Abstract

Objective:

To assess an alternative method for estimating demand for postpartum tubal ligation and evaluate reproductive trajectories of low-income women who did not obtain a desired procedure.

Study design:

In a 2-year cohort study of 1700 publicly insured women who delivered at 8 hospitals in Texas, we identified those who had an unmet demand for tubal ligation prior to discharge from the hospital. We classified unmet demand as explicit or prompted based on survey questions that included a prompt regarding whether the respondent would like to have had a tubal ligation at the time of delivery. We assessed persistence of demand for permanent contraception, contraceptive use, and repeat pregnancies among all study participants who wanted but did not get a postpartum procedure.

Results:

Some 426 women desired a postpartum tubal ligation; 219 (51%) obtained one prior to discharge. Among the 207 participants with unmet demand, 62 (30%) expressed an explicit preference for the procedure, while 145 (70%) were identified from the prompt. Most with unmet demand still wanted permanent contraception 3 months after delivery (156/184), but only 23 had obtained interval procedures. By 18 months, the probability of a woman with unmet demand conceiving a pregnancy that she would likely carry to term was 12.5% (95% CI: 8.3%–18.5%).

Conclusions:

The majority of unmet demand for postpartum tubal ligation among publicly insured women in Texas was uncovered via a prompt and would not have been evident in clinical records or from consent forms. Women unable to obtain a desired procedure had a substantial chance of pregnancy within 18 months after delivery.

Implications:

Estimates of unmet demand for postpartum tubal ligation based on clinical records and consent forms likely underestimate desire for permanent contraception. Among low-income women in Texas, those with unmet demand for postpartum tubal ligation require improved access to effective contraception.

Keywords: Contraception, Family planning, Female sterilization, Sterilization, Texas, Tubal ligation, Permanent contraception, Postpartum

1. Introduction

Tubal ligation follows about 10% of all US deliveries, and the frequency is much higher following cesarean as compared to vaginal births [ 1, 2 ]. Despite the United States having higher rates of postpartum sterilization than other industrialized countries [1–3], there is evidence that many women who desire the procedure do not obtain it after delivery prior to hospital discharge. Studies conducted in a variety of hospital settings have shown that 31% to 48% of requests for postpartum tubal ligation are not met [4–12]. Barriers preventing women from obtaining the procedure include problems with the Medicaid consent form, lack of availability of an operating room, and lack of insurance coverage or other funding [13, 14].

Unmet demand for postpartum tubal ligation is typically assessed by comparing tubal ligation requests or signed consent forms with records of procedures performed, often through retrospective chart review of clinical documentation. A limitation of this approach is that it leaves out demand for permanent contraception among patients who did not complete the consent form because they lacked coverage for the procedure, or whose provider was unwilling to provide permanent contraception because of their age, parity, or other reason.

In the present analysis, our focus is on identifying this missing demand. We use a prospective survey of postpartum women in Texas to assess demand for tubal ligation through interviews conducted in the hospital following delivery and by telephone 3 months after delivery. We rely on both a prospective question about the method of contraception respondents would like to be using 6 months after delivery and a retrospective question asking them whether they would like to have had their tubes tied right after having their baby. We compare the respondents identified by each question and then ascertain barriers encountered as well as persistence of demand in each group. Additionally, we assess contraceptive and reproductive trajectories for 2 years following delivery among all who did not obtain a desired procedure before discharge.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study participants and design

In 2014, we began a prospective cohort study of 1700 women who gave birth in 8 hospitals across 6 Texas cities. Three hospitals were privately owned, and 5 were teaching hospitals. Women who were covered by public insurance (Medicaid or CHIP-Perinate) or had no insurance for their delivery were recruited following delivery and prior to hospital discharge. Participants were eligible if they were 18 to 44 years of age, spoke English or Spanish, wanted to delay childbearing for at least 2 years, delivered a single, healthy baby whom they expected to take home upon discharge, lived in Texas within the hospital’s service area, and planned to live in the area for at least 1 year. Additional details regarding the sample are provided elsewhere [15].

Data collection for each hospital sample continued over 2 years, with follow-up phone interviews conducted at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after delivery. Data collection was completed in April 2018 with a final retention rate of 79.4% at 24 months.

At baseline, after obtaining informed consent from participants, bilingual interviewers conducted a private 20-minute, face-to-face interview in English or Spanish in the hospital prior to discharge. The baseline questionnaire collected demographic and socioeconomic information, as well as type of delivery, site of prenatal care, insurance status, plans for future childbearing, tubal ligation status, and contraceptive plans and preferences. To determine method preference, we asked about the contraceptive method the participant would like to be using 6 months after delivery. If the participant had already had a tubal ligation or had been counseled during prenatal care about permanent contraception, she was asked if and when she had signed a consent form.

To determine whether a participant desired a tubal ligation before discharge, we asked nonsterilized women who said they would like to have a tubal ligation by 6 months if they planned to have the procedure before leaving the hospital, and, if not, whether they would like to have had the procedure right after delivery. Because some women who desire tubal ligation may perceive the method as inaccessible and not declare a preference for it, we asked all other nonsterilized women who wanted no more children, regardless of their preferred method: “Would you have liked to have had your tubes tied right after you had your baby?”

At the 3-month interview, we asked participants who had not had a tubal ligation at the baseline interview if they had the procedure in the hospital after giving birth to identify any postpartum procedures that occurred following the baseline interview, but before discharge. In this interview, we also asked those unable to obtain a desired postpartum procedure about barriers they encountered. Women were able to name more than one barrier in their response. Participants who wanted no more children were again asked whether they would like to have had a tubal ligation right after delivery.

At each follow-up interview, we asked participants if they were currently using birth control and, if so, which method. We also asked about the method of contraception they would like to be using. Finally, we asked if they had become pregnant since the previous interview, and, if so, the duration, outcome, and intention status of the pregnancy.

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of The University of Texas at Austin and each participating hospital.

2.2. Data analysis

For this analysis, we excluded all participants who said they wanted to have another child in the future (n = 509). We also excluded those younger than 21 years of age (n = 299) because current Medicaid policy does not reimburse for tubal ligations for women under age 21.

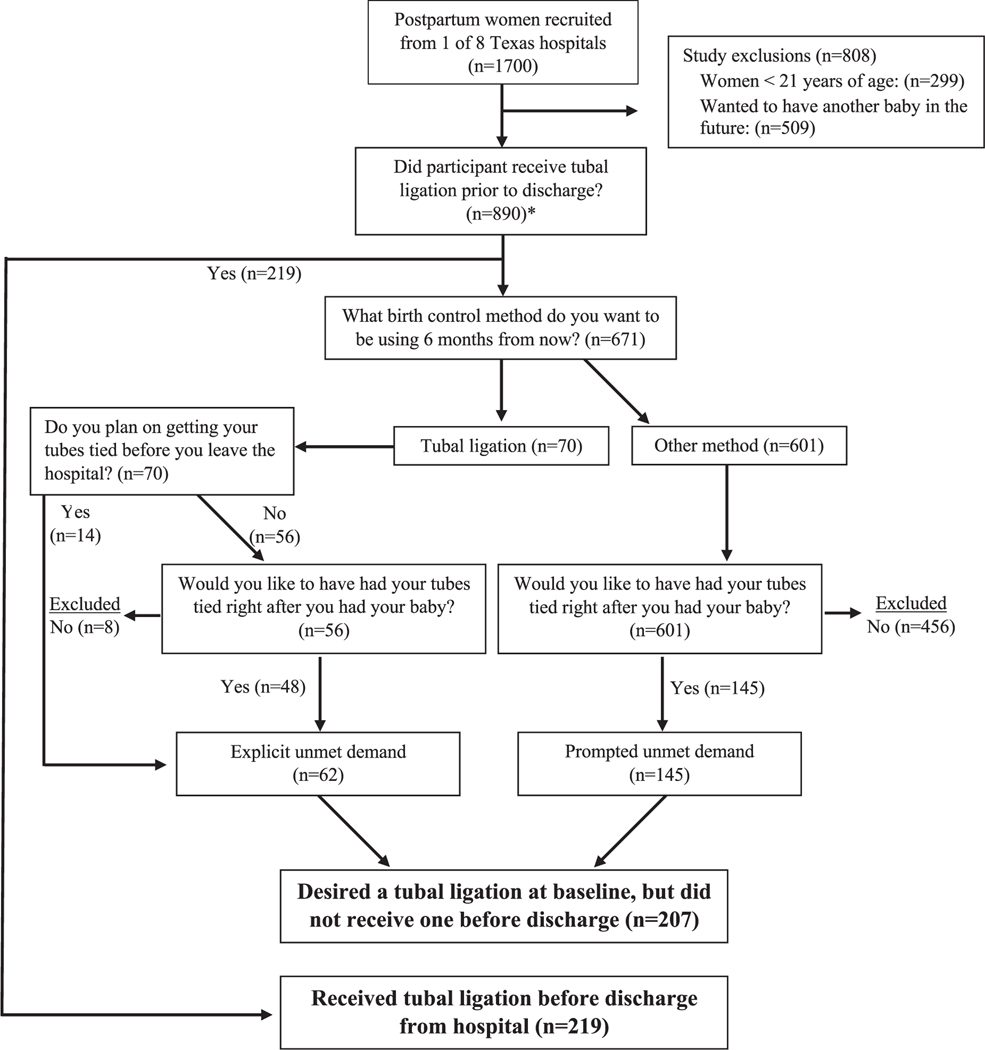

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the survey questions used to arrive at our analytical sample of women who desired a tubal ligation before hospital discharge. We classified all eligible participants who had not had a procedure prior to discharge into 2 groups based on the contraceptive method they wanted to be using 6 months after delivery: those who said they wanted to have a tubal ligation and those who said they wanted a different method. Respondents who said they wanted a procedure by 6 months were classified as having an explicit demand for a permanent method. Using information obtained in the 3-month interview, we verified if those women who were planning on having a procedure before leaving the hospital did so before discharge. The remaining participants were classified as having a prompted demand for a postpartum tubal ligation before discharge if, at baseline, they reported wanting to use another method in 6 months but also said they would have liked to have had their tubes tied after delivery.

Fig. 1.

Survey questions used to measure desire and receipt of postpartum tubal ligation prior to hospital discharge.

* Two participants not included in this number as a result of administrative error. Participants were mistakenly marked as having received a tubal ligation in preceding question and never included for follow-up questions.

We examined the distribution of women’s sociodemographic, prenatal care, and delivery characteristics according to their demand for permanent contraception: fulfilled demand, explicit unmet demand, and prompted unmet demand, using χ2 tests for independence. Among the 2 groups of women with unmet demand, we examined the barriers to obtaining a desired tubal ligation before hospital discharge and whether at the 3-month interview they still wished they had a tubal ligation right after delivery. To assess the impact of not receiving a desired procedure following delivery over the next 2 years, we examined the contraceptive methods used by participants with unmet demand at 6, 12, and 24 months. Suspecting substantial under-reporting of pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or early abortion, we decided to assess only those pregnancies that reached 12 weeks duration. We used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to calculate the proportion of participants who became pregnant within 21 months and continued that pregnancy until at least 12 weeks. We conducted all analyses using Stata 15 [16].

3. Results

The sample of women age 21 and over who wanted no additional children included 890 study participants. Figure 1 shows that 219 received a tubal ligation before discharge from the hospital following delivery, including 23 who had the procedure after the baseline interview but before discharge. Another 207 participants were classified as having wanted a postpartum procedure—62 who explicitly said that they wanted a tubal ligation by 6 months after delivery and either planned to have the procedure before discharge, or wished they had right after delivery, and 145 who, when prompted, said that they would like to have had the procedure right after delivery. The remaining 464 participants who did not express demand were excluded from further analysis.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of women in this sample were under 34 years of age and were US-born and foreign-born Hispanics, with relatively few participants identifying as Black, white, or another race. More than three-quarters were married or cohabiting, nearly one-half had just delivered a fourth or higher order birth, and more than a third had a cesarean delivery. About a quarter had more than a high-school education, almost a third went to a private provider for prenatal care, and almost all had public insurance coverage (Medicaid or CHIP-Perinate) at the time of the interview, but no insurance 6 months after delivery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of low-income women who delivered in Texas and desired an immediate postpartum tubal ligation, overall and according to procedure status, 2014–2018

| Postpartum tubal ligation statusa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obtained procedure (%) |

Unmet demand | ||||

| Respondent characteristics | Explicit (%) | Prompted (%) | Total (%) | pvalue | |

| Age | |||||

| 21–24 | 20 (29.0) | 15 (21.7) | 34 (49.3) | 69 (100.0) | |

| 25–29 | 57 (45.6) | 24 (19.2) | 44 (35.2) | 125 (100.0) | |

| 30–34 | 70 (58.3) | 13 (10.8) | 37 (30.8) | 120 (100.0) | |

| 35–39 | 57 (64.8) | 10 (11.4) | 21 (23.9) | 88 (100.0) | |

| 40–44 | 15 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (37.5) | 24 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity and nativity | |||||

| Hispanic, US-born | 63 (60.6) | 22 (21.2) | 19 (18.3) | 104 (100.0) | |

| Hispanic, foreign-born | 124 (50.8) | 17 (7.0) | 103 (42.2) | 244 (100.0) | |

| Black | 20 (36.4) | 17 (30.9) | 18 (32.7) | 55 (100.0) | |

| White and other | 12 (52.2) | 6 (26.1) | 5 (21.7) | 23 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Relationship status | |||||

| Married | 91 (54.2) | 20 (11.9) | 57 (33.9) | 168 (100.0) | |

| Single | 42 (42.4) | 20 (20.2) | 37 (37.4) | 99 (100.0) | |

| Cohabiting | 86 (54.1) | 22 (13.8) | 51 (32.1) | 159 (100.0) | 0.23 |

| Parity | |||||

| 1 | 4 (28.6) | 1 (7.1) | 9 (64.3) | 14 (100.0) | |

| 2 | 36 (48.6) | 4 (5.4) | 34 (45.9) | 74 (100.0) | |

| 3 | 72 (52.9) | 20 (14.7) | 44 (32.4) | 136 (100.0) | |

| ≥4 | 107 (53.0) | 37 (18.3) | 58 (28.7) | 202 (100.0) | 0.01 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 99 (54.1) | 24 (13.1) | 60 (32.8) | 183 (100.0) | |

| High school diploma | 64 (47.8) | 21 (15.7) | 49 (36.6) | 134 (100.0) | |

| More than high school | 56 (51.4) | 17 (15.6) | 36 (33.0) | 109 (100.0) | 0.84 |

| Prenatal care provider | |||||

| Public/Mexico/None | 155 (52.0) | 34 (11.4) | 109 (36.6) | 298 (100.0) | |

| Private | 64 (50.0) | 28 (21.9) | 36 (28.1) | 128 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Delivery type | |||||

| Vaginal | 75 (30.5) | 55 (22.4) | 116 (47.2) | 246 (100.0) | |

| C-section | 144 (80.0) | 7 (3.9) | 29 (16.1) | 180 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Signed consent | |||||

| Yes | 215 (72.6) | 47 (15.9) | 34 (11.5) | 296 (100.0) | |

| No | 4 (3.1) | 15 (11.5) | 111 b (85.4) | 130 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| Insurance coverage at baseline | |||||

| Insured | 213 (52.1) | 60 (14.7) | 136 (33.3) | 409 (100.0) | |

| Uninsured | 6 (35.3) | 2 (11.8) | 9 (52.9) | 17 (100.0) | 0.24 |

| Insurance coverage at 6 months c | |||||

| Insured | 38 (55.1) | 12 (17.4) | 19 (27.5) | 69 (100.0) | |

| Uninsured | 166 (53.4) | 40 (12.9) | 105 (33.8) | 311 (100.0) | 0.46 |

| Total | 219 (51.4) | 62 (14.6) | 145 (34) | 426 (100.0) | |

Postpartum tubal ligation status was classified as obtained if a woman obtained the procedure before hospital discharge, explicit if women stated that would be their preferred method of contraception 6 months after delivery, and prompted if they said they wanted to be using another method at 6 months but also reported that they would have liked to have their tubes tied after delivery.

Fifty-six women never signed the consent form because they never discussed tubal ligation with their provider.

Forty-six women were lost to follow-up by the 6-month interview.

The distribution of sterilization outcomes varied by age. Younger women obtained the procedure less frequently than older women. Foreign-born Hispanic and Black women obtained the procedure less frequently than US-born Hispanics. Black women more frequently had an explicit demand for tubal ligation than Foreign-born Hispanics. Participants who had a cesarean delivery were much more likely to obtain the procedure, as were those who signed a consent form.

The barriers to obtaining a desired tubal ligation before hospital discharge are shown in Table 2 according to the type of unmet demand reported by respondents in the baseline survey. Reports of hospital or system barriers or other reasons of a personal nature were most frequent among participants with explicit demand. In contrast, cost and provider barriers were reported more frequently by those with prompted demand.

Table 2.

Barriers to obtaining a desired tubal ligation before hospital discharge among low-income women who delivered in Texas and had an unmet demand for the procedure, overall and according to type of unmet demand, 2014–2018a

| Explicit (n = 62) | Prompted (n = 145) | Any unmet demand | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 7 (11.3) | 50 (34.5) | 57 (27.5) |

| Patient could not afford procedure | 4 (6.5) | 33 (22.8) | 37 (17.9) |

| Insurance did not cover procedure | 5 (8.1) | 25 (17.2) | 30 (14.5) |

| Hospital/system barriers | 36 (58.1) | 23 (15.9) | 59 (28.5) |

| Problems with consent form | 17 (27.4) | 15 (10.3) | 32 (15.5) |

| Patient did not have C-section | 12 (19.4) | 8 (5.5) | 20 (9.7) |

| Operating room was not available | 8 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (3.9) |

| Provider barriers | 6 (9.7) | 34 (23.4) | 40 (19.3) |

| Patient told she was too young | 0 (0.0) | 14 (9.7) | 14 (6.8) |

| Patient told she did not have enough children | 0 (0.0) | 11 (7.6) | 11 (5.3) |

| Provider would not operate (other reasons) | 4 (6.5) | 7 (4.8) | 11 (5.3) |

| Patient did not discuss with provider | 2 (3.2) | 9 (6.2) | 11 (5.3) |

| Other reasons | 25 (40.3) | 41 (28.3) | 66 (31.9) |

| Patient changed her mind | 4 (6.5) | 15 (10.3) | 19 (9.2) |

| Patient had health condition | 5 (8.1) | 6 (4.1) | 11 (5.3) |

| Patient did not have enough information | 3 (4.8) | 4 (2.8) | 7 (3.4) |

| Patient’s partner was opposed/had not yet discussed with partner | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.1) | 6 (2.9) |

| Other | 14 (22.6) | 10 (6.9) | 24 (11.6) |

| Number of barriers | |||

| 1 | 22 (35.5) | 107 (73.8) | 129 (62.3) |

| 2 + | 40 (64.5) | 38 (26.2) | 78 (37.7) |

Respondents could choose more than one option.

About one-third of participants with explicit demand who completed the 3-month interview had obtained an interval procedure, whereas only 3 with prompted demand had done so (Table 3). All but 3 of the participants with explicit demand who had not yet had a tubal ligation still wished they had obtained a postpartum procedure. Unmet demand also persisted among those with prompted demand at baseline, with 102 out of 130 (79%) still wishing that they had had a tubal ligation after delivery, but few having obtained the procedure.

Table 3.

Persistence in desire and procedure status 3 months after delivery among low-income women who delivered in Texas and had an unmet demand for an immediate postpartum tubal ligation, 2014–2018

| Desire for tubal ligation at baseline |

||

|---|---|---|

| Status at 3 months | Explicit desire (%) | Prompted desire (%) |

| Change in desire | ||

| Wants more children | 3 (5.6) | 14 (10.8) |

| No longer wishes she had a tubal ligation after delivery | 0 (0.0) | 11 (8.5) |

| Persistent desire | ||

| Still wishes she had a tubal ligation after delivery | 31 (57.4) | 102 (78.5) |

| Obtained sterilization | 20 (37.0) | 3 (2.3) |

| Total a | 54 (100.0) | 130 (100.0) |

Includes 2 respondents with an explicit desire and 3 respondents with a prompted desire who missed 3-month interview but were asked at 6 months.

At 6 months after delivery, 14% of those with unmet demand for tubal ligation had obtained an interval procedure or their partner had a vasectomy (Table 4). Additionally, 21% were using an intrauterine device (IUD) or implant, 20% were using another hormonal method, and 44% were using condoms, withdrawal or other less-effective methods; 2 had already reported a pregnancy. The method mix was similar at 12 and 24 months after delivery, but with a decrease in the proportion of women relying on less-effective methods as the number reporting pregnancies increased.

Table 4.

Contraceptive method use over 2 years following delivery among low-income women who delivered in Texas and did not receive a desired immediate postpartum tubal ligation, 2014–2018

| 6 months (%) | 12 months (%) | 24 months (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long acting | |||

| Interval tubal ligation | 25 (14.4) | 26 (16.3) | 26 (18.7) |

| Partner vasectomy | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.9) |

| IUD or implant | 37 (21.3) | 34 (21.3) | 33 (23.7) |

| Short acting Hormonal | 34 (19.5) | 32 (20.0) | 28 (20.1) |

| Condoms, withdrawal, other less-effective | 76 (43.7) | 65 (40.6) | 47 (33.8) |

| None | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Totala | 174 (100.0) | 160 (100) | 139 (100.0) |

Thirty-one respondents were lost to follow-up and 2 had reported a pregnancy by the 6-month interview, 39 were lost to follow-up and 8 had reported a pregnancy by the 12-month interview, and 44 were lost to follow-up and 24 had reported a pregnancy by the 24-month interview.

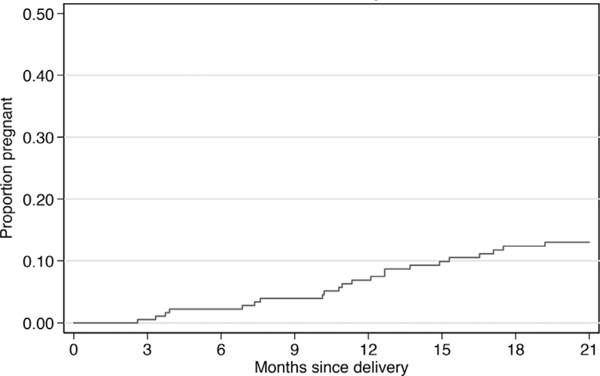

The estimated proportion of women with unmet demand for tubal ligation who conceived a pregnancy that they would carry to at least 12 weeks gestation is shown in Figure 2. The Kaplan-Meier estimate at 18 months postpartum is that 12.5% (95% CI: 8.3%–18.5%) conceived a pregnancy that they would likely carry to term. Few of these pregnancies were wanted or planned. Only one was preceded by the respondent stopping contraception in order to become pregnant, and 59% were reported retrospectively as unwanted.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative risk of pregnancy carried to at least 12 weeks among low-income women who delivered in Texas and did not receive a desired immediate postpartum tubal ligation, 2014–2018.

4. Discussion

In this sample of women who had public or no insurance for their delivery in urban Texas hospitals, we found a large unmet demand for postpartum tubal ligation. Approximately half of those who desired a postpartum tubal ligation did not receive it prior to discharge.

Our approach to assessing demand by asking participants if they would have liked a tubal ligation prior to hospital discharge revealed a much larger number of women with unmet demand for this procedure than would have been uncovered by relying solely on signed consent forms. Indeed, more than two-thirds of women in our study with an unmet demand were identified by the retrospective prompt, many of whom were younger and foreign-born Hispanic women.

It is likely that many of the younger women did not sign a consent form due to provider reluctance or counseling, whereas cost and insurance barriers were most important for foreign-born Hispanic women who did not meet the 5 years of legal US residency requirement to be eligible for pregnancy Medicaid coverage and postpartum contraceptive care in Texas. The barriers encountered by women identified by the prompt suggest that they may have perceived tubal ligation to be an unattainable option. The persistence of their demand was indicated by the large majority giving the same answer to the prompt at the baseline and 3-month interviews. Some respondents, however, did change their mind, mainly among those with prompted demand. In this group, by the 3-month interview, 19% either wanted more children or no longer wished they had had a tubal ligation after delivery.

The barriers encountered by women who explicitly reported a tubal ligation as their preferred method were mainly the hospital and systems-level barriers, such as problems with the Medicaid consent form and lack of an available operating room, that have been identified in other studies of unmet demand for tubal ligation [15,17–21]. Together with the barriers reported by participants with prompted demand for the procedure, they point to multiple areas that need to be addressed in order to meet patient’s contraceptive preferences prior to discharge. Several of these barriers likely affected participants’ ability to obtain an interval procedure.

In the 2 years following delivery, many women in this sample relied on less-effective methods, like condoms and withdrawal. This method mix likely results from the challenges that low-income women in Texas face in obtaining their preferred contraceptive method after delivery [ 15, 22 ], as well as the particular method preferences of participants who wanted a postpartum tubal ligation [23]. These patterns of contraceptive use resulted in some women with unmet demand becoming pregnant again soon after delivery.

In this analysis, there is an imperfect match between the women we classified as having an explicit demand and those who would have been included in an analysis of clinical records. Some women identified by the prompt had signed the Medicaid consent form. On the other hand, others who explicitly stated they would like to get a tubal ligation by 6 months postpartum had not signed the form. Notwithstanding these overlaps, our results provide a strong indication that unmet demand for tubal ligation identified in this study is substantially greater than that which would have been discovered from current clinical records.

A limitation of this study is that our sample is not representative of all women delivering with public insurance in Texas. The fact that we mainly recruited women in the largest cities, 2 of which were on the US-Mexico border, led to a higher proportion of Hispanics than would be found in Texas overall. Moreover, we can only speculate as to what may have happened to unmet demand for tubal ligation following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We suspect that it increased as a result of restrictions on elective procedures [24], and that the mandated extension of postpartum Medicaid coverage did little to offset this decline since so few interval procedures are performed in this population.

This study suggests that many women who desire a postpartum tubal ligation are not captured in assessments of unmet demand that rely solely on consent forms. To get a more comprehensive assessment, probes for unmet demand such as the one used in our study could be included in surveys administered before discharge. They could also be included on the discharge form and become an integral part of the woman’s electronic health record.

In addition to improved documentation of demand, policies to increase access to postpartum tubal ligation are warranted at the hospital, state, and federal levels. A key corrective measure would be to have clinicians probe for contraceptive preferences over the course of pregnancy, given that approximately half of those with a prompted desire did not discuss tubal ligation with their provider. There is also a need for medical education regarding eligibility criteria and provider bias. Other desirable measures would be to increase the availability of operating rooms, extend insurance coverage, increase reimbursement rates, and improve and facilitate the consent process. It might also be helpful to include failure to meet demand for tubal ligation and other contraceptive methods into the metrics used for quality evaluation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals who served as site investigators: Aida Gonzalez, MSN, RN, Moss Hampton, MD, Ted Held, MD, MPH, Nima Patel-Agarwall, MD, Sireesha Reddy, MD, Ruby Taylor, DNP, RN, and Cristina Wallace, MD.

Funding:

This project was supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, and a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C HD042849) awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Kari White also received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01 HD079563).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Chan LC, Westhoff C. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril 2010;94(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whiteman MK, Cox S, Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Jamieson DJ, Penman-Aguilar A, et al. Postpartum intrauterine device insertion and postpartum tubal sterilization in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206(127):e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nations United, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World contraceptive patterns 2013; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Allen RH, Desimone M, Boardman LA. Barriers to completion of desired postpartum sterilization. R I Med J 2013;96:32–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Seibel-Seamon J, Visintine JF, Leiby BE, Weinstein L. Factors predictive for failure to perform postpartum tubal ligations following vaginal delivery. J Reprod Med 2009;54:160–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thurman AR, Harvey D, Shain RN. Unfulfilled postpartum sterilization requests. J Reprod Med 2009;54:467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterlization requests. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Failure to obtain desired postpartum sterilization: risk and predictors. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum tubal sterilization. Contraception 2006;73:404–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wolfe KK, Wilson MD, Hou MY, Creinin MD. An updated assessment of postpartum sterilization fulfillment after vaginal delivery. Contraception 2017;96:41–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arora KS, Wilkinson B, Verbus E, Montague M, Morris J, Ascha M, et al. Medicaid and fulfillment of desired postpartum sterilization. Contraception 2018;97:559–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hahn TA, McKenzie F, Hoffman SM, Daggy J, Edmonds BT. A prospective study on the effects of Medicaid regulation and other barriers to obtaining postpartum sterilization. J Midwifery Womens Health 2018;64:186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Creinin M, Ibrahim S. The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States. J Womens Health 2009;18:91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Reeves MF, Bost JE, Creinin MD, Ibrahim SA. Race, insurance status, and tubal sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Potter JE, Coleman-Minahan K, White K, Powers DA, Dillaway C, Stevenson AJ, et al. Contraception after delivery among publicly insured women in Texas. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].StataCorp. Stata: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Potter JE, Stevenson AJ, White K, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Hospital variation in postpartum tubal sterilization rates in California and Texas. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brown BP, Chor J. Adding injury to injury: ethical implications of the Medicaid Sterilization Consent Regulations. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1348–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moaddab A, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA, Fox KA, Aagaard KM, Salmanian B, et al. Health care justice and its implications for current policy of a mandatory waiting period for elective tubal sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Turner K. Medicaid’s postpartum tubal sterilization policy’s effect on vulnerable populations; 2015.

- [21].Gilliam M, Davis SD, Berlin A, Zite NB. A qualitative study of barriers to postpartum sterilization and women’s attitudes toward unfulfilled sterilization requests. Contraception 2008;77:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Coleman-Minahan K, Dillaway C, Canfield C, Kuhn D, Strandberg KS, Potter JE. Low-income Texas women’s experiences accessing contraception at the first postpartum visit. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2018;50:189–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].White K, Hopkins K, Potter JE, Grossman D. Knowledge and attitudes about long-acting reversible contraception among Latina women who desire steril ization. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Evans ML, Qasba N, Shah Arora K. COVID-19 highlights the policy barriers and complexities of postpartum sterilization. Contraception 2022;103(1):3–5 S0010782420303620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]