Abstract

The effects on the quality of loin ham from using wet-aging with a commercial refrigerator (CR) and with a pulsed electric field system refrigerator (PEFR, at 0 and − 1 °C) were compared. The CR sample recorded an increased cooking loss alongside a decrease in color stability and shear force. In contrast, the samples using PEFR observed improved color stability, water holding capacity, and weight loss. In electronic nose analysis, wet-aging samples were shown to be significantly different from raw meat samples, however, the use of PEFR did not significantly affect the flavor. In electronic tongue analysis, wet-aging was observed to increase the umami of the loin ham, whilst the PEFR − 1 °C sample showed the highest umami. In sensory evaluation, the PEFR 0 °C sample showed significantly higher overall acceptability than raw meat. Conclusively, the application of wet-aging with PEFR in the manufacturing of loin ham led to an improvement in quality.

Keywords: Pulsed electric field, Wet-aging, Cured ham, Pork loin, Quality

Introduction

Aging is a technique used to enhance meat quality by increasing the unique flavors and softness. As a result, this is used in the commercial manufacturing of high-quality products (Mungure et al., 2020). Meat aging is performed using a variety methods, with the wet-aging method in particular being widely used in the aging of meat considering the low level of weight loss and simple storage and transport it offers compared with other methods (Bischof et al., 2021). The wet-aging of meat results in flavor compounds such as free amino acids, inosine monophosphate (IMP), and guanosine monophosphate (GMP), formed from the degradation of proteins and nucleotides (Xu et al., 2021). The aging of meat also improves a soft texture, as the myofibril proteins are degraded by proteases, which may then enhance the overall acceptability (Kim et al., 2018). Thus, the wet-aging of meat is recommended in the manufacturing of high-quality meat products for facilitated application in various industrial conditions and for the potential improvements it offers for meat quality in terms of taste and softness.

Pulsed electric field (PEF) is another widely used technique in the meat industry that increases shelf-life and enhances flavor (Gómez et al., 2019; Mungure et al., 2020). In the aging of meat, PEF can facilitate the release of Ca2+ to activate proteases such as calpain, which subsequently degrades myofibril, thereby reducing the meat aging period (Alahakoon et al., 2016). The use of PEF could also led to the increased absorption of additives used in meat product manufacturing through the partial degradation of muscle tissues and the mass transfer of ions across muscle cells, which is known to increase the level of additives and reduce processing time (Gómez et al., 2019). Therefore, the use of PEF in meat aging and meat product manufacturing is anticipated to contribute to the improvement of processing efficiency.

Cured ham is a common cured meat product that is consumed around the globe (Tamm et al., 2016). Curing is a meat treatment technique that uses salt to facilitate the dissolution of salt-soluble proteins in meat to enhance the flavor and yield (Pancrazio et al., 2016). In the production of cured ham, a curing solution is prepared and the mechanical processes of injection and tumbling are applied to ensure the curing solution is uniformly dispersed inside the meat. During tumbling, myofibril proteins are extracted, dissolved, and degraded, leading to the enhanced physical properties of cured ham (Li et al., 2011; Pancrazio et al., 2016). However, tumbling can require several hours of processing time depending on the product type, due to the characteristic use of the preserved form of muscle tissue in the curing process for ham manufacturing (Pancrazio et al., 2016). Hence, it is necessary to improve the temporal and economic factors in meat processing that involves tumbling to enhance meat texture.

Applying the wet-aging of meat prior to the production of cured ham is predicted to enhance meat quality properties that rely on protein degradation, such as taste and softness. Furthermore, the combined use of a PEF system is likely to bring about an additional positive effect on the softness and increased absorption of additives. Thus, in this study, cured pork loin ham was produced with a PEF system using wet-aged pork loin, and the physicochemical and sensory qualities of the produced loin ham were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kongju National University (Authority No: KNU_IRB_2022-083).

Manufacturing wet-aging and cured pork loin ham

Left loin (Longissimus thoracis et lumborum) of pig carcass 24 h after slaughter was obtained from Ihome meat (Seoul, Korea). Wet-aging was performed in three batches, and three pork loins were used in each batch according to different wet-aging conditions. The pork loin was then divided into three parts and cut into 15 × 9 × 5 cm (length × width × height) slices, with an average weight of 619.83 ± 10.52 g (n = 27). Each pork loin piece was vacuum-packed using a vacuum packaging machine (C 15-HL, Webomatic, Bochum, Germany). These vacuum-packed samples were then aged in a commercial refrigerator (CR; CA-H17DZ, LG, Seoul, Korea; temperature 4 ± 1 °C, wind speed 5 ± 3 m/s) and a pulsed electric field system refrigerator (PEFR; ARD-090RM-F, Mars, Fukushima, Japan; temperature 0 ± 0.1, − 1 ± 0.1 °C, wind speed 5 ± 2 m/s, electric field strength 0.58 kV/cm, voltage 7 kV, frequency 60 Hz, electric current 5 mA, pulse width 20 μs). The PEFR consisted of two parallel stainless-steel electrodes, and the myofibril direction of the vacuum-packed samples was placed parallel to the electrodes. As for the wet-aging period, 2 weeks of CR, 3 weeks of PEFR 0 °C, and 4 weeks of PEFR − 1 °C, which received the highest evaluation in the sensory evaluation performed in previous studies, were selected (terminated wet-aged; CR for 3 weeks, PEFR 0 °C for 5 weeks, PEFR − 1 °C for 9 weeks; data are not shown). In addition, the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS, mg MDA/kg), volatile basic nitrogen (VBN, mg/100 g), and total plate count (TPC, log CFU/g) results of each sample in previous studies complied with storage stability, and the results are as follows; TBARS was CR: 0.22 ± 0.01, PEFR 0 °C: 0.21 ± 0.01, PEFR − 1 °C: 0.21 ± 0.01; VBN was CR: 3.74 ± 0.32, PEFR 0 °C: 3.17 ± 0.28, PEFR − 1 °C: 2.99 ± 0.32; and TPC was CR: 5.67 ± 0.30, PEFR 0 °C: 3.25 ± 0.40, PEFR − 1 °C: 3.74 ± 0.16.

The cured pork loin ham (loin ham) used in this study was prepared as described by Choe and Kim (2019). Loin ham was divided into three independent batches, and loin ham samples were classified according to wet-aging conditions as follows: Raw meat (unaged fresh control), CR (wet-aged at 4 °C for 2 weeks), PEFR 0 °C (wet-aged with PEFR at 0 °C for 3 weeks), and PEFR − 1 °C (wet-aged with PEFR at − 1 °C for 4 weeks). For each condition, a pork loin sample measuring 15 × 9 × 5 cm (length × width × height) was prepared (n = 36). The curing solution was prepared by mixing 80% water, 12% nitrite pickled salt (salt:nitrite = 99.4:0.6), and 8% sugar. A curing solution 20% of the weight of the prepared sample was then injected using an injector (PR8, RÜHLE GmbH, Grafenhausen, Germany). Subsequently, the samples were placed into plastic bags and tumbled for 120 min with a tumbler (BVBJ-40, Thematec, Gyeonggi, Korea). After tumbling, cured samples were stored at 4 °C for 24 h. Then, samples were heated in an 80 °C chamber (10.10ESI/SK, Alto Shaam, Menomonee Falls, WI, USA) for 1 h until their core temperature reached 70 °C. The completed loin ham samples were then left to cool at room temperature (20 °C) for 30 min, and finally stored at 4 °C until the experiment was performed.

Proximate compositions

The moisture content (AOAC-925.10), protein content (AOAC-960.52), fat content (AOAC-2003.05), and ash content (AOAC-923.03) of the proximate compositions of the samples were measured and calculated by converting according to AOAC (2005).

pH

After cooking, 4 g of sample and 16 mL of distilled water were mixed and homogenized at 6451×g for 1 min using ultra-turrax (HMZ-20DN, Poonglim Tech, Korea). The homogenate was then measured with a glass-electrode pH meter (model S220, Mettler-Tolede, Schwer-zenbach, Switzerland). The glass electrode pH meter was calibrated at 22 °C using buffer solutions of pH 4.01, pH 7.00, and pH 10.00 (Suntex instrument co. ltd, New Taipei City, Taiwan).

CIE color, chroma, and hue angle

After cooking, samples were cut and bloomed by exposing them to air at room temperature for 30 min to measure color. After that, CIE L* (lightness), CIE a* (redness), and CIE b* (yellowness) were measured using a colorimeter with attached the CR-A92 aperture (CR-10, Konica minolta, Tokyo, Japan; standard illuminant D65, wide-angle 10°) on the cut surface. At that time, the standard color was the white standard edition of CIE L* + 97.83, CIE a* -0.43, and CIE b* + 1.98. The Chroma value was calculated as chroma (C*) = [(a*)2 + (b*)2]1/2. The hue angle was calculated as hue angle (H°) = arctan (b*/a*) × (180/π) at 360°, 0 (= 360) = + a*, 90 = + b*, 180 = -a*, and 270 = -b*.

Water holding capacity (WHC)

According to the method of Ortuño et al. (2015), the water holding capacity (WHC) before and after cooking was measured. The inner central part of the sample was cut into 0.3 g and pressed for 3 min in a filter press device. Thereafter, the total area and the inner area (sample area) were measured and calculated according to using Eq. (1):

| 1 |

Aging loss, injection yield, and cooking loss

Aging loss was calculated using the weight before and after wet-aging of each sample according to using Eq. (2). The weight was measured after removing the surface moisture from the pork loin.The injection yield of the sample was calculated using the weight before injection and the weight after storage for 24 h according to using Eq. (3). For measuring the cooking loss of the sample according to using Eq. (4), loin ham was performed as described above, and the weight was measured before and after loin ham cooking after removing the surface moisture.

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

Shear force

The shear force of the samples was used after the samples were cooked. After cooking, the cooked sample was cut into 2 × 1 × 1 cm (width × width × height) and measured three times, and a tissue analyzer (TA 1, Lloyd, Largo, FL, USA) equipped with a v-blade at the under was used; Head speed 2.0 mm/s, distance 2.0 mm, force 5 g. The sample was placed so that the direction of myofibrils was perpendicular to the v-blade, and the measurement result was indicated by N.

Electronic nose

Electronic nose analysis was performed according to Park and Kim (2022) method. 5 g of each cooked sample for analysis was placed in a 20 mL headspace vial and sealed. Thereafter, analysis was performed under the following conditions using flash gas chromatography electronin nose (Heracles NEO, Alpha MOS, Toulouse, France): gas chromatography injection port, injection rate 125 µL, injection temperature 200 °C, trap absorption temperature 80 °C, trap desorption temperature 250 °C, acquisition time 110 s, MXT-5 column, and MXT-1701 column. The flavor compounds that were measured were identified based on the Kovats index.

Electronic tongue

Electronic tongue analysis was performed using a taste sensor electronic tongue (Astree V, Alpha MOS, Toulouse, France). Each sample (8 g) was homogenized at 6451×g for 1 min using 32 mL of distilled water and a homogenizer (AM-5, Nissei, Tokyo, Japan). The homogenized sample was filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 1, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was diluted 1000-fold in distilled water and measured using a taste sensor electronic tongue. The analysis used CTS (salty), NMS (umami), and AHS (sour) sensors and auxiliary sensors SCS and CPS and standard sensors PKS and ANS to measure the signal intensity of each sensor.

Sensory evaluation

Eighteen sensory panelists evaluated the sensory properties of loin ham and wet-aged loin ham samples using the basic taste identification test. The panelists were undergraduate and graduate students majoring in food science-related fields and were trained for seven days (1 h session per day) using commercially available loin ham products; to familiarize themselves with the sensory properties of the loin ham and wet-aged loin ham samples to be evaluated. The sensory evaluation of loin ham of each treatment group was performed 3 times per session to complete the evaluation of the all treatment group (a total 9 times). The sensory evaluation sample was roasted at 80 °C., cut into 2 × 1 × 1 cm size, cooled for 3 min, and then served. Sensory evaluation panelists were given three sensory samples for each sample; each sample was given randomly with a time interval of 3 min between evaluation intervals. Each sensory characteristic item was evaluated on a 10-point scale; 10 = extremely good or desirable, 1 = extremely bad or undesirable.

Statistical analysis

The experiments in this study were designed in three independent batches (12 carcasses × 3 times). For each batch, loin ham prepared from raw meat and loin ham (CR 4 °C, PEFR 0 and -1 °C) were analyzed under three different wet aging conditions. In all experiments except for sensory evaluation, wet aging conditions were considered as fixed effects and batches as random effects. For sensory evaluation, wet aging conditions and panelists were considered as fixed effects, and batches and sessions were considered as random effects. All collected data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all variances and statistically analyzed using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05) and the general linear model of SAS (version 9.4 for window, SAS install Inc, Cary, NC, USA), a statistical processing program. Results were expressed as mean, standard error, and standard error of the mean (SEM). The electronic nose and electronic tongue were analyzed using Alphasoft 14.2 (Alpha MOS, Toulouse, France). The measured data from the electronic nose was determined by means of principal component analysis (PCA) to determine the differences between the samples. The electronic tongue data were interpreted using radar charts.

Results and discussion

pH and Proximate compositions

The measured pH of the loin ham after wet-aging is presented in Table 1. The pH was highest in the commercial refrigerator (CR) sample (p < 0.05), whilst it was lowest in the pulsed electric field refrigerator (PEFR) – 1 °C sample (p < 0.05). The increase in pH was due to the degraded products of basic proteins from wet-aging, whereas the decrease in pH was due to the lactic acid produced from the growth of lactic acid bacteria in anaerobic conditions (Hwang et al., 2018). Hence, it is conjectured that the increase in pH of the CR sample was due to the degraded products of basic proteins during wet-aging, whilst the decrease in pH of the PEFR samples were due to the lactic acid during the growth of lactic acid bacteria during the relatively long-term process of wet-aging. In addition, for meat products, the binding of H+ with nitrite salt to facilitate the reduction to nitric oxide increases when the pH is decreased, indicating the role of pH in flavor enhancement, antimicrobial activity, and the formation of colors unique to meat products (Kim et al., 2019). Jo et al. (2020) also reported that, for meat products, a reduction in pH by 0.2–0.3 could increase the rate of nitric oxide production twofold. Based on this, we can predict that applying PEF system in wet-aging for the production of loin ham would maximize the level of nitrite salt reaction.

Table 1.

pH, proximate compositions, aging loss, injection yield, and cooking loss of the cured pork loin ham and cured pork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions

| Traits | Raw meat | Wet-aging conditions | SEM1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PEFR | ||||

| 0 °C | − 1 °C | ||||

| pH | 5.91 ± 0.02b | 6.04 ± 0.01a | 5.86 ± 0.02c | 5.70 ± 0.05d | 0.038 |

| Moisture (%) | 67.67 ± 0.58a | 66.27 ± 0.16b | 66.85 ± 0.93ab | 64.33 ± 1.22c | 0.301 |

| Protein (%) | 27.55 ± 0.55b | 27.35 ± 0.33b | 27.37 ± 0.55b | 29.54 ± 0.66a | 0.377 |

| Fat (%) | 2.71 ± 0.27 | 2.93 ± 0.58 | 2.41 ± 0.16 | 2.66 ± 0.59 | 0.138 |

| Ash (%) | 1.26 ± 0.28 | 1.48 ± 0.02 | 1.63 ± 0.17 | 1.67 ± 0.16 | 0.078 |

| Aging loss | NA | 8.72 ± 2.19a | 5.86 ± 1.65b | 5.85 ± 1.34b | 0.510 |

| Injection yield | 91.67 ± 0.11 | 90.97 ± 0.79 | 90.74 ± 0.83 | 91.17 ± 1.17 | 0.172 |

| Cooking loss | 23.73 ± 0.40b | 29.94 ± 0.41a | 29.63 ± 0.53a | 28.97 ± 1.80a | 0.560 |

All values are expressed as mean ± SE

CR commercial refrigerator, PEFR pulsed electric field refrigerator

a−dMeans in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

1)Standard error of the mean

The proximate compositions of loin ham after wet-aging are also presented in Table 1. Moisture was highest in the raw meat sample (p < 0.05) and lowest in the PEFR – 1 °C sample (p < 0.05). This variation in moisture content was presumed to be a result of the influence of pH. For example, an increase in pH is known to increase moisture content as the increased positive charge leads to a higher water holding capacity (WHC) in myofibril proteins (Choi et al., 2016). We can therefore infer that pH had an effect on the moisture content of loin ham and that the use of PEFR would likely reduce moisture content. However, the CR sample showed the highest pH, but a lower content of moisture than the raw meat sample, possibly due to the lack of improvement in WHC during wet-aging and the lower WHC compared to raw meat after cooking. Protein content was highest in the PEFR – 1 °C sample (p < 0.05) across all loin ham samples. This was presumed to be due to the lower moisture content in the PEFR – 1 °C sample in comparison to other loin ham samples, whereby the protein content increased. The contents of fat and ash did not vary significantly between loin ham samples (p > 0.05), indicating that the use of wet-aging did not affect the fat and ash contents in loin ham, but did influence the moisture and protein contents.

CIE color, chroma, and hue angle

The measured color stability of loin ham after wet-aging is presented in Table 2. Lightness was highest in the CR sample compared to other loin ham samples (p < 0.05). Nitrite salt added to meat products reacts with myoglobin in the meat to produce nitroso myoglobin which provides the characteristic dark red color (Parthasarathy and Bryan, 2012). Hence, with the rate of nitric oxide production increased as a result of a reduced pH as previously described, the content of nitroso myoglobin increased, which is presumed to have lowered the lightness of other samples more than the CR sample. This redness was significantly higher in the raw meat sample than in wet-aging samples (p < 0.05), whilst the PEFR samples displayed significantly higher values than the CR sample (p < 0.05). During wet-aging, the sarcoplasmic proteins in meat were exuded (Colle et al., 2015), which lowered the myoglobin content in wet-aging samples compared to the raw meat sample, resulting in significantly lower redness. However, redness was significantly higher in the PEFR samples than in the CR sample, presumably because the relatively low pH of the PEFR samples led to the increased reduction of the added nitrite salt to nitric oxide, which increased the concentration of nitrosyl-hemochrome in line with the formation of nitric oxide myoglobin to increase redness (Jo et al., 2020). Yellowness was significantly higher in wet-aging samples than in the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). During wet-aging, the lipids in meat are oxidized and lipid oxidation products are known to increase yellowness (Xia et al., 2009). Hence, the use of wet-aging is presumed to also increase yellowness in loin ham. The chroma was significantly higher in the PEFR – 1 °C sample than in the CR sample (p < 0.05). As an indicator of the meat browning, the chroma decreased as the concentration of metmyoglobin increased (Vitale et al., 2014). When temperature was increased, the oxygen solubility in meat was reduced, which promoted the formation of metmyoglobin, and at temperatures below 0 °C, meat browning is prevented and color stability is improved (Jeremiah and Gibson, 2001). The results here indicated that the high chroma value of the PEFR – 1 °C sample could have been due to the suppressed browning resulting from the reduced formation of metmyoglobin in wet-aging at low temperatures. Hence, the use of PEFR with low-temperature aging is presumed to improve the color stability of loin ham. The hue angle was significantly higher in the wet-aging samples than in the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). The hue angle of meat indicates a change from red to yellow, whilst an increase in hue angle indicates a higher level of yellowness (Vitale et al., 2014). These results were due to the decrease in redness and the increase in yellowness of the wet-aging samples in this study. It is also presumed that the oxidation of lipids and myoglobin during wet-aging increased the hue angle of loin ham. In sum, the wet-aging of loin ham induced color changes, and in contrast to the use of CR, the use of PEFR was presumed to have improved the color stability.

Table 2.

CIE color, chroma, and hue angleof the cured pork loin ham and cured pork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions

| Traits | Raw meat | Wet-aging conditions | SEM1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PEFR | ||||

| 0 °C | − 1 °C | ||||

| Color | |||||

| CIE L* | 72.63 ± 0.12b | 77.80 ± 0.36a | 73.10 ± 0.72b | 73.20 ± 0.44b | 0.643 |

| CIE a* | 8.90 ± 0.35a | 6.03 ± 0.15c | 6.97 ± 0.42b | 7.10 ± 0.10b | 0.321 |

| CIE b* | 10.90 ± 0.10b | 12.33 ± 0.35a | 12.40 ± 0.62a | 12.83 ± 0.12a | 0.237 |

| Chroma | 14.07 ± 0.29ab | 13.73 ± 0.34b | 14.07 ± 0.54ab | 14.67 ± 0.06a | 0.137 |

| Hue angle | 50.78 ± 0.89b | 63.93 ± 0.74a | 61.00 ± 3.19a | 61.05 ± 0.54a | 1.677 |

All values are expressed as mean ± SE

CR commercial refrigerator, PEFR pulsed electric field refrigerator

a, bMeans in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

1)Standard error of the mean

Aging loss, injection yield, and cooking yield

The aging loss, injection yield, and cooking loss of loin ham after wet-aging are presented in Table 1. The aging loss was significantly lower in the PEFR samples than in the CR sample (p < 0.05). As protein degradation continues in meat during wet-aging, the consequent cytoskeletal degradation increases the moisture exuding out of muscle tissues (Holman et al., 2022). The variation in the level of such moisture exudation in muscle tissues is determined by the aging temperature. When the temperature is increased, the protein mobility also increases to reduce the drip viscosity and allow easy exudation into the space between muscle fibers (Choe et al., 2016). It is thus presumed that aging loss could be reduced by wet-aging at low temperatures with a PEFR. The injection yield did not vary significantly across loin ham samples (p > 0.05), indicating that the use of wet-aging did not affect the injection yield of loin ham. In addition, the cooking loss was significantly higher in the wet-aging samples than in the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). Sarcoplasmic proteins form a structure where they are bound with one another or with myofibril proteins to hold moisture (Purslow et al., 2016). Thus, the increased cooking loss in the wet-aging samples of this study can be attributed to the protein degradation in pork loin during wet-aging and the degradation of sarcoplasmic proteins, causing the fragmentation and subsequent exudation with moisture in cooking (Purslow et al., 2016). In sum, the use of PEFR in the production of cured pork loin ham would lower the aging loss and consequently improve the weight loss when compared to using CR.

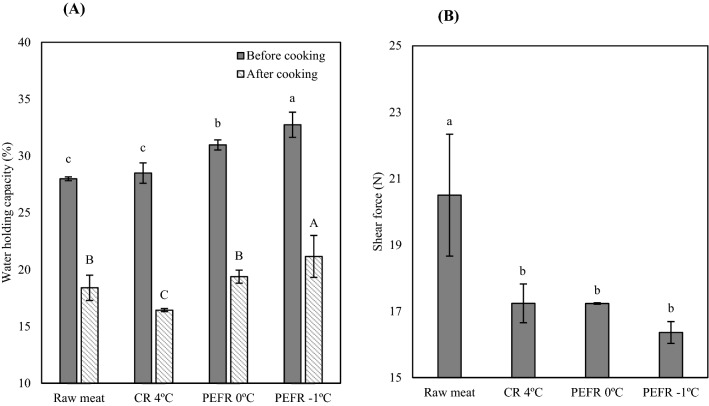

Water holding capacity (WHC) and shear force

The WHC of loin ham after wet-aging is presented in Fig. 1a. Compared to the raw meat and CR samples, the PEFR samples showed significantly higher WHC before cooking (p < 0.05), although the highest value of WHC was displayed by the PEFR – 1 °C sample (p < 0.05). The WHC after cooking was highest in the PEFR – 1 °C sample (p < 0.05) and was lowest in the CR sample (p < 0.05). The wet-aging of meat increased the WHC due to the structural decomposition of myofibril proteins and the destruction of the drip channel, allowing the exudation of moisture (Rodrigues et al., 2022). In addition, the Cl‒ ion of NaCl permeating the interior of muscle tissue during injection bonded with the H+ to increase the net negative charge, which expanded the muscle proteins to increase the WHC (Aliño et al., 2010). Hence, the improved WHC in the PEFR samples was presumed to be a result of protein structural decomposition during wet-aging and the increased absorption of additives by the PEF system (Gómez et al., 2019). In sum, the use of CR did not improve the WHC, while the use of PEFR in the production of loin ham did improve the WHC.

Fig. 1.

Water holding capacity (WHC; A) and shear force (B) of the cured pork loin ham and cured pork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions. a−c; A−CMean on the same bars with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). CR, Commercial refrigerator; PEFR, Pulsed electric field refrigerator

The shear force of loin ham after wet-aging is presented in Fig. 1b. Shear force was significantly lower in the wet-aging samples than in the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). As wet-aging progresses, the myofibril proteins in meat are degraded by proteases such as calpain, which reduces the shear force (Bhat et al., 2018). However, the shear force did not vary significantly here across wet-aging samples, presumably because the myofibril proteins were extracted, dissolved, and degraded in the injection and tumbling process during loin ham production, with an averaging effect on the physical properties of wet-aging samples (Pancrazio et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2022). Hence, the use of wet-aging was presumed to have reduced the shear force of loin ham, while the use of PEFR did not significantly improve the shear force.

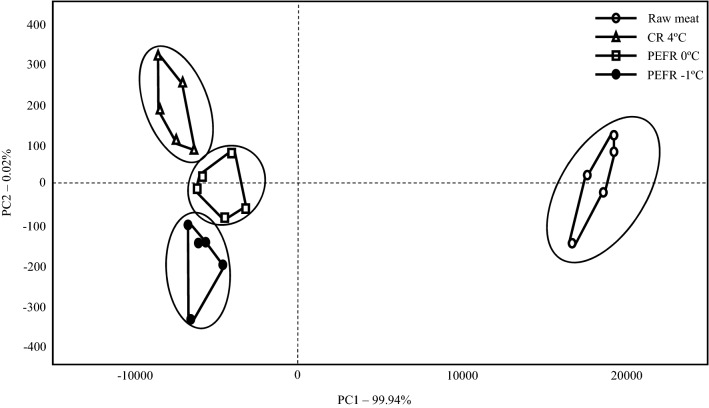

Electronic nose

The results of electronic nose analysis on the wet-aged loin ham are presented in Fig. 2. The PCA on the volatile aromatic compounds showed that the rate of contribution was 99.94% for the primary compounds (PC1) and 0.02% for the secondary compounds (PC2). According to these PC1 (99.94%) results, wet-aging had a significant effect on the formation of aromas of loin ham, and PC2 (0.02%) results presented that the use of PEFR did not affect the change of loin ham's aromas according to wet-aging. The variation in aroma between the raw meat samples and the wet-aging samples was due to the flavor development based on the formation of volatile compounds from the secondary products of lipid oxidation and the metabolites of microbial activity during wet-aging (Lee et al., 2021). As such, propanal was formed from lipid oxidation during wet-aging, while the volatile compounds produced from microbial metabolism included 2-methylbutanal, 2-methylpropanal, 1-butanamine, trimethylamine, 2-methylpropanthiol, and ethyl propanoate (Lee et al., 2021). Hence, the use of wet-aging was presumed to cause changes in the aroma of loin ham, and the consequent volatile compounds were predicted to create an aroma that could be favorably perceived. However, the use of PEFR was shown not to have a notable effect on the aroma of loin ham.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis plot of the cured pork loin ham and cured pork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions

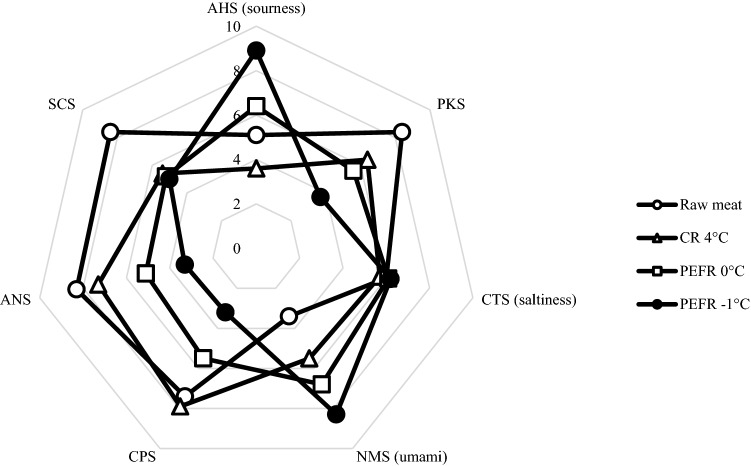

Electronic tongue

The results of electronic tongue analysis on the wet-aged loin ham are presented in Fig. 3. The PEFR – 1 °C sample showed the highest levels of sourness and saltiness, while the CR sample showed the lowest levels. However, there was only a small difference in saltiness, at a range of 5.7–6.2. Sourness is caused by acidification with a fall in pH (Flores, 2023) and hence, the sourness result was influenced by the pH, since the CR sample had the highest pH and the PEFR – 1 °C sample had the lowest. The insignificant difference in saltiness across the loin ham samples was likely due to the uniform dispersion of the curing solution throughout muscle tissues during injection in the production of loin ham. Umami was highest in the PEFR – 1 °C sample and lowest in the raw meat sample. During wet-aging, the meat umami was increased with the production of free amino acids (glutamic acid and aspartic acid), IMP, and GMP, the degradation products of proteins and nucleotides in meat. When the aging period was increases, umami increased further as these products accumulated (Xu et al., 2021). In line with this study, Lee et al. (2019) reported that, when wet-aged beef was analyzed using electronic tongue, the meat umami increased as the aging period increased, presumably due to the flavor compounds responsible for umami, such as free amino acids and IMP. Hence, the combined use of wet-aging and PEFR in the production of loin ham likely caused a significant improvement in the taste of meat.

Fig. 3.

Intensity comparison score radar chart of the cured pork loin ham and cured pork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions using taste sensors electronic tongue. AHS sourness, SCS standard sensor, PKS auxiliary sensor, ANS auxiliary sensor, CTS saltiness, CPS standard sensor, NMS umami, CR commercial refrigerator, PEFR Pulsed electric field refrigerator

Sensory evaluation

The results of sensory evaluation on the wet-aged loin ham are presented in Table 3. The score of color was significantly higher for raw meat and PEFR – 1 °C samples than the CR sample (p < 0.05). This indicated that the conventional wet-aging (CR) had a negative effect on the color of loin ham; hence, the use of wet-aging with a PEFR was predicted to improve color reduction. The score of taste was significantly higher in the PEFR samples than the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). This is due to the production of flavor compounds such as free amino acids, IMP, and GMP in meat during wet-aging (Xu et al., 2021). These results agreed with the trend of increasing umami in the PEFR samples in comparison to the raw meat sample in the electronic tongue analysis. Hence, the use of PEFR likely improved the taste of loin ham based on the increased production of umami-related compounds. In the evaluation of rancid flavor, no significant variation was found between loin ham samples (p > 0.05), whereas the evaluation of metallic flavor, flavor, off-flavor, and texture all placed significantly higher scores for the wet-aging samples than the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). Myoglobin is known to be closely associated with metallic flavor as it is a type of sarcoplasmic protein with a heme containing iron (Gerhard, 2020). This accounted for the high metallic flavor score in wet-aging samples based on the exudation of sarcoplasmic proteins from meat during wet-aging. In addition, the evaluation of flavor and off-flavor indicated a positive effect from wet-aging on the flavor of loin ham, which was shown to be related to the variation in aroma in the electronic nose analysis between the wet-aging samples and the raw meat samples. Texture is a sensory property determined by a variety of factors, and the score of texture tends to increase as meat softness and moisture are enhanced (Font-i-Furnols and Guerrero, 2014). The wet-aging samples in this study showed a reduction in shear force due to the degradation of myofibril proteins during wet-aging, which was presumably the reason for the high texture score. The overall acceptability was significantly higher in the PEFR 0 °C sample than the raw meat sample (p < 0.05). In sum, the use of CR in the production of loin ham could improve the metallic flavor, flavor, off-flavor, and texture, but with a negative effect on the color. In contrast, the wet-aging with a PEFR had no negative effect on the color, while improving the taste, metallic flavor, flavor, off-flavor, and texture, the combination of which led to an increase in the overall acceptability. It is thus predicted that the sensory properties would be both improved and developed through the use of wet-aging with a PEFR in the production of loin ham.

Table 3.

Sensory evaluation of the cured pork loin ham and curedpork loin ham after wet-aging with different conditions

| Traits | Raw meat | Wet-aging conditions | SEM1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PEFR | ||||

| 0 °C | − 1 °C | ||||

| Color | 9.15 ± 0.58a | 8.53 ± 0.57b | 8.64 ± 0.53ab | 9.11 ± 0.45a | 0.103 |

| Taste | 7.77 ± 0.92b | 8.33 ± 0.84ab | 8.59 ± 0.87a | 8.50 ± 0.68a | 0.118 |

| Rancid | 8.36 ± 1.20 | 7.96 ± 0.95 | 8.56 ± 1.27 | 8.79 ± 0.96 | 0.146 |

| Metallic | 7.45 ± 1.18b | 8.63 ± 1.26a | 8.48 ± 1.25a | 8.71 ± 0.91a | 0.159 |

| Flavor | 7.84 ± 1.03b | 8.76 ± 1.00a | 8.71 ± 1.03a | 8.58 ± 0.47a | 0.130 |

| Off-flavor | 7.23 ± 1.25b | 8.21 ± 1.10a | 8.29 ± 0.67a | 8.36 ± 0.60a | 0.191 |

| Texture | 7.39 ± 1.01b | 8.74 ± 0.98a | 8.64 ± 0.55a | 8.30 ± 0.41a | 0.118 |

| Overall acceptability | 7.67 ± 0.78b | 8.56 ± 0.90ab | 8.64 ± 0.68a | 8.20 ± 0.82ab | 0.155 |

All values are expressed as mean ± SE

CR commercial refrigerator, PEFR pulsed electric field refrigerator

a,bMeans in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

1)Standard error of the mean

In conclusion, PEFR and wet-aging had independent effects on the quality properties of pork loin ham in this study. The use of wet-aging was shown to increase the yellowness, hue angle, and cooking loss of loin ham whilst decreasing the redness and shear force. The use of PEFR was shown to decrease the pH, moisture content, lightness and aging loss compared to the use of CR, while the protein content, redness, and chroma displayed an increasing trend, based on which a positive effect on quality enhancement was verified. In the electronic nose analysis, the aroma of loin ham was shown to have changed during wet-aging, whilst in the electronic tongue analysis, the sourness was shown to have increased as the pH of the loin ham sample increased, while the use of wet-aging was found to have increased the umami of loin ham. The sensory evaluation results indicated that the use of CR reduced the color score but could enhance various sensory properties excluding taste and rancid flavor. The PEFR samples also exhibited an enhancement across all sensory properties except rancid flavor. The PEFR 0 °C, in particular, was given a significantly high score of overall acceptability compared to the raw meat sample. Based on this, the use of wet-aging with a PEFR in the production of loin ham was deemed suitable for loin ham quality enhancement.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (KRF), which is funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1D1A1B07049938).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ha-Yoon Go, Email: snailcake@naver.com.

Sin-Young Park, Email: parksy@kongju.ac.kr.

Hack-Youn Kim, Email: kimhy@kognju.ac.kr.

References

- Alahakoon AU, Faridnia F, Bremer PJ, Silcock P, Oey I. Pulsed electric fields effects on meat tissue quality and functionality. Vol. 4, pp. 2455–2475. In: Handbook of Electroporation. Miklavčič D, Knorr D, Raso J, Vorobiev E (Eds). Springer International Publishing, AG, Switzerland (2016)

- Aliño M, Grau R, Fernández-Sánchez A, Arnold A, Barat JM. Influence of brine concentration on swelling pressure of pork meat throughout salting. Meat Science. 2010;86:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 18th ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Gaithersburg, MD, USA (2005)

- Bhat ZF, Morton JD, Mason SL, Bekhit AEDA. Role of calpain system in meat tenderness: A review. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2018;7:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2018.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Witte F, Terjung N, Januschewski E, Heinz V, Juadjur A, Gibis M. Analysis of aging type-and aging time-related changes in the polar fraction of metabolome of beef by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Food Chemistry. 2021;342:128353. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J, Kim HY. Comparison of three commercial collagen mixtures: Quality characteristics of marinated pork loin ham. Food Science of Animal Resources. 2019;39:345. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2019.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J, Stuart A, Kim YHB. Effect of different aging temperatures prior to freezing on meat quality attributes of frozen/thawed lamb loins. Meat Science. 2016;116:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YS, Jeong TJ, Hwang KE, Song DH, Ham YK, Kim YB, Jeon KH, Kim HW, Kim CJ. Effects of various salts on physicochemical properties and sensory characteristics of cured meat. Food Science of Animal Resources. 2016;36:152. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2016.36.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colle MJ, Richard RP, Killinger KM, Bohlscheid JC, Gray AR, Loucks WI, Day RN, Cochran AS, Nasados JA, Doumit ME. Influence of extended aging on beef quality characteristics and sensory perception of steaks from the gluteus medius and longissimus lumborum. Meat Science. 2015;110:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores M. Chapter 13 - The eating quality of meat: III—Flavor. pp. 421–455. In: Lawrie's meat science. Toldrá F (ed). Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Cambridge, UK (2023)

- Font-i-Furnols M, Guerrero L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Science. 2014;98:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard GS. Heme as a taste molecule. Current Nutrition Reports. 2020;9:290–295. doi: 10.1007/s13668-020-00320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez B, Munekata PE, Gavahian M, Barba FJ, Martí-Quijal FJ, Bolumar T, Campagnol PCB, Tomasevic I, Lorenzo JM. Application of pulsed electric fields in meat and fish processing industries: An overview. Food Research International. 2019;123:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman BW, Bekhit AEDA, Mao Y, Zhang Y, Hopkins DL. The effect of wet ageing duration (up to 14 weeks) on the quality and shelf-life of grass and grain-fed beef. Meat Science. 2022;193:108928. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang YH, Sabikun N, Ismail I, Joo ST. Comparison of meat quality characteristics of wet-and dry-aging pork belly and shoulder blade. Food Science of Animal Resources. 2018;38:950. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2018.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremiah LE, Gibson LL. The influence of storage temperature and storage time on color stability, retail properties and case-life of retail-ready beef. Food Research International. 2001;34:815–826. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00104-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jo K, Lee S, Yong HI, Choi YS, Jung S. Nitrite sources for cured meat products. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und -Technologie- Food Science and Technology. 129: 109583 (2020)

- Kim YHB, Ma D, Setyabrata D, Farouk MM, Lonergan SM, Huff-Lonergan E, Hunt MC. Understanding postmortem biochemical processes and post-harvest aging factors to develop novel smart-aging strategies. Meat Science. 2018;144:74–90. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hwang KE, Song DH, Ham YK, Kim YB, Paik HD, Choi YS. Effects of natural nitrite source from Swiss chard on quality characteristics of cured pork loin. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2019;32:1933–1941. doi: 10.5713/ajas.19.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Choe J, Kim M, Kim HC, Yoon JW, Oh SW, Jo C. Role of moisture evaporation in the taste attributes of dry- and wet-aged beef determined by chemical and electronic tongue analyses. Meat Science. 2019;151:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Lee HJ, Yoon JW, Kim M, Jo C. Effect of different aging methods on the formation of aroma volatiles in beef strip loins. Foods. 2021;10:146. doi: 10.3390/foods10010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Szczepaniak S, Steen L, Goemaere O, Impens S, Paelinck H, Zhou G. Effect of tumbling time and cooking temperature on quality attributes of cooked ham. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2011;46:2159–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02731.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mungure TE, Farouk MM, Birch EJ, Carne A, Staincliffe M, Stewart I, Bekhit AEDA. Effect of PEF treatment on meat quality attributes, ultrastructure and metabolite profiles of wet and dry aged venison Longissimus dorsi muscle. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies. 2020;65:102457. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pancrazio G, Cunha SC, De Pinho PG, Loureiro M, Meireles S, Ferreira IM, Pinho O. Spent brewer's yeast extract as an ingredient in cooked hams. Meat Science. 2016;121:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy DK, Bryan NS. Sodium nitrite: The “cure” for nitric oxide insufficiency. Meat Science. 2012;92:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purslow PP, Oiseth S, Hughes J, Warner RD. The structural basis of cooking loss in beef: Variations with temperature and ageing. Food Research International. 2016;89:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues LM, Guimarães AS, de Lima Ramos J, de Almeida Torres Filho R, Fontes PR, de Lemos Souza Ramos A, Ramos EM. Application of gamma radiation in the beef texture development during accelerated aging. Journal of Texture Studies. 1–12 (2022) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tamm A, Bolumar T, Bajovic B, Toepfl S. Salt (NaCl) reduction in cooked ham by a combined approach of high pressure treatment and the salt replacer KCl. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies. 2016;36:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2016.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale M, Pérez-Juan M, Lloret E, Arnau J, Realini CE. Effect of aging time in vacuum on tenderness, and color and lipid stability of beef from mature cows during display in high oxygen atmosphere package. Meat Science. 2014;96:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X, Kong B, Liu Q, Liu J. Physicochemical change and protein oxidation in porcine longissimus dorsi as influenced by different freeze–thaw cycles. Meat Science. 2009;83:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Liu S, Cheng Y, Qian H. The effect of aging on beef taste, aroma and texture, and the role of microorganisms: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 1–12 (2021) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhou Y, Hu M, Wang L. Effects of different curing methods on edible quality and myofibrillar protein characteristics of pork. Food Chemistry. 2022;387:132872. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]