In his 2019 State of the Union address, President Donald Trump announced a new initiative with the ambitious goal of reducing HIV transmission in the United States by 90% within 10 years, in part by focusing on the burden of disease in rural America. The Department of Health and Human Services has outlined several steps for achieving this goal but hasn’t focused on the role of injection-drug use in HIV transmission.

Ever since the 2015 outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Scott County, Indiana, it has been clear that the sharing of syringes among people who inject drugs is fueling the spread of these diseases in rural America. After intense resistance, then-Governor of Indiana Mike Pence declared a public health emergency in response to the outbreak and authorized a temporary syringe-exchange program. The program was successful, with 277 enrollees and more than 90,000 syringes distributed and returned between April and October 2015,1 and the number of new HIV infections decreased. The Scott County outbreak was a wake-up call for advocates, epidemiologists, policymakers, and program administrators throughout the United States. Never before had the country seen such a swift outbreak of HIV in a rural community.

Soon after the outbreak ended, Congress overturned a long-standing ban on using federal funding to support syringe-exchange programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) then released a report identifying the 220 rural counties in the United States that were most vulnerable to HIV and HCV outbreaks among people who inject drugs. The director of the CDC at the time, Tom Frieden, called the sharing of unsterile syringes a “horrifyingly efficient route for spreading HIV, hepatitis, and other infections” and called for states to implement more syringe-exchange programs.2

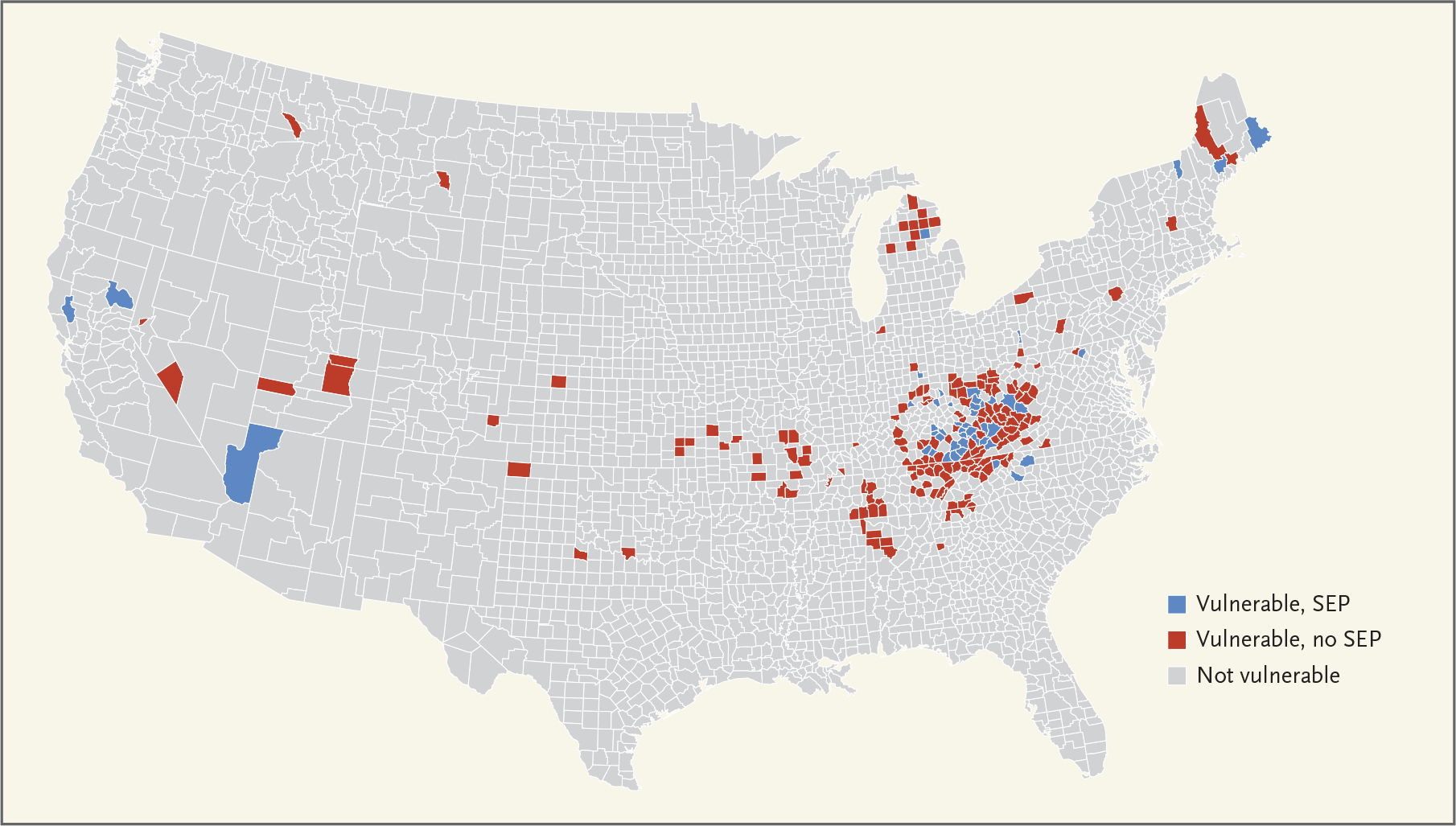

The aftermath of the Scott County outbreak presented an opportunity for a transformative change in the use of harm-reduction interventions in rural America, as syringe-exchange programs regained prominence as cost-effective tools for reducing the spread of HIV and HCV in the midst of rising rates of injection-drug use. We examined the adoption of syringe-exchange programs in the 220 counties identified in the CDC report, using publicly available data from the North American Syringe Exchange Network and state departments of health. Our analysis revealed that less than a quarter of these vulnerable counties (47 of 220) were operating syringe-exchange programs in 2018 (see map). The outbreak in Scott County may have been a warning sign, but the message hasn’t been heeded in many parts of the country.

U.S. Counties’ Vulnerability to HIV and HCV Outbreaks and Their Syringe-Exchange Program (SEP) Status.

Data are as of 2018 and are from the CDC and the North American Syringe Exchange Network.

This tepid response is not attributable to a lack of evidence. Syringe-exchange programs have existed for decades in the United States. Such programs were originally pioneered by people who inject drugs and were later adopted as a public health intervention in the midst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. A 2014 meta-analysis of 12 studies found convincing evidence that needle- and syringe-exchange programs are associated with reductions in HIV transmission,3 and a 2017 Cochrane review suggested that a combination of syringe-exchange programs and opioid-substitution therapy could reduce the risk of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs.4 Along with the CDC, the American Medical Association, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine), and the World Health Organization all support syringe-exchange programs as important interventions that reduce the spread of infectious disease and can serve as gateways to obtaining naloxone, opioid-substitution therapy, HIV and HCV testing and treatment, and other medical care.

Yet stigma has remained a critical barrier. In the midst of a devastating public health crisis, large regions of the country are locked in an ideological battle about the morality of harm reduction. Although a 2007 systematic review by the Institute of Medicine found no evidence that syringe-exchange programs increase the frequency of injection-drug use, expand substance-use networks, or facilitate local crime, fears remain widespread that harm-reduction programs will promote drug use and threaten the existing social order.5 These concerns have had profound consequences: only 21 states have explicitly authorized syringe-exchange programs.

Even states that have authorized harm-reduction approaches have struggled to implement specific programs. Virginia passed a law in 2017 granting certain counties the ability to operate syringe-exchange programs, but it required public health officials to obtain formal consent from local law-enforcement officers because the legislation did not exempt participants from drug-paraphernalia laws. In essence, the law asked police to turn a blind eye to syringe-exchange programs since possession of syringes was still illegal under existing statutes. Unsurprisingly, only three districts have been able to build enough local consensus to move forward.

Kentucky passed legislation in 2015 authorizing syringe-exchange programs and is now a national leader in this area, with more than 50 programs operating statewide. Yet of the state’s 54 counties classified as most vulnerable by the CDC, only half have such a program. Kentucky’s legislation also mandates that all programs restrict exchanges to “one-to-one” interventions, meaning that only one clean syringe can be distributed for each dirty syringe returned. Such restrictions may limit the effect of exchange programs on the spread of infectious disease. More liberal strategies allow multiple or unlimited syringes to be dispensed, regardless of the number of syringes returned.

To be clear, syringe-exchange programs are just one component of a continuum of harm-reduction services and by themselves are not enough to prevent transmission of infectious disease or overdoses. Such programs can be offered in conjunction with other interventions, such as opioid-substitution therapy and naloxone distribution. Access to opioid-substitution therapy also remains an important concern in rural areas. For example, we found that less than 60% of the counties most vulnerable to HIV and HCV outbreaks (127 of 220) had a buprenorphine prescriber in 2018, according to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration registries.

Lack of access to opioid-substitution therapy in these areas is probably rooted in the same stigma that limits implementation of syringe-exchange programs. In addition to obtaining a waiver and prescribing buprenorphine (which all physicians can consider doing), distributing naloxone widely, and advocating for our patients’ basic needs, health professionals can confront stigma and support the expansion of harm-reduction approaches in several ways.

At the local level, clinicians can partner with people who inject drugs, listen to their experiences, and engage stakeholders — including mayors, police, and faith leaders — to offer education about harm reduction and address concerns. At the state level, they can advocate for laws that authorize comprehensive syringe-exchange programs, decriminalize possession of syringes and residual substances, and guarantee access to over-the-counter syringes without a prescription. At the national level, clinicians can encourage their elected representatives to support harm reduction as a core component of the country’s public health strategy. Just as Surgeon General Jerome Adams called for more people to carry naloxone, he could call on state leaders to ensure that syringe-exchange programs and opioid-substitution therapy are available in all counties nationwide.

Finally, once these programs are authorized, clinicians can establish direct connections between syringe-exchange programs and health systems to ensure that people with addiction receive the care they need and are treated with dignity.

Four years after the United States received a wake-up call about the importance of harm reduction, the most vulnerable areas of the country remain asleep. Despite the federal government’s goal of ending the HIV epidemic in the United States, it’s not clear that it will do what is necessary to address the spread of HIV and HCV in rural America. Health professionals can advocate for legal changes that authorize syringe-exchange programs and other lifesaving interventions.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

Sanjay Kishore, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Margaret Hayden, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Josiah Rich, Brown University and the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights at the Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI

References

- 1.Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med 2016;375:229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi J CDC says more needle exchange programs needed to prevent HIV. JAMA 2017;317:350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:CD012021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high-risk countries: an assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2007. (https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11731/preventing-hiv-infection-among-injecting-drug-users-in-high-risk-countries). [Google Scholar]