Abstract

Block copolymer micelles have demonstrated great promise in the solubilization of hydrophobic drugs, but understanding of the blood stability of the drug-laden micelles is needed for therapeutic advancement of micelle technologies. Following intravenous administration, mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA micelles have demonstrated quick release their cargo and disassembly in blood, but the prevailing mechanisms of micelle disruption and key biomacromolecules driving this disruption have yet to be elucidated. Although protein interactions with solid polymeric nanoparticles have been characterized, not much is known regarding protein interactions with dynamic block copolymer micelles. Herein, we characterized the interaction of bovine and human serum albumin with polymeric micelles, mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA, using protein fluorescence, isothermal titration calorimetry, and circular dichroism spectroscopy. We found bovine and human serum albumin have interactions with mPEG-CL, while only human serum albumin was observed to weakly interact with mPEG-LA. Protein fluorescence suggested that binding of human serum albumin to mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA is driven by electrostatic interactions. Isothermal titration calorimetry suggested an interaction between serum albumin and mPEG-CL block copolymers driven by hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions in physiologic MOPS-buffered saline, while mPEG-LA had no measurable interaction with either serum albumin. Circular dichroism spectroscopy demonstrated that protein secondary structure was intact in both proteins in the presence of mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA. Overall, BSA was not always predictive of polymeric interactions with human serum albumin. Understanding of interactions between serum proteins and block copolymer micelles, and the exact mechanisms of destabilization will direct the rational design of block copolymer systems for improving blood stability.

Keywords: micelle, polymer, albumin, interactions, protein-polymer interactions

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Block copolymer micelles have shown great promise in replacing poorly-tolerated surfactant and cosolvent vehicles for the solubilization of hydrophobic drugs. The materials commonly used in producing micelle formulations, including poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and either poly(caprolactone) (PCL), and poly(lactide) (PLA) have been previously approved in medicines or devices by the US FDA and other regulatory agencies. These materials are thought to be safe and have limited negative biologic activity. Micellar formulations have been successful in increasing aqueous solubility and improving pharmacokinetic profiles of hydrophobic drugs.1 In clinical trials, a micellar formulation of paclitaxel increased the mean tolerated dose over the traditional Cremophor EL formulation without increasing observed toxicities. However, the micellar formulation did not eliminate paclitaxel-related neuropathy, myalgia, neutropenia, and hypersensitivity reactions.2, 3 The observed therapeutically-limiting toxicities have been attributed to paclitaxel, which would presumably occur after rapid release of drug from micelle.4 Understanding micelle stability and drug retention within the micelle should allow understanding and prediction of ways to improve efficacy while limiting toxicities.

Micelle instability can occur through premature release of encapsulated cargo from the micelle core or through disassembly of the micelle.5, 6 Poly(ethylene glycol-block-polylactide) (PEG-LA) micelles released encapsulated fluorescent dyes within 15 minutes following intravenous injection in mice, and mPEG-LA micelles disassembled within 1 hour of intravenous injection in mice in a similar study.7, 8 Most investigations have focused on the role of serum proteins on promoting destabilization of micelles. Bovine serum albumin (Cy5 labelled) was observed to be in proximity to PEG-PCL-Cy5.5, producing FRET signal after mixing.7 However, the presence of serum albumin only resulted in the disassembly of approximately 13% of the micelles by their calculations, and even less micelle disassembly was observed in serum or whole blood. It remains unclear exactly how protein interactions destabilize polymeric micelles and how to best improve micelle stability in the blood.

Although micelle stability and drug release have been examined for numerous block copolymer micelles, the interaction between proteins and block copolymer micelles has not been characterized in detail. In the present work, we characterized the biophysical interaction between serum albumins and two block copolymers micelles, poly(ethylene glycol-block-caprolactone) (mPEG-CL) and poly(ethylene glycol-block-polylactide) (mPEG-LA). These block copolymers were examined because they are commonly investigated in the preclinical development of micellar formulations due their excellent biocompatibility and ability to solubilize hydrophobic drugs. Serum albumin represents the most prevalent protein within blood and the most common protein found to interact with polymeric nanoparticles. Understanding the interactions between block copolymer micelles and serum proteins will help in developing the micelle delivery platform towards overcoming current limitations and increasing clinical translation.

Materials Methods

Materials

Poly(ethylene glycol) with a molecular weight of 2000 g/mol (PEG2000) was obtained from Fluka. Poly(ethylene glycol-block-caprolactone) (PEG-CL; AK073; 70411STR-B) and poly(ethylene glycol-block-polylactide) (PEG-LA; AK009; 190813RAI-B) were obtained from Polyscitech and used for BSA ITC and CD experiments. Poly(ethylene glycol-block-caprolactone) (PEG-CL; AK073; 40319SMS-A) and poly(ethylene glycol-block-polylactide) (PEG-LA; AK009; 180329YSK-A) were obtained from Polyscitech and used for protein fluorescence and HSA ITC and CD experiments. 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG-DSPE) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was obtained from Millipore Sigma. Fatty acid-free human serum albumin and pyrene were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Acetone, sodium chloride, sodium phosphate dibasic anhydrous, sodium phosphate monobasic, 3-(4-morpholino)propane sulfonic acid (MOPS), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Regenerated cellulose dialysis membranes with a molecular weight cutoff of 3500 g/mol were obtained from Spectrum Laboratories.

Micelle preparation and characterization

The molecular weight for each of the block copolymers used was provided by the suppliers (Table 1). The three polymers have PEG hydrophilic block of approximately 2,000 g/mol. The PEG-DSPE has the smallest hydrophobic block followed by mPEG-LA and mPEG-CL. PEG2000 solutions were prepared by dissolving in buffer and stirring overnight at room temperature.

Table 1.

Micelle parameters.

| Diblock copolymer (A-b-B) |

Molecular Weight (g/mol)a | HLBb | Micelle Diameter (nm)c | Zeta Potential (mV)c |

CMC (μM)c,d |

CMC (μg/mL)c,d |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG | DSPE/CL/LA | ||||||

| mPEG-DSPE | 2000 | 805 | 14.3 | 13.2 ± 0.8 | −30.2 ± 8.8 | 5.63 ± 0.73 | 15.8 ± 2.1 |

| mPEG-CLe | 2298 | 3128 | 8.5 | 25.0 ± 0.2 | −18.2 ± 0.9 | 0.53 ± 0.11 | 3.43 ± 0.7 |

| 2135 | 4391 | 6.5 | 26.7 ± 1.0 | −7.8 ± 1.3 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | |

| mPEG-LAf | 1951 | 2778 | 8.3 | 24.2 ± 0.6 | −11.0 ± 0.6 | 3.16 ± 2.25 | 14.9 ± 10.7 |

| 2135 | 2665 | 8.9 | 29.0 ± 0.2 | −14.9 ± 5.1 | 1.21 ± 0.64 | 7.7 ± 4.1 | |

Data supplied by manufacturer.

Calculated from supplied molecular weights.

Data calculated and presented as mean ± standard deviation of the mean.

Calculated from Boltzmann fit of three independent measurements.

Two separate batches of mPEG-CL were used in these experiments, as described in the materials and methods.

Two separate batches of mPEG-LA were used in these experiments, as described in the materials and methods.

Block copolymers were dissolved in acetone to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and stirred for 30 minutes. Four parts water per five parts acetone was added dropwise while stirring. The solution was dialyzed against deionized water in a cellulose ester dialysis membrane with 7 dialysate changes over a minimum of 24 hours. Micelle preparations were filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF syringe filter.

Lipid micelles (mPEG-DSPE) were prepared by thin-film rehydration method.9 Briefly, mPEG-DSPE was dissolved in chloroform to a concentration of 2 mM and organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporation in a water bath at 40°C to produce a dry film. Residual solvent was removed by drying in vacuum desiccator overnight. The film was reconstituted with 0.9% sodium chloride solution with 5 minutes of vortexing followed by 5 minutes of sonication. Argon gas was layered over samples and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in the dark before characterization.

Co-polymer concentration was determined using UV-Vis quantification on Beckman DU800 UV-VIS spectrophotometer as previously described.10, 11 Dynamic light scattering was used to determine both micelle diameter and zeta potential on the Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. For micelle diameter, measurements were performed using 50 μL of each sample at room temperature. For zeta potential, 1 mL of micelles in 500 μM HEPES, 20 μM NaCl at pH 7.0 was placed in a disposable folded capillary cell and run at 40 V at room temperature for 5 measurements of a maximum of 100 runs with a 60 second delay between measurements. A monomodal analysis was used for determining zeta potential to minimize electrode degradation.

Critical micelle concentration

Critical micelle concentration (CMC) was determined using pyrene as a fluorescence probe for the environment.12 Briefly, serial dilutions of different block copolymer micelle solutions were prepared in water (0.006 – 50 μM) in amber vials. Pyrene in acetone was added to each polymer solution to achieve a final concentration of 2 μM. Micelles were agitated overnight, protected from light to allow for partitioning of pyrene into micelles and evaporation of acetone. Fluorescence was measured on a Shimadzu RF 1501 spectrofluorophotometer using an excitation wavelength of 333 nm and scanning emission wavelengths of 350 nm to 400 nm. The ratio of the fluorescent intensities at the 373 and 388 nm wavelengths (I388/I373) was determined for each concentration of polymer. The CMC value was determined from the value of the inflection point of the curve.13

Fluorescence spectroscopy

The interactions between block copolymer micelles and serum albumins were assessed by measuring the changes in intrinsic fluorescence of tryptophan residues in serum albumin. Serum albumin interactions with soluble PEG2000 were also determined, as PEG polymers have been shown to have some protein interactions as well.14, 15 mPEG-DSPE served as a positive control having previously demonstrated binding with serum albumins.16, 17

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and human serum albumin (HSA) have 2 and 1 tryptophan residues, respectively.18, 19 Both BSA and HSA have one tryptophan in a binding pocket of subdomain IIA, where warfarin binds, while the other tryptophan on BSA is on the surface of the protein. Fluorescence spectroscopy completed on a Shimadzu RF-1501 spectrofluorophotometer. Fluorescence spectra of tryptophan residues were collected using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm, to reduce contributions from tyrosine residues, and scanning emission wavelengths from 300 nm to 400 nm. Instrument sensitivity was set to low and 10 nm spectral bandwidth was used for detection. Serum albumin was at a constant final concentration of 1.87 µM in 20 mM MOPS with or without 154 mM NaCl (or 0.9% w/v NaCl). This concentration of saline was chosen both to understand the electrostatic nature of the interactions and due to being isosmotic with blood, and indicative of physiologic conditions. Polymer preparations in the same buffer were added to protein to achieve final concentrations over the range from 0.05 µM to 100 µM. Mixtures were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C prior to recording fluorescence spectra. The Stern-Volmer quenching constant was determined using the Stern-Volmer equation (1):

| (1) |

where I0 is the unquenched fluorescence, I is the fluorescence at concentration [Q] of polymer, and KSV is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant.20 The coefficient of determination (R2) for linear regression are presented in the supplement (Table S1).

Linear regression statistics were used to determine when the slopes were statistically non-zero. Statistical analysis of Stern-Volmer constants was completed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc for multiple t-test comparison. Statistical difference was recognized for p < 0.05.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The titration of polymeric micelles into proteins was performed using the Microcal VP-ITC (Malvern). All samples were be prepared in 20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl buffer and prewarmed to 37°C. Titrations were carried out with a first injection of 2 μL, followed by 26 injections of 10 μL with a duration of 20 seconds with a 180 second interval between injections. The first injection was eliminated for analysis. The final ITC curve was corrected by subtracting the heat of dilution and demicellization from the titration of micelles into buffer. The data was analyzed with Microcal Origin Software.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Samples were prepared in 76 mM sodium phosphate buffer (I = 174 mM), pH 7.0. Serum albumin was at a constant final concentration of 1.8 µM and mixed with 3.1 – 100 µM block copolymers. To disrupt serum albumin structure, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added to achieve a final concentration of 2% w/v. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C prior to measurements. The secondary structure of protein was determined using a Jasco J-815 circular dichroism spectrometer using a 0.1 mm path length quartz cell. Continuous wavelength scans were collected from 190–300 nm with 1 nm band width, 2 s response time, and 100 nm/min scan speed. Five measurements were taken for each spectrum. Each spectrum was corrected using reference solution of buffer or polymer in buffer.

Results

Micelle Characterization

Despite the difference in molecular weight, mPEG-LA and mPEG-CL polymers produced micelles with similar diameters of 24.2 ± 0.6 and 25.0 ± 0.2 nm, respectively (Table 1, Figure S1). mPEG-DSPE polymers produced the smaller micelles with a diameter of 14.7 ± 1.9 nm (Table 1, Figure S1). mPEG-CL had a lower CMC at 3.43 ± 0.7 μg/mL, compared to mPEG-DSPE and mPEG-LA which had CMCs of 15.8 ± 2.1 and 14.9 ± 10.7 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1, Figure S2). The zeta potentials of micelles are listed in Table 1.

Steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy

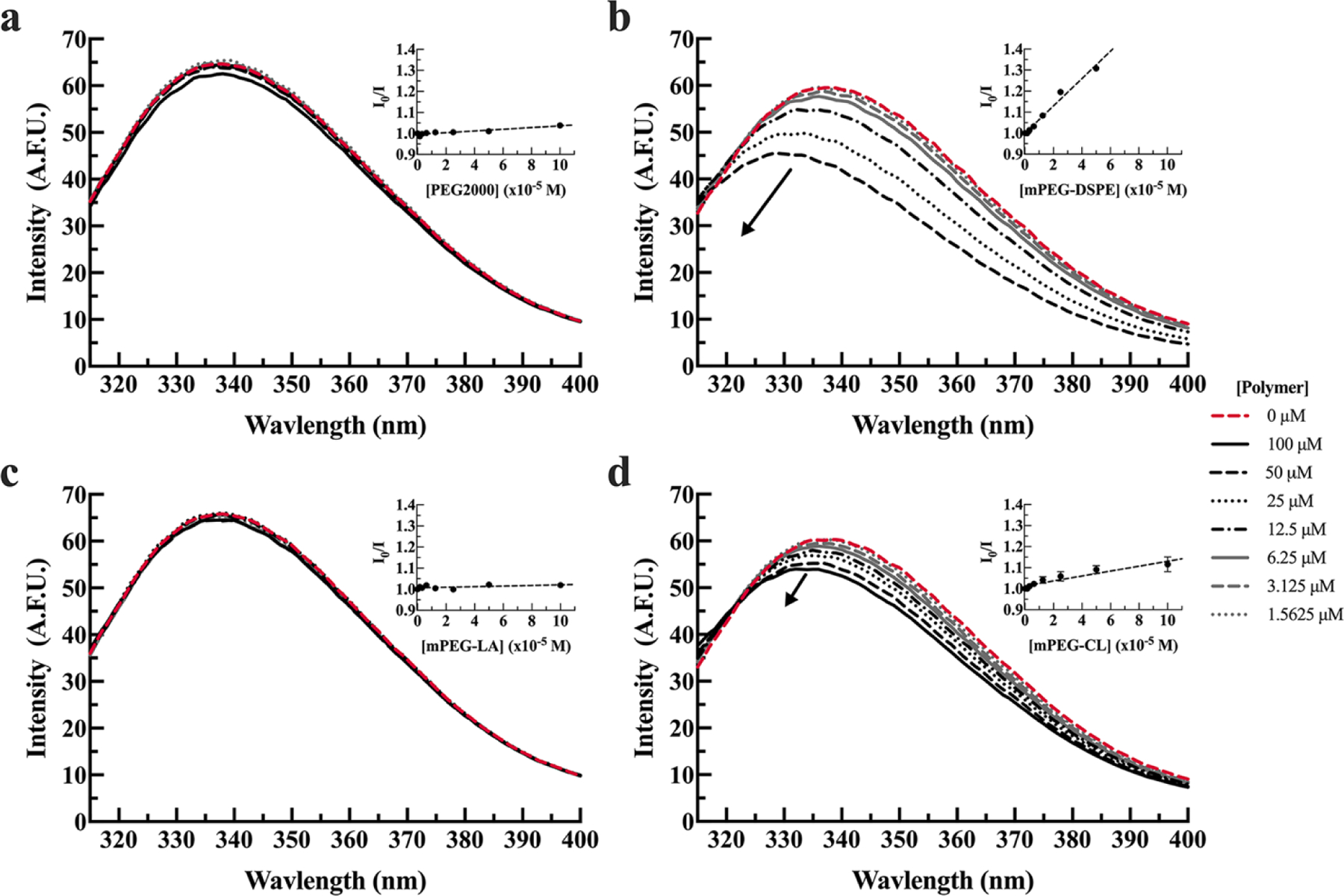

PEG2000 (Figure 1a) did not interact with BSA, and mPEG-DSPE demonstrated significant interactions with BSA as observed by fluorescence quenching and shift (Figure 1b) under these conditions. BSA did not interact with mPEG-LA (Figure 1c) under the conditions, while mPEG-CL demonstrated fluorescence quenching (Figure 1d). The KSV was measured to be approximately 4 times greater for mPEG-DSPE than mPEG-CL (Table 2).

Figure 1. BSA tryptophan fluorescence in the presence (solid lines) or absence (dashed red line) of PEG2000 (a), mPEG-DSPE (b), mPEG-LA (c), and mPEG-CL (d) in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.0 buffer. BSA (1.8 µM) was incubated with 1.5, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µM polymer.

The arrows indicate increasing polymer concentrations. Spectra are presented as the average of three measurements. Inset graphs are the corresponding Stern-Volmer plots and are presented as the average of three measurements plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Table 2.

Stern-Vomer constant (KSV, mM−1) for BSA and HSA in MOPS-buffered solution and MOPS-buffered saline.

| KSV (mM−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA |

HSA |

|||

| Polymer | 20 mM MOPS |

20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl | 20 mM MOPS |

20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl |

|

|

|

|||

| PEG2000 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| mPEG-DSPE | 6.51 ± 0.40 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 2.97 ± 0.63 | ns |

| mPEG-LA | ns | ns | 1.25 ± 0.13 | ns |

| mPEG-CL | 1.17 ± 0.17 | 2.50 ± 0.48 | 9.86 ± 1.65 | 3.76 ± 0.71 |

ns indicates values were not significantly non-zero.

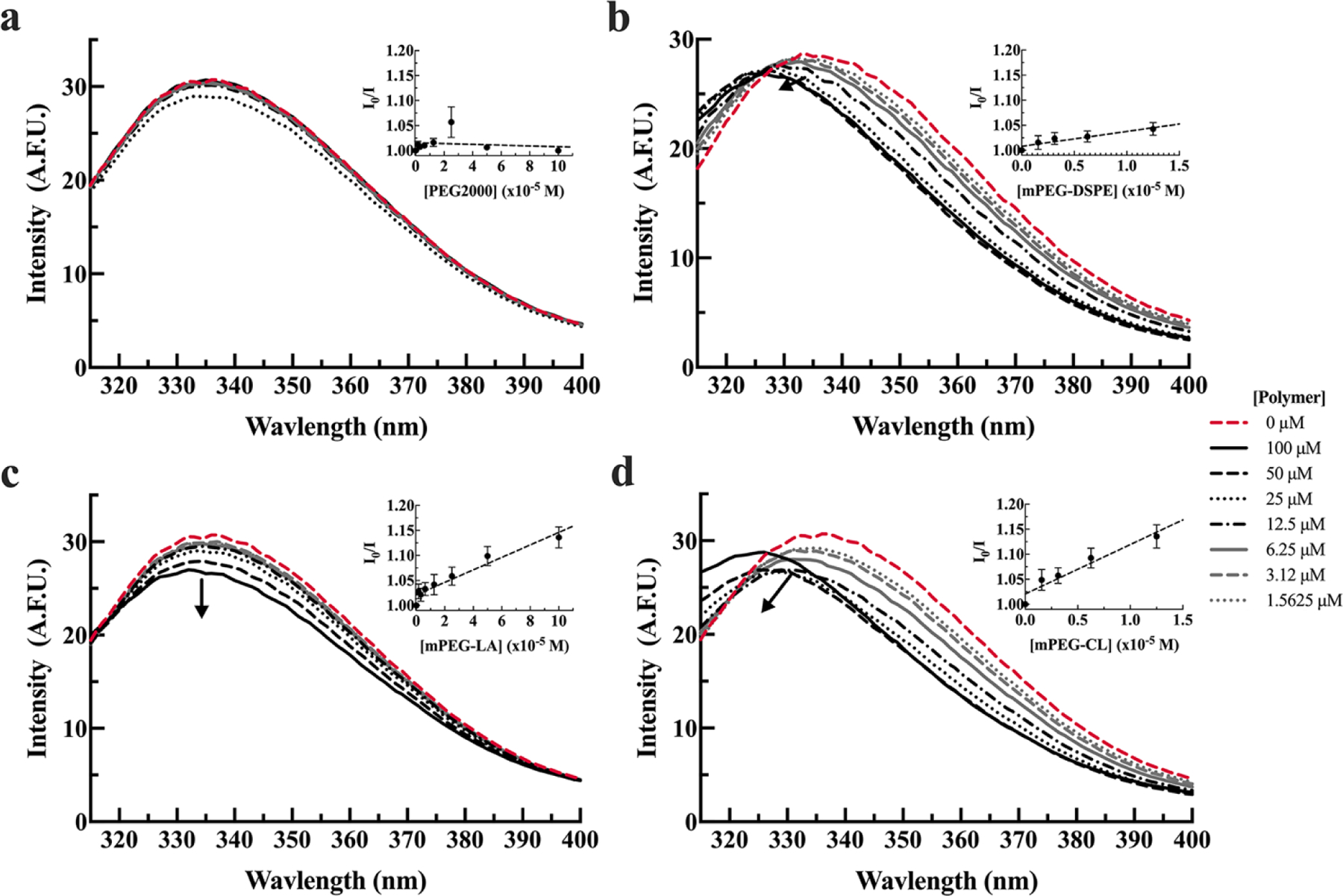

Furthermore, BSA fluorescent spectra maxima are blue-shifted in the presence of mPEG-DSPE and mPEG-CL (Figure 1b,d). A blue shift in tryptophan spectrum suggests tryptophan residues are in transitioning to more hydrophobic environment.21 The HSA-polymer binding behavior in 20 mM MOPS was not consistent with BSA. HSA does not demonstrate an interaction with PEG (Figure 2a). HSA was observed to interact with mPEG-DSPE, mPEG-CL, and mPEG-LA (Figure 2b-d). Unlike BSA, mPEG-CL had a stronger interaction with HSA that was approximately 3 times greater than mPEG-DSPE and approximately 8 times greater than mPEG-LA, as determined by their respective KSV (Table 2).

Figure 2. Tryptophan fluorescence of HSA in the presence (solid lines) or absence (dashed red line) of PEG2000 (a), mPEG-DSPE (b), mPEG-LA (c), and mPEG-CL (d) in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.0 buffer.

HSA (1.8 µM) was incubated with 1.5, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 µM polymer. The arrow indicates increasing polymer concentrations. Spectra are presented as the average of three measurements. Inset graphs are the corresponding Stern-Volmer plots and are presented as the average of three measurements plus or minus the standard error.

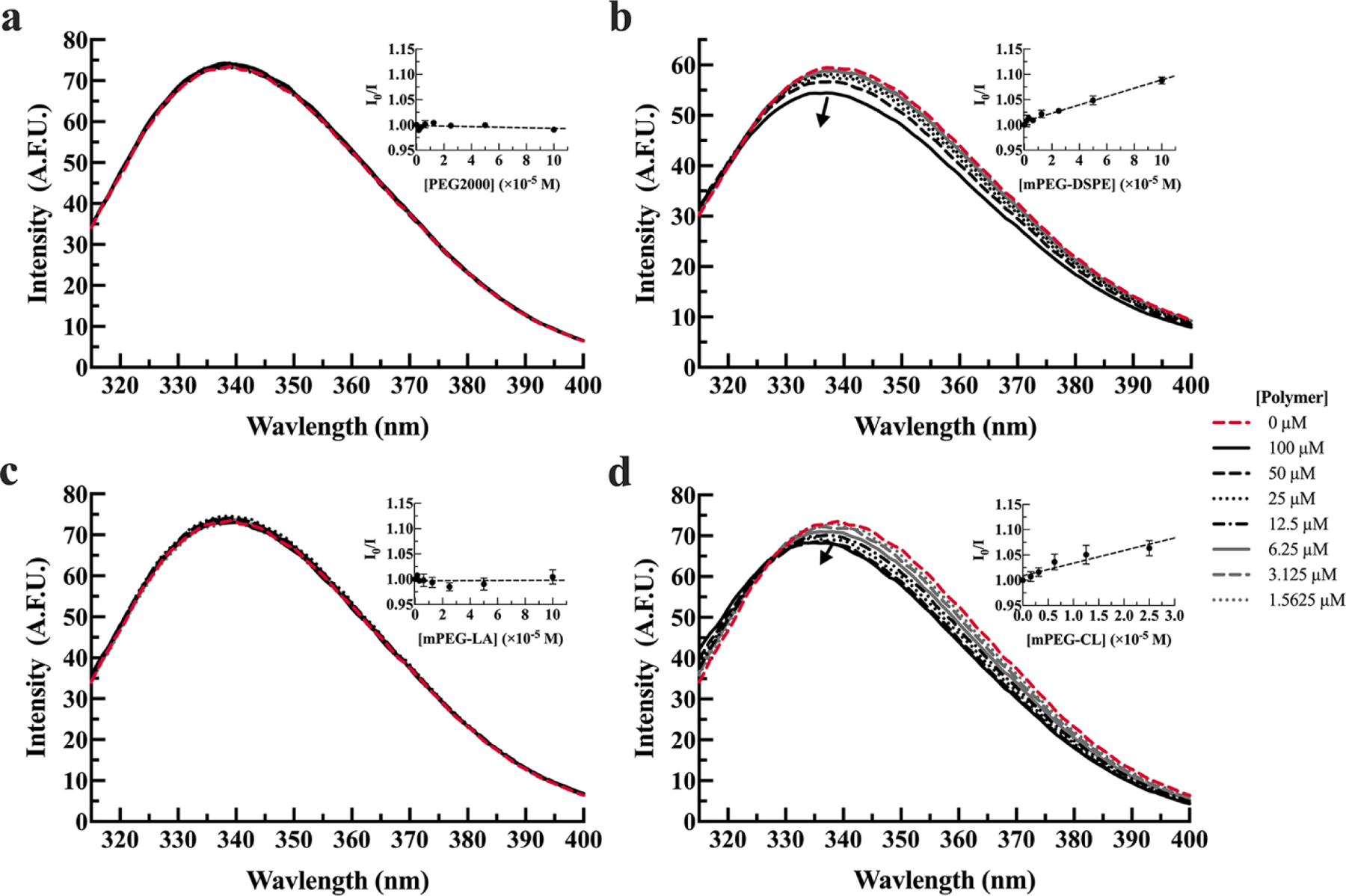

Binding of serum albumins with block copolymers was next investigated under higher salt conditions (20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl) as varying ionic strength solutions may inform the understanding of binding interactions being driven by hydrophobic interactions or electrostatic intermolecular forces.22, 23 For BSA, higher ionic strength conditions resulted in similar interactions to low ionic strength conditions (p = 0.10) (Table 2). In the presence of high ionic strength conditions, there is a trend for weaker interactions between mPEG-DSPE and BSA (Figure 3b) compared to low ionic strength conditions, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.69).

Figure 3. Tryptophan fluorescence of BSA in the presence (solid lines) or absence (dashed red line) of PEG2000 (a), mPEG-DSPE (b), mPEG-LA (c), and mPEG-CL (d) in 20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 buffer.

BSA (1.8 µM) was incubated with 1.5, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 µM polymer. The arrow indicates increasing polymer concentrations. Spectra are presented as the average of three measurements. Inset graphs are the corresponding Stern-Volmer plots and are presented as the average of three measurements plus or minus the standard error of the mean.

As previously observed in low ionic strength conditions, BSA was not predictive for micelle interactions with HSA. HSA fluorescence did not change in the presence of PEG2000, mPEG-DSPE, and mPEG-LA (Figure 4a-c). Only mPEG-CL demonstrated quenching of HSA tryptophan fluorescence, accompanied by blue-shifted curve (Figure 4b) and ionic strength did have a significant impact on the KSV (p = 0.0024). The binding of HSA to mPEG-CL was approximately 3 times weaker in high ionic strength conditions compared to lower ionic strength conditions (p = 0.039) (Table 2).

Figure 4. Tryptophan fluorescence of HSA in the presence (solid lines) or absence (dashed red line) of PEG2000 (a), mPEG-DSPE (b), mPEG-LA (c), and mPEG-CL (d) in 20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 buffer.

HSA (1.8 µM) was incubated with 1.5, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 µM polymer. The arrow indicates increasing polymer concentrations. Spectra are presented as the average of three measurements. Inset graphs are the corresponding Stern-Volmer plots and are presented as the average of three measurements plus or minus the standard error of the mean.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The fluorescence-based assay is limited to assessing binding to serum albumin where changes in the relative fluorescent intensity of the tryptophan residue(s) changes, most likely in one of the six known binding sites on serum albumin.24 To investigate complete interactions of HSA with block copolymers, we investigated the thermodynamic interactions using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). We focused on examining serum albumin (HSA or BSA) interactions with mPEG-CL or mPEG-LA in physiologically relevant conditions, in 20 mM MOPS and 154 mM NaCl.

The results from ITC confirm steady state fluorescence results for HSA in 20 mM MOPS and 154 mM NaCl buffer (Figure 5a, Figure S3a). Titration of mPEG-CL into HSA resulted in an exothermic interaction (Figure S4a). while mPEG-LA resulted in no significant change in heat (Figure S4b). Titration of BSA yielded similar results to HSA (Figure 5b, Figure S3b). Titration of mPEG-CL into BSA resulted in an exothermic interaction (Figure S5a), while mPEG-LA demonstrated no measurable interactions (Figure S5b). From this, we conclude that HSA and BSA were observed to interact with mPEG-CL but not with mPEG-LA. The thermodynamic parameters from the fit of mPEG-CL titration into HSA are −2.13×106 cal/mol, −1.87×103 cal/mol, −6.88 ×103 cal/mol∙K for ρH°, ρG°, ρS°, respectively. The thermodynamic parameters from the fit of mPEG-CL titration into BSA are −1.66×105 cal/mol, −1.55×103 cal/mol, −5.27×102 cal/mol∙K for ρH°, ρG°, ρS°, respectively.

Figure 5. Isothermal titration calorimetry of the titration of mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA block copolymer micelles into HSA (a) or BSA (b) at 37°C in 20 mM MOPS, 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.0.

Average values ± SEM is shown for 3 replicates.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

HSA and BSA were analyzed using circular dichroism spectroscopy to examine potential changes in protein secondary structure resulting from interactions with block copolymers. The CD spectra of serum albumins were characterized by a double trough at 208 and 220 nm, characteristic of alpha-helices (Figure 6). The ionic surfactant SDS, commonly used to disrupt and denature protein structure, was mixed with a serum albumin as a control for protein disruption.25 The presence of SDS reduced mean residue ellipticity of HSA and BSA, demonstrating changes to protein secondary structure.25 The presence of mPEG-CL and mPEG-LA did not have any significant effects on HSA CD spectrum at any of the tested block copolymer micelle concentrations (3.125 – 100 µM).

Figure 6. Circular dichroism spectra of 1.8 μM HSA (a,b) or BSA (c,d) in the absence and presence of various concentrations of mPEG-CL (a,c) and mPEG-LA (b,d) block copolymer micelles in 76 mM sodium phosphate buffer (I = 174 mM), pH 7.0.

Spectra for HSA in the presence of 2% (w/v) SDS. Spectra are shown as the average of three measurements.

Discussion

PEG on the surface of particles, including micelles, reduces the total accumulated protein in the corona, but proteins still interact with the hydrophobic core or PEG corona itself.24, 26 PEG interacts with proteins, with serum albumin being the most observed and best characterized.14, 27 However, we did not observe PEG2000 quenching tryptophan fluorescence or calorimetric interactions of HSA or BSA under any of our examined conditions. The PEG-protein interaction strength has been shown to positively correlate with molecular weight of the PEG and the 2000 g/mol PEG having limited, if any, interaction.24 Only weak interactions have been demonstrated between HSA and PEG3000 compared to PEG5000.14 PEG3000 also demonstrated a preference for the more hydrophilic HSA as compared to BSA, suggesting that hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic intermolecular forces are important in PEG-protein interactions.14 Using molecular dynamics simulation of N-terminal conjugated PEG-BSA, PEG chains around 10 kDa in weight were required to promote significant PEG-protein interactions,27 although the terminal conjugation would be expected to influence the interactions. The most favorable PEG-amino acid interactions were hydrogen bonds formed with lysine residues although the favorability was dependent upon the environment created by surrounding residues. Given that interactions between serum albumin and PEG are molecular weight dependent, it is likely PEG2000 is below the molecular weight threshold for strong interactions and why we do not observe any interaction between soluble PEG2000 and albumin. Therefore, serum albumin interactions with block copolymers are most likely dependent upon interactions with the hydrophobic block.

Serum albumin interacts with many hydrophobic molecules and is a known lipid carrier in the blood. In addition to natural lipids, serum albumin interacts with synthetic or modified lipids, including mPEG-DSPE.16 Micelles formed with PEG-DSPE break up in the presence of BSA and human plasma.16, 17 Based on this knowledge, mPEG-DSPE was chosen as a positive control for tryptophan quenching to allow an understanding of how a synthetic diblock polymer interacts with serum albumin. Our study confirmed mPEG-DSPE binds BSA and HSA, where protein binding strength decreased upon increasing buffer ionic strength. A drop in binding strength, KSV, with increasing ionic strength suggests salt shielding at the binding site, indicating electrostatic intermolecular forces drive binding of mPEG-DSPE to serum albumins.22 However, environmental effects on micelle behavior may influence protein interactions with mPEG-DSPE. Micelles formed from mPEG-DSPE in water have smaller aggregation number, smaller micelle diameters, and larger CMC when compared to mPEG-DSPE micelles in HEPES-buffered saline.28 Computational analysis of micelle PEG corona suggested a thicker PEG corona on mPEG-DSPE micelles in HEPES-buffered saline compared to micelles in water.28 Lower binding strength of mPEG-DSPE to serum albumin in high ionic strength conditions could result from better PEG coverage of the core of the micelle that inhibits protein interactions with the hydrophobic lipid tail of the molecule. The properties that determine aggregate number, CMC, and micelle size also dictate micelle kinetic activity.29 Less stable micelles with thinner PEG corona may result in unimers that are more dynamic and accessible for binding to proteins. This highlights the importance of understanding how solution conditions influence micelle-polymer interactions to better understand their influence on in vivo micelle performance.

The mPEG-LA micelles were only observed to interact with HSA in a low ionic strength environment. This suggests an interaction driven by electrostatic intermolecular forces and is consistent with lactic acid units binding HSA driven by van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding.22, 23 Weak interactions between HSA and mPEG-LA micelles may result from the more hydrophilic nature of PLA compared to PCL and DSPE or steric hinderance by methyl side groups of PLA. Despite high sequence homology between BSA and HSA, the tertiary structures are not equivalent. In the area containing the tryptophan residue in subdomain IIA, BSA contains a leucine at residue 237 which protrudes into the binding region more than the aspartic acid in HSA.22 This protrusion into the pocket may prevent mPEG-LA binding at the subdomain IIA site. As mPEG-LA did not have any detectable interactions with HSA in physiologic conditions, we would not expect mPEG-LA to interact with HSA in vivo. Specific interactions with HSA would not be expected to be the driving cause of mPEG-LA micelle instability in the blood.

The more hydrophobic mPEG-CL was observed to interact with BSA and HSA to varying degrees. BSA interacted with weaker bonds, i.e., lower KSV, compared to HSA. Buffer ionic strength influenced the binding of mPEG-CL to bovine and human serum albumin differently. The KSV increased with ionic strength for BSA, suggesting a hydrophobically-driven interaction; while the KSV decreased with ionic strength for HSA, suggesting an electrostatic-driven interaction.22 The finding suggests different intermolecular forces may be responsible for protein-polymer interactions. Thermodynamic analysis of the ITC results suggests that the interactions for both serum albumins and mPEG-CL are driven by hydrogen-bonding or electrostatic interactions. The discrepancy in the results of these two methods could a result from the limited sites protein fluorescence is able to interrogate compared to whole-protein interactions examined in ITC. It could be that sites containing tryptophans have different intermolecular forces driving interactions compared to total interactions over the whole protein. Murine albumin colocalized with the hydrophobic core or hydrophobic block of mPEG-CL both in vitro and in vivo.7 Based on these results, they proposed serum albumin binding to disassembled block copolymers as a mechanism of clearance for free unimers. However, the results were unclear as to whether BSA was binding free unimers or penetrating the PEG corona to interact with the micelle core. Interactions with the unimer and the micelle are both possible, and implicated in impacting thermodynamic and kinetic stability of micelles.30 Additionally, incubation of BSA with mPEG-CL micelles resulted in only a small fraction of total breakup of micelles, while, interestingly, serum and blood resulted in minimal micelle breakup.7 The cause of the discrepancy is unclear, but protein-polymer interactions clearly demonstrated a role promoting micelle disassembly.

Of note, our study was done with fatty-acid free serum albumins. Albumins would be expected to have competitive binding that may be dominated by the strong interacting endogenous lipids. Block copolymers are expected to bind to the same binding sites as prevalent lipids and other molecules in the blood, creating competition for those binding sites, and lowering the apparent binding of block copolymers for serum albumin binding. However, endogenous molecules may also allosterically bind proteins; altering the block copolymer binding sites on albumin to inhibit or enhance binding.31 Since mPEG-CL has been shown to colocalize with murine serum albumin in vivo, the presence of endogenous lipids may not inhibit mPEG-CL interactions with serum albumin.7 The more hydrophobic nature of PCL could logically better mimic the lipid binding and would be expected to bind more similar to the native lipids. Future studies need to be done to understand how endogenous lipids may affect binding to serum proteins and the impact this binding has on destabilizing drug-loaded polymeric micelles.

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed on N-terminal conjugated PEG-BSA system of varied molecular weights to understand how PEG chains interact with BSA.27 In those simulations, PEG formed hydrogen bonds with lysine residues present on the surface of the protein and hydrophobic residues on the solvent-accessible surface near the lysine could promote longer contact times between polymer and protein. The lysine residues were predicted to hydrogen bond with oxygens in the PEG chain. Given that PEG-lysine interaction, it is possible that the hydrophobic blocks containing oxygens could similarly form bonds with the surface of the protein. This interaction may alter protein conformation and cause tryptophan quenching observed in this study. If surface-mediated binding exists between block copolymers and serum albumin, ligands bound to serum albumin would not be expected to significantly diminish the interactions given the number of solvent-accessible lysine residues.

Ionic strength of the solution also determined the strength of the interaction between polymeric micelles and serum albumin. Ionic strength of the solution modulated the strength of binding, or effectively eliminate measurable interactions. Little investigation has been done to determine what interactions might exist between PCL and PLA and serum albumin, but if PCL and PLA can interact with surface-accessible lysine residues through hydrogen bonding,27 it could explain the effect of ions on interactions between albumin and block copolymers. Sodium chloride has been demonstrated to reduce the viscosity of concentrated BSA solutions presumably through electrostatic shielding of the surface of the protein thus weakening protein-protein interactions.32 This highlights the importance of understanding the effect of excipients on block copolymer-protein interactions as these interactions have been implicated in influencing micelle stability.33, 34

Conclusion

In this study, the interactions between bovine and human serum albumins and block copolymer micelles used in drug delivery were characterized. The presence of block copolymers did not cause denaturation of either BSA or HSA. Electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding appear to drive mPEG-CL interactions with both BSA and HSA. HSA only interacted with mPEG-LA in low ionic strength buffer, also suggesting an electrostatically driven interaction, but BSA did not elicit any measurable interactions with mPEG-L A. BSA was not consistently predictive of interactions for HSA demonstrating that caution should be used when using BSA to predict performance or in selecting the most stable formulations. BSA should not be utilized in the assessment of micelles and that bovine serum may not be appropriate for cell culture assessment of polymeric materials. The improved understanding of the interactions that exist between polymeric micelles and proteins provided by this study will help guide innovation of micelle formulations for improved drug delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Timothy D. Langridge, Karol Sokolowski, and Angeliki Andrianopoulou for their feedback and assistance. We would like to acknowledge that portions of this work were carried out at the Biophysical Core via the Research Resources Center (RRC) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and thank Dr. Hyun Lee and the core for their guidance and assistance.

Funding Sources

Research reported in this investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant C06 RR015482 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH and was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award R21 EB022374. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CD

circular dichroism

- CMC

critical micelle concentration

- Cy5.5

cyanine5.5

- ΔG

Gibb’s free energy change for the interaction

- ΔH

enthalpy change for the interaction

- ΔS

entropy change for the interaction

- DSPE

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- HEPES

2-[4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethane-1-sulfonic acid

- HSA

human serum albumin

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- KSV

Stern-Volmer quenching constant

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- mPEG-CL

methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol-block-ε-caprolactone)

- mPEG-DSPE

poly(ethylene glycol)-N-1,2-distearyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- mPEG-LA

methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol-block-lactide)

- MWCO

molecular weight cut-off

- PCL

polycaprolactone

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEG2000

poly(ethylene glycol) MW = 2000 g/mol

- PEG-PCL-Cy5.5

poly(ethylene glycol-block-ε-caprolactone)-cyanine5.5

- PLA

polylactide

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- T

temperature

- US FDA

United States Food and Drug Administration

- UV-VIS

ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy

Footnotes

Competing Interest and/or Conflicts of Interests

Declarations of interest: none.

Supporting Information Available

The following files are available free of charge: supplementary figures and table to this article, specifically size distributions of the micelles, critical micelle concentration measurement, Stern-Volmer fit coefficients of determination (R2), and isothermal calorimetry titration heat and enthalpy curves.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Cabral H; Kataoka K Progress of drug-loaded polymeric micelles into clinical studies. J Control Release 2014, 190, 465–476, Review. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim T-Y; Kim D-W; Chung J-Y; Shin SG; Kim S-C; Heo DS; Kim NK; Bang Y-J Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of Genexol-PM, a Cremophor-Free, Polymeric Micelle-Formulated Paclitaxel, in Patients with Advanced Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10 (11), 3708–3716. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park IH; Sohn JH; Kim SB; Lee KS; Chung JS; Lee SH; Kim TY; Jung KH; Cho EK; Kim YS; et al. An Open-Label, Randomized, Parallel, Phase III Trial Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Polymeric Micelle-Formulated Paclitaxel Compared to Conventional Cremophor EL-Based Paclitaxel for Recurrent or Metastatic HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2017, 49 (3), 569–577. DOI: 10.4143/crt.2016.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KS; Chung HC; Im SA; Park YH; Kim CS; Kim SB; Rha SY; Lee MY; Ro J Multicenter phase II trial of Genexol-PM, a Cremophor-free, polymeric micelle formulation of paclitaxel, in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008, 108 (2), 241–250. DOI: 10.1007/s10549-007-9591-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller T; Hill A; Uezguen S; Weigandt M; Goepferich A Analysis of immediate stress mechanisms upon injection of polymeric micelles and related colloidal drug carriers: implications on drug targeting. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13 (6), 1707–1718, Review. DOI: 10.1021/bm3002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen SC; Chan DPY; Shoichet MS Polymeric micelle stability. Nano Today 2012, 7 (1), 53–65, Review. DOI: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X; Wang G; Zhang H; Hu S; Liu X; Tang J; Shen Y The Blood Clearance Kinetics and Pathway of Polymeric Micelles in Cancer Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2018, 12 (6), 6179–6192. DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H; Kim S; He W; Wang H; Low PS; Park K; Cheng J-X Fast Release of Lipophilic Agents from Circulating PEG-PDLLA Micelles Revealed by in Vivo Förster Resonance Energy Transfer Imaging. Langmuir 2008, 24 (10), 5213–5217. DOI: 10.1021/la703570m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esparza K; Onyuksel H Development of co-solvent freeze-drying method for the encapsulation of water-insoluble thiostrepton in sterically stabilized micelles. Int J Pharm 2019, 556, 21–29. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langridge TD; Gemeinhart RA Toward understanding polymer micelle stability: Density ultracentrifugation offers insight into polymer micelle stability in human fluids. J Control Release 2019, 319, 157–167. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J; Owen SC; Shoichet MS Stability of Self-Assembled Polymeric Micelles in Serum. Macromolecules 2011, 44 (15), 6002–6008. DOI: 10.1021/ma200675w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalyanasundaram K; Thomas JK Environmental effects on vibronic band intensities in pyrene monomer fluorescence and their application in studies of micellar systems. J Am Chem Soc 1977, 99 (7), 2039–2044. DOI: 10.1021/ja00449a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguiar J; Carpena P; Molina-Bolívar JA.; Carnero Ruiz C. On the determination of the critical micelle concentration by the pyrene 1:3 ratio method. J Colloid Interface Sci 2003, 258 (1), 116–122. DOI: 10.1016/s0021-9797(02)00082-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekale L; Agudelo D; Tajmir-Riahi HA The role of polymer size and hydrophobic end-group in PEG-protein interaction. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2015, 130, 141–148. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J; Zhao C; Lin W; Hu R; Wang Q; Chen H; Li L; Chen S; Zheng J Binding characteristics between polyethylene glycol (PEG) and proteins in aqueous solution. J Mater Chem B 2014, 2 (20), 2983–2992. DOI: 10.1039/c4tb00253a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castelletto V; Krysmann M; Kelarakis A; Jauregi P Complex Formation of Bovine Serum Albumin with a Poly(ethylene glycol) Lipid Conjugate. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8 (7), 2244–2249. DOI: 10.1021/bm070116o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastantin M; Missirlis D; Black M; Ananthanarayanan B; Peters D; Tirrell M Thermodynamic and Kinetic Stability of DSPE-PEG(2000) Micelles in the Presence of Bovine Serum Albumin. J Phys Chem B 2010, 114 (39), 12632–12640. DOI: 10.1021/jp1001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugio S; Kashima A; Mochizuki S; Noda M; Kobayashi K Crystal structure of human serum albumin at 2.5 Å resolution. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 1999, 12 (6), 439–446. DOI: 10.1093/protein/12.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majorek KA; Porebski PJ; Dayal A; Zimmerman MD; Jablonska K; Stewart AJ; Chruszcz M; Minor W Structural and immunologic characterization of bovine, horse, and rabbit serum albumins. Mol Immunol 2012, 52 (3–4), 174–182. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quenching of Fluorescence. In Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Lakowicz JR Ed.; Springer; US, 2006; pp 277–330. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protein Fluorescence. In Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Lakowicz JR; Springer; US, 2006; pp 529–575. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh S; Dey J Binding of Fatty Acid Amide Amphiphiles to Bovine Serum Albumin: Role of Amide Hydrogen Bonding. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119 (25), 7804–7815. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rafols C; Amezqueta S; Fuguet E; Bosch E Molecular interactions between warfarin and human (HSA) or bovine (BSA) serum albumin evaluated by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), fluorescence spectrometry (FS) and frontal analysis capillary electrophoresis (FA/CE). J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018, 150, 452–459. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gref R; Lück M; Quellec P; Marchand M; Dellacherie E; Harnisch S; Blunk T; Müller RH ‘Stealth’ corona-core nanoparticles surface modified by polyethylene glycol (PEG): influences of the corona (PEG chain length and surface density) and of the core composition on phagocytic uptake and plasma protein adsorption. Colloids Surf B 2000, 18 (3), 301–313. DOI: 10.1016/S0927-7765(99)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anand U; Mukherjee S Reversibility in protein folding: effect of beta-cyclodextrin on bovine serum albumin unfolded by sodium dodecyl sulphate. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2013, 15 (23), 9375–9383. DOI: 10.1039/c3cp50207d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Castro CE; Mattei B; Riske KA; Jager E; Jager A; Stepanek P; Giacomelli FC Understanding the structural parameters of biocompatible nanoparticles dictating protein fouling. Langmuir 2014, 30 (32), 9770–9779. DOI: 10.1021/la502179f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munasinghe A; Mathavan A; Mathavan A; Lin P; Colina CM Molecular Insight into the Protein-Polymer Interactions in N-Terminal PEGylated Bovine Serum Albumin. J Phys Chem B 2019, 123 (25), 5196–5205. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vukovic L; Khatib FA; Drake SP; Madriaga A; Brandenburg KS; Kral P; Onyuksel H Structure and dynamics of highly PEG-ylated sterically stabilized micelles in aqueous media. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133 (34), 13481–13488. DOI: 10.1021/ja204043b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund R; Willner L; Richter D Kinetics of Block Copolymer Micelles Studied by Small-Angle Scattering Methods. In Controlled Polymerization and Polymeric Structures. Advances in Polymer Science, Abe A, Lee K-S, Leibler L, Kobayashi S Eds.; Vol. 259; Springer, 2013; pp 51–158. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee IY; McMenamy RH Location of the medium chain fatty acid site on human serum albumin. Residues involved and relationship to the indole site. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1980, 255 (13), 6121–6127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee IY; McMenamy RH Location of the medium chain fatty acid site on human serum albumin. Residues involved and relationship to the indole site. J Mol Biol 1980, 255 (13), 6121–6127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue N; Takai E; Arakawa T; Shiraki K Arginine and lysine reduce the high viscosity of serum albumin solutions for pharmaceutical injection. J Biosci Bioeng 2014, 117 (5), 539–543. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y; Yue Z; Xie J; Wang W; Zhu H; Zhang E; Cao Z Micelles with ultralow critical micelle concentration as carriers for drug delivery. Nat Biomed Eng 2018, 2 (5), 318–325. DOI: 10.1038/s41551-018-0234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu HJ; Han Y; Cheong M; Kral P; Hong S Dendritic PEG outer shells enhance serum stability of polymeric micelles. Nanomedicine 2018, 14 (6), 1879–1889. DOI: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.