This implementation science study demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of 2 strategies for integrating comprehensive sexual health activities into human immunodeficiency virus partner services, with lessons for program scale-up in other jurisdictions.

Background

We sought to develop a novel strategy for expanding an existing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) partner services (PS) model to provide comprehensive sexual health services, including sexually transmitted infection testing, a virtual telemedicine visit, and access to immediate start medication (antiretroviral treatment, preexposure or postexposure prophylaxis). Fast Track was a National Institutes of Health–funded implementation science trial in New York City to pilot and refine the new strategy, and examine its feasibility, acceptability, and impact.

Methods

Over the course of 1 year, health department staff collaborated with the academic research team to develop Fast Track protocols and workflows, create a cloud-based database to interview and track patients, and train disease intervention specialists to deliver the new program. The initial field-based program (Fast Track 1.0) was piloted March to December 2019. A modified telephone-based program (Fast Track 2.0) was developed in response to COVID-19 pandemic constraints and was piloted August 2020 to March 2021.

Results

These 2 pilots demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of integrating comprehensive sexual health services into HIV PS programs. Disease intervention specialists were successfully trained to conduct comprehensive sexual health visits, and clients reported that the availability of comprehensive sexual health services made them more willing to engage with PS. Key lessons for scale-up include managing collaboration with a licensed provider, navigating technical and technological issues, and challenges in client engagement and retention.

Conclusions

The success of this integrated strategy suggests that telehealth visits may be a critical gateway to care engagement for PS clients. This model is an innovative strategy for increasing engagement with HIV testing, prevention, and treatment for underserved populations.

Successful efforts to end the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the United States rely on: identification of individuals with undiagnosed infection, timely antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation and engagement in care for individuals diagnosed with HIV, and uptake of pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP or PEP) by those with potential HIV exposure. However, data on the HIV testing, ART, and PrEP cascades suggest significant disparities in uptake among priority populations that experience the greatest HIV incidence burden.1,2 Such disparities cannot be explained solely by differences in acceptability of prevention and treatment options, but are more likely attributed to a lack of accurate information and access to services in the communities, settings, and programs most likely to reach these clients.3

Utilizing a local health department's existing HIV partner services (PS) program is a logical and efficient method for engaging individuals at highest risk for HIV infection. Partner services are carried out by trained disease intervention specialists (DIS) and refer to the identification, tracing, and testing of sexual and needle-sharing partners of an individual diagnosed with HIV (“index patient”) or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).4 The goal of PS is to maximize timely exposure notification, testing, prevention or treatment, and linkage to clinical and social services among individuals exposed to HIV and their social networks. Across the United States, nearly 50,000 partners of newly diagnosed individuals are identified through HIV PS each year, and over 7500 undergo HIV testing revealing about 1200 new diagnoses.5 Individuals reached by DIS programs are, by definition, those most in need of HIV testing and linkage to treatment or prevention services. As such, to the extent that DIS reduce barriers to engagement, they can significantly reduce disparities in access to timely HIV testing and linkage to care.

The Fast Track Model

Fast Track is a collaboration between academic researchers (the Hunter Alliance for Research and Translation, Hunter College of the City University of New York) and a city health department (the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene [NYC DOHMH]) to design, implement, and evaluate a novel strategy that expands the current HIV PS model to provide a comprehensive sexual health intervention, including: STI testing, a virtual visit with a provider, and access to immediate start medication (ART, PEP, or PrEP). Fast Track is based on the hypothesis that offering clients prompt access to enhanced, comprehensive HIV and sexual health services in their homes would increase motivation and willingness to engage with the PS program and accept both HIV testing and subsequent linkage to PrEP or ART.6 A comprehensive sexual health intervention integrated into an existing PS program provides the ideal forum for a dynamic HIV and STI intervention that addresses the principal barriers (ie, awareness and access) that systematically contribute to low PrEP or ART uptake in priority populations.7 Evidence supports clients' interest in comprehensive, integrated HIV and STI sexual health services, and points to greater connections between STI and HIV services as a core component of an equity-focused, expanded PS strategy.8,9 Fast Track was supported as a National Institutes of Health–funded implementation science trial to pilot and refine the new strategy, and examine its feasibility, acceptability, and impact. While multiple PS programs in the United States have expanded to integrate PrEP referral or linkage,9,10 to our knowledge, this is the first implementation science study of the extension of HIV PS services to include field-based STI testing, virtual visits, and immediate start of PrEP/ART medication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of the Fast Track Model

Prior to the initiation of Fast Track, routine PS included: exposure notification, offer of HIV testing in the client's home or PS field office (fourth-generation rapid test with confirmatory dried blood spot testing, if indicated), HIV prevention and treatment education, screening for PEP, assessment of PrEP awareness and interest, and linkage to HIV care or PrEP through either the health department's sexual health clinics (SHC) or a community-based provider.11,12 Over the course of 1 year, health department staff collaborated with the academic research team to develop Fast Track protocols and workflows, create a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)13,14 cloud database to interview and track patients, and train DIS who would deliver the new program. These efforts resulted in the launch of the Fast Track 1.0 (Field-Based) pilot, conducted March through December of 2019. Eligibility for the pilot was restricted to partners of DIS index patients in 1 of 5 neighborhoods (19 zip codes) in Brooklyn, chosen based on high HIV incidence. Fast Track services were also offered to never-in-care (NIC) clients (ie, clients identified in the NYC HIV surveillance registry as living with HIV, but who had never been connected to HIV care since their initial diagnosis), living in one of these pilot zip codes.

Fast Track 1.0 (Field-Based Model)

The Fast Track 1.0 protocol was delivered either in the clients' home or in the PS field office, and included the following 4 enhancements to existing PS: (1) 3-site (oral, rectal, genital) gonorrhea and chlamydia testing (using self-collected urine samples and swabs); (2) a video telehealth visit with a SHC nurse practitioner (NP) to discuss the patient's HIV test result, HIV and STI prevention and treatment, as well as the benefits of ART or PrEP; (3) immediate medication start of either ART (if the patient's HIV test was positive) or PrEP (if the patient's HIV test was negative); (4) Expedited “fast track” follow-up appointment at one of the city's SHCs for additional HIV testing (HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay, HIV NAT and genotype), follow up with STI treatment if needed, syphilis testing, a potential 30-day “bridge” supply of PrEP medication, and additional navigation and linkage services to ongoing care. Clients could also opt to be referred directly to a community-based provider for HIV/STI prevention follow-up. Clients with positive HIV test results were immediately provided active linkage to care with a community-based provider for ongoing ART and HIV care.

Fast Track 2.0 (Telephone-Based Model)

A refined field-based Fast Track protocol (based on the successful pilot results) was implemented in January 2020. However, in March 2020, following New York City's implementation of COVID-19 control measures, community- and home-based PS and testing were suspended indefinitely. As a result, the PS program made the following changes to their standard services: notification communications were carried out via video call, voice call, or text message only; clients were offered mail-based delivery of an OraQuick HIV home test kit (HTK), with telephone-based support from DIS, if desired; and clients were referred to a newly created SHC telephone hotline instead of brick and mortar SHCs. We developed an alternative Fast Track Model to accommodate the new restrictions and measures, which included modified protocols and a new data collection system that reinvented Fast Track as a primarily remote, telephone-based program. The Fast Track 2.0 (Telephone-Based) pilot was conducted between August 2020 and March 2021. All PS clients were eligible for Fast Track 2.0, without geographic restrictions.

On top of the adjusted set of PS services introduced because of restrictions in place at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fast Track 2.0 added the following program enhancements: (1) Phone telehealth visit with a SHC NP to screen clients for STI symptoms (and provide same-day presumptive STI treatment, if indicated), discuss HIV and STI prevention as well as the benefits of PrEP/ART, and provide education and pre-screening for contraception; (2) Referral to SHC telehealth PrEP insurance navigation that could pre-authorize PrEP before an in-person SHC visit; (3) same-day courier (as opposed to mail-based) delivery of HIV HTKs; and (4) Expedited “fast track” in-person appointment at one of the SHCs for HIV testing, STI testing/treatment, immediate ART or PrEP start (based on prior insurance navigation), contraceptive provision (including prescription medication or long-acting reversible contraceptive placement), and additional navigation and linkage services. Table 1 details the ways in which each service component was delivered in the 2 different models.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Service Delivery Protocols in Fast Track 1.0 Versus 2.0

| Fast Track 1.0 | Fast Track 2.0 | |

|---|---|---|

| HIV testing | Conducted in client's home or PS field office by DIS. Rapid fourth-generation with confirmatory DBS, if indicated. | Referred to SHC for rapid and confirmatory testing. Offered HTK delivery with support. |

| Telehealth visit | Video call with SHC NP during PS visit, facilitated by DIS. | Stand-alone telephone call with SHC NP facilitated by DIS. |

| STI testing | Community-based self-collection with delivery to SHC for processing. SHC NP followed up for treatment. | Screened for symptoms by SHC NP (during telehealth visit). Referred to SHC for testing and treatment. |

| PrEP education/counseling | Provided in-person during PS visit by DIS and during telehealth visit by SHC NP. | Provided via telephone during PS notification by DIS and during telehealth visit by SHC NP. |

| Contraceptive counseling | Not included. | Provided during telehealth visit by SHC NP. |

| Insurance navigation | DIS screened for coverage that would allow easy continuation after immediate start. Otherwise, referred for insurance navigation at SHC or CBO. | SHC NP provides referral for all patients interested in PrEP. Provided via telephone by SHC Navigator. Enables immediate start at SHC visit. |

| Medication start | Immediate starter pack of PrEP or ART (3–6 d) during PS in-person visit (if medically eligible and has coverage to continue medication—see financial navigation). | Immediate start (PrEP or ART) available at SHC visit. |

| Linkage and referral | Priority SHC visit for patients who wanted linkage there; facilitated referral to CBOs. Primary follow-up for linkage is by DIS. | SHC appointment or facilitated referral to CBO. Follow-up is shared between SHC NP and DIS. |

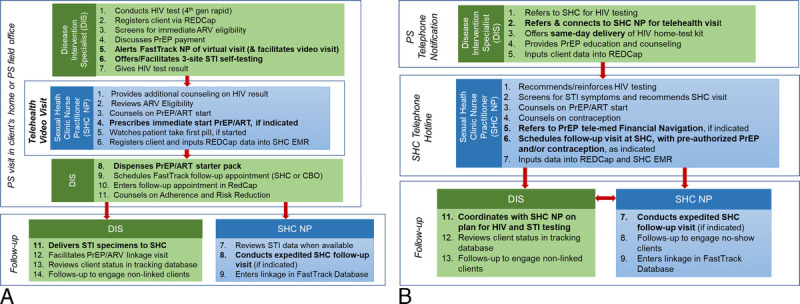

Fast Track 1.0 and 2.0 Visit Flow

Figures 1A and B compare the visit flows for each of the program models and highlight the enhanced components in each (Fast Track enhancements are bolded). In Fast Track 1.0, the PS visit starts with HIV test collection, and includes additional sexual health services while the test result is pending. Clients are registered by the DIS in the REDCap database, which facilitates SHC Electronic Medical Record (EMR) registration by the SHC NP later in the visit. The DIS conducts preliminary eligibility screening for immediate ART start, from both a medical (eg, history of kidney disease, acute HIV symptoms) and a financial standpoint (ie, the clients' insurance would enable them to receive a full PrEP prescription within the 6-day starter pack timeframe). Immediately after providing the HIV test result, the DIS initiates a video telehealth visit (using a health department video device and mobile hotspot) with the SHC NP, who can then further educate the patient on PrEP or ART and provide a prescription, if indicated. In the Fast Track 1.0 protocol, DIS delivered the self-collected STI specimens to the SHC for processing. The SHC was then responsible for notification and treatment of any positive STI results. Fast Track 1.0 also included “expedited” SHC visits, in which the SHC NP would schedule the client to see them for a specific SHC appointment, rather than rely on standard walk-in protocols.

Figure 1.

A, Visit flow and enhanced components for Fast Track 1.0 (Field-Based Model). Note: Bolded services denote specific Fast Track enhancements. B, Visit flow and enhanced components for Fast Track 2.0 (Telephone-Based COVID Adaptation). Note: Bolded services denote specific Fast Track enhancements.

The Fast Track 2.0 protocol separated the activities of the DIS and SHC NP, because each conducted individual telephone visits with clients. As noted above, telehealth visits in Fast Track 2.0 were expanded to include counseling on contraception, as well as referral to phone-based PrEP insurance navigation (both of which were new SHC services developed during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic). One of the strengths of the Fast Track 2.0 model was this pre-authorization and insurance navigation prior to arrival at the SHC, which enabled clients to immediately start PrEP at the SHC and granted the assurance that they would be able to continue receiving PrEP care at their linkage site. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the SHCs also began scheduling client visits by appointment (as opposed to walk-in only). In addition, Fast Track 2.0 involved greater coordination between DIS and the SHC NP for client follow-up and engagement, to ensure that clients completed an in-person services visit at a SHC or community-based organization (CBO).

Data Collection

For both Fast Track 1.0 and Fast Track 2.0, all data were collected in a secure online REDCap Cloud database meeting Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance requirements, designed specifically for use on this project and hosted by the city health department. Case reports were also made available to supplement any data that may have been missing or unclear based on REDCap alone. The academic research team conducted qualitative interviews with program participants who agreed to be contacted to discuss their experiences with the program. Twenty-five participants agreed to be contacted (10 in Fast Track 1.0 and 15 in Fast Track 2.0). Of these, 9 (36%) were reached and agreed to participate in interview (5 in Fast Track 1.0 and 4 in Fast Track 2.0). All study procedures were approved by the Hunter College and the NYC DOHMH Institutional Review Boards.

Measures and Analysis

Client demographics, insurance, and housing data were sourced from REDCap and case reports. Service utilization and patient outcomes were assessed by creating and summarizing a series of categorical variables from the same data sources, and included: HIV testing, PrEP services, PEP services, linkage to care among newly diagnosed patients, and STI testing and treatment. For this article, we analyzed qualitative data from 9 participants (5 Fast Track 1.0 clients and 4 Fast Track 2.0 clients). We used rapid qualitative analysis techniques15 focused exclusively on 2 areas: (1) acceptability of STI testing; and (2) satisfaction with telehealth visits. Relevant quotations were extracted from interview recordings and integrated into summary templates. Summary data were then examined to identify key themes and findings across participants. The goal of this analysis was to shed light on clients' experiences with the enhanced Fast Track services.

RESULTS

Client Characteristics

The demographics of both samples are reflective of new HIV diagnoses in New York City, as well as the population served by the PS Program (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Fast Track Client Characteristics at Intake*

| Partner Services Clients | FT 2.0 NIC Clients (n = 3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT 1.0 (n = 12) | FT 2.0 (n = 23) | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Cisgender man | 8 | 67% | 20 | 87% | 2 | 67% |

| Cisgender woman | 4 | 33% | 3 | 13% | 1 | 33% |

| Sexual partner pairings† | ||||||

| MSM | 6 | 50% | 11 | 48% | — | — |

| MSW | 2 | 17% | 8 | 35% | — | — |

| WSM | 4 | 33% | 3 | 13% | — | — |

| Unknown | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | — | — |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Latino/Hispanic (any race) | 5 | 42% | 7 | 30% | 1 | 33% |

| Black non-Hispanic | 6 | 50% | 12 | 52% | 2 | 67% |

| White non-Hispanic | 1 | 8% | 3 | 13% | 0 | 0% |

| Other (not specified) | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 20–29 | 7 | 58% | 11 | 48% | 1 | 33% |

| 30–39 | 3 | 25% | 6 | 26% | 0 | 0% |

| 40–49 | 2 | 17% | 4 | 17% | 0 | 0% |

| 50–59 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 9% | 1 | 33% |

| 60+ | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 33% |

| Borough | ||||||

| Brooklyn | 12 | 100%‡ | 9 | 39% | 0 | 0% |

| Bronx | — | — | 7 | 30% | 2 | 67% |

| Manhattan | — | — | 5 | 22% | 0 | 0% |

| Queens | — | — | 2 | 9% | 0 | 0% |

| Staten Island | — | — | 0 | 0% | 1 | 33% |

| Housing status | ||||||

| Stably housed | 11 | 92% | 18 | 78% | 2 | 67% |

| About to lose housing | 1 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| At risk of losing housing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 33% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0% | 5 | 22% | 0 | 0% |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Medicaid | 5 | 42% | 9 | 39% | 1 | 33% |

| Private | 3 | 25% | 4 | 17% | 1 | 33% |

| Medicaid and private | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Uninsured | 4 | 33% | 3 | 13% | 0 | 0% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0% | 6 | 26% | 1 | 33% |

*Fast Track 1.0 was implemented March to December 2019, and Fast Track 2.0 was implemented August 2020 to March 2021.

†In cases of individuals who had sexual partners of more than 1 gender, clients are classified based on the gender of the newly diagnosed index patient, if known. In FT 1.0, the HIV+ male partner of 1 WSM client was a transgender man. No other clients specifically indicated that the HIV+ index partner was transgender.

‡Eligibility criteria for FT 1.0 included residence in 1 of 5 Brooklyn zip codes.

Fast Track 1.0 (Community-Based)

From March to December 2019, 201 newly diagnosed-HIV index cases living in eligible Fast Track zip codes were assigned and interviewed by the DIS, yielding 100 exposed partners to be contacted. Of these partners, 63 (63%) were successfully contacted by DIS, and 56 (89% of those contacted) were offered Fast Track services (the remaining 7 declined notification services and terminated the interview before PS could offer Fast Track, were located but not notified, or stopped responding). Of these 56, 33 (59%) refused all PS services (23 refused HIV testing; 10 reported having recently tested) and 23 (41%) engaged with PS. Of these 23, 5 (9%) refused a PS visit but accepted an HIV testing referral, and 4 (8%) accepted HIV testing through PS, but refused additional Fast Track services. The remaining 16 clients (29%) accepted Fast Track; however, 4 did not attend their appointment and stopped responding to subsequent outreach attempts. As a result, Fast Track 1.0 services were provided to 12 partners of the 100 HIV cases, representing 12% of partners identified, 23% of partners notified, and 52% of partners who accepted PS services. In addition, 44 NIC clients were identified as eligible for Fast Track (based on zip code) by NYC DIS. Of these NIC clients, 6 were located (14%), of whom 3 refused all services and 3 accepted linkage but refused FT. See Table 3 for a summary of program utilization across Fast Track 1.0 and 2.0.

TABLE 3.

Fast Track Partner Services Clients Program Utilization

| Fast Track 1.0 (n = 12) March to December 2019 | Fast Track 2.0 (n = 23) August 2020 to March 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %* | %† | n | %* | %† | |

| NP telehealth visit | 12 | 100% | 100% | 21 | 91% | 91% |

| HIV testing | ||||||

| Tested for HIV | 12 | 100% | 100% | 18 | 86% | 78% |

| Positive result | 1 | 8% | 8% | 3 | 17% | 13% |

| Negative result | 11 | 92% | 92% | 15 | 83% | 65% |

| Interested in HTK | — | — | — | 10 | 48% | 43% |

| Used HTK | — | — | — | 2 | 20% | 9% |

| PrEP services cascade | ||||||

| Educated about PrEP | 12 | 100% | 100% | 21 | 100% | 91% |

| Interested in or referred for PrEP | 10 | 91%‡ | 83% | 18 | 86%‡ | 78% |

| Received starter packs in field | 5 | 50% | 42% | — | — | — |

| Started PrEP | 4 | 40%§ | 33% | 10 | 59%§ | 43% |

| Scheduled refill appointment | 3 | 75% | 25% | 8 | 80% | 35% |

| Refill appointment confirmed | 1 | 33% | 8% | 4 | 50% | 17% |

| PEP services cascade | ||||||

| Eligible | 2 | 18%¶ | 17% | 3 | 20%¶ | 13% |

| Accepted and completed | 1 | 50% | 8% | 2 | 67% | 9% |

| PEP to PrEP | 0 | 0% | 0% | 2 | 100% | 9% |

| Linkage to Care | ||||||

| Newly Diagnosed | 1 | 8% | 8% | 3 | 17% | 13% |

| Started ART (total) | 1 | 100% | 8% | 1 | 33% | 4% |

| Immediate start ART | 1 | 100% | 8% | 2 | 67% | 9% |

| Confirmed linkage to care | 1 | 100% | 8% | 3 | 100% | 13% |

| STI testing and treatment | ||||||

| Tested for GC/CT | 12 | 100%∥ | 100% | 13 | 100%∥ | 57% |

| Positive | 2 | 17% | 17% | 3 | 23% | 13% |

| Treated | 2 | 100% | 17% | 3 | 100% | 13% |

| Tested for syphilis | 7 | 58%∥ | 58% | 13 | 100%∥ | 57% |

| Positive | 2 | 29% | 17% | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| Treated | 2 | 100% | 17% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

NOTE: Percentages should be interpreted with caution, given the small sample size.

*Percentage among relevant subgroup of patients.

†Percentage among all.

‡Interested in PrEP, among those who tested HIV-negative in the field, for FT 1.0. Referred for PrEP, among all, for FT 2.0. This is due to HIV testing being performed at a separate in-person visit, after initial phone-based PrEP referral services.

§Among those interested in starting PrEP, for FT 1.0. For FT 2.0, the denominator excludes 1 person who was referred for PrEP but then tested HIV-positive and initiated immediate start ART.

¶Among those who tested HIV negative.

∥STI testing among all in FT 1.0 and among those who came to an NYC SHC in FT 2.0 (n = 13).

All 12 Fast Track 1.0 clients received HIV testing, self-collected STI testing, PrEP education, and a virtual visit with the SHC NP during their PS visit. One client tested HIV-positive, received a starter pack of ART administered by the DIS during the virtual visit with the SHC NP, and was immediately linked to care at a community-based provider. Of the 11 clients who tested HIV-negative, 10 were interested in immediate PrEP start. Three were not eligible due to insurance limitations but were referred to the SHC for insurance navigation. Two were identified as eligible for PEP and utilized the NYC PEP hotline to receive PEP. One of these 2 completed PEP but did not start PrEP, and the other, in consultation with the SHC NP, decided to discontinue PEP and not start PrEP given her specific circumstances (low risk of HIV transmission). The remaining 5 clients received PrEP starter packs and took their first PrEP dose during the virtual SHC NP visit. Among those, 1 individual did not continue taking PrEP beyond the starter pack, due to insurance issues and clinical concerns, and was referred to their primary care physician (PCP). In sum, from the 201 index partners interviewed, 100 partners were identified, 63 were contacted, 12 were visited by DIS, and 7 were successfully started on antiretroviral medication, including 1 on ART, 2 on PEP and 4 on PrEP.

Of the 12 clients who conducted self-administered STI testing, all provided urine samples, 10 conducted oral self-swabs, and 4 conducted rectal self-swabs. Only 1 sample (oral) was deemed unsatisfactory. Two cases of CT/GC (chlamydia/gonorrhea) were detected, including 1 genital CT, and 1 oral GC. There were also 2 cases of latent syphilis detected. All clients who tested positive received treatment for their STIs at a SHC.

Fast Track 2.0 (Telephone-Based)

From October 2020 to March 2021, 643 newly diagnosed HIV index cases were assigned and interviewed by the DIS, yielding 169 exposed partners eligible for Fast Track Services. Of these, 121 (72%) were contacted by DIS, 99 (82% of those contacted) were offered Fast Track services, and 23 (23%) accepted. In addition, 32 NIC clients were identified, 6 were contacted, 3 declined all PS services, and 3 accepted Fast Track. Of the 26 clients (23 partners, 3 NIC) who accepted Fast Track services, 24 (92%) were successfully linked to the SHC NP for a telehealth phone visit. As a result, Fast Track 2.0 services were provided to 24 clients (21 exposed partners and 3 NIC clients), representing 12% of clients identified, 19% of clients notified, and 62% of clients who accepted PS services.

Ten clients expressed interest in an HIV HTK, and 9 were sent these kits (one did not provide contact information). Only 2 clients reported using the HTKs, one on their own and one with remote DIS supervision. Seventeen clients received HIV testing following their Fast Track visit at the SHC (median time to HIV test, 4 days; interquartile range, 5.25 days), and 2 tested HIV-positive. One tested positive for HIV at the SHC, received immediate ART, and was linked to care; the other tested positive at an outside organization and started ART at a later visit. One additional client who was originally lost to follow-up but reengaged 14 months after his initial Fast Track visit, tested positive for HIV and was also linked to care.

Thirteen Fast Track clients visited a SHC following their telemedicine visit, and 4 had confirmed visits with CBOs. All 13 clients who visited the SHC were tested for CT/GC using self-swabbing, and for syphilis with blood-based testing. Three positive CT cases were identified, all of whom were treated at an SHC.

The SHC NP discussed PrEP with all 21 Fast Track clients. Eighteen were referred for PrEP, including 2 who were identified as PEP-eligible and completed a course of PEP prior to transitioning to daily PrEP. A total of 10 attended a follow-up visit and started PrEP, one of whom opted for PrEP-on-demand. Eight of these clients scheduled a refill appointment at an external provider, and Fast Track staff were able to confirm that 4 completed their refill appointment. One additional client was PEP-eligible but declined PEP referral. In sum, from the 643 index partners interviewed, 169 partners were identified, 99 were contacted, 23 accepted Fast Track services, and 12 were successfully started on antiretroviral medication via Fast Track, including 8 directly on PrEP, 2 PEP to PrEP, and 2 on ART.

In addition to partner cases, Fast Track 2.0 also reached 3 (9%) of the 32 eligible NIC clients. All 3 of these clients had a telehealth visit with the SHC NP, were subsequently linked to HIV care, and started on ART.

Qualitative Interviews

Acceptability of STI Testing

Interview participants from Fast Track 1.0 indicated high acceptability of self-collection for STIs during the PS visit. Participants indicated that they liked the comprehensive and “holistic” approach to sexual health and appreciated not having to make a separate appointment for STI testing. In the words of 1 participant: “We're already here testing for one thing [HIV], so let's go ahead and test for everything!” (Black cisgender gay man, 20s). Even clients who reported that they were generally anxious about self-swabbing were happy with the experience and said they felt it went smoothly. Fast Track 2.0 participants also cited their appreciation for the holistic approach to combining HIV and STI testing: “I am in-between insurance, so when [the SHC NP] said I could get a full STI panel in addition to the HIV test for free, I decided to go in for the appointment” (white cisgender gay man, 40s).

Satisfaction With Telehealth Visits

Participants in both Fast Track 1.0 and 2.0 were extremely satisfied with their telehealth communication with the SHC NP. Participants cited the importance of a combination of warmth and professionalism: “she made a person feel at ease” (Black cisgender man with cisgender and transgender women partners, 20s, 1.0 client); “She kept it really light, but really respectful” (Black cisgender heterosexual man, 20s, 2.0 client); “She was really receptive to my needs and felt personable but also professional” (Black cisgender gay man 20s, 1.0 client). Participants credited the telehealth call with their further engagement in services: “[the NP] created a sense of urgency, but not panic, to come get tested for everything and think about PrEP and my risk” (white cisgender gay man, 40s, 2.0 client); “The NP was really nice and she made me an appointment to get tested for everything and start PrEP. It was so easy. I wouldn't have tested or anything if they hadn't set it all up for me” (Black cisgender heterosexual man, 20s, 2.0 client).

DISCUSSION

These 2 pilot programs demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of integrating comprehensive sexual health activities – field-based STI testing, field-based immediate ARV start, telehealth visits, and pre-visit PrEP insurance navigation – into HIV PS programs. In Fast Track 1.0, DIS were successfully trained to conduct comprehensive sexual health visits in the field involving both self-collected STI testing and immediate ARV start for treatment or prophylaxis. Self-collection of STI samples during PS visits was acceptable and even attractive to clients, samples were satisfactory for testing, and identified new STI cases that were successfully linked to treatment. In both Fast Track 1.0 and 2.0, PS clients reported benefiting from the facilitated telehealth visit that was offered as part of exposure notification for partners or re-engagement services for NIC individuals living with HIV. Both PrEP and immediate ART were successfully prescribed during the telehealth visit in Fast Track 1.0 and starter packs were dispensed by DIS during the PS visit. Clients reported that these telehealth encounters and the availability of ART motivated them to accept testing, prevention, and treatment services. Clients also reported that the availability of more comprehensive sexual health services made them more willing to engage with the care being offered.

The core of this integrated strategy was successful collaboration between the health department's PS program and their SHCs, specifically with a NP dedicated to the project. Both Fast Track 1.0 and 2.0 relied on active, real-time communication between DIS and the SHC NP, both during PS visits and for follow-up. The ability of DIS to administer self-collected STI testing during PS visits was facilitated by the ability to register PS contacts in the SHC EMR, and the ability of the SHC to accept and process the samples for testing. The ability of DIS to dispense immediate start medication was facilitated by collaboration with the licensed SHC NP, who could prescribe the medication during the telehealth visit and document the dispensing in the SHC EMR. Real-time screening, information sharing, and client tracking were facilitated by the REDCap data system created by the PS team, and accessed jointly by the DIS and SHC NP.

These pilots suggest that telehealth visits may be a critical gateway to care engagement for PS clients. This strategy seems to work via a video visit during the PS encounter (Fast Track 1.0) or via consecutive but separate telephone visits with the DIS and an NP (Fast Track 2.0). In both cases, clients reported that attentive care and service by the SHC NP was the critical factor for them. Clients receiving community-based PS are often not engaged in health care, and the notification process may be the first time they are considering HIV or STI services, or the first time they have ever spoken directly to a provider about their sexual health. In the time that has passed since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the practice of telemedicine and virtual consultation has become even more accepted and might allow additional leverage for these types of comprehensive hybrid services.

Insurance and medication coverage remain barriers to PrEP uptake and the implementation of this type of comprehensive sexual health program. In Fast Track 1.0, concerns about whether clients' insurance would enable them to continue PrEP medication following the initial 6-day starter pack (due to pre-authorization requirements or medication assistance paperwork for uninsured patients) prevented DIS from offering immediate medication start to half of the clients who were interested, and may have resulted in the program being unable to capitalize on the momentum established toward PrEP adoption. In Fast Track 2.0, the availability of phone-based PrEP insurance navigation prior to a PrEP prescription visit at the SHC allowed clients to receive more streamlined services, and resulted in more successful long-term prescriptions of PrEP. In addition, integrating PrEP education and offers into sexual health appointments that include contraception prescription could help increase the acceptability and accessibility of PrEP for cisgender women, a priority population notably lacking in PrEP use.

However, despite the feasibility of the program and its acceptability to the clients who received it, it is important to note the persistent barriers to engagement of partners and NIC clients that limited the reach of Fast Track services. During the Fast Track 1.0 pilot, only 11% of clients identified (26/245) engaged with PS services, and only 6% (39/675) of those identified during Fast Track 2.0 engaged with PS services. Given these low numbers and the pilot nature of the program, it is impossible to make any claims about the effectiveness of Fast Track service expansion in reaching more PS clients. More detailed comparison with retrospective data, as well as increased monitoring of outcomes for clients over time will help us evaluate its potential impact.

With this caveat, the Fast Track pilots provide several lessons for other jurisdictions that might want to implement similar strategies. Most important is the participation of a licensed provider, either as part of the PS team or as a collaboration with a city SHC or other agency. Fast Track demonstrates that acceptable and feasible protocols can be developed to facilitate STI specimen collection and medication dispensing by DIS, provided that this type of clinical collaboration is in place. Second are technical and technological considerations, including creation of a shared, cloud-based but HIPAA-compliant data management system, and the availability of video-enabled devices and adequate cellular service to facilitate video-based telehealth visit during PS encounters. And third is the extent to which engaging DIS clients and facilitating sustained follow-up continues to be a critical challenge. Although these pilots demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of these program components, the overall number of clients served and linked to ART was low. Many PS clients have extenuating circumstances, including work and domestic situations, which make following up at clinic appointments during traditional hours of operation, availability, and location difficult. The creative and client-centered strategies employed by DIS to engage clients in the community are a model for the creation of innovative programs and protocols that focus on overcoming traditional barriers to access for highest priority populations.

Information collected from this pilot has informed the expansion of the Fast Track programs, which is currently being implemented and studied on a larger scale to examine the potential population level impact of this type of integrated and comprehensive service delivery. Future efforts to increase health equity and achieve Ending the HIV Epidemic goals should consider innovative strategies for integrating these components into existing programs to increase access for highest priority populations uniquely reached by DIS programs.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: Fast Track was conceived by Dr. Demetre Daskalakis and was made possible by his visionary leadership. The authors thank the ACE Team, staff at the Fort Greene Sexual Health Clinic, and HIV and STI program staff at leadership at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for all their efforts in this work. The authors are indebted to the participants who shared their experiences as part of the Fast Track program.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Sources of Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health: R01MH115835 (Golub, PI).

Contributor Information

Devon M. Price, Email: devonprice49@gmail.com.

Lila Starbuck, Email: lila.starbuck@hunter.cuny.edu.

Christine Kim, Email: ckim6@health.nyc.gov.

Leah Strock, Email: lstrock@health.nyc.gov.

Kavita Misra, Email: kmisra@health.nyc.gov.

Tarek Mikati, Email: tarekmikati76@gmail.com.

Chi-Chi Udeagu, Email: cudeagu@health.nyc.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nosyk B Krebs E Zang X, et al. “Ending the epidemic” will not happen without addressing racial/ethnic disparities in the United States human immunodeficiency virus epidemic. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:2968–2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS Satcher Johnson A Pembleton ES, et al. Epidemiology of HIV in the USA: Epidemic burden, inequities, contexts, and responses. Lancet 2021; 397:1095–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyrer C Adimora AA Hodder SL, et al. Call to action: How can the US ending the HIV epidemic initiative succeed? Lancet 2021; 397:1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dooley SW Dubose OT Fletcher JF, et al. Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008; 57(RR-9):1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV Partner Services Annual Report, 2019. 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/cdc-hiv-partner-services-annual-report-2019.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2022.

- 6.Rojas Castro D, Delabre RM, Molina JM. Give PrEP a chance: Moving on from the “risk compensation” concept. J Int AIDS Soc 2019; 22:e25351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochberg CH, Berringer K, Schneider JA. Next-generation methods for HIV partner services: A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer KH Nelson L Hightow-Weidman L, et al. The persistent and evolving HIV epidemic in American men who have sex with men. Lancet 2021; 397:1116–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz DA Dombrowski JC Barry M, et al. STD partner services to monitor and promote HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among men who have sex with men. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80:533–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira da Silva D Bouris A Ramachandran A, et al. Embedding a linkage to preexposure prophylaxis care intervention in social network strategy and partner notification services: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 86:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bocour A Renaud TC Udeagu CC, et al. HIV partner services are associated with timely linkage to HIV medical care. AIDS 2013; 27:2961–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padilla M Mattson CL Scheer S, et al. Locating people diagnosed with HIV for public health action: Utility of HIV case surveillance and other data sources. Public Health Rep 2018; 133:147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA Taylor R Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA Taylor R Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor B Henshall C Kenyon S, et al. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e019993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]