Abstract

Introduction

No studies have prospectively explored the association between the use of tobacco or cannabis use and the age of onset of depressive or anxiety symptoms, and no studies have identified the peak ages and ranges of onset of these symptoms among tobacco and/or cannabis users.

Aims and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance System data, waves 9–14 (2019–20121). Participants were in 10th grade, 12th grade, and 2 years post-high school (HS) at baseline (wave 9). Interval-censoring multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were fit to assess differences in the estimated age of onset of depression and anxiety by tobacco and cannabis use while adjusting for covariates.

Results

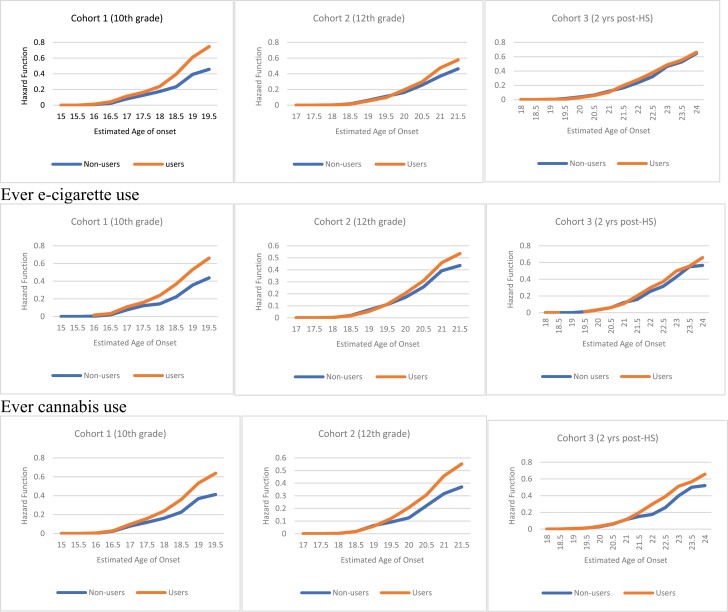

We found that lifetime or ever cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use had an increased risk of an earlier age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms across the three cohorts, and the youngest cohort was the most differentially impacted by substance use. Between ages 18 to 19 years in the 10th-grade cohort, between ages 20 to 21 years in the 12th-grade cohort, and between ages 22 to 23 years in the post-HS cohort, the estimated hazard function (or cumulative incidence) for reporting depressive and anxiety symptoms almost doubled among lifetime cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis users.

Conclusions

Tobacco and cannabis users should be screened for mental health problems at an earlier age, especially those aged 18 years and younger, and provided with age- and culturally appropriate resources to prevent or delay the onset of anxiety and/or depression symptoms.

Implications

The study’s findings indicate that tobacco and cannabis use is directly linked to the early onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms among youth. This highlights the significance of early screening and substance use interventions, particularly for youth aged 18 years and younger, as they are disproportionately affected by both substance use and mental health problems. School-based interventions that are age- and culturally appropriate hold promise as they enable youth to seek professional help early, and in a supportive environment. Intervening early in substance shows promise in reducing the likelihood of developing mental health problems at a young age.

Introduction

Nicotine and cannabis are two of the most widely used substances among adolescents and young adults in the United States. In 2020, past-month use of tobacco and cannabis among adolescents was 16.2% and 34.5%, respectively, and among young adults was 17.6% and 10.1%, respectively.1 Rates for both age groups have increased since 2008 and are highest among young adults compared to any other adult age group.1 Early exposure and use of these substances may have negative impacts on brain development and may increase the subsequent risk for cognitive and mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety.2,3 However, the direction of this association remains uncertain.4 Moreover, cannabis consumption has been observed to show analogous adverse consequences as tobacco consumption, including dependence and toxicant exposure. Nonetheless, the association between cannabis use and lung disease and lung cancer remains unclear.5,6

Tobacco and the Onset of Depression and Anxiety

The prevalence of tobacco has been declining in the general population; however, individuals with mental health problems, particularly depression and anxiety, have higher smoking rates and levels of nicotine dependence.7 Approximately one in four adults in the U.S. report some form of mental health condition, and these adults consume almost 40% of all cigarettes smoked by adults.7 Research shows that cigarette and e-cigarette use can influence the onset and progression of depression and anxiety through neurophysiological processes that are altered by exposure to nicotine.8 Longitudinal studies reveal that individuals who use cigarettes or e-cigarettes are more likely to report symptoms of anxiety, and depression, and comorbid symptoms when compared to nonusers.9,10 Furthermore, evidence from animal studies suggests that early-age nicotine exposure induces anxiety-like and depression-like states in adulthood, as compared to late-age exposure.11,12 These associations remained significant even after controlling for common confounding factors.9 Despite this well-established association between smoking tobacco and the onset of depression and anxiety, there is a lack of research specifically examining whether smoking predicts the age of onset of depression and anxiety in youth, which would provide important information about etiological drivers of the behavior and provide clear implications and therapeutic targets for interventions.

Cannabis and the Onset of Depression and Anxiety

According to national data (2019), 48.2 million Americans aged 12 years and older reported at least one instance of cannabis use in the past month, and the percentage who were past-year cannabis users increased from 11.0% (or ~25.8 million people) in 2002 to 17.5% (or ~48.2 million people) in 2019.12 The increases in cannabis use in recent years, and rapid changes to laws and normative perceptions, highlight the importance of understanding the consequences of cannabis use on the onset of depression and anxiety. While research on this topic has been inconclusive, several studies have found that earlier onset and heavier use of cannabis are associated with an increased risk of developing depression and anxiety, particularly in adolescents and young adults.13,14 For example, one study found that an earlier onset of cannabis use was associated with a shorter time to develop depression disorder.14 However, other studies have found that cannabis use may have a protective effect on mental health. For example, a recent longitudinal study found that while the onset of depression occurred at a younger age in the non-cannabis-using population than in those who used cannabis, there was no significant difference in the number of lifetime episodes of major depression disorder between the groups.15 These findings may imply that cannabis may have anti-depressant activity because of specific cannabinoids.16 Furthermore, in other studies, the association between cannabis use and mental health problems was no longer significant after controlling for confounders, such as alcohol use, and adverse childhood experiences.14

Despite the progress in understanding the relationship between tobacco or cannabis use and the emergence of mental health problems, there are key limitations to past work. Specifically, while it has been established that the early onset of depression and anxiety in youth is associated with an increased risk of adult mental health and substance use disorders, poor health outcomes, reduced educational attainment, and elevated suicidality, there is a lack of prospective research that directly examines the association between tobacco or cannabis use and the age of onset of depression and anxiety among youth. Additionally, there is a gap in research that identifies the peak ages and ranges of onset of mental health problems among individuals who use tobacco or cannabis. Thus, it is crucial to replicate and expand upon previous research to address these important research gaps. Using data from the Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance System (TATAMS), we examined whether lifetime or ever cigarette, e-cigarette, or cannabis use predicts the age of onset of (1) depressive, and (2) anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data were drawn from TATAMS for the years 2019–2021 (waves 9–14). TATAMS is an ongoing research project that focuses on tobacco and cannabis use among a cohort of adolescents attending public, charter, and private schools in the four largest metropolitan areas (Houston, Dallas/Fort Worth, San Antonio, and Austin) in five counties (Bexar, Dallas, Harris, Tarrant, and Travis) in Texas. Further description of TATAMS’ methodology is provided elsewhere.17 Participants were in 10th grade, 12th grade, and 2 years post-high school in wave 9, in Spring, 2019 when data were gathered using computerized surveys. TATAMS human subjects’ methods were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board (HSC-SPH-13-0377). The eligible sample for this analysis includes all students who have complete data on covariates and reported no depressive (n = 1904) or anxiety symptoms (n = 1984) at baseline (w-9).

Measures

Time-Varying Exposure (s)

Ever Cigarettes Use

At each wave (w9–w14), participants who never used cigarettes were asked “Have you ever tried smoking, even one or two puffs?” Participants who responded “Yes” to this question were considered participants who use cigarettes (lifetime).

Ever E-cigarettes Use

At each wave (w9–w14), never e-cigarette users were asked, “Have you ever used an electronic cigarette, vape pen, or e-hookah, even one or two puffs?” Participants who responded “Yes” to this question were considered as participants who ever-use e-cigarettes (lifetime). Participants were asked to answer only about the use of e-cigarettes without cannabis.

Ever Cannabis Use

At each wave (w9–w14), individuals who never used cannabis were asked, “Have you EVER smoked, used, or consumed marijuana in any form including joints, vaping, edibles, dabbing, sprays, etc.?” Participants who responded “Yes” to this question were considered individuals who ever-use cannabis (lifetime).

Mental Health Measures

Depression

In waves 9-14, depressive symptoms were assessed with the PHQ-9 instrument,18 which contains nine items that measure the frequency of depressive symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks (48). For example, “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems… little interest or pleasure in doing things, feeling down, depressed, or hopeless, etc.” The response options for each item are “0 = not at all,” “1 = on several days,” “2 = on more than half of the days,” and “3 = nearly every day.” Items are summed to create a total score, with a possible range of 0 to 27. Participants who reported that (1) five or more of the nine depressive symptoms have been present for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, and (2) one of the symptoms is depressed mood or anhedonia (PHQ-9 scores of ≥10), were categorized as having at least moderate levels of depressive symptoms (48).

Anxiety

In waves 9–14, anxiety symptoms were assessed with the GAD-7 instrument,19 which contains seven symptom items that measure the frequency of anxiety symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks. For example, “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by … feeling nervous, anxious or on edge, not being able to stop or control worrying, etc.” The response options for each item are “not at all,” “on several days,” “on more than half of the days,” and “nearly every day,” scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. A severity score index was calculated by adding the scores assigned to the response options for each symptom, with a possible range of 0 to 21. We used the recommended cutoff of ≥10, which indicates that individuals are likely experiencing moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety (49).

Interval-Censored Outcome

Age of Onset of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms.

The age of first reporting anxiety or depressive symptoms was prospectively estimated by creating lower and upper age bounds to identify the age at the last wave when the participant reported no depressive or anxiety symptoms and the age at the wave when they first reported depressive or anxiety symptoms. For participants who had not reported depressive or anxiety symptoms over the follow-up period (2019–2021), their upper bound was censored. Participant age at each wave was converted from age in days to age in years on a continuous scale, to provide a more precise estimate of participant age.

Covariates

The covariates in the analysis include: Gender, race/ethnicity, family socioeconomic status (SES), and wave.

Race/Ethnicity

Race/ethnicity was measured by the following questions: “Are you Hispanic or Latino/a?” and “What race or races do you consider yourself to be?,” respectively. Response options were used to derive a single measure of race/ethnicity: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other.

Family SES

Family SES was measured by, “In terms of income, what best describes your family’s standard of living in the home where you live most of the time?” with response options categorized as high (“very well off”), middle (“living comfortably”), and low (“just getting by,” “nearly poor,” and “poor”).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported by cohort (Table 1). The age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms was estimated using interval-censoring survival analysis. The hazard function (and its 95% confidence intervals) for the two outcomes were reported as cumulative probabilities (Table 2 and Figure 1). Separate interval-censoring Cox proportional hazards regression models were conducted to test the differences in the estimated age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms by ever-use status (users vs. nonusers), adjusting for covariates (Table 3). In this analysis, ever or lifetime use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis were modeled as time-varying exposures. Therefore, each was measured at all waves prior to the onset of the outcome for those who develop depressive or anxiety symptoms and at all waves prior to censoring for those who remain and do not have depressive or anxiety symptoms. All analyses were conducted separately by cohort and were conducted using SAS version 9.4. A type I error level of .05 was used and all p-values were two-sided.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample by Cohort, W9, TATAMS

| No depressive symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Overall (n = 1904) n (%) |

Cohort 1 (10th grade) (n = 548) n (%) |

Cohort 2 (12th grade) (n = 677) n (%) |

Cohort 3 (Post HS) (n = 679) n %) |

| Gender Female Male |

1027 (53.9) 877 (46.1) |

300 (54.7) 248 (45.3) |

345 (52.3) 323 (47.7) |

373 (54.9) 306 (45.1) |

| Race/ethnicity NH-white NH-AA Hispanic NH-Other |

638 (33.5) 285 (15.0) 675 (35.5) 306 (16.1) |

193 (35.2) 66 (12.0) 197 (36.0) 92 (16.8) |

244 (36.0) 91 (13.4) 233 (34.4) 109 (16.1) |

201 (29.6) 128 (18.9) 245 (36.1) 105 (15.5) |

| SESb Low Medium High Missing |

407 (21.4) 1240 (65.1) 250 (13.1) 7.0 (0.4) |

85 (15.5) 371 (67.7) 91 (16.6) 1.0 (0.2) |

131 (19.4) 435 (64.3) 105 (15.5) 6.0 (0.9) |

191 (28.1) 434 (63.9) 54 (8.0) 0.0 (0.0) |

| No anxiety symptoms | ||||

| Cohort | Overall (n = 1984) n (%) |

Cohort 1 (10th grade) (n = 565) n (%) |

Cohort 2 (12th grade) (n = 691) n (%) |

Cohort 3 (Post HS) (n = 728) n (%) |

| Gender Female Male |

1057 (53.30) 927 (46.70) |

308 (54.5) 257 (45.5) |

356 (51.5) 335 (48.5) |

393 (54.0) 335 (46.0) |

| Race/ethnicity NH-white NH-black Hispanic NH-Other |

635 (32.0) 295 (14.9) 726 (36.6) 328 (16.5) |

193 (34.2) 63 (11.2) 211 (37.4) 98 (34.2) |

244 (35.3) 90 (13.0) 243 (35.2) 114 (35.3) |

198 (27.2) 142 (19.5) 272 (37.4) 116 (15.9) |

| SESb Low Medium High Missing |

439 (22.1) 1282 (64.6) 256 (12.9) 7.0 (0.6) |

92 (16.3) 377 (66.7) 95 (16.8) 1.0 (0.2) |

133 (19.3) 447 (64.7) 105 (15.2) 6.0 (0.9) |

214 (29.4) 458 (62.9) 56 (7.7) 0.0 (0.0) |

aIncludes Asian, American Indian, or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and Other (not listed).

bSocioeconomic status.

Table 2.

Estimated Hazard Function* (95% Confidence Interval) of the Onset of Mental Health Symptoms Stratified by Use Status and Cohort in Youth/Emerging Adults, W9–W14, TATAMS

| Ever cigarette use | Ever e-cigarette use | Ever cannabis use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Age (years) | Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Cohort 1 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) |

| 17 | 8.1 (7.2–9.2) | 11.4 (8.6–15.1) | 7.5 (6.5–8.7) | 10.8 (9.0–13.1) | 7.8 (6.7–9.1) | 9.7 (8.0–11.6) |

| 18 | 23.4 (19.5–22.6) | 23.9 (19.3–28.7) | 14.4 (12.9–16.0) | 23.8 (21.1–26.8) | 16.2 (14.5–18.1) | 23.8 (21.2–26.6) |

| 19* | 45.7 (42.3–45.9) | 74.1 (68.8–79.1) | 35.6 (33.4–37.9) | 53.1 (49.4–56.9) | 41.2 (38.1–44.6) | 63.7 (60.0–67.3) |

| Cohort 2 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 18 | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.3 (0.2–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) |

| 19 | 6.3 (5.4–7.3) | 5.4 (4.2–6.9) | 6.6 (5.5–7.8) | 5.4 (4.4–6.6) | 6.5 (5.4–7.8) | 6.0 (4.9–7.2) |

| 20 | 16.2 (14.8–17.8) | 19.5 (17.3–33.0) | 17.0 (15.2–18.8) | 20.4 (15.7–22.4) | 12.5 (11.0–14.2) | 20.7 (18.9–22.6) |

| 21.5 | 46.3 (43.7–49.1) | 57.7 (54.5–60.9) | 43.2 (41.9–45.8) | 53.5 (50.9–56.2) | 37.0 (33.4–40.8) | 55.2 (52.8–57.7) |

| 22 | N/A | 66.2 | N/A | 62.8 | N/A | 61.6 (57.7–65.50) |

| Cohort 3 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | 0.3 (0.1–1.0) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| 20 | 3.7 (3.0–4.6) | 2.9 (2.1 –3.1) | 3.3 (2.5–4.4) | 3.5 (3.2–5.1) | 3.0 (2.2–4.1) | 3.5 (2.9–4.3) |

| 21 | 11.6 (10.4–13.1) | 10.3 (9.0 –11.8) | 12.1 (10.6–13.9) | 10.9 (9.7–12.1) | 11.4 (9.8–13.2) | 11.2 (10.0–12.4) |

| 22 | 23.7 (22.0–25.6) | 27.9 (25.8–30.2) | 25.4 (23.2–27.7) | 29.7 (27.8–31.6) | 17.5 (15.6–19.7) | 29.8 (28.0–31.6) |

| 23 | 46.5 (43.9–49.0) | 48.5 (46.0–51.0) | 42.8 (39.6–46.1) | 49.8 (47.7–51.9) | 39.7 (37.0–42.6) | 51.3 (49.3–53.4) |

| 24 | 64.5 (60.2–68.9) | 66.2 (60.3–72) | 56.5 (51.7–61.5) | 65.8 (59.7–71.9) | 52.0 (49.1–55.1) | 65.7 (59.8–71.5) |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| Cohort 1 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 0.6 (0.1–2.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.2) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) |

| 17 | 7.4 (6.1–9.5) | 8.6 (6.2–11.9) | 8.3 (7.2–9.6) | 8.4 (6.8–10.3) | 8.1 (6.9–9.4) | 6.2 (4.8–7.9) |

| 18 | 21.7 (20.1–23.3) | 27.0 (22.8–31.9) | 21.8 (20.1–23.7) | 22.5 (19.8–25.5) | 22.0 (20.1–23.9) | 22.3 (19.9–25.0) |

| 19* | 51.8 (49.5–54.2) | 68.9 (64.1–73.5) | 53.3 (50.2–56.6) | 57.4 (54.0–60.8) | 47.0 (42.6–51.7) | 63.3 (59.8–66.8) |

| Cohort 2 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 18 | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.1 (0.0–0.5) |

| 19 | 5.5 (4.7–6.4) | 4.9 (3.8–6.4) | 5.9 (4.9–7.0) | 4.6 (3.7–5.8) | 6.7 (5.6–8.0) | 4.5 (3.7–5.6) |

| 20 | 16.9 (15.5–18.5) | 18.8 (16.6–21.2) | 17.1 (15.4–19.0) | 17.8 (16.1–19.7) | 13.8 (12.3–15) | 19.1 (17.4–21.0) |

| 21 | 37.6 (35.6–40.7) | 51.8 (48.6–55.2) | 38.1 (35.7–40.5) | 46.6 (43.9–49.3) | 32.9 (30.5–35.4) | 48.1 (45.5–50.8) |

| 22 | 53.2 (49.9–56.5) | 60.3 (57.1–63.6) | 52.5 (48.8–56.3) | 57.7 (54.9–60.4) | 53.7 (49.9–57.6) | 58.3 (61.1–73.7) |

| Cohort 3 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| 20 | 3.6 (2.9–4.5) | 2.5 (1.9–3.4) | 4.4 (3.5–5.6) | 2.1 (1.7–2.8) | 3.6 (3.0–4.8) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) |

| 21 | 11.2 (10.0–12.6) | 11.6 (10.1–13.2) | 11.4 (9.9–13.2) | 11.1 (9.9–12.4) | 10.8 (9.2–12.6) | 12.5 (11.3–13.8) |

| 22 | 26.8 (25.0–28.8) | 30.6 (28.5–32.7) | 25.3 (23.1–27.6) | 30 (28.3–31.8) | 30.0 (21.6–26.5) | 30.1 (28.5–31.9) |

| 23 | 42.5 (40.5–44.6) | 53.0 (50.7–55.3) | 43.6 (41–46.3) | 50.7 (48.7–52.7) | 39.1 (36.5–41.8) | 51.3 (49.3–53.3) |

| 24 | 57.7 (55.7–59.7) | 63.8 (60.0–67.6) | N/A | 71.9 (67.8–75.9) | 44.6 (41.7–51.1) | 70.0 (65.9–73.9) |

Bold indicates statistical significance, p < .05.

Hazards are reported as cumulative percentages (ie, cumulative incidence).

N/A: there was not enough sample size to estimate a stable initiation at this age.

*This age represents 19 years old and 4 months.

Figure 1.

(A) Estimated hazard function for the age of onset of depressive symptoms.(B) Estimated hazard function for the age of onset of anxiety symptoms

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios for the Association Between Ever Cigarette, E-cigarette and Cannabis Use and the Age of Onset of Mental Health Symptoms

| Cohort 1 (10th grade) |

Cohort 2 (12th grade) |

Cohort 3 (2 years post HS) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| HR [95% CI] | AHR [95% CI] | HR [95% CI] | AHR [95% CI] | HR [95% CI] | AHR [95% CI] | |

| Cigarette (user’s vs. nonusers) |

2.37 (1.77 to 3.17) | 2.1 (1.49 to 2.95) | 1.42 (1.13 to 1.79) | 1.52 (1.51 to 2.00) | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.48) | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) |

| E-cigarette (user’s vs. nonusers) |

1.79 (1.43 to 2.24) | 1.78 (1.34 to 2.37) | 1.24 (0.98 to 1.57) | 1.27 (0.97 to 1.66) | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.41) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.42) |

| Cannabis (user’s vs. nonusers) |

1.78(1.42 to 2.43) | 1.68 (1.27 to 2.22) | 1.84 (1.35 to 2.35) | 1.71(1.49 to 2.28) | 1.40 (1.11 to 1.75) | 1.31(1.01 to 1.70) |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| Cigarette (user’s vs. nonusers) |

1.89 (1.30 to 2.76) | 1.80 (1.23 to 2.65) | 1.38 (1.04 to 1.83) | 1.52 (1.13 to 2.05) | 1.13 (0.87 to 1.44) | 1.15 (0.88 to 1.49) |

| E-cigarette (user’s vs. nonusers) |

1.63 (1.22 to 2.18) | 1.58 (1.16 to 2.17) | 1.07 (0.81 to 1.42) | 1.07 (0.80 to 143) | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.32 | 1.02 (0.78 to 1.33) |

| Cannabis (user’s vs. nonusers) |

1.54 (1.13 to 2.09) | 1.47 (1.08 to 2.00) | 1.60 (1.24 to 2.07) | 1.46 (1.08 to 1.97) | 1.22 (0.95 to 1.56) | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.45) |

Bold indicates statistical significance, p < .05.

AHR: adjusted for sociodemographic factors and survey.

*Nonusers (ref).

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline demographic characteristics of youth who reported no depressive or anxiety symptoms. Of the 1904 youth who reported no depressive symptoms at baseline, 28.8 % were in the 10th-grade cohort, 35.6% were in the 12th-grade cohort, and 35.7% were in the 2 years post-HS cohort. Of the 1984 youth who reported no anxiety symptoms at baseline, 28.5% were in the 10th-grade cohort, 34.8% were in the 12th-grade cohort, and 36.7% were in the 2 years post-HS cohort. Between 10.1% to 14.9% of the participants reported both depressive and anxiety symptoms over the course of the study (data not shown). Among each of the three cohort levels, gender was approximately equally distributed, almost two-thirds of the students were classified as middle SES, and the majority self-identified as Hispanic and non-Hispanic White, followed by non-Hispanic black and other races.

Table 2 presents the cumulative probabilities of the age of onset of depression and anxiety by use status (users vs. nonusers) for cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis. Additionally, we present the hazard functions for the ages of onset of depression and anxiety for the three cohorts graphically in Figure 1. The unadjusted and adjusted results for the association between lifetime or ever cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use and the age of onset of depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms are reported in Table 3.

Age of Onset of Depressive Symptoms

Cohort 1 (10th Grade Through 1-Year Post-HS)

By age 19 years, the estimated probabilities of reporting depressive symptoms among participants who never used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 45.7%, 35.6%, and 41.2%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, they were 74.1%, 53.1%, and 63.7%, respectively (Table 2). The most marked increase in reporting depressive symptoms among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis was between ages 18 and 19 years, at 50.2%, 29.3%, and 39.9%, respectively (Table 2). As shown in the adjusted analyses (Table 3), youth who have ever used cigarettes and e-cigarettes were 110% [AHR = 2.1 (95% CI:1.49 to 2.95)] and 78% [AHR = 1.78 (95% CI:1.34 to 2.37)] more likely to develop depressive symptoms at younger ages, compared to those who have never used cigarettes or e-cigarettes. Similarly, youth who have ever used cannabis were 68% [AHR = 1.78 (95% CI:1.27 to 2.22)] more likely to develop depressive symptoms at younger ages, compared to those who have never used cannabis.

Cohort 2 (12th Grade Through 3-Year Post-HS).

By age 21 years, the estimated probabilities for reporting depressive symptoms among participants who have never used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 46.3%, 43.2%, and 37.0%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 57.7%, 53.5%, and 55.2%, respectively. The most notable increase in reporting depressive symptoms among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis were between ages 20 and 21 years, at 38.2%, 33.1%, and 34.5%, respectively. As shown in the adjusted analyses (Table 3), youth who have ever used cigarettes or cannabis were 52% [AHR = 1.51(95% CI:1.51 to 2.0)] and 71% [AHR: 1.71 (95% CI:1.49 to 2.28)] more likely to develop depressive symptoms at younger ages, compared to those who have never used cigarettes or cannabis. However, there were no significant differences in the age of onset of depressive symptoms between youth who have ever used e-cigarettes and those who have never used e-cigarettes (Table 3).

Cohort 3 (2 Years Post-HS Through 5-Year Post-HS)

By age 24 years, the estimated probabilities of reporting depressive symptoms among participants who never used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 64.5%, 56.5%, and 52.7%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 66.2%, 65.8%, and 65.7%, respectively. The most marked increase in reporting depressive symptoms among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis was between ages 22 and 23 years, at 20.6%, 20.1%, and 21.5%, respectively. Youth who have ever used cannabis were 31% [AHR = 1.31 (95% CI:1.01 to 1.70)] more likely to develop depressive symptoms at younger ages, compared to those who have never used cannabis. However, there were no significant differences in the age of onset of depressive symptoms between youth who have ever used cigarettes and e-cigarettes and those who have never used them.

Age of Onset of Anxiety Symptoms

Cohort 1 (10th Grade Through 1-Year Post-HS).

By age 19 years, the estimated probabilities for reporting anxiety symptoms among participants who never use cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 51.8%, 53.3%, and 47.0%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 68.9%%, 57.4%, and 63.3%, respectively. Youth who have ever used cigarettes and e-cigarettes were 80% [AHR = 1.80 (95% CI: 1.23 to 2.65)], and 58% [AHR = 1.58 (95% CI: 1.16 to 2.17)] more likely to develop anxiety symptoms at earlier ages compared to those who have never used cigarette and e-cigarette. Similarly, youth who have ever used cannabis was 47% [AHR = 1.47(95% CI:1.08 to 2.00)] more likely to develop anxiety symptoms at younger ages, compared to those who have never used cannabis.

Cohort 2 (12th Grade Through 3-Year Post-HS).

By age 22 years, the estimated probabilities for reporting anxiety symptoms among participants who never use cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 53.2%, 52.5%, and 53.7%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 60.3% 57.7%, and 58.3%, respectively. The largest increases in reporting anxiety symptoms among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis were between ages 20 and 21, years at 33.0%, 28.8%, and 29.0%, respectively. Youth who have ever used cigarettes and cannabis had a 52% [AHR = 1.52 (95% CI:1.13 to 2.05)], and 46% [AHR = 1.46 (95% CI:1.08 to 1.97)] increased risk of an earlier age of onset of anxiety symptoms compared to those who have never used cigarettes and cannabis, respectively (Table 3). However, there was no significant association between youth who have ever used e-cigarettes and those who have never used e-cigarettes and the age of onset of anxiety symptoms (Table 3).

Cohort 3 (2 Years Post-HS Through 5-Year Post-HS)

By age 23 years, the estimated probabilities for reporting anxiety symptoms among participants who never used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 42.5%, 43.6%, and 39.1%, respectively, while among participants who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis, were 53.0%, 50.7%, and 51.3%, respectively. In the unadjusted and adjusted analysis, there were no statistically significant differences in the age of reporting anxiety symptoms between youth who have ever used cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis versus those who have never used them.

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively assess differences in the age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms by lifetime substance use status for cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis by using survival analysis methods, which avoids recall bias. We found that lifetime or ever cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use increased risk of an earlier age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms. The youngest cohort in our study, which included those transitioning out of high school, was the most differentially impacted by substance use compared to the other older cohorts. These findings confirm and extend previous research that shows that substance use predicts the onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms among youth and young adults.15,20

The explanations for the positive association between tobacco or cannabis use and the early age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms are unclear; however, research shows that nicotine and cannabis disturb the same pathophysiological neurotransmitter systems that are disturbed in these mood symptoms and trigger an underlying predisposition to develop depressive and anxiety symptoms at an earlier age among substance users.8 This view is consistent with animal models showing that nicotine exposure in this critical and early period of brain development produces immediate and persistent changes in the noradrenergic and dopaminergic function that are likely to account for changes in behavior and mood later in life.21 It also could be explained as a misinterpretation, these depressive and anxiety symptoms can occur as withdrawal symptoms when users attempt to quit tobacco or cannabis use, moreover, research shows that repeated attempts to quit smoking can adversely affect mental health.22,23 The shared vulnerability model may also explain the relationship between substance use and the early age of onset of mood symptoms. In this model, a third variable or set of environmental, familial, or genetic variables, is assumed to predispose youth to the early onset of mental health symptoms among substance users.24,25

The strength of the association between substance use and the age of onset of mental health symptoms varied significantly among the three cohorts. Importantly, the youngest cohort (10th grade) is the most differentially impacted by substance use compared to the other older cohorts. These findings are supported by a previous study that shows that the probability of depressive symptoms was estimated to be four times greater among adolescents who smoked cigarettes, compared to those who did not smoke cigarettes and this association decreases with age and becomes nonsignificant by 17 years.26 The reasons for the cohort age effects on the association of tobacco or cannabis use and the age of onset of mood symptoms remain speculative. One possible explanation for this moderating effect is the existence of a risk window, during which individuals are especially vulnerable to both exposures. This interpretation is consistent with results of a recent meta-analysis that included 192 studies (n = 708 561), showing that the proportion of individuals with onset of any mental health disorders before the age of 18 years, was 48.4%, and peak age and median was approximately 15 and 18 years, respectively.27 Additionally, young adolescents tend to have lower executive control or self-regulation ability, therefore, they might have more difficulties achieving their goals and coping with peer pressure, which could lead to feelings of uneasiness and frustration that place them in a more vulnerable position to develop symptoms of depression and anxiety symptoms at an earlier age compared to older cohorts or young adults.28 Future research should explore this and other possible explanations, such as media exposure and social pressure among younger adolescents.

Our findings have important public health implications. Importantly, in our study, between ages 18–19 years in the 10th-grade cohort, between ages 20–21 years in the 12th-grade cohort, and between ages 22–23 years in the post-HS cohort, the estimated hazard function (or cumulative incidence) for reporting depressive and anxiety symptoms almost doubled among participants who have ever used cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis. Our findings suggest that prevention and educational efforts should target substance users for the onset of mental health symptoms before these sensitive time windows to optimize timely intervention, prevention, and promotion of good mental health opportunities. Moreover, the early identification of these predictors will provide an ideal moment to break the future cycle of psychopathology and subsequent substance disorders as well. Finally, since the results show that the youngest cohort is the most impacted by substance use and has a higher risk to develop depressive and anxiety symptoms at younger ages, this highlights the urgent need for early prevention and additional clinical screening for mental health problems among those individuals.

It should be noted that data for study were gathered during the COVID pandemic (2019–2021), when there was a significant increase in symptoms of anxiety and depression in the United States.29–31 One study including TATAMS youth conducted during the first year of the 2019 (coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) pandemic confirms the previous findings and shows modest increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety before to during the COVID-19 pandemic32 as well as the rates of tobacco and cannabis initiation.30 It is important to note that young adolescents have experienced more significant COVID-related stressors, including closure of schools, disrupted access to mental health services delivered in school, and reduced opportunities for cognitive and social development that impacted their mental health the most,33–35 and this could explain our findings that the youngest cohort was the most differentially impacted by substance use compared to the older cohorts in the current study. Therefore, it is plausible that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated mental health and substance use behaviors, which could impact our results, thus, there is a need for further research to replicate and confirm these findings after the context of the COVID pandemic.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths, foremost of which is the longitudinal design and use of survival analysis to prospectively estimate the differences in the age of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms among lifetime tobacco and cannabis users vs. nonusers. Furthermore, the study utilizes an ethnically diverse population-based sample, which is about 35% Hispanic. However, the findings in this study are subject to limitations. First, a diagnostic evaluation for depressive or anxiety was not conducted; however, clinically validated screening measures were used to assess these symptoms. Secondly, we did not include in our models some potential confounders such as other substance use, and peer influence. Thirdly, we did not examine tobacco use net cannabis use and vice versa; thus, the analyses are not based on mutually exclusive substance use patterns. Finally, given that the sample is from Texas, the findings might have limited generalizability.

Conclusion

The present longitudinal study provides the first evidence that lifetime tobacco and cannabis use predispose youth to earlier ages of onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms, especially among youth ages 18 years and younger. This highlights the need for timely mental health screenings among people who use nicotine and cannabis, which could have potentially significant implications for public health, clinical practice, and health policy.

Contributor Information

Bara S Bataineh, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Dallas, TX, USA.

Anna V Wilkinson, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin, TX, USA.

Aslesha Sumbe, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin, TX, USA.

Stephanie L Clendennen, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin, TX, USA.

Baojiang Chen, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin, TX, USA.

Sarah E Messiah, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Dallas, TX, USA; Center for Pediatric Population Health, UTHealth Houston School of Public Health, Dallas, TX, USA; Department of Pediatrics, McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX, USA.

Melissa B Harrell, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Austin, TX, USA.

Funding

This research was supported by the grant (R01-CA239097) from the National Cancer Institute. Role of Funder: The funding body had no role in the design and conduct of the study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH (NCI).

Declaration of Interest

Drs. Clendennen and Harrell serve as consultants in litigation involving the vaping industry. The other authors have no other potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

The data supporting this research are available from M. B. Harrell on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lucatch AM, Coles AS, Hill KP, George TP.. Cannabis and mood disorders. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5(3):336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yuan M, Cross SJ, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM.. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J Physiol. 2015;593(16):3397–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esmaeelzadeh S, Moraros J, Thorpe L, Bird Y.. Examining the association and directionality between mental health disorders and substance use among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. and Canada-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12):543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meier E, Hatsukami DK.. A review of the additive health risk of cannabis and tobacco co-use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166(1):6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joshi M, Joshi A, Bartter T.. Marijuana and the lung: evolving understandings. Med Clin North Am. 2022;106(6):1093–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipari RN, Van Horn SL.. Smoking and Mental Illness among Adults in the United States. 2017. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF.. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18(3):135–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiesbeck GA, Kuhl HC, Yaldizli O, Wurst FM; WHO/ISBRA Study Group on Biological State and Trait Markers of Alcohol Use and Dependence. WHO/ISBRA Study Group on Biological State and Trait Markers of Alcohol Use and Dependence. Tobacco smoking and depression--results from the WHO/ISBRA study. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57(1–2):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bataineh BS, Wilkinson AV, Case KR, et al.. Emotional symptoms and sensation seeking: implications for tobacco interventions for youth and young adults. Tob Prev Cessat. 2021;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slawecki CJ, Gilder A, Roth J, Ehlers CL.. Increased anxiety-like behavior in adult rats exposed to nicotine as adolescents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(2):355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iñiguez SD, Warren BL, Parise EM, et al.. Nicotine exposure during adolescence induces a depression-like state in adulthood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(6):1609–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, et al. The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction. 2013;108:124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lowe DJ, Sasiadek JD, Coles AS, George TP.. Cannabis and mental illness: a review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269(1):107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feingold D, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S.. Cannabis use and the course and outcome of major depressive disorder: a population based longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2017:251:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95(4):434–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pérez A, Harrell MB, Malkani RI, et al. Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance system’s design. Tob Reg Sci. 2017;3(2):151–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL.. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B.. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaasbøll C, Hagen R, Gråwe RW.. Population-based associations among cannabis use, anxiety, and depression in Norwegian adolescents. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2018;27:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Ali SF, Slotkin TA.. Adolescent nicotine exposure produces immediate and long-term changes in CNS noradrenergic and dopaminergic function. Brain Res. 2001;892(2):269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, et al. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F.. Depression and depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31(4):350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC.. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCaffery JM, Papandonatos GD, Stanton C, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Niaura R.. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in twins from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3S):S207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arnold EM, Greco E, Desmond K, Rotheram-Borus MJ.. When life is a drag: depressive symptoms associated with early adolescent smoking. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2014;9(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Papadakis AA, Prince RP, Jones NP, Strauman TJ.. Self-regulation, rumination, and vulnerability to depression in adolescent girls. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(3):815–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Indicators of Anxiety or Depression Based on Reported Frequency of Symptoms During the Last 7 Days. Household Pulse Survey. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clendennen SL, Chen B, Sumbe A, Harrell MB. Patterns in mental health symptomatology and cigarette, E-cigarette and Marijuana use among texas youth and young adults amid the COVID-19 Pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2022 Aug 26]. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023;25(2):266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clendennen SL, Case KR, Sumbe A, Mantey DS, Mason EJ, Harrell MB.. Stress, Dependence, and COVID-19-related changes in past 30-day marijuana, electronic cigarette, and cigarette use among youth and young adults. Tob Use Insights. 2021;14:1179173X211067439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore S-J.. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(8):634–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Viner R, Russell S, Saulle R, et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are available from M. B. Harrell on reasonable request.