Abstract

Background

Class size reductions in general education are some of the most researched educational interventions in social science, yet researchers have not reached any final conclusions regarding their effects. While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce, even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. These students compose a highly diverse group in terms of diagnoses, functional levels, and support needs, but they share a common need for special educational accommodations, which often entails additional instructional support in smaller units than what is normally provided in general education. At this point, there is however a lack of clarity as to the effects of special education class sizes on student academic achievement and socioemotional development. Inevitably, such lack of clarity is an obstacle for special educators and policymakers trying to make informed decisions. This highlights the policy relevance of the current systematic review, in which we sought to examine the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of children with special educational needs.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to uncover and synthesise data from studies to assess the impact of small class sizes on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of students with special educational needs. We also aimed to investigate the extent to which the effects differed among subgroups of students. Finally, we planned to perform a qualitative exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education.

Search Methods

Relevant studies were identified through electronic searches in bibliographic databases, searches in grey literature resources, searches using Internet search engines, hand‐searches of specific targeted journals, and citation‐tracking. The following bibliographic databases were searched in April 2021: ERIC (EBSCO‐host), Academic Search Premier (EBSCO‐host), EconLit (EBSCO‐host), APA PsycINFO (EBSCO‐host), SocINDEX (EBSCO‐host), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), and Web of Science (Clarivate, Science Citation Index Expanded & Social Sciences Citation Index). EBSCO OPEN Dissertations was also searched in April 2021, while the remaining searches for grey literature, hand‐searches in key journals, and citation‐tracking took place between January and May 2022.

Selection Criteria

The intervention in this review was a small special education class size. Eligible quantitative study designs were studies that used a well‐defined control or comparison group, that is, studies where there was a comparison between students in smaller classes and students in larger classes. Children with special educational needs in grades K‐12 (or the equivalent in European countries) in special education were eligible. In addition to exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education from a quantitative perspective, we aimed to gain insight into the lived experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education contexts, as they are presented in the qualitative research literature. The review therefore also included all types of empirical qualitative studies that collected primary data and provided descriptions of main methodological issues such as selection of informants, data collection procedures, and type of data analysis. Eligible qualitative study designs included but were not limited to studies using ethnographic observation or field work formats, or qualitative interview techniques applied to individual or focus group conversations.

Data Collection and Analysis

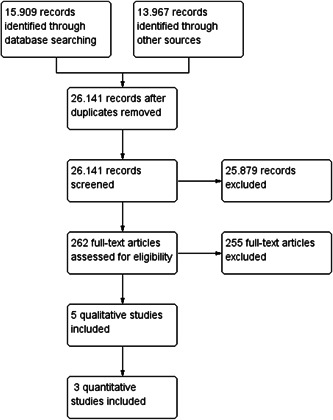

The literature search yielded a total of 26,141 records which were screened for eligibility based on title and abstract. From these, 262 potentially relevant records were retrieved and screened in full text, resulting in seven studies being included: three quantitative and five qualitative studies (one study contained both eligible quantitative and qualitative data). Two of the quantitative studies could not be used in the data synthesis as they were judged to have a critical risk of bias and, in accordance with the protocol, were excluded from the meta‐analysis on the basis that they would be more likely to mislead than inform. The third quantitative study did not provide enough information enabling us to calculate an effect size and standard error. Meta‐analysis was therefore not possible. Following quality appraisal of the qualitative studies, three qualitative studies were judged to be of sufficient methodological quality. It was not possible to perform a qualitative thematic synthesis since in two of these studies, findings particular to special education class size were scarce. Therefore, only descriptive data extraction could be performed.

Main Results

Despite the comprehensive searches, the present review only included seven studies published between 1926 and 2020. Two studies were purely quantitative (Forness, 1985; Metzner, 1926) and from the U.S. Four studies used qualitative methodology (Gottlieb, 1997; Huang, 2020; Keith, 1993; Prunty, 2012) and were from the US (2), China (1), and Ireland (1). One study, MAGI Educational Services (1995), contained both eligible quantitative and qualitative data and was from the U.S.

Authors' Conclusions

The major finding of the present review was that there were virtually no contemporary quantitative studies exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education, thus making it impossible to perform a meta‐analysis. More research is therefore thoroughly needed. Findings from the summary of included qualitative studies reflected that to the special education students and staff members participating in these studies, smaller class sizes were the preferred option because they allowed for more individualised instruction time and increased teacher attention to students' diverse needs. It should be noted that these studies were few in number and took place in very diverse contexts and across a large time span. There is a need for more qualitative research into the views and experiences of teachers, parents, and school administrators with special education class sizes in different local contexts and across various provision models. But most importantly, future research should strive to represent the voices of children and young people with special needs since they are the experts when it comes to matters concerning their own lives.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Little evidence exists on the effects of small class sizes in special education

Despite carrying out extensive literature searches, the authors of this review found only seven studies exploring the question of class size in special education. The authors therefore call for more research from quantitative and qualitative researchers alike, such that practitioners and administrators may find guidance in their endeavours to create the best possible school provisions for all children with special educational needs.

1.2. What is this review about?

While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce, even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. This systematic review sought to examine the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development and well‐being of children with special educational needs.

Furthermore, the review aimed to perform a qualitative exploration of the views of children, teachers and parents concerning class size conditions in special education.

A secondary objective was to explore how potential moderators (e.g. performance at baseline, age, and type of special educational need) affected the outcomes.

What is the aim of this review?

The objective of this Campbell systematic review was to synthesise data from existing studies to assess the impact of small class sizes in special education on students' academic achievement, socioemotional outcomes and well‐being.

1.3. What studies are included?

This review included seven studies, of which two were quantitative, four were qualitative, and one was both quantitative and qualitative. It was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis, nor a qualitative thematic synthesis. The included studies were critically assessed, coded for descriptive data, and narratively summarised.

One quantitative study was assessed to be of sufficient methodological quality following risk of bias assessment. Unfortunately, it was not possible to extract an effect size from this study since it did not report the required information and the study authors could not be contacted.

Three qualitative studies were assessed to be of sufficient methodological quality following qualitative critical appraisal.

1.4. What are the main findings of this review?

There are surprisingly few studies exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education on any outcomes. The included qualitative studies find that smaller class sizes are the most preferred option among students with special educational needs, their teachers and school principals. This is because of the possibilities afforded in terms of individualised instruction time and increased teacher attention to the needs of each student.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

The impact of small class sizes in special education is under‐researched both within the quantitative and the qualitative literature.

Future research should aim to fill this knowledge gap from diverse methodological perspectives, paying close attention to the views of parents, teachers, administrators and, most importantly, the children and young people whose everyday lives are spent in the various special education provisions.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

Searches in bibliographic databases and EBSCO OPEN Dissertations were performed in April 2021, while the remaining searches for grey literature, hand searches in key journals, and citation tracking took place between January and May 2022.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Description of the condition

Class size reductions in general education are some of the most researched educational interventions in social science, yet researchers have not reached any final conclusions regarding their effects. While some researchers point to small and insignificant differences between varying class sizes, others find positive and significant effects of small class sizes on, for example, children's academic outcomes. In a previous Campbell Systematic Review on small class sizes in general education, Filges (2018) found evidence suggesting, at best, a small effect on reading achievement, whereas there was a negative, but statistically insignificant, effect on mathematics.

While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce (see e.g., McCrea, 1996; Russ, 2001; Zarghami, 2004), even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. These students compose a highly diverse group, but they share a common need for special educational accommodations, which often entails additional instructional support in smaller units than what is usually provided in general education. Special education class sizes may vary greatly, both across countries and regions, as well as across different student groups, but will usually be small relative to general education classrooms. In most cases, placement in special education, as opposed to, for example, inclusion in general education, is based exactly on the child's need for close adult support in a smaller unit, where instruction can be tailored to the needs of each child and a calmer, more structured environment can be created. Following this, one may assume that there are advantages to small class sizes in special education, in that children are placed in a suitable environment with the support they need to thrive and learn (for a discussion of perceptions on the benefits of special education, see e.g., Kavale, 2000). However, there may also be challenges to small class sizes, for example, in terms of the opportunities available for building friendships.

It should be noted that class size in special education is connected to other structural factors such as, for example, student–teacher ratio and type of special education provision. In this review, we focus on class size since our main interest lies in exploring the specific mechanisms behind being in a smaller group. However, we have paid close attention to the relatedness and potential overlap between class size and concepts such as student/teacher ratio or caseload (for more about these concepts, see Description of the intervention). When it comes to the type of special education provision, we have included all types of settings where children with special educational needs are grouped together for instruction (i.e., segregated schools/classes/groups/units to which only students with special educational needs attend).

Finally, class size issues, both in general and in special education, are associated with ongoing discussions on educational spending and budgetary constraints. Hence, in school systems imposed with financial constraints, small class sizes in special education settings may be deemed too expensive. As a result, children with special educational needs may be placed in larger units with potential adverse effects on their learning and well‐being. At this point, there is however a lack of clarity as to the effects of small class sizes in special education on student academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being. Inevitably, such lack of clarity is an obstacle for special educators and policymakers trying to make informed decisions. This highlights the policy relevance of the current systematic review, in which we examined the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of children with special educational needs. In working towards this aim, we planned to apply an approach consisting of both a statistical meta‐analysis (if possible from the studies found through our searches) and an exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education, as reported in qualitative studies. We chose to include studies applying a qualitative methodology because the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods had the potential to provide a deeper insight into the complexity of class size questions in special education, including the voices of children and teachers who spend their everyday lives in special education contexts.

2.2. Description of the intervention

Special education in this review refers to educational settings designed to provide instruction exclusively for children with special educational needs. In such settings, both the instructional and physical classroom environment may be adjusted to accommodate the specific needs of the student group, as in the use of individual work tables and visual aids (pictograms) for children on the autism spectrum. We have included studies of all kinds of special education settings that are attended only by children with special educational needs (i.e., segregated special education settings as opposed to inclusion settings where children with and without special educational needs are taught together). We have included both part‐ and full‐time special education provisions (with an example of a part‐time provision being resource rooms attended by students with specific learning difficulties within one or more academic subjects). Furthermore, no limits have been imposed concerning the placement of special education provisions, that is, we have included both separate special schools and special education classes, units or resource rooms lodged within mainstream schools. We acknowledge that significant variations exist in special education provisions across time (e.g., due to new developments in pedagogical approaches and learning aids) and between (as well as within) countries, just as we are aware of the diversity between special education provisions, for example, in terms of how they are staffed and to which degree they are specialised to work with particular student groups. Our approach has therefore been to be inclusive in our search and screening process by not imposing limits on publication date or study location and by defining special education as all kinds of provisions where children with any type of special educational need are grouped together for instruction for any given amount of time (for our definition of what constitutes a special educational need, see Types of participants).

In this review, it is important to distinguish between the following terms: class size, student–teacher ratio, and caseload. Class size refers to the number of students present in a classroom at a given point in time. Student–teacher ratio refers to the number of students per teacher within a classroom or an educational setting. Furthermore, some studies may apply the term caseload which is typically defined as the number of students with individual education plans (IEPs) for whom a teacher serves as ‘case manager’ (Minnesota Department, 2000). In this review, the intervention is a small class size. Thus, studies only considering student–teacher ratios or caseloads are not eligible.

Our rationale for focusing on class size is based in the belief that although class size and student–teacher ratios or caseloads in special education are related, they involve somewhat different assumptions about how a small class size as opposed to a larger one might change the opportunities for students and teachers. With class size, the mechanism in play is based on assumptions about the dynamics of a smaller group and the belief that with smaller groups, teachers are better able to develop an in‐depth understanding of student needs through more focused interactions, better assessment, and fewer disciplinary problems (Ehrenberg, 2001; Filges, 2018). The size of the group in itself will often be of specific importance to students with special educational needs, for example, students diagnosed with sensory processing disorders, making them sensitive to noise and movement, or students with ASD who struggle with reading social cues in larger groups. For such students, being in a larger class would likely feel overwhelming and stressful, no matter the student–teacher ratio.

Student–teacher ratio and caseload are also of great importance, but do not take in the specific mechanisms of being in a smaller group which we find to be central in special education. We acknowledge the relatedness of these concepts to class size and are aware that terms may in some cases overlap. We paid attention to this when searching for studies by adding a search term for student–teacher ratio and when screening the studies.

It is possible that the intensity of the intervention, that is, the size of a change in class size and the initial class size from which this change is made, can play a role in determining the intervention effect. For intensity, the question is: how small does a class have to be to optimise the advantage? In general education for example, large gains are attainable when class size is below 20 students (Biddle, 2002; Finn, 2002), but gains are also attainable if class size is not below 20 students (Angrist, 1999; Borland, 2005; Fredriksson, 2013; Schanzenbach, 2007). It has been argued that the impact of class size reductions of different sizes and from different baseline class sizes is reasonably stable and more or less linear when measured per student (Angrist, 2009; Schanzenbach, 2007). Other researchers argue that the effect of class size is not only non‐linear but also non‐monotonic, implying that an optimal class size exists (Borland, 2005). Thus, the question of whether the size of a change in class size and the initial class size from which the change is made matters for the magnitude of intervention effects is still an open question. For this reason, we planned to include intensity (size of change in special education class size and initial class size) as a moderator if it was possible given the information presented in the included studies.

2.3. How the intervention might work

Due to the specialised and varied nature of special needs provision, issues of class size in this area are likely to be complex (Ahearn, 1995). However, small class sizes may promote student engagement and instructional individualisation, which is of particular importance to students with special educational needs. A research report from 1997 evaluating increases in resource room instructional group size in New York City public schools may serve to illustrate the importance of individualisation in special education (Gottlieb, 1997). The report indicated that increases in instructional group sizes from 5 to at most 8 students per teacher led to decreases in the reading achievement scores of resource room students. Resource room teachers reported diminished opportunities for sufficiently helping students. Furthermore, observations revealed little time spent on individual instruction.

Small class sizes may be better suited to address the potential physical and psychological challenges of students with special educational needs, for example, by providing closer adult‐child interaction, better accommodation of individual needs, and a more focused social interaction with fewer peers. Thus, smaller class sizes in special education may have a positive impact on both academic achievement and socioemotional development as well as on student well‐being at school.

On the other hand, small class sizes may limit the possibilities for finding compatible peers with whom to build friendships, hence leading to adverse effects on student's social and personal well‐being at school. This may also impact on the options available for building social skills, which are vital to, for example, students with autism‐spectrum‐disorders. Furthermore, small class sizes may lead to decreased variation in academic and social skills within the class, limiting the potential for positive peer effects on student academic learning and socioemotional development (e.g., learning from peers with more advanced academic skills).

As reflected in the above discussion about the potential benefits (or lack thereof) pertaining to smaller class sizes in special education, the effects of any given change in class size may occur both within the realm of academic achievement as well as across socioemotional domains (covering children's psychological, emotional, and social adjustment, as well as mental health) and in terms of student well‐being (defined as children's subjective quality of life, pleasant emotions, happiness, and low levels of stress and negative moods); each of these domains (academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being) are therefore included as key outcomes in the present review.

2.4. Why it is important to do this review

As previously noted, there is a lack of clarity as to the impact of small class sizes in special education on student academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being, making it difficult for special educators and policymakers to make informed decisions. Furthermore, class size alterations are associated with ongoing discussions on educational spending and budgetary constraints, highlighting the policy relevance of strengthening the knowledge base through a systematic review of the available literature.

Few authors have tried to review the available literature on special education class sizes, and these reviews have not followed rigorous, systematic frameworks, such as that applied in a Campbell systematic review. McCrea (1996) conducted a review on special education and class size including a sample of American studies. These studies pointed to some effects of class size on the learning environment in class as well as on student achievement and behaviour, especially at the elementary level. Furthermore, in an article exploring the class size literature, Zarghami (2004) examined the effects of appropriate class size and caseload on special education student academic achievement. The authors were not able to identify a single best way to determine appropriate class and group sizes for special education instruction. However, they pointed to the existence of well‐qualified teachers as an important factor in increasing student achievement. Finally, Ahearn (1995) analysed state special education regulations on class size/caseload in the U.S. and reviewed research on class size in general education and special education. The report showed that state requirements for class size/caseload in special education programmes were much more specific and complicated than those for general education, and that the specialised nature and variety of the services delivered to students with special educational needs, combined with the restrictions attributable to specific student disabilities, contributed to those complications. In line with the article by Zarghami (2004), Ahearn (1995) concluded that there was no single best way to determine class sizes for special education programmes, adding that the information available was inadequate.

The above mentioned reviews did not apply the extensive, systematic literature searches and critical appraisals that are performed in a Campbell systematic review. Furthermore, they date back 15 years or more, which means that they do not include newer developments in special education research. Therefore, we find that the present review fills a research gap by providing an up‐to‐date overview of what (little) research is available exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education and the views of children, parents, and teachers who experience different issues related to special education class size. In this sense, the main contribution of the review lies in shedding light on the fact that more research is still needed to gain knowledge into the complexities of class size in special education.

3. OBJECTIVES

The objective of this systematic review was to uncover and synthesise data from studies to assess the impact of small class sizes on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of students in special education. We also aimed to investigate the extent to which the effects differed among subgroups of students. Furthermore, we aimed to perform a qualitative exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education.

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

The screening of potentially eligible studies for this review was performed according to inclusion criteria related to types of study designs, types of participants, types of interventions, and types of outcome measures, all of which are described in the following sections (for the screening guide, see Supporting Information: Appendix 2). These criteria were also specified in the published protocol (Bondebjerg, 2021).

To summarise what is known about the possible causal effects of small special education class sizes, we included all quantitative study designs that used a well‐defined control or comparison group, that is, studies that compared outcomes for groups of students in smaller versus larger special education classes. This is further outlined in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies, and the methodological appropriateness of the included quantitative studies was assessed according to the risk of bias.

The quantitative study designs included in the review were:

-

1.

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (allocated at either the individual or cluster level, for example, class/school/geographical area etc.),

-

2.

Non‐randomised studies (where allocation had occurred in the course of usual decisions, was not controlled by the researcher, and included a comparison of two or more groups of participants, that is, at least a treated group and a control group).

For non‐randomised studies, where the change in class size occurred in the course of usual decisions (e.g., due to policies mandating class size alterations), we assessed whether the authors demonstrated sufficient pre‐reatment group equivalence on key participant characteristics.

Studies using single group pre‐post comparisons were not included. Non‐randomised studies using an instrumental variable approach were also not included—see Supporting Information: Appendix 1 (Justification of exclusion of studies using an instrumental variable (IV) approach) for our rationale for excluding studies of these designs. A further requirement to all types of studies (randomised as well as non‐randomised) was that they were able to identify an intervention effect. Studies where, for example, small classes were present in one school only and the comparison group was larger classes at another school (or more schools for that matter), would not be able to separate the treatment effect from the school effect.

The treatment in this review was a small class size. To investigate the effects of small class sizes, we included studies that compared students in smaller classes with students in larger classes. This meant that we included both studies where the intervention consisted of a reduction in class size and studies where there was an increase in class size, since both types of studies (if robustly conducted) would allow us to compare the outcomes of children in smaller classes with those of children in larger classes. We only included studies that used measures of class size and measures of outcome data at the individual or class level. We excluded studies that relied on measures of class size and measures of outcomes aggregated to a level higher than the class (e.g., school or school district).

In addition to exploring the causal effects of small class sizes in special education through an analysis of quantitative studies meeting the criteria above, we aimed to gain qualitative insight into the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education contexts. To this end, we included all types of empirical qualitative studies that collected primary data and provided descriptions of main methodological issues such as informant selection, data collection procedures, and type of data analysis. Eligible qualitative studies may apply a wealth of data collection methods, including (but not limited) to participant observations, in‐depth interviews, or focus groups.

If we found mixed‐methods studies combining qualitative and quantitative data collection procedures, we assessed whether the quantitative data were eligible for inclusion in the quantitative part of the review (i.e., the quantitative data met the criteria imposed on studies exploring causal relationships), and whether the qualitative data met the criteria imposed on qualitative studies. If a study contained both eligible quantitative and qualitative data, it was included for both quantitative and qualitative quality assessment and data extraction and was counted in both categories. If there were only eligible quantitative data, the study was included only in the quantitative part of the review, and vice‐versa for qualitative studies. That is, mixed methods studies were not treated as a separate category, but were included if either their quantitative or their qualitative research components met the inclusion criteria for quantitative or qualitative studies, respectively.

4.1.2. Types of participants

The review included studies of children with special educational needs in grades K‐12 (or the equivalent in European countries) in special education. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were accepted from all countries. In this review, we excluded children in home‐ or preschool as well as children placed in treatment facilities.

Some controversy exists regarding the definition of what constitutes a special educational need (Vehmas, 2010; Wilson, 2002). In this review, we were guided by the definition from the US Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), in which special needs are divided into 13 different disability categories1:

specific learning disability (covers challenges related to a child's ability to read, write, listen, speak or do math, e.g., dyslexia or dyscalculia),

other health impairment (covers conditions limiting a child's strength, energy, or alertness, e.g., ADHD),

autism spectrum disorder (ASD),

emotional disturbance (may include e.g., anxiety, obsessive‐compulsive disorder and depression),

speech or language impairment (covers difficulties with speech or language, e.g., language problems affecting a child's ability to understand words or express herself),

visual impairment (covers eyesight problems, including partial sight and blindness),

deafness (covers instances where a child cannot hear most or all sounds, even with a hearing aid),

hearing impairment (refers to a hearing loss not covered by the definition of deafness),

deaf‐blindness (covers children suffering from both severe hearing and vision loss),

orthopaedic impairment (covers instances when a child has problems with bodily function or ability, as in the case of cerebral palsy),

intellectual disability (covers below‐average intellectual ability),

traumatic brain injury (covers brain injuries caused by accidents or other kinds of physical force),

multiple disabilities (children with more than one condition covered by the IDEA criteria).

While the above listed criteria provided useful guidance, we were fully aware that they should not be conceived as exhaustive, nor as clear‐cut definitions of what constitutes special educational needs. Therefore, we did not restrict ourselves to only include studies that defined their participants with these terms or which provided detailed information about types of special educational needs. Rather, we included all studies where the participating students received instruction in segregated special education settings (since we took placement in such settings to necessarily indicate a need for specialised educational support) and planned to explore the potential variation between different groups of students, if possible from the included studies.

4.1.3. Types of interventions

In this review, we were interested in investigating whether small class sizes in special education resulted in better academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being for students in special education when compared to larger class sizes. To answer this question, we included studies where special education class size was altered either as a result of a deliberate experiment (where class size was directly manipulated by researchers) or as a result of a naturally occurring change in class size arising due to, for example, the implementation of a new class size policy. This meant that the intervention of interest to this review was a change in special education class size allowing for a comparison between students in smaller classes versus students in larger classes. That is, the question of the effect of small class sizes could be investigated both by looking at studies where class size was reduced and where class size was increased, provided that the studies used a control or comparison group of students in smaller or larger special education classes than the treated group.

The more precisely a class size is measured, the more reliable the findings of a study will be. Studies only considering the average class size measured as student–teacher ratio within a school (or at higher levels) were not eligible. Studies where the intervention was the assignment of an extra teacher (or teaching assistants or other adults) to a class were not eligible. The assignment of additional teachers (or teaching assistants or other adults) to a classroom is not the same as changing the size of the class, and this review focused exclusively on class size. We acknowledged that class size can change per subject or eventually vary during the day, which is why the precision of the class size measure was recorded if possible.

Special education refers to settings where children with special educational needs are taught in classes segregated from general education students. These classes may be composed of children with similar special educational needs (such as classes specifically for children with ASD) or they may consist of mixed groups of children with diverse special educational needs. In such settings, the instructional environment is adjusted to accommodate the specific needs of the student group. In the present review, special education was thus defined as any given group composition consisting of only children with special educational needs. In some studies, special education was also referred to as, for example, segregated placement or resource room. Special education could be full‐time or part‐time (e.g., in the form of resource rooms attended by students for parts of the day). We included studies of all kinds of special education.

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

For quantitative studies, only valid and reliable outcomes that had been used on different populations were eligible.

Primary outcomes

Academic achievement (measured with e.g., the Woodcock‐Johnson III Tests of Achievement, Mather, 2001), socioemotional development and adjustment (measured with e.g., The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ], Goodman, 2001), and well‐being (measured with e.g. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children, Harter, 1982) were categorised as primary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to the primary outcomes, we considered school completion rates as a secondary outcome. Furthermore, we included validated measures of student classroom behaviour, such as structured observations of student engagement, on‐task behaviour, and disruptive behaviour (measured with e.g., The Code for Instructional Structure and Student Academic Response [CISSAR], Greenwood, 1978).

Studies were only included if they considered at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes.

Duration of follow‐up

The review aimed to include follow‐up measures at any given point if meaningful based on the objectives for the review. However, none of the included studies reported outcomes past the end of the intervention.

Qualitative outcomes

For the qualitative analysis, we were interested in exploring the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with special education class sizes, as they presented themselves through, for example, in‐depth qualitative interviews or participant observations. Relevant data could stem from, for example, interviews with teachers on their perceptions of childrens' academic achievement and well‐being in small versus large special education classes, or their experiences with ensuring student engagement and attention under different class sizes. We did not define a list of outcomes in advance, but remained open to what presented itself as important to children, teachers, and parents concerning special education class sizes.

Types of settings

In this review, we included studies of children with special educational needs placed in any special education setting. We excluded studies of children in home‐ or preschool as well as children placed in treatment facilities.

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant quantitative and qualitative studies were identified through searches in electronic databases, grey literature resources, and Internet search engines, as well as through hand‐searches in specific targeted journals and citation‐tracking. We searched for both published and unpublished literature and screened references in English, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian.

Locating qualitative research presents the reviewer with particular challenges since existing search strategies have largely been developed for and applied to the quantitative literature (Frandsen, 2016). As of yet, not all databases have implemented rich qualitative vocabularies or specific structures tailored to accommodate qualitative literature searches. Furthermore, screening on title and abstract may prove challenging since titles and abstracts in qualitative studies are sometimes more focused on content than on issues of methodology (Ibid). Attempts have been made to develop tools specifically designed for qualitative literature searches as an answer to the perceived difficulties in using such existing tools as the PICO(s) framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison (or control), Outcome, and Study design and type). Cooke (2012), for example, present the SPIDER search strategy which attempts to adapt the PICO components to make them more suitable for qualitative research. The SPIDER strategy contains the following components: Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type. In the study by Cooke (2012), two systematic searches are performed, using first the PICO framework and then the SPIDER tool. The results show that the PICO search strategy generates a large number of hits, while the SPIDER tool leads to fewer hits, with the potential advantage of greater specificity. This means that the SPIDER tool may be more precise and easier to manage in terms of the amount of references for screening, however carrying the risk of missing studies.

In this review, we applied elements of the PICO(s) framework to search for both quantitative and qualitative studies by adding both quantitative and qualitative methodological terms in the search string, as well as by carefully looking for both types of studies in our grey literature and hand‐searches. By choosing this strategy, we prioritised the breadth and comprehensiveness of our search (sensitivity) which seemed the most appropriate choice given the anticipated low number of studies exploring class size effects particular to special education. Given the low number of studies found in the searches, we are convinced that our comprehensive approach was the best choice for this particular review topic.

4.2.1. Electronic searches

The following bibliographic databases were searched in April 2021:

ERIC (EBSCO‐host, 1966–2021)

Academic Search Premier (EBSCO‐host, 1931–2021)

EconLit (EBSCO‐host, 1969–2021)

APA PsycINFO (EBSCO‐host, 1890–2021)

SocINDEX (EBSCO‐host, 1895–2021)

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (ProQuest, 1951–2021)

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest, 1952–2021)

Web of Science (Clarivate, Science Citation Index Expanded, 1900–2021, and Social Sciences Citation Index, 1956–2021)

Description of search string

The search string was based on the PICO(s)‐model, and contained three concepts of which we developed three corresponding search facets: population, intervention, and study type/methodology. The search string includes searches in title, abstract, and subject terms for each facet. To increase the sensitivity of the search, we also searched in full text for the intervention terms. The subject terms in the facets were selected according to the thesaurus or subject term index on each database.

Example of a search string

The search string below from the ERIC database exemplifies the search which followed this structure:

Search 1–4 covered the population,

Search 5–9 covered the intervention,

Search 10–16 covered the study type/methodology terms,

Search 17 combined the three aspects.

| Search | Terms |

| S17 | S4 AND S9 AND S16 |

| S16 | S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 |

| S15 | DE (‘Qualitative Research’ OR ‘Ethnography’ OR ‘Case Studies’ OR ‘Evaluation Methods’ OR ‘Field Studies’ OR ‘Focus Groups’ OR ‘Interviews’ OR ‘Mixed Methods Research’ OR ‘Naturalistic Observation’ OR ‘Participant Observation’ OR ‘Classroom Observation Techniques’ OR ‘Observation’ OR ‘Action Research’) |

| S14 | AB (qualitative* OR ethnograp* OR ‘case stud*’ OR evaluation* OR ‘focus group*’ OR interview* OR ‘mixed method*’ OR observation*) |

| S13 | TI (qualitative* OR ethnograp* OR ‘case stud*’ OR evaluation* OR ‘focus group*’ OR interview* OR ‘mixed method*’ OR observation*) |

| S12 | DE (‘Effect Size’ OR ‘Control Groups’ OR ‘Experimental Groups’ OR ‘Experiments’ OR ‘Matched Groups’ OR ‘Quasiexperimental Design’ OR ‘Randomized Controlled Trials’ OR ‘Comparative Testing’ OR ‘Intervention’) |

| S11 | AB (effect* OR trial* OR experiment* OR ‘control group*’ OR random* OR impact* OR compar* OR difference*) |

| S10 | TI (effect* OR trial* OR experiment* OR ‘control group*’ OR random* OR impact* OR compar* OR difference*) |

| S9 | S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 |

| S8 | DE (‘Class Size’ OR ‘Small Classes’ OR ‘Teacher Student Ratio’) |

| S7 | TX (group* OR class*) N5 (size*) |

| S6 | AB (group* OR class*) AND AB (size* OR ratio*) |

| S5 | TI (group* OR class*) AND TI (size* OR ratio*) |

| S4 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 |

| S3 | DE (‘Special Needs Students’ OR ‘Special Schools’ OR ‘Residential Schools’ OR ‘Educationally Disadvantaged’ OR ‘Developmental Delays’ OR ‘Students with Disabilities’ OR ‘Special Classes’ OR ‘Special Education’ OR ‘Self Contained Classrooms’ OR ‘Resource Room’) |

| S2 | AB (special*) AND AB (need* OR education OR child* OR student* OR pupil*) |

| S1 | TI (special*) AND TI (need* OR education OR child* OR student* OR pupil*) |

Limitations of the search string

We did not restrict our searches based on publication date or language. In screening and processing the references found, we were however limited by the language proficiencies available on the review team which allowed us to consider studies published in English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish.

4.2.2. Searching other resources

Hand‐search

We implemented hand‐searches in key journals to identify references that were poorly indexed in the bibliographic databases and to ensure coverage of references that were published, but had not yet been indexed. We hand‐searched individual tables of content of respective issues of the chosen journals going back to 01/01/2015.

Our selection of journals to hand‐search was based on the frequency of journals identified in our pilot searches during the design phase of the search string. The following journals were selected:

Behavioral Disorders

Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders

Exceptional Children

Learning Disability Quarterly

International Journal of Disability, Development & Education

Remedial and Special Education

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research

British Journal of Special Education

Learning Disabilities Research & Practice

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

European Educational Research Journal

Searches for unpublished literature

Most of the resources searched for unpublished literature contained multiple types of unpublished literature. For the sake of transparency, we have divided the resources into categories based on the most prevalent type of literature in the resource.

Searches for dissertations and theses in English:

EBSCO Open Dissertations (EBSCO‐host)

Searches for working papers and conference proceedings in English:

Google Scholar—https://scholar.google.com/

Social Science Research Network—https://www.ssrn.com/index.cfm/en/

OECD iLibrary—https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/

NBER working paper series—http://www.nber.org

American Educational Research Association (AERA)—https://www.aera.net/

Search for Reports and on‐going studies in English:

Google searches—https://www.google.com/

Best Evidence Encyclopaedia—http://www.bestevidence.org/

Social Care Online—https://www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/

Searches for dissertations, theses, working papers and conference proceedings in Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian:

Forskning.ku—Academic publications from the University of Copenhagen—https://forskning.ku.dk/soeg/

AAU Publications—Academic publications from the University of Aarhus https://pure.au.dk/portal/da/organisations/8000/publications.html

SwePub ‐ Academic publications at Swedish universities—http://swepub.kb.se/se/

NORA ‐ Norwegian Open Research Archives—http://nora.openaccess.no/

DIVA—Swedish Digital Scientific Archives—http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/

Skolporten—Swedish Dissertations—https://www.skolporten.se/forskning/

Searches for reports and on‐going studies in Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian:

CORE—research outputs from international repositories ‐ https://core.ac.uk/

Google searches—https://www.google.com/

Search for systematic reviews

We searched for systematic reviews through the following resources:

Campbell Journal of Systematic Reviews—https://campbellcollaboration.org/

Cochrane Library—https://www.cochranelibrary.com/

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Databases—https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/

EPPI‐Centre Database of Education Research—https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/Intro.aspx?ID=6

Citation‐tracking and snowballing methods of systematic reviews

We performed citation‐tracking on systematic reviews identified in the protocol stage and through the search process to identify additional relevant references. The following reviews/research overviews were processed using both forward and backward citation‐tracking: Ahearn, 1995; McCrea, 1996; Zarghami, 2004.

Citation‐tracking and snowballing methods of individual references

We had planned to select the most recently published and the most cited key references for citation‐tracking, with the expectation that we would select approximately 20 references (10 recent, 10 most cited). This approach was made impossible by the low number of relevant references found during the search process. We therefore chose to perform citation‐tracking on the included references: Forness, 1985; Gottlieb, 1997; Huang, 2020; Keith, 1993a; Metzner, 1926; Prunty, 2012. It was not possible to perform citation‐tracking on the study from MAGI Educational Services, Inc., 1995 since it did not contain a reference list.

Contact to experts

We had planned to contact study authors if we found references to or mentions of ongoing studies in screened publications, but this did not occur during the search and screening process. Furthermore, the searches did not locate any particular individual experts or institutions that we could reach out to for more information on published or unpublished studies covering the subject matter.

A complete overview of the search strings used and the resulting references found for each electronic database, as well as search terms and hits for the grey literature resources, and results from the hand‐searches can be found in the appendix. Database searches were performed in April 2021. Searches for grey literature, hand‐search in key journals, and citation‐tracking took place between January and May 2022 (with the exception of the search in EBSCO OPEN Dissertations which was performed in April 2021, simultaneous with the database searches).

4.3. Data collection and analysis

4.3.1. Selection of studies

Under the supervision of review authors, two review team assistants first independently screened titles and abstracts to exclude studies that were clearly irrelevant. Studies considered eligible by at least one assistant or studies where there was insufficient information in the title and abstract to judge eligibility were retrieved in full text. The full texts were subsequently screened independently by two review team assistants under the supervision of the review authors. Any disagreement of eligibility was resolved by the review authors. Screening on both title/abstract and full text was performed using EPPI‐Reviewer 4 software (Thomas, 2022). Exclusion of studies that otherwise might be expected to be eligible was documented (see Excluded studies).

None of the review authors were blind to the authors, institutions, or journals responsible for the publication of the articles.

4.3.2. Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently coded and extracted data from included studies. Coding sheets for quantitative and qualitative studies were piloted and revised as necessary. For the included quantitative studies, data was extracted regarding school setting and location, participant characteristics (for children: type of special need, age, ethnic/cultural/language background, SES, gender, and for teachers: education and experience), study design, class size information (including size and duration of class size alteration), type and format of data, outcome measurement, sample size, and effect size information (see Table 1 for the full data extraction sheet filled out with data from the included quantitative studies). From the included qualitative studies, we extracted information pertaining to the school setting and location, class size conditions, study design, theoretical perspective of the study, research objectives, student information (age, gender, SES, type of special need), and teacher and parent characteristics, if relevant (see Table 2 for the full data extraction sheet filled out with data from the included qualitative studies).

Table 1.

Data extraction: Quantitative studies.

| Author | Title | Language | Outlet (journal name/other outlet/dissertation/unclear) | Year | Study location | Type of school and educational setting | Type of special need | Child age (mean and range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metzner (1926) | Size of class for mentally retarded children | English | The Training School Bulletin | 1926 | Detroit, U.S. | Type of school not specified, but setting is probably half‐time. | Mental retardation | Approximately an average of 10.8, range not reported. |

| Forness (1985) | Effects of class size on attention, communication, and disruption of mildly mentally retarded children | English | American Educational Research Journal | 1985 | California, U.S. | Not specified, but it is probable that all students spent more than half their day in special class, and that regular class integration was limited to non‐academic classroom periods during the afternoons. | Mildly mentally retarded (educable) | Mean age in small classes 12.3; medium classes 11.0; large classes 11.2; overall 11.3. |

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Results of a Statewide Research Study on the Effects of Class Size in Special Education | English | Class Size Research Bulletin | 1995 | New York, U.S. | Modified Instructional Services (MIS) I classes which covered classes for students who required instructional services in a special class with opportunities for mainstreaming. Students could supposedly spend both full‐time or less in these classes, depending on pull‐out services or involvement with mainstream classrooms. | The majority of MIS I students were classified as learning disabled. | Not reported, but both elementary and secondary students. |

| Author | Child ethnic, cultural, and language background | Child SES | Child gender | Teacher education and experience | Study design | Class size | Intensity (size of reduction) | Duration of class size reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metzner (1926) | Not specified | Not specified | Varies between 47.5% and 71.1% boys in treatment groups; in control group 64% boys. | Not specified | Treated are three classes with 15 students, three classes with 20 students, three classes with 25 students, and three classes with 30 students; controls are 12 classes with 22 students. | A reduction of 2 and 7 and an increase of 3 and 8. | 180 days | |

| Forness (1985) | Not specified | Not specified | Small classes: 50% male; medium classes 58% male; large classes 56% male; overall 56% male. | Not specified | 5 small classes (10–13), 14 medium classes (14–16), and 7 large classes (18–21). | Mean difference between small and medium classes is 2.5 students, and between medium and large classes 4 students. | Not specified, but presumably most subjects had been in EMR (special education) classes for at least several months. | |

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Quasi‐experimental observation study | Students and teachers were randomly selected from two class size options: 12:1 and 15:1. Actual number of students observed in the classrooms was generally much lower than the number of students registered. | Formally an increase in some classrooms from 12:1 to 15:1 (so an increase of 3). | Not specified |

| Author | Type of data (Independent observation/Questionnaire/Other) | Format (Continuous/Categorical/Dichotomous) | Number of measures and timing | Type(s) and name(s) of outcomes (Academic Achievement/Socioemotional outcomes/Wellbeing/Student classroom behaviour (please state name of outcome, e.g. SDQ)) | Sample size | Means/regression coefficients/t‐ and F‐statistics/Other | Standard deviations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metzner (1926) | Pressy first grade reading test was given to those who had done no academic work beyond first grade, and the Stanford Achievement Test for grade 2 and 3 was given to the remaining. | Continuous | Experiment lasted 180 days, tests taken before and at the end. | Reading. Pressy Reading Test and Stanford Achievement Test. | Treated are three classes with 15 students, three classes with 20 students, three classes with 25 students, and three classes with 30 students (total: 270); controls are 12 classes with 22 students (total: 264). | Pre‐test scores and gain scores, Tables 1 and 2. | No SD's reported. |

| Forness (1985) | The outcome (behaviour) was recorded on each child in specific categories of classroom functioning using an observation system described in detail in Forness, 1983 (available on request from the senior author, i.e. not published). | Percentage of time with a specific behaviour. | Data gathered in April, year not reported. | Behaviour divided into four pre‐determined categories: (a) communication‐ task‐oriented verbal or gestural response (e.g., pupil asks or answers a question, recites or raises hand); (b) attend‐ eye contact to teacher, task materials, or peer who is reciting; (c) not attend‐ eye contact not directed to teacher, task materials, or pupil who is reciting; and (d) disrupt‐behaviour incompatible with on‐task activities (e.g., talks to another pupil when not permitted, speaks out of turn, hits classmates, or throws objects). | 26 classes and 393 students. 5 small classes (10–13) with 61 students, 14 medium classes (14–16) with 202 students, and 7 large classes (18–21) with 130 students. | Outcome reported as percentages. The total for each behaviour was computed across all response conditions for each subject. The percentage of time each child received a response from teachers was computed across all types of behaviour as a measure of time the teacher appeared to be involved with each subject, and the same was computed for classmate as a measure of the relative amount of time each subject appeared to interact with peers. Mean percentage by group is reported and overall mean and SD. Table 4. | Table 4 |

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Two standardised observational instruments were used. | Percentage of time with a specific behaviour. | Not specified | Classroom behaviour observed with: The Code for Instructional Structure and Student Academic Response (MS‐CISSAR), and The Instructional Environment System (TIES II). | 753 elementary and secondary students and 203 teachers were randomly selected from the two class size options (12:1 and 15:1). | Percentage of time engaged in different classroom behaviours. | Not reported |

Table 2.

Data extraction: Qualitative studies.

| Author(s) | Title | Outlet (journal, dissertation, report) | Year | Type of special education setting (e.g., resource class, special school) | Class size information | Study location | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gottlieb (1997) | An evaluation Study of the Impact of Modifying Instructional Group Sizes in Resource Rooms and Related Service Groups in New York City | Report | 1997 | Resource rooms and speech services | In elementary school: 16,26 in 1994‐1995, and 24,39 in 1995‐1996. | New York City, U.S. | Evaluation design using questionnaires, interviews observations, and achievement data. |

| In middle school: 20,02 in 1994–1995, and 30,21 in 1995–1996. | |||||||

| No accurate data for high schools. | |||||||

| Huang (2020) | Special education teachers’ perceptions of and practices in individualising instruction for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in China | Dissertation | 2020 | Special education schools | Class size ranged from five to 14 students (M = 9,4). | Shanghai, China | Interview study |

| Keith (1993a) | Special Education Program Standards Study. Commonwealth of Virginia. Final Technical Report | Report | 1993 | Special education classes | Not specified | Virginia, U.S. | Mixed‐methods evaluation study using interviews, observations, document review, and a survey |

| Prunty (2012) | Voices of students with special educational needs (SEN): views on schooling | British Journal of Learning Support | 2012 | Special schools or special education classes in mainstream schools | Not specified | Ireland and England | Interview study (focus groups, and individual interviews) |

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Results of a Statewide Research Study on the Effects of Class Size in Special Education | Class Size Research Bulletin | 1995 | Modified Instructional Services (MIS) I classes which covered classes for students who required instructional services in a special class with opportunities for mainstreaming. Students could supposedly spend both full‐time or less in these classes, depending on pull‐out services or involvement with mainstream classrooms. | Class size was increased from 12 to 15 students. | New York, U.S. | The study consisted of a descriptive part and an experimental/observational part. Focus here is on the descriptive study which used a number of complementary data collection methods including document review, public hearings, focus groups, surveys of key informants, and record review. |

| Author(s) | Theoretical perspective | Research objectives | Student age and gender | Characteristics of student group (e.g., category of special needs, SES) | Teacher education and experience | Parent characteristics (e.g., SES) | Overall quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gottlieb (1997) | Not specified | To evaluate the impact of increased group size on the quality and availability of resource rooms and related service instruction. | Not specified | Not specified | Participants were resource room teachers (representing all levels of schooling), speech therapists, and general education teachers (who had resource room students enroled in their classes). | Not specified | Include for analysis. No philosophical or theoretical perspectives presented and not a lot of information on methods and analytical procedures. However, the paper works well as an evaluation report, and the design chosen is appropriate for an evaluation. The conclusions drawn flow from the descriptive data presented. |

| Huang (2020) | Critical realism | To investigate and describe Chinese special education teachers’ perceptions and practices related to individualising or adapting instruction for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. | Grades 1–6 | Students with intellectual and developmental disabilities, covering both autism, physical impairments, and intellectual disabilities. Other types of disabilities were less frequently represented. | The participating teachers were Chinese language arts and math special education teachers with an average of 14,6 years of experience teaching students with intellectual and developmental disabilities (range was three‐26 years). All but two participants held Bachelor's degrees as their highest educational level. | Not specified | Include for analysis. Class size is not the main topic of the study, but it is touched upon. The study is well‐performed and clearly reported. |

| Keith (1993a) | Not specified | To investigate Virginia special education program standards, focusing on local applications of the standards for class size and class mix and the effects of varying class sizes and mix on student outcomes. | Students were from preschool, elementary, middle, and high school. Boys made up 70% of the students in the special education programmes | Students with educable mental retardation, severe emotional disturbance, and specific learning disabilities. | Teachers had worked an average of 6,5 years in their current job, and had worked an an average of 11 years in the field of special education. Almost half the teachers had a Bachelor's degree as their highest educational level, while another 49% held Master's degrees. | Not specified | Exclude from analysis. No philosophical or theoretical perspective stated, very limited description of data collection, and the approach to qualitative analysis is not described. It is unclear in what way the site visits and interview material was used. The paper functions well enough as an evaluation report, but as a qualitative research study, it is inadequately reported and therefore not suited for inclusion. |

| Prunty (2012) | Perspective of the child | To explore the views of children and young people on their schooling | Not specified | Not clearly presented, but some had physical disabilities, while others had mental disabilities | Not specified | Not specified | Include for analysis. This study is not about differences between different special education settings, but more about differences between mainstream/inclusion and special education. Nonetheless, there are points made here that carry relevance to the issue of special education class size. In terms of methodological quality, the study is well performed and transparently reported. |

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Not specified | To examine class size effects on students, service providers, parents, and school districts. | Students were from elementary and secondary grades. | The majority of students were classified as learning disabled. | Not specified | Not specified | Exclude from analysis. No philosophical or theoretical perspective stated, very limited description of data collection, and the approach to qualitative analysis is not described. |

4.3.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We did not locate any randomised studies. Therefore, included quantitative studies were assessed for risk of bias using the model ROBINS–I, developed by members of the Cochrane Bias Methods Group and the Cochrane Non‐Randomised Studies Methods Group (Sterne, 2016a). We used the latest template for completion (which was the version of 19 September 2016). The ROBINS‐I tool is based on the Cochrane RoB tool for randomised trials, which was launched in 2008 and modified in 2011 (Higgins, 2011a).

The ROBINS‐I tool covers seven domains (each with a set of signalling questions to be answered for a specific outcome) through which bias might be introduced into non‐randomised studies:

-

(1)

bias due to confounding;

-

(2)

bias in selection of participants;

-

(3)

bias in classification of interventions;

-

(4)

bias due to deviations from intended interventions;

-

(5)

bias due to missing outcome data;

-

(6)

bias in measurement of the outcome;

-

(7)

bias in selection of the reported result.

The first two domains address issues before the start of the interventions and the third domain addresses classification of the interventions themselves. The last four domains address issues after the start of interventions and there is substantial overlap for these four domains between bias in randomised studies and bias in non‐randomised studies (although signalling questions are somewhat different in several places, see Sterne, 2016b and Higgins, 2019).

Non‐randomised study outcomes are rated on a ‘Low/Moderate/Serious/Critical/No Information’ scale on each domain. The level ‘Critical’ means that the study (outcome) is too problematic in this domain to provide any useful evidence on the effects of the intervention and is excluded from the data synthesis.

We discontinued the assessment of a non‐randomised study outcome as soon as one domain in the ROBINS‐I was judged as ‘Critical’. ‘Serious’ risk of bias in multiple domains in the ROBINS‐I assessment tool could also lead to a decision of an overall judgement of ‘Critical’ risk of bias for that outcome, leading the study to be excluded from the data synthesis.

Confounding

An important part of the risk of bias assessment of non‐randomised studies is consideration of how the studies deal with confounding factors. Systematic baseline differences between groups can compromise comparability between groups. Baseline differences can be observable (e.g., age and gender) and unobservable (to the researcher; e.g., childrens’ motivation and ‘ability’). There is no single non‐randomised study design that always solves the selection problem. Different designs represent different approaches to dealing with selection problems under different assumptions, and consequently require different types of data. There can be particularly great variation in how different designs deal with selection on unobservables. The ‘adequate’ method depends on the model generating participation, that is, assumptions about the nature of the process by which participants are selected into a programme.

As there is no universally correct way to construct counterfactuals for non‐randomised designs, we looked for evidence that identification was achieved, and whether the authors of the primary studies justified their choice of method in a convincing manner by discussing the assumptions leading to identification (the assumptions that made it possible to identify the counterfactual). Preferably, the authors should make an effort to justify their choice of method and convince the reader that the special needs students exposed to different class sizes were comparable.

In addition to unobservables, we identified the following observable confounding factors to be the most relevant for this review: performance at baseline, age of the child (chronological age and/or developmental age, if reported), category of special educational need and functional level, and socioeconomic background. In each study, we assessed whether these factors had been considered, and in addition we assessed other factors likely to be a source of confounding within the individual included studies.

Importance of pre‐specified confounding factors

The motivation for focusing on performance at baseline, age of the child, category of special educational need and functional level, and socioeconomic background, is outlined below.

Performance at baseline is a highly relevant confounding factor to consider, since students with special educational needs constitute a highly diverse population. There may be large achievement differences between children in special education classes, even when the children are of equal age and enroled in similar special education classes at the same grade level. This is true both when comparing children with different special educational needs profiles and children diagnosed with similar functional levels. This highlights the need for researchers to pay close attention to the risk of confounding due to achievement differences present at baseline.

The reason for including age as a pre‐specified confounder is that the needs of children change as they grow older. Young children are often more dependent on stimulating adult‐child interactions and have higher support needs, both academically and in terms of behavioural/emotional support. Therefore, to be sure that an effect estimate is a result from a comparison of groups with no systematic baseline differences, it is important to control for the students' age. In this review, it is important to both consider chronological age and developmental age, if this is reported.

As can be seen in the definition of special educational needs, the categories cover a very broad range of disabilities and functional levels. It is possible that special education students with some diagnoses or degrees of impairment require, for example, an increased need for individual support and close adult‐child interaction, or they may have an inability to cope in larger groups of children due to difficulties in sensory processing. Therefore, the special needs category and impairment level are important confounding variables.

Finally, a large body of research documents the impact of parental socioeconomic background on almost all aspects of childrens' development (e.g., Renninger, 2006), which is why we find it to be common place to include this as a potential confounding factor.

Effect of primary interest and important co‐interventions

We were mainly interested in the effect of actually participating in the intervention (in this case, receiving instruction in a smaller as opposed to a larger special education class), that is, the treatment on the treated effect (TOT). The risk of bias assessments were therefore carried out in relation to this specific effect. The risk of bias assessments considered adherence to intervention and differences in additional interventions (‘co‐interventions’) between intervention groups. Important co‐interventions we considered were other types of classroom support available to children with special educational needs, for example, software packages for children suffering from dyslexia. Furthermore, additional teachers or teacher aides in a classroom were considered an important co‐intervention.

Assessment

At least two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each relevant outcome from the included studies (see Table 3 for the risk of bias assessment of included quantitative studies).

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment of included quantitative studies (ROBINS‐I).

| Author | Title | Overall comment | Overall judgement | Confounding bias | Judgement | Selection bias | Judgement | Classification bias | Judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metzner (1926) | Size of class for mentally retarded children | This is a well‐performed study, but unfortunately, SD's are missing and are not possible to retrieve or calculate. | Moderate risk of bias | The authors term it an experiment, but only report that groups of mentally retarded students (four treated and one control) were ‘formed’. Treated are three classes with 15 students, three classes with 20 students, three classes with 25 students, and three classes with 30 students; controls are 12 classes with 22 students. Gender is highly imbalanced, mental age and age in years are reasonably balanced, IQ is reasonably balanced, and SES is not reported (Table 3). Nothing is controlled for. | Moderate risk of bias | 8%–10% were replaced due to drop‐out (p. 242), otherwise all children from the initial sample are followed from start to finish. Replacements took the same pre‐tests as students in the initial sample, but the size of the class they attended before they were included as replacements and the timing of the replacement is not reported. | Moderate risk of bias | Nothing of concern | Low risk of bias |

| Forness (1985) | Effects of class size on attention, communication, and disruption of mildly mentally retarded children | The study is given a rating of critical risk of bias in the confounding domain and the rest is therefore not assessed. | Critical risk of bias | Only age and gender considered (Table 3). There is some imbalance on gender (between small classes vs. medium and large) and a relatively large imbalance on age (between small classes vs. medium and large). All students are characterised as mildly/educable mentally retarded (IQ range of 50–70). Nothing is controlled for. | Critical risk of bias | ||||

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) | Results of a Statewide Research Study on the Effects of Class Size in Special Education | The study is given a rating of critical risk of bias in the confounding domain and the rest is therefore not assessed. | Critical risk of bias | No confounders considered. | Critical risk of bias |

| Author | Deviation bias | Judgement | Missing data | Judgement | Measurement bias | Judgement | Reporting bias | Judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metzner (1926) | Eight percent of the control group and 10% of the treated (not reported separately by the four treatment groups, but reported that the range was 8%–13%) dropped out and were replaced. The size of the class they attended before they were included as replacements and the timing of the replacement is not reported. | Moderate risk of bias | Eight percent of the control group and 10% of the treated (not reported separately by the four treatment groups, but reported that the range was 8%–13%) dropped out and were replaced. Data only shown for those who were in the study by the end of the experiment. | Moderate risk of bias | No mentioning of blinding, otherwise tests are standardised tests (Stanford‐Binet and Pressey reading test) | Moderate risk of bias | No pre‐specified plan of analysis, but otherwise nothing to indicate selective reporting biases | Moderate risk of bias |

| Forness (1985) | ||||||||

| MAGI Educational Services, Inc. (1995) |

4.3.4. Measures of treatment effect

Continuous outcomes