Lessons learned from COVID-19, HIV, and syphilis contact tracing programs in San Francisco offer insights into strategies for increasing disease intervention workforce capacity and opportunities to maximize the impact of outbreak response.

Abstract

Contact tracing is a core public health intervention for a range of communicable diseases, in which the primary goal is to interrupt disease transmission and decrease morbidity. In this article, we present lessons learned from COVID-19, HIV, and syphilis in San Francisco to illustrate factors that shape the effectiveness of contact tracing programs and to highlight the value of investing in a robust disease intervention workforce with capacity to pivot rapidly in response to a range of emerging disease trends and outbreak response needs.

Contact tracing (CT) is a long-standing public health intervention for communicable diseases, including tuberculosis, syphilis, and HIV, in which the goal is to quickly identify and manage persons exposed to disease to prevent ongoing transmission and decrease morbidity.1,2 Although CT programs have existed for decades, the COVID-19 response put CT in the spotlight, as isolation, quarantine, and other nonpharmaceutical interventions were the only available tools to mitigate spread in the prevaccine and pretreatment era. Early in the COVID-19 response, several countries signaled CT's success in containing the spread of COVID-19, although published evidence foreshadowed potential challenges to interrupting transmission chains due to high transmissibility before symptom onset and a short incubation period.3 For an often-ignored public health strategy, the influx of resources and attention to CT was overdue; however, implementation proved difficult without a robustly trained workforce or supporting technological infrastructure.4,5

In April 2020, San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) became one of the first local health departments in the United States to scale a COVID-19 CT program. The CT program was built on the foundational knowledge from syphilis and HIV CT and used new financial and human resources to rapidly train more than 500 city, state, and contract staff.6 Given backlogs created during surges and difficulty identifying contacts, several strategies were implemented to optimize the program's operational effectiveness. As the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus evolved to have a shorter incubation period and widespread vaccine availability facilitated societal reopening, the feasibility of using universal CT as a means of stopping spread of disease dramatically declined.

Although CT is no longer a core strategy for COVID-19 mitigation, there is a renewed recognition that skilled and scalable CT programs are an important component of public health infrastructure.7–9 New federal investments seek to expand disease intervention (DI) workforce capacity, evidenced by 1 billion dollars of supplemental federal funding provided to health departments through the Strengthening STD Prevention and Control for Health Departments cooperative agreement.10 To fully realize the potential of these resources, public health leaders overseeing CT programs must build on best practices. Here, we present lessons learned and novel strategies implemented by SFDPH from COVID-19, HIV, and syphilis—3 conditions that have used CT as a core intervention strategy—to illustrate common themes shaping and reshaping CT program success over time.

THE WHY: ESTABLISHING THE GOALS OF CT AND HOW THEY WILL CHANGE OVER TIME

Simply put, the goals of CT include (1) preventing transmission and/or decreasing morbidity, (2) understanding disease transmission or epidemiology, and (3) linking at-risk persons to public health interventions. Given that outbreaks will evolve over time, the goals of CT will also change. Figure 1 provides a framework of how DI goals may shift with increased disease burden and morbidity. Early in an outbreak of a known or novel pathogen, CT interventions may focus on identifying infected contacts to contain disease transmission. If containment becomes impossible because of widespread disease or an inability to intervene in a timely fashion, CT goals may shift to case finding. If finding undiagnosed cases becomes challenging because the disease is either too widespread to control or too rare to detect, efforts may be redirected toward linking cases and contacts to preventive services. For example, it is well understood that the goals of HIV CT extend beyond case finding to linking persons to HIV treatment or to HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).11,12 During the COVID-19 response, DI goals shifted as COVID-19 epidemiology and morbidity changed over time. Recognizing that CT goals are expected to evolve based on local epidemiology enables public health leadership, policy makers, and the CT workforce to more readily shift priorities as needed and ensure meaningful metrics of success.13,14 To manage expectations, public health leaders could articulate the goals of CT from the outset and track program metrics and effectiveness over time to keep stakeholders informed as an outbreak evolves.

Figure 1.

As disease burden and morbidity changes, disease intervention goals will change.

THE WHO: BUILD THE CT WORKFORCE

HIV and Syphilis

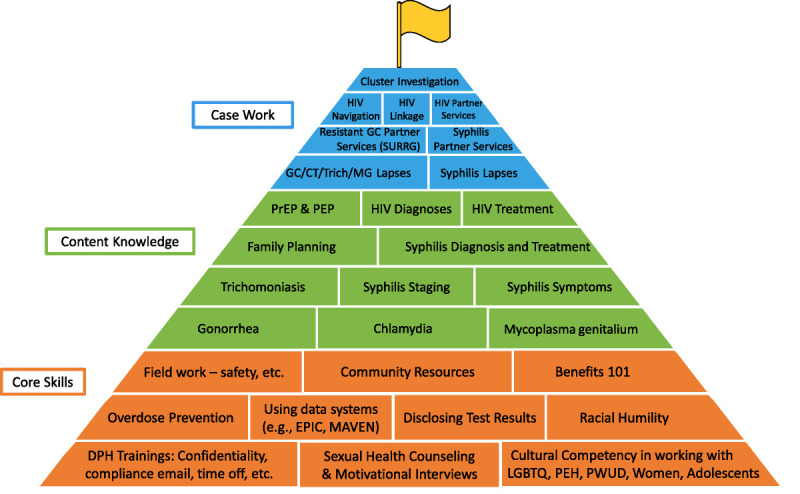

The success of any CT program is dependent on developing and retaining a trained and skilled workforce. Rising syphilis rates, the reemergence of congenital syphilis, increasing housing instability among cases, and overall lack of patient engagement with HIV/STI partner services (PS) have made it harder to identify sexual partners and intervene on disease transmission in recent years.15 In 2019, qualitative interviews conducted among SFDPH disease intervention specialists (DISs) demonstrated the multifaceted skill-set DIS need to perform effectively within their role (Fig. 2).16 The “pyramid-of-learning” illustrates the knowledge base, range, and complexity of DIS work across multiple conditions (Fig. 3). Recognizing the need for more robust training for HIV/syphilis CT, SFDPH allocated funding to hire dedicated trainers, built an online learning management system, standardized observation and feedback techniques, and offered therapeutic counseling services to support staff who serve a highly traumatized patient population.

Figure 2.

A successful DIS needs to call upon on a multifaced skill set.

Figure 3.

Pyramid-of-learning approach for DIS training and capacity building. The pyramid highlights both foundational skills and disease-specific content knowledge necessary for DIS to successfully deploy disease intervention strategies. Colors represent related content modules within each section.

COVID-19

While building on the HIV/syphilis CT framework, the SF COVID-19 response required a different approach to rapidly scale and train a DIS workforce. Given the urgency to reopen society in March 2020, estimations of SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility and potential number of contacts named per case led to CT staffing targets.17 To meet projected needs, SFDPH activated city staff who were otherwise unable to perform their regular duties because of shelter-in-place orders, as well as state and contract staff, to launch a CT team in April 2020.18,19 In contrast to the months of shadowing required before newly hired HIV/STI DIS conduct their own investigations independently, COVID-19 CT staff, often without any prior public health experience, were rapidly trained and retrained on evolving CT protocols. Given that a majority of early COVID-19 cases in San Francisco were monolingual Spanish-speaking persons, funding was allocated to hire bilingual staff, who made up nearly a quarter of SFDPH's CT workforce by Fall 2020.6,20 The overall impact of this rapid workforce scale-up on CT outcomes (e.g., number of contacts named and successfully notified per case) is challenging to evaluate, but vast differences in these outcomes by program area likely reflect varying implementation and operational effectiveness.21 Taking these lessons learned, infectious disease preparedness efforts should seek to train a reserve of public health staff who are familiar with CT protocols and systems and can be rapidly deployed to respond to emerging outbreaks.

THE WHAT: INCREASE ENGAGEMENT BY LINKING TO SERVICES

HIV and Syphilis

Disease intervention specialists are charged with locating persons newly diagnosed with infection to notify them of their positive status and quickly build rapport, while conducting an interview to better understand individual exposure, onset of signs and symptoms associated with infection, and testing and treatment history. Syphilis CT involves DIS not only identifying sexual partners potentially exposed to the case while they were infectious (i.e., forward-tracing), but also seeking out the source of the case's infection (i.e., back-tracing), to identify individuals more likely to have transmitted disease (“super-spreaders”) and facilitate testing of additional contacts. Back-tracing is notoriously challenging in practice because of recall bias and difficulty determining when persons without symptoms acquired infection.22 Despite these challenges identifying transmission sources, CT also offers an opportunity for DIS to link cases and contacts to various important resources, including HIV/STI testing and treatment, pregnancy care or contraceptive services, and HIV PrEP.

COVID-19

COVID-19 CT efforts by SFDPH focused on forward-tracing, given the logistical challenges of back-tracing respiratory exposures and limited value of identifying potential sources for a disease with a short incubation period. By May 2020, COVID testing was offered to all contacts in SF at the beginning and end of quarantine. However, it remained challenging to measure the effectiveness of CT on preventing transmission because of inconsistent testing of contacts and limited ability to ascertain adherence to quarantine.21

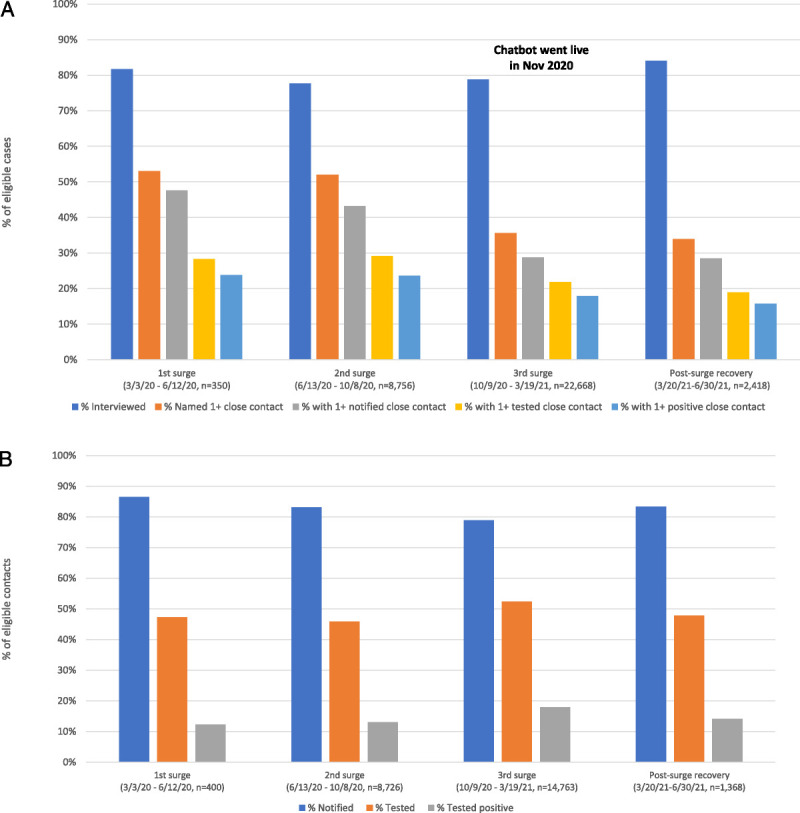

Nevertheless, a strength of SFDPH's COVID-19 CT workforce was the ability to offer services to highly impacted communities.23,24 In addition to offering grocery deliveries and cleaning supplies, city leadership advocated for financial compensation for persons diagnosed with COVID-19 who lacked sick leave. The availability of these supportive resources likely contributed to high response rates to CT calls, with nearly 80% of cases and contacts completing an interview during the CT program's first year (Figs. 4A, B).4,5,25

Figure 4.

A, Investigation outcomes among eligible COVID-19 cases* by Epi Surge Period. *Eligible case defined as a patient with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 reported within 10 days of specimen collection. B, Investigation outcomes among eligible contacts† to COVID-19 cases by Epi Surge Period. †Eligible contact defined as a person without COVID-19 in the past 90 days, who had close contact with a COVID-positive individual during that person's infectious period.

THE WHEN: IDENTIFY AND MINIMIZE DELAYS BETWEEN CASE IDENTIFICATION AND OUTREACH

HIV and Syphilis

A prerequisite of successful CT intervention is that there is enough time between the contact's exposure to a case and the contact becoming infectious (i.e., incubation period) to allow for infected contacts to be provided public health recommendations to prevent onward transmission. Figure 5 illustrates how incubation periods differ by diseases, impacting CT utility and implementation. For example, syphilis is well suited for DI owing to its long incubation period (10–90 days), during which adequate treatment can eradicate the infection; similarly, the lengthy infectious period for HIV makes CT a meaningful intervention for not only case finding but for linking to HIV care, treatment, or PrEP. In contrast, infections with shorter incubation periods (e.g., gonorrhea) may not allow for enough time for universal CT efforts to prevent transmission.

Figure 5.

The When—The Disease Intervention Window informs the overall utility and impact of contact tracing to prevent ongoing transmission.

COVID-19

In contrast to syphilis, COVID-19’s incubation period is only 2 to 5 days. With such a narrow window to reach infected contacts, SFDPH attempted to optimize several steps after exposure where lags could impact CT efforts, including the time from symptom onset to test, turnaround time of test results (particularly reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction), laboratory/provider reporting delays, time to case assignment and outreach, and time to successfully identify and notify contacts. Nevertheless, early evaluation of SFDPH CT data found an average of 6 days between when a case was initially infectious and contact notification about quarantine.5,26

The SFDPH then explored opportunities to minimize the time between case identification and quarantine of contacts. In January 2021, SFDPH partnered with a community-based rapid testing site to offer immediate CT services to newly diagnosed persons.27 Compared with cases identified through laboratory-based reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, the median time from specimen collection to case interview decreased from 4 days to 1 day for cases detected through rapid testing. Still, the lack of automated systems to facilitate immediate reporting of rapid antigen test results to the health department complicated routine prioritization of such cases. Innovating data systems that support timely reporting of rapid test results may improve CT timeliness and effectiveness.

THE WHERE: ASSURE CAPACITY FOR MOBILE, FIELD-BASED SERVICES

HIV and Syphilis

Even the most seasoned DIS experiences challenges locating cases and contacts. Public health authorities are notified of cases via mandatory laboratory or provider reports, which are often missing necessary locating information and patient demographics. If DIS can successfully locate persons, DIS-patient interactions have historically been face-to-face, to establish trust and rapport. In the modern era, initial DIS outreach efforts are increasingly made over the telephone; yet, shifting social norms of not answering or blocking unknown or perceived “spam” numbers, as well as ongoing stigma related to STI/HIV infection, reduce the likelihood that cold calls from DIS will be well received.15 The growing proportion of newly infected persons diagnosed with syphilis and HIV who are experiencing homelessness and report substance use further emphasizes the ongoing importance of a trauma-informed workforce that can meet people in their communities, despite the time investment and cost involved.28,29 Programs must realistically be prepared to use both CT outreach approaches and adjust outcome expectations, depending on case volume, staffing resources, and emerging needs of its most vulnerable populations.

COVID-19

Mirroring successful efforts to offer immediate antiretroviral therapy and wrap-around services to persons newly diagnosed with HIV in SF, the University of California San Francisco piloted a COVID-19 “Test-to-Care” model, in which persons with rapid SARS-CoV-2–positive test results were offered key DIS services via multiple in-person home visits, including health education, home deliveries of material goods to facilitate safe isolation and quarantine, and longitudinal clinical and social support. In 20% of households visited, more contacts than initially reported were identified; in addition, program staff were able to ascertain adherence to isolation and testing recommendations.30 Cost analyses would help programs better understand the public health impact of this strategy by estimating the financial and human resources required to operationalize this intensive approach.

THE HOW: ADAPTIVE PRIORITIZATION OF CT MAXIMIZES EFFICIENCY AND IMPACT

HIV and Syphilis

Although the traditional CT goal for HIV/syphilis is to identify and treat contacts to prevent onward disease transmission, in San Francisco, the proportion of cases naming contacts decreased from 62.9% in 2000 to 2004 to 31.7% in 2010 to 2016.12 A multisite evaluation of early syphilis cases in 7 US jurisdictions estimated that 75% to 85% of partners were unnamed and consequently unreached through CT efforts.31s Qualitative interviews conducted in SF in 2019 among men having sex with men (MSM) diagnosed with syphilis suggested multiple reasons for low PS engagement, including the inability to provide locating information for partners met via geosocial network applications and a strong culture among MSM to self-notify partners.16 Attempts to increase case finding by eliciting and locating social and sexual contacts of people initially identified as contacts have not been shown to improve outcomes.32s

Recognizing the reduced likelihood of engagement among MSM, SF sought to prioritize DI for persons most likely to identify contacts and those with the highest infection-associated morbidity. Since 2017, the number of cis-women diagnosed with syphilis in SF has increased nearly 200%, mirroring large increases across California. In response to this epidemiologic shift, SFDPH pivoted priorities to focus on women of reproductive age diagnosed with syphilis. High-intensity activities included syphilis treatment and pregnancy status verification, partner testing and treatment, and linkage to prenatal care.

COVID-19

Taking lessons learned from syphilis prioritization efforts, SFDPH adopted an equity-focused, tiered CT strategy to address COVID-19 backlogs during surges that outpaced CT staffing resources. Cases living in priority zip codes (defined by high test positivity and case rates) were prioritized for telephone outreach. All other cases were sent an automated, interactive chatbot (i.e., “virtual agent”) via CalConnect, California's statewide COVID case management and CT platform.33s The automated chatbot included a unique link via text message in either English or Spanish. Once birthdate and zip code were confirmed, participants were texted educational information on their isolation period, as well as a survey on their symptoms, affiliation with congregate settings, demographics, close contacts, and ability to isolate. The average time between case receipt of a chatbot message and case reply was 26 minutes. Using these data, SFDPH could readily identify and prioritize newly diagnosed cases who needed support to safely isolate.34s Although fewer contacts were elicited through the chatbot compared with case interviews conducted by trained staff (Fig. 4A), nearly 90% of Latinx persons diagnosed with COVID-19 received a CT telephone call during the Winter January 2021 surge; greater than 60% of COVID-19 cases were reached overall.

Further prioritization occurred during the Delta and Omicron variant surges in 2021. During the Delta surge (July–August 2021), SFDPH scaled back CT to focus on unvaccinated cases and contacts, in keeping with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance that vaccinated persons with COVID-19 did not need to isolate. This effort was facilitated by an automated match of contact information against the immunization database. During the Omicron surge (December 2021), SFDPH halted all individual-level CT and redirected response efforts to prevent outbreaks in high-risk congregate settings, including long-term care facilities, homeless shelters, and schools.35s,36s Overall, the proportion of contacts testing positive was relatively stable throughout multiple COVID waves from March 2020 to June 2021 (12%–18%; Fig. 4B).

CONCLUSIONS

The effectiveness of CT intervention has many dependencies, some of which can be influenced by improving the operationalization of CT programs (i.e., robust training and adaptive prioritization) and others that may not be changed (i.e., incubation period of the pathogen). Although health department expertise in STI/HIV DI established the foundation for many COVID-19 CT programs, the rapid infusion of human and financial resources allowed programs to innovate and scale faster than ever imagined. In addition, there were clear calls to build relationships and trust with community members by ensuring newly hired staff reflected populations disproportionately impacted by disease. To identify opportunities to optimize CT programs, it is critical to have well-resourced supervisory staff and data systems that can evaluate program data in subpopulations. Technological advancements, such as chatbots and integration of surveillance and case management systems, offer opportunities for increased automation, improved data collection, and communication with large population groups that limited public health resources otherwise miss.

With any CT intervention, there are several ethical concerns to consider. Although the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act permits public health programs to disclose protected health information in the context of CT activity (i.e., disclosure to persons potentially exposed to syphilis, HIV, and COVID), programs are still responsible for the protections of individual privacy and confidentiality. New technologies that support CT efforts should not necessarily replace but rather be used in conjunction with other CT and outreach strategies that ensure autonomy to opt in or out of participation, as well as equitable provision of and access to sexual health information, prevention, screening, and treatment.

There is increasing interest in using information collected through genomic surveillance to better understand patterns of transmission and clusters of disease.37s However, slow processing of specimens and disjointed reporting systems make it nearly impossible to realize this possibility in the near future.38s Nevertheless, genomic surveillance could play a role in understanding transmission chains and informing prioritization of public health interventions, particularly for emerging infections.

Undoubtedly, field work will always have a role in providing social and environmental context for disease transmission, building trust with communities, and offering an entry point for patients into other health interventions. Although the public spotlight on CT programs has drifted, there remains an immense opportunity to build on lessons learned over the last decade of CT work. As public health confronts old and new infectious disease outbreaks, thoughtful reflection on the purpose (i.e., the why) of CT is a critical first step to realizing the full potential of CT to intervene on disease transmission and promote health equity.

For further references, please see “Supplemental References,” http://links.lww.com/OLQ/A893.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Kimberly Koester and Shana Hughes for their essential role in developing the DIS Qualities Model; Kelly Johnson, Kristen Wendorf, and Anna Cope for their support in manuscript review; and Joshua Bunao for editing support.

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding: None declared.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://www.stdjournal.com).

Contributor Information

Rilene A. Chew Ng, Email: rilene.ng@cdph.ca.gov.

Katherine Hernandez, Email: katherine.hernandez@sfdph.org.

Trang Quyen Nguyen, Email: trang.nguyen@sfdph.org.

Stephanie E. Cohen, Email: stephanie.cohen@sfdph.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hogben M Collins D Hoots B, et al. Partner services in sexually transmitted disease prevention programs: A review. Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43(2 Suppl 1):S53–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for the Investigation of Contacts of Persons with Infectious Tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5415a1.htm. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- 3.Gao W Lv J Pang Y, et al. Role of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infections in COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2021; 375:n2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lash RR Moonan PK Byers BL, et al. COVID-19 case investigation and contact tracing in the US, 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2115850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdev DD Brosnan HK Reid MJA, et al. Outcomes of contact tracing in San Francisco, California—Test and trace during shelter-in-place. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:381–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid M Enanoria W Stoltey J, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: The race to trace: contact tracing scale-up in San Francisco—Early lessons learned. J Public Health Policy 2021; 42:211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case Investigation and Contact Tracing for COVID-19 in the Era of Vaccines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5415.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- 8.Prioritizing Case Investigation and Contact Tracing for COVID-19. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/contact-tracing-plan/prioritization.html#:~:text=It%20is%20important%20to%20prioritize,to%20someone%20with%20COVID%2D19. Accessed March 31, 2022.

- 9.Joint Statement: Public Health Agencies Transitioning Away from Universal Case Investigation and Contact Tracing for Individual Cases of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/joint-statement-public-health-agencies-transitioning-away-from-universal-case-investigation-and-contact-tracing-for-individual-cases-of-covid-19. Accessed March 31, 2022.

- 10.CDC DIS Workforce Development Funding. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/funding/pchd/development-funding.html. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- 11.Golden MR AugsJoost B Bender M, et al. The organization, content, and case-finding effectiveness of HIV assisted partner services in high Hiv morbidity areas of the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2022; 89:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen TQ Kohn RP Ng RC, et al. Historical and current trends in the epidemiology of early syphilis in San Francisco, 1955 to 2016. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45(9S Suppl 1):S55–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golden MR, Katz DA, Dombrowski JC. Modernizing field services for human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections in the United States. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44:599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman RA Katz DA Levin C, et al. Sexually transmitted disease partner services costs, other resources, and strategies across jurisdictions to address unique epidemic characteristics and increased incidence. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46:493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cope AB Mobley VL Samoff E, et al. The changing role of disease intervention specialists in modern public health programs. Public Health Rep 2019; 134:11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koester K Hughes S, et al. “Can you talk now?” Disease intervention specialist & client perspectives on syphilis. CDC STD Prevention Conference 2020, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.COVIDTracer Advanced. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/COVIDTracerTools.html. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- 18.Celentano J Sachdev D Hirose M, et al. Mobilizing a COVID-19 contact tracing workforce at warp speed: A framework for successful program implementation. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021; 104:1616–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golston O Prelip M Brickley DB, et al. Establishment and evaluation of a large contact-tracing and case investigation virtual training academy. Am J Public Health 2021; 111:1934–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eliaz A Blair AH Chen YH, et al. Evaluating the impact of language concordance on coronavirus disease 2019 contact tracing outcomes among Spanish-speaking adults in San Francisco between June and November 2020. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 9:ofab612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachdev DD, Cohen SE, Scheer S. Factors contributing to missing COVID-19 cases during contact tracing—Reply. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller J, Kretzschmar M. Forward thinking on backward tracing. Nature Physics 2021; 17:555–556. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainisch G Jeon S Pappas D, et al. Estimated COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations averted by case investigation and contact tracing in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5:e224042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VCAmon—Computer Application for VCA Plotting. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/program/vca/default.htm. Accessed April 8, 2022.

- 25.Lash RR Donovan CV Fleischauer AT, et al. COVID-19 contact tracing in two counties—North Carolina, June–July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1360–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio LA Peng J Rojas S, et al. The COVID-19 symptom to isolation cascade in a Latinx community: A call to action. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilarowski G Marquez C Rubio L, et al. Field performance and public health response using the BinaxNOWTM rapid severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antigen detection assay during community-based testing. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e3098–e3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams SP, Bryant KL. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence among homeless adults in the United States: A systematic literature review. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45:494–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu CY, Chai SJ, Watt JP. Communicable disease among people experiencing homelessness in California. Epidemiol Infect 2020; 148:e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerkhoff AD Sachdev D Mizany S, et al. Evaluation of a novel community-based COVID-19 ‘Test-to-Care’ model for low-income populations. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0239400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]