Abstract

Electrooxidation has emerged as an increasingly viable platform in molecular syntheses that can avoid stoichiometric chemical redox agents. Despite major progress in electrochemical C−H activations, these arene functionalizations generally require directing groups to enable the C−H activation. The installation and removal of these directing groups call for additional synthesis steps, which jeopardizes the inherent efficacy of the electrochemical C−H activation approach, leading to undesired waste with reduced step and atom economy. In sharp contrast, herein we present palladium-electrochemical C−H olefinations of simple arenes devoid of exogenous directing groups. The robust electrocatalysis protocol proved amenable to a wide range of both electron-rich and electron-deficient arenes under exceedingly mild reaction conditions, avoiding chemical oxidants. This study points to an interesting approach of two electrochemical transformations for the success of outstanding levels of position-selectivities in direct olefinations of electron-rich anisoles. A physical organic parameter-based machine learning model was developed to predict position-selectivity in electrochemical C−H olefinations. Furthermore, late-stage functionalizations set the stage for the direct C−H olefinations of structurally complex pharmaceutically relevant compounds, thereby avoiding protection and directing group manipulations.

Subject terms: Electrocatalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Electrochemistry has emerged as an increasingly viable tool in molecular synthesis. Here the authors realize electrocatalyzed C−H activations, with the aid of data science and artificial intelligence, towards selective alkenylations for late-stage drug diversifications.

Introduction

In recent years, molecular electro-organic synthesis has surfaced as a uniquely effective toolbars for sustainable organic syntheses1–4. Despite indisputable progress5–11 by the merger of electrosynthesis and transition metal catalysis, electrochemical C–H activation12–15 has been largely restricted to the use of directing groups (DG)16 for the C–H functionalization. These DGs require additional steps for their installation and removal, contrasting the inherent efficacy of the C–H activation17–21 strategy (Fig. 1a). While the full control of position-selectivity constitutes a major challenge for synthetically useful C–H transformations22–24, recent advances25 in catalyst-controlled C–H activation26–47 have strongly relied on super-stoichiometric amounts of toxic and/or cost-intensive sacrificial chemical oxidants (Fig. 1b).

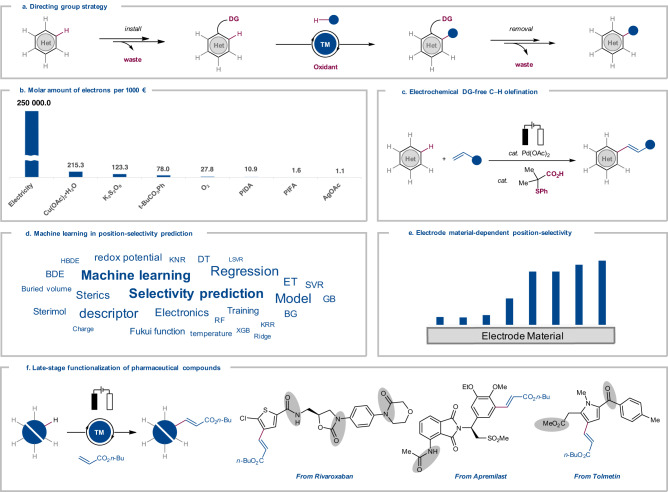

Fig. 1. Directing Group (DG)-free Electrochemical C–H Activation.

a Directing group (DG)-assisted oxidative C–H activation by installation and removal of DG. b Molar amount of electrons per 1000 euro from electricity and chemical oxidants. PIFA = (bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodine)benzene. PIDA = (Diacetoxyiodo)benzene. c Electrochemical DG-free C–H olefination. d Machine learning in position-selectivity prediction. e Effects of the electrode material onto site-selectivity. f Late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutical molecules. (Potential DG was highlighted in gray).

In this work, we disclose exogenous DG-free palladium-electrochemical C–H olefinations at low temperature without strong stoichiometric oxidants (Fig. 1c)48. Additionally, our machine learning (ML) modeling49–54 provide accurate and efficient prediction of the position-selectivity (Fig. 1d). Our approach is characterized by outstanding position-selectivity in olefinations of the electron-rich substrates by the judicious choice of electrode material (Fig. 1e). Notably, this strategy exhibits high functional group tolerance and unique position-selectivity undisturbed by potential DG, providing straightforward route for the late-stage C–H functionalization of structurally complex molecules of relevance to drug discovery and chemical biology (Fig. 1f).

Results

We initiated our studies towards the non-directed electrochemical C–H activation by evaluating several N-type ligands27,28, (Supplementary Table 5). We were indeed delighted to observe electrocatalytic activity for o-xylene (1h) with 2-hydroxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine (L1) as the ligand, notably in the absence of chemical oxidants. Variation of the pyridone resulted in an increased efficacy with ligand L3. Protected amino acids L5–L6 and 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one (L7) afforded inferior results in the electrocatalysis. Next, a representative set of sulfur-based ligands L8–L12 was tested40–42,46, and we found an almost quantitative conversion to the olefination product 11 with S,O-ligand L12 by the electrocatalysis.

While altering the stoichiometry did not have considerable influence on the efficacy (Supplementary Table 7, entry 2), the product 11 was not observed when n-Bu4NOAc was used as the supporting electrolyte (entry 3). Likewise, a solvent mixture of TFE and AcOH failed to provide the olefinated product 11 (entry 4). The electrocatalysis occurred efficiently in the absence of 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), while catalytic amounts of BQ, working as redox mediator in our catalytic system rather than chemical oxidant, is suggested to prevent the aggregation of the palladium catalyst, thereby improving the catalyst’s performance (entry 5). Control experiments revealed the necessity of the palladium catalyst, the ligand and the electricity for the DG-free electrochemical C–H activation (entry 6–8). Importantly, scaling up allows to reduce the arene equivalent without any decrease of its efficacy (Supplementary Table 10, entry 1). Thus, the electrolysis for 48 h with 1.5 equiv. of arene and 1 equiv. of alkene along with catalytic amounts of Pd(OAc)2, ligand L12, and BQ, followed by addition of sodium acetate, in acetic acid and hexafluoroisopropanol delivers the olefinated product.

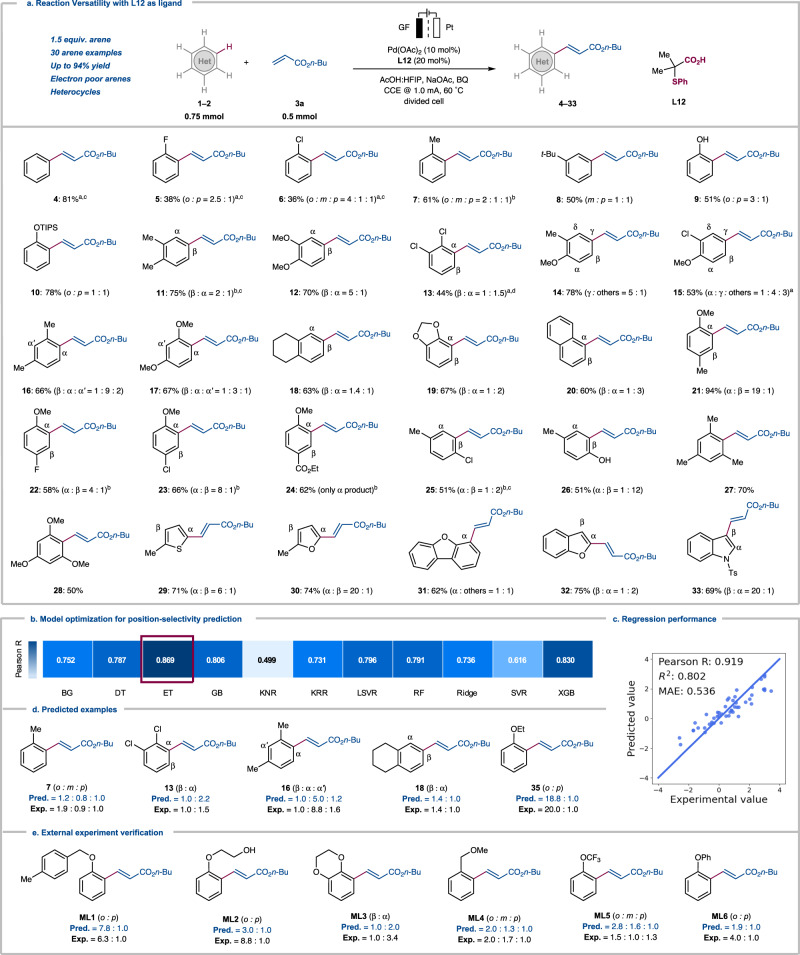

With the optimized electrolysis conditions in hand, we tested the robustness of the DG-free electrochemical olefination (Fig. 2a). We were pleased to find that both electron-rich and more challenging electron-poor arenes 1–2 delivered the mono-olefinated products in good to excellent yields by the palladium-electrocatalysis. Electron-deficient fluoro- and chloro-benzene 1b–1c provided the mono-olefinated products 5–6 in moderate yields. Subsequently, a wide range of monosubstituted arenes 1d–1g was selectively functionalized, including hydroxyl group OH-free, unprotected phenol 1f with high yields (9). Disubstituted arenes were also examined under the optimized conditions, and for symmetrical disubstituted arenes, the position-selectivity was largely governed by repulsive steric interactions. Dimethoxybenzene (1i) yielded mainly the β-olefinated product 12, while dichlorobenzene (1j) gave mainly α-olefinated product 13 instead. 1,2-Disubstituted arenes 1k–1l were predominantly olefinated by the electrooxidation at the γ-position which is para to methoxy (14–15). 1,3-Disubstituted arenes 1m and 1n were predominantly olefinated at the α-position (16–17), while benzodioxole (1p) and naphthalene (1q) afforded predominantly the α-isomers (19–20). When para-substituted anisoles 1r–1u were tested, the ortho-substituted anisole olefinated products 21–24 were obtained as the main products. A steric effect was predominant for para-chlorotoluene (1v) and p-cresol (1w), since we primarily observed β-isomers 25–26. Furthermore, symmetrical trisubstituted arenes 1x and 1y were efficiently converted, delivering the mono-olefinated products 27 and 28, respectively. It is noteworthy that the robust electrocatalysis was also viable for heteroarenes. Thus, thiophene (1z), furan (2a), benzofuran (2b and 2c) and indole (2d) were efficiently olefinated by the palladium-electrocatalysis to yield the olefinated products 29–33 in the absence of chemical oxidants.

Fig. 2. Substrate Scope and Machine Learning.

See supplementary information for reaction details. a DG-Free Palladium-Electrochemical C–H Activation. General procedure C: divided cell, anodic chamber: 1–2 (0.75 mmol), 3a (0.50 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol %), L12 (20 mol %), NaOAc (0.20 M), BQ (10 mol %), HFIP:AcOH (1:2); cathodic chamber: NaOAc (0.20 M), BQ (10 mol %), HFIP:AcOH (1:2), constant current at 1.0 mA, 60 °C, 48 h, graphite felt (GF) anode, Pt-plate cathode. a General procedure A, 1–2 (2.0 mmol or 4.0 mmol), 3a (0.20 mmol). b 1–2 (1.0–1.5 mmol). c 80 °C. d 100 °C. b Machine learning model selection for position-selectivity prediction (Pearson R). The shadings represent the quality of the regression, the abbreviations embody the machine learning models. c Regression performances after descriptor selection. d Machine learning predictions for out-of-sample (OOS) examples. e Machine learning predictions for external experiment examples.

Next, in order to accurately predict the site-selectivity, we developed a ML model based on the collected position-selectivity data of all the arenes. A series of physical organic features including buried volume, Sterimol, Fukui function, charge, bond dissociation energies, etc. were applied to encode the involved molecules and enable the ML modeling (Supplementary Table 13). In addition to these site-specific descriptors, the computed redox potential of arenes were also included, considering the importance of electro-oxidation. These molecular descriptors, together with the reaction temperature, created a 28-dimensional encoding for each pair of regioisomeric competing sites, and an array of ML algorithms were evaluated for the regression performance in leave-one-out data splitting (Fig. 2b). The Extra-Trees (ET) model was found to provide the best performance in the position-selectivity prediction, and subsequent feature selection further improves the model’s prediction ability while decreasing the complexity of the descriptor space. The resulting ML model revealed a high level of accuracy (Pearson R = 0.919 and mean absolute error (MAE) = 0.536) (Fig. 2c). Feature importance elucidated the determining factors responsible for the regioselectivity prediction, in which the Fukui function of the reacting site emerged as the most crucial parameter (Supplementary Fig. 21). To further validate our model, we tested out-of-sample (OOS) predictions by taking selected arenes out of the training set. The model was revalidated without the access to the regioselectivity data of the selected arenes, and Fig. 2d highlighted a few examples of these excellent OOS predictions. Encouraged by the results, we further tested these predictions experimentally with 6 new arenes. Overall, our models align well with the experimental observations (Fig. 2e), which showed the predictive potential of the model in a rational way to reduce the experimental optimization.

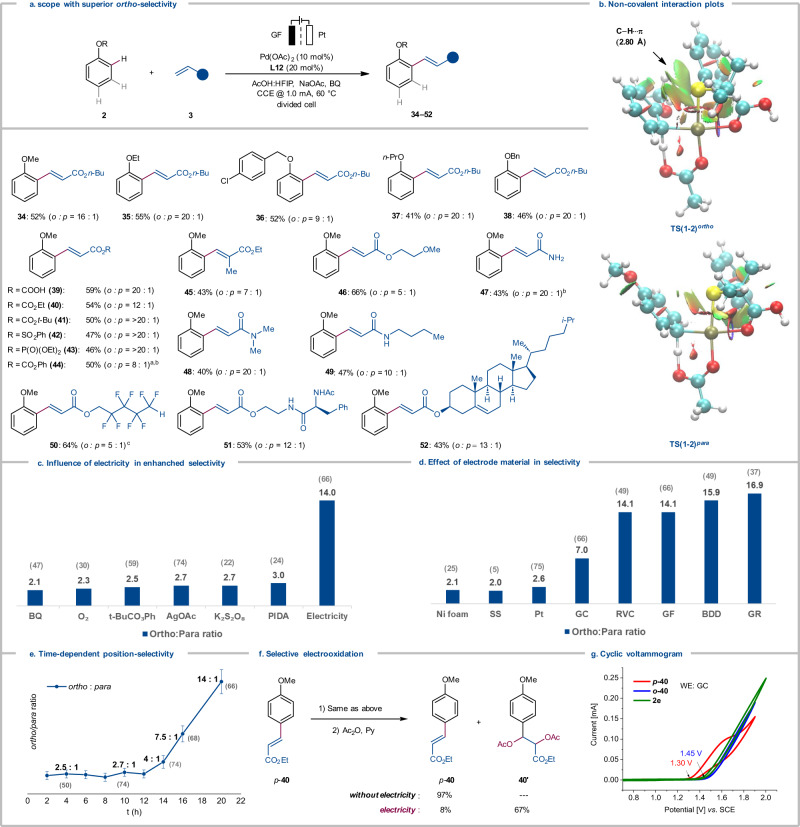

Thereafter, we examined the versatility of the electrocatalysis with regards to anisole derivatives 2 and alkenes 3 (Fig. 3a). Thus, anisole and ethoxy benzene provided high position-selectivity for the ortho-functionalized products 34 and 35. It is noteworthy that these selectivities are complementary to ones previously observed with pyridine-based ligands, which gave para-olefinated products as the major isomer27,31. Similarly, (benzyloxy)benzene derivatives and propoxybenzene mirrored the selectivity, delivering mono-alkenylated products 36–38. Likewise, a range of alkenes 3 was compatible with the versatile electrochemical conditions, providing an array of olefinated products 39–52. Acrylates 3b–3d including acrylic acid gave outstanding levels of ortho-selectivities to afford the products 39–41. Similarly, α,β-unsaturated olefin 3e–3g mirrored this position-selectivity, providing ortho-olefinated products 42–44 as the major isomers. α-substituted acrylates (3h) were also identified as amenable substrates (45). Primary, secondary and tertiary acrylamide (3j–3l) also well adapted to the superior position-selectivity. Furthermore, the mild nature of the palladium-electrocatalysis manifold allowed for the use of fluorinated alkene 3m, NH-free amino acid derivative 3n and bio-relevant cholesterol 3o delivering the predominantly ortho-olefinated products 50–52. Here, it is noteworthy that 5.0 equivalents of arene are needed to provide good ortho-selectivity.

Fig. 3. Mechanistic Study for Superior Ortho-selectivity.

See supplementary information for reaction details. a Scope for anisole and olefin. General procedure A: divided cell, anodic chamber: 2 (1.0 mmol), 3 (0.20 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), L12 (20 mol%), NaOAc (0.20 M), BQ (20 mol%), HFIP:AcOH (1:2); cathodic chamber: NaOAc (0.20 M), BQ (20 mol%), HFIP:AcOH (1:2), constant current at 1.0 mA, 60 °C, 20 h, graphite felt (GF) anode, Pt-plate cathode. a General procedure C, 2 (1.0 mmol), 3 (0.5 mmol). b Pt as anode. c 80 °C. b Non-covalent interaction plots for the TS(1-2)ortho and TS(1-2)para. c Chemical oxidants vs Electricity. d Variation of anode materials. RVC Reticulated vitreous carbon, GF Graphite felt, BDD Boron doped diamond. GR Graphite rod. e Ortho/para-selectivity profile. Combined yields of ortho/para-34 were given in the parenthesis. The error bars indicate the possible selectivity fluctuations generated from crude NMR analysis. f Selective electrooxidation of p-40. g Cyclic voltammogram for 40, glass carbon was used as working electrode.

To delineate the C–H activation elementary step, the potential energy profile was computed at the PBE0-D4/def2-TZVP + SMD(AcOH)//PBE0-D3BJ/def2-SVP level of theory. The formation of the ortho-product was found to be kinetically and thermodynamically preferred, with C–H activation barriers of 9.7 kcal mol−1 (TS(1-2)ortho) and 10.7 kcal mol−1 (TS(1-2)para) respectively (Supplementary Fig. 34a). Non-covalent interactions in the TS(1-2)ortho further revealed the presence of a weak stabilization interaction between the anisole’s methoxy group and the S,O-ligand phenyl motif, which contributes to the preferential formation of the ortho-product (Fig. 3b).

To further understand the origin of the high position-selectivity with anisoles, we conducted detailed studies (Figs. 3c–g). Here, we observed significant improvement in position-selectivities under the electrochemical conditions compared to reactions with commonly employed chemical oxidants (Fig. 3c). Exploring different electrode materials revealed a remarkable dependence of the position-selectivity on the choice of the material, thereby altering the ortho/para-selectivity from 2:1 to 17:1 (Fig. 3d). For such sharp change in selectivities, time-resolved analysis revealed critical insights (Fig. 3e). The ratio of the ortho/para selectivity remained constant within the first 12 hours, followed by a considerable change thereafter in favor of the ortho-functionalized product. This observation was rationalized by a subsequent selective electrochemical oxidation of the alkene only in the para-olefinated product. It is noteworthy that the second oxidation occurred selectively after the alkene 3a was fully consumed (Supplementary Table 21). The independently prepared para-olefinated product 40 was subjected to the standard electrochemical conditions, followed by acetoxylation, resulting in the formation of diacetate 40’ (Fig. 3f). Control experiments showed the essential role of the electricity for the two-fold electrooxidation. CV studies confirmed that the para-olefinated product is more labile to be oxidized than the ortho-olefinated product, and were well aligned with our experimental observation for electrode material dependence on position-selectivity (Fig. 3g & Supplementary Fig. 12). In contrast, a representative set of commonly employed chemical oxidants were tested such as BQ, AgOAc, K2S2O8, PIDA or TBHP for selective oxidation of the products (Supplementary Table 19). The results were unsatisfactory, highlighting crucial and unique role of electricity in the selective oxidation process.

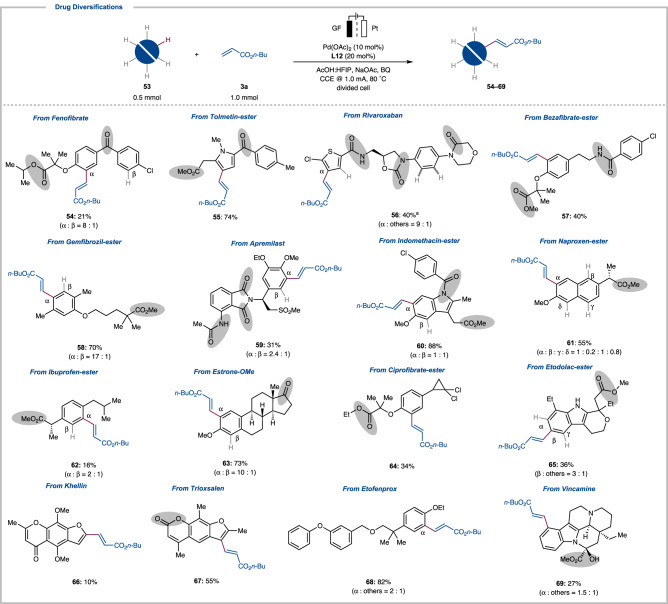

Finally, the unique power of the DG-free electrocatalysis was exploited for the late-stage functionalization (LSF) of biorelevant drug molecules (Fig. 4)19–21,47. C–H olefination of fenofibrate proceeded efficiently to afford the olefinated product 54. Tolmetin was selectively functionalized at the pyrrole ring to yield the mono-olefinated product 55 in 74% yield. Rivaroxaban was olefinated by the palladium-electrocatalysis to afford 56. Bezafibrate was selectively converted to product 57. At the same time, gemfibrozil was effectively converted into the corresponding alkenylated products 58. Moreover, apremilast was transformed into two separable products 59. Indomethacin was selectively olefinated to afford 60 in 88% yield at both ortho-positions of the anisole. Under the chemical oxidant-free electrocatalysis, naproxen afforded olefins 61. Ibuprofen was functionalized to provide 62 and ester derivative of estrone were efficiently alkenylated at the ortho-position to afford 63. Likewise, derivatives of ciprofibrate and etodolac provided the olefinated products 64 and 65. Natural products like khellin and trioxsalen gave single products 66 and 67 under our reaction condition. Etofenprox similarly delivered the olefinated product 68 in 82% yield. Interestingly, vincamine was also tolerated and delivered product 69. It is noteworthy to mention that our robust electrocatalysis enabled the LSF of complex drug molecules by overruling the presence of myriad of strongly coordinating directing groups ranging from ketone to amide and esters.

Fig. 4. Late-Stage Functionalization of Drug Molecules.

See supporting information for details. Brief reaction condition: 53 (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 3a (1.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), divided cell, 80 °C, 48 h. a 53 (0.36 mmol, 1.8 equiv.), 3a (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.). Potential coordinating directing groups are highlighted in gray.

We have devised a robust and versatile electrochemical direct alkenylation without chemical oxidants and directing groups. The electrochemical olefination was realized by the synergistic cooperation of electricity, electrode material and a palladium catalyst. A broad variety of alkenes and arenes proved to be compatible with the electrooxidative catalysis. A two-fold electrochemical oxidation was uncovered, leading to outstanding levels of selectivity for anisole functionalization. Detailed studies showed the key effect of electricity and the electrode materials in the selectivity control, and machine learning modeling was developed to enable the data-driven position-selectivity prediction. The transformative nature of our strategy was highlighted by late-stage diversifications of bioactive drug molecules without the installation and removal of any directing groups. Additionally, the electrocatalysis yields molecular hydrogen as the only by product, representing a synthetically useful anodic oxidation to future green hydrogen technology by the hydrogen evaluation reaction (HER).

Methods

General Procedure: Non-directed Electrochemical Olefinations

The electrocatalysis was carried out in a divided cell, equipped with a GF anode and a Pt cathode (10 mm × 15 mm × 0.25 mm). Arenes (0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), acrylates (0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2 (11.3 mg, 10 mol%), ligand (20 mol%), 1,4-benzoquinone (5.4 mg, 10 mol %) and NaOAc (50 mg, 0.20 M) were placed in the anodic chamber and dissolved in AcOH (2.0 mL) and HFIP (1.0 mL); 1,4-benzoquinone (5.4 mg, 10 mol%) and NaOAc (50 mg, 0.20 M) were placed in the cathodic chamber and dissolved in AcOH (2.0 mL) and HFIP (1.0 mL). Galvanostatic electrocatalysis was performed at 60 °C with a current of 1.0 mA and a stirring rate of 500 rpm maintained for 48 h. At ambient temperature, the resulting mixture was diluted with EtOAc (8.0 mL). The GF anode was washed with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL) in an ultrasonic bath. The combined organic phases were loaded on a column and washed with EtOAc (50 mL). The solvents were removed in vacuo. Then, NMR was determined by adding CH2Br2 (35.0 µL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) as the standard. The crude mixture was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to yield the products.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Generous support by the ERC Advanced Grant no.101021358, the DFG (Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz award, SPP 1807 and SPP 2363), the European Union H2020 research and innovation program under the Marie S. Curie Grant Agreement No 860762 (CHAIR), National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1504301, X.H.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22122109 and 22271253, X.H.), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LDQ23B020002 (X.H.), the Starry Night Science Fund of Zhejiang University Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study (SN-ZJU-SIAS-006, X.H.), Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (BNLMS202102, X.H.), the Center of Chemistry for Frontier Technologies and Key Laboratory of Precise Synthesis of Functional Molecules of Zhejiang Province (PSFM 2021-01, X.H.), the State Key Laboratory of Clean Energy Utilization (ZJUCEU2020007, X.H.), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (226-2022-00140, 226-2022-00224 and 226-2023-00115, X.H.) and CAS Youth Interdisciplinary Team (JCTD-2021-11, X.H.), the CSC (scholarship to Z.L., X.Y.H., and B.Y.), the DAAD (fellowship to U.D.) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (scholarship 110-2917-I-003-002 to Y.-C.L.) is gratefully acknowledged. Calculations related to M.L. were performed on the high-performance computing system at the Department of Chemistry, Zhejiang University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.; Methodology, U.D., Z.L., L.A., M.J.; Experiment, Z.L., XY.H., M.S., Y.-C.L., and U.D.; DFT, B.Y.; Machine Learning, X.H., S.L., L.X., C.C.; Writing, contributed by all authors; Funding Acquisition, L.A.; Resources, L.A.; Supervision, L.A.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Cartesian Coordinates used for DFT calculation were included in Supplementary Data 1. All the involved codes and data in this study are freely available at 10.5281/zenodo.8003927. Source data are provided with this paper and deposited in Zenodo under accession code 10.5281/zenodo.8009809. All other requests for materials and information should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhipeng Lin, Uttam Dhawa, Xiaoyan Hou.

Contributor Information

Xin Hong, Email: hxchem@zju.edu.cn.

Lutz Ackermann, Email: Lutz.Ackermann@chemie.uni-goettingen.de.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-39747-0.

References

- 1.Zhu C, Ang NWJ, Meyer TH, Qiu Y, Ackermann L. Organic electrochemistry: molecular syntheses with potential. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021;7:415–431. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu N, Sauer GS, Saha A, Loo A, Lin S. Metal-catalyzed electrochemical diazidation of alkenes. Science. 2017;357:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiong P, Xu H-C. Chemistry with electrochemically generated N-centered radicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52:3339–3350. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan M, Kawamata Y, Baran PS. Synthetic organic electrochemical methods since 2000: on the verge of a renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:13230–13319. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malapit CA, et al. Advances on the merger of electrochemistry and transition metal catalysis for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:3180–3218. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma C, et al. Transition metal-catalyzed organic reactions in undivided electrochemical cells. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:12866–12873. doi: 10.1039/D1SC04011A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novaes LFT, et al. Electrocatalysis as an enabling technology for organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:7941–8002. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00223F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer TH, Choi I, Tian C, Ackermann L. Powering the future: how can electrochemistry make a difference in organic synthesis? Chem. 2020;6:2484–2496. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.08.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiao K-J, Xing Y-K, Yang Q-L, Qiu H, Mei T-S. Site-selective C–H functionalization via synergistic use of electrochemistry and transition metal catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:300–310. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackermann L. Metalla-electrocatalyzed C–H activation by earth-abundant 3d metals and beyond. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:84–104. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma C, Fang P, Mei T-S. Recent advances in C–H functionalization using electrochemical transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7179–7189. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhawa U, et al. Enantioselective pallada-electrocatalyzed C−H activation by transient directing groups: expedient access to helicenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:13451–13457. doi: 10.1002/anie.202003826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Q-L, et al. Palladium-catalyzed C(sp3)–H oxygenation via electrochemical oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3293–3298. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakiuchi F, et al. Palladium-catalyzed aromatic C−H halogenation with hydrogen halides by means of electrochemical oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11310–11311. doi: 10.1021/ja9049228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amatore C, Cammoun C, Jutand A. Electrochemical recycling of benzoquinone in the Pd/Benzoquinone-catalyzed heck-type reactions from arenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:292–296. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200600389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambiagio C, et al. A comprehensive overview of directing groups applied in metal-catalysed C–H functionalisation chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:6603–6743. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00201K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogge T, et al. C–H activation. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2021;1:43. doi: 10.1038/s43586-021-00041-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He J, Wasa M, Chan KSL, Shao Q, Yu J-Q. Palladium-catalyzed transformations of alkyl C–H bonds. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:8754–8786. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Ritter T. A perspective on late-stage aromatic C–H bond functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:2399–2414. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillemard L, Kaplaneris N, Ackermann L, Johansson MJ. Late-stage C–H functionalization offers new opportunities in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021;5:522–545. doi: 10.1038/s41570-021-00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:546–576. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00628G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng G, et al. Achieving site-selectivity for C–H activation processes based on distance and geometry: a carpenter’s approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:10571. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JC, Coelho PS, Arnold FH. Enzymatic functionalization of carbon–hydrogen bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2003–2021. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00067A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craven EJ, et al. Programmable late-stage C−H bond functionalization enabled by integration of enzymes with chemocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2021;4:385–394. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00603-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedi P, van Gemmeren M. Arene-limited nondirected C−H activation of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:13016–13027. doi: 10.1002/anie.201804727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia C, Kitamura T, Fujiwara Y. Catalytic functionalization of arenes and alkanes via C−H bond activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:633–639. doi: 10.1021/ar000209h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P, et al. Ligand-accelerated non-directed C–H functionalization of arenes. Nature. 2017;551:489–493. doi: 10.1038/nature24632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y-H, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. Pd(II)-catalyzed olefination of electron-deficient arenes using 2,6-dialkylpyridine ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5072–5074. doi: 10.1021/ja900327e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook AK, Sanford MS. Mechanism of the palladium-catalyzed arene C–H acetoxylation: a comparison of catalysts and ligand effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3109–3118. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook AK, Emmert MH, Sanford MS. Steric control of site selectivity in the Pd-catalyzed C–H acetoxylation of simple arenes. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5428–5431. doi: 10.1021/ol4024248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubota A, Emmert MH, Sanford MS. Pyridine ligands as promoters in PdII/0-catalyzed C–H olefination reactions. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1760–1763. doi: 10.1021/ol300281p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emmert MH, Cook AK, Xie YJ, Sanford MS. Remarkably high reactivity of Pd(OAc)2/pyridine catalysts: nondirected C–H oxygenation of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9409–9412. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Aerobic oxidative coupling of o-Xylene: discovery of 2-fluoropyridine as a ligand to support selective Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:3223–3229. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wedi P, Farizyan M, Bergander K, Mück-Lichtenfeld C, van Gemmeren M. Mechanism of the arene-limited nondirected C−H activation of arenes with palladium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:15641–15649. doi: 10.1002/anie.202105092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mondal A, van Gemmeren M. Catalyst-controlled regiodivergent C−H alkynylation of thiophenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:742–746. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farizyan M, Mondal A, Mal S, Deufel F, van Gemmeren M. Palladium-catalyzed nondirected late-stage C–H deuteration of arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;40:16370–16376. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c08233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Farizyan M, Ghiringhelli F, van Gemmeren M. Sterically controlled C−H olefination of heteroarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:12213–12220. doi: 10.1002/anie.202004521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mondal A, Chen H, Flämig L, Wedi P, van Gemmeren M. Sterically controlled late-stage C–H alkynylation of arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:18662–18667. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H, Wedi P, Meyer T, Tavakoli G, van Gemmeren M. Dual ligand-enabled nondirected C−H olefination of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:2497–2501. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sukowski V, Jia W-L, van Diest R, van Borselen M, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ. S,O-igand-promoted Pd-catalyzed C−H olefination of anisole derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021;2021:4132–4135. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202100737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naksomboon K, Poater J, Bickelhaupt FM, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ. para-selective C–H olefination of aniline derivatives via Pd/S,O-ligand catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:6719–6725. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jia W-L, et al. Selective C–H olefination of indolines (C5) and tetrahydroquinolines (C6) by Pd/S,O-ligand catalysis. Org. Lett. 2019;21:9339–9342. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naksomboon K, Valderas C, Gómez-Martínez M, Álvarez-Casao Y, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ. S,O-ligand-promoted palladium-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions of nondirected arenes. ACS Catal. 2017;7:6342–6346. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramadoss B, Jin Y, Asako S, Ilies L. Remote steric control for undirected meta-selective C–H activation of arenes. Science. 2022;375:658–663. doi: 10.1126/science.abm7599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuninobu Y, Ida H, Nishi M, Kanai M. A meta-selective C–H borylation directed by a secondary interaction between ligand and substrate. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:712–717. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorsline BJ, Wang L, Ren P, Carrow BP. C–H alkenylation of heteroarenes: mechanism, rate, and selectivity changes enabled by thioether ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9605–9614. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao D, Xu P, Ritter T. Palladium-catalyzed late-stage direct arene cyanation. Chemistry. 2019;5:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Note: After the publication of this manuscript as a preprint: Ackermann, L. et al. Electrocatalyzed Direct Arene Alkenylations without Directing Groups: Selective Late-Stage Drug Diversification. Research Square (2022). [PREPRINT] 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1607467/v1, and during the revision, a study on non-directed palladium-catalysed electrooxidative olefination of arenes was published: Panja, S. et al. Non-directed Pd-catalysed electrooxidative olefination of arenes. Chem. Sci. 13, 9432–9439, (2022).

- 49.Ahneman DT, Estrada JG, Lin S, Dreher SD, Doyle AG. Predicting reaction performance in C–N cross-coupling using machine learning. Science. 2018;360:186–190. doi: 10.1126/science.aar5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beker W, Gajewska EP, Badowski T, Grzybowski BA. Prediction of major regio-, site-, and diastereoisomers in Diels–Alder reactions by using machine-learning: the importance of physically meaningful descriptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:4515–4519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201806920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reid JP, Proctor RSJ, Sigman MS, Phipps RJ. Predictive multivariate linear regression analysis guides successful catalytic enantioselective minisci reactions of diazines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:19178–19185. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zahrt AF, et al. Prediction of higher-selectivity catalysts by computer-driven workflow and machine learning. Science. 2019;363:eaau5631. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X, Zhang S-Q, Xu L-C, Hong X. Predicting regioselectivity in radical C−H functionalization of heterocycles through machine learning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:13253–13259. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guan Y, et al. Regio-selectivity prediction with a machine-learned reaction representation and on-the-fly quantum mechanical descriptors. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:2198–2208. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04823B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Cartesian Coordinates used for DFT calculation were included in Supplementary Data 1. All the involved codes and data in this study are freely available at 10.5281/zenodo.8003927. Source data are provided with this paper and deposited in Zenodo under accession code 10.5281/zenodo.8009809. All other requests for materials and information should be addressed to the corresponding authors.