Abstract

Seasonal influenza virus infections cause a substantial number of deaths each year. While zanamivir (ZAN) is efficacious against oseltamivir-resistant influenza strains, the efficacy of the drug is limited by its route of administration, oral inhalation. Herein, we present the development of a hydrogel-forming microneedle array (MA) in combination with ZAN reservoirs for treating seasonal influenza. The MA was fabricated from Gantrez® S-97 crosslinked with PEG 10,000. Various reservoir formulations included ZAN hydrate, ZAN hydrochloric acid (HCl), CarraDres™, gelatin, trehalose, and/or alginate. In vitro permeation studies with a lyophilized reservoir consisting of ZAN HCl, gelatin, and trehalose resulted in rapid and high delivery of up to 33 mg of ZAN across the skin with delivery efficiency of up to ≈75% by 24 hours. Pharmacokinetics studies in rats and pigs demonstrated that a single administration of a MA in combination with a CarraDres™ ZAN HCl reservoir offered a simple and minimally invasive delivery of ZAN into the systemic circulation. In pigs, efficacious plasma and lung steady-state levels of ~120 ng/mL were reached within 2 hours and sustained between 50 – 250 ng/mL over 5 days. MA-enabled delivery of ZAN could enable a larger number of patients to be reached during an influenza outbreak.

Keywords: Controlled release delivery, influenza treatment, PK/PD driven drug delivery, preclinical pharmacokinetics, swellable microarray patches, zanamivir

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Seasonal influenza epidemics affect the general population, leading to as many as 650,000 deaths and even higher mortality during pandemics [1–3]. Three major genera of influenza viruses can infect humans; type A, B, and C. Influenza type C viruses typically cause mild disease, whereas types A and B are responsible for seasonal epidemics. Influenza type A is capable of infecting a variety of hosts, with its natural reservoir being wild aquatic birds, however, humans are the primary reservoir of type B and C. Influenza A has been responsible for all human influenza pandemics in the last century, as zoonotic transmission allows for sporadic antigenic shifts that introduce novel influenza A virus strains or genes into the human population, for which we lack immunity [4–6]. Furthermore, new highly pathogenic strains of influenza A cause major pandemic outbreaks, which kill tens of millions of people, such as H5N1 (case-fatality rate of 59%) and H7N9 (case-fatality rate of 28%) [7–9], with severe economic repercussions amounting to over 330 billion dollars [10].

The introduction of a few changes in avian influenza dramatically increases its ability to spread between mammals [11,12], which causes widespread concerns over modified influenza viruses as bioterrorism agents. Antigenic drift, the buildup of several genetic mutations, may give rise to new strains of influenza that escape immunity from previous vaccination or exposure. Therefore, each year seasonal influenza vaccines must be antigenically matched to the virus strains predicted to be predominantly circulating among humans [5]. Poorly matched vaccines and seasonal strains result in poor efficacy, but even when there is a good match the efficacy is only 40 to 60% [6]. The seasonal influenza threat is now further exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic with newly emerging strains. Solutions to treat and prevent the flu will help minimize the severity of potential co-infections. As a result of the ineffectiveness of the current vaccines [13], pharmacotherapy is still critically important. Currently, the use of small molecule drugs to treat seasonal influenza is only partially effective [14], due to some strains exhibiting resistance to the adamantanes, the neuraminidase inhibitor (NI) oseltamivir (Tamiflu®), and the newly approved baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza®) [15]. However, zanamivir (ZAN, Relenza®) uniquely remains efficacious and is thought to exhibit a lower propensity in promoting the emergence of fit mutants when resistance does occurs [16]. ZAN, originally approved by the FDA for commercial distribution in 1999, has a well-established safety and efficacy profile. Orally-inhaled ZAN is indicated for the management of uncomplicated influenza type A and B infections. To achieve efficacy, it must be administered within 2 days after symptoms present, however, it is also indicated as a prophylactic treatment for those older than 5 years. While the safety profile of this drug is excellent, its therapeutic impact is severely limited by its administration route. Oral inhalation is associated with significant pharmacokinetic variability and is contraindicated in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Through the compassionate use program, ZAN may also be administered via intravenous infusion for the management of complicated and potentially life-threatening influenza infections [17–19]. However, this route of administration requires the aid of a healthcare professional which adds to the overall treatment cost. Furthermore, Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling has revealed that the driving PD parameter for ZAN, which has a short half-life of 2.5 hours in humans after IV administration, is the time above IC50, reported at 1.4 ng/ml [20]. Longer half-lives of ZAN simulated in a Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM) demonstrate that when the half-life of ZAN is increased to 8 hours the AUC, instead of IC50, becomes the PD driver [20]. The HFIM is an elegant in vitro system, where Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells are grown in hollow tubings and infected with an influenza virus. An antiviral drug solution can then be continuously perfused through the system with increasing concentrations to simulate plasma concentration-time profiles. HFIM is a highly effective screening approach to derive the most effective treatment profile.

The findings from the HFIM and the poor patient compliance provide a strong rationale to deliver ZAN continuously and with greater convenience for patients, in order to maximize the utility of this therapeutic as an effective treatment of seasonal influenza. Cumbersome dry-powder inhalations could be replaced by a patient-administered, minimally invasive microneedle array patch (MAP). With this approach, a drug reservoir is placed on top of the microneedle array (MA) and secured with a patch upon skin application [21]. MAs can be classified as solid, coated, dissolving, hollow, or hydrogel-forming depending on their mechanism of drug delivery. Hydrogel-forming MAs are fabricated from crosslinked polymers. Upon skin application, MAs form micron size aqueous pores that can be exploited for transdermal delivery of therapeutics, from small molecules [22] to macromolecules [23]. Upon skin insertion, the needles trigger the movement of interstitial skin fluid into the gel network of the MA. This fluid uptake expands the gel network and creates fluid-filled conduits, thereby allowing drug molecules to diffuse into the dermis and, subsequently, the lymph and systemic circulation [24]. In fact, intradermal drug delivery and uptake by the lymph distributes the therapeutic rapidly to the lungs [25], a feature that is an important advantage for the treatment of the flu. Furthermore, this drug delivery strategy can be optimized via the use of rapidly dissolving reservoirs such as lyophilized (LYO) wafers, directly compressed tablets, and even polymeric films in order to attain the required drug delivery profile [22].

In the current work, we detail the preparation and evaluation of various drug reservoirs, loaded with the neuraminidase inhibitor ZAN, for systemic delivery via hydrogel-forming MAs. The desired target product profile was a five-day continuous treatment course following a single application of the fully-assembled MAP. The permeation of ZAN from various reservoir formulations across a range of thermally crosslinked hydrogel systems was evaluated using an in vitro permeation assay. Furthering this, in vivo pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in rats and minipigs to evaluate MA-enabled delivery of these reservoirs over up to five days. The ZAN hydrogel-forming MAP proposed here is positioned to replace the approved Relenza® diskhaler, and offers the promise of easier administration to a broader patient population, and better patient compliance. The proposed system adds tremendous value to the growing need for therapeutics against influenza. Furthermore, the CDC recently released updated guidelines to encourage prophylactic treatment of influenza in “at risk” patients, which include the very young, the elderly, and anyone more susceptible to an influenza infection due to a pre-existing condition [7]. This could significantly expand the therapeutic, as well as prophylactic, benefit of our ZAN MAP formulation during an influenza outbreak.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

ZAN monohydrate (Hyd) was acquired from Pharmacore Corporation (Shanghai, China). Trehalose, citric acid monohydrate, sorbitol, gelatin, and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) 87–89% hydrolyzed MW 85,000–124,000 D, were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK). Sodium alginate and benzyl alcohol were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Plasdone® or poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) K-29/32 and Gantrez® S-97, a co-polymer of methyl vinyl ether and maleic acid (PMVE/MA) with a molecular weight of 58 kDa, were procured from Ashland (Kidderminster, UK). All other chemicals and materials were of analytical grade.

2.2. Animals and Ethics Statement

All mice and rat studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Utah State University and TSRL, Inc. Studies were conducted according to federal regulations and institutional policies. Upon arrival, all animals were visually inspected, weighed, and determined to be free of abnormalities and illness and then again at study initiation. Animals were group- or individually-housed in wire-bottom cages rested on a plastic pan, with sufficient bedding to cover the wire mesh, or in solid cages with cellulose bedding. Enrichment was provided in the form of nestlets and/or cardboard Bio-tunnels.

The minipig study at Charles River Laboratories complied with all applicable sections of the Final Rules of the Animal Welfare Act regulations (Code of Federal Regulations, Title 9), the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Research Council. Upon arrival, all animals were visually inspected, weighed, and determined to be free of abnormalities and illness and then again at study initiation. The minipigs were pair-housed by sex. The animals were housed in pens on Aspen wood shavings, on raised floor caging, or in stainless steel cages with stainless steel or plastic-coated flooring. Pieces of fruit or vegetables and other enrichment food may be offered on a regular basis during the acclimation period.

2.3. Solute Diffusion Studies

2.3.1. Preparation of the Hydrogel Polymer Films

Three different hydrogel films were prepared in this study which consisted of (a) Gantrez® S-97-PEG 10,000, (b) PVP-PVA citric acid, and (c) Gantrez® S-97-PEG 10,000-sorbitol. These films were prepared based on previously reported methods [22,26,27]. Briefly, an aqueous blend of polymer and osmolytes outlined in Table 1 were mixed and casted onto a flat surface that had been lined with a siliconized-release liner. The mixtures were then dried at room temperature for 48 hours, after which the polymer films were meticulously trimmed into smaller pieces (20 mm × 20 mm). The dried polymer films were then crosslinked in a thermostatically controlled oven at the required temperature and duration as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of hydrogel films.

| Hydrogel system | Composition | Crosslinking temperature (◦C) | Crosslinking time |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gantrez® S-97-PEG

10,000 |

20% Gantrez® S-97, 7.5% PEG 10,000 Da |

80 | 24 hours |

| PVP-PVA citric acid | 15% PVA, 10% PVP, 1.5% citric acid |

130 | 40 minutes |

|

Gantrez® S-97-PEG

10,000-sorbitol |

20% Gantrez® S-97, 7.5% PEG 10,000 Da, and 10% Sorbitol |

80 | 24 hours |

2.3.2. Diffusion Assay Through Hydrogel Films

Side-by-side Franz cells (PermeGear, Hellertown PA, USA) were used to study ZAN diffusion kinetics across the swollen hydrogel film, as previously described [22]. Initially, hydrogel films were pre-swollen in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 24 hours. The thickness of the hydrogel films before and after swelling is described in Table 2. Next, the swollen films were meticulously trimmed into 9 mm2 circles which were then clamped in between the receiver and donor chambers. The receiver compartment was filled with PBS and then 3 mL of ZAN solution (1 mg/mL) was added into the donor compartments. At pre-determined time intervals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 24 hours), the receiver solution was sampled and replenished with fresh PBS. The aliquots sampled were then analyzed via high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described in Section 2.7.5.

Table 2.

The thickness of hydrogel films before and after swelling.

| Hydrogel system | Thickness (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Before swelling | After swelling | |

|

Gantrez® S-97-PEG

10,000 |

0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

| PVP-PVA citric acid | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 1.03 ± 0.02 |

|

Gantrez® S-97-PEG

10,000-sorbitol |

0.88 ± 0.06 | 1.13 ± 0.06 |

2.4. Preparation of the Microneedle Array

The MAs were prepared from a hydrogel formulation consisting of a solution of 20–30 wt% of Gantrez™ S–97 BF polymer and 7.5 wt% of polyethylene glycol (PEG, MW = 10,000). The Gantrez-PEG solution was added on top of laser-ablated silicon MN templates (Blueacre Technology Ltd, Dundalk, Ireland), and positive pressure (60–70 psi) was applied to form the MA. The dimensions of these molds are 800 μm height; 350 μm base; 600 μm tip-tip, with a total of 256 needles and an overall needle area of 1 cm2. The polymer solution was then dried in the mold at room temperature or at 40 °C. After 48 hours, the MAs were removed from the molds, trimmed, and thermally cross-linked at 80 °C for 24 hours. The baseplates of the MAs were measured with digital calipers at two opposing corners of the array. MAs with a baseplate of 500μm ± 100μm and missing no more than 3 needles were accepted for further testing. The final MAs were packaged with a desiccant to prevent premature hydration.

2.5. Testing of the Microneedle Array

2.5.1. Evaluating the Penetration Depth of the MA

To evaluate the penetration depth, MAs (n=3) were attached to the bottom of the probe of the Lloyd LRX Plus® (Ametek® Instruments, Largo, FL, USA) with double-sided foam tape and inserted into six layers of Parafilm®M film at a rate of 0.1 mm/s until a force of 32 N was reached, where it was held for 30 seconds. Penetration was measured by depth, with each layer of Parafilm® measuring ≈160 μm. The holes were manually counted on each layer of Parafilm® and shown as a percentage of piercing. The penetration depth of MA into the Parafilm® and ex vivo porcine skin was visualized via optical coherence tomography (OCT) (EX1301 OCT Microscope Michelson Diagnostics Ltd., Kent, UK). The swept-source Fourier domain OCT system has a laser center wavelength of 1305.0 ± 15.0 nm, facilitating real-time high-resolution imaging (7.5 μm lateral and 10.0 μm vertical resolution). The Parafilm® and skin was scanned at a frame rate of up to 15 B-scans (2D cross-sectional scans) per second (scan width = 2.0 mm). The 2D images will be analyzed using the imaging software ImageJ® (National Institute of Health, USA). The scale of the image files will be obtained using 1.0 pixel = 4.2 μm.

2.5.1. Evaluating the Swelling Capacity of the MA

To evaluate the swelling capacity of hydrogel-forming MA, cross-linked MAs were added to 30 mL of PBS in 100 mm × 20 mm Cellstar® Cell Culture dishes, oscillated on a Mini BlotRocker 3D® (Benchmark Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA), and weighed at 0. 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 24 hours.

2.6. Preparation of CarraDres™, Glass, and Alginate ZAN Reservoirs

To prepare the ZAN-containing reservoirs, the ZAN Hyd starting material was first suspended in water containing 1% benzyl alcohol, to inhibit microbial growth, at concentrations of 150 mg/mL or 375 mg/mL. The solutions were then acidified using concentrated HCl, which improves the solubility of ZAN by converting it to its HCl salt in situ, resulting in a 1:1 molar ratio of ZAN:HCl. To prepare the 150 mg CarraDres™ ZAN reservoir, 1mL of the 150 mg/mL ZAN HCl solution was loaded on 1 cm2 disks of CarraDres™, a commercially available topical wound dressing. For the 150 mg ZAN glass reservoir, the 375 mg/mL ZAN HCl solution was added to foil liners in 400 μL aliquots and evaporated to dryness for 24 hours at ambient conditions. Lastly, 50 mg ZAN alginate reservoirs were prepared from a solution of ZAN HCl (150 mg/ml) containing 2% sodium alginate that was added to circular wells in 33 uL aliquots and evaporated to dryness for 24 hours at ambient conditions.

2.7. Preparation and Characterization of Lyophilized ZAN Reservoirs

2.7.1. Preparation of LYO Wafers

LYO wafers were fabricated by mixing ZAN (Hyd or HCl) with a combination of gelatin, trehalose, and deionized water, based on previously reported methods [22]. ZAN Hyd and HCl solution was prepared as described in Section 2.6. LYO-1 reservoirs contained 10 mg ZAN (Hyd or HCl), 2 mg gelatin, 5 mg trehalose, and 83 mg deionized water. LYO-2 reservoirs contained 50 mg ZAN (Hyd or HCl), 2 mg gelatin, 5 mg trehalose, and 43 mg deionized water. Once mixed, 100 mg of the mixture was transferred into a plastic mold (diameter 8 mm, depth 4 mm). The mixture was then frozen at −20 °C and lyophilized (Virtis™ Advantage XL-70, SP Scientific, Warminster PA, USA) for 24 hours. The lyophilization cycle involves a primary drying phase of 13 hours at −40 °C and a secondary drying phase of 11 hours at 25 °C while under a vacuum at 50 mTorr throughout the cycle. In this work LYO-1 refers to reservoir with a low drug loading of 10 mg while LYO-2 refer to reservoir with a high drug loading of 50 mg.

2.7.2. Characterization of LYO Wafers for Dissolution and Drug Content

The time taken for the wafer to dissolve was studied by placing the wafer in a glass vial containing 25 mL of PBS while stirring at 600 rpm. The vial was thermoregulated at 37 °C. In addition, the resulting drug solution upon complete wafer dissolution was used to evaluate the ZAN content via HPLC analysis, see Section 2.7.5.

2.7.3. Characterization of LYO Wafers via Stereo Microscope

The solid-state of ZAN in the formulation was elucidated by a combination of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, TA Instruments, Surrey, UK) and X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD, Rigaku Corporation, Kent, England). The structure of the wafer formulations was examined via a stereo microscope.

2.7.4. Characterization of LYO Wafers via a Franz Cell Permeation Assay

The permeation of ZAN was conducted via a Franz cell assay (Permergear, Hellertown PA, USA). Dermatomed skin harvested from stillborn piglets was used in this experimental setup which was attached to the donor compartments of the cells. In addition, degassed and pre-warmed PBS buffer was used as the receiver solution. The temperature of the receiver solution was set to 37 ± 1 °C while being continuously stirred at 600 rpm. Hydrogel-forming MAs were inserted into the skin via manual pressure for 30 seconds. Afterward, a ZAN-loaded reservoir was added on top of the MA. The Franz cell assay was completed by meticulously securing the donor compartment with the receiver compartment using a metal clamp. Metal weights (15 g) were carefully placed above the system to prevent the MA from being dislodged from the skin during the study. At predefined time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours), 200 μL of the receiver media was sampled and replenished with an equal volume of fresh PBS. The samples were analyzed via HPLC, see Section 2.7.5.

2.7.5. HPLC Analysis of Samples

HPLC (Agilent technologies 1220 infinity UK Ltd, Stockport, UK) analysis was used to quantify the amount of ZAN loaded and delivered. The system consisted of a degasser, binary pump, auto standard injector, along with a UV detector. Analyte separation and quantification was conducted using a Spherisorb® ODS1 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm internal diameter, 5 μm particle size) (Waters, Dublin, Ireland), perfused with mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min at 25 °C. The mobile phase consisted of HPLC grade water: acetonitrile at a 95:5 v/v ratio. A 20 μL injection volume was used, while analyte detection was conducted at λ=210 nm. The analytical method was validated based on the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) standard [28].

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism® version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Data are shown as either means ± standard deviation (SD) or means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences were evaluated using either Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with statistical significance deemed at p < 0.05.

2.8. Evaluation of Zero-Order ZAN Delivery in the Hollow-Fiber-Infection Model (HFIM):

The HFIM system was used to evaluate the efficacy of zanamivir against the oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus, A/Hong Kong (H275Y). The use of the HFIM system for influenza A viruses has been described previously [29–31]. Briefly, MDCK cells (ATCC CCL-34, Manassas, VA) were mixed with oseltamivir-resistant A/HongKong/2369/2009 (A/HK-H275Y) (H1N1 pdm) virus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10−6 and inoculated into hollow fiber (HF) cartridges (n=2) (FiberCell Systems, Inc., Fredrick, MD). Medium containing various concentrations of ZAN Hyd, which simulated plasma profiles seen with the highest total daily IV dose (1,200 mg) 2,800 ng/mL, and serial dilutions to 2,000 ng/mL, 1,000 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, and 10 ng/mL, were circulated through the HF cartridges in a continuous loop and media was sampled daily. Viral supernatants were clarified via centrifugation and frozen at −80 °C prior to quantification by plaque assay on MDCK cells [32].

2.9. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Characterization of ZAN via Subcutaneous Delivery in Mice

2.9.1. Preclinical PK Proof-of-Concept in Mice

ZAN efficacy has not been shown with transdermal administration, therefore it was crucial to elucidate the potential of ZAN administration via this route. MAPs could not be reproducibly applied to mice, due to their small size. Given that MAPs deliver ZAN intradermally, and intradermal administration is too cumbersome in studies with large numbers of animals, we conducted a PK study in mice with subcutaneous (SC) administration to assess if SC administration was an adequate alternative route for the influenza efficacy studies in mice. Male CFW mice (n=4) were dosed with 30 mg/kg of ZAN HCl. Plasma and lung samples were obtained at 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 hours post-dose and were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, see Sections 2.9.2 and 2.9.3.

2.9.2. LC-MS/MS Method for ZAN Quantification in Plasma Samples

Plasma standards, QCs, and study samples (300 μL) were diluted with 300 μL of ZAN Internal Standard solution (500 ng/mL in 4% phosphoric acid in water) and then processed by solid phase extraction using Waters Oasis MCX 1 cc (30 mg) LP Extraction Cartridges. The samples were then analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Shimadzu 8050 mass spec, Shimadzu Nexera X2 HPLC) after elution from a Kinetex C8 column with a 0.1% Formic acid in water: acetonitrile gradient. ZAN and the ZAN-13C, 15N2 internal standard were each monitored at two transitions ((333.2→60.2; 333.2→121.05) and (336.2→63.2; 336.2→121.05), respectively). The method was suitable for measuring ZAN in mouse plasma over a concentration range of 10 to 5,000 ng/mL with a %RE ≤ 15% and %CV ≤ 15%.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the concentration-time profiles using the WinNonLin Non-compartmental Analysis program, version 8.1.0.3530.

2.9.3. LC-MS/MS Method for ZAN Quantification in Mouse Lung Tissue

Lung tissue (150 mg) was combined with water (300 μL) containing ZAN internal standard solution at 333 ng/mL, and homogenized using a Bullet Blender set at speed 10 for 4 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged and 250 μL supernatant was combined with 350 μL of 4% phosphoric acid and then processed and analyzed as described in Section 2.9.2. This method was suitable for measuring ZAN in lung tissue over a concentration range of 10 to 2,000 ng/mL with a revised accuracy criteria of %RE ≤ 20%.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the concentration-time profiles using the WinNonLin Non-compartmental Analysis program, version 8.1.0.3530.

2.9.4. Proof-of-Concept Preclinical Efficacy in Mice

In the dose-range study, female BALB/c mice (n=10) were assigned to seven cohorts. Mice were treated with either placebo (SC), 37.5 mg/kg ribavirin (oral), 50 mg/kg oseltamivir (oral), 1.5 mg/kg ZAN (SC), 5 mg/kg ZAN (SC), 15 mg/kg ZAN (SC), or 50 mg/kg ZAN (SC). Four hours later these mice were inoculated intranasally with a lethal dose (4,500 CCID50) of pandemic influenza A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 (H1N1) oseltamivir-resistant virus. Then the mice were treated twice a day (BID) with the corresponding therapeutic for five days. Animals were observed for weight loss and mortality for 21 days.

We subsequently conducted a dose-regimen study as described above, however, modified the doses to 1) placebo, 2) 100 mg/kg/day ZAN (SC) dosed on the first day only, 3) 100 mg/kg/day ZAN (SC) BID for 5 days, 4) 100 mg/kg/day ZAN (SC) once a day (QD) for 5 days, and 5) 100 mg/kg/day ZAN (SC) every other day or 6) 100 mg/kg/day ZAN (SC) every third day, including 7) oseltamivir at 100 mg/kg/day (oral) and 8) ribavirin at 75 mg/kg/day (oral) BID as the negative and positive control, respectively. Animals were then observed for weight loss and mortality for 21 days.

2.10. PK Characterization of ZAN via Transdermal Delivery in Rats and Minipigs

2.10.1. In Vivo PK Study with MA Delivery of ZAN to Rats

The MA with a ZAN reservoir was applied topically to Sprague Dawley rats (n=4). Both Carradres™ and various dry reservoirs were evaluated. The treatment site (lateral anterior dorsal surface) was shaved and treated with depilatory cream 24 hours prior to application and cleaned with 70% ethanol just before application. Foam rings were adhered to the skin using VetBond adhesive to prevent dislocation throughout the experiment. The MAs were applied to the cleaned area within the foam ring and held in place for 30 seconds. The ZAN-loaded reservoir was placed on top of the MA and covered with a drug-impermeable backing membrane (Scotchpak™ #1109 SPAK 1.34 MIL Heat Sealable Polyester Film) which was held in place via the adhesive on the foam ring. The animals were then wrapped in kinesiology tape to hold everything in place. At the end of 72 hours, the MAPs were removed, and no visible signs of irritation were noted. Blood samples were collected at 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-dose.

Epithelial lining fluid (ELF) samples were collected via Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). A small incision was made into the trachea and 5 mL of water was flushed into the lungs. Then, the water was withdrawn back into the syringe and collected. ELF samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4 (separate cohorts), and 72 hours post-dose. All ELF samples were frozen at −80° C within 1 hour of collection. Plasma and ELF samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, see Sections 2.9.3 and 2.9.4.

2.10.2. In Vivo PK Study with MN Delivery of ZAN in Minipigs

A 3-day (Group 1 and 2) and 5-day study (Group 3) in Gottingen Minipigs (n=2–3/cohort) with plasma and BAL sampling was conducted at Charles River Laboratories using the same techniques as the rat studies. Animals were fasted overnight and then were administered Telazol for sedation during the dosing and removal procedures, with a single intramuscular injection of a dose level of 1–6 mg/kg. Isoflurane was administered to effect by inhalation to animals undergoing BAL.

During the 3-day study, both Carradres™ and the glass reservoir were evaluated. The hair was clipped from the ventral surface the day prior to dosing. On the day of dosing, the exposure site was cleaned with 70% isopropyl alcohol just before application. A foam support was adhered around the treatment area with tissue adhesive (Vetbond or similar). The MA was secured to the skin within the area of the foam support (4 MAs/ animal in the treatment site). Each MA was pressed firmly against the skin for 30 seconds. For Group 1, the Carradres™ reservoir (~150 mg) was applied to each array. For Group 2, 20 μL of water and the film reservoir (~150 mg) were applied to each MA, and a foam insert was applied to cover the MAs. The exposure site and foam support were covered with ScotchPak™ and Tegaderm™ (3M™). Kinesiology tape was used to further secure the array and a JET undershirt jacket was placed on the animals. Plasma samples were collected at 0.5, 2, 8, 24, and 72 hours post-application.

MAs with Carradres™ reservoirs were tested in the 5-day study (Group 3) and applied as described above. Dosing occurred while the animals were sedated for pre-dose BAL collections. For the BAL collection, animals were anesthetized and intubated for sample collection. The animals were placed into a recumbent position and the appropriately sized bronchoscope was passed through the endotracheal tube using a double swivel connector into an appropriate airway. A maximum of 4 mL/kg was used to lavage the selected lobar bronchus with warmed saline and the BAL sample was collected from a different lobe for each time point. After the saline wash, gentle suction was applied to collect the sample for analysis. The BAL samples were collected pre-dose, and at approximately 0.5, 2, 8, 24, and 72 hours post-dose. After the 2, 8, 24, and 72 hour collections, the animals were allowed to recover normally and were returned to their cages. Blood samples were collected pre-dose, and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours post-dose. Plasma and BAL samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, see Sections 2.9.3 and 2.9.4.

2.10.3. LC-MS/MS Method for ZAN Quantification in Plasma Samples

The method described in Section 2.8.2 was qualified for rat and minipig plasma. The method was suitable for measuring ZAN in rat plasma over a concentration range of 10 to 5,000 ng/mL and in pig plasma over a concentration range of 50 to 50,000 ng/ml with a %RE ≤ 15% and %CV ≤ 15%.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the concentration-time profiles using the WinNonLin Non-compartmental Analysis program, version 8.1.0.3530.

2.10.4. Quantification of ZAN in Epithelial Lining Fluid (ELF)

BAL samples collected from both rats and pigs were filtered using a 0.2-micron filter and analyzed using the LC-MS/MS method described in Section 2.9.3 over a concentration range of 1.5 to 1,500 ng/ml with a %RE ≤ 20% and %CV ≤ 20%.

The BAL samples filtered for ZAN quantification were also analyzed for urea concentration. Filtered BAL samples were further diluted 10-fold with water prior to analysis. Standards, QCs, and samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Shimadzu 8050 mass spec, Shimadzu Nexera X2 HPLC) after elution from a Kinetex C18 column with an isocratic 90:10 ratio of 0.1% Formic acid in water: 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile. Urea was monitored at two transitions (61.1→41.1; 61.1→18.2). The method was suitable for measuring urea in BAL over a concentration range of 10 to 10,000 ng/mL in both rat and pig BAL with a %RE ≤ 20% and %CV ≤ 20%. Serum samples were also collected from both rats and pigs and analyzed for urea concentration via standard clinical pathology assays at the University of Michigan (rats) and Charles River Laboratories (pigs). The ZAN concentration in ELF was determined with the following equation: CELF=CBAL × (Ureaserum/UreaBAL).

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the concentration-time profiles using the WinNonLin Non-compartmental Analysis program, version 8.1.0.3530.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solute Diffusion Study

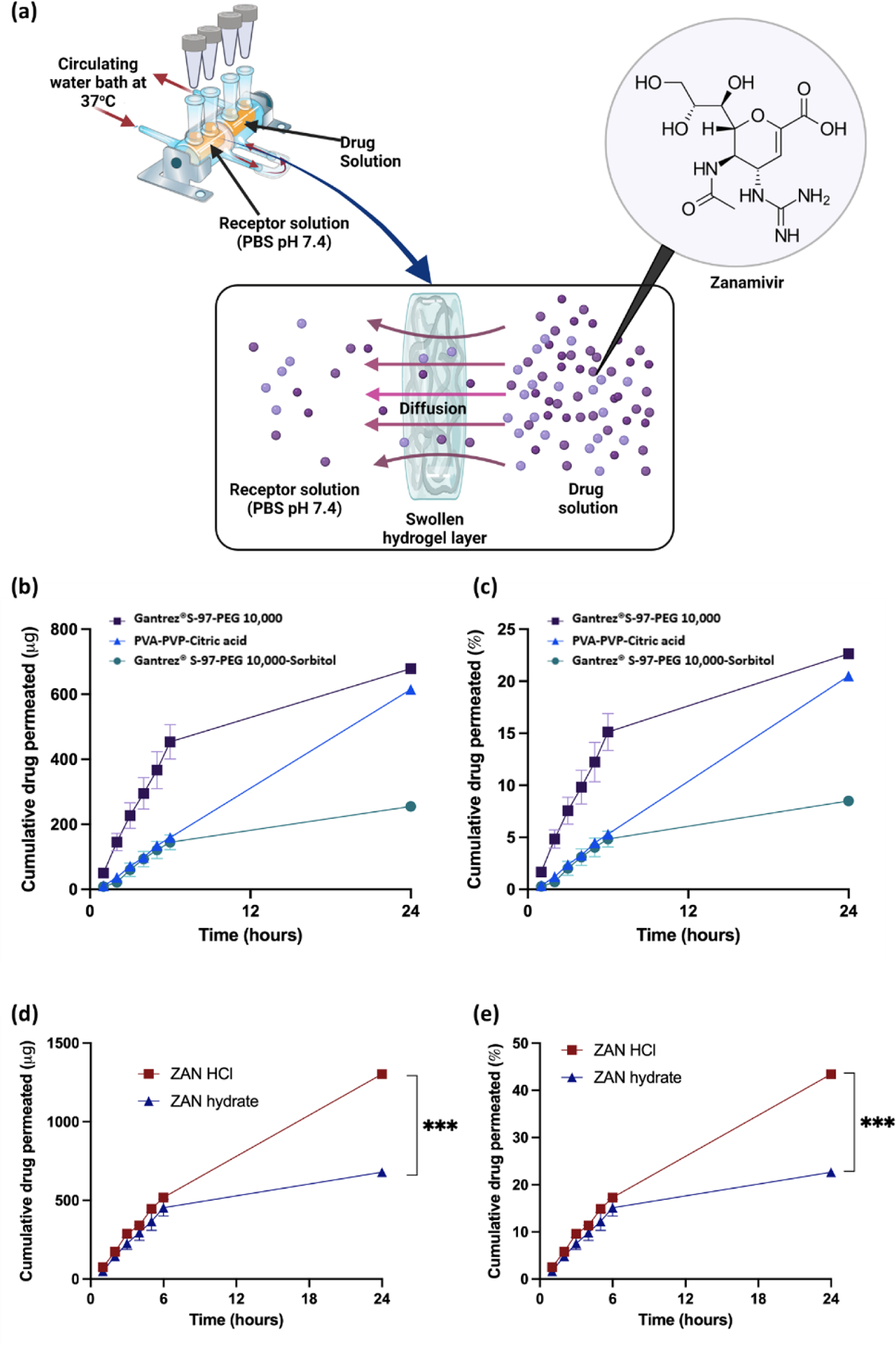

The diffusion kinetics of ZAN across the different hydrogel systems was evaluated via a solute diffusion study utilizing side-by-side diffusion cells. The experiment was performed as shown in Figure 1a. Based on the results from Figures 1b and 1c, the hydrogel formulation prepared from Gantrez® S97-PEG 10,000 showed the highest permeation of ZAN relative to other hydrogel films evaluated.

Figure 1.

(a) Graphic displaying the setup for the solute diffusion study used to investigate diffusion kinetics of ZAN through different hydrogel systems. (b) The cumulative amount (μg) and (c) the cumulative percentage of ZAN Hyd diffused across different hydrogel systems over 24 hours. (d) The cumulative amount (μg) and (e) the cumulative percentage of ZAN permeated using an HCl or Hyd across the Gantrez® S-97-PEG 10,000 system over 24 hours. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n = 3.

Using the Gantrez® S97-PEG 10,000 hydrogel, we achieved over ≈ 20% permeation of ZAN Hyd (≈ 0.6 mg) across the swollen film. This enhanced diffusion kinetics may be ascribed to a combination of the overall swelling property as well as the ability of the hydrogel system to retain water once a fully swollen equilibrium state has been achieved. Based on our previous work, we observed that hydrogel systems fabricated from Gantrez® S97-PEG 10,000 resulted in higher swelling at 24 hours relative to a PVP/PVA-based hydrogel [22]. In addition, the introduction of an osmolyte such as sorbitol into the Gantrez® based system blend, prior to crosslinking, typically resulted in a lower degree of hydrogel swelling [27,33]. Indeed, the diffusion of ZAN across a swollen hydrogel network will mainly take place within aqueous conduits, between the cross-linked polymer chains, due to the high aqueous solubility of the drug. Therefore, hydrogels that can achieve higher degrees of swelling, such as Gantrez® S97-PEG 10,000, would retain more water at equilibrium thereby generating more aqueous pathways for the hydrophilic drug to diffuse into and across the film as seen in Figure 1.

In addition to exploring different hydrogel systems, we also determined if the type of ZAN counterions impacts the degree of drug diffusion across the swollen hydrogel networks. The utilization of inorganic counterions is sometimes employed in formulation design as a strategy to improve a drug’s solubility, dissolution rate, and even stability [34]. Based on Figures 1d and 1e, we discovered that when ZAN was prepared as an HCl solution, permeability was significantly (p<0.05) increased over 24 hours compared to the Hyd form of the drug, across Gantrez® S97-PEG 10,000. This difference in diffusion kinetics was attributed to the increased solubility of the ZAN HCl.

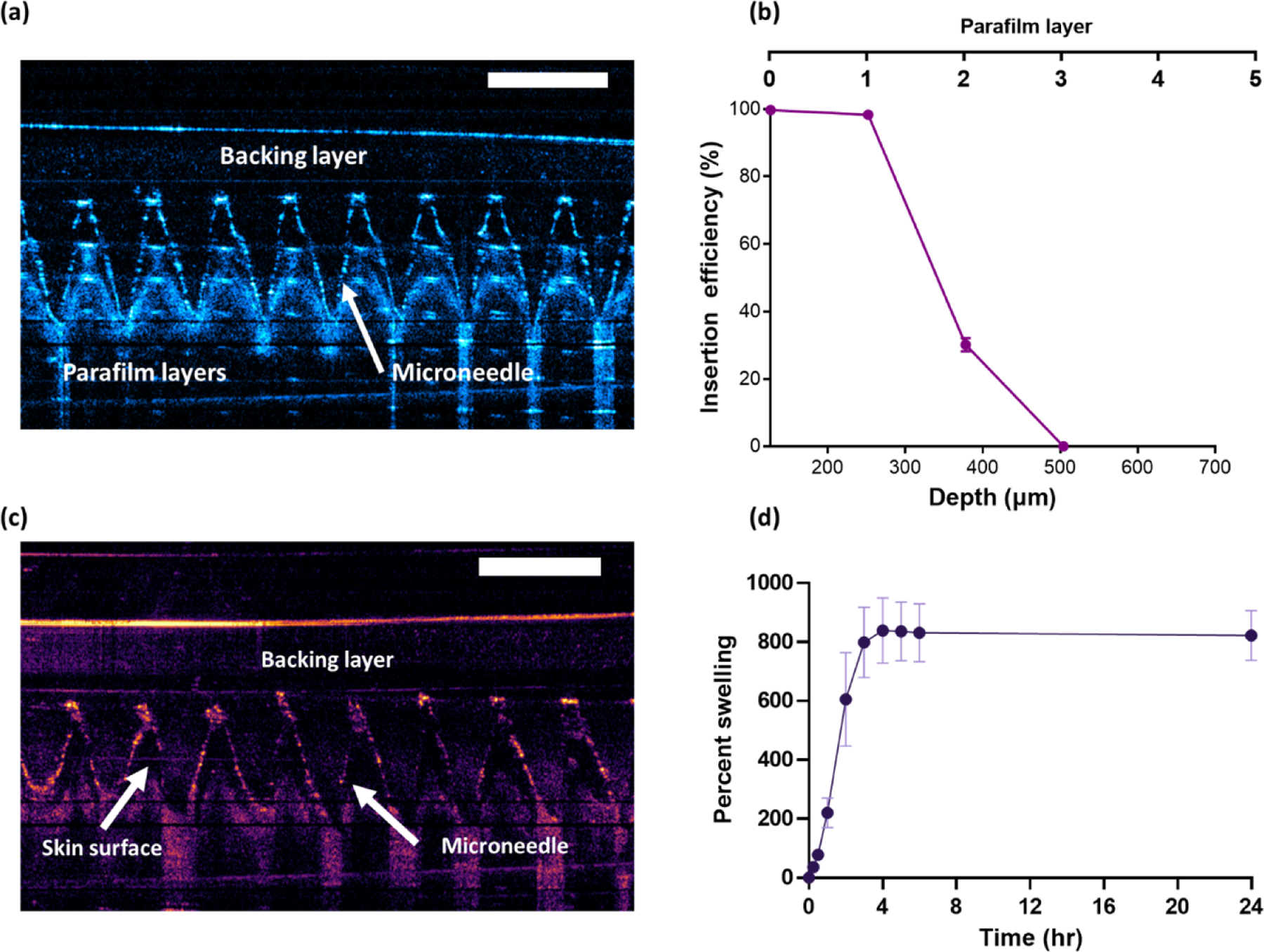

3.2. Characterization of the Microneedle Array

The MA is made from a well-characterized hydrogel system consisting of Gantrez S-97 and PEG 10,000 [35]. The MAs were assessed for their physical strength by determining their ability to reproducibly penetrate multiple layers of Parafilm®M as shown in Figure 2a and Figure 2b. The penetration of the MA across the Parafilm®M stack, which serves to mimic human skin, was investigated using OCT. The patch was subjected to an applied force of 32 N force which simulates the typical pressure applied by the thumb when pressing an elevator button. As shown in Figure 2b, the hydrogel-forming MA exhibited complete insertion into the first Parafilm®M layer in a reproducible fashion due to the absence of any error bars. In addition, the average penetration depth was measured at 450 μm, with a high degree of reproducibility (CV<15%). This would suggest that the hydrogel-forming MA could puncture through the stratum corneum (10–30 μm thick), consistently [36]. This would enable the reproducible implantation of hydrogel-forming needles into the dermis, forming conduits to channel the delivery of ZAN into the skin, thereby reaching the systemic circulation.

Figure 2.

(a) Example of OCT scans demonstrating the penetration of MA into Parafilm®M layers which mimics human skin. (b) % of channels generated with increasing Parafilm®M depth (means ± SD, n = 3). (c) OCT scan showing intradermal insertion of MA into ex vivo full-thickness porcine skin. (d) Swelling kinetics in PBS for MA manufactured from Gantrez™ S-97 and PEG 10,000 (means ± SD, n = 3).

The needles from the fabricated MAs are sharp enough to pierce the skin as shown in Figure 2c, but once hydrated through exposure to dermal interstitial fluid, the polymer swells, generating a continuous hydrogel network. Upon swelling, this type of hydrogel-forming MA is no longer considered sharp. This provides a protective mechanism to prevent accidental needle reinsertion thus reducing the risk of bloodborne infection. Furthermore, our prior work has demonstrated that repeated applications of the hydrogel-forming MAs to human patients did not result in a prolonged skin reaction. Additionally, the loss of the skin’s barrier function was only transient [35].

The swelling kinetics of the MA (% water uptake over time) is shown in Figure 2d. After 2 hours, the MA weight doubled and reached a maximum swelling capacity of approximately 800% within 4 hours. This is not reflective of the swelling that would occur in the skin due to the limited dermal interstitial fluid, however, the degree of swelling that would take place upon skin application still results in the formation of continuous aqueous hydrogel conduits to deliver drug molecules from the dry reservoir across the skin.

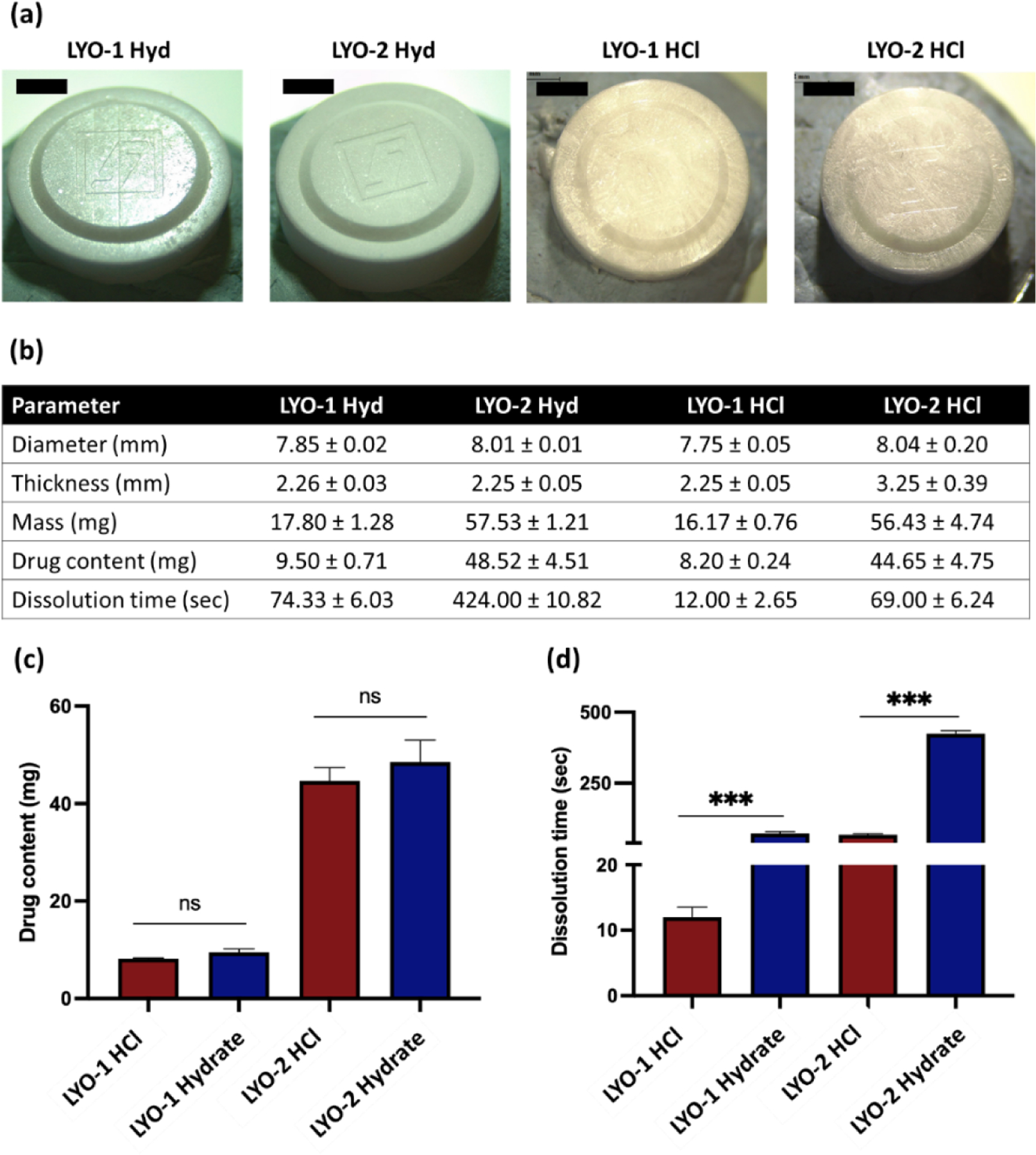

3.3. Lyophilized Reservoir Characterization

Figure 3a shows the microscopic images of the wafers developed. All reservoirs developed were homogenous and robust. The lyophilized wafer had a diameter of ≈ 7.8–8.0 mm while displaying an overall thickness of approximately ≈ 2–3 mm as shown in Figure 3b. The amount of ZAN loaded, along with the time taken for the reservoir to dissolve, was also investigated to determine potential impact on diffusion, permeability, and plasma concentrations. As demonstrated in Figure 3c, LYO-2 reservoirs contained a higher drug content (mg) than LYO-1. The data presented in Figure 3d confirmed that LYO fabricated from ZAN HCl displayed a significantly faster (p<0.05) dissolution time relative to ZAN Hyd. All lyophilized reservoir systems were fabricated using the same concentration of gelatin and trehalose. Gelatin was added as a collapse temperature modifier to reduce the primary drying cycle without compromising the product quality. In addition, trehalose was added as a cryoprotectant to provide stability to the drug molecule during the lyophilization process [37]. Therefore, the rapid dissolution time for the LYO-HCl wafer relative to LYO-Hyd is a result of the higher aqueous solubility of ZAN HCl in comparison to ZAN Hyd. In addition, an overall increased drug content resulted in a prolonged dissolution time (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

(a) Digital microscope images for ZAN LYO wafer formulations. (b) Characteristics of LYO wafers of respective ZAN LYO wafer formulation, including diameter, thickness, mass, drug content, and dissolution time. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n=3. (c) Drug content for LYO wafer containing either ZAN HCl or ZAN Hyd indicating no significant differences (n.s) in drug loading for respective salts. (d) Dissolution time for LYO wafers containing either ZAN HCl or ZAN Hyd indicates a decrease in dissolution time by changing ZAN from Hyd to HCl salt. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n=3.

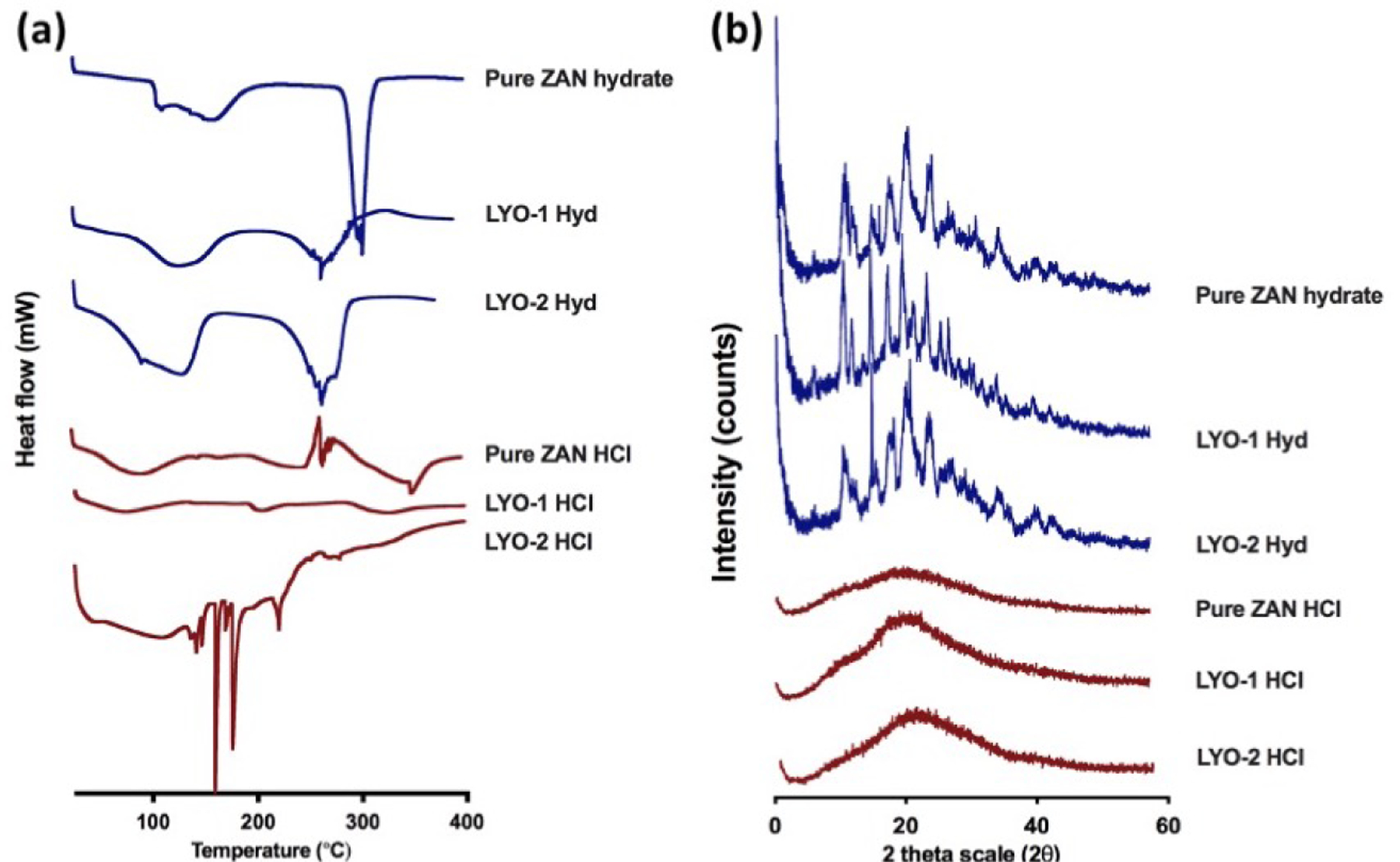

The DSC profiles of ZAN formulations along with the pure drug are shown in Figure 4a, while the XRD diffractogram of ZAN and respective formulations are displayed in Figure 4b. The thermogram for pure ZAN Hyd exhibited a sharp endothermic peak temperature of 290 °C which signified melting along with drug degradation. In contrast, ZAN HCl showed an endotherm at 250 °C which reflects drug melting and degradation. The ZAN Hyd was crystalline as shown by XRD analysis. In contrast, the ZAN HCl was mainly amorphous as shown in Figure 4b. However, when the drug was formulated into lyophilized wafers, we did not observe sharp diffractogram peaks which suggests that lyophilization does not promote any drug recrystallization within the reservoir.

Figure 4.

(a) Differential scanning calorimetry and (b) X-ray powder diffraction analysis of pure ZAN Hyd, pure ZAN HCl, and drug-loaded reservoirs.

3.4. In Vitro Permeation Study

Following the dry reservoir and MA characterization, a Franz cell permeation study across dermatomed neonatal porcine skin was conducted as illustrated in Figure 5a. As shown in Figure 5b, LYO wafers manufactured from ZAN HCl resulted in greater ZAN permeation (p<0.05) compared to ZAN Hyd. The LYO-1 HCl resulted in an overall more rapid and greater ZAN delivery (p<0.05) across the skin within the first 8 hours compared to all other reservoirs (Figure 5c). However, the LYO-2 HCl formulation resulted in a greater delivery (mg) of ZAN over 24 hours (Figure 5b). Although, there was a slight decrease in the drug permeation from 6 to 8 hours, this is within the variation range of the assay.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic illustrating the setup for in vitro skin permeation study for ZAN across dermatomed neonatal porcine skin. (b) Permeation kinetic of ZAN Hyd and ZAN HCl over 24 hours from LYO wafers across the hydrogel-forming MA (data presented as means ± SD, n=3). (c) ZAN delivered across dermatomed skin over 24 hours (data presented as means + SD, n=3). (d-e) ZAN extracted from each component of Franz cells over 24 hours (data presented as means ± SD, n=3). ANOVA one-way test was used as the statistic test.

Based on the results in Figures 5d and 5e, the ZAN HCl reservoirs resulted in both greater absolute cumulative drug permeation and delivery efficiency, as reflected by the depleted remaining reservoirs, relative to the ZAN Hyd reservoirs. This suggests that changing to the salt form of ZAN improved the delivery efficiency, likely mediated by its increased solubility and faster dissolution. Similarly, relative delivery efficiency was significantly reduced with the higher drug load in the ZAN Hyd reservoir, and only slightly with the ZAN HCl, again likely driven by the differences in solubility and dissolution rate of the two reservoir formulations. The drug was retained within the hydrogel network of the MA at 24 hours, as previously reported [22,27]. With a long-term application (i.e. over 5 days), the amount of ZAN entrapped within the hydrogel would continue to diffuse into the skin over time.

3.5. Zero-Order ZAN delivery in the Hollow-Fiber-Infection Model (HFIM)

The HFIM is an elegant way to simulate human plasma profiles and relate those to efficacy outcomes such as influenza virus suppression. Results from a dose range-finding study with steady-state concentrations, simulating zero-order ZAN input, demonstrated that at plasma levels as low as 10 ng/mL ZAN reduced viral replication for up to 48 hours (Figure 6). The maximum viral suppression was achieved with a continuous infusion of 1000 ng/mL, which was similar to the effect observed at 2800 ng/mL. This concentration is equivalent to the 24-hour AUC associated with a 600 mg BID ZAN intravenous administration in humans [30]. Viral suppression at 100 ng/mL was similar to that achieved at 1000 ng/mL, therefore our target range for ZAN MAP delivery in humans was 200–300 ng/mL over the 5-day treatment course.

Figure 6.

Viral burden vs time in the HFIM assay. The black dotted line indicates the limit of detection. Data are reported as the mean ± SD, n=2.

3.6. PK of ZAN via Subcutaneous Delivery

The mouse model proved to be too small of an animal for the required MAP size of the application. Therefore, a PK study in CFW mice via SC administration was conducted to assess if ZAN levels in the lung remained above the target range over a long enough period that efficacy could be expected with BID SC dosing. After SC administration of ZAN at 30 mg/kg, plasma levels peaked at 15 min and fell below the detection limit by 24 hours, however, lung concentrations remained ~60-fold above the IC50 (~1.4 ng/mL) at 48 hours post-dose (Figure 7). The concentration-time profile of ZAN in plasma and lungs revealed a significantly prolonged half-life of ZAN in the lung (t1/2 = 30.0 hours).

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic representation showing the subcutaneous administration of zanamivir in mice. (b) Plasma and lung concentration-time profile of ZAN after SC administration to mice (mean ± SD, n=4). (c) Pharmacokinetic parameters of ZAN delivered following subcutaneous administration. Data presented as mean ± SD, n=4.

3.7. Proof-of-Concept Preclinical Efficacy

The feasibility of achieving efficacy with ZAN via SC administration in a lethal mouse model of influenza was then evaluated (Figure 8). Doses in Figure 8a were chosen based on the PK data in Figure 7. As expected, the majority of mice died in the placebo group, and all in the oseltamivir group (100 mg/kg/day), which was dosed at 1/3 of a previously reported efficacious dose [16,38,39]. Ribavirin (75 mg/kg/day), as the positive control, protected mice completely, and the 100 mg/kg/day dose of ZAN protected 9 out of 10 mice (Figure 8b). The surviving animals in the lower ZAN dose groups regained their weight upon recovery. This data is validated by the potency data against the A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 (H1N1pdm) strain which suggests that the IC50 of ZAN (0.36 μM) translates to 120 ng/ml [40]. With twice per day dosing at 15 mg/kg (i.e. 30 mg/kg/day), ZAN likely fell below this target concentration in the lung tissue between 4 and 8 hours post-dose.

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic illustrating the different treatment arms for the proof-of-concept efficacy study in a mouse model for oseltamivir-resistant influenza A/HongKong/2369/20009 (A/HK-H275Y) (H1N1 pdm). (b) Efficacy of ZAN SC, ribavirin PO, and oseltamivir PO against a pandemic, oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus, A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 (H1N1pdm), in a lethal mouse infection model. The dose reported is the total dose for the day. (c) Survival following treatment with ZAN SC, ribavirin PO, and oseltamivir PO against a pandemic, oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus, A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 (H1N1pdm), in a lethal mouse infection model. The dose reported is the total dose for the day. (***p<0.001, *p<0.05).

We then proceeded to perform a dose-regimen study at 100 mg/kg/day SC BID for 5 days, QD for 5 days, and every other day, every third day, or only on the first day, again including oseltamivir at 100 mg/kg/day and ribavirin at 75 mg/kg/day as the negative and positive control, respectively. Survival graphs are shown in Figure 8c. All surviving animals regained their weight upon recovery. Daily QD dosing showed the best protection, with 80% of the mice surviving. The protection progressively declined with less frequent dosing, and all animals died when only a single dose was given. Thus, paired with the efficacy driver being AUC above the IC50 for a ZAN MAP, these data strongly support our research hypothesis that a single dose administration of the ZAN MAP formulation that delivers ZAN continuously over the treatment course can lead to complete protection from influenza infection in humans.

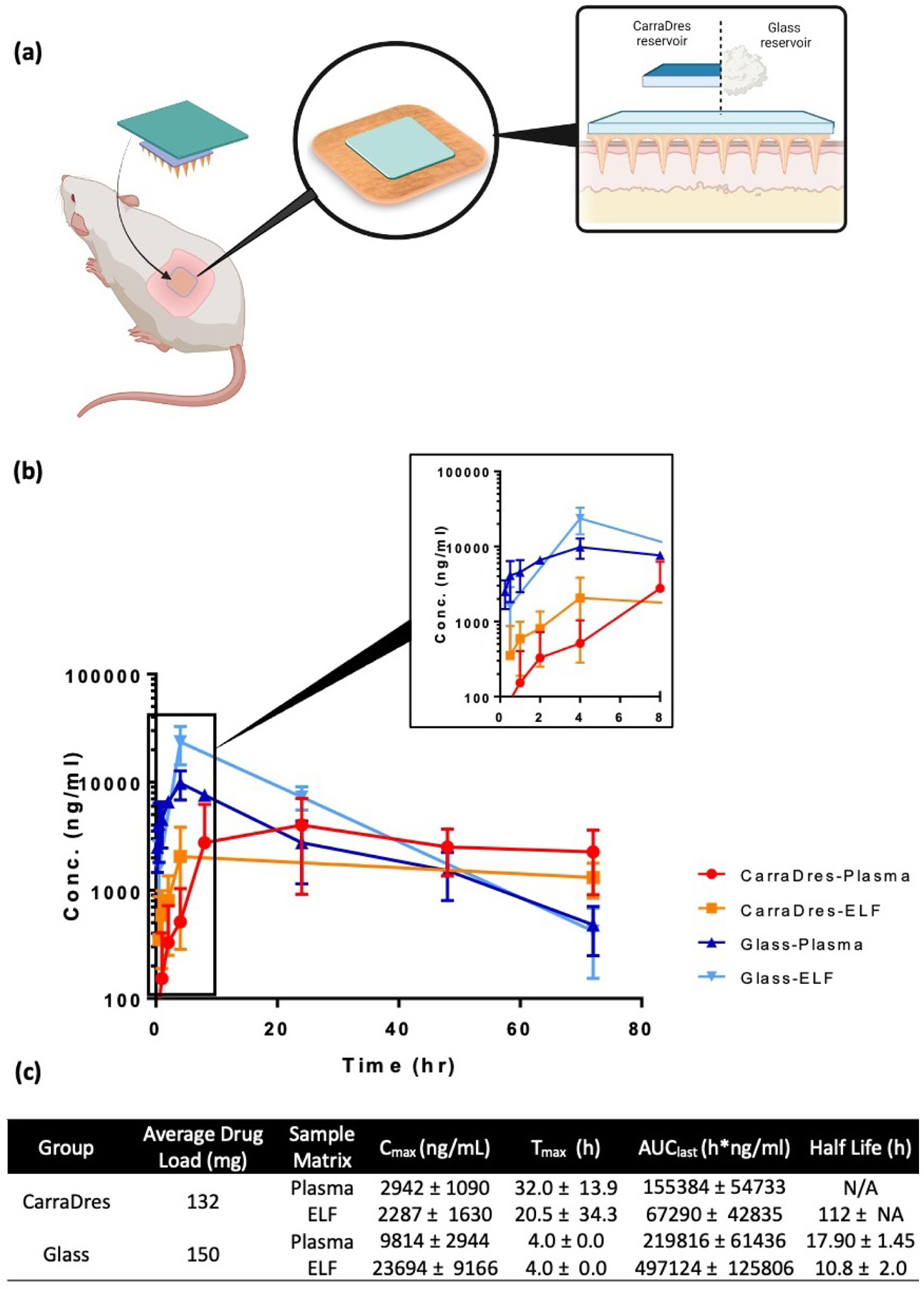

3.8. In Vivo PK Following MA Delivery of ZAN in Rats

The ZAN MA with a 150 mg reservoir loading dose was applied topically to rats (n=4) as shown in Figure 9a. Both Carradres™ and dry reservoirs were evaluated. Plasma concentrations exceeding ZAN IC50 levels for influenza virus isolates (>1.4 ng/mL) [41] were achieved with both the CarraDres™ as well as the dry ZAN HCl glass reservoir as early as 15 min post-administration (Figure 9b) and continued to increase until 24 hours post-administration. With the CarraDres™ reservoirs, steady-state was achieved 24 hours post-administration and maintained through 72 hours post-administration. MA-enabled delivery of ZAN resulted in ELF concentrations of 351 ng/ml at the 30-minute time point, well within our target range. By four hours, the ELF levels had increased to 2056 ng/ml, and steady-state levels were maintained through the 72-hour time point, in equilibrium with the plasma concentrations. We hypothesized that initial lung levels would likely exceed plasma levels since with transdermal application ZAN is distributed to the lung capillary system first and undergoes lung “clearance”. This is highly desirable for our product candidate because ZAN has an extracellular target in the lung.

Figure 9.

(a) Illustration showing the two treatment cohorts in the in vivo pharmacokinetic study in rats. (b) Plasma and lung concentration-time profile of ZAN after MA-reservoir administration to rat. (c) Pharmacokinetic parameters of ZAN delivered using either CarraDres or glass reservoirs with MA. Data expressed as mean ± SD, n=4.

The glass reservoir successfully delivered target plasma and ELF concentrations within 15 minutes of MAP application. The high initial concentration in both plasma and ELF slowly declined over the treatment course, while remaining above the target concentration through the last point evaluated, 72 hours. Unfortunately, the glass reservoir’s physical characteristics are less than ideal, such as being brittle and breaking easily when removed from the foil liners and under pressure. The glass reservoir was further optimized, which is crucial for the final product prototype. In Figure 10, evaluations of ZAN-loaded alginate thin films (50 mg) and LYO-1 Hyd wafers (9.5 mg) demonstrated successful delivery of ZAN well above the IC50 at 15 minutes post-MA administration and maintained steady-state levels through the 3-day study duration. Further, administration of the LYO-2 HCl MAP formulation (45 mg) achieved Cmax (4929 ng/ml) by 8 hours, with efficacious levels maintained through the end of the study. We demonstrated previously that efficacious ZAN levels in the lung via transdermal delivery with the MAP which was maintained over 72 hours. These results underscore the feasibility of developing a single-dose drug/device product that delivers ZAN continuously over 5 days.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic representation of the in vivo pharmacokinetic study in rats. (b) ZAN Plasma concentration-time profile after MA administered in rats with alginate thin film reservoirs and LYO wafers relative to the HFIM target range and IC50 (mean ± SD, n≥3). (c) Pharmacokinetic parameters of ZAN delivered using either alginate or lyophilized wafer reservoirs with MA. Data expressed as mean ± SD, n=4.

3.9. In Vivo PK Following MA Delivery of ZAN in Minipigs

A 3-day and 5-day study in Gottingen Minipigs (n=2) was performed to evaluate the PK of ZAN in plasma and ELF over the treatment course (Figure 11). During the 3-day study, four MAPs were applied to the ventral surface (sternum/rib area) (Figures 11a and 11b) of each pig for a total dose of 312 mg (CarraDres™ ) or 600 mg (glass) to confirm that adequate plasma levels were attained. Then the 5-day study with additional time points and collection of BAL samples was conducted to confirm delivery to the lung. The results from the 3-day study underscore the similar profiles for both the CarraDres™ as well as the glass reservoir formulation as seen in the rat, with plasma levels well above the IC50 at the earliest sampling time point of 30 min (Figure 11c). The glass reservoir demonstrated a faster onset of ZAN absorption, due to the high concentration gradient provided by the concentrated ZAN HCl formulation, However, the CarraDres™ formulations showed a continuous upwards trend of ZAN delivery, suggesting a higher likelihood that delivery could be sustained over five days. Based on these results, the CarraDres™ reservoir was chosen for the 5-day study.

Figure 11.

(a) Schematic representation showing the application of hydrogel-forming MA in combination with a dry drug reservoir near the sternum for in vivo pharmacokinetic study in minipigs. (b) Removal of the intact MA after 5 days of continuous delivery of ZAN to minipigs with no physiological changes to the site of application. (c) Plasma and lung concentration-time profile of ZAN after MA-reservoir administration to minipigs. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=2–3). (d) Pharmacokinetic parameters of ZAN delivered using either CarraDres™ or Glass reservoir with MA. Data expressed as mean ± SD, n=2–3.

During the 5-day study, plasma was sampled more frequently, and BAL was obtained at six-time points. During BAL sampling the pigs were anesthetized which caused a reduction in blood flow, which is likely the reason for the decline in plasma and ELF levels seen after the initial peak at 1–2 hours (Figure 11c). After 24 hours the levels recovered to the initial concentrations, and ZAN was delivered continuously through the end of the study (120 hours). The MAP was removed completely intact and the clinical observations showed no signs of skin irritation (Figure 11b).

We have demonstrated that our innovative drug-device MAP formulation with ZAN can deliver the drug across the skin and reach target steady-state exposure levels in plasma and ELF that are orders of magnitude above the IC50 and maintained over the entire treatment course of five days. Furthermore, initial studies with dry reservoir prototypes demonstrated an even more desirable concentration-time profile, with peak levels being reached rapidly after administration and maintained with a long half-life over multiple days. This represents an exciting new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of influenza, especially for patients with preexisting respiratory conditions, and for prophylaxis in a large number of high-risk patients.

4. Conclusion

ZAN is indicated for the treatment of acute, uncomplicated seasonal influenza. While the safety profile of this drug is excellent, oral inhalation limits its use in patients with underlying airway diseases, physical limitations, and in young children (2–7 years). This route of administration is also associated with significant pharmacokinetic variability. Positive safety and efficacy data from intravenous delivery of ZAN in hundreds of subjects have been published [18,19], and while this route of administration is approved in Europe, it is only available through compassionate use programs in the United States. Herein, we have developed a drug-delivery device combination product, consisting of a drug-free MA, combined with a ZAN-loaded reservoir.

We have conducted a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments to characterize the transdermal delivery of ZAN using this technology and anticipate this product to be ultimately marketed as a one-time administered MAP that delivers ZAN for up to five days. The hydrogel MAP product proposed here is positioned to replace the approved Relenza® diskhaler, and offers the promise of easier administration to a broader patient population, and better patient compliance. The new route of administration is expected to render a PK profile for ZAN that has greater inter-subject consistency than the inhaled route while providing total exposure levels that fall between the inhaled and intravenous routes. Perhaps most importantly, we have demonstrated that with MAP delivery, ZAN concentrations in the target compartment, the lung, are orders of magnitude higher than the time above the half-maximal inhibitory concentration for influenza virus replication (IC50) as early as 30 min after administration of the patch. The use of a MAP as a potential delivery approach to deliver antiviral drugs, such as those used to treat seasonal influenza, may offer potentially viable solutions to address a number of unmet medical needs as well as offer an attractive market entry strategy. Once this first drug/device combination product receives approval, the established manufacturing processes, in particular of the drug-free MA platform, will enable expansion into other drug products for therapeutics and vaccines that stand to benefit from the MAP delivery approach.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH Phase I and Phase II SBIR grants R43AI129122 and R44AI129122, and the in vivo efficacy work was conducted under NIH/DMID contract #HHSN272201700041I/HHSN27200003.

Abbreviations:

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BID

twice a day

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- ELF

epithelial lining fluids

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- HFIM

hollow fiber infection model

- Hyd

hydrate

- LYO

lyophilized

- MA

microneedle array

- MAP

microarray patch

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- QD

once a day

- SC

subcutaneous

- ZAN

zanamivir

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dawn Reyna: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Project administration, Validation

Ian Bejster: Methodology, Investigation

Aaron Chadderdon: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization

Cheryl Harteg: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation

Qonita Kurnia Anjani: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization

Akmal Hidayat Bin Sabri: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft

Ashley N. Brown: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Visualization

George L. Drusano: Software, Investigation

Jonna Westover: Methodology, Investigation, Visualization

E. Bart Tarbet: Methodology, Investigation

Lalitkumar K. Vora: Methodology, Investigation

Ryan F. Donnelly: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition

Elke Lipka: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Ryan Donnelly has patent licensed to TSRL, Inc.

References

- [1].Paules C, Subbarao K, Influenza, Lancet 390 (2017) 697–708. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].WHO, Influenza (Seasonal), Fact Sheets (2023). https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed May 24, 2022).

- [3].Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, Wu P, Kyncl J, Ang LW, Park M, Redlberger-Fritz M, Yu H, Espenhain L, Krishnan A, Emukule G, van Asten L, Pereira da Silva S, Aungkulanon S, Buchholz U, Widdowson MA, Bresee JS, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Cheng PY, Dawood F, Foppa I, Olsen S, Haber M, Jeffers C, MacIntyre CR, Newall AT, Wood JG, Kundi M, Popow-Kraupp T, Ahmed M, Rahman M, Marinho F, Sotomayor Proschle CV, Vergara Mallegas N, Luzhao F, Sa L, Barbosa-Ramírez J, Sanchez DM, Gomez LA, Vargas XB, Acosta Herrera a. B., Llanés MJ, Fischer TK, Krause TG, Mølbak K, Nielsen J, Trebbien R, Bruno A, Ojeda J, Ramos H, an der Heiden M, del L Signor Carmen Castillo, Serrano CE, Bhardwaj R, Chadha M, Narayan V, Kosen S, Bromberg M, Glatman-Freedman A, Kaufman Z, Arima Y, Oishi K, Chaves S, Nyawanda B, Al-Jarallah RA, Kuri-Morales PA, Matus CR, Corona MEJ, Burmaa A, Darmaa O, Obtel M, Cherkaoui I, van den Wijngaard CC, van der Hoek W, Baker M, Bandaranayake D, Bissielo A, Huang S, Lopez L, Newbern C, Flem E, Grøneng GM, Hauge S, de Cosío FG, de Moltó Y, Castillo LM, Cabello MA, von Horoch M, Medina Osis J, Machado A, Nunes B, Rodrigues AP, Rodrigues E, Calomfirescu C, Lupulescu E, Popescu R, Popovici O, Bogdanovic D, Kostic M, Lazarevic K, Milosevic Z, Tiodorovic B, Chen M, Cutter J, Lee V, Lin R, Ma S, Cohen AL, Treurnicht F, Kim WJ, Delgado-Sanz C, de mateo Ontañón S, Larrauri A, León IL, Vallejo F, Born R, Junker C, Koch D, Chuang JH, Huang WT, Kuo HW, Tsai YC, Bundhamcharoen K, Chittaganpitch M, Green HK, Pebody R, Goñi N, Chiparelli H, Brammer L, Mustaquim D, Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study, Lancet 391 (2018) 1285–1300. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].NIAID Emerging Infectious Diseases/ Pathogens | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, (n.d.) https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/emerging-infectious-diseases-pathogens (accessed May 24, 2022).

- [5].Wong SS, Webby RJ, Traditional and new influenza vaccines, Clin Microbiol Rev 26 (2013) 476–492. 10.1128/CMR.00097-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Paules CI, Sullivan SG, Subbarao K, Fauci AS, Chasing Seasonal Influenza — The Need for a Universal Influenza Vaccine, New England Journal of Medicine 378 (2018) 7–9. 10.1056/NEJMP1714916/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMP1714916_DISCLOSURES.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gao H-N, Lu H-Z, Cao B, Du B, Shang H, Gan J-H, Lu S-H, Yang Y-D, Fang Q, Shen Y-Z, Xi X-M, Gu Q, Zhou X-M, Qu H-P, Yan Z, Li F-M, Zhao W, Gao Z-C, Wang G-F, Ruan L-X, Wang W-H, Ye J, Cao H-F, Li X-W, Zhang W-H, Fang X-C, He J, Liang W-F, Xie J, Zeng M, Wu X-Z, Li J, Xia Q, Jin Z-C, Chen Q, Tang C, Zhang Z-Y, Hou B-M, Feng Z-X, Sheng J-F, Zhong N-S, Li L-J, Gao H, Lu H, Gan J, Lu S, Clinical Findings in 111 Cases of Influenza A (H7N9) Virus Infection A BS T R AC T background, N Engl J Med 368 (2013) 2277–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, Chen J, Jie Z, Qiu H, Xu K, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu W, Gao Z, Xiang N, Shen Y, He Z, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Zhao X, Zhou L, Li X, Zou S, Zhang Y, Li X, Yang L, Guo J, Dong J, Li Q, Dong L, Zhu Y, Bai T, Wang S, Hao P, Yang W, Zhang Y, Han J, Yu H, Li D, Gao GF, Wu G, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Shu Y, Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus, N Engl J Med 368 (2013) 1888–1897. 10.1056/NEJMOA1304459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS, Pandemic influenza viruses--hoping for the road not taken, N Engl J Med 368 (2013) 2345–2348. 10.1056/NEJMP1307009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Global Macroeconomic Consequences of Pandemic Influenza, (n.d.) https://www.brookings.edu/research/global-macroeconomic-consequences-of-pandemic-influenza/ (accessed May 24, 2022).

- [11].Herfst S, Schrauwen EJA, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM, Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets, Science 336 (2012) 1534–1541. 10.1126/SCIENCE.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, Li C, Kawakami E, Yamada S, Kiso M, Suzuki Y, Maher EA, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets, Nature 2012 486:7403. 486 (2012) 420–428. 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA, Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Lancet Infect Dis 12 (2012) 36–44. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, del Mar C, Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis, BMJ 339 (2009) 1364. 10.1136/BMJ.B5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG, Influenza Virus Resistance to Antiviral Agents: A Plea for Rational Use, Clin Infect Dis 48 (2009) 1254. 10.1086/598989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oh DY, Panozzo J, Vitesnik S, Farrukee R, Piedrafita D, Mosse J, Hurt AC, Selection of multi-drug resistant influenza A and B viruses under zanamivir pressure and their replication fitness in ferrets, Antivir Ther 23 (2018) 295–306. 10.3851/IMP3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].ZANAMIVIR | Drug | BNF content published by NICE, (n.d.) https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/zanamivir.html (accessed February 21, 2022).

- [18].Shelton MJ, Lovern M, Ng-Cashin J, Jones L, Gould E, Gauvin J, Rodvold KA, Zanamivir pharmacokinetics and pulmonary penetration into epithelial lining fluid following intravenous or oral inhaled administration to healthy adult subjects, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55 (2011) 5178–5184. 10.1128/AAC.00703-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chan-Tack KM, Murray JS, Birnkrant DB, Use of ribavirin to treat influenza, N Engl J Med 361 (2009) 1713–1714. 10.1056/NEJMC0905290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brown AN, Bulitta JB, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Adams JR, Kulawy R, Drusano GL, Effect of half-life on the pharmacodynamic index of zanamivir against influenza virus delineated by a mathematical model, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55 (2011) 1747–1753. 10.1128/AAC.01629-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].McAlister E, Dutton B, Vora LK, Zhao L, Ripolin A, Zahari DSZBPH, Quinn HL, Tekko IA, Courtenay AJ, Kelly SA, Rodgers AM, Steiner L, Levin G, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Shterman N, McCarthy HO, Donnelly RF, Directly Compressed Tablets: A Novel Drug-Containing Reservoir Combined with Hydrogel-Forming Microneedle Arrays for Transdermal Drug Delivery, Adv Healthc Mater 10 (2021) 2001256. 10.1002/ADHM.202001256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Anjani QK, Permana AD, Cárcamo-Martínez Á, Domínguez-Robles J, Tekko IA, Larrañeta E, Vora LK, Ramadon D, Donnelly RF, Versatility of hydrogel-forming microneedles in in vitro transdermal delivery of tuberculosis drugs, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 294–312 (2021) 294–312. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [23].Hutton ARJ, McCrudden MTC, Larrañeta E, Donnelly RF, Influence of molecular weight on transdermal delivery of model macromolecules using hydrogel-forming microneedles: potential to enhance the administration of novel low molecular weight biotherapeutics, J Mater Chem B 8 (2020) 4202–4209. 10.1039/D0TB00021C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Donnelly RF, Singh TRR, Garland MJ, Migalska K, Majithiya R, McCrudden CM, Kole PL, Mahmood TMT, McCarthy HO, Woolfson AD, Hydrogel-Forming Microneedle Arrays for Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery, Adv Funct Mater 22 (2012) 4879. 10.1002/ADFM.201200864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Harvey AJ, Kaestner SA, Sutter DE, Harvey NG, Mikszta JA, Pettis RJ, Microneedle-based intradermal delivery enables rapid lymphatic uptake and distribution of protein drugs, Pharm Res 28 (2011) 107–116. 10.1007/S11095-010-0123-9/FIGURES/5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hidayat Bin Sabri A, Kurnia Anjani Q, Donnelly RF, Synthesis and characterization of sorbitol laced hydrogel-forming microneedles for therapeutic drug monitoring, Int J Pharm 607 (2021) 121049. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bin Sabri AH, Anjani QK, Utomo E, Ripolin A, Donnelly RF, Development and characterization of a dry reservoir-hydrogel-forming microneedles composite for minimally invasive delivery of cefazolin, Int J Pharm 617 (2022) 121593. 10.1016/J.IJPHARM.2022.121593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].ICH, International Council on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use, in: 2005: pp. 1070–1072. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00861-7. [DOI]

- [29].Brown AN, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Driebe EM, Engelthaler DM, Sheff K, Keim PS, Nguyen J, Drusano GL, In Vitro System for Modeling Influenza A Virus Resistance under Drug Pressure, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54 (2010) 3442. 10.1128/AAC.01385-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brown AN, Bulitta JB, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Adams JR, Kulawy R, Drusano GL, Effect of Half-Life on the Pharmacodynamic Index of Zanamivir against Influenza Virus Delineated by a Mathematical Model, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55 (2011) 1747. 10.1128/AAC.01629-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Brown A, Kulawy R, Drusano GL, Prediction of the Pharmacodynamically Linked Variable of Oseltamivir Carboxylate for Influenza A Virus Using an In Vitro Hollow-Fiber Infection Model System, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53 (2009) 2375. 10.1128/AAC.00167-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Huprikar J, Rabinowitz S, A simplified plaque assay for influenza viruses in Madin-Darby kidney (MDCK) cells, J Virol Methods 1 (1980) 117–120. 10.1016/0166-0934(80)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].bin Sabri AH, Anjani QK, Donnelly RF, Synthesis and characterization of sorbitol laced hydrogel-forming microneedles for therapeutic drug monitoring, Int J Pharm 607 (2021) 121049. 10.1016/J.IJPHARM.2021.121049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].David SE, Timmins P, Conway BR, Impact of the counterion on the solubility and physicochemical properties of salts of carboxylic acid drugs, Drug Dev Ind Pharm 38 (2012) 93–103. 10.3109/03639045.2011.592530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Al-Kasasbeh R, Brady AJ, Courtenay AJ, Larrañeta E, McCrudden MTC, O’Kane D, Liggett S, Donnelly RF, Evaluation of the clinical impact of repeat application of hydrogel-forming microneedle array patches, Drug Deliv Transl Res 10 (2020) 690–705. 10.1007/S13346-020-00727-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sandby-Møller J, Poulsen T, Wulf HC, Epidermal Thickness at Different Body Sites: Relationship to Age, Gender, Pigmentation, Blood Content, Skin Type and Smoking Habits, Acta Derm Venereol 83 (2003) 410–413. 10.1080/00015550310015419/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang L, Liu L, Qian Y, Chen Y, The effects of cryoprotectants on the freeze-drying of ibuprofen-loaded solid lipid microparticles (SLM), Eur J Pharm Biopharm 69 (2008) 750–759. 10.1016/J.EJPB.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Advances in Swine in Biomedical Research, Advances in Swine in Biomedical Research (1996). 10.1007/978-1-4615-5885-9. [DOI]

- [39].Svendsen O, The minipig in toxicology, Exp Toxicol Pathol 57 (2006) 335–339. 10.1016/J.ETP.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Smee DF, Julander JG, Bart Tarbet E, Gross M, Nguyen J, Treatment of Oseltamivir-Resistant Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infections in Mice With Antiviral Agents, Antiviral Res 96 (2012) 13. 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Okomo-Adhiambo M, Sleeman K, Lysén C, Nguyen HT, Xu X, Li Y, Klimov AI, Gubareva L. v., Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility surveillance of influenza viruses circulating worldwide during the 2011 Southern Hemisphere season, Influenza Other Respir Viruses 7 (2013) 645–658. 10.1111/IRV.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]