Abstract

Introduction

To achieve quality in medical education, peer teaching, understood as students taking on roles as educators for peers, is frequently used as a teaching intervention. While the benefits of peer teaching for learners and faculty are described in detail in the literature, less attention is given to the learning outputs for the student-teachers. This systematic review focuses on the learning outputs for medical undergraduates acting as student-teachers in the last decade (2012–2022).

Aim

Our aim is to describe what learning outputs student-teachers have from peer teaching, and map what research methods are used to assess the outputs. We defined learning outputs in a broad sense, including all types of learning experiences, intended and non-intended, associated with being a peer teacher.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in four electronic databases. Title, abstract and full text were screened by 8 independent reviewers and selection was based on predefined eligibility criteria. We excluded papers not describing structured peer teaching interventions with student-teachers in a formalized role. From the included articles we extracted information about the learning outputs of being a student-teacher as medical undergraduate.

Results

From 668 potential titles, 100 were obtained as full-texts, and 45 selected after close examination, group deliberation, updated search and quality assessment using MERSQI score (average score 10/18). Most articles reported learning outputs using mixed methods (67%). Student-teachers reported an increase in subject-specific learning (62%), pedagogical knowledge and skills (49%), personal outputs (31%) and generic skills (38%). Most articles reported outputs using self-reported data (91%).

Conclusion

Although there are few studies that systematically investigate student-teachers learning outputs, evidence suggests that peer teaching offers learning outputs for the student-teachers and helps them become better physicians. Further research is needed to enhance learning outputs for student-teachers and systematically investigate student-teachers’ learning outputs and its impact on student-teachers.

Keywords: peer-assisted learning, medical school, medical student, peer teacher

Introduction

Peer teaching, defined as teaching performed by “A person who is the same age or has the same social position or the same abilities as other people in the group” is being used worldwide both in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education.1,2 Studies have shown that students learn as much from being taught by peers as they do from expert teachers.3,4 In addition, it has been argued that the social and cognitive congruence that characterize the student-learner and student-teacher relationship creates psychological safe learning spaces, mutual understanding of difficulties and customized models for explaining the learning content.5–7 Also, it is argued that peer teaching alleviates teaching pressure for faculty.6

Whitmans description of “teaching as learning twice” from 19888,9 suggests that peer teaching also benefits the student-teacher. Previous studies point to improved written and/or practical examination scores for students that were teaching peers in basic sciences,10 participated in a small-group based Gastroenterology/Hematology course where they alternated being group facilitators11 and students acting as student-teachers in musculoskeletal ultrasound interpretation compared to their same year peers.12 Burgess et al13 found that the benefits of peer teaching for the student-teacher can be described in two main categories: Development in understanding of knowledge content and development of professional attributes. The two categories include increased awareness of facilitation, teaching and feedback techniques, leadership qualities, confidence, open-mindedness and autonomy. Finally, a review conducted in 2020 by Bower et al14 documented opportunities for student-teachers to consolidate their own learning while contributing to the medical school community. However, the 2020 review focused on informal near peer teaching and not formalized peer teaching initiatives.14 For peer teaching to have positive learning outputs for the student-teacher, the literature highlights the need for teacher training and support from faculty.15

Many of the competencies used to evaluate learning outputs of student-teachers are reflected in medical curricula worldwide as part of the CanMEDS framework designed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS identifies and describes the competences required of medical doctors to meet the health care needs of patients. The competences are organized under a set of roles: medical expert, communicator, collaborator, leader, health advocate, scholar and professional.16 This framework enables us to organize the potential learning outputs gained from peer teaching and to explore how being a peer teacher can facilitate the development of core competencies among student-teachers.

While the CanMEDS framework provides a useful basis for identifying key competencies, systematizing the available knowledge about learning outputs of student-teachers is challenged by overlapping definitions of peer teaching in the literature. Peer teaching is often used as an umbrella term including both collaborative learning, peer-assisted learning, near-peer teaching, teaching assistants, peer and near-peer supervision, mentoring and more. As a result, the student-teachers role can become unclear as it can both entail being a collaborative resource for fellow students within the same program and having a dedicated role as an educator for same level or more junior students. While recognizing that the role of an educator might entail assessment, feedback and supervision, we limited our screening to studies that described teaching activities where students had a clear and formalized role as an educator. This means that peer assessment, peer feedback and reciprocal learning activities, where peers take turns teaching each other or engage in group learning activities, were excluded. While previous reviews have focused more broadly on the effectiveness of peer teaching, this systematic review focuses on the learning outputs for student-teachers in formalized peer teaching settings. To further limit our review, we focused on undergraduate medical education, thus excluding postgraduate education, residency training and interdisciplinary studies. Previous reviews provide sufficient summaries of evidence prior to 2012,13 hence, we limit our review to qualitative and quantitative studies focusing on learning outputs for student-teachers published between 2012 and 2022. Knowledge regarding outputs of peer teaching for the student-teachers might help medical faculties design peer teaching regimes with benefits for all the parties involved. Thus, our aim was to describe what learning outputs student-teachers have from peer teaching, and map what research methods are used to assess these outputs.

Materials and Method

To achieve our aim, a systematic search in four databases was conducted. The findings from the studies were summarized in tables, and the results were set up against CanMEDS framework.

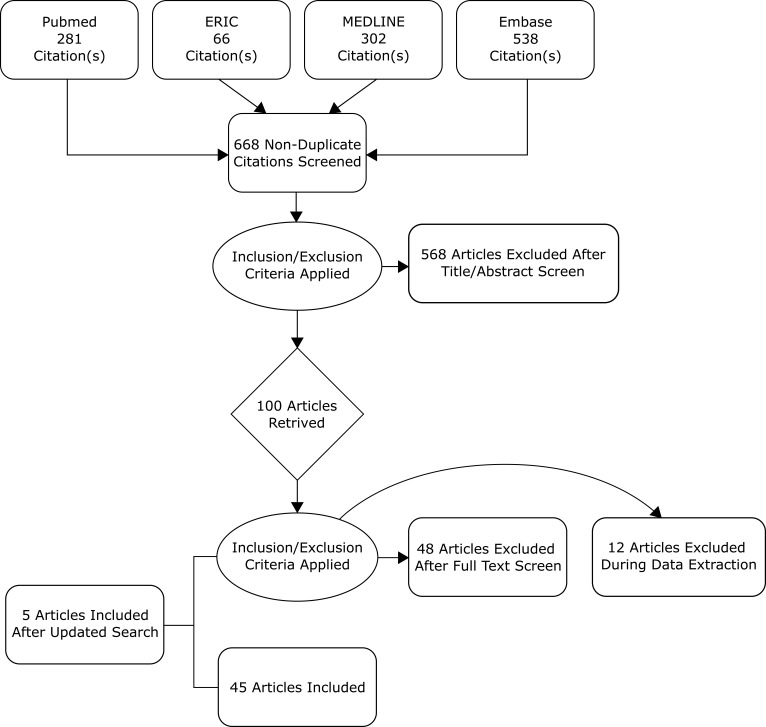

The literature search was conducted during October and November 2021, and updated in November 2022, in Embase, ERIC databases, MEDLINE and PubMed. The search was conducted using search terms: “near peer teaching”, “peer assisted learning”, “peer mentor”, “peer tutor” and “peer teacher(s)”, additionally the search was restricted to undergraduate medical education (Table 1). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 2020 was used as a guide to record the review process (Figure 1).17 All articles were retrieved in the bibliography management program EndNote X9. Duplicates were removed before the remaining articles were uploaded in Rayyan AI where the articles were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined below (Table 2). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed based on our aim to gather information about student-teachers at undergraduate medical education level.

Table 1.

Search Terms and Keywords Used in the Literature Search

| PubMed | Embase, ERIC Databases and MEDLINE |

|---|---|

| In PubMed the search was conducted using search terms: “near peer teaching”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer assisted learning”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer mentor”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer tutor”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer teach*”[Title/Abstract] combined with search terms “Education, medical, undergraduate”[MeSH Terms] OR “undergraduate medical”[Title/Abstract] using the Boolean operator AND | The search on Embase, ERIC databases and MEDLINE was conducted using search terms: “exp Medical school” or “exp Medical student” combined with search terms “near peer teaching.mp” OR “peer assisted learning.mp” OR “peer mentor.mp” OR “peer tutor.mp” OR “peer teach$.mp” using the Boolean operator AND. |

Notes: *Truncation symbol in PubMed. $ Truncation symbol in Embase, ERID databases and MEDLINE. exp = “explosion”, meaning this search not only look for the subject term selected but also many related subjects. mp = “multi-purpose”, meaning this search look at several fields at once, including title, abstract, keyword, original title and heading word.

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying the whole process of assessing and selecting articles for this review.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Screening of Articles

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

One reviewer (first author) screened all the 668 articles that were retrieved in the original search, whereas the co-authors (four researchers from University of Bergen, and three researchers from Karolinska Institutet) screened approximately 100 articles each, ensuring a double blinded review process. Conflicts were resolved by discussion between four of the authors (MAT, TM, MK and HHA). Out of 668 records, 100 articles were contained initially and subjected to full-text screening. After the initial full-text screening and data extraction 40 articles were selected. After the updated search 45 articles were included in this review as the final material.

To ensure reliable and valid data, the quality of the quantitative studies included was evaluated by two reviewers (MAT, IGS) using The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI).18–20 The instrument is based on 10 items, reflecting six domains of study quality: (1) study design, (2) number of institutions studied and response rate, (3) data type, (4) validity evidence for evaluation instrument, (5) data analysis sophistication and appropriateness, and (6) outcome level. The maximum domain score is 3, and a minimum of 0–1, producing a potential range of 5–18 MERSQI scores.20

The results were critically synthesized by multiple reviewers using categories based on past literature and CanMEDS framework. The findings from the studies are summarized in tables, giving an appropriate schematic informative focus to this review.

Results

A total of 45 articles were included in the review. Table 3 gives an overview of the included articles and presents each publication with authors, quality assessment using MERSQI score, country of origin, number of student-teachers and student-learners, study design, and teacher training intervention. Furthermore, dimensions of teaching encounters are described using three subcategories: frequency and dimension, group size and teaching subject. The last category reports learning outputs for student-teachers and what methods that were used to assess the outputs.

Table 3.

Schematic Overview of Included Articles

| Authors (Article Quality Assessment) | Country of Origin | Student-Teacher (N) | Student-Learner (N) | Study Design | Teacher Training Intervention | Dimensions of Teaching Encounter | Reported Learning Outputs and Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency and Duration | Group Size | Subject | |||||||

| Agius & Stabile21 (12.5/18) | Malta | Year 1–2 (12) | Year 1–2 (191) | Comparative longitudinal study – Quantitative | No | 6 sessions | Not specified | Anatomy |

|

| Ahmad et al22 (13/18) | USA | Year 4 (36) | Year 3 (75) | Non-inferiority – Mixed method | Yes | 1 session | Not specified | Rheumatology |

|

| Ahn et al23 (12/18) | USA | Year 4 (20) | Year 1 (155) and Year 2 (155) | Evaluation research – Quantitative | Yes | 1–5 sessions | 1:14; tutor tutees | Ultrasound/ Physical examination |

|

| Alvarez et al24 (11.5/18) | Germany | Year 2 (24) | Not specified | Longitudinal mixed method | Yes | 18 months, sessions not specified | Not specified | Anatomy |

|

| Blohm et al25 (10.5/18) | Germany | Year 3–5 (10) | Year 1 and 2 (135) | Longitudinal mixed method | Yes | 2 sessions | 1:20; tutor:tutees | Internal medicine |

|

| Bugaj et al26 (n/a) | Germany | Year 3–5 (10) | Not specified | Qualitative study | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Physiology & internal medicine |

|

| Burgess et al27 (n/a) | Australia | Year 3 (46) and Year 4 (60) | Year 1 (50) and Year 2 (51) | Qualitative study | No | 1 h session per week. 1 year | Not specified | Multiple subjects |

|

| Cansever et al28 (8/18) | Turkey | Year 1 (11) | Year 1 (330) | Survey study – Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Biochemistry, medical genetics, histology and embryology, anatomy and microbiology |

|

| Cho et al29 (8/ 18) | Korea | Year 2–4 (Not specified) | Year 2–4 (Not specified) | Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Multiple subjects |

|

| Chopra et al30 (7/18) | USA | Year 4 (14) | Not specified | Mixed method observational study | No | Not specified | Not specified | Ophthalmology |

|

| Clarke et al31 (7/18) | Australia | Year 3–4 (42) | Year 1–2 (66) | Mixed method | Yes | 1 h × 1–13 sessions. 7 months | 2:3–4; tutor: tutees | Clinical skills, professionalism |

|

| Cusimano et al32 (n/a) | Canada | Year 3 (20) | Year 1 (100) | Qualitative descriptive research study | Yes | 2 h × 3 sessions | 1:20; tutor:tutees | Ethics, professionalism, behavior |

|

| de Menezes et al33 (n/a) | Australia | Year 5 (30) | Year 3 (40) | Longitudinal qualitative study | Yes | 1 h × 6 sessions | 1:4–6; tutor:tutees | Multiple subjects |

|

| Dickman et al34 (10/18) | Israel | Year 2 (4–6) | Year 1 (ca. 70) | Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Anatomy, ultrasound |

|

| Engels et al35 (10/18) | USA | Year 1–5 (481) | Year 1–5 (Not specified) | Cross sectional study – Quantitative | Yes | Not specified | 1:5–10 | Anatomy, Neuro-Physiology |

|

| Gottlieb et al36 (10/ 18) | USA | Year 4 (12) | Year 2 (Not specified) | Mixed method | Yes | 2 h × 7 sessions | Not specified | Respiratory pathophysiology |

|

| Hall et al37 (8/18) | UK | Not specified (51) | Not specified | Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Anatomy |

|

| Gandhi et al38 (8/18) | UK | Year 6 (30) | Year 5–6 (140) | Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | 1:2; tutor:tutee | Pediatrics |

|

| Iwata et al39 (12.5/18) | UK | Year 6 (172) | Not specified | Retrospective cohort study | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Multiple subjects |

|

| Khaw et al40 (13/18) | Australia | Year 6 (45) | Year 1–2 (348) | Survey study – Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Physical examination, history taking |

|

| Kumar et al41 (10.5/18) | UK | Not specified (10) | Not specified (61) | Longitudinal study- Quantitative | Not specified | 80 min × 6 sessions | Not specified | Orthopedic examination |

|

| Liew et al42 (12/18) | Malaysia | Year 3–5 (51) | Year 1–3 (1053) | Longitudinal study- Quantitative | Yes | 2 h ×4 sessions | Not specified | Communication and clinical skills |

|

| Lin et al43 (12/18) | USA | Not specified (6) | Not specified (55) | Retrospective cohort study – Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | 1:3; tutor:tutee | Basic surgery skills |

|

| Lufler et al44 (11/18) | USA | Year 4 (32) | Year 1 (402) | Longitudinal study- Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Anatomy |

|

| Mohd Shafiaai et al45 (10.5/18) | Malaysia | Year 2 (40) | Year 1 (Not specified) | Longitudinal study- Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | Not specified | Communication |

|

| Naeger et al46 (11/18) | USA | Year 4 (17) | Year 1 (120) | Survey study – Mixed method | Yes | 1.5 h × 1 session | 1:5–6; tutor:tutees | Radiology |

|

| Nelson et al47 (10/18) | Australia | Year 6 (24) | Year 1–2 (358) | Longitudinal mixed method | No | 2 h sessions × 4 times a week | 1:4; tutor:tutees | Clinical skills |

|

| Nshimiyimana et al48 (n/a) | Rwanda | Year 5 (Not specified) | Year 5 (Not specified) | Qualitative study | No | 3 h × 1 session | 1:18–25; tutor:tutees | Paediatrics |

|

| Prunuske et al49 (n/a) | USA | Year 2 (9) | Year 1 (31) | Qualitative study | No | 4 weeks | 1:4–5; tutor:tutees | Multiple subjects |

|

| Reyes-Hernández et al50 (6/18) | Mexico | Year 2–5 (120) | Year 1 (Not specified) | Cross-sectional study – Quantitative | Yes | Not specified | 1:6–5; tutor:tutees | Anatomy |

|

| Sahoo et al51 (9.5/18) | Malaysia | Year 4 (6) | Year 4 (98) | Longitudinal mixed method | No | 0.5 h × 1 session × 4 week | 1:9.5; tutor:tutees | Ophthalmology |

|

| Siddiqi et al52 (12.5/18) | Pakistan | Year 1 (10) | Year 1 (62) | Cross-sectional study – mixed method | Yes | Not specified | 1:7–11; tutor:tutees | Pharmacology & physiology |

|

| Silbert et al53 (11/18) | Australia | Year 4–6 (64) | Year 3 (321) | Longitudinal quantitative study | Yes | 4 h session × 6 | 1:12; tutor:tutees | Multiple subjects |

|

| Srivastava et al54 (12/18) | India | Year 1 (20) | Year 1 (87) | Non-randomized interventional mixed method | No | 4 sessions | 1:10; tutor:tutees | Physiology |

|

| Tamachi et al55 (n/a) | UK | Year 4 (3) | Year 3–5 (5) | Qualitative study | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Multiple subject |

|

| Walser et al56 (9.5/18) | Germany | Year 3+ (38) | Year 2 (388) | Longitudinal mixed method | Yes | 16 sessions | 1:10; tutor:tutees | Anatomy |

|

| Yang et al57 (n/a) | USA | Year 3 (Not specified) | Year 3 (Not specified) | Longitudinal qualitative study | No | 26 sessions or more | Not specified | Clinical clerkship |

|

| Young et al58 (6/18) | UK | Year 4 (103) | Year 3 (245) | Cross-sectional study – Mixed method | No | 3 sessions | Not specified | Multiple subjects (Objective structured clinical examination) |

|

| Nomura et al59 (9/18) | Japan | Year 5 (6) | Year 4 (58) | Mixed method | Yes | 1.5 h–3 h × 4 sessions | Not specified | Medical interview training |

|

| Zuo et al60 (8/18) | USA | Year 2 (52) | Year 1 (240) | Survey study – Mixed method | Yes | 30–45 min × 2 session | 1:6; tutor:tutees | Anatomy |

|

| Avonts et al61 (9/18) | Belgium | Year 3–5 (Not specified) | Year 3–5 (78) | Retrospective cohort study –Mixed method | Yes | 3–5 sessions per year | 5–8:30–50; tutor: tutees | Multiple subjects (Objective structured clinical examination) |

|

| Aydin et al62 (8/18) | Turkey | Year 1–2 (159) | Year 3 (43) | Cross-sectional study – Mixed method | Yes | 2 hour × 10 days | Not specified | Clinical skills |

|

| Diebolt et al63 (8/18) | USA | Year 3 (106) | Year 4 (40) | Prospective study – Mixed method | Yes | 2 days | Not specified | Surgery clerkship |

|

| Orsini et al64 (6/18) | Italy | Year 1–2 and 4 (Not specified) | Year 3–6 (348) | Retrospective study – Mixed method | Yes | Not specified | 1:6–8; tutor: tutees | Anatomy |

|

| Shah65 (7/18) | UK | Year 4 (72) | Year 5 (13) | Longitudinal study – Mixed method | No | 22 session × 3 months | 2:11–49; tutor: tutees | OSCE |

|

Description of the Student-Teachers

The included studies describe peer teaching activities set in 14 different countries with the USA, Australia and the UK as the most predominant. Student-teachers in the articles reviewed were recruited from all levels of medical school. Most of the studies reported having a one-year gap between the student-teachers and student-learners. Number of student-teachers included in the studies ranged from 3 student-teachers55 to 481 student-teachers,35 and number of student-learners included in studies ranged from 5 student-learners55 to 1053 student-learners.42

Anatomy, clinical skills and communication were the most frequent subjects taught by the student-teachers. The amount of teaching sessions varied in frequency from only one teaching session48 to 26 sessions.57 They also varied in duration from 30 minutes51,60 to 4 hours.53 Furthermore, peer teaching was deployed in various group sizes of learners ranging from 4 students in the smallest group47,49 to 25 in the biggest group.48 Some articles did not specify group sizes.

Reported Learning Outputs

Most of the studies reported multiple learning outputs for the student-teachers (see Table 4). In the following section, outputs for the student-teachers are reported in four domains set by the reviewers based on previous literature and CanMEDS framework: subject-specific learning outputs, pedagogical knowledge and skills, personal outputs and generic skills.

Table 4.

Overview of Studies Reporting Types of Learning Outputs

| Reported Outputs | Number of Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Subject-specific learning outputs | 62% (28/45) | [21–24,26,27,30,31,34–39,41–44,46,47,49,50,56,60–62,64,65] |

| Pedagogical knowledge and skills | 49% (22/45) | [22,23,27,28,30,35,36,43,44,46,48,50,52–54,58,59,61–65] |

| Personal outputs | 31% (14/45) | [24,28,29,33,34,40,51–53,59,62–65] |

| Generic skills | 38% (17/45) | [22,24–26,32,37,38,45,49,52,55,57,59–62,64] |

Subject-Specific Learning Outputs

Several studies reported that student-teachers increased their learning about the content they were teaching. Additionally, improved skillset and technical performance were also frequently reported. One article reported better results in objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)39 and another article reported better results in anatomy examinations.21 Furthermore, two articles reported that student-teachers felt better prepared for OSCE after completing the peer teaching program.38,41

Pedagogical Knowledge and Skills

Improved pedagogical knowledge and skills were reported in several articles, where student-teachers reported developing better understanding and awareness of the teaching process and feedback strategies. In one study the student-teachers reported improved teaching skills, which they in turn considered helpful to their future roles as residents and attendings within the field of surgery.43

Personal Outputs and Generic Skills

Many of the studies found teaching activities to be useful related to personal outputs such as confidence, self-awareness and courage. In one longitudinal mixed method study within anatomy, student-teachers reported strengthened confidence, optimism and resilience.24 In several studies, student-teachers thought of the experience as helpful in improving their generic skills such as communication, teamwork, leadership and becoming role models for their junior peers. The teaching experience was also considered as supporting students’ professional identity formation.55,57,64

Three studies reported unwanted outputs of peer teaching.29,30,34 Two of those found that student-teachers experienced lack of control and authority.29,30 One of the three studies found that student-teachers felt uncomfortable teaching their peers due to the lack of necessary skills.34 The authors suggested that this is likely caused by student-teachers receiving inadequate training before taking on the teacher role.34

Methodological Quality of Studies

Quality Assessment

All the included quantitative studies were quality assessed using MERSQI. The scores ranged from 6 (lowest)50,58,64 to 13 (highest),22,40 and the average score for all the included quantitative studies was 10. As eight of the studies reported qualitative research, they were not subjected to MERSQI score assessment.26,27,32,33,48,49,55,57 No articles were excluded based solely on their MERSQI score.

Study Design

A mixed-method study design was used in 67% (30/45) of the included studies, with qualitative and quantitative data extracted from student-teacher(s) and/or student-learner(s). Qualitative study design was used in 18% (8/45) of the studies, and 16% (7/45) had a quantitative study design. As shown in Table 5, most of the studies included in this review used self-reported data to gather information about learning outputs from peer teaching experiences. Questionnaires and interviews were the most frequently used data collection methods. Most questionnaire-based studies included closed-ended questions with Likert scale response options, whereas some also used open-ended questions or comments to collect qualitative data. Six studies included external data sources such as exams, practical/oral exams, and evaluation by student-learners.

Table 5.

Overview of Studies Reporting Learning Outputs for Student-Teachers Using Various Data Sources

| Data Source | Research Instrument | Number of Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reports 91% (41/45) | Interviews | 18 | [24–27,29,30,32,33,45,47–49,51,55,57,59–61] |

| Reflection essay | 2 | [36,43] | |

| Questionnaire (open-ended questions) | 17 | [22,31,34,37,38,40,44,46,49,52,54,58,60,62–65] | |

| Questionnaire (closed-ended questions) | 31 | [24,26,29–38,40–47,50–54,58,61,63–65] | |

| External data source 13% (6/45) | Practical/oral exam/written exam | 3 | [21,39,61] |

| Evaluation by student learners | 3 | [23,28,44] |

Relation Between Learning Outputs and Data Source of Studies

Among studies using self-reports as data source, 61% (25/41) reported subject-specific learning outputs, 49% (20/41) reported learning outputs related to pedagogical knowledge and skills, 34% (14/41) reported learning outputs related to personal outputs and 44% (18/41) reported learning outputs related to generic skills. Of the studies using external data sources, 4/6 reported subject-specific learning outputs, 4/6 reported increased pedagogical knowledge and skills and 1/6 reported learning outputs related to personal outputs.

Discussion

This review included findings from 45 different studies published 2012–2022 on student-teachers in undergraduate medical education.13 In line with previous review (including 19 articles published before 2012), we found improved learning outputs for student-teachers within several domains, including better knowledge retention, improved skills, improved leadership, improved communications capabilities and increased confidence.13 Most of the evidence available was based on qualitative interview data or survey responses, whereas only six documented learning outputs using external data such as students’ exam results.21,23,28,39,44,61 We found limited, but encouraging, evidence suggesting that peer teaching programs enhance student-teachers’ performances on exams. In most cases, senior students have already passed their exams in the courses in which they later teach junior students and seldom retake the exam after having functioned as student-teachers. Therefore, comparable knowledge or skills tests are available only in designs where students are teaching fellow students and are taking the same exam, as was done in the study by Aguis et al,21 or in a retrospective cohort study design such as Iwata et al.39 Furthermore, final exam scores might not include testing in the topics where student-teachers have gained peer teaching related learning outputs.

We found that student-teachers tend to rate themselves higher than non-teaching students on competence areas in the CanMEDS framework related to academic knowledge. However, research suggests that student-teachers do not perform better on final exams compared to other academically well-performing students who do not participate as student-teachers, thus suggesting that students’ academic knowledge obtained by being student-teachers, can be explained by a recruitment bias rather than a peer teaching effect itself.61 The evidence base for other competence areas in the CanMEDS framework, is somewhat different. The CanMEDS framework recommends physicians to promote a culture that recognizes, supports and responds effectively to colleagues.16 By being a student-teacher, students become role models for their junior peers, thereby promoting the mentioned culture.5 Furthermore, professional skills such as skills in leadership, communication, feedback and collaboration are all part of the CanMEDS framework.16 Amongst the 45 studies we reviewed, 31 articles reported positive learning outputs related to confidence, leadership skills and professional attributes. However, only one article used the CanMEDS framework to assess student-teachers.61 In 14 of the articles included, peer teaching was associated with increased confidence, which is considered important for the professional development of physicians66 and for reduced feelings of imposter syndrome.67 In line with previous reviews, we identified increased learning outputs in similar domains of CanMEDS framework as a result of being a student-teacher.13 A judicious suggestion may therefore be to encourage medical schools to expand teaching and learning opportunities for student-teachers and facilitate the development of their CanMEDS competencies by incorporating peer teaching into their curriculum. This approach would provide a platform for students to enhance their leadership and teaching skills, which are critical components of the CanMEDS framework.6,13

Three articles presented negative outputs of being a student-teacher such as lack of authority due to teachers and student-learners being at the same level,29,30 and feeling uncomfortable teaching their peers due to the lack of necessary skills.34 Despite being reported as a negative experience for the student-teachers, the lack of authority and social congruence associated with peer teaching is elsewhere highlighted as one of the key explanations as to why peer teaching works.68 Negative experiences can likely be avoided with proper training in learning facilitation and group management, clarification of expectations and attention given to building mutual respect in the student-teacher and student-learner relationship.69

Future research could consider developing theory-driven designs that test students’ capabilities in all physician roles. Validated tools for assessing professional skills are readily available, yet infrequently used to test learning outputs of peer teaching for the student-teachers.70 Research should look at the methodological approach of peer teaching programs including recruitment, training interventions, design and content. A deeper understanding of the factors contributing to successful student-teacher practices and outputs has the potential to inform a discussion on how peer teaching activities can be applied more systematically in undergraduate medical education programs, thus securing learning benefits for all parties involved.

Strengths and Limitations

Although we did a thorough search in four databases, our findings are likely inexhaustive due to our exclusion of articles not available in full text, not published in English or not matching the search string. Furthermore, unpublished and/or grey literature was not included. To decrease the risk of bias, eight independent reviewers screened the articles using “blind mode”.71 The results were critically synthesized and interpreted by multiple reviewers to enhance the validity of our findings.

Conclusion

Results from this review indicate that serving as a student-teacher during undergraduate medical school is likely to strengthen subject-specific learning outputs, pedagogical knowledge and skills, personal outputs and generic skills. Peer teaching has the potential to foster professional development in many of the competencies outlined in the CanMEDS framework including communication, collaboration, leadership and health advocacy. Hence, peer teaching programs may be strategically planned and designed to enhance learning outputs for all parties involved, including student-teachers.

Acknowledgments

Christine Tarlebø Mjøs, senior librarian at University of Bergen, Norway, helped with electronic searches in PubMed.

Abbreviations

CanMEDS, Canadian Medical Education Directions for Specialists; MERSQI, The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument; OSCE, objective structured clinical examination.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Cambridge Dictionary [online dictionary]. Cambridge University Press; 2022. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/. Accessed June 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stigmar M. Peer-to-peer teaching in higher education: a critical literature review. Mentor Tutoring. 2016;24(2):124–136. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2016.1178963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees EL, Quinn PJ, Davies B, Fotheringham V. How does peer teaching compare to faculty teaching? A systematic review and meta-analysis (.). Med Teach. 2016;38(8):829–837. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1112888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu TC, Wilson NC, Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:157–172. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S14383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546–552. doi: 10.1080/01421590701583816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ten Cate O, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591–599. doi: 10.1080/01421590701606799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edman J, Elsabet J. Peer teaching and social interaction. Retrieved from Sophia, the St Catherine University repository; 2016. Available from: https://sophiastkateedu/maed/160. Accessed June 30, 2023.

- 8.Whitman NA, Fife JD. Peer teaching: to teach is to learn twice. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4, 1988; 1988.

- 9.Fisher D, Frey N, Fisher D, Frey N, Marsh JP, Gonzalez D. Peer tutoring: “To Teach Is to Learn Twice”. J Adolesc Adult Lit. 2019;62(5):583–586. doi: 10.1002/jaal.922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong JG, Waldrep TD, Smith TG. Formal peer-teaching in medical school improves academic performance: the MUSC supplemental instructor program. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):216–220. doi: 10.1080/10401330701364551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peets AD, Coderre S, Wright B, et al. Involvement in teaching improves learning in medical students: a randomized cross-over study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knobe M, Münker R, Sellei RM, et al. Peer teaching: a randomised controlled trial using student-teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess A, McGregor D, Mellis C. Medical students as peer tutors: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowyer ER, Shaw SC. Informal near-peer teaching in medical education: a scoping review. Educ Health. 2021;34(1):29–33. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_20_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benè KL, Bergus G. When learners become teachers: a review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):783–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CanMEDS framework website. 2022 Royal College of physicians and surgeons of Canada; 2022. Available from: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/about-canmeds-e. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, Levine RB, Kern DE, Cook DA. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s Medical Education Special Issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903–907. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0664-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1002–1009. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the medical education research study quality instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale-education. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1067–1076. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agius A, Stabile I. Undergraduate peer assisted learning tutors’ performance in summative anatomy examinations: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:93–98. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5aa3.e2a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad SE, Farina GA, Fornari A, Pearlman RE, Friedman K, Olvet DM. Student perception of case-based teaching by near-peers and faculty during the internal medicine clerkship: a noninferiority study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211020762. doi: 10.1177/23821205211020762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn JS, French AJ, Thiessen ME, Kendall JL. Training peer instructors for a combined ultrasound/physical exam curriculum. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(3):292–295. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2014.910464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez S, Schultz J-H. Professional and personal competency development in near-peer tutors of gross anatomy: a longitudinal mixed-methods study. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(2):129–137. doi: 10.1002/ase.1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blohm M, Krautter M, Lauter J, et al. Voluntary undergraduate technical skills training course to prepare students for clerkship assignment: tutees’ and tutors’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bugaj TJ, Blohm M, Schmid C, et al. Peer-assisted learning (PAL): skills lab tutors’ experiences and motivation. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1760-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgess A, Dornan T, Clarke AJ, Menezes A, Mellis C. Peer tutoring in a medical school: perceptions of tutors and tutees. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0589-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cansever Z, Avsar Z, Cayir Y, Acemoglu H. Peer teaching experience of the first year medical students from Turkey. J Coll Physicians Surgeons Pak. 2015;25(2):140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho M, Lee YS. Voluntary peer-mentoring program for undergraduate medical students: exploring the experiences of mentors and mentees. Korean J Med Educ. 2021;33(3):175–190. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2021.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chopra N, Zhou DB, Fallar R, Chadha N. Impact of near-peer education in a student-run free ophthalmology clinic on medical student teaching skills. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke AJ, Burgess A, Menezes A, Mellis C. Senior students’ experience as tutors of their junior peers in the hospital setting. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:743. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1729-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cusimano MC, Ting DK, Kwong JL, Van Melle E, MacDonald SE, Cline C. Medical students learn professionalism in near-peer led, discussion-based small groups. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):307–318. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1516555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Menezes S, Premnath D. Near-peer education: a novel teaching program. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:160–167. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5738.3c28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickman N, Barash A, Reis S, Karasik D. Students as anatomy near-peer teachers: a double-edged sword for an ancient skill. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0996-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engels D, Haupt C, Kugelmann D, Dethleffsen K. The peer teachers’ perception of intrinsic motivation and rewards. Adv Physiol Educ. 2021;45(4):758–768. doi: 10.1152/advan.00023.2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottlieb Z, Epstein S, Richards J. Near-peer teaching programme for medical students. Clin Teach. 2017;14(3):164–169. doi: 10.1111/tct.12540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall S, Harrison CH, Stephens J, et al. The benefits of being a near-peer teacher. Clin Teach. 2018;15(5):403–407. doi: 10.1111/tct.12784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandhi A, Primalani N, Raza S, Marlais M. A model for peer-assisted learning in paediatrics. Clin Teach. 2013;10(5):291–295. doi: 10.1111/tct.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwata K, Furmedge DS, Sturrock A, Gill D. Do peer-tutors perform better in examinations? An analysis of medical school final examination results. Med Educ. 2014;48(7):698–704. doi: 10.1111/medu.12475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khaw C, Raw L. The outcomes and acceptability of near-peer teaching among medical students in clinical skills. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:188–194. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5749.7b8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar PR, Stubley T, Hashmi Y, Ahmed U. Clinical Orthopaedic Teaching programme for Students (COTS). Postgrad Med J. 2020;97(1154):749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liew SC, Sow CF, Sidhu J, Nadarajah VD. The near-peer tutoring programme: embracing the ‘doctors-to-teach’ philosophy--a comparison of the effects of participation between the senior and junior near-peer tutors. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):27959. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.27959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin JA, Farrow N, Lindeman BM, Lidor AO. Impact of near-peer teaching rounds on student satisfaction in the basic surgical clerkship. Am J Surg. 2017;213(6):1163–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lufler RS, Lazarus MD, Stefanik JJ. The spectrum of learning and teaching: the impact of a fourth-year anatomy course on medical student knowledge and confidence. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(1):19–29. doi: 10.1002/ase.1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohd Shafiaai MSF, Kadirvelu A, Pamidi N. Peer mentoring experience on becoming a good doctor: student perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):494. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02408-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naeger DM, Conrad M, Nguyen J, Kohi MP, Webb EM. Students teaching students: evaluation of a “near-peer” teaching experience. Acad Radiol. 2013;20(9):1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson AJ, Nelson SV, Linn AM, Raw LE, Kildea HB, Tonkin AL. Tomorrow’s educators. today? Implementing near-peer teaching for medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):156–159. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nshimiyimana A, Cartledge PT. Peer-teaching at the University of Rwanda - a qualitative study based on self-determination theory. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02142-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prunuske A, Houss B, Wirta Kosobuski A. Alignment of roles of near-peer mentors for medical students underrepresented in medicine with medical education competencies: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):417. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1854-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reyes-Hernandez CG, Carmona Pulido JM, De la Garza Chapa RI, et al. Near-peer teaching strategy in a large human anatomy course: perceptions of near-peer instructors. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8(2):189–193. doi: 10.1002/ase.1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahoo S, Venkatesan P, Myint KT, Moe S. Peer-assisted learning activities during undergraduate ophthalmology training: how the medical students of Asia Pacific region perceive. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2015;4(2):76–79. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siddiqi HS, Rehman R, Syed FF, Martins RS, Ibrahim MT, Alam F. Peer-Assisted Learning (PAL): an innovation aimed at engaged learning for undergraduate medical students. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(11):1996–2000. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.29714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silbert BI, Lake FR. Peer-assisted learning in teaching clinical examination to junior medical students. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):392–397. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srivastava TK, Waghmare LS, Mishra VP, Rawekar AT, Quazi N, Jagzape AT. Peer Teaching to Foster Learning in Physiology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(8):Jc01–Jc06. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15018.6323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamachi S, Giles JA, Dornan T, Hill EJR. “You understand that whole big situation they’re in”: interpretative phenomenological analysis of peer-assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1291-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walser J, Horneffer A, Oechsner W, Huber-Lang M, Gerhardt-Szep S, Boeckers A. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of student tutors as near-peer teachers in the gross anatomy course. Ann Anat. 2017;210:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang MM, Golden BP, Cameron KA, et al. Learning through teaching: peer teaching and mentoring experiences among third-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2021;2021:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young I, Montgomery K, Kearns P, Hayward S, Mellanby E. The benefits of a peer-assisted mock OSCE. Clin Teach. 2014;11(3):214–218. doi: 10.1111/tct.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nomura O, Onishi H, Kato H. Medical students can teach communication skills - a mixed methods study of cross-year peer tutoring. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0939-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuo SW, Cichowitz C, Shochet R, Venkatesan A. Peer-led, postanatomy reflection exercise in dissection teams: curriculum and training materials. Med Ed PORTAL. 2017;13:10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Avonts M, Michels NR, Bombeke K, et al. Does peer teaching improve academic results and competencies during medical school? A mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):431. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03507-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aydin MO, Kafa IM, Ozkaya G, Alper Z, Haque S. Peer-assisted skills learning in structured undergraduate medical curriculum: an experiential perspective of tutors and tutees. Niger J Clin Pract. 2022;25(5):589–596. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_1410_21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diebolt JH, Cullom ME, Hornick MM, Francis CL, Villwock JA, Berbel G. Implementation of a Near-Peer Surgical Anatomy Teaching Program into the Surgery Clerkship. J Surg Educ. 2022;80(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orsini E, Quaranta M, Mariani GA, et al. Near-peer teaching in human anatomy from a tutors’ perspective: an eighteen-year-old experience at the University of Bologna. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):398. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah S. Evaluation of online near-peer teaching for penultimate-year objective structured clinical examinations in the COVID-19 era: longitudinal study. JMIR Med Educ. 2022;8(2):e37872. doi: 10.2196/37872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerr J. Confidence and humility: our challenge to develop both during residency. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(4):704–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan M. Imposter syndrome-a particular problem for medical students. BMJ. 2021;375:n3048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Loda T, Erschens R, Loenneker H, et al. Cognitive and social congruence in peer-assisted learning – a scoping review. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson C. The construct of “Respect” in teacher-student relationships: exploring dimensions of ethics of care and sustainable. J Leadersh Educ. 2018;17:42–60. doi: 10.12806/V17/I3/R3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bandiera G, Sherbino J, Frank JR. The CanMEDS Assessment Tools Handbook. An Introductory Guide to Assessment Methods for the CanMEDS Competencies. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2006:0-9739158-6–2. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Day SJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: blinding in clinical trials and other studies. BMJ. 2000;321(7259):504. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]