Objective

A special presentation of foreign body granuloma originating from the lateral process of the malleus (FBGLP) was noted in the absence of a history of foreign body entry into the external auditory canal (EAC). This study reported the clinical features, pathology, and prognosis of patients with FBGLP.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

Shandong Provincial ENT Hospital.

Patients

Nineteen pediatric patients (age, 1–10 yr) with FBGLP.

Interventions

Clinical data were collected from January 2018 to January 2022.

Main Outcome Measures

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients were analyzed.

Results

All patients had an acute course, and were within 3 months of ineffective medical treatment. The most common symptoms were suppurative (57.9%) and hemorrhagic (42.1%) otorrhea. FBGLP imaging examinations demonstrated a soft mass blocking the EAC without bone destruction and occasionally concomitant effusion in the middle ear. The most common pathologic findings were foreign body granuloma (94.7%,18/19), granulation tissue (73.7%, 14/19), keratotic precipitate (73.7%, 14/19), calcium deposition (63.2%, 12/19), hair shafts (47.4%, 9/19), cholesterol crystals (5, 26.3%), and hemosiderin (15.8%, 3/19). Foreign body granuloma and granulation tissue showed higher expression levels of CD68 and cleaved caspase-3 than did the normal tympanic mucosa, whereas Ki-67 levels were similarly low in all tissues. The patients were followed up for 3 months to 4 years without recurrence.

Conclusion

FBGLP is caused by endogenous foreign particles in the ear. We recommend the trans-external auditory meatus approach for FBGLP surgical excision, as this shows promising outcomes.

Key Words: Lateral process of malleus, Children, Foreign body granuloma, Outer ear

INTRODUCTION

Granuloma formation can be induced by infectious agents, foreign bodies, and many inflammatory diseases with unknown etiologies (1,2). In the ear, a granuloma in the external auditory canal (EAC) commonly forms due to inflammation of the outer or middle ear, cholesteatoma, and foreign bodies, which may manifest as benign or malignant tumors (3,4). Therefore, once a granuloma is found in the EAC, timely imaging is necessary to define the location and extent of the lesion. If necessary, surgical removal with biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis and avoid further complications caused by EAC blockage. Identifying the origin of the granuloma can help otorhinolaryngologists clarify its etiology, implement precautions, and develop appropriate therapy plans.

In this study, we noticed a particular presentation of foreign body granuloma originating from the lateral process of the malleus (FBGLP) in children who lacked a visible foreign body in the EAC. The clinicopathologic characteristics of 19 such patients were retrospectively analyzed. By comparing their clinical features and pathologic morphologic characteristics, the pathogenic causes were further evaluated to help explore the etiology, optimal treatment, and prognosis for FBGLP.

METHODS

The study was approved by the relevant institutional ethics review board (approval number: XXX). We retrospectively evaluated 24 patients who underwent surgical excision of a foreign body granuloma from the EAC between January 2018 and January 2022 at the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery of XXX Hospital (Fig. 1). The primary selection criteria were as follows: patients who had undergone microsurgical excision of a granuloma originating from the lateral process of the malleus. Altogether, 21 patients were enrolled, including two adults who were lost to follow-up after excision of the granuloma in the outpatient department. Therefore, 19 patients, who were otherwise healthy, with no history of surgery, otitis media, or systemic immune diseases, were analyzed in this study. Levofloxacin and dexamethasone were applied as ear drops continuously before the surgery; however, systemic antibiotics were combined in some patients, but the treatments were ineffective and no granuloma reduction was observed. Clinical records, including the patients’ age and sex, laterality (right or left ear), clinical signs and symptoms, disease duration, granuloma location, treatment modalities, and outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of study.

TABLE 1.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| No | Age (yr) | Gender | Side | Inducement | Duration | Symptoms | Temporal Bone CT/MRI Finding | Hearing Level of ABR (ABG) | Hearing Level of PTA (ABG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Famale | Left | No | 1 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC and Effusion of middle ear | 25 dB | — |

| 2 | 6 | Male | Right | No | 2 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | — | 0 dB |

| 3 | 3 | Male | Left | No | 2 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC and Effusion of middle ear | 0 dB | — |

| 4 | 4 | Famale | Right | Ear cleaning | 1 mo | Otalgia, suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 0 dB | — |

| 5 | 2 | Male | Left | No | 10 d | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 10 dB | — |

| 6 | 5 | Male | Right | No | 1 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | — | 10 dB |

| 7 | 5 | Famale | Left | No | 2 wk | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 0 dB | 15 dB |

| 8 | 4 | Famale | Right | No | 1 mo | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 0 dB | — |

| 9 | 9 | Famale | Left | No | 1 mo | Otalgia, Hemorrhagic | Mass in EAC | 5 dB | 5 dB |

| 10 | 3 | Male | Left | No | 3 wk | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 10 dB | — |

| 11 | 5 | Male | Right | No | 1 mo | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 10 dB | — |

| 12 | 1 | Male | Left | No | 3 wk | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 0 dB | — |

| 13 | 6 | Famale | Right | No | 2 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | — | 0 dB (PTA) |

| 14 | 3 | Famale | Right | No | 3 mo | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC and Effusion of middle ear | 5 dB | — |

| 15 | 7 | Famale | Left | No | 2 mo | Otalgia, suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 35 dB | 15 dB |

| 16 | 4 | Male | Right | No | 1 mo | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 25 dB | — |

| 17 | 5 | Male | Left | Water into EAC | 3 wk | Suppurative and Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 15 dB | — |

| 18 | 10 | Male | Left | No | 2 wk | Suppurative otorrhea | Mass in EAC | — | 5 dB (PTA) |

| 19 | 2 | Male | Right | No | 2 mo | Hemorrhagic otorrhea | Mass in EAC | 15 dB | — |

ABR, auditory brainstem evoked potentials.

All the measurements were performed using calibrated instruments in a soundproof room. Pure tone audiometry (PTA) measurements (air conduction: 0.125–8 kHz; bone conduction: 0.25–4 kHz, in 5-dB steps) were performed by experienced audiologists using a clinical audiometer. Air–bone gaps (ABGs) were calculated as the difference between the pure tone average of the three frequency thresholds at 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz (three frequency PTA). For children who were too young to cooperate with PTA examinations, auditory brainstem response testing was applied, and the ABGs were calculated at 2 kHz. Computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the temporal bone were used as imaging evidence before and after the operation.

FBGLPs were excised through the ear canal without an external incision, using a microscope or endoscope (Table 2). All granulomatous tissues were routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a mouse monoclonal antibody for CD68 (sc-17832; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), cleaved caspase-3 (Cat# 9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and Ki67 (sc-23,900; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to analyze granuloma proliferation, cell death, and giant cell reaction. Goat anti-mouse IgG/HRP (SE131; Solarbio, Beijing, China) and goat anti-rabbit IgG/HRP antibodies (SE134; Solarbio) were used as secondary antibodies.

TABLE 2.

Pathologic findings in patients with FBGLP

| No | Age (yr) | Hair Shafts | Calcium Deposition | Keratitic Precipitate | Cholesterol Crystal | Hemosiderin | Multinucleated Giant Cells | Granulation Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | + | + | + | ||||

| 2 | 6 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 3 | 3 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 4 | 4 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 5 | 2 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 6 | 5 | + | + | + | ||||

| 7 | 5 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 8 | 4 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9 | 9 | + | + | |||||

| 10 | 3 | + | + | + | ||||

| 11 | 5 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 12 | 1 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 13 | 6 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 14 | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 15 | 7 | + | ||||||

| 16 | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 17 | 5 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 18 | 10 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 19 | 2 | + | + | + | + | |||

| Sum | 9 | 12 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 18 | 14 | |

| Percentage | 47.4% | 63.2% | 73.7% | 26.3% | 15.8% | 94.7% | 73.7% |

Patients with characteristic pathologic structures were divided into three groups: normal tympanic mucosa, granulation tissue, and multinuclear giant cells (n = 3 in each group). The expression of Ki-67, cleaved caspase-3, CD68 was statistic analyzed of using analysis of variance. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS v20.0 software (IBM Corp. Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses.

The reporting guidelines for the appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature, acquired through the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research (EQUATOR) Network, were used to guide manuscript preparation (5).

RESULTS

Clinical Features

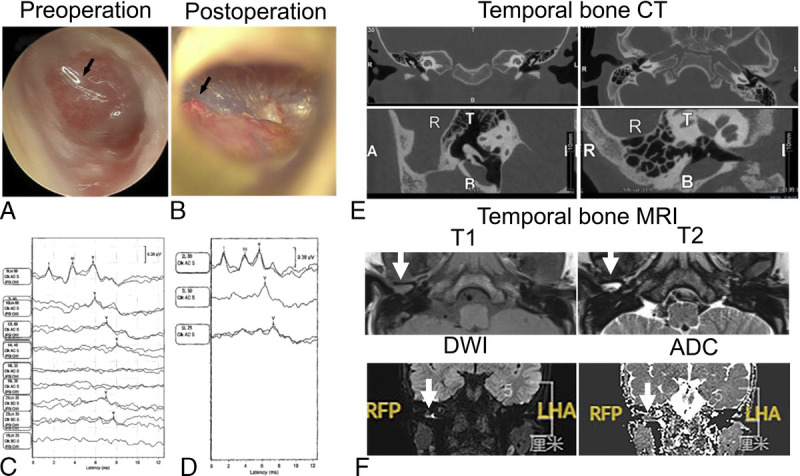

Based on the selection criteria, 19 children with FBGLP were included in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. All patients had an acute course of disease, lasting less than 3 months (median duration, 1 month). The most common symptom was suppurative otorrhea (57.9%, 11/19), followed by hemorrhagic otorrhea (42.1%, 8/19). The most common imaging finding on temporal bone CT (19/19) and MRI (3/19) (Fig. 2) was a soft mass blocking the EAC (100%, 19/19), with or without concomitant effusion in the middle ear (15.8%, 3/19). The granulomatous blockage caused slight hearing loss, with an ABG of less than 35 dB in 10 patients, whereas nine patients (47.4%, 9/19) had almost no ABG (ABG ≤ 5 dB).

FIG. 2.

Ear examination. (A) The preoperative endoscopic view of an FBGLP blocking the EAC. The arrow marks the granuloma. (B) Postoperative view after FBGLP excision under microscopy. The arrow marks the tiny root of the granuloma originating from the lateral process of the malleus. (C) Preoperative ABR testing results of a patient with FBGLP. (D) ABR testing result after the operation. (E) The coronal, axial section, and 3D reconstruction of temporal bone using CT shows a soft mass blocking the EAC, without bone erosion. (F) The axial section of the temporal bone MRI of the same patient shows a soft mass blocking the EAC with an abnormal long signal at T1 and T2 (white arrow). Diffusion-weighted imaging (b = 1,000) of the temporal bone MRI shows a high signal (white arrow), and the corresponding area in apparent diffusion coefficient imaging shows a low signal (white arrow). FBGLP, foreign body granuloma originating from the lateral process of malleus; ABR, auditory brainstem response.

Surgery and Follow-Up

The FBGLPs were excised through the EAC without an external incision, using an otologic microscope. During the operation, we found that the FBGLP had a tiny root supplied by a small vessel; therefore, trichloroacetic acid was administered after surgical excision. A 33% trichloroacetic acid paint was made by dissolving 330 g trichloroacetic acid in purified water to a total volume of 1000 mL. After granuloma removal, the trichloroacetic acid paint was applied to the bleeding root.

Otic drops containing levofloxacin and dexamethasone were administered three times daily after the operation. All 19 patients recovered (tympanic membrane healed and ABG < 5 dB) without recurrence during a follow-up ranging from 3 months to 4 years.

Pathologic Features

Microscopic examination of paraffin-based pathologic sections stained with H&E (Table 1 and Fig. 3), revealed foreign body granuloma, characterized by multinucleated giant cells (94.7%, 18/19), as well as granulation tissue with vascular hyperplasia and inflammatory cell infiltration (73.7%, 14/19). In addition, we found some microendogenous foreign bodies that might induce granuloma formation, such as keratotic precipitates (73.7%, 14/19), calcium deposition (63.2%, 12/19), hair shafts (47.4%, 9/19), cholesterol crystals (5, 26.3%), and hemosiderin (15.8%, 3/19) (Fig. 3; Table 2). Immunostaining of the normal tympanic mucosa and FBGLPs using Ki-67 showed that Ki-67 was not expressed in normal tympanic mucosa. However, a few Ki-67-positive cells (<5%) were found in FBGLPs, with no statistically significant difference (Fig. 4). On the other hand, cleaved caspase-3 and CD68 were not detected in the normal tympanic mucosa but were significantly increased in FBGLPs (p < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

H&E staining findings and statistical features. (A–I) H&E staining shows the characteristics of the histopathologic structure of FBGLPs. (A) Normal tympanic mucosa. (B) Foreign body granuloma with multinucleated giant cells. (C) Cholesterol crystal marked. (D) Granulation tissue with abundant blood vessels. (E) Longitudinal section of hair shafts. (F) Transverse section of hair shafts. (G) Hemosiderin. (H) Keratotic precipitate surrounded by multinucleated giant cells. (I) Calcium deposition. (J) Statistical proportion of various pathologic findings. The black arrow marks the corresponding structure. The magnification under the microscope is ×200.

FIG. 4.

Immunohistochemistry and statistical features. (A) Comparison of the expression and locations of Ki-67, cleaved caspase-3, CD68, in normal tympanic mucosa, granulation tissue, and multinuclear giant cells. (B) Statistic analysis of the expression of Ki-67, cleaved caspase-3, CD68, in normal tympanic mucosa, granulation tissue, and multinuclear giant cells (n = 3 in each group). The magnification under the microscope is ×200.

Preoperative routine examination of blood analysis showed no obvious abnormality or manifestations of systemic infection. There were also no infective symptoms, such as fever or cough. Chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. Combined with negative acid-fast staining and negative periodic acid–Schiff staining (Supplemental Figure, http://links.lww.com/MAO/B659), the possibility of tuberculosis- and fungus-induced infectious granuloma was excluded.

DISCUSSION

A granulomatous mass in the EAC may arise from the external ear, middle ear, or adjacent structures, indicating etiologic differences associated with numerous pathologies, such as exostosis, osteoma, and a granulomatous mass. In our study, we analyzed the clinical data of 19 patients with FBGLP. The most distinctive findings were multinucleated giant cells, followed by granulation tissue, characterized by vascular proliferation representing the repair process. Multinucleate or Langerhans giant cells are often observed around the foreign body, which isolates healthy tissue from materials that cannot be removed by the immune system (6), accompanied by increased cell death (labeled by cleaved caspase-3) and slow cell growth (labeled by Ki-67). In children’s ears, foreign bodies, such as jewelry, beans, paper products, pens and pencils, and other materials are commonly encountered by otolaryngologists (7,8). However, no macroscopic foreign body was found in the EACs of our patients with FBGLP. We, thus, further examined the FBGLP sections to explore the pathogenic factors. We found endogenous foreign-like particles in the ear, including keratotic precipitates, calcium deposits, and hair shafts, which had been altered in some way and could be considered as foreign bodies by histiocytes, resulting in the formation of foreign body granulomas (9). This might be one of the factors that induce FBGLP.

In our study, FBGLP mainly occurred during an acute course (10 days to 3 months), and all included patients were children (100%, 19/19). Our study population included only two adults, who were excluded owing to loss to follow-up after granuloma excision, whereas we encountered 19 children with this condition. This may be due to the children’s relatively straight and narrow EAC, which induces poor self-cleaning and self-healing abilities. Keratin and other endogenous foreign bodies are difficult to degrade; therefore, if they remain in the EAC, they stimulate and damage the surface of the tympanic membrane, which further induces giant cell reactions. Interestingly, FBGLP may be related to the unique anatomic structure of the lateral process of the malleus. Anatomically, the lateral process of the malleus is prominent and forms the boundary between the pars flaccida and the pars tensa. The pars tensa of the tympanic membrane consists of three layers: the epithelium, the fibrous, and the mucosal layers. However, the lateral process of the malleus lacks a fibrous layer, which makes it more susceptible to foreign body stimulation and skin damage leading to subsequent inflammation or exudation. Furthermore, the blood supply and innervation are relatively abundant in this region, which facilitates formation of vascularized granulomas.

Clinically, foreign body granulomas present in the EAC should be distinguished from other types of granulomas. Granular myringitis, also called chronic myringitis, myringitis granulosa, granulomatous myringitis, granulating myringitis, and granular external otitis is an uncommon inflammatory disorder of the tympanic membrane. It is characterized by chronic, painless otorrhea with blocked epithelialization and granulation tissue formation over the involved area (10). Etiologically, nonspecific injury of the tympanic lamina propria induces hyperplasia of the granulation tissue, which may disturb epithelial migration. In addition, granulomas of the EAC, such as outer or middle ear inflammation, cholesteatoma, and childhood malignant tumors, can be the first sign of various etiologies. Deep ear lesions are easily ignored due to a granuloma blocking the EAC; therefore, timely imaging examination is necessary to determine the extent of the lesion. If required, biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Severe complications were absent in patients with FBGLP, although the middle ear mastoid occasionally showed inflammation without bone destruction. This is different from secondary granulomas with primary lesions, such as cholesteatoma, chronic suppurative otitis media, and tumors. In addition, most of FBGLPs occurred during the acute course, and no recurrence was observed after surgical removal. We found that FBGLPs had a tiny root, supplied by a small vessel; therefore, FBGLPs could be completely excised through the EAC without requiring an external incision. By proper preoperative differential diagnosis and assessment, otolaryngologists can make the best selection for surgery.

There were a few inherent limitations to this study. Clinicopathologic data were collected during a 4-year period, and some cases may have had incomplete specimen data. Furthermore, the small dataset size implied that it was impossible to demonstrate all the features and etiology of FBGLPs. Therefore, further investigations with more patients are required.

CONCLUSIONS

FBGLP is caused by endogenous foreign-like particles in the ear. The trans-external auditory meatus approach for surgical excision without requiring external incision is recommended, as it yields promising outcomes. These results provide a clinical basis for the prevention and treatment of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the invaluable cooperation and participation of the patients.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31700894, 81670932, 81970873, 81900938). This work was supported by Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (CN) (2017CXGC1213, 2017GSF221001), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2015HQ006, ZR2020MH178).

Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Contributor Information

Yanyan Mao, Email: 61983157@qq.com.

Li Li, Email: honey-ly@126.com.

Wenqing Yan, Email: 402124358@qq.com.

Yanqing Lu, Email: 709548825@qq.com.

Wei Li, Email: 623923616@qq.com.

Jinfeng Zheng, Email: zjfmsf@163.com.

Zhaomin Fan, Email: fanent@126.com.

Haibo Wang, Email: whbotologic797@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the role of the granuloma in tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:352–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagan AJ, Ramakrishnan L. The formation and function of granulomas. Annu Rev Immunol 2018;36:639–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahn AF, Hawke M. Foreign body granulomas of the ear. J Otolaryngol 1976;5:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris KC, Conley SF, Kerschner JE. Foreign body granuloma of the external auditory canal. Pediatrics 2004;113:e371–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempen JH. Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:7–10.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin A. Weedon's Skin Pathology. In: The granulomatous reaction pattern. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010:169–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao CC, Kshirsagar RS, Rivero A. Pediatric foreign bodies of the ear: a 10-year national analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020;138:110354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueiredo RR Azevedo AA Kós AO, et al. Complications of ENT foreign bodies: a retrospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2008;74:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin 2015;33:497–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devaraja K. Myringitis: an update. J Otolaryngol 2019;14:26–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]