Abstract

Romantic relationship qualities are likely to change from adolescence to adulthood. Therefore, we undertook a longitudinal study to examine changes in satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict over this period by simultaneously testing the effects of age, relationship length, and their interaction. These qualities were measured at nine-time points from ages 16 to 30 in a Canadian sample of 337 participants (62.9% women) who reported being in a romantic relationship at least once over this period. The results of multilevel analyses show that satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict decline with age but increase with relationship length. Moreover, age and relationship length were found to have a significant interactive effect on satisfaction and intimacy.

Keywords: romantic relationship qualities, emerging adulthood, longitudinal, satisfaction, intimacy, conflict, couples, adolescence

Introduction

The quality of the relationship refers to the positive or negative evaluation an individual makes of their interpersonal relationships (Morry et al., 2010). Being in a romantic relationship with positive qualities is associated with well-being in adolescence and emerging adulthood (Gómez-López et al., 2019; Kansky, 2018). Developmental models of romantic relationship qualities spanning adolescence to adulthood argue that as individuals grow older, romantic relationships meet specific and changing emotional and social needs (Brown, 1999; Furman & Wehner, 1994). Thus, these changes in the function of romantic relationships would result in changes in relationship qualities. However, in addition to age, the length of a relationship with the same partner may be associated with the qualities of a romantic relationship (Furman et al., 2019). Regardless of age, romantic partners that have been together a long time do not interact in the same way as those who have been together a short time (Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). Therefore, age and duration must be considered together, as they would reflect different aspects of development (Zimmer-Gembeck & Ducat, 2010). Available research investigating how romantic relationship qualities change over time has simultaneously considered age and relationship length during the first part of emerging adulthood (up to age 25). However, it has focused mainly on the negative qualities of relationships and is limited to young Americans (Lantagne & Furman, 2017). This study aims to fill these gaps by examining the effect of age and relationship length on satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict in romantic relationships in a Canadian sample assessed on nine occasions between adolescence and the beginning of adulthood (up to age 30). Doing so will lead to a better understanding of how romance develops at this time of life and can be used to identify possible objectives for integration into a therapeutic intervention (i.e., individual and couple).

Development of Romantic Relationships from Adolescence to Adulthood

Theories of relationship development have the particularity of focusing on specific and age-circumscribed developmental aspects (adolescence 12–20 years: Brown, 1999; Furman & Wehner, 1994; emerging adulthood 20–29: Shulman & Connolly, 2013; Nelson, 2020, established adulthood 30–45: Mehta et al., 2020). There is, therefore, no universal theory that encompasses all these developmental phases. Brown (1999) and Furman and Wehner (1994), who address adolescence and the first part of emerging adulthood, argue that romantic relationship development is sequential and advances with age. The partner rises in the individual’s social hierarchy and becomes increasingly important. According to these authors, advancing age is associated with a greater commitment to one’s romantic partner, likely impacting the relationship’s quality positively.

Shulman and Connolly (2013) proposed an update to these models to include the period of emerging adulthood (i.e., until the late 20s). As reported by these authors, emerging adults tend to invest more markedly in personal development and certain individual needs, such as work or school, which may interfere with the level of commitment to a long-term relationship. Thus, variations in the quality of romantic relationships can be observed during this period.

According to Arnett (2000), emerging adults can be distinguished from adolescents and established adults because although they have reached majority, they have few responsibilities and greater freedom of choice. Therefore, the emerging adult period would represent the richest developmental phase for opportunities (growth and/or failure) to explore the different aspects of identity, especially on the romantic side. Nelson (2020) specifies that the exploration of identity would represent a focal issue for emerging adults during the first half of their twenties (20–24 years), whereas a more pronounced commitment to identity in the various spheres of life, particularly romantic relationships, would characterize the second half of this decade (25–29). Thus, the qualities of the couple’s relationship are likely to change between the first and second half of their twenties. As they age, the acquisition of specific skills in the context of a romantic relationship could explain this trend. Emerging adults who have developed skills to maintain a satisfying romantic relationship and manage conflicts with their partners will be more likely to have good quality relationships as couples.

Erikson’s psychosocial theory (1968) provides further insights into the developmental tasks present in emerging adulthood that are likely to be associated with the quality of the romantic relationship. First, everyone in this stage of their lives will be confronted with having to resolve an identity crisis (Identity vs. Role Confusion). Then, once an emerging adult has established a coherent and consistent sense of identity, the building of an intimate relationship can become important (Intimacy vs. Isolation). According to Erikson, the stronger each partner’s self-image is, the more likely the couple will develop a successful intimate relationship.

Arnett (1997) maintains that entry into adulthood (age 30) will be marked by accepting responsibilities, a decentring of self, and the desire to start a family. For Mehta et al. (2020), this period is characterized by a “rush-hour life” where the advent of children and a career is highly demanding in terms of energy for most adults (Knecht & Freund, 2016), which often results in lower levels of satisfaction and intimacy between romantic partners and more conflict (Mickelson & Biehle, 2017).

Age and Relationship Length

Aside from age, research on romantic development must also consider relationship length. The length of a relationship is not entirely independent of the individual’s age, as it increases as they get older (Carver et al., 2003). However, given that individuals do not all follow the same romantic trajectory (Boisvert & Poulin, 2016), there is no reason to assume that age-related change is systematically associated with changes in relationship length. Studies have demonstrated that the longer the relationship, the higher the intimacy and commitment in couples (Giordano et al., 2012). Negative qualities, such as jealousy and conflict, also may increase with relationship length (Seiffge-Krenke & Burk, 2013). In short, relationship length is a factor to consider when examining changes in the qualities of a romantic relationship because it reflects time spent with the same partner. Age, on the other hand, may reflect the accumulation of romantic experiences over time (Zimmer-Gembeck & Ducat, 2010). Therefore, a longitudinal design where age and relationship length are examined simultaneously is essential to understand better these two variables’ main and interactive effects on specific relationship qualities.

Lantagne and Furman (2017) simultaneously examined the impact of age, length, and their interaction on different romantic relationship qualities among 200 American participants evaluated at eight-time points from ages 15 to 25. Their results revealed the presence of an age-main effect on jealousy, whereby jealousy diminished with age. In addition, relationship length’s main effects have also been observed: Length was associated with increased support, conflict, controlling behaviors, and jealousy. Finally, the interaction between age and relationship length was significant. Specifically, support increased with age in short relationships. Moreover, conflict and controlling behaviors declined with age in long relationships, and jealousy dropped in medium-length and long relationships as the partners get older. Though the results of the Lantagne and Furman (2017) study clearly illustrated the relevance of examining the interactive effect of age and relationship length on romantic relationship qualities, there are at least three reasons for further pursuing this line of investigation.

First, more longitudinal studies must be conducted with samples that are not American and may differ in romantic behaviors. For example, according to the 2018 U.S. census, the mean age for marriage in the United States was 29.8 years for men and 27.8 years for women (United States Census Bureau, 2018), whereas in Québec (Canada), it was 33.6 and 32 years respectively for the same period (Institut de la Statistique du Québec [ISQ], 2020). Moreover, the mean age of mothers at first birth in the United States in 2014 was 26.3 years (Mathews & Hamilton, 2016), compared to 30.4 years in Québec in the same period (ISQ, 2020). Quebecers tend to commit to forming a family a little later in life than their American counterparts. By 2016, the percentage of unmarried couples living together in Canada rose to 21.3% (Statistique Canada, 2016), whereas for the same year in the United States, it was 7% (Pew Research Center analysis, 2016). These cultural differences could impact how romantic relationship qualities change over time.

Second, changes that may occur in these qualities from the mid-20s until adulthood must also be considered (Nelson, 2020). Major transitions tend to occur from ages 25 to 30, notably in terms of residential independence, marital status, and parenthood. For example, in Québec in 2016, 48.7% of 25-to 29-year-olds lived with a romantic partner, compared with 17.5% of 20- to 24-year-olds (ISQ, 2016). Moreover, in the same period, 51% of 25-to 29-year-olds married or became parents, compared with 19% of 20-to 24-year-olds.

Third, the main focus of the study by Lantagne and Furman (2017) was on the negative qualities of romantic relationships (i.e., negative interactions, controlling behaviors, and jealousy). However, only one positive quality — support — was investigated. Consequently, age and the length of a relationship’s main and interactive effects on other key qualities of romantic relationships, such as satisfaction and intimacy, remain unknown. This last point will be discussed in further detail below.

Change in the Qualities of Romantic Relationships

Regarding positive characteristics, the quality of the romantic relationship was first defined in relation to the couple’s satisfaction (Spanier, 1976). It can be understood as an intrapersonal assessment of the positive effects associated with a romantic relationship. In addition, partner intimacy would also be pivotal to the quality of the romantic relationship, relating as it does to the sharing of thoughts and feelings with one’s partner (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). Regarding negative aspects, behavioral interaction models have identified one, namely, conflict (Fincham & Beach, 1999). Available studies suggest that age and relationship length likely impact these three qualities.

Satisfaction

A longitudinal study by Zimmer-Gembeck and Petherick (2006), spanning ages 17 to 21, showed that romantic relationship satisfaction increased with age. Another longitudinal study by Stafford et al. (2004) with 30-year-olds showed that the longer the relationship, the less satisfied the partners. Other studies have also revealed a significant drop in satisfaction over the first years of marriage (Bradbury & Karney, 2004). Finally, Lavner and Bradbury (2010) identified five marital satisfaction trajectories as a function of relationship length (from 4 months to 4 years). Of the five, four showed a decline in satisfaction, while the other showed no significant change. In summary, it is possible that satisfaction is positively associated with age and negatively associated with length. These two factors would benefit from being examined together in the same study.

Intimacy

Advancing age has been found to be associated with increased intimacy between romantic partners (Giordano et al., 2012). Moreover, various cross-sectional studies (Hurley & Reese-Weber, 2012; Reese-Weber, 2015) and one longitudinal study (Meier & Allen, 2009) have reported a positive link between relationship length and intimacy. This link has also been observed in adolescents (Rostosky et al., 2000). However, other cross-sectional studies have revealed a negative association between relationship length and intimacy (Lemieux & Hale, 2002). Simultaneously examining the unique effect of age, length, and their interaction upon intimacy in a longitudinal design would clarify these discrepancies in the literature.

Conflict

Two longitudinal studies spanning ages 13 to 23 observed more conflict in romantic relationships with age (Johnson et al., 2015; Vujeva & Furman, 2011). However, in the longitudinal study by Robins et al. (2002), conflict diminished from ages 21 to 25, whereas in the one by Chen et al. (2006), it increased over the same period. In addition, Lantagne and Furman (2017) have reported increased conflict as a function of relationship length. Further longitudinal studies are therefore needed to clarify the link between age and conflict in a romantic relationship.

Objective and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to examine changes in satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict in romantic relationships from adolescence to adulthood, taking age and relationship length into account simultaneously. A longitudinal design measured these dimensions at nine-time points from ages 16 to 30. These three dimensions were analyzed separately by examining the effects of age, relationship length, and their interaction. Linear and non-linear (quadratic and cubic) forms of change were also tested. Studies have suggested that cubic or quadratic forms of change might better represent how certain romantic relationship features change by age and relationship length (Chen et al., 2004; Kurdek, 1999). Finally, gender, cohabitation, and parenthood were included as control variables, as these might potentially affect romantic relationship qualities. Research has shown that women are more committed to their romantic partners and tend to perceive a higher degree of intimacy and support than men (Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). Research has also shown that partners who cohabit are at a higher risk of conflict and diminished satisfaction than those who do not (Rhoades et al., 2012). Finally, the transition to parenthood has been associated with a decline in relationship quality and increased conflict (Mickelson & Biehle, 2017).

For satisfaction, we expected advancing age to be associated with increased satisfaction (H1), as reflected in the results of empirical studies (Young et al., 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck & Petherick, 2006). In light of the divergence between linear change trajectories (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010) and non-linear trajectories (Kurdek, 1999), the form of change was examined in an exploratory manner. Relationship length was also anticipated to be associated with diminished satisfaction (H2) (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010). However, given the lack of data on the interactive effect of age and length on satisfaction, no hypothesis was formulated.

For intimacy, we expected advancing age to be associated with increased intimacy (H3), as the form of change in intimacy was examined in an exploratory manner. We also anticipated that longer relationships would be associated with increased intimacy (H4). These hypotheses were based on theoretical models of romantic development (Brown, 1999; Furman & Wehner, 1994) and the results of empirical studies (Giordano et al., 2012; Meier & Allen, 2009). However, no study to date has examined the interactive effect of age and relationship length on this variable, so no hypothesis was formulated.

For conflict, the varied results of empirical studies constrain us from formulating clear hypotheses for the effect of age (Robins et al., 2002; Vujeva & Furman, 2011). However, based on the results of Chen et al. (2006), change in conflict was expected to be cubic in form, that is, a decline at the end of adolescence, an increase in emerging adulthood, and finally, a decline in adulthood (H5). Also, we expected longer relationships to be associated with increased conflict (H6) (Lantagne & Furman, 2017). Finally, based on the study by Lantagne and Furman (2017), we expected the interaction between age and length to affect conflict: Longer relationships were expected to be associated with a decline in conflict with age (H7).

Method

Participants

The data used in our study were collected for a longitudinal study begun in 2001 with a sample of 390 six-graders (58% girls; mean age = 12.38 years, SD = 0.42). The students came from eight elementary schools that reflected different socio-economic levels in a large city. The majority were Caucasian and French-speaking (about 3% Black, 1% Asian, 3% Latino, and 3% Arab). Most were born in Canada (90%) and lived with both biological parents (72%). Mean family pre-tax income stood between $45,000 and $55,000 in 2001. Mothers and fathers had completed approximately the same number of years of schooling (M = 13.10, SD = 2.68 and M = 13.20, SD = 3.20, respectively).

These participants were followed until the age of 30. The retention rate varied from 75% to 83% year to year and stood at 83% at age 30. The 337 participants (62.9% women) who completed the measure of romantic relationship qualities at least once from ages 16 to 30 constituted our study sample. Of the 337 participants, 47 completed the relationship quality measure in one data point, 28 in two, 37 in three, 46 in four, 46 in five, 51 in six, 36 in seven, 31 in eight, and 15 in nine. They did not differ from the rest of the initial sample (n = 53) in terms of parent education, annual family income, gender, and ethnic background.

Design and Procedures

At ages 16 and 17, participants completed questionnaires at school under the supervision of trained research assistants. At ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, and 25, participants completed the questionnaires at home during visits from research assistants. At ages 23, 24, and 26, participants underwent a structured telephone interview administered by trained and supervised research assistants. No data were collected for ages 27, 28, and 29. Finally, at age 30, participants completed an online questionnaire on the LimeSurvey platform. Written consent was obtained from parents when participants were aged 16 and 17. From the age of 18 onward, written consent was obtained directly from participants. A gift certificate or monetary compensation was offered as a token of appreciation at each time point. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Université du Québec à Montréal.

Measures

Romantic Relationship Qualities at Ages 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30

At each time point, participants were asked if they currently had a romantic partner. Those who responded yes were then asked to write down the name of their romantic partner and to complete items from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI) developed by Furman and Buhrmester (1985), with this current partner as the point of reference. They had to indicate how much their relationship with this person corresponded to the items on a five-point Likert scale from 1, “Little or not at all,” to 5, “The most.” Three items measured satisfaction (e.g., “How satisfied are you with your relationship with this person?”; alpha of .92–.97 for all evaluations). Likewise, intimacy (e.g., “How much do you share your secrets and private feelings with this person?”; alpha of .81–.92) and conflict (e.g., “How much do you and this person disagree and quarrel with each other?”; alpha of .85–.93) were each measured by three items. Scores were obtained by calculating the average for the items composing each scale. Furman and Buhrmester (1992) documented the instrument’s reliability and validity with a sample of adolescents and emerging adults.

Length of Romantic Relationship at ages 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30

Each year from ages 16 to 26, participants were invited to indicate whether they currently had a romantic partner. If yes, they had to write down the partner’s full name. At 30, aside from identifying their current partner, participants reported names of their former partners, if any, for each year at ages 27, 28, and 29.

This information was used to calculate the length of a romantic relationship. Length scores were created for each year that the relationship qualities were measured (i.e., ages 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30; qualities were not assessed at ages 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, and 29). These scores were calculated by tallying the number of times the partner was mentioned, including for the current year. For example: (1) if at age 20 the partner mentioned was never mentioned in previous years, the length score was 1; (2) if at age 17 the partner mentioned was also named at age 16, the length score was 2; and (3) if at age 22 the partner mentioned was also named at ages 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21, the length score was 7.

This procedure is based on the study by Rauer et al. (2013), in which participants were asked to name their partner for each year between the ages of 18 and 25. These authors then used this information to calculate the length of romantic relationships (in years). On-and-off romantic relationships (characterized by making up, then breaking up, and then making up again) were rare (n = 4) and were included.

Parenthood at Ages 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30

Parenthood was measured through the following question: “Do you have children of whom you are the biological parent? (yes/no).”

Cohabitation with a Romantic Partner at ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30

Participants had to indicate whether yes/no they lived with their romantic partner.

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

A multilevel analysis made it possible to include participants whose data was missing without needing to change the data (Hox, 2013). The lme4 package in R was used to manage missing data by maximum likelihood (Bates et al., 2015).

Histograms and the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that skewness and kurtosis coefficients fell beyond the normal limit (ceiling effect) for the three dependent variables. As no transformation managed to resolve the non-normality of the data, these variables were dichotomized. Two groups were formed for each variable, a reference group, and a modeled group. The cut-off for intimacy and satisfaction was set at 4 (on a scale of 1–5) to distinguish participants who enjoyed a high level of intimacy (or satisfaction) with their partner (scores of 4 or more; 75% of the sample) from those who enjoyed a lower level (scores less than 4; 25%). For conflict, the cut-off was set at 2 to distinguish participants who experienced little or no conflict (scores of 2 or less; 75% of the sample) from those who experienced more (scores above 2; 25%).

Table 1 gives the raw means and standard deviations for the predictors and qualities of romantic relationships at ages 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, and 30. At 16, 29.1% of participants reported being in a romantic relationship, compared with 76.3% at 30. The mean length of a romantic relationship increased with age.

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Characteristics of Romantic Relationships from Ages 16 to 30.

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 25 | 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants in a romantic rel. (%) | 98 (29.1%) | 125 (37.1%) | 160 (47.5%) | 168 (49.8%) | 165 (49.0%) | 185 (54.9%) | 190 (56.4%) | 223 (66.2%) | 257 (76.3%) |

| Age | 15.54 (0.58) | 16.65 (0.59) | 17.73 (0.58) | 18.59 (0.58) | 19.67 (0.58) | 20.63 (0.58) | 21.55 (0.57) | 24.69 (0.58) | 29.76 (0.55) |

| Relationship length | 1.24 (0.43) | 1.38 (0.67) | 1.63 (0.92) | 1.88 (1.12) | 2.01 (1.21) | 2.38 (1.46) | 2.78 (1.74) | 3.96 (2.62) | 6.46 (3.97) |

| Satisfaction | 4.56 (0.72) | 4.44 (0.75) | 4.48 (0.73) | 4.24 (0.87) | 4.44 (0.77) | 4.43 (0.77) | 4.38 (0.77) | 4.42 (0.77) | 4.15 (0.83) |

| Intimacy | 4.40 (0.84) | 4.31 (0.83) | 4.40 (0.70) | 4.33 (0.82) | 4.45 (0.77) | 4.44 (0.71) | 4.48 (0.75) | 4.43 (0.73) | 4.10 (0.89) |

| Conflict | 1.70 (0.78) | 1.58 (0.66) | 1.67 (0.71) | 1.79 (0.79) | 1.70 (0.71) | 1.62 (0.66) | 1.63 (0.58) | 1.59 (0.69) | 1.57 (0.62) |

| Cohabitation (%) | — | — | 11 (3.5%) | 15 (4.8%) | 30 (9.5%) | 46 (14.6%) | 56 (17.8%) | 133 (42.2%) | 223 (70.8%) |

| Parenthood (%) | — | — | — | 3 (0.9%) | 10 (3.2%) | 14 (4.4%) | 15 (4.8%) | 43 (13.7%) | 129 (40.9%) |

Principal Analyses

The dichotomized scores for each romantic relationship feature obtained at the nine-time points were subjected to multilevel analyses via binomial logistic regressions to test the different hypotheses. A model for each characteristic was tested. Gender, cohabitation, and parenthood were inserted as control variables. The interaction between age and relationship length was then added to the model. Finally, different forms of change were tested: linear, quadratic, and cubic. The main and interactive effects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multilevel Analysis of Level of Characteristics of Romantic Relationship.

| Predictors | Satisfaction | Intimacy | Conflict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (B0) | 8.71 (0.00) | 13.36 (0.00) | 1.43 (0.70) |

| Gender (γ01) | 1.29 (0.25) | 0.81 (0.34) | 1.41 (0.33) |

| Cohabitation (β2) | 0.72 (0.16) | 0.79 (0.30) | 1.00 (0.99) |

| Parenthood (β3) | 1.05 (0.85) | 1.05 (0.87) | 2.41 (0.02)* |

| Age (β4) | 0.93 (0.01)* | 0.90 (0.00)** | 1.17 (0.00)** |

| Age2 (β5) | — | 0.99 (0.00)** | — |

| Length (β6) | 1.16 (0.04)* | 1.19 (0.02)* | 0.84 (0.06)∼ |

| Age X length (β7) | 0.98 (0.01)* | 0.98 (0.02)* | 1.01 (0.51) |

p ∼ < .07 * p < .05. **p < .01.

Satisfaction

Age and relationship length were found to have significant main effects on satisfaction. Satisfaction declined with age (H1). However, satisfaction increased with relationship length (H2). No significant gender, cohabitation, or parenting effect was observed.

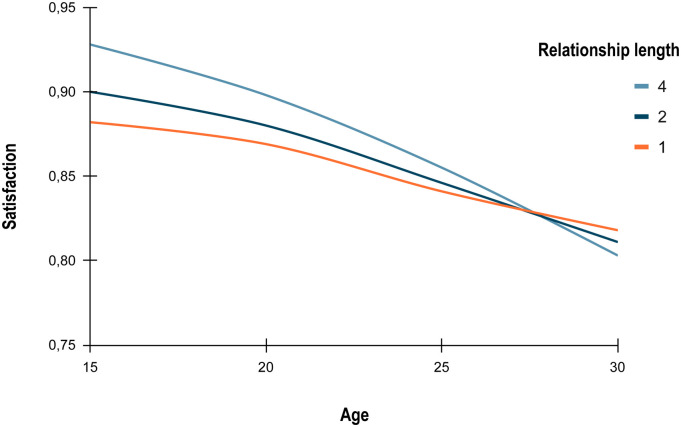

The interaction between age and relationship length was found to have an effect on satisfaction. To interpret the effect, three relationship lengths were defined. The age effect was thus examined by short length (1 year), medium length (2 years), and long length (4 years). These were set based on percentiles: 1 year = 25th percentile; 2 years = 50th percentile; and 4 years = 75th percentile (see Lantagne & Furman, 2017). The use of percentiles is usually recommended when data are not normally distributed. As illustrated in Figure 1, the likelihood of being in the satisfied group only declined significantly in long relationships (4 years) at ages 16 to 21.5, b = −.02, t (1161) = −2.38, p = .01. The Johnson-Neyman test showed the length effect to be significant only below age 21.57 years. The level of satisfaction did not change in short-and medium-length relationships.

Figure 1.

Interactive effect of age and relationship length on satisfaction scores.

Another way to parse the interactive effects on satisfaction was to examine how the length effect varied by age. The length effects were examined at three different ages, namely, at 18 (25th percentile), 20 (50th percentile), and 22 (75th percentile). Regarding satisfaction, the likelihood of being in the satisfied group increased significantly at ages 18 and 20 when romantic relationship length was longer than 2.19 years. However, by age 22, the length effect was no longer significant.

Intimacy

Age and relationship length were found to have significant main effects on intimacy. Intimacy declined with age (H3). The form of change that best represented the data for intimacy was quadratic, owing to an accelerated phase of change, namely, a marked decline in the degree of intimacy from ages 25 to 30. Moreover, intimacy increased with relationship length (H4). No significant gender, cohabitation, or parenting effect was observed.

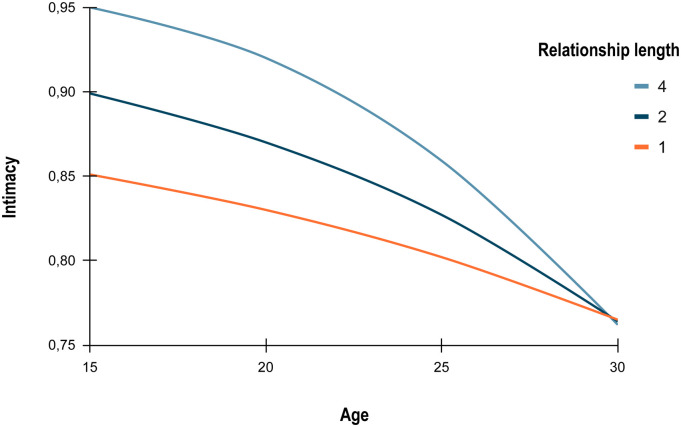

The interaction between age and relationship length was found to have an effect on intimacy. The method of interpretation was the same as for satisfaction. As illustrated in Figure 2, the likelihood of being in the intimate group declined significantly only in medium-length relationships (2 years) and long relationships (4 years) at ages 16 to 24.5, b = −.02, t (1161) = −2.21, p = .02. The Johnson-Neyman test showed the length effect to be significant only when age was below 24.5 years. Intimacy did not change in short romantic relationships.

Figure 2.

Interactive effect of age and relationship length on intimacy scores.

Another way to decode the interaction was by examining the effect of duration as a function of age. Regarding intimacy, the likelihood of being in the intimate group increased significantly at all ages, that is, at ages 18, 20, and 22. However, the age effect proved significant only when the relationship length exceeded 1.1 years.

Conflict

Age and relationship length were found to have significant main effects on conflict. Conflict declined with age. A linear form of change best represented the data for conflict (H5), and a marginal effect was observed: Conflict increased with relationship length (H6). A parenthood main effect proved significant as well: Being a parent increased the likelihood of experiencing conflict. No significant gender or cohabitation effect was observed. Furthermore, it was found that there was no interaction between age and length (H7).

Discussion

We examined changes in satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict in a romantic relationship from adolescence to the end of emerging adulthood, taking into account age and relationship length simultaneously. Overall, the results show that satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict decline with advancing age but increase with relationship length. Moreover, the interaction between age and relationship length was found to have a significant effect on satisfaction and intimacy. These findings are consistent with developmental theories that underscore the presence of identity issues in emerging adulthood and their impact on romantic relationships (Arnett, 2000; Nelson, 2020; Shulman & Connolly, 2013).

Satisfaction

Results concerning satisfaction were the inverse of what was expected: Satisfaction tended to decline with age (H1) but increased with relationship length (H2). Changes in romantic satisfaction had a linear form, that is, following a steady decline over time, which is consistent with the results of other studies (Karney & Bradbury, 1997). Although Kurdek (1999) observed a cubic change trajectory, this could be due to differences in the age groups considered (30–40 vs. 16–30) and in the measures used (quality of marriage vs. romantic satisfaction).

The decline in satisfaction as a function of age could be attributable to certain factors external to the couple, such as stress related to searching for work, dealing with financial difficulties, pursuing higher education, and leaving the parents’ home (Randall & Bodenmann, 2017). Moreover, a change in romantic satisfaction is “stochastic”, which is to say that it is strongly influenced by factors proximal to the couple (Young et al., 2011). The decrease in satisfaction with advancing age can also be understood by the “sliding versus deciding” theory proposed by Stanley et al. (2006). Partners who tend to rush through the stages of relationship development (cohabitation, marriage, etc.) are at risk of “sliding” into an unsatisfying romantic relationship. Nelson (2020) argues that this “sliding” phenomenon is an issue that characterizes the period of emerging adulthood. Finally, certain personal characteristics such as an insecure attachment pattern (Collins et al., 2002; Meyer et al., 2015), a high degree of neuroticism (Schaffhuser et al., 2014) or borderline personality traits (Howard et al., 2022), could interfere with the development of a satisfying relationship with age.

The positive link between relationship length and satisfaction might be explained by the complicity between partners and better knowledge of the partner, which refers to the concept of a couple’s friendship (Gottman et al., 2002). In long-term couples, romantic satisfaction has also been associated with the presence of “positivity resonance” between partners, defined as a sharing of positive emotions and a sense of emotional attachment (Otero et al., 2020). Humor is one example of shared positive emotions associated with relationship maintenance (Haas & Stafford, 2005). Hall (2013) demonstrated that humor was related to satisfaction in longer relationships as it created a general atmosphere of fun and reinforced the mutual tie between partners. It is also possible that, as the relationship develops over time, partners set common future objectives (Gottman & Gottman, 2017).

A significant interaction between age and relationship length showed that the likelihood of satisfying relationships diminished only in long relationships (4 years) from ages 16 to 21.5. A similar result was obtained for intimacy: It diminished in medium-length (2) and long relationships from ages 16–24.5 years. At least two explanations can be put forth to account for these two findings. First, this is a period of life characterized essentially by identity exploration (Arnett, 2000). Consistent with Erikson’s theory (1968), it is possible that partners who have not developed a sufficiently integrated and solid self-identity experience problems with intimacy in their romantic relationships. In this respect, the non-resolution of identity in emerging adults can be an issue that hinders the satisfaction and intimacy of the couple. Second, from Nelson’s perspective (2020), the decline of these two qualities in longer relationships from the end of adolescence to the mid-20s may represent the need for emerging adults to explore their personal and couple identities further. Moreover, Zimmer-Gembeck and Petherick (2006) showed that the most satisfied couples were those that had explored and defined their identities more, were more committed professionally, had set clear goals in the romantic sphere, and, consequently, were able to share a similar vision of the couple.

Intimacy

Contrary to expectations, the older the participants got, the less intimacy they reported in their romantic relationship (H3). Change in intimacy had a quadratic form marked by a more pronounced decline from ages 25 to 30. This finding could be explained by the concept of “career-and-care-crunch” proposed by Mehta et al. (2020). This notion underscores an increase in professional and family responsibilities in established adulthood that can translate into more demanding roles at work (Day et al., 2012) and new obligations related, for example, to child-care, home ownership, and aging parents. In other words, around the age of 30, individuals are called upon to face a host of demands external to the couple, which can cut into the time and energy that the couple could otherwise invest. It could also be that a decline in intimacy at this stage in life corresponds to the tendency of the Québec population to form families at an older age. This finding clearly illustrates the relevance of extending the investigation of change in romantic relationship qualities to the early 30s. Moreover, the divergence between our findings and those reported in other works (Giordano et al., 2012) might be attributable to how intimacy is operationalized in romantic relationships. In our study, intimacy referred essentially to a form of self-disclosure (sharing of thoughts; Buhrmester & Furman, 1987), whereas in other studies, it has included the expression of intimacy (exchange of romantic feelings; Hurley & Reese-Weber, 2012) and underlying dimensions (love, commitment; Solomon & Knobloch, 2004).

The hypothesis that intimacy would increase with relationship length was confirmed (H4). This increase might reflect better knowledge of one’s partner and the development of complicity in the dyad. Perhaps also, over time, the participants acquired a sense of confidence and became more genuine about their way of being in a relationship and the content of conversations. In this regard, a longer romantic relationship might lead individuals to experience a sense of security about the couple and consider one’s partner as the primary figure in meeting the need for intimacy (Murray et al., 2006).

Conflict

Older age was associated with a linear decline in conflict. Contrary to expectations, the cubic effect did not prove significant (H5). It should be noted that the study on which this hypothesis rested (Chen et al., 2006) used retrospective data.

Adolescents and young emerging adults (early twenties) are focused more on their own needs (Nelson, 2020) and place greater importance on self-fulfillment, which might explain the higher frequency of conflict in romantic relationships during this period (Argyle & Furnham, 1983). It is also possible that, with age, individuals develop better conflict-resolution strategies that allow them to ease tensions within the couple (Smith et al., 2009). Laursen et al. (2001) showed that, unlike adolescents, emerging adults tended to resolve conflicts with their romantic partners more through negotiation strategies than through coercion or some form of disengagement.

As expected, relationship length was related to more conflict (H6). Lantagne and Furman (2017) observed the same phenomenon. Interdependence theory (Braiker & Kelley, 1979) might provide a line of approach to explain this. The longer that individuals are involved in a romantic relationship, the more likely they will become emotionally, materially, and financially dependent on one another. Should an imbalance occur between the need for independence and dependence within the couple’s dynamics, this could represent a potential source of conflict in partners with a longer commitment to a relationship. It is also possible that the increase in conflict as the relationship develops is associated with individual variables, such as the presence of negative relationship attributions and enduring vulnerabilities. (i.e., hostility and depression) (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall et al., 2011).

Contrary to expectations, age and relationship length did not have an interactive effect on conflict (H7). These results contrast with those of Lantagne and Furman (2017), who noted that conflict declined in long relationships with age. These authors might have detected this interaction because they used a more complete measure of conflict that included six items of the NRI related to conflict and antagonism, in addition to conducting an interview that examined conflict frequency and intensity. This divergence of results could also be due to the use of designs covering different age spans.

Though it was only a control variable in our study, parenthood increased the likelihood of the couple experiencing conflict. This result is consistent with what others reported previously. Becoming parents requires adjustments on the part of both partners and can generate stress (Vismara et al., 2016). Finally, this change can also bring about a deterioration in lifestyle and a loss of sexual intimacy and can increase the risk of developing a vulnerability to psychological disorders (Epifanio et al., 2015). Also, a drop in intimacy and satisfaction has been frequently observed following this transition (Mickelson & Biehle, 2017), but this was not the case in our study. It may be that the absence of a significant effect on these two variables was due to the lack of data on the number of children per household (Meyer et al., 2016).

Strengths and Limitations

Our study’s strengths merit underscoring. First, the longitudinal design comprised nine-time points that spanned mid-adolescence to adulthood (ages 16–30). This allows us to distinguish between certain issues faced by couples that present at distinct stages of development. Second, the simultaneous examination of age and length shed fresh light on the main effect of these variables and their interaction on the three core qualities of romantic relationships.

Some limitations need to be highlighted as well. First, while dichotomizing the dependent variables allowed us to resolve the problem of normality, this technique reduced variability. Second, the fact that relationship qualities were not measured from ages 26 to 29 limited our examination of the form that change can take in the late twenties. Third, only one of the two partners’ viewpoints was considered; as romantic relationships are a dyadic relational matter, we would also stand to gain from considering the perceptions of the other partner. Fourth, the partner’s age was not considered in the analyses, although research shows that an age difference within a couple during this developmental period is not related to relationship quality (Lehmiller & Agnew, 2008). Finally, only a few relationship qualities were assessed in this study, and others should also be investigated in future research, as well as factors that could contribute to individual differences in change over time for these qualities.

Practical Implications

In light of these results, it is important that therapists address the characteristics pertaining to the period of emerging adulthood when evaluating relational difficulties in the context of a romantic relationship. In particular, it would be valuable to highlight during psychological follow-up sessions the perception of each partner’s personal and relational identity, either qualitatively or quantitatively, for example, by administering the questionnaire on aspects of identity (i.e., AIQ-IV) (Yin & Etilé, 2019). This step could provide a more in-depth clinical understanding of the nature of couple issues and subsequently guide interventions with dyads. Furthermore, the highlighted conclusions concerning the effect of age and duration on the degree of satisfaction, intimacy, and conflict in the romantic relationship could serve as guidelines for various professionals (psychoeducators, sexologists, psychiatrists, and social workers) in providing psychological education to this clientele.

Conclusion

Our study contributes new elements to the understanding of change in the qualities of romantic relationships from mid-adolescence to the beginning of established adulthood. By using a multilevel analysis, we were able to identify the interactive effects of age and relationship length on the satisfaction and intimacy of couples. This constitutes a novel element in this literature. Moreover, our results highlight the dynamic nature of romantic relationships (Furman et al., 2019) as they show that the effects of relationship length on a couple’s satisfaction and intimacy depend on the age of the individuals and, inversely, the age effect on these two qualities depends on relationship length.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Satisfaction, Intimacy and Conflict in Canadian Couples: An Analysis of Change from Adolescence to Adulthood by Maude Raymond and François Poulin in Emerging Adulthood

Author Biographies

Maude Raymond is currently a Doctoral Student in Psychology (Psy.D.) at Université du Québec à Montréal. Her research interests include romantic relationships, adolescence/emerging adulthood, and developmental psychology.

François Poulin has completed a PhD Degree in Developmental Psychology at Université Laval and Postdoctoral Studies at the Oregon Social Learning Center. He is a Full Professor at Université du Québec à Montréal. His research interests include parent/peer/romantic relationships,organized activities, and problem behaviors.

Authors’ Note: This form is based on a template provided by the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/5fndw/.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Fonds Québécois pour la Recherche sur la Société et la Culture and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Open Pratice: The raw data are not openly available due to privacy restrictions. (Question 1). The analysis code/syntax are note openly available for download. (Question 2). We don’t use qualitative analyses. (Question 3). The materials used in the study are not openly available for download. (Question 4). This study did not include a pre-registration plan for data collection and/or analysis, This study did not include a pre-registration plan for data collection and/or analysis. (Question 5).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Maude Raymond https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1818-7945

References

- Argyle M., Furnham A. (1983). Sources of satisfaction and conflict in long-term relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(3), 481–493. 10.2307/351654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (1997). Young people’s conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth and Society, 29(1), 3–23. 10.1177/0044118X97029001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert S., Poulin F. (2016). Romantic relationship patterns from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Associations with family and peer experiences in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(5), 945–958. 10.1007/s10964-016-0435-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T. N., Karney B. R. (2004). Understanding and altering the longitudinal course of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 862–879. 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braiker H. B., Kelley H. H. (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships. In Burgess R., Huston T. (Eds.). Social exchange in developing relationships (pp. 135–168). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. B. (1999). “You’re going out with who?” Peer group influences on adolescent romantic relationships. In Furman W., Brown B. B., Feiring C. (Eds.). The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 291–329). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D., Furman W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58(4), 1101–1113. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/1130550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K., Joyner K., Udry J. R. (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In Florsheim P. (Ed.). Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 23–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cohen P., Johnson J. G., Kasen S., Sneed J. R., Crawford T. N. (2004). Adolescent personality disorders and conflict with romantic partners during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(6), 507–525. 10.1521/pedi.18.6.507.54794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cohen P., Kasen S., Johnson J. G., Ehrensaft M., Gordon K. (2006). Predicting conflict within romantic relationships during the transition to adulthood. Personal Relationships, 13(4), 411–427. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00127.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N. L., Cooper L. M., Albino A., Allard L. (2002). Psychosocial vulnerability from adolescence to adulthood: A prospective study of attachment style differences in relationship functioning and partner choice. Journal of Personality, 70(6), 965–1008. 10.1111/1467-6494.05029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day D. V., Harrison M. M., Halpin S. M. (2012). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity, and expertise. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203809525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epifanio M. S., Genna V., De Luca C., Roccella M., La Grutta S. (2015). Paternal and maternal transition to parenthood: The risk of postpartum depression and parenting stress. Pediatric Reports, 7(2), 5872–5881. 10.4081/pr.2015.5872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F. D., Beach S. R. H. (1999). Conflict in marriage: Implications for working with couples. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 47–77. 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W., Buhrmester D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W., Buhrmester D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63(1), 103–115. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W., Collibee C., Lantagne A., Golden R. L. (2019). Making movies instead of taking snapshots: Studying change in youth’s romantic relationships. Child Development Perspectives, 13(3), 135–140. 10.1111/cdep.12325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W., Wehner E. A. (1994). Romantic views: Toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In Montemayor R., Adams G. R., Gullotta T. P. (Eds.). Personal relationships during adolescence (pp. 168–195). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano P. C., Manning W. D., Longmore M. A., Flanigan C. M. (2012). Developmental shifts in the character of romantic and sexual relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. In Booth A., Brown S., Lansdale N., Manning W., McHale S. (Eds.). Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 133–164). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-López M., Viejo C., Ortega-Ruiz R. (2019). Psychological well-being during adolescence: Stability and association with romantic relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1772. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J., Gottman J. (2017). The natural principles of love. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 9(1), 7–26. 10.1111/jftr.12182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J. M., Driver J., Tabares A. (2002). Building the sound marital house: An empirically derived couple therapy. In Gurman A. S., Jacobson N. S. (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (3rd ed.) (pp. 373–399). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. M., Stafford L. (2005). Maintenance behaviors in same-sex and marital relationships: A matched sample comparison. The Journal of Family Communication, 5(1), 43–60. 10.1207/s15327698jfc0501_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A. (2013). Humor in long-term romantic relationships: The association of general humor styles and relationship-specific functions with relationship satisfaction. Western Journal of Communication, 77(3), 272–292. 10.1080/10570314.2012.757796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard K. P., Lazarus S. A., Cheavens J. S. (2022). A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relationship between borderline personality features and interpersonal relationship quality. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 13(1), 3–11. 10.1037/per0000484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. J. (2013). Multilevel regression and multilevel structural equation modeling. In Little T. D. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods: Statistical analysis (vol. 2, pp. 281–294). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley L., Reese-Weber M. (2012). Conflict strategies and intimacy: Variations by romantic relationship development and gender. Interpersonal. An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 6(2), 200–210. 10.5964/ijpr.v6i2.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institut de la Statistique du Québec (2016). Répartition de la population de 15 ans et plus selon la situation conjugale, le groupe d’âge et le sexe, Québec, 2016. https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/document/situation-de-couple-au-quebec/tableau/repartition-de-la-population-de-15-ans-et-plus-selon-la-situation-conjugale-le-groupe-dage-et-le-sexe-quebec-2016 [Google Scholar]

- Institut de la Statistique du Québec (2020). Regard statistique sur la jeunesse. État et évolution de la situation des Québécois âgés de 15 à 29 ans, 1996 à 2018. Édition 2019, mise à jour. https://statistique.quebec.ca/en/fichier/regard-statistique-sur-la-jeunesse-etat-et-evolution-de-la-situation-des-quebecois-ages-de-15-a-29-ans-1996-a-2018-edition-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W. L., Manning W. D., Giordano P. C., Longmore M. A. (2015). Relationship context and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 631–636. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansky J. (2018). What’s love got to do with it? Romantic relationships and well-being. In Diener E., Oishi S., Tay L. (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 1–24). DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Karney B. R., Bradbury T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney B. R., Bradbury T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), 1075–1092. 10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht M., Freund A. M. (2016). Boundary management: A time sampling study on managing work and private life in middle adulthood. Research in Human Development, 13(4), 297–311. 10.1080/15427609.2016.1234307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek L. A. (1999). The nature and predictors of the trajectory of change in marital quality for husbands and wives over the first 10 years of marriage. Developmental Psychology, 35(5), 1283–1296. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantagne A., Furman W. (2017). Romantic relationship development: The interplay between age and relationship length. Developmental Psychology, 53(9), 1738–1749. 10.1037/dev0000363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B., Finkelstein B. D., Betts N. T. (2001). A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review, 21(4), 423–449. 10.1006/drev.2000.0531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner J. A., Bradbury T. N. (2010). Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1171–1187. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmiller J. J., Agnew C. R. (2008). Commitment in age-gap heterosexual relationships: A test of evolutionary and socio-cultural predictions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(1), 74–82. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00408.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux R., Hale J. L. (2002). Cross-sectional analysis of intimacy, passion, and commitment: Testing the assumptions of the triangular theory of love. Psychological Reports, 90(3 Pt 1), 1009–1014. 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall A. D., Jones D. E., Feinberg M. E. (2011). Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: An integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 709–718. 10.1037/a0025279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews T. J., Hamilton B.E. (2016). Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000-2014. NCHS Data Brief, 232, 1–8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db232.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta C. M., Arnett J. J., Palmer C. G., Nelson L. J. (2020). Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. American Psychologist, 75(4), 431–444. 10.1037/amp0000600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A., Allen G. (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. The Sociological Quarterly, 50(2), 308–335. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Robinson B., Cohn A., Gildenblatt L., Barkley S. (2016). The possible trajectory of relationship satisfaction across the longevity of a romantic partnership: Is there a golden age of parenting? The Family Journal, 24(4), 344–350. 10.1177/1066480716670141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. D., Jones M., Rorer A., Maxwell K. (2015). Examining the associations among attachment, affective state, and romantic relationship quality. The Family Journal, 23(1), 18–25. 10.1177/1066480714547698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson K. D., Biehle S. N. (2017). Gender and the transition to parenthood: Introduction to the special issue. Sex Roles, 76(5–6), 271–275. 10.1007/s11199-016-0724-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morry M. M., Reich T., Kito M. (2010). How do I see you relative to myself? Relationship quality as a predictor of self-and partner-enhancement within cross-sex friendships, dating relationships, and marriages. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(4), 369–392. 10.1080/00224540903365471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. L., Holmes J. G., Collins N. L. (2006). Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 641–666. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L. J. (2020). The theory of emerging adulthood 20 years later: A look at where it has taken us, what we know now, and where we need to go. Emerging Adulthood, 9(3), 179–188. 10.1177/2167696820950884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otero M. C., Wells J. L., Chen K. H., Brown C. L., Connelly D. E., Levenson R. W., Fredrickson B. L. (2020). Behavioral indices of positivity resonance associated with long-term marital satisfaction. Emotion, 20(7), 1225–1233. 10.1037/emo0000634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center analysis (2016). Current population survey, annual social and economic supplement (IPUMS). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/06/number-of-u-s-adults-cohabiting-with-a-partner-continues-to-rise-especially-among-those-50-and-older/ [Google Scholar]

- Randall A. K., Bodenmann G. (2017). Stress and its associations with relationship satisfaction. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 96–106. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer A. J., Pettit G. S., Lansford J. E., Bates J. E., Dodge K. A. (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2159–2171. 10.1037/a0031845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese-Weber M. (2015). Intimacy, communication, and aggressive behaviors: Variations by phases of romantic relationship development. Personal Relationships, 22(2), 204–215. 10.1111/pere.12074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades G. K., Stanley S. M., Markman H. J. (2012). The impact of the transition to cohabitation on relationship functioning: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 348–358. 10.1037/a0028316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins R. W., Caspi A., Moffitt T. E. (2002). It’s not just who you’re with, it’s who you are: Personality and relationship experiences across multiple relationships. Journal of Personality, 70(6), 925–964. 10.1111/1467-6494.05028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky S. S., Galliher R. V., Welsh D. P., Kawaguchi M. C. (2000). Sexual behaviors and relationship qualities in late adolescent couples. Journal of Adolescence, 23(5), 583–597. 10.1006/jado.2000.0345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhuser K., Allemand M., Martin M. (2014). Personality traits and relationship satisfaction in intimate couples: Three perspectives on personality. European Journal of Personality, 28(2), 120–133. 10.1002/per.1948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. (2003). Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 519–531. 10.1080/01650250344000145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I., Burk W. J. (2013). Friends or lovers? Person- and variable-oriented perspectives on dyadic similarity in adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(6), 711–733. 10.1177/0265407512467562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S., Connolly J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. 10.1177/2167696812467330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Berg C. A., Florsheim P., Uchino B. N., Pearce G., Hawkins M., Henry N. J. M., Beveridge R. M., Skinner M. A., Olsen-Cerny C. (2009). Conflict and collaboration in middle-aged and older couples: I. Age differences in agency and communion during marital interaction. Psychology and Aging, 24(2), 259–273. 10.1037/a0015609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D. H., Knobloch L. K. (2004). A model of relational turbulence: The role of intimacy, relational uncertainty, and interference from partners in appraisals of irritations. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(6), 795–816. 10.1177/0265407504047838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15–28. 10.2307/350547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L., Kline S. L., Rankin C. T. (2004). Married individuals, cohabiters, and cohabiters who marry: A longitudinal study of relational and individual well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(2), 231–248. 10.1177/0265407504041385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. M., Rhoades G. K., Markman H. J. (2006). Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 55(4), 499–509. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statistique Canada (2016). Recensement de la population, 1981, 2016 et 2021 [Fichier de données et manuel de codes]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220713/t001b-fra.htm [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2018). U.S. Census Bureau releases 2018 families and living arrangements tables. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/families.html [Google Scholar]

- Vismara L., Rollè L., Agostini F., Sechi C., Fenaroli V., Molgora S., Neri E., Prino L. E., Odorisio F., Trovato A., Polizzi C., Brustia P., Lucarelli L., Monti F., Saita E., Tambelli R. (2016). Perinatal parenting stress, anxiety, and depression outcomes in first-time mothers and fathers: A 3- to 6-months postpartum follow-up study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 938. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujeva H. M., Furman W. (2011). Depressive symptoms and romantic relationship qualities from adolescence through emerging adulthood: A longitudinal examination of influences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(1), 123–135. 10.1080/15374416.2011.533414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R., Etilé F. (2019). Measuring identity orientations for understanding preferences: A French validation of the aspects-of-identity questionnaire. Revue Économique, 70(6), 1053–1077. 10.3917/reco.706.1053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young B. J., Furman W., Laursen B. (2011). Models of change and continuity in romantic experiences. In Finchman F. D., Cui M. (Eds.), Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (pp. 44–66). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck M. J., Ducat W. (2010). Positive and negative romantic relationship quality: Age, familiarity, attachment and well-being as correlates of couple agreement and projection. Journal of Adolescence, 33(6), 879–890. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck M. J., Petherick J. (2006). Intimacy dating goals and relationship satisfaction during adolescence and emerging adulthood: Identity formation, age and sex as moderators. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(2), 167–177. 10.1177/0165025406063636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Satisfaction, Intimacy and Conflict in Canadian Couples: An Analysis of Change from Adolescence to Adulthood by Maude Raymond and François Poulin in Emerging Adulthood