Abstract

Background

Skin melanoma is one of the deadliest types of skin cancer and develops from melanocytes. The genetic aberrations in protein-coding genes are well characterized, but little is known about changes in non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) such as pseudogenes. Ribosomal protein pseudogenes (RPPs) have been described as the largest group of pseudogenes which are dispersed in the human genome.

Materials and methids

We looked deeply at the role of one of them, ribosomal protein L23a pseudogene 53 (RPL23AP53), and its potential diagnostic use. The expression level of RPL23AP53 was profiled in melanoma cell lines using real time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and analyzed based on the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data depending on BRAF status and clinicopathological parameters. Cellular phenotype, which was associated with RPL23AP53 levels, was described based on the REACTOME pathway browser, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis as well as Immune and ESTIMATE Scores.

Results

We indicted in vitro changes in RPL23AP53 level depending on a cell line, and based on in silico analysis of TCGA samples demonstrated significant differences in RPL23AP53 expression between primary and metastatic melanoma, as well as correlation between RPL23AP53 and overall survival. No differences depending on BRAF status were observed. RPL23AP53 is associated with several signaling pathways and cellular processes.

Conclusions

This study showed that patients with higher expression of RPL23AP53 displayed changed infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils compared to groups with lower expression of RPL23AP53. RPL23AP53 pseudogene is differently expressed in melanoma compared with normal tissue and its expression is associated with cellular proliferation. Thus, it may be considered as an indicator of patients’ survival and a marker for the immune profile assessment.

Keywords: RPL23AP53, pseudogene, non-coding RNA, lncRNA, TCGA, BRAF mutation, biomarkers, immunology

Introduction

Skin melanoma is one of the three main types of skin cancer along with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [1], and develops from melanocytes. Melanoma is often diagnosed in the advanced stage with metastasis to the small intestine, liver, lung, and brain tissues [2]. Its early diagnosis is still challenging. Molecular profiling could help to overcome this problem. Moreover, it allows for a personalized treatment [3]. The currently used therapeutic options could be divided into two main strategies: i) conventional treatment including surgical intervention and radio- or chemotherapy [4, 5], and ii) advanced therapy including several systemic and intratumoral approaches [6]. The treatment strategy depends on the clinical-pathological status and more often on molecular characteristics of patients [2].

Changes in the genome which are closely connected with ultraviolet radiation (UVA and UVB) emitted by the sun or artificial sources cause DNA damage by direct photodamage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and immune suppression which is the basis of the cancerogenesis [1]. The molecular mechanism of melanoma development is well known and mutations within KIT, NRAS, BRAF, GNAQ, and GNA11 genes are commonly detected [3]. Also, changes in the expression of suppressor genes like NF1, PTEN, and TP53 are indicated [3]. Moreover, the changes in RAC1, PREX2, MiTF, CDK4, and CDKN2A genes also play an important role in melanoma-specific signaling pathways and processes [1]. Based on the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data melanoma has been divided into four main molecular subgroups: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and Triple-WT (wild-type) [7].

The initiation and development of melanoma are a consequence of changes in genes and pathways which finally keep cells in an activated proliferation state and block their terminal differentiation ability [8].

Except for known changes in protein-coding genes, epigenetic modification in melanoma seems to be one of the key events in disease development. Several different non-coding RNAs take part in this process, including lncRNAs. LncRNAs function as regulators of transcription in the nucleus, as scaffolding proteins necessary for creating the transcriptional complexes and keeping their stability and activity, and function as competing endogenous RNAs interacting with miRNAs. That makes lncRNAs important elements of the regulation of cellular processes, including proliferation, cellular phenotype, metastasis ability, as well as response to pro- and anti-survival stimulus [9]. Similar to lncRNAs, but not the same, are pseudogenes. These transcripts interact with RNA, DNA, and protein molecules and are newly described elements of the epigenetic machinery. However, in contrast to the lncRNAs, their function and involvement in the cancerogenesis process are largely unknown, especially in the context of melanoma, which has been described by us previously [10]. The development of RNAseq techniques enables a deeper investigation of pseudogenes. One of the newly uncovered groups of pseudogenes are ribosomal protein pseudogenes (RPPs). It is estimated that about 2000 RPP transcripts can be found in the human transcriptome and it is thought to be the largest class of known pseudogenes [11, 12]. That constitutes a large number of transcripts in comparison to the 79 transcripts coding ribosomal proteins (RPs) in the human genome. Some of RPPs are not disturbed by stop codons or frame-shifts and can be mistaken as functional RPs’ genes. RPPs are distributed on a large scale in the whole genome and probably their location results from random insertions. Moreover, the number of pseudogenes is higher in the regions rich in GC-intermediate regions of the genome. Most of RP processed pseudogenes are located in the GC-poor regions [12]. RPP transcription depends on the tissue type and for some of them the level of RPPs is similar to the RP [11]. In contrast to the RPs, tissue-specific transcription of RPPs is most likely connected with biological processes [11], but it is not fully documented and understood. In contrast to pseudogenes, the RPs’ parental genes are well characterized. Some evidence indicated that disturbance in RPs expression had an important influence on cancer cell behavior. Ribosome biogenesis is altered during neoplastic transformation and growing evidence shows that translation of RPs is upregulated which causes the nucleolar/ribosomal stress and influences cell cycle and proliferation, maintenance of genome integrity, and DNA repair, apoptosis, autophagy, cell migration, invasion processes, and drug resistance [13, 14]. These proteins together with rRNAs are not only components of ribosomes for production of extra “cancer” proteins but also take part in the cellular regulation via eg. uL18 and uL5 adjusting the TP53 homeostasis [13]. Moreover, the 5S RNP-MDM2 pathway is implicated in cellular stress caused by chemotherapeutic drugs, and nutrient starvation, including hypoxia and oxidative stress, in response to over-suppressor and oncogenic transcription and replicative stress [15]. However, the function of RPPs remains unknown.

This work is focused on the biological role and diagnostic utility of ribosomal protein L23a pseudogene 53 (RPL23AP53). We engaged human primary epidermal melanocytes, melanoma cell lines, and TCGA data of melanoma patients to study its function in vitro and in silico. There is no information about ribosomal protein L23a pseudogene 53 in cancer biology, but some evidence exists that L23a protein is upregulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma. [16] and prostate cancer [17]. It should be emphasized that ribosomal protein L23a has 107 pseudogenes, whose function is not known and should be described [18].

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The mutation status of the BRAF gene in the cell lines was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ) cell culture databases and verified as described previously [19]. Cell lines used in the study were human adult and neonatal primary epidermal melanocytes: HEMa (ATCC® PCS-200-013) and HEMn (ATCC® PCS-200-012), respectively. Cells were cultured according to the ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia, United States) protocol whereas human melanoma cell lines MEWO, SKMEL28, WM115, WM266, WM9, and A549, were cultured as described previously [20].

qRT-PCR

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were performed as described previously [20]. Real time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using 2× concentrated SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) with specific primers to detect: RPL23AP53 (ENST00000521854) forward 5’-GAA GAT CCG CAT GTC ACT CA-3′ and reverse 5′-TGG TCA GCG GAA ACT TGA TA-3′ designed using The Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center online tool from Roche. All primers were verified using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). RT-PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) with the melting curve to discriminate between non-specific products. All real-time PCR data were analyzed by calculating the 2−ΔCT, normalizing against the GAPDH expression amplified using forward 5′-CCA CTC CTC CAC CTT TGA CG-3′ and reverse 5′-CCA CCA CCC TGT TGC TGT AG-3′ primers [21].

Data sets

The TCGA data of selected transcripts was downloaded from XenaBrowser University of California, Santa Cruz, cohort: TCGA Melanoma (SKCM), cBioportal [22], the University of ALabama at Birmingham CANcer (UALCAN) [23], and ENCORI [24] databases. For validation of RPL23AP53 expression levels, Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets were used: GSE8401 [25], GSE3189 [26], and GDS1989 [27]. All data from XenaBrowser and GEO is available online with unrestricted access which does not require any permission from the patient or institution.

Clinical-pathological data analysis

The expression levels of transcripts were analyzed depending on the clinicopathological parameters, such as: sample type (primary vs. metastasis), cancer type (cutaneous melanoma vs. other), cancer localization (extremities vs. trunk vs. regional lymph node vs. head and neck vs. distant metastasis vs. cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue vs. other), gender (women vs. men), age (< 58 vs. > 58), ulceration (absent vs. present), Clark level (I vs. II vs. III–IV vs. V), Breslow depth (< 1 vs. 1–2 vs. 2.1–4 vs. > 4), mitotic rate (0–2 vs. 2–3 vs. > 4), cancer stage (0 vs. I + II vs. III + IV), M-stage (M0 vs. M1), T-stage (T0 vs. T1 + T2 vs. T3 + T4), similarly as described previously [28]. Next, from a group of 472 patients, high-and low-expressing groups of RPL23AP53 were obtained using the quartile expression as a cutoff: low (< 25) and high (> 75). The expression level was analyzed in the group of all patients, as the median of RPL23AP53 and separately depending on BRAF status, with mutation (MUT) and wild type (WT). Progression-free interval (PFI) and overall survival (OS) were assessed in these subgroups, similarly as described previously [28].

Phenotype analysis

Positive (R ≥ 0.3) and negative (R ≤ −0.3) Pearson correlations for RPL23AP53 transcript with genes were downloaded from cBioPortal [22] and analyzed using REACTOME pathway analysis [p < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05] for distinguishing specific pathways and cellular processes. Functional enrichment analysis and prediction of gene function were performed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software version 3.0 (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). Melanoma patients were divided into two groups with high and low expression of selected transcripts by the mean of the expression level. The input file contained expression data for 20’530 genes and 565 patients. Gene set permutations with a parameter set as 1000 were used for the analysis. Pathways (hallmark gene sets (H) and collection from MSigDB) with nominal p-value ≤ 0.05 and FDR ≤ 0.25 were considered significant, similarly as described previously [29].

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Immune and ESTIMATE Scores (Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data) were downloaded from https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/estimate/disease.html and used to assess the infiltration of immune cells into tumor tissue and to infer tumor purity, as described previously [30]. Subpopulations of specific immune cells were estimated based on data presented by Thorsson et al. [31].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism9 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, United States). T-test, Mann-Whitney U test, or one-way ANOVA test were used depending on data normality estimated using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. The RFS and OS analyses were performed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests, respectively. All t-tests and ANOVA tests were performed as two-tailed and considered significant at p < 0.05, similarly as described previously [29].

Results

Expression of RPL23AP53 is changed in cell lines and melanoma patients

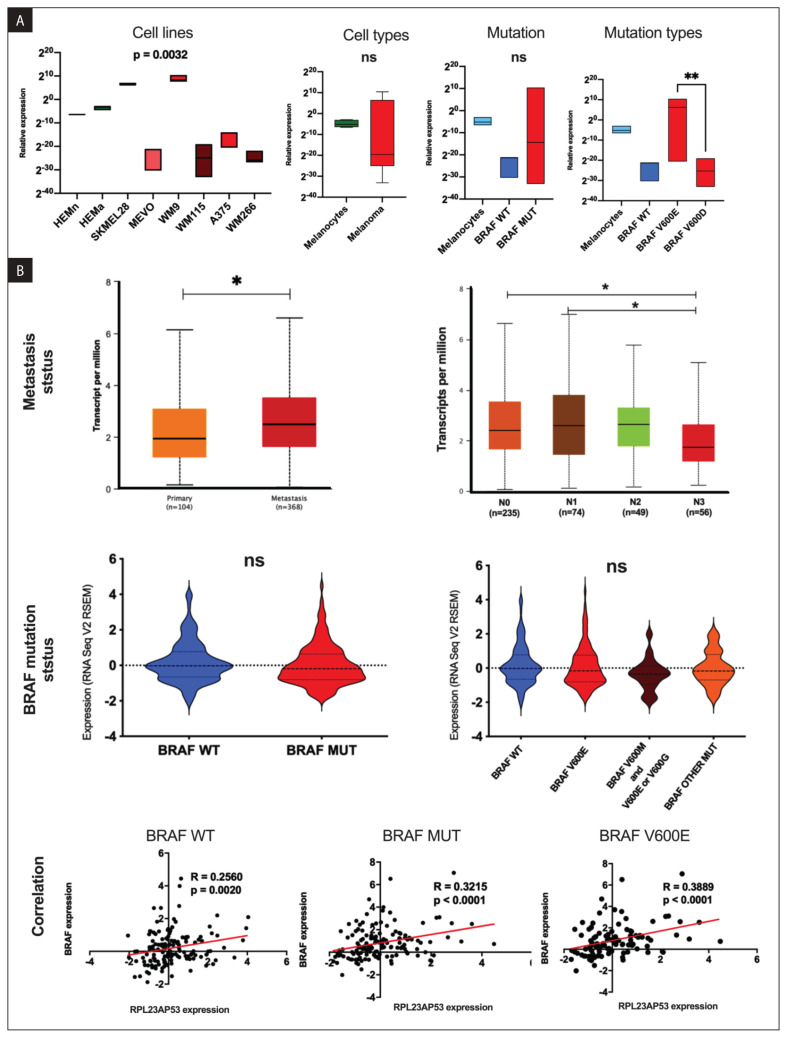

The expression level of ribosomal protein L23a pseudogene 53 was tested in normal melanocytes, melanoma cell lines, and the TCGA melanoma patients. No significant changes between melanoma and melanocytes were observed (0.05573 ± 0.01591 vs. 120.0 ± 76.82; p = 0.1314) for RPL23AP53. The specified melanoma cell lines displayed different RPL23AP53 levels (p = 0.0032), which was higher in cells with BRAF V600E than BRAF V600D mutation (240.1 ± 146.6 vs. 3.680e-007 ± 3.055e-007; p = 0.0028) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

The expression level of RPL23AP53 pseudogene in: melanocytes and melanoma cell lines: BRAF WT (MEVO), BRAF V600E (SKMEL28, WM9, and A549), and BRAF V600D (WM115 and WM266) (A), and melanoma patients from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database depending on metastasis status and regional nodal metastases status [graphs from the University of ALabama at Birmingham CANcer (UALCAN) database, modified], BRAF mutation status and BRAF expression level. BRAF wild type (WT), BRAF mutated (MUT) and BRAF V600E (c. 1799T>A) subgroups (B); T-test, one way ANOVA with Kruskal-Wallis test and Spearman correlation; solid lines in the boxplots and dashed lines in violin plots represent mean of expression; p < 0.05 considered as significant, ns - no significant, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Next, the RPL23AP53 pseudogene was analyzed using the TCGA data. It displayed significant differences in expression between primary and metastatic samples (0.229 vs. 0.599; p = 2.43 × 10−6 and 1.94 vs. 2.51; p = 0.0316, respectively), and downregulation of RPL23AP53 in N0 compared to N3 samples (2.403 vs. 1.755; p = 0.0250), as well as N1 vs. N3 (2.611 vs. 1.755; p = 0.0314). There were no significant differences in RPL23AP53 expression between the samples depending on the BRAF mutation status. However, when the correlation between the expression of RPL23AP53 and BRAF mRNA in BRAF WT, BRAF MUT, and BRAF V600E patient subgroups was analyzed, significant correlations between the expression of these transcripts in a group of BRAF WT (R = 0.2560, p = 0.0020), BRAF MUT (R = 0.3215, p < 0.0001) and BRAF V600E (R = 0.3889, p < 0.0001) were observed (Fig. 1B).

The expression of RPL23AP53 is independent of clinicopathological parameters

Next, the expression levels of RPL23AP53 regarding clinicopathological parameters were analyzed using the TCGA database. No significant differences (p > 0.05) in the expression levels of RPL23AP53 and gender, age, ulceration, Clark level, Breslow depth, mitotic rate, M-, T-stages, cancer type nor neoplasm disease stage were noticed (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

The expression levels of RPL23AP53 depending on clinicopathological parameters in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) melanoma patients; p < 0.05 considered as significant

| Parameter | Group | Cases | RPL23AP53 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | p-value | |||

| Gender | Male | 290 | 0.3804 ± 0.05149 | 0.2386 |

| Female | 178 | 0.3172 ± 0.06585 | ||

| Age | ≤ 58 | 236 | 0.344 ± 0.05770 | 0.6921 |

| > 58 | 227 | 0.3663 ± 0.05737 | ||

| Ulceration | Yes | 167 | 0.3449 ± 0.07375 | 0.3751 |

| No | 147 | 0.3088 ± 0.06253 | ||

| Clark level | I | 6 | −0.8354 ± 0.8310 | 0.2577 |

| II | 18 | 0.4998 ± 0.1706 | ||

| III | 78 | 0.4666 ± 0.06916 | ||

| IV | 167 | 0.3722 ± 0.06869 | ||

| V | 53 | 0.2564 ± 0.1158 | ||

| Breslow depth | < 1.0 | 51 | 0.3575 ± 0.08995 | 0.8240 |

| 1.0–2.0 | 88 | 0.406 ± 0.08832 | ||

| 2.1–4.0 | 78 | 0.4712 ± 0.07299 | ||

| > 4.0 | 143 | 0.3458 ± 0.08105 | ||

| Mitotic rate | <1 | 3 | 0.44 ± 0.6814 | 0.8363 |

| 1–4 | 65 | 0.369 ± 0.08878 | ||

| > 4 | 88 | 0.3793 ± 0.09413 | ||

| M Stage | M0 | 418 | 0.3572 ± 0.04292 | 0.8753 |

| M1 | 24 | 0.3756 ± 0.1354 | ||

| T Stage | T0 | 23 | 0.3326 ± 0.1736 | 0.5480 |

| T1–T2 | 121 | 0.3088 ± 0.07192 | ||

| T3–T4 | 244 | 0.383 ± 0.05653 | ||

| Cancer Type | Cutaneous melanoma | 69 | 0.3008 ± 0.1088 | 0.3570 |

| Desmoplastic melanoma | 3 | 0.826 ± 0.3703 | ||

| Melanoma | 28 | 0.1691 ± 0.1249 | ||

| Acral melanoma | 2 | 0.627 ± 0.4657 | ||

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 1 | 1.186 ± 0.0 | ||

| Neoplasm disease stage | 0 | 6 | −0.8765 ± 0.8283 | 0.1866 |

| I–II | 218 | 0.3859 ± 0.05387 | ||

| III–IV | 194 | 0.3584 ± 0.06433 | ||

SEM — standard error of the mean

A higher expression of RPL23AP53 is associated with better survival of melanoma patients

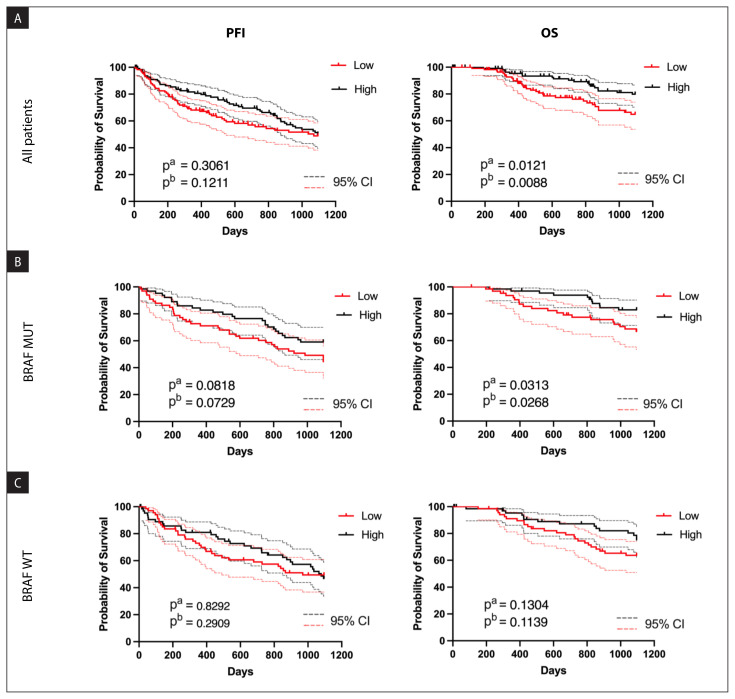

Next, melanoma patients were divided into groups with high and low RPL23AP53 expression, and progression-free survival (PFI) as well as overall survival (OS) were analyzed. Patients with higher RPL23AP53 expression showed slightly longer PFI (p = 0.1211 and p = 0.3061, respectively), while significantly longer OS (p = 0.0121 and p = 0.0088, respectively) (Fig. 2A). When patients were divided into BRAF MUT, no significant differences were observed in the case of PFI (p = 0.0818 and p = 0.0729) but patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 displayed longer survival time (OS) (p = 0.0313 and p = 0.0268) (Fig. 2B). No associations (p > 0.05) between PFI nor OS and expression levels of RPL23AP53 were observed in the group of patients with wild type BRAF gene (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Progression-free interval (PFI) and overall survival (OS) of melanoma patients depending on the RPL23AP53 expression levels in: group of all patients (A), patients with BRAF mutation (B) and patients with wild type of BRAF gene (C); results presented for 3 years of observation; low (red solid lines) and high (black solid lines) subgroups represent patients with 1st and 4th quartile of gene expression level for A panel and median expression level for panels B and C; pa — Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test; pb — Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test; 95% CI — 95% of confidence interval marked as dashed red and black lines; p < 0.05 considered as significant

A higher level of RPL23AP53 is associated with changes in essential signaling pathways

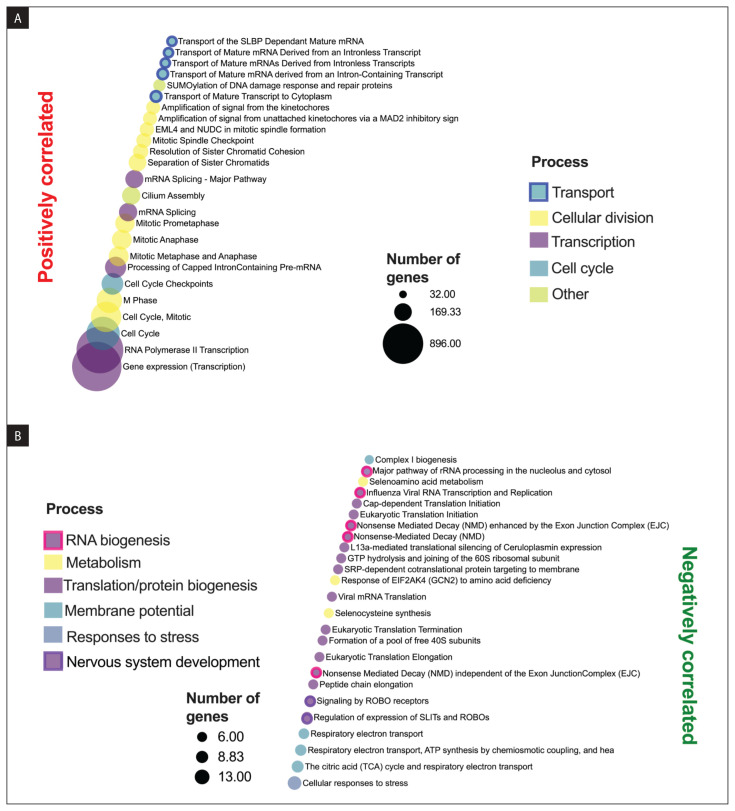

Next, positive (R ≥ 0.3) and negative (R ≤ −0.3) Pearson correlations of RPL23AP53 transcript with genes involved in selected cellular processes were analyzed using the REACTOME tool. RPL23AP53 was 5701 positively correlated with genes found in processes such as cell cycle and mitosis, RNA transcription, and metabolism, (p < 0.05). Only 68 genes were negatively correlated with RPL23AP53 and associated with electron transport, translation, cellular responses to stress, and viral processes (p < 0.05). All results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Genes correlated with RPL23AP53: positive (> 0.3) (A) and negative (< −0.3) (B) Pearson correlations of RPL23AP53 gene with genes and analyzed using REACTOME pathway analysis for distinguishing cellular pathways and processes. Only results with p < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were shown

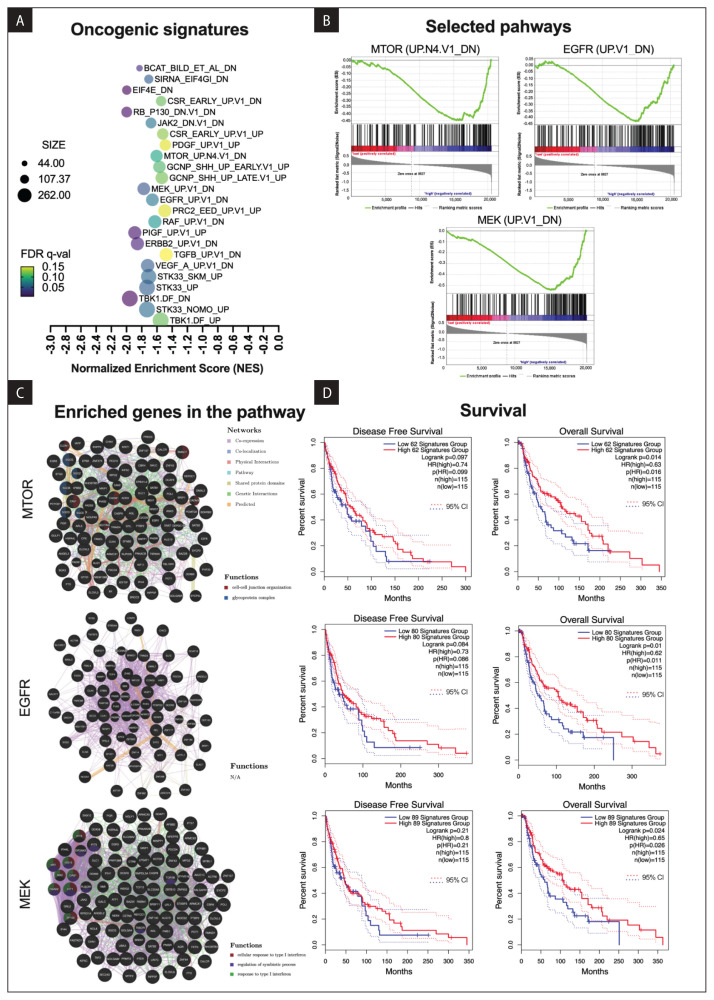

Next, the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis of patients with low and high expression of RPL23AP53 was performed. In the patients group with lower RPL23AP53 expression, changes were found in RB_P130_DN.V1_DN, EIF4E_DN, TBK1.DF_DN and TBK1.DF_UP, PIGF_UP.V1_UP, ERBB2_UP.V1_DN, MEK_UP.V1_DN (genes down-regulated in cells positive for ESR1 and stably overexpressing constitutively active MAP2K1), VEGF_A_UP.V1_DN, JAK2_DN.V1_DN, EGFR_UP.V1_DN (genes down-regulated in cells positive for ESR1 and express ligand-activatable EGFR), RAF_UP.V1_DN, and MTOR_UP.N4.V1_DN. All data are presented in Figure 4A. Based on the GSEA results signaling pathways connected with melanoma, such as MTOR, EGFR and MEK, were chosen for further investigation (Fig. 4B). In the MTOR pathway, 62 genes were observed as enriched and involved in cell-cell junction organization (6 genes) and glycoprotein complex (5 genes) as well as other processes. For 80 genes from the EGFR pathway, no association with any processes was indicated. In the case of the MEK pathway, 89 genes were associated with the regulation of a cellular response to type I interferon (8 genes), regulation of symbiotic process (10 genes), response to type I interferon (8 genes), and response to the viral infection (Fig. 4C). Next, the patients’ disease free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) depending on the expression levels of genes indicated in GSEA analysis and connected with melanoma were analyzed. Significantly longer overall survival times of patients with higher levels of MTOR (p = 0.014), EGFR (p = 0.01), and MEK (p = 0.024) genes were observed. No differences (p < 0.05) were indicated in the disease-free survival (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

The phenotype associated with low or high expression levels of RPL23AP53 in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) melanoma patients based on Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results. A. Changed molecular pathways in patients with lower expression of RPL23AP53; B. selected for melanoma MTOR, MEK, and EGFR; C. Involvement in cellular processes based on the GENEmania analysis tool; D. Association of genes from MTOR, MEK and EGFR pathways with disease-free survival and overall survival based on Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA2) database analysis; red and blue solid lines represent the group of patients with high and with low expression level of selected genes from the pathway, respectively; 95% CI — 95% of confidence interval marked as dashed red and blue lines; NES — normalized enrichment score; p-val — nominal p-value), FDR q-value — false discovery rate); only results set with p ≤ 0.05 and FDR ≤ 0.25 are shown; p < 0.05 considered as statistically significant

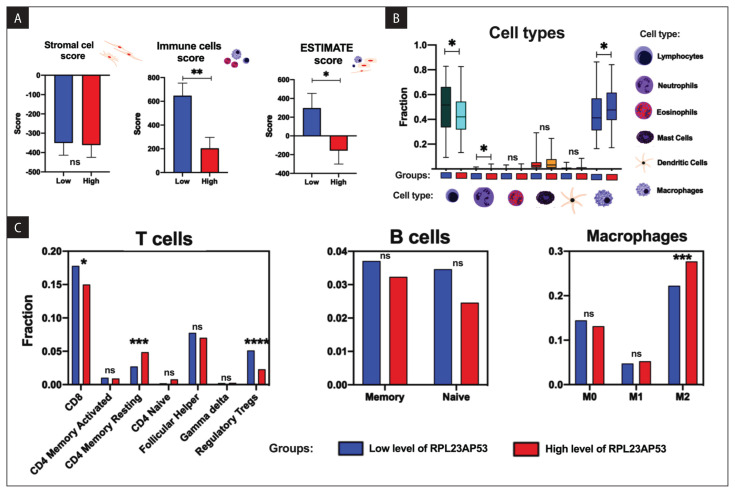

RPL23AP53 expression is correlated with the immune profile of melanoma patients

Significant differences between higher and lower levels of RPL23AP53 and the immune and ESTIMATE scores (p = 0.0483 and p = 0.0030, respectively) were found and no differences in the stromal cells and levels of RPL23AP53 (p > 0.05) were observed (Fig. 5A). Patients with higher expression of RPL23AP53 displayed a lower fraction of lymphocytes (p = 0.0108) and higher fraction of macrophages (p = 0.0146), and the population of neutrophils was raised (p = 0.0158) (Fig. 5B). In the case of higher expression of RPL23AP53, lower expression of CD8 T cells and higher CD4 memory resting (p = 0.0367 and p = 0.0009, respectively) as well as lower expression of regulatory Tregs (p < 0.0001), and significantly higher infiltration of macrophages M2 (p = 0.0004) were observed; no differences in B cell lymphocytes (p > 0.05) in patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 were indicated (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Association of the immunological profile of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) melanoma patients with the expression levels of RPL23AP53: A. ESTIMATE, immune cells, and stromal cells scores; B. differences of lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages; C. The fraction of specific subpopulation of T cells, B cells, and macrophages depending on the low and high expression levels of RPL23AP53; T-test or Mann Whitney test, p < 0.05 considered as significant; ns — non significant; *p < 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001

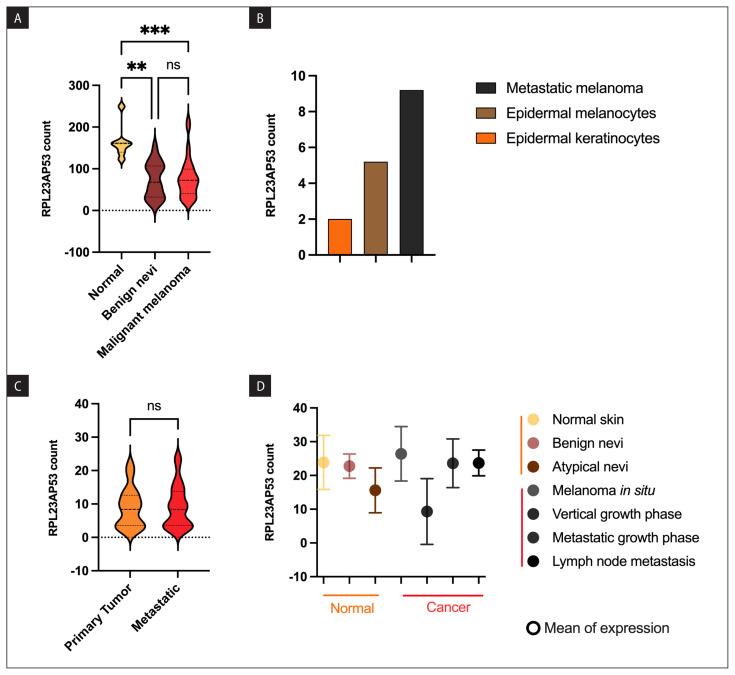

Expression levels of RPL23AP53 differ depending on the type of melanoma samples

Next, the expression levels of RPL23AP53 in patients’ samples and cell lines were validated using available data from GEO. First, based on the data from a study made by Talantov et al. (data set GSE3189) it was observed that the expression level of RPL23AP53 is significantly lower in benign nevi and malignant melanomas in comparison to normal samples (73.51 ± 9.971 vs. 77.45 ± 7.209 vs. 164.1 ± 15.21, p = 0.0019 and p = 0.0007, respectively). Surprisingly, no differences were observed between nevus and melanoma (p > 0.9999) (Fig. 6A). Using expression data from cell lines (GDS1989), RPL23AP53 expression was higher in a metastatic melanoma cell line (value = 9.2) than in epidermal melanocytes (value = 2) and keratinocytes (value = 5.2), but those data lack replicates for statistical analysis (Fig. 6B). However, based on the other data set (GSE8401) no differences were indicated between primary and metastatic melanomas (8.952 ± 1.066 vs. 9.282 ± 0.8906, p = 0.8405) (Fig. 6C). Smith et al. presented also data from different normal and cancer samples, where expression levels of RPL23AP53 depended on the various histological types of samples. Estimated samples included normal skin (23.85 ± 5.65), benign nevi (22.75 ± 2.55), atypical nevi (15.60 ± 4.70) and melanoma in situ (26.40 ± 5.70), vertical (9.30 ± 6.90), and metastatic (23.60 ± 5.10) growth phases, lymph node metastasis (23.70 ± 2.21) (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Validation of RPL23AP53 expression levels using data from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). A. Differences in expression in normal, benign nevi, and malignant melanoma samples based on GSE3189, One way Anova with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test; B. Expression in epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes compared to metastatic melanoma cell lines (GSE3189), only one replicates included in data set per sample type; C. Expression levels based on primary tumor and metastatic samples from GSE8401, Mann Whitney test; D. Comparison of normal (normal skin, benign nevi, atypical nevi) and cancer (melanoma in situ, vertical and metastatic growth phases, lymph node metastasis) samples in GDS1989 data set, dots represent mean of value, only two replicates available per sample type; dashed lines in violin plots represent mean of expression; p < 0.05 considered as significant; ns — non significant, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001

Discussion

It is the first report, where the biological role and diagnostic utility of ribosomal protein L23a pseudogene 53 (RPL23AP53) were studied based on human primary epidermal melanocytes and melanoma cell lines as well as melanoma patients using the TCGA data. RPL23AP53 pseudogene is dysregulated in specified melanoma cell lines and in melanoma patients’ metastatic tissue. However, its expression seems to depend on the cell line or tissue features, and can be either upregulated or downregulated. In melanoma samples lower expression of this pseudogene correlates with more advanced stages and lymph node metastases. The BRAF mutation status is known to be an important marker in melanoma, and the gene is mutated in approximately 50% of melanoma patients. We investigated the association of RPL23AP53 with BRAF mutation and observed increased expression of RPL23AP53 in BRAF V600E mutated cell lines but not in the TCGA patients. However, the expression levels of RPL23AP53 positively correlated with BRAF expression in the group of patients without mutation in BRAF gene, but especially in the group with mutated forms of BRAF gene. However, patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 displayed better survival rates than those with lower expression of this pseudogene. One of the reasons is the probable connection of RPL23AP53 with proliferating cancers. It should be noted that one of the futures of cancer stem cells is a slow proliferation ratio and high self-renewing capacity [32]. Moreover, the cells with features of cancer stem cells are resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and they are most likely responsible for metastasis [33, 34]. Fattore et al. discovered the molecular pathways characteristic of slow-cycling melanoma stem cells. They identified 25 genes and divided them into four groups: i) kinases and metabolic genes, ii) melanoma-associated proteins, iii) Hippo pathway, and iv) slow cycling/CSCs factors [35]. In our work we indicated that melanoma patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 are correlated with transcription, cell cycle, RNA maturation and mitosis. Moreover, based on the GSEA analysis, we observed that patients with lower levels of RPL23AP53 displayed upregulation of MTOR, EGFR and MEK pathways. It is known that the MTOR signaling is crucial for melanoma pathogenesis and, at the same time, is a modulator of cancer stem cells [36]. The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) has been described as an essential receptor tyrosine kinase-regulator of cancer stem cells and modulation of this pathway could be used for radiotherapy due to involvement of EGFR pathway in DNA repair process [37]. The MEK pathway is frequently activated in melanomas and many different inhibitors of this pathway are used; however, it is characterized by de novo and acquired resistance which leads to cancer stem cells division and cancer progression [38].

Smith et al. based on gene expression profiling of different stages of melanoma development indicated that genes involved in mitotic cell cycle regulation and cell proliferation were the two main groups of genes engaged in melanoma progression [27]. They observed that nevus constituted of non-dividing cells and in situ melanomas are characterized by comparatively low mitotic/proliferation ratios. In contrast, cells in the vertical and metastatic growth phases aggressively divide [27]. However, it should be emphasized that changes in some genes characterized for metastatic melanomas can also be observed in nevus, which reflects the underlying complexity of transcriptome changes during cancer progression [27]. Hust et al. observed that vertically growing melanomas are highly tumorigenic and metastatic, and cells are expansive with their anchorage-independent growth ability [39]. Interestingly, we observed that the expression level of RPL23AP53 is the lowest in vertical growth phase melanomas compared to pre-malignant and advanced melanoma stages. We suppose, based on the results presented here, that the expression level of RPL23AP53, and probably other ribosomal protein pseudogenes, is negatively correlated with cancer stem cells content in melanoma. However, this hypothesis needs to be experimentally verified.

It should be noted that RPL23AP53 pseudogene and its role, especially in cancer, has not been described previously. Balasubramanian et al. reported a large-scale comparative analysis of ribosomal protein pseudogenes in four mammalian genomes and observed that all of them contain large numbers of ribosomal protein pseudogenes assessed between 1’400 to 2’800 transcripts. Moreover, most of the pseudogenes originated from independent lineage-specific retro-transposition activities taking place in the genomes [34]. It has been indicated that in humans, ribosomal protein pseudogenes are constitutively but differentially expressed in almost all tissues in contrast to genes encoding ribosomal proteins. These transcripts could participate in biological processes in a tissue-specific way [11]. Some studies indicated the disturbance of ribosomal protein pseudogenes in cancer, such as RPSAP52 in pituitary adenomas, which regulates p21Waf1/CIP expression by interacting with the RNA binding protein HuR [40]. Wang et al., based on the TCGA data and patients’ samples, indicated that RPSAP52 is upregulated in glioblastoma and its high expression predicted poor survival. In vitro model showed that RPSAP52 upregulates TGF-β1 and causes higher cancer stemness [41]. Ribosomal protein L23A (rpL23A), also known as melanoma differentiation-associated gene (mda-20), was reduced in human cells including melanoma cells treated with human leukocyte (IFN-α) and immune (IFN-γ) interferons, but not by growth inhibition resulting from serum starvation. It has been shown that the expression of rpL23A was necessary for cell growth [42]. Kondo et al. observed that S8, L12, L23a, L27, and L30 ribosomal protein mRNAs are upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma compared to adjacent normal tissues and are important for cancer development [16]. In addition, the expression level of rpL23A was upregulated in cancer compared to normal and hyperplasia cells [17].

It should be strongly emphasized that knowledge related to lncRNA and, especially, pseudogene transcripts in melanoma is very limited. Guo et al. identified seven pseudogenes, SRP9P1, RP4-800G7.1, CH17-264B6.3, C1DP1, MTND4P12, LDHAP3, and RP11-359E7.3 as upregulated, based on the TCGA data [43]. Moreover, there are no studies on pseudogene transcript alteration depending on the BRAF gene status in melanoma. Only few studies have focused on lncRNAs and BRAF gene, and they examined BRAF-activated non-coding RNA (BANCR) and RMEL 1, 2, and 3 [44, 45].

Finally, we checked whether the expression level of RPL23AP53 pseudogene is connected with the infiltration of immune cells in patients’ samples. Our results indicated that patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 pseudogenes present distinct immunological profiles. Our results also indicated that patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 had a lower fraction of CD8+ T cells and higher levels of neutrophils. Yang et al. based on the TCGA data calculated the immune and stromal scores using the ESTIMATE algorithm and the abundance of six infiltrating immune cells using the TIMER algorithm in melanoma patients. They observed that the prognosis of the patients with higher numbers of CD8+ T cells and neutrophils was better [46]. Better patients’ survival for patients with higher expression of RPL23AP53 could be associated with a higher level of T cell CD4 memory resting and a higher level of neutrophils. However, we also observed that patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53 displayed lower levels of Treg T cells. It was observed that Tregs are frequently infiltrated into melanoma and the CD8+ T and Treg cells ratio is the predictive indicator for patient survival. Moreover, depletion of Tregs seems to be a promising strategy in melanoma treatment [47]. We also observed a change in M2 macrophages levels which were up-regulated in the group of patients with higher levels of RPL23AP53. It is known that two types of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) can be distinguished: M1 responsible for activation of the adaptive immune system and M2 which are described as pro-tumor [48]. As in the case of Tregs, estimation of M2 macrophages can be used for future therapeutic strategies [48].

Conclusion

This is the first study demonstrating the association of RPL23AP53 pseudogene with melanoma, better survival rates and favorable immune profiles. However, the exact role of ribosomal pseudogenes is not understood. They could potentially regulate the expression levels of selected miRNAs and act as molecular sponge [49]. More studies need to be conducted to indicate the biological role of both ribosomal protein L23A and RPL23AP53 pseudogene.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available online from the XenaBrowser University of California, Santa Cruz, cohort: TCGA Melanoma (SKCM), cBioportal, UALCAN, ENCORI, and GEO databases, or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thanks the Greater Poland Cancer Center for supporting our work and providing a fully equipped laboratory to perform the necessary analyses.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Authors’ individual contributions: conceptualization — T.K.; methodology — T.K.; investigation — T.K., K.G., P.P., J.K.M., A.B.; data curation — T.K., K.G., P.P., J.K.M.; writing — original draft preparation: T.K., P.P.; writing — review and editing: T.K., U.K., A.T.; visualization — T.K.; supervision — A.T.; funding acquisition — A.T., K.G. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. The use of the data does not violate the rights of any person or any institution.

Funding

This work was supported by the Greater Poland Cancer Center grant no.: 1/2023(263), 13/01/2023/PGN/WCO/001; Alicja Braska received “The best in nature 2.0. The integrated program of the Poznań University of Life Sciences” program scholarship at the time of writing this manuscript from the University of Life Sciences in Poznań; Joanna Kozłowska-Masłoń received a PhD program scholarship at the time of writing this manuscript from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan; Kacper Guglas received a scholarship at the time of writing this manuscript from the European Union POWER PhD program and from Medical University of Warsaw.

Ethics approval

All data is available online, access is unrestricted and does not require the patient’s consent or other permissions. The use of the data does not violate the rights of any person or any institution.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Liu-Smith F, Jia J, Zheng Y. UV-Induced Molecular Signaling Differences in Melanoma and Non-melanoma Skin Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;996:27–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56017-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naik PP. Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma: A Review of Early Diagnosis and Management. World J Oncol. 2021;12(1):7–19. doi: 10.14740/wjon1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scatena C, Murtas D, Tomei S. Cutaneous Melanoma Classification: The Importance of High-Throughput Genomic Technologies. Front Oncol. 2021;11:635488. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.635488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis LE, Shalin SC, Tackett AJ. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(11):1366–1379. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1640032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabestani PJ, Dawson AJ, Neumeister MW, et al. Radiation Therapy for Local Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin Plast Surg. 2021;48(4):643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasakovski D, Skrygan M, Gambichler T, et al. Advances in Targeting Cutaneous Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(9) doi: 10.3390/cancers13092090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell. 2015;161(7):1681–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darp R, Ceol C. Making a melanoma: Molecular and cellular changes underlying melanoma initiation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34(2):280–287. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wozniak M, Czyz M. The Functional Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(19) doi: 10.3390/cancers13194848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stasiak M, Kolenda T, Kozłowska-Masłoń J, et al. The World of Pseudogenes: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Targets in Cancers or Still Mystery Molecules? Life (Basel) 2021;11(12) doi: 10.3390/life11121354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonner P, Srinivasasainagendra V, Zhang S, et al. Detecting transcription of ribosomal protein pseudogenes in diverse human tissues from RNA-seq data. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:412. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Harrison P, Gerstein M. Identification and analysis of over 2000 ribosomal protein pseudogenes in the human genome. Genome Res. 2002;12(10):1466–1482. doi: 10.1101/gr.331902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pecoraro A, Pagano M, Russo G, et al. Ribosome Biogenesis and Cancer: Overview on Ribosomal Proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11) doi: 10.3390/ijms22115496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penzo M, Montanaro L, Treré D, et al. The Ribosome Biogenesis-Cancer Connection. Cells. 2019;8(1) doi: 10.3390/cells8010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura K, Kumazawa T, Kuroda T, et al. Perturbation of ribosome biogenesis drives cells into senescence through 5S RNP-mediated p53 activation. Cell Rep. 2015;10(8):1310–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondoh N, Shuda M, Tanaka K, et al. Enhanced expression of S8, L12, L23a, L27 and L30 ribosomal protein mRNAs in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(4A):2429–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaarala M, Porvari K, Kyllönen A, et al. Several genes encoding ribosomal proteins are over-expressed in prostate-cancer cell lines: Confirmation of L7a and L37 over-expression in prostate-cancer tissue samples. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(1):27–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980925)78:1<27::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GeneCards. The human gene database. [7 March 2022]. https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=RPL23A .

- 19.Mackiewicz-Wysocka M, Czerwińska P, Filas V, et al. Oncogenic BRAF mutations and p16 expression in melanocytic nevi and melanoma in the Polish population. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34(5):490–498. doi: 10.5114/ada.2017.71119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Czerwinska P, Jaworska AM, Wlodarczyk NA, et al. Melanoma Stem Cell-Like Phenotype and Significant Suppression of Immune Response within a Tumor Are Regulated by TRIM28 Protein. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(10) doi: 10.3390/cancers12102998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paszkowska A, Kolenda T, Guglas K, et al. C10orf55, CASC2, and SFTA1P lncRNAs Are Potential Biomarkers to Assess Radiation Therapy Response in Head and Neck Cancers. J Pers Med. 2022;12(10) doi: 10.3390/jpm12101696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SA, et al. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, et al. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu L, Shen SS, Hoshida Y, et al. Gene expression changes in an animal melanoma model correlate with aggressiveness of human melanoma metastases. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(5):760–769. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talantov D, Mazumder A, Yu JX, et al. Novel genes associated with malignant melanoma but not benign melanocytic lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(20):7234–7242. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith AP, Hoek K, Becker D. Whole-genome expression profiling of the melanoma progression pathway reveals marked molecular differences between nevi/melanoma in situ and advanced-stage melanomas. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(9):1018–1029. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.9.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazimierczak U, Kolenda T, Kowalczyk D, et al. BNIP3L Is a New Autophagy Related Prognostic Biomarker for Melanoma Patients Treated With AGI-101H. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3723–3732. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomaszewska W, Kozłowska-Masłoń J, Baranowski D, et al. Influences HNSCC Development and Progression through Regulation of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Process and Could Be Used as a Potential Biomarker. Biomedicines. 2021;9(12) doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9121894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koteluk O, Bielicka A, Lemańska Ż, et al. The Landscape of Transmembrane Protein Family Members in Head and Neck Cancers: Their Biological Role and Diagnostic Utility. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(19) doi: 10.3390/cancers13194737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity. 2018;48(4):812–830e14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerer RM, Korn P, Demougin P, et al. Functional features of cancer stem cells in melanoma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13(1):78. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolenda T, Przybyła W, Kapałczyńska M, et al. Tumor microenvironment - Unknown niche with powerful therapeutic potential. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2018;23(3):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czerwińska P, Mazurek S, Wiznerowicz M. Application of induced pluripotency in cancer studies. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2018;23(3):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fattore L, Mancini R, Ciliberto G. Cancer Stem Cells and the Slow Cycling Phenotype: How to Cut the Gordian Knot Driving Resistance to Therapy in Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(11) doi: 10.3390/cancers12113368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L, Shi P, Zhao G, et al. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0110-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talukdar S, Emdad L, Das SK, et al. EGFR: An essential receptor tyrosine kinase-regulator of cancer stem cells. Adv Cancer Res. 2020;147:161–188. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang AX, Qi XY. Targeting RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling in metastatic melanoma. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(9):748–758. doi: 10.1002/iub.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu MY, Meier F, Herlyn M. Melanoma development and progression: a conspiracy between tumor and host. Differentiation. 2002;70(9–10):522–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Angelo D, Arra C, Fusco A. RPSAP52 lncRNA Inhibits p21Waf1/CIP Expression by Interacting With the RNA Binding Protein HuR. Oncol Res. 2020;28(2):191–201. doi: 10.3727/096504019X15761465603129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Guo X, Lv W, et al. LncRNA RPSAP52 Upregulates TGF-β1 to Increase Cancer Cell Stemness and Predict Postoperative Survival in Glioblastoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:2541–2547. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S227496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang H, Lin JJ, Tao J, et al. Suppression of human ribosomal protein L23A expression during cell growth inhibition by interferon-beta. Oncogene. 1997;14(4):473–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Y, Wei Q, Tan L, et al. Inhibition of AURKB, regulated by pseudogene MTND4P12, confers synthetic lethality to PARP inhibition in skin cutaneous melanoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(10):3458–3474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussen BM, Azimi T, Abak A, et al. Role of lncRNA BANCR in Human Cancers: An Updated Review. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:689992. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.689992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sousa JF, Torrieri R, Silva RR, et al. Novel primate-specific genes, RMEL 1, 2 and 3, with highly restricted expression in melanoma, assessed by new data mining tool. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang S, Liu T, Nan H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of prognostic immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of cutaneous melanoma. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(2):1025–1035. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang L, Guo Y, Liu S, et al. Targeting regulatory T cells for immunotherapy in melanoma. Mol Biomed. 2021;2(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s43556-021-00038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolenda T, Guglas K, Kopczyńska M, et al. Quantification of long non-coding RNAs using qRT-PCR: comparison of different cDNA synthesis methods and RNA stability. Arch Med Sci. 2021;17(4):1006–1015. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2019.82639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available online from the XenaBrowser University of California, Santa Cruz, cohort: TCGA Melanoma (SKCM), cBioportal, UALCAN, ENCORI, and GEO databases, or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.