Abstract

This study developed a model that predicted factors that prompt the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. Data were collected from 385 respondents across Nigeria using snowball sampling technique with online questionnaire as instrument. Results indicated that cues to action, health motivation, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control positively predicted the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria. However, perceived susceptibility, severity, and COVID-19 vaccine benefits did not predict the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Further findings showed that COVID-19 vaccine barrier and attitude was negatively associated with the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccine, Nigeria, perceived behavioural control, subjective norms

Introduction

This research aimed to develop a model that predicts factors that prompt the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. Since the end of 2019, pieces of evidence have shown that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected multiple aspects of human endeavour such as education, economy, occupations, mental and physical health (Fan et al., 2021). As of 30 July, 2021 the World Health Organization (2021) reported 195,886,929 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 4,189,148 deaths and a total of 3,829,935,772 vaccine doses have been administered. As most countries continue to battle with the COVID-19, different treatment plans have been implemented to manage the disease such as wearing a face mask and frequent hand washing (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). In addition to these strategies used to reduce the spread of the virus, recent research shows that vaccination against the virus is a paramount measure for curtailing the adverse effect and spread of the virus (Fan et al., 2021). As such, in response to the urgent need to control the spread of the virus, the COVID-19 vaccine production has been accelerated worldwide and more than 60 vaccines are undergoing clinical trial (Fan et al., 2021).

Despite these efforts, recent pieces of evidence have revealed significant resistance to a vaccine which is defined as refusal, reluctance, or delay in accepting to be vaccinated despite the availability of a vaccine (Frank and Arim, 2020; Shapiro et al., 2018). The resistance in taking the vaccine may hamper the success of regulating the spread of the virus (Barello et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2020). Further shreds of evidence show that despite the data suggesting that the vaccine is safe and effective, scepticism with regards to their usage exists globally. For instance, evidence has shown that the acceptance rate was 55% in Russia and 59% in France (Lazarus et al., 2021). This poses a threat to curtailing the spread of the virus as a majority of the populace must get the vaccine to build insusceptibility.

One recent research has shown that vaccination hesitation is one of the most major threats to world health due to various social media vaccine misinformation (Yahaghi et al., 2021). It has also been reported that people might not want to endure adverse reactions to the vaccine (Trogen et al., 2020). It is, therefore, necessary to examine the factors that may or may not affect the decision of people with regards to taking the vaccine. These lines of research have attracted a growing body of studies. For example, there has been a study that examines COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in Iraq (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). Another research was carried out among Iranian citizens to realise the factors affecting their COVID-19 intake with a focus on understanding how fear of COVID-19 and perceived infectability play a role (Yahaghi et al., 2021). In the Chinese region, Fan et al. (2021) extended the theory of planned behaviour to explain the intention to COVID-19 vaccine uptake among University students. While Ogilvie et al. (2021) investigated the intention to receive COVID-19 among Canadians. In respective of these researches, studies that focused on Nigeria is scarce despite the increasing death rate. Studies in Nigeria have focused more on predicting COVID-19 health behaviour initiation (Gever et al., 2021; Oyeoku et al., 2021), with a lack of focus on the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intake. No doubt realising the factors that affect COVID-19 vaccine intake in Nigeria will contribute to the global effort of curtailing the virus as well as contribute to the growing body of recent studies focusing on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

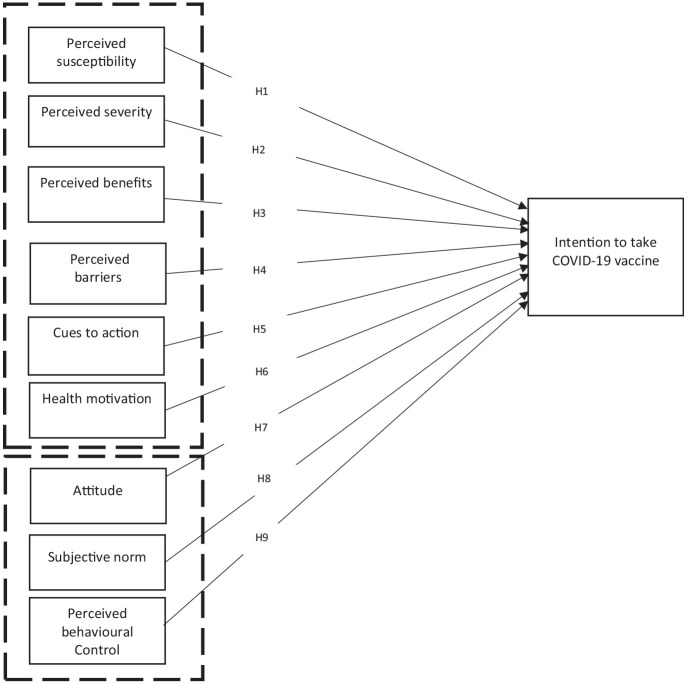

A recent study suggests that when evaluating vaccine intentions, researchers should make an assessment based on a validated theoretical framework to offer robust information for programme planning (Shmueli, 2021). We integrated variables from the theory of planned behaviour and the health belief model to come up with a comprehensive model that examines the factors that predict the intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. Nigeria provides a good context to examine predictors of vaccine intake because there have been conspiracy theories related to the vaccine (Ale, 2021) as well as high level of scepticism among some Nigerian population, suggesting that the vaccine is produced by the Western world to depopulate Africa (Olijo, 2021). Nevertheless, the success of any COVID-19 vaccine depends on the uptake in a given population. Therefore, realising the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intake intentions in Nigeria will help the government and the public health sectors to design public health programmes to optimise vaccination rates. We focused on intention rather than actual behaviour because as at the time of data gathering COVID-19 vaccine distribution in Nigeria has not covered the entire population.

Literature review

We reviewed literature in this study under the following subheadings:

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and intake in Nigeria

Evidence has shown that one of the issues that hinder the adoption of health behaviour with regards to COVID-19 in Nigeria is rumour and myth (Ugwuoke et al., 2021). For example, some Nigerians have the notion that the virus does not exist in Nigeria, suggesting that it might be present in other parts of the globe but not in the country (Apuke and Omar, 2021a; Melugbo et al., 2021). It has been reported that such a notion significantly plays a role in influencing the adoption of health behaviour related to COVID-19 (Onuora et al., 2021). There is another rumour wildly held by many Nigerians, suggesting that the virus only affects rich people and the poor are not vulnerable (Apuke and Omar, 2021a). Others also hold the notion that the virus is politically inclined, and some government officials are only using it to syphon the country’s treasury (Apuke and Omar, 2021b). While others believe that the vaccine was designed by Bill Gate to inject a microchip to reduce the population of the African continent, however, this rumour was debunked by Bill Gate (Onuora et al., 2021). Based on these issues, it is vital to examine further the factors that affect the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine among the African population, especially Nigerians.

No doubt, the growing global spread of COVID-19 has sparked a growing amount of studies to understand the factors affecting people’s vaccine acceptance and rejection. Yet, there have been fewer studies carried out in the African region and even scarce studies that have focused on Nigeria the black most populous country. Closer scrutiny of the literature found one recent study conducted in Nigeria to understand the role visual illustration has in convincing people to take the COVID-19 vaccine (Ugwuoke et al., 2021). It was concluded that those who are exposed to visual illustration are more likely to accept to take the vaccine. Another study was conducted to examine willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria (Tobin et al., 2021). Age, gender, vaccine manufacturer trust, public health authority trust, and willingness to pay for and travel for a vaccine were all found to be significant predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Adebisi et al. (2020) also carried out research to look at the public perception of the hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria. The researchers found that most of the sampled population had a strong intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine when available. However, the few other respondents that were not willing to take the vaccine belief that their immune system was enough to fight COVID-19.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and intake globally

Studies have also been conducted away from the Nigerian scene using the HBM. For example, Chu and Liu (2021) investigated the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine among Americans. The study integrated three theories to include TPB, HBM and extended parallel process model. An online survey among 934 respondents was done to assess the influence of risk perception and fear linked with COVID-19. The study also looked at the attitude towards COVID-19, self-efficacy, and other psychological and social variables along with demographic characteristics. At the end of the study, it was realised that many of the respondents reported their willingness to get vaccinated, however, they underrated their risk of getting COVID-19. Safety concerns negatively predicted intention to take a vaccine, while perceived community benefits positively predicted vaccination intake. It was also found that positive attitude and recent vaccine history was positively associated to take vaccine among the sampled population.

A similar study was conducted among the Hong Kong population (Wong et al., 2021). The study found that the perceived benefits of the vaccine, perceived severity, self-reported health outcomes, cues to action, trust in the healthcare system or manufacturers of vaccine positively predicted vaccine acceptance. While harm and perceived access barriers were negatively related to vaccine uptake. Further results showed that perceived susceptibility had no association with vaccine acceptance while government recommendation was the strongest predictor of vaccine acceptance. Wang et al. (2020) studied the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in China and found that perception regarding the high risk of infection, being vaccinated in the past, having confidence in the efficiency of the vaccine or recommendations from doctors increased the likelihood to take COVID-19 vaccine. There has also been research that examines COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in Iraq (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). It was revealed that past vaccine intake, vaccine support, subjective norm, cue to action, perceived benefit and preventive measures were factors positively associated with COVID-19 vaccine intake. However, perceived barriers were negatively associated with the vaccine intake because respondents who expressed high barriers were less likely to expose themselves to the vaccination. Furthermore, a study conducted among Peruvians found the severity of previous infection with COVID-19, perceived likelihood of contracting the virus, place of residence, fear of the disease, concerns about the sale of vaccine and trust in the vaccine significantly predicted the intention to take the vaccine (Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2021).

Recently, researchers have successfully used the TPB to predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. For example, one recent research showed that respondents who had a more positive attitude towards vaccine intake, scored higher in subjective norms and self-efficacy were found to have a higher willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (Guidry et al., 2021). Yahaghi et al. (2021) study revealed that perceived behavioural control, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived COVID-19 infectability were associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among Iranian. Fan et al. (2021) extended the theory of planned behaviour to explain the intention to COVID-19 vaccine uptake among University students. The study found that risk perception and knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine positively predicted students’ attitude to COVID-19 vaccine intake. In turn, their attitude and past intake of influenzas vaccination were related to the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. Perceived behavioural control and subjective norm were not found to be associated with the intention of taking COVID-19 vaccine

A similar study conducted in China found that parent’s positive attitude, family members support of COVID-19 vaccine intake for children, and the perceived behavioural control that parents have over their children’s vaccine intake were positively related to higher parental acceptance for their children to get vaccinated (Zhang et al., 2020). Despite these studies, more evidence is required to better understand the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine, especially in a less well-researched area such as Nigeria.

Theoretical underpinning and hypotheses development

To develop the hypotheses and model of this study we drew from two theories. Health belief model (HBM) and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB).

Health belief model (HBM)

There are arguments among scholars that the three main constructs of TPB might not be sufficient in elucidating complex health behaviour (Sniehotta et al., 2014; Yahaghi et al., 2021). Therefore, we extended the TPB by incorporating variables from the HBM. It has been shown that the HBM does not only explain the motives of individuals to vaccinate but also the reason for refusing to vaccinate, which is important in understanding vaccine intake among a given population (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). The focal principle of the HBM is that prevailing views can forecast forthcoming behaviours. When this principle is applied to disease prevention, it advocates that an individual’s preparedness to prevent an illness together with their expectations of a specific action such as receiving a vaccine could serve as a forecaster for upcoming behaviour (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). The HBM also suggests that individuals do not just involve in health behaviour, but their behavioural change is determined by some psychological factors (Oyeoku et al., 2021). These factors include perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, benefit involve in taking an action, barriers that hinder one from taking an action and cues that motivate one to take an action (Oyeoku et al., 2021). The first variable, the perceived susceptibility specifies the level at which a person believes that he or she can be affected or susceptible to an existing health issue. In this study, it indicates an individual’s thinking that he or she is vulnerable to COVID-19 or not. Therefore, the more individuals think they are vulnerable to COVID-19, the more they are likely to accept the vaccine. The second variable, perceived severity indicates the magnitude of the danger a disease pose. In other words, individuals are more inclined to engage in health behaviour if they feel a health condition is serious. Relating this to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is assumed that those who perceive the pandemic as severe are more likely to accept vaccination. On the other hand, if they perceive the pandemic as not severe, they are likely not to show interest in the vaccine. The third variable in the HBM model is concerned with the benefit attached to taking certain health behaviour. This is regarded as perceived benefit. The HBM assumes that when individuals perceived certain benefits is attached to adopting a particular health behaviour, they are more inclined to take part in such behaviour than if they perceive there are no advantages attached. Relating this to the pandemic, those who have a higher perception over the perceived benefit of taking vaccine are more likely to take the vaccine.

The HBM also assumes that despite the assumption of people towards the benefits of engaging in health action, some barriers hinder people from fully engaging in health behaviour. The model referred to it as perceived barriers to action. Relating this to the pandemic, certain barriers could discourage people from taking the vaccine such as fear of adverse effects, lack of vaccine centres, and so on. The cue to actions is another important variable in the HBM. This implies the forces that stimulate an action (Lizewski and Maguire, 2010). In the COVID-19 context, the more individuals are exposed and believe the motivation of health care workers, government and WHO, and so on, the higher likelihood they will be inclined to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Finally, the heath motivation variable has also been associated with the HBM. One recent study explored health motivation as a predictor of health behaviour (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2021). So, we added and tested health motivation to the variables of HBM. This highlight that those who are willing or motivated to improve their health will be more inclined to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Based on the HBM, we proposed the following:

H1. Perceived susceptibility is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H2. Perceived severity is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H3. COVID-19 vaccine benefits are positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H4. COVID-19 vaccine barriers are negatively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H5. Cues to action is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H6. Health motivation is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

Theory of planned behaviour (TPB)

The TPB proposed by Ice Ajzen as a successor of the Theory of Reason Action is used to predict people’s behaviour with regards to intention to get vaccinated (Shmueli, 2021; Wiemken et al., 2015). The TPB is made up of three variables that predict an individual’s behavioural intention. These three variables are attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, 1985). These variables together shape an individual’s intention to take COVID-19 vaccine as in the case of this current study. Individuals’ attitude towards a behaviour refers to the extent to which a person has a positive or negative assessment towards a precise behaviour (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1975). The perceived subjective norm refers to a person’s observation concerning the verdicts of close relations such as friends, family and society members, with respect to engaging in an explicit behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Perceived behavioural control is the self-assurance a person has on the possibility of effectively engaging in precise behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

Relating these three variables to the issue of COVID-19 vaccine intake, attitude indicates an individual’s judgement (positive or negative) regarding getting vaccinated as well as the vaccine itself. Subjective norms deal with an individual’s perception of others opinion on COVID-19 vaccination intake. It also looks at the influence or opinion of others (especially close relationships to include spouse, friends, and families) with regard to COVID-19 intake. Whereas, perceived behavioural control indicates an individual perception regarding their ability and control to get vaccinated. The ability and control could be time, financial support, or opportunity. In this regard, we hypothesised that

H7. Attitude is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H8. Subjective norm is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

H9. Perceived behavioural control is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure 1 shows the model developed in this current research.

Figure 1.

Model predicting intention to take COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria.

Material and methods

Study setting and design

A survey research design was undertaken in this study. Specifically, a cross-sectional, self-administered electronic survey questionnaire among the general population of Nigerians 18 years and above was done. The survey took a period of about 2 weeks to complete; from 15 to 30 July 2021. To determine the minimum sample size for this study, a G-power analysis was conducted using an effect size of 0.15, alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.80 on eight predictors. We realised that 166 responses would be enough to produce a power of more than 95%, which is adequate, and the outcome could be used with confidence.

To collect our data, a snowball sampling technique was utilised in which questionnaires were circulated via various social media in Nigeria, asking respondents to distribute the questionnaire further to their network members. Using this process, we were able to collect data from 543 respondents, however, we realised 385 as useable, given a response rate of 70.1%. The questionnaire had an introductory section that explains to the participants what is required of them. It also signified that they are permitted to opt-out of the survey anytime and they should be rest assured of their confidentiality. We had a screening question that inquired if respondents are above 18, for those who ticked ‘NO’ the questionnaire terminated with a thank you note. Table 1 shows the characteristics of our participants.

Table 1.

Profile of respondents.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 205 | 53.2 |

| Female | 180 | 46.8 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 129 | 33.5 |

| 25–34 | 100 | 25.9 |

| 35–44 | 87 | 22.6 |

| 45–54 | 39 | 10.1 |

| 55–64 | 20 | 5.2 |

| 65 and above | 10 | 2.6 |

| Working status | ||

| Employed full time | 80 | 20.8 |

| Employed part-time | 43 | 11.1 |

| Student | 149 | 38.7 |

| Retired | 15 | 3.9 |

| Unemployed | 58 | 15.1 |

| Others | 40 | 10.4 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 110 | 28.6 |

| Diploma | 10 | 2.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 139 | 36 |

| Master’s degree | 72 | 18.7 |

| PhD | 43 | 11.2 |

| Others | 11 | 2.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Igbo (Eastern Nigeria) | 95 | 24.7 |

| Yoruba (Western Nigeria) | 103 | 26.7 |

| Hausa (Northern Nigeria) | 110 | 28.6 |

| Others (Other regions) | 77 | 20 |

| I am planning to receive the COVID-19 vaccine | Strong agree- | 40.3 |

| Agree | 14.5 | |

| Undecided | 10.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 30.1 | |

| Disagree | 4.9 | |

| Sources of COVID-19 vaccine | Social media/TV/newspapers | 55.6 |

| Friends and colleagues | 22.3 | |

| Health care providers | 16.9 | |

| Not informed | 5.2 | |

Measures

A 5-point Likert-type scale was used to measure our constructs in which 5 signifies strongly agree and 1 denotes strongly disagree. All the items used in this study were adapted from prior related investigations (See Appendix A). To validate the items, four experts were consulted. Two from the University of Nigeria and the other two from Taraba State University, Nigeria. They scrutinised the items and made necessary suggestions on how to improve them. Using their suggestions, we reworded some items as well as expunged some unrelated items. After this exercise, we further conducted a pilot study among 30 participants. The outcome also assisted us in finalising the items used in this study.

Data analysis and common method bias

SPSS version 25 was used to analyse the descriptive aspect of this study. While, Smart PLS was used to calculate the relationship between variables (Nitzl et al., 2016). When data are collected from the same source, there is a tendency of common method bias (CMB). Therefore, CMB was tested in this study using Harman’s single factor test and a factor only explained 25% of the variance which is less than 50%, suggesting the absence of CMB (Khan et al., 2019).

Results

Measurement model

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the convergent and discriminant validity is not an issue in this study. With regards to the convergent validity, the values for Cronbach’s alpha, outer loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted were above the threshold of 0.7, 0.7, 0.7 and 0.5, respectively (Hair and Sarstedt, 2019; Henseler et al., 2014; Sarstedt et al., 2016). Furthermore, no value with regard to the discriminant validity was above the threshold of 0.85 (Hair et al., 2019) (See Table 3).

Table 2.

Construct reliability, composite reliability and AVE values.

| Constructs | Code | M | SD | Outer loading | Cronbach alpha | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility (NS) | PSUS1 | 4.62 | 1.79 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 1.34 |

| PSUS2 | 4.93 | 1.69 | 0.92 | |||||

| PSU3 | 4.97 | 1.73 | 0.76 | |||||

| PSU4 | 5.36 | 1.53 | 0.82 | |||||

| Perceived severity | PSEV 1 | 3.62 | 1.70 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 2.34 |

| PSEV2 | 3.67 | 1.64 | 0.82 | |||||

| PSEV 3 | 3.32 | 1.63 | 0.90 | |||||

| PSEV4 | 3.29 | 1.63 | 0.87 | |||||

| PSEV5 | 3.04 | 1.72 | 0.82 | |||||

| Cues to action (SG) | CUA1 | 3.62 | 1.70 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 2.11 |

| CUA2 | 3.67 | 1.64 | 0.82 | |||||

| CUA3 | 3.32 | 1.63 | 0.90 | |||||

| CUA4 | 3.29 | 1.63 | 0.87 | |||||

| CUA5 | 3.04 | 1.72 | 0.82 | |||||

| CUA6 | 2.72 | 1.48 | 0.90 | |||||

| CUA7 | 2.55 | 1.40 | 0.92 | |||||

| Health motivation | HM1 | 3.58 | 1.86 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 1.22 |

| HM2 | 4.42 | 1.89 | 0.86 | |||||

| HM3 | 3.32 | 1.84 | 0.84 | |||||

| HM4 | 4.65 | 1.72 | 0.74 | |||||

| HM5 | 4.83 | 1.69 | 0.75 | |||||

| HM6 | 3.59 | 1.88 | 0.82 | |||||

| Perceived barriers | PBA1 | 3.58 | 1.86 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 2.33 |

| PBA2 | 4.42 | 1.89 | 0.86 | |||||

| PBA3 | 3.32 | 1.84 | 0.84 | |||||

| Perceived benefit | PBE1 | 3.29 | 1.63 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 2.12 |

| PBE2 | 3.04 | 1.72 | 0.89 | |||||

| PBE3 | 2.72 | 1.48 | 0.78 | |||||

| Attitude | ATT1 | 3.62 | 1.70 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 1.25 |

| ATT2 | 3.67 | 1.64 | 0.82 | |||||

| ATT3 | 3.32 | 1.63 | 0.90 | |||||

| Subjective norm | SUBN1 | 3.91 | 1.75 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 1.13 |

| SUBN2 | 3.22 | 1.60 | 0.89 | |||||

| Perceive behavioural control | PBC1 | 3.29 | 1.63 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |

| PBC2 | 3.04 | 1.72 | 0.89 | |||||

| PBC3 | 2.72 | 1.48 | 0.78 | |||||

| Intention to take COVID-19 vaccine | INT1 | 3.91 | 1.75 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.82 | - |

| INT2 | 3.22 | 1.60 | 0.89 | |||||

| INT3 | 3.66 | 1.73 | 0.88 | |||||

| INT4 | 4.65 | 1.72 | 0.74 |

Table 3.

Discriminant validity Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT).

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived susceptibility | ||||||||||

| 2 | Perceived severity | 0.384 | |||||||||

| 3 | Cues to action | 0.443 | 0.555 | ||||||||

| 4 | Health motivation | 0.311 | 0.302 | 0.443 | |||||||

| 5 | Perceived barriers | 0.665 | 0.380 | 0.361 | 0.554 | ||||||

| 6 | Perceived benefit | 0.420 | 0.508 | 0.321 | 0.687 | 0.334 | |||||

| 7 | Attitude | 0.400 | 0.465 | 0.372 | 0.711 | 0.445 | 0.213 | ||||

| 8 | Subjective norm | 0.384 | 0.384 | 0.389 | 0.384 | 0.384 | 0.432 | 0.443 | |||

| 9 | Perceive behavioural control | 0.311 | 0.343 | 0.311 | 0.311 | 0.311 | 0.384 | 0.432 | 0.332 | ||

| 10 | Intention to take COVID-19 vaccine | 0.645 | 0.643 | 0.611 | 0.689 | 0.606 | 0.311 | 0.545 | 0.556 | 0.443 | |

Structural model

The first thing to ascertain in the structural model is the variance inflation factor (VIF), and we realised none of the VIF values were above 5 (Hair Jr. et al., 2017), signifying that collinearity is not an issue in our model (Nitzl et al., 2016) (See Table 2). We further our analysis by assessing the t-value, path coefficient (β values), effect size (f2), predictive relevance (Q2) and coefficient of determination (R2) (Hair Jr. et al., 2017). To test the relationship among constructs, we used a 5000 resample bootstrapping procedure with a 5% significance level (one-tailed). All results are found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural model results.

| No | Hypothesised relationship | β | t values | Q 2 | f 2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Perceived susceptibility → Intention | 0.011 | 0.954 | 0.001 | Not supported | |

| H2 | Perceived severity → Intention | 0.001 | 0.854 | 0.002 | Not supported | |

| H3 | Perceived benefit → Intention | 0.112 | 0.211 | 0.001 | Not Supported | |

| H4 | Perceived barriers → Intention | –0.398 | 3.484*** | 0.121 | 0.159 | Supported |

| H5 | Cues to action → Intention | 0.512 | 7.055*** | 0.430 | Supported | |

| H6 | Health motivation → Intention | 0.412 | 4.966*** | 0.213 | Supported | |

| H7 | Attitude → Intention | –0.411 | 4.266*** | 0.211 | Not Supported | |

| H8 | Subjective norm → Intention | 0.622 | 8.055*** | 0.530 | Supported | |

| H9 | Perceived behavioural → Control intention | 0.312 | 3.213*** | 0.139 | Supported |

Significant at p < 0.05, ** at p < 0.01, and *** at p < 0.001.

Of the 9-association hypothesised, 5 were supported and 4 were not supported. Specifically, H1 hypothesised that perceived susceptibility is positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. The finding did not support this assumption. H2 proposed a positive link between perceived severity and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and the results did not endorse this hypothesis. Furthermore, in H3 we anticipated a positive association between COVID-19 vaccine benefits and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. However, the results failed to support this hypothesis. In H4, COVID-19 vaccine barrier was hypothesised to negatively predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and our outcome supported this assumption. H5 assumed that cues to action will predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and our finding supported it. H6 proposed a positive link between health motivation and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and our results supported this hypothesis. Furthermore, H7 proposed that attitude will be positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. Contrary to this expectation, a negative and significant association was found and as such the proposed hypothesis was not supported. H8 projected a positive link between subjective norm and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and the result endorsed it. Finally, H9 assumed that perceived behavioural control will positively predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine and our results supported it.

Having assessed the relevance of the association between constructs, we investigated the effect size (f2) and realised the size to range from small to a large effect (Cohen, 1988). We also looked at the predictive relevance (Q2) and found it to be greater than zero indicating a good predictive relevance (Cheah et al., 2018; Hair et al., 2012). Our model explains 52% of the variance in people’s intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. This variance is termed substantial based on the rule of Cohen (1988).

Discussion of findings

Despite the high rate of COVID-19 infection reported in Nigeria, our findings showed some hesitancy in the intention to receive vaccination with only 54.5% of the respondents agreeing to take the vaccine. More than one-third of the participants (35%) are not willing to avail themselves to take the vaccine and 10.1% were undecided. This report is contrary to many recent studies. For example, research carried out in China showed a high rate (90.1%) of COVID-19 acceptance and intake (Wang et al., 2020). There was also a report of a high rate (80%) of vaccine acceptance in Isreal (Shmueli, 2021). A high rate (71.4%) of vaccine acceptance has also been reported in Mozambique an African country (Dula et al., 2021).

With regards to the HBM constructs, we found that susceptibility did not predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among the sampled Nigerian population. This means that Nigerians do not believe that they are at risk of contracting COVID-19 despite reported cases of death in the country. They think they are unlikely to get the virus and as such, there is no need of taking the vaccine. This outcome is contrary to evidence that showed perceived susceptibility to being associated with the intention to take vaccine (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). Perceived susceptibility is a key component of the HBM, which motivate people to accept and change their health behaviour (Oyeoku et al., 2021). Our finding supports a recent study that found that perceived susceptibility to infection was not associated with the acceptance of the vaccine (Wong et al., 2021). The study argued that COVID-19 is perceived as a mild disease unless if the infected person has underlying conditions.

Further findings in this current study suggest that perceived severity had no association with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among the sampled population. This infers that Nigerians do not feel if they get COVID-19 it will be difficult to recover, neither do they believe that complications could come up from contracting the disease. They also believe COVID-19 infection would not be fatal and as such the severity of COVID-19 does not motivate them to take up the vaccine. Evidence has shown that Nigerians have this notion that the virus does not exist in Nigeria, suggesting that it might be present in other parts of the globe but not in the country (Apuke and Omar, 2021a). Others also hold the notion that the virus is politically inclined, and some government officials are only using it to syphon the country’s treasury (Apuke and Omar, 2021b). The result is contrary to research conducted among the Israeli which found that disease severity was associated with the intention to take vaccine, indicating that those who intend to get the vaccine view themselves as being at high risk of suffering or complications if they contract the virus (Shmueli, 2021). Contrary to our outcome, a lot of studies have shown that the fear of COVID-19 predicted vaccine acceptance and intake (Detoc et al., 2020; Gagneux-Brunon et al., 2021).

We anticipated a positive association between COVID-19 vaccine benefits and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. However, the results failed to support this hypothesis. This indicates that the Nigerian population do not believe that the vaccine is beneficial to stop the virus. A possible explanation could be because of the conspiracy theory attached to the vaccine as well as reported cases of death due to some complications on taking the vaccine. For example, research has shown that some Nigerians believe that the vaccine was designed by Bill Gate to inject a microchip to reduce the population of the African continent, however, this rumour was debunked by Bill Gate (Onuora et al., 2021). Our result is contrary to the study of Al-Metwali et al. (2021) conducted in Iraq, which found that the majority of the respondents believe that the vaccine would be effective and would protect them and their families from contracting the virus. A similar outcome has also been reported among the population of China (Lin et al., 2020) and America (Guidry et al., 2021).

Perceived barriers have been negatively linked with the intake of COVID-19 vaccine. For example, research that examine COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in Iraq found that perceived barriers were negatively associated with the vaccine intake (Al-Metwali et al., 2021). The barriers expressed were concerns over the effectiveness of the vaccine, adverse effects, insufficient evidence from clinical trials, storage conditions and widespread misconception over the vaccine. In line with this view, we found that COVID-19 vaccine barrier was negatively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. A possible reason is their doubt over the storage, adverse effect, and efficacy of the vaccine. One study conducted in the United States found adverse effect, safety concerns and fear of needles as the main barriers to vaccine intake (Guidry et al., 2021).

We further found that cues to action predicted the intention to take COVID-19 in Nigeria. This means that if the government and health workers intensify their efforts in convincing the people as well as indicate the essence of the vaccine, the tendency of the population to take the vaccine will increase. Therefore, the chances of the sampled population getting vaccinated will increase if the government, media, WHO, doctors, opinion leaders, friends and family, and workplace recommends it. Similar to our finding, one recent research found cues to action to be one of the strongest predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intake (Shmueli, 2021). A positive link between health motivation and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine was found in this study. This indicates that those who are more moved to keep a healthy lifestyle are more expected to get vaccinated compared to those who do not care much about their health. This is contrary to recent research which showed health motivation not to be significant with health-related behaviour (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2021).

Our finding showed support to two constructs among the three constructs of HBM. Specifically, we proposed that attitude will be positively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. Contrary to our expectation, a negative association was found, indicating that the sampled Nigerian population do not have a positive attitude towards the vaccine, and this affects the vaccine intake intention. They do not feel positive about getting the vaccine, neither do they feel it is beneficial. We feel that it could be as a result of how the Nigerian government has been treating the COVID-19 case in Nigeria, resulting in much-losing interest in the fight of the pandemic (Apuke and Omar, 2021b). Recent research has shown that a positive attitude towards the vaccine predicted the intention to take the vaccine (Guidry et al., 2021).

We found that subjective norm and perceived behavioural control positively predicted the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among our sampled population. This suggests that if their family members, friends, and co-workers think they should take the vaccine, they would likely do so. Furthermore, they believe that the vaccine intake is entirely within their control and this freedom could prompt them to take the vaccine. Similar to our study, Yahaghi et al. (2021) found perceived behavioural control and subjective norm to be significant factors that predict the willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Similarly, Guidry et al. (2021) found that American adults who have higher levels of subjective norms had a more positive attitude towards the intention to get vaccinated of COVID-19. Likewise, research conducted among factory workers in China found that those who had greater perceived behavioural control reported having better willingness to get vaccinated (Zhang et al., 2021). As shown in the study of Lin et al. (2020), when individuals see that a lot of people around them have taken or are willing to take the vaccine, their willingness will increase, suggesting the strong role of subjective norm in persuading people to get vaccinated. However, one recent study showed that subjective norm does not predict the intention to vaccinate, suggesting that the perception of judgement from others does not predict vaccine intake intention (Fan et al., 2021).

Limitations of the study

Despite the many advantages associated with this study, there are few limitations worth mentioning. The study used an online survey and as such limiting the equal chances for respondents to be selected. Future researchers could use a more robust sampling technique to cover a more diverse and dispersed audience. We also encourage future studies to increase the number of participants as we feel our participants may not be too large enough, nevertheless, our model’s variance was substantial, and the findings could be used for policymaking. Further research could add some control variables to see if they will alter the outcome. Furthermore, moderating, and mediating variables could also be introduced to enrich the model.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived COVID-19 vaccine benefits did not predict the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among the sampled Nigerian population. Furthermore, COVID-19 vaccine barrier was negatively associated with the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerians. However, cues to action and health motivation predicted the intention to take COVID-19 in Nigeria. In addition, a negative association was found between attitude and vaccine intake indicating that the sampled Nigerian population do not have a positive attitude towards the vaccine, and this affects the vaccine intake intention. Yet, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control positively predicted the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among our sampled population. These outcomes have implications for theory and practice:

The theoretical and empirical contributions

This is one of the first studies in Nigeria to incorporate the HBM and TPB to investigate factors that predict the intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine. This contributes to recent studies that have incorporated these theories on other populations (Al-Metwali et al., 2021; Shmueli, 2021). Studies in Nigeria have focused more on predicting COVID-19 health behaviour initiation (Gever et al., 2021; Oyeoku et al., 2021), with a limited focus on the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intake (Tobin et al., 2021). So this work contributes to Tobin et al. (2021) study which found age, gender, vaccine manufacturer trust, public health authority trust, and willingness to pay for and travel for a vaccine as significant predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Nigeria.

While Shmueli (2021) found cues to action and perceived benefit to be the strongest predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intake, our study adds health motivation, suggesting that individuals that are concern about their health will be more willing to get vaccinated. While past researches suggest that the TPB construct might not be useful in forecasting the intention to get vaccinated (Dubé et al., 2012; Wiemken et al., 2015), our current research showed that TPB is essential in explaining the reasons for vaccination intake, especially among developing countries such as Nigeria. Subjective norms and perceived behavioural control has been shown not to be associated with vaccine intake (Fan et al., 2021). Our study brings to the fore that subjective norms and perceived behavioural control are a strong predictor of the COVID-19 vaccine in take intention. This contributes to the growing body of studies that have used the TPB (Guidryt et al., 2021; Yahaghi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021) to examine health-related issues.

Practical implication

The outcome of this study has implications for health practice. We call on relevant authorities to increase the risk perception and severity among the Nigerian public, especially those who feel the virus is not dangerous, this is because there are daily records of death in the country. Efforts should be made to create public health intervention programmes that will focus on intensifying the perception of the benefits of the vaccine. As such, a lot of cues to action should be put in place intensifying and publicising the recommendations of government, media, WHO, doctors, opinion leaders, friends and family, and the workplace with regard to the vaccine. The vaccine should also be made readily available to the public to encourage participation, this will decrease the barriers attached to the vaccine intake. With regard to subjective norms, individuals are encouraged to share their positive experiences regarding vaccination with their friends and relatives, such as letting them know where to easily access the vaccine and the time for vaccination. Overall, we call on the Nigerian government and health care workers to intensify their efforts in informing the public of the benefits of taking the vaccine, this might alter their attitude from negative to positive.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jas-10.1177_00219096211069642 for Modelling the Factors That Predict the Intention to Take COVID-19 Vaccine in Nigeria by Oberiri Destiny Apuke and Elif Asude Tunca in Journal of Asian and African Studies

Author biographies

Oberiri Destiny Apuke is a lecturer at the Faculty of Media and Communication, Taraba State University, Jalingo, Nigeria. His research interests include online journalism, social media, gender studies, conflict studies as well as film and media studies. Contact: apukedestiny@gmail.com.

Elif Asude Tunca is a lecturer at the European University of Lefke, Faculty of Communication Sciences, Department of New Media and Journalism, Lefke, Northern Cyprus, Turkey. Contact: etunca@eul.edu.tr

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Oberiri Destiny Apuke  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7657-4858

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7657-4858

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Oberiri Destiny Apuke, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia; Taraba State University, Jalingo, Nigeria.

Elif Asude Tunca, European University of Lefke, Northern Cyprus, Turkey.

References

- Abdollahzadeh G, Sharifzadeh MS. (2021) Predicting farmers’ intention to use PPE for prevent pesticide adverse effects: An examination of the Health Belief Model (HBM). Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 20(1): 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi YA, Alaran AJ, Bolarinwa OA, et al. (2020) When it is available, will we take it? Public perception of hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria. Medrxiv. Epub print of 29October2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.09.24.20200436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (1985) From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J. (eds) Action Control. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, pp.11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50(2): 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. (1975) A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychological Bulletin 82(2): 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Metwali BZ, Al Jumaili AA, Al Alag ZA, et al. (2021) Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 27(5): 1112–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ale V. (2021) A library-based model for explaining information exchange on coronavirus disease in Nigeria. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2(1): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Apuke OD, Omar B. (2021. a) Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telematics and Informatics 56: 101475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apuke OD, Omar B. (2021. b) Television news coverage of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria: Missed opportunities to promote health due to ownership and politics. SAGE Open 11(3): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Barello S, Nania T, Dellafiore F, et al. (2020) ‘Vaccine hesitancy’ among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Epidemiology 35(8): 781–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caycho-Rodríguez T, Tomás JM, Carbajal-León C, et al. (2021) Sociodemographic and psychological predictors of intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in elderly Peruvians. Trends in Psychology. Epub ahead of print 18 August. DOI: 10.1007/s43076-021-00099-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H, Liu S. (2021) Integrating health behavior theories to predict American’s intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Patient Education and Counseling 104(8): 1878–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed.Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, et al. (2020) Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine 38(45): 7002–7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé E, Bettinger JA, Halperin B, et al. (2012) Determinants of parents’ decision to vaccinate their children against rotavirus: Results of a longitudinal study. Health Education Research 27(6): 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dula J, Mulhanga A, Nhanombe A, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine acceptability and its determinants in Mozambique: An online survey. Vaccines 9(8): 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C-W, Chen I-H, Ko N-Y, et al. (2021) Extended theory of planned behavior in explaining the intention to COVID-19 vaccination uptake among mainland Chinese university students: An online survey study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17(10): 3413–3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, et al. (2020) Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Annals of Internal Medicine 173(12): 964–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K, Arim R. (2020) Canadians ‘ willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available : What role does trust play ? Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, et al. (2021) Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Hospital Infection 108: 168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gever VC, Talabi FO, Adelabu O, et al. (2021) Modeling predictors of COVID-19 health behaviour adoption, sustenance and discontinuation among social media users in Nigeria. Telematics and Informatics 60: 101584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, et al. (2021) Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. American Journal of Infection Control 49(2): 137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Sarstedt M. (2019) Factors versus composites: Guidelines for choosing the right structural equation modeling method. Project Management Journal 50(6): 619–624. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. (2012) Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Planning 45(5–6): 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Ringle CM, Gudergan SP, et al. (2019) Partial least squares structural equation modeling-based discrete choice modeling: An illustration in modeling retailer choice. Business Research 12(1): 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr, JF, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, et al. (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1(2): 107. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. (2014) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1): 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Khan GF, Sarstedt M, Shiau WL, et al. (2019) Methodological research on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An analysis based on social network approaches. Internet Research 29(3): 407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. (2021) A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine 27(2): 225–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, et al. (2020) Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14(12): e0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizewski L and Maguire K. (2010) The Health Belief Model. Wayne State University.

- Melugbo DU, Ogbuakanne MU, Jemisenia JO. (2021) Entrepreneurial potential self-assessment in times of COVID-19: Assessing readiness, engagement, motivations and limitations among young adults in Nigeria. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2(1): 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl C, Roldan JL, Cepeda G. (2016) Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management and Data Systems 116(9): 1849–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie GS, Gordon S, Smith LW, et al. (2021) Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: Results from a population-based survey in Canada. BMC Public Health 21(1): 1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olijo II. (2021) Nigerian media and the global race towards developing a COVID-19 vaccine: Do media reports promote contributions from African countries? Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2(1): 65–74 [Google Scholar]

- Onuora C, Torti Obasi N, Ezeah GH, et al. (2021) Effect of dramatized health messages: Modelling predictors of the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. International Sociology 36(1): 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeoku EK, Talabi FO, Oloyede D, et al. (2021) Predicting COVID-19 health behaviour initiation, consistency, interruptions and discontinuation among social media users in Nigeria. Health Promotion International. Epub ahead of print 5July. DOI: 10.1093/heapro/daab059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM, et al. (2016) Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies!. Journal of Business Research 69(10): 3998–4010. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, et al. (2018) The vaccine hesitancy scale: Psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine 36(5): 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli L. (2021) Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health 21(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniehotta FF, Presseau J, Araújo-Soares V. (2014) Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review 8(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin EA, Okonofua M, Adeke A, et al. (2021) Willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria: A population-based cross-sectional study. Central African Journal of Public Health 7(2): 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trogen B, Oshinsky D, Caplan A. (2020) Adverse consequences of rushing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: Implications for public trust. JAMA 323: 2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugwuoke JC, Talabi FO, Adelabu O, et al. (2021) Expanding the boundaries of vaccine discourse: Impact of visual illustrations communication intervention on intention towards COVID-19 vaccination among victims of insecurity in Nigeria. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17(10): 3450–3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, et al. (2020) Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines 8(3): 482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemken TL, Carrico RM, Kelley RR, et al. (2015) Understanding why low-risk patients accept vaccines: A socio-behavioral approach. BMC Research Notes 8(1): 813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, et al. (2021) Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 39(7): 1148–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2021) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation reports. WHO Situation report (Issue 72). Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200324-sitrep-64-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=703b2c40_2%0Ahttps://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200401-sitrep-72-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=3dd8971b_2

- Yahaghi R, Ahmadizade S, Fotuhi R, et al. (2021) Fear of COVID-19 and perceived COVID-19 infectability supplement theory of planned behavior to explain Iranians’ intention to get COVID-19 vaccinated. Vaccines 9(7): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, et al. (2020) Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years: Cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting 3(2): e24827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, et al. (2021) Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: Cross-sectional online survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(3): e24673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jas-10.1177_00219096211069642 for Modelling the Factors That Predict the Intention to Take COVID-19 Vaccine in Nigeria by Oberiri Destiny Apuke and Elif Asude Tunca in Journal of Asian and African Studies