consumption of carbohydrates (e.g., rice and pasta) also increased. | |

| Pfeifer et al. (2021) | Croatia | 4281 (80) | N/A | MEDAS | Most participants maintained similar diets before and during the lockdown. However, over half of the participants increased intake of homemade food. Adherence to the MD was mostly seen in younger females with normal BMI and a high educational level. Higher adherence to the MD was associated with increased physical activity. | |

| Prete et al. (2021) | Italy | 604 (72) | 29.8 ± 10.4 | QueMD | Around 63% of participants had an overall low adherence to the MD, and 67% increased consumption of sugary foods. Around 55% of participants reported no change in the amount of carbohydrates, fish, meat and olive oil consumed. | |

| Rodríguez-Pérez (2020) | Spain | 7514 (71) | N/A | MEDAS | Overall, there was a statistically significant increase in adherence to the MD during the lockdown period. | |

| Romero-Blanco et al. (2020) | Spain | 312 (81) | 20.5 ± 4.56 | PREDIMED | Eating habits that were ingrained in the participants (health science students) did not change significantly throughout the lockdown. Participants who followed a MD experienced increased minutes of daily sitting, although weekly patterns of physical activity also increased. | |

| Sánchez-Sánchez et al. (2020) | Spain | 1073 (73) | 38.7 ± 12.4 | PREDIMED | Adherence to the MD increased during the lockdown period, however, unhealthy food consumption also increased. Overall, duration of exercise decreased. | |

| Sulejmani et al. (2021) | Kosovo | 689 (71) | N/A | MEDAS | There was evidence that family home residents, females, people from Gjilan and those with professional educations had a higher adherence to the MD. Decreased consumption of meat and fish, increased cooking frequency and fast-food consumption led to weight gain during lockdown. | |

| Taeymans et al. (2021) | Switzerland | 821 (N/A) | N/A | bMDSC | Only 0.9% of participants were fully adherent to the MD. Nutrition/dietetics majors were more adherent to the MD than other health science students. Most respondents reported no alcohol, beer or spirit consumption in the preceding week, whilst only 0.2% of participants report drinking excessive amounts of alcohol (>7 units per day). | |

| Turki et al. (2022) | Tunisia | 1082 (74) | 32.5 ± 12.0 | MEDAS | Overall MD adherence was medium-low during lockdown. High MD adherence was associated with age, profession, household welfare proxy and location, with participants from centre-east Tunisia showing the highest adherence. | |

| Umakanthan and Lawrence (2022) | Germany | 2029 (75) | 38.9 ± 11.3 | MEDAS | Those who adhered to Covid-19 prevention measures had better adherence to the MD. This study demonstrated that those with healthier eating habits, overall have better health behaviours. | |

| Ventura et al. (2021) | Spain | 3464 (48) | N/A | KIDMED | This study included individuals <17 years of age, of whom 53.2% showed optimal adherence to the MD, with children under 6 years having the highest adherence. | |

| Villodres et al. (2021) | Spain | 899 (54) | N/A | KIDMED | This study included a total of 899 pre-adolescent participants. There was no significant difference between the degree of MD adherence before and during the pandemic, except in the first year of secondary education, where MD adherence was higher during lockdown. | |

| Case-control studies | ||||||

| Biviá-Roig et al. (2022) | Spain | 102 (33) | 45.5 ± 11.8 | MEDAS | Whilst there was no significant difference in the participants’ diet, this study justifies the need of programs to reduce depression and anxiety and improve lifestyle for potential future pandemics. | |

| Bonaccio et al. (2022a) | Italy | 4400 | N/A | MedCovid-19 Score | Participants showed an overall increased adherence to the MD during the confinement period. This was associated with increased wealth, education and male sex. | |

| Cinque et al. (2022) | Italy | 357 (33) | 61 ± 12 | Untitled questionnaire | All participants were diagnosed with NAFLD. Before the lockdown, 56% of the participants were following a balanced MD, which reduced to around 50% after lockdown. With regards to weight change, after the lockdown there was 48% who had a increase in body weight, 35% who lost weight and 17% whose weight remained the same. | |

| Grabia et al. (2021) | Poland | 219 (N/A) | N/A | MEDAS | Whilst no participant was fully adherent to the MD, the majority of those with T1DM (cases) and non-T1DM (controls) were moderately adherent. Diabetics had significantly higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, meat, butter, oil and seafood. | |

| Prospective studies | ||||||

| Bartlett et al. (2021) | Australia | 1671 (73) | 63.4 ± 7.17 | Untitled questionnaire | Results showed increased consumption of snacks and weight gain during the lockdown, however, there was a slight improvement in adherence to the MD. | |

| Ben Hassen et al. (2022) | Qatar | 356 (42) | N/A | Untitled questionnaire | During the COVID-19 pandemic, 45.5% of participants ate healthier diets with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. 42.4% chose healthier foods and 53.1% reduced the number of unhealthy foods. | |

| De Amicis et al. (2022) | Italy | 463 (83.37) | 52.5 | MEDAS | The confined group demonstrated improved adherence to the MD and a decrease in food addiction and binge eating behaviour. The fact the telemedicine was used may have aided in this improvement since it increased the link between healthcare professionals and participants during lockdown. Therefore, a well monitored weight loss program was beneficial in reducing weight gain during COVID. | |

| Faienza et al. (2022) | Italy | Adults: 123 (82.6) Children 73 (49%) | Adults: 43.4 ± 0.5 Children: 11.5 ± 0.3 |

Adults: Medi Lite Questionnaire Children: KIDMED Questionnaire | Adults gained weight in view of decreased physical activity and more hours dedicated to sleep, whilst the children gained weight due to secondarily changes in diet. A high percentage of adults and children did not perform regular exercise during lockdown was also noticed. Children showed mostly the direct correlations between dietary changes and BMI. This included decreased consumption of fresh fruit, fish and increase in cereals, carbohydrates, dairy and olive oil. | |

| Giacalone et al. (2020) | Demark | 2462 (71.1) | N/A | MEDAS | Results showed that around 30% of participants were eating more meals, snacks, gaining weight and performing fewer physical activities during the lockdown. This could be because residents more time at home, leading to increased cooking frequency and a higher degree of emotional eating. Women were more likely to be affected than men in this study. | |

| Imaz-Aramburu et al. (2021) | Spain | 267 (76) | 20.09 ± 4.04 | Untitled questionnaire | Results showed that MD adherence among healthcare students increased and that this was due to more consumption of fruits, olive oil, nuts and vegetables. Physical activity was increased as well. | |

| Marcos-Pardo et al. (2022) | Spain | 30 (100) | 64.43 ± 4.58 | PREDIMED | Participants were divided into unhealthy and healthy lifestyle groups. Both groups involved exhibited worsening of cholesterol, HDL and isometric knee extension strength parameters during confinement. In particular, the former group displayed a worsening in LDL and non-HDL lipids, fat mass/height, truncal fat mass, total fat mass, bone mineral density of femoral neck and handgrip strength. | |

| Medrano et al. (2021) | Spain | 291 (48) | 12.1 ± 2.1 | KIDMED | While adherence to the MD increased during lockdown, physical activity decreased and screen time increased. Therefore, there was an overall decline in health during lockdown. | |

| Ruggiero et al. (2021) | Italy | 3161 (60) | 57.7 ± 15.4 | ALT RISCOVID-19/Moli-LOCK | A substantial proportion of the participants (38.8%) reported increased adherence to the MD and locally grown produce, which was associated with wealth and older age. | |

| Shanmugam et al. (2021) | Various | 494 (61) | 33.4 ± 0.58 | Untitled questionnaire | The majority of participants (55%) reported weight gain during the lockdown period. The same individuals also reported increased frequency of meals, less physical activity and lower adherence to the MD. | |

| Sumalla-Cano et al. (2022) | Spain | 168 (67) | N/A | MEDAS | Participants maintained the same level of consumption of vegetables, fruits, fish, legumes, starches, white and red meat. The frequency of cooking was increased during the lockdown but there was decreased consumption of sugary drinks, low alcoholic drinks and spirits. Around 80% of participants were adherent to the MD. | |

| Randomised-controlled studies | ||||||

| Arrieta-Bartolomé et al. (2022) | Spain | 81 (17) | 57.2 ± 11.6 | MDS | MDS scores for the MD showed a significant increase from pre- to post-cardiac Rehabilitation. There was a 9% increase in individuals falling under the highly adherent category. | |

| Gonzalez-Ramirez et al. (2022) | Spain | 104 (73) | N/A | PREDIMED | The intervention group showed increased carbohydrate consumption and a decrease in fat consumption when compared to the control. During the pandemic, there were significant differences in other food groups such as fruits, vegetables, processed meat and red meat. | |

| Natalucci et al. (2021) | Italy | 30 (100) | 53.5 ± 7.6 | PREDIMED | After a 3-month intervention, there was an improved adherence to the MD and a reduction in BMI and body weight. | |

| Papandreou et al. (2021) | Greece | 55 (100) | 49.7 ± 8.1 | MedDiet Score | The intervention group received nutritional and physical activity goals and support. After three months, the intervention group showed a higher adherence to the MD than the control group, as well as a lower body fat mass and body weight. Lipid levels (LDL, cholesterol) and fasting blood glucose were elevated in the control group but remained unchanged in the intervention group. | |

| Pérez de Sevilla et al. (2021) | Spain | 23 (58) | N/A | MEDAS | Participants Initially had a small adherence to MD, however, the Intervention Group showed a large improvement over time. Participants in the intervention group increased the number of fruits and vegetables eaten in a day, excluded saturated fat in the diet and limited the amount of sweets consumed. | |

| Policarpo et al. (2021) | Portugal | 97 (26) | 54.6 ± 12.6 | PREDIMED | There were more dramatic changes seen in the control group than in the intervention. The control group showed increased daily snack consumption and weight gain, accompanied by an increase in blood glucose levels after lockdown. The intervention group had higher MD adherence and less weight gain. | |

| Zaragoza-Martí (2021) | Spain | 51 (90) | 65 ± 4.67 | PREDIMED | Participants showed a significant increase in adherence to the MD during lockdown, which was maintained after confinement was lifted. | |

MD, Mediterranean diet; N/A, not available.

Variance in Mediterranean diet adherence by age

Most studies showed that the adult age group (aged >18 years) had the highest adherence to the MD when compared to the other age groups during the COVID-19 lockdown period (Biviá-Roig et al., 2021; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Franco et al., 2021; Galali, 2021; Izzo et al., 2021; Pfeifer et al., 2021; Prete et al., 2021; Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020). Before the COVID-19 restrictions took place, more than half of adult participants in a study conducted by Grant et al. (2021) reported low adherence to the MD. The start of lockdown periods led some individuals to adopt more features of the MD as part of a holistic lifestyle change. This meant an increase in consumption of water, legumes, vegetables, whole grains, fruits, and the use of olive oil (Grant et al., 2021). The ‘self-improvement’ trend during lockdowns was also seen among adults in several of the other studies reviewed (Ben Hassen et al., 2021; Bonaccio et al., 2022b; Dragun et al., 2020; Lotti et al., 2022).

However, certain studies concluded that individuals aged over 45 years had better adherence scores compared to the younger population (Casas et al., 2022; Giacalone et al., 2020; Kyprianidou et al., 2021). This finding could be the result of the elderly perceiving their higher risk of mortality from the COVID-19 virus than other age groups, which led to their decision to stay at home and eat healthier meals (Giacalone et al., 2020). It could also be the case that with increasing age, more time was dedicated to preparation of meals, causing an increased consumption of vegetables, fruits, and legumes (Álvarez-Gómez et al., 2021).

Regarding the paediatric and adolescent populations, most studies showed that older children (10–15 years) had a better adherence to the MD, which might imply that parents were more conscious of the ongoing crisis and opted to cook more traditional MD meals (Mastorci et al., 2021; Kenđel Jovanović et al., 2021). Indeed, one study listed that this high adherence could be attributed to spending more time at home eating home-cooked meals instead of fast food. Most parents also spent more time at home due to teleworking, which translated to taking better care of their diet and buying less snacks and sweets (Kenđel Jovanović et al., 2021). Two studies revealed that better adherence was observed between the ages of 2–5 years (Ventura et al., 2021; Censi et al., 2022). Censi et al. (2022) reported that only a third of the participants had an optimal KIDMED score. A diet with poor quality may interrupt growth and development of the child and can lead to increased risk of chronic diseases appearing later on in life (Shenkin, 2006).

Variance in Mediterranean diet adherence by sex

Females appeared to adhere to the MD less when compared to their male counterparts (Ben Hassen et al., 2022; Boaz et al., 2021; Bonaccio et al., 2022b; Cheikh Ismail et al., 2020; Cirillo et al., 2021; Izzo et al., 2021; Kyprianidou et al., 2021; Sumalla-Cano et al., 2022). Before the pandemic, Boaz et al. (2021) found that both sexes abided by a healthy diet. However, significantly more women than men had a worsening in diet quality during the pandemic due to increased consumption of Western dietary components, such as pastries, cheese and meat instead of vegetables, fruits and legumes (Boaz et al., 2021). This was often coupled with increased frequency of daily meals, which can lead to obesity (Cheikh Ismail et al., 2020).

Conversely, some studies found that males were less adherent to the MD than females. According to El Khoury and Julien (2021), men reduced their intake of vegetables, rice and pasta and replaced them with fried potatoes, chips, fish, alcohol, red meat and poultry. Another study found that male participants were consuming more sweets than the female participants, even though females skipped breakfast frequently and ate a higher variety of snacks (Izzo et al., 2021). García-Esquinas et al. (2021), reported that older males tend to be socially isolated or feel lonely, live in poor housing conditions and those suffering from chronic morbidities have an increased risk of decreasing adherence to the MD during lockdown due to their increased vulnerability to restrictions. Nonetheless, at least six studies concluded that there were no significant differences in adherence to the MD based on sex (Álvarez-Gómez et al., 2021; Censi et al., 2022; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Prete et al., 2021; Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020; Ventura et al., 2021).

The main limitation in some of these studies was the fact that self-reported questionnaires were utilised, which are known to lead to self-reporting bias and recall bias (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Izzo et al., 2021; Kyprianidou et al., 2021; Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020; Shanmugam et al., 2021). Additionally, one of the featured studies pointed out another limitation that it had a larger proportion of female participants than males (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020).

Variance in Mediterranean diet adherence by country

Spain

Spanish epidemiological studies make up the largest proportion (36%) of articles identified and reviewed. Most Spanish studies reported an overall increased adherence to the MD during lockdowns (Álvarez-Gómez et al., 2021; Arrieta-Bartolomé et al., 2022; Biviá-Roig et al., 2021; Carbayo Herencia et al., 2021; Casas et al., 2022; Cobos-Palacios et al., 2021; Franco et al., 2021; Imaz-Aramburu et al., 2021; Mariscal-Arcas et al., 2021; Medrano et al., 2021; Pérez-Rodrigo et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020; Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020; Ventura et al., 2021). However, some studies noted that while MD adherence increased, the amount of unhealthy foods consumed (e.g., sugary drinks) also increased. Moreover, individuals became more sedentary and exercised less (Pérez-Rodrigo et al., 2021; Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2020). One study also reported an increase in anxiety and smoking levels (Biviá-Roig et al., 2021). A substantial number of studies reported minimal changes in MD adherence during lockdown (Bagues et al., 2021; Biviá-Roig et al., 2020; Romero-Blanco et al., 2020; Sumalla-Cano et al., 2022; Villodres et al., 2021), while only three studies reported an overall decreased adherence (Di Santo et al., 2020; Marcos-Pardo et al., 2022; Morales Camacho et al., 2021). Of note, all three Spanish randomised-controlled trials that were conducted during lockdown periods reported a significant improvement in participants’ dietary habits in the intervention group (García Pérez de Sevilla et al., 2021; Gonzalez-Ramirez et al., 2022; Zaragoza-Martí et al., 2021). These individuals were provided with a personalised diet and exercise plan, and in some cases, a personal trainer. This emphasises the importance of professional support during challenging times to encourage healthier habits in the general population.

Italy

Italian epidemiological studies make up the second largest proportion (26%) of articles identified and reviewed. Unlike their Spanish counterparts, an overall trend in MD adherence cannot be deduced from the Italian studies. Seven studies reported an increased adherence to the MD during lockdowns, particularly homemade foods (Bonaccio et al., 2022b; De Amicis et al., 2022; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2021; Lotti et al., 2022; Mastorci et al., 2021; Ruggiero et al., 2021). This was associated with older age, increased wealth, and male sex (Bonaccio et al., 2022b). However, three studies reported no change in MD adherence (Cinque et al., 2022; Galluccio et al., 2021; Izzo et al., 2021) and seven reported decreased adherence, with increased consumption of processed and sugary foods attributable to boredom (Bonaccio et al., 2022a; Censi et al., 2022; Cirillo et al., 2021; Docimo et al., 2021; Gerini et al., 2022; Magnano San Lio et al., 2022; Prete et al., 2021). Variance may be due to cultural differences between Italy's geopolitical regions. In fact, one study that included participants from various geopolitical regions reported that Northern and Central regions showed healthier lifestyle habits, as evidenced by lower BMIs, when compared to Southern regions (Di Renzo et al., 2020).

Eastern European countries

The two Cypriot epidemiological studies are in accordance with each other and report mild increases in MD adherence during lockdown. Individuals that were residing in rural areas, unmarried, male, and physically active were more likely to be adherent to the MD (Kolokotroni et al., 2021; Kyprianidou et al., 2021). Meanwhile, the Croatian population experienced a decrease in MD adherence during lockdown (Kenđel Jovanović et al., 2021; Pfeifer et al., 2021), with the exception of a select subpopulation of medical students, who showed improved dietary habits and physical activity (Dragun et al., 2020), suggesting that this behavioural pattern may be influenced by their education. A study from Kosovo reported increased MD adherence in females, especially those with higher educational attainment. However, a significant proportion of participants experienced weight gain due to additional meals and unhealthy snacks consumed (Sulejmani et al., 2021). Interestingly, Polish females with type 1 diabetes mellitus were consuming more fruit, vegetables, and seafood than their non-diabetic counterparts during lockdowns (Grabia et al., 2021).

Middle eastern countries

Most Palestinian medical students were moderately adherent to the MD (63.3% of study population) during lockdown, with the majority more likely to be engaged in physical activity, longer sleep duration and less screen time than the rest of the study population. In this study, MD adherence was not significantly associated with mental health, while physical activity and sleep were significantly associated (Hanani et al., 2022). An Iraqi study reported increased consumption of both healthy and unhealthy foods during lockdown, with most participants being moderately adherent to the MD. However, around half of participants reported a deterioration in lifestyle during the pandemic and a third of participants reported weight gain (Galali, 2021). An Israeli study revealed that 60% of participants experienced a deterioration in dietary habits, with 25% of participants experiencing weight gain and only 17% experiencing weight loss. Poor diet and weight gain were associated with increased odds of experiencing anxiety during confinement (Kaufman-Shriqui et al., 2021). In the United Arab Emirates, participants shifted towards Western dietary components during lockdowns (Cheikh Ismail et al., 2020). In contrast, Omani adults were found to improve their dietary habits during lockdowns, with 51.3% reducing their intake of unhealthy foods. Participants were inclined to buy from local food sources online and did not stockpile items (Ben Hassen et al., 2021).

Discussion

While a mixture of positive and negative lifestyle changes were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems that the majority of epidemiological studies discussed in this review reported reduced adherence to the MD. In a considerable proportion of these studies, reduced MD adherence was associated with other negative habits, such as increased screen time and reduced physical activity. This coincided with other dietary habits reported. In fact, a quantitative cross-sectional study from Turkey (Coşkun et al., 2022) reported weight gain in 59.1% of participants working from home during the lockdown period. Additionally, weight gain was associated with higher work hours, daily sedentary time and Non-Healthy Diet Index scores. Similar findings were seen in some of the studies featured in this review, where decreased MD adherence was associated with reduced physical activity (Izzo et al., 2021; Karam et al., 2022), increased screen time (Cheikh Ismail et al., 2020; Medrano et al., 2021) and increased anxiety levels (Biviá-Roig et al., 2022; Bonaccio et al., 2022a).

In contrast, an American qualitative study (Orr et al., 2022) reported improvements in females’ diet during lockdown, despite decreased sleep quality and increased stress. Interestingly, participants reported stress and poor sleep quality as the key factors that led them to improve their diets; hence, the importance of managing stress as part of a holistic lifestyle intervention. The trends in food consumption during the pandemic can be further highlighted using artificial intelligence technology. A study by Eftimov et al. (2020) analysed the type of recipes added to a popular food website during the lockdown period. Results showed dramatic increases in recipes containing pulses, soup and tortillas, as well as moderate decreases in recipes containing fish, grains and wine. These findings support the notion that individuals may have tried to use the lockdown as a chance to improve their dietary habits, as was also seen in some of the studies in this review (Dragun et al., 2020; Kaufman-Shirqui et al., 2021; Hanani et al., 2022).

Several international health organisations issued dietary recommendations during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, it is established that there is no single supplement that can reliably prevent or treat COVID-19 infection (Associação Brasileira de Nutrologia, 2020). However, it is recommended that individuals obtain a variety of micronutrients from food and vitamin D from graded sun exposure. In addition, at risk groups (e.g., breastfeeding mothers, chronically ill) may benefit from supplements during the pandemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). With regards to meals consumed, it is ideal for individuals to purchase fresh produce in favour of processed foods, in addition to using less oil and sugar when preparing meals (American Society for Nutrition, 2020).

When devising public health strategies, it is important to consider additional factors influencing nutrition that transcend the individual. On a community level, food may be unequally distributed between households, which disproportionately affects lower socioeconomic classes. This may be due to the ‘panic-buying’ and ‘stock-piling’ phenomena in response to fear of food shortages, which inevitably contributes to increased shortages, especially among those who cannot afford to buy in bulk (Timmer, 2010; Vo and Thiel, 2006). The latter population includes the elderly, frail and chronically ill, in whom nutritional deficiencies may have devastating health effects (Bialek et al., 2020). On a national level, increased economic uncertainty and altered consumer behaviours during pandemics make it increasingly difficult to keep up with the demand (Vo and Thiel, 2006). On a global level, pandemics bring about altered patterns of food distribution and shipping, which invariably affects all areas dependent on land, air and sea transportation of goods, especially across international borders (Gostin, 2006).

In reality, the COVID-19 pandemic delivered a blow to the dietary aspect of Mediterranean lifestyle that has been in steady decline during recent decades. A recent study by Quarta et al. (2021) reported moderate-to-weak MD adherence in Southern European countries, which are traditionally Mediterranean countries. Only 11% of participants were in the highly adherent group, while over half of participants were in the minimally adherent group. This level of MD adherence was only slightly higher that that obtained by non-Mediterranean Balkan countries in the same study. However, olive oil was still the main source of fat in the Mediterranean countries. The shift of women from following traditional domestic roles to being part of the workforce, as well as the fast-paced modern lifestyles may be important contributors to the abandonment of the MD (Patino-Alonso et al., 2014). Several studies note that older females that occupy more traditional roles show increased adherence to the MD when compared to younger females (Kontogianni et al., 2008; Sanchez-Villegas et al., 2002). Interestingly, a Moroccan study showed no significant differences in MD adherence between males and females. This could be due to the fact that female participants occupied more traditional roles and spend more time preparing meals (Bedmar, 2011).

Similar findings emerged in this review, as overall, decreased MD adherence was seen mostly in young females (Ben Hassen et al., 2022; Boaz et al., 2021), whilst higher MD adherence was more likely in the older age groups (Casas et al., 2022; Giacalone et al., 2020). When compared to men, women are more likely to be emotional eaters, thus resulting in increased unhealthy food consumption out of fear, boredom, or anxiety (Waller and Osman, 1998). Additionally, women who had the added responsibility of household maintenance might have turned to food as a coping mechanism (Spoor et al., 2007). It is known that prolonged stress leads to increased cortisol levels, which in turn leads to increased feeling of hunger (Ben Hassen et al., 2021; Sumalla-Cano et al., 2022). Increased stress among Spanish university students was associated with decreased MD adherence, especially in females and in those with subjects requiring communication of own ideas (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2019). Studies in this systematic review report mixed levels of MD adherence among university students and individuals of higher educational attainment (Dragun et al., 2020; Hanani et al., 2022; Taeymans et al., 2021). Therefore, further investigation is needed into the specific cultural societal factors associated with MD decline. This being said, public health strategies need to consider the root cultural causes of decreased MD adherence, apart from acute exacerbation by a public health emergency.

The epidemiological studies in this review have varying strengths and limitations. Most studies were able to gather a large number of participants due to the use of online questionnaires. While this is associated with improved generalisability, there is limited expression of individual experiences and elaborated responses. Moreover, self-reported questionnaires are subject to self-reported bias and recall bias (Di Renzo et al., 2020; García-Esquinas et al., 2021; Grant et al., 2021; Pfeifer et al., 2021). Some studies included questionnaires in different languages to cater to a multilingual population, which may improve response accuracy. However, variation between languages may result in differences in interpretation by participants, hence, requiring laborious validation processes (Cheikh Ismail et al., 2020). Some countries, such as Spain and Italy, featured in multiple studies. This is beneficial as it provides a greater understanding of the overall trends in that country and any variances between regions.

The strengths and limitations of the reviewed epidemiological studies in part depend on the tool used to assess MD adherence. These tools have several common strengths, chiefly, ease of administration, low-cost and proven validity. However, common limitations when using self-reported questionnaires are non-response bias, acquiescence bias and recall bias. The most popular tools to assess MD adherence in adults were the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) and its international variant (I-MEDAS). MEDAS and I-MEDAS are composed of 14 and 11 questions, respectively, relating to the core food groups consumed as part of the MD. Since MEDAS was designed for use by adults in Mediterranean countries, it has limited applicability in non-Mediterranean regions and in children (Schröder et al., 2011). However, I-MEDAS can be used in the latter scenarios (Abu-Saad et al., 2019). Other commonly used tools include the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), which utilises a list of foods and assesses the frequency and amount of consumption (Resnicow et al., 2000), as well as Medi-Lite (Gnagnarella et al., 2018) and QueMD (Sofi et al., 2017), which relate to the frequency of consumption of core food groups of the Mediterranean diet. These have similar strengths and limitations to the MEDAS questionnaire. A popular tool to assess MD adherence in children was the KIDMED questionnaire, which is specifically designed for use in children and adolescents (Serra-Majem et al., 2004).

The main limitation of this study is it being a narrative systematic review, rather than a meta-analysis. Hence, statistical data from the reviewed epidemiological studies have not been re-analysed and combined. Instead an in-depth view and discussion of the general findings from each study was provided. While every effort has been made to capture all the relevant epidemiological studies, some may have been missed by the search strategy employed.

Conclusion

While varying dietary patterns are seen among different populations, the large proportion of individuals experiencing decreased adherence to the MD is of concern. Increased boredom, anxiety and screen time are all factors that have been reported as possible causes for the increase in appetite and ‘comfort foods’ consumed during confinement. As noted in interventional studies, individuals having support from professionals showed improved dietary habits during lockdowns. Therefore, professional support is of utmost importance in scenarios of public health emergencies so that individuals avoid behaviours that are detrimental to their health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-nah-10.1177_02601060231187511 for The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Mediterranean diet adherence: A narrative systematic review by Francesca Farrugia, Daniel Refalo, David Bonello and Sarah Cuschieri in Nutrition and Health

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualisation, FF.; methodology, FF, DB, DR.; formal analysis, FF, DB, DR.; resources, SC.; data curation, FF, SC.; writing – original draft preparation, FF, DB, DR.; writing – review and editing, SC.; visualization, FF, SC.; supervision, SC.

Author's note: Sarah Cuschieri is also affiliated at Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, Canada.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Francesca Farrugia https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0586-779X

Sarah Cuschieri https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2012-9234

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abu-Saad K, Endevelt R, Goldsmith R, et al. (2019) Adaptation and predictive utility of a Mediterranean diet screener score. Clinical Nutrition 38(6): 2928–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhanom Ghebreyesus T. (2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 (accessed 28 August 2022).

- Alfonso Viguria U, Casamitjana N. (2021) Early interventions and impact of COVID-19 in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8): 4026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Gómez C, De La Higuera M, Rivas-García L, et al. (2021) Has COVID-19 changed the lifestyle and dietary habits in the Spanish population after confinement? Foods 10(10): 2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association (2020) What is the Mediterranean diet? Available at: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/nutrition-basics/mediterranean-diet (accessed 28 August 2022).

- American Society for Nutrition (2020) Making health and nutrition a priority during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. In: American Society for Nutrition. Available at: https://nutrition.org/making-health-and-nutrition-a-priority-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed 14 February 2023).

- Arrieta-Bartolomé G, Supervia M, Velasquez ABC, et al. (2022) Evaluating the effectiveness of a comprehensive patient education intervention in a hybrid model of cardiac rehabilitation: A pilot study. PEC Innovation 1: 100054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira de Nutrologia (2020) Posicionamento da ABRAN a respeito de micronutrientes e probióticos na infecção por COVID-19. Available at: https://abran.org.br/2020/05/01/posicionamento-da-associacao-brasileira-de-nutrologia-abran-a-respeito-de-micronutrientes-e-probioticos-na-infeccao-por-covid-19/ (accessed 14 February 2023).

- Bagues A, Almagro A, Bermúdez T, et al. (2021) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet: An online questionnaire based-study in a Spanish population sample just before the COVID-19 lockdown. Functional Foods in Health and Disease 11(6): 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett L, Brady JJR, Farrow M, et al. (2021) Change in modifiable dementia risk factors during COVID-19 lockdown: The experience of over 50 s in Tasmania, Australia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, N. Y.) 7(1): e12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedmar VL. (2011) Educación escolar/familiar y parejas marroquíes. Estudio diacrónico de la región de Casablanca. Foro de educación 9(13): 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hassen T, Bilali E, Allahyari H, et al. (2021) Observations on food consumption behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Oman. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 779654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hassen T, El Bilali H, Allahyari MS, et al. (2022) Gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on food behaviors in North Africa: Cases of Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(4): 2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, et al. (2020) Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(12): 343–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biviá-Roig G, Boldó-Roda A, Blasco-Sanz R, et al. (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles and quality of life of women with fertility problems: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 686115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biviá-Roig G, La Rosa VL, Gómez-Tébar M, et al. (2020) Analysis of the impact of the confinement resulting from COVID-19 on the lifestyle and psychological wellbeing of Spanish pregnant women: An internet-based cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(16): E5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biviá-Roig G, Soldevila-Matías P, Haro G, et al. (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles and levels of anxiety and depression of patients with schizophrenia: A retrospective observational study. Healthcare (Basel) 10(1): 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaz M, Navarro DA, Raz O, et al. (2021) Dietary changes and anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic: Differences between the sexes. Nutrients 13(12): 4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio M, Costanzo S, Bracone F, et al. (2022a) Psychological distress resulting from the COVID-19 confinement is associated with unhealthy dietary changes in two Italian population-based cohorts. European Journal of Nutrition 61(3): 1491–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio M, Gianfagna F, Stival C, et al. (2022b) Changes in a Mediterranean lifestyle during the COVID-19 pandemic among elderly Italians: An analysis of gender and socioeconomic inequalities in the ‘LOST in Lombardia’ study. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 73(5): 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonalumi G, di Mauro M, Garatti A, et al. (2020) The COVID-19 outbreak and its impact on hospitals in Italy: The model of cardiac surgery. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 57(6): 1025–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NA, Smith KC, Kromm EE. (2012) Women’s perceptions of the relationship between recent life events, transitions, and diet in midlife: Findings from a focus group study. Women & Health 52(3): 234–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbayo Herencia JA, Rosich N, Panisello Royo JM, et al. (2021) Influence of the confinement that occurred in Spain due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus outbreak on adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Clinica E Investigacion En Arteriosclerosis: Publicacion Oficial De La Sociedad Espanola De Arteriosclerosis 33(5): 235–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas R, Raidó-Quintana B, Ruiz-León AM, et al. (2022) Changes in Spanish lifestyle and dietary habits during the COVID-19 lockdown. European Journal of Nutrition 61(5): 2417–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Censi L, Ruggeri S, Galfo M, et al. (2022) Eating behaviour, physical activity and lifestyle of Italian children during lockdown for COVID-19. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 73(1): 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and breastfeeding. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/maternal-or-infant-illnesses/covid-19-and-breastfeeding.html (accessed 14 February 2023).

- Chacón-Cuberos R, Zurita-Ortega F, Olmedo-Moreno EM, et al. (2019) Relationship between academic stress, physical activity and diet in university students of education. Behavioral Sciences 9(6): 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheikh Ismail L, Osaili TM, Mohamad MN, et al. (2020) Eating habits and lifestyle during COVID-19 lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 12(11): E3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinque F, Cespiati A, Lombardi R, et al. (2022) Interaction between lifestyle changes and PNPLA3 genotype in NAFLD patients during the COVID-19 lockdown. Nutrients 14(3): 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo M, Rizzello F, Badolato L, et al. (2021) The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and emotional state in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology: Results of an Italian survey. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction 50(8): 102079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos-Palacios L, Muñoz-Úbeda M, Ruiz-Moreno MI, et al. (2021) Lifestyle modification program on a metabolically healthy elderly population with overweight/obesity, young-old vs. old-old. CONSEQUENCES of COVID-19 lockdown in this program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(22): 11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun MG, Öztürk Rİ, Tak AY, et al. (2022) Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on diet, sedentary lifestyle, and stress. Nutrients 14(19): 4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Amicis R, Foppiani A, Galasso L, et al. (2022) Weight loss management and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: A matched Italian cohort study. Nutrients 14(14): 2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernini S, Berry EM. (2015) Mediterranean diet: From a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Frontiers in Nutrition 2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, et al. (2020) Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine 18: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Santo SG, Franchini F, Filiputti B, et al. (2020) The effects of COVID-19 and quarantine measures on the lifestyles and mental health of people over 60 at increased risk of dementia. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 578628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docimo R, Costacurta M, Gualtieri P, et al. (2021) Cariogenic risk and COVID-19 lockdown in a paediatric population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(14): 7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragun R, Veček NN, Marendić M, et al. (2020) Have lifestyle habits and psychological well-being changed among adolescents and medical students due to COVID-19 lockdown in Croatia? Nutrients 13(1): 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftimov T, Popovski G, Petković M, et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends in Food Science & Technology 104: 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury CN, Julien SG. (2021) Inverse association between the Mediterranean diet and COVID-19 risk in Lebanon: A case-control study. Frontiers in Nutrition 8: 707359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. (2018) The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: A systematic review. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA 106(4): 420–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faienza MF, Colaianni V, Di Ciaula A, et al. (2022) Different variation of intra-familial body mass index subjected to COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases 31(2): 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco E, Urosa J, Barakat R, et al. (2021) Physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet among Spanish employees in a health-promotion program before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: The sanitas-healthy cities challenge. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(5): 2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galali Y. (2021) The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the eating habits and lifestyle changes: A cross sectional study. Food Science & Nutrition 9(4): 2105–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluccio A, Caparello G, Avolio E, et al. (2021) Self-Perceived physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in healthy adolescents during COVID-19: Findings from the DIMENU pilot study. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 9(6): 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Esquinas E, Ortolá R, Gine-Vázquez I, et al. (2021) Changes in health behaviors, mental and physical health among older adults under severe lockdown restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(13): 7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Pérez de Sevilla G, Barceló Guido O, De la Cruz M de la P, et al. (2021) Remotely supervised exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic versus in-person-supervised exercise in achieving long-term adherence to a healthy lifestyle. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(22): 12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerini F, Fantechi T, Contini C, et al. (2022) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and COVID-19: A segmentation analysis of Italian and US consumers. Sustainability 14(7): 3823. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone D, Frøst MB, Rodríguez-Pérez C. (2020) Reported changes in dietary habits during the COVID-19 lockdown in the Danish population: The Danish COVIDiet study. Frontiers in Nutrition 7: 592112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnagnarella P, Dragà D, Misotti AM, et al. (2018) Validation of a short questionnaire to record adherence to the Mediterranean diet: An Italian experience. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 28(11): 1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ramirez M, Sanchez-Carrera R, Cejudo-Lopez A, et al. (2022) Short-Term pilot study to evaluate the impact of salbi educa nutrition app in macronutrients intake and adherence to the Mediterranean diet: Randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 14(10): 2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L. (2006) Public health strategies for pandemic influenza ethics and the law. JAMA 295(14): 1700–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabia M, Puścion-Jakubik A, Markiewicz-Żukowska R, et al. (2021) Adherence to Mediterranean diet and selected lifestyle elements among young women with type 1 diabetes mellitus from northeast Poland: A case-control COVID-19 survey. Nutrients 13(4): 1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant F, Scalvedi ML, Scognamiglio U, et al. (2021) Eating habits during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: The nutritional and lifestyle side effects of the pandemic. Nutrients 13(7): 2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G. (2021) Nursing students’ eating habits, subjective, and Mediterranean nutrition knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Nursing 7: 23779608211038210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani A, Badrasawi M, Zidan S, et al. (2022) Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy program on mental health status among medical student in Palestine during COVID pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 22(1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, et al. (2020) Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Research 9: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaz-Aramburu I, Fraile-Bermúdez A-B, Martín-Gamboa BS, et al. (2021) Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles of health sciences university students in Spain: A longitudinal study. Nutrients 13(6): 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo L, Santonastaso A, Cotticelli G, et al. (2021) An Italian survey on dietary habits and changes during the COVID-19 lockdown. Nutrients 13(4): 1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafatos A, Verhagen H, Moschandreas J, et al. (2000) Mediterranean diet of crete: Foods and nutrient content. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 100(12): 1487–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam J, Ghach W, Bouteen C, et al. (2022) Adherence to Mediterranean diet among adults during the COVID-19 outbreak and the economic crisis in Lebanon. Nutrition & Food Science 52(6): 1018–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman-Shriqui V, Navarro DA, Raz O, et al. (2021) Multinational dietary changes and anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic-findings from Israel. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 10(1): 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenđel Jovanović G, Dragaš Zubalj N, Klobučar Majanović S, et al. (2021) The outcome of COVID-19 lockdown on changes in body mass index and lifestyle among Croatian schoolchildren: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 13(11): 3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotroni O, Mosquera MC, Quattrocchi A, et al. (2021) Lifestyle habits of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Cyprus: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21(1): 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontogianni MD, Vidra N, Farmaki A-E, et al. (2008) Adherence rates to the Mediterranean diet are low in a representative sample of Greek children and adolescents. The Journal of Nutrition 138(10): 1951–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianidou M, Christophi CA, Giannakou K. (2021) Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among the Cypriot population. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 90: 111313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotti S, Dinu M, Pagliai G, et al. (2022) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet increased during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: Results from the web-based Medi-Lite questionnaire. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 73(5): 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnano San Lio R, Barchitta M, Maugeri A, et al. (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dietary patterns of pregnant women: A comparison between two mother-child cohorts in Sicily, Italy. Nutrients 14(16): 3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-Pardo PJ, Abelleira-Lamela T, González-Gálvez N, et al. (2022) Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on health parameters and muscle strength of older women: A longitudinal study. Experimental Gerontology 164: 111814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal-Arcas M, Delgado-Mingorance S, Saenz de Buruaga B, et al. (2021) Evolution of nutritional habits behaviour of Spanish population confined through social Media. Frontiers in Nutrition 8: 794592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, Estruch R, et al. (2015) Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Insights from the PREDIMED study. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 58(1): 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastorci F, Piaggi P, Doveri C, et al. (2021) Health-Related quality of life in Italian adolescents during COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Pediatrics 9: 611136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrano M, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Oses M, et al. (2021) Changes in lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: A longitudinal analysis from the MUGI project. Pediatric Obesity 16(4): e12731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieziene B, Burkaite G, Emeljanovas A, et al. (2022) Adherence to Mediterranean diet among Lithuanian and Croatian students during COVID-19 pandemic and its health behavior correlates. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 1000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohajeri M, Ghannadiasl F, Narimani S, et al. (2021) The food choice determinants and adherence to Mediterranean diet in Iranian adults before and during COVID-19 lockdown: Population-based study. Nutrition & Food Science 51(8): 1299–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Montes E, Uzhova I, Verardo V, et al. (2021) Impact of COVID-19 confinement on eating behaviours across 16 European countries: The COVIDiet cross-national study. Food Quality and Preference 93: 104231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Camacho WJ, Zambrano SEO, Camacho MAM, et al. (2021) Nutritional status and high adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Colombian school children and teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic according to sex. Journal of Nutritional Science 10: 54. [Google Scholar]

- Natalucci V, Marini CF, Flori M, et al. (2021) Effects of a home-based lifestyle intervention program on cardiometabolic health in breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10(12): 2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis S. (2019) Environment and obesity. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 100S: 153942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid CA, Gubbels JS, Jaalouk D, et al. (2022) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among adults in Mediterranean countries: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Nutrition 61(7): 3327–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr K, Ta Z, Shoaf K, et al. (2022) Sleep, diet, physical activity, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. Behavioral Sciences 12(3): 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki S, Carayanni V, Notara V, et al. (2022) Anthropometric, lifestyle characteristics, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and COVID-19 have a high impact on the Greek adolescents’ health-related quality of life. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 11(18): 2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou P, Gioxari A, Nimee F, et al. (2021) Application of clinical decision support system to assist breast cancer patients with lifestyle modifications during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomised controlled trial. Nutrients 13(6): 2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patino-Alonso MC, Recio-Rodríguez JI, Belio JFM, et al. (2014) Factors associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the adult population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 114(4): 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rodrigo C, Gianzo Citores M, Hervás Bárbara G, et al. (2021) Patterns of change in dietary habits and physical activity during lockdown in Spain due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 13(2): 00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer D, Rešetar J, Gajdoš Kljusurić J, et al. (2021) Cooking at home and adherence to the Mediterranean diet during the COVID-19 confinement: The experience from the Croatian COVIDiet study. Frontiers in Nutrition 8: 617721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policarpo S, Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. (2021) Telemedicine as a tool for dietary intervention in NAFLD-HIV patients during the COVID-19 lockdown: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 43: 329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prete M, Luzzetti A, Augustin LSA, et al. (2021) Changes in lifestyle and dietary habits during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: Results of an online survey. Nutrients 13(6): 1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]